Significance

In bacteria, a fraction of transcriptional noise originates from promoter-like sequences found in both orientations within transcriptional units. This work shows that transcription from spurious promoters can relievegenesilencing by H-NS, a bacterial chromatin protein that oligomerizes along the DNA forming filaments and bridged structures. Upon invading a patch of oligomerized H-NS, elongating transcription complexes “unzip” the nucleoprotein filament, making the DNA accessible to regulatory proteins and RNA polymerase. In Salmonella, this mechanism triggers a positive feedback loop that activates a virulence regulatory program. The occurrence of two subpopulations of cells that, although genetically identical, either express or do not express virulence genes suggests that stochastic spurious transcription can play a role in the generation of bistability in bacteria.

Keywords: pervasive transcription, H-NS, silencing, pathogenicity islands, bistability

Abstract

In Escherichia coli and Salmonella, many genes silenced by the nucleoid structuring protein H-NS are activated upon inhibiting Rho-dependent transcription termination. This response is poorly understood and difficult to reconcile with the view that H-NS acts mainly by blocking transcription initiation. Here we have analyzed the basis for the up-regulation of H-NS–silenced Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1) in cells depleted of Rho-cofactor NusG. Evidence from genetic experiments, semiquantitative 5′ rapid amplification of complementary DNA ends sequencing (5' RACE-Seq), and chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-Seq) shows that transcription originating from spurious antisense promoters, when not stopped by Rho, elongates into a H-NS–bound regulatory region of SPI-1, displacing H-NS and rendering the DNA accessible to the master regulator HilD. In turn, HilD’s ability to activate its own transcription triggers a positive feedback loop that results in transcriptional activation of the entire SPI-1. Significantly, single-cell analyses revealed that this mechanism is largely responsible for the coexistence of two subpopulations of cells that either express or do not express SPI-1 genes. We propose that cell-to-cell differences produced by stochastic spurious transcription, combined with feedback loops that perpetuate the activated state, can generate bimodal gene expression patterns in bacterial populations.

Transcriptomic analyses of Escherichia coli bacteria exposed to an inhibitor of transcription termination factor Rho have led to the recognition that a major activity of Rho and its cofactor NusG in growing cells is devoted to genome-wide suppression of ubiquitous antisense transcription genome-wide (1, 2). Thus, indirectly, these findings are also pertinent to transcription initiation, as they unveil the existence of a high-level spurious transcriptional noise apparently curbed by the termination activity of Rho. This notion gained momentum with the demonstration that E. coli genes contain a multitude of intragenic promoters in both sense and antisense orientations (3–5). The phenomenon is particularly dramatic in genomic regions thought to originate from horizontal transfer whose typically higher adenine and thymine (AT) content matches the sequence composition of the average bacterial promoter (6). The disproportionally high number of promoter-like sequences in AT-rich DNA can actually be a source of toxicity by causing RNA polymerase titration (7). The above studies have an additional common denominator: They implicate the nucleoid structuring protein H-NS. On the one hand, the sites of intragenic Rho-dependent termination colocalized with the regions bound by H-NS (1); on the other hand, H-NS was shown to play the major role of silencing the spurious intragenic promoters (5). These findings renewed the interest in understanding the hidden complexity of H-NS–RNA polymerase interactions (8).

A small abundant protein, H-NS oligomerizes along the DNA upon binding to high-affinity AT-rich nucleation sites and spreading cooperatively to adjacent sequences through lower-affinity interactions (9–11). The oligomerization process generates a higher-order superhelical structure thought to contribute to DNA condensation (12). The resulting nucleoprotein filaments effectively coat the DNA and thereby hamper promoter recognition by RNA polymerase (13). In addition, H-NS can repress transcription through the formation of bridged or looped DNA structures that trap RNA polymerase in the open complex (14, 15) or act as roadblocks against transcript elongation (16, 17). In particular, bridged but not linear H-NS filaments have been shown to promote Rho-dependent transcription termination by increasing transcriptional pausing in vitro (17). H-NS has gained considerable attention since the discovery of its role as a xenogeneic silencer. Due to its affinity for AT-rich DNA, H-NS preferentially binds to and prevents the expression of sequences acquired through horizontal transfer (18, 19). In doing so, H-NS protects the bacterium against the toxicity of foreign DNA (7, 20, 21) and allows the evolution of mechanisms for coopting newly acquired functions and regulating their expression (22, 23). Indeed, the vast majority of H-NS–silenced genes are tightly regulated and expressed only under a limited set of conditions. Activation of H-NS–silenced genes typically results from the binding or the action of regulators able to displace H-NS (24–26). Unlike classical gene activation, H-NS countersilencing exhibits considerable flexibility in the spatial arrangement of the regulator protein relative to the promoter (27).

In Salmonella enterica, H-NS silences most of the genes that contribute to virulence, including Salmonella pathogenicity islands (SPIs) that are specifically activated in the environment of the infected host (18, 19). SPI activation occurs in the form of a hierarchical and temporal regulatory cascade that begins with the expression of SPI-1, a 44-kb island encoding a type III secretion system (T3SS) that delivers effector proteins promoting intestinal colonization and epithelial cell invasion (28, 29). Several lines of evidence suggest that the process is initiated by HilD, an SPI-1–encoded AraC-type transcriptional regulator that activates the expression of a second master regulator, HilA, which in turns activates the T3SS along with the product of a third regulatory gene, invF (30). Acting as a hub integrating diverse environmental and physiological signals, HilD is itself regulated at multiple levels including messenger RNA (mRNA) stability (31), mRNA translation (32, 33), and protein activity (33, 34). However, central to the regulatory cascade is the ability of HilD to activate its own synthesis. HilD binds to an extended region upstream of the hilD promoter in vitro (35) and in vivo (36). The presence of this region among the DNA fragments bound by H-NS in chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments suggests that HilD stimulates transcription of its own gene by antagonizing H-NS (37). Interestingly, SPI-1 exhibits a bistable expression pattern characterized by the presence of two subpopulations of cells that either express or do not express SPI-1 genes (38–43). In laboratory cultures, the SPI-1OFF population vastly predominates; however, SPI-1ON cells are continuously produced and persist for several generations (42, 44) despite the fitness cost associated with the synthesis and assembly of the T3SS, which results in growth retardation (45). Retarded growth, however, makes the SPI-1ON subpopulation tolerant to antibiotics (46). SPI-1OFF cells also benefit from bistability: Inflammation triggered by the T3SS of SPI-1ON cells leads to the production of reactive oxygen species in phagocytes. Such chemicals produce tetrathionate upon oxidation of endogenous sulfur compounds, and tetrathionate respiration confers a growth advantage to Salmonella over competing species of the intestinal microbiota (47). Furthermore, SPI-1OFF cells can invade the intestinal epithelium, a capacity that may benefit the population as a whole by countering invasion by avirulent mutants (38, 39, 42).

We recently found that inhibiting Rho-dependent transcription termination, by mutation or through the depletion of Rho cofactor NusG, causes massive up-regulation of many Salmonella virulence genes including all major SPIs (16). The magnitude and the span of these effects suggested that they were not produced locally but reflected the activation of a global regulatory response. This led us to turn our attention to HilD. The work described below confirmed the HilD involvement and provided new insight on the interplay between transcription elongation and bacterial chromatin. In particular, our data suggest that H-NS–bound regions are not completely impermeable to RNA polymerase. Occasional spurious transcription initiation events within these regions trigger a relay cascade whereby elongating transcription complexes, if not stopped by Rho, dislodge H-NS oligomers, making more promoters accessible to RNA polymerase and regulatory proteins. In addition, these findings support a model for the mechanism underlying SPI-1 bistability.

Results

Most of the Salmonella Response to NusG Depletion Is HilD-Mediated.

In all analyses described below, NusG depletion is achieved in strains with the sole copy of the nusG gene fused to a phage promoter under the control of an arabinose-inducible repressor (16). In the presence of arabinose (ARA), activation of the repressor gene causes the nusG gene to be turned off and its product to be progressively depleted. Although NusG is essential for Salmonella viability (48), the treatment is not lethal since residual NusG synthesis is sufficient to support growth. In fact, growth is nearly unaffected by ARA until bacteria enter early stationary phase. At this point the growth rate becomes significantly reduced, apparently as a side effect of the strong activation of SPIs (45).

To assess the possible role of HilD in the response to NusG depletion, we measured the expression of lacZ translational fusions to three SPI genes: invB (SPI-1) sseE (SPI-2), and sopB (SPI-5) in a hilD+ strain and in a strain in which the hilD gene is replaced by a tetRA cassette. ARA exposure elicited a sharp increase in the expression of all three fusions in both hilD+ and hilD− backgrounds; however, the changes in the hilD+ strain occurred within a range between 10- to 50-fold higher than in the ΔhilD::tetRA mutant (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), pointing to the HilD involvement in the ARA-mediated activation of SPIs. To examine this response at the single-cell level, we constructed in-frame fusions of superfolder green fluorescent protein (GFPSF) to HilD-regulated genes. Two fusions, in hilA and invB, were obtained by inserting the gfpSF open reading frame in the target gene; a third fusion, also in hilA, was made by concomitantly deleting a 28,266-bp segment spanning nearly the entire SPI-1 portion on the 3′ side of the fusion boundary. As initial experiments showed no significant differences in the behaviors of the three strains, only the strain with the 28-kb SPI-1 deletion (hilA::gfpSFΔK28) was used for subsequent analyses.

NusG Depletion Promotes SPI-1 Bistability.

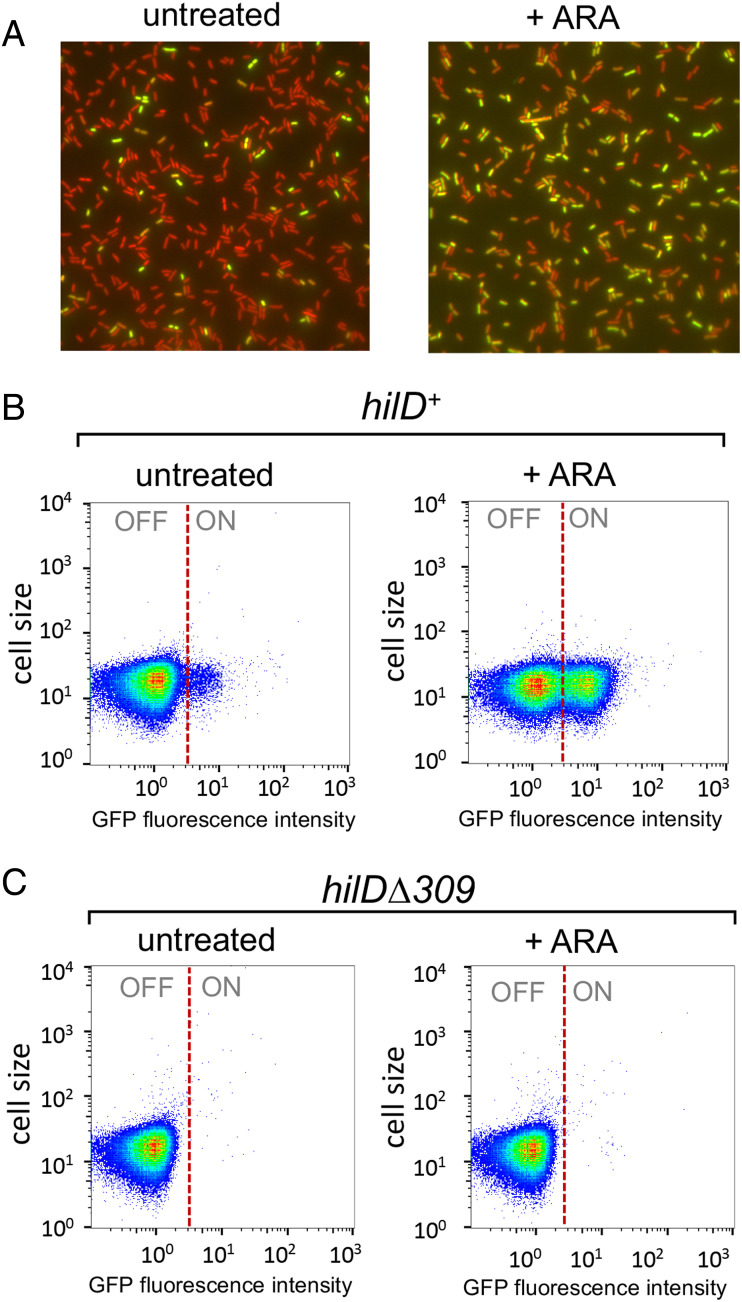

Cells carrying hilA::gfpSFΔK28 display a typical bistable phenotype characterized by the presence of two subpopulations of bacterial cells, of which only one subpopulation shows GFP fluorescence (Fig. 1A). Significantly, growth in the presence of ARA causes the ratio between hilAON and hilAOFF cells to increase dramatically in early stationary phase (Fig. 1A). Flow cytometric measurements show the increase to be more than 10-fold (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). SPI-1 bistability has been linked to the self-activating nature of hilD expression and it is thought to reflect cell-to-cell variability in HilD levels (32, 33, 41). In line with this model, hilAON cells are no longer detected in a strain carrying a 309-bp in-frame deletion removing the DNA binding motif in the carboxyl-terminal domain of HilD (Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). These results suggest that NusG depletion allows a larger fraction of cells to reach the HilD autoactivation threshold. Consistent with this conclusion, RNA quantification by RT-qPCR shows that the ARA treatment causes a large increase in hilD transcription when HilD is functional but a smaller increase in the hilDΔ309 mutant (Fig. 2A). The analysis reveals that HilD is also needed for the expression of the adjacent prgH gene (Fig. 2B). At first sight, this may seem surprising since prgH is thought to be activated by HilA, not by HilD (37, 49), and the strain used in Fig. 2B carries the hilA::gfpSFΔK28 allele which removes over two-thirds of the hilA sequence. However, we note that the fusion retains the N-terminal 112 amino acids domain of HilA previously implicated in prgH promoter recognition (50), suggesting that the HilA-GFP chimera retains the ability to activate prgH.

Fig. 1.

NusG depletion enhances HilD-dependent SPI-1 bistability. The strains used, MA14302 (hilD+) and MA14561 (hilDΔ309), carry a hilA-gfpSF translational gene fusion (hilA::gfpSFΔK28) and a chromosomal PTac promoter-mCherry gene fusion in the ARA-inducible-NusG depletion background. (A) Representative image of MA14302 cells grown at 37 °C to early stationary phase visualized by fluorescence microscopy under 100× magnification. (B and C) Representative flow cytometry analysis of cells from strains MA14302 (B) and MA14561 (C) grown as in A. The GFP fluorescence intensity distribution was examined in strains carrying gfp translational fusions. The full genotypes of MA14302 and MA14561 are shown in SI Appendix, Table S1. For the construction of hilA::gfpSFΔK28 and hilDΔ309 by λ red recombineering, DNA primers (listed in SI Appendix, Table S2) were used as detailed in SI Appendix, Table S3.

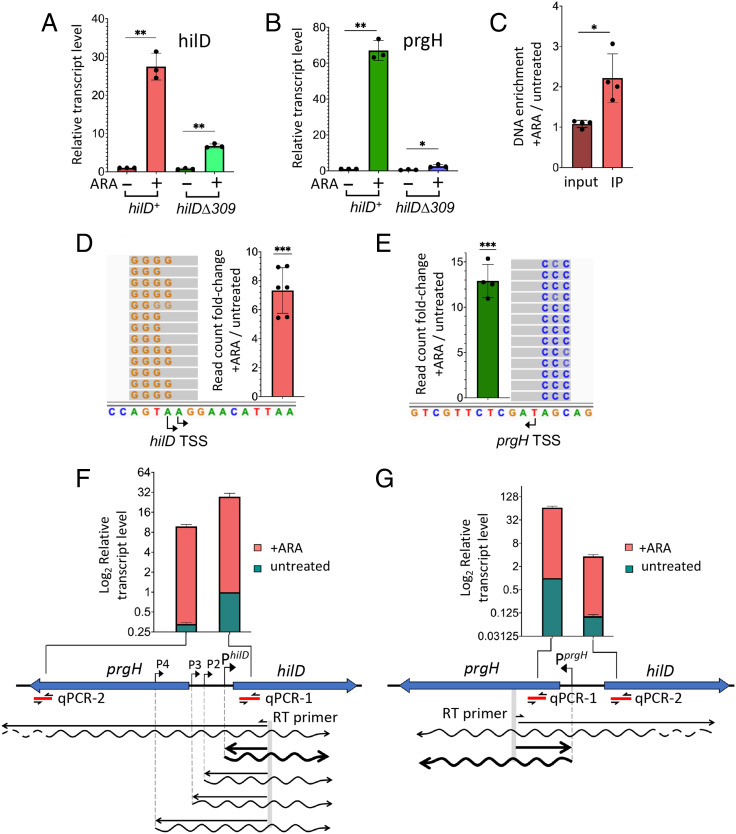

Fig. 2.

NusG depletion induces HilD-dependent activation of hilD and prgH promoters. (A and B) Quantification of hilD mRNA (A) and prgH mRNA (B) from strains MA14302 (hilD+) and MA14561 (hilDΔ309) grown to early stationary phase in the absence or in the presence of 0.1% ARA. RNA was quantified by two-step RT-qPCR. Ct values were normalized to the Ct values determined for ompA mRNA. Transcript levels are shown relative to those of untreated MA14302, set as 1. (C) Measurement of HilD protein binding to the hilD promoter. HilD-bound DNA was isolated by ChIP from strain MA14363 (carrying a chromosomal hilD-3xFLAG fusion) and quantified by real-time PCR (ChIP-qPCR). Ct values were normalized to the values of a katE gene reference. Results are presented as ratios between the values measured in cells grown in ARA-supplemented medium and the values from untreated cells. (D and E) The 5′ RACE-Seq analysis of hilD and prgH promoter activity, respectively. RNA from strain MA14302 was reverse-transcribed in the presence of a TSO. The resulting cDNA was used as template for semiquantitative PCR with primers carrying Illumina adapter sequences at their 5′ ends. Amplified DNA was subjected to high-throughput sequencing. Read counts were normalized to those measured at the ompA promoter. Results shown represent the ratios between the normalized counts from ARA-treated cells and those from untreated cells. (F and G) Contribution of distal transcription to hilD and prgH RNA levels, respectively. RNA was reverse-transcribed with primers annealing inside the promoter-proximal portion of hilD or prgH (predicted transcripts are depicted as wavy lines). The resulting cDNAs (straight lines) were used for qPCR amplification with primers annealing close to (qPCR-1) or farther away from (qPCR-2) the RT priming site. Ct values were normalized to the Ct values determined for ompA mRNA. Transcript levels are shown relative to those of untreated MA14302 cells, set as 1. All the data in this figure originate from three or more independent experiments (with error bars indicating SDs). Statistical significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student t tests with Welch’s correction for unequal variances (*P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001). In F and G, the calculated P values for the differences between untreated samples (green bars) were 0.0002 (F) and <0.0001 (G). The P values for the ARA-treated samples (red bars) were 0.0108 (F) and 0.0025 (G). The oligonucleotides used as primers in the above experiments are listed in SI Appendix, Table S4. Further experimental details are provided in Materials and Methods.

Pervasive Transcription Activates the hilD Promoter.

The central role of HilD in the response to NusG depletion was further corroborated by the observation that ARA treatment stimulates HilD binding to the hilD promoter region (Fig. 2C), a response that correlates with the activation of the hilD and prgH promoters (Fig. 2D and E). This last set of data was obtained performing semiquantitative 5′ rapid amplification of complementary DNA (cDNA) ends (5′ RACE) generated by template switching reverse transcription (51). In this method, reverse transcription is primed by a gene-specific primer and carried out in the presence of a template-switching oligonucleotide (TSO). The 5′ ends of RNAs are defined by the position the deoxycytidine repeats (typically 3 or 4) that are added by reverse transcriptase when it reaches the end of the RNA and switches to the TSO (51). Use of primers carrying Illumina adaptors for the PCR step allows for the analysis to be performed by high-throughput sequencing (RACE-Seq). Here, primers were designed to detect transcription initiation taking place at the primary hilD and prgH promoters as well as at three secondary promoters previously identified by Kröger et al. (52) (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Read summarization at each of the transcription start sites (TSSs) showed that ARA exposure causes the number of transcripts initiating at hilD and prgH primary TSSs to increase 7-fold and 13-fold, respectively (Fig. 2D and E). The most likely explanation of this effect is that NusG depletion allows transcription complexes formed outside the prgH-hilD promoter region to invade this region, displacing H-NS and triggering HilD autogenous activation. Prime suspects for this effect are the secondary hilD promoters whose activity contributes to the hilD mRNA increase (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). However, the experiment does not distinguish whether the increase in the number of reads associated with the secondary TSSs is due to a larger proportion of transcripts reaching the RT primer site (and thus susceptible to reverse transcription) in ARA-treated cells or reflects an increase in promoter activity. If the latter were true, the implication would be that the secondary promoters are themselves activated by transcription initiating elsewhere, presumably further upstream, and they relay the effect to the hilD promoter. To address this point, we performed parallel qPCR measurements using primers pairs annealing at proximal and distal positions relative to the RT priming site. Results showed that a significant fraction of transcripts entering the hilD coding sequence in ARA-treated cells initiate as far as over 1,400 bp upstream from the hilD promoter (compare red bars between PCR-1 and PCR-2 in Fig. 2F), thus considerably upstream relative to the secondary promoters. It is therefore conceivable that the elongation of these overlapping transcripts may activate the secondary promoters. Interestingly, this class of transcripts is also detectable in untreated cells (green bars in Fig. 2F) albeit at a very low level. A similar trend is observed in the opposite strand where a fraction of prgH RNAs originates from anti-sense hilD transcription (Fig. 2G).

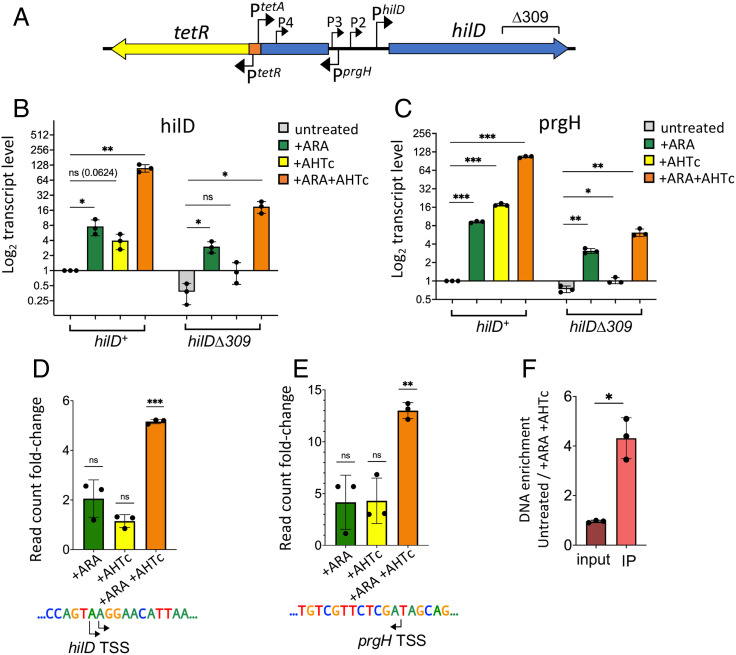

To further assess the contribution of upstream transcription to hilD promoter activity, the SPI-1 segment extending from the left boundary of the island up to a position 610 bp upstream of the hilD main TSS was deleted and replaced by a cassette comprising the tetR gene and the TetR-repressed PtetA promoter (Fig. 3A). The transcriptional responses to ARA and to the PtetA inducer, anhydrotetracycline (AHTc), alone or combined, were analyzed by RT-qPCR and 5′RACE-Seq. ARA was still able to activate transcription of hilD and prgH in the new background (Fig. 3B and C); however, activation was more moderate than seen above with the parental strain (compare to Fig. 2A and B, respectively); furthermore, no significant changes were observed at the level of the hilD and prgH primary TSSs (Fig. 3D and E). These findings corroborate the idea that the region deleted in the new construct contributes to the amplitude of the ARA effects. Activating PtetA with AHTc stimulates hilD and prgH transcription (Fig. 3B and C); here too, however, the effect remains limited and undetectable by 5′RACE-Seq at the primary TSSs (Fig. 3D and E). In contrast, when AHTc and ARA are used conjointly, transcription of both hilD and prgH genes is strongly activated (Fig. 3B and C) and an initiation burst is observed at the level of both primary promoters (Fig. 3D and E). Significantly, this burst correlates with increased occupancy of the hilD promoter by the HilD protein (Fig. 3F). The secondary promoters exhibit a similar overall response, which is, however, characterized by pronounced scatter in the individual Ara/AHTc treatments (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). The overall strength of the hilD response can be correlated with the detection of higher levels of PtetA transcription in the presence of ARA (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C).

Fig. 3.

Overlapping transcription triggers HilD-dependent activation of hilD and prgH promoters in NusG-depleted cells. (A) Schematic diagram showing the gene organization on the 5′ side of hilD in strains MA14358 (hilD+) and MA14569 (hilDΔ309). Both strains contain a tetR-PtetA cassette that replaces a 10,828-bp segment of SPI-1 and places the PtetA promoter 610 bp upstream of the main hilD TSS. (B and C) Quantification of hilD mRNA (B) and prgH mRNA (C) in cells grown to early stationary phase in the presence or absence of either ARA or AHTc, or in the presence of both. RNA was quantified by two-step RT-qPCR. Ct values were normalized to the Ct values determined for ompA mRNA. Transcript levels are shown relative to those of untreated MA14358, set as 1. (D and E) The 5′ RACE-Seq analysis of hilD and prgH promoter activity, respectively. RNA from strain MA14358 grown under the different conditions was processed as described in the legend of Fig. 2 D and E. Results shown represent the ratios between the normalized read counts from treated cells and those from untreated cells. (F) Measurement of HilD protein binding to the hilD promoter. HilD-bound DNA was isolated by ChIP from strain MA14505 (carrying a chromosomal hilD-3xFLAG fusion) and quantified by real-time PCR (ChIP-qPCR). Ct values were normalized to the values of a katE gene reference. Results are presented as ratios between the values measured in cells grown in a medium supplemented with ARA and AHTc and those from untreated cells. All the data in this figure originate from three or more independent experiments (with error bars indicating SDs). Statistical significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t tests with Welch’s correction for unequal variances (ns, P > 0.05; *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001). The oligonucleotides used as primers in the above experiments are listed in SI Appendix, Table S4.

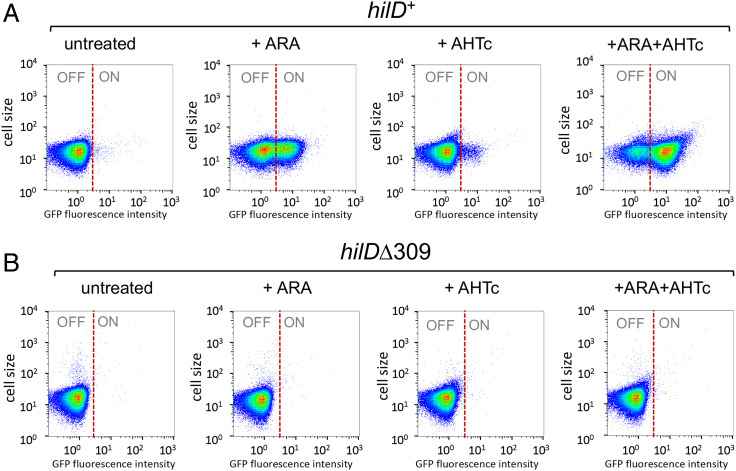

In the background of the hilA-gfpSF fusion (which deletes the right two-thirds of SPI -1), the deletion generated by the tetR-PtetA insertion constitutes a minimal system with only two SPI-1 genes, hilD and pphB, remaining intact. Significantly, this strain still exhibits the HilD-dependent bistable phenotype, suggesting that HilD is not only required but also sufficient for bistability (Fig. 4A and B). Growth in a medium supplemented with AHTc affects the basal hilAON/hilAOFF ratio only marginally unless ARA is also present, in which case the vast majority of the cell population switches to the hilAON status (Fig. 4A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S5). To confirm that the ARA effects depend on transcription originating upstream of hilD, and not by an alternative, unidentified mechanism stimulating hilD expression when NusG is depleted, we constructed a strain carrying the strong Rho-independent transcription terminator from the histidine operon attenuator region (TermhisL) immediately downstream from PtetA in the hilA::gfpSFΔK28 background (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A and B). During construction, a clone displaying strong green fluorescence on a plate supplemented with ARA and AHTc was identified. Sequence analysis revealed that this isolate harbors a deletion removing six out of the nine repeated Us at the 3′ end of TermhisL. Both the strain with the wild-type TermhisL insert and the Δ6U derivative were used for bistability assays. Results showed that TermhisL abolishes all effects of ARA on hilA OFF/ON ratios both in the absence and in the presence of AHTc (SI Appendix, Fig. S6C and E). Interestingly, the Δ6U deletion reverses this pattern, causing about half of the cell population to switch to the hilA ON status in the presence of ARA alone and virtually the entire population to switch ON in the presence of ARA and AHTc combined (SI Appendix, Fig. S6D and F). These results provide conclusive evidence that transcription originating more than 600 bp upstream of hilD’s primary TSS is solely responsible for the effects of NusG depletion on hilD expression. Since hilD secondary promoters are all located downstream from TermhisL, these data also support the idea that they play no direct role in the ARA-induced activation of the primary promoter.

Fig. 4.

Overlapping transcription promotes HilD-dependent bistability of SPI-1 expression. Strains MA14358 (hilD+) and MA14569 (hilDΔ309) carry the tetR-PtetA cassette (Fig. 3A) combined with hilA::gfpSFΔK28 and the chromosomal PTac-mCherry in the ARA-inducible-NusG depletion background. Cells grown to early stationary phase under the indicated conditions were used for single-cell analysis by flow cytometry. GFP fluorescence was measured and the distribution of hilAOFF and hilAON cells is shown in heat maps. (A) MA14358. (B) MA14569.

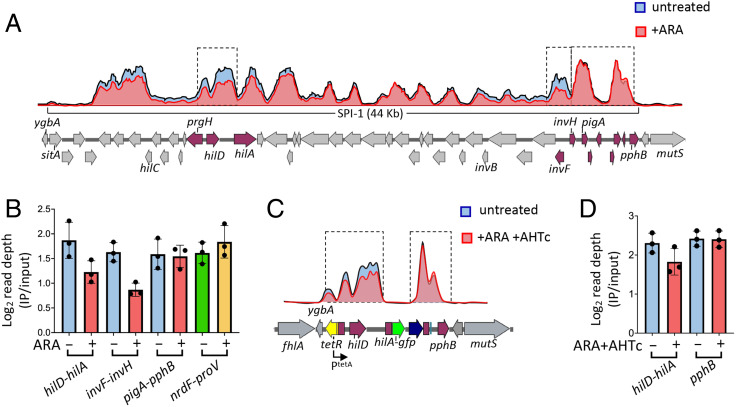

Viewing SPI-1 Up-Regulation at the Chromatin Level.

In parallel with the above studies, we sought to determine whether NusG depletion affected the binding of H-NS to SPI-1 and other genomic islands. For this purpose, ChIP coupled with high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-Seq) was performed in strains carrying the NusG-repressible allele and an epitope-tagged version of H-NS. Examination of the ChIP-Seq profiles in the SPI-1 section of the genome showed a succession of peaks and valleys consistent with the presence of multiple contiguous patches of oligomerized H-NS separated by segments with little or no H-NS bound (Fig. 5A). Superimposing the profiles from cells growing in the absence or in the presence of ARA reveals small but nonetheless appreciable differences in the levels of DNA fragments bound by H-NS. One can see that a number of peaks shrink as a result of the ARA treatment (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, the most conspicuous changes are detected in the hilD-hilA and invF-invH sections of SPI-1, corresponding to the locations of main regulatory hubs (30). In contrast, no changes are observed at the far-right end of SPI-1 [pigA-pphB segment (53)] or in the central portion of the island. Read depth quantification confirmed the profile changes. ARA treatment lowers H-NS binding in the hilD-hilA and invF-invH intervals by 34% and 47%, respectively, while having no effect in the pigA-pphB region (Fig. 5B). Likewise, no appreciable differences are observed at the proV locus (54) (Fig. 5B). ChIP-Seq analysis was also performed in the strain carrying the tetR-PtetA- and hilA::gfpSFΔK28-associated deletions, comparing unchallenged cells to cells grown in the presence of both ARA and AHTc (Fig. 5C). Somewhat surprisingly, the double treatment caused only a 20% reduction of H-NS binding in the hilD-hilA interval (Fig. 5D). In both above analyses, visual inspection of the profiles around other H-NS–bound loci known to be up-regulated in NusG-depleted cells (16) failed to reveal appreciable differences. Finding that transcriptional changes produce comparatively small or undetectable alterations in H-NS binding is not novel (24, 26) and suggests that H-NS–DNA complexes exist dynamically and rapidly reform after the passage of transcription elongation complexes.

Fig. 5.

NusG depletion affects H-NS binding to specific portions of SPI-1. (A) Representative ChIP-Seq profiles from NusG-depletable strain MA13748 (hns-3xFLAG) grown to early stationary phase in the presence or absence of 0.1% ARA. (B) Read depth quantification in the sections framed by the dashed rectangles in A and in the nrdF-proV intergenic region. Read depth values (determined by the bedcov tool of the Samtools suite) were normalized to the values from the entire genome. The results shown represent the ratios between the normalized values from IP samples and those from input DNA. (C) Representative ChIP-Seq profiles from NusG-depletable strain MA14513 (Δ[sitA-prgH]::tetR-PtetA, hilA::gfpSFΔK28, hns-3xFLAG) grown to early stationary phase in the presence or absence of ARA + AHTc. (D) Read depth quantification in the intervals framed by the dashed rectangles in C. Read depth was calculated and normalized as in B. The data in B and C represent the means from three independent ChIP-Seq experiments (with error bars indicating SDs).

Discussion

This study was aimed at understanding why impairing Rho-dependent transcription termination by depletion of Rho-cofactor NusG relieves H-NS silencing of SPIs. We show that NusG depletion triggers a positive feedback loop that generates and maintains HilD, the master regulator of the Salmonella virulence regulatory cascade. Accumulation of HilD is primarily responsible for H-NS countersilencing in NusG-depleted cells. This is directly demonstrated for SPI-1, SPI-2, and SPI-5 genes, but it seems likely that the HilD involvement may extend to most, if not all, islands and islets up-regulated in NusG-depleted cells (16). Note that although SPI-1 and SPI-2 are generally activated in response to sharply different cues, HilD-mediated cross-talk allows expression of SPI-2 genes under conditions unusual for this island, notably in rich medium (55, 56).

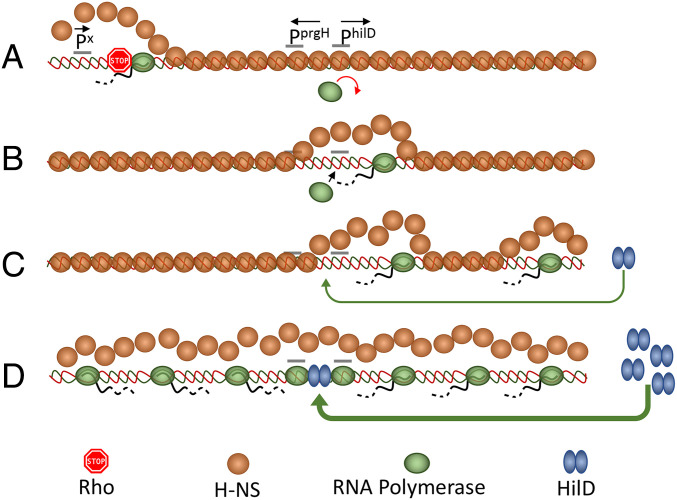

By oligomerizing along the DNA, H-NS silences not only bona fide promoters at the 5′ end of genes but also a plethora of spurious intragenic promoters that “infest” A/T-rich horizontally acquired DNA (5–7). Finding that the inhibition of Rho or NusG causes widespread sense and antisense transcription of H-NS-silenced genes (1, 16) suggests that H-NS–bound DNA is susceptible to transcriptional invasion and that Rho (recruited by NusG) acts to prevent elongation of invading transcription complexes. Various lines of evidence suggest that H-NS–bound regions are not totally impermeable to RNA polymerase. Existence of several very short transcripts initiating from within H-NS–associated loci was previously inferred from a genome-wide analysis of TSSs in E. coli (4). More recently, parallel ChIP-Seq TSS mapping experiments showed a clear TSS being used upstream of the E. coli ydbCD operon, even when H-NS was present, but no full-length mRNA (6). Finally, in our previous work, we found that a tetR-PtetA cassette placed only 57 bp away from the H-NS nucleation site in the leuO promoter region of Salmonella normally responds to AHTc induction (although leading to LeuO synthesis only when NusG is depleted) (16). Elongating through a patch of oligomerized H-NS, RNA polymerase can dislodge H-NS and allow other RNA polymerase molecules to gain access to normally silenced promoters, thus further contributing to transcriptional noise (57, 58). The data presented here show that transcriptional “noise” can be converted into a true regulatory “melody” if the activated promoter directs the synthesis of a positive autoregulator. In the model schematized in Fig. 6, we posit that a transcription complex formed at a spurious promoter (“Px”), if not stopped by Rho, “unzips” the H-NS nucleoprotein filament in the hilD promoter region, triggering a positive feedback loop that results in HilD accumulation and concomitant derepression of both hilD and prgH. Antisense transcription from inside hilD (not shown for simplicity in Fig. 6) may contribute to destabilization of the H-NS–DNA complex. Note that transcription may not need to travel all the way to the promoter sequence in order to cause H-NS dissociation. Due to the multicontact nature of the H-NS–DNA interaction (54), disruption of contacts at the edge of the oligomerization patch could be sufficient to destabilize the entire region. By linking hilD activation to a stochastic and likely infrequent transcription event—i.e., initiation at a spurious promoter or readthrough of a Rho-dependent terminator by a spurious transcript—the model can explain the bistability in the expression of HilD-regulated loci and suggests that the frequency of these events may set SPI-1 ON/OFF subpopulation ratios during normal growth. The HilD/H-NS interplay in the regulation of SPI-1 bears analogy with the mechanism regulating the expression of the locus of enterocytes effacement (LEE) of enteropathogenic E. coli. Here too, expression is characterized by a bistable response (59), suggesting that the interplay between H-NS and regulatory proteins (Ler in this case) may constitute an elemental premise for bistability. Whether LEE regulation responds to pervasive transcription is currently unknown.

Fig. 6.

Model for activation of hilD and prgH promoters by overlapping transcription. (A) A spurious transcription initiation event occurs at the edge of a patch of oligomerized H-NS (orange circles). Transcript elongation through bound H-NS is prevented by NusG-mediated recruitment of Rho factor (stop sign). (B) Occasionally, the transcript eludes Rho termination and progresses along the DNA dislodging H-NS in front of its path. This action opens a kinetic window during which RNA polymerase (green ovals) can bind to promoters that become exposed, including hilD secondary promoters (not shown) and the primary hilD promoter. (C) Activation of the hilD promoter leads to an increase in the levels of HilD protein (blue double ovals), which, upon binding to the hilD regulatory region, further stimulates hilD transcription and protein production. (D) This locks the system in a positive feedback loop: Accumulation of HilD leads to more hilD transcription and more HilD protein made. Through HilA (not shown) it also results in high-level transcription of the prgH gene. Divergent transcription further enhances the accessibility of additional spurious promoter sequences, further contributing to runaway transcription activation.

Eukaryotic genomes, including the predominant noncoding fraction of human genomes, are pervasively transcribed and this process strongly impacts gene regulation and chromatin structure (60, 61). In prokaryotes, various potential roles of pervasive antisense transcription in gene regulation and genome evolution were considered (62), but to date such roles have remained hypothetical. Data presented here show that the elongation of pervasive transcripts into H-NS–DNA complexes can act as a counter silencing mechanism modulating a regulatory response. Although most of the effects were observed under conditions of impaired transcription termination, low-level readthrough transcripts were detected in unchallenged cells, suggesting that their effects (e.g., bistability) are exerted during normal growth. This study adds elongation of pervasive transcripts to the set of mechanisms that produce transcriptional noise (63) and provides a model to understand the molecular basis of SPI-1 bistability, which has remained a long-standing mystery in Salmonella biology. The model fits well in the view that stochastic cell-to-cell differences perpetuated by feedback loops can generate phenotypic lineages (64, 65).

Materials and Methods

Strains and Culture Conditions.

All strains used in this work are derived from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain LT2 (66). Strains and their genotypes are listed in SI Appendix, Table S1. Bacteria were routinely cultured in lysogeny broth (LB: tryptone 10 g/L, yeast extract 5 g/L, NaCl, 5 g/L) at 37 °C or, occasionally, at 30 °C when carrying temperature-sensitive plasmid replicons. Typically, bacteria were grown overnight in static 2-mL cultures (14-mm-diameter tubes), subcultured by 1:200 dilution the next day (20 mL culture in 125 mL Erlenmeyer flasks) and grown with 170 rpm shaking. For growth on plates, LB was solidified by the addition of 1.5% Difco agar. When needed, antibiotics (Sigma-Aldrich) were included in growth media at the following final concentrations: chloramphenicol, 10 μg/mL; kanamycin monosulfate, 50 μg/mL; sodium ampicillin, 100 μg/mL; spectinomycin dihydrochloride, 80 μg/mL; tetracycline hydrochloride, 25 μg/mL Strains were constructed by generalized transduction using the high-frequency transducing mutant of phage P22, HT 105/1 int-201 (67) or by the λ-red recombineering technique implemented previously (68); 3xFLAG epitope fusions were constructed as described (69) or by two-step scarless recombineering. The latter procedure involved the use of tripartite selectable counter selectable cassettes (conditionally expressing the ccdB toxin gene) amplified from in-house-developed plasmid templates. Oligonucleotide used as primers for amplification (obtained from Sigma-Aldrich or Eurofins) are listed in SI Appendix, Table S2. Their assortment for the construction of the relevant alleles used in this study is shown in SI Appendix, Table S3. PCR-amplified fragments to be used for recombineering were produced with high-fidelity Phusion polymerase (New England Biolabs). Constructs were verified by colony-PCR using Taq polymerase followed by DNA sequencing (performed by Eurofins-GATC Biotech).

Fluorescence Microscopy.

Bacterial cultures grown overnight in LB at 37 °C were diluted 1:200 into 2 mL of the same medium with or without 0.1% ARA and/or 0.4 µg/mL AHTc (in 14-mm-diameter tubes) and grown for 4 h at 37 °C with shaking (170 rpm). Cells were then harvested by centrifugation (2 min at 12,000 × g), washed once in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and used immediately for microscopic examination. Images were captured with a Leica DM 6000 B microscope (CTR 6500 drive control unit) equipped with a EBQ 100 lamp power unit and filters for phase contrast, GFP, and mCherry detection (100× oil immersion objective). Pictures were taken with a Hamamatsu C11440 digital camera and processed with Metamorph software.

Flow Cytometry.

Flow cytometry was used to monitor expression of translational GFP fusions. Data acquisition was performed using a Cytomics FC500-MPL cytometer (Beckman Coulter) and data were analyzed with FlowJo X version 10.0.7r software (Tree Star, Inc.). S. enterica cultures were washed and resuspended in PBS for fluorescence measurement. Fluorescence values for 100,000 events were compared with the data from the reporterless control strain, thus yielding the fraction of ON and OFF cells.

RNA Extraction and Quantification by RT-qPCR.

Overnight bacterial cultures in LB were diluted 1:200 in the same medium—or in LB supplemented with 0.1% ARA or 0.4 µg/mL AHTc, or both drugs where appropriate—and grown with shaking at 37 °C to optical density at 600 nm (OD600) = 0.7 to 0.8. Cultures (4 mL) were rapidly spun down and resuspended in 0.6 mL ice-cold REB buffer (20 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.0, and 10% sucrose). RNA was purified by sequential extraction with hot acid phenol, phenol-chloroform 1:1 mixture and chloroform. Following overnight ethanol precipitation at −20 °C and centrifugation, the RNA pellet was resuspended in 20 µL of H2O. Three samples were prepared from independent biological replicates for each strain and condition. RNA yields, measured by Nanodrop reading, typically ranged between 2 and 3 µg/µL. The RNA preparations were used for first-strand DNA synthesis with the New England Biolabs ProtoScript II First Strand DNA synthesis kit, following the manufacturer’s specifications. Briefly, RNA (1 µg) was combined with 2 µL of a mixture of two primers (5 µM each), one annealing in the promoter proximal portion of the RNA to be quantified (primer AI41 for hilD or primer AI48 for prgH), the other annealing to a similar position in the reference RNA (primer AJ33 for ompA) in an 8 µL final volume. After 5 min at 65 °C and a quick cooling step on ice, volumes were brought to 20 µL by the addition of 10 µL of ProtoScript II Reaction Mix (2×) and 2 µL of ProtoScript II Enzyme Mix (10×). Mixes were incubated for one hour at 42 °C followed by a 5-min enzyme inactivation step at 80 °C. Samples were then used for real-time qPCR as described in SI Appendix, Supplementary Materials and Methods.

5′ RACE-Seq Analysis.

RNA 5′-end analysis was carried out by template-switching reverse transcription (51) coupled to PCR. Initially, we applied this technique on RNA pretreated with Vaccinia virus capping enzyme as reported previously (70). However, these initial tests indicated that the capping step is unnecessary; therefore, this step was subsequently omitted. From that point on, we followed the protocol described by the Template Switching RT Enzyme Mix provider (New England Biolabs) with a few modifications (SI Appendix, Supplementary Materials and Methods). The synthesized cDNA was amplified by PCR with primers carrying Illumina adapters at their 5′ ends. Several PCRs were carried out in parallel with a common forward primer (AJ38, annealing to the TSO) and a reverse primer specific for the region being analyzed and carrying a treatment-specific index sequence (see example in SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Reactions were set up according to New England Biolabs PCR protocol for Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity DNA polymerase in a final volume of 50 µL (using 1 µL of the above cDNA preparation per reaction). The number of amplification cycles needed for reproducible semiquantitative measurements, determined in trial experiments, was chosen to be 25 for the ompA reference, 30 for the primary hilD and prgH promoters, and 35 for the secondary hilD promoters and the PtetA promoter. The PCR program was as follows: activation: 98 °C for 30 s; amplification (25 or 30 or 35 cycles): 98 °C for 10 s; 65 °C for 15 s; 72 °C for 30 s; final stage: 72 °C for 5 min. Products from parallel PCRs were mixed in equal volumes; mixes originating from the amplification of separate regions were pooled and the pools subjected to high-throughput sequencing. The procedure was implemented at least once, occasionally twice, with each of the independent RNA preparations. The counts of reads containing the TSO sequence positioned at the TSSs analyzed here, each normalized to the counts of reads containing the TSO positioned at the ompA TSS, were used to calculate the ratios between the activity of a promoter under a given treatment relative and its activity in untreated cells. The raw data from RACE-Seq experiments were deposited into ArrayExpress under the accession number E-MTAB-11419.

ChIP-Seq Analysis.

Overnight bacterial cultures were diluted 1:100 in LB or in LB supplemented with 0.1% ARA or 0.1% ARA + 0.4 µg/mL AHTc and grown at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.7 to 0.8. At this point 1.6 mL of 37% formaldehyde (Alfa Aesar) were added to 30 mL of culture and the culture was incubated for 30 min at room temperature with gentle agitation. This was followed by the addition of 6.8 mL of a 2.5 M glycine solution and further 15-min incubation with gentle agitation at room temperature. Cells were centrifuged and the pellet resuspended in 24 mL of TBS buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4, and 150 mM NaCl). These steps were repeated once and the cells centrifuged again. Cells were then processed for ChIP as previously described (71) and adapted here to Salmonella (see SI Appendix, Supplementary Materials and Methods). The raw data from all ChIP-Seq experiments were deposited into ArrayExpress under the accession number E-MTAB-11386.

Statistics, Reproducibility, and Bioinformatic Analyses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Vicky Lioy for advice on ChIP experiments, to Laurent Kuras for advice on RT-qPCR experiments and to Modesto Carballo, Laura Navarro, and Cristina Reyes (Servicio de Biología, CITIUS, Universidad de Sevilla) for help with the flow cytometry analysis. We thank the High-throughput Sequencing Core Facility of the I2BC (Gif-sur-Yvette) for library preparation and sequencing (ChIP-Seq and RACE-Seq) and the ICGex NGS platform of the Curie Institute (Paris) for generating some of the sequence datasets (RACE-Seq). This study was supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-15-CE11-0024-03), and by grant PID2020-116995RB-I00 from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación ofSpain - Agencia Estatal de Investigatíon and the European Regional Fund).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See online for related content such as Commentaries.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2203011119/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

ChIP-Seq data (72) and RACE-Seq data (73) have been deposited in ArrayExpress.

References

- 1.Peters J. M., et al. , Rho and NusG suppress pervasive antisense transcription in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 26, 2621–2633 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters J. M., et al. , Rho directs widespread termination of intragenic and stable RNA transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 15406–15411 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ettwiller L., Buswell J., Yigit E., Schildkraut I., A novel enrichment strategy reveals unprecedented number of novel transcription start sites at single base resolution in a model prokaryote and the gut microbiome. BMC Genomics 17, 199 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panyukov V. V., Ozoline O. N., Promoters of Escherichia coli versus promoter islands: Function and structure comparison. PLoS One 8, e62601 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh S. S., et al. , Widespread suppression of intragenic transcription initiation by H-NS. Genes Dev. 28, 214–219 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forrest D., Warman E. A., Erkelens A. M., Dame R. T., Grainger D. C., Xenogeneic silencing strategies in bacteria are dictated by RNA polymerase promiscuity. Nat. Commun. 13, 1149 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamberte L. E., et al. , Horizontally acquired AT-rich genes in Escherichia coli cause toxicity by sequestering RNA polymerase. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 16249 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landick R., Wade J. T., Grainger D. C., H-NS and RNA polymerase: A love-hate relationship? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 24, 53–59 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorman C. J., H-NS: A universal regulator for a dynamic genome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 391–400 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorman C. J., Hinton J. C., Free A., Domain organization and oligomerization among H-NS-like nucleoid-associated proteins in bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 7, 124–128 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fang F. C., Rimsky S., New insights into transcriptional regulation by H-NS. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11, 113–120 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arold S. T., Leonard P. G., Parkinson G. N., Ladbury J. E., H-NS forms a superhelical protein scaffold for DNA condensation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 15728–15732 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ueguchi C., Mizuno T., The Escherichia coli nucleoid protein H-NS functions directly as a transcriptional repressor. EMBO J. 12, 1039–1046 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dame R. T., Wyman C., Wurm R., Wagner R., Goosen N., Structural basis for H-NS-mediated trapping of RNA polymerase in the open initiation complex at the rrnB P1. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 2146–2150 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shin M., et al. , DNA looping-mediated repression by histone-like protein H-NS: Specific requirement of Esigma70 as a cofactor for looping. Genes Dev. 19, 2388–2398 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bossi L., et al. , NusG prevents transcriptional invasion of H-NS-silenced genes. PLoS Genet. 15, e1008425 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotlajich M. V., et al. , Bridged filaments of histone-like nucleoid structuring protein pause RNA polymerase and aid termination in bacteria. eLife 4, e04970 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lucchini S., et al. , H-NS mediates the silencing of laterally acquired genes in bacteria. PLoS Pathog. 2, e81 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Navarre W. W., et al. , Selective silencing of foreign DNA with low GC content by the H-NS protein in Salmonella. Science 313, 236–238 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ali S. S., Xia B., Liu J., Navarre W. W., Silencing of foreign DNA in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 15, 175–181 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorman C. J., H-NS, the genome sentinel. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 157–161 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ali S. S., et al. , Silencing by H-NS potentiated the evolution of Salmonella. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004500 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higashi K., et al. , H-NS facilitates sequence diversification of horizontally transferred DNAs during their integration in host chromosomes. PLoS Genet. 12, e1005796 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez J. C., Latifi T., Groisman E. A., Overcoming H-NS-mediated transcriptional silencing of horizontally acquired genes by the PhoP and SlyA proteins in Salmonella enterica. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 10773–10783 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stoebel D. M., Free A., Dorman C. J., Anti-silencing: Overcoming H-NS-mediated repression of transcription in Gram-negative enteric bacteria. Microbiology (Reading) 154, 2533–2545 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Will W. R., Bale D. H., Reid P. J., Libby S. J., Fang F. C., Evolutionary expansion of a regulatory network by counter-silencing. Nat. Commun. 5, 5270 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Will W. R., Navarre W. W., Fang F. C., Integrated circuits: How transcriptional silencing and counter-silencing facilitate bacterial evolution. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 23, 8–13 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellermeier J. R., Slauch J. M., Adaptation to the host environment: Regulation of the SPI1 type III secretion system in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10, 24–29 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galán J. E., Salmonella interactions with host cells: Type III secretion at work. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 17, 53–86 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ellermeier C. D., Ellermeier J. R., Slauch J. M., Hil D., Hil C., HilD, HilC and RtsA constitute a feed forward loop that controls expression of the SPI1 type three secretion system regulator hilA in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 57, 691–705 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.López-Garrido J., Puerta-Fernández E., Casadesús J., A eukaryotic-like 3′ untranslated region in Salmonella enterica hilD mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 5894–5906 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hung C. C., et al. , Salmonella invasion is controlled through the secondary structure of the hilD transcript. PLoS Pathog. 15, e1007700 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pérez-Morales D., et al. , An incoherent feedforward loop formed by SirA/BarA, HilE and HilD is involved in controlling the growth cost of virulence factor expression by Salmonella Typhimurium. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1009630 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grenz J. R., Cott Chubiz J. E., Thaprawat P., Slauch J. M., HilE regulates HilD by blocking DNA binding in Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 200, e00750-17 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olekhnovich I. N., Kadner R. J., DNA-binding activities of the HilC and HilD virulence regulatory proteins of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 184, 4148–4160 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith C., Stringer A. M., Mao C., Palumbo M. J., Wade J. T., Mapping the regulatory network for Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium invasion. MBio 7, e01024-16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalafatis M., Slauch J. M., Long-distance effects of H-NS binding in the control of hilD expression in the Salmonella SPI1 locus. J. Bacteriol. 203, e0030821 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ackermann M., et al. , Self-destructive cooperation mediated by phenotypic noise. Nature 454, 987–990 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diard M., et al. , Stabilization of cooperative virulence by the expression of an avirulent phenotype. Nature 494, 353–356 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hautefort I., Proença M. J., Hinton J. C., Single-copy green fluorescent protein gene fusions allow accurate measurement of Salmonella gene expression in vitro and during infection of mammalian cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 7480–7491 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saini S., Ellermeier J. R., Slauch J. M., Rao C. V., The role of coupled positive feedback in the expression of the SPI1 type three secretion system in Salmonella. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001025 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sánchez-Romero M. A., Casadesús J., Contribution of SPI-1 bistability to Salmonella enterica cooperative virulence: Insights from single cell analysis. Sci. Rep. 8, 14875 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schlumberger M. C., et al. , Real-time imaging of type III secretion: Salmonella SipA injection into host cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 12548–12553 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sánchez-Romero M. A., Casadesús J., Single cell analysis of bistable expression of pathogenicity island 1 and the flagellar regulon in Salmonella enterica. Microorganisms 9, 210 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sturm A., et al. , The cost of virulence: Retarded growth of Salmonella Typhimurium cells expressing type III secretion system 1. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002143 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arnoldini M., et al. , Bistable expression of virulence genes in Salmonella leads to the formation of an antibiotic-tolerant subpopulation. PLoS Biol. 12, e1001928 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stecher B., et al. , Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium exploits inflammation to compete with the intestinal microbiota. PLoS Biol. 5, 2177–2189 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bossi L., Schwartz A., Guillemardet B., Boudvillain M., Figueroa-Bossi N., A role for Rho-dependent polarity in gene regulation by a noncoding small RNA. Genes Dev. 26, 1864–1873 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lostroh C. P., Lee C. A., The HilA box and sequences outside it determine the magnitude of HilA-dependent activation of P(prgH) from Salmonella pathogenicity island 1. J. Bacteriol. 183, 4876–4885 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Daly R. A., Lostroh C. P., Genetic analysis of the Salmonella transcription factor HilA. Can. J. Microbiol. 54, 854–860 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wulf M. G., et al. , Non-templated addition and template switching by Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV)-based reverse transcriptases co-occur and compete with each other. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 18220–18231 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kröger C., et al. , An infection-relevant transcriptomic compendium for Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium. Cell Host Microbe 14, 683–695 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lerminiaux N. A., MacKenzie K. D., Cameron A. D. S., Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1): The evolution and stabilization of a core genomic type three secretion system. Microorganisms 8, 576 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bouffartigues E., Buckle M., Badaut C., Travers A., Rimsky S., H-NS cooperative binding to high-affinity sites in a regulatory element results in transcriptional silencing. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 441–448 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bustamante V. H., et al. , HilD-mediated transcriptional cross-talk between SPI-1 and SPI-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 14591–14596 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martínez L. C., Banda M. M., Fernández-Mora M., Santana F. J., Bustamante V. H., HilD induces expression of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 genes by displacing the global negative regulator H-NS from ssrAB. J. Bacteriol. 196, 3746–3755 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rangarajan A. A., Schnetz K., Interference of transcription across H-NS binding sites and repression by H-NS. Mol. Microbiol. 108, 226–239 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wade J. T., Grainger D. C., Waking the neighbours: Disruption of H-NS repression by overlapping transcription. Mol. Microbiol. 108, 221–225 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leh H., et al. , Bacterial-chromatin structural proteins regulate the bimodal expression of the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) pathogenicity island in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. MBio 8, e00773-17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Soudet J., Stutz F., Regulation of gene expression and replication initiation by non-coding transcription: A model based on reshaping nucleosome-depleted regions: Influence of pervasive transcription on chromatin structure. BioEssays 41, e1900043 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Struhl K., Transcriptional noise and the fidelity of initiation by RNA polymerase II. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 103–105 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wade J. T., Grainger D. C., Pervasive transcription: Illuminating the dark matter of bacterial transcriptomes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 647–653 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Silva-Rocha R., de Lorenzo V., Noise and robustness in prokaryotic regulatory networks. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64, 257–275 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaern M., Elston T. C., Blake W. J., Collins J. J., Stochasticity in gene expression: From theories to phenotypes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 451–464 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sánchez-Romero M. A., Casadesús J., Waddington’s landscapes in the bacterial world. Front. Microbiol. 12, 685080 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lilleengen K., Typing of Salmonella typhimurium by means of bacteriophage. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 77, 2–125 (1948). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schmieger H., Phage P22-mutants with increased or decreased transduction abilities. Mol. Gen. Genet. 119, 75–88 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Datsenko K. A., Wanner B. L., One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6640–6645 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Uzzau S., Figueroa-Bossi N., Rubino S., Bossi L., Epitope tagging of chromosomal genes in Salmonella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 15264–15269 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu F., Zheng K., Chen H. C., Liu Z. F., Capping-RACE: A simple, accurate, and sensitive 5′ RACE method for use in prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, e129 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lioy V. S., Boccard F., Conformational studies of bacterial chromosomes by high-throughput sequencing methods. Methods Enzymol. 612, 25–45 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Figueroa-Bossi et al., Data from “Comparing the chromosome binding profiles of nucleoid structuring protein H-NS in the presence or absence of conditions eliciting the depletion of transcription termination protein NusG in Salmonella.” https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/arrayexpress/studies/E-MTAB-11386. Deposited 1 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Figueroa-Bossi et al., Data from “Measuring the effects of pervasive transcription on promoter activity in Salmonella Pathogenicity Island 1 by semiquantitative 5’RACE-Seq.” https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/arrayexpress/studies/E-MTAB-11419. Deposited 1 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

ChIP-Seq data (72) and RACE-Seq data (73) have been deposited in ArrayExpress.