Abstract

Protein mass spectrometry and molecular cloning techniques were used to identify and characterize mobile o-halobenzoate oxygenase genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain JB2 and Pseudomonas huttiensis strain D1. Proteins induced in strains JB2 and D1 by growth on 2-chlorobenzoate (2-CBa) were extracted from sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels and analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry. Two bands gave significant matches to OhbB and OhbA, which have been reported to be the α and β subunits, respectively, of an ortho-1,2-halobenzoate dioxygenase of P. aeruginosa strain 142 (T. V. Tsoi, E. G. Plotnikova, J. R. Cole, W. F. Guerin, M. Bagdasarian, and J. M. Tiedje, Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2151–2162, 1999). PCR and Southern hybridization experiments confirmed that ohbAB were present in strain JB2 and were transferred from strain JB2 to strain D1. While the sequences of ohbA from strains JB2, D1, and 142 were identical, the sequences of ohbB from strains JB2 and D1 were identical to each other but differed slightly from that of strain 142. PCR analyses and Southern hybridization analyses indicated that ohbAB were conserved in strains JB2 and D1 and in strain 142 but that the regions adjoining these genes were divergent. Expression of ohbAB in Escherichia coli resulted in conversion of o-chlorobenzoates to the corresponding (chloro)catechols with the following apparent affinity: 2-CBa ≈ 2,5-dichlorobenzoate > 2,3,5-trichlorobenzoate > 2,4-dichlorobenzoate. The activity of OhbABJB2 appeared to differ from that reported for OhbAB142 primarily in that a chlorine in the para position posed a greater impediment to catalysis with the former. Hybridization analysis of spontaneous 2-CBa− mutants of strains JB2 and D1 verified that ohbAB were lost along with the genes, suggesting that all of the genes may be contained in the same mobile element. Strains JB2 and 142 originated from California and Russia, respectively. Thus, ohbAB and/or the mobile element on which they are carried may have a global distribution.

Halobenzoates and related chemicals that occur in the environment have both natural and anthropogenic origins (21, 36). The latter include the use of halobenzoates as herbicides and formation during microbial degradation of these compounds (24). Chlorobenzoates (CBas) are also intermediates produced during aerobic biodegradation of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and in this process CBa degradation is important as accumulation of metabolites produced from CBas (i.e., chlorocatechols and protoanemonin) may result in feedback inhibition and impede PCB biotransformation (1, 7, 8, 25, 48, 49). Thus, optimization of CBa degradation by using inoculants or genetically engineered strains can improve the effectiveness of PCB bioremediation (5, 16, 26, 29, 31, 39–41).

The ability of bacteria to grow with one or more CBa isomers as a sole carbon and energy source(s) is well documented (19, 23). While several strains have been reported to utilize 2-chlorobenzoate (2-CBa) as a growth-supporting substrate (13, 15, 17, 27, 37, 42, 47, 50), organisms with this phenotype appear to be isolated less frequently than organisms that are able to utilize 3- or 4-CBa. The molecular genetics and physiology of 2-CBa degradation have been studied in detail in two organisms, Burkholderia cepacia strain 2-CBS and Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain 142. In both of these strains, 2-CBa metabolism is initiated by an ortho-halobenzoate dioxygenase that effects regiospecific 1,2-dihydroxylation, and there is a subsequent spontaneous loss of the halide and carbon dioxide, resulting in catechol as the product (18, 22, 43, 46, 52). Both of the enzymes are selective for o-halobenzoates (18, 43, 52).

While the o-halobenzoate dioxygenases of strains 2-CBS and 142 are similar in terms of the unique transformation that they mediate, the enzymes and the genes that encode them differ in at least four ways. First, in strain 2-CBS the genes encoding the large (α) and small (β) subunits of the oxygenase are clustered with a gene encoding the electron transport component of the oxygenase (22). However, in strain 142 the genes encoding the α and β subunits (ohbB and ohbA, respectively) are segregated from the genes encoding the electron transport components, and it has been postulated that to create a functional enzyme, OhbAB join with proteins that are encoded elsewhere in the genome (52). Second, the o-halobenzoate dioxygenase activity of strain 142 increases with decreasing electronegativity of the ortho halogen substituent, whereas the strain 2-CBS enzyme shows the opposite trend (18, 43). Third, the activity of the strain 2-CBS o-halobenzoate dioxygenase with dihalobenzoates is low compared to that of the strain 142 enzyme (18, 43). Fourth, the α and β subunits of the two oxygenases exhibit relatively low levels of sequence identity with each other (22 and 14%, respectively) but significant levels of identity with benzoate/toluate dioxygenase in the case of strain 2-CBS and with salicylate 5-hydroxylase/nitrotoluene dioxygenase/biphenyl dioxygenase in the case of strain 142. Thus, the o-halobenzoate dioxygenases of strains 2-CBS and 142 are functionally similar, but they represent two different lineages with distinct activities.

P. aeruginosa strain JB2 is an o-halobenzoate degrader which appears to differ from strains 2-CBS and 142 in terms of the spectrum of o-halobenzoates that are utilized as growth substrates (27). In the present study, we used matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) to facilitate identification of the mobile o-halobenzoate degradation functions in P. aeruginosa JB2 and Pseudomonas huttiensis D1. In previous investigations, we demonstrated that the o-halobenzoate degradation phenotype could be transferred from strain JB2 to strain D1 and identified ca. 26 kb of DNA acquired by the latter organism (28, 38). However, genes encoding an o-halobenzoate oxygenase were absent from this region. As we report below, MALDI-TOF MS analysis allowed us to identify such an enzyme in fractionated and whole-cell protein preparations, which in turn facilitated subsequent cloning, heterologous expression, and functional analysis of this enzyme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, culture media, and DNA manipulations.

The sources of P. aeruginosa JB2, P. huttiensis D and D1, and Escherichia coli JM109 have been described previously (27, 28, 38). E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS (Promega, Madison, Wis.) was used for T7-directed expression of genes cloned into pET5a (Promega). Pseudomonads were grown on a mineral salts medium (MSM) as described previously (27). E. coli cultures were routinely grown on Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg ml−1) and chloramphenicol (35 μg ml−1) as appropriate for plasmid selection. Genomic DNA preparation, agarose gel electrophoresis, restriction enzyme digestion, DNA ligation, and E. coli transformation were performed by using standard procedures (4).

Protein analyses.

The initial experiments were done with cellular proteins that were extracted from approximately 3 g (wet weight) of cells and fractionated into soluble and particulate components. For these experiments, strain D1 was grown in 10 liters of MSM with either 2-CBa (3.2 mM) or benzoate (Ba) (4.1 mM) as the carbon source. The cultures were harvested in the late log phase by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 15 min) and washed with the phosphate buffer used in MSM. The cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 10 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 5% sucrose, 10 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) to a density of 500 mg (wet weight) ml−1 and subjected to sonic disruption (four to six 30-s bursts, 30 W each). Nonlysed cells were removed by low-speed centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min), and the lysates were separated into a particulate fraction (containing cell envelope components, intracellular membranes, and cosedimenting macromolecules) and a soluble fraction by centrifugation (150,000 × g, 2 h, 4°C) with a Beckman Ti 70.1 rotor in a Beckman LB 70 ultracentrifuge (Beckman-Coulter, Fullerton, Calif.). In a subsequent analysis of strain JB2, cultures were grown in 100 ml of MSM with either Ba or 2-CBa as the carbon source, and the cells were harvested by centrifugation and then resuspended in 100 μl of phosphate buffer. The suspension was mixed with 100 μl of 2× sample buffer (4), and the cells were lysed by immersion for 3 min in boiling water.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed with a Laemmli discontinuous buffer system (32). The stacking and resolving gels were buffered with Tris-HCl and contained acrylamide at concentrations of 4 and 10%, respectively. Tris-Tricine was used as the tank buffer (45). Gels were cast in plates (16 by 16 cm) of an SE600 vertical slab gel electrophoresis unit (Hoeffer Scientific, San Francisco, Calif.). All chemicals used during preparation of the gels were obtained from Bio-Rad (Richmond, Calif.). The protein concentrations of the samples were determined by the Bradford method (9), using bovine serum albumin as the standard. Proteins (total weight, 10 μg) were stacked for 1.5 h at 50 V and then electrophoresed through the resolving gel for 12 h at 75 V. Chilled (15°C) water was circulated through the heat exchanger of the electrophoresis unit throughout the experiment. Gels were fixed, stained with Coomassie blue R-250, and destained by standard procedures (4). SDS-PAGE results were recorded by digital imaging with a Kodak Image system (Eastman-Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.) or by drying between acetate films.

Proteins were extracted from SDS-PAGE gels and peptides were prepared for analysis by MALDI-TOF MS as described by Gharahdaghi et al. (20). Samples were analyzed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Biotechnology Center with a Bruker Biflex MALDI-TOF MS mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, Mass.) operated in the reflector mode for resolution of monoisotopic peaks. Samples (0.6 μl) were mixed on the target with an equal volume of matrix solution (70% acetonitrile, 30% double-distilled H2O) that was saturated with α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid and contained 0.2% (vol/vol) trifluoroacetic acid as the cationizing agent. Mass spectra were acquired with 800 to 1,200 laser shots per sample. The spectra were manually scanned in the range from 800 to ca. 3,600 Da for clearly resolved monoisotopic peaks, which were selected to generate peak lists for database searches with Mascot (www.matrixscience.com). The search parameters used were trypsin digest, carbamidomethylation of cysteines, monoisotopic mass values, unrestricted protein mass, unrestricted organism type, peptide mass tolerance of ±0.5 kDa, peptide charge state of +1, and allowing a maximum of one missed cleavage. We limited the query results to reporting the 20 proteins giving the best matches.

PCR and Southern hybridization.

The PCR primers designed and the genes targeted by various primer pairs are summarized in Table 1 and Fig. 1, respectively. All of the primers targeted sequences in putative coding regions based on sequence data for P. aeruginosa 142 (GenBank accession number AF1211970). The thermal cycling parameters used to amplify ohbA, ohbB, or ohbAB for cloning or sequencing were a 5-min hot start at 95°C, followed by 15 cycles of program one (denaturation for 30 s at 94°C, annealing for 30 s at 58°C, and extension for 2 to 5 min at 72°C) and then 20 cycles of program two (denaturation for 30 s at 94°C, annealing for 30 s at 62°C, extension for 2 to 5 min at 72°C, with final extension for 7 min at 72°C). In PCR experiments in which we examined the location of genes adjoining ohbAB, the annealing temperatures were decreased to 55 and 58°C in programs one and two, respectively. The minimum length of the extension step in both programs was 2 min; this was increased to 3 min when the PCR products were expected to be between 2 and 2.9 kb long and to 5 min when the PCR products were between 3 and 5 kb long. For the PCR experiments in which genes adjoining ohbAB were examined, a second round of tests were done, in which the extension step in both programs was 5 min regardless of the expected size of the PCR product. All reaction mixtures (total volume, 50 μl) contained 3 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega), each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 0.2 mM, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 200 ng of template DNA, each primer at a concentration of 0.4 μM, 1 M betaine, and 2%(vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide. Reaction mixtures that were used to generate products for cloning or sequencing were cleaned up by using a Qiaquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). Southern hybridization was done as described previously (28) under high-stringency conditions.

TABLE 1.

Summary of PCR primers used in this study

| Primera | Position (bases)b | Sequence (5′–3′) | Enzyme sitec | Melting temp (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ohbA142-F (1) | 2,759–2,788 | GAG GGT CAA GAG GAG GGA GAG TTG ATG AAC | 64.8 | |

| ohbA142-R (2) | 3,305–3,281 | GGC GCA CGA GGA GCG TGT CGA TTA A | 66.6 | |

| ohbB142-F (3) | 3,352–3,374 | CAA TGA CCA ACG TAT CGC CCC AG | 61.5 | |

| ohbB142-R (4) | 4,621–4,593 | GCT TGG CTC GGT TCA GG ATA TGG AAG TC | 65.9 | |

| ohbB′142-F (5) | 3,340–3,368 | CAG GAG AGG ATC CAA TGA CCA ACG TAT CG | BamHI | 63.6 |

| ohbB′142-R (6) | 4,632–4,608 | CAC TCG AGG AAG CTT GGC TCG GTT C | HindII | 64.8 |

| ohbAB142-F (7) | 2,770–2,798 | GGA GGG AGA GCA TAT GAA CAC CGA TAG TC | NdeI | 63.2 |

| ohbAB142-R (8) | 4,655–4,635 | GCG CCG CGG ATC CCT CTA GGC | BamHI | 67.7 |

| ohbRB142-F (9) | 1,641–1,666 | GAA CTC ATG AAG CGG ATG GCT CGT CG | 64.9 | |

| ohbRB142-R (10) | 4,627–4,606 | GAG GCC GCT TGG CTC GGT TCA G | 65.9 | |

| ohbRT142-F (11) | 1,641–1,665 | GAA CTC ATG AAG CGG ATG GCT CGT C | 63.1 | |

| ohbRT142-R (12) | 5,732–5,709 | CGT ATG ACA CTG CGG CTG CAT GAG | 63.6 | |

| ohbTT142-F (13) | 353–382 | GCC GGT CTG TCT CAC TCT CAT GCA AAG GTA | 66.7 | |

| ohbTT142-R (14) | 5,744–5,718 | GTG GAC GGA TTC CGT ATG ACA CTG CGG | 66.2 |

The numbers in parentheses are the numbers used in Fig. 1. The suffix F indicates a forward primer, and the suffix R indicates a reverse primer.

The base numbers refer to the base numbers reported for P. aeruginosa 142 (GenBank accession no. AF121970).

Restriction enzyme site introduced by the primer at the underlined bases.

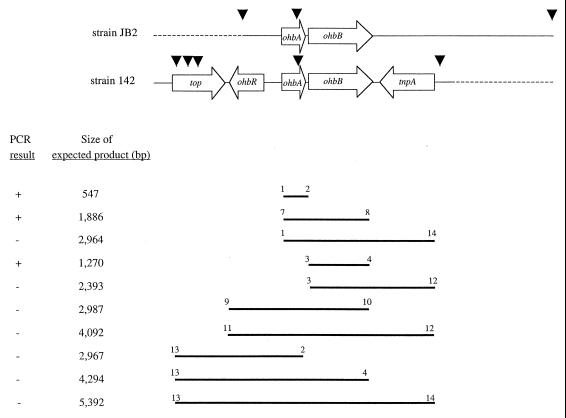

FIG. 1.

Map of the ohb regions from P. aeruginosa 142 (adapted from reference 52) and P. aeruginosa JB2 and summary of PCR and Southern hybridization analyses performed with the latter strain. The arrows indicate gene orientations, and the dashed lines represent regions for which sequence information is unavailable in the case of strain 142 or was beyond the limits of DNA detected by hybridization as contiguous with ohbAB in the case of strain JB2. The lines below the map indicate sections examined by PCR for conservation of structure. The numbers at the ends of the lines indicate the primers used in the tests (Table 1). The data on the left indicate the sizes of the expected PCR products and whether these data were obtained in the experiment indicated. The solid triangles indicate the locations of AvaII sites. Genes are abbreviated as follows: top, topoisomerase gene; ohbR, gene for Lys-R type of regulatory protein; ohbA, o-1,2-halobenzoate dioxygenase β subunit gene; ohbB, o-1,2-halobenzoate dioxygenase α subunit gene; tnpA, transposase gene.

Heterologous expression.

The PCR-amplified ohbAB genes obtained with primers 7 and 8 (Table 1) were digested with NdeI and BamHI and ligated into NdeI/BamHI-digested pET5a. In the resulting construct (pGS2), ohbAB were oriented so that they could be expressed under control of the T7 promoter. The construct was transformed into E. coli JM109, and its structure was confirmed by restriction enzyme analysis. The construct was then harvested from strain JM109 and transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS for expression. Induction was performed as described previously (28). Aliquots of induced cells were resuspended in 10 ml of 3 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7) to a final density of 2.6 × 109 CFU ml−1. A culture of E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS carrying pET5a was treated identically and used as a negative control. Test substrates were added to the cultures and to medium blanks from filter-sterilized aqueous stocks. When pyruvate was included in reaction mixtures, it was added from a filter-sterilized, 1 M stock solution to a final concentration of either 10 or 40 mM. Incubation was carried out at 30°C for up to 5 h. Periodically, aliquots were taken from the vessels, the cells were removed by centrifugation (16,000 × g, 1 min), and the supernatants were transferred to vials for analysis by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described previously (28). At the end of the incubation period, each remaining cell suspension was centrifuged, and the supernatants were removed and used for extraction and analysis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry as described previously (28). Chlorocatechols used as chromatography standards were obtained from Helix Biotechnology (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada)

Nucleotide sequence determination and analysis.

Cycle sequencing was done by using the ABI Prism BigDye terminator chemistry (PE Applied Biosystems). Samples were analyzed with an ABI PRISM 373 DNA sequencer (PE Applied Biosystems) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Biotechnology Center. Nucleotide and amino acid sequence homologies were determined by performing BLAST-N and PSI-BLAST searches (2, 3). Multiple-sequence alignments were assembled by using CLUSTAL-W (51).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification and analysis 2-CBa-induced proteins.

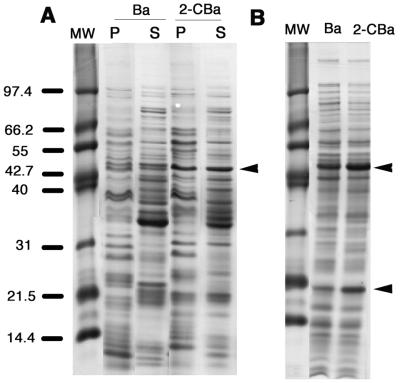

In the fractionated cell extracts from strain D1, a protein band at ca. 48 kDa was intensified in the preparation from the 2CBa-grown culture (Fig. 2A). This size was in the size range for the α subunits of a variety of oxygenases, including o-halobenzoate dioxygenases (6, 10, 22, 35, 43, 52), and the band was excised from the soluble-fraction sample for analysis. From the MALDI-TOF MS spectrum, 14 monoisotopic trypic peptide peaks ranging in mass from 1,102 to 3,691 Da were selected for the database search list. The query returned a highly significant match (molecular weight search [MOWSE] algorithm score, 94) with OhbB (predicted Mr, 48,794), which is the α subunit of the o-1,2-halobenzoate dioxygenase from P. aeruginosa 142 (43, 52). None of the other top 20 proteins gave a significant match (MOWSE scores, <64). Eight of the selected peptides matched OhbB and collectively accounted for 29% of the peptide (Table 2). OhbB was also identified by MALDI-TOF MS in the 48-kDa band from the particulate fraction (data not shown). This protein is not predicted to be membrane bound; thus, its detection in the particulate fraction may have resulted from interaction with integral membrane proteins and/or cosedimentation of OhbB with the particulate fraction.

FIG. 2.

SDS–10% PAGE analysis of P. huttiensis D1 (A) and P. aeruginosa JB2 (B). The strain D1 proteins were obtained from cultures grown on Ba or 2-CBa that were fractionated into soluble (lanes S) and particulate (lanes P) components. Whole-cell protein profiles for strain JB2 were obtained by using cultures grown on the substrates indicated. The sizes of proteins electrophoresed as standards in lanes MW are indicated on the left. The arrowheads indicate the positions of the 48-kDa band that was analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS from the 2-CBa-grown cultures of both strains and the 21-kDa band that was analyzed from 2-CBa-grown strain JB2.

TABLE 2.

Peptides identified by MALDI-TOF MS from the 48-kDa protein bands of strains JB2 and D1 as matching OhbB

| Strain | MOWSE scorea | Peptide massb

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,006 Da | 1,137 Da | 1,320 Da | 1,357 Da | 1,364 Da | 1,583 Da | 1,727 Da | 2,070 Da | 2,242 Da | 2,270 Da | 2,432 Da | 3,238 Da | 3,623 Da | ||

| D1 | 94 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| JB2 | 104 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

MOWSE scores were computed as follows: −10 × log(p), where p is the probability that the observed match is a random event. Scores greater than 67 are significant (P < 0.05).

+, peptide was present in the spectrum of the sample.

Whole-cell (nonfractionated) protein extracts from 2-CBa-grown P. aeruginosa JB2 also yielded an intensified band in the 48-kDa region and an intensified ca. 21-kDa band (Fig. 2B). Both of these bands were extracted for analysis. From the spectrum of the 48-kDa band, 17 clearly resolved peaks ranging in mass from 887 to 3,623 Da were selected for a database search. The query returned a highly significant match (MOWSE score, 104) with OhbB; eight of the selected peptides matched and collectively accounted for 37% of the peptide (Table 2). All other matches were insignificant (MOWSE scores, ≤50). From the MALDI-TOF MS spectrum of the 21-kDa band, 12 peaks ranging in mass from 1,274 to 2,100 Da were used in a database search. The only significant match was with OhbA of P. aeruginosa 142 (MOWSE score, 84). The seven peptides matching OhbA (masses, 1,360, 1,552, 1,567, 1,856, 2,013, and 2,084 Da) accounted for 52% of the polypeptide (predicted Mr, 20,252).

Cloning and characterization of ohbAB homologs.

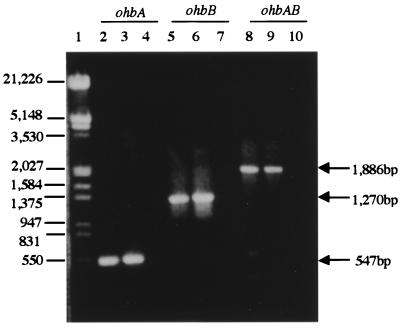

The expected PCR products for ohbA, ohbB, and ohbAB were obtained from strains JB2 and D1 but not from strain D (Fig. 3). The sequences of the ohbA PCR products from strains JB2 and D1 were identical to each other and to the sequence of the ohbA PCR product from strain 142. The sequences of the ohbB PCR products from strains JB2 and D1 were also identical to each other, but they differed slightly from the sequence of the ohbB PCR product from strain 142, having three amino acid substitutions in the polypeptide predicted for OhbBJB2. These substitutions were Asn for Lys-117, Phe for Cys-392, and Val for Ala-393. The fact that the same sequence was obtained independently for ohbB from strains JB2 and D1 indicated that the differences were not attributable to errors in PCR and/or sequencing. While PCR amplification of ohbA or ohbB individually established the presence of these genes, amplification of ohbAB as a unit verified that these genes were contiguous in the predicted orientation.

FIG. 3.

Detection of ohbA and ohbB homologs by PCR. The genomic DNA used as templates were from P. aeruginosa JB2 (lanes 2, 5, and 8), P. huttiensis D1, (lanes 3, 6, and 9), and P. huttiensis D (lanes 4, 7, and 10). The genes and combination of genes targeted are shown at the top, and the expected sizes of the PCR products for the targeted regions are indicated on the right. Lane 1 contained EcoRI/HindIII-digested λ DNA. The fragment sizes (in base pairs) are indicated at left.

The results of all PCR tests to amplify ohbA, ohbB, or ohbAB along with a gene predicted from the strain 142 sequence to be immediately upstream or downstream of ohbAB were negative (Fig. 1). The length of the extension step was at least sufficient for synthesis of the products targeted (and it often exceeded the length required), and the annealing temperatures were at least 5°C below the lower of the two melting temperatures for the primer pair used. Thus, we believe that negative PCR results were not attributable to restrictive thermal cycling parameters. Instead, lack of amplification suggested that in strains JB2 and D1 the genes bordering ohbAB differed from the genes identified in strain 142. These experiments were designed to ascertain the locations of genes relative to ohbAB, not the presence or absence of another gene (or homolog) anywhere in the genome of strain JB2 or D1. It is also possible that similar but not identical genes (e.g., different regulatory elements) could border ohbAB in strains JB2 and D1 and in strain142. However, given that ohbA in strains JB2 and D1 was identical to ohbA in strain 142 and ohbB was nearly identical, the difference could still represent significant divergence in the structure or evolutionary lineage of these genes.

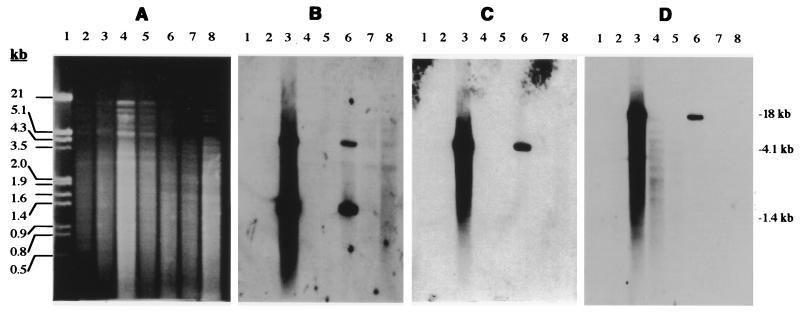

The structure was also investigated by performing Southern hybridization with AvaII-digested genomic DNA of strains JB2 and D1. If the structure reported for strain 142 was conserved in strains JB2 and D1, AvaII-digested genomic DNA of the latter two organisms should have contained one ca. 2.54-kb fragment when they were hybridized with ohbB (Fig. 1). A probe for ohbA should also have detected this fragment, as well as a 2.35-kb fragment (Fig. 1). However, for both strain D1 and strain JB2 hybridization with the ohbB probe resulted in one 4.1-kb fragment and hybridization with the ohbA probe detected this fragment, as well as a 1.4-kb fragment (Fig. 4). These hybridization patterns indicated that the AvaII site which was downstream of tnpA in strain 142 was absent in strains JB2 and D1 and that in the latter strains there was an AvaII site upstream of ohbA that strain 142 lacked. Hybridization analysis also showed that spontaneous mutants of strains JB2 and D1 which had lost the ability to grow on 2-CBa (28) were negative for ohbAB (Fig. 4). Collectively, the PCR, sequence, and hybridization data indicated that ohbAB were highly conserved in strains JB2 and D1 and in strain 142 but that the regions adjoining these genes in the latter organism were different from the regions in strains JB2 and D1. Also, these results, along with those of previous work (28), suggested that ohbAB are linked to clusters of other biodegradation genes (e.g., a salicylate 5-hydroxylase gene) and may be carried by the same mobile element.

FIG. 4.

Detection of ohbA and ohbB homologs by Southern hybridization. (A) Agarose gel containing EcoRI/HindIII-digested λ DNA (lane 1) and AvaII-digested genomic DNA from P. huttiensis D (lane 2), P. huttiensis D1 (lane 3), P. huttiensis D1 deletion mutant 1 (lane 4), P. huttiensis D1deletion mutant 2 (lane 5), P. aeruginosa JB2 (lane 6), P. aeruginosa JB2 deletion mutant 1 (lane 7), and P. aeruginosa JB2 deletion mutant 2 (lane 8). (B to D) Hybridization of the genomic DNA to probes targeting ohbA, ohbB, and hybB, respectively. The lanes contained the DNA described above for panel A.

In strain142, genes encoding the electron transport components of the o-halobenzoate dioxygenase are not clustered with ohbAB (52). Tsoi et al. (52) noted that evolutionarily related homologs of ohbAB, bphA1dA2d and bphA2cA1c from pNL1 (44), also lacked structural association with such genes or were affiliated with only one of the necessary components. These authors postulated that this correspondence might reflect a characteristic pattern of gene assembly in which ohbAB and its homologs have either lost or not established physical linkage with genes encoding electron transport components. Experiments are under way to clone and characterize the regions adjoining ohbAB in strains JB2 and D1, and the results of these studies should allow additional testing of the hypothesized evolutionary segregation of these genes from those of accessory oxygenase components.

Heterologous expression of ohbAB homologs.

E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS carrying pGS2 was tested for activity by using o-chlorobenzoates, including 2-CBa, 2,4-dichlorobenzoate (2,4-diCBa), 2,5-diCBa, 2,3,5-trichlorobenzoate (2,3,5-triCBa), 3-CBa, 4-CBa, and Ba, as substrates. With 2-CBa, a significant decrease in substrate concentration and accumulation of catechol were detected within 1 h, and after 3 h of incubation 2-CBa was quantitatively transformed to catechol (Fig. 5A). There were no significant decreases in the 2-CBa concentrations in the medium blanks or in incubation mixtures with E. coli pET5a. The product of the transformation was identified as catechol on the basis of the following results: its HPLC retention time matched that of a catechol standard, and its gas chromatography retention time and mass spectrum matched those of a catechol standard. Ions with m/z 144 (i.e., chlorocatechols) were not detected in the mass spectrum. Quantitative conversion of 2-CBa to catechol was dependent upon the addition of an adequate amount of pyruvate. When no pyruvate was added, about 20% of the 2-CBa was metabolized within 5 h (data not shown). Addition of 10 mM pyruvate increased the level of 2-CBa transformation to ca. 60% in 5 h, and 40 mM pyruvate resulted in 100% transformation within 5 h. We were concerned that high concentrations of pyruvate could have deleterious effects on the cells but observed no significant differences between the rates or extents of 2-CBa transformation when 10 mM pyruvate was added four times at hourly intervals and the rates or extents of 2-CBa transformation when 40 mM pyruvate was added once initially. Thus, all subsequent tests were performed by using the latter treatment.

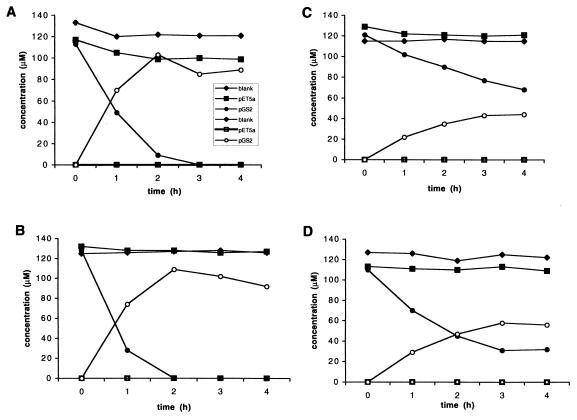

FIG. 5.

Time course of o-halobenzoate transformation to (chloro)catechols by E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS expressing ohbAB in the construct pGS2. Substrate concentrations are also shown for incubations with E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS carrying the vector alone (pET5a) and for medium to which no cells were added (blank). Pyruvate (40 mM) was added to all incubation mixtures. The transformation data shown are data for 2-CBa (A), 2,5-diCBa (B), 2,4-diCBa (C), and 2,3,5-triCBa (D). The explanation of symbols in panel A applies to all four panels. Solid and open symbols indicate concentrations of o-halobenzoates and (chloro)catechols, respectively.

Transformation of 2,5-diCBa was also relatively rapid, and within 2 h the substrate was completely transformed to 4-chlororcatechol (Fig. 5B). Again, there was no significant decrease in substrate concentration in the controls. The metabolite was identified as 4-chlorocatechol as follows: its HPLC retention time matched that of a 4-chlorocatechol standard, and its gas chromatography retention time and mass spectrum matched those of a 4-chlorocatechol standard. Ions with m/z 178 (i.e., dichlorocatechols) were not detected in the mass spectrum. Transformation of 2,4-diCBa to 4-chlorocatechol was detected within 1 h (Fig. 5C). However the 2,4-diCBa transformation rate was only about 30% of the rate measured for 2,5-diCBa, and after 4 h more than one-half of the substrate remained. Transformation of 2,3,5-triCBa occurred at a rate and at an extent that were intermediate between the values obtained for 2-CBa and 2,5-diCBa and the values obtained for 2,4-diCBa (Fig. 5D). The product of this transformation was identified as 3,5-dichlorocatechol as follows: its HPLC retention time matched that of an authentic standard, and its gas chromatography retention time and mass spectrum matched those of an authentic standard. Ions with m/z 212 (i.e., trichlorocatechols) were not detected.

To examine the specificity of OhbABJB2 for o-halobenzoates, Ba, 3-CBa, and 4-CBa were used as substrates. Both Ba and 3-CBa were transformed at similar, relatively low rates that were ca. 30% of the rate of o-halobenzoate transformation (data not shown). There was no detectable transformation of 4-CBa (data not shown).

The two known o-halobenzoate dioxygenases, that of strain 142 and that of strain 2-CBS, represent different lineages with distinct activities (18, 22, 43, 52). The strain 2-CBS enzyme lineage is distinguishable by the effects of halogen electronegativity and chlorine position on transformation of monohalobenzoates and the relative affinity of the enzymes for dihalobenzoates as substrates. The heterologous expression studies reported here addressed the issues of position effect and transformation of dichlorobenzoates. Like the strain 2-CBS and 142 o-halobenzoate dioxygenases, OhbABJB2 was selective for o-chlorobenzoates and catalyzed a regioselective 1,2-dihydroxylation. Consistent with the OhbAB142 lineage, OhbABJB2 had relatively high affinities for dichloro- and trichlorobenzoates. However, OhbABJB2 appeared to differ from OhbAB142 in the effect on activity of a chlorine at the para position. For OhbABJB2, such a chlorine appeared to be an impediment, as shown by the apparent lack of activity with 4-CBa and a rate of transformation of 2,4-diCBa that was much lower than that of 2,5-diCBa or even 2,3,5-triCBa. In contrast, the relative activities of the strain 142 enzyme with 4-CBa, 2,4-diCBa, and 2,5-diCBa as substrates have been reported to be 21, 50, and 38%, respectively, of the activities measured with 2-CBa (43). Side-by-side tests with OhbABJB2 and OhbAB142 and/or site-directed mutagenesis of these enzymes could be used to confirm this difference in substrate affinity and to determine if it is attributable to the slight differences in amino acid sequence that occur in OhbB.

Conclusions.

MALDI-TOF MS is an emerging technique that has an increasing number of applications in microbiology (11, 12, 14, 30, 33, 34, 53). To the best of our knowledge, this study was one of the first studies in which this technique was used for identification of biodegradation enzymes. Our studies so far indicate that ohbAB are located on a mobile element that encodes a variety of biodegradation functions. Furthermore, given that strains JB2 and 142 originated from contaminated soil in southern California and the Moscow region of Russia (42), respectively, the results suggest that ohbAB and/or the mobile element on which these genes are carried may have a global distribution.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by grant R82-7103-01-0 from the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency to W.J.H.

We thank Amy Harms and Jim Brown of the University Wisconsin-Madison Biotechnology Center mass spectrometry facility for expert work in the MALDI-TOF MS analysis. We also thank Santhanam Swaminathan for use of the gel imaging system.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams R H, Huang C-M, Higson F K, Brenner V, Focht D D. Construction of a 3-chlorobiphenyl-utilizing recombinant from an intergeneric mating. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:647–654. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.2.647-654.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Alejandro A S, Schäffer A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul S J, Gish W, Miller W, Meyers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barriault D, Sylvestre M. Factors effecting PCB degradation by an implanted bacterial strain in soil microcosms. Can J Microbiol. 1993;39:594–602. doi: 10.1139/m93-086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batie C J, Ballou D P, Correll C C. Phthalate dioxygenase reductase and related flavin-iron-sulfur containing electron transferases. In: Müller F, editor. Chemistry and biochemistry of flavoenzymes. Vol. 3. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 543–556. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blasco R, Mallavarapu M, Wittich R, Timmis K, Pieper D. Evidence that formation of protoanemonin from metabolites of 4-chlorobiphenyl degradation negatively affects the survival of 4-chlorobiphenyl-cometabolizing microorganisms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:427–434. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.427-434.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blasco R, Wittich R, Mallavarapu M, Timmis K, Pieper D. From xenobiotic to antibiotic, formation of protoanemonin from 4-chlorocatechol by enzymes of the 3-oxoadipate pathway. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29229–29235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butler C S, Mason J R. Structure-function analysis of the bacterial aromatic ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases. Adv Microb Physiol. 1996;38:47–84. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60155-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chong B E, Kim J, Lubman D M, Tiedje J M, Kathariou S. Use of non-porous reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography for protein profiling and isolation of proteins induced by temperature variations for Siberian permafrost bacteria with identification by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry and capillary electrophoresis-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B. 2000;748:167–177. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)00288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conway G C, Smole S C, Sarracino D A, Arbeit R D, Leopold P E. Phyloproteomics: species identification of Enterobacteriaceae using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;3:103–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Gioia D, Fava F, Baldoni F, Marchetti L. Characterization of catechol- and chlorocatechol-degrading activity in the ortho-chlorinated benzoic acid-degrading Pseudomonas sp. CPE2 strain. Res Microbiol. 1998;149:339–348. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(98)80439-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards-Jones V, Claydon M A, Evason D J, Walker J, Fox A J, Gordon D B. Rapid discrimination between methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by intact cell mass spectrometry. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:295–300. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-3-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fava F, Baldoni F, Marchetti L. 2-Chlorobenzoic acid and 2,5-dichlorobenzoic acid metabolism by crude extracts of Pseudomonas sp. CPE2 strain. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1996;22:275–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1996.tb01160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fava F, Bertin L. Use of exogenous specialised bacteria in the biological detoxification of a dump site-polychlorobiphenyl-contaminated soil in slurry phase conditions. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1999;64:240–249. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19990720)64:2<240::aid-bit13>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fetzner S, Müller R, Lingens F. Degradation of 2-chlorobenzoate by Pseudomonas cepacia 2CBS. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler. 1989;370:1173–1182. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1989.370.2.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fetzner S, Müller R, Lingens F. Purification and some properties of 2-halobenzoate 1,2-dioxygenase, a two-component enzyme system from Pseudomonas cepacia 2CBS. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:279–290. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.279-290.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukuda M. Diversity of chloroaromatic oxygenases. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1993;4:339–343. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gharahdaghi F, Weinberg C R, Meagher D A, Imai B S, Mische S M. Mass spectrometric identification of proteins from silver-stained polyacrylamide gel: a method for the removal of silver ions to enhance sensitivity. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:601–605. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19990301)20:3<601::AID-ELPS601>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gribble G W. The natural production of chlorinated compounds. Environ Sci Technol. 1994;28:310–319. doi: 10.1021/es00056a712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haak B, Fetzner S, Lingens F. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of the plasmid-encoded genes for the two-component 2-halobenzoate 1,2-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas cepacia 2CBS. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:667–675. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.3.667-675.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Häggblom M M. Microbial breakdown of halogenated aromatic pesticides and related compounds. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1992;103:29–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hassel K A. The chemistry of pesticides; their metabolism, mode of action, and uses in crop protection. Weinheim, Germany: Verlag Chemie; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hernandez B S, Higson F K, Kondrat R, Focht D D. Metabolism and inhibition by chlorobenzoates in Pseudomonas putida P111. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3361–3366. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.11.3361-3366.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hickey W J, Brenner V, Focht D D. Mineralization of 2-chloro- and 2,5-dichlorobiphenyl by Psuedomonas sp. strain UCR2. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;98:175–180. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90151-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hickey W J, Focht D D. Degradation of mono-, di-, and trihalogenated benzoates by Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain JB2. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:3842–3850. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.12.3842-3850.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hickey W J, Sabat G, Yuroff A S, Arment A R, Pérez-Lesher J. Cloning, nucleotide sequencing, and functional analysis of a novel, mobile cluster of biodegradation genes from Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain JB2. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:4603–4609. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.10.4603-4609.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hickey W J, Serales D, Focht D D. Enhanced mineralization of Aroclor 1242 in soil by inoculation with chlorobenzoate and chlorobiphenyl-degrading bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1194–1200. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.4.1194-1200.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holland R D, Rafii F, Heinze T M, Sutherland J B, Voorhees K J, Lay J O. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometric detection of bacterial biomarker proteins isolated from contaminated water, lettuce and cotton cloth. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2000;14:911–917. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0231(20000530)14:10<911::AID-RCM965>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hrywna Y, Tsoi T V, Maltseva O V, Quensen J F, Tiedje J M. Construction and characterization of two recombinant bacteria that grow on ortho- and para-substituted chlorobiphenyls. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2163–2169. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.5.2163-2169.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larsson T, Bergstrom J, Nilsson C, Karlsson K A. Use of an affinity proteomics approach for the identification of low-abundant bacterial adhesins as applied on the Lewis(b)-binding adhesin of Helicobacter pylori. FEBS Lett. 2000;469:155–158. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01270-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lay J O. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and bacterial taxonomy. Trac-Trends Anal Chem. 2000;19:507–516. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nam J W, Nojiri H, Yoshida T, Habe H, Yamane H, Omori T. New classification system for oxygenase components involved in ring-hydroxylating oxygenations. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2001;65:254–263. doi: 10.1271/bbb.65.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niedan V, Scholer H F. Natural formation of chlorobenzoic acids (CBA) and distinction between PCB-degraded CBA. Chemosphere. 1997;35:1233–1241. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pavlu L, Vosáhlová J, Klierová H, Prouza M, Demnerová K, Brenner V. Characterization of chlorobenzoate degraders isolated from polychlorinated biphenyl-contaminated soil and sediment in the Czech Republic. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;87:381–386. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pérez-Lesher J, Hickey W J. Use of an s-triazine nitrogen source to select for and isolate a recombinant chlorobenzoate-degrading Pseudomonas. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;133:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pieper D H, Reineke W. Engineering bacteria for bioremediation. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2000;11:262–270. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(00)00094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Potrawfke T, Lohnert T H, Timmis K N, Wittich R M. Mineralization of low-chlorinated biphenyls by Burkholderia sp. strain LB400 and by a two membered consortium upon directed interspecies transfer of chlorocatechol pathway genes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;50:440–446. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reineke W. Development of hybrid strains for the mineralization of chloroaromatics by patchwork assembly. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;52:287–331. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Romanov V P, Grechkina G M, Adanin V M, Starovoitov I I. Oxidative dehalogenation of 2-chloro- and 2,4-dichlorobenzoate by a strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mikrobiologiya. 1993;62:887–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Romanov V P, Hausinger R P. Pseudomonas aeruginosa 142 uses a three-component ortho-halobenzoate 1,2-dioxygenase for metabolism of 2,4-dichloro- and 2-chlorobenzoate. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3368–3374. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3368-3374.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Romine M F, Stillwell L C, Wong K K, Thurston S J, Sisk E C, Sensen C, Gaasterland T, Fredrickson J K, Saffer J D. Complete sequence of a 184-kilobase catabolic plasmid from Sphingomonas aromaticivorans F199. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1585–1602. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.5.1585-1602.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schägger H, Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Selifonov S A, Gurst J E, Wackett L P. Regioselective dioxygenation of ortho-trifluoromethylbenzoate by Pseudomonas aeruginosa 142—evidence for 1,2-dioxygenation as a mechanism in ortho-halobenzoate dehalogenation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;213:759–767. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siciliano S D, Germida J J. Bacterial inoculants of forage grasses that enhance degradation of 2-chlorobenzoic acid in soil. Environ Toxicol Chem. 1997;16:1098–1104. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sondossi M, Sylvestre M, Ahmed D. Effects of chlorobenzoate transformation on Pseudomonas testosteroni biphenyl and chlorobiphenyl degradation pathway. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:485–495. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.2.485-495.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stratford J, Wright M A, Reineke W, Mokross H, Havel J, Knowles C J, Robinson G K. Influence of chlorobenzoates on the utilisation of chlorobiphenyls and chlorobenzoate mixtures by chlorobiphenyl/chlorobenzoate-mineralising hybrid bacterial strains. Arch Microbiol. 1996;165:213–218. doi: 10.1007/BF01692864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suzuki K, Ogawa N, Miyashita K. Expression of 2-halobenzoate dioxygenase genes (cbdSABC) involved in the degradation of benzoate and 2-halobenzoate in Burkholderia sp. TH2. Gene. 2001;262:137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00542-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. Clustal-W—improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsoi T V, Plotnikova E G, Cole J R, Guerin W F, Bagdasarian M, Tiedje J M. Cloning, expression, and nucleotide sequence of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa 142 ohb genes coding for oxygenolytic ortho-dehalogenation of halobenzoates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2151–2162. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.5.2151-2162.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Winkler M A, Hickman R K, Golden A, Aboleneen H. Analysis of recombinant protein expression by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry of bacterial colonies. BioTechniques. 2000;28:890–895. doi: 10.2144/00285st01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]