Abstract

A variety of stress situations may affect the activity and survival of plant-beneficial pseudomonads added to soil to control root diseases. This study focused on the roles of the sigma factor AlgU (synonyms, AlgT, RpoE, and ς22) and the anti-sigma factor MucA in stress adaptation of the biocontrol agent Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0. The algU-mucA-mucB gene cluster of strain CHA0 was similar to that of the pathogens Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pseudomonas syringae. Strain CHA0 is naturally nonmucoid, whereas a mucA deletion mutant or algU-overexpressing strains were highly mucoid due to exopolysaccharide overproduction. Mucoidy strictly depended on the global regulator GacA. An algU deletion mutant was significantly more sensitive to osmotic stress than the wild-type CHA0 strain and the mucA mutant were. Expression of an algU′-′lacZ reporter fusion was induced severalfold in the wild type and in the mucA mutant upon exposure to osmotic stress, whereas a lower, noninducible level of expression was observed in the algU mutant. Overexpression of algU did not enhance tolerance towards osmotic stress. AlgU was found to be essential for tolerance of P. fluorescens towards desiccation stress in a sterile vermiculite-sand mixture and in a natural sandy loam soil. The size of the population of the algU mutant declined much more rapidly than the size of the wild-type population at soil water contents below 5%. In contrast to its role in pathogenic pseudomonads, AlgU did not contribute to tolerance of P. fluorescens towards oxidative and heat stress. In conclusion, AlgU is a crucial determinant in the adaptation of P. fluorescens to dry conditions and hyperosmolarity, two major stress factors that limit bacterial survival in the environment.

Some strains of fluorescent pseudomonads colonize the roots of many crop plants and protect them from diseases caused by soilborne fungal pathogens. Disease suppression by these bacteria involves a blend of mechanisms, including effective competition for nutrients and colonization sites, pathogen inhibition by production of antimicrobial compounds, and induction of resistance in the plant (3, 24, 62). Following introduction into soil, the biocontrol performance of pseudomonads depends largely on their ability to maintain stable populations and to be metabolically active at least over the period needed to exert their beneficial effects. However, in soil these bacteria are exposed to a range of variable biotic and abiotic stress factors, such as competition, predation, and changes in temperature, osmolarity, and availability of water and nutrients (42, 63). Therefore, the sizes of introduced pseudomonad populations may decline considerably within a few weeks, and biocontrol activity often tends to be variable (24, 62).

To ensure survival in changing environments, bacteria rely on regulatory mechanisms that allow them to respond rapidly to stress situations (60). Regulatory elements that make essential contributions to bacterial survival under stress conditions include the alternative sigma factors RpoS (ςs) and RpoE (ς22; also referred to as AlgU or AlgT in fluorescent pseudomonads). RpoS is required for tolerance of stationary-phase cultures of different Pseudomonas species towards hyperosmolarity, high temperatures, and agents generating reactive oxygen intermediates (ROIs) (23, 52, 61). AlgU contributes to tolerance towards osmotic, oxidative, and heat stresses in the pathogens Pseudomonas aeruginosa (32, 54, 56, 70) and Pseudomonas syringae (26).

The extracytoplasmic function sigma factor AlgU is encoded by the algU gene, which is part of a highly conserved operon in gram-negative bacteria (19, 26, 35, 44). The function of algU has been extensively studied in P. aeruginosa with respect to its roles in stress response and in regulation of biosynthesis of the exopolysaccharide (EPS) alginate. Regulation of AlgU activity in P. aeruginosa is complex. AlgU positively regulates its own transcription (12, 22, 56, 68). Located downstream of algU, the mucABCD genes ensure tight control of AlgU activity in P. aeruginosa (19). The mucA gene encodes a transmembrane protein which acts as an anti-sigma factor for AlgU, and mucB codes for a periplasmic protein which is another negative regulator of AlgU (36, 57, 69). MucC and MucD modulate algU expression, but the precise functions of these proteins have not been fully established yet (5, 6). Binding of AlgU to the inner membrane protein MucA occurs when MucA interacts with the periplasmic MucB protein (36, 44, 50). Environmental stress conditions are thought to destabilize the MucB-MucA-AlgU complex, leading to release of AlgU into the cytosol. As a consequence, AlgU becomes active and transcription of alginate biosynthesis and other genes occurs. Any change in the balance of this regulatory system influences the titer of available active AlgU. For example, mutations in mucA or mucB cause increased activity of AlgU, which leads to mucoidy due to overproduction of alginate (33, 34, 36). Mucoid conversion due to spontaneous lesions in mucA is typically detected in P. aeruginosa isolates from chronically infected cystic fibrosis patients, and the production of copious amounts of alginate is thought to be important for virulence and survival of these bacteria in the lungs (4, 34).

Little is known about the role of AlgU and its negative regulators in plant-beneficial pseudomonads. In the present study, we identified a genomic region which comprises the algU-mucA-mucB gene cluster in Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0, a well-characterized soil bacterium with broad-spectrum biocontrol activity (24, 65). We found that AlgU, along with MucA, tightly controls EPS biosynthesis and tolerance towards osmotic stress in this bacterium. In contrast to AlgU of pathogenic pseudomonads, AlgU of strain CHA0 does not contribute to survival in response to treatment with heat and ROIs. Finally, we present the first evidence that AlgU is a crucial determinant in adaptation of P. fluorescens to desiccation stress, a major factor that limits bacterial survival in formulations or in soil.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. P. fluorescens strains were cultivated on nutrient agar (NA) (59), on King's medium B (KMB) agar (27), in nutrient yeast broth (NYB) (59), in KMB broth, and in Luria-Bertani broth (LB) (51) at 30°C with aeration. Escherichia coli and P. aeruginosa strains were grown on NA and in NYB at 37°C. Antimicrobial compounds, when required, were added to the growth media at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 25 μg/ml; HgCl2, 20 μg/ml; gentamicin, 10 μg/ml; kanamycin sulfate, 25 μg/ml; rifampin, 100 μg/ml; and tetracycline hydrochloride, 25 μg/ml for E. coli and 125 μg/ml for P. fluorescens strains. When appropriate, 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactoside (X-Gal) was incorporated into solid media to monitor β-galactosidase expression (51).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype and/or phenotypea | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| P. fluorescens strains | ||

| CHA0 | Wild type | 65 |

| CHA0-Rif | Spontaneous Rifr derivative of CHA0 | 45 |

| CHA89 | gacA::Ω-Km, Kmr | 29 |

| CHA211 | mucA::Tn5, Kmr | This study |

| CHA212 | ΔalgU | This study |

| CHA212-Rif | CHA0-Rif ΔalgU, Rifr | This study |

| CHA213M | ΔmucA | This study |

| CHA213M.gacA | ΔmucA gacA::Ω-Km, Kmr | This study |

| CHA510 | gacS::Tn5, Kmr | 8 |

| P. aeruginosa strains | ||

| PAO1 | Wild type | ATCC 15692 |

| PAO568 | mucA2 leu-38 str-2 FP2+ | 32 |

| PAO6852 | PAO1 algU::Tcr, Tcr | 32 |

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | recA1 endA1 hsdR17 deoR thi-1 supE44 gyrA96 relA1 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 (ϕ80dlacZΔM15) | 51 |

| W3110 | Prototroph, sup0 λ− | 51 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript II KS+ | Cloning vector, ColE1 replicon, Apr | Stratagene |

| pLG221 | Suicide vector, Coll1drd-1::Tn5, IncIα, Kmr | 7 |

| pME497 | Mobilizing plasmid, IncP-1, Tra RepA(Ts), Apr | 66 |

| pME3049 | Suicide vector, ColE1 replicon, RK2-Mob, Hgr Kmr | 53 |

| pME3087 | Suicide vector, ColE1 replicon, RK2-Mob, Tcr | 65 |

| pME3088 | Suicide vector, ColE1 replicon, RK2-Mob, Tcr | 65 |

| pME3089Km | pME3088 carrying gacA of P. fluorescens disrupted by an Ω-Km cassette, Tcr Kmr | 29 |

| pME6000 | Cloning vector, pBBR1MCS derivative, 18 copies per chromosome equivalent in P. fluorescens, Tcr | 38 |

| pME6010 | Cloning vector, pACYC177-pVS1 shuttle vector, 6 copies per chromosome equivalent in P. fluorescens, Tcr | 21 |

| pME6010ΔB | pME6010 with deletion of the unique BamHI site, Tcr | This study |

| pME6200B | pME3049 with a 0.8-kb genomic DNA fragment of P. fluorescens CHA211 | This studyb |

| pME6200X | pME3049 with a 4.5-kb genomic DNA fragment of P. fluorescens CHA211 | This studyb |

| pME6202X | pME3049 with a 14.5-kb genomic DNA fragment of P. fluorescens CHA0 | This studyb |

| pME6202XΔEV | pME6202X with a 9.8-kb EcoRV deletion | This studyb |

| pME6217 | pME6000 with a 2.6-kb ApaI-BamHI fragment of pME6202XΔEV, containing algUmucA | This studyb |

| pME6219 | pME6010ΔB with a 2.6-kb ApaI-BamHI fragment of pME6202XΔEV in which the 275-bp NotI-ClaI fragment in algU is replaced by the 56-bp NotI-ClaI polylinker of pBluescript II KS+, contains intact mucA | This studyb |

| pME6220 | pME6000 with a 1.7-kb ApaI-MscI fragment of pME6202XΔEV, containing algU | This studyb |

| pME6221 | pME6010ΔB with a 1.7-kb ApaI-MscI fragment of pME6202XΔEV, containing algU | This studyb |

| pME6222 | pME6010ΔB with a 1.0-kb ApaI-NotI fragment of pME6202XΔEV and the 3-kb BamHI-DraI fragment of pNM482 containing ′lacZ, algU′-′lacZ translational fusion at the NotI site in algU | This studyb |

| pME6551 | Cloning vector, pME6000 derivative with insertion of the Gmr determinant (aac1 gene) of pML8 at the EcoRV site in the tetA gene, Tcs Gmr | This study |

| pME6555 | pME6551 with a 1,712-bp Sau3A fragment of pME6215 (5′ end located 48 bp upstream of the algU start codon) containing algUmucA placed under the control of the lac promoter | This studyb |

| pML8 | RSF1010-derived cloning vector carrying the Gmr gene aac1, Tcr Gmr | 28 |

| pNM482 | ColE1 replicon, ′lacZ, Apr | 43 |

| pUK21 | Cloning vector, lacZα, Kmr | 64 |

Apr, ampicillin resistance; Gmr, gentamicin resistance; Hgr, mercury resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance; Rifr, rifampin resistance; Tcr, tetracycline resistance.

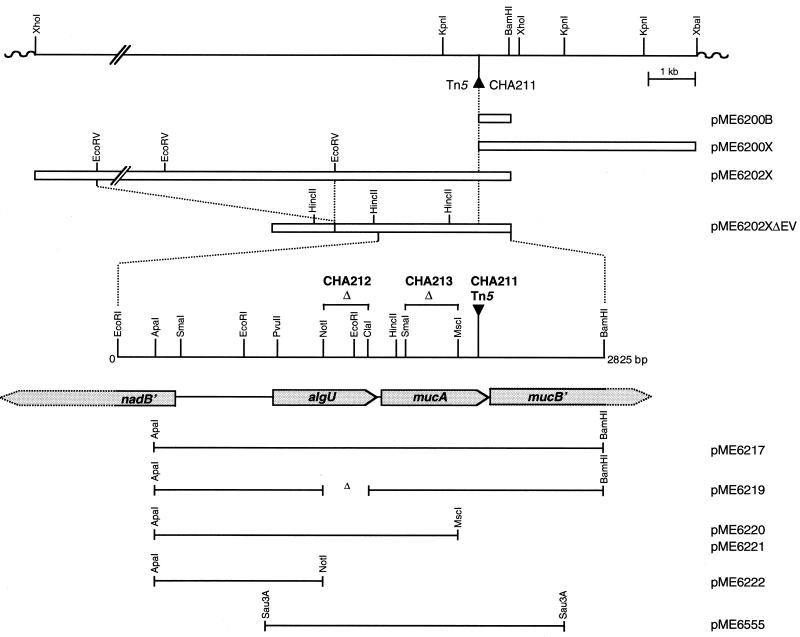

See Fig. 1.

DNA manipulation and sequencing.

Small-scale plasmid DNA preparations were obtained from P. fluorescens strains and pME3049-, pME3087-, and pME3088-based plasmids were isolated from E. coli by the alkaline lysis method (51). All other plasmids were prepared from E. coli by the method of Del Sal et al. (10). Qiagen-tip 100 columns (Qiagen Inc.) were used for large-scale plasmid DNA preparation. Chromosomal DNA of P. fluorescens was isolated as described by Schnider et al. (53). Standard techniques were used for restriction, agarose gel electrophoresis, dephosphorylation, generation of blunt ends with the Klenow fragment of E. coli DNA polymerase I or T4 DNA polymerase (Roche), isolation of DNA fragments from low-melting-point agarose gels, and ligation (51). Restriction fragments were purified from agarose gels with a Geneclean II kit (Bio 101). Bacterial cells were transformed with plasmid DNA by CaCl2 treatment (51) or electroporation (15). Southern blotting with Hybond N membranes (Amersham), random-primed DNA labeling with digoxigenin-11-dUTP, hybridization, and detection (Roche) were performed by using the protocols of the suppliers. Subclones of pME6202XΔEV (Table 1; Fig. 1) constructed in pBluescript II KS+ were used for nucleotide sequence determination. Both strands of the 2,825-bp EcoRI-BamHI fragment of pME6202XΔEV were sequenced by the dideoxy chain termination method using a Sequenase 2.0 kit (United States Biochemical, Cleveland, Ohio) and T7 polymerase from Pharmacia. Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences were analyzed with programs of the University of Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group package (version 9.1).

FIG. 1.

Physical location of the nadB, algU, mucA, and mucB genes in P. fluorescens CHA0. Symbols: ▾, Tn5 insertion in the chromosome of strain CHA211; ▵, region deleted in strains CHA212 and CHA213M and in plasmid pME6219. The shaded arrows indicate the genes sequenced or partly sequenced on the EcoRI-BamHI fragment of pME6202XΔEV. The open boxes indicate the genomic inserts in ColE1-based plasmids pME6200B, pME6200X, pME6202X, and pME6202XΔEV. The lines indicate the fragments cloned into vector pME6000 to obtain pME6217, pME6220, and pME6555 and into vector pME6010ΔB to obtain pME6219, pME6221, and pME6222.

Plasmid mobilization and transposition.

Derivatives of the suicide plasmids pME3049, pME3087, and pME3088 were mobilized from E. coli to P. fluorescens with helper plasmid pME497 in triparental matings as described by Schnider et al. (53). Transposon mutagenesis in which E. coli W3110 containing Tn5 suicide plasmid pLG221 (7) was used as the donor strain and P. fluorescens CHA0 was used as the recipient strain was carried out as described previously (37).

Construction of P. fluorescens mutants by gene replacement.

For construction of the algU in-frame mutant CHA212 (Fig. 1), the 275-bp NotI-ClaI fragment in algU was replaced by the 56-bp NotI-ClaI polylinker from pBluescript II KS+. The flanking genomic DNA, consisting of the 1.2-kb HincII-NotI fragment and the 1.4-kb ClaI-BamHI fragment of pME6202XΔEV (Fig. 1), was cloned into suicide vector pME3087 (65). To obtain the mucA in-frame mutant CHA213M (Fig. 1), the 309-bp SmaI-McsI fragment in mucA was deleted. The flanking genomic DNA, consisting of the 0.6-kb PvuII-SmaI fragment and the 0.8-kb McsI-BamHI fragment of pME6202XΔEV, was cloned into suicide vector pME3088 (65). The derivatives of the suicide plasmids, which carried a tetracycline resistance determinant, were mobilized with helper plasmid pME497 (66) to wild-type strain CHA0. Cells with a chromosomally integrated plasmid were selected for tetracycline resistance. Excision of the vector by a second homologous recombination event was observed after enrichment for tetracycline-sensitive cells (53). The same approach was used to create an algU in-frame mutation in rifampin-resistant strain CHA0-Rif. To obtain the mucA gacA double mutant CHA213M.gacA, plasmid pME3089Km, a derivative of suicide vector pME3088 carrying gacA disrupted by an Ω-Km cassette (29), was mobilized into strain CHA213M. Selection of cells with a chromosomally integrated plasmid and excision of the vector by a second crossover were performed as described above. Selection for kanamycin resistance ensured the presence of the Ω-Km insertion in strain CHA213M.gacA. The algU, mucA, and gacA mutations were checked by Southern blotting (data not shown).

Extraction and quantification of EPS from P. fluorescens.

Aliquots (100 μl) of an overnight LB culture of strain CHA0 or one of its derivatives were plated on KMB agar plates. Three replicate plates per strain were prepared and incubated for 24 h at 30°C. Extraction and quantification of EPS were performed by using a procedure described by May and Chakrabarty (39). Briefly, cells were removed from the medium and suspended in 0.9% NaCl. The suspensions were centrifuged for 30 min at 17,700 × g and 4°C to separate the cells from the EPS. The cell pellets were kept for determinations of total cell protein contents. The EPS was repeatedly precipitated and washed with ice-cold absolute ethanol. The contents of uronic acid polymers (components of alginate) in the samples were then assessed by performing the colorimetric carbazole assay (39), using d-mannurolactone (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) and alginic acid from seaweed (Macrocystis pyrifera; Sigma) as the standards. The uronic acid content was expressed per milligram of total cell protein as determined by the Lowry method, using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Purification and biochemical analysis of EPS.

Mucoid layers from five KMB agar cultures of highly mucoid mutant strains CHA211 and CHA213M, cultivated under the conditions described above, were scraped off the plates with a sterilized spatula, pooled, and suspended in 50 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.2). After vigorous stirring at 4°C for 1 h, the viscous solution was centrifuged at 17,700 × g and 4°C for 4 h to remove the bacterial cells. The remaining proteins in the supernatant were denatured by heating at 80°C for 30 min and removed by centrifugation at 17,700 × g for 30 min. Precipitation of EPS by the addition of ice-cold absolute ethanol, washing, and removal of nucleic acids by digestion with DNase I (type IV; Sigma) and RNase A (type 1A; Sigma) were performed as described by Pedersen et al. (47). The EPS was then further purified by ion-exchange chromatography. Samples were dissolved in 25 mM ammonium carbonate, loaded onto a DEAE-Sepharose CL-6B column (1.6 by 20 cm; bed volume, 40 ml; Pharmacia), which had been equilibrated with the same buffer, and eluted with a linear 25 mM to 1 M ammonium carbonate gradient (39, 47). Fractions (5 ml) containing uronic acids were pooled, extensively dialyzed against sterile water, and lyophilized.

The total carbohydrate of the purified EPS was quantified colorimetrically by performing the phenol-sulfuric acid assay (13) with 3% (wt/vol) phenol, using d-mannuronic acid lactone (Sigma) and seaweed alginate as the standards. The degree of acetylation of uronic acids was assessed on the basis of a colorimetric reaction with hydroxylamine hydrochloride (40), using β-d-glucose-pentaacetate (Sigma) as the standard.

Effect of osmotic stress on algU′-′lacZ expression and growth.

P. fluorescens CHA0 and its mutant derivatives carrying an algU′-′lacZ translational fusion on plasmid pME6222 (Table 1; Fig. 1) were grown in 20 ml of KMB without selective antibiotics in 100-ml Erlenmeyer flasks plugged with cotton. Plasmid pME6222 carries the algU promoter region and the 5′ end of algU fused to ′lacZ from pMN482 (43). To induce osmotic stress, KMB was supplemented with NaCl (0.6, 0.8, 1.0, or 1.2 M) or sorbitol (1.2 or 1.6 M), a nonionic solute which cannot be metabolized by strain CHA0. For inoculation, aliquots of exponential-growth-phase LB cultures of the bacterial strains were used to adjust the cell concentrations to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.05. Cultures were incubated with rotational shaking (180 rpm) at 30°C. β-Galactosidase specific activities of at least three independent cultures were monitored by the Miller method (51).

Doubling times of strain CHA0 and its derivatives (cultivated as described above) were calculated from OD600 values between 0.05 and 1.5 (i.e., during exponential growth). After 24 h of incubation, bacterial survival was assessed by plating serial dilutions of the cultures on NA and determining the ratio of CFU from osmotically stressed cultures to CFU from nonstressed cultures.

Desiccation survival assay performed with filter disks.

The sensitivity of P. fluorescens to desiccation on filters was assessed by using a modification of the procedure described by Ophir and Gutnick (46). Dilutions of overnight bacterial cultures were vacuum filtered onto Millipore filters (no. HAWP04700; pore size, 0.45 μm; diameter, 3.5 cm) in order to obtain about 10 to 20 physically separated bacterial cells per filter. The filters were placed onto KMB agar plates and incubated at 30°C for 24 h, which yielded about 5 × 107 CFU per colony that had developed from the individual bacterial cells. Bacterial colonies were then slowly dried by removing the filters from the agar plates, cutting the filters into small pieces so that each piece contained a single bacterial colony, and incubating the pieces in empty petri dishes at 30°C for 24 h. Colonies on filter pieces that were placed on agar medium lacking nutrients (18 g of Serva agar per liter, 1.15 g of K2HPO4 per liter, 1.5 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O per liter) and were incubated for the same period served as controls. Cells from a single colony on each filter were then suspended in 1 ml of a 0.85% NaCl solution by vigorous mixing with a Vortex mixer for 15 min, and serial dilutions were plated on NA to determine the number of CFU per colony. Washed filter pieces incubated on NA plates showed that almost all cells were removed by this treatment. The level of survival was calculated by determining the percentage of the number of CFU in desiccated colonies relative to the number of CFU in control colonies. Each filter piece was handled separately, and the numbers of CFU were determined for at least five colonies per treatment. The experiment was repeated three times.

Desiccation survival assay performed with soil microcosms.

Survival of bacterial strains was monitored in desiccating, sterile, artificial soil and in desiccating, nonsterile, natural soil. The artificial soil consisted of pure vermiculite (expanded with 30% H2O2), quartz sand with different sizes of particles, and quartz powder mixed at a ratio of 10:70:20 (by weight) and moistened with 10% (wt/wt) distilled water (25). The artificial soil was autoclaved twice prior to bacterial inoculation. Natural sandy loam soil was collected from the surface horizon of a Swiss cambisol located at Eschikon near Zurich (45). The soil was sieved through a 5-mm mesh screen prior to use, and stones and roots were removed. The bacterial cell suspensions used in microcosms were prepared from exponential-growth-phase cultures grown in LB at 24°C for 16 h. The cells were washed twice in sterile distilled water, and the cell concentration was adjusted to an OD600 of 0.2. For inoculation of the artificial or natural soil, 67 ml of the bacterial suspension was thoroughly mixed into 1,000 g of soil with a sterilized spoon to obtain about 107 CFU per g of soil. For natural soil microcosms, rifampin-resistant derivatives of the bacterial strains were used as the inoculants. Aliquots (20 g) of inoculated soil were placed into sterile 200-ml Erlenmeyer flasks with wide openings. The openings were covered with one layer of sterilized paper cloth, which allowed slow evaporation of the soil water. Control microcosms kept at a constant soil moisture level were prepared by placing 200-g portions of sterile, artificial soil or nonsterile, natural soil containing the bacterial inoculum into 500-ml bottles, which then were sealed hermetically. The initial water content of the artificial soil after addition of bacteria was 15.2% ± 0.2%, which corresponded to a soil water potential (ΨW) of about −0.01 MPa. Natural soil contained 26.9% ± 0.2% water, which corresponded to a ΨW of about −0.02 MPa. The soil microcosms were incubated in the dark at 24°C with 65% relative humidity. For sampling and enumeration of the bacterial inoculants, the entire contents of a flask with desiccated soil or a 5-g sample from a control soil kept at a constant humidity was suspended in sterile distilled water by vigorous agitation on a shaker at 260 rpm for 20 min. At each time point, the number of cultivable cells and the soil water content were determined for three replicate flasks or soil samples per treatment. The numbers of CFU were determined by plating serial dilutions of the soil suspensions on NA. Rifampin-resistant derivatives were recovered from natural soil by plating samples on NA containing 100 μg of rifampin per ml. No rifampin-resistant background bacterial population was present in the natural soil. CFU data were expressed per gram (dry weight) of soil and were log10 transformed before means and standard deviations were calculated. Water content was assessed by oven drying soil samples at 105°C to constant weight. The ψW of soil was determined by using a filter paper method described by McInnes et al. (41).

Susceptibility to oxidative stress.

Sensitivity to paraquat (1,1′-dimethyl-4,4′-bipyridinium dichloride; Sigma), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), or sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) was examined as described by Martin et al. (32). Filter disks (diameter, 6 mm; Millipore) were soaked with 10 μl of paraquat (1.9 or 3.8%, wt/vol), H2O2 (3 or 12%, vol/vol), or NaOCl (5 or 10%, vol/vol) and placed on a layer of soft agar (2 ml of NYB with 0.8% agar) containing 100 μl of a P. fluorescens or P. aeruginosa overnight culture covering NA. In another approach, disks (diameter, 10 mm) were soaked with 50-μl portions of the agents mentioned above. The diameters of the inhibition zones surrounding the impregnated disks were measured after overnight incubation at 30°C for P. fluorescens strains and at 37°C for P. aeruginosa strains.

Sensitivity to high temperatures.

P. fluorescens CHA0 and mutant derivatives of this strain were grown at 30°C in 20 ml of KMB or NYB in 100-ml Erlenmeyer flasks sealed with cellulose stoppers. When the cultures reached an OD600 of 0.5, the flasks were transferred to a water bath and incubated for 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 60, and 90 min at 42 or 48°C with rotational shaking at 180 rpm. At each time point, three replicate cultures were sampled to determine the number of CFU on NA. CFU were counted after incubation for 24 and 72 h at room temperature. Levels of survival were expressed as percentages of the input number of CFU at time zero.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the nadB′, algU, mucA, and mucB′ genes of P. fluorescens CHA0 has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. AF399758.

RESULTS

Isolation and characterization of mucoid mutant CHA211.

Following Tn5 mutagenesis of P. fluorescens strain CHA0, 1 of the 1,000 mutants tested had a highly mucoid colony phenotype when it was grown on KMB or NA. In contrast, wild-type strain CHA0 is naturally nonmucoid. The mucoid phenotype of the mutant strain, CHA211, was stable, even when the strain was repeatedly subcultured in nonselective media for more than 1 week. Southern hybridization confirmed that mutant CHA211 contained a single Tn5 insertion (data not shown). The Tn5 insertion was located 550 bp downstream of the initiation codon of the mucA gene (Fig. 1 and see below).

Cloning and sequence analysis of the genes surrounding the Tn5 insertion in strain CHA211.

To localize the genomic region mediating mucoidy in strain CHA211, a two-step Tn5-directed cloning strategy (53) was used to clone the wild-type genes corresponding to the genes that were inactivated by the Tn5 insertion in the mutant. Suicide vector pME3049 carrying the kanamycin resistance determinant of Tn5 was mobilized into strain CHA211. Integration of pME3049 into the chromosome occurred at a frequency of 7.2 × 10−7 per donor. Chromosomal DNA of CHA211::pME3049 was digested with BamHI or XbaI, ligated, and used to transform E. coli DH5α. The resulting plasmids, pME6200B and pME6200X, carried 0.8- and 4.5-kb genomic DNA inserts, respectively, downstream of the Tn5 insertion site (Fig. 1). For isolation of the wild-type genes, plasmid pME6200B was transferred into wild-type strain CHA0. Digestion of genomic DNA of CHA0::pME6200B with XhoI, self-ligation, and transformation of E. coli resulted in plasmid pME6202X (Fig. 1) carrying a 14.6-kb genomic fragment. To reduce the size of the insert in pME6202X, the plasmid was digested with EcoRV and ligated. The plasmid obtained, pME6202XΔEV (Fig. 1), contained a 4.7-kb genomic DNA fragment.

The 2,825-bp nucleotide sequence of the EcoRI-BamHI genomic fragment in pME6202XΔEV (Fig. 1, expanded region) revealed that there were two complete and two partial open reading frames, designated nadB′, algU, mucA, and mucB′, by analogy with homologous genes in P. aeruginosa (12, 31, 33), P. syringae pv. syringae (26), and Azotobacter vinelandii (35). The proposed start codons of nadB′, algU, mucA, and mucB′of P. fluorescens CHA0 are preceded by plausible ribosome-binding sites. The deduced product (193 amino acids, 22.2 kDa) of the algU gene of P. fluorescens CHA0 is very similar to alternative sigma factor AlgU (ς22) of P. syringae pv. syringae (accession no. AF190580; 97% identity), A. vinelandii (accession no. U22895; 93% identity), and P. aeruginosa (accession no. L04794 and L36379; 91% identity) and is also related to RpoE of E. coli (accession no. EC37089; 63% identity). The mucA gene is located downstream of algU, and its product (195 amino acids, 20.9 kDa) is 82, 74, and 63% identical to the MucA anti-ς22 factor of P. syringae pv. syringae (accession no. AF190580), P. aeruginosa (accession no. L14760 and L36379), and A. vinelandii (accession no. U22660), respectively. The product of the adjacent, incompletely sequenced mucB gene is 66, 61, and 65% identical to MucB (AlgN) of P. syringae pv. syringae (accession no. AF190580), P. aeruginosa (accession no. L14760), and A. vinelandii (accession no. U22660), respectively. The intergenic region upstream of algU of P. fluorescens comprises 558 nucleotides and exhibits only 48% nucleotide identity with the corresponding region of P. aeruginosa. Two putative AlgU (RpoE) recognition sites were found 60 bp (GAACTT-16 nucleotides-TCTAT) and 253 bp (GAACTT-17 nucleotides-TCAAT) upstream of the translational start site of algU. Remarkably, the location and sequence of the first AlgU recognition site (60 bp upstream of the initiation codon of algU) are conserved in P. fluorescens, P. syringae pv. syringae (26), and P. aeruginosa (56). The location and sequence of the second AlgU recognition site are almost identical in P. fluorescens and P. syringae pv. syringae. The divergently oriented nadB′ gene upstream of algU was sequenced only in its 5′ region. The deduced product (117 amino acids) exhibits similarities to N termini of the l-aspartate oxidase for NAD biosynthesis of P. aeruginosa (accession no. U17232; 82% identity) and E. coli (accession no. X12714; 56% identity). Based on these sequence comparisons, it appears that the arrangement of the nadB, algU, mucA, and mucB genes is conserved in P. fluorescens, P. syringae, P. aeruginosa, and A. vinelandii.

EPS production in P. fluorescens is controlled by the AlgU regulon.

Chromosomal algU and mucA in-frame deletion mutations were created in strain CHA0 (Fig. 1) as described in Materials and Methods, and the mutants were tested for EPS production by using the carbazole assay for uronic acids. The nonmucoid strains CHA0 (wild type) and CHA212 (algU mutant) produced very low levels of EPS after incubation on KMB agar for 24 h (Table 2). In contrast, mucA in-frame deletion mutant CHA213M developed a mucoid phenotype on KMB agar and produced copious amounts of EPS (Table 2). The mucA::Tn5 mutant CHA211 (Fig. 1) produced even more mucoid material than the mucA in-frame deletion mutant CH213M produced (Table 2). This may have been due to a polar effect of the Tn5 insertion on other AlgU regulatory genes downstream of mucA, especially mucB (36, 50). The level of EPS production in mucoid mutant CHA213M could be restored to the low wild-type level by complementation with mucA+ plasmid pME6219 (Fig. 1), whereas introduction of the cloning vector pME6010ΔB alone had no effect (Table 2). Complementation of the ΔalgU mutation in CHA212 by pME6221 carrying intact algU+ (Fig. 1) did not significantly affect the nonmucoid phenotype of the strain (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

EPS production by P. fluorescens CHA0 and derivatives of this strain

| Straina | Genotype | Phenotype | EPS production (μg/mg of protein)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHA0 | Wild type | Nonmucoid | 42 d |

| CHA0/pME6000 | Wild type/−c | Nonmucoid | 54 d |

| CHA0/pME6220 | Wild type/Palg-algU+ | Mucoid | 4,602 c |

| CHA0/pME6217 | Wild type/Palg-algU+mucA+ | Mucoid | 6,365 c |

| CHA0/pME6555 | Wild type/Plac-algU+mucA+ | Mucoid | 14,802 b |

| CHA212 | ΔalgU | Nonmucoid | 77 d |

| CHA212/pME6010ΔB | ΔalgU/− | Nonmucoid | 70 d |

| CHA212/pME6221 | ΔalgU/algU+ | Nonmucoid | 21 d |

| CHA211 | mucA::Tn5 | Mucoid | 28,143 a |

| CHA213M | ΔmucA | Mucoid | 4,123 c |

| CHA213M/pME6010ΔB | ΔmucA/− | Mucoid | 4,464 c |

| CHA213M/pME6219 | ΔmucA/mucA+ | Nonmucoid | 61 d |

| CHA213M.89 | ΔmucA gacA::Ω-Km | Nonmucoid | 54 d |

| CHA89 | gacA::Ω-Km | Nonmucoid | 43 d |

Bacteria were grown on KMB agar plates at 30°C for 24 h. Plasmid pME6221 was derived from the low-copy-number vector pME6010 (six copies per chromosome equivalent) (21); plasmids pME6217, pME6220, and pME6555 were derivatives of the multiple-copy-number vector pME6000 (18 copies per chromosome equivalent) (38). Palg and Plac indicate control from the natural promoter and the lac promoter, respectively.

EPS production was measured in micrograms of uronic acid produced per milligram of total cell protein. The data are means based on three individually assessed cultures. Values followed by different letters are significantly different at P = 0.05 (Student's t test).

−, empty vector.

When AlgU was overexpressed from multicopy plasmids pME6220 (algU+) and pME6217 (algU+mucA+) (Table 1; Fig. 1) in strain CHA0, the level of EPS production increased to the level observed in mucA mutant CHA213M (Table 2). Interestingly, the presence of multiple copies of mucA in CHA0 carrying pME6217 did not interfere with the EPS-stimulating effect of the algU amplification (Table 2), perhaps because other regulators, such as MucB, were not present at titers that were high enough. Constitutively high levels of expression of algU and mucA from the lac promoter on plasmid pME6555 (Table 1; Fig. 1) in strain CHA0 resulted in further increases in the level of EPS production to levels that were about 3.5 times greater than the level in mucA mutant CHA213M (Table 2). Attempts to clone algU alone under the control of the lac promoter failed, since E. coli and P. fluorescens transformants carrying plasmid constructs with such an insert were not viable and did not maintain the plasmid, respectively (unpublished data). Similar problems have been reported for attempts to overexpress algU in P. aeruginosa and were attributed to potential toxicity of AlgU in the absence of its negative regulators, MucA and MucB (22, 55). In conclusion, EPS biosynthesis in strain CHA0 is controlled by a fine-tuned balance between AlgU and MucA, probably assisted by MucB.

Biochemical analysis of EPS from mucoid mutants of P. fluorescens.

EPS was extracted and purified from mucoid material of KMB agar cultures of mucA mutants CHA211 and CHA213M by using the procedure described by Pedersen et al. (47). During DEAE-Sepharose ion-exchange chromatography, EPS of both P. fluorescens mutants, like alginate of P. aeruginosa (47), eluted between 0.4 and 0.7 M ammonium carbonate, with a maximum peak at 0.53 M ammonium carbonate. The P. fluorescens EPS preparations had total carbohydrate contents of 62% ± 9% and 87% ± 12% (on a dry weight basis) when seaweed alginate and d-mannuronic acid lactone, respectively, were used as the standards. When either of these standards was used, 46% ± 5% of the dry weight could be attributed to uronic acids, a value which is lower than the uronic acid content (70 to 100%) described for P. aeruginosa alginate (47). Nevertheless, the degree of acetylation of P. fluorescens uronic acids determined by a colorimetric assay was 16% ± 2%, a value identical to the value obtained for P. aeruginosa (47). Acetylation of uronic acid polymers is a typical feature of bacterial alginates, whereas algal alginates are not acetylated (18). No contaminating proteins or nucleic acids were detected in purified EPS from P. fluorescens. These results indicate that mucoidy in mucA mutants of P. fluorescens CHA0 is due to overproduction of an acetylated EPS which may be related to some extent to the EPS produced by P. aeruginosa. Fluorescent pseudomonads have been shown to produce a wide variety of EPS which may differ considerably in composition, and alginate has been detected in only some of these EPS (16, 17).

Kinetics of algU expression in response to osmotic stress.

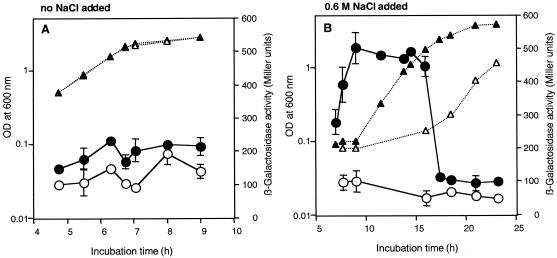

To test algU regulation in response to osmotic stress, we monitored expression of an algU′-′lacZ reporter fusion carried by pME6222 (Table 1; Fig. 1) in wild-type strain CHA0 and mutant derivatives of this strain in the presence of NaCl and the nonionic solute sorbitol. In KMB without NaCl, algU was expressed at low, almost constant levels in strain CHA0 and in algU mutant CHA212 (Fig. 2A). Upon exposure to 0.6 M NaCl, algU expression in wild-type cells was transiently induced about two- to threefold in the early exponential growth phase, whereas no induction occurred in the algU mutant (Fig. 2B). Similar results were obtained when an osmotically equivalent concentration of sorbitol (1.2 M) was added to the growth medium (Table 3). Overexpression of algU from pME6555 or the lack of mucA in strain CHA213M led to expression of the algU′-′lacZ reporter that was significantly greater than the expression in the wild type in the nonsupplemented medium (Table 3). Expression of algU′-′lacZ was further enhanced by exposure to osmotic stress (Table 3). In summary, algU expression in P. fluorescens is induced in response to osmotic stress, and moreover, as in P. aeruginosa (12, 22, 56, 69), AlgU in P. fluorescens positively regulates its own expression.

FIG. 2.

Kinetics of expression of an algU′-′lacZ fusion in response to NaCl stress. β-Galactosidase activity was assayed in P. fluorescens CHA0 (●) and ΔalgU mutant CHA212 (○), both carrying pME6222. Growth of CHA0 (▴) and growth of CHA212 (▵) were determined by measuring OD600. Strains were grown at 30°C in KMB without (A) or with (B) 0.6 M NaCl. The data are means ± standard deviations based on three experiments. Some of the error bars were too small to be included.

TABLE 3.

Expression of an algU′-′lacZ fusion in P. fluorescens CHA0 and mutant derivatives of strain CHA0 in response to osmotic stress

| Straina | Genotype | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units)b

|

Induction factorc

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without stress | 0.6 M NaCl | 1.2 M Sorbitol | NaCl | Sorbitol | ||

| CHA0 | Wild type | 174 b | 448 b | 469 b | 2.6 | 2.7 |

| CHA212 | ΔalgU | 104 c | 77 c | 124 b | 0.7 | 1.2 |

| CHA0/pME6555 | Plac-algU+mucA+ | 275 a | 683 a | 657 a | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| CHA213M | ΔmucA | 268 a | 694 a | ND | 2.6 | ND |

| CHA89 | gacA::Ω-Km | 147 b | 381 b | ND | 2.6 | ND |

| CHA510 | gacS::Tn5 | 151 b | 379 b | ND | 2.5 | ND |

All bacterial strains carried the reporter construct pME6222 containing an algU‘-’lacZ fusion.

The initial bacterial cell concentration was adjusted to an OD600 of 0.05, and cells were grown for 12 h at 30°C in KMB broth with no supplement or amended with 0.6 M NaCl or 1.2 M sorbitol. The data are means based on three experiments, and three replicate cultures were used for each experiment. Values in the same column followed by different letters are significantly different at P = 0.05 (Student's t test). ND, not determined.

Expression of algU′-′lacZ in a bacterial strain grown in the presence of a stress relative to expression of the reporter construct in the absence of the stress.

In P. fluorescens CHA0 a conserved two-component regulatory system consisting of the sensor kinase GacS and the cognate response regulator GacA globally controls the biosynthesis of a range of extracellular products, including antimicrobial compounds and exoenzymes (20, 29). EPS is another exoproduct of strain CHA0 controlled by the GacS-GacA system, as disruption of the gacA gene in mucoid mucA mutant CHA213M.gacA made the strain nonmucoid and reduced the levels of EPS production to the levels in the wild type or gacA mutant CHA89 (Table 2). GacS-GacA also regulates alginate production in P. syringae (67), Pseudomonas viridiflava (30), and A. vinelandii (9). In P. fluorescens, algU expression in gacA or gacS mutants was not significantly different from algU expression in the wild type in the absence or presence of osmotic stress (Table 3), indicating that GacS-GacA control of EPS production is not exerted via the sigma factor AlgU.

AlgU is required for tolerance of P. fluorescens towards osmotic stress.

We next tested how different levels of algU expression affect growth and survival of P. fluorescens in response to osmotic stress. To do this, the doubling times of strain CHA0 and mutant derivatives of this strain were determined during exponential growth of the bacteria in KMB supplemented with different concentrations of NaCl or sorbitol. The algU mutant CHA212 was significantly more sensitive to osmotic stress (0.6 or 0.8 M NaCl, 1.2 or 1.6 M sorbitol) than the wild type and the algU mutant complemented with pME6221 (Table 4). After 24 h of incubation, the numbers of CFU obtained from NaCl-stressed cultures of the algU mutant were about 10 to 30 times lower than the numbers of CFU obtained from cultures of the wild type and the complemented mutant exposed to the same stress (data not shown). Constitutive expression of algU from the lac promoter in CHA0/pME6555 made the strain hypersensitive to osmotic stress instead of protecting it (Table 4). Since high levels of AlgU may be toxic to bacterial cells (22, 55), this may have accounted for the increased sensitivity of strain CHA0/pME6555 under stress conditions. Mutant CHA213M lacking the anti-sigma factor MucA exhibited stress tolerance similar to that of the wild type (Table 4). Analogous results were obtained when bacterial strains were exposed to 1.0 M NaCl (data not shown). None of the strains tested was able to grow in medium supplemented with 1.2 M NaCl. In conclusion, AlgU is essential for adaptation of P. fluorescens to osmotic stress, but tolerance towards this stress apparently cannot be improved by overexpression of AlgU.

TABLE 4.

Effect of osmotic stress on the growth of P. fluorescens CHA0 and derivatives of this strain

| Straina | Genotype | Doubling time (h)b

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without stress | 0.6 M NaCl | 0.8 M NaCl | 1.2 M Sorbitol | 1.6 M Sorbitol | ||

| CHA0 | Wild type | 0.72 a | 1.63 c | 3.75 c | 1.88 b | 3.05 b |

| CHA212 | ΔalgU | 0.72 a | 2.01 b | 7.83 a | 2.82 a | NGc |

| CHA212/pME6221 | ΔalgU/algU+ | 0.72 a | 1.71 c | 3.97 c | 1.92 b | 3.72 b |

| CHA0/pME6555 | Plac-algU+mucA+ | 0.73 a | 2.53 a | 6.23 b | 1.94 b | 5.59 a |

| CHA213M | ΔmucA | 0.75 a | 1.73 c | 4.03 c | ND | ND |

| CHA213M/pME6219 | ΔmucA/mucA+ | 0.73 a | 1.72 c | 3.79 c | ND | ND |

Bacteria were grown at 30°C in KMB broth with and without NaCl or sorbitol.

Doubling time was calculated from OD600 values determined during the exponential growth phase (six to eight measurements). During this time the relationship of OD600 values to CFU counts was linear (data not shown). The data are means based on three independent experiments, and three replicate cultures were used for each experiment. Values in the same column followed by different letters are significantly different at P = 0.05 (Student's t test). ND, not determined.

NG, no measurable growth during 48 h.

AlgU is essential for tolerance of P. fluorescens towards desiccation stress in vitro and in soil microcosms.

To investigate whether AlgU contributes to tolerance of P. fluorescens towards desiccation stress, strain CHA0 and algU and mucA mutants of this strain were exposed to desiccation stress under various conditions. In the first series of experiments, bacterial colonies grown on filter disks were slowly desiccated for 24 h or were kept at a constant humidity (see Materials and Methods). The numbers of CFU obtained from desiccated colonies of wild-type strain CHA0 were 7% of the numbers of CFU obtained from nondesiccated control colonies. The algU mutant CHA212 did not survive this treatment (<0.1% survival). Complementation of strain CHA212 with algU+ plasmid pME6221 restored survival to wild-type levels (9%). mucA mutant CHA213M had a wild-type level of survival (8%), suggesting that a lack of AlgU inhibition and enhanced EPS production do not improve survival in response to desiccation stress.

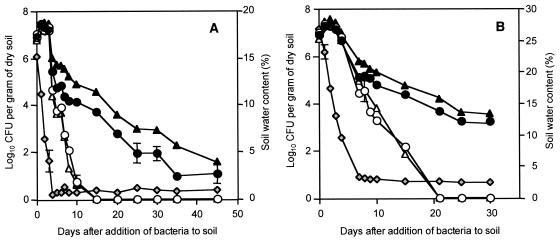

In a second series of experiments, the contribution of AlgU to the stress tolerance of P. fluorescens was examined in desiccating artificial and natural soil microcosms. The population dynamics of wild-type strain CHA0 and mutants of this strain were monitored for several weeks and were related to the decrease in the soil water content. In a sterile mixture of vermiculite and quartz sand that mimicked formulation conditions, the sizes of the populations of all bacterial strains started to decline at soil water contents below 5% (Fig. 3A), which corresponded to a soil ΨW of about −0.5 MPa. The decline in the size of the population was much more rapid for algU mutant CHA212, and the number of CFU per gram (dry weight) of soil was up to 4 log units lower than the value obtained for the wild type 10 days after bacteria were added to the soil (Fig. 3A). From day 15, no cultivable cells of the algU mutant were recovered from the soil (Fig. 3A). In contrast, wild-type strain CHA0 was detected for up to 60 days after inoculation (Fig. 3A; data not shown). Interestingly, strain CHA212 complemented with intact algU carried by pME6221 appeared to be slightly more tolerant towards desiccation stress than the wild type, whereas introduction of cloning vector pME6010ΔB alone had no effect on the sensitivity to stress (Fig. 3A). No significant differences among the strains tested were observed in control experiments in which the water content of the vermiculite-sand mixture was kept constant at 15%. Under these conditions, the bacterial population densities remained stable at about 0.6 × 107 to 1.1 × 107 CFU/g (dry weight) of soil throughout the 6-week experiment.

FIG. 3.

Survival of P. fluorescens. Strain CHA0 (wild type) (●) and its derivatives CHA212 (ΔalgU) (○), CHA212/pME6010ΔB (ΔalgU/−) (▵), and CHA212/pME6221 (ΔalgU/algU+) (▴) were included in a desiccating sterile artificial soil consisting of a mixture of quartz sand and vermiculite (A) and in a desiccating natural sandy loam soil (B). For microcosms containing natural soil, rifampin-resistant derivatives of the bacterial strains were used as inoculants. The soil water content ( ) at different times is shown only for the treatment with wild-type strain CHA0 since it did not vary among the different treatments. In the artificial soil, water contents of 15, 10, 5, 1, and 0.5% corresponded to soil ΨW of about −0.01, −0.03, −0.5, −2.7, and −40 MPa, respectively. In the natural soil, water contents of 20, 15, 10, and 1% corresponded to ΨW of about −0.03, −1.5, −3.0, and −9.5 MPa, respectively. The data are means ± standard deviations based on three experiments. Some of the error bars were too small to be included.

) at different times is shown only for the treatment with wild-type strain CHA0 since it did not vary among the different treatments. In the artificial soil, water contents of 15, 10, 5, 1, and 0.5% corresponded to soil ΨW of about −0.01, −0.03, −0.5, −2.7, and −40 MPa, respectively. In the natural soil, water contents of 20, 15, 10, and 1% corresponded to ΨW of about −0.03, −1.5, −3.0, and −9.5 MPa, respectively. The data are means ± standard deviations based on three experiments. Some of the error bars were too small to be included.

Similar results were obtained when strain CHA0 and algU mutant CHA212 were exposed to desiccation stress in a natural, nonsterile, sandy loam soil (Fig. 3B). For this experiment, the rifampin-resistant derivatives CHA0-Rif and CHA212-Rif (Table 1) were used. These derivatives were indistinguishable from their parent strains in terms of growth, EPS production, and tolerance towards osmotic stress and desiccation on filter disks (data not shown). The natural soil had a better water retention capacity than the artificial soil, which resulted in a lower desiccation rate and, consequently, in less rapid declines in the sizes of the bacterial populations (Fig. 3B). However, as soon as the soil water content dropped below a critical level, about 5% (i.e., a ΨW of about −4.9 MPa), the algU mutant again was significantly more sensitive to desiccation stress than the wild type or the complemented mutant (Fig. 3B). In natural soil kept at a constant moisture level, the sizes of the populations of all bacterial strains remained at equally high levels, and there was a slight decline from 107 to 106 CFU/g (dry weight) of soil until the end of the 30-day experiment. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the sigma factor AlgU is a crucial determinant in the adaptation of P. fluorescens to desiccation stress.

AlgU is not required for tolerance of P. fluorescens towards ROIs and heat.

AlgU contributes to the tolerance of the pathogens P. aeruginosa and P. syringae towards certain agents that generate ROIs and towards heat (26, 32). To determine whether inactivation of algU or mucA affected the susceptibility of P. fluorescens to ROIs, wild-type strain CHA0, algU mutant CHA212, and mucA mutant CHA213M were exposed to 1.9% (wt/vol) paraquat, 3% (vol/vol) hydrogen peroxide, or 5% (vol/vol) sodium hypochlorite. Table 5 shows that both mutants displayed wild-type susceptibility to these agents. Additional experiments in which the concentrations of the ROI-generating agents were increased up to 10-fold gave analogous results (data not shown). In contrast, an algU mutant (PAO6852) of P. aeruginosa, which was included as a control in the same experiment, was significantly more sensitive to paraquat, but not to H2O2 and NaOCl, than wild-type strain PAO1 and mucoid strain PAO568 were (Table 5), confirming previous data of Martin et al. (32). A series of experiments was then performed to evaluate the role of AlgU in tolerance of P. fluorescens towards heat killing. Exponential-growth-phase cultures of strain CHA0 and algU mutant CHA212 were exposed to 42 or 48°C for 5 to 90 min. However, in none of the experiments was there a significant difference in viability between the wild type and the algU mutant (data not shown). In an experiment in which we screened for additional factors that may involve the AlgU-mediated stress response, we found no differences in the tolerance of strain CHA0 and its algU mutant towards a series of other stresses, including exposure to the strong reducing agent dithiothreitol (8 mM), which triggers RpoE function in E. coli (44), exposure to a range of antibiotics, and exposure to pH extremes (data not shown). In summary, these results suggest that AlgU is not required for tolerance towards ROIs and heat in P. fluorescens, in marked contrast to the role of this sigma factor in P. aeruginosa, P. syringae, and E. coli.

TABLE 5.

Sensitivity to killing by ROIs in algU and mucA mutants of P. fluorescens and P. aeruginosa

| Strain | Characteristics | Mean diam of growth inhibition zone (mm) with:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paraquat (1.9%) | H2O2 (3%) | NaOCl (5%) | ||

| P. fluorescens strains | ||||

| CHA0 | Nonmucoid, wild type | 18.0 a | 12.0 a | 6.5 a |

| CHA212 | Nonmucoid, ΔalgU | 17.0 a | 12.0 a | 6.5 a |

| CHA213M | Mucoid, ΔmucA | 19.0 a | 12.5 a | 6.5 a |

| P. aeruginosa strains | ||||

| PAO1 | Nonmucoid, wild type | 14.0 y | 7.5 x | 7.0 x |

| PAO6852 | Nonmucoid, algU::Tcr | 22.0 x | 9.5 x | 8.5 x |

| PAO568 | Mucoid, mucA2 | 14.0 y | 9.0 x | 8.0 x |

Sensitivities to paraquat, H2O2, and NaOCl are expressed as the diameters of the growth inhibition zones surrounding filter disks impregnated with 10-μl portions of the agents. The data are means based on three replicates. Values in the same column followed by different letters (a for P. fluorescens, x and y for P. aeruginosa) are significantly different at P = 0.05 (Student's t test).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we identified the algU-mucA-mucB gene cluster in the plant-beneficial strain P. fluorescens CHA0; this gene arrangement is conserved in P. aeruginosa (12, 31, 33) and P. syringae (26). In P. aeruginosa, the algU, mucA, and mucB genes are cotranscribed and encode (respectively) the sigma factor AlgU and its main negative regulators, MucA and MucB, which act in concert to control production of the EPS alginate and the response to extreme environmental stress (19, 32, 50, 54, 57, 70). In P. syringae, AlgU is also a major determinant in the regulation of alginate biosynthesis and stress response (26). Here, we provide evidence that on the one hand, AlgU of P. fluorescens is functionally equivalent to its counterparts in pathogenic pseudomonads with respect to control of EPS production. On the other hand, the role of AlgU in the stress response of P. fluorescens is distinct from its role in the stress responses of other bacteria.

Regulation of EPS production.

In P. fluorescens CHA0, EPS production was regulated by at least four mechanisms. First, the level of algU expression was important. This was seen most clearly in a strain with moderate algU overexpression, CHA0/pME6220, which overproduced EPS (Table 2). The level of algU expression is determined by AlgU itself: expression of an algU′-′lacZ reporter was about 40% lower in an algU mutant than in wild-type strain CHA0 (Fig. 2A; Table 3). AlgU autoregulation has also been described for P. aeruginosa (12, 22). The algU promoter region in P. fluorescens CHA0 was found to contain two putative AlgU/RpoE recognition sequences. In P. aeruginosa, the corresponding promoters are designated P1 and P3, and they are absolutely dependent on AlgU (56). Second, the anti-sigma factor MucA made a major contribution to EPS production. Without MucA the EPS levels were 100-fold higher than those in a MucA+ background (Table 2). In contrast, the (indirect) effect of MucA on algU transcription was relatively small (Table 3). Third, the GacS-GacA two-component system was essential to sustain high EPS productivity in a mucA mutant (Table 2). This positive effect of the transcriptional regulator GacA was not mediated by AlgU (Table 3). Fourth, the hypermucoid phenotype of strains CHA211 (mucA::Tn5) and CHA0/pME6555 (Plac-algU+mucA+) points to negative AlgU control by MucB, as in P. aeruginosa (36, 50).

Role of AlgU in tolerance towards environmental stress.

Little is known about the regulatory mechanisms that determine adaptation of plant-beneficial pseudomonads to environmental stress. The present study established that AlgU is a second sigma factor, in addition to RpoS (52), involved in the response of P. fluorescens to extreme environmental stress. Our work shows, for the first time, that AlgU is a key determinant in the tolerance of P. fluorescens towards desiccation stress, since the survival of an algU mutant was severely impaired when the organism was exposed to desiccation in vitro, in a vermiculite-sand mixture mimicking formulation conditions, and in natural soil (Fig. 3). Furthermore, this sigma factor was important in the adaptation of P. fluorescens to high-osmolarity conditions (Table 4), and high concentrations of NaCl or sorbitol stimulated algU expression in both P. fluorescens (Table 3; Fig. 2) and P. syringae (26). Since plant-associated pseudomonads may be exposed to dry and osmotically harsh conditions in the rhizosphere and in the phyllosphere, the capacity to adapt to these conditions is likely to be important for colonization of these plant surfaces (26, 42, 63).

High osmolarity and ethanol (as a dehydrating agent) enhance transcription of alginate biosynthesis genes in P. aeruginosa (1, 11, 14, 71) and P. syringae (48). Osmotic stress and dehydration stress also stimulate, to a limited extent, alginate production in P. syringae and certain P. fluorescens strains (49, 58). However, exposure of nonmucoid P. aeruginosa (1, 56) or P. fluorescens CHA0 (unpublished data) to osmotic stress does not fully induce EPS synthesis, indicating that other environmental factors and cellular regulators are required for full activation of the EPS biosynthesis genes. Remarkably, the highly mucoid, algU-overexpressing or mucA mutants of P. fluorescens CHA0 did not display improved tolerance towards osmotic stress (Table 4) and desiccation in vitro and in soil microcosms (Table 5; unpublished data). This might argue against a protective role for EPS in P. fluorescens CHA0. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that the soil conditions used were not conducive to enhanced EPS production by the mucoid variants. In this context it is noteworthy that mucoid mutants of P. fluorescens CHA0 have exhibited an improved ability to form biofilms on roots (2). However, it is also possible that the (low) wild-type level of EPS production was already sufficient for maximum EPS-mediated stress protection of the bacterium and that stress defense may not be further optimized by EPS overproduction.

At present, it is difficult to explain the fact that the algU-overexpressing mutants (i.e., CHA213M and CHA0/pME6555) (Table 3) failed to be more stress tolerant than wild-type strain CHA0, as we expected these mutants to overexpress defense-related functions in addition to EPS overproduction. One possibility is that AlgU acts as an on-off switch which, when activated, drives the expression of stress defense-related genes. This system may operate until a certain level of saturation of available active AlgU is reached; beyond this level, AlgU may even become toxic to the cell.

Interestingly, an algU mutant of P. fluorescens CHA0 was not hypersensitive to a high temperature (48°C) (data not shown) or paraquat, H2O2, and NaClO (Table 5). This contrasts with the demonstrated involvement of AlgU in tolerance towards these stresses in P. aeruginosa (32, 54, 56, 70) and in P. syringae (26). Activation of algU by ROIs may help these pathogens withstand the oxidative burst associated with host defense responses (19, 26). This AlgU-mediated mechanism may not be required in the nonpathogenic strain P. fluorescens CHA0, as this bacterium may not be critically exposed to the plant defense response. Alternatively, the sigma factor RpoS, which is required for tolerance towards oxidative stress in the closely related plant-beneficial bacterium P. fluorescens Pf-5 (52), might ensure protection of strain CHA0 from plant ROIs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Swiss Federal Office for Education and Science (project C99.0032, COST action 830) and the Swiss Priority Program Biotechnology (project 5002-04502311).

We thank Patrick Michaux for help with some of the experiments. We are grateful to Stephan Heeb, Cécile Gigot-Bonnefoy, and Cornelia Reimmann for advice and to Fabio Mascher for help with determining the soil ψW.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berry A, DeVault J D, Chakrabarty A M. High osmolarity is a signal for enhanced algD transcription in mucoid and nonmucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2312–2317. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2312-2317.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bianciotto V, Andreotti S, Balestrini R, Bonfante P, Perotto S. Mucoid mutants of the biocontrol strain Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0 show increased ability in biofilm formation on mycorrhizal and nonmycorrhizal carrot roots. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2001;14:255–260. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloemberg G V, Lugtenberg B J J. Molecular basis of plant growth promotion and biocontrol by rhizobacteria. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2001;4:343–350. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(00)00183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boucher J C, Yu H, Mudd H, Deretic V. Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: characterization of muc mutations in clinical isolates and analysis of clearance in a mouse model of respiratory infection. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3838–3846. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3838-3846.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boucher J C, Martinez-Salazar J, Schurr M J, Mudd M H, Yu H, Deretic V. Two distinct loci affecting conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis encode homologs of the serine protease HtrA. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:511–523. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.511-523.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boucher J C, Schurr M J, Yu H, Rowen D W, Deretic V. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: role of mucC in the regulation of alginate production and stress sensitivity. Microbiology. 1997;143:3473–3480. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-11-3473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boulnois G J, Varley J M, Sharpe G S, Franklin F C H. Transposon donor plasmids, based on ColIb-P9, for use in Pseudomonas putida and a variety of other gram negative bacteria. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;200:65–67. doi: 10.1007/BF00383313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bull C T, Duffy B, Voisard C, Défago G, Keel C, Haas D. Characterization of spontaneous gacS and gacA regulatory mutants of Pseudomonas fluorescens biocontrol strain CHA0. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 2001;79:327–336. doi: 10.1023/a:1012061014717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castañeda M, Guzmán J, Moreno S, Espín G. The GacS sensor kinase regulates alginate and poly-β-hydroxybutyrate production in Azotobacter vinelandii. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2624–2628. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.9.2624-2628.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Del Sal G, Manfioletti G, Schneider C. A one-tube plasmid DNA mini-preparation suitable for sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9878. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.20.9878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeVault J D, Kimbara K, Chakrabarty A M. Pulmonary dehydration and infection in cystic fibrosis: evidence that ethanol activates alginate gene expression and induction of mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:737–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeVries C A, Ohman D E. Mucoid-to-nonmucoid conversion in alginate-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa often results from spontaneous mutations in algT, encoding a putative alternative sigma factor, and shows evidence of autoregulation. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6677–6687. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6677-6687.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dubois M, Gilles K A, Hamilton J K, Rebers P A, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28:350–356. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards K J, Saunders N A. Real-time PCR used to measure stress-induced changes in the expression of the genes of the alginate pathway of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Appl Microbiol. 2001;91:29–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farinha M A, Kropinski A M. High efficiency electroporation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa using frozen cell suspensions. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;70:221–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb13982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fett W F, Wells J M, Cescutti P, Wijey C. Identification of exopolysaccharides produced by fluorescent pseudomonads associated with commercial mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) production. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:513–517. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.2.513-517.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fett W F, Osman S F, Fisman M L, Siebles T S., III Alginate production by plant-pathogenic pseudomonads. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;52:466–473. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.3.466-473.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gacesa P. Bacterial alginate biosynthesis—recent progress and future prospects. Microbiology. 1998;144:1133–1143. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-5-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Govan J, Deretic V. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:539–574. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.3.539-574.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haas D, Blumer C, Keel C. Biocontrol ability of fluorescent pseudomonads genetically dissected: importance of positive feedback regulation. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2000;11:290–297. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(00)00098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heeb S, Itoh Y, Nishijyo T, Schnider U, Keel C, Wade J, Walsh U, O'Gara F, Haas D. Small, stable shuttle vectors based on the minimal pVS1 replicon for use in gram-negative, plant-associated bacteria. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2000;13:232–237. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hershberger C D, Ye R W, Parsek M R, Xie Z D, Chakrabarty A M. The algT (algU) gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a key regulator involved in alginate biosynthesis, encodes an alternative ς factor (ςE) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7941–7945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jørgensen F, Bally M, Chapon-Herve V, Michel G, Lazdunski A, Williams P, Stewart G S A B. RpoS-dependent stress tolerance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology. 1999;145:835–844. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-4-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keel C, Défago G. Interactions between beneficial soil bacteria and root pathogens: mechanisms and ecological impact. In: Gange A C, Brown V K, editors. Multitrophic interactions in terrestrial systems. London, United Kingdom: Blackwell Science; 1997. pp. 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keel C, Voisard C, Berling C-H, Kahr G, Défago G. Iron sufficiency, a prerequisite for suppression of tobacco black root rot by Pseudomonas fluorescens strain CHA0 under gnotobiotic conditions. Phytopathology. 1989;79:584–589. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keith L M W, Bender C L. AlgT (ς22) controls alginate production and tolerance to environmental stress in Pseudomonas syringae. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7176–7184. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.23.7176-7184.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King E O, Ward M K, Raney D E. Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescein. J Lab Clin Med. 1954;44:301–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Labes M, Pühler A, Simon R. A new family of RSF1010-derived expression and lac-fusion broad-host-range vectors for Gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1990;89:37–46. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laville J, Voisard C, Keel C, Maurhofer M, Défago G, Haas D. Global, stationary-phase control in Pseudomonas fluorescens mediating antibiotic synthesis and suppression of black root rot of tobacco. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1562–1566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liao C H, McCallus D E, Fett W F. Molecular characterization of two gene loci required for production of the key pathogenicity factor pectate lyase in Pseudomonas viridiflava. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1994;7:391–400. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-7-0391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin D W, Holloway B W, Deretic V. Characterization of a locus determining the mucoid status of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: algU shows sequence similarities with a Bacillus sigma factor. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1153–1164. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.1153-1164.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin D W, Schurr M J, Yu H, Deretic V. Analysis of promoters controlled by the putative sigma factor AlgU regulating conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: relationship to ςE and stress response. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6688–6696. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6688-6696.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin D W, Schurr M J, Mudd M H, Deretic V. Differentiation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa into the alginate-producing form: inactivation of mucB causes conversion to mucoidy. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:497–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin D W, Schurr M J, Mudd M H, Govan J R, Holloway B W, Deretic V. Mechanism of conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infecting cystic fibrosis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8377–8381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martínez-Salazar J M, Moreno S, Nájera R, Boucher J C, Espín G, Soberón-Chávez G, Deretic V. Characterization of the genes coding for the putative sigma factor AlgU and its regulators MucA, MucB, MucC, and MucD in Azotobacter vinelandii and evaluation of their roles in alginate biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1800–1808. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.1800-1808.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mathee K, McPherson C J, Ohman D E. Posttranslational control of the algT (algU)-encoded ς22 for expression of the alginate regulon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and localization of its antagonist proteins MucA and MucB (AlgN) J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3711–3720. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.11.3711-3720.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maurhofer M, Keel C, Haas D, Défago G. Pyoluteorin production by Pseudomonas fluorescens strain CHA0 is involved in the suppression of Pythium damping-off of cress but not of cucumber. Eur J Plant Pathol. 1994;100:221–232. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maurhofer M, Reimmann C, Schmidli-Sacherer P, Heeb S, Haas D, Défago G. Salicylic acid biosynthetic genes expressed in Pseudomonas fluorescens strain P3 improve the induction of systemic resistance in tobacco against tobacco necrosis virus. Phytopathology. 1998;88:678–684. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1998.88.7.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.May T B, Chakrabarty A M. Isolation and assay of Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate. Methods Enzymol. 1994;235:295–304. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McComb E A, McCready R M. Determination of acetyl in pectin and in acetylated carbohydrate polymers. Hydroxamic acid reaction. Anal Chem. 1957;29:819–821. [Google Scholar]

- 41.McInnes K J, Weaver R W, Savage M J. Soil water potential. In: Mickelson S H, editor. Methods of soil analysis, part 2. Madison, Wis: Soil Science Society of America; 1994. pp. 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller K J, Wood J M. Osmoadaptation by rhizosphere bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:101–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minton N P. Improved plasmid vectors for the isolation of translational lacZ fusions. Gene. 1984;31:269–273. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Missiakas D, Raina S. The extracytoplasmic function sigma factors: role and regulation. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1059–1066. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Natsch A, Keel C, Pfirter H A, Haas D, Défago G. Contribution of the global regulator gene gacA to persistence and dissemination of Pseudomonas fluorescens biocontrol strain CHA0 introduced into soil microcosms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2553–2560. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2553-2560.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ophir T, Gutnick D L. A role for exopolysaccharides in the protection of microorganisms from desiccation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:740–745. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.2.740-745.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pedersen S S, Espersen F, Høiby N, Shand G H. Purification, characterization, and immunological cross-reactivity of alginates produced by mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa from patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:691–699. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.4.691-699.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peñaloza-Vàzquez A, Kidambi S P, Chakrabarty A M, Bender C L. Characterization of the alginate biosynthetic gene cluster in Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4464–4472. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.14.4464-4472.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roberson E B, Firestone M K. Relationship between desiccation and exopolysaccharide production in a soil Pseudomonas sp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1284–1291. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.4.1284-1291.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rowen D W, Deretic V. Membrane-to-cytosol redistribution of ECF sigma factor AlgU and conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:314–327. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sarniguet A, Kraus J, Henkels M D, Muehlchen A M, Loper J E. The sigma factor ςS affects antibiotic production and biological control activity of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:12255–12259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schnider U, Keel C, Voisard C, Defago G, Haas D. Tn5-directed cloning of pqq genes from Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0: mutational inactivation of the genes results in overproduction of the antibiotic pyoluteorin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3856–3864. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.11.3856-3864.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schurr M J, Deretic V. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: co-ordinate regulation of heat-shock response and conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:411–420. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3411711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schurr M J, Martin D W, Mudd M H, Deretic V. Gene cluster controlling conversion to alginate-overproducing phenotype in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: functional analysis in a heterologous host and role in the instability of mucoidy. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3375–3382. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3375-3382.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schurr M J, Yu H, Boucher J C, Hibler N S, Deretic V. Multiple promoters and induction by heat shock of the gene encoding the alternative sigma factor AlgU (ςE) which controls mucoidy in cystic fibrosis isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5670–5679. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5670-5679.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schurr M J, Yu H, Martinez-Salazar J M, Boucher J C, Deretic V. Control of AlgU, a member of the ςE-like family of stress sigma factors, by the negative regulators MucA and MucB and Pseudomonas aeruginosa conversion to mucoidy in cystic fibrosis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4997–5004. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4997-5004.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Singh S, Koehler B, Fett W. Effect of osmolarity and dehydration on alginate production by fluorescent pseudomonads. Curr Microbiol. 1992;25:335–339. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stanisich V A, Holloway B W. A mutant sex factor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Genet Res. 1972;19:91–108. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300014294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Storz G, Hengge-Aronis R. Bacterial stress responses. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Suh S J, Siloh-Suh L, Woods D E, Hassett D J, West S E H, Ohman D E. Effect of rpoS mutation on the stress response and expression of virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3890–3897. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.13.3890-3897.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thomashow L S, Weller D M. Current concepts in the use of introduced bacteria for biological disease control. In: Stacey G, Keen N, editors. Plant-microbe interactions. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Chapman & Hall; 1995. pp. 187–235. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Van Veen J A, Van Overbeek L S, Van Elsas J D. Fate and activity of microorganisms introduced into soil. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:121–135. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.2.121-135.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vieira J, Messing J. New pUC-derived cloning vectors with different selectable markers and DNA replication origins. Gene. 1991;100:189–194. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90365-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Voisard C, Bull C, Keel C, Laville J, Maurhofer M, Schnider U, Défago G, Haas D. Biocontrol of root diseases by Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0: current concepts and experimental approaches. In: O'Gara F, Dowling D, Boesten B, editors. Molecular ecology of rhizosphere microorganisms. Weinheim, Germany: VCH Publishers; 1994. pp. 67–89. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Voisard C, Rella M, Haas D. Conjugative transfer of plasmid RP1 to soil isolates of Pseudomonas fluorescens is facilitated by certain large RP1 deletions. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1988;55:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Willis D K, Holmstadt J J, Kinscherf T G. Genetic evidence that loss of virulence associated with gacS or gacA mutations in Pseudomonas syringae B728a does not result from effects on alginate production. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:1400–1403. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.3.1400-1403.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wozniak D J, Ohman D E. Transcriptional analysis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa genes algR, algB, and algD reveals a hierarchy of alginate gene expression which is modulated by algT. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6007–6014. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.6007-6014.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xie Z, Hershberger C D, Shankar S, Ye R W, Chakrabarty A M. Sigma factor–anti-sigma factor interaction in alginate synthesis: inhibition of AlgT by MucA. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4990–4996. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4990-4996.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yu H, Schurr M J, Deretic V. Functional equivalence of Escherichia coli ςE and Pseudomonas aeruginosa AlgU: E. coli rpoE restores mucoidy and reduces sensitivity to reactive oxygen intermediates in algU mutants of P. aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3259–3268. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3259-3268.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zielinski N A, Maharaj R, Roychoudhury S, Danganan C E, Hendrickson W, Chakrabarty A M. Alginate synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: environmental regulation of the algC promoter. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7680–7688. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.23.7680-7688.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]