Abstract

Introduction

Long-term safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (AS) has not been previously reported.

Methods

In SELECT-AXIS 1, patients receiving placebo were switched to upadacitinib 15 mg once daily at week 14 while patients initially randomised to upadacitinib continued their regimen through week 104. Efficacy was assessed using as-observed (AO) and non-responder imputation (NRI).

Results

Of 187 patients randomised, 144 patients (77%) completed week 104. Among patients receiving continuous upadacitinib, 85.9% (AO) and 65.6% (NRI) achieved Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society 40 response (ASAS40) at week 104. Similar magnitude of ASAS40 responses were observed among patients who switched from placebo to upadacitinib (88.7% and 63.8%, respectively). The mean change from baseline to week 104 in Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada MRI spine and sacroiliac joint inflammation scores were –7.3 and –5.3, respectively, in the continuous upadacitinib group and –7.9 and –4.9 in the placebo-to-upadacitinib switch group. The mean (95% CI) change from baseline to week 104 in the modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spine Score was 0.7 (0.3, 1.1) in the total group. Adverse event rate was 242.7/100 patient-years. No serious infections, adjudicated major adverse cardiovascular events, lymphoma, non-melanoma skin cancer, or gastrointestinal perforations were observed.

Conclusions

Upadacitinib 15 mg once daily showed sustained and consistent efficacy over 2 years for ASAS40 and other clinically relevant endpoints. A low rate of radiographic progression was observed and no new safety findings were observed.

Keywords: spondylitis, ankylosing; inflammation; magnetic resonance imaging

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT?

Upadacitinib demonstrated significant improvement in disease activity, function and imaging outcomes versus placebo over 14 weeks in the randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2/3 SELECT-AXIS 1 study.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

This is the first study to report long-term (2-year) safety and efficacy data with a Janus kinase inhibitor for the treatment of patients with active ankylosing spondylitis.

The results showed consistent maintenance of improvement in signs and symptoms of ankylosing spondylitis, including clinical remission, pain, function, imaging and objective signs of inflammation with upadacitinib 15 mg once daily treatment over 2 years.

HOW MIGHT THIS IMPACT ON CLINICAL PRACTICE OR FURTHER DEVELOPMENTS?

The findings of this study suggest that upadacitinib continues to have a favourable benefit–risk profile and represents valuable treatment for patients with active ankylosing spondylitis.

Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS), also known as radiographic axial spondyloarthritis, is a chronic, inflammatory rheumatic disease characterised by back pain, morning stiffness, and peripheral (such as arthritis and enthesitis) and extra-musculoskeletal manifestations (uveitis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), psoriasis).1 2 AS is associated with inflammation and can result in irreversible structural damage, and therapeutic intervention is often necessary to control the signs and symptoms of the disease; maintain physical function, quality of life, and work productivity; and prevent radiographic progression.3 4

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors have emerged as therapies for AS5–7 and other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.8 Upadacitinib, an oral JAK inhibitor,9 achieved the primary endpoint (Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society 40 response (ASAS40)) as well as several multiplicity-adjusted secondary endpoints in the randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2/3 SELECT-AXIS 1 study, demonstrating significant improvement in disease activity, function, and imaging outcomes versus placebo.10 Furthermore, interim results from the SELECT-AXIS 1 extension study further demonstrated that efficacy was sustained and upadacitinib was well tolerated over 1 year of treatment.11

The objective of this analysis of the SELECT-AXIS 1 study is to report the final 2-year safety and efficacy, including MRI and spinal radiographic assessment, in patients with AS receiving upadacitinib 15 mg once daily.

Methods

Study design

SELECT-AXIS 1 (NCT03178487) was a randomised, multicentre, phase 2/3 study that included a 14-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled period 1 followed by a 90-week, open-label extension period 2. The methods have been previously published.10 11 Briefly, patients were randomised 1:1 to upadacitinib 15 mg once daily or placebo for 14 weeks. Patients who completed period 1 were eligible to enter period 2 to receive open-label upadacitinib 15 mg once daily for 90 weeks up to week 104. Patients and investigators remained blinded to the patients’ original period 1 assignment through the end of period 2.

Participants

The study enrolled adult patients (aged ≥18 years) with a clinical diagnosis of AS who met the modified New York criteria, had active disease at screening and baseline (ie, week 0), and had an inadequate response to ≥2 non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or intolerance to or contraindication for NSAIDs.10 Patients who were receiving a stable dose of concomitant conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), oral glucocorticoids, NSAIDs and analgesics were also eligible. Patients with prior exposure to JAK inhibitors or biologic DMARDs (such as tumour necrosis factor inhibitors and interleukin-17A inhibitors) were excluded.

Endpoints

Proportions of patients achieving ASAS20, ASAS40, ASAS partial remission, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index 50 response (BASDAI50) and Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) based on C reactive protein (CRP) inactive disease (ID; <1.3), low disease activity (LDA; <2.1), major improvement (MI; decrease from baseline ≥2.0), and clinically important improvement (CII; decrease from baseline ≥1.1) through 104 weeks were assessed.12 13

Changes from baseline in ASDAS,14 Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), linear Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI), Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score (MASES), 66/68 swollen and tender joint counts (SJC66/TJC68), Patient Global Assessment of Disease Activity (PtGA), Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI; on a scale of 0–100), ASAS Health Index (HI), AS quality of life (ASQoL), and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy−Fatigue (FACIT-F)15 were assessed through 104 weeks.

Imaging assessments included changes from baseline in the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC) MRI spine inflammation score (range 0–108) and sacroiliac (SI) joint inflammation score (range 0–72).16 17 Two-year SPARCC MRI inflammation results are based on reading session 2, which included images from baseline, week 14 and week 104 (2-year reading) and from premature discontinuation visits or unscheduled visits prior to week 104. Of note, data from reading session 1 (which included images from baseline and week 14) have been previously presented.10 In addition, spinal radiographic progression was assessed based on the modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spine Score (mSASSS; range 0–72)18 in patients with available conventional radiographs of the spine from baseline and week 104. No radiographic progression at 2 years was defined by change from baseline in mSASSS <2 or ≤0. Radiographs of the spine were included from premature discontinuation visits before week 104. For the MRI and mSASSS analyses, images grouped per patient and per imaging modality were independently assessed by two primary readers blinded to the treatment and time points. If needed, discrepancies between the primary readers for week 14 or week 104 imaging assessments were resolved by adjudication by a third reader. For adjudicated cases, the average of the two closest change scores of the three readings was used. Adjudication was triggered by differences between the primary readers’ change scores that exceeded a certain threshold based on mean absolute differences.10 19

Pain endpoints included patient assessments of back pain and nocturnal back pain, patient assessment of pain, BASDAI question 2 (back pain) and BASDAI question 3 (peripheral pain/swelling). Safety was assessed as rate of treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) reported as events per 100 patient-years (PY). For uveitis, both event rate and incidence rate are reported. Treatment-emergent AEs were defined as AEs with an onset date after the first dose of study drug and no more than 30 days after the last dose of study drug.

Statistical analyses

Efficacy analyses were performed by randomised treatment group sequence in patients receiving upadacitinib 15 mg once daily from baseline throughout periods 1 and 2 (continuous upadacitinib group) and in patients switching from randomised placebo at week 14 (period 1) to open-label upadacitinib 15 mg once daily for period 2 (placebo-to-upadacitinib switch group).

Primary, prespecified efficacy analyses are based on as observed (AO) data. For binary endpoints, response rates and 95% CIs are reported AO and using non-responder imputation (NRI) for missing data. Patients who prematurely discontinued study drug were considered as non-responders for all subsequent visits, and patients with any missing values at a specific visit were treated as non-responders for that visit.

For continuous efficacy endpoints (except for mSASSS), descriptive statistics (AO data; primary analysis) and estimated changes from baseline with 95% CI from mixed-effect model repeated measures (MMRM) are reported. MMRM included the categorical fixed effects of treatment, visit, treatment-by-visit interaction, and stratification factor of high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP) level at screening visit, premature discontinuation flag, and the continuous fixed covariate of baseline value using an unstructured variance-covariance matrix. No statistical comparison was performed between the two treatment group sequences. Descriptive statistics (AO data) were reported for mSASSS. Estimated change from baseline with 95% CI from an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model was reported for mSASSS; the ANCOVA model included treatment and the stratification factor hsCRP level at screening visits and baseline value as the covariate.

The following sensitivity analyses were performed on SPARCC MRI spine and SI joint inflammation scores. Both descriptive statistics (AO data) and MMRM analysis were performed for all available data including from patients with delayed MRIs conducted outside of the analysis window (analysis window defined as 99 days before first study drug dose up to 3 days after first dose for baseline reading, +4 days after first dose up to the first dose of period 2 for the week 14 MRI, and +1 day after first dose of period 2 up to +182 days after week 104 for the week 104 MRI).

Results

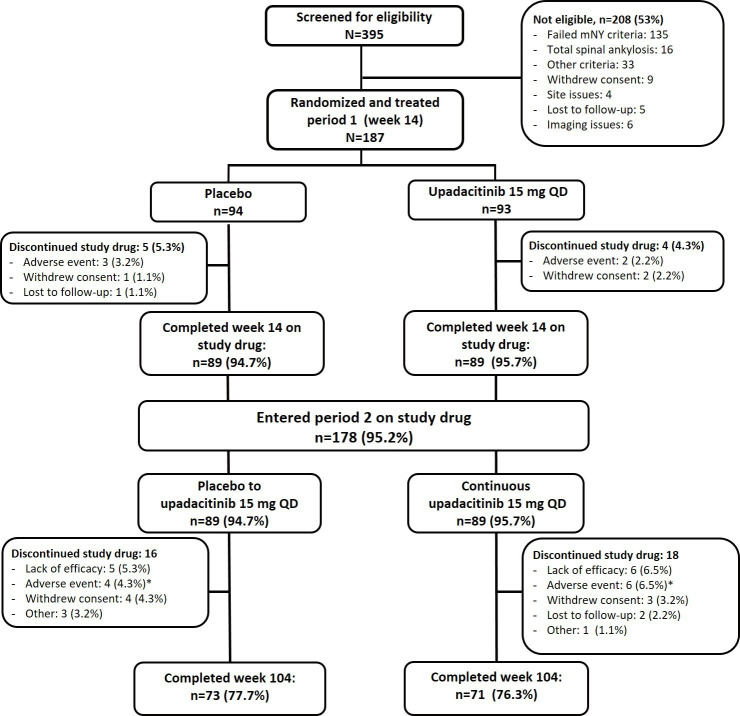

Of the 187 patients randomised to period 1, 178 (continuous upadacitinib group, n=89; placebo-to-upadacitinib switch group, n=89) completed week 14 on study drug and entered the open-label extension, of which 144 patients (77%) completed week 104 on study drug (upadacitinib, n=71; placebo-to-upadacitinib, n=73; figure 1). Lack of efficacy (upadacitinib, n=6 (7%); placebo-to-upadacitinib, n=5 (6%)) and AEs (upadacitinib, n=6 (7%); placebo-to-upadacitinib, n=4 (4%)) were the most common reasons for discontinuation of study drug between weeks 14 and 104. Treatment arms were well balanced at baseline as reported previously.10

Figure 1.

Patient disposition through week 104. *AEs leading to discontinuation of study drug in period 2 in the continuous upadacitinib group were diarrhoea, headache, and vertigo (n=1), pulmonary embolism, herpes zoster, headache, squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue, and decreased haemoglobin (n=1 each) and in the placebo-to-upadacitinib group were hemiparesthesia and intervertebral disc protrusion(n=1), vasculitis, hyperplasia of prostate and anterior uveitis flare (n=1 each). mNY, modified New York; QD, once daily.

Efficacy

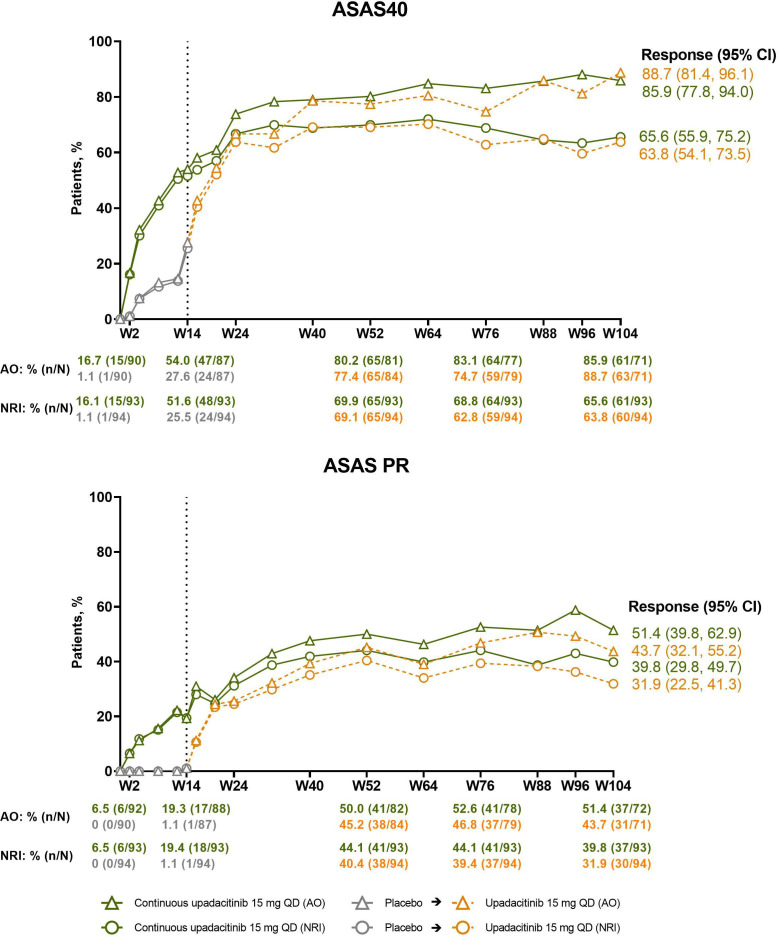

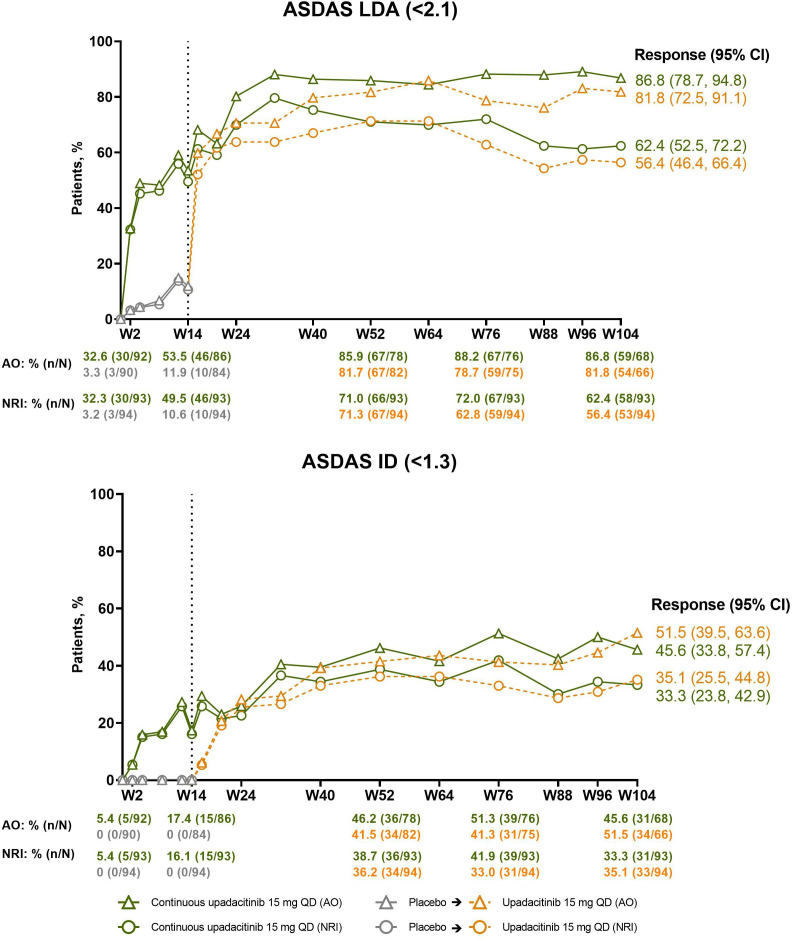

The percentage of patients in the continuous upadacitinib group who achieved the primary efficacy endpoint of ASAS40 at week 14 (NRI, 52%; AO, 54%) continued to increase through weeks 32–40, at which point the responses started to plateau and were subsequently maintained through week 104 (NRI, 66%; AO, 86%; figure 2; online supplemental table 1). An analogous pattern of improvement was observed in ASAS partial remission responses (NRI, 40%; AO, 51%; figure 2), ASDAS LDA (NRI, 62%; AO, 87%), and ASDAS ID (NRI, 33%; AO, 46%) at week 104 (figure 3). In patients who switched from placebo to upadacitinib, comparable speed of onset and magnitude of responses were observed; responses at week 104 were 64%/89% (NRI/AO) for ASAS40, 56%/82% for ASDAS LDA, 35%/52% for ASDAS ID, and 32%/44% for ASAS partial remission (figures 2 and 3; online supplemental table 1). A clear shift from ASDAS high disease activity toward ASDAS ID and LDA was achieved over time with upadacitinib treatment presented as individual patient data (online supplemental figure 1).

Figure 2.

Percentages of patients achieving ASAS40 and ASAS PR over time. Dashed line: all patients randomised to placebo in period 1 who received open-label upadacitinib starting from week 14. Descriptive statistics are provided. AO, as observed; ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society; NRI, non-responder imputation; PR, partial remission; QD, once daily; W, week.

Figure 3.

Percentages of patients achieving ASDAS LDA (<2.1) and ASDAS ID (<1.3) over time. Dashed line: all patients randomised to placebo in period 1 who received open-label upadacitinib starting from week 14. Descriptive statistics are provided. AO, as observed; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Scores; ID, inactive disease; LDA, low disease activity; NRI, non-responder imputation; QD, once daily; W, week.

rmdopen-2022-002280supp001.pdf (3.1MB, pdf)

Likewise, the percentage of patients achieving ASAS20, BASDAI50, ASDAS CII and ASDAS MI (online supplemental figures 2 and 3) improved through approximately weeks 32–40, at which point the responses started to plateau and were subsequently maintained through week 104 in the continuous upadacitinib group. Patients who switched from placebo to upadacitinib at week 14 demonstrated a rapid onset of response after the switch and achieved a similar magnitude of response at week 104 as observed in patients on continuous upadacitinib (online supplemental figures 2 and 3).

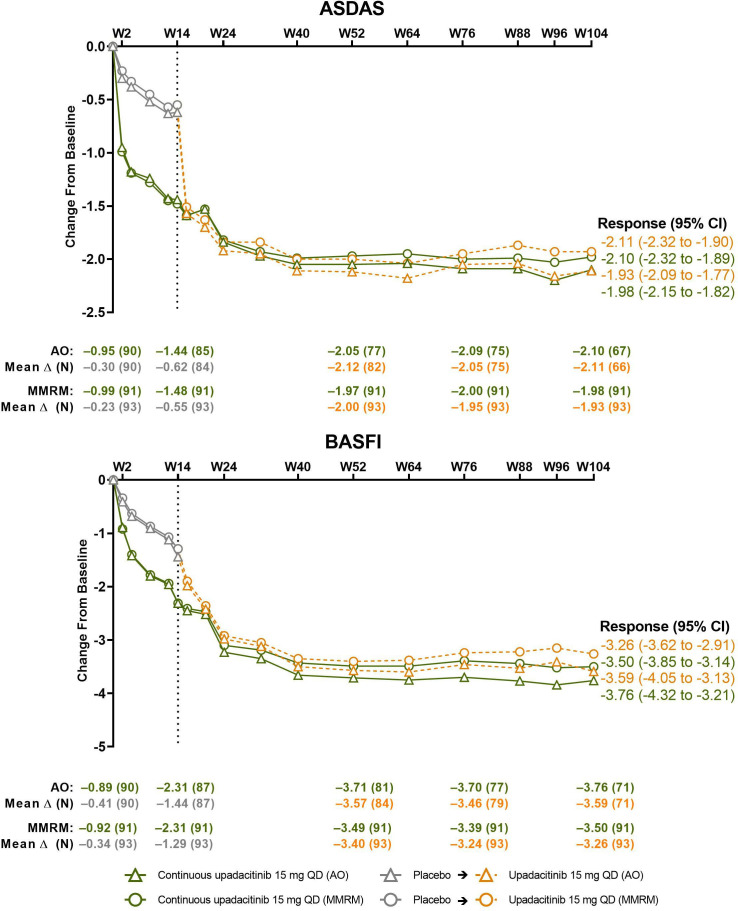

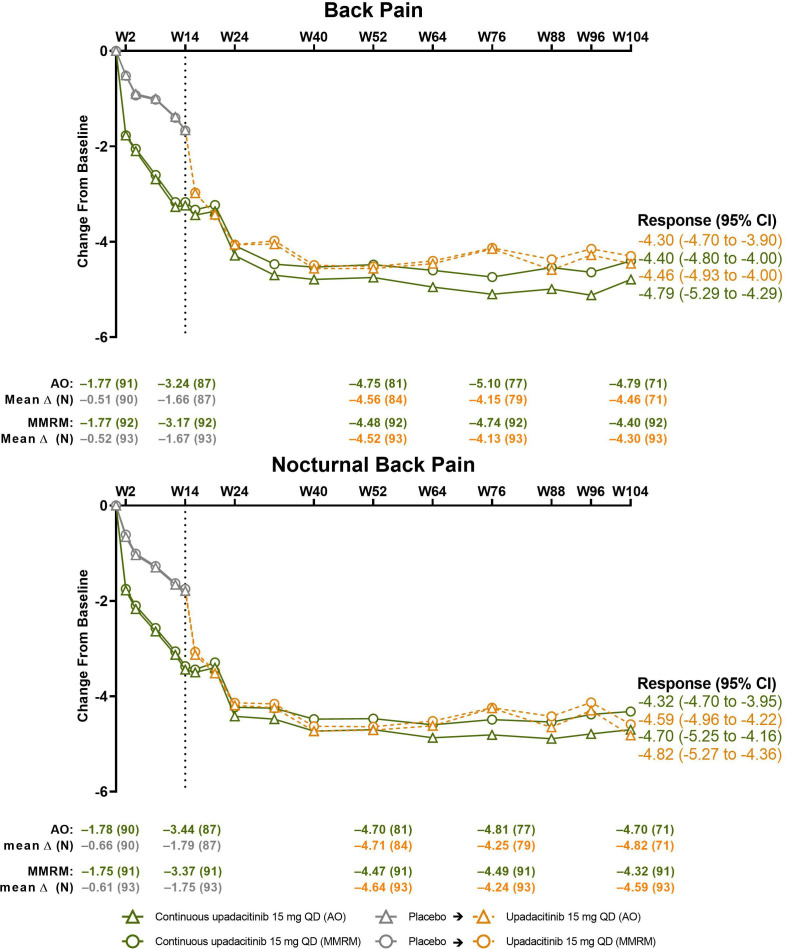

Mean changes from baseline to week 104 in disease activity (ASDAS) and pain endpoints consistently improved through weeks 42–50 and were subsequently sustained throughout the remainder of the study in the continuous upadacitinib group. A similar magnitude of improvement was seen in the placebo-to-upadacitinib switch group after initiation of upadacitinib at week 14 (figures 4 and 5, online supplemental table 2 and figure 4). Improvements in BASFI were sustained through week 104 (figure 4, online supplemental tables 1 and 2). Similarly, improvements in morning stiffness, based on mean of BASDAI questions 5 and 6, and inflammation, based on hsCRP, were sustained through week 104 (online supplemental table 2 and figure 5). Analogous patterns of improvement over time were shown in assessments of quality of life (ASQoL and ASAS HI), spinal mobility (BASMI), enthesitis and peripheral manifestations (MASES, TJC68/SJC66), PtGA and patient assessment of pain (online supplemental tables 1,3 and figures 6,7).

Figure 4.

Changes from baseline in ASDAS and BASFI over time. Dashed line: all patients randomised to placebo in period 1 who received open-label upadacitinib starting from week 14. AO, as observed; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Scores; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; MMRM, mixed-effect model repeated measure; QD, once daily; W, week.

Figure 5.

Changes from baseline in back pain and nocturnal back pain over time. Dashed line: all patients randomised to placebo in period 1 who received open-label upadacitinib starting from week 14. Back pain is based on the question, ‘What is the amount of back pain that you experienced at any time during the last week?’ and nocturnal back pain on the question, ‘What is the amount of back pain at night that you experienced during the last week?’ Both scored on a numeric rating scale of 0–10. AO, as observed; MMRM, mixed-effect model repeated measure; QD, once daily; W, week.

Numerically greater improvement from baseline to week 14 in FACIT-F (mean (SD) change: 6.5 (12.1) vs 3.9 (10.4)), TJC68 (–2.0 (3.9) vs –0.9 (3.9)), and SJC66 (–0.6 (1.7) vs –0.3 (2.4)) were observed in the upadacitinib group versus placebo. Improvements after week 14 were maintained through weeks 52 and 104 in the continuous upadacitinib group (online supplemental table 2). Patients in the placebo-to-upadacitinib switch group also showed meaningful improvement following the switch, which was maintained through week 104.

Among patients who were employed at baseline, the mean (95% CI) WPAI overall work impairment score continued to improve through the course of the study in the continuous upadacitinib group (–20.5 (–27.1 to –14.0) at week 14 to –34.5 (–44.2 to –24.7) at week 104; AO) and placebo-to-upadacitinib switch group (–12.3 (–19.8 to –4.8) at week 14 to –28.3 (–36.7 to –19.8) at week 104; online supplemental table 4). Results were similar in the MMRM analysis.

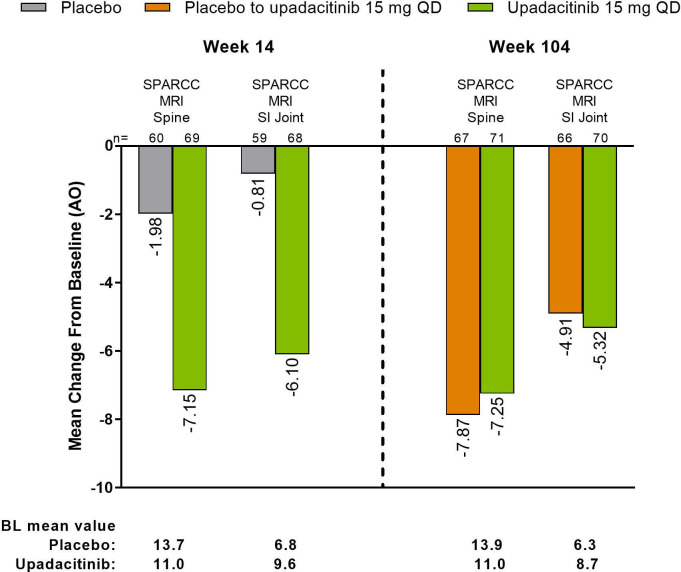

SPARCC MRI spine and SI joint inflammation scores

The mean (95% CI) decrease from baseline to week 14 in the SPARCC MRI spine inflammation score (−7.2 (−10.2 to −4.2)) was maintained through week 104 (−7.3 (−10.8 to −3.7)) in the continuous upadacitinib group (figure 6). Although there was only a small mean decrease from baseline in the SPARCC MRI spine inflammation score in the placebo group at week 14 (−2.0 (−3.7 to −0.2)), the score improved by week 104 after switch to upadacitinib (−7.9 (−11.2 to −4.6)), showing a similar magnitude of response compared with patients in the continuous upadacitinib group. Similar results were observed in SPARCC MRI SI joint inflammation score for mean decrease from baseline to week 14 (−6.1 (−8.5 to −3.7)), which was maintained through week 104 (−5.3 (−7.6 to −3.1)) in the continuous upadacitinib group; an improvement from week 14 (−0.8 (−2.3 to 0.7)) to week 104 (−4.9 (−7.0 to −2.8)) was observed in patients who switched from placebo to upadacitinib (figure 6). Consistent results were observed based on MMRM analyses (online supplemental figure 8). Additionally, consistent results were also observed in the sensitivity analyses performed in all patients with MRI data, including those with MRIs outside the predefined analysis window (online supplemental figure 9).

Figure 6.

Changes from baseline in SPARCC MRI Spine and SI Joint Inflammation Scores at week 14 and week 104 by AO analysis. Results are from reading session 2, which included MRIs from baseline, week 14, and week 104. AO, as observed; BL, baseline; SI, sacroiliac; SPARCC, Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada.

The cumulative probability plots for the SPARCC spine and SI joint inflammation change scores showed a consistent pattern of improvement at week 104 for patients in the continuous upadacitinib group and placebo-to-upadacitinib switch group; results for the primary and sensitivity MRI analyses were consistent (online supplemental figure 10).

mSASSS spinal radiographs

Based on the reading of spinal radiographs, the mean (95% CI) change from baseline to week 104 in mSASSS was 0.7 (0.3 to 1.1) in the total group (continuous upadacitinib, 0.6 (0.1 to 1.1); placebo-to-upadacitinib, 0.8 (0.2 to 1.4); table 1). The cumulative probability plot of change for mSASSS from baseline to week 104 showed a similar magnitude of change between the continuous upadacitinib group and placebo-to-upadacitinib switch group (online supplemental figure 11). Among the nine patients who showed the highest mSASSS progression over 2 years, the majority were male and human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-B27 positive with high baseline mSASSS scores and elevated CRP levels and four were current or former smokers (online supplemental table 5). Overall, 89.7% and 76.5% of patients had no radiographic progression at week 104 as defined by change from baseline in mSASSS <2 or ≤0, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline mean and mean change from baseline to week 104 in mSASSS*

| UPA 15 mg QD | PBO to UPA 15 mg QD | Total | |

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 7.5 (11.1) n=92 | 8.8 (12.1) n=94 | 8.1 (11.6) n=186 |

| Change from baseline to week 104 | |||

| Mean (95% CI†) | 0.6 (0.1 to 1.1) n=69 | 0.8 (0.2 to 1.4) n=67 | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.1) n=136 |

| LS mean (95% CI†) | 0.6 (0.0 to 1.2) n=69 | 0.9 (0.3 to 1.5) n=67 | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.2) n=136 |

*Data were obtained in a dedicated reading session that included baseline and week 104 images.

†95% CIs were calculated based on the t-distribution.

LS, least squares; mSASSS, modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spine Score; PBO, placebo; QD, once daily; UPA, upadacitinib.

Safety

In the 182 patients (308.6 PY) receiving upadacitinib 15 mg once daily during period 1 and/or 2, the rate of treatment-emergent AEs was 242.7/100 PY (table 2). The three most common AEs were nasopharyngitis (46 events; 14.9/100 PY), increased blood creatine phosphokinase (35 events; 11.3/100 PY), and upper respiratory tract infection (28 events; 9.1/100 PY). All but 1 of the 35 elevated creatine phosphokinase events (in 29 patients) were non-serious, and none led to study drug discontinuation. The majority were asymptomatic, and the three symptomatic patients had muscle pain due to alternative explanations, such as increased physical activity.

Table 2.

Treatment-emergent adverse events throughout the study

| Event (E/100 PY (95% CI)) | Any UPA 15 mg QD N=182 (308.6 PY) |

| AE | 749 (242.7 (225.6–260.7)) |

| Serious AE | 19 (6.2 (3.7–9.6)) |

| AE leading to discontinuation | 17 (5.5 (3.2–8.8)) |

| Infection | 246 (79.7 (70.1–90.3)) |

| Serious infection | 0 |

| Opportunistic infection excluding TB and herpes zoster* | 2 (0.6 (0.1–2.3)) |

| Active TB | 0 |

| Herpes zoster† | 5 (1.6 (0.5–3.8)) |

| Creatine phosphokinase elevation‡ | 35 (11.3 (7.9–15.8)) |

| Hepatic disorder§ | 32 (10.4 (7.1–14.6)) |

| Neutropenia¶ | 9 (2.9 (1.3–5.5)) |

| Anaemia¶ | 5 (1.6 (0.5–3.8)) |

| Lymphopenia¶ | 3 (1.0 (0.2–2.8)) |

| Malignancy** | 1 (0.3 (0.0–1.8)) |

| Adjudicated venous thromboembolic event†† | 1 (0.3 (0.0–1.8)) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease‡‡ | 1 (0.3 (0.0–1.8)) |

| Uveitis§§ | 16 (5.2 (3.0–8.4)) |

| Death | 0 |

*Two non-serious events of oesophageal candidiasis in the same patient; each event was moderate, non-serious and assessed by the investigator as having a reasonable possibility of being related to study drug. Study drug was temporarily interrupted for each event.

†Five events in four patients (three from Japan); all non-serious, mild or moderate and limited to one dermatome.

‡All but one event were non-serious, and none led to study drug discontinuation; the majority were asymptomatic, and the three symptomatic patients had muscle pain due to alternative explanations, such as increased physical activity.

§Majority based on asymptomatic alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase elevations; all were non-serious, and none led to study drug discontinuation.

¶All events were non-serious, and none led to study drug discontinuation.

**Squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue (stage IV) in 60-year-old male former smoker (approximately one pack a day for 40 years); the investigator assessed the event as having no reasonable possibility of being study drug related, and the patient discontinued the study drug. The malignancy occurred on day 146 of upadacitinib therapy.

††Pulmonary embolism in one female patient with history of thrombosis of the lower leg prior to study entry, impaired glucose tolerance, cigarette smoking, sedentary lifestyle, and obesity; assessed as not related to study drug by the investigator. The venous thromboembolic event occurred on day 568 of upadacitinib therapy.

‡‡Event of colitis with appendix swelling in 23-year-old male patient with no prior history of inflammatory bowel disease.

§§Sixteen uveitis AEs in 10 patients; 9 patients were HLA-B27 positive, 9 patients had a history of uveitis, and 15 of 16 events were mild or moderate. Most events were transient, resolved with local treatment (corticosteroid eye drop), and did not lead to interruption or discontinuation of study drug (except one patient with mild uveitis who discontinued the study); all were non-serious.

AE, adverse event; PY, patient years; QD, once daily; TB, tuberculosis; UPA, upadacitinib.

The rate of serious AEs was 6.2/100 PY, and the rate of AEs leading to discontinuation was 5.5/100 PY (table 2). No serious infections, active tuberculosis, adjudicated major adverse cardiovascular events, lymphoma, non-melanoma skin cancer, renal dysfunction, or gastrointestinal perforations were observed. One case of an adjudicated venous thromboembolic event was reported (pulmonary embolism), which led to discontinuation of study drug. This case involved a 43-year-old woman who had risk factors for thrombosis, including prior thrombosis of the lower leg, impaired glucose tolerance, cigarette smoking, sedentary lifestyle and obesity.

No new herpes zoster infections (five events overall; 1.6/100 PY), new opportunistic infections (two events of oesophageal candidiasis overall; 0.6/100 PY) or new malignancies (one event overall; 0.3/100 PY) were reported since the 1-year analysis.11 One serious event of colitis (0.3/100 PY) with appendiceal swelling was reported in a 23-year-old man with no history of IBD (table 2). One additional non-serious uveitis event was reported since the 1-year analysis, resulting in 16 events overall and an event rate of 5.2/100 PY. The uveitis events observed over 2 years occurred mostly in HLA-B27-positive AS patients who had a history of uveitis (9 of 10 patients); 15 of the 16 events were mild or moderate, and most events were transient and resolved with local treatment (corticosteroid eye-drop). One patient with mild uveitis discontinued the study. The exposure-adjusted incidence rate (n/100 PY) of uveitis was 3.3/100 PY among the total population and 0.3/100 PY among patients without history of uveitis (online supplemental table 6).

All events of neutropenia (2.9/100 PY), anaemia (1.6/100 PY) and lymphopenia (1.0/100 PY) were non-serious, and none led to study drug discontinuation. The majority of hepatic disorders were asymptomatic alanine aminotransferase (ALT, 14 events (4.5/100 PY)) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST, 10 events (3.2/100 PY)) elevations; all were non-serious and none led to study drug discontinuation.

In one patient with diagnosed Gilbert syndrome, a grade 4 (≥20 × upper limit of normal (ULN)) increase in AST and a grade 3 (≥5 × ULN) increase in ALT were associated with a grade 4 creatine phosphokinase increase triggered by intense physical exercise (for details, see online supplemental table 7). After exercise was stopped, aminotransferase and creatine phosphokinase values normalised and study drug could be restarted. One additional patient experienced a grade 3 increase in ALT, and 2 patients experienced a grade 3 increase in AST (online supplemental table 7).

No grade 3 or 4 decreases in haemoglobin or lymphocytes were observed. A total of 4 patients experienced grade 3 creatine phosphokinase elevation and five experienced a grade 4 elevation, including the patient diagnosed with Gilbert syndrome described above (online supplemental table 7). No major differences in mean haemoglobin, creatine phosphokinase, lymphocyte or neutrophil levels were observed over time (online supplemental figure 12).

Discussion

The results of the SELECT-AXIS 1 study, which is the first JAK inhibitor study with 2-year data in patients with AS, showed that upadacitinib 15 mg once daily therapy led to sustained and consistent efficacy over 2 years in both NRI and AO analyses in patients with active AS who had an inadequate response to NSAID therapy. Improvements with 2-year continuous upadacitinib therapy were consistently seen across various endpoints, including disease activity, pain, physical function, spinal mobility, quality of life, enthesitis and objective signs of inflammation as measured by CRP. In addition, clinically meaningful improvements in fatigue as measured by FACIT-F and BASDAI question 1 among patients receiving continuous upadacitinib were maintained from week 14 through weeks 52 and 104.15

These 2-year results now also include imaging data based on MRI and spinal radiographs and complement the 1-year analysis. The level of improvement of MRI inflammation (SPARCC spine and SI joints) achieved at week 14 was maintained through week 104 among patients on continuous upadacitinib, and patients who switched to upadacitinib at week 14 achieved a similar magnitude of improvement at week 104 as the continuous upadacitinib group. Of note, the baseline and week 14 MRI data from the new reading session (reading session 2) were overall consistent with the findings from reading session 1, which also included baseline and week 14 MRIs.10 Additionally, there was a low grade of spinal progression (0.7 over 2 years as measured by mSASSS), which, despite small numerical differences, is overall in line with what has been reported in more recent trials of tumour necrosis factor inhibitors and interleukin-17 inhibitors in AS.20–27

Upadacitinib was well tolerated with a total of 308.6 PY of exposure, and the overall safety findings were unchanged since the 1-year analysis and consistent with the RA and PsA upadacitinib clinical development programmes.28–30 No serious infections, active tuberculosis, adjudicated major adverse cardiovascular events, lymphoma, non-melanoma skin cancer, renal dysfunction or gastrointestinal perforations were observed. Rates of malignancy, herpes zoster and opportunistic infections were low and in line with previous studies in AS31 32 and with upadacitinib.28–30 One adjudicated venous thromboembolic event of pulmonary embolism was reported in a patient with established risk factors for thrombosis; notably, it has been reported that the risk of venous thromboembolic events is increased in patients with AS.33 The majority of the elevated creatine phosphokinase AEs were non-serious and asymptomatic, and there were no events of rhabdomyolysis. Creatine phosphokinase elevations were described with upadacitinib and have been similarly observed with the use of other JAK inhibitors.34 35 Of the 16 events of uveitis that were observed through 2 years, 1 new event was reported after the 1-year analysis. The events occurred in 10 patients, of which 9 patients had a history of uveitis. The event and incidence rates of uveitis with upadacitinib were consistent with previous studies with monoclonal tumour necrosis factor inhibitors and interleukin-17 inhibitors.36–38 In the 2-year study, one AE of colitis was reported in a young man without a history of IBD, resulting in an overall IBD event rate of 0.3/100 PY. There were no new onsets of IBD among 4 patients who entered the study with a history of IBD at baseline.

The open-label nature of period 2, lack of an active comparator and exclusion of patients with extra-musculoskeletal manifestations (ie, uveitis, IBD, psoriasis) who were not stable for at least 30 days before study entry are limitations of this study. In addition, only patients who were biological DMARD-naive were included in the study; further evaluation on the effect of upadacitinib in biologic DMARD-inadequate responders is needed, as well as a study in patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (under investigation in the ongoing SELECT-AXIS 2 study).39 Predictors of clinical response were not assessed over 2 years. Strengths of this study include that it is the first long-term (2-year) study to report a combination of clinical, imaging (including MRI and radiographs), and patient-reported outcomes in patients with AS receiving a JAK inhibitor with a low proportion of patients receiving concomitant csDMARDs. However, longer-term studies (3–4 years) assessing radiographic progression are needed to fully understand the benefits of JAK inhibitors in AS.

In conclusion, SELECT-AXIS 1 is the first study to report long-term (2-year) data in patients with active AS treated with a JAK inhibitor. Treatment with upadacitinib 15 mg once daily over 2 years showed sustained and consistent maintenance of improvements across domains relevant for AS. Upadacitinib was well tolerated, and safety results were comparable with previous upadacitinib studies. The findings of this study suggest that upadacitinib continues to have a favourable benefit–risk profile and may be a valuable treatment for patients with active AS.

Acknowledgments

AbbVie and the authors thank the patients, study sites, and investigators who participated in this clinical trial. All authors had access to relevant data and participated in the drafting, review, and approval of this publication. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship. Medical writing support was provided by Maria Hovenden, PhD, and Janet E. Matsuura, PhD, of ICON (Blue Bell, PA) and was funded by AbbVie.

Footnotes

Contributors: Study concept and design: DvdH, AD, FVdB, WM, JS, I-HS. Acquisition of data: AD, FVdB, WM, T-HK, MK. Analysis and interpretation of data: all authors. Writing of the manuscript: all authors; Maria Hovenden prepared the first draft based on author guidance. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: YS, YD. All authors had access to the data, participated in the writing and critical review of the manuscript, and approved the final version. DvdH takes responsibility for the overall content as guarantor.

Funding: AbbVie funded this study and participated in the study design, research, analysis, data collection, interpretation of data, reviewing and approval of the publication.

Competing interests: DvdH has received consultancy fees from AbbVie, Bayer, BMS, Cyxone, Eisai, Galapagos, Gilead, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma and is a Director of Imaging Rheumatology BV. AD has received research grants, consultancy fees, speaker fees, and other support (medical writing support) from Novartis and Pfizer; research grants, consultancy fees, and other support (medical writing support) from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, and UCB Pharma; research grants and consultancy fees from GlaxoSmithKline; consultancy fees and other support (medical writing support) from Janssen; consultancy fees from Aurinia, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, and MoonLake; and other support (medical writing support) from Amgen. WPM has received research grants and consultancy fees from AbbVie, Novartis, and Pfizer; and consultancy fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Galapagos, Gilead, Janssen, Lilly and UCB Pharma and is Chief Medical Officer of CARE Arthritis. JS has received consultancy and speaker fees from AbbVie, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, and UCB. FVdB has received consultancy fees and/or speaker fees from AbbVie, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma. T-HK has received speaker fees from AbbVie, Celltrion, Kirin, Lilly, and Novartis. MK has received consulting fees and/or speaker fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Asahi-Kasei Pharma, Astellas, Ayumi Pharma, BMS, Chugai, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, Novartis, Ono Pharma, Pfizer, Tanabe-Mitsubishi, and UCB Pharma. AJO has served as a consultant and/or on advisory boards for AbbVie, BMS, Roche, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB, Gilead, and Paradigm. BC has received research grants, consultancy and speaker fees from and served as a board member for AbbVie and Lilly; received consultancy fees from and served as a board member for Gilead, Galapagos, and Janssen; received consultancy fees from Celltrion; and received speaker fees from BMS, Celltrion, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche-Chugai. YS, YD and PKW are full-time, salaried employees of AbbVie Inc. and own AbbVie stock or stock options. I-HS is a full-time, salaried employee of AbbVie, owns AbbVie stock or stock options, and is an inventor on a patent application.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymised, individual and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (eg, protocols and Clinical Study Reports), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications. These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with International Council for Harmonisation guidelines and the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by an institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each study site.

References

- 1.Sieper J, Poddubnyy D. Axial spondyloarthritis. Lancet 2017;390:73–84. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31591-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stolwijk C, van Tubergen A, Castillo-Ortiz JD, et al. Prevalence of extra-articular manifestations in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:65–73. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewé R, et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:978–91. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smolen JS, Schöls M, Braun J, et al. Treating axial spondyloarthritis and peripheral spondyloarthritis, especially psoriatic arthritis, to target: 2017 update of recommendations by an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:3–17. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Heijde D, Deodhar A, Wei JC, et al. Tofacitinib in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a phase II, 16-week, randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1340–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Heijde D, Baraliakos X, Gensler LS, et al. Efficacy and safety of filgotinib, a selective Janus kinase 1 inhibitor, in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (TORTUGA): results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2018;392:2378–87. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32463-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deodhar A, Sliwinska-Stanczyk P, Xu H, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:1004–13. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fragoulis GE, McInnes IB, Siebert S. JAK-inhibitors. new players in the field of immune-mediated diseases, beyond rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2019;58:i43–54. 10.1093/rheumatology/key276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parmentier JM, Voss J, Graff C, et al. In vitro and in vivo characterization of the JAK1 selectivity of upadacitinib (ABT-494). BMC Rheumatol 2018;2:23. 10.1186/s41927-018-0031-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Heijde D, Song I-H, Pangan AL, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (SELECT-AXIS 1): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet 2019;394:2108–17. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32534-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deodhar A, van der Heijde D, Sieper J, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis and an inadequate response to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug therapy: one-year results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled study and open-label extension. Arthritis Rheumatol 2022;74:70–80. 10.1002/art.41911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Machado PM, Landewé R, Heijde Dvander, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis disease activity score (ASDAS): 2018 update of the nomenclature for disease activity states. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:1539–40. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, et al. The Assessment of Spondyloarthritis international Society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:ii1–44. 10.1136/ard.2008.104018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Machado P, Navarro-Compán V, Landewé R, et al. Calculating the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score if the conventional C-reactive protein level is below the limit of detection or if high-sensitivity C-reactive protein is used: an analysis in the DESIR cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:408–13. 10.1002/art.38921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cella D, Yount S, Sorensen M, et al. Validation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Fatigue Scale relative to other instrumentation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2005;32:811–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maksymowych WP, Inman RD, Salonen D, et al. Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada magnetic resonance imaging index for assessment of spinal inflammation in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2005;53:502–9. 10.1002/art.21337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maksymowych WP, Inman RD, Salonen D, et al. Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada magnetic resonance imaging index for assessment of sacroiliac joint inflammation in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2005;53:703–9. 10.1002/art.21445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Creemers MCW, Franssen MJAM, van't Hof MA, et al. Assessment of outcome in ankylosing spondylitis: an extended radiographic scoring system. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:127–9. 10.1136/ard.2004.020503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sieper J, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: results of a randomised placebo-controlled trial (ABILITY-1). Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:815–22. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akkoc N, Khan MA. JAK inhibitors for axial spondyloarthritis: what does the future hold? Curr Rheumatol Rep 2021;23:34. 10.1007/s11926-021-01001-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braun J, Deodhar A, Inman RD, et al. Golimumab administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks in ankylosing spondylitis: 104-week results of the GO-RAISE study. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:661–7. 10.1136/ard.2011.154799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braun J, Baraliakos X, Deodhar A, et al. Effect of secukinumab on clinical and radiographic outcomes in ankylosing spondylitis: 2-year results from the randomised phase III MEASURE 1 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1070–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sieper J, Landewé R, Rudwaleit M, et al. Effect of certolizumab pegol over ninety-six weeks in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: results from a phase III randomized trial. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:668–77. 10.1002/art.38973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Heijde D, Salonen D, Weissman BN, et al. Assessment of radiographic progression in the spines of patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with adalimumab for up to 2 years. Arthritis Res Ther 2009;11:R127. 10.1186/ar2794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van der Heijde D, Østergaard M, Reveille JD, et al. POS0918 evaluation of spinal radiographic progression in patients with radiographic axial spondyloarthritis receiving ixekizumab therapy over 2 years. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:720.1 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-eular.1620 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun J, Baraliakos X, Deodhar A, et al. Secukinumab shows sustained efficacy and low structural progression in ankylosing spondylitis: 4-year results from the MEASURE 1 study. Rheumatology 2019;58:859–68. 10.1093/rheumatology/key375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heijde Dvander, Østergaard M, Reveille JD, et al. Spinal radiographic progression and predictors of progression in patients with radiographic axial spondyloarthritis receiving ixekizumab over 2 years. J Rheumatol 2022;49:265–73. 10.3899/jrheum.210471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mease PJ, Lertratanakul A, Anderson JK, et al. Upadacitinib for psoriatic arthritis refractory to biologics: SELECT-PsA 2. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:312–20. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen SB, van Vollenhoven RF, Winthrop KL, et al. Safety profile of upadacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis: integrated analysis from the select phase III clinical programme. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:304–11. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McInnes IB, Anderson JK, Magrey M, et al. Trial of upadacitinib and adalimumab for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2021;384:1227–39. 10.1056/NEJMoa2022516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yun H, Yang S, Chen L, et al. Risk of herpes zoster in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases: implications for vaccination. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:2328–37. 10.1002/art.39670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Heijde D, Zack D, Wajdula J, et al. Rates of serious infections, opportunistic infections, inflammatory bowel disease, and malignancies in subjects receiving etanercept vs. controls from clinical trials in ankylosing spondylitis: a pooled analysis. Scand J Rheumatol 2014;43:49–53. 10.3109/03009742.2013.834961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aviña-Zubieta JA, Chan J, De Vera M, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in ankylosing spondylitis: a general population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:480–5. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smolen JS, Genovese MC, Takeuchi T, et al. Safety profile of baricitinib in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with over 2 years median time in treatment. J Rheumatol 2019;46:7–18. 10.3899/jrheum.171361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wollenhaupt J, Lee E-B, Curtis JR, et al. Safety and efficacy of tofacitinib for up to 9.5 years in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: final results of a global, open-label, long-term extension study. Arthritis Res Ther 2019;21:89. 10.1186/s13075-019-1866-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roche D, Badard M, Boyer L, et al. Incidence of anterior uveitis in patients with axial spondyloarthritis treated with anti-TNF or anti-IL17A: a systematic review, a pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Res Ther 2021;23:192. 10.1186/s13075-021-02549-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lie E, Lindström U, Zverkova-Sandström T, et al. Tumour necrosis factor inhibitor treatment and occurrence of anterior uveitis in ankylosing spondylitis: results from the Swedish biologics register. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1515–21. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindström U, Bengtsson K, Olofsson T, et al. Anterior uveitis in patients with spondyloarthritis treated with secukinumab or tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in routine care: does the choice of biological therapy matter? Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:1445–52. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.A study to evaluate efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in adult participants with axial spondyloarthritis (SELECT-AXIS 2). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04169373. Available: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04169373 [Accessed 31 Aug 2020].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2022-002280supp001.pdf (3.1MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymised, individual and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (eg, protocols and Clinical Study Reports), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications. These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.