Key Points

Question

Have prescribing patterns in dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) for secondary prevention among patients with acute ischemic stroke changed after clinical trial findings and American Heart Association/American Stroke Association practice guideline updates?

Findings

In this cohort study of 132 817 patients with acute ischemic stroke, 47.0% of patients with minor stroke received DAPT at discharge, as indicated by guidelines; 42.6% patients with nonminor stroke, for whom the risks and benefits of DAPT have not been fully established, received DAPT at discharge, with substantial hospital variation across current US practice.

Meaning

This study’s findings suggest that enhancing adherence to evidence-based DAPT practice guidelines may be a target for quality improvement in the treatment of patients with ischemic stroke.

Abstract

Importance

After the publication of the CHANCE (Clopidogrel in High Risk Patients With Acute Nondisabling Cerebrovascular Events) and POINT (Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New Transient Ischemic Attack and Minor Ischemic Stroke) clinical trials, the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) issued a new class 1, level of evidence A, recommendation for dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT; aspirin plus clopidogrel) for secondary prevention in patients with minor ischemic stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] score ≤3). The extent to which variations in DAPT prescribing patterns remain and the extent to which practice patterns in the US are consistent with evidence-based guidelines are unknown.

Objective

To evaluate the discharge DAPT prescribing patterns after publication of the new AHA/ASA guidelines and assess the extent of hospital-level variation in the use of DAPT for secondary prevention in patients with minor stroke (NIHSS score ≤3), as indicated by guidelines, and in patients with nonminor stroke (NIHSS score >3), for whom the risks and benefits of DAPT have not been fully established.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This multicenter retrospective cohort study involved 132 817 patients from 1890 hospitals participating in the AHA/ASA Get With The Guidelines–Stroke program. Patients who were hospitalized for acute ischemic stroke and prescribed antiplatelet therapy at discharge between October 1, 2019, and June 30, 2020, were included.

Exposures

Minor ischemic stroke (NIHSS score ≤3) vs nonminor ischemic stroke (NIHSS score >3).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was DAPT prescription at discharge. The extent to which variations in DAPT use were explained at the hospital level was assessed by calculating the median odds ratio (OR), which was derived using multivariable logistic regression analysis and compared the likelihood that 2 patients with identical clinical features admitted to 2 randomly selected hospitals (1 with higher propensity and 1 with lower propensity for DAPT use) would receive DAPT at discharge. Associations between hospital-level DAPT use among patients with minor vs nonminor stroke were evaluated using Pearson ρ correlation coefficients.

Results

Among 132 817 patients (median [IQR] age, 68 [59-78] years; 68 768 men [51.8%]), 4282 (3.2%) were Asian, 11 254 (8.5%) were Hispanic, 27 221 (20.5%) were non-Hispanic Black, 84 468 (63.6%) were non-Hispanic White, and 5592 (4.2%) were of other races and/or ethnicities (including American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and unable to determine). Overall, 86 551 patients (65.2%) presented with minor ischemic stroke, and 46 266 patients (34.8%) presented with nonminor ischemic stroke. After the 2019 AHA/ASA guideline updates, 40 661 patients (47.0%) with minor stroke (NIHSS median [IQR] score, 1 [0-2]) and 19 703 patients (42.6%) with nonminor stroke (NIHSS median [IQR] score, 6 [5-9]) received DAPT at discharge. Despite guideline recommendations, 45 890 patients (53.0%) with minor stroke did not receive DAPT. After accounting for patient characteristics, substantial hospital-level variations were found in the use of DAPT in those with minor stroke (median [IQR] hospital-level DAPT prescription rate, 44.8% [33.7%-57.7%]; range, 0%-91.7%; median OR, 2.03 [95% CI, 1.97-2.09]) when comparing 2 patients with identical risk factors discharged from 2 randomly selected hospitals, 1 with higher propensity and 1 with lower propensity for DAPT use. The use of DAPT in patients with nonminor stroke also varied significantly (median [IQR] hospital-level DAPT prescription rate, 41.4% [30.0%-53.8%]; range, 0%-100%; median OR, 1.90 [95% CI, 1.83-1.97]). Overall, hospitals that were more likely to prescribe DAPT for minor strokes were also more likely to prescribe DAPT for nonminor strokes (Pearson ρ = 0.72; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

This cohort study found that despite updated AHA/ASA guidelines, more than 50% of patients with minor acute ischemic stroke did not receive DAPT at discharge. In contrast, more than 40% of patients with nonminor stroke received DAPT despite lack of evidence in this setting. These findings suggest that enhancing adherence to evidence-based DAPT practice guidelines may be a target for quality improvement in the treatment of patients with ischemic stroke.

This cohort study used data from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Get With The Guidelines–Stroke registry to assess prescribing patterns for dual antiplatelet therapy at discharge among patients with minor and nonminor acute ischemic stroke.

Introduction

Long-term dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and clopidogrel is not recommended for routine secondary prevention after ischemic stroke. However, from 2013 to 2018, evidence has increasingly supported the use of short-term (21-90 days) DAPT in patients with minor ischemic stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] score ≤3) or high-risk transient ischemic attack (TIA).1,2 Based on findings from the CHANCE (Clopidogrel in High Risk Patients With Acute Nondisabling Cerebrovascular Events)1 and POINT (Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke)2 clinical trials, the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) issued a new class 1 (strong recommendation), level of evidence A (high-quality evidence from >1 randomized clinical trial [RCT], meta-analyses of high-quality RCTs, or ≥1 RCT corroborated by high-quality registry studies), recommendation for short-term use of DAPT for 21 days in patients presenting with minor noncardioembolic ischemic stroke (NIHSS score ≤3) or high-risk TIA in 2019,3 which was updated to use of DAPT for 21 to 90 days in 2021.4

Although DAPT is recommended only for specific patients with minor ischemic stroke and high-risk TIA, a recent study5 found substantial underuse of evidence-based DAPT in patients with minor ischemic stroke and potential overuse of DAPT in patients with nonminor ischemic stroke in US practice. Some variation in DAPT use may be expected based on an individual’s risk profile or preferences; however, the extent to which meaningful variations remain after accounting for patient characteristics is unknown. This information is important to develop a true understanding of the extent to which practice patterns are inconsistent with evidence-based guidelines. Therefore, we analyzed data from the AHA/ASA Get With The Guidelines–Stroke (GWTG-Stroke) registry to (1) quantify the proportion of patients with minor and nonminor acute ischemic stroke who received discharge DAPT prescriptions after the release of new AHA/ASA guideline recommendations between October 1, 2019, and June 30, 2020; (2) identify patient and hospital factors associated with DAPT use; (3) quantify the hospital-level variation in DAPT use after accounting for patient characteristics; and (4) evaluate the correlation between hospital-level DAPT use in patients with minor stroke vs nonminor stroke.

Methods

This cohort study was approved by the institutional review board of Duke University. Each participating GWTG-Stroke hospital received either human research approval to enroll patients without individual informed consent under the Common Rule6 or a waiver of authorization and exemption from subsequent review by their institutional review boards. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies.

GWTG-Stroke Registry

The GWTG-Stroke registry is an ongoing voluntary national stroke registry sponsored by the AHA/ASA. Details of GWTG-Stroke registry data collection and variable definitions have been described previously.7 In brief, trained hospital personnel use an online patient management tool to collect data on consecutive patients with ischemic stroke admitted to each participating hospital. The eligibility of each stroke admission is confirmed through medical records review. Standardized data collection includes patient demographic characteristics, medical history, medications received before admission, diagnostic testing, brain imaging, in-hospital treatment, in-hospital outcomes, and medications prescribed at discharge. The validity and reliability of data collection have been reported previously.8 IQVIA Inc (Parsippany, New Jersey) serves as the GWTG-Stroke data collection and coordination center. The Duke Clinical Research Institute serves as the GWTG-Stroke data analysis center and has an agreement to analyze the aggregate deidentified data for research purposes.

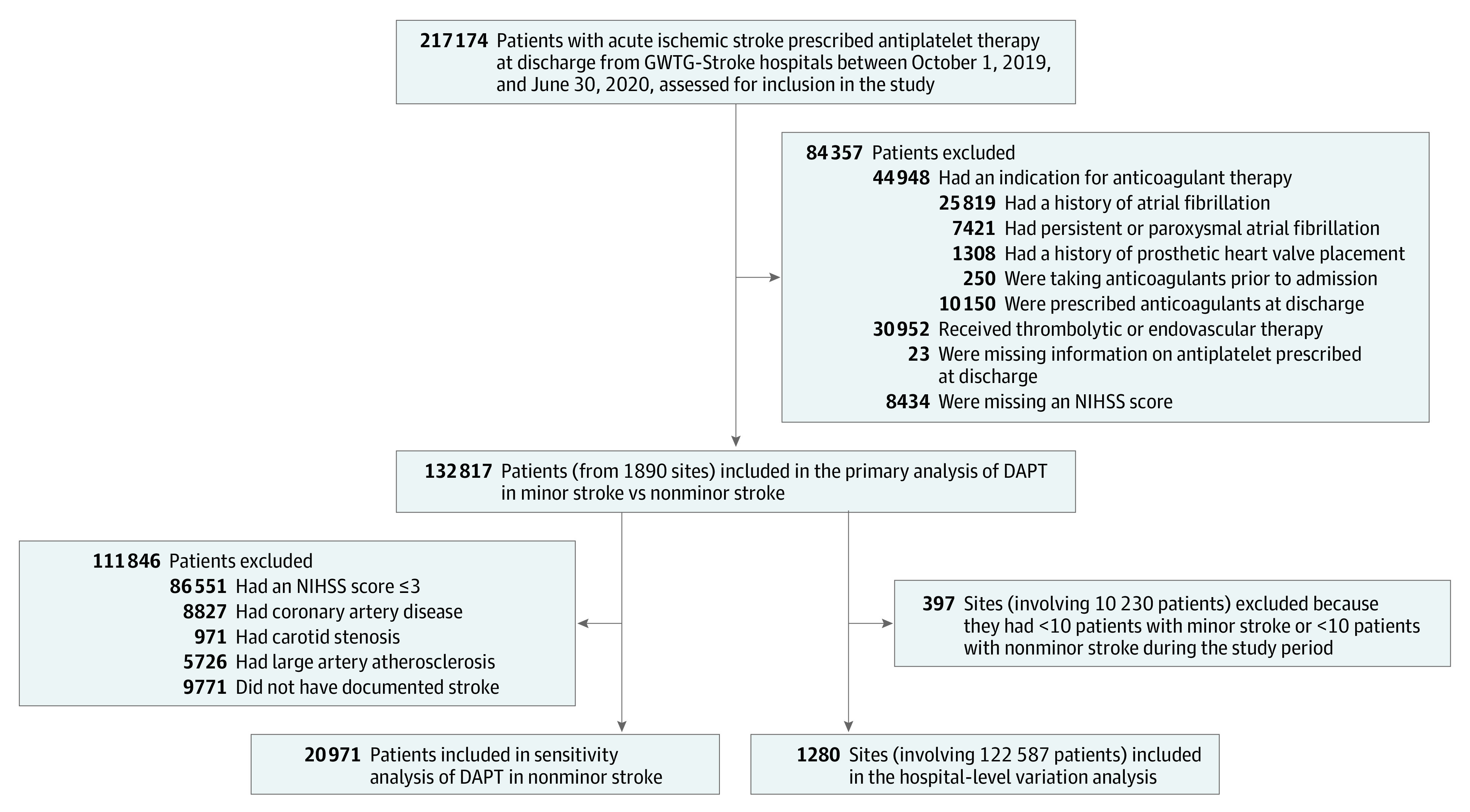

Study Population

This cohort study was a retrospective analysis of patients admitted for acute ischemic stroke and prescribed antiplatelet therapy at discharge from participating GWTG-Stroke hospitals in the US after the release of the 2019 AHA/ASA guidelines in October 20193 and before the publication of the THALES (Ticagrelor and Aspirin for Prevention of Stroke and Death) clinical trial9 in June 2020. Patients hospitalized for elective carotid intervention only, such as carotid endarterectomy or stent, and patients presenting with TIA were not included. Additional details about inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Figure 1. In brief, we excluded patients with indications for anticoagulant therapy, such as those with atrial fibrillation or a prosthetic cardiac valve, those who received anticoagulant therapy before their stroke, and those who received a prescription for an anticoagulant at discharge. We further excluded patients who received thrombolytic or endovascular therapy because these therapies were part of the CHANCE1 and POINT2 exclusion criteria and patients who were missing information on NIHSS score and the type of antiplatelet therapy prescribed at discharge.

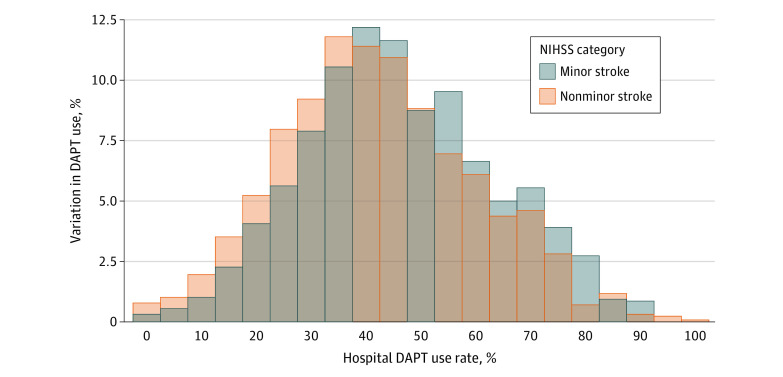

Figure 1. Study Population.

DAPT indicates dual antiplatelet therapy; GWTG-Stroke, Get With The Guidelines–Stroke program; and NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

Antiplatelet agents were categorized into 5 groups: (1) aspirin alone; (2) clopidogrel alone; (3) DAPT with aspirin and clopidogrel; (4) aspirin and dipyridamole; and (5) other antiplatelet agents, such as ticlopidine, prasugrel, or ticagrelor, either alone or in combination with aspirin. Although DAPT technically refers to a combination of any 2 antiplatelet agents, for the purposes of the current study, DAPT denoted the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel. Ticlopidine is rarely used in current clinical practice owing to a higher risk of severe adverse effects, and prasugrel is contraindicated in patients with stroke. Although the 2021 AHA/ASA secondary prevention guidelines4 issued a new class 2b (weak recommendation), level of evidence B-R (moderate-quality evidence from ≥1 RCT or meta-analyses of moderate-quality RCTs), recommendation for ticagrelor plus aspirin for patients with minor to moderate stroke (NIHSS score ≤5) after the publication of the THALES clinical trial,9 ticagrelor alone and ticagrelor plus aspirin were not commonly used during our study period. Therefore, these antiplatelet agents were grouped together in the other antiplatelet or combination therapy category.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the proportion of patients with acute ischemic stroke who were prescribed DAPT at discharge according to NIHSS score (≤3 for minor stroke and >3 for nonminor stroke). Because DAPT may be used in certain clinical circumstances, such as severe symptomatic intracranial stenosis (class 2a [moderate recommendation], level of evidence B-NR [moderate-quality evidence from ≥1 nonrandomized, observational, or registry study or meta-analyses of such studies]), acute coronary syndrome, severe carotid stenosis, or large artery atherosclerosis, we also performed a sensitivity analysis (Figure 1) involving patients presenting with nonminor stroke (NIHSS score >3) by excluding individuals with a history of coronary artery disease, carotid stenosis, or large artery atherosclerosis stroke subtype and individuals without documented stroke etiology according to the TOAST (Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment) classification method.10

To identify factors associated with DAPT use, baseline patient and hospital characteristics were compared between patients who were prescribed vs not prescribed DAPT at discharge. To obtain a more reliable estimate of hospital-level variation of DAPT use in patients with minor and nonminor stroke, a variation analysis was performed that included only hospitals with at least 10 patients hospitalized for minor stroke and at least 10 patients hospitalized for nonminor stroke during the entire study period (Figure 1). Hospital-level DAPT use was reported (minimum use, 25th percentile, median, 75th percentile, and maximum use) by minor vs nonminor ischemic stroke. We then examined the extent to which variations in DAPT use were explained at the hospital level by calculating the median odds ratio (OR), derived using multivariable logistic regression analysis, with only patient-level factors included in the model.11 Patient-level variables included in the model were age (continuous), sex (male or female), race and ethnicity (Asian, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, and other race and/or ethnicity [including American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and unable to determine]), insurance status (Medicaid, Medicare, private, or self-pay), medical history (carotid stenosis, chronic kidney insufficiency, coronary artery disease or previous myocardial infarction, diabetes, dyslipidemia, heart failure, hypertension, peripheral vascular diseases, previous stroke, previous TIA, and smoking), medications received before admission (aspirin monotherapy, clopidogrel monotherapy, DAPT, aspirin and dipyridamole combination therapy, other antiplatelet or combination therapy, or unknown), and NIHSS score (range, 0-42, with higher scores indicating greater stroke severity) at admission.

Median OR was used to measure variation between the hospital-level DAPT prescription rate that could not be explained by patient factors alone. Median OR was calculated by comparing the likelihood that 2 patients with identical clinical features admitted to 2 randomly selected hospitals (1 with higher propensity and 1 with lower propensity for DAPT use) would be discharged with a prescription for DAPT. A median OR of 1.0 indicated no variation in DAPT use between hospitals, whereas a median OR greater than 1.0 suggested greater variation in DAPT use between hospitals after accounting for patient-level differences. The associations between hospital-level DAPT use in patients with minor vs nonminor stroke were reported graphically and evaluated using Pearson ρ correlation coefficients.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). Two-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 132 817 patients with acute ischemic stroke (median [IQR] age, 68 [59-78] years; 68 768 men [51.8%] and 64 049 women [48.2%]) who were prescribed antiplatelet therapy at discharge from 1890 participating GWTG-Stroke hospitals between October 1, 2019, and June 30, 2020, were included in the primary analysis. Overall, 4282 patients (3.2%) were Asian, 11 254 (8.5%) were Hispanic, 27 221 (20.5%) were non-Hispanic Black, 84 468 (63.6%) were non-Hispanic White, and 5592 (4.2%) were of other races and/or ethnicities (including American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and unable to determine).

The distribution of antiplatelet medication prescribed at discharge for secondary stroke prevention in patients with minor and nonminor ischemic stroke is shown in Table 1. In total, 86 551 patients (65.2%) presented with minor ischemic stroke (NIHSS score ≤3), and 46 266 patients (34.8%) presented with nonminor ischemic stroke (NIHSS score >3). Among patients with minor stroke (NIHSS median [IQR] score, 1 [0-2]), the most common antiplatelet regimen was DAPT (40 661 patients [47.0%]), followed by aspirin monotherapy (39 214 patients [45.3%]) and clopidogrel monotherapy (6176 patients [7.1%]). Despite guideline recommendations, 45 890 patients (53.0%) with minor stroke did not receive DAPT at discharge. Although the risks and benefits of DAPT use in patients with nonminor stroke have not been fully established, 19 703 patients (42.6%) presenting with nonminor stroke (NIHSS median [IQR] score, 6 [5-9]) received DAPT at discharge. In the sensitivity analysis excluding individuals with coronary artery disease, carotid stenosis, large artery atherosclerosis, and/or no documented stroke etiology, 7800 of 20 971 patients (37.2%) with nonminor stroke received DAPT at discharge.

Table 1. Antiplatelet Prescription Patterns After the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association 2019 Guideline Updates.

| Antiplatelet therapy at discharge | Patients, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Minor stroke (NIHSS score ≤3) | Nonminor stroke (NIHSS score >3) | |

| Total patients, No. | 86 551 | 46 266 |

| Aspirin monotherapy | 39 214 (45.3) | 22 791 (49.3) |

| Clopidogrel monotherapy | 6176 (7.1) | 3478 (7.5) |

| DAPT (aspirin and clopidogrel) | 40 661 (47.0) | 19 703 (42.6) |

| Aspirin and dipyridamole combination therapy | 343 (0.4) | 197 (0.4) |

| Other antiplatelet or combination therapy | 157 (0.2) | 97 (0.2) |

Abbreviations: DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

Baseline characteristics of patients who were prescribed vs not prescribed DAPT at discharge, stratified by NIHSS score, are shown in Table 2. Among those with minor stroke, 40 661 patients (47.0%) were prescribed DAPT at discharge, and 45 890 (53.0%) were not. Among those with nonminor stroke, 19 703 patients (42.6%) were prescribed DAPT at discharge, and 26 563 (57.4%) were not. In general, when comparing DAPT vs no DAPT receipt among those with NIHSS scores ≤3 vs >3, male patients, non-Hispanic White patients, patients with cardiovascular risk factors, and patients receiving DAPT before their stroke were more likely to receive DAPT, regardless of NIHSS score.

Table 2. Baseline Characteristics, Stratified by NIHSS Score and DAPT Prescription at Discharge, After the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association 2019 Guideline Updates.

| Characteristic | Patients, No./total No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minor stroke (NIHSS score ≤3) | Nonminor stroke (NIHSS score >3) | |||

| Prescribed DAPT at discharge | Not prescribed DAPT at discharge | Prescribed DAPT at discharge | Not prescribed DAPT at discharge | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Total patients, No. | 40 661 | 45 890 | 19 703 | 26 563 |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 68 (59-77) | 68 (58-77) | 69 (60-78) | 69 (59-79) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 18 046/40 661 (44.4) | 22 633/45 890 (49.3) | 9439/19 703 (47.9) | 13 931/26 563 (52.4) |

| Male | 22 615/40 661 (55.6) | 23 257/45 890 (50.7) | 10 264/19 703 (52.1) | 12 632/26 563 (47.6) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| Asian | 1208/40 661 (3.0) | 1493/45 890 (3.3) | 634/19 703 (3.2) | 947/26 563 (3.6) |

| Hispanic | 3147/40 661 (7.7) | 4046/45 890 (8.8) | 1615/19 703 (8.2) | 2446/26 563 (9.2) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 6961/40 661 (17.1) | 8727/45 890 (19.0) | 4688/19 703 (23.8) | 6845/26 563 (25.8) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 27 775/40 661 (68.3) | 29 742/45 890 (64.8) | 11 876/19 703 (60.3) | 15 075/26 563 (56.8) |

| Othera | 1570/40 661 (3.9) | 1882/45 890 (4.1) | 890/19 703 (4.5) | 1250/26 563 (4.7) |

| Insurance status | ||||

| Medicaid | 4013/34 616 (11.6) | 5018/38 954 (12.9) | 3043/16 809 (18.1) | 4381/22 748 (19.3) |

| Medicare | 14 091/34 616 (40.7) | 15 271/38 954 (39.2) | 7286/16 809 (43.3) | 9603/22 748 (42.2) |

| Private | 14 656/34 616 (42.3) | 16 197/38 954 (41.6) | 5620/16 809 (33.4) | 7401/22 748 (32.5) |

| Self-pay | 1856/34 616 (5.4) | 2468/38 954 (6.3) | 860/16 809 (5.1) | 1363/22 748 (6.0) |

| NIHSS score, median (IQR) | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-2) | 6 (5-9) | 7 (5-11) |

| Medical history | ||||

| CAD or previous MI | 9064/40 661 (22.3) | 6444/45 890 (14.0) | 4666/19 703 (23.7) | 4161/26 563 (15.7) |

| Carotid stenosis | 2004/40 661 (4.9) | 1080/45 890 (2.4) | 1039/19 703 (5.3) | 679/26 563 (2.6) |

| Chronic kidney insufficiency | 3766/40 661 (9.3) | 4080/45 890 (8.9) | 2212/19 703 (11.2) | 2715/26 563 (10.2) |

| Diabetes | 16 633/40 661 (40.9) | 15 704/45 890 (34.2) | 9147/19 703 (46.4) | 10 063/26 563 (37.9) |

| Dyslipidemia | 22 377/40 661 (55.0) | 20 844/45 890 (45.4) | 10 720/19 703 (54.4) | 11 683/26 563 (44.0) |

| Heart failure | 2189/40 661 (5.4) | 2107/45 890 (4.6) | 1495/19 703 (7.6) | 1845/26 563 (6.9) |

| Hypertension | 32 053/40 661 (78.8) | 33 917/45 890 (73.9) | 16 142/19 703 (81.9) | 20 195/26 563 (76.0) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1712/40 661 (4.2) | 1123/45 890 (2.4) | 952/19 703 (4.8) | 740/26 563 (2.8) |

| Previous stroke | 9895/40 661 (24.3) | 7958/45 890 (17.3) | 7280/19 703 (36.9) | 7174/26 563 (27.0) |

| Previous TIA | 3850/40 661 (9.5) | 2885/45 890 (6.3) | 1655/19 703 (8.4) | 1687/26 563 (6.4) |

| Smoking | 8963/40 661 (22.0) | 9675/45 890 (21.1) | 4949/19 703 (25.1) | 6133/26 563 (23.1) |

| Antiplatelet therapy before admission | ||||

| Aspirin monotherapy | 13 854/40 661 (34.1) | 12 896/45 890 (28.1) | 6272/19 703 (31.8) | 7896/26 563 (29.7) |

| Clopidogrel monotherapy | 2038/40 661 (5.0) | 1331/45 890 (2.9) | 1258/19 703 (6.4) | 990/26 563 (3.7) |

| DAPT (aspirin and clopidogrel) | 5598/40 661 (13.8) | 965/45 890 (2.1) | 3505/19 703 (17.8) | 794/26 563 (3.0) |

| Aspirin and dipyridamole combination therapy | 81/40 661 (0.2) | 128/45 890 (0.3) | 43/19 703 (0.2) | 86/26 563 (0.3) |

| Other antiplatelet or combination therapy | 173/40 661 (0.4) | 494/45 890 (1.1) | 80/19 703 (0.4) | 295/26 563 (1.1) |

| Unknown | 1/40 661 (<0.1) | 12/45 890 (<0.1) | 0 | 4 (<0.1) |

| Hospital characteristics | ||||

| Beds, median (IQR), No. | 350 (225-538) | 334 (213-512) | 369 (235-562) | 369 (235-562) |

| Academic center | 30 054/40 661 (73.9) | 32 580/45 890 (71.0) | 14 863/19 703 (75.4) | 19 914/26 563 (75.0) |

| Stroke center certification | ||||

| Primary stroke center | 9057/40 661 (22.3) | 9234/45 890 (20.1) | 4965/19 703 (25.2) | 6904/26 563 (26.0) |

| Comprehensive stroke center | 22 447/40 661 (55.2) | 26 702/45 890 (58.2) | 10 328/19 703 (52.4) | 14 192/26 563 (53.4) |

| Annual ischemic stroke volume, median (IQR), No | 257 (172-393) | 245 (167-366) | 268 (183-410) | 263 (178-398) |

| Region | ||||

| Midwest | 8845/40 661 (21.8) | 9332/45 890 (20.3) | 4027/19 703 (20.4) | 5259/26 563 (19.8) |

| Northeast | 8410/40 661 (20.7) | 8755/45 890 (19.1) | 3728/19 703 (18.9) | 4689/26 563 (17.7) |

| South | 16 641/40 661 (40.9) | 19 267/45 890 (42.0) | 8624/19 703 (43.8) | 11 468/26 563 (43.2) |

| West | 6765/40 661 (16.6) | 8536/45 890 (18.6) | 3324/19 703 (16.9) | 5147/26 563 (19.4) |

| Rural | 1989/40 661 (4.9) | 2275/45 890 (5.0) | 1008/19 703 (5.1) | 1265/26 563 (4.8) |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; MI, myocardial infarction; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Other race and ethnicities include American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or unable to determine.

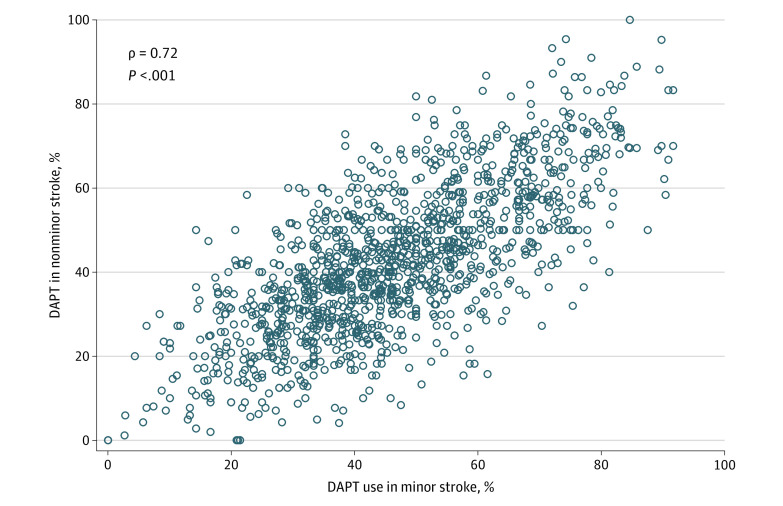

Substantial hospital-level variations were found in the proportion of DAPT use in patients with minor vs nonminor stroke. At least 57.7% of patients with minor ischemic stroke received DAPT if admitted to hospitals in the highest quartile (75th percentile to maximum) of DAPT use compared with 33.7% or fewer if admitted to hospitals in the lowest quartile (minimum to 25th percentile) of DAPT use (median hospital-level DAPT prescription rate, 44.8%; range, 0%-91.7%) (Figure 2). In other words, among hospitals in the highest quartile of DAPT use, up to 42.3% of patients with minor stroke did not receive DAPT for secondary prevention; among hospitals in the lowest quartile of DAPT use, more than 66.3% of patients with minor stroke were discharged without a prescription for DAPT. In addition, at least 53.8% of patients with nonminor stroke received DAPT at discharge if admitted to hospitals in the highest quartile of DAPT use compared with 30.0% or fewer if admitted to hospitals in the lowest quartile of DAPT use (median hospital-level DAPT prescription rate, 41.4%; range, 0%-100%). After accounting for observed patient characteristics, the median OR was 2.03 (95% CI, 1.97-2.09) for those with minor stroke. That is, if the same patient with minor ischemic stroke was randomly admitted to a hospital with a higher vs lower propensity for DAPT use, the odds of receiving DAPT were slightly more than 2.0-fold higher. The median OR for those with nonminor ischemic stroke was 1.90 (95% CI, 1.83-1.97). That is, if the same patient with nonminor ischemic stroke was randomly admitted to a hospital with a higher vs lower propensity for DAPT use, the odds of receiving DAPT (potentially inappropriately) were 1.9-fold higher. A significant positive correlation was found between hospital-level DAPT use among patients with minor stroke vs nonminor stroke (Pearson ρ = 0.72; P < .001) (Figure 3). In other words, hospitals that were more (or less) likely to prescribe DAPT to patients with minor ischemic stroke were also more (or less) likely to prescribe DAPT to patients with nonminor ischemic stroke.

Figure 2. Hospital-Level Variations in DAPT Use Among Patients With Minor Stroke and Nonminor Stroke.

DAPT indicates dual antiplatelet therapy; and NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

Figure 3. Correlation Between Hospital-Level DAPT Use Among Patients With Minor Stroke vs Nonminor Stroke.

DAPT indicates dual antiplatelet therapy.

Discussion

In this large cohort study of patients with acute ischemic stroke in the US, 53.0% of patients with minor ischemic stroke did not receive DAPT for secondary stroke prevention, even after publication of the new AHA/ASA class 1, level of evidence A, recommendation in October 2019.3 In contrast, 42.6% of patients with nonminor ischemic stroke who did not meet the CHANCE1 or POINT2 eligibility criteria received DAPT, even though the risk-benefit ratio of DAPT in such settings has not been fully established. In addition, there were substantial hospital-level variations in the use of DAPT among patients with minor vs nonminor stroke, which could not be explained by differences in patient-level factors alone. Although the NIHSS score is a major factor associated with DAPT eligibility, hospitals that were more (or less) likely to prescribe DAPT for secondary prevention in patients with minor stroke were also more (or less) likely to prescribe DAPT for secondary prevention in patients with nonminor stroke, suggesting indiscriminate prescription of DAPT or single antiplatelet agents in certain hospitals. Taken together, these findings suggest an important opportunity to improve the use of evidence-based antiplatelet therapy for secondary stroke prevention in patients with acute ischemic stroke.

Antiplatelet therapy plays an important role in secondary prevention among patients with acute ischemic stroke. The most commonly used antiplatelet agents are aspirin, clopidogrel, and DAPT with aspirin and clopidogrel. In 2004, the MATCH (Management of Atherothrombosis With Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients With Recent Transient Ischemic Attacks or Ischemic Stroke) clinical trial12 examined the use of DAPT vs clopidogrel monotherapy in patients with recent stroke and found no significant benefit to treatment with DAPT and an increased risk of major bleeding complications. After publication of the MATCH clinical trial,12 a rapid reduction in DAPT use was observed across the US.13 Unlike the MATCH study12 and other secondary prevention clinical trials,14,15,16 the CHANCE clinical trial1 assessed the use of DAPT for 21 days, and the POINT clinical trial2 assessed the use of DAPT for 90 days in patients with minor stroke (NIHSS score ≤3) or high-risk TIA; both studies demonstrated a significant benefit of DAPT, with no increase in bleeding in the CHANCE clinical trial1 but higher risk of major bleeding in the POINT clinical trial.2 In response to these findings, the AHA/ASA issued a new class 1, level of evidence A, recommendation based on the CHANCE1 and POINT2 eligibility criteria for DAPT use in patients with minor noncardioembolic ischemic stroke (NIHSS score ≤3) in 2019.3,17,18

A previous study5 reported a rapid and sustained change in DAPT use that immediately coincided with the publication of pivotal clinical trials and new AHA/ASA guideline recommendations. Although these findings suggested that changes in physician prescribing behavior occurred in response to the new knowledge,5 the translation of evidence to clinical practice has been incomplete; as many as 53.0% of patients with minor stroke in our study did not receive DAPT at discharge. On the other hand, we found increasing adoption of DAPT in patients presenting with nonminor ischemic stroke who did not meet the CHANCE1 or POINT2 eligibility criteria. Although some physicians may extend DAPT use to patients with NIHSS scores of 5 or less, intracranial large artery atherosclerosis, or severe stenosis, the risks and benefits of DAPT have not been well established.19 Given that less-intensive antiplatelet therapy may increase the risk of recurrent ischemic events, and combination therapy may increase the risk of bleeding complications,4,20 the consequences of potential underuse of DAPT in patients with minor stroke and the use of DAPT in patients with nonminor stroke need to be assessed in future research.

Some clinicians may avoid prescribing DAPT to patients with minor stroke in the presence of an allergy to aspirin or clopidogrel, a known bleeding diathesis or history of bleeding, a large territory infarction despite a low NIHSS score, a high risk of bleeding, a risk of fall, or CYP2C19 polymorphism. The use of DAPT in patients with nonminor stroke may be pursued in the setting of carotid artery stenting, recent percutaneous coronary intervention, aortic arch atherosclerosis, intracranial large artery atherosclerosis, severe symptomatic intracranial stenosis, or even patient preferences.21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 Despite a lack of evidence,19 these extenuating circumstances may represent the normal variations inherent in medical practice rather than nonadherence to guidelines. Furthermore, certain practitioners may choose to intensify antithrombotic therapy from aspirin to DAPT for patients who experience breakthrough strokes while receiving aspirin therapy.30 Although the safety and efficacy of changing from a single antiplatelet agent to DAPT have not been established,4 the present study controlled for previous stroke and previous medication receipt before hospital admission. Notably, our study findings were essentially unchanged in the sensitivity analysis excluding patients with coronary artery disease, carotid stenosis, or large artery atherosclerosis. Even if DAPT was prescribed specifically for patients with large artery atherosclerosis, DAPT is only recommended for very specific patients who have had a recent stroke associated with severe symptomatic intracranial stenosis (ie, 70%-99% stenosis; class 2a, level of evidence B-NR).4

It should be noted that support for the use of DAPT among patients with severe intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis is based on data from the CLAIR (Clopidogrel Plus Aspirin for Infarction Reduction) clinical trial,21 a post hoc analysis of the CHANCE clinical trial,31 and the SAMMPRIS (Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis) clinical trial.27 Caution is warranted when interpreting the results of the SAMMPRIS clinical trial27 because the study compared DAPT (accompanied by a suite of risk factor–modifying interventions) with percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting. A benefit to DAPT in that clinical trial27 was only inferred based on a comparison of the medical arm with historical controls. The CLAIR clinical trial21 specifically excluded individuals with more severe stroke (NIHSS score >8), and the CHANCE clinical trial31 excluded patients with NIHSS scores greater than 3. Despite a pattern of lower event rates with the use of DAPT, neither the CLAIR clinical trial21 nor an underpowered subgroup analysis of the CHANCE clinical trial31 found a statistically significant difference between the use of DAPT vs aspirin alone in terms of preventing subsequent stroke. Notably, the present study found that even if DAPT were prescribed specifically for patients with nonminor stroke who have NIHSS scores greater than 3 and NIHSS scores of 5 or less, three-quarters of DAPT use in patients with nonminor stroke occurred among those with NIHSS scores greater than 5 (median [IQR] score, 6 [5-9]). Therefore, these factors are unlikely to account for most of the DAPT use among patients with nonminor stroke observed in our data.

The rates of DAPT use in patients with minor vs nonminor stroke varied markedly at the hospital level, even after accounting for patient-level characteristics. Although some level of variation may be associated with unmeasured patient factors (allergy to aspirin or clopidogrel, known bleeding diathesis or history of bleeding, large territory infarction despite low NIHSS score, high bleeding risk, risk of fall, CYP2C19 polymorphism, carotid artery stenting, recent percutaneous coronary intervention, aortic arch atherosclerosis, intracranial large artery atherosclerosis, severe symptomatic intracranial stenosis, or patient preferences), there is no reason to believe that the proportion of such exceptional cases would vary substantially across hospitals. Even in the hospitals in the highest quartile of DAPT use, up to 42.3% of patients with minor strokes did not receive DAPT for secondary prevention, whereas in hospitals in the lowest quartile of DAPT use, more than 66.3% of patients with minor strokes were discharged without a prescription for DAPT. Notably, hospitals that were more (or less) likely to prescribe DAPT for secondary prevention in those with minor stroke were also more (or less) likely to prescribe DAPT for secondary prevention in those with nonminor stroke. Although specific recommendations for the use of DAPT exist, it appears that they were not closely followed in clinical practice, and physicians may use a one-size-fits-all approach to prescribing antiplatelet therapy for secondary stroke prevention. This substantial gap suggests that DAPT prescribing for patients with minor ischemic stroke may be used as a guideline-based performance measure, representing a compelling quality improvement target for the treatment of ischemic stroke. Furthermore, the substantial hospital variation in rates of DAPT use in patients with nonminor stroke represents gaps in knowledge and highlights the need for future clinical trials to clarify the risks and benefits of DAPT for secondary prevention in patients presenting with nonminor ischemic stroke.19 With more than 690 000 ischemic strokes occurring in the US each year,32 developing evidence-based approaches to the use of antiplatelet therapy and improving adherence to evidence-based practice guidelines would yield substantial health benefits for this vulnerable population.33

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, the study was a retrospective observational analysis. Despite containing a large number of clinical details, including medical history, previous stroke medications, and NIHSS score at presentation, the GWTG-Stroke registry does not document the reasons or specific clinical circumstances for prescribing vs not prescribing DAPT. Therefore, treatment selection and unmeasured confounding could have had consequences for the validity of study findings. Second, the current guidelines recommend that DAPT be ideally initiated within 12 to 24 hours but no later than 7 days after symptom onset and continued for 21 days. The GWTG-Stroke registry does not have information on timing of the initiation and duration of antiplatelet treatment. Although uncommon, it is possible that DAPT was initiated and discontinued for bleeding complications during hospitalization or that the length of hospital stay was longer than 21 days.

Third, our analysis focused on hospital variation in DAPT use. We were unable to analyze practitioner variation. It is likely that practitioner variation exists, even within the same hospital. Fourth, the THALES clinical trial,9 which was published in July 2020, extended the benefit of short-term DAPT with ticagrelor beyond patients with minor stroke to include a portion of patients who presented with more severe deficits (NIHSS score ≤5). The AHA/ASA subsequently issued a class 2b, level of evidence B-R, recommendation of ticagrelor plus aspirin for patients with minor to moderate stroke (NIHSS score ≤5).4 Our study was conducted before the publication of the THALES clinical trial. Neither ticagrelor nor ticagrelor plus aspirin were commonly used during our study period. Future research is needed to evaluate the impact of the THALES clinical trial9 findings for secondary stroke prevention. Fifth, our study analyzed antiplatelet prescription patterns in participating GWTG-Stroke hospitals. Despite being the largest stroke registry, covering more than three-quarters of the US population, these results might not be applicable for extrapolation to patients receiving treatment at nonparticipating GWTG-Stroke hospitals. That said, many GWTG-Stroke hospitals are large academic centers, rates of adherence to evidence-based DAPT could be lower, and hospital variation may be even larger in nonparticipating hospitals.

Conclusions

In this large cohort study using data from a national registry, a substantial proportion of patients with acute ischemic stroke did not receive appropriate antiplatelet therapy, and there were wide variations in DAPT use across hospitals nationwide. Enhancing adherence to evidence-based DAPT practice guidelines may be a target for quality improvement in the treatment of patients with ischemic stroke.

Reference

- 1.Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. ; CHANCE Investigators . Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):11-19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, et al. ; Clinical Research Collaboration, Neurological Emergencies Treatment Trials Network, and the POINT Investigators . Clopidogrel and aspirin in acute ischemic stroke and high-risk TIA. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(3):215-225. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50(12):e344-e418. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleindorfer DO, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S, et al. Guideline for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2021;52(7):e364-e467. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xian Y, Xu H, Smith EE, et al. Evaluation of evidence-based dual antiplatelet therapy for secondary prevention in US patients with acute ischemic stroke. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(5):559-564. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.0323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP). Federal policy for the protection of human subjects (‘Common Rule’). US Dept of Health & Human Services. March 18, 2016. Accessed June 16, 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/common-rule/index.html

- 7.Fonarow GC, Reeves MJ, Smith EE, et al. ; GWTG-Stroke Steering Committee and Investigators . Characteristics, performance measures, and in-hospital outcomes of the first one million stroke and transient ischemic attack admissions in Get With The Guidelines–Stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(3):291-302. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.921858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xian Y, Fonarow GC, Reeves MJ, et al. Data quality in the American Heart Association Get With The Guidelines–Stroke (GWTG-Stroke): results from a national data validation audit. Am Heart J. 2012;163(3):392-398. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston SC, Amarenco P, Denison H, et al. ; THALES Investigators . Ticagrelor and aspirin or aspirin alone in acute ischemic stroke or TIA. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(3):207-217. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams HP Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke: definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial: TOAST: trial of ORG 10172 in acute stroke treatment. Stroke. 1993;24(1):35-41. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.24.1.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larsen K, Merlo J. Appropriate assessment of neighborhood effects on individual health: integrating random and fixed effects in multilevel logistic regression. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(1):81-88. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, et al. ; MATCH Investigators . Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9431):331-337. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16721-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menon BK, Frankel MR, Liang L, et al. ; Get With The Guidelines–Stroke Steering Committee and Investigators . Rapid change in prescribing behavior in hospitals participating in Get With The Guidelines–Stroke after release of the Management of Atherothrombosis With Clopidogrel in High-risk Patients (MATCH) clinical trial results. Stroke. 2010;41(9):2094-2097. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.584151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhatt DL, Fox KAA, Hacke W, et al. ; CHARISMA Investigators . Clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(16):1706-1717. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy J, Hill MD, Ryckborst KJ, Eliasziw M, Demchuk AM, Buchan AM; FASTER Investigators . Fast assessment of stroke and transient ischaemic attack to prevent early recurrence (FASTER): a randomised controlled pilot trial. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(11):961-969. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70250-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benavente OR, Hart RG, McClure LA, Szychowski JM, Coffey CS, Pearce LA; SPS3 Investigators . Effects of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with recent lacunar stroke. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(9):817-825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(7):2160-2236. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. ; American Heart Association Stroke Council . 2018 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49(3):e46-e110. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown DL, Levine DA, Albright K, et al. ; American Heart Association Stroke Council. Benefits and risks of dual versus single antiplatelet therapy for secondary stroke prevention: a systematic review for the 2021 guideline for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2021;52(7):e468-e479. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naqvi IA, Kamal AK, Rehman H. Multiple versus fewer antiplatelet agents for preventing early recurrence after ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack. CochraneDatabase Syst Rev. 2020;8(8):CD009716. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009716.pub2https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32813275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong KSL, Chen C, Fu J, et al. ; CLAIR Study Investigators. Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus aspirin alone for reducing embolisation in patients with acute symptomatic cerebral or carotid artery stenosis (CLAIR study): a randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(5):489-497. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70060-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markus HS, Droste DW, Kaps M, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin in symptomatic carotid stenosis evaluated using Doppler embolic signal detection: the clopidogrel and aspirin for reduction of emboli in symptomatic carotid stenosis (CARESS) trial. Circulation. 2005;111(17):2233-2240. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000163561.90680.1C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Derdeyn CP, Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, et al. ; Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis Trial Investigators. Aggressive medical treatment with or without stenting in high-risk patients with intracranial artery stenosis (SAMMPRIS): the final results of a randomised trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9914):333-341. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62038-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Depta JP, Fowler J, Novak E, et al. Clinical outcomes using a platelet function–guided approach for secondary prevention in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2012;43(9):2376-2381. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.655084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greer DM. Aspirin and antiplatelet agent resistance: implications for prevention of secondary stroke. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(12):1027-1040. doi: 10.2165/11539160-0000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee M, Saver JL, Hong KS, Rao NM, Wu YL, Ovbiagele B. Antiplatelet regimen for patients with breakthrough strokes while on aspirin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2017;48(9):2610-2613. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Derdeyn CP, et al. ; SAMMPRIS Trial Investigators . Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):993-1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhatt DL, Paré G, Eikelboom JW, et al. ; CHARISMA Investigators . The relationship between CYP2C19 polymorphisms and ischaemic and bleeding outcomes in stable outpatients: the CHARISMA genetics study. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(17):2143-2150. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim D, Park JM, Kang K, et al. Dual versus mono antiplatelet therapy in large atherosclerotic stroke. Stroke. 2019;50(5):1184-1192. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.024786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lusk JB, Xu H, Peterson ED, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for stroke prevention in patients with ischemic stroke with aspirin treatment failure. Stroke. 2021;52(12):e777-e781. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.034622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu L, Wong KSL, Leng X, et al. ; CHANCE Investigators . Dual antiplatelet therapy in stroke and ICAS: subgroup analysis of CHANCE. Neurology. 2015;85(13):1154-1162. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, et al; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(9):e139-e596. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterson ED, Roe MT, Mulgund J, et al. Association between hospital process performance and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2006;295(16):1912-1920. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.16.1912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]