Abstract

Background

Chlormethine gel was approved for treatment of mycosis fungoides, the most common cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, on the basis of results from study 201 and study 202. A post-hoc analysis of study 201 found interesting trends regarding improved efficacy of chlormethine gel vs ointment and noted a potential association between dermatitis and clinical response.

Objective

To expand these results by performing a post-hoc analysis of study 202.

Patients and Methods

Patients received chlormethine gel or ointment during study 201 (12 months) and higher-concentration chlormethine gel during study 202 (7-month extension). Response was assessed using Composite Assessment of Index Lesion Severity (CAILS). Associations between treatment frequency, response, and skin-related adverse events (AEs) were assessed using multivariate time-to-event analyses. Time-to-response and repeated measures analyses were compared between patients who only used chlormethine gel and those who switched from ointment to gel.

Results

No associations were seen between treatment frequency and improved skin response (CAILS) or AE occurrence within the 201/202 study populations. However, an association was observed specifically between contact dermatitis and improved CAILS response at the next visit (p < 0.0001). Patients who used chlormethine gel during both studies had a significantly (p < 0.05) shorter time to response and higher overall response rates than patients who initiated treatment with ointment.

Conclusions

This post-hoc analysis shows that patients who initiated treatment using chlormethine gel had faster and higher responses compared with patients who initially used chlormethine ointment for 12 months. The development of contact dermatitis may be a potential prognostic factor for response.

Trial Registration Numbers and Dates of Registration

Study 201: NCT00168064, September 14, 2002; Study 202: NCT00535470, September 26, 2007.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40257-022-00687-y.

Key Points

| This post-hoc analysis showed that patients with mycosis fungoides who initiated treatment with chlormethine gel had faster and higher clinical response rates compared with patients who had first used chlormethine ointment for 12 months |

| An association was seen between contact dermatitis and an improved skin response at the next clinical visit, indicating that development of dermatitis may potentially be a prognostic factor for response |

Introduction

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas are a rare subset of non-Hodgkin lymphomas, with mycosis fungoides (MF) being the most common subtype [1]. Patients with MF usually present with patches and plaques on the skin and may develop tumors or blood and organ involvement in later stages of disease [2]. Treatment for MF is generally based on disease stage, and aimed at reducing disease and associated symptoms, preventing disease progression, and improving quality of life. Patients with early stage disease (IA–IIA) tend to be treated with skin-directed therapies such as topical corticosteroids, phototherapy, radiotherapy, or topical chlormethine (also known as mechlorethamine), as recommended by national and international treatment guidelines [1, 3–5].

Topical chlormethine has been used as a treatment for patients with MF since the 1950s [6]. The early topical formulations of chlormethine were aqueous and ointment-based, although neither were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of MF. More recently, a chlormethine gel formulation was specifically developed for MF to ease the preparation and application of treatment. This chlormethine 0.016% w/w topical gel formulation (equivalent to 0.02% chlormethine HCl) is currently approved for the treatment of patients with MF in several countries worldwide, including the US and the EU [7–9].

Chlormethine is a bifunctional alkylating agent that inhibits rapidly proliferating cells. Current evidence suggests that chlormethine renders malignant MF skin T cells more prone to apoptosis by inducing double-stranded DNA breaks, upregulating the pro-apoptotic gene CASP3, and suppressing the expression of genes involved in homologous recombination repair [10]. These data all indicate an important effect of targeting MF skin tumor cells and provide a rationale for chlormethine as an early and valuable skin-directed treatment option for cutaneous lymphoma. There is no evidence of systemic absorption for the gel or ointment formulations of chlormethine, which bypasses the need to monitor blood samples during treatment. Furthermore, the lack of systemic absorption also indicates that systemic drug-drug interactions are unlikely to occur with concomitant therapy [11].

The approval of chlormethine gel was based on the results of the pivotal 201 trial (NCT00168064) and its extension study (study 202; NCT00535470). In the 12-month, phase 2/3 study 201, chlormethine gel was compared with equal-strength compounded ointment and its efficacy was deemed noninferior. Response was assessed using the Composite Assessment of Index Lesion Severity (CAILS) and modified Severity-Weighted Assessment Tool (mSWAT) [12, 13]. A subsequent post-hoc analysis of the 201 data found that treatment with chlormethine gel resulted in higher and faster response rates compared with chlormethine ointment [14]. During study 202, patients who had not achieved a complete response (CR) during study 201 (with either chlormethine gel or ointment) were treated with a higher concentration of chlormethine gel (0.032% w/w, equivalent to 0.04% chlormethine HCl) and monitored for an additional 7 months [15]. Of note, compounded topical chlormethine treatment was previously often initiated at a concentration of 0.01–0.02% and then increased to 0.03–0.04% to maximize the chance of a response [16, 17]. The results of study 202 showed that continued treatment with a higher concentration of chlormethine gel led to additional clinical benefit for patients, especially for recalcitrant lesions [15].

Adverse events (AEs) observed after chlormethine gel initiation are generally mild and skin-related, including skin irritation, pruritus, erythema, and contact dermatitis [12, 18, 19]. Treatment with a higher concentration of chlormethine gel in study 202 did not increase the frequency of AEs compared with 0.02% gel [15].

Interesting signals were observed in the post-hoc analysis of study 201, indicating there was a potential association between the development of contact dermatitis and clinical response. In addition, chlormethine gel treatment was more effective over time than chlormethine ointment [14]. The current post-hoc analysis of data from study 202 aimed to further investigate the associations between skin-related AEs, clinical response, and treatment frequency. In addition, the analysis assessed whether continued treatment with chlormethine gel is more beneficial for patients with MF than switching from ointment to gel.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

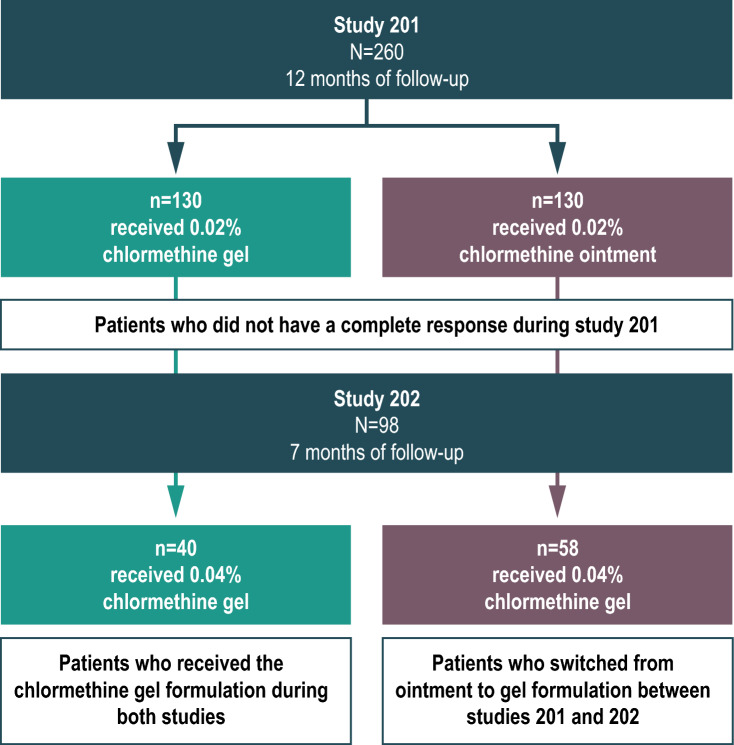

This post-hoc analysis included data from both study 201 and study 202 (Fig. 1). Study 201 was a multicenter, randomized, controlled, observer-blinded study of previously treated patients with stage IA–IB or IIA MF; a detailed description of the study design has been published [12]. During this study, a total of 260 patients were enrolled and randomized to receive either 0.02% chlormethine gel or ointment. Treatment was applied once daily to specific lesions or the total skin surface for up to 12 months. The primary clinical endpoint was the CAILS response rate, which was assessed monthly between months 1–6 and every 2 months between months 7–12.

Fig. 1.

Patient flow during study 201 and study 202

Study 202 was an open-label extension study that included patients who had completed 12 months of treatment with 0.02% chlormethine gel or ointment during study 201 without achieving CR [15]. The month 12 CAILS assessments from study 201 served as baseline assessments for study 202. The same five lesions (without CR) that were evaluated during study 201 were used as index lesions in study 202. Alternative lesions that had been consistently treated during study 201 could be included if fewer than five original index lesions were available. In total, 100 patients were enrolled in study 202, and 98 applied at least one dose of study treatment. Patients received 0.04% chlormethine gel once daily for up to 7 months. CAILS response was assessed during months 2, 4, and 6 with a final assessment at month 7. The patients who had received chlormethine ointment during study 201 were switched to chlormethine gel treatment during study 202. No concomitant treatment for MF was permitted during either study.

During study 201 and 202, CAILS, mSWAT, and body surface area (BSA) response data were collected. This post-hoc analysis mainly considered CAILS response, the primary efficacy outcome in both trials. To determine the CAILS score, five index lesions are scored according to erythema, scaling, plaque elevation, and surface area. In contrast, BSA and mSWAT both include the total skin surface, excluding or including weighting factors for lesion types, respectively [13]. The CAILS scores were chosen as the main outcome for this analysis because these are considered to be more sensitive, particularly for patients with early stage MF. When initiating treatment with chlormethine gel, new lesions may seem to appear; however, these are usually subclinical MF lesions that are unmasked by chlormethine gel [20]. This mainly occurs during the first month of treatment but may affect total skin scores such as mSWAT and BSA.

CR was defined as a CAILS score of 0 (100% skin clearance), very good partial response (VGPR) as a 75 to < 100% reduction from the baseline CAILS score, and partial response (PR) as 50 to < 75% reduction from baseline score.

The study protocols were approved by institutional review boards of the participating centers and complied with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent.

Statistical Methods

Multivariate Time-to-Event Analysis

Associations between potential predictors (covariates) and events of interest that may occur more than once in the same patient, such as the occurrence of skin-related AEs or clinical response, were investigated using multivariate time-to-event analyses. For these analyses, data from patients included in the safety population of the study 201 chlormethine gel arm (n = 128) and from all patients in study 202 were included. Baseline and final visits could not be included in the analysis. The semiparametric proportional means model implemented in the PHREG procedure of SAS software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used to analyze multivariate time-to-event data. By using this statistical method, time-dependent covariates that may change over time for individual patients can be accommodated. Results are reported as hazard ratios with a 95% confidence interval.

Time-to-Response Analysis

Kaplan-Meier curves were used to estimate the time to response, defined as the first occurrence of a CAILS response. Multiple curves were produced on the basis of different definitions of response: CR only, at least VGPR (CR or VGPR), and at least PR (CR, VGRP, or PR). For these analyses, the intent-to-treat (ITT) populations from study 201 and study 202 were used. Separate analyses were done for all patients (from both study 201 and 202) and patients from study 202 only. Patients who were treated with 0.02% chlormethine gel in study 201 and with 0.04% chlormethine gel in study 202 were compared with patients who used 0.02% chlormethine ointment during study 201 and 0.04% chlormethine gel during study 202. This comparison was made with a log-rank test using the LIFETEST procedure of SAS software.

Repeated Measures Analyses

Repeated measures analyses were performed using generalized estimating equation (GEE) models with logit link function and binomial distribution. Model fixed effects that were applied were baseline CAILS scores, type of treatment, visit, and treatment-by-visit interaction. Only data from study 202 were included and, whenever possible, the variance-covariance matrix of the GEE model was parameterized in order to adjust the estimates for the correlation across repeated measures. Treatment arms for comparison were patients treated with chlormethine gel during both study 201 and 202 and patients who switched from chlormethine ointment to 0.04% gel between study 201 and 202. Visit-by-visit comparisons were performed using proper contrasts applied on the treatment-by-visit interaction and used to test the differences between the two treatment arms. Response was defined as CR only, at least VGPR, or at least PR. The GEE procedure of SAS software was used to calculate quasi-maximum likelihood estimates of the model parameters. Results are reported as model-based estimates with standard errors.

Results

Patients

In total, 260 patients with classic MF enrolled in study 201, with 130 patients each randomized to treatment with chlormethine gel or ointment. The ITT population included 129 patients from the chlormethine gel arm and 127 patients from the ointment arm. Of these, 98 patients without a CR were enrolled and treated during study 202; 58 had originally received chlormethine ointment in study 201 and 40 had received 0.02% chlormethine gel. There were no significant differences in compliance rates between treatment groups, with 17 (29%) patients initially assigned to the chlormethine ointment and 17 (43%) to the chlormethine gel groups using treatment daily (p = 0.1776).

Multivariate Time-to-Event Analysis

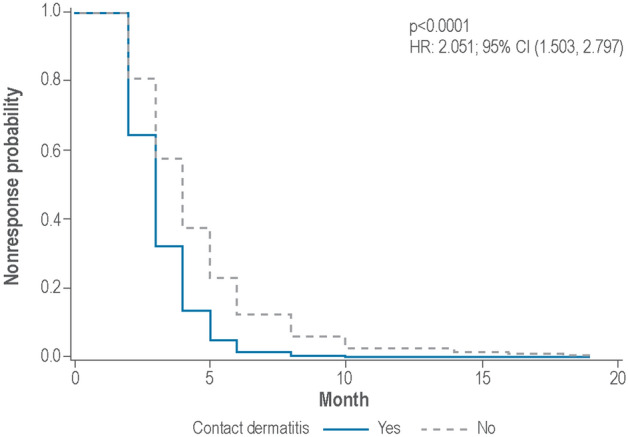

The effect of chlormethine gel application frequency on the occurrence of skin-related AEs at the following visit was assessed by comparing patients who used chlormethine gel daily (n = 34; 17 patients in each group) with those who used it less frequently (2–6 or 1–3 times per week; n = 64, of whom 41 patients initially received chlormethine ointment and 23 chlormethine gel) in response to prior development of skin-related AEs. There were 116 occurrences of skin-related AEs during study 201 and study 202 that could be included in the analysis, including contact dermatitis, pruritus, folliculitis, erythema, skin irritation, and skin hyperpigmentation (Table 1). This analysis did not demonstrate an association between frequency of application and the occurrence of skin-related AEs (p = 0.2478; Supplementary information: Fig. S1). The effect of chlormethine gel application frequency on clinical response at the next visit was also assessed, with no association found between frequency of application and an improved skin response as assessed by CAILS (p = 0.9188; Supplementary information: Fig. S2). Finally, the effect of contact dermatitis on the occurrence of an improved CAILS response was assessed by comparing patients with and without this AE. AEs that were classified per Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities preferred terms as contact dermatitis during study 201 and 202 were included in the analysis. Patch testing for allergic versus irritant contact dermatitis was not mandatory during these two studies. In total, there were 12 cases of contact dermatitis that could be included in the analysis (Table 1). During study 201 there were eight cases of dermatitis among seven patients, and during study 202 there were four cases of dermatitis among three patients. This analysis showed an association between the occurrence of contact dermatitis and clinical response at the next visit (p < 0.0001; Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Adverse events

| Study 201 | Study 202 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlormethine gel arm (n = 128) | Chlormethine ointment arm (n = 127) | Received chlormethine gel during study 201 (n = 40) | Received chlormethine ointment during study 201 (n = 58) | |

| Original analysis | ||||

| Patients with AEs, n (%) | ||||

| Skin irritation | 32 (25.0) | 18 (14.2) | 5 (12.5) | 12 (20.7) |

| Pruritus | 25 (19.5) | 20 (15.7) | 7 (17.5) | 6 (10.3) |

| Erythema | 22 (17.2) | 18 (14.2) | 2 (5.0) | 6 (10.3) |

| Contact dermatitis | 19 (14.8) | 19 (15.0) | 2 (5.0) | 2 (3.4) |

| Skin hyperpigmentation | 7 (5.5) | 9 (7.1) | 1 (2.5) | 3 (5.2) |

| Folliculitis | 7 (5.5) | 5 (3.9) | 1 (2.5) | 3 (5.2) |

| Post-hoc multivariate time-to-event analysis | ||||

| AEs included in analysis, na | 64 | NA | 52 | |

| Skin irritation | 18 | 20 | ||

| Pruritus | 15 | 13 | ||

| Erythema | 15 | 10 | ||

| Contact dermatitisb | 8 | 4 | ||

| Skin hyperpigmentation | 4 | 3 | ||

| Folliculitis | 4 | 2 | ||

| Dermatitis grade, n | 20 | |||

| 1–2 | 6 | NA | 4 | |

| ≥ 3 | 1c | 0 | ||

AE adverse event

aAll separate AEs from individual patients were included in the analysis.

bOne patient in each study had two separate events of contact dermatitis.

cPatient was patch tested, revealing allergic dermatitis, and later withdrew from the study.

Fig. 2.

Association between the occurrence of contact dermatitis and an improved CAILS response at the next visit. For these analyses, data from patients included in the safety population of the study 201 chlormethine gel arm (n = 128) and from all patients in study 202 were included. CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio

Time-to-Response Analysis

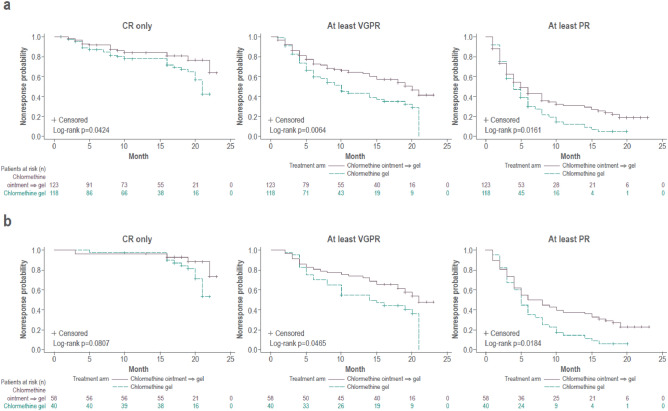

For investigation of the time to first CAILS response, two sets of analyses were done. The first included all patients in the ITT population of study 201 and study 202 and considered all study visits from the initiation of study 201. In these analyses, patients using chlormethine gel since the beginning of study 201 were compared with those who used chlormethine ointment during study 201 and subsequently switched to chlormethine gel during study 202. Patients who had been treated with chlormethine gel throughout both studies, and only changed the concentration of the gel, had a significantly shorter time to response than patients who were initially treated using chlormethine ointment (Fig. 3a). This significant difference was seen when response was defined as CR only (p = 0.0424), at least VGPR (p = 0.0064), or at least PR (p = 0.0161). Intention-to-treat analyses using mSWAT and BSA scores also indicated a significantly shorter time to CR in those patients who had been continuously treated with chlormethine gel compared with those who initially received chlormethine ointment (p = 0.0454 for both mSWAT and BSA), whereas no significant differences were found between the two groups when response was defined as at least VGPR or at least PR. For the second analysis, only those patients enrolled in study 202 were considered (n = 98), although all visits from the initiation of study 201 were included. The patients who used chlormethine gel since the start of study 201 were compared with those who initially used ointment. These analyses also showed a significantly shorter time to response for patients treated with chlormethine gel during both studies (Fig. 3b) when response was defined as at least VGPR (p = 0.0465) or at least PR (p = 0.0184). A similar trend was seen for patients with CR only (p = 0.0807), although this was not significant. Since the absence of CR was a requirement for patients to enroll in study 202, the difference between treatment arms only becomes visible at the start of study 202 for this population. Intention-to-treat analyses using mSWAT score also indicated a significantly shorter time to response for patients treated with chlormethine gel during both studies when response was defined as CR only (p = 0.0515) or at least VGPR (p = 0.0372). For the at least PR category, a similar trend in shorter time to response was seen, although it was not significant (p = 0.5535). Analyses with BSA scores showed a borderline significantly shorter time to response when response was defined as CR only (p = 0.0515), with a similar trend when response was defined as at least VGPR (p = 0.0809) and at least PR (p = 0.6470).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing the time to first Composite Assessment of Index Lesion Severity (CAILS) response for patients treated with chlormethine gel during both study 201 and 202, and patients treated with chlormethine ointment during study 201 and chlormethine gel during study 202, with complete response (CR), at least very good partial response (VGPR), and at least partial response (PR) when including a all patients enrolled in the intent-to-treat population of study 201 and 202 or b including only those patients who were enrolled in study 202

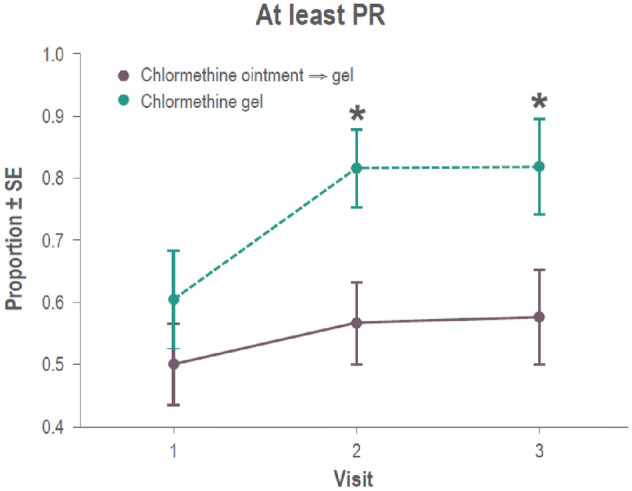

Repeated Measures Analyses

For these analyses, only data from patients enrolled in study 202 were included, and only visits made during the 7-month follow-up of study 202, corresponding to months 14, 16, and 18 from the start of study 201, were considered. Differences in CAILS response were seen between patients who had been using chlormethine gel since the beginning of study 201, and patients who used chlormethine ointment during study 201. Responses were higher for patients who had used chlormethine gel throughout both studies, and this difference was significant when response was defined as at least PR (Fig. 4 and Supplementary information: Fig. S3). mSWAT and BSA responses were also tendentially higher in patients who used the gel formulation throughout the two studies.

Fig. 4.

Repeated measures analysis for patients treated with chlormethine gel during both study 201 and 202 and patients treated with chlormethine ointment during study 201 and chlormethine gel during study 202 with at least partial response (PR). SE standard error

Discussion

The post-hoc analysis described herein shows that continued treatment with chlormethine gel for patients with MF resulted in additional clinical benefit. A subset of patients who did not have a clinical response during the initial 12-month study 201 did experience an improved skin response during extension study 202. This was also the case for patients who did not have a response using chlormethine ointment and switched to the higher-concentration chlormethine gel in study 202. The fact that patients could still achieve clinical responses after more than 12 months of treatment with chlormethine gel indicates that long-term continued treatment may be needed to maximize the chance of response.

Patients treated with 0.02% chlormethine gel during study 201, who continued with 0.04% chlormethine gel during study 202, had faster and better CAILS responses than patients who received chlormethine ointment during study 201 followed by 0.04% chlormethine gel during study 202. The faster time to response with chlormethine gel was observed for all types of response (CR only, at least VGPR, and at least PR). As the mode of action is purported to be the same for chlormethine gel and ointment formulations, the difference in time to response could be due to differences in the composition and/or drug delivery of the two formulations. The gel formulation contains the excipient Klucel™ [21] that ensures appropriate viscosity of the product and makes the gel more likely to remain at the site of administration and at the target area [20]. In-vitro permeation studies have indicated that chlormethine gel remains in the epidermal layer, with minimum levels reaching dermal tissue [22]. In-vitro release testing also demonstrated that chlormethine had a higher mean release rate in the gel formulation (5.70 µg/cm2/√h) compared with ointment (2.38 µg/cm2/√h) (data on file), suggesting that the gel formulation improves drug delivery.

The present analysis confirms and expands on the data regarding associations between the frequency of chlormethine gel application, improved clinical response, and the occurrence of skin-related AEs as previously reported in a post-hoc analysis of study 201 [14]. Herein, an additional 7 months of follow-up was included for patients who enrolled in study 202 and were treated with 0.04% chlormethine gel. In clinical practice, patients often initiate treatment with chlormethine gel at a lower frequency than once daily and increase frequency of application over time, in part to avoid the development of AEs [19, 20, 23]. Nevertheless, our analysis on patients from pivotal studies found no association between the frequency of chlormethine gel application and the occurrence of skin-related AEs, despite once-daily application. This may suggest that the development of skin-related AEs could potentially be associated not only with chlormethine gel dosage, but also with a hypersensitivity reaction (type B). Most type B reactions involve the immune system; for example, certain drugs may bind to immune receptors or drug-receptor interactions may stimulate inflammatory cells [24]. However, the lack of association between treatment application frequency and AEs needs further confirmation, as in our study per trial design, patients had to apply chlormethine on a daily basis unless they developed skin-related AEs requiring a reduction in the application frequency. This requirement makes it more difficult to firmly assess the association between treatment application and AEs in this particular study population, and additional research would be needed to confirm these results.

No association seen between the application frequency of chlormethine gel and an improved skin response per CAILS, suggesting that patients who reduce the frequency of application may have the same chance of achieving a response as patients who apply the gel on a daily basis. This is in line with results from the PROVe study, where despite the frequency of chlormethine gel application varying from daily to less than once a week, good overall response rates were achieved [18]. That said, in the PROVe study a majority of patients used combination treatments, making the individual contribution of chlormethine gel more difficult to interpret.

An association between the occurrence of contact dermatitis and an improved CAILS response was observed, suggesting that patients who experienced contact dermatitis were more likely to have an improved skin response at the following visit compared with those who did not have this AE. Such a relationship between contact dermatitis or a brisk skin reaction and response has been described in previous studies [14, 16]. In addition, a recent case series reported a higher response rate (5/7 patients, 71%) in patients who experienced dermatitis compared with those who did not have a skin reaction (5/9 patients, 56%) [23], indicating that this signal may also be present in real-world practice. If the occurrence of dermatitis is confirmed as a prognostic marker for response, this would be very valuable for clinicians. The REACH study (NCT04218825) is a future open-label trial that will enroll 100 recently diagnosed (no more than a year ago) adult patients with stage IA–IB MF to compare responses in patients who do or do not have skin-related reactions after treatment with chlormethine gel.

Patients who experience allergic contact dermatitis may need to discontinue gel treatment permanently, while those with irritant contact dermatitis can often continue treatment or restart treatment after a brief interruption, depending on the severity of the reaction. The association seen between dermatitis and response highlights the importance of continuing treatment with chlormethine gel with a modified application schedule and/or the addition of topical corticosteroids, which can help patients to remain on treatment [19, 25, 26].

The results of the current post-hoc analysis need to be interpreted with some caution, as several criteria (e.g., controlled treatment schedule, concentration of chlormethine gel, no concomitant treatment allowed) do not necessarily reflect regular clinical practice. In real-world practice, chlormethine gel is regularly used at different treatment frequencies and in combination with various topical and systemic therapies [18, 27, 28]. In addition, AEs were classified per Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities preferred terms during study 201 and 202. Only those skin-related reactions termed contact dermatitis were included for the association analysis. In practice, it can be difficult to define contact dermatitis and clearly distinguish it from other skin reactions such as erythema and skin irritation. It is possible, therefore, that the number of patients with contact dermatitis was underestimated in this analysis. Patch tests are normally used in clinical practice to estimate and evaluate the type of contact dermatitis, but this was not mandatory during these two studies.

In conclusion, this post-hoc analysis of study 201 and study 202 shows that patients who used chlormethine gel during both the 12-month period of study 201 and the 7-month extension period of study 202 had faster and more improved CAILS responses than patients who used chlormethine ointment during study 201. As the development of contact dermatitis may be a prognostic factor for response, patients should be maintained on chlormethine gel treatment when this AE occurs, through treatment adjustments frequency or combining chlormethine gel treatment with corticosteroids, when possible.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the volunteers, investigators, and the study teams at the centers participating in these studies, and thank Erminio Bonizzoni, PhD, from the University of Milan, Italy, for performing the statistical analyses for the study. Editorial and medical writing assistance was provided by Judith Land, PhD, from Aptitude Health, The Hague, the Netherlands, funded by Helsinn Healthcare SA. The authors are fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions for this manuscript.

Declarations

Funding

Helsinn Healthcare SA was involved in reviewing of the manuscript according to Good Publication Practices (https://www.ismpp.org/gpp3). Writing and editorial assistance was funded by Helsinn Healthcare SA.

Conflict of interest

C. Querfeld: Research grant: Celgene; clinical investigator: Helsinn, Celgene, Trillium, miRagen, Bioniz, Kyowa Kirin; advisory board: Helsinn, miRagen, Bioniz, Almirall, Trillium, Kyowa Kirin, Stemline Therapeutics. J.J. Scarisbrick: Consultancy: Takeda, Helsinn, Recordati, 4SC, Kyowa, Mallinckrodt, miRagen; research grant: Kyowa. C. Assaf: Advisory board: 4SC, Takeda, Helsinn, Innate Pharma, Recordati Rare Diseases, Kyowa. Y.H. Kim: Steering committee and research funding: Eisai; research funding: Forty Seven; advisory board member: Seattle Genetics; steering committee member, advisory board, and research funding: Kyowa Hakko Kirin; research funding: Portola, Horizon; research funding: Soligenix; steering committee, advisory board, research funding: Innate; research funding: Elorac; advisory board and research funding: Galderma; steering committee and research funding: Corvus; research funding Trillium. J. Guitart: Research support: Galderma, Soligenix; scientific advisory board: Kyowa Kirin. P. Quaglino: Advisory board: 4SC, Takeda, Actelion, Innate Pharma, Helsinn, Recordati Rare Diseases, Kyowa, Therakos. E. Hodak: Scientific advisory board: Actelion, Helsinn, Recordati Rare Diseases, Takeda; speakers’ bureau: Helsinn, Rafa, Takeda.

Ethics approval

The study protocols were approved by institutional review boards of the participating centers and complied with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

All patients provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

Concept and design: CQ, JJS, CA, YHK, JG, PQ, EH. Drafting of the article or critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: CQ, JJS, CA, YHK, JG, PQ, EH. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Willemze R, Hodak E, Zinzani PL, Specht L, Ladetto M, ESMO Guidelines Committee Primary cutaneous lymphomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:30–40. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim EJ, Hess S, Richardson SK, Newton S, Showe LC, Benoit BM, et al. Immunopathogenesis and therapy of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:798–812. doi: 10.1172/JCI24826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trautinger F, Eder J, Assaf C, Bagot M, Cozzio A, Dummer R, et al. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer consensus recommendations for the treatment of mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome—update 2017. Eur J Cancer. 2017;77:57–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilson D, Whittaker SJ, Child FJ, Scarisbrick JJ, Illidge TM, Parry EJ, et al. British association of dermatologists and U.K. Cutaneous Lymphoma Group guidelines for the management of primary cutaneous lymphomas 2018. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:496–526. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines (NCCN Guidelines®) Primary cutaneous lymphomas. Version 2.2021. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/primary_cutaneous.pdf. Accessed 10 Nov 2021.

- 6.Haserick JR, Richardson JH, Grant DJ. Remission of lesions in mycosis fungoides following topical application of nitrogen mustard: a case report. Cleve Clin J Med. 1959;26:144–147. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.26.3.144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valchlor (mechlorethamine) [prescribing information]. Iselin, NJ: Helsinn Therapeutics (U.S.), Inc.; 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/202317s009lbl.pdf. Accessed 10 Nov 2021.

- 8.Ledaga [prescribing information]. Jerusalem, Israel: Rafa Laboratories Ltd.; 2020. https://mohpublic.z6.web.core.windows.net/IsraelDrugs/Rishum_17_462433720.pdf. Accessed 10 Nov 2021.

- 9.Ledaga [summary of product characteristics]. Dublin, Ireland: Helsinn Birex Pharmaceuticals Ltd.; 2017. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/ledaga-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 10 Nov 2021.

- 10.Chang YT, Ignatova D, Hoetzenecker W, Pascolo S, Fassnacht C, Guenova E. Increased chlormethine-induced DNA double-stranded breaks in malignant T cells from mycosis fungoides skin lesions. JID Innov. 2021;2:100069. doi: 10.1016/j.xjidi.2021.100069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Querfeld C, Geskin LJ, Kim EJ, Scarisbrick JJ, Quaglino P, Papadavid E, et al. Lack of systemic absorption of topical mechlorethamine gel in patients with mycosis fungoides cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141:1601–1604.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2020.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lessin SR, Duvic M, Guitart J, Pandya AG, Strober BE, Olsen EA, et al. Topical chemotherapy in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: positive results of a randomized, controlled, multicenter trial testing the efficacy and safety of a novel mechlorethamine, 0.02%, gel in mycosis fungoides. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:25–32. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamadermatol.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen EA, Whittaker S, Kim YH, Duvic M, Prince HM, Lessin SR, et al. Clinical end points and response criteria in mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a consensus statement of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas, the United States Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium, and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2598–2607. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.0630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Querfeld C, Scarisbrick JJ, Assaf C, Guenova E, Bagot M, Ortiz-Romero PL, et al. Post hoc analysis of a randomized, controlled, phase 2 study to assess response rates with chlormethine/mechlorethamine gel in patients with stage IA–IIA mycosis fungoides. Dermatology. 2021 doi: 10.1159/000516138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Querfeld C, Kim YH, Guitart J, Scarisbrick J, Quaglino P. Use of chlormethine 0.04% gel for mycosis fungoides after treatment with topical chlormethine 0.02% gel: a phase 2 extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim YH, Martinez G, Varghese A, Hoppe RT. Topical nitrogen mustard in the management of mycosis fungoides: update of the Stanford experience. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:165–173. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talpur R, Venkatarajan S, Duvic M. Mechlorethamine gel for the topical treatment of stage IA and IB mycosis fungoides-type cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2014;7:591–597. doi: 10.1586/17512433.2014.944500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim EJ, Guitart J, Querfeld C, Girardi M, Musiek A, Akilov OE, et al. The PROVe study: US real-world experience with chlormethine/mechlorethamine gel in combination with other therapies for patients with mycosis fungoides cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:407–414. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00591-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prag Naveh H, Amitay-Laish I, Zidan O, Leshem YA, Sherman S, Noyman Y, et al. Real-life experience with chlormethine gel for early-stage mycosis fungoides with emphasis on types and management of cutaneous side-effects. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021 doi: 10.1080/09546634.2021.1967266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geskin LJ, Bagot M, Hodak E, Kim EJ. Chlormethine gel for the treatment of skin lesions in all stages of mycosis fungoides cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a narrative review and international experience. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1085–1106. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00539-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klucel™ hydroxypropylcellulose. Physical and chemical properties. Ashland Inc.; 2017. https://www.ashland.com/file_source/Ashland/Product/Documents/Pharmaceutical/PC_11229_Klucel_HPC.pdf. Accessed 10 Nov 2021.

- 22.Giuliano C, Frizzarin S, Beuttel C, Powell K, Alonzi A, Stimamiglio V, et al. Percutaneous absorption of chlormethine gel in human skin: in vitro permeation testing. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141:S171. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2021.08.137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wehkamp U, Jost M, Gosmann J, Grote U, Bernard M, Stadler R. Management of chlormethine gel treatment in mycosis fungoides patients in two German skin lymphoma centers. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2021;19:1057–1059. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pichler WJ, Hausmann O. Classification of drug hypersensitivity into allergic, p-i, and pseudo-allergic forms. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2016;171:166–179. doi: 10.1159/000453265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilmore ES, Alexander-Savino CV, Chung CG, Poligone B. Evaluation and management of patients with early-stage mycosis fungoides who interrupt or discontinue topical mechlorethamine gel because of dermatitis. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:878–881. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alexander-Savino CV, Chung CG, Gilmore ES, Carroll SM, Poligone B. Randomized Mechlorethamine/Chlormethine Induced Dermatitis Assessment Study (MIDAS) establishes benefit of topical triamcinolone 0.1% ointment cotreatment in mycosis fungoides. Dermatol Ther. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00681-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dugre F, Lefebure A, Martelli S, Pin M, Maubec E, Arnaud F. Chlormethine gel: effectiveness and tolerance to treat mycosis fungoides. Int J Clin Pharm. 2017;39:252. doi: 10.1007/s11096-016-0404-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lampadaki K, Koumourtzis M, Karagianni F, Marinos L, Papadavid E. Chlormethine gel in combination with other therapies in the treatment of patients with mycosis fungoides cutaneous T cell lymphoma: three case reports. Adv Ther. 2021;38:3455–3464. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01721-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.