Abstract

We present a case of a 7-day-old male infant with severe respiratory disease requiring venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy with evidence of lymphangiectasia on lung biopsy. Differentiating primary versus secondary lymphangiectasis in this patient remains a riddle despite extensive investigations including an infective screen, lung biopsy and whole-genome sequencing. In addition to the standard therapies used in paediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome, such as lung-protective ventilation, permissive hypoxaemia and hypercarbia, nursing in the prone position, early use of muscle relaxants, rescue intravenous corticosteroids and broad-spectrum antibiotics, the patient was also given octreotide despite the absence of a chylothorax based on the theoretical benefit of altering the lymphatic flow. His case raises an interesting discussion around the role of lymphatics in the pathophysiology of paediatric and adult respiratory distress syndrome and prompts the exploration of novel agents which may affect lymphatic vessels used as an adjunctive therapy.

Keywords: Paediatric intensive care, Paediatrics, Respiratory medicine

Background

Paediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome (pARDS) is a heterogeneous disease that can pose a diagnostic challenge due to the wide range of differential diagnoses for the underlying cause. Clinicians, with the aid of prompt investigations, aim to find the underlying pathology and direct treatment. Obtaining a focused differential diagnosis is a time critical process in the context of a profoundly sick infant exposed to ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI). Presentations in the neonatal period or early infancy prompt the consideration of an underlying congenital or genetic cause. Pulmonary lymphangiectasis (at times termed pulmonary lymphangiectasia) (PL) is a known condition associated with poor prognosis, especially in neonates.1 2 Treatment includes respiratory and nutritional support, drainage of chylous effusions, fluid and electrolyte balance, maintenance of coagulation and immune function. However, research exploring the use of novel therapies that alter lymphatic flow, such as somatostatins, is lacking in this group of patients. In addition, the role of lymphatics and the impact of altered lymphatic flow in the pathophysiology of pARDS or adult ARDS is also limited. pARDS comprises 3%–10% of paediatric intensive care admissions based on the paediatric acute lung injury consensus conference (PALICC) definition.3 4 Although mortality rates are lower than in adult ARDS, it is still sizeable at 17% with a higher mortality rate in moderate to severe cases as well as an overall mortality rate of up to 51% in low-income countries.4 5 Differential diagnoses causing pARDS can be categorised into congenital or genetic conditions, pulmonary and extrapulmonary causes. Common causes are infections/sepsis, burns and near-drownings.4 PL is a rare disease with the precise incidence unknown. It harbours a particularly poor prognosis in the neonatal period.2 Historically, the terminology and classification of PL has caused confusion and undergone several changes. The most recent classification suggests primary PL results from congenital defects in lung development and typically presents in the neonatal period. The secondary group comprise conditions such as obstructive congenital heart disease, venous clot formation (increased venous pressure) or other causes interrupting effective lymphatic drainage.6

The mainstay of treatment for PL is respiratory and nutritional support with drainage of chylous effusions if present. The treatment of pARDS is also largely supportive and current guidelines are available from the PALICC. Octreotide is a synthetic analogue of somatostatin that is longer acting. Indication of use include conditions in both paediatric and adult medicine.7 8 Octreotide has been used to treat chylothorax post paediatric cardiac surgery.9 10 Although octreotide has been used to treat congenital disorders of lymphatics,11 12 there is a paucity in the literature on the use of octreotide in these conditions without the presence of chylous collection (eg, chylothorax or chylous ascites). Many adjunctive therapies have been explored in the management of pARDS, but none targeted pulmonary lymphatic flows.13

Case presentation

We present a infant male born at term to non-consanguineous parents of Greek descent. There was maternal history of herpes simplex virus 1 infection with no active lesions leading up to the delivery. Maternal screening was negative for gestational diabetes and low vaginal swab was negative for group B Streptococcus. The infant was born in good condition with a birth weight of 4.4 kg. The liquor was clear with no evidence suggestive of possible meconium aspiration. The mother received intravenous antibiotics for postpartum fevers due to retained placenta and was discharged home 5 days post partum. The patient was well and thriving leading up to his presentation.

On day 7 of age, the infant became increasingly lethargic with reduced feeding and intermittent grunting. Parents called the ambulance who transferred the patient to the paediatric emergency department (ED). There was no history of possible inhalation injury.

In ED, the patient was noted to be afebrile, haemodynamically stable, with an initial resting respiratory rate of 40–50 breaths per minute (bpm) and intermittent tachypnoea up to 80 bpm was reported. Over 2 hours, he became persistently tachypnoeic up to 100 bpm associated with desaturations down to 80% and persistant grunting. The patient’s respiratory status rapidly deteriorated and required escalation in respiratory support to continuous positive airway pressure of 8 cm with 50% fraction of inspired oxygen and was subsequently transferred to the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

The patient’s respiratory distress worsened over 6 hours in PICU and the decision was made to intubate him electively. Ventilation proved difficult from the beginning with evidence of significantly reduced lung compliance needing high peak pressures to generate small tidal volumes. A chest X-ray confirmed the endotracheal tube was in a good position and no pleural effusion, collapse or consolidation to account for the restrictive pattern seen on the ventilator. The first arterial blood gas postintubation demonstrated a profound respiratory acidosis with pH 6.97, pCO2 117 mm Hg, pO2 54 mm Hg, HCO3 26.3 mmol/L and a lactate 0.8 mmol/L. Saturations were in the mid 80s in 100% oxygen. Due to the hypoxia, the positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) was increased to 8 cm and inhaled nitric oxide was started at 20 ppm, these two actions seemed to improve the oxygenation, achieving saturations in the low 90s in 70% oxygen but the respiratory acidosis persisted. During acute desaturation events, he was rescued using an anaesthetic t-piece. A manometer revealed that adequate rise and fall of the chest was achieved with PIP of 60 cm H2O. Despite all efforts to reduce VILI through a trial of different ventilation modes (volume control, pressure control and high-frequency oscillatory ventilation), the lung parenchyma’s properties continued to deteriorate, suggesting a dynamic process. The oxygenation index reached 24 within 5 hours following intubation and a persistent respiratory acidosis, pH of less than 7.00 and pCO2 greater than 100, led to the decision to initiate extracorporeal support as a bridge to diagnosis and to limit further iatrogenic harm to the lungs. No appropriate sized V-V cannulae were available, so he was centrally cannulated onto venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA ECMO).

Investigations

The patient’s initial venous gas in the ED showed a mild metabolic acidosis with pH 7.31, CO2 45 mm Hg, bicarbonate of 22.2 mmol/L and lactate of 2.2 mmol/L. He had a raised white cell count (WCC) of 30.6×109/L with neutrophilia of 24.4×109/L but a normal C reactive protein (CRP) at 3.6 mg/L. Subsequent CRP rose to 14.5 mg/L on day 2 of admission with an elevated procalcitonin of 1.3 ng/mL. His initial chest X-ray was unremarkable (see tables 1 and 2) and COVID-19 swab was negative. Maternal placenta was not sent for further testing and hence we do not have microbiology or histopathology information on the placenta.

Table 1.

Timeline of clinical and radiological progress

| Age (days) | 7 | 8 | 9 | 12 | 13 |

| Day of admission | D1 | D2 | D3 | D6 | D7 |

| Events | Rapid deterioration within 12 hours of presenting to hospital with respiratory support escalated and infant placed on VA ECMO Lung biopsy obtained |

Biopsy results:

|

Lung biopsy rereviewed

Approved for rapid trio whole-genome sequencing Commenced on octreotide infusion |

Blood products for right haemothorax Intermittent cessation of heparin Genetics results: nil clinically significant variants identified. |

|

| Respiratory support | Room air → CPAP 5–7 cm → intubation (PIP 36–38 cm, PEEP 8 cm, FiO2 70%; TV 4 mL/kg) → HFOV (Mean airway pressure 30, Hz 15, FiO2 80% and 20ppm iNO → VA ECMO |

VA ECMO Rest settings: PCV PEEP 10 cm; PS 6 cm; RR 10; FiO2 60%; TV 1.5 mL/Kg, |

VA ECMO Rest settings: PCV PEEP 15 cm; PS 6 cm;RR 10; FiO2 85%; minimal chest movement |

VA ECMO Rest settings: PCV PEEP 10 cm; PS 10 cm; RR 10; FiO2 30%–35%; TV 1.5 mL/kg Occasional de recruitment requiring PEEP 12 cm, stiff compliance |

VA ECMO Rest settings: PCV PEEP 10 cm; PS 10 cm; RR 10; FiO2 30%–35%; TV 1.5 mL/kg |

| Steroids | Methylprednisolone (MP) 10 mg/kg | MP 10 mg/kg | MP 10 mg/kg | MP 2 mg/kg | MP 2 mg/kg |

| Octreotide | Octreotide infusion commenced 1 μg/kg |

Octreotide 2 μg/kg |

Octreotide 3 μg/kg |

||

| Images of CXR |

|

Post intubation CXR, prior to VA ECMO |

|

|

|

ACDMPV, alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of pulmonary veins; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; CXR, Chest x ray; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; HFOV, high-frequency oscillatory ventilation; iNO, inhaled nitric oxide; MP, methylprednisolone; PCV, pressure control ventilation; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; PIP, peak inspiratory pressure; PS, pressure support; RR, respiratory rate; TV, tidal volume; VA-ECMO, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Table 2.

Timeline of clinical and radiological progress

| Age (days) | 15 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 21 |

| Day of admission | D9 | D11 | D12 | D13 | D15 |

| Events | Blocked right ICC drain Right chest washout Blood product required |

Weaned off ECMO due to ongoing clot burden in circuit and improving respiratory status Chest drain blocked with clots Blood products required |

Chest drain unblocked Blood products required |

Chest drain removed | Extubated to CPAP |

| Respiratory support | VA ECMO Rest settings: PCV PEEP 10 cm; PS 10 cm; FiO2 30% |

VA ECMO Ventilation increased for lung recruitment PEEP 10 cm; PS 20 cm; FiO2 50%; RR 15; TV 5–7 mL/kg |

Off ECMO PCV; PEEP 10 cm; PS 15 cm; FiO2 30%; TV 7 mL/kg |

PCV; PEEP 8 cm; PS 12 cm; FiO2 30% | CPAP 5 cm FiO2 25% |

| Steroids | MP 2 mg/kg | MP 1 mg/kg | MP 1 mg/kg | MP 1 mg/kg | MP 1 mg/kg |

| Octreotide | Octreotide 3 μg/kg | Octreotide 5 μg/kg | Octreotide ceased | ||

| Images of CXR |

CXR post chest washout |

|

|

|

ACDMPV, alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of pulmonary veins; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; CXR, Chest X ray; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; HFVO, high-frequency volume oscillation; iNO, inhaled nitric oxide; MP, methylprednisolone; PCV, pressure control ventilation; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; PIP, peak inspiratory pressure; PS, pressure support; RR, respiratory rate; TV, tidal volume; VA-ECMO, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Due to his rapid deterioration in PICU, the patient had an urgent transthoracic echocardiogram that showed a structurally and functionally normal heart with a patent foramen ovale and no evidence of pulmonary hypertension.

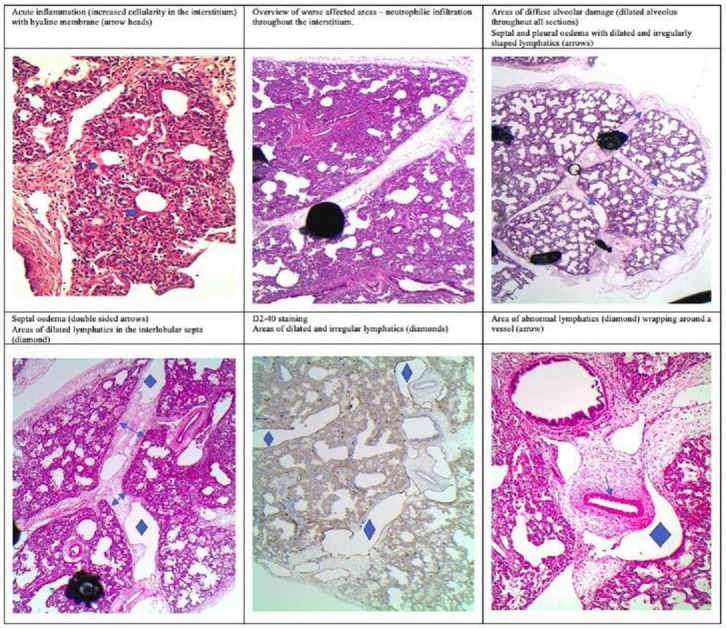

The patient underwent a wedge lung biopsy after full flows on VA-ECMO were established. The summary of the histopathology is shown in figure 1. The histology showed a mild-moderate amount of acute inflammatory infiltrates with polymorphonuclear cells present in the interstitial tissues and the air spaces. There were areas of moderate diffuse alveolar damage with empty and torn spaces in keeping with an element of pulmonary interstitial emphysema. There was also a degree of septal and pleural oedema within the interlobular septa and to a lesser extent the pleura, containing abnormal lymphatics (irregular and dilated) more than expected for the clinical context. There was no evidence of alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of pulmonary veins (ACD-MPV) and no evidence suggestive of surfactant deficiency. Periodic acid Schiff staining was negative and electron microscopy did not show specific ultrastructural abnormalities or evidence of glycogen accumulation.

Figure 1.

Histopathology of lung biopsy.

When suspicion for lymphangiectasis was raised, the patient had stool sent for alpha one antitrypsin level which later came back mildly elevated at 1.8 mg/g (normal <1.0), raising suspicion of a protein-losing state.

The patient and his parents were approved for rapid trio whole-genome sequencing which did not find an underlying genetic cause. Table 3 provides a summary of all investigations performed. He also underwent CT angiography of the chest and a lymphoscintigraphy which did not shed light on an underlying diagnosis.

Table 3.

Summary of investigation results

| Investigations | Values | Result |

| Blood culture (on presentation) | Negative | |

| Nasopharyngeal aspirate for viruses | Negative including COVID-19 negative | |

| Sputum culture | Negative | |

| CMV PCR blood/endotracheal aspirate | Negative | |

| HSV PCR blood | Negative | |

| Pneumocystis endotracheal aspirate | Negative | |

| Lung tissue culture (bacterial and fungal) | Negative | |

| Lung tissue panfungal PCR/RNA 16S PCR | Negative | |

| Immunoglobulin G | 4.36 g/L | Normal |

| Immunoglobulin A | 0.44 g/L | Normal |

| Immunoglobulin M | 0.32 g/L | Normal |

| Immunoglobulin E | 18 Ku/L | Normal |

| Lymphocyte count (day 3 of admission) | 1.2×109 /L | Low but normal % |

| CD3 T cells (%) | 0.8×109 /L (67) |

Low but normal % |

| CD4 helper subset | 0.56×109 /L (47%) | Low but normal % |

| CD8 T cytotoxic subset | 0.23×109 /L (19%) | Low but normal % |

| CD4:CD8 T cells | 2.47 | |

| CD 16/56 natural killer cells | 0.11×109 /L (9%) | Low but normal % |

| CD 19 B cells | 0.26×109 /L (22%) | Low but normal % |

| Faecal A1AT | >1.8 mg/g | High |

| Random urine protein | 0.13 g/L | Normal |

| Ammonia | 31 umol/L | Normal |

| Chromosome microarray | Normal | |

| Newborn screening | Normal | |

| CT chest | Normal great vessels, normal draining pulmonary veins RUL atelectasis posterior segment Patchy ground glass changes in dependent areas Some attenuation in lungs in expiratory phase, no gas trapping. Improving atelectasis with regions of likely improving consolidation and interstitial pulmonary oedema. Improving ARDS |

|

| Lymphoscintigraphy | Normal pattern of draining, patent thoracic ducts. No abnormal lymphatic dysfunction was found in the thorax. | |

| PSG | Normal baseline saturations and CO2 Tachypnoea intermittently to 80 bpm during REM sleep Mild increased work of breathing |

A1AT, alpha 1 antitrypsin; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CD, Cluster of differentiation; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CO2, carbon dioxide; COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease of 2019; CT, Computed Tomography; HSV, herpes simplex virus; PCR, Polymerase Chain Reaction; PSG, polysomnography; REM, rapid eye movement; RNA, Ribonucleic acid; RUL, right upper lobe.

Differential diagnosis

The initial raised WCC with neutrophilia is highly suspicious of an infective aetiology. However, the combination of early presentation in infancy and the catastrophic nature of the respiratory deterioration, necessitates the exclusion of an underlying interstitial lung disease, particularly of the diffuse developmental kind such as ACD-MPV. Early lung biopsy allowed the exclusion of this poor prognostic diagnosis and the continuation of VA ECMO. The finding of abnormal lymphatic vessels raised the possibility of underlying primary or secondary lymphangiectasia. Urgent transthoracic echocardiogram excluded any underlying congenital cardiac lesions such as hypoplastic left heart, total anomalous pulmonary venous return, pulmonary vein atresia or other obstructive forms of congenital heart disease leading to secondary lymphangiectasia. This was also later excluded by CT angiography which did not demonstrate specific abnormalities in the pulmonary parenchyma. Urgent trio whole-genome sequencing excluded genetic syndromes and known genetic causes of lymphangiectasia. Extensive investigations for an underlying infective pathology did not yield an identifiable pathogen. The patient’s clinical course is not typical of primary PL while other secondary causes were not found.

Treatment

The patient was initially commenced on intravenous cefotaxime, ampicillin and aciclovir. After his rapid deterioration in PICU, his antibiotic cover was broadened. Due to initial suspicion of an underlying interstitial lung disease and risk of significant barotrauma secondary to high ventilatory pressures required, the patient was commenced on 10 mg/kg of methylprednisolone (day 1 of admission) for 3 days and weaned over 2 weeks. Based on the lack of clinical progress on high dose methylprednisolone and worsening radiological changes (see table 1), an octreotide infusion was commenced on day 3 of admission starting at a rate of 1 μg/kg/hour and incrementally increased to 5 μg/kg/hour. The total duration of octreotide infusion was over 9 days. The rationale for using octreotide was based on the findings of lymphangiectasia on lung biopsy and the use of octreotide to reduce lymphatic flow in the management of chylothorax. Retrospectively, surfactant could have been an alternative therapy trialled to improve lung compliance. Table 1 and table 2 illustrates the patient’s clinical and radiological progress in relation to treatments.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient showed radiological improvement on day 5 of admission. His ECMO course was complicated by right haemothorax which required a massive transfusion protocol. Due to his haemothorax, anticoagulation was ceased, resulting in a high clot burden throughout his VA ECMO circuit. He received 10 days of VA ECMO and on day 16 of admission he was extubated to low flow oxygen. He improved uneventfully and was weaned off all respiratory support by day 20 of admission.

The rest of the patient’s hospital admission involved re-establishing feeds and weaning sedation. He was discharged from the hospital without any support on day 39 (46 days postnatal age) of admission. The patient has been followed up closely in the outpatient clinic without evidence of ongoing respiratory sequelae.

Discussion

In the absence of an infective pathology to explain the respiratory deterioration, the differential diagnosis of acute respiratory distress in infancy commands the exclusion of underlying congenital or genetic disease. We describe a case of an otherwise normal 7-day-old male infant who presented with rapid and catastrophic respiratory failure. Although there were findings of PL, after excluding infection, congential or genetic cause, the unifying diagnosis does not appear entirely clear to the authors. This case has raised many interesting discussion points including differentiating primary versus secondary PL, the role of lymphatics in the pathophysiology of acute respiratory syndrome (paediatrics and adults) as well as the exploration of novel therapies which may affect lymphatic flow as an adjunct in the treatment of ARDSs.

Categorisation of PL has undergone several changes historically and terminology can be confusing.1 6 14 Therefore, this makes the exact incidence and mortality rate (for different categories of PL) difficult to determine. The most recent classification suggests a distinction between primary vs secondary. Primary, or often termed congenital PL, is thought to be due to a failure in the regression of pulmonary interstitial connective tissue resulting in dilation of pulmonary lymphatics. Secondary forms are the result of underlying pathologies which disrupt the lymphatic drainage and increase lymph production. These pathologies include congenital heart diseases, trauma, infections or tumours.6 Congenital PL is a rare disease associated historically with a poor prognosis. Some patients (mainly those who present beyond the neonatal period and with localised disease) have survived due to improved respiratory support technologies.2 15–18 It is important to note that these studies were published before changes in recommended categorisation of PL and those infants requiring ECMO historically had a mortality rate of 100%.19 The exact incidence of congenital PL is difficult to determine. Based on autopsy data, it is between 0.5% and 1% of fetoneonatal deaths.20 21 It is important to note that many of these infants also had congenital heart disease, which would be classified as secondary lymphangiectasis based on more recent classification.6 20 None of the papers published discuss the role of barotrauma as a potential cause of dilated and abnormal lymphatics. Barotrauma was raised as a possible cause of our patient’s abnormal lymphatics as he required extremely high mean airway pressures to manage his poor lung compliance. The survivors go on to have intermittent respiratory symptoms such as wheeze, recurrent pneumonia, chronic cough and poor weight gain in the first year of life. However, a majority of the symptoms resolve with time.2 16 The fact that the patient recovered so quickly and the lack of nutritional or ongoing respiratory symptoms to date makes the diagnosis of congenital PL questionable. Were the patient’s underlying pulmonary lymphatics inherently abnormal (structurally and or functionally) or were they overwhelmed by fluid accumulation secondary to a transient insult including the possibility of significant barotrauma? Until this day, the exact diagnosis remains elusive.

After excluding a congenital or genetic cause of respiratory distress in infancy, the pathophysiology of pARDS is similar to that of adult ARDS. An insult causes damage to the capillary and alveolar epithelium resulting in a build-up of excess fluid in both the Interstitium and alveoli. The fluid build-up impairs gas exchange, decrease compliance and increase pulmonary arterial pressure. While some animal and human studies have looked at the role of lymphatics in health and disease,22 23 evidence of its contribution in ARDS is lacking. Animal studies have shown that the pulmonary lymphatic flow can increase up to 10-fold resulting in pulmonary oedema due to chronic heart failure.24 Once the fluid has entered the Interstitium, it leaks into the alveolar space resulting in reduced surface tension and alveolar collapse.25 Again, animal studies have shown increased lymphatic flow in phosgene (irritant gas) poisoning which may translate to similar pathology induced by other toxins or irritants.26 Mice models have shown new lymphatic vessel formation to clear the extravasated fluid from abnormally leaky blood vessels in inflamed airways.27

While some adjunctive therapies for ARDS have been explored in the past, minimal research have looked at agents that affect the lymphatic system.13 Interestingly, mechanical ventilation has been shown to impede lung lymph flow and even more when PEEP is applied. Animals studies have shown that when PEEP is applied, the lymphatic flow in the lungs is reduced to almost 50% compared with that during zero end-expiratory pressure.28 29

Octreotide is commonly used in the critical care setting to treat various conditions in both paediatric and adult medicine.7 8 In paediatrics, octreotide has been successfully used to treat chylothorax postcardiac surgery.9 10 Although the mechanism is not entirely clear it is thought that somatostatins reduce chyle production by inhibiting gastric, pancreatic and biliary secretions. Another mechanism is reducing flow through the splanchnic circulation, thus decreasing chyle flow in the thoracic duct allowing an injured duct to heal.30 31 Octreotide also induces vasoconstriction of splanchnic vessels thereby reducing blood flow in the splanchnic and portal venous systems.32 Coelho et al showed that intestinal ischaemia and reperfusion caused bronchial hyper-reactivity and that this distant effect was mediated by cytokines such as interleukin-18 carried through the lymphatic system.33 This raises the question of whether octreotide mediated reduction in lymphatic flow can reduce further damage to the lung parenchyma in patients suffering from ARDS. Mice studies suggest that somatostatin may have a protective effect on acute lung injury by elevating levels of heat shock protein 90 and enhancing the activity of glucocorticoid receptors, which is thought to be the main protector against the development of acute lung injury. Other small animal studies have also suggested anti-inflammatory effects of somatostatins that may be protective against acute lung injury.34 35 Although octreotide is generally well tolerated, it can cause transient changes to blood glucose levels and gastrointestinal symptoms.36 Case reports have associated octreotide with necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) in term and preterm neonates treated for congenital chylothorax.37–39 Therefore, prior to treatment, the risks and benefits needs to be considered and during periods of octreotide treatment, patients should have their blood glucose levels and symptoms of NEC monitored closely.

This case discussed interesting and pertinent questions around the role of lymphatics in the pathophysiology of acute respiratory syndrome currently absent in the literature. The authors hope that it has highlighted the need for further research in this area and the exploration of potential novel adjuvant therapies that target the lymphatics in the treatment of paediatric and adult ARDS and other pulmonary diseases.

Learning points.

Approach to acute respiratory distress in infancy require broad consideration of differential diagnoses including congenital and genetic diseases.

It can be difficult to differentiate between primary and secondary pulmonary lymphangiectasis.

The role of pulmonary lymphatics in the pathophysiology of acute respiratory distress syndrome is unclear and deserves further research.

Further exploration of novel agents that may affect pulmonary lymphatic flow as an adjuvant treatment for acute respiratory distress syndromes is needed.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement to Dr Michael Krivanek who provided the histopathology images of the lung biopsy.

Footnotes

Contributors: Patient was under the care of ML and EC. Report was written by ML, EC, HS and JMB.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained from parent(s)/guardian(s)

References

- 1.Noonan JA, Walters LR, Reeves JT. Congenital pulmonary lymphangiectasis. Am J Dis Child 1970;120:314–9. 10.1001/archpedi.1970.02100090088006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouchard S, Di Lorenzo M, Youssef S, et al. Pulmonary lymphangiectasia revisited. J Pediatr Surg 2000;35): :796–800. 10.1053/jpsu.2000.6086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta S, Sankar J, Lodha R, et al. Comparison of prevalence and outcomes of pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome using pediatric acute lung injury consensus conference criteria and Berlin definition. Front Pediatr 2018;6:93. 10.3389/fped.2018.00093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khemani RG, Smith L, Lopez-Fernandez YM, et al. Paediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome incidence and epidemiology (PARDIE): an international, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 2019;7:115–28. 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30344-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prasertsan P, Anuntaseree W, Ruangnapa K, et al. Severity and mortality predictors of pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome according to the pediatric acute lung injury consensus conference definition. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2019;20:e464–72. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faul JL, Berry GJ, Colby TV, et al. Thoracic lymphangiomas, lymphangiectasis, lymphangiomatosis, and lymphatic dysplasia syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:1037–46. 10.1164/ajrccm.161.3.9904056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tauber MT, Harris AG, Rochiccioli P. Clinical use of the long acting somatostatin analogue octreotide in pediatrics. Eur J Pediatr 1994;153:304–10. 10.1007/BF01956407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan MM, Chan MM, Mengshol JA, et al. Octreotide: a drug often used in the critical care setting but not well understood. Chest 2013;144:1937–45. 10.1378/chest.13-0382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pratap U, Slavik Z, Ofoe VD, et al. Octreotide to treat postoperative chylothorax after cardiac operations in children. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;72:1740–2. 10.1016/S0003-4975(01)02581-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tatar T, Kilic D, Ozkan M, et al. Management of chylothorax with octreotide after congenital heart surgery. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;59:298–301. 10.1055/s-0030-1250296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacLean JE, Cohen E, Weinstein M. Primary intestinal and thoracic lymphangiectasia: a response to antiplasmin therapy. Pediatrics 2002;109:1177–80. 10.1542/peds.109.6.1177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamberts SW, van der Lely AJ, de Herder WW, et al. Octreotide. N Engl J Med 1996;334:246–54. 10.1056/NEJM199601253340408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rowan CM, Klein MJ, Hsing DD, et al. Early use of adjunctive therapies for pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome: a PARDIE study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;201): :1389–97. 10.1164/rccm.201909-1807OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Virchow R. Gesammelte Abhandlungen zur Wissenschaftlichen Medicin. Vol. 982. Frankfurt: Meidinger Sohn, 1856. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott C, Wallis C, Dinwiddie R, et al. Primary pulmonary lymphangiectasis in a premature infant: resolution following intensive care. Pediatr Pulmonol 2003;35:405–6. 10.1002/ppul.10241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barker PM, Esther CR, Fordham LA, et al. Primary pulmonary lymphangiectasia in infancy and childhood. Eur Respir J 2004;24:413–9. 10.1183/09031936.04.00014004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoeffel JC, Marcon F, Worms AM. Diffuse pulmonary lymphangiectasis with heart defect discovered 4 months post-natally. Padiatr Padol 1992;27:25–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung CJ, Fordham LA, Barker P, et al. Children with congenital pulmonary lymphangiectasia: after infancy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1999;173:1583–8. 10.2214/ajr.173.6.10584805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mettauer N, Agrawal S, Pierce C, et al. Outcome of children with pulmonary lymphangiectasis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2009;44:351–7. 10.1002/ppul.21008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.France NE, Brown RJ. Congenital pulmonary lymphangiectasis. Report of 11 examples with special reference to cardiovascular findings. Arch Dis Child 1971;46:528–32. 10.1136/adc.46.248.528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laurence KM. Congenital pulmonary lymphangiectasis. J Clin Pathol 1959;12:62–9. 10.1136/jcp.12.1.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Chemaly S, Levine SJ, Moss J. Lymphatics in lung disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008;1131:195–202. 10.1196/annals.1413.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stump B, Cui Y, Kidambi P, et al. Lymphatic changes in respiratory diseases: more than just remodeling of the lung? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2017;57:272–9. 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0290TR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uhley HN, LEEDS SE, SAMPSON JJ, et al. Role of pulmonary lymphatics in chronic pulmonary edema. Circ Res 1962;11:966–70. 10.1161/01.RES.11.6.966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kee K, Naughton MT. Heart failure and the lung. Circ J 2010;74:2507–16. 10.1253/circj.CJ-10-0869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cameron GR, Courtice FC. The production and removal of oedema fluid in the lung after exposure to carbonyl chloride (phosgene). J Physiol 1946;105:175–85. 10.1113/jphysiol.1946.sp004161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baluk P, Tammela T, Ator E, et al. Pathogenesis of persistent lymphatic vessel hyperplasia in chronic airway inflammation. J Clin Invest 2005;115:247–57. 10.1172/JCI200522037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frostell C, Blomqvist H, Hedenstierna G, et al. Thoracic and abdominal lymph drainage in relation to mechanical ventilation and PEEP. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1987;31:405–12. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1987.tb02592.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maybauer DM, Talke PO, Westphal M, et al. Positive end-expiratory pressure ventilation increases extravascular lung water due to a decrease in lung lymph flow. Anaesth Intensive Care 2006;34:329–33. 10.1177/0310057X0603400307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalomenidis I. Octreotide and chylothorax. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2006;12:264–7. 10.1097/01.mcp.0000230629.73139.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakabayashi H, Sagara H, Usukura N, et al. Effect of somatostatin on the flow rate and triglyceride levels of thoracic duct lymph in normal and vagotomized dogs. Diabetes 1981;30:440–5. 10.2337/diab.30.5.440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beglinger C, Drewe J. Somatostatin and octreotide: physiological background and pharmacological application. Digestion 1999;60 Suppl 2:2–8. 10.1159/000051474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coelho FR, Cavriani G, Soares AL, et al. Lymphatic-borne IL-1beta and the inducible isoform of nitric oxide synthase trigger the bronchial hyporesponsiveness after intestinal ischema/reperfusion in rats. Shock 2007;28:694–9. 10.1097/shk.0b013e318053621d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Helyes Z, Pintér E, Németh J, et al. Effects of the somatostatin receptor subtype 4 selective agonist J-2156 on sensory neuropeptide release and inflammatory reactions in rodents. Br J Pharmacol 2006;149:405–15. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu L, Liu Y, Han W. Influences and mechanisms of somatostatin on inflammation in endotoxin-induced acute lung injury mice (Chinese) English Abstract. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yin R, Zhang R, Wang J, et al. Effects of somatostatin/octreotide treatment in neonates with congenital chylothorax. Medicine 2017;96:e7594. 10.1097/MD.0000000000007594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohseni-Bod H, Macrae D, Slavik Z. Somatostatin analog (octreotide) in management of neonatal postoperative chylothorax: is it safe? Pediatr Crit Care Med 2004;5:356–7. 10.1097/01.PCC.0000123552.36127.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Büyüktiryaki M, Oncel MY, Okur N, et al. Necrotizing enterocolitis after octreotide treatment in a preterm newborn with idiopathic congenital chylothorax. APSP J Case Rep 2017;8:34. 10.21699/ajcr.v8i5.628 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chandran S, Agarwal A, Llanora GV, et al. Necrotising enterocolitis in a newborn infant treated with octreotide for chylous effusion: is octreotide safe? BMJ Case Rep 2020;13:e232062. 10.1136/bcr-2019-232062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]