Abstract

Background:

Acute kidney injury (AKI) that develops during pregnancy results from pregnancy-induced hypertension, hemorrhage, and sepsis, associated with morbidity and mortality in the fetus and mother. This meta-analysis was conducted to evaluate the incidence of pregnancy-related AKI (PR-AKI) and adverse clinical outcomes.

Methods:

PubMed and Scopus were systematically searched for studies published between 1980 and 2021. We included cross-sectional, retrospective, and prospective cohort studies that reported the incidence of PR-AKI as well as adverse fetal and maternal clinical outcomes. A random-effects model meta-analysis was performed to generate summary estimates.

Results:

The meta-analysis included 31 studies (57,529,841 participants). The pooled incidence of PR-AKI was 2.0% (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.0–3.7). Only 49.3% of patients received antenatal care. The most common cause of PR-AKI was preeclampsia (36.6%, 95% CI 29.1–44.7). The proportion of patients requiring hemodialysis was 37.2% (95% CI 26.0–49.9). More than 70% of patients had complete recovery of renal function, while 8.5% (95% CI 4.7–14.8) remained dependent on dialysis. The pooled mortality rate of PR-AKI was 12.7% (95% CI 9.0–17.7). In addition, fetal outcomes were favorable, with an alive birth rate of 70.0% (95% CI 61.2–77.4). However, the rate of abortion and/or stillbirth was approximately 25.4% (95% CI 18.1–34.4), and the rate of intrauterine death was 18.6% (95% CI 12.8–26.2).

Conclusions:

Although the incidence of PR-AKI is not high, this condition has a high impact on morbidity and mortality in both fetal and maternal outcomes. Early prevention and treatment from health care professionals are needed in PR-AKI, especially in the form of antenatal care and preeclampsia medication.

1. Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) that develops during pregnancy results from such as pregnancy-induced hypertension, hemorrhage, and sepsis, associated with morbidity and mortality in the fetus and mother.[1,2] Previous studies have reported a dramatic reduction in the incidence of AKI during pregnancy in developed countries, from 1/3000 to 1/20,000, which was attributed to improved antenatal care.[3] The diagnosis and treatment of AKI during pregnancy (pregnancy-related AKI, PR-AKI) is challenging. The risk profiles and geographic distribution of pregnancy-related AKI may be different in various parts of the world[4–6] and between different regions within the same country. The reported incidence of PR-AKI in developing countries, such as India and Pakistan, is 0.02% to 71.5%.[7–10] Data from South Asia suggest that PR-AKI accounts for 10% of total AKI cases.[5] However, in high-income countries, PR-AKI is rare.[11]

In developing countries, sepsis and hemorrhage account for >50% of cases of PR-AKI,[12,13] in contrast to developed countries, where chronic hypertension, renal disease, and preeclampsia are important causes of this condition.[14,15] The maternal and fetal outcomes that are of concern include permanent damage to the kidney, maternal survival, rate of renal recovery, dialysis dependence, rate of live births, stillbirths, and intrauterine death. This systematic review and meta-analysis of observation studies aimed to evaluate the overall incidence of PR-AKI and its prognostic value for fetal and maternal adverse clinical outcomes.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy and study selection

We performed a literature search in MEDLINE and SCOPUS (from 1989 to March 2021) to identify eligible studies using the Medical Subject Heading and text keywords “acute renal failure”, “acute kidney injury”, “acute renal insufficiency”, combined with all spellings of “pregnancy” and “pregnant.” The search was limited to the English language. Reference lists of the obtained articles were also searched for relevant publications. Only officially published papers were considered for inclusion in the present meta-analysis. Studies were required to meet the following inclusion criteria: original article including cross-sectional, retrospective, or prospective cohort studies, and reported pregnancy outcomes and kidney outcomes in women with PR-AKI. Narrative reviews, case reports/series, conference abstracts, and registry databases were excluded. We followed the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis and meta-analyses Of observational studies in epidemiology guidelines to report the meta-analysis (Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MD/G956).[16]

2.2. Data extraction

Data were independently extracted from full-text articles by 2 investigators (T.T. and T.G.) using a standardized approach. Disagreement between the 2 investigators was recorded and adjudicated by a third reviewer (P.S.). Data on country of origin, number of patients, patient age, number of parities, trimester, causes of AKI, and underlying diseases were recorded. We also extracted data on maternal and fetal outcomes, number of patients who required renal replacement therapy, recovery of renal function, and subsequent dependence on dialysis. The other maternal outcomes included death; preeclampsia; hemorrhage during and after delivery; and hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count (HELLP) syndrome. Fetal outcomes, including perinatal death, abortion, stillbirth, and preterm delivery, were also recorded.

2.3. Study quality assessment

The quality of the cohort studies was evaluated by using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, which allocates a maximum of 9 points for quality of the selection, comparability, and outcome of study populations. Study quality scores were defined arbitrarily as poor (0–3), fair (4–6), or good (7–9).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Random-effects model meta-analyses were conducted to generate pooled incidence rates of AKI, caused of AKI, fetal, and maternal outcomes. All pooled estimates are provided with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 index. The I2 index describes the percentage of total variation across studies due to true heterogeneity rather than chance, with a value of >75% indicating medium-to-high heterogeneity. To examine the effect of developed vs under developed countries on the incidence of AKI, we conducted random-effects subgroup. We also performed subgroup analysis on the AKI definitions by using the RIFLE or Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) vs other definitions including biochemical/urine output/dialysis requirement-based definitions/administrative codes for AKI derived from the International Classification of Diseases, 9th or 10th Revision, Clinical Modification methodology. We explored the robustness of interested outcomes by sensitivity analysis and subgroup analysis based on study quality. Publication bias was formally assessed using the Egger test. We performed the meta-analyses using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (version 2.0; Biostat, www.meta-analysis.com).

3. Results

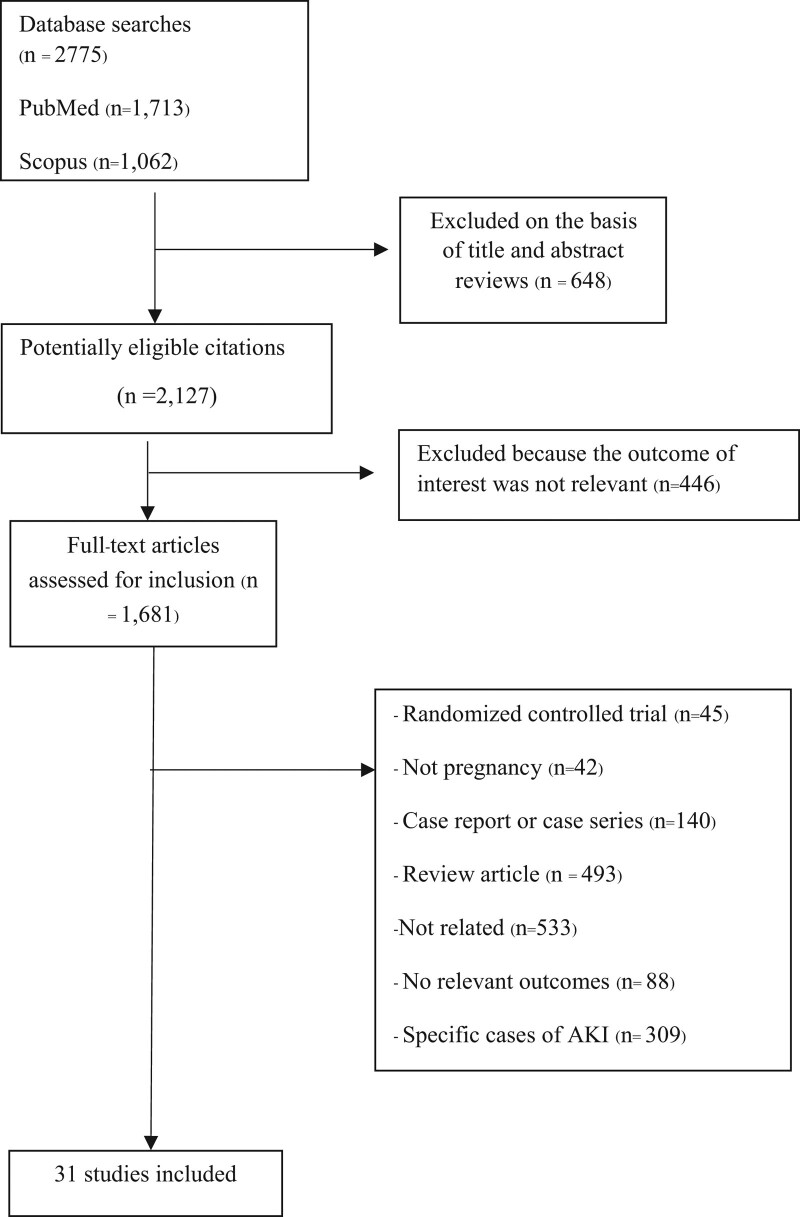

The literature search yielded 2775 articles; 1681 studies were retrieved for detailed evaluation, among which 31 fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies. These studies were performed between 1993 and 2021, with sample sizes ranging from 75 to 42,190,790 participants. The scope of the study covered all regions of the world. Most studies were conducted in India (n = 10), followed by the United States (n = 4); China and Pakistan (n = 3 each); Brazil, Morocco, and Canada (n = 2 each); and Mexico, Turkey, Egypt, Greece, and Malawi (n = 1 each; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of articles considered for inclusion.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies in the meta-analysis.

| Authors | Publication years | Study design | Country | No. of AKI | No. of patients | Mean age | AKI criteria | Study quality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alexopoulos et al[24] | 1993 | Retrospective study | Greece | 18 | 200 | 32.0 | Serum creatinine >1.8 mg/dL | 6.0 |

| 2 | Naqvi et al[38] | 1996 | Cross-sectional | Pakistan | 43 | 238 | 28.30 | Not stated | 6.0 |

| 3 | Selcuk et al[39] | 1998 | Retrospective cohort | Turkey | 74 | 487 | 29.0 | Not stated | 6.0 |

| 4 | Najar et al[3] | 2008 | Prospective cohort | India | 40 | 569 | 28.94 | Urine output <400 mL or creatinine >1.5 mg/dL | 7.0 |

| 5 | Ansari et al[40] | 2008 | Retrospective study | Pakistan | 42 | 116 | 29.25 | Not stated | 6.0 |

| 6 | Goplani et al[22] | 2008 | Prospective cohort | India | 70 | 772 | 25.60 | Urine output <400 mL or creatinine >2.0 mg/dL | 8.0 |

| 7 | Silva Jr et al[2] | 2009 | Cross-sectional | Brazil | 55 | 63,882 | 26.2 | RIFLE | 9.0 |

| 8 | Prakash et al[5] | 2010 | Prospective cohort | India | 85 | 4758 | 27.15 ± 4.66 | Not stated | 7.0 |

| 9 | Chaudhri et al[41] | 2011 | Retrospective | Pakistan | 51 | 346 | 28.0 | Not stated | 6.0 |

| 10 | Bentata et al[42] | 2012 | Retrospective cohort | Morocco | 46 | 22,320 | 29.50 ± 6.0 | RIFLE | 9.0 |

| 11 | Gurrieri et al[43] | 2012 | Retrospective study | United States | 54 | 13,372 | 28.0 | AKIN | 7.0 |

| 12 | Arrayhani et al[44] | 2013 | Prospective observational | Morocco | 37 | 5600 | 29.03 | RIFLE | 7.0 |

| 13 | Godara et al[37] | 2014 | Prospective cohort | India | 57 | 580 | 26.4 | Not stated | 8.0 |

| 14 | Mehrabadi et al[45] | 2014 | Retrospective cohort | Canada | 502 | 2,193,425 | Not stated | Not stated | 6.0 |

| 15 | Gopalakrishnanet al[15] | 2015 | Prospective observational | India | 130 | 1668 | 25.4 ± 4.73 | Urine output <400 mL or creatinine increased 1.5 times from the baseline | 8.0 |

| 16 | Hildebrand et al[4] | 2015 | Retrospective cohort | Canada | 188 | 1,918,789 | 30.0 | Not stated | 8.0 |

| 17 | Liu et al[34] | 2015 | Retrospective cohort | China | 22 | 18,589 | 30.9 ± 5.4 | KDIGO | 9.0 |

| 18 | Vineet et al[46] | 2016 | Cross-sectional | India | 52 | 570 | 26.2 | Urine output <400 mL or creatinine >2.0 mg/dL | 6.0 |

| 19 | Mehrabadi et al[45] | 2016 | Retrospective cohort | United States | 4300 | 10,969,263 | 29.90 | Not stated | 9.0 |

| 20 | Prakash et al[14] | 2016 | Retrospective observational | India | 259 | 3100 | 29.80 | Serum creatinine >1.0 mg/dL, oligoanuria >12 h, need for dialysis | 7.0 |

| 21 | Ibarra-Hernandez et al[47] | 2017 | Cross-sectional | Mexico | 18 | 75 | 24.80 | RIFLE | 8.0 |

| 22 | Huang et al[30] | 2017 | Retrospective study | China | 343 | 42,173 | 29.41 ± 5.94 | Serum creatinine >70.72 µmol/L | 8.0 |

| 23 | Silva Junior[48] | 2017 | Cross-sectional | Brazil | 92 | 389 | 27.10 | Not stated | 7.0 |

| 24 | Tangren et al[10] | 2017 | Prospective observational | United States | 246 | 46,646 | 31.0 ± 6.3 | KDIGO | 9.0 |

| 25 | Mir et al[52] | 2017 | Retrospective | India | 61 | 713 | 26.10 ± 4.3 | KDIGO | 7.0 |

| 26 | Mahesh et al[20] | 2017 | Prospective observational | India | 165 | 10,576 | 25.0 | RIFLE | 7.0 |

| 27 | Cooke et al[49] | 2018 | Prospective observational | Malawi | 26 | 332 | 26.50 | KDIGO | 9.0 |

| 28 | Prakash et al[9] | 2018 | Prospective cohort | India | 132 | 4741 | 26.80 | Serum creatinine >1.0 mg/dL, oligoanuria >12 h, need for dialysis | 7.0 |

| 29 | Liu et al[50] | 2019 | Retrospective cohort | China | 795 | 10,920 | Not stated | KDIGO | 9.0 |

| 30 | Shah et al[53] | 2020 | Retrospective cohort | United States | 32,385 | 42,190,790 | 28.0 | Not stated | 7.0 |

| 31 | Gaber et al[54] | 2021 | Prospective observational | Egypt | 40 | 4000 | 28.7 ± 5.9 | KDIGO | 6.0 |

The etiology of PR-AKI was multifactorial in many patients. Almost all studies were retrospective cohort studies and were from a single center. The definition of PR-AKI varied considerably across these studies—1 study defined PR-AKI as increase in serum creatinine (Scr) level by approximately 1.5 times from baseline or decrease in urine output to<400 mL; 6 studies defined AKI based on the KDIGO criteria; 5 studies defined AKI according to the RIFLE classification, 1 study defined AKI based on the Acute Kidney Injury Network classification; 7 studies defined PR-AKI according to the level of creatinine, 3 studies defined PR-AKI as Scr level>1.0 mg/dL, 1 study defined PR-AKI as Scr level >1.5 mg/dL, 1 study defined PR-AKI as Scr level >1.8 mg/dL, and 2 studies defined PR-AKI as Scr level >2.0 mg/dL. The remaining 11studies did not specify criteria for diagnosing AKI.

3.1. Characteristics of the studies

In the meta-analysis of 31 studies, the pooled mean age of the participants was 28.2 years (95% CI 27.6–28.8; I2 = 98.5%). By meta-analysis, 36.1% (95% CI 22.9–51.8, 18 studies, I2 = 98.4%) of patients were primigravida, while 56.9% (95% CI 52.0–61.7, 17 studies, I2 = 78.0%) of patients were multigravida. In term of onset of AKI, 12.6% (95% CI 7.3–20.8, 11 studies, I2 = 86.3%), 15.7% (95% CI 9.7–24.2, 11 studies, I2 = 84.5%), 69.0% (95% CI 51.5–82.3, 13 studies, I2 = 96.1%), and 48.6% (95% CI 36.3–61.2, 8 studies, I2 = 86.0%) of patients presented with PR-AKI during the first trimester, second trimester, third trimester, and postpartum period, respectively. Only 49.3% of patients received antenatal care (95% CI 25.9–72.9, 6 studies, I2 = 94.9%).

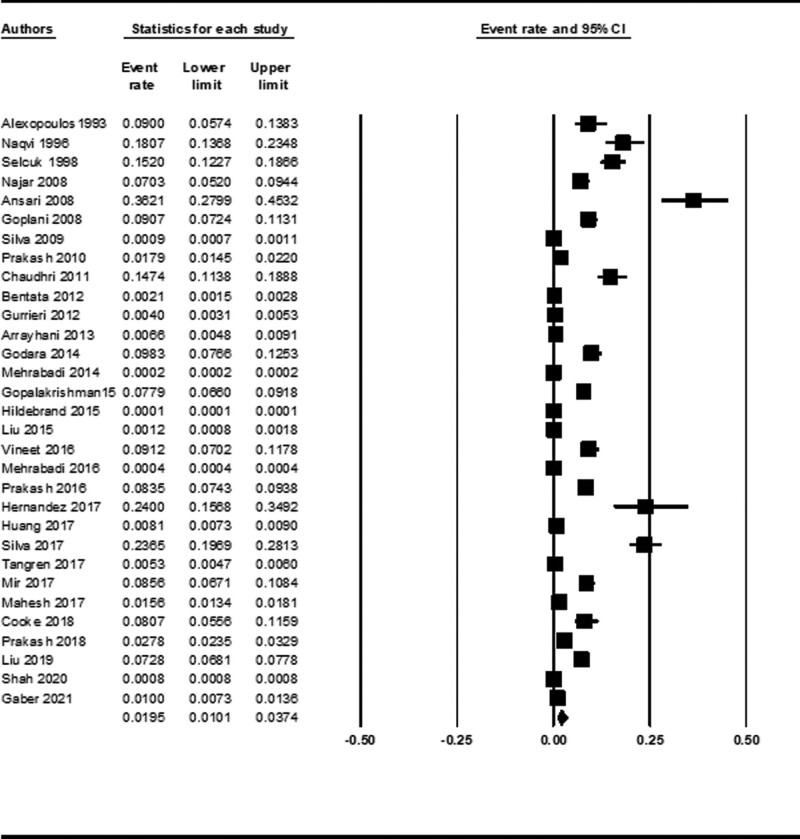

3.2. Incidence and causes of PR-AKI during pregnancy

The incidence of AKI during pregnancy and puerperium was 1.95% (95% CI 1.01–3.73) using data from 31 studies (Fig. 2). By meta-analysis of 29 studies, 36.6% (95% CI 29.1–44.7, I2 = 96.8%) patients had preeclampsia and hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, 21.0% (95% CI 12.8–32.5, 18 studies, I2 = 96.5%) had septic abortion, 16.6% (95% CI 9.1–28.4, 24 studies, I2 = 98.4%) had other causes or unknown causes of abortion, 15.1% (95% CI 11.5–19.6, 24 studies, I2 = 88.1%) had antepartum hemorrhage, 14.1% (95% CI 5.6–31.4, 3 studies, I2 = 74.7%) had acute gastroenteritis, 13.3% (95% CI 9.3–18.7, 13 studies, I2 = 80.4%) had HELLP syndrome, 13.2% (95% CI 9.7–17.8, 28 studies, I2 = 91.3%) had postpartum hemorrhage, 5.8% (95% CI 3.6–9.1, 29 studies, I2 = 92.1%) had acute pyelonephritis, 4.5% (95% CI 2.6–7.5, 6 studies, I2 = 59.1%) had acute fatty liver of pregnancy, and 3.5% (95% CI 1.3–8.7, 6 studies, I2 = 82.5%) had glomerular disease.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of incidence of PR-AKI. CI = confidence interval, PR-AKI = pregnancy-related acute kidney injury.

3.3. Maternal outcomes

In the meta-analysis of 25 studies, the pooled mortality rate was an average of 12.7% (Table 2). Ten studies reported the cause of maternal death, including sepsis, antepartum hemorrhage, preeclampsia/HELLP syndrome, and adult respiratory distress syndrome.

Table 2.

Summary of maternal and fetal outcomes.

| Outcomes | No. of studies | Event rate% (95% CI) | I 2 index (%) | Egger test P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal outcomes | ||||

| Complete recovery | 25 | 70.6% (62.7–77.5) | 89.6 | .52 |

| Partial recovery | 22 | 14.7% (10.1–21.0) | 86.0 | .01 |

| Dialysis dependence | 15 | 8.5% (4.7–14.8) | 84.0 | .050 |

| Required hemodialysis | 27 | 37.2% (26.0–49.9) | 98.7 | .001 |

| Required peritoneal dialysis | 7 | 10.0% (5.9–16.5) | 75.3 | .07 |

| Required both modalities | 4 | 8.2% (4.1–15.7) | 53.0 | .12 |

| Mortality | 25 | 12.7% (9.0–17.7) | 96.3 | .001 |

| Fetal outcomes | ||||

| Live births | 21 | 70.0% (61.2–77.4) | 93.4 | .80 |

| Intrauterine death | 11 | 18.6% (12.8–26.2) | 76.5 | .12 |

| Preterm | 4 | 28.5% (14.7–48.1) | 90.5 | .05 |

| Perinatal mortality | 20 | 25.4% (18.1–34.4) | 94.6 | .78 |

Furthermore, 70.6% of patients with PR-AKI achieved complete recovery,14.7% achieved partial recovery, and 8.5% remained dependent on dialysis. In terms of dialysis modality in patients with PR-AKI, 37.2% of patients required hemodialysis (HD), 10.0% required peritoneal dialysis (PD), and 8.2% required both HD and PD due to inadequate ultrafiltration by PD alone. The indications for HD included oligo/anuria, hyperkalemia, uremia, metabolic acidosis, and acute pulmonary edema.

3.4. Fetal outcomes

By the meta-analysis, 70.0% of patients had live births (Table 2). The incidence of intrauterine death was 18.6%. The offspring of mothers with PR-AKI were born earlier, with a pooled rate of 28.5%. The mortality rate among perinatal infants was 25.4%.

3.5. Investigation of heterogeneity

In subgroup analysis according to developed vs underdeveloped countries (definition by World Economic Situation and Prospects) on the incidence of AKI, the pooled incidence of PR-AKI in developed countries was 0.14% (95% CI 0.08%–0.23%; Table 3). Surprisingly, the high pooled incidence of PR-AKI was observed in underdeveloped countries (4.11%; 95% CI 2.38%–7.01%). In terms of AKI definition, based on RIFLE or KDIGO criteria, the pooled incidence of PR-AKI was 1.31% (95% CI 0.47%–3.61%), while the high pooled incidence of PR-AKI was reported in studies that used other definitions (2.42%; 95% CI 1.21%–4.79%).

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of incidence of PR-AKI.

| Outcomes | No. of studies | Event rate (95% CI) | I2 index |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence of PR-AKI | 31 | 1.95% (1.01–3.73) | 99.94 |

| Subgroup analysis based on | |||

| Country classification* | |||

| Developed economies | 7 | 0.14% (0.08–0.23) | 99.87 |

| Developing economies | 24 | 4.11% (2.38–7.01) | 99.48 |

| AKI definition | |||

| RIFLE/KDIGO | 11 | 1.31% (0.47–3.61) | 99.67 |

| Others | 20 | 2.42% (1.21–4.79) | 99.94 |

| Study quality | |||

| Poor and fair | 8 | 5.59% (0.35–49.71) | 99.92 |

| Good | 23 | 1.35% (0.49–3.67) | 99.94 |

We performed a sensitivity analysis to assess the consistency of the results based on the study quality; the pooled incidence of PR-AKI was 1.35% (95% CI 0.49–3.68) after excluding the study that had poor and fair quality. The high incidence of PR-AKI was observed in poor and fair study quality.

3.6. Publication bias

As the Egger test results, most of the interested outcomes were mainly insignificant (Table 2).

4. Discussion

In this meta-analysis of >58 million pregnancies, the incidence of AKI during pregnancy was 2%. AKI during pregnancy is associated with increased morbidity in the mother and fetus. The incidence of AKI varies based on the geographical area, with most studies conducted in the Indian subcontinent. Since the time span of study inclusion was >30 years, various definitions of AKI were used. Recently, the KDIGO criteria have been widely adopted by professional societies as the standardized criteria for AKI. The criteria provide a much higher estimated incidence (10-fold increase) of AKI than Code-Classification AKI.[17,18]

The physiological changes and increase in glomerular filtration rate with the reduction in Scr levels during pregnancy are associated with increased difficulty for early and accurate diagnosis of PR-AKI.[19] In previous studies, the incidence of PR-AKI was 7% to 9 % in the Indian subcontinent,[20] 2.5% in China,[21] and 1% to 28% in developed countries. Our meta-analysis demonstrated that the pooled incidence of PR-AKI in developed countries was only 0.14%. Unfortunately, the high pooled incidence of PR-AKI (4.11%) was observed in underdeveloped countries. Only 49.3% of patients received antenatal care. Therefore, antenatal care should be emphasized in public health care to prevent septic abortion and pregnancy-induced hypertension, especially in underdeveloped countries.

In this study, approximately 50% of patients developed postpartum PR-AKI. Similarly, Sivakumar et al[22] reported that 74.5% of patients developed PR-AKI during the postpartum period. However, most of the studies showed predominant incidence of PR-AKI in the trimester. In our meta-analysis, the pooled AKI during the first trimester, second trimester, third trimester, and postpartum were reported at 12.6%, 15.7%, 69%, and 48.6%, respectively. Improvements in antenatal care and early referral to nephrologists to decrease the risk of kidney injury in PR-AKI should be highlighted. The mean age of our patients was 28.2 years.[22–26] In a study by Kabbali et al,[27] age >38 years was significantly associated with unfavorable outcomes and increased perinatal complications. Therefore, the pooled incidence of PR-AKI in this meta-analysis might be underestimated, especially in advanced maternal age.

Preeclampsia and pregnancy-related hypertension were responsible for 36.6% of PR-AKI cases in our study. Preeclampsia is one of the most important causes of AKI during pregnancy, especially in Indian studies[11]; however, most patients with this condition do not develop AKI.[28] The frequency of AKI in preeclampsia varied between 24% and 35% in different centers in India.[11,29] This was the most frequent cause of PR-AKI in this meta-analysis. Preeclampsia is also the main cause of severe PR-AKI and typically occurs during the third trimester and postpartum period.[30] The frequency of preeclampsia ranges between 2% and 7% in healthy nulliparous women and increases substantially in women with multiple gestations, chronic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease.[31] The effect of preeclampsia on endothelial injury and vasoconstriction, which would be expected to lower the glomerular filtration rate,[32,33] may affect long-term renal function. The causes of PR-AKI have changed over time from septic abortion in the past to preeclampsia and hemorrhagic shock in the present era due to increased attention of health care professionals to prenatal cases.

The HELLP syndrome is a serious disorder in pregnancy, accounting for 15% to 40% of all cases of PR-AKI[34] and up to 54% to 60% of severe cases.[35] The HELLP syndrome is considered a continuum of preeclampsia. In our study, HELLP syndrome accounted for 13.3% of total PR-AKI cases, which was a similar rate associated with other causes, such as acute gastroenteritis, septic abortion, postpartum hemorrhage, and acute pyelonephritis.

AKI during pregnancy was associated with a higher risk of maternal death. In our study, the mortality rate was 12.7%. The heterogeneity was quite high (I2 = 96.3%), which likely resulted from a higher incidence of sepsis, the main cause of maternal mortality, in developing countries. In contrast, developed countries had a higher incidence of pregnancy-induced hypertension and favorable socioeconomic factors, leading to lower maternal mortality. The mortality rate was approximately 23% to 33%,[3,29] mostly in developing countries, while it was 2.7% to 4.3% in developed countries.[36] Maternal mortality also decreased based on the time period and location of the study. The overall mortality rate declined from 20% in the 1980s to 5.79% in 2013–2014[37]

In previous studies, 16% to 73% of pregnant women with AKI required dialysis treatment.[30] In our meta-analysis, approximately 40% of PR-AKI cases received HD, and 10% of cases needed PD. However, the recovery rate of renal function was favorable (70.6%)—only 8.5% of patients were dependent on dialysis after delivery and 14.7% had subsequent chronic kidney disease. Early prevention and treatment should focus more on reducing risk in antenatal care and consider preeclampsia medication in high-risk populations.

The fetal outcome was satisfactory, with survival in 70% cases. There were 28.5% cases of preterm delivery, 18.6% cases of intrauterine death, and 25.4% cases of perinatal infant mortality. Previous studies revealed fetal lost deliveries of 81.3%.[34] The results of the literature reviews in China showed that the incidence of stillbirth or neonatal mortality can reach 30%. The incidence of abortion and stillbirth in this study was nearly equivalent to that reported in previous studies; therefore, improvement in maternal and fetal health is needed.

The merit of the present study is the accumulation of various studies over a long period of time (>30 years), which encompassed >57 million pregnancies. Several meta-analyses have investigated PR-AKI; however, most studies have focused on pregnancy outcomes, such as kidney, maternal, and fetal outcomes. In the present meta-analysis, we attempted to demonstrate the incidence of PR-AKI in a pooled analysis of 40,428 PR-AKI cases. The outcomes in various aspects, especially kidney outcomes, were emphasized. The incidence of PR-AKI in different parts of the world should be considered in the future to help reduce the global burden of AKI.

The following are the limitations of this study. Differences in the definition of AKI due to changes in criteria from different time points and follow-up time contributed to heterogeneous results. In addition, since this study aimed to explore the incidence of PR-AKI, we did not perform subgroup analysis of each variable. Most of the included studies were from the Indian subcontinent, which is associated with a publication bias. Additionally, we were unable to assess long-term kidney-related endpoints.

In conclusion, data obtained from our meta-analysis show that the overall rate of PR-AKI is decreasing worldwide, indicating improvements in and increased awareness of antenatal care. Although the maternal, fetal, and kidney outcomes were favorable, the absolute numbers of deaths and percentage of patients with irreversible kidney damage remained unacceptably high. The most common causes of PR-AKI, including pregnancy-induced hypertension, hemorrhage, and septic abortion/abortion could be prevented, early identified, and treatment. Our analysis serves to encourage future studies to investigate improvements in antenatal care and perform early referral to nephrologists to increase patient safety and mitigate the risk of further kidney injury in PR-AKI.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Thanaphan Thitivichienlert for helping with data extraction. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing

Author contributions

Conceptualization: TT, PS

Methodology: PS

Validation: TT, PS

Formal analysis:PS

Resource: TN, TT, PS

Writing manuscript: TT, PS

Project administration: TT

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations:

- AKI =

- acute kidney injury

- CI =

- confidence interval

- CKD =

- chronic kidney disease

- HD =

- hemodialysis

- HELLP =

- hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets count

- KDIGO =

- Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes

- PD =

- peritoneal dialysis

- PR-AKI =

- pregnancy-related acute kidney injury

- Scr =

- serum creatinine

How to cite this article: Trakarnvanich T, Ngamvichchukorn T, Susantitaphong P. Incidence of acute kidney injury during pregnancy and its prognostic value for adverse clinical outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2022;101:30(e29563).

This work was supported by grants from Navamindradhiraj University (grant no. 15/64).

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

For this type of study, ethical approval is exempted and not required.

This systematic review and meta-analysis was registered in the Prospero International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42021274704).

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

AKI = acute kidney injury, AKIN = acute kidney injury network, KDIGO = Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes.

CI = confidence interval.

AKI = acute kidney injury, CI = confidence interval, KDIGO = Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes, PR-AKI = pregnancy-related acute kidney injury.

World Economic situation and Prospects.

References

- [1].Lindheimer MD, Katz AI, Ganeval D, et al. Acute renal failure in pregnancy. Lazarus JM, Brenner BM, eds. In: Acute Renal Failure. 3rd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone. 1993;417–439. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Silva GB, Jr, Monteiro FA, Mota RM, et al. Acute kidney injury requiring dialysis in obstetric patients: a series of 55 cases in Brazil. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279:131–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Najar MS, Shah AR, Wani IA, et al. Pregnancy related acute kidney injury: a single center experience from the Kashmir Valley. Indian J Nephrol. 2008;18:159–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hildebrand AM, Liu K, Shariff SZ, et al. Characteristics and outcome of AKI treated with dialysis during pregnancy and the postpartum period. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:3085–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Prakash J, Niwas SS, Parekh A, et al. Acute kidney injury in late pregnancy in developing countries. Ren Fail. 2010;32:309–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chugh KS, Sakhuja V, Malhotra HS, Pereira BJ. Changing trends in acute renal failure in third-world countries—Chandigarh study. Q J Med. 1989;73:1117–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Prakash J, Tripathi K, Malhotra V, et al. Acute renal failure in eastern India. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1995;10:2009–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mehrabadi A, Dahhou M, Joseph KS, et al. Investigation of a rise in obstetric acute renal failure in the United States, 1999-2011. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:899–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Prakash J, Ganiger VC, Prakash S, et al. Acute kidney injury in pregnancy with special reference to pregnancy-specific disorders: a hospital based study (2014-2016). J Nephrol. 2018;31:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tangren JS, Powe CE, Ankers E, et al. Pregnancy outcomes after clinical recovery from AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:1566–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Karimi Z, Malekmakan L, Farshadi M. The prevalence of pregnancy-related acute renal failure in Asia: a systematic review. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2017;28:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Prakash J, Kumar H, Sinha DK, et al. Acute renal failure in pregnancy in a developing country: twenty years of experience. Ren Fail. 2006;28:309–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Prakash J, Vohra R, Wani IA, et al. Decreasing incidence of renal cortical necrosis in patients with acute renal failure in developing countries: a single-centre experience of 22 years from Eastern India. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1213–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Prakash J, Pant P, Prakash S, et al. Changing picture of acute kidney injury in pregnancy: study of 259 cases over a period of 33 years. Indian J Nephrol. 2016;26:262–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gopalakrishnan N, Dhanapriya J, Muthukumar P, et al. Acute kidney injury in pregnancy—a single center experience. Ren Fail. 2015;37:1476–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLOS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sawhney S, Fluck N, Marks A, et al. Acute kidney injury—how does automated detection perform? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30:1853–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bedford M, Stevens PE, Wheeler TW, et al. What is the real impact of acute kidney injury? BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Van Hook JW. Acute kidney injury during pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;57:851–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mahesh E, Puri S, Varma V, et al. Pregnancy-related acute kidney injury: an analysis of 165 cases. Indian J Nephrol. 2017;27:113–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wang F, Xing T, Wang N, Huang Y. A clinical study of pregnancy-associated renal insufficiency. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2011;34:34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sivakumar V, Sivaramakrishna G, Sainaresh VV, et al. Pregnancy-related acute renal failure: a ten-year experience. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2011;22:352–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Khalil MA, Azhar A, Anwar N, et al. Aetiology, maternal and foetal outcome in 60 cases of obstetrical acute renal failure. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2009;21:46–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Alexopoulos E, Tambakoudis P, Bili H, et al. Acute renal failure in pregnancy. Ren Fail. 1993;15:609–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Arora N, Mahajan K, Jana N, et al. Pregnancy-related acute renal failure in eastern India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;111:213–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hachim K, Badahi K, Benghanem M, et al. Obstetrical acute renal failure. Experience of the nephrology department, Central University Hospital ibn Rochd, Casablanca. Nephrologie. 2001;22:29–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kabbali N, Tachfouti N, Arrayhani M, et al. Outcome assessment of pregnancy-related acute kidney injury in Morocco: a national prospective study. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 2015;26:619–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gammill HS, Jeyabalan A. Acute renal failure in pregnancy. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(suppl):S372–S384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Patel ML, Sachan R, RadheshyamSachan P, et al. Acute renal failure in pregnancy: tertiary centre experience from north Indian population. Niger Med J. 2013;54:191–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Huang C, Chen S. Acute kidney injury during pregnancy and puerperium: a retrospective study in a single center. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Duckitt K, Harrington D. Risk factors for pre-eclampsia at antenatal booking: systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ. 2005;330:565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wallukat G, Homuth V, Fischer T, et al. Patients with preeclampsia develop agonistic autoantibodies against the angiotensin AT1 receptor. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:945–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Roberts JM, Redman CW. Preeclampsia: more than pregnancy induced hypertension. Lancet. 1993;341:1447–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Liu YM, Bao HD, Jiang ZZ, et al. Pregnancy-related acute kidney injury and a review of the literature in China. Intern Med. 2015;54:1695–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ye W, Shu H, Yu Y, et al. Acute kidney injury in patients with HELLP syndrome. Int Urol Nephrol. 2019;51:1199–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Munnur U, Karnad DR, Bandi VD, et al. Critically ill obstetric patients in an American and an Indian public hospital: comparison of case-mix, organ dysfunction, intensive care requirements, and outcomes. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:1087–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Godara SM, Kute VB, Trivedi HL, et al. Clinical profile and outcome of acute kidney injury related to pregnancy in developing countries: a single-center study from India. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2014;25:906–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Naqvi R, Akhtar F, Ahmed E, et al. Acute renal failure of obstetrical origin during 1994 at one center. Ren Fail. 1996;18:681–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Selcuk NY, Tonbul HZ, San A, et al. Changes in frequency and etiology of acute renal failure in pregnancy (1980-1997). Ren Fail. 1998;20:513–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ansari MR, Laghari MS, Solangi KB. Acute renal failure in pregnancy: one year observational study at Liaquat University Hospital, Hyderabad. J Pak Med Assoc. 2008;58:61–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Chaudhri N, But G, Masroor I. Spectrum and short term outcome of pregnancy related acute renal failure among women. Ann Pak Inst Med Sci. 2011;7:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Bentata Y, Housni B, Mimouni A, et al. Acute kidney injury related to pregnancy in developing countries: etiology and risk factors in an intensive care unit. J Nephrol. 2012;25:764–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Gurrieri C, Garovic VD, Gullo A, et al. Kidney injury during pregnancy: associated comorbid conditions and outcomes. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;286:567–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Arrayhani M, El Youbi R, Sqalli T. Pregnancy-related acute kidney injury: experience of the nephrology unit at the university hospital of Fez, Morocco. ISRN Nephrol. 2013;2013:109034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Mehrabadi A, Liu S, Bartholomew S, et al.Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and the recent increase in obstetric acute renal failure in Canada: population based retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2014;349:g4731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Vineet M, Preeti G, Rohina A, et al.. A single-centre experience of obstetric acute kidney injury. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2016;127:899–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ibarra-Hernández M, Orozco-Guillén OA, de la Alcantar-Vallín ML, et al. Acute kidney injury in pregnancy and the role of underlying CKD: a point of view from México. J Nephrol. 2017;30:773–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Silva Junior GBD, Saintrain SV, Castelo GC, et al. Acute kidney injury in critically ill obstetric patients: a cross-sectional study in an intensive care unit in Northeast Brazil. J Bras Nefrol. 2017;39:357–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Cooke WR, Hemmilä UK, Craik AL, et al. Incidence, aetiology and outcomes of obstetric-related acute kidney injury in Malawi: a prospective observational study. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Liu D, He W, Li Y, et al. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in hospitalized pregnant women in China. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Mir MM, Najar MS, Chaudary AM, et al. Postpartum acute kidney injury: experience of a tertiary care center. Indian J Nephrol. 2017;27:181–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Goplani KR, Shah PR, Gera DN, et al. Pregnancy-related acute renal failure: a single-center experience. Indian J Nephrol. 2008;18:17–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Shah S, Meganathan K, Christianson AL, et al. Pregnancy-related acute kidney injury in the United States: clinical outcomes and health care utilization. Am J Nephrol. 2020;51:216–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Gaber TZ, Shemies RS, Baiomy AA, et al. Acute kidney injury during pregnancy and puerperium: an Egyptian hospital-based study. J Nephrol. 2021;34:1611–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.