Abstract

Two new polyaromatic hydrocarbon-degrading marine bacteria have been isolated from burrow wall sediments of benthic macrofauna by using enrichments on phenanthrene. Strain LC8 (from a polychaete) and strain M4-6 (from a mollusc) are aerobic and gram negative and require sodium chloride (>1%) for growth. Both strains can use 2- and 3-ring polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons as their sole carbon and energy sources, but they are nutritionally versatile. Physiological and phylogenetic analyses based on 16S ribosomal DNA sequences suggest that strain M4-6 belongs to the genus Cycloclasticus and represents a new species, Cycloclasticus spirillensus sp. nov. Strain LC8 appears to represent a new genus and species, Lutibacterium anuloederans gen. nov., sp. nov., within the Sphingomonadaceae. However, when inoculated into sediment slurries with or without exogenous phenanthrene, only L. anuloederans appeared to sustain a significant phenanthrene uptake potential throughout a 35-day incubation. In addition, only L. anuloederans appeared to enhance phenanthrene degradation in heavily contaminated sediment from Little Mystic Cove, Boston Harbor, Boston, Mass.

Most known bacterial polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) degraders have been isolated from heavily contaminated terrestrial environments (1, 4, 11, 33, 36). Various strains of Pseudomonas, Comamonas, Acinetobacter, and Sphingomonas have been obtained from such sources. However, PAH pollution is not constrained to sites impacted by fuel spills or locally high levels of fossil fuel use. PAHs occur ubiquitously, even in apparently pristine environments with relatively little fossil fuel use. Although there has been relatively little emphasis on such systems, the impact of long-term, chronic PAH exposure may be determined by assessing the presence and activity of nutritionally versatile bacteria that are also capable of degrading PAHs.

As is the case for terrestrial systems, marine environments include both heavily impacted sites and far more numerous sites exposed to low levels of PAH input. A variety of PAH degraders (mostly Pseudomonas and Vibrio spp.) have been isolated from polluted systems, including Boston Harbor, the Chesapeake Bay, and hydrocarbon-contaminated salt marshes (for examples, see references 6, 10, and 40). Several novel marine PAH degraders, e.g., Cycloclasticus spp. and Neptunomonas naphthovorans, have also been isolated from contaminated sediments (12, 15, 19). Some of these isolates occur in presumably pristine systems (14). The potentially ubiquitous distribution of marine PAH degraders suggests that the capacity for PAH degradation in polluted systems depends on the diversity and characteristics of naturally occurring populations and their responses to environmental conditions, rather than on the introduction of new taxa or selective modification of existing ones.

Although efficient and rapid PAH degradation generally depends on molecular oxygen availability (for examples, see references 8, 9, and 29), oxygen is often limited to the top several millimeters of surface sediment in marine systems (for an example, see reference 31), which severely constrains the potential for PAH degradation. However, the activities of benthic macrofauna, which physically mix sediments and introduce oxygen to subsurface sediments by burrow ventilation (2), may create unique sites for enhanced PAH degradation. This proposal is supported by patterns of PAH degradation in slurries of burrow sediment from different macrofaunas. When incubated under oxic conditions, these slurries exhibited enhanced PAH degradation potentials, relative to those of slurries of nonburrow sediment, for a number of compounds, including naphthalene, phenanthrene, acenaphthene, and dibenzothiophene (9). Similarly, the rhizosphere of marine plants enhances oxygen availability in sediments (20) and supports populations of aerobic PAH degraders (10).

Accordingly, we report here results of efforts to enrich, isolate, and characterize PAH degraders from macrofaunal burrow sediments. We describe the isolation of two aerobic, obligately marine PAH-degrading bacteria from burrows of a polychaete (Nereis virens) and a mollusc (Mya arenaria) in the intertidal mudflat of Lowes Cove, Maine. Both strains use naphthalene and phenanthrene aerobically as their sole carbon sources. 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) phylogenetic analysis and phenotypic characterization suggest that strain LC8 belongs to a new genus and species within the Sphinogmonadaceae that is provisionally designated Lutibacterium anuloederans LC8. Likewise, strain M4-6 is a new Cycloclasticus species, provisionally designated Cycloclasticus spirillensus M4-6. However, only LC8 appeared to maintain a significant PAH degradation potential after inoculation into contaminated and uncontaminated sediment slurries incubated with or without added phenanthrene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling and slurry preparation.

Animal burrow sediments were collected from the intertidal zone of Lowes Cove during the summer of 1999 with a sterile spatula during low tide. This site and the burrow sediment collection method have been described in detail previously (3, 17, 18, 23, 24). Based on PAH assays, the site is not known to be contaminated (PAH concentrations, <50 ng g [dry weight] of sediment−1). Samples collected were transferred to the laboratory within 1 h and processed immediately. Surface sediment (the top 1 to 3 mm) and bulk sediment (from a depth of 10 to 15 cm) were also collected and processed similarly. M. arenaria burrow sediments were collected after being exposed with a clam fork. Only the oxidized, light-brown layer (1 to 2 mm thick) was scraped off with a spatula. Burrow sediments of N. virens were collected similarly. In all cases, burrow identification was based on the presence of animals and distinctive burrow morphologies. Burrow sediment slurries were prepared with artificial seawater (37). Unless stated otherwise, 10% (wt/vol) slurries were used in the following experiments. For abiological controls, bulk sediments were autoclaved at 121°C and then cooled; this cycle was repeated three times over a period of 72 h.

Enrichment and isolation of phenanthrene-degrading bacteria.

Two hundred fifty milliliters of 10% sediment slurry was prepared in a 1-liter flask. A 2% phenanthrene stock solution was prepared in acetone and added to the slurry at an initial concentration of 10 ppm. Additional phenanthrene was added when the concentration of phenanthrene remaining in the slurry dipped below 0.5 ppm. The phenanthrene concentration in the slurry was slowly increased to about 100 ppm over a period of 2 weeks and was maintained at this level for the duration of the enrichment. After 4 weeks of enrichment, subsamples from the flasks were diluted serially with mineral salts medium ONR7a (12). Spread plates were prepared with ONR7a that had been solidified with 1.5% agar and sprayed with a 2% phenanthrene solution in acetone. The plates were incubated at room temperature (about 23°C) for up to 3 weeks. Colonies showing a clearing zone on the crystalline phenanthrene layer were picked and streaked on new minimal agar plates. A rapidly growing, visually distinct colony and a separate, morphologically unique isolate were selected for further analysis and purified by repeated plating.

Isolate characterization.

Cell motility was examined with motility agar and by phase-contrast microscopy at ×1,000 magnification. Routine microbiological tests, including those for Gram stain reaction, nitrate reduction, oxidase, catalase, gelatinase, lipase, phosphatase, and glucose fermentation, were performed according to standard methods (35). Sodium ion requirements were tested by replacing sodium salts in the medium with the corresponding potassium salts. Salinities were established by adjusting inorganic salt concentrations to final values of 3.5, 10, 35, and 70 ppt. Isolate growth was tested at temperatures between 4 and 42°C. Poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) inclusions were visualized with Sudan black. For bacteriochlorophyll detection, strain LC8 was grown to late log phase on pyruvate. The culture was centrifuged, washed twice with ONR7a, and collected by centrifugation at about 6,500 × g. The cell pellet was extracted by vortexing with 5 ml of an acetone-dimethyl sulfoxide mixture (9:1) for 2 min. The absorbance at 300 to 800 nm of the organic layer was measured with a Beckman model DU-600 spectrophotometer. The following compounds were tested at 15 to 20 mM as the sole carbon sources for growth of the isolates in ONR7a or ONR7a plus 0.05% yeast extract (ONR7y): arabinose, fructose, galactose, glucose, lactose, mannose, ribose, sucrose, alanine, aspartate, glycine, phenylalanine, proline, serine, valine, sodium citrate, sodium fumarate, gluconic acid, glucuronic acid, sodium glycolate, malic acid, sodium malonate, sodium acetate, sodium propionate, sodium pyruvate, sodium succinate, sodium tartarate, betaine, ethanol, glycerol, mannitol, and hexadecane. The following aromatics were also tested as the sole carbon sources for growth: phthalate, salicylate, biphenyl, naphthalene, 1,4-dimethyl naphthalene, 1,8-dimethyl naphthalene, acenaphthene, fluorene, anthracene, phenanthrene, dibenzothiophene, benz[a]anthracene, pyrene, chrysene, and fluoranthene. Isolate growth was scored as positive or negative by comparing the turbidity of the medium after 72 h of incubation at room temperature with shaking (120 rpm) to that of a control receiving no carbon source. Whole-cell fatty acid analyses were performed by Microbial ID, Inc. (Newark, Del.).

G+C contents were determined by a high-pressure liquid chromatographic method and with DNA that had been purified according to standard methods (21). Prior to analysis of G + C content, DNA was digested overnight with RNase to eliminate any interference from RNA contamination. After purification of DNA by precipitation in ethanol and resuspension in Tris-EDTA (10 mM Tris buffer, 1 mM EDTA), DNA subsamples were digested with S1 nuclease and alkaline phosphatase according to standard methods (21). The deoxynucleoside content of the digest was assayed with an isocratic mobile phase consisting of 30 mM ammonium phosphate in 8% methanol (pH 5.3) and a Supelcosil LC-18S column (15 by 4.6 mm; Supelco, Inc.) with detection by UV absorbance at a wavelength of 260 nm.

Cell morphology and flagellation were examined by standard electron microscopy methods (7, 38). In brief, early-log-phase cells grown on pyruvate (25 mM) in ONR7y (for strain LC8) or ONR7a (for strain M4-6) were centrifuged and washed with appropriate growth media. A drop of cell suspension was transferred to a Formvar- and carbon-coated copper grid and allowed to settle for 2 min. Excess liquid was blotted dry, and the preparation was stained with 1% uranyl acetate (38). Cells were viewed with a Philips model EM201 transmission electron microscope.

16S rDNA sequencing and phylogenetic analysis.

Total genomic DNA was extracted from 3 ml of late-log-phase phenanthrene-grown cells by a standard sodium dodecyl sulfate-proteinase K lysis procedure (32). The 16S rDNA gene was amplified by PCR with published primers (27f and 1492r) (41) in a 100-μl volume in accordance with standard protocols (28, 32). PCR products were separated in 0.8% agarose gels. DNA bands (1.5 kb) from the gel were excised and purified by using a Qiagen QIAquick gel extraction kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Both strands of the purified DNA were then sequenced by an automatic DNA sequencer (ABI) with published primers (the PCR primers mentioned above and internal primers 926f, 907r, 357f, and 519) (41).

The consensus sequences were submitted to GenBank for a BLASTN search. The search results were used as a guide for tree construction. Additional related 16S rDNA sequences identified from BLAST were retrieved from GenBank. Sequences were aligned by use of the Sequence Alignment and Modeling Software System (University of California, Santa Cruz) and ClustalW (European Bioinformatics Institute). The sequences were further edited manually to remove gaps and then were analyzed using computer-based phylogenetic packages. All phylogenetic inferences, including distance matrix calculation, maximum likelihood and maximum parsimony analyses, neighbor-joining analysis, and bootstrap data set generation, were performed with PHYLIP95, which included DNADIST.EXE, DNAML.EXE, DNAPARS.EXE, NEIGHBOR.EXE, and SEQBOOT.EXE. Tree construction was performed with TREEVIEW (WIN32) version 1.5.2 (30).

Phenanthrene uptake potential in slurries inoculated with strain LC8 or strain M4-6.

Slurries of Lowes Cove sediment were prepared as described above. Additional slurries were prepared with sediment from Little Mystic Channel (LMC), a heavily contaminated site in Boston Harbor that contains substantial concentrations of a variety of PAHs (34, 39). LMC sediment was collected at low tide with acrylic cores (7 cm [diameter] by 32 cm) that were transported to the Darling Marine Center within 8 h of collection. The cores were stored under flowing seawater until use (about 7 days), at which time the top 15-cm section was removed and diluted with artificial seawater (1:10, vol/vol), as for Lowes Cove slurries. Abiological controls for Lowes Cove and LMC sediments were prepared from slurries autoclaved three times at intervals over 72 h.

Slurries were incubated with added strain LC8 or strain M4-6, with or without exogenous phenanthrene. Treatments with exogenous phenanthrene were established with initial additions of 10 μg cm of slurry−3 from a solution of 2% phenanthrene in acetone; phenanthrene concentrations were maintained at these levels by additions at intervals as necessary. Slurries without added bacterial cultures or with autoclaved sediment were established as controls.

The inocula for the slurries were grown in ONR7a with pyruvate as a carbon source and about 100 μg of phenanthrene liter−1 for inducing PAH degradation. Bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation after they reached stationary phase. The pellets were washed and resuspended in artificial seawater, and portions were transferred to triplicate samples of Lowes Cove or LMC slurry (500 ml) in 1-liter Erlenmeyer flasks fitted with a rubber stopper and a glass-wool-filled tube to facilitate air exchange. The final added bacterial concentrations were 108 cells cm of slurry−3, as estimated by plate counts of the inocula. The slurries were incubated in the dark at room temperature (about 22°C) with shaking (∼110 rpm).

Phenanthrene uptake potentials were assayed at intervals by transferring 25-ml samples from each of the slurries to sterile 60-ml serum bottles. Phenanthrene (250 μg) was added to the bottles (from 2% phenanthrene in acetone), which were then sealed with Teflon-lined stoppers. Phenanthrene uptake potentials were measured by removing 4-ml subsamples at intervals for analysis of phenanthrene content (see below). Changes in phenanthrene uptake potentials over time in the primary slurry flasks were used as an index of the extent to which added strain LC8 or strain M4-6 could stimulate and sustain phenanthrene degradation. Uptake rates in flasks with added cultures were compared to uptake rates for slurries with neither exogenous phenanthrene nor cultures and to those for autoclaved slurries.

PAH and PAH metabolite analysis.

Loss of PAHs from culture media and slurries was measured by gas chromatography-mass selective detection after organic solvent extraction. In brief, slurries or cultures were acidified to a pH of <2.0 with 5 N HCl and were mixed with one-half volume of n-hexane in a Teflon-lined screw-cap tube. The tubes were shaken for 2 min, and aqueous and organic phases were separated by centrifugation at ∼2,400 × g. The organic layer was concentrated under a stream of nitrogen, and PAHs were reconstituted in n-hexane. Samples were assayed with a Hewlett-Packard model 6890 gas chromatograph together with a model 5972A mass selective detector equipped with an HP-5MS capillary column (30 m by 0.25 mm by 0.25 μm [film thickness]) and helium as a carrier gas.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The 16S rDNA sequence of strains LC8 and M4-6 have been deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers AY026916 and AY026915, respectively.

RESULTS

Enrichment culture and strain isolation.

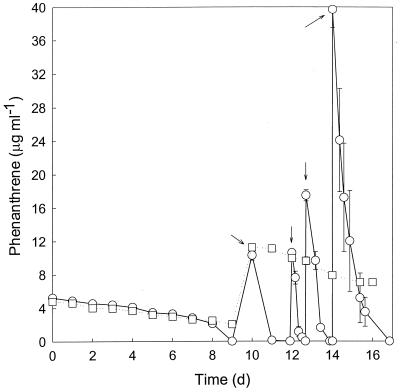

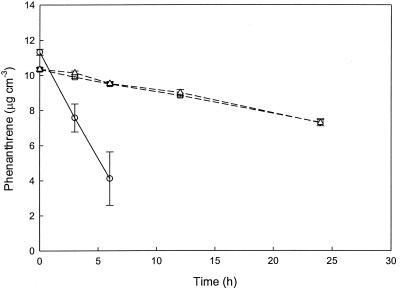

Macrofaunal burrow sediment slurries degraded substantial amounts of phenanthrene after a 2-week incubation (Fig. 1). Phenanthrene degradation rates of 15 μg ml−1 day−1 after 2 weeks were typical for an enrichment flask with N. virens sediment. Degradation was preceded by a lag period of about 8 days. Comparable results were obtained for slurries of M. arenaria burrow sediments (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Time course of phenanthrene loss in N. virens burrow sediment slurries (○) and bulk surface sediment slurries (□). Arrows indicate the addition of phenanthrene. All data are means of results for triplicate determinations; error bars represent ±1 standard error.

After slurry subsamples were plated, a small number of colonies showed clearing zones on phenanthrene crystals. Pure cultures of the PAH degraders were obtained after four to five transfers. Isolate LC8 (a distinctly pigmented colony from N. virens sediment) and strain M4-6 (a morphologically unique culture from M. arenaria burrow sediment) were chosen for further studies.

Isolate characteristics.

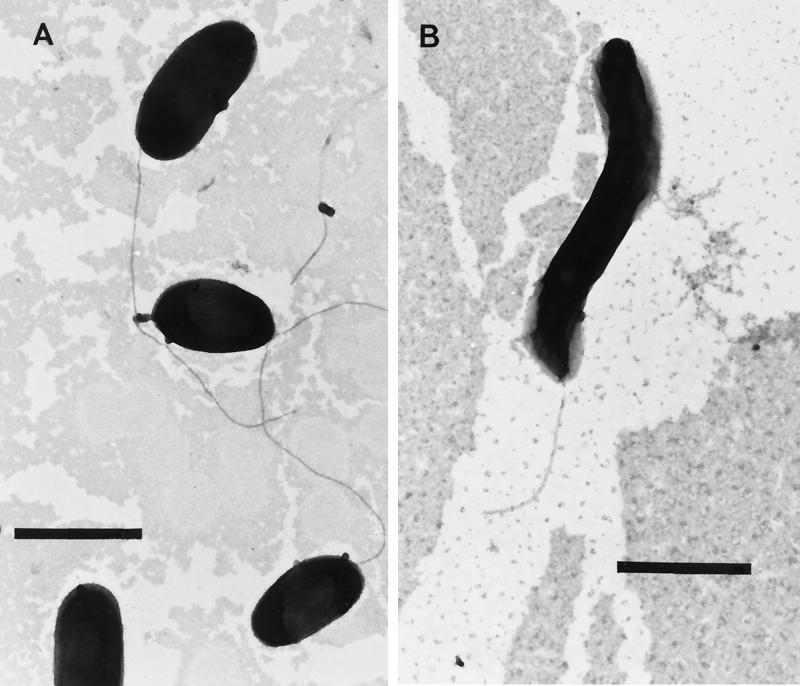

Both strain LC8 and strain M4-6 were aerobic and obligately marine, requiring sodium chloride for growth. Both isolates tolerated salinities of up to 70 ppt. Phenotypic assays established that strain LC8 was a gram-negative, catalase-positive, oxidase-positive, nonmotile rod of ∼0.5 by 1.5 to 2.0 μm (Fig. 2A) that formed pale-yellow colonies on minimal agar plates with phenanthrene as a carbon source. It also reduced nitrate and exhibited phosphatase activity but did not hydrolyze gelatin, show lipase activity, ferment glucose, or accumulate PHB. Strain LC8 grew between 15 and 30°C. Acetone-dimethyl sulfoxide (9:1) extracts of strain LC8 revealed none of the absorption maxima between 600 and 800 nm that are characteristic of bacteriochlorophylls. Strain LC8 used the following compounds as its sole carbon sources in ONR7y: arabinose, fructose, galactose, glucose, mannose, ribose, sucrose, citrate, fumurate, glucuronic acid, gluconic acid, acetate, pyruvate, tartarate, glycerol, mannitol, and hexadecane. Strain LC8 also utilized naphthalene and phenanthrene as its sole carbon and energy sources, transformed dibenzothiophene to dibenzothiophene sulfoxide, and cometabolized pyrene in the presence of phenanthrene (data not shown). Strain LC8 produced 1-hydroxynaphthoic acid transiently from phenanthrene, produced dibenzothiophene sulfoxide from dibenzothiophene, and produced pyrene-diol and pyrene dicarboxylic acid as pyrene metabolites (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Transmission electron micrographs of strain LC8 (A) and strain M4–6 (B) at ×15,500 magnification. Scale bars indicate 1 μm.

Whole-cell fatty acid analysis revealed that the major fatty acid was C18:1ω7c (56.7%). Other significant constituents were C16:1ω7c (17.2%), C16:0 (6.4%), and C17:1ω7c (3.0%). G+C contents were 53.5% ± 1.8% (mean ± standard error).

Strain M4-6 was a gram-negative, catalase-positive, oxidase-positive, phosphatase-positive, motile spirillum of ∼0.5 by 1.5 to 2.0 μm (Fig. 2B). It fermented glucose, accumulated PHB, and grew between 15 and 37°C, but it was negative for gelatinase and lipase activity. Strain M4-6 used the following compounds as its sole carbon sources in ONR7a: arabinose, fructose, galactose, glucose, mannose, ribose, citrate, fumarate, glucuronic acid, gluconic acid, malonate, acetate, propionate, pyruvate, and mannitol. M4-6 also utilized naphthalene and phenanthrene as its carbon and energy sources but neither transformed dibenzothiophene nor cometabolized pyrene. Strain M4-6 produced 1-hydroxynaphthoic acid transiently from phenanthrene (data not shown).

Whole-cell fatty acid analysis revealed three major fatty acids in strain M4-6: C15:0 iso (33.5%), C15:0 anteiso (12.4%), and C16:1ω7c (12.2%). G + C contents were 46.3% ± 0.2%.

Phylogenetic analysis.

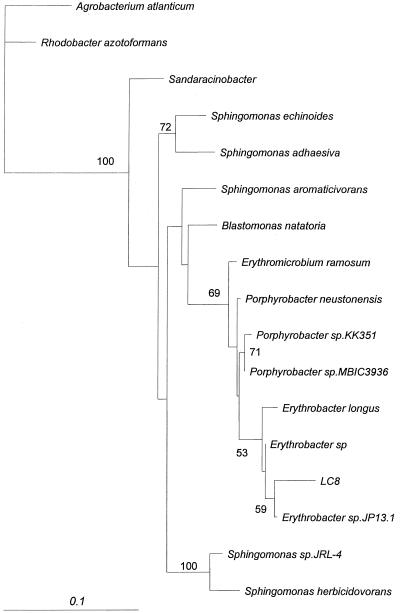

PCR amplification of 16S rDNA from strains LC8 and M4-6 resulted in sequences of 1,452 and 1,496 bp, respectively. Based on a BLASTN search of GenBank, the closest matches to strain LC8 were Erythrobacter spp. (nucleotide identity, 96.7%), Erythromicrobium spp. (nucleotide identity, 94.8%), Porphyrobacter spp. (nucleotide identity, 94.9%), and Sphingomonas spp. (nucleotide identity, 92.0%). These and other related sequences were used to construct a consensus tree based on maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis (100 bootstrap samples). The results indicated that strain LC8 was phylogenetically closest to Erythrobacter with an Erythrobacter-LC8 branch (supported at a level of 95% by bootstrap analysis) that is distinct from those of other sphingomonads (Fig. 3). Porphyrobacter and Erythromicrobium formed another clade distinct from the Erythrobacter-LC8 branch and those of the rest of the sphingomonads. The trees generated from the maximum parsimony and neighbor-joining methods shared the overall topography of the maximum likelihood tree and presented the same relationship among strain LC8, Erythrobacter spp., and the sphingomonads (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic tree based on maximum likelihood analysis of 16S rDNA gene sequences of strain LC8 and selected representatives of the Sphingomonadaceae and α-Proteobacteria. Numbers indicate the present bootstrap support for 100 resamplings of the data set.

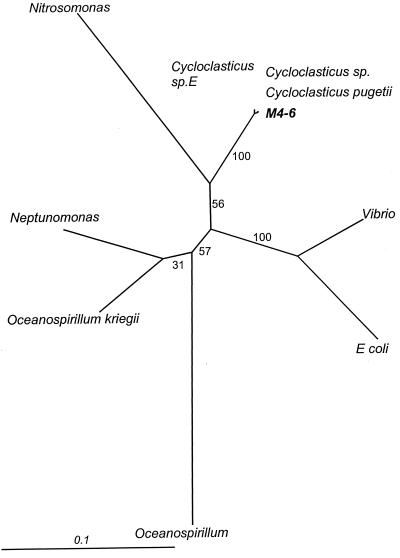

A similar analysis of strain M4-6 16S rDNA sequence data revealed a very high nucleotide identity with Cycloclasticus sp. strain E (99.7%) as well as with several other Cycloclasticus species. The results strongly suggested that strain M4-6 belongs to the genus Cycloclasticus. An unrooted consensus tree constructed on the basis of a 100-subsample bootstrapped maximum likelihood analysis revealed that strain M4-6 and all of the selected Cycloclasticus species were in the same close cluster, a finding supported at 100% by bootstrap analysis (Fig. 4). Results from maximum parsimony and neighbor-joining methods were equivalent (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic tree based on maximum likelihood analysis of 16S rDNA gene sequences of strain M4–6 and selected representatives of Cycloclasticus and the γ-Proteobacteria. Numbers indicate the percentages of bootstrap support for 100 resamplings of the data set.

Phenanthrene uptake in slurries.

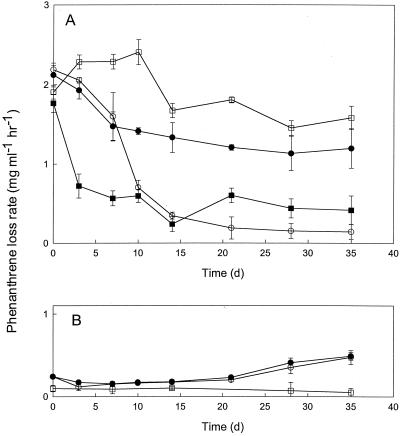

Phenanthrene uptake by slurry samples amended with strain LC8 was readily detected by using time course assays with added phenanthrene (Fig. 5). Uptake rates in autoclaved slurries and uninoculated slurries were negligible compared to rates for inoculated slurries incubated continuously with phenanthrene (Fig. 6). Essentially equivalent results were obtained for uninoculated and autoclaved slurries from Lowes Cove and LMC (data not shown). However, uptake rates for inoculated slurries varied over a 35-day interval depending on the sediment source and treatment (Fig. 6A and 7).

FIG. 5.

Time course of phenanthrene concentrations in slurries of autoclaved Lowes Cove sediment (□), slurries containing no added strain LC8 (▵), and slurries incubated routinely with phenanthrene and inoculated with strain LC8 (○). All data are means of results for triplicate determinations; error bars represent ±1 standard error.

FIG. 6.

(A) Potential phenanthrene uptake rates for slurries from Lowes Cove (circles) and LMC (squares) inoculated with strain LC8 and incubated with (open symbols) or without (closed symbols) routine phenanthrene additions. All data are means of results for triplicate determinations; error bars represent ±1 standard error. (B) Potential phenanthrene uptake rates for uninoculated slurries from Lowes Cove incubated with (○) or without (●) routine phenanthrene additions and for autoclaved slurries (□). All data are means of results for triplicate determinations; error bars represent ±1 standard error.

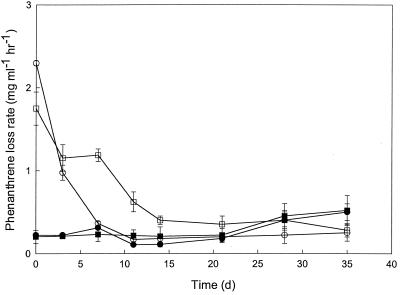

FIG. 7.

Potential phenanthrene uptake rates for slurries from Lowes Cove (circles) and LMC (squares) inoculated with strain M4–6 and incubated with (open symbols) or without (closed symbols) routine phenanthrene additions. All data are means of results for triplicate determinations; error bars represent ±1 standard error.

In treatments containing strain LC8, uptake rates remained relatively high for Lowes Cove slurries with exogenous phenanthrene and for LMC slurries without added phenanthrene; rates for these two treatments were comparable for much of the incubation period (Fig. 6A). Rates decreased sharply over time (>90%) for the remaining treatments with strain LC8 (Fig. 6A). In contrast, phenanthrene uptake declined rapidly for all Lowes Cove treatments with strain M4-6 and was initially low and remained so for all LMC treatments (Fig. 7). In accordance with these results, phenanthrene concentrations declined much more dramatically for strain LC8 treatments (phenanthrene loss, >98% in 7 days) than for strain M4-6 treatments of LMC slurries containing only the initial background phenanthrene burden (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Residual phenanthrene remaining in LMC sediment slurries incubated without routine phenanthrene additions and inoculated with strain LC8 (●) or strain M4–6 (■). Results for autoclaved control slurries (○) are shown, as well. All data are means of results for triplicate determinations; error bars represent ±1 standard error.

DISCUSSION

Macrofaunal burrows enhance a number of microbial activities. For example, elevated levels of nitrification (26, 27) and sulfate reduction (18) have been documented for macrofaunal burrow sediments. Burrows also support higher levels of microbial biomass than do bulk sediments (17, 23). In addition, previous studies have shown that N. virens and M. arenaria burrow sediments harbor PAH-degrading bacteria and that degradation rates for added PAHs are greater in burrow sediments than in nonburrow sediments (9). Since Lowes Cove has not been significantly contaminated with PAHs, it appears that burrows provide an environment suitable for maintenance of PAH-degrading organisms of certain taxa. Accordingly, burrows in uncontaminated systems may provide a source of organisms that can respond to chronic or acute PAH pollution and perhaps serve as a resource for neighboring heavily contaminated systems.

Two distinct PAH degraders were isolated from Lowes Cove burrow sediments. Morphologically, phylogenetically, and phenotypically, strain LC8 appears to be a sphingomonad (Fig. 2 and 3). Many Sphingomonas spp. have been reported to degrade a variety of PAHs, which is not surprising, since most of these isolates have been obtained from contaminated terrestrial systems (for examples, see references 1, 5, 11, 22, and 36); a marine Sphingomonas sp. capable of degrading PAH has likewise been isolated from a contaminated site (16).

Nonetheless, 16S rDNA sequence analysis indicates that strain LC8 is most similar to the genus Erythrobacter (nucleotide sequence identity, 96.7%), with Erythromicrobium (sequence identity, 94.8%) and Porphyrobacter (sequence identity, 94.9%) being the next closest relatives. In addition, maximum likelihood analysis places strain LC8 and Erythrobacter on the same phylogenetic branch, distinct from the Erythromicrobium-Porphyrobacter branch as well as from that of the sphingomonads. However, the possibility that strain LC8 belongs to the genus Erythrobacter, Erythromicrobium, or Porphyrobacter is remote, since strain LC8 does not appear to contain photosynthetic pigments, while all Erythrobacter, Erythromicrobium, and Porphyrobacter spp. do (13, 42, 43). Thus, strain LC8 appears to be a new genus within the family Sphingomonadaceae (25), for which we provisionally assign the name Lutibacterium anuloederans LC8.

BLASTN search results and phylogenetic analysis of strain M4-6 16S rDNA sequence data conclusively establish it as a member of the genus Cycloclasticus. Maximum likelihood analysis shows that strain M4-6 forms a very tight cluster with all of the Cycloclasticus species analyzed. However, none of the previously reported Cycloclasticus species has a spirillum morphology, which suggests that strain M4-6 is a novel Cycloclasticus species. Strain M4-6 is further differentiated from extant Cycloclasticus species by a number of phenotypic traits (Table 1). For example, Dyksterhouse et al. (12) describe several Cycloclasticus strains from Puget Sound, all of which were short rods. Cycloclasticus pugetii reduces nitrate to nitrite, has lipase activity, and lacks PHB accumulation, while strain M4-6 shows no nitrate reduction or lipase activity but accumulates PHB (Table 1). Thus, we propose the new species, C. spirillensus M4-6.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of phenotypic characteristics of strain M4–6 with those of C. pugetiia and N. naphthovoransb

| Trait | Strain M4–6 | C. pugetii | N. naphthovorans |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell morphology | Spirillum | Bacillus | Bacillus |

| Cell size, length by diam (μm) | 1.5 to 2.0 by 0.5 | 1.0 to 2.0 by 0.5 | 2.0 to 3.0 by 0.7 to 0.9 |

| Colony morphology | White, round, translucent | Small, round, unpigmented | NDc |

| PHB accumulation | + | − | + |

| Reduction of NO3 to NO2 | − | + | − |

| Lipase activity | − | + | − |

| Phosphatase activity | + | ND | + |

| Fermentation of carbohydrates | + | ND | + |

| Salinity tolerance (ppt) | 10–70 | 10–70 | ND |

| Growth temp (°C) | 15–37 | 4–28 | 4–30 |

| G+C (mol%) | 46.3 ± 0.2 | 37–38 | ND |

The genus Cycloclasticus has been isolated from a variety of uncontaminated and PAH-polluted sites, and its ability to degrade PAHs has been well documented in cultures (12, 14, 15). However, C. spirillensus M4-6 did not substantially enhance or sustain phenanthrene uptake when it was added to slurries from Lowes Cove or Boston Harbor (LMC) that were prepared with or without exogenous phenanthrene (Fig. 6 and 7). Qualitative observations of the distinctive spirillum morphology in slurries with added C. spirillensus M4-6, but not in unamended slurries, indicate that the rapid decrease in phenanthrene uptake for C. spirillensus M4-6 treatments is likely not due to cell loss alone. Loss of uptake over time in Lowes Cove slurries with added phenanthrene and in LMC slurries with elevated background PAH levels also indicates that the continuous presence or absence of PAHs likely had little impact on C. spirillensus M4-6. At present, the factors that control phenanthrene uptake potential by C. spirillensus M4-6 remain uncertain. Nonetheless, results from this study suggest that C. spirillensus M4-6 may not be a particularly effective PAH degrader in situ.

Relative to uninoculated slurries, inoculation of Lowes Cove and LMC slurries with L. anuloederans LC8 significantly enhances and sustains the phenanthrene uptake of treatments both with and without periodic phenanthrene addition (Fig. 6 and 8). Lower uptake rates over time for Lowes Cove slurries without periodic phenanthrene addition may reflect decreased expression of the dioxygenase(s) that initiates phenanthrene degradation, since uptake rates were higher and more stable for slurries with periodic phenanthrene addition (Fig. 6). In contrast, lower uptake rates over time in LMC slurries with periodic phenanthrene additions may reflect inhibition due to desorption of toxic PAHs or other organics by phenanthrene.

In summary, burrows of marine macrofauna in uncontaminated sediments exhibit enhanced PAH degradation rates (9) and harbor novel PAH-degrading bacteria. Based on responses of burrow isolates to reinoculation in contaminated and uncontaminated sediments, L. anuloederans LC8 (from a polychaete burrow) appears somewhat better suited for PAH degradation than does C. spirillensus M4-6 (isolated from a mollusc burrow).

Description of Lutibacterium anuloederans LC8 gen. nov., sp. nov.

Lutibacterium anuloederans LC8 gen. nov., sp. nov. (lu.ti.bac′ teri.um. L. n. lutum, mud; M. L. Lutibacterium, the mud bacterium; an′ ulo.eder.ans. L. n. anulus, ring; L. v. ederans, to eat; M.L. anuloederans, ring-eating). Gram-negative, nonmotile, short rod with a single polar flagellum. Aerobic. Requires sodium ion for growth. Catalase and oxidase positive. PAHs, including naphthalene and phenanthrene, are used as sole or principal carbon sources for growth. In addition, strains utilize selected organic acids and amino acids, including citrate, acetate, pyruvate, and phenylalanine. Nitrate is reduced to nitrite. Colonies are small, round, opaque, and entire, with yellow pigmentation. The principal fatty acids in whole cells are C18:1ω7c, C16:ω7c, and C16:0.

Description of Cycloclasticus spirillensus M4-6, sp. nov.

Cycloclasticus spirillensus M4-6, sp. nov. (spi.ril.len′ sus. L. adj. spirillum, of or pertaining to a spiral). Gram-negative, motile spirillum with a single polar flagellum. 1.5 to 2.0 by 0.5 μm. Aerobic. Requires sodium ion for growth. Catalase and oxidase positive. PAHs, including naphthalene and phenanthrene, are used as sole or principal carbon sources for growth. In addition, strains utilize selected organic acids and amino acids, including citrate, acetate, pyruvate, alanine, and proline. Nitrate is not reduced to nitrite. Colonies are small, round, translucent, and entire, with no pigmentation. The principal fatty acids in whole cells are C15:0 iso, C15:0 anteiso, and C16:ω7c.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported in part by funds from the Office of Naval Research (N00014-96-1-0592).

Footnotes

Contribution 368 from the Darling Marine Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aitken M D, Stringfellow W T, Nagel R D, Kazunga C, Chen S H. Characteristics of phenanthrene-degrading bacteria isolated from soils contaminated with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Can J Microbiol. 1998;44:743–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aller R C. Benthic fauna and biogeochemical processes in marine sediments: the role of burrow structures. In: Blackburn T H, Sorensen J, editors. Nitrogen cycling in coastal marine environments. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1988. pp. 301–338. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson F E, Black L, Watling L E, Mook W, Mayer L M. A temporal and spatial study of mudflat erosion and deposition. J Sediment Petrol. 1981;51:729–736. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashok B T, Saxena S, Musarrat J. Isolation and characterization of four polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon degrading bacteria from soil near an oil refinery. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1995;21:246–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1995.tb01052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balkwill D L, Drake G R, Reeves R H, Fredrickson J K, White D C, Ringelberg D B, Chandler D P, Romine M F, Kennedy D W, Spadoni C M. Taxonomic study of aromatic-degrading bacteria from deep-terrestrial-subsurface sediments and description of Sphingomonas aromaticivorans sp. nov., Sphingomonas subterranea sp. nov., and Sphingomonas stygia sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:191–201. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-1-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berardesco G, Dyhrman S, Gallagher E, Shiaris M P. Spatial and temporal variation of phenanthrene-degrading bacteria in intertidal sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2560–2565. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.7.2560-2565.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bozzola J J, Russell L D. Electron microscopy: principles and techniques for biologists. 2nd ed. Sudbury, Mass: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 1998. pp. 121–147. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cerniglia C E. Biodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Biodegradation. 1992;3:351–368. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung W K, King G M. Biogeochemical transformations and potential polyaromatic hydrocarbon degradation in macrofaunal burrow sediments. Aquat Microb Ecol. 1999;19:285–295. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daane L L, Harjono I, Zylstra G J, Häggblom M M. Isolation and characterization of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria associated with the rhizosphere of salt marsh plants. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:2683–2691. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.6.2683-2691.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dagher F, Deziel E, Lirette P, Paquette G, Bisaillon J G, Villemur R. Comparative study of five polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon degrading bacterial strains isolated from contaminated soils. Can J Microbiol. 1997;43:368–377. doi: 10.1139/m97-051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dyksterhouse S E, Gray J P, Herwig R P, Lara J C, Staley J T. Cycloclasticus pugetii gen. nov., sp. nov., an aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading bacterium from marine sediments. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:116–123. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-1-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuerst J A, Hawkins J A, Holmes A, Sly L I, Moore C J, Stackebrandt E. Porphyrobacter neustonensis gen. nov., sp. nov., an aerobic bacteriochlorophyll-synthesizing budding bacterium from fresh water. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:125–134. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-1-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geiselbrecht A D, Hedlund B P, Tichi M A, Staley J T. Isolation of marine polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH)-degrading Cycloclasticus strains from the Gulf of Mexico and comparison of their PAH degradation ability with that of Puget Sound Cycloclasticus strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4703–4710. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.12.4703-4710.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geiselbrecht A D, Herwig R P, Deming J W, Staley J T. Enumeration and phylogenetic analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading marine bacteria from Puget Sound sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3344–3349. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.9.3344-3349.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilewicz M, Ni'matuzahroh, Nadalig T, Budzinski H, Doumenq P, Michotey V, Bertrand J C. Isolation and characterization of a marine bacterium capable of utilizing 2-methylphenanthrene. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;48:528–533. doi: 10.1007/s002530051091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giray C, King G M. Effect of naturally-occurring bromophenols on sulfate reduction and ammonia oxidation in sediments from a Maine mudflat. Aquat Microb Ecol. 1997;13:295–301. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen K, King G M, Kristensen E. Impact of the soft-shell clam Mya arenaria on sulfate reduction in an intertidal sediment. Aquat Microb Ecol. 1996;10:181–194. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hedlund B P, Geiselbrecht A D, Bair T J, Staley J T. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon degradation by a new marine bacterium, Neptunomonas naphthovorans gen. nov., sp. nov. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:251–259. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.1.251-259.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howes B L, Teal J M. Oxygen loss from Spartina roots and its relationship to salt marsh oxygen balance. Oecologia. 1994;97:431–438. doi: 10.1007/BF00325879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson J L. Similarity analysis of DNAs. In: Gerhardt P, Murray R G E, Wood W A, Krieg N R, editors. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 655–682. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan A A, Wang R F, Cao W W, Franklin W, Cerniglia C E. Reclassification of a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-metabolizing bacterium, Beijerinckia sp. strain B1, as Sphingomonas yanoikuyae by fatty acid analysis, protein pattern analysis, DNA-DNA hybridization, and 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:466–479. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-2-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King G M. Dehalogenation in marine sediments containing natural sources of halophenols. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:3079–3085. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.12.3079-3085.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King G M, Klug M J, Lovley D R. Metabolism of acetate, methanol, and methylated amines in intertidal sediments of Lowes Cove, Maine. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;45:1848–1853. doi: 10.1128/aem.45.6.1848-1853.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kosako Y, Yabuuchi E, Naka T, Fujiwara N, Kobayashi K. Proposal of Sphingomonadaceae fam. nov., consisting of Sphingomonas Yabuuchi et al. 1990, Erythrobacter Shiba and Shimidu 1982, Erythromicrobium Yurkov et al. 1994, Porphyrobacter Fuerst et al. 1993, Zymomonas Kluyver and van Niel 1936, and Sandaracinobacter Yurkov et al. 1997, with the type genus Sphingomonas Yabuuchi et al. 1990. Microbiol Immunol. 2000;44:563–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2000.tb02535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kristensen E. Benthic fauna and biogeochemical processes in marine sediments: microbial activities and fluxes. In: Blackburn T H, Sorensen J, editors. Nitrogen cycling in coastal marine environments. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1988. pp. 275–299. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kristensen E, Jensen M H, Andersen T K. The impact of polychaete (Nereis virens Sars) burrows on nitrification and nitrate reduction in estuarine sediments. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 1985;85:75–91. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lane D J. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1991. pp. 115–175. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leahy J G, Olsen R H. Kinetics of toluene degradation by toluene-oxidizing bacteria as a function of oxygen concentration, and the effect of nitrate. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;23:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Page R D M. TREEVIEW: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:357–358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rasmussen H, Jorgensen B B. Microelectrode studies of seasonal oxygen uptake in a coastal sediment: role of molecular diffusion. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1992;81:289–303. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneider J, Grosser R, Jayasimhulu K, Xue W, Warshawsky D. Degradation of pyrene, benz[a]anthracene, and benzo[a]pyrene by Mycobacterium sp. strain RJGII-135, isolated from a former coal gasification site. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:13–19. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.13-19.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shiaris M P, Jambard-Sweet D. Distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surficial sediments of Boston Harbor, Massachusetts, USA. Mar Pollut Bull. 1986;17:469–472. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smibert R M, Krieg N R. Phenotypic characterization. In: Gerhardt P, Murray R G E, Wood W A, Krieg N R, editors. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 607–654. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stringfellow W T, Aitken M D. Comparative physiology of phenanthrene degradation by two dissimilar pseudomonads isolated from a cresote-contaminated soil. Can J Microbiol. 1994;40:423–438. doi: 10.1139/m94-071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sverdrup H U, Johnson M W, Fleming R H. The oceans: their physics, chemistry, and general biology. New York, N.Y: Prentice-Hall, Inc.; 1942. pp. 165–227. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Bruggen E F J, Wiebenger E H, Gruber M. Negative-staining electron microscopy of proteins at pH values below their isoelectric points. Its application to hemocyanin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1960;42:171–172. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voparil I M, Mayer L M. Dissolution of sedimentary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons into the lugworm's (Arenicola marina) digestive fluids. Environ Sci Technol. 2000;34:1221–1228. [Google Scholar]

- 40.West P A, Okpokwasili G C, Brayton P R, Grimes D J, Colwell R R. Numerical taxonomy of phenanthrene-degrading bacteria isolated from Chesapeake Bay. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1984;48:988–993. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.5.988-993.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilmotte A, Van der Auwera G, De Wachter R. Structure of the 16S ribosomal RNA of the thermophilic cyanobacterium Chlorogloeopsis HTF (‘Mastigocladus laminosus HTF’) strain PCC7518, and phylogenetic analysis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;317:96–100. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81499-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yurkov V, Stackebrandt E, Holmes A, Fuerst J A, Hugenholtz P, Golecki J, Gad'on N, Gorlenko V M, Kompantseva E I, Drews G. Phylogenetic positions of novel aerobic, bacteriochlorophyll a-containing bacteria and description of Roseococcus thiosulfatophilus gen. nov., sp. nov., Erythromicrobium ramosum gen. nov., sp. nov., and Erythrobacter litoralis sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:427–434. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-3-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yurkov V V, Beatty J T. Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:695–724. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.695-724.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]