Abstract

Background and aim:

The World Health Organization has placed eating disorders among the priority mental illnesses for children and adolescents given the risk they imply for their health. Recognizing the risk factors associated with this problem can serve as the basis for the design of timely and effective interventions. The objective of the study was to identify the factors associated with eating behavior in adolescents through a systematic review.

Methods:

Systematic review. Search of the literature in the bibliographic sources CINAHL, CUIDEN, Pubmed, Dialnet, SCIELO and Science Direct. The search was conducted in October and November 2020. The search terms were Eating Disorders, Food Intake, and Adolescents. The evaluation of the methodological quality was carried out using a specific guide for observational epidemiological studies. A narrative synthesis of the findings was made. Additionally, the vote counting and sign test technique was applied.

Results:

25 studies were selected. The associated factors were body dissatisfaction, female gender, depression, low self-esteem, higher BMI that increases the risk of eating disorders.

Conclusions:

a high impact of psychological factors was observed. These should be considered in the design of effective interventions to prevent this disease, although the search needs to be broadened to identify larger and more complex studies that allow for a more comprehensive review. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: adolescent, associated factors, eating behaviour, eating disorder

Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) are complex and multifactorial pathologies that affect physical and mental health and are life threatening. They are characterized by an excessive preoccupation with the weight and shape of the body or a frank deviation of the body image, accompanied by voluntary restriction of the intake or the presence of episodes of binge eating that cause great suffering, impairment of health and quality of life (1). The prevalence of eating disorders is variable; in the last two decades several studies have been carried out, especially by the National Institute of Mental Health of the United States, which has compiled cases even from European countries. The countries with the highest cases are Switzerland 12%, Chile 8.3% and Spain 6.2% (2); Colombia is followed by 4.5% (3), the United Kingdom 3.7% (2) and Portugal 3.06% (2). Countries such as the United States, Italy, Costa Rica, Mexico, Honduras, Venezuela, have numbers between 0.5% -1.5% (4, 5). Most of these disorders are more common in women and begin in adolescence, a stage of change where body image is consolidated. This in turn generates numerous crises of identity, physical appearance, friendly or sexual requirements and a struggle for autonomy, traits of perfectionism and self-demand that can lead to low self-esteem, dependence on the environment, difficulty in expressing emotions or expressing aggressiveness (6, 7).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has placed eating disorders among the priority mental illnesses for children and adolescents given the risk they imply for their health and the great psychiatric comorbidity (8). Among the most frequent, depressive disorders 23.3%, anxiety disorders 10%, adaptive disorders 3.3% and negative perception of family relationships 43.3%, which aggravate the problem and cause important complications in the state of health (7, 9). For this reason, EDs have become more relevant for the interest in the clinic, research and epidemiology (9). Various factors intervene in the occurrence of eating disorders and show a higher attributable risk such as biological, psychological, family and sociocultural (2-7). Thus, scientific evidence is abundant when addressing various aspects of eating disorders, however the state of the art revealed that in the last five years no literature review have been published on the subject, which is relevant to design or guide effective interventions that allow professionals to prevent these events. In this sense, the aim of this work was to carry out an exhaustive review of the published evidence about the factors associated with eating behaviour in adolescents.

Methods

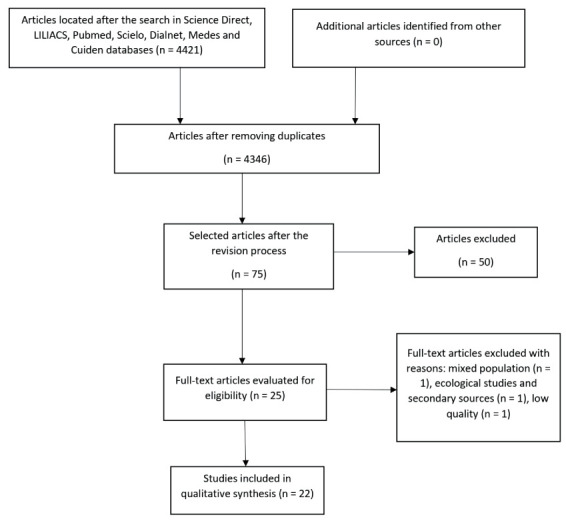

A systematic review was carried out according to the guidelines of the PRISMA (10) statement, in the bibliographic sources LILACS, CUIDEN, Pubmed, Dialnet, SCIELO and Science Direct and MEDES. The search was carried out in October and November 2020. The search terms to be used were consulted in the DECS and MESH libraries, to guarantee their standardization, in English and Spanish, they were conjugated in search equations with the Boolean operators AND and OR thus: AND factors (Eating Disorders OR Food Intake OR Eating Behavior) AND adolescent.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were selected from cohort, cross-sectional, and case control studies about factors associated with EDs in adolescents. The inclusion criteria were (a) free access articles in full text, (b) primary studies published between 2009 and 2020 to ensure that as many necessary and relevant studies as possible have been included in the review, (c) studies with a sample of adolescents aged from 10 to 19 years, according to the classification provided by the WHO (9). Dissertation, meta-analysis, review, experimental, intervention, or treatment studies were excluded, as well as studies with a mixed sample (children, adolescents, adults), and investigations without statistical information of association.

Article selection and evaluation of methodological quality

The selection of the articles was carried out in 4 phases. First, title and abstract were read to determine the suitability of the study and elimination of duplicates. Second, full text was read and the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. Third, a reverse and forward search was performed on the included studies to locate as many documents as possible. Fourth, the risk of bias was assessed through critical reading based on the Critical Reading Guide for Observational Studies in Epidemiology (11, 12). A guide to assess cross-sectional studies was used (11). This instrument included 31 items that allow for minimizing biases and the confounding effect of internal validity. It was evaluated qualitatively using MB: very good, B: good, A: regular, and NI: does not report. A second guide was used to assess cohort studies and case-control studies (12). The instrument included 21 items and evaluated qualitatively the followings aspects: selection of subjects, validation of question, evaluation of the final outcomes, confounding factors, statistical analysis, general evaluation of the study, and description of the study, using A: adequately, B: partially, C: improperly, and D: I don’t know. This process was carried out by the first author and was audited by the other authors.

Data extraction

The data were consolidated through a structured booklet in Excel based on two types of information: (i) information about articles’ characteristics such as study sample, main author, year of publication, language, country, design; (ii) information about eating disorder risk factors such as biological, psychological, sociocultural, and family factors.

Data analysis

The information was treated qualitatively and analysed in a narrative way. The results were organized in tables and figures according to the PRISMA statement. Additionally, the found results exceeded the number of 20 articles, so the vote counting technique was applied. Such a technique consisted in granting a positive vote for studies with a statistically significant relationship between a risk factor and EDs, and a negative vote when there was no significant association. Subsequently, the sign test (13, 14) was applied to determine if the difference in the number of positive studies was significantly greater than the opposite result. A significance value was established to be less than 0.05. It is important to notice that these techniques are limited but they can help to guide the results of the review in the absence of meta-analysis (14).

Fig 1.

General diagram of the study

Results

Methodological quality assessment

About the cross-sectional studies, 54.5% (n = 12) obtained high methodological quality, 27.2% (n = 7) medium quality, and 4.6% (n = 1) low methodological quality. This study was excluded by the revision. With regard to the cohort studies, it was assumed that studies with adequate rating in 23-26 items were considered to be of high methodological level; medium level was attributed to studies with adequate rating in 19-22 items, and low methodological level was attributed to studies with adequate rating in 18 items or less. In this sense, 100% (n = 3) of the cohort studies obtained a medium methodological quality (Tab. 1 and Tab. 2).

Tab 1.

Critical reading and assessment of methodological quality for cross-sectional studies.

| Main author, year and country | Study type | Participants (sample is adequate and similar to the general population, minimizing the probability of selection bias) | Statistical analysis and confusion (analysis is adequate and the possibility of confusion is minimized) | Summary assessment | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | Internal validity (study design allows minimizing biases and the confounding effect | Overall study quality (quality of the evidence provided by the study): | ||

| Esteban, Et al, 2014, Spain (15) | Cross-sectional | B | MB | MB | NA | B | MB | B | B | B | high | high |

| Shahyad, Et al, 2018, Israel (16) | Cross-sectional | MB | B | B | MB | R | B | B | NA | B | high | medium |

| Yirga, Et al, 2016, Ethiopia (17) | Cross-sectional | MB | MB | MB | MB | B | B | B | B | B | high | high |

| Altamirano, Et al, 2011, Mexico (18) | Cross-sectional | MB | MB | MB | MB | B | B | MB | R | B | high | high |

| Fuentes, Et al, 2015, Spain (19) | Cross-sectional | MB | MB | MB | MB | B | MB | B | B | B | high | high |

| Lazo, Et al, 2015, Peru (20) | Analytical Cross-Sectional | MB | MB | MB | MB | B | MB | MB | MB | B | high | high |

| Moreno, Et al, 2017, Colombia (21) | Descriptive Cross-sectional | B | B | MB | B | B | B | B | B | B | high | high |

| Nuño, Et al, 2009, Mexico (22) | Analytical Cross-Sectional | B | B | MB | B | B | B | MB | MB | MB | high | high |

| Quiles, Et al, 2014, Spain (2. 3) | Cross-sectional | MB | MB | MB | MB | MB | MB | MB | MB | MB | high | high |

| Silva, Et al, 2017, Mexico (24) | Cross-sectional | MB | MB | MB | MB | MB | B | B | B | B | high | high |

| Sousa, Et al, 2013, Brazil (25) | Cross-sectional | B | B | MB | MB | MB | MB | MB | B | B | high | high |

| Cogollo, Et al, 2012, Colombia (26) | Cross-Sectional Analytical Observational | B | B | MB | MB | MB | MB | MB | B | B | high | high |

| Caldera, Et al, 2019, Mexico (27) | Cross-sectional | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | NA | B | medium | medium |

| Reina, Et al, 2013, USA (28) | Cross-sectional | B | B | R | NA | B | B | B | NA | B | medium | medium |

| Laporta, Et al, 2020, Spain (29) | Cross-sectional Quantitative, Descriptive, Retrospective | B | MB | B | B | B | B | B | B | NI | medium | medium |

| Vara, Et al, 2011, Spain (30) | Cross-sectional | B | B | B | B | R | R | B | B | B | medium | medium |

| Sousa, Et al, 2014, Spain (31) | Cross-sectional | B | B | MB | B | B | R | B | R | R | medium | medium |

| Castaño, Et al, 2012, Colombia (32) | Cross-sectional | B | NI | B | B | R | B | B | R | B | medium | medium |

| Rutsztein, Et al, 2014, Argentina (33) | Cross-sectional, Descriptive | B | R | B | R | R | R | B | R | B | Low | Low |

Note. Internal validity. It defines whether the study design allows minimizing biases and the confounding effect (12).

The Items used were:

2. The inclusion and exclusion criteria of participants are indicated, as well as the sources and selection methods.

3. The selection criteria are adequate to answer the question or the objective of the study.

4. The study population, defined by the selection criteria, contains an adequate spectrum of the population of interest.

5. An estimate was made of the size, the level of confidence or the statistical power of the sample to estimate the measures of frequency or association that the study intended to obtain.

6. The number of potentially eligible people is reported, those initially selected, those who accept and those who finally participate or respond; fifteen. Statistical analysis was determined from the beginning of the study.

16. The statistical tests used are specified and appropriate

17. Participant losses, lost data or others were correctly treated

18. The main possible confounding elements were taken into account in the design and in the analysis.

Assessment: MB=very good; B=good; R=regular; NA=not applicable; NI=no information.

Tab 2.

Critical reading and assessment of methodological quality for cohort studies.

| Main author, year and country | Study type | Question validity | Selection of subjects | Evaluation | Confounding factors | Statistic analysis | Overall rating of the study | Study description | Summary assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium | |||||||||

| Haynos, Et al, 2016, Spain (3, 4) | Cohort | A | A | A | A | A | B | A | Yes |

| Maezono, Et al, 2019, Japan / Finland (35) | Cohort | D | B | B | A | A | B | B | Yes |

| Batista, Et al, 2018, Croatia (36) | Cohort | B | A | B | A | A | B | B | Yes |

Note. Cohort studies allow a direct determination of relative risk and allow calculation of the interval between exposure or risk factor and overall study disease (12). It was scored according to the validity of the question, selection of subjects, evaluation, confounding factors, statistical analysis, general assessment and description of the study. Rating: according to the author, the items were rated as follows: A: adequately; B: partially; C: improperly; D: I don’t know. For the purposes of this review, it was assumed that studies with adequate rating in 23-26 items were considered to be of high methodological level; medium level was attributed to studies with adequate rating in 19-22 items, and low methodological level was attributed to studies with adequate rating in 18 items or less.

Characteristics of the studies

Among the selected studies, 86.4% (n = 19) were cross-sectional design (15─33), 13.6% (n = 3) were cohort studies (34─36). Fifty-percent (n = 11) of the studies were conducted in Latin America (18, 20─22, 24─27, 31─33), 31.8% (n = 7) in Europe (15, 19, 23, 29, 30, 33, 34), 9% (n = 2) in Asia (16, 34) 4.6% (n = 1) in Africa (17), and 4,6% (n = 1) in North America (28) (Tab. 3).

Tab 3.

Synthesis of the studies included in the review.

| Main Author, Year and Country | Type of study | Population | Instrument | Family Factors | Biological factors | Sociocultural factors | Psychological factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esteban, Et al, 2014, Spain. (15) | Cross-sectional | 2,077 native Spanish and immigrant subjects from 13 to 17 years old. | SCOFF Eating Disorders Questionnaire. | Does not inform | Does not inform | Risk: immigrant adolescents living in the Madrid region and immigrant women. | Does not inform |

| Shahyad, Et al, 2018, Israel. (16) | Cross-sectional | 477 high school students aged 15 and 17. | Inventory of eating disorders. | Does not inform | Does not inform | Risk: Thin ideal internalization | Risk: Body dissatisfaction |

| Yirga, Et al, 2016, Ethiopia. (17) | Cross-sectional | 836 high school students between the ages of 12 and 19. | Eating Attitude Test-26 (EAT-26) | Risk: educational level of the mother | Risk: Being a woman. | Does not inform | Does not inform |

| Altamirano, Et al, 2011, Mexico.CO (18) | Cross-sectional | 1,982 women between the ages of 15 and 19 | Brief Questionnaire of Risky Eating Behaviors (CBCAR) | Does not inform | Does not inform | Does not inform | Risk: dissatisfaction with body image and low self-esteem. |

| Fuentes, Et al, 2015, Spain. (19) | Cross-sectional | 368 between 13 and 17 years | Body Image Dissatisfaction Assessment Scale. | Risk: Authoritarian and negligent family styles, family socialization styles and dissatisfaction with body image. | Does not inform | Does not inform | Does not inform |

| Lazo, Et al, 2015, Peru. (20) | Analytical cross-sectional | 483 female students between 12 and 17 years old. | Eating attitude test (EAT-26). | Does not inform | Does not inform | Risk: influence of the media. | Does not inform |

| Moreno, Et al, 2017, Colombia. (21) | Cross-sectional correlation | 104 students between 13 to 18 years old | Abbreviated Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26). Eating behavior questionnaire (FBQ). | Risk: Parental educational levels | Risk: female gender | Does not inform | Risk: Dissatisfaction with adolescent body image and concern about weight. |

| Nuño, Et al, 2009, Mexico. (22) | Analytical cross-sectional | 1,134 male and female adolescents. | Brief Questionnaire of Risky Eating Behaviors | Does not inform | Risk: being a woman | Does not inform | Risk: impulsivity, suicidal ideation and stress |

| Quiles, Et al, 2014, Spain. (23) | Cross-sectional | 2,142 male and female adolescents. | Eating Attitude Test (EAT-40). | Does not inform | Does not inform | Does not inform | Risk: self-oriented perfectionism. |

| Silva, Et al, 2017, Mexico. (24) | Cross-sectional | 392 women between the ages of 13 and 18. | Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-40) | Does not inform | Does not inform | Risk: belonging to the municipality of Pungarabato | Risk: submission |

| Sousa, Et al, 2013, Brazil. (25) | Cross-sectional | 580 adolescents of both sexes from 10 to 19 years | Food Attitudes Test Questionnaire (COMER-26) The EAT-26. Body shape quiz | Does not inform | Risk: fat percentage | Does not inform | Risk: dissatisfaction with body image |

| Cogollo, Et al, 2012, Colombia. (26) | Analytical cross-sectional | 2625 students between 10 and 20 years old | SCOFF questionnaire. | Does not inform | Risk: female | Does not inform | Risk: clinically important depressive symptoms and problematic alcohol use. |

| Caldera, Et al, 2019, Mexico. (27) | Cross-sectional | 988 adolescents of both sexes between 14 and 18 years old. | Brief Questionnaire of Risky Eating Behaviors (CBCAR). | Does not inform | Does not inform | Does not inform | Risk: Body dissatisfaction. |

| Reina, Et al, 2013, USA (28) | Cross-sectional | 90 adolescents from 13 to 17 years old | Infant Feeding Questionnaire (CFQ) | Does not inform | Risk: being a woman | Does not inform | Risk: Orientation to Appearance, concern about being overweight and eating in the absence of hunger. |

| Laporta, Et al, 2020, Spain. (29) | Descriptive Cross-sectional | 100 patients diagnosed with eating disorders according to DSM-IV-TR, aged between 13 and 16 years. | Eating Disorders Inventory-3, EDI-3. | Does not inform | Risk: being a woman | Does not inform | Risk: High perfectionism, greater severe depressive symptoms, body dissatisfaction and lower self-esteem. |

| Vara, Et al, 2011, Spain. (30) | Cross | 158 adolescents of both sexes. | Attitude test towards eating (EAT-26) | Does not inform | Risk: increased BMI. | Protector: correct self-image and hours of sport practiced | Does not inform |

| Sousa, Et al, 2014, Spain. (31) | Cross | 562 adolescents between 10 and 15 years old | Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26). | Does not inform | Risk: increased BMI | Does not inform | Risk: body dissatisfaction in women, the degree of psychological commitment to exercise. |

| Castaño, Et al, 2012, Colombia. (32) | Cross | 70 adolescents with anorexia aged 11 to 19 years | Eating Disorders Inventory-3 (EDI-3) | Does not inform | Risk: increased BMI | Risk: Internalization of the slim ideal. | Does not inform |

| Haynos, 2016, Spain (34) | Longitudinal cohort | Time I: 4,746 students between 1998-1999 from 11 to 18 years old. Time II: 2,516 students between 2003-2004 | EAT Project Survey | Risk: Family communication and poorer care | Does not inform | Risk: Weight-related teasing | Risk: High depression and low self-esteem. |

| Maezono, Et al, 2019, Japan / Finland. (35) | Cohort | 1,840 Japanese students (2011) and 1,135 Finnish students (2014) 13-15 years old. | Scale developed by Koskelainen, Sour Ander & Helenius | Does not inform | Does not inform | Does not inform | Risk: Dissatisfaction and concern with their bodies in Japanese and Finnish women and food distress in Finnish women. |

| Batista, Et al, 2018, Croatia. (36) | Cohort | 35 women with anorexia nervosa and 35 healthy between 12-18 years. | Eating Disorders Inventory-3 (EDI-3). | Does not inform | Does not inform | Risk: Internalization of the slim ideal. | Risk: interpersonal problems, affective problems and excess control, Low Self-esteem, Personal alienation, Interpersonal insecurity, Interpersonal alienation, Interoceptive deficits, Emotional dysregulation, Perfectionism and asceticism in women with anorexia. |

Factors associated with eating disorders

Different instruments were used to measure the factors associated with eating disorders. In 14.2% (n = 7) of the analysed studies, authors used the Eating Attitude Test (EAT-26) (17,18,20,21,25,30,31), 11% (n = 5) the Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) (21,25,27,29,31), and 9.5% (n = 4) the Sociocultural Attitudes Questionnaire towards appearance-3 (SATAQ-3) (20, 28, 32, 36). About 93% (n = 14) of the studies analysed risk factors and about 7% (n = 1) analysed correct self-image and hours of practiced sport as protective factors (B = 0.11; p = 0.047) (30). Regarding the risk factors, psychological risks were the most frequently analysed by the studies (71%). They included dissatisfaction with body image, low self-esteem, high depression, high perfectionism, stress, impulsivity, personal and interpersonal insecurity, emotional dysregulation, and ineffectiveness. About 14% of the studies analysed sociocultural factors such as alcohol use-related problematics, internalization of the thinness ideal, influence of media, ridicule related to weight, and being an immigrant adolescent. Also, 7.1% of the studies analysed family factors such as authoritarian family style, family functioning, poor communication, and family care. Lastly, 7.1% of the studies analysed biological factors such as being female. The complete description of the factors is summarized in Tab. 3.

Analysis of vote counting and sign test

It was found that there was a greater number of studies that reported statistically significant relationships between factors such as body dissatisfaction, female gender, depression, low self-esteem, and higher body mass index (BMI) with eating disorders (Tab. 4). In this sense, adolescents with those risk factors are more likely developing eating disorders.

Tab 4.

Analysis by vote counting and sign test.

| Vote Counting and Sign Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factor variables | Positive | Negative | P value | n = 22 |

| Body dissatisfaction | 10 | 0 | 0.4159 | 10 |

| Female gender | 5 | 0 | 0.0085 | 5 |

| Depression | 5 | 0 | 0.0085 | 5 |

| lower self-esteem | 3 | 2 | 0.0004 | 5 |

| Higher BMI | 1 | 4 | 0.0022 | 5 |

Discussion

In the present review, the results show that the main factors associated with eating disorders were psychological-type with a prevalence of the factor inherent the dissatisfaction with body image (16─18, 21, 25, 27, 29, 31, 32, 35). Literature refers that dissatisfaction with body image increases significantly in adolescence due to environmental pressures like media (e.g., television, social networks, virtual and written press) (20, 28). They represent channels of transmission of the current body aesthetic model and have a positive or negative impact on an adolescent’s body image. This is more common in women, as it was the biological factor reported in this review. However, the findings are consistent with other studies where dissatisfaction with body image occurs more frequently in females and is positively associated with BMI as a predictor of eating disorders. (37, 38). Similarly, BMI appears directly related to dissatisfaction with one’s own body, namely the higher the BMI, the higher the body dissatisfaction (25, 31─33, 36). This association is more recurrent in female gender (17, 22, 26, 28, 30) as girls generally show greater instability of self-image, lower self-esteem and general dissatisfaction with their body, if compared to boys. In most studies, the sample studied was female (29, 33, 34, 36). Other psychological factors were emerged from the review. They were: appearance orientation (28), high level of perfectionism (23, 29), low self-esteem (18, 29, 33, 34, 36), impulsivity (22), stress, suicidal idea and depression (22, 26, 27, 29, 34), eat in the absence of hunger (28), concern about being overweight, submission (24), personal and interpersonal insecurity (29, 36), and emotional dysregulation (33). A teenager with low self-esteem shows a negative attitude and evaluation towards himself. In fact, low self-esteem has been repeatedly considered as a relevant factor of vulnerability for the development of EDs. This evidence is supported by a previous review (39). It is also important to identify depressive and anxiety manifestations that have an impact on food restriction and concerns about figure and weight. The number of studies that supported the relationship between psychological factors and eating disorders was statistically significant according to the sign test.

Socio-cultural factors were analysed in 14.2% of the selected studies (15, 16, 20, 24, 26, 32, 36). The most frequently revealed were the internalization of the thin ideal followed by the influence of media, weight-related bullying , and immigrant adolescents. These sociocultural factors and the desire to conform to body aesthetic models promoted by media and advertising have a greater likelihood to developing perceptions of body dissatisfaction. Moreno (40) showed a very high relationship between the influence of the media and the presence of eating disorders in the adolescent population. This is a cultural problem that comes from long ago where the idea that a perfect body is thin and that this it is accepted by society. The media are very important agents in the transmission of messages about the desire for thinness that is constantly present in eating disorders; the media channel social pressure to be thin is obviously stronger on females than males (40).

A few studies analysed the relationship between family factors and eating disorders (19, 21, 34). However, family functioning, poor communication, family care, and authoritarian styles are factors described in the literature as predisposing to eating disorders by impacting the way adolescents worry about the amount of calories in food and obsessed with food and weight gain. In this sense, parents can play a protective role, but they can also represent a risk factor for their children’s eating behaviour, as adolescents regulate their behaviour according to their parental model from early childhood (40, 41).

In this review, we found only one research that addressed protective factors related to physical exercise and correct ideas about body image. This could be due to the fact that research in the last two decades has focused on mitigating or controlling risk factors as the sole basis for interventions to prevent eating disorders in adolescents. However, protective factors make adolescents less vulnerable to the development of eating disorders and facilitate the achievement of physical and mental health, the quality of life of adolescents, the development of healthy habits and social welfare. Protective factors are susceptible to being modified and intensified and do not necessarily occur spontaneously or at random. In this sense, interventions focused on strengthening those factors could be effective to prevent eating disorders behaviours. This requires the development of research that identifies and analyses the protective factors that can be strengthened in adolescents (42─44).

Most of the studies included in this systematic review are cross-sectional and in a lower percentage are cohort studies. Spain is the country that has done the most research on the factors associated with eating disorders in adolescents, thus showing a particular interest in this topic. However, this review has shown that there is a plurality of studies in the scientific community from different sociocultural contexts. This can explain why there is variability of risk factors for eating behaviour, although body dissatisfaction is the most common factor emerged from the revision.

The limitations of the review reflect the heterogeneity of the study that does not allow to carry out a meta-analysis and statistic associations between factors. Although the vote count and the sign test allow giving an additional value to the narrative synthesis of the results, they are limited procedures to establish reliable statistical associations with data. In this sense, reviews around the subject with quantitative analysis procedures would be necessary.

Conclusions

Psychological factors were found to be the main risk factors directly related to eating disorders in adolescents. The most common were: dissatisfaction with body image, depression, low self-esteem and higher BMI. Being a woman was also identified as the most reported biological factor associated with eating disorders. These risk factors become relevant when guiding the creation of mental health promotion programs for adolescents and the prevention and early detection of the eating disorders in adolescents.

Conflict of Interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

References

- National Institute of Mental Health. Eating disorders: A problem that goes beyond food. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez A. Prevalence of eating disorders in six European countries. Metas Enferm. 2017 Jun;20(5):66–73. Spanish. https://doi.org/10.35667/MetasEnf.2019.20.1003081094. [Google Scholar]

- Fajardo E, Méndez C, Jauregui A. Prevalence of risk of eating disorders in a population of secondary school students, Bogotá Colombia. Revista Med. 2017;25(1):46–57. Spanish. https://doi.org/10.18359/rmed.2917. [Google Scholar]

- Smink F, Daphne V, Hans H. Epidemiology of Eating Disorders; Incidence, prevalence and Mortality Rates. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14:406–14. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y. doi: 10.1007 / s11920-012-0282-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, Borges G, Medina M, et al. In: The Mental Health Survey in Adolescents in Mexico. Epidemiology of mental disorders in Latin America and the Caribbean. Rodríguez J, Kohn R, Aguilar S, editors. Washington: Pan American Health Organization; 2009. pp. 107–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz Cuquejo LM, Aguiar C, Samudio Domínguez GC, et al. Eating disorders in adolescents: a growing pathology? Pediatr (Asunción) 2017 Apr;44(1):37–42. Spanish. https://doi.org/10.18004/ped.2017.abril.37-42. [Google Scholar]

- Gaete P V, López C C. Eating disorders in adolescents. A comprehensive approach. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2020 Oct;91(5):784–93. doi: 10.32641/rchped.vi91i5.1534. Spanish. doi: 10.32641/rchped.vi91i5.1534. PMID: 33399645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Mental health in adolescents. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Adolescent Development. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- Urrutia G, Bonfill X. PRISMA statement: a proposal to improve the publication for systematic reviews and meta-analyzes: Rev. Medicina Clínica. 2010;1:507–511. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciapponi A. Guide to critical reading of observational studies in epidemiology (first part)] Evid Actual Práct Ambul. 2010 Oct-Dec;13(1):135–40. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- Ciapponi A. Critical reading guide of observational studies in epidemiology (second part) Evid Actual Práct Ambul. 2011 Mar;14:7–14. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- Pino R, Frías A, Palomino P. The quantitative systematic review in nursing. RIDEC. 2014 Jan;7:24–40. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Esteban L, Veiga O, Gómez S, et al. Length of residence and risk of eating disorders in immigrant adolescents living in madrid. The AFINOS study. Nutr Hosp. 2014;29(5):1047–53. doi: 10.3305/nh.2014.29.5.7387. doi: 10.3305/nh.2014.29.5.7387. PMID: 24951984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahyad S, Pakdaman S, Shokri O, et al. The Role of Individual and Social Variables in Predicting Body Dissatisfaction and Eating Disorder Symptoms among Iranian Adolescent Girls: An Expanding of the Tripartite Influence Mode. Eur J Transl Myol. 2018;28(1):72–7. doi: 10.4081/ejtm.2018.7277. doi: 10.4081/ejtm.2018.7277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yirga B, Assefa Y, Derso T, et al. Disordered eating attitude and associated factors among high school adolescents aged 12-19 years in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9(1):503. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-2318-6. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-2318-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altamirano Martínez MB, Vizmanos Lamotte B, Unikel Santoncini C. Continuum of risky eating behaviors in Mexican adolescents. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2011 Nov;30(5):401–7. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892011001100001. Spanish. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892011001100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes MC, García O. Influence of family socialization on satisfaction with body image in Spanish adolescents. Trastornos de la Conducta Alimentaria. 2015;22:2403–25. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- Lazo Y, Quenaya A, Tristán P. Mass media influence and risk of developing eating disorders in female students from Lima, Peru. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2015;113(6):519–525. doi: 10.5546/aap.2015.eng.519. Spanish. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londoño-Pérez C, Moreno Ruge AM. Family and personal predictors of eating disorders in young people. Anal Psicol. 2017;33(2):235–42. Spanish. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.2.236781. [Google Scholar]

- Nuño-Gutiérrez BL, Celis-de la Rosa A, Unikel-Santoncini C. Prevalence and associated factors related to disordered eating in student adolescents of Guadalajara across sex. Rev Invest Clin. 2009;61(4):286–93. Spanish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamies L, Quiles Y. Perfectionism and risk factors for the development of eating disorders in Spanish adolescents of both genders. Anal Psicol. 2014;30(2):620–26. Spanish. https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.2.158441. [Google Scholar]

- Silva C, Millán B, González K. Gender role and eating attitudes in adolescents from two different socio-cultural contexts: Traditional vs. non-traditional. Rev Mex de Trastor Aliment. 2017;8(1):40–8. Spanish. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmta.2016.12.002. [Google Scholar]

- Fortes Lde S, Cipriani FM, Ferreira ME. Risk behaviors for eating disorder: factors associated in adolescent students. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2013;35(4):279–86. doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2012-0055. doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2012-0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogollo Z, Gómez E. Risk of eating behavior disorders in adolescents from Cartagena, Colombia. Invest Educ Enferm. 2013;31(3):450–6. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- Caldera I, Martin P, Caldera J, et al. Predictors of risk eating behaviors in high school students. Rev Mex Trastor Aliment. 2019;10(1):22–31. http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/fesi.20071523e.2019.1.519. [Google Scholar]

- Reina SA, Shomaker LB, Mooreville M, et al. Sociocultural pressures and adolescent eating in the absence of hunger. Body Image. 2013;10(2):182–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.12.004. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporta I, Delgado M, Reboyar S, et al. Perfectionism in adolescents with eating disorders. Eur J Health Research. 2020;6:97–107. Spanish. doi: 10.30552/ejhr.v6i1.205. [Google Scholar]

- Rod E, Pons R, Lajara F, et al. Influence of the habits of the adolescent population on self-image and the risk of eating disorder. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2011;13(51):387–96. [Google Scholar]

- De Sousa L, De Sousa S, Caputo E. Influence of psychological, anthropometric and sociodemographic factors on the symptoms of eating disorders in young athletes. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto) 2014;24:21–7. Spanish. doi: 10.1590/1982-43272457201404. [Google Scholar]

- Castaño J, Giraldo D, Guevara J, et al. Prevalence of risk of eating disorders in a female population of high school students, Manizales, Colombia, 2011. Rev. Colomb. Obstet. Ginecol. 2012;63(1):46–56. Spanish. doi: https://doi.org/10.18597/rcog.202. [Google Scholar]

- Rutsztein G, Scappatura L, Murawski B. Perfectionism and low self-esteem across the continuum of eating disorders in adolescent girls from Buenos Aires. Rev Mex Trastor Aliment. 2014;5(1):39–49. Spanish. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2007-1523(14)70375-1. [Google Scholar]

- Haynos AF, Watts AW, Loth KA, et al. Factors Predicting an Escalation of Restrictive Eating During Adolescence. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(4):391–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.011. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maezono J, Hamada S, Sillanmäki L, et al. Cross-cultural, population-based study on adolescent body image and eating distress in Japan and Finland. Scand J Psychol. 2019;60(1):67–76. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12485. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista M, Žigić Antić L, Žaja O, et al. Predictors of eating disorder risk in anorexia nervosa adolescents. Acta Clin Croat. 2018;57(3):399–410. doi: 10.20471/acc.2018.57.03.01. doi: 10.20471/acc.2018.57.03.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Flores P, Jiménez Cruz A, Bacardi Gascón M. Body-image dissatisfaction in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Nutr Hosp. 2017;34(2):479–89. doi: 10.20960/nh.455. Spanish. doi: 10.20960/nh.455. PMID: 28421808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancilla A, Vásquez R, Mantilla J, et al. Body dissatisfaction in children and preadolescents: A systematic review. Rev Mex Trastor Aliment. 2012;3(1):62–79. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Bulik CM. Outcomes of eating disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(4):293–309. doi: 10.1002/eat.20369. doi: 10.1002/eat.20369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno J, Torres C. Revisión sistemática de los determinantes socioculturales asociados a los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria en adolescentes latinoamericanos entre 2004 y 2014. Bogotá: UCA publication; University Applied and Environmental Sciences. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Ruíz A, Vázquez R, Mancilla J, et al. Family factors associated with Eating Disorders: a review. Rev Mex Trastor Aliment. 2013;4(1):45–57. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- Góngora VC. Satisfaction with life, well-being, and meaning in life as protective factors of eating disorder symptoms and body dissatisfaction in adolescents. Eat Disord. 2014;22(5):435–49. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2014.931765. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2014.931765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine MP, Smolak L. The role of protective factors in the prevention of negative body image and disordered eating. Eat Disord. 2016;24(1):39–46. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2015.1113826. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2015.1113826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines J, Kleinman KP, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Examination of shared risk and protective factors for overweight and disordered eating among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(4):336–43. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.19. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]