Abstract

Escherichia coli lineage ST131 is an important cause of urinary tract and bloodstream infections worldwide and is highly resistant to antimicrobials. Specific ST131 lineages carrying invasiveness-associated papGII pathogenicity islands (PAIs) were previously described, but it is unknown how invasiveness relates to the acquisition of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). In this study, we analysed 1638 ST131 genomes and found that papGII+ isolates carry significantly more AMR genes than papGII-negative isolates, suggesting a convergence of virulence and AMR. The prevalence of papGII+ isolates among human clinical ST131 isolates increased dramatically since 2005, accounting for half of the recent E. coli bloodstream isolates. Emerging papGII+ lineages within clade C2 were characterized by a chromosomally integrated blaCTX-M-15 and the loss and replacement of F2:A1:B- plasmids. Convergence of virulence and AMR is worrying, and further dissemination of papGII+ ST131 lineages may lead to a rise in severe and difficult-to-treat extraintestinal infections.

Subject terms: Bacterial genes, Population genetics

Genomic analyses indicate that the ST131 lineage of E. coli, responsible for urinary and bloodstream infections globally, is evolving towards both increased virulence and increased resistance to antimicrobials.

Introduction

A large proportion of human urinary tract and bloodstream infections are caused by a few globally dispersed E. coli clones, including sequence type (ST) 69, ST73, ST95, and ST1311. Despite its recent emergence, ST131 is the dominant multi-drug resistant clone among extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) isolates today2. In particular, high rates of resistance to 3rd-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones among ST131 isolates present a major public health risk, leading to its classification as a critical priority pathogen by the WHO3.

The ST131 population is phylogenetically divided into clades A, B, and C. Clade C can be further divided into subclades C0, C1, and C2. The latter two harbour chromosomal mutations in quinolone-resistance determining regions (QRDR) of gyrA and parC, conferring high-level fluoroquinolone resistance. The emergence of the most recent common ancestor of subclades C1 and C2 was dated to 1992, which coincided with increased fluoroquinolone use worldwide4–6. The expansion of subclade C2, which represents the bulk of the current ST131 pandemic, is assumed to have been driven by the acquisition of a specific IncFII plasmid (plasmid multilocus sequence type [pMLST] F2:A1:B-) carrying blaCTX-M-15 (extended-spectrum beta-lactamase [ESBL]). Isolates of subclade C1 frequently harbour the ESBL-encoding genes blaCTX-M-14 or blaCTX-M-27, whereas ESBLs are less prevalent in clade A and B4–9.

ST131 colonizes the human gastrointestinal tract as a commensal but causes mild to severe infections in the urinary tract including pyelonephritis and urosepsis. Specific ST131 sublineages are also overrepresented among asymptomatic bacteriuria10,11, which may be explained by varying underlying virulence profiles in these sublineages. Irrespective of their clade affiliation, most ST131 isolates carry mobile genetic elements encoding synthesis of the siderophores aerobactin (iuc) and yersiniabactin (ybt), two important factors promoting extraintestinal colonization12,13. Other virulence factors such as hly (hemolysin), iro (salmochelin siderophore), agg (aggregative adherence fimbriae AAF), or papGII (P fimbrial tip adhesin variant PapGII) are restricted to specific ST131 sublineages11,14,15. Of particular significance is papGII, which was recently identified as a key determinant of invasive uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) in infection experiments and genome-wide association studies11,16,17. Approximately 60% of E. coli isolates from invasive urinary tract infections (i.e., pyelonephritis or bacteremia with a urinary portal of entry) carry papGII, while the gene is less common among isolates from patients with cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria11. PapGII drives inflammation and renal tissue damage through transcriptional activation of signalling pathway genes in kidney cells, resulting in kidney and bloodstream infections16. Overall, approximately half of all E. coli bacteremia cases are associated with an entry through the urinary tract18–20.

ST131 comprises multiple sublineages that independently acquired papGII-containing pathogenicity islands (papGII PAIs)11,21. Currently, it is unknown how the antimicrobial resistance gene (ARG) content relates to these papGII-containing (papGII+) lineages. Dissemination of highly resistant and more invasive lineages would aggravate the global burden of already difficult-to-treat infections caused by E. coli.

In E. coli, virulence and AMR are frequently encoded by mobile genetic elements such as plasmids, genomic islands (PAIs and resistance islands [REIs]), bacteriophages, or transposons22–24. Relative high rates of acquisitions of mobile genetic elements with a highly dynamic accessory genome9 make E. coli ST131 an interesting model to examine the co-evolution of AMR and virulence. In this study, we investigate the population structure, resistome, and distribution of papGII in ST131 using 1638 publicly available genomes of human isolates. Our results reveal significant evolutionary changes and a genetic convergence of virulence and AMR in increasingly prevalent papGII+ sublineages of ST131.

Results

Isolate collections and resistome

Publicly available genomes of 1638 E. coli ST131 isolates were analysed in this study. These included 1538 whole-genome draft assemblies from 11 collections and 100 high-quality reference assemblies (Supplementary Data 1). The isolates originated from human bloodstream infections (n = 843), urinary tract infections (n = 306), feces (n = 83), and other (n = 9) or unknown (n = 397) clinical sources, and were isolated between 2001 and 2017 in Europe, North America, Asia, and Oceania (Table 1). In eight of the 11 source studies (comprising 1148 isolates), isolates were specifically selected for being ESBL-producing. Genome sizes ranged from 4.69 Mb to 5.73 Mb, and all assemblies passed quality control (N50 > 45 kb, >99% completeness).

Table 1.

Isolate collections included in this study.

| Collection | No. ST131 isolates | Clinical source | Pre-selection of isolates | Time and country of isolation | NCBI Bioproject accession | Source study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birgy | 94 | fUTI | ESBL+ | 2014–2016, France | PRJNA551371 | Birgy et al.66 |

| Froeding | 122 | BSI | ESBL+ | 2012–2015, Sweden | PRJNA612606 | Froeding et al.08 |

| Harris | 43 | BSI | ESBL+ | 2014–2015, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore | PRJNA398288 | Harris et al.67 |

| Kallonen | 221 | BSI | - | 2001–2012, UK | PRJEB4681 | Kallonen et al.14 |

| Kossow | 71 | feces | ESBL+ | 2015–2016, Germany | PRJEB23208 | Kossow et al.68 |

| Ludden | 90 | urine (n = 80), BSI (n = 4), sputum (n = 4), feces (n = 2) | ESBL+ (partly) | 2005–2011, Ireland | PRJEB2974 | Ludden et al.6 |

| MacFadden | 87 | BSI | – | 2010–2015, Canada | PRJNA521038 | MacFadden et al.69 |

| Miles-Jay | 130 | urine (n = 123), BSI (n = 4), bone (n = 3) | ESBL+, fimH30 | 2009–2013, US | PRJNA578285 | Miles-Jay et al.70 |

| Roer | 259 | BSI | ESBL+ | 2014–2015, Denmark | PRJEB20792 | Roer et al.71 |

| Septicoli | 82 | BSI | – | 2016–2017, France | PRJEB35745 | De Lastours et al.72 |

| SoM-study | 339 | n.r. | ESBL+ | 2011–2014, Netherlands | PRJEB15226 | Kluytmans-van den Bergh et al.73 |

fUTI febrile urinary tract infection, BSI bloodstream infection, n.r. not reported, ESBL+ extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing E. coli

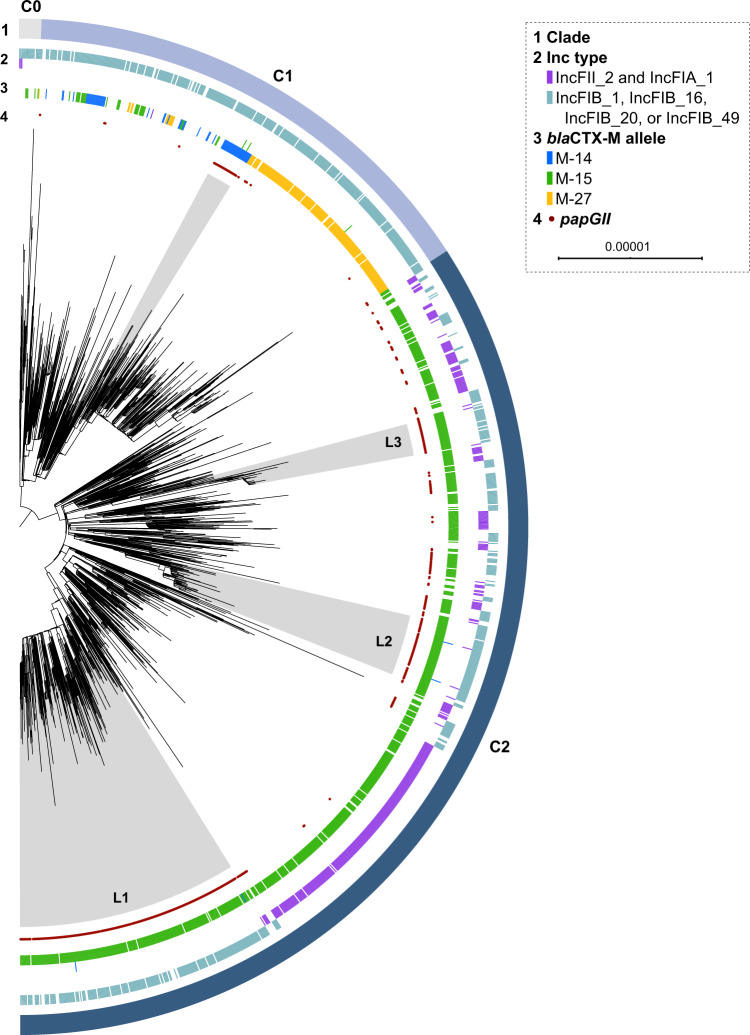

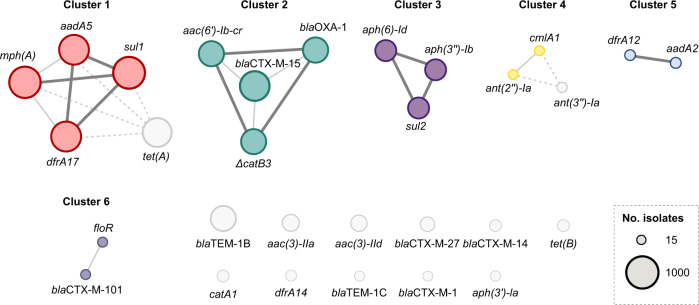

Overall, 102 distinct ARGs were identified in the ST131 isolates (Supplementary Data 2). In agreement with previous studies9, clade C2 was strongly associated with the presence of blaCTX-M-15 (found in 89% of C2 isolates), while the presence of ESBL genes (including blaCTX-M-1, M-14, M-15, M-27, and M-101) in other clades was more variable and often confined to specific sublineages (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1). Multiple ARGs showed co-occurrence, suggesting co-acquisition, co-location, and co-selection during antibiotic exposure (Fig. 2). Eleven ARGs typically (in 73–100% of all individual occurrences) co-occurred in one of three clusters: (1) aadA5, dfrA17, mph(A), and sul1 (Fig. 2 cluster 1); (2) aac(6′)-lb-cr, blaCTX-M-15, blaOXA-1, and (Δ)catB3 (Fig. 2 cluster 2); and (3) aph(3″)-Ib, aph(6)-Id, and sul2 (Fig. 2 cluster 3). The eleven ARGs individually accounted for 71.3% of the entire ST131 ARG content. Cluster 1 was common in clade A (42.5% of all A isolates), C1 (54.7%), and C2 (56.8%), but uncommon in clade B (4.8%). Cluster 2 occurred almost exclusively in clade C2 (70.0% of all C2 isolates) and in ≤ 2% of clade A, B, or C1 isolates. Cluster 3 was common in clade A (47.1%), B (31.0%), and C1 (57.4%) and uncommon in C2 (4.4%). None of the clusters showed a clear co-occurrence pattern (i.e., Jaccard distance <0.3) with any of the 55 detected alleles from the IncF plasmid replicon family or 41 plasmid replicon types from other families.

Fig. 1. Phylogenetic tree of ST131 clade C.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of 1338 clade C0, C1, and C2 isolates based on 10,904 variable sites in a 2.5 Mb core genome alignment. Each isolate is annotated with ST131 subclade affiliation (ring 1), presence of selected IncF plasmid replicon types (pMLST; ring 2), blaCTX-M allele (ring 3), and papGII gene (ring 4). ST131 papGII-containing sublineages discussed in the text are shaded in grey. Those of clade C2 are annotated with L1, L2, and L3. The scale bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. The tree was visualized using iTOL74. Supplementary Fig. 2 shows this tree with additional information.

Fig. 2. Co-occurrence network graph of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs).

ARGs occurring in at least 15 isolates are shown. Circle sizes correspond to the number of occurrences. Co-occurring genes are connected according to the co-occurrence level in thick (Jaccard distance [JD] < 0.15 [commonly co-occurring]), thin (JD 0.15–0.3), or dashed (JD 0.3–0.5) lines.

Sublineages with papGII+ isolates are associated with increased AMR

Phylogenetic analyses showed one papGII+ sublineage each in clades A, B, and C1, consistent with previous work11. Most papGII+ isolates (444/547, 81.1%) belonged to clade C2, which harboured multiple papGII+ sublineages, including three major papGII+ sublineages (named L1, L2, and L3; Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). The largest papGII+ sublineage (clade C2 sublineage L1) comprised almost half of all papGII+ isolates (230/547, 42.0%). High-quality assemblies and contig homologies confirmed the predominance of type III papGII PAIs within the ST131 population, but type II and type IV papGII PAIs were also identified (Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 4).

papGII+ isolates presented with an increased ARG content: on average, papGII+ isolates harboured 8.7 ARGs (median 9; SD 3.6) versus 6.3 ARGs (median 7; SD 3.7) among papGII-negative isolates. The positive association between papGII presence and ARGs was found to be significant (Padj < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test) within each of the ST131 clades A, B, C1, and C2 and across different isolation time intervals (Supplementary Table 3). This significant association was also found irrespective of whether isolates were pre-selected for being ESBL-producing and among urinary and blood isolates. The increased ARG content was not significant among faecal isolates, for which limited data was available. This association was confirmed using an extended dataset, comprising assemblies of the main dataset and 3,608 additional assemblies of human ST131 isolates from EnteroBase. The extended dataset showed that papGII+ isolates from bloodstream infections carry similar numbers of ARGs than papGII+ isolates of urinary or faecal origin. Regardless of their source, significantly more ARGs were found among papGII+ isolates than among papGII-negative isolates (Supplementary Table 4). As the acquisition of papGII occurs via PAIs25 and acquisition of ARGs predominantly via plasmids24, virulence and AMR acquisition likely occurred independently. Among the 30 resolved papGII+ PAIs from high-quality assemblies, only one contained ARGs within the same PAI (Supplementary Table 2).

The difference in the ARG content between papGII+ and papGII-negative isolates could not be attributed to one specific ARG or AMR class. When stratified by clade, different ARGs were significantly (Padj < 0.05, Fisher’s exact test) associated with papGII+ isolates, including those conferring resistance against 3rd-generation aminoglycosides, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, sulfamethoxazole, and trimethoprim (Table 2, Supplementary Table 5, Supplementary Fig. 5).

Table 2.

Acquired antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) significantly (Padja < 0.05) associated with papGII-containing (papGII+) versus papGII-negative isolates.

| ARG | Resistance class | ARG co-occurrence cluster | Prevalence papGII+ isolates (n = 547) | Prevalence papGII-negative isolates (n = 1091) | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aac(3)-IIa | Aminoglycoside | – | 238 (43.5%) | 85 (7.8%) | 9.1 (6.9–12.0) |

| aac(3)-IId | Aminoglycoside | – | 136 (24.9%) | 160 (14.7%) | 1.9 (1.5–2.5) |

| aac(6’)-Ib-cr | Aminoglycoside, Fluoroquinolone | Cluster 2 | 375 (68.6%) | 320 (29.3%) | 5.3 (4.2–6.6) |

| aadA2 | Aminoglycoside | Cluster 5 | 45 (8.2%) | 28 (2.6%) | 3.4 (2.1–5.5) |

| blaCTX-M-15 | Beta-lactam (ESBL) | Cluster 2 | 435 (79.5%) | 455 (41.7%) | 5.4 (4.3–6.9) |

| blaCTX-M-27 | Beta-lactam (ESBL) | – | 28 (5.1%) | 188 (17.2%) | 0.26 (0.17–0.39) |

| blaCTX-M-101 | Beta-lactam (ESBL) | Cluster 6 | 26 (4.8%) | 1 (0.1%) | 54.4 (7.4–401.9) |

| blaOXA-1 | Beta-lactam | Cluster 2 | 374 (68.4%) | 324 (29.7%) | 5.1 (4.1–6.4) |

| catA1 | Phenicol | – | 78 (14.3%) | 16 (1.5%) | 11.2 (6.5–19.3) |

| (Δ)catB3 | Phenicol | Cluster 2 | 372 (68.0%) | 318 (29.1%) | 5.2 (4.1–6.5) |

| dfrA12 | Trimethoprim | Cluster 5 | 45 (8.2%) | 21 (1.9%) | 4.6 (2.7–7.7) |

| dfrA14 | Trimethoprim | – | 34 (6.2%) | 27 (2.5%) | 2.6 (1.6–4.4) |

| floR | Phenicol | Cluster 6 | 25 (4.6%) | 6 (0.5%) | 8.7 (3.5–21.2) |

| tet(B) | Tetracycline | – | 56 (10.2%) | 43 (3.9%) | 2.8 (1.8–4.2) |

aFisher’s exact text, Bonferroni corrected for the overall number of identified ARGs (n = 102).

papGII+ sublineages in clades A, B, and C1 were marked by the presence of blaCTX-M-27, blaCTX-M-101, and blaCTX-M-14, respectively (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1). In clade C2, most isolates (88.8%) harboured blaCTX-M-15 irrespective of papGII presence. Because papGII+ isolates were enriched in clade C, a higher proportion of papGII+ isolates contained >3 chromosomal mutations in QRDRs (88.1% vs 77.5% of papGII-negative isolates, P < 0.001 [Fisher’s exact test], OR = 2.2 [95% CI 1.6–2.9]). Overall, 85.2% of papGII+ isolates were predicted to be resistant to both ciprofloxacin (mediated by QRDR mutations or aac(6’)-Ib-cr) and 3rd generation cephalosporins (mediated by ESBL) compared to 59.8% of papGII-negative isolates (P < 0.001 [Fisher’s exact test], OR = 3.9 [95% CI 3.0–5.0]). In the three isolate collections originally not pre-selected for ESBL-producing E. coli, 72.4% of papGII+ isolates were predicted to be resistant against both ciprofloxacin and 3rd generation cephalosporins, compared to 26.1% of papGII-negative isolates (P < 0.001 [Fisher’s exact test], OR 7.4 [95% CI 4.2–13.0]).

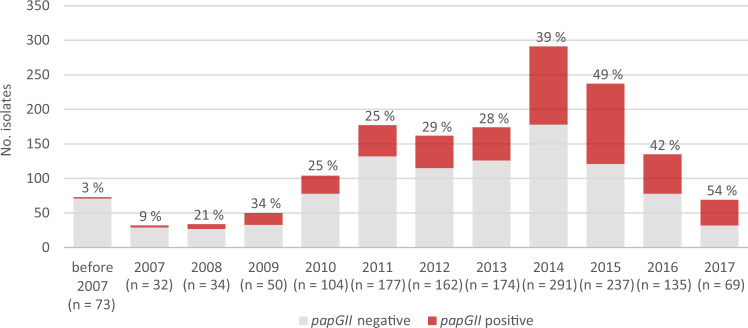

C2 papGII+ sublineages are increasingly prevalent and frequently harbour chromosomal blaCTX-M-15

Before 2007, papGII was rarely identified in ST131 isolates. Since then, the proportion of papGII+ isolates in the investigated ST131 population has increased and accounted for approximately 50% of the most recently (2015–2017) collected isolates (Fig. 3). The gradual increase in the prevalence of papGII since approximately the year 2005 was confirmed in the validation dataset of 3,608 ST131 genomes from human isolates available on EnteroBase. In this dataset, the proportion of papGII+ isolates increased from 8% before 2007 to 28–35% in recent years (2016–2019) among all human isolates and to 46–61% among human blood isolates (Supplementary Fig. 7). The proportion was strongly influenced by the isolates’ clinical source with papGII being more frequently detected in blood isolates (475/789, 39.8%) than in urine/UTI-associated isolates (255/936, 27.2%; P < 0.001 [Fisher’s exact test]; OR 4.0 [95% CI: 3.3–4.9]) or faecal isolates (65/513, 12.7%; P < 0.001; OR 10.4 [95% CI:7.7–14.0]).

Fig. 3. Proportion of papGII-containing isolates in the ST131 population over time.

1538 isolates from the 11 investigated collections were analysed. The proportion of papGII-containing isolates per year is coloured in red and the percentage is indicated above each bar. The total number of isolates per year is given in brackets. A plot showing the cumulative proportion of papGII-containing isolates is shown in Supplementary Fig. 6.

Clade C2 is a major cause of the ongoing ExPEC pandemic6–8 and the success of early clade C2 sublineages has been attributed in part to the stable maintenance of pMLST F2:A1:B- plasmids containing blaCTX-M-155,26. Here we observed that the plasmid replicon profile in clade C2 differed between papGII+ and papGII-negative isolates. Among clade C2 isolates, putative F2:A1:B- plasmids (indicated by the presence of both pMLST alleles FII_2 and FIA_1 in an assembly) were found in 327 (69.7%) papGII-negative isolates but in only 26 (5.9%; OR 37.0 [95% CI: 23.8–57.6]) papGII+ isolates (Fig. 1). In contrast, clade C2 papGII+ isolates were associated with various IncFIB replicon types: 361 (81.3%) papGII+ isolates carried FIB_1, FIB_16, FIB_20, or FIB_49, versus 85 (18.1%; OR 19.6 [95% CI: 14.1 – 27.5]) papGII-negative isolates. The three major clade C2 papGII+ sublineages L1, L2, and L3 were associated with FIB_1, FIB_49, and FIB_1, respectively (Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 2). More specifically, L1 isolates predominantly contained pMLST alleles FII_31 (50% of all L1 isolates), FII_36 (41%), FIA_4/FIA_20 (79%), and FIB_1 (83%); L2 isolates contained FII_48 (86%), FIA_1 (100%), FIA_6 (100%), and FIB_49 (97%); and L3 isolates contained FII_36 (85%) and FIB_1 (82%). blaCTX-M-15 was identified in the majority of C2 isolates irrespective of the present plasmid replicon type (in 302/353 [85.6%] isolates carrying FII_2 and FIA_1; and in 414/446 [92.8%] isolates carrying FIB_1, FIB_16, FIB_20, or FIB_49). These observations imply that in clade C2 papGII+ isolates, ESBLs are generally not located on F2:A1:B- plasmids.

Table 3.

Characteristics of dominant ST131 papGII-containing (papGII+) sublineages.

| papGII+ sublineage | No. isolates | papGII+ PAI type | Dominant IncF pMLST alleles | Dominant ESBL-encoding genes | Dominant genetic context of ESBL-encoding genes (locus; evidence) | Representative isolate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| papGII+ sublineage clade A | 24 | III | FII_29, FIB_10 | blaCTX-M-27 (n = 24) | chromosomal (near gspD; found in 22/24 isolates with resolved context) | A17EC0155 (GCF_021133255.1) |

| papGII+ sublineage clade B (fimH27) | 39 | II and III | FII_1, FIB_63 | blaCTX-M-101 (n = 27), blaCTX-M-15 (n = 5) | not resolved | RDE6 (GCA_013027405.1) |

| papGII+ sublineage clade C1 | 27 | III | FII_1, FIA_2, FIA_6, FIB_20 | blaCTX-M-14 (n = 27) | chromosomal (near cmtA; found in 12/14 isolates with resolved context) | 222A118 (GCF_020230335.1) |

| papGII+ sublineage clade C2 L1 | 236 | III | FII_31, FII_36, FIA_20/FIA_4, FIB_1 | blaCTX-M-15 (n = 225) | subbranch L1b (n = 52): not resolved, subbranch L1a (n = 184): chromosomal (near metG; found in 10/10 isolates with resolved context; 184 isolates with disrupted DUF4132 region) | US02 (GCA_014140815.1) |

| papGII+ sublineage clade C2 L2 | 65 | IV | FII_48, FIA_1, FIA_6, FIB_49 | blaCTX-M-15 (n = 65) | chromosomal (into mppA; found in 59/61 isolates with resolved context; 64 isolates with disrupted mppA) | 2/0 (GCA_003856635.1) |

| papGII+ sublineage clade C2 L3 | 34 | III | FII_36, FIB_1 | blaCTX-M-15 (n = 34) | chromosomal (into ydhS; found in 14/18 isolates with resolved context) | ESBL41 (GCF_007109465.1) |

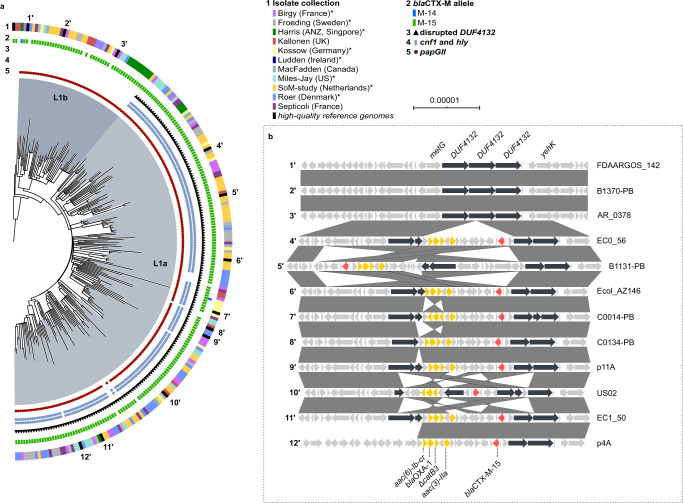

Isolates from the three major papGII+ sublineages in clade C2 typically harboured blaCTX-M-15 integrated into the chromosome (Table 3). In the largest ST131 papGII+ sublineage L1 (clade C2; 236 isolates, including 6 papGII-negative isolates), a subbranch (L1a, 184 isolates) was characterized by a blaCTX-M-15-containing transposon TnMB1860 integrated into the chromosomal metG/DUF4132/yeh region (Fig. 4). TnMB1860 was previously described for a clade C2 isolate by Shropshire et al.27 and additionally contains aac(3)-IIa, aac(6’)-Ib-cr, blaOXA-1, a truncated (Δ)catB3, and tmrB. Unlike isolates of subbranch L1b, L1a isolates also contained virulence-associated genes encoding the toxins hemolysin (hly) and cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 (cnf1) on their papGII+ PAI. Four isolates that fell into the L1a lineage lacked papGII, hly, cfn1, and ucl, suggesting that they lost the entire PAI. L1 consisted of isolates from all collections except one (Ludden), suggesting global dissemination (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 4. Phylogeny and characteristics of the dominant ST131 papGII+ sublineage L1 (clade C2).

a Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of 236 isolates of the clade C2 branch encompassing the dominant papGII+ sublineage L1 (including 6 papGII-negative isolates) and EC958 (clade C2) as outgroup. The tree is based on 2,790 variable sites in a 3.4 Mb core genome alignment. The two major subbranches (L1a and L1b) of L1 are shaded in different colours. Each isolate is annotated with the source collection (ring 1), blaCTX-M allele (ring 2), disruption of the DUF4132 region (ring 3), and presence of hly, cnf1 (ring 4), and papGII (ring 5). Collections that consisted only of ESBL isolates are labelled with an asterisk in the legend. The number of substitutions per core genome alignment site is indicated by the scale bar. The tree was visualized using iTOL74. Numbers at the outermost ring refer to the 12 isolates with high-quality assemblies and resolved DUF4132 region, which are illustrated in panel b. Sublineage L1 was unambiguously defined within the ST131 population by a distinct mtlD allele (encoding a mannitol dehydrogenase family protein; 96% sequence identity to the mtlD allele of other ST131 isolates; Genbank accession number TLH04005.1) b Genetic context of the DUF4132 region in high-quality assemblies from 12 isolates of papGII+ sublineage L1. All 9 isolates of subbranch L1a (isolates 4′ to 12′) harboured TnMB1860 with the resistance genes aac(3)-IIa, aac(6’)-Ib-cr, blaOXA-1, blaCTX-M-15, and ΔcatB3 inserted into the chromosomal DUF4132 region. Vertical boxes between sequences indicate shared homologies (100% identity). Sequence comparisons were performed using EasyFig64.

The second-largest ST131 papGII+ sublineage L2 (clade C2; 64 isolates, including 6 papGII-negative isolates) harboured a blaCTX-M-15-containing transposon chromosomally integrated into mppA (encoding a murein peptide-binding protein), as described previously by Ludden et al.6. Sublineage L2 consisted mostly of isolates from a single outbreak-associated collection obtained in Ireland (Supplementary Fig. 2).

The third-largest ST131 papGII+ sublineage L3 (clade C2; 34 isolates) was epidemiologically more diverse with isolates originating from Asia, Europe, and North America (Supplementary Fig. 2). In 14 isolates, blaCTX-M-15 was chromosomally integrated into ydhS (encoding a putative oxidoreductase); in 4 isolates blaCTX-M-15 was integrated at other chromosomal positions (near aphA, ghrB, ubiX, or into prophage mEp460); in one isolate it was located on a plasmid; and in the remaining 15 isolates, the blaCTX-M-15 genetic context could not be resolved from short-read assemblies. Also in papGII+ sublineages of ST131 clades A and C1, blaCTX-M genes were often chromosomally integrated (Table 3). Incomplete assemblies from short-read data did however not allow a systematic evaluation of papGII+ versus papGII-negative isolates.

Discussion

Our genomic study of global public ST131 data suggests a convergence of virulence and AMR in increasingly prevalent papGII+ E. coli ST131 sublineages. ARGs enriched in papGII+ isolates included those conferring resistance against fluoroquinolones, 3rd-generation cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, which are important treatment options for urinary tract infections and bacteraemia. Most papGII+ sublineages expanded after the year 2005 within the multi-drug resistant clade C2, implying that PAIs harbouring papGII+ were acquired after AMR determinants such as the clade C-specific QRDR mutations and blaCTX-M-15. However, also within this clade C2, we observed higher levels of AMR in papGII+ isolates compared to papGII-negative isolates, suggesting a further synergy between AMR and virulence. We assume that virulence genes may contribute to the maintenance and further acquisition of ARGs by causing more severe disease which needs more extensive treatment. UPEC typically reside in the gut implying that antibiotic treatment for UTI may create evolutionary pressure both in the gut and at the site of infection23,28. Increased AMR may hence result in prolonged extraintestinal colonization, intestinal blooms, and eventually enhanced dissemination of specific UPEC clones29. The observed convergence of AMR and virulence in ST131 may not be generalized to other E. coli lineages. For example, the pandemic E. coli lineages ST73 and ST95 frequently cause extraintestinal infections but AMR levels remain relatively low without leading to a displacement by more resistant lineages11,14,30. This might be explained by differences between lineages in their ability to acquire genes and integrate them into regulatory and functional processes, or by their different lifestyles and occupation of niches31,32.

While the success of early clade C2 sublineages was partly attributed to the maintenance of pMLST F2:A1:B- plasmids containing blaCTX-M-155, we observed that the more recently emerged papGII+ sublineages within clade C2 were characterized by the presence of various IncFIB plasmids and chromosomally encoded blaCTX-M-15. Transpositions of blaCTX-M-15 from the plasmid to the chromosome of clade C2 isolates have been described in multiple prior studies5,6,9,27,33,34. The chronological order of AMR and papGII acquisitions could not be elucidated with confidence from our data. Conceivably, (i) transposition of blaCTX-M-15 from an F2:A1:B- plasmid to the chromosome was followed by (ii) the loss of F2:A1:B- plasmids, (iii) the acquisition of FIB plasmids, and (iv) the acquisition of papGII+ PAIs. Varying selective advantages of plasmids or plasmid-PAI incompatibilities may underly the co-presence of papGII+ and IncFIB in clade C2. Specific plasmids may for example be involved in the horizontal co-transfer of papGII+ PAIs: E. coli PAIs typically lack mobilization and transfer genes, but conjugative (co-)transfer of UPEC PAIs was previously shown in vitro using helper plasmids35,36. A complex plasmid-island interaction is for example known for S. enterica, where the mobilizable resistance island SGI1 is incompatible with IncC/A plasmids, but relies on those for propagation37.

The increasing dominance of papGII+ ST131 strains has been reported before. Royer et al.21 described an increase of papGII+ from 10 to 46% between 2005 and 2016 in ST131 bloodstream isolates from France. Kallonen et al.14 found an increase of papG from 8 to 44% between 2003 and 2012 in ST131 bloodstream isolates from England. Ludden et al. reported the displacement of a C1 sublineage by a C2 sublineage among residents of a long-term care facility in Ireland between 2005 and 20116. This C2 sublineage carried a chromosomal blaCTX-M-15 and was here found to also harbour papGII.

Sublineage L1a was most abundant among the papGII+ ST131 sublineages. L1a was globally disseminated and characterized by (i) a PAI with papGII, cnf1, and hly, (ii) a chromosomal resistance cassette with aac(3)-IIa, aac(6’)-Ib-cr, blaOXA-1, and blaCTX-M-15, and (iii) frequent carriage of FIB_1 and FIA_4/20 plasmids. Isolates with these features were previously reported by Chen et al.7 among bacteremia isolates collected in 2015 in South East Asia and associated with increased virulence and AMR. Likewise, Pajand et al. described such clade C2 isolates among ST131 isolates from Iran38. An apparent stable integration of blaCTX-M-15 and aac(6’)-Ib-cr might have contributed to its success: in clade C2, the ciprofloxacin-inactivating AAC(6’)-Ib-cr was shown to confer a selective advantage in the presence of ciprofloxacin over isolates that contained QRDR mutations alone39.

A limitation of our study was that 8 of the 11 ST131 collections (1148 isolates) were pre-selected for ESBL-producing isolates, introducing sampling bias. Among those, ESBL genes were detected in 1062 (92.5%) isolates, compared to 146/390 (37.4%) isolates from the 3 remaining collections, suggesting that AMR (in particular ESBL prevalence) was overestimated here. We stratified the statistical analysis by pre-selection criteria to take this into account. In addition, with more than half of all isolates originating from bloodstream infections, papGII-containing isolates are likely also overrepresented in our data relative to the overall ST131 population. Furthermore, the investigated isolates were not available for phenotypic AMR validation. Sensitivities and specificities of AMR genotype-phenotype predictions in E. coli were previously estimated to be >95% and >90%, respectively, for most antibiotics22. Lastly, we were unable to determine the genomic location of most ARGs from the available short-read data. Long-read sequencing of more isolates would allow a better understanding of the observed association between papGII, chromosomal blaCTX-M elements, and specific plasmid replicons, but has not been employed for large collections like the ones studied here due to the high costs.

In conclusion, we describe the convergence of virulence and AMR in papGII+ ST131 sublineages, which is an important concept among emerging pathogens. A similar convergence of virulence and AMR in specific clones has been observed in other pathogens, including K. pneumoniae40, S. enterica41, and S. aureus42. UTIs caused by ST131 papGII+ strains presumably lead to more severe infections and are more challenging to treat with commonly used antibiotics, underlining the need for novel preventive and curative strategies to manage infections.

Methods

Bacterial genomes: main dataset

Genomes of 1638 E. coli ST131 isolates of human origin were included in this study. 1538 genomes originated from 11 publicly available collections. Inclusion criteria for collections were (i) a large number (>40) of ST131 genomes within a single collection, (ii) the availability of metadata, and (iii) a human source of isolation. In addition, 100 public high-quality assemblies (N50 > 1.5 Mb; derived from long-read sequencing) were included for the analyses of mobile genetic elements that could not be resolved in assemblies from short-read data. Assemblies were obtained from EnteroBase43 or NCBI and sequence types were confirmed with the Achtman scheme43 using mlst 2.19.044. Quast v5.2.045 and CheckM v1.1.346 were used for the quality control of assemblies. Assemblies with N50 values of >40 kb were considered acceptable. Details on individual isolates including metadata, assembly methods, assembly metrics, and accession numbers are provided in Supplementary Data 1. For three of the 11 isolate collections, the isolates were annotated with the isolation time period instead of the precise isolation year (Roer: 2014–2015; Septicoli: 2016–2017; SoM study: 2011–2014). To determine trends in the ST131 population over time, those isolates were randomly assigned to years within the given period.

Bacterial genomes: validation dataset

The prevalence of papGII-containing ST131 isolates over time and the association of papGII with different isolation sources were determined using a larger dataset of 3,608 E. coli ST131 genomes. This dataset comprises all ST131 assemblies available on EnteroBase (accessed on 07/01/2021)43 of isolates recovered from human samples (based on BioSample metadata) and annotated with a year of isolation. Assemblies already included in the main dataset and of low assembly quality (N50 < 40 kb) were excluded. Details on the included assemblies are provided in Supplementary Data 3.

Phylogenetic analyses

Core-genome alignments were created using parsnp v1.247 (default options) with chromosomal sequences of EC958 (for clade C, C2, or sublineage L1 alignments), E41-1 (for clade C1 alignments), or SE15 (for clade A/B alignments) as reference genomes. IS elements and repeat regions (>95% identity) detected in the reference genomes with ISEScan v1.7.2.348 (default options) and NUCmer v3.149 (maxmatch and nosimplify options), respectively, were masked in the alignment. Recombination-associated SNPs were filtered out using gubbins v2.4.150 (default parameters). Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees were generated using IQ-TREE v2.0.351 with the generalized time-reversible (GTR) model and gamma distribution with 100 bootstraps to assess confidence. The recombinant-free SNP alignment was passed to IQ-TREE together with the number of invariant sites (fconst option) of each nucleotide in the core genome alignment, as identified using snp-sites v2.5.1 (-C flag)52. Alignment metrics are provided in the figure captions. Phylogenetic clusters were determined by hierarchical Bayesian analysis from SNP alignments using fastbaps v1.0.553 over three levels with optimised BAPS priors. For the BAPS analysis, separate recombinant-free SNP alignments generated as described above were used for clades A/B, C1, and C2. papGII+ sublineages were defined as BAPS clusters consisting of at least 10 isolates of which >90% harboured papGII.

AMR-conferring gene content

Pointfinder v3.1.054 was used to identify chromosomal mutations in QRDRs. Ciprofloxacin resistance was here predicted based on the presence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes or at least four amino acid changes associated with quinolone resistance in GyrA (S83L, S83A, D87G, D87N, D87Y), ParC (S57T, S80I, S80R, E84G, E84V, E84K), or ParE (L445H, S458A, E460D, I529L). Identified mutations are listed in Supplementary Data 4. ARGs were identified using ABRicate v0.9.355 in conjunction with the resfinder database56 (minimum sequence coverage/identity 70%/90%). Network graphs were constructed in R 3.5.0 for ARG combinations co-occurring in at least 15 isolates with a Jaccard distance of <0.5. For each pair of ARGs (ARGA and ARGB), Jaccard distance (1–|ARGA∩ARGB|/|ARGA ∪ ARGB|) were calculated with the vegdist function in the R package vegan v2.5-757 and networks were analysed and visualized using the R package igraph v1.2.658. The genetic context of blaCTX-M genes was inspected manually using CLC sequence viewer 8. Disruptions of the mppA and DUF4132 loci were investigated by determining their BLAST alignment coverage using ABRicate v0.9.3 with mppA (P423_RS08085) and the DUF4132 region (P423_RS12390–P423_RS12392) from strain JJ1886 (GCF_000493755.1) as query. Hits with <90% (mppA) and <70% (DUF4132 region) query coverage were classified as disrupted.

Identification of virulence genes, plasmid replicons, and ST131 clade affiliation

Virulence-associated genes including papGII were identified using ABRicate v0.9.3 (minimum sequence coverage/identity 70/90%) in conjunction with the EcVGDB database59. Assemblies that contained papGII (>70% sequence coverage, >98% sequence identity) were defined as papGII+ isolates. IncF family replicon alleles were identified using the pubMLST RESTful API v1.27.060 (IncF RST scheme) and replicon types of other families with ABRicate v0.9.355 in conjunction with the plasmidfinder database61 (minimum sequence coverage/identity 70%/90%). Isolates were assigned to clades based on phylogenetic clustering. Clade assignment was supported by the presence of QRDR mutations, fimH types identified using FimTyper v1.162, and the phylogenetic distribution of previously typed isolates. Genome assemblies were annotated using Prokka v1.13.363. Comparisons of genomic regions were created using EasyFig v2.2.364 and processed in Inkscape v0.92. papGII+ PAI types were determined by calculating mash distances to reference PAIs using mashtree v1.2.065 and hierarchical clustering (UPGMA) in R v4.0.3 with a distance cut-off of 0.04, as described previously11.

Statistical tests

Statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.5.3. Frequency counts were compared using a two-tailed Fisher’s exact test, while non-normally distributed continuous variables were analysed using the Mann-Whitney U test (two-sided). P values were adjusted for multiple testing using Bonferroni correction and adjusted P values of <0.05 were considered to reflect statistical significance.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 675412.

Author contributions

M.B., P.M., and S.V.P. contextualized the study and its hypotheses; M.B. performed the analyses and wrote the manuscript supervised by S.V.P; P.M., M.N, H.G. contributed with data interpretations; all authors edited and approved the final version.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Astrid von Mentzer, Tim Downing and Leah Roberts for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Luke R. Grinham.

Data availability

All genome assemblies were obtained from public databases. Accession numbers are listed in Supplementary Data 1 (main dataset) and Supplementary Data 3 (validation dataset). Source data for the main figures and calculations can be found in Supplementary Data 1, 2 and 3. All other data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Michael Biggel, Email: michael.biggel@uzh.ch.

Sandra Van Puyvelde, Email: Sandra.VanPuyvelde@uantwerpen.be.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-022-03660-x.

References

- 1.Riley LW. Pandemic lineages of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014;20:380–390. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicolas-Chanoine M-H, Bertrand X, Madec J-Y. Escherichia coli ST131, an Intriguing Clonal Group. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014;27:543–574. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00125-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tacconelli E, et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018;18:318–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben Zakour NL, et al. Sequential acquisition of virulence and fluoroquinolone resistance has shaped the evolution of Escherichia coli ST131. MBio. 2016;7:1–11. doi: 10.3391/mbi.2016.7.1.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoesser N, et al. Evolutionary history of the global emergence of the Escherichia coli epidemic clone ST131. MBio. 2016;7:1–15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02162-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ludden, C. et al. Genomic surveillance of Escherichia coli ST131 identifies local expansion and serial replacement of subclones. Microb. Genomics6, e000352 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Chen SL, et al. The higher prevalence of extended spectrum beta-lactamases among Escherichia coli ST131 in Southeast Asia is driven by expansion of a single, locally prevalent subclone. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:13245. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49467-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fröding, I. et al. Extended-Spectrum-β-Lactamase- and Plasmid AmpC-Producing Escherichia coli Causing Community-Onset Bloodstream Infection: Association of Bacterial Clones and Virulence Genes with Septic Shock, Source of Infection, and Recurrence. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 64, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Decano AG, Downing T. An Escherichia coli ST131 pangenome atlas reveals population structure and evolution across 4,071 isolates. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:17394. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54004-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tchesnokova VL, et al. Pandemic uropathogenic fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli have enhanced ability to persist in the gut and cause bacteriuria in healthy women. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019;70:937–939. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biggel M, et al. Horizontally acquired papGII-containing pathogenicity islands underlie the emergence of invasive uropathogenic Escherichia coli lineages. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5968. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19714-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao Q, et al. Roles of iron acquisition systems in virulence of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli: salmochelin and aerobactin contribute more to virulence than heme in a chicken infection model. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:143. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galardini M, et al. Major role of iron uptake systems in the intrinsic extra-intestinal virulence of the genus Escherichia revealed by a genome-wide association study. PLOS Genet. 2020;16:e1009065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kallonen T, et al. Systematic longitudinal survey of invasive Escherichia coli in England demonstrates a stable population structure only transiently disturbed by the emergence of ST131. Genome Res. 2017;27:1437–1449. doi: 10.1101/gr.216606.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boll EJ, et al. Emergence of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli within the ST131 lineage as a cause of extraintestinal infections. MBio. 2020;11:1–13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00353-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ambite I, et al. Fimbriae reprogram host gene expression–Divergent effects of P and type 1 fimbriae. PLOS Pathog. 2019;15:e1007671. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denamur, E. et al. Genome wide association study of human bacteremia Escherichia coli isolates identifies genetic determinants for the portal of entry but not fatal outcome. medRxiv 1–20, 10.1101/2021.11.09.21266136 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Vihta K-D, et al. Trends over time in Escherichia coli bloodstream infections, urinary tract infections, and antibiotic susceptibilities in Oxfordshire, UK, 1998–2016: a study of electronic health records. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018;18:1138–1149. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30353-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abernethy J, et al. Epidemiology of Escherichia coli bacteraemia in England: results of an enhanced sentinel surveillance programme. J. Hosp. Infect. 2017;95:365–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Hout D, et al. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing and non-ESBL-producing Escherichia coli isolates causing bacteremia in the Netherlands (2014 – 2016) differ in clonal distribution, antimicrobial resistance gene and virulence gene content. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0227604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Royer G, et al. Phylogroup stability contrasts with high within sequence type complex dynamics of Escherichia coli bloodstream infection isolates over a 12-year period. Genome Med. 2021;13:77. doi: 10.1186/s13073-021-00892-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ingle DJ, Levine MM, Kotloff KL, Holt KE, Robins-Browne RM. Dynamics of antimicrobial resistance in intestinal Escherichia coli from children in community settings in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Nat. Microbiol. 2018;3:1063–1073. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0217-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaper JB, Nataro JP, Mobley HLT. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:123–140. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Decano AG, et al. Plasmids shape the diverse accessory resistomes of Escherichia coli ST131. Access Microbiol. 2021;3:acmi000179. doi: 10.1099/acmi.0.000179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welch RA, et al. Extensive mosaic structure revealed by the complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:17020–17024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252529799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson TJ, et al. Separate F-type plasmids have shaped the evolution of the H30 subclone of Escherichia coli sequence type 131. mSphere. 2016;1:1–15. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00121-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shropshire WC, et al. IS26-mediated amplification of blaOXA-1 and blaCTX-M-15 with concurrent outer membrane porin disruption associated with de novo carbapenem resistance in a recurrent bacteraemia cohort. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021;76:385–395. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewardson AJ, et al. Collateral damage from oral ciprofloxacin versus nitrofurantoin in outpatients with urinary tract infections: a culture-free analysis of gut microbiota. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015;21:344.e1–344.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spaulding CN, Klein RD, Schreiber HL, Janetka JW, Hultgren SJ. Precision antimicrobial therapeutics: the path of least resistance? npj Biofilms Microbiomes. 2018;4:4. doi: 10.1038/s41522-018-0048-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fibke CD, et al. Genomic epidemiology of major extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli lineages causing urinary tract infections in young women across Canada. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019;6:1–11. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McNally A, et al. Diversification of colonization factors in a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli lineage evolving under negative frequency-dependent selection. MBio. 2019;10:1–19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00644-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pitout JDD, Finn TJ. The evolutionary puzzle of Escherichia coli ST131. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020;81:104265. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ny S, Sandegren L, Salemi M, Giske CG. Genome and plasmid diversity of extended-spectrum β-Lactamase-producing Escherichia coli ST131 – tracking phylogenetic trajectories with Bayesian inference. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:10291. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46580-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goswami C, et al. Origin, maintenance and spread of antibiotic resistance genes within plasmids and chromosomes of bloodstream isolates of Escherichia coli. Microb. Genomics. 2020;6:e000353. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Messerer M, Fischer W, Schubert S. Investigation of horizontal gene transfer of pathogenicity islands in Escherichia coli using next-generation sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider G, et al. Mobilisation and remobilisation of a large archetypal pathogenicity island of uropathogenic Escherichia coli in vitro support the role of conjugation for horizontal transfer of genomic islands. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:210. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huguet KT, Rivard N, Garneau D, Palanee J, Burrus V. Replication of the Salmonella Genomic Island 1 (SGI1) triggered by helper IncC conjugative plasmids promotes incompatibility and plasmid loss. PLOS Genet. 2020;16:e1008965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pajand O, et al. Arrangements of mobile genetic elements among virotype E subpopulation of Escherichia coli sequence type 131 strains with high antimicrobial resistance and virulence gene content. mSphere. 2021;6:e0055021. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00550-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Phan M-D, et al. Plasmid-mediated ciprofloxacin resistance imparts a selective advantage on Escherichia coli ST131. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022;66:e0214621. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02146-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wyres KL, et al. Genomic surveillance for hypervirulence and multi-drug resistance in invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae from South and Southeast Asia. Genome Med. 2020;12:11. doi: 10.1186/s13073-019-0706-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Puyvelde S, et al. An African Salmonella Typhimurium ST313 sublineage with extensive drug-resistance and signatures of host adaptation. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:4280. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11844-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Copin R, et al. Sequential evolution of virulence and resistance during clonal spread of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:1745–1754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1814265116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou Z, Alikhan N, Mohamed K, Fan Y, Achtman M. The EnteroBase user’s guide, with case studies on Salmonella transmissions, Yersinia pestis phylogeny, and Escherichia core genomic diversity. Genome Res. 2020;30:138–152. doi: 10.1101/gr.251678.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seemann, T. mlst. https://github.com/tseemann/mlst.

- 45.Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parks DH, Imelfort M, Skennerton CT, Hugenholtz P, Tyson GW. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015;25:1043–1055. doi: 10.1101/gr.186072.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Treangen TJ, Ondov BD, Koren S, Phillippy AM. The Harvest suite for rapid core-genome alignment and visualization of thousands of intraspecific microbial genomes. Genome Biol. 2014;15:524. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0524-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie Z, Tang H. ISEScan: automated identification of insertion sequence elements in prokaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:3340–3347. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marçais G, et al. MUMmer4: A fast and versatile genome alignment system. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2018;14:e1005944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Croucher NJ, et al. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e15–e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nguyen L-T, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015;32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Page AJ, et al. SNP-sites: rapid efficient extraction of SNPs from multi-FASTA alignments. Microb. Genomics. 2016;2:e000056. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tonkin-Hill G, Lees JA, Bentley SD, Frost SDW, Corander J. Fast hierarchical Bayesian analysis of population structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:5539–5549. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zankari E, et al. PointFinder: a novel web tool for WGS-based detection of antimicrobial resistance associated with chromosomal point mutations in bacterial pathogens. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017;72:2764–2768. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seemann, T. Abricate. https://github.com/tseemann/abricate.

- 56.Zankari E, et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67:2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oksanen J, et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R. package version. 2020;2:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Csardi, G. & Nepusz, T. The igraph software package for complex network research. InterJournal, Complex Syst. (2006).

- 59.Biggel, M. EcVGDB. Zenodo10.5281/zenodo.4079473 (2020).

- 60.Jolley KA, Bray JE, Maiden MCJ. A RESTful application programming interface for the PubMLST molecular typing and genome databases. Database. 2017;2017:1–7. doi: 10.1093/database/bax060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carattoli A, et al. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using plasmidfinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3895–3903. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02412-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roer L, et al. Development of a web tool for Escherichia coli Subtyping Based on fimH Alleles. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017;55:2538–2543. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00737-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sullivan MJ, Petty NK, Beatson SA. Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1009–1010. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Katz L, et al. Mashtree: a rapid comparison of whole genome sequence files. J. Open Source Softw. 2019;4:1762. doi: 10.21105/joss.01762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Birgy, A. et al. Diversity and trends in population structure of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in febrile urinary tract infections in children in France from 2014 to 2017. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 96–105, 10.1093/jac/dkz423 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Harris PNA, et al. Whole genome analysis of cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli from bloodstream infections in Australia, New Zealand and Singapore: high prevalence of CMY-2 producers and ST131 carrying blaCTX-M-15 and blaCTX-M-27. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018;73:634–642. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kossow A, et al. High prevalence of MRSA and multi-resistant gram-negative bacteria in refugees admitted to the hospital—But no hint of transmission. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0198103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.MacFadden DR, et al. Comparing patient risk factor-, sequence type-, and resistance locus identification-based approaches for predicting antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli bloodstream infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019;57:1–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01780-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miles-Jay, A., Weissman, S. J., Adler, A. L., Baseman, J. G. & Zerr, D. M. Whole genome sequencing detects minimal clustering among Escherichia coli sequence type 131-H30 isolates collected from United States Children’s hospitals. J. Pediatric Infect. Dis. Soc. 1–5, 10.1093/jpids/piaa023 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Roer L, et al. WGS-based surveillance of third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli from bloodstream infections in Denmark. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017;72:1922–1929. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.de Lastours V, et al. Mortality in Escherichia coli bloodstream infections: antibiotic resistance still does not make it. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020;75:2334–2343. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kluytmans-van den Bergh MFQ, et al. Whole-genome multilocus sequence typing of extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016;54:2919–2927. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01648-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W256–W259. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

All genome assemblies were obtained from public databases. Accession numbers are listed in Supplementary Data 1 (main dataset) and Supplementary Data 3 (validation dataset). Source data for the main figures and calculations can be found in Supplementary Data 1, 2 and 3. All other data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.