Abstract

Background and aim of the work:

Greater evaluations are needed to identify barriers or facilitators in nurses’ guidelines adherence. The current review aims to explore extrinsic and intrinsic factors impacting nurses’ compliance.

Methods:

Mixed-method systematic review with a convergent approach, following the PRISMA checklist and the JBI Mixed Methods Review Methodological Guidance was conducted. MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL were systematically searched, to find studies published between 2010 and 2021, including qualitative, quantitative or mixed-methods articles.

Results:

Sixty studies were included, and the major findings were analysed by aggregating them in two main themes: intrinsic and extrinsic factors. The intrinsic factors were: a) knowledge and skills; b) attitudes of health personnel; c) sense of belonging towards guidelines. The extrinsic factors were: a) organizational and environmental factors; b) workload; c) guidelines structure; d) patients and caregivers’ attitude.

Conclusions:

The included studies report lack of resources, among environmental factors, as the main barrier perceived. Nurses, who are at the forefront in addressing the direct application of knowledge and skills to ensure patient safety, have a higher perception of this kind of barriers than other healthcare personnel. Potential facilitators emerged in the review are positive feedback and reinforcements at the workplace, either from the members of the team or from the leaders. Moreover, the level of active participation of the patient and caregiver could have a positive impact on nurses’ guidelines adherence. Guidelines implementation remains a complex process, resulting in a strong recommendation to support health policymakers and nursing leaders in implementing continuing education programs. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: clinical practice guideline, adherence, guideline, barrier, advanced practice nursing, mixed-method review, systematic review

Introduction

Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) are systematically developed statements that aim to assist healthcare practitioners and patient decisions, regarding the definition of the most appropriate care for specific circumstances (1). Despite the broad consensus on the use of guidelines and the tools to develop and adapt them, they are not always applied and their impact on clinical practice is not as strong as it should be. Several studies (2-5) have shown that guidelines have only been moderately effective in changing the care process and that there is still space for the improvement of their implementation. Moreover, other studies (6,7) have shown that quite often recommendations aren’t properly adopted, resulting in the possibility that patients will not benefit from an evidence-based practice.

A wide variety of strategies are used to implement guidelines (7), but most of them do not refer to a careful assessment of the reasons why some interventions have failed while others have been successful. To understand and choose the interventions that may be most effective, it is reasonable to start with a model of behaviour (8) in order to capture the range of mechanisms usually involved in change, including the internal (psychological and physical) and external ones (environmental).

Michie et al. (8) depicted a framework for understanding behaviour called the ‘COM-B’ system, where Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation interact to generate behaviour that in turn influences these components. Motivation refers to all those brain processes that stimulate and direct behaviour, including habitual processes, emotional responding, as well as analytical decision-making.

Typically, theories of motivation differentiate between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation is characterized by taking behaviours for their own sake, while extrinsic motivation is characterized by taking actions aimed at a specific outcome such as noticeable rewards, social approval, demonstrating something to oneself or maintaining correspondence among one’s values and behaviours. Many behaviours, particularly those relevant to health promotion (e.g., quitting smoking), disease prevention (e.g., attending screening) or disease management (e.g., comply with medical prescriptions) are extrinsic in nature, but a continuum can be hypothesized for their internalization according to Ryan and Deci’s Self-Determination Theory (SDT). Behaviours become regulated or evaluated more autonomously over time, with an active process that tries to transform an extrinsic reason into personally endorsed values, absorbing behavioural regulations that were originally extrinsic (9).

Considering healthcare workers, intrinsic motivation has been extensively studied in the field of Behavioural Economics (10) and subsequently taken up by the SDT, according to which individuals are intrinsically motivated because they feel satisfied by the simple fact to carry out an activity autonomously. In addition to intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation also plays an important role. According to Berdud et al. (10), recognition in the workplace, involvement in activities for professional development, or engagement in research projects constitute a nonmonetary extrinsic incentive that needs to be considered by health policy makers and managers.

The areas explored by previous reviews concern mainly medical staffs or healthcare workers in general and identified six main extrinsic factors that could act as barriers or facilitators for adopting CPGs: 1) specific characteristics of the guideline (level of clarity and credibility), 2) staff skill mix (level of specialisation, knowledge, etc.), 3) patients’ characteristics (level of attitudes, sociocultural background, etc.), 4) work environment (leadership, teamwork, etc.), 5) health policies (time, financial management, etc.), 6) strategies used to promote adherence. All these aspects can have repercussions on the health professionals and therefore on nurse staff, representing both barriers and facilitators to the adoption of CPGs (2-5).

Nurses are increasingly expected to provide evidence-based care intended to enhance the quality of care. A growing number of nursing guidelines are being published to reduce unwarranted variation in healthcare delivery, but there is still a gap in the knowledge translation process, and the level of adherence to CPGs recommendations has proven to be suboptimal (7,11,12). Bridging the gap between theory and practice is a core responsibility of the nursing scope of practice. A wider understanding of the intrinsic and extrinsic factors acting as barriers or facilitators is needed to improve the nurses’ adherence to CPGs.

Aim

The present study aims to explore and synthesize the available literature on extrinsic and intrinsic factors acting as barriers or facilitators in nurses’ implementation of CPGs, using a mixed-method systematic review with a convergent integrated approach.

Methods

Study Design

To better identify the reasons why some CPGs’ implementation processes fail, and others succeed, a mixed-method systematic review was conducted (13), therefore considering quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies. The mixed-methods approach allows to explore diverse perspectives and to understand the existing relationships among complex phenomena, like new care pathway implementation or CPGs’ adoption. Integrated methodologies directly bypass separate quantitative and qualitative synthesis combining both forms of data into a single mixed-methods synthesis, with a convergent integrated approach (14,15).

This systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (16) and the JBI Mixed Methods Review Methodological Guidance (15). The protocol of the present review was registered on PROSPERO, the International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews (CRD42021230808). No amendments to the PROSPERO protocol were required at the time of registration.

Search strategy

A comprehensive database search consulting MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase and CINAHL was undertaken by two authors, including qualitative, quantitative or mixed-methods primary studies, aiming to identify barriers and facilitators to CPGs’ implementation in any healthcare setting, involving nurses, and published in any language from January 2010 to February 2021. Studies including other health professionals were also considered only if specific data on nursing staff could be extracted.

The time limit was set to 2010 considering that the available literature on the review topic has begun to increase about 10 years ago. No restrictions were applied in terms of patients’ characteristics while, in terms of study design, case series and case reports were excluded. The search strategy was tracked in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy (30 Nov 2020-3 Feb 2021)

| Database | Search | Employed string | Number of results obtained |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | 1 | (‘practice guideline’/exp OR ‘practice guideline’) AND (‘protocol compliance’/exp OR ‘protocol compliance’) AND (‘nursing’/exp OR nursing) | 183 |

| PubMed | 2 | (((clinical practice guideline [MeSH Terms])) AND (adherence, guideline [MeSH Terms])) AND (advanced practice nursing [MeSH Terms]) | 1 |

| PubMed | 3 | (((barrier*)) OR (facilitator*)) AND (adherence, guideline [MeSH Terms]) | 262 |

| PubMed | 4 | (((barrier*) OR (facilitator*)) AND (adherence, guideline [MeSH Terms])) AND (advanced practice nursing [MeSH Terms]) | 1 |

| PubMed | 5 | ((motivation [MeSH Terms]) AND (clinical practice guideline [MeSH Terms])) AND (adherence, guideline [MeSH Terms]) | 9 |

| PubMed | 6 | ((motivation [MeSH Terms]) AND (clinical practice guideline [MeSH Terms])) AND (advanced practice nursing [MeSH Terms]) | 0 |

| PubMed | 7 | ((clinical practice guideline [MeSH Terms]) AND (implementation plan, annual [MeSH Terms])) AND (adherence, guideline [MeSH Terms]) | 0 |

| PubMed | 8 | (((clinical practice guideline [MeSH Terms]) AND (implementation plan, annual [MeSH Terms])) AND (adherence, guideline [MeSH Terms])) | 26 |

| PubMed | 9 | ((clinical practice guideline [MeSH Terms]) AND (enablers [MeSH Terms])) AND (advanced practice nursing [MeSH Terms]) | 0 |

| Embase | 10 | (‘nurse’/exp OR nurse) AND (‘practice guideline’/exp OR ‘practice guideline’) AND (‘protocol compliance’/exp OR ‘protocol compliance’) | 86 |

| Cinahl | 11 | AB (adherence or compliance) AND AB (guidelines or protocols or practice guideline or clinical practice guideline) AND AB ( nurse or nurses or nursing ) AND AB (barriers or obstacles or challenges ) | 302 |

Study selection and quality appraisal process

After removing the duplicates, two authors independently screened each article by titles and abstracts for excluding the studies that did not meet the review’s inclusion/exclusion criteria. The measurement of investigators’ agreement for categorical data was calculated with Cohen’s Kappa (17).

Full texts of the eligible studies were retrieved and then critically appraised for methodological quality using the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (18,19). The MMAT is a critical appraisal tool designed for the appraisal stage of systematic mixed studies reviews allowing the evaluation of the methodological quality of five categories of studies: qualitative research, randomized controlled trials, non-randomized studies, quantitative descriptive studies, and mixed methods studies.

Two authors performed the methodological evaluation and, in case of disagreement, a consensus discussion with a third author was planned to align possible different views in performing the evaluation.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two authors independently extracted data from the articles of the eligible studies using a standardised Excel data extraction form. Data extracted included publication details, the aim of the study, research paradigm/design, setting/sample and major findings meant as extrinsic/intrinsic factors acting as barriers or facilitators. For the purpose of this mixed method review, the main results were also graphically synthesised according to the theoretical domains adopted (4,20) and the integrated analysis of the major findings.

Results

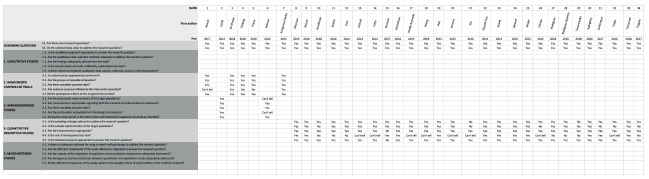

As described in Figure 1, the electronic searches identified 870 records from the developed queries (n=482 PubMed; n=86 EMBASE; n=302 CINAHL). After removing the duplicates (n=44), two authors screened 826 titles and abstracts. In this phase, 712 records were excluded. Of the remaining 114 studies, 50 were excluded after reading the full text because the samples did not include the target population (other health professionals were included such as physicians, physiotherapists, and midwives, but not nurses), one article was in press, three were not available.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

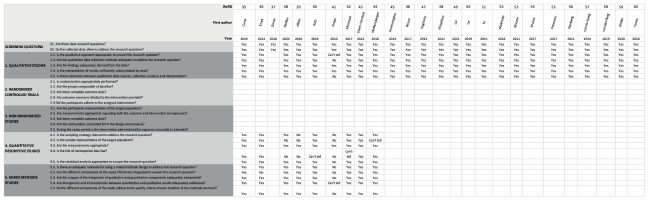

At the end of the study selection process, 60 studies were included in the present review. After the title/abstract screening phase, the level of agreement between the two reviewers was 0.98 according to the Cohen’s Kappa (21). The disagreement regarding the inclusion of the unclear studies was solved discussing with a third author. The overall quality, appraised using the MMAT, settles on a good level. The evaluation of the methodological quality is reported in Figure 2a and 2b.

Figure 2a.

Evaluation of the methodological quality with Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (studies 1-34).

Figure 2b.

Evaluation of the methodological quality with Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (studies 35-60).

Description of the included studies

The present mixed method review included 60 studies: 34 quantitative, 16 qualitative and 10 mixed-methods. To provide a wider view of the issue, three implementation projects (22-24) were also included and analysed among the qualitative paradigms. The main characteristics and results of the included studies are available in Tab. 2.

Table 2.

Synopsys of the included studies

| Pubblication details | Principal aim of the study | Research paradigm | Research design/method | Setting and Sample | Major findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INTRINSIC FACTORS | EXTRINSIC FACTOR | |||||

| Aloush 2017 |

To evaluate the effect of the VAP (Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia) prevention guidelines education on nurses’ compliance |

QUAN | RCT 2-group posttest only design |

Jordan I group underwent an intensive VAP education course (n 60, 1 dropped out), whereas the C group participants received nothing (n 60, 17 withdrew) Mean age: 31 ± 5.6 |

WORKLOAD Factors influencing compliance in the entire group: -number of beds per unit (fewer beds) nurse to patient ratio |

|

| Cahill 2014 |

To improve adherence to critical care nutrition guidelines for the provision of enteral nutrition |

QUAN | RCT Before-after study |

USA ICU (Intensive Care Unit): minimum of 8 beds, affiliated with a registered dietitian, located in North America A total of 182 critical care staff (134) (74% nurses) responded at T0, and 118 (79% nurses) at follow up |

ATTITUDE Trust in prescription, fear of adverse events |

ENVIRONMENTAL Delivery of Enteral Nutrition to the Patient, delays in prescription, lack of supplies (feeding tubes) |

| De Meyer 2018 |

To study the effectiveness of tailored repositioning and a turning and repositioning system on nurses’ compliance to repositioning frequencies. | QUAN | RCT Multicentre, cluster, three‐arm, randomized, controlled pragmatic trial |

Europe 16 northern Europe hospitals-29 wards (Convenience sample) 502 nurses trained and a total of 227 patients (mean age 80.7 years, SD 11.4), mean Braden Scale 12.9 (SD 2.4); 8 intensive care units, 13 geriatric wards and 8 rehabilitation wards |

ATTITUDE Resistance to the adoption of new practices (moderate-not present) |

WORKLOAD lower back strain (moderate) |

| Förberg 2016 |

To investigate the effects of implementing a CPG for Peripheral Venous Catheters (PVCs) in paediatric care in the format of reminders integrated in the EPRs (Electronic Patient Records), on PVC-related complications and on RNs’self-reported adherence. |

QUAN | RCT Cluster Randomised Trial |

Sweden Inpatient units with access to the PVC template in the EPR system to document PVCs RNs Intervention group (IG) T0: 108 RNs Control group (CG) T0: 104 RNs Intervention group (IG) T1: 106 RNs Control group (CG) T1: 102 |

ENVIROMENTAL RNs work Context (leadership, work culture, and evaluation- the use of data to provide feedback on the unit’s performance). Work culture scoring higher in IG. |

|

| Friese 2019 |

To evaluate whether a web-based educational intervention improved Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) use among oncology nurses who handle hazardous drugs | QUAN | RCT Cluster randomized controlled trial |

USA 12 ambulatory oncology settings 396 nurses, (257 completed baseline and primary endpoint survey) RNs Intervention group (IG) (n 121): one-hour educational module on PPE use with quarterly reminders RNs Control group (CG) (n 136): control intervention + tailored messages to address perceived barriers and quarterly data gathered on hazardous drug RNs in IG reported higher workloads (6.2 patients vs 5.0) |

ENVIROMENTAL practice environments, safety behavior, organizational factors, Structural barriers to partecipation, access to web-based contents, WORKLOAD workload demands, limited time for participants to view materials during their scheduled shift, and vague or unclear institutional policies on gowns, eye protection, and respirator use when handling hazardous drugs. |

|

| Holmen 2016 |

To improve Hand Hygiene (HH) compliance among physicians and nurses in a rural hospital in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) using the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care | QUAN | quasi- RCT Quasi-experimental design |

Rwanda A 160-bed, non-referral hospital in Gitwe 12 physicians and 54 nurses |

ENVIRONMENTAL resources, lack of supplies (water) |

|

| Snelgrove-Clarke 2015 |

To determine the effects of an Action Learning intervention on nurses’ use of a Fetal Health Surveillance (FHS) guideline during labor of women who were low risk on admission. | QUAN | RCT Pragmatic randomized controlled trial |

Canada Birthing unit of teaching hospital in Atlantic All nurses working in the birth unit were invited to participate in the study. Exclusion criterion was nurses who were on leave (n=62) |

PATIENTS- CAREGIVERS’ ATTITUDE clinical characteristics fetal heart rate, type of analgesia (both enablers and inhibitors) ENVIRONMENTAL resources: supplies: doppler availability; policy |

|

| Alhassan 2019 |

To explore self-rated adherence to standard protocols on nasogastric tube feeding among professional and auxiliary nurses and the perceived barriers impeding compliance to these standard protocols. | QUAN | Observational Study Descriptive analytical cross-sectional study | Ghana professional (n = 89) and auxiliary (n = 24) nurses |

KNOWLEDGE Accessibility: limited opportunities for in-service trainings, insufficiency of nasogastric tube feeding protocols on the wards. |

ENVIRONMENTAL lack of supplies: inadequate supply of the re-requisite nasogastric tubes PATIENTS- CAREGIVERS’ ATTITUDE opposition from relatives of patients |

| Aloush 2018 |

To assess nurses’ compliance with Central Line Associated Bloodstream Infection (CLABSI) prevention guidelines related to maintenance of the central line and the predictors of compliance | QUAN | Observational Study Descriptive cross-sectional design | Jordan ICUs of 15 hospitals 171 nurses, 81% female, mean age 32.5 y.o., 43% no prevoious education about CLABSI |

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS Lack of supplies WORKLOAD Nurse-patient ratio (better 1:1) |

|

| Avedissian 2018 |

To describe the current practices in the management of severe allergies and anaphylaxis by Lebanese nurses working in schools and day cares and to explore the perceived need for a protocol to manage anaphylaxis reaction |

QUAN | Observational Study Cross-sectional survey | Lebanon 59 school and 126-day care nurses participated |

KNOWLEDGE Lack of training, education ATTITUDES Motivation Hesitance |

|

| Burkitt 2010 |

To assess the effect of a multicenter methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) prevention initiative on changes in employees’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices |

QUAN | Observational Study cross-sectional study | USA nurses (38%), allied health professionals (30%), other support staff (24%), and physicians (9%) under age 50 years (57%) |

KNOWLEDGE/ATTITUDES Awareness/agreement hand cleansing causes damage to skin |

WORKLOAD Too busy |

| Cato 2014 |

To describe the predictors of nurse actions in response to a mobile health Decision Support System (mHealth DSS) for guideline-based screening and management of tobacco use. | QUAN | Observational Study Observational design focused on experimental arm of a randomized, controlled trial. | USA 14,115 patient encounters and 185 nurses enrolled |

KNOWLEDGE AND SKILLS (Family and Pediatric, Adult Nurses Practitioners) |

EXTRINSIC FACTORS- PATIENTS-CAREGIVERS’ ATTITUDE Attitudes (preferences, inabilities) Women, African American, payer source |

| Chavali 2014 |

To improve Hand Hygiene (HH) compliance among all health care staff. To assess adherence to HH among nurses and allied healthcare workers, at the end of the training year. |

QUAN | Cross-sectional observational study. 1500 HH opportunities were observed. Among 38 healthcare workers, 28 were nurses (73.6%) and 10 (26.3%) other healthcare workers. |

India nursing staff (n = 28) and allied healthcare workers (n = 10) |

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS Lack of supplies (hand rub) Lack of resources (nurses’ shortage) WORKLOAD Pressure |

|

| Cotta 2014 |

The aim of this study was to describe perceptions and attitudes towards antimicrobial resistance, antimicrobial use, AMS (Antimicrobial Stewardship) interventions, and willingness to participate |

QUAN | Observational Study Quantitative Survey, descriptive study | Australia 331 respondents (24% physicians, 18% surgeons, 24% anaesthetists, 32% nurses and 3% pharmacists |

KNOWLEDGE lack of awareness (problem in other hospitals, do not want to participate in AMS interventions), lack of familiarity |

|

| Damush 2017 |

To identify key barriers and facilitators to the delivery of guideline-based care of patients with TIA (Transient Ischemic Attack) | QUAN | Observational Study Cross-sectional, observational study | USA Veterans Administration Medical Centers having an annual volume of ≥25 patients with a TIA or minor stroke. |

KNOWLEDGE inadequate staff education |

ENVIROMENTAL Organizational constraints (access brain imaging, lack of coordination, resource constraint, rotating pool of house staff) |

| Gustafsson 2016 | To determine if nurse anesthetists (NAs) have access, knowledge, and adhere to recommended guidelines to maintain normal body temperature during the perioperative period. | QUAN | Observational Study Descriptive survey design. | Sweden 56 operating departments |

ATTITUDES Motivation Agreement (it was not a routine to do…) |

ENVIRONMENTAL Resources, time equipment, supplies PATIENTS- CAREGIVERS’ ATTITUDE Preferences (feeling warm or having a temperature) |

| Harillo-Acevedo 2019 |

To determine the effect of implementing a breastfeeding clinical practice guideline on factors associated with breastfeeding support by health care professionals, adopting a Theory of Planned Behavior approach. | QUAN | Observational Study Cross-sectional Study Implementation of breastfeeding CPG |

Spain All health care professionals of all categories working in maternal and/or pediatric care: 164 preimplementation and 152 postimplementation |

SENSE OF BELONGING Social pressures to enact a behavior. ATTITUDES Self-efficacy |

|

| Huang 2019 |

To investigate the barriers in administering enteral feeding to critically ill patients from the nursing perspective. To provide tailored interventions for addressing identified barriers and propose an optimal Enteral Nutrition (EN) practice in Intensive Care Unit (ICU). |

QUAN | Observational Study Cross‐sectional descriptive study. | China 808 nurses recruited |

KNOWLEDGE Lack of time for training |

ENVIRONMENTAL Organizational constraints (delay in physicians) PATIENTS- CAREGIVERS’ ATTITUDE Diarrhea |

| Huis 2013 |

To examine which components of two hand hygiene improvement strategies were associated with increased nurses’ hand hygiene compliance. |

QUAN | Observational Study Process evaluation of a cluster randomized controlled trial | The Netherlands 67 nursing wards in three Dutch hospitals |

MOTIVATION Trust, self-efficacy related to experienced feedback, social influence within teams |

ENVIROMENTAL leadership (team and leaders-directed strategy) |

| Jansson 2013 |

To explore critical care nurses’ knowledge of, adherence to and barriers towards evidence-based guidelines for prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia | QUAN | Observational Study Quantitative cross-sectional survey. | Finland critical care nurses (n = 101) |

KNOWLEDGE: Lack of knowledge, guidance |

ENVIRONMENTAL: Lack of time, resources, staff |

| Jho 2014 |

To evaluate knowledge, practices and perceived barriers regarding cancer pain management among physicians and nurses in Korea | QUAN | Observational Study Questionnaire developed on Cancer Pain Management Guideline | Korea A total of 333 questionnaires (149 physicians and 284 nurses) were analyzed |

KNOWLEDGE Insufficient knowledge |

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS lack of time. Perceived malpractice: insufficient communication with patients or with physician (contacting physician for prescription of Opioid). Lack of supplies: Medication and intervention costs PATIENTS- CAREGIVERS’ ATTITUDE Reluctance to report pain Reluctance to take opioid |

| Kiyoshi-Teo 2014 |

To identify factors that influence adherence to guidelines for prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia, with a focus on oral hygiene, head-of-bed elevation and spontaneous breathing trials | QUAN | Observational study Cross-sectional descriptive study | USA 576 critical care nurses |

ATTITUDES user attitude scale KNOWLEDGE awareness, level of prioritization |

ENVIRONMENTAL Time availability |

| Kowitt 2013 |

To identify factors associated with hand hygiene compliance during a multiyear period of intervention. | QUAN | Observational study Infection control implemented hospital-wide hand hygiene initiatives |

USA Nurses, Physician, Technical Staff, Support staff Calculated as: n of hand hygiene opportunities for each staff member |

KNOWLEDGE Volume of information, educational campaign ATTITUDE Better after living patient’s room |

WORKLOAD Better compliance during night shift/weekend ENVIROMENTAL Organizational factors (Intesive Care Unit and pediatric wards) |

| Løyland 2015 |

To describe hand-hygiene practices in Pediatric Long-Term Care (pLTC) facilities and to identify observed barriers to, and potential solutions for, improved infection prevention. | QUAN | Observational study World Health Organization’s ‘5 Moments for Hand Hygiene’ validated observation tool to record indications for hand hygiene and adherence |

USA Direct providers of health, therapeutic and rehabilitative care, and other staff responsible for social and academic activities. Nurses 207 on a total of 847 providers (24.4%) |

ATTITUDES Someone used to or not, use of phone in contact precautions rooms KNOWLEDGE confusion about which PPE should be worn for different types of isolation precautions |

ENVIRONMENTAL Fear of punishment, use of dispensers or sinks is impractical while working, shared rooms among residents with infections WORKLOAD HH was particularly challenging when working alone with groups of residents PATIENTS- CAREGIVERS’ ATTITUDE Parents kissing or having close contacts with children |

| Muller 2015 |

The authors evaluated whether Emergency Department (ED) crowding is associated with reduced hand hygiene compliance among health care workers |

QUAN | Observational study A trained observer randomly selected a specific ED room or bay and observed all staff providing care in that area for a 20-minute period |

Canada Nurses, Physicians and other staff providing care in ED |

ATTITUDE Better after patient contact |

ENVIRONMENTAL Crowding in ED WORKLOAD Higher Nursing Hours |

| Omran 2015 |

To explore the knowledge, experiences, and perceived barriers to Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening among HCPs working in primary care settings |

QUAN | Observational study Descriptive cross-sectional design | Jordan 236 HCPs (Health Care Providers) (45.8 %) nurses, physicians (45.3 %), and others (7.2 %) |

KNOWLEDGE Lack of awareness about CRC screening test lack of policy/protocol on CRC screening |

PATIENTS- CAREGIVERS’ ATTITUDE Fear for diagnosis ENVIRONMENTAL Lack of resources: shortage of trained HCPs to conduct invasive screening |

| Rodrigues 2018 |

To verify the knowledge and practices of health professionals working in Prenatal Care (PNC) related with syphilis during pregnancy and to identify the main barriers to the implementation of protocols for the control of this disease. | QUAN | Observational study Cross‐sectional study | Brazil 366 physicians and nurses working in PNC |

KNOWLEDGE Lack of ATTITUDES professional difficulties (Difficulties in approaching and treating the sexual partner of an infected pregnant woman) |

PATIENTS- CAREGIVERS’ ATTITUDE nonattendance of the partner to the service, late onset of PNC, and nonadherence of the pregnant woman to the testing or treatment ENVIRONMENTAL Organizational delays in identification and treatment |

| Rodríguez Aparicio 2019 |

To identify the barriers and drivers fo r adherence to the care bundle in order to prevent complications associated with vascular access devices. |

QUAN | Observational Study Descriptive cross-sectional study | Spain 150 participants, with a participation rate of 31% (150/483): 80% were a nurse (n = 120) and 20% doctor (n = 30) |

ATTITUDES Age (older and younger), experience, lack of compliance and agreement and commitment to the CPG KNOWLEDGE Lack of training |

|

| Senanayake 2018 |

To assess whether a more context-specific modified version of WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist (mSCC) would result in improved adoption rate |

QUAN | Prospective Observational study Level of acceptance was assessed using a self-administered questionnaire study |

Sri Lanka Nurses and Midwives in 2 University Obstetrics Unit (18 vs 12 in DSHW) (20 vs 8 in THMG + 8 Doctors) |

ATTITUDES Motivation (lack of enthusiasm) KNOWLEDGE inadequate training |

WORKLOAD Lack of staff ENVIRONMENTAL Organizational lack of accountability. Lack of supervision from Institutional Level |

| Spångfors 2020 |

To describe registered nurses’ perceptions, experiences and barriers for using the National Early Warning Score in relation to their work experience and medical affiliation |

QUAN | Observational study Web-based questionnaire study | Sweden 3,165 registered nurses working in general somatic hospital wards, Emergency Departments (ED) and the Cardiac High Dependency Unit (CHDU) |

ATTITUDES Trust (lack of response from doctor), lack of added value to the situation |

WORKLOAD lack of time CPG STRUCTURE Too much time to document |

| Stahmeyer 2017 |

To determine the number of hand hygiene opportunities (HHOs), compliance rates, and time spent on hand hygiene in intensive care units | QUAN | Observational study N of opportunities, timing of 300 hands disinfections |

Germany HHO 81.1% nurses, 15.8 Physician, 3.1% Others |

ENVIRONMENTAL Lack of resources WORKLOAD Time |

|

| Tinkle 2016 |

To assess the adherence of women’s health providers in New Mexico to the Women’s Preventive Services Guidelines, now covered as part of the Affordable Care Act, and to examine how providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and external barriers are associated with adherence to these clinical guidelines. | QUAN | Observational Study Cross-sectional, descriptive survey | USA Women’s health providers in New Mexico, including nurse practitioners (57.7%), certified nurse-midwives (12%), and family practice and obstetrician/gynecologist physicians (30.3%) |

ENVIRONMENTAL Organizational (Lack of Time, Lack of Supplies, lack of staff, reimbursement PATIENTS- CAREGIVERS’ ATTITUDE Acceptability |

|

| Tomaszek 2018 |

To compare knowledge and compliance with good clinical practices regarding control of postoperative pain among nurses, to identify the determinants of nurses’ knowledge and to define barriers to effective control of postoperative pain |

QUAN | Observational Study Cross-sectional study | Poland 257 nurses from hospitals with a “Hospital without Pain” certificate and 243 nurses from noncertified hospitals, with mean job seniority of 17.6 _ 9.6 years |

KNOWLEDGE lack of (both physician and nurse) ATTITUDES Not practical to apply (inability to modify the protocol of pain treatment) lack of standard procedures for pain assessment and control Motivation discomfort associated with too frequent referral to a physician, lack of autonomy in prescribing lack of sympathy to patient’s suffering |

|

| Trogrlic´ 2017 |

Survey aimed at identifying barriers for implementation that should be addressed in a tailored implementation intervention targeted at improved ICU (Intensive Care Unit) delirium | QUAN | Observational Study Online survey | The Netherlands 360 ICU health care professionals (nurses (79%), physicians and delirium consultants) |

KNOWLEDGE (Deficit, low familiarity with CPG) ATTITUDES Beliefs that’s not preventable, lack of trust in reliability SENSE OF BELONGING Lack of collaboration and trust |

CPG STRUCTURE Disbelief that it would be optimal for patients, is cumbersome or inconvenient in daily practice ENVIRONMENTAL Organization Lack of time |

| Currie 2019 |

To identify factors which influence staff compliance with hospital MRSA screening policies | MIXED | Sequential mixed-methods design | UK Ward based nursing staff: 38 |

KNOWLEDGE enabler: awareness about consequence, values and beliefs |

ENVIRONMENTAL Lack of time and patients flow pressures Organizational: enabler; audit, feedback, compliance |

| Ersek 2014 |

To identify facilitators and barriers that affected the success of an intervention aimed at promoting the adoption of evidence-based pain management protocols into Nursing Homes (NHs) |

MIXED | Mixed methods study Focus group interviews Quantitative methods |

USA convenience sample of four NHs (17 RNs, three licensed practical nurses, one advanced practice RN, and two certified nursing assistants) |

ATTITUDES provider mistrust of nurses’ judgment |

ENVIRONMENTAL Resources: lack of facilities, salary, benefits Organizational: turnover, regulatory issues, policies, administrative support, staff consistency |

| Garcia 2016 |

To explore health care workers identified barriers to cervical cancer screening in rural Southwest Virginia | MIXED | Mixed methods study Telephone-based structured interviews and conventional content analysis |

USA Sample Office manager (50%) or a registered nurse (34%) |

PATIENTS- CAREGIVERS’ ATTITUDE fear, comfort, lack of education, lack of priority, insurance, cost, or transportation |

|

| Heidke 2020 |

To report on registered nurses’ adherence to current Australian health behaviour recommendations |

MIXED | Mixed methods study Four health risk factors were examined: diet, smoking, physical exercise and alcohol consumption+ BMI |

Australia 23 registered nurses |

ATTITUDE Motivation (family commitments) |

WORKLOAD (Shifts, n of hours) |

| Hilton 2016 |

To determine the views of nurses and on the feasibility of implementing current evidence-based guidelines for oral care, examining barriers and facilitators to implementation |

MIXED | Mixed methods study Online survey of 35 nurses and residential care workers, verified and expanded upon by one focus group of six residential care workers |

Australia 45 nurses and residential care workers, 35 surveys included. |

ATTITUDE Oral care is viewed as a low priority, negative attitude of the staff KNOWLEDGE Lack of training, education |

ENVIRONMENTAL Lack of Supplies: access to proper materials, and human resources (dentists) and family participation as a facilitator Inadequate staffing, lack of time PATIENTS- CAREGIVERS’ ATTITUDE resident’s teeth were a barrier, poor behaviour, non-compliance, or lack of participation with oral care, dysphagia |

| Katz 2016 |

To identify barriers and facilitators to implementation of smoking cessation in Veterans general medicine units | MIXED | Mixed methods study 20-item decisional balance survey and 2 items that asked nurses to rate their self-efficacy and satisfaction in helping patients to stop smoking |

USA 164 nurses surveyed and conducted semistructured interviews in a purposeful sample of 33 nurses |

ATTITUDE Self-efficacy (facilitators: reminders in the electronic medical record and readily available self-help materials/Barriers: Skepticism about effectiveness, perceived self-efficacy and normative believe about nurses’ role |

ENVIRONMENTAL: Organization: nurses’ leaders should promote smoking cessation/ resources lack of time and resources, lack of coordination. PATIENTS- CAREGIVERS’ ATTITUDE Resistance |

| Knops 2010 |

Long-term adherence to two hospital guidelines was audited. The overall aim was to explore factors accounting for their long-term adherence or non-adherence | MIXED | Mixed methods study While long-term adherence was audited, focus groups were launched to explore nurses’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators regarding long-term adherence to their guideline |

The Netherlands 15 Nurses and 44 oncologists |

SENSE OF BELONGING Reminded each other/ favorable social context |

ENVIRONMENTAL Resources: Time (saved them a lot of time and trouble) CPG STRUCTURE Barriers: daily clinical practice complex, too many patients on their wards who did not meet the guideline criteria, not reliable/ Facilitators: prevented patients from unnecessary diagnostic research |

| McIntosh 2017 |

To describe healthcare providers’ perspectives on the facilitators of and barriers to adhering to pediatric diabetes treatment guidelines | MIXED | Mixed methods study Electronic Survey + qualitative interviews |

Canada physicians 41%, nurses 29%, dietitians 22%, others |

SENSE OF BELONGING working collectively provincially; (e.g. telehealth) |

ENVIRONMENTAL inadequate resources (i.e. funding (more diabetes nurse educators needed, mental health support 37%, long waiting times 34%), Time interaction with patients e.g for building trust |

| Storm-Versloot 2012 |

To find out whether a successful multifaceted implementation approach of a local evidence-based guideline on postoperative body temperature measurements (BTM) was persistent over time, and which factors influenced long-term adherence | MIXED | Mixed methods study Patient records were retrospectively examined to measure guideline adherence. Data on influencing factors were collected in focus group meetings for nurses and doctors |

The Netherlands 47 RN + 42 doctors |

ATTITUDE Belief in the advantages of the guideline lack of self-efficacy SENSE OF BELONGING strong staff support |

CPG STRUCTURE (Characteristic, contradictory) controversial nature of the guideline |

| Wolfensberger 2018 |

To identify the optimal behavior leverage to improve Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia (VAP) prevention protocol adherence | MIXED | Mixed methods study Adherence measurements to assess 4 VAP prevention measures and qualitative analysis of semi-structured interviews |

Switzerland 42 nurses and 4 physicians |

ATTITUDE Motivation (reflective motivation, perceived seriousness Self-efficacy Level of Agreement side-effects of prevention measures |

ENVIRONMENTAL Organizational lack of resources equipment and staffing |

| Arzimanoglou 2014 |

To explore how prolonged convulsive seizures in children are managed (status epilepticus CPG) when they occur outside of the hospital | QUAL | Qualitative study Exploratory telephone survey | Multicentric study: seven EU countries (Belgium, France, German, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and UK) 128 HCP, (85 pediatric neurologists and neurologists, 28 community pediatricians, and 15 epilepsies nurses, in the UK and Sweden only) |

KNOWLEDGE Lack of familiarity, lack of awareness; accessibility |

PATIENTS- CAREGIVERS’ ATTITUDE Caregiver’s attitudes, insufficient training; lack of training and fear (teachers, etc.) |

| Bayuo 2017 |

To identify pain management practices in the burn’s units of Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital, compare these approaches to best practice, and implement strategies to enhance compliance to standards | QUAL | Evidence implementation project with Joanna Briggs Institute Practical Application of Clinical Evidence System (PACES) and Getting Research into Practice (GRiP) audit and feedback tool |

Ghana Project team was predominantly constituted by nurses (3 units), as well as from 2 surgeons and a clinical fellow. |

KNOWLEDGE Information accessibility ATTITUDE Outcomes expectancy |

ENVIRONMENTAL Organizational constraints |

| Dogherty 2013 |

To describe the tacit knowledge regarding facilitation embedded in the experiences of nurses implementing evidence into practice. | QUAL | Qualitative study In-depth analysis |

Canada purposive sample- 20 nurses from across Canada, including nurses from across the continuum of care and working with different clinical populations |

Facilitators ATTITUDE Motivation self-efficacy (focus on); sense of belonging (partnership, teamwork) EXTRINSIC FACTORS- CPG STRUCTURE (Characteristics accessibility, relevance, adaptation) Barriers ATTITUDE SENSE OF BELONGING and self-efficacy (poor engagement) |

ENVIRONMENTAL Resources (lack of), conflict, contextual factors, sustainability |

| Efstathiou 2011 |

To study the factors that influence nurses’ compliance with Standard Precaution in order to avoid occupational exposure to pathogens | QUAL | Qualitative study Focus group approach | Cyprus 30 nurses (93.7%) participated (26 females, 4 males) |

ATTITUDE Negative influence of protective equipment Provision of nursing care to children not perceived as dangerous. Influence on nurses’ appearance Psychological factors embarrassment Working experience (more confidence) Physician’s influence (also not wearing protection) |

ENVIRONMENTAL lack of supplies, Availability of equipment time Too busy, lack of nursing personnel, implementation of guidelines is time consuming Organizational constraints, Perceived increase in malpractice Emergency situation PATIENTS- CAREGIVERS’ ATTITUDE Patients’ discomfort Anxiety, sorrow |

| Lai 2019 |

To promote evidence-based practice in screening for delirium in patients in palliative care | QUAL | Evidence implementation project with Joanna Briggs Institute Practical Application of Clinical Evidence System (PACES) and Getting Research into Practice (GRiP) audit and feedback tool |

China 18 nurses |

KNOWLEDGE Lack of knowledge |

ENVIRONMENTAL lack of supplies, resources (screening tools) |

| Lin 2019 | To identify the facilitators of and barriers to nurses’ adherence to evidence based wound care clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) in preventing surgical site infections (SSIs) |

QUAL | Qualitative study incorporating ethnographic data collection techniques Semi-structured individual interviews and focus groups (N = 20), and examination of existing hospital policy and procedure documents. |

Australia convenience sample of 20 nurses who were at work on the days they conducted focus groups |

KNOWLEDGE Facilitators Participants’ active information‐seeking behavior clear understanding of the importance of aseptic technique Barriers Participants’ knowledge and skills deficits regarding application of aseptic technique principles in practice Accessibility: availability of the hospital’s wound care procedure Documents |

PATIENTS- CAREGIVERS’ ATTITUDE Facilitators patient participation in wound care Barriers timing of patient education |

| Lu 2015 |

To examine the current practices for managing emergency equipment in a tertiary mental health institution To determine the strengths and limitations of the existing practice/process. |

QUAL | Evidence implementation project with Joanna Briggs Institute Practical Application of Clinical Evidence System (PACES) and Getting Research into Practice (GRiP) audit and feedback tool |

Singapore Members with experience in various mental health settings and with a role in checking and maintaining the inventory of emergency supplies and equipment |

KNOWLEDGE Lack of training, experience |

ENVIRONMENTAL Characteristic and organizational factors: inadequate knowledge and awareness of the organization’s policy; lack of exposure and skills in operating emergency equipment in the psychiatric setting |

| Makhado 2018 |

To explore and describe barriers to treatment guidelines adherence among nurses initiating and managing anti-retroviral therapy and anti-TB treatment | QUAL | Qualitative exploratory descriptive design Four semi-structured focus group interviews were conducted |

South Africa 24 NIMART nurses |

KNOWLEDGE Insufficient knowledge or lack of awareness ATTITUDES Lack of agreement with guidelines, poor motivation resistance to change |

|

| Meurer 2011 |

To describe barriers to thrombolytic use in acute stroke care | QUAL | Qualitative Study Focus groups and structured interviews (pre-specified taxonomy to characterize barriers) |

USA Phase 1 focus group and interviews of emergency physicians (65), nurses (62), neurologists (15), radiologists (12), hospital administrators (12), and three others (hospitalists and pharmacist). |

KNOWLEDGE Familiarity with, agreement, awareness ATTITUDES Motivation to adhere to the guidelines, lack of self-efficacy and outcome expectancy |

ENVIRONMENTAL availability of intensive care units, ED crowding, pharmacy or radiology PATIENTS- CAREGIVERS’ ATTITUDE failure to recognize symptoms, preference to arrive via car instead of ambulance, delayed presentation CPG STRUCTURE characteristics, issues with the structure or content |

| Munce 2017 |

To understand the factors influencing the implementation of the recommended treatments and Knowledge Translation (KT) interventions (stroke rehabilitation guidelines). |

QUAL | Qualitative study Telephone focus groups were selected because of the geographic dispersion |

Canada Purposive sampling was used to recruit equal numbers of participants across professional groups (11 nurses, 11 therapists, 11 clinical managers), randomization arms (facilitated KT intervention or passive KT intervention), and geographic locations |

ATTITUDES Agreement: clear and practical to follow implementation of recommendations. Barrier when unclear, too general KNOWLEDGE Familiarity with CPG (having some recommendations already in use) lack of familiarity as a barrier (lower volume of patients) SENSE OF BELONGING Team communication and interdisciplinary collaboration |

ENVIRONMENTAL barrier lack of time (time pressure), lack of space and equipment WORKLOAD lack of staff or staff turnover |

| Presseau 2017 |

To inform how to deploy the Individualized Dialysis Temperature (IDT) across many hemodialysis centers, we assessed hemodialysis physicians’ and nurses’ perceived barriers and enablers to IDT use. |

QUAL | Qualitative study Phone Interview Two topic guides using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) to assess perceived barriers and enablers |

Canada nine physicians and nine nurses from 11 Ontario hemodialysis centers |

KNOWLEDGE Awareness of CPG ATTITUDE Benefits and motivation, optimism, reinforcements (It’s a little priority at this point) SENSE OF BELONGING Role identity, beliefs about capabilities; forgetting to prescribe or set IDT |

ENVIRONMENTAL Availability of resources (thermometer for dialysis.) WORKLOAD Reducing episodes of hypotension during dialysis can decrease workload PATIENTS- CAREGIVERS’ ATTITUDE Patient factors: comfort, emotions (Patients may feel too cold on cooler dialysate temperatures) |

| Stenberg 2011 |

To describe influences on health care professionals’ attitudes to CPGs for preventing falls and fall injuries | QUAL | Qualitative study Qualitative approach with focus group. Texts were analyzed using manifest and latent content analysis. |

Sweden 23 HCP Physicians (4), registered nurses (15), physiotherapists (3), and 1 occupational therapist |

ATTITUDE Motivation: experiencing a course of events (falls and fall injuries, from severe trauma such as subarachnoid bleeding and hip fractures to smaller chafes and bruises) Experiencing the benefit previous negative consequences had been reduced or eliminated and, thereby, replaced by positive outcomes since they startedto use the CPG for fall prevention. Individual Resources: being motivated |

ENVIRONMENTAL Influence of social factors community obligations (consider laws and regulations in their decision-making) and organizational (leadership with clear priorities) |

| van de Steeg 2014 |

To identify and classify barriers to adherence by nurses to a guideline on delirium care. | QUAL | Qualitative study Open-ended interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of 63 research participants |

The Netherlands 28 nurses, 18 doctors and 17 policy advisors |

ATTITUDE Motivation (lack of motivation - nurses - lack of clarity of the benefits and goals of screening, results of screening are not directly visible; screening not being part of the essential care for older persons. KNOWLEDGE Nurses conveyed that they had sufficient knowledge and skills to use the screening instrument to identify at risk patients, but Doctors mainly emphasized the importance of additional education for nurses on delirium screening and treatment |

ENVIRONMENTAL Organizational: The social pressure to screen all older patients appears to be limited: it is generally accepted among nurses that other activities take precedent over screening |

| van den Berg 2019 |

To identify barriers and gather improvement suggestions through semi-structured in-depth interviews conducted with 24 professionals working in oncofertility care |

QUAL | Qualitative study Semi-structured in-depth interviews |

The Netherlands 24 professionals working in oncofertility care (Specialized oncology nurse (4%) Specialized breast cancer nurse (17%); Medical oncologist (29%) Surgical oncologist (29%) Gynaecological oncologist (8%) Haematologist (4%) Reproductive gynaecologist (8%) |

KNOWLEDGE AND ATTITUDE Lack of awareness, knowledge, time, and attitude: less aware of discussing fertility in patients who are of a higher age, who have children, who don’t have a (clear) wish to conceive or who have a poor cancer prognosis. |

ENVIRONMENTAL Organizational unavailable written information, disagreement on who is responsible for discussing infertility risks). Patients’ attitude: focus on surviving Cancer; HCPs feel that patients do not place fertility high on their priority list because they are focused on surviving cancer |

| Weller 2020 |

To identify health professional perspectives about using Venous Leg Ulcer (VLU) CPGs to guide the management of people with VLUs in primary care |

QUAL | Qualitative study Semi-structured face-to-face and telephone interviews with health professionals, GPs, and PNs |

Australia and snowball sampling strategies to recruit the participants. 15 GPs (43%) and 20 PNs (57%), including two Aboriginal health nurses (6%), who worked in primary health care settings |

KNOWLEDGE Lack of knowledge and Skills, lack of awareness, ATTITUDES Lack of trust and motivation (better what was done in the past) SENSE OF BELONGING teamwork, collaboration |

ENVIRONMENT Lack of supplies (print and electronic versions of the VLU CPGs) |

| Yanke 2018 |

In this qualitative, descriptive project, 4 focus groups were convened over a 5-month period to identify work system barriers and facilitators to implementation of the VA CDI bundle | QUAL | Qualitative study Four focus groups were conducted 1 with attending physicians, 1 with resident physicians, and 2 with RNs and HTs (n 7) |

USA convenience sample consisted of attending hospitalist physicians, internal medicine resident physicians, and registered nurses (RNs) and health technicians (HTs) employed at our VA hospital |

ENVIRONMENTAL Organizational constraints (testing or obtaining the sample), lack of supplies (soap dispenser or working sinks for hand Hygiene) Culture of institutional support for CIP (contact isolation precautions) compliance and support for independent RN C difficile testing and decision-making |

|

CPG: Clinical Practice Guidelines

HCP: Health Care Professional

GP: General Practitioner

RN: Registered Nurse

RCT: Randomised Controlled Trial

QUAN: Quantitative

QUAL: Qualitative

MIXED: Mixed-Method

Integrated analysis of the major findings

After the data extraction phase, the major findings from each study were analysed by aggregating them into two main themes: Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors. The Intrinsic Factors were then analysed considering the following subthemes: a) knowledge and skills; b) attitudes of health personnel; c) sense of belonging towards guidelines. The Extrinsic Factors were analysed taking into account the following subthemes: a) organizational and environmental factors; b) workload; c) CPGs’ structure; d) patients and caregivers’ attitudes.

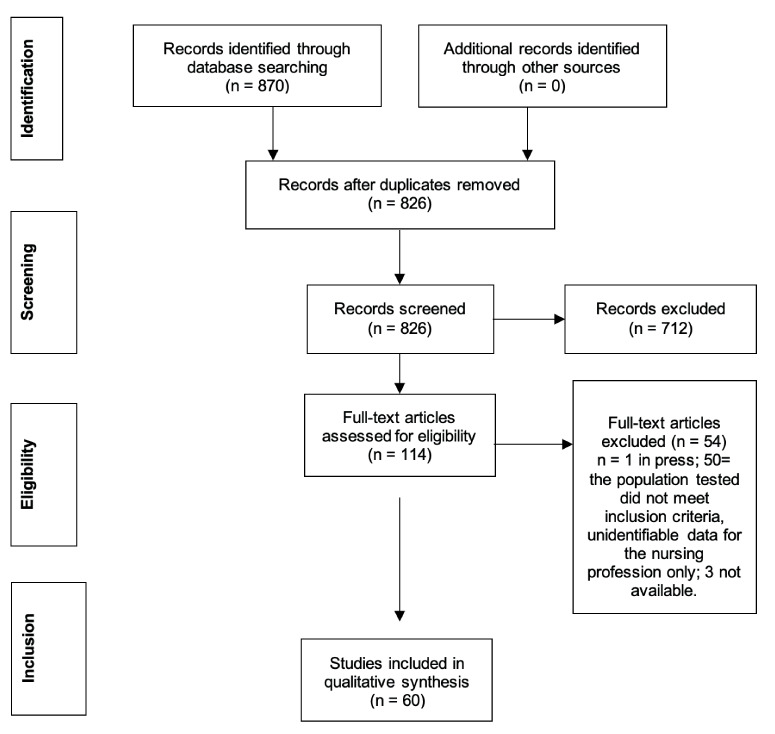

For this mixed-method systematic review, a graphic synthesis of the main results was developed (Fig.3).

Figure 3.

Aggregate analysis of Barriers and Facilitators in nurses’ implementation of CPGs

It aims to give both a qualitative and a quantitative perspective to answer the main research question. The synthesis provided in figure 3 combines the main themes and subthemes adopted with the number of studies that take them into account. Indeed, the area of each theme and subtheme is proportional to the number of studies that report about them.

Intrinsic Factors

Knowledge and skills

Knowledge and skills may represent a facilitating factor for the implementation of CPGs. On the other hand, their lack or inaccessibility could represent an important barrier. Kowitt et al. (25) highlight as educational programmes for infection control implemented hospital-wide (e.g., hand hygiene initiatives) may increase nurses’ overall compliance. Lin et al. (26) identify knowledge and skills as facilitators for the adoption of evidence-based CPGs in preventing surgical site infections: a clear understanding of aseptic techniques together with a proactive attitude toward information seeking can improve the adherence to CPGs in wound care. Conversely, the lack of training when implementing new CPGs can lead nurses to a sense of disorientation and inadequacy, acting as a strong barrier to the CPGs adoption. Senananyake et al. (27) identify lack of education and training as a barrier to effective implementation of a WHO checklist for safe childbirth in Sri Lanka. Similarly, Damush et al. (28) report that nursing staff providing guideline-based care to transient ischemic attack patients in U.S. Veterans Administration Medical Centres perceive inadequate knowledge.

Lack of training and experience is one of the most debated topics, also reported by Lu et al. (24) in describing current practices for managing emergency equipment in a tertiary mental health institution: the authors stress the importance of testing and retraining to maintain the acquired skills. Similar results have been shown in other studies conducted in a wide range of settings, such as cancer and postoperative pain management, oral health care, vascular access management, delirium screening, hand hygiene, and sexually transmitted diseases (23, 29-38). Many authors stress the importance of information accessibility, CPGs familiarity (22,25,39-43) and nursing staff awareness, either demonstrated or perceived (44-51). Jansson et al. (52), in a study on the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia, focus on the lack of guidance as one of the main self-reported barriers towards evidence-based guidelines.

The only divergent opinion is reported in Aloush’s study (53), a randomized controlled trial showing that there is no statistically significant difference in CPG compliance between nurses who have received education on ventilator-associated pneumonia and those who have not.

Attitude of the health personnel

Another important intrinsic factor retrieved from the included study is the attitude of the health personnel. Attitude can be intended as trust and motivation toward CPGs, outcomes expectation, perceived self-efficacy, resistance to adopting new practices (30,33,36,37, 39, 44, 49, 51, 54-60), lack of enthusiasm (29, 32), lack of reinforcements (48), poor engagement (61), fear of adverse events (35, 62-64).

Huis (65) highlights how nurses’ hand hygiene compliance is positively correlated with feedback on their performance: feeling solicited by colleagues to maintain proper hand hygiene behaviour is an aspect of the social component that correlates positively with changes in adherence to CPGs. Another motivating factor identified is the attitude towards patient contact (22,31,66): nurses show greater compliance with hand hygiene performed after patient contact than hand hygiene performed before approaching patients.

Sense of Belonging

The sense of belonging involves the feeling, belief and expectation that one is included in the group and has a place there. It concerns the sense of acceptance and willingness to sacrifice oneself for the group (67-69).

Regarding sense of belonging, Knops et al. (67) emphasize the importance of a favourable social context and Dogherty et al. (61) highlight the importance of partnership and teamwork. In Munce et al. (41), team communication and interdisciplinary collaboration emerged as facilitating factors for stroke rehabilitation CPGs implementation. Participants in Weller’s research (51) identified teamwork, collaboration and shared decision making as the elements that enhance the sense of belonging and the achievement of common goals. Similarly, in McIntosh et al. (70) working collectively at a provincial level was the main theme identified by the health providers to overcome the barrier to paediatric diabetes CPGs adherence.

In Presseau et al. (48), the sense of belonging is undermined by the lack of professional role identity: in fact, nurses report having to adapt exclusively to doctor’s orders. These results partially overlap with those of Harillo-Acevedo et al. (69) and other studies on lack of cooperation and trust (33,54).

Extrinsic Factors

Environmental and organizational factors

The most frequently identified factors that hindered the use of CPGs were the environmental ones such as lack of resources, environmental characteristics, organizational constraints, and leadership style. Of the 60 studies analysed, 47 considered environmental factors as barriers or facilitators to CPGs adherence. Resources can be represented by availability of drugs, supplies, appropriate instrumentation (23,28,29,32,42,48,51,57,58,60,61,63,71-77), time (29,32,33,41,46,49,50,52,57,70,74,75) or cost reimbursement, e.g., the lack of community resources for referral to specific services (74).

Environmental characteristics and organizational constraints could represent a big issue in CPGs implementation and a challenge to be faced through educational and organizational interventions, as well as leadership support. Crowding (39,66), lack of coordination (28,56) or supervision from the institutional level (27,49) are factors that must be managed. Leadership style correlates positively with changes in nurses’ compliance (65) and in defining priorities (62) as the workplace culture play an important role in terms of facilitating factor (78).

Workload

The workload represents an extrinsic factor emphasized by many studies and, even if it refers to the environmental/organizational factors, in the present review it has been analysed separately.

Aloush’s studies describe a strong relationship in terms of number of beds per unit and nurse-to-patient ratio, as a factor influencing the compliance of the entire nursing staff (53,71). Nursing personnel working in units with fewer beds and a 1:1 nurse to patient ratio had statistically significant higher compliance scores than those employed in units with more beds and a 1:2 nurse to patient ratio. Muller (66) comes to different conclusions, saying that daily patient volumes and nursing working hours are not associated with hand hygiene compliance, but it could be seen better compliance during the night shifts and the weekend (25). However, the shortage of nursing staff that means a) to downsize the time available to follow the recommendations, b) to be often alone during the working shift, c) to feel a higher work pressure, are all widely discussed factors that greatly affect guidelines adherence (27,31,41,44,48,49,51,64,72,79-81).

CPGs’ structure

Few studies, among the ones included in the present review, reported guideline characteristics such as trustworthiness, clarity, and degree of complexity as potential barriers to adherence. The studies describe the lack of guideline familiarity as a large component of the above-mentioned barriers (39), too much time required to document properly the recommended actions of care (64), poor accessibility or lack of structural resources (51,61) poor usefulness in daily practice (33,67), contradictory content, lack of clarity or poor usability (49, 54).

Patients and caregivers’ attitude

A widely debated aspect concerns possible frailties or difficulties shown by patients regarding the application of the CPGs recommendations; the present review also considers the possible barriers acted by the patients’ caregivers.

Features such as gender, ethnicity, attitudes, or payer source can affect the patient and even the nurse in adhering to guideline-based screening campaigns, such as those for smoking described by Cato (38) or Katz (56). A facilitator for nurses has always been the level of active participation shown by the patient (26). On the other side, an attitude of reluctance, such as rejection to rely on opioids for pain control, may be a barrier to appropriate care management (29). The patient is not always able to follow the directions causing involuntary delays in the provision of care (32,39,52,70), not feeling comfortable with them (47-49,57,74,75,82) or not considering them a priority (60). Moreover, in some cases, the clinical characteristics do not allow the guidelines to be applied (43,73).

Concerning the caregivers, they play a very important role in paediatric studies. Arzimanoglou et al. (40) report that in children affected by convulsive seizures the caregivers (teachers) show resistance, fear and a lack of systematic training. Løyland et al. (31) report that, in case of hospitalization, hygiene measures are conditioned by parents kissing or having close contact with their children. In general, it is sometimes possible to witness an opposing attitude from the relatives (42) and, in the case of venereal diseases such as syphilis, a lack of adherence of the partner conditioning the success of the treatments (34).

Conclusion

The present mixed-method review has shown that intrinsic and extrinsic factors in CPGs implementation are almost equally distributed in the included studies, with a slight prevalence of the latter (Fig.3). Among extrinsic factors, the environmental ones are prevalent, while among intrinsic factors, attitude and skill-knowledge are equally represented. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors could either play the role of barriers or facilitators, as also emerged from the previous integrative review by Jun et al (12). Considering nursing personnel, the studies included in the present review report the lack of resources as the main barrier perceived by nurses. Particularly, in low-income countries, lack of supplies remains one of the major problems (e.g., water for performing hand hygiene) and nurses, who are at the forefront in addressing the direct application of knowledge and skills to ensure patient safety, have a higher perception of this kind of barrier than other healthcare personnel (20).

On the other hand, the results of the present review highlight a series of potential facilitators such as having good feedback at the workplace, positive reinforcements, either from the members of the team or from the leaders. Leadership, but also the level of active participation of the patient and caregiver in care processes could have a positive impact. Indeed, the present review considers also factors related to patients and caregivers’ behaviours that could be perceived as possible barriers/facilitators by nurses.

A possible limitation of the present study is the choice to include all care settings and nursing fields. This choice is because the authors’ goal was to provide a broad perspective of the review topic. Indeed, choosing a mixed-method approach, that represents an element of novelty of the present review, has allowed a wider understanding of the phenomenon. Considering not only quantitative studies, but also qualitative and mixed methods has provided multiple perspectives of the factors related to CPGs implementation and adherence.

Another limitation that emerged in conducting the present review is the extraction of data pertaining specifically to nursing staff. The purpose of this study was to synthesize the available literature on extrinsic and intrinsic factors that act as barriers or facilitators in CPG implementation, focusing on nursing staff, but the process of knowledge translation and guideline adoption is mostly reported as a team-related issue.

Proactive identification of barriers and facilitators is a key factor in developing and implementing strategies to increase guidelines adherence. Anyway, CPGs’ implementation remains a complex process, which can only be based on policies promoted at a managerial level, within the framework of continuing education programs for nursing staff and in a context of shared goals (12,83,84). Moreover, a similar pathway to raising awareness about the importance of CPGs adherence should be provided in undergraduate and postgraduate education, also by defining specific assessment measures, as there are distinctive differences in the factors influencing students’ clinical decision making compared with that of registered nurses regarding the use of CPGs (85).

As aforementioned, implementing and maintaining a high level of adherence to CPGs over time is a complex process, resulting in a strong recommendation to support health policymakers and nursing leaders in promoting both core and continuing education programs.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my very great appreciation to Prof. Follenzi, Course Coordinator of the PhD. Program in “Food, Health and Longevity”, for giving me this opportunity.

Funding Statement

This study was partially funded by the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research Translational Medicine, Università del Piemonte Orientale.

Conflict of Interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Authorship statement

All listed authors meet the authorship criteria and agree with the content of the manuscript.

References

- Graham R, Mancher M, Miller Wolman D, Greenfield S, Steinberg E. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust, IOM, Ed, Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francke A, Smit M, de Veer A, Mistiaen P. Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals: a systematic meta-review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2008;8:38. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-8-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugtenberg M, Zegers-van Schaick J, Westert G, Burgers J. Why don’t physicians adhere to guideline recommendations in practice? An analysis of barriers among Dutch general practitioners. Implement Sci. 2009;4:54. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiffer M. Utilization of Clinical Practice Guidelines: Barriers and Facilitators. Nurs Clin North Am. 2015;50(2):327–345. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciro Correa V, Lugo-Agudelo L, Aguirre-Acevedo D, et al. Individual, health system, and contextual barriers and facilitators for the implementation of clinical practice guidelines: a systematic metareview. Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18:74. doi: 10.1186/s12961-020-00588-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arts D, Voncken A, Medlock S, Abu-Hanna A, van Weert H. Reasons for intentional guideline non-adherence: A systematic review. Int J Med Inform. 2016;89:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoon D, Rietbergen T, Huis A, et al. Implementation strategies used to implement nursing guidelines in daily practice: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;111:103748. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, van Stralen M, West R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan R, Deci E. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55:68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdud M, Cabasés J, Nieto J. Incentives and intrinsic motivation in healthcare. Gac Sanit. 2016;30(6):408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2016.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaddis G, Greenwald P, Huckson S. Toward improved implementation of evidence-based clinical algorithms: clinical practice guidelines, clinical decision rules, and clinical pathways. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(11):1015–1022. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun J, Kovner C, Witkoski Stimpfel A. Barriers and facilitators of nurses’ use of clinical practice guidelines: An integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;60:54–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Q, Pluye P, Bujold M, Wassef M. Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Syst Rev. 2017;6:61. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0454-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson A, White H, Bath-Hextall F, Salmond S, Apostolo J, Kirkpatrick P. A mixed-methods approach to systematic reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):121–131. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern C, Lizarondo L, Carrier J, et al. Methodological guidance for the conduct of mixed methods systematic reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2108–2118. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20(1):37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hong Q, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. 2018;34(4):285–291. [Google Scholar]

- Hong Q, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, et al. Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: a modified e-Delphi study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;111:49–59.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabana M, Rand C, Powe N, Wu A, Wilson M, Abboud P, Rubin H. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis J, Koch G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayuo J, Munn Z, Campbell J. Assessment and management of burn pain at the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital: a best practice implementation project. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2017;15(9):2398–2418. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai X, Huang Z, Chen C, Stephenson M. Delirium screening in patients in a palliative care ward: a best practice implementation project. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2019;17(3):429–441. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Ng H, Xie H. Translating the evidence for emergency equipment and supplies into practice among healthcare providers in a tertiary mental health institution: a best practice implementation project. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13(4):295–308. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2015-2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowitt B, Jefferson J, Mermel L. Factors Associated with Hand Hygiene Compliance at a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(11):1146–1152. doi: 10.1086/673465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin F, Gillespie B, Chaboyer W, et al. Preventing surgical site infections: Facilitators and barriers to nurses’ adherence to clinical practice guidelines-A qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(9-10):1643–1652. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senanayake H, Patabendige M, Ramachandran R. Experience with a context-specific modified WHO safe childbirth checklist at two tertiary care settings in Sri Lanka. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):411. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2040-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damush T, Miech E, Sico J, et al. Barriers and facilitators to provide quality TIA care in the Veterans Healthcare Administration. Neurology. 2017; 12;89(24):2422–2430. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jho H, Kim Y, Kong K, et al. Knowledge, practices, and perceived barriers regarding cancer pain management among physicians and nurses in Korea: a nationwide multicenter survey. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e105900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Steeg L, Langelaan M, Ijkema R, Nugus P, Wagner C. Improving delirium care for hospitalized older patients. A qualitative study identifying barriers to guideline adherence. J Eval Clin Pract. 2014;20(6):813–9. doi: 10.1111/jep.12229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L⊘yland B, Wilmont S, Cohen B, Larson E. Hand-hygiene practices and observed barriers in pediatric long-term care facilities in the New York metropolitan area. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(1):74–80. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzv097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton S, Sheppard J, Hemsley B. Feasibility of implementing oral health guidelines in residential care settings: views of nursing staff and residential care workers. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;30:194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trogrlic Z, Ista E, Ponssen H, et al. Attitudes, knowledge and practices concerning delirium: a survey among intensive care unit professionals. Nurs Crit Care. 2017;22(3):133–140. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues D, Domingues R. Management of syphilis in pregnancy: Knowledge and practices of health care providers and barriers to the control of disease in Teresina, Brazil. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2017;33(2):329–344. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avedissian T, Honein-AbouHaidar G, Dumit N, Richa N. Anaphylaxis management: a survey of school and day care nurses in Lebanon. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2018;2(1):e000260. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2018-000260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaszek L, Dezbska G. Knowledge, compliance with good clinical practices and barriers to effective control of postoperative pain among nurses from hospitals with and without a “Hospital without Pain” certificate. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27:1641–1652. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Aparicio S, Guitard Sein-Echaluce M, Palomar Martínez M. Barreras y facilitadores en la adherencia al core bundle para prevenir complicaciones asociadas a dispositivos de acceso vascular. Metas Enferm. 2019;22(1):14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cato K, Hyun S, Bakken S. Response to a Mobile Health Decision Support System for Screening and Management of Tobacco Use. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(2):145–152. doi: 10.1188/14.ONF.145-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meurer W, Majersik J, Frederiksen S, Kade A, Sandretto A, Scott P. Provider perceptions of barriers to the emergency use of tPA for Acute Ischemic Stroke: A qualitative study. BMC Emerg Med. 2011;11:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]