Abstract

Objective

Proper exercise immediately after breast cancer surgery (BCS) may prevent unnecessary physical and psychological decline resulting from the surgery; however, patients’ attitude, barriers and facilitators for exercise during this period have not been studied. Hence, this study aims to explore the barriers and facilitators of exercise among patients with breast cancer through multiple interviews immediately after surgery through 4 weeks after BCS.

Methods

We conducted three in-depth interviews of 33 patients with breast cancer within 1 month after BCS.

Results

We identified 44 themes, 10 codes and 5 categories from interview results. Physical constraints and psychological resistance were identified as the barriers to exercise, while a sense of purpose and first-hand exercise experience were identified as the facilitators of exercise. By conducting the interviews over the course of 4 weeks after surgery, we monitored patterns of changes in barriers and facilitators over time. Overall, our analyses identified that professional intervention based on the time since surgery and the physical state after BCS is essential. The intervention would counteract the overwhelming psychological resistance in the early weeks by developing a sense of purpose in the later weeks.

Conclusions

We made suggestions for future research and exercise intervention programmes that can benefit breast cancer survivors based on the categories, codes and themes identified in this study.

Keywords: SPORTS MEDICINE, MENTAL HEALTH, ONCOLOGY, Breast surgery, QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The participants were recruited immediately after the breast cancer surgery and shared their experiences regarding multiple factors.

To examine the effect of time, multiple interviews were conducted from immediately after surgery up to 1 month after surgery.

This study was conducted at the tertiary hospital in South Korea and generalisation of the findings from the current study to other regions and countries should be made careful.

Background

The incidence of breast cancer has been continually increasing. Currently, breast cancer is the most common cancer among women, accounting for 24.2% of the cases worldwide and 20.3% of the cases in South Korea.1 Although the 5-year survival rate of breast cancer is over 90% for stages 0–2 patients with breast cancer in South Korea, a substantial number of patients with breast cancer experience breast cancer recurrence and suffer heavily from side effects of cancer treatments.2 Although the rate of breast-conserving surgery has increased from 37.6% in 2002 to 67.4% in 2017, many patients with breast cancer develop both short-term and long-term physical impairments such as lymphoedema, decreased shoulder strength and range of motion (ROM).3–6 In addition to physical impairment, the prevalence of depression, distress, anger and social isolation is high among breast cancer survivors.7

Exercise and physical activity (PA) improves the prognosis of breast cancer (eg, decrease breast cancer-specific and all-cause mortality).8 The benefit of exercise among patients with breast cancer is not limited to improvement in survival. Early implementation of exercises has been shown to reduce surgery-related complications,9 pain10 and risk of lymphoedema.11 Exercises such as shoulder ROM exercise and isometric and passive stretching shortly after surgery could improve shoulder ROM during the early recovery after surgery.12

Although ample evidence exists on the benefits of exercise on recovery after breast cancer surgery (BCS),13 patients with breast cancer are reluctant to participate in exercise during early recovery. Furthermore, a few studies have investigated the attitude towards exercise and exercise experience, barriers, and facilitators over an extended period of time, particularly immediately after BCS until 4 weeks after surgery. A few qualitative studies have investigated these factors in cancer survivors after a few months of surgery.14–16 Considering the various different needs of the breast cancer survivors depending on the time postsurgery, more information on the barriers and facilitators of exercise immediately after BCS can potentially be useful in tailoring exercise intervention programmes to the specific needs of breast cancer survivors.

In these regards, this study investigated the factors related to exercise promotion within 1 month after BCS. More specifically, by employing the in-depth interview method, the study investigated: (1) the barriers and the facilitators of exercise for breast cancer survivors; (2) the changes in these factors according to time after BCS. In addition, this study aimed to complement the intentions expressed in the interviews with the actual behaviours based on the quantitative data on PA.

Methods

Participants

We recruited 33 women who underwent BCS at the breast cancer centre of a university medical centre in Seoul, Korea, between 14 February 2019 and 12 November 2019, using the criterion sampling technique.17 Patients who were over 70 years old, had undergone bilateral or reconstruction surgery or had a history of previous cancer were excluded. The recruitment of new participants was stopped when new data from additional participants did not add new ideas or concepts related to the purpose of the study.18

Procedures

Potential participants who met all the inclusion criteria were contacted by the physician to explain the research participation opportunity. Patients who agreed to participate in multiple interviews after BCS signed the informed consent. The same procedure was repeated until the saturation point.17 Three of 36 participants withdrew (1 patient dropped out because of resurgery and the other 2 refused to participate); thus, 33 patients participated in this study.

The research participants met with the first author of the current study 1 day before BCS, to build a collaborative relationship between the researcher and the participant. After BCS, the interview was conducted three times during clinic visits: first interview within 2 weeks after surgery; second interview between 2 and 3 weeks after surgery; and third interview between 3 weeks and 1 month after surgery. All interviews were conducted one-on-one in Korean. With the participants’ permission, the interviews were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim, with two different semistructured interview questionnaires (table 1). Only after all the three interviews were completed, a professional exercise consultation was provided as a compensation for research participation, not as a component of this study.

Table 1.

Interview questionnaires

| Interview | Questions |

| First |

|

| Second and third |

|

| Third |

|

The complementary measurement of the participants’ PA level was performed during each interview using the Global PA Questionnaire (GPAQ), developed by the WHO.19 The GPAQ comprises 16 items in 4 domains of PA: work, leisure time, transportation and sedentary behaviour. The reliability and validity of the Korean version of the GPAQ were examined in a previous study.20 We added a measure of walking and its frequency and duration, which is not included in the original GPAQ but is relevant to this study.

Trustworthiness

To increase the trustworthiness of data,21 we have employed three different methods: reflective note, observation and member check. After each interview, the exercise specialist reflected on their performance as an interviewer. Mistakes and important lessons learnt were recorded in a reflective note, and methods to improve the quality of future interviews were practised before the next interview. A sufficient amount of time was spent observing participants’ physical performance and symptoms, including shoulder ROM, strength, pain and other medical treatment. To increase the reliability of the findings, interviews were conducted three times over 4 weeks as participants underwent treatment. The transcript and summary of each interview were confirmed by the participants to ensure the transcriptions and summaries correctly reflected what they intended to express.

Analysis

Guided by the grounded theory,22 the team started with open coding, identifying the themes that emerged from the transcripts. In addition, the field notes were included in the analysis to avoid loss of non-verbal information. Immediately after the team agreed on the first group of themes collectively, the authors worked on the subsequent transcripts individually. The team conducted regular meetings and worked on abstracting the codes and then the categories to proceed to the selective coding collectively. During the constant comparative analysis, member checking was performed to increase the validity of the analysis. The analysis results were sent to three randomly selected interviewees to confirm the meaning and nuance of answers, and thereby, their experience as breast cancer survivors.

Complementary quantitative data analysis was performed using a repeated measures analysis of variance to compare the means of total PA total and walk, before surgery and during the first, second and third interview. To determine whether total PA and walk time is different from baseline presurgery levels, paired t-test was used.

Patient and public involvement

The research team developed the research question grounded on the previous experiences with people who underwent BCS. The understanding led the research team to employing qualitative approach with multiple in-depth interviews for an extended period of time. By adopting member-checking process, the team ensured the involvement of the participants in the analysis stage as well. The publication of this research will help disseminate the results to the public.

Results

Participant description

The characteristics of the 33 participants are presented in table 2. Characteristics such as age, weight, surgery type, cancer stage, dominant arm, operation side, postoperative day (from 1 to 30 days) and whether they had neoadjuvant chemotherapy were analysed.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the participants

| ID | Age range (years) | Type of surgery | Cancer stage |

| 1 | 60–64 | TM/SLNB | 1A |

| 2 | 55–59 | TM/SLNB | 0 |

| 3 | 50–54 | TM/SLNB | 2A |

| 4 | 35–39 | TM/ALND | 3A |

| 5 | 55–59 | TM/ALND | 1A |

| 6 | 55–59 | TM/ALND | 2B |

| 7 | 65–69 | PM/SLNB | 1A |

| 8 | 50–54 | PM/SLNB | 1A |

| 9 | 40–44 | PM/SLNB | 1A |

| 10 | 45–49 | PM/ALND | 2A |

| 11 | 50–54 | PM/ALND | 1A |

| 12 | 55–59 | PM/ALND | 0 |

| 13 | 60–64 | PM/SLNB | 0 |

| 14 | 65–69 | PM/SLNB | 1A |

| 15 | 60–64 | PM/SLNB | 1A |

| 16 | 45–49 | PM/SLNB | 1A |

| 17 | 35–39 | PM/SLNB | 0 |

| 18 | 60–64 | PM/SLNB | 1A |

| 19 | 60–64 | PM/ALND | 1B |

| 20 | 55–59 | TM/SLNB | 1A |

| 21 | 65–69 | TM/SLNB | 1A |

| 22 | 50–54 | TM/SLNB | 1A |

| 23 | 65–69 | TM/SLNB | 0 |

| 24 | 60–64 | TM/SLNB | 1A |

| 25 | 40–44 | TM/SLNB | 0 |

| 26 | 60–64 | TM/ALND | 1A |

| 27 | 65–69 | TM/SLNB | 1A |

| 28 | 50–54 | PM/ALND | 2A |

| 29 | 60–64 | PM/ALND | 3A |

| 30 | 55–59 | TM/SLNB | 1A |

| 31 | 55–59 | TM/ALND | 2B |

| 32 | 35–39 | PM/ALND | 2A |

| 33 | 40–44 | PM/SLNB | 1A |

ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; N, no; PM, partial mastectomy; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy; TM, total mastectomy; Y, yes.

Intervention needed in time for physical recovery

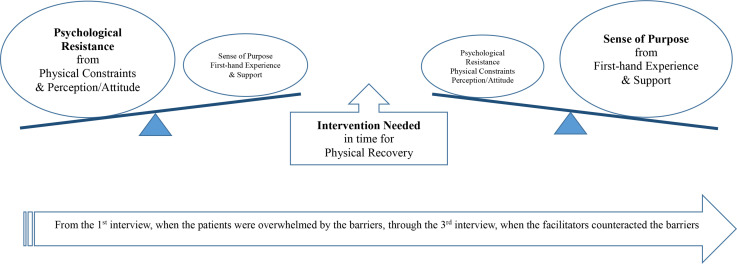

The interviewees identified multiple factors that either facilitated participants to exercise more or hindered them from exercising after BCS. Out of the 44 themes that emerged from the interviews, 10 codes and 5 categories were identified (table 3). Physical constraints and psychological resistance were identified as the barriers for exercise, whereas the sense of purpose and first-hand exercise experience were identified as the facilitators for exercise during the early stage of rehabilitation after BCS. The overwhelming physical constraints that produced psychological resistance in the earlier weeks after surgery appeared to be gradually substituted by the sense of purpose that derived from the first-hand experience encouraged by diverse sources. This conclusion is consistent with the PA data: the motivation to perform exercise and PA materialised with time (table 4). Quantitative data of 31 participants were collected and analysed with repeated measure analysis of variance, which revealed that the total PA level statistically significantly increased over time (F=3.64, p<0.05). The supportive intervention that reflects an individual patient’s physical condition can expedite the substitution process, if conducted properly. Our analyses revealed the core variable that answered our research questions was ‘intervention needed in time for physical recovery’ to meet the varying needs of the survivors according to the time after BCS (figure 1).

Table 3.

Themes, codes, and categories from the interviews

| Categories | Codes | Themes |

| Physical constraints | Postoperative syndrome | Lymphoedema, seroma |

| Pain | ||

| Limited mobility of the arm | ||

| Feeling weak | ||

| Operation-derived condition | Drain | |

| Non-operation-derived condition | Neoadjuvant therapy | |

| Pre-existing physical condition | ||

| Psychological resistance | Perception and attitude | Believing that daily living activities are sufficient |

| Unaware of the requirement of exercise | ||

| Exercise not prioritised | ||

| Not wanting to burden the body | ||

| Lack of self-efficacy regarding exercise | ||

| Psychological withdrawal | ||

| Concerns from the lack of accurate information | Concerns regarding the potential side-effects of exercise | |

| Concerns regarding injuries | ||

| Concerns regarding the timing being inappropriate | ||

| Concerns regarding the aetiology and symptoms of the cancer – related to exercise | ||

| Own theory regarding the aetiology and the symptoms of the cancer – related to exercise | ||

| Sense of purpose | Encouragement and support | From family |

| From medical professionals | ||

| From exercise therapists | ||

| From other patients with cancer | ||

| From media | ||

| Expected benefits | Speed up the recovery | |

| Recover from the postoperative syndrome | ||

| Health management | ||

| Muscular strength | ||

| Increase muscle mass | ||

| Improve flexibility | ||

| Prevent relapse by promoting health | ||

| General physical health | ||

| Break unhealthy lifestyle | ||

| Prevent weight gain | ||

| Maintain healthy lifestyle | ||

| First-hand experience | Benefits of exercise | Reduced pain |

| Promoted flexibility | ||

| Increased amount of exercise | ||

| Increased physical activities | ||

| Reduced discomforts | ||

| Expedited recovery | ||

| Heightened sense of purpose | Attribution of cancer to the lack of exercise | |

| Want to exercise more | ||

| Intervention needed | Accurate information and education | Want consultation regarding symptoms |

| Want information/education in accordance with the proper timing |

Table 4.

The change of physical activity level (presurgery to 4 weeks postsurgery)

| Before surgery M (SD) | First interview M (SD) | Second interview M (SD) | Third interview M (SD) | P for time | |

| VPA (min/week) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| MPA (min/week) | 41.0 (113.4) | 0 | 0 | 12.3 (54.1) | 0.07 |

| Total PA (min/week) | 142.6 (167.6) | 49.8 (61.6)* | 96.1 (175.4) | 142.6 (161.9) | 0.02 |

| Walk (min/week) | 204.4 (208.0) | 142.1 (165.3) | 173.1 (139.1) | 222.9 (166.4) | 0.1 |

Total physical activity = (minutes of MVPA at week) + (minutes of leisure-time MVPA) + (minutes of transportation PA).

*P<0.05 vs baseline total PA.

MPA, moderate physical activity; M (SD), mean (SD); NA, not available; PA, physical activity; VPA, vigorous physical activity.

Figure 1.

Relations among categories according to time, which changes the weight of the barriers and facilitators of exercise.

Barriers to exercise

Physical constraints: Patients with breast cancer who underwent surgery experienced multiple types of physical restraints, which made it difficult for them to participate in or even think about exercise. The most frequently reported barrier to exercise was pain, followed by limited shoulder ROM, and frequent by-products of the treatment including seroma and the drain attached to the body. All these contributed to a perception of weakness throughout the body, especially among those who received neo-adjuvant chemotherapy.

I couldn’t exercise after the surgery. I am not eating well and do not feel strong. It’s not just my arm that feels weak; my whole body feels weak. I lay inert or just sat leaning on something, most of the time. (Participant #19, PM/ALND, first interview)

(After the drain was removed) This (seroma) started leaking and I felt so distressed. It stressed me out. Only a few drops, you know, when it leaks, are enough to feel so awkward. Thinking about it, I couldn’t exercise. This past week was more uncomfortable. (Participant #19, PM/ALND, third interview)

Psychological resistance: These physical constraints discouraged participants from exercising because they believed that ‘PAs may be harmful or at least drain their energy.’ Moreover, although their physical condition permitted exercise, participants did not feel enough motivation to exercise. In some cases, anxiety regarding possible injuries overcame their wish to become more physically active. Other times, they excused themselves from doing more exercise as ‘daily living and house chores are good enough exercise.’ In addition to these concerns and excuses, their pre-existing perception of the inefficacy of exercise appeared to discourage them from exercising after surgery.

Well, I didn’t do much. I couldn’t exercise at all because of the pain. The armpit feels tight and poking. What if moving causes more pain? Worried about it, I can’t exercise. (Participant #27, TM/SLNB, third interview)

I couldn’t exercise… Well, I thought of looking over the booklet (of exercise education), but didn’t. I don’t recall why I didn’t, but time passed while I was taking care of my grandkids. I put it on the dining table and didn’t reach for it later. I did try stretching my arm lying down on the bed. It wasn’t painful though. (Participant #13, PM/SLNB, first interview)

Notwithstanding, the lack of accurate information was identified as a significant reason for the patients not take courage to exercise. After surgery, considering all the byproducts of operation, whether anticipated or unanticipated, patients’ anxiety was not ungrounded. Accurate information regarding the types of activities and exercises that speed up the recovery from diverse postoperative symptoms was important.

Well, I can’t find the information I need… when should I work on muscles, when can I jog or run… I don’t know. (Participant #33, PM/SLNB, first interview)

Often, different health professionals such as surgeons, medical oncologists, physiatrists and plastic surgeon (in case patients underwent breast reconstruction) provided varying information on when and how to exercise. Lack of information or inconsistent information was the barrier to exercise for patients with breast cancer.

Facilitators of exercise

Accurate information: Accurate information on exercise according to the time after surgery was identified as the key facilitator to promote exercise among patients. The patients expressed their wish to have some professional consultation regarding exercise interventions that take their symptoms and health conditions into account.

Encouragement and support: In the process of recovery after BCS, patients reported social support as an important factor that motivated them to exercise more. Diverse sources worked, including medical professionals, exercise therapists, friends, family members, as well as fellow patients with cancer.

(Other patients in this rehab center says) You have to exercise. Otherwise, it’ll become stiff. Those who have experienced something like myself informed me to do this and that, even regarding how to wash up. It’s a great help from these folks who have been or are going through the similar experiences (treatment processes)… It’s good. (Participant #28, PM/ALND, third interview)

First-hand experience: The participants reported their first-hand experience as an important motivator for exercise. They increased the activity level and exercised more after knowing the positive effects of exercise through experience.

The more I exercise, the larger this angle becomes. It was really hard to follow the instructions when I wasn’t working out. The more I tried, however, the easier it became. So I realized the importance (of exercise). If I do not exercise, it will be harder. So whenever it pops up in my mind, I try to do some exercise. Even in waking up, I tried to do some arm stretching. (Participant #24, TS/SLNB, second interview)

Sense of purpose: All the aforementioned factors contributed to the patients’ sense of purpose, expecting the benefits of exercise. The expectation included pain reduction, fast recovery, relapse prevention and health management. The patients who had mastectomy tried to motivate themselves to exercise more. In addition, they frequently expressed their wish to increase physical strength, muscle mass and flexibility, as well as to maintain a healthy lifestyle.

(People say) It takes 3 months to recover from the surgery, but recovery is up to me, I figure. Exercising and building muscles are up to me. So I do exercise. (Participants #2, TM/SLNB, third interview)

I think I got cancer because I had not exercised… There’s no other reason. You know, there’s no known cause for the triple negative breast cancer… I guess it’s from me not exercising… So I do exercise now, do walking at least.” (Participant #9, PM /SLNB, second interview)

Impact of timing

During this study, the participants showed a certain pattern related to the time after BCS. Diverse factors contributed to the heightened psychological resistance, resulting in no or minimal exercise, in the early weeks after BCS. However, with the time and support of professional and social contacts, the patients expressed an increased sense of the purpose of exercise. Support from external sources, as well as own first-hand experience, produced this sense of purpose. The motivation along with proper instruction of tailored exercise intervention is projected to offset the psychological resistance in the early weeks after BCS (figure 1). This pattern is consistent with the participants’ actual amount of PA participation, which increased gradually from immediately after surgery to 4 weeks after surgery (table 4).

Discussion

Summary of results

We employed an in-depth interview technique among breast cancer survivors within 1 month after BCS and identified the key barriers and facilitators of exercise. Physical constraints that were prominent in the early weeks, as reported in the literature,23 24 along with the pre-existing perception and attitude toward exercise developed psychological resistance to exercise among the patients. However, an increase in motivation to exercise was observed among patients in later weeks due to more encouragement from others, as was reported in other studies,25–27 and higher sense of purpose from their own experience.

This process of increasing the sense of purpose, replacing the psychological resistance, seemed to be propelled by professional intervention conducted at the right time with the correct exercise. All participants agreed that more accurate information and education were required to promote exercise. Multiple physical, psychological and environmental circumstances served as conditions for psychological resistance among patients. The resistance grounded on the anxiety and fear of unintended injuries and unanticipated side effects as a cancer survivor can only be overcome through professional diagnosis and exercise prescription. The complementary PA data revealed that patients’ sense of purpose was positively associated with their actual amount of PA participation, reinforcing the requirement for professional intervention at the right time.

Study limitations and strengths

This qualitative study included only 33 participants. Hence, generalisation of the results to all breast cancer survivors should be made with caution. Considering that the recruiting site was one of the major tertiary hospitals in Korea, the lived experiences of people living in rural areas or those treated in smaller hospitals, for instance, could not be captured in the current study. Therefore, to advance our understanding regarding the professional intervention that was identified as the key factor to promote exercise among the participants, a randomised control study should be performed. The long-term and short-term physical as well as psychological benefits of exercise can be examined more comprehensibly by investigating the effects of exercise intervention, preferably in a longitudinal study.

The strengths of this study included repeated interviews over 4 weeks after surgery which enabled us to observe the change in patients’ attitude towards exercise over time. Especially, in this study, patients with breast cancer were interviewed from only 1 week after surgery before implementation of exercise or rehabilitation intervention; however, recent studies have reported the importance of early exercise intervention after surgery in patients with cancer.

Clinical implications

To mitigate the constant feedback loop between physical and psychological excuses, a tailored exercise intervention, considering patients physical and psychological conditions, should be designed. Considering the diverse anxiety expressed in the current study, tailored programmes should consider each patient’s physical and psychological needs to optimise the potential effects of the programme.

Many patients with breast cancer do not participate in PA and experience significant muscle mass loss during the first few months after surgery, which is associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes and worse prognosis, including increased risk of recurrence.28 29 The findings of this study revealed that patients with breast cancer can benefit from early participation of exercise and PA, which may prevent loss of shoulder ROM and strength after BCS. Therefore, the importance of exercise needs to be emphasised and educated, not only among the patients but also among the healthcare professionals so that their recommendations to the patients can have real impact in changing motivation as well as behaviour. In addition, this study provides information regarding the attitude of patients with breast cancer towards exercise during the early recovery stage after surgery and thus, promotes the development of appropriate intervention strategies.

Conclusions

Thirty-three breast cancer survivors shared their experience and thoughts regarding exercise after BCS. Commonly expressed needs of the participants were summed as a professional intervention that takes into account the time after surgery and each individual’s physical condition. Exercise was not only a matter of motivation and will power, but also a matter of resources that can be used with physical and psychological comfort.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SY and JYJ participated in study design. SY, JM, JK, SIIK and JYJ participated in data collection. SY, AJ, JM, JB, JK, SP, SIIK and JYJ participated in data analysis and interpretation. AJ, SY, CL, YJY, JH and JYJ participated in the manuscript writing. All authors participated in the manuscript review and revision. All authors thank participants of the study and research coordinators at the Yonsei Cancer Center. SIIK and JYJ are responsible for the overall contents as the quarantors.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea grant number NRF-2017S1A5A2A01024689, NRF-2021S1A5B5A16077404, the National R&D Programme for Cancer Control, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (HA21C0067000021) and the Yonsei Signature Research Cluster Programme 2021-22-0009.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Data are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital (IRB No. 4-2018-1094). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Cancer.go.kr [homepage on the internet] . National cancer information center: Ministry of health and welfare. Available: https://www.cancer.go.kr/ [Accessed 9 Jan 2021].

- 2.Hong S, Won Y-J, Park YR, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2017. Cancer Res Treat 2020;52:335–50. 10.4143/crt.2020.206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nccn.org [homepage on the internet] . National comprehensive cancer network. Available: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf [Accessed 08 Jun 2021].

- 4.Ebaugh D, Spinelli B, Schmitz KH. Shoulder impairments and their association with symptomatic rotator cuff disease in breast cancer survivors. Med Hypotheses 2011;77:481–7. 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alves Nogueira Fabro E, Bergmann A, do Amaral E Silva B, Fabro EAN, BdA eS, et al. Post-Mastectomy pain syndrome: incidence and risks. Breast 2012;21:321–5. 10.1016/j.breast.2012.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayes SC, Johansson K, Stout NL, et al. Upper-body morbidity after breast cancer: incidence and evidence for evaluation, prevention, and management within a prospective surveillance model of care. Cancer 2012;118:2237–49. 10.1002/cncr.27467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golden-Kreutz DM, Andersen BL. Depressive symptoms after breast cancer surgery: relationships with global, cancer-related, and life event stress. Psychooncology 2004;13:211–20. 10.1002/pon.736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spei M-E, Samoli E, Bravi F, et al. Physical activity in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis on overall and breast cancer survival. Breast 2019;44:144–52. 10.1016/j.breast.2019.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ten Wolde B, Kuiper M, de Wilt JHW, Strobbe LJ, et al. Postoperative complications after breast cancer surgery are not related to age. Ann Surg Oncol 2017;24:1861–7. 10.1245/s10434-016-5726-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sagen A, Kaaresen R, Sandvik L, et al. Upper limb physical function and adverse effects after breast cancer surgery: a prospective 2.5-year follow-up study and preoperative measures. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014;95:875–81. 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torres Lacomba M, Yuste Sánchez MJ, Zapico Goñi A, Lacomba MT, Sánchez MJY, ÁZ G, et al. Effectiveness of early physiotherapy to prevent lymphoedema after surgery for breast cancer: randomised, single blinded, clinical trial. BMJ 2010;340:b5396. 10.1136/bmj.b5396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cinar N, Seckin U, Keskin D, et al. The effectiveness of early rehabilitation in patients with modified radical mastectomy. Cancer Nurs 2008;31:160–5. 10.1097/01.NCC.0000305696.12873.0e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Möller UO, Beck I, Rydén L. A comprehensive approach to rehabilitation interventions following breast cancer treatment-a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Cancer 2019;19:1–20. 10.1186/s12885-019-5648-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrade RD, Junior GJF, Capistrano R, et al. Constraints to leisure-time physical activity among Brazilian workers. Annals of Leisure Research 2019;22:202–14. 10.1080/11745398.2017.1416486 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Payán DD, Sloane DC, Illum J, et al. Intrapersonal and environmental barriers to physical activity among blacks and Latinos. J Nutr Educ Behav 2019;51:478–85. 10.1016/j.jneb.2018.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Son JS, Chen G, Liechty T, et al. The role of facilitators in the constraint negotiation of leisure-time physical activity. Leisure Sciences 2021;65:1–20. 10.1080/01490400.2021.1919253 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. SAGE Publications, Inc, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field methods 2006;18:59–82. 10.1177/1525822X05279903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armstrong T, Bull F. Development of the world Health organization global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ). J Public Health 2006;14:66–70. 10.1007/s10389-006-0024-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee J, Lee C, Min J, et al. Development of the Korean global physical activity questionnaire: reliability and validity study. Glob Health Promot 2020;27:44–55. 10.1177/1757975919854301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lincoln YS, Guba EG, Pilotta JJ. Naturalistic inquiry 9. Sage, 1985: 438–9. 10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing Grounded theory. Sage Publications, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shamley D, Srinaganathan R, Oskrochi R, et al. Three-Dimensional scapulothoracic motion following treatment for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;118:315–22. 10.1007/s10549-008-0240-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baron RH, Kelvin JF, Bookbinder M, et al. Patients' sensations after breast cancer surgery. a pilot study. Cancer Pract 2000;8:215–22. 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2000.85005.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abe M, Iwase T, Takeuchi T, et al. A randomized controlled trial on the prevention of seroma after partial or total mastectomy and axillary lymph node dissection. Breast Cancer 1998;5:67–9. 10.1007/BF02967417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gillis C, Li C, Lee L, et al. Prehabilitation versus rehabilitation: a randomized control trial in patients undergoing colorectal resection for cancer. Anesthesiology 2014;121:937–47. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones LW, Courneya KS, Fairey AS, et al. Effects of an oncologist's recommendation to exercise on self-reported exercise behavior in newly diagnosed breast cancer survivors: a single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med 2004;28:105–13. 10.1207/s15324796abm2802_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan K, Chlebowski RT, Mortimer JE, et al. Insulin resistance and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women in the women's health Initiative. Cancer 2020;126:3638–47. 10.1002/cncr.33002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caan BJ, Cespedes Feliciano EM, Prado CM, et al. Association of muscle and adiposity measured by computed tomography with survival in patients with nonmetastatic breast cancer. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:798–804. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Data are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.