Abstract

Background

Few data are available regarding changes in mitral regurgitation (MR) severity with guideline-recommended medical therapy (GRMT) in heart failure (HF). Our aim was to evaluate the evolution and impact of MR after GRMT in the Biology study to Tailored treatment in chronic heart failure (BIOSTAT-CHF).

Methods

A retrospective post-hoc analysis was performed on HF patients from BIOSTAT-CHF with available data on MR status at baseline and at 9-month follow-up after GRMT optimization. The primary endpoint was a composite of all-cause death or HF hospitalization.

Results

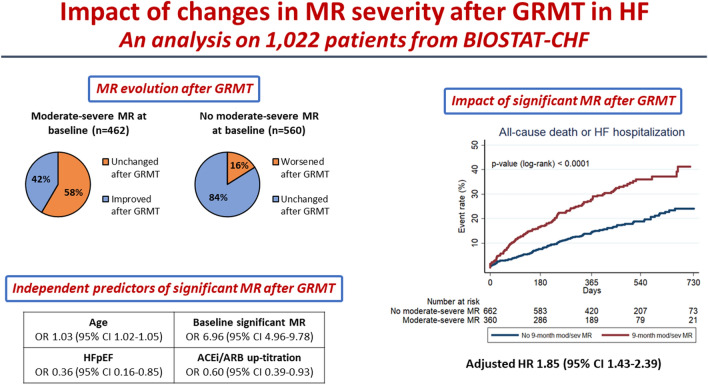

Among 1022 patients with data at both time-points, 462 (45.2%) had moderate-severe MR at baseline and 360 (35.2%) had it at 9-month follow-up. Regression of moderate-severe MR from baseline to 9 months occurred in 192/462 patients (41.6%) and worsening from baseline to moderate-severe MR at 9 months occurred in 90/560 patients (16.1%). The presence of moderate-severe MR at 9 months, independent from baseline severity, was associated with an increased risk of the primary endpoint (unadjusted hazard ratio [HR], 2.03; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.57–2.63; p < 0.001), also after adjusting for the BIOSTAT-CHF risk-prediction model (adjusted HR, 1.85; 95% CI 1.43–2.39; p < 0.001). Younger age, LVEF ≥ 50% and treatment with higher ACEi/ARB doses were associated with a lower likelihood of persistence of moderate-severe MR at 9 months, whereas older age was the only predictor of worsening MR.

Conclusions

Among patients with HF undergoing GRMT optimization, ACEi/ARB up-titration and HFpEF were associated with MR improvement, and the presence of moderate-severe MR after GRMT was associated with worse outcome.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00392-022-01991-7.

Keywords: Mitral regurgitation, Heart failure, GRMT, Valvular heart disease, Mortality, Hospitalization

Introduction

Mitral regurgitation is the most common valvular heart disease in patients with heart failure (HF) [1–3]. It has a strong prognostic impact in both acute and chronic settings [4–17], and has emerged as a potential therapeutic target in HF patients [18, 19]. Medical therapy with β-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) or angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors (ARNI) is the mainstay of treatment in HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) [20–23]. Initiation and up-titration of these agents to target doses is recommended in current HF guidelines [20, 23], and represents a crucial step in HF management before evaluating interventional procedures. The Cardiovascular Outcomes Assessment of the MitraClip Percutaneous Therapy for Heart Failure Patients with Functional Mitral Regurgitation (COAPT) trial enrolled symptomatic patients with persistent MR despite attempted optimization of guideline-recommended medical therapy (GRMT) for HF, and demonstrated the superiority of percutaneous mitral valve repair plus GRMT compared to GRMT alone in a carefully selected population [19, 24, 25]. Of note, reduction in MR severity has been described in HF patients treated with β-blockers, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors or cardiac resynchronization therapy [26–31]. Hence, further assessment of changes in MR severity after GRMT optimization and an assessment of their impact on patients’ outcomes seem warranted.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the evolution and prognostic impact of MR after up-titration of GRMT in patients included in Biology Study to Tailored Treatment in Chronic Heart Failure (BIOSTAT-CHF), a prospective observational multicentre study enrolling patients with worsening chronic or new-onset HF undergoing GRMT optimization [32–34].

Methods

Study population

The index cohort of BIOSTAT-CHF recruited 2516 patients from 69 centres in 11 European countries between 2010 and 2014. Included patients had symptoms of new-onset or worsening chronic HF, with either a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤ 40% or B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) > 400 pg/mL and/or N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-proBNP) > 2000 pg/mL and were treated with oral or intravenous furosemide ≥ 40 mg/day or equivalent at inclusion. Patients should not have been previously treated with ACEi/ARBs and/or β-blockers or should have received ≤ 50% of the target doses of these drugs at inclusion, with an anticipated initiation or up-titration of ACEi/ARBs and/or β-blockers by the treating physician. In the first 3 months (optimization phase), initiation or up-titration of ACEi/ARBs and/or β-blockers was specified according to the 2008 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines [35]. In the subsequent 6 months (stabilization phase), no further treatment optimization was required, except in case of changes in clinical status. At 9 month, a mandated follow-up visit was performed, including clinical evaluation and echocardiography. Subsequent follow-up was performed at 6 month intervals by means of clinical visit or phone contact, until the end of follow-up on April 1, 2015. The study was approved by the ethics committees of all participating centres and all patients provided written informed consent.

For the purposes of the present study, patients from the index cohort with available MR data at both baseline and 9 months (n = 1022) were included. The study flowchart is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Study definitions and endpoints

Patients underwent two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography at baseline and at 9-month follow-up using a commercially available echocardiography (3.5 MHz probe). According to the study protocol, MR was evaluated using two-dimensional and color Doppler echocardiography [36], and the presence of moderate or severe MR (as compared to no or mild MR) was recorded. Left ventricular (LV) diameters, LVEF according to the modified Simpson rule, and left atrium diameter were also quantified and reported. Baseline clinical characteristics, quality-of-life (QoL) measures and laboratory data at inclusion and 9 months, and clinical outcomes at follow-up were also assessed.

The primary endpoint was the composite of all-cause mortality or HF hospitalization. Secondary endpoints were all-cause mortality, cardiovascular (CV) mortality and HF hospitalization as individual outcomes.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range, IQR), as appropriate, and were compared with the unpaired Student’s t test or the Mann–Whitney U test, respectively. Categorical variables are presented as number and percentages and were compared with the χ2 test. Baseline clinical characteristics, echocardiography data, laboratory data, QoL indexes, primary and secondary endpoints were compared between patients with vs. without 9-month moderate-severe MR and between the following four groups defined according to baseline and 9 month moderate-severe MR: patients without moderate-severe MR at baseline and 9 months (unchanged); patients with moderate-severe MR at baseline and without moderate-severe MR at 9 months (improved); patients without moderate-severe MR at baseline and with moderate-severe MR at 9 months (worsened); and patients with moderate-severe MR at baseline and 9 months (unchanged). The Kaplan–Meier method (log-rank test) was used to evaluate the first occurrence of primary and secondary endpoint in patients with or without 9-month moderate-severe MR and in the four groups describing MR evolution (censoring follow-up at 2 years). Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was also performed to evaluate the prognostic impact of 9-month moderate-severe MR on primary and secondary endpoints. Univariable analysis and multiple multivariable models were performed to adjust the presence of 9 month MR for the several clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic covariates of interest, including the previously validated BIOSTAT-CHF risk prediction models (model 5) [33]. Results of the Cox regression analyses are reported as unadjusted or adjusted hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Multivariable binary logistic regression analysis was also performed to identify independent predictors of moderate-severe MR at 9-month follow-up. Variables with a univariate p value < 0.10 or variables judged to be of clinical relevance were included into the final multivariable model. Results of the binary logistic regression are presented as odds ratio with 95% CI. The C statistic and Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test were used to evaluate the discrimination, calibration and fit of the multivariable model.

All reported p values are two sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 13.0 (STATA Corp., College Station, Texas).

Results

Among the 1,022 patients included in the present study (Supplementary Fig. 1), 462 (45.2%) had moderate-severe MR at baseline and 360 (35.2%) had it at 9-month follow-up after the optimization phase. Regarding the evolution of MR over time, MR severity remained unchanged between baseline and 9 months in 470 patients (46.0%) without, and in 270 patients (26.4%) with, moderate-severe MR. Conversely, MR improved from moderate-severe at baseline to no or mild MR at 9 months in 192 patients (18.8% of all patients or 41.6% of those with moderate-severe MR at baseline). Conversely, 90 patients developed new moderate-severe MR by 9 months (8.8% of all patients or 16.1% of those with no or mild MR at baseline).

Patients’ characteristics

Detailed clinical, echocardiographic, laboratory, and QoL characteristics across the four groups defined according to baseline and 9-month MR are reported in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Baseline clinical characteristics among patients included as compared to those excluded from the study are reported in Supplementary Table 3.

Compared to patients with no or mild MR, patients with moderate-severe MR at 9 months were older, had lower body mass index, and were more likely to have a history of chronic kidney disease, prior cardiac device therapy, and worsening chronic HF as cause of the baseline visit (Table 1). These patients also had more advanced symptoms (NYHA class) at 9 months and lower systolic blood pressure at baseline and 9 months compared to patients with no or mild MR. The percentage of patients who achieved the ACEi/ARB target dose at 3 months and the mean ACEi/ARB optimal dose fraction at 3 months were lower in patients with moderate-severe MR at 9 months. These differences were not observed for β-blockers.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics in patients with vs. without 9-month moderate-severe MR

| Overall (n = 1022) |

Moderate or severe MR (n = 360) |

No or mild MR (n = 662) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 66.9 ± 12.2 | 69.2 ± 11.1 | 65.7 ± 12.6 | < 0.001 |

| Men | 786 (76.9) | 273 (75.8) | 513 (77.5) | 0.548 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.8 ± 5.4 | 27.0 ± 4.6 | 28.3 ± 5.7 | < 0.001 |

| HF hospitalization in last year | 284 (27.8) | 112 (31.1) | 172 (26.0) | 0.080 |

| Primary ischemic HF aetiology | 442 (43.9) | 168 (47.3) | 274 (42.0) | 0.105 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Hypertension | 629 (61.6) | 221 (61.4) | 408 (61.6) | 0.939 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 285 (27.9) | 99 (27.5) | 186 (28.1) | 0.839 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 410 (40.1) | 155 (43.1) | 255 (38.5) | 0.158 |

| Myocardial infarction | 369 (36.1) | 139 (38.6) | 230 (34.7) | 0.219 |

| PCI | 207 (20.3)7.0 | 61 (16.9) | 146 (22.1) | 0.052 |

| CABG | 149 (14.6) | 59 (16.4) | 90 (13.6) | 0.227 |

| Prior valve surgery | 74 (7.2) | 21 (5.8) | 53 (8.0) | 0.200 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 90 (8.8) | 31 (8.6) | 59 (8.9) | 0.871 |

| COPD | 154 (15.1) | 52 (14.4) | 102 (15.4) | 0.681 |

| Stroke | 93 (9.1) | 33 (9.2) | 60 (9.1) | 0.956 |

| Current malignancy | 27 (2.6) | 12 (3.3) | 15 (2.3) | 0.309 |

| CKD | 231 (22.6) | 97 (26.9) | 134 (20.2) | 0.014 |

| Device therapy | 0.018 | |||

| Pacemaker | 67 (6.6) | 30 (8.3) | 37 (5.6) | |

| ICD | 67 (6.6) | 28 (7.8) | 39 (5.9) | |

| CRT-P | 19 (1.9) | 8 (2.2) | 11 (1.7) | |

| CRT-D | 71 (7.0) | 33 (9.2) | 38 (5.7) | |

| Type of baseline visit | 0.326 | |||

| Inpatient hospitalization | 617 (60.4) | 210 (58.3) | 407 (61.5) | |

| Outpatient clinic | 405 (39.6) | 150 (41.7) | 255 (38.5) | |

| Reason for baseline visit | < 0.001 | |||

| Worsening HF | 444 (43.4) | 185 (51.4) | 259 (39.1) | |

| New-onset HF | 311 (30.4) | 76 (21.1) | 235 (35.5) | |

| Other | 267 (26.1) | 99 (27.5) | 168 (25.4) | |

| NYHA class | ||||

| Baseline | 0.170 | |||

| I | 24 (2.4) | 4 (1.1) | 20 (3.1) | |

| II | 454 (45.3) | 156 (43.7) | 298 (46.1) | |

| III | 436 (43.5) | 165 (46.2) | 271 (42.0) | |

| IV | 89 (8.9) | 32 (9.0) | 57 (8.8) | |

| 9 months | < 0.001 | |||

| I | 190 (19.2) | 38 (10.8) | 152 (23.7) | |

| II | 569 (57.4) | 209 (59.5) | 360 (56.2) | |

| III | 219 (22.1) | 97 (27.6) | 122 (19.0) | |

| IV | 14 (2.0) | 7 (2.0) | 7 (1.1) | |

| SBP | ||||

| Baseline | 125 ± 22 | 123 ± 21 | 126 ± 22 | 0.012 |

| 9 months | 124 ± 21 | 120 ± 20 | 127 ± 21 | < 0.001 |

| HF therapy | ||||

| ACEi/ARB | ||||

| Baseline use | 802 (78.5) | 278 (77.2) | 524 (79.2) | 0.473 |

| 3-month use | 934 (91.4) | 333 (92.5) | 601 (90.8) | 0.351 |

| 3-month target dose | 270 (26.4) | 71 (19.7) | 199 (30.1) | < 0.001 |

| 3-month optimal dose fraction (%) | 53 ± 40 | 48 ± 37 | 56 ± 42 | 0.002 |

| β-Blockers | ||||

| Baseline use | 867 (84.8) | 310 (86.1) | 557 (84.1) | 0.401 |

| 3-month use | 955 (93.4) | 349 (96.9) | 606 (91.5) | 0.001 |

| 3-month target dose | 141 (13.8) | 49 (13.6) | 92 (13.9) | 0.899 |

| 3-month optimal dose fraction (%) | 38 ± 30 | 37 ± 28 | 38 ± 31 | 0.881 |

| MRA baseline use | 562 (55.0) | 216 (60.0) | 346 (52.3) | 0.018 |

| Loop diuretic baseline use | 1019 (99.7) | 360 (100.0) | 659 (99.6) | 0.201 |

| Digoxin baseline use | 185 (18.1) | 75 (20.8) | 110 (16.6) | 0.094 |

Data are presented as n (%) and mean ± standard deviation. Bold values represent significant p-values (p < 0.05)

ACEi angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI body mass index; CABG coronary artery bypass graft; CKD chronic kidney disease; COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRT-D cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillator; CRT-P cardiac resynchronization therapy with pacemaker; HF heart failure; ICD implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; MR mitral regurgitation; MRA mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NYHA New York Heart Association; PCI percutaneous coronary intervention; SBP systolic blood pressure

Median LVEF at 9 months was lower in patients with 9-month moderate-severe MR compared to those with no or mild MR (Table 2). Hence, patients with 9 month moderate-severe MR were more likely to have HFrEF at 9 months (LVEF < 40%) rather than HF with mid-range (HFmrEF; LVEF 40–49%) or preserved LVEF (HFpEF; LVEF ≥ 50%). Moreover, median LV end-diastolic diameter, LV end-systolic diameter, and left atrium diameter at baseline and at 9 months were all higher in patients with as compared to those without 9-month moderate-severe MR. Patients with 9-month moderate-severe MR had lower baseline eGFR and higher baseline and 9-month plasma NT-proBNP levels compared to patients with no or mild MR. All QoL measures assessed at 9 months were lower in these patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Echocardiographic data, laboratory data, and QoL measures in patients with vs. without 9-month moderate-severe MR

| Overall (n = 1022) |

Moderate or severe MR (n = 360) |

No or mild MR (n = 622) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echocardiographic data | ||||

| LVEF (%) | ||||

| Baseline | 30 (25–35) | 30 (25–35) | 30 (25–35) | 0.060 |

| 9 months | 35 (28–42) | 30 (25–38) | 36 (30–45) | < 0.001 |

| LVEF categories | ||||

| Baseline | 0.409 | |||

| HFrEF (LVEF < 40%) | 810 (85.1) | 298 (86.9) | 512 (84.1) | |

| HFmrEF (LVEF 40–49%) | 102 (10.7) | 34 (9.9) | 68 (11.2) | |

| HFpEF (LVEF ≥ 50%) | 40 (4.2) | 11 (3.2) | 29 (4.8) | |

| 9 months | < 0.001 | |||

| HFrEF (LVEF < 40%) | 611 (64.2) | 269 (78.0) | 342 (56.3) | |

| HFmrEF (LVEF 40–49%) | 227 (23.8) | 60 (17.4) | 167 (27.5) | |

| HFpEF (LVEF ≥ 50%) | 114 (12.0) | 16 (4.6) | 98 (16.1) | |

| LVEDD (mm) | ||||

| Baseline | 62 (57–68) | 64 (58–70) | 61 (56–66) | < 0.001 |

| 9 months | 61 (55–67) | 64 (58–70) | 60 (54–65) | < 0.001 |

| LVESD (mm) | ||||

| Baseline | 50 (44–56) | 52 (46–59) | 49 (43–55) | < 0.001 |

| 9 months | 48 (40–56) | 52 (45–60) | 46 (39–52) | < 0.001 |

| Left atrium diameter (mm) | ||||

| Baseline | 47 (42–52) | 49 (44–54) | 46 (41–50) | < 0.001 |

| 9 months | 46 (41–51) | 48 (44–53) | 44 (40–50) | < 0.001 |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | ||||

| Baseline | 99 (81–124) | 102 (83–127) | 97 (80–123) | 0.172 |

| 9 months | 104 (84–131) | 103 (86–135) | 105 (83–130) | 0.552 |

| eGFR CKD-EPI (mL/min/1.73 m2) | ||||

| Baseline | 64 (47–81) | 61 (44–79) | 65 (49–83) | 0.014 |

| 9 months | 60 (43–78) | 60 (43–75) | 60 (44–80) | 0.214 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | ||||

| Baseline | 10.1 (7.1–16.1) | 10.7 (7.4–17.1) | 9.8 (7.0–15.6) | 0.077 |

| 9 months | 10.1 (7.0–16.1) | 10.1 (7.2–17.9) | 10.1 (6.8–15.4) | 0.200 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | ||||

| Baseline | 140 (137–142) | 140 (138–142) | 140 (137–142) | 0.625 |

| 9 months | 140 (137–142) | 139 (137–142) | 140 (138–142) | 0.578 |

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | ||||

| Baseline | 2056 (943–4785) | 2659 (1206–5175) | 1877 (859–4548) | < 0.001 |

| 9 months | 1098 (371–2410) | 1645 (765–3350) | 781 (282–1889) | < 0.001 |

| QoL measures | ||||

| 6MWT distance (m) | ||||

| Baseline | 282 (65–385) | 268 (100–361) | 294 (48–391) | 0.240 |

| 9 months | 350 (220–450) | 314 (200–418) | 360 (234–463) | < 0.001 |

| KCCQ clinical summary score | ||||

| Baseline | 54 (35–73) | 51 (33–70) | 56 (35–74) | 0.123 |

| 9 months | 70 (50–87) | 63 (46–82) | 73 (54–89) | < 0.001 |

| KCCQ overall summary score | ||||

| Baseline | 54 (36–72) | 52 (36–70) | 55 (38–73) | 0.118 |

| 9 months | 70 (51–85) | 63 (47–80) | 72 (55–88) | < 0.001 |

| EQ-5D index value | ||||

| Baseline | 0.74 (0.57–0.84) | 0.74 (0.57–0.84) | 0.74 (0.64–0.84) | 0.597 |

| 9 months | 0.78 (0.65–0.90) | 0.77 (0.65–0.86) | 0.81 (0.68–0.90) | < 0.001 |

| EQ-5D VAS | ||||

| Baseline | 60 (45–70) | 51 (40–70) | 60 (45–70) | 0.014 |

| 9 months | 65 (50–80) | 60 (49–75) | 70 (50–80) | < 0.001 |

Data are presented as n (%) and median (Q25–Q75). Bold values represent significant p-values (p < 0.05)

6MWT 6 min walking test; CKD-EPI chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration; eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate; EQ-5D EuroQol-5 dimension; HFmrEF heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction; HFpEF heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; KCCQ Kansas city cardiomyopathy questionnaire; LVEDD left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD left ventricular end-systolic diameter; MR mitral regurgitation; NT-proBNP N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; QoL quality-of-life; VAS visual analogue scale

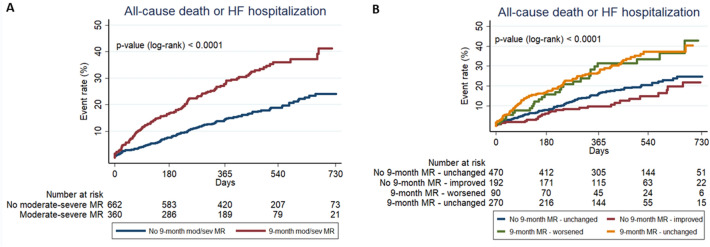

Impact of changes in MR severity and 9-month moderate-severe MR on clinical outcomes

After a median follow-up of 405 (IQR 254–554) days, the primary endpoint occurred in 114 patients (31.7%) with, and in 119 patients (18.0%) without, moderate-severe MR at 9 months (unadjusted HR 2.03, 95% CI 1.57–2.63). By Kaplan–Meier analysis, the incidence of the 2-year primary endpoint was higher in patients with, as compared to those without, moderate-severe MR at 9 months (log-rank p < 0.0001; Fig. 1A). Patients with worsened MR from baseline to 9 months and those with persistent moderate-severe MR at both baseline and 9 months had a similar incidence of the 2-year primary endpoint, which was higher compared to patients whose MR improved from baseline to 9 months and to those who had no or mild MR at both time-points (log-rank p < 0.0001; Fig. 1B). Hence, both patients with worsening MR and those with persistent moderate-severe MR at 9 months, after attempted GRMT, had a greater risk of the primary endpoint (unadjusted HR for worsening MR 1.78, 95% CI 1.17–2.72; unadjusted HR for persistent significant MR 1.91, 95% CI 1.42–2.57). Kaplan–Meier curves for all 2 year individual secondary endpoints are shown in Supplementary Figs. 2, 3, and 4. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 5, the higher risk of the primary endpoint in patients with 9-month moderate-severe MR was observed both in patients with LVEF < 40% and in those with LVEF ≥ 40% (p value for interaction = 0.803).

Fig. 1.

Primary endpoint. The figure shows Kaplan–Meier curves for 2-year primary endpoint (all-cause mortality or HF hospitalization) in patients with vs. without 9-month moderate-severe MR (panel A) and in four patients’ groups according to baseline and 9-month moderate-severe MR after GRMT optimization (panel B). GRMT guideline-directed medical therapy; HF heart failure; MR mitral regurgitation

As shown in Table 3, 9-month moderate-severe MR was significantly associated with an increased risk of the primary endpoint, all-cause death, CV death, and HF hospitalization. The significant impact of 9 month moderate-severe MR on the primary endpoint was confirmed after multivariable adjustment for different models including age and sex (adjusted HR 1.83; 95% CI 1.42–2.38; p < 0.001); primary ischemic HF aetiology, baseline NYHA class, and previous HF hospitalization in last year (adjusted HR 1.62; 95% CI 1.24–2.11; p < 0.001); baseline LVEF categories, baseline eGFR, ACEi/ARB and β-blocker optimal dose fractions achieved at 3 months (adjusted HR 1.91; 95% CI 1.44–2.52; p < 0.001); 9 month LVEF categories, 9 month eGFR, ACEi/ARB and β-blocker optimal dose fractions achieved at 3 months (adjusted HR 1.68; 95% CI 1.23–2.29; p = 0.001); and the previously validated BIOSTAT-CHF risk prediction models (adjusted HR 1.85; 95% CI 1.43–2.39; p < 0.001). Similarly, the significant association between 9-month moderate–severe MR and all secondary endpoints was confirmed after adjustment for the same models.

Table 3.

Cox regression models for the impact of 9-month moderate-severe MR on the combined endpoint (all-cause death or HF hospitalization), all-cause death, CV death and HF hospitalization

| Combined endpoint | All-cause death | CV death | HF hospitalization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Univariable analysis | 2.03 (1.57–2.63) | < 0.001 | 1.83 (1.31–2.55) | < 0.001 | 1.86 (1.25–2.76) | 0.002 | 2.09 (1.51–2.89) | < 0.001 |

| Multivariable model 1 (adjusted for age and sex) | 1.83 (1.42–2.38) | < 0.001 | 1.65 (1.18–2.30) | 0.003 | 1.67 (1.12–2.48) | 0.012 | 1.89 (1.36–2.62) | < 0.001 |

| Multivariable model 2 (adjusted for primary ischemic HF aetiology, baseline NYHA class, and previous HF hospitalization in last year) | 1.62 (1.24–2.11) | < 0.001 | 1.71 (1.22–2.39) | 0.002 | 1.71 (1.15–2.55) | 0.009 | 1.90 (1.37–2.65) | < 0.001 |

| Multivariable model 3 (adjusted for baseline LVEF categories, baseline eGFR, ACEi/ARB optimal dose fraction at 3 months, and β-blocker optimal dose fraction at 3 months) | 1.91 (1.44–2.52) | < 0.001 | 1.83 (1.27–2.64) | 0.001 | 1.96 (1.27–3.03) | 0.002 | 2.00 (1.41–2.84) | < 0.001 |

| Multivariable model 4 (adjusted for LVEF categories at 9 months, eGFR at 9 months, ACEi/ARB optimal dose fraction at 3 months, and β-blocker optimal dose fraction at 3 months) | 1.68 (1.23–2.29) | 0.001 | 1.66 (1.11–2.47) | 0.013 | 1.85 (1.15–2.99) | 0.011 | 1.61 (1.09–2.39) | 0.017 |

| Multivariable model 5 (adjusted for BIOSTAT-CHF risk prediction models)* | 1.85 (1.43–2.39) | < 0.001 | 1.74 (1.25–2.43) | 0.001 | 1.76 (1.19–2.61) | 0.005 | 1.85 (1.34–2.57) | < 0.001 |

Data are presented as HR and 95% CI. Bold values represent significant p-values (p < 0.05)

ACEi angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB angiotensin receptor blocker; CI confidence interval; CV cardiovascular; eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF heart failure; HR hazard ratio; MR mitral regurgitation; LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA New York Heart Association; NT-proBNP N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide

*In multivariable model 5, 9-month moderate-to-severe MR was adjusted for the BIOSTAT-CHF risk prediction models, including the following covariates: age, HF hospitalization in last year, systolic blood pressure, peripheral oedema, log-NT-proBNP, haemoglobin, sodium, high-density lipoprotein, and use of β-blockers at baseline for the combined endpoint; age, log-urea, log-NT-proBNP, haemoglobin, and use of β-blockers at baseline for all-cause death and CV death; age, HF hospitalization in last year, systolic blood pressure, peripheral oedema, and estimated glomerular filtration rate for HF hospitalization

Predictors of 9-month significant MR

At multivariable binary logistic regression analysis (Table 4), the presence of moderate-severe MR at baseline and older age were associated with an increased risk of 9 month moderate-severe MR, whereas HFpEF (LVEF ≥ 50% at baseline) and treatment with a higher fraction of ACEi/ARB optimal dose at 3 months were associated with a lower risk of 9 month moderate-severe MR. The C statistic (0.77) and Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test p value (0.48) confirmed good discrimination and fit of the multivariable model.

Table 4.

Binary logistic regression analysis for the predictors of 9-month moderate-severe MR

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age (years) | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | < 0.001 | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | < 0.001 |

| Sex (women) | 1.10 (0.81–1.48) | 0.548 | 1.08 (0.72–1.60) | 0.713 |

| Primary ischemic HF aetiology | 1.24 (0.96–1.61) | 0.106 | 1.35 (0.96–1.89) | 0.085 |

| Previous HF hospitalization in last year | 1.29 (0.97–1.71) | 0.081 | 1.18 (0.83–1.70) | 0.357 |

| NYHA class III or IV | 1.19 (0.92–1.55 | 0.181 | 1.00 (0.72–1.40) | 0.994 |

| Baseline moderate-severe MR | 7.34 (5.49–9.83) | < 0.001 | 6.96 (4.96–9.78) | < 0.001 |

| eGFR CKD-EPI (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.017 | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 0.273 |

| Log-NT-proBNP (ng/L) | 1.26 (1.12–1.40) | < 0.001 | 1.10 (0.94–1.27) | 0.263 |

| LVEF categories | ||||

| HFrEF (LVEF < 40%)—reference | – | – | – | – |

| HFmrEF (LVEF 40–49%) | 0.86 (0.56–1.33) | 0.494 | 0.82 (0.47–1.43) | 0.491 |

| HFpEF (LVEF ≥ 50%) | 0.65 (0.32–1.32) | 0.236 | 0.36 (0.16–0.85) | 0.019 |

| ACEi/ARB optimal dose fraction at 3 months (%) | 0.59 (0.43–0.83) | 0.002 | 0.60 (0.39–0.93) | 0.021 |

| β-Blocker optimal dose fraction at 3 months (%) | 0.97 (0.63–1.49) | 0.881 | 0.98 (0.57–1.70) | 0.950 |

Data are presented as OR and 95% CI. Bold values represent significant p-values (p < 0.05). The C statistic for the multivariable model is 0.77, the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test p value is 0.48

ACEi angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB angiotensin receptor blocker; CI confidence interval; CKD-EPI chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration; eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF heart failure; HFmrEF heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction; HFpEF heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction; MR mitral regurgitation; NYHA New York Heart Association; NT-proBNP N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; OR odds ratio

Regarding the prediction of changes in MR severity, among the 462 patients with moderate-severe MR at baseline, younger age, HFpEF, and treatment with a higher fraction of ACEi/ARB optimal dose at 3 months were associated with a lower likelihood of persistence of moderate-severe MR at 9 months (Supplementary Table 4). Among the 560 patients with no or mild MR at baseline, older age was the only independent predictor of worsening MR at 9 months (Supplementary Table 5).

Discussion

The main findings of our study on patients with worsening or new-onset HF are as follows: (1) MR may dynamically change after attempted implementation of GRMT, with an improvement observed in a consistent proportion of patients with moderate-severe MR at baseline (41.6%), and MR development or worsening observed in a lower proportion of patients with no or mild MR at baseline (16.1%); (2) moderate-severe MR persists or develops despite GRMT in a substantial proportion of patients (35.2%) and has a strong prognostic impact even after adjusting for several other variables related to HF severity; (3) older age and presence of significant MR at baseline were associated with a greater risk of moderate-severe MR after GRMT optimization, whereas HFpEF and treatment with higher doses of ACEi/ARB were associated with a lower likelihood of moderate-severe MR after GRMT.

In our study, prevalence of 9 month moderate-severe MR after GRMT optimization in patients with HF was 35.2%, a figure that seems in line with prior studies not strictly focusing on GRMT optimization and reporting rates of moderate-severe MR ranging from 29 to 53% [1–3, 10, 13, 15, 16]. Furthermore, we found that MR severity was unchanged after GRMT optimization in 46.0% of patients without moderate-severe MR and in 26.4% of patients with moderate-severe MR, whereas MR improved in 18.8% and worsened in 8.8% of patients from baseline to 9 months. These results are in line with previous smaller studies reporting the evolution of MR in HFrEF patients receiving GRMT [37–40]. Compared to these studies [37–40], our analysis was performed on a much larger study group, including a broader HF population with HFrEF, HFmrEF and HFpEF patients. Despite the percentages of patients with improving or worsening MR were slightly lower in our study (18.8% and 8.8%, respectively) as compared to those reported by Nasser et al. (38% and 18%, respectively), both studies confirmed the prognostic impact of both persistent significant or worsening MR after GRMT optimization [38]. Of note, the Pharmacological Reduction of Functional, Ischemic Mitral Regurgitation (PRIME) trial randomized 118 patients with HF, LVEF < 50%, significant functional MR and optimized medical therapy with ACEi/ARBs or β-blockers to ARNI or valsartan, demonstrating a greater reduction in MR severity with ARNI at 1-year follow-up [28]. Although the benefits of ARNI could exceed those associated with ACEi/ARBs or β-blockers in terms of functional MR reduction, our study was performed before the introduction of ARNI into the routine clinical management of HF patients and, therefore, we could not evaluate the impact of this therapy. Several reasons could explain a lack of MR improvement or even MR worsening in a relevant proportion of patients (35.2%) in our study, including a more advanced stage of HF in terms of symptoms, clinical profile and echocardiographic findings, and lower odds of achieving higher GRMT doses during the optimization phase (see Supplementary Tables 1–2 for details). Biological variables, such as kidney dysfunction, hyperkalemia and low blood pressure may, on the other hand, cause lack of GRMT initiation or up-titration [41–43].

Our study demonstrates that both persistent significant MR and worsening MR after GRMT optimization in patients with HF are associated with an increased risk of all-cause death or HF hospitalization. The prognostic impact of moderate-severe MR after GRMT was particularly strong (univariable HR 2.03, 95% CI 1.57–2.63) and was confirmed after adjustment for several clinical, laboratory and echocardiographic variables, including the already validated BIOSTAT-CHF risk prediction model (adjusted HR 1.85, 95% CI 1.43–2.39) [33]. Our findings are in line with previous smaller studies showing the prognostic impact of persistent significant MR or worsening MR despite GRMT in HFrEF [38, 39]. Furthermore, a recent sub-analysis of the COAPT trial reported that MR improvement at 30 days was associated with better clinical outcomes and improved quality of life among HF patients, regardless of whether such improvement was achieved through transcatheter mitral valve repair or GRMT [44].

Since GRMT represents the first crucial therapeutic step in patients with HF and significant MR, [20, 21] our study may have clinically relevant implications in the management of patients with MR. Our data suggest that the optimal timing to evaluate interventional procedures for MR correction in HF should be after an adequate period of GRMT optimization since the prognostic impact of persistent significant MR after such period is particularly strong. In line with this concept, the COAPT trial demonstrated the prognostic benefit of percutaneous mitral valve repair in a carefully selected population of symptomatic patients with HF and persistent MR despite GRMT up-titration to maximally tolerated doses, as evaluated by a dedicated central committee [19, 24, 25]. Our study seems in line with this strategy of GRMT optimization before planning potential interventions for MR correction in HF.

Interestingly, ACEi/ARB up-titration was associated with a lower likelihood of persistence of moderate-severe MR in our study and, therefore, with MR improvement after the optimization phase. Prior randomized studies have already demonstrated that ACEi are effective in reducing functional MR in HFrEF [29]. Similarly, as already mentioned, sacubitril/valsartan was more effective than valsartan in reducing functional MR among 118 patients with HFrEF or HFmrEF enrolled in the PRIME trial [28]. Furthermore, among patients undergoing percutaneous mitral valve repair for secondary MR, in addition to a “COAPT-like” echocardiographic and clinical profile, GRMT was found to be a powerful predictor of 5 year survival [45]. Several mechanisms could explain the benefit of RAAS inhibitors on MR in HF, including reverse LV remodelling, afterload reduction and beneficial effects on valve leaflet remodelling [46, 47]. However, from the present study, we cannot assess whether the association between better up-titration of ACEi/ARB and a lower likelihood of persistence of moderate-severe MR was causally related.

Furthermore, we found that HFpEF was associated with a lower likelihood of moderate-severe MR after the optimization phase of GRMT up-titration. The different mechanisms and pathogenesis of MR in patients with normal or reduced LVEF could play a role in the different MR evolution in patients with HFrEF and HFpEF after GRMT optimization [48, 49]. Of note, atrial functional MR, typically associated with HFpEF and atrial fibrillation, has emerged as a distinct entity from “ventricular” secondary MR, typically associated with HFrEF [50]. Despite the better prognosis of patients with HFpEF as compared to those with HFrEF [51], significant functional MR has been associated with worse clinical outcomes both in HFpEF and in HFrEF patients [12]. However, the interplay between ACEi/ARB or β-blockers up-titration and persistence of significant MR in HFpEF needs to be further explored in dedicated studies.

Limitations

Our study is a post hoc retrospective analysis of a prospective multicentre registry and, therefore, has all the usual limitations associated with this design. The main limitation is the lack of core-laboratory analysis of echocardiographic data and the consequent lack of detailed information regarding MR severity and aetiology. Furthermore, no independent adjudication of clinical events was performed. Of note, BIOSTAT-CHF was performed before the introduction of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and ARNI in the treatment of HFrEF, hence the impact of these therapies on MR evolution and prognosis could not be evaluated. Moreover, the proportion of patients with HFpEF in our study was relatively small (4.2%), thus preventing from definitive conclusions for this disease entity, and no specific recommendations regarding GRMT were available for HFpEF at time of BIOSTAT-CHF enrolment [35].

Conclusions

In patients with worsening or new-onset HF enrolled in BIOSTAT-CHF, MR severity may dynamically change after a dedicated period of GRMT optimization. The presence of moderate-severe MR after GRMT optimization, either persistent moderate-severe or worsening MR from baseline, has a strong prognostic impact, regardless of relevant variables of interest and from an already validated risk prediction model. Higher ACEi/ARB up-titration and HFpEF were associated with a higher likelihood of MR improvement after GRMT optimization.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Brescia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. The BIOSTAT-CHF project was funded by a grant from the European Commission (FP7-242209-BIOSTAT-CHF; EudraCT 2010-020808-29).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Filippatos reports speaker honoraria and/or committee membership in trials and/or registries sponsored by Amgen, Bayer, Novartis, Boehringer Ingrelheim, Medtronic, Vifor, and Servier; and research grants from the European Union. Dr. Voors received consultancy fees and/or research grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, Merck, Myokardia, Novartis, Novonordisk, and Roche Diagnostics. Dr. Metra received personal consulting honoraria from Abbott, Actelion, Amgen, Bayer, Edwards Therapeutics, Servier, Vifor Pharma, and Windtree Therapeutics for participation to advisory board meetings and executive committees of clinical trials. All the other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Chioncel O, Lainscak M, Seferovic PM, et al. Epidemiology and one-year outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved, mid-range and reduced ejection fraction: an analysis of the ESC heart failure long-term registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:1574–1585. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chioncel O, Mebazaa A, Harjola V-P, et al. Clinical phenotypes and outcome of patients hospitalized for acute heart failure: the ESC heart failure long-term registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:1242–1254. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleland JGF, Swedberg K, Follath F, et al. The EuroHeart failure survey programme—a survey on the quality of care among patients with heart failure in Europe. Part 1: patient characteristics and diagnosis. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:442–463. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00823-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grigioni F, Enriquez-Sarano M, Zehr KJ, et al. Ischemic mitral regurgitation: long-term outcome and prognostic implications with quantitative Doppler assessment. Circulation. 2001;103:1759–1764. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.13.1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amigoni M, Meris A, Thune JJ, et al. Mitral regurgitation in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both: prognostic significance and relation to ventricular size and function. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:326–333. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trichon BH, Felker GM, Shaw LK, et al. Relation of frequency and severity of mitral regurgitation to survival among patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:538–543. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De la Espriella R, Santas E, Miñana G, et al. Functional mitral regurgitation predicts short-term adverse events in patients with acute heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120:1344–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kajimoto K, Minami Y, Otsubo S, et al. Ischemic or nonischemic functional mitral regurgitation and outcomes in patients with acute decompensated heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120:809–816. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kubo S, Kawase Y, Hata R, et al. Dynamic severe mitral regurgitation on hospital arrival as prognostic predictor in patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2018;273:177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.09.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arora S, Sivaraj K, Hendrickson M, et al. Prevalence and prognostic significance of mitral regurgitation in acute decompensated heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2021;9:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wada Y, Ohara T, Funada A, et al. Prognostic impact of functional mitral regurgitation in patients admitted with acute decompensated heart failure. Circ J. 2016;80:139–147. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kajimoto K, Sato N, Takano T. Functional mitral regurgitation at discharge and outcomes in patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure with a preserved or reduced ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:1051–1059. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pagnesi M, Adamo M, Sama IE, et al. Impact of mitral regurgitation in patients with worsening heart failure: insights from BIOSTAT-CHF. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23:1750–1758. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossi A, Dini FL, Faggiano P, et al. Independent prognostic value of functional mitral regurgitation in patients with heart failure. A quantitative analysis of 1256 patients with ischaemic and non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2011;97:1675–1680. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2011.225789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bursi F, Barbieri A, Grigioni F, et al. Prognostic implications of functional mitral regurgitation according to the severity of the underlying chronic heart failure: a long-term outcome study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:382–388. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goliasch G, Bartko PE, Pavo N, et al. Refining the prognostic impact of functional mitral regurgitation in chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:39–46. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pecini R, Thune JJ, Torp-Pedersen C, et al. The relationship between mitral regurgitation and ejection fraction as predictors for the prognosis of patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:1121–1125. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coats AJS, Anker SD, Baumbach A, et al. The management of secondary mitral regurgitation in patients with heart failure: a joint position statement from the Heart Failure Association (HFA), European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI), European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), and European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:1254–1269. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Senni M, Adamo M, Metra M, et al. Treatment of functional mitral regurgitation in chronic heart failure: can we get a ‘proof of concept’ from the MITRA-FR and COAPT trials? Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:852–861. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2017;136:e137–e161. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2129–2200. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metra M, Teerlink JR. Heart failure. Lancet. 2017;390:1981–1995. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:3599–3726. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stone GW, Lindenfeld J, Abraham WT, et al. Transcatheter mitral-valve repair in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2307–2318. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonow RO, Mark DB, O’Gara PT. Coapting cost and clinical Outcomes in transcatheter intervention for secondary mitral regurgitation. Circulation. 2019;140:1892–1894. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.043408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Capomolla S, Febo O, Gnemmi M, et al. Beta-blockade therapy in chronic heart failure: diastolic function and mitral regurgitation improvement by carvedilol. Am Heart J. 2000;139:596–608. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(00)90036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lowes BD, Gill EA, Abraham WT, et al. Effects of carvedilol on left ventricular mass, chamber geometry, and mitral regurgitation in chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:1201–1205. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(99)00059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang D-H, Park S-J, Shin S-H, et al. Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor for functional mitral regurgitation. Circulation. 2019;139:1354–1365. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seneviratne B, Moore GA, West PD. Effect of captopril on functional mitral regurgitation in dilated heart failure: a randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. Heart. 1994;72:63–68. doi: 10.1136/hrt.72.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levine AB, Muller C, Levine TB. Effects of high-dose lisinopril-isosorbide dinitrate on severe mitral regurgitation and heart failure remodeling. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:1299–1301. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00623-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spartera M, Galderisi M, Mele D, et al. Role of cardiac dyssynchrony and resynchronization therapy in functional mitral regurgitation. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17:471–480. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jev352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Voors AA, Anker SD, Cleland JG, et al. A systems biology study to tailored treatment in chronic heart failure: rationale, design, and baseline characteristics of BIOSTAT-CHF. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:716–726. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voors AA, Ouwerkerk W, Zannad F, et al. Development and validation of multivariable models to predict mortality and hospitalization in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:627–634. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ouwerkerk W, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. Determinants and clinical outcome of uptitration of ACE-inhibitors and beta-blockers in patients with heart failure: a prospective European study. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:1883–1890. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dickstein K, Cohen-Solal A, Filippatos G, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2388–2442. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lancellotti P, Tribouilloy C, Hagendorff A, et al. Recommendations for the echocardiographic assessment of native valvular regurgitation: an executive summary from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14:611–644. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jet105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Groot de Laat LE, Huizer J, Lenzen M, et al. Evolution of mitral regurgitation in patients with heart failure referred to a tertiary heart failure clinic. ESC Heart Fail. 2019;6:936–943. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nasser R, Van Assche L, Vorlat A, et al. Evolution of functional mitral regurgitation and prognosis in medically managed heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5:652–659. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2017.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bartko PE, Pavo N, Pérez-Serradilla A, et al. Evolution of secondary mitral regurgitation. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19:622–629. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jey023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sannino A, Sudhakaran S, Milligan G, et al. Effectiveness of medical therapy for functional mitral regurgitation in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:883–884. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ameri P, Bertero E, Maack C, et al. Medical treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the dawn of a new era of personalized treatment? Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2021;7:539–546. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvab033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jarjour M, Henri C, de Denus S, et al. Care gaps in adherence to heart failure guidelines. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8:725–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cautela J, Tartiere J-M, Cohen-Solal A, et al. Management of low blood pressure in ambulatory heart failure with reduced ejection fraction patients. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22:1357–1365. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kar S, Mack MJ, Lindenfeld J, et al. Relationship between residual mitral regurgitation and clinical and quality-of-life outcomes after transcatheter and medical treatments in heart failure. Circulation. 2021;144:426–437. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.053061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adamo M, Fiorelli F, Melica B, et al. COAPT-like profile predicts long-term outcomes in patients with secondary mitral regurgitation undergoing mitraclip implantation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bartko PE, Dal-Bianco JP, Guerrero JL, et al. Effect of losartan on mitral valve changes after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1232–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.07.734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beaudoin J, Dal-Bianco JP, Aikawa E, et al. Mitral leaflet changes following myocardial infarction: clinical evidence for maladaptive valvular remodeling. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10:e006512. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.117.006512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamargo M, Obokata M, Reddy YNV, et al. Functional mitral regurgitation and left atrial myopathy in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22:489–498. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guazzi M, Ghio S, Adir Y. Pulmonary Hypertension in HFpEF and HFrEF. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:1102–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deferm S, Bertrand PB, Verbrugge FH, et al. Atrial functional mitral regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2465–2476. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meta-analysis Global Group in Chronic Heart Failure (MAGGIC) The survival of patients with heart failure with preserved or reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1750–1757. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.