Abstract

Background

Cardiac damage is common in patients with acute brain injury; however, little is known regarding cardiac-induced neurological symptoms. In the International Classification of Headache, Third Edition (ICHD-III), cardiac cephalalgia is classified as a headache caused by impaired homeostasis.

Methods

This report presents four patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) who presented with headache that fulfilled the ICHD-III diagnostic criteria for cardiac cephalalgia. A systematic review of cardiac cephalalgia using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses guidelines is also presented.

Results

Case 1: A 69-year-old man with a history of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) developed sudden severe occipital pain, nausea, and cold sweating. Coronary angiography (CAG) revealed occlusion of the right coronary artery (RCA). Case 2: A 66-year-old woman complained of increasing occipitalgia and chest discomfort while riding a bicycle. CAG demonstrated 99% stenosis of the left anterior descending artery. Case 3: A 54-year-old man presented with faintness, cold sweating, and occipitalgia after eating lunch. CAG detected occlusion of the RCA. Case 4: A 72-year-old man went into shock after complaining of a sudden severe headache and nausea. Vasopressors were initiated and emergency CAG was performed, which detected three-vessel disease. In all four, electrocardiography (ECG) showed ST segment elevation or depression and echocardiography revealed a left ventricular wall motion abnormality. All patients underwent PCI, which resulted in headache resolution after successful coronary reperfusion. A total of 59 cases of cardiac cephalalgia were reviewed, including the four reported here. Although the typical manifestation of cardiac cephalalgia is migraine-like pain on exertion, it may present with thunderclap headache without a trigger or chest symptoms, mimicking subarachnoid hemorrhage. ECG may not always show an abnormality. Headaches resolve after successful coronary reperfusion.

Conclusions

Cardiac cephalalgia resulting from AMI can present with or without chest discomfort and even mimic the classic thunderclap headache associated with SAH. It should be recognized as a neurological emergency and treated without delay.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12245-022-00436-2.

Keywords: Cardiac cephalalgia, Cardiac cephalgia, Acute myocardial ischemia, Thunderclap headache, Neurological Emergency

Background

The interaction between the brain and the heart is an emerging area of clinical interest. Cardiac damage is common in patients with acute brain injury. Neurogenic stress cardiomyopathy (also known as neurogenic stunned myocardium) is widely recognized in patients with acute neurological disease [1]; however, little is known regarding cardiac-induced neurological symptoms. In 1997, Lipton et al. reported two cases of exertional headache associated with myocardial ischemia; based on these and a review of five similar previous ones, they coined the term “cardiac cephalgia” (“cardiac cephalalgia” in the current classification) [2]. In the International Classification of Headache, Third Edition (ICHD-III) [3], cardiac cephalalgia is classified as a headache caused by impaired homeostasis (Table 1). Cardiac cephalalgia is described as migraine-like headache that occurs during an episode of myocardial ischemia and is usually aggravated by exercise. The diagnosis can be challenging because cardiac cephalalgia is uncommon and the headache is not always associated with exertion; headache may occur at rest without chest symptoms [4–6]. Only a few reported cases of cardiac cephalalgia presented with sudden severe headache (thunderclap headache), which mimics subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) [7–10]. Both myocardial ischemia and SAH are potentially life-threatening; therefore, early recognition with appropriate treatment is critically important. Consequently, it is essential to understand the characteristics of cardiac cephalalgia as a neurological emergency and accurately diagnose it to enable appropriate intervention. This report presents four patients diagnosed with cardiac cephalalgia and reviews the relevant literature to summarize the disease characteristics and current evidence regarding the diagnosis and treatment of this uncommon clinical entity.

Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria of cardiac cephalalgia

| A. Any headache fulfilling criterion C |

| B. Acute myocardial ischemia has been demonstrated |

| C. Evidence of causation demonstrated by at least two of the following: |

| 1. headache has developed in temporal relation to the onset of acute myocardial ischemia |

| 2. either or both of the following: |

| a) headache has significantly worsened in parallel with worsening of the myocardial ischemia |

| b) headache has significantly improved or resolved in parallel with improvement in or resolution of the myocardial ischemia |

| 3. headache has at least two of the following four characteristics: |

| a) moderate to severe intensity |

| b) accompanied by nausea |

| c) not accompanied by phototophia or phonophobia |

| d) aggravated by exertion |

| 4. headache is relieved by nitroglycerine or derivatives of it |

| D. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis |

Methods

Cases

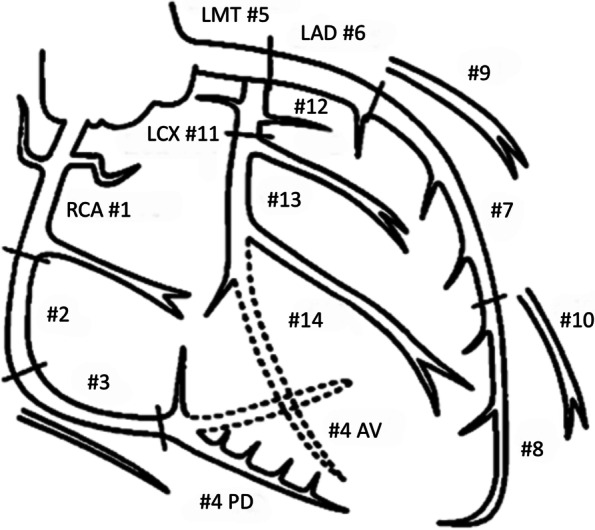

Since 2009, Osaka Mishima Emergency Critical Care Center has experienced four cases of headache that fulfilled the ICHD-III diagnostic criteria for cardiac cephalalgia. Characteristics of the four patients are summarized in Table 2 and briefly described below. Coronary artery lesions are described using the American Heart Association classification (Fig. 1) [11].

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| Case | Age | Sex | Site | Quality | Intensity | Onset | Autonomic signs | Cardiac symptoms | Trigger | ECG | Echocardiogram findings | Coronary lesion | Therapy | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 69 | M | Occipital- right shoulder | Pulsatile | Severe | Sudden | Nausea, cold sweating | None | None | ST elev in II, III, aVF | Inf wall akinesis | RCA (#2) 100% | PCI (RCA) | Resolved |

| 2 | 66 | F | Occipital | NA | Severe | Sudden | Cold sweating | Chest discomfort | Bicycle | ST elev in II, III, aVF, V1-4 | Takotsubo | LAD (#7) 99% | Heparin, PCI (LAD) | Resolved |

| 3 | 54 | M | Posterior neck-occipital | Strangulation | Moderate | Gradual | Cold sweating, faintness | Chest discomfort | Meal | ST elev in II, II, aVF, III AV block | Inf wall akinesis | RCA (#3) 100%, LAD (#7) 90%, LCX (#13) 100% | PCI (RCA) | Resolved |

| 4 | 72 | M | Headache | NA | Severe | Sudden | Nausea, vomiting | None | None | ST elev in aVR, II, III, aVF, ST dep in V2-5 | Lat, post, inf wall akinesis, ant-septal severe hypokinesis, mitral regurgitation | RCA (#3) 99%, LCX (#11) 99%, LAD (75%) | PCI (RCA), IABP, ECMO | Resolved/Died |

ECG electrocardiography, M male, F female, NA not available, elev elevation, inf inferior, lat lateral, post posterior, ant anterior, RCA right coronary artery, LAD left anterior descending artery, LCX left circumflex artery, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, IABP intra-aortic balloon pumping, ECMO extracorporeal membranous oxygenation

Fig. 1.

Coronary artery segments according to the American Heart Association classification [11]. RCA, right coronary artery; LCA, left coronary artery; LMT, left main trunk; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LCx, left circumflex coronary artery; AV, atrioventricular nodal artery; PD, posterior descending coronary artery

Literature review

The PubMed (National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) and Scopus (Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands) databases were searched in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses guidelines [12]. The terms "cardiac cephalalgia" OR "cardiac cephalgia" OR "headache and acute coronary syndrome" OR "headache and myocardial infarction" OR "anginal headache" were used without a publication year limitation. The references of each publication were also reviewed to find other potentially relevant reports. Only full-text English language studies were included. Duplicated patients were excluded.

Results

Case presentations

Case 1

A 69-year-old man with a 50-year history of smoking presented with sudden onset severe pulsatile occipitalgia during sleep. The headache was described as the worst in his life and was accompanied by nausea, cold sweating, and a five-minute episode of unconsciousness. He had a history of hypothyroidism and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in the left anterior descending artery (LAD) and the right coronary artery (RCA) for angina. Electrocardiography (ECG) in the ambulance during transport to the hospital showed ST elevation in leads II and III.

He was alert on arrival complaining of severe occipitalgia but no chest pain. Blood pressure was 132/70 mm Hg and heart rate was 57 beats per minute (bpm). Emergency head computed tomography (CT) showed no abnormalities. ECG showed ST segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF (Fig. 2). Echocardiography revealed akinesis of the inferior wall of the left ventricle. Blood chemistry studies showed no elevation of creatine kinase–myocardial band (CKMB) concentration (0.6 ng/mL; reference range, < 3.6 ng/mL). When repeatedly asked if he had any chest symptoms, he admitted to having slight chest discomfort. Emergency coronary angiography (CAG) was subsequently performed and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) was diagnosed. The angiogram revealed occlusion of segment 2 in the RCA (Fig. 3) and 75% stenosis of segment 12 in the left circumflex artery (LCX). During PCI for the occluded RCA, he went into ventricular fibrillation (VF), which recovered to sinus rhythm after electrical defibrillation. His headache subsided after treatment and he was discharged uneventfully 11 days later.

Fig. 2.

Electrocardiogram of case 1 shows ST segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF

Fig. 3.

Coronary angiogram of case 1 before A and after B percutaneous coronary intervention with stenting to segment 2. The occluded right coronary artery was recanalized

Case 2

A 66-year-old woman with a history of rheumatoid arthritis presented with sudden occipitalgia while riding a bicycle. The pain was moderate and gradually intensified over time. While resting, she reported chest discomfort and cold sweating. ECG during emergency transportation to the hospital showed ST segment elevation in leads V3–V5. On arrival, she was alert and profusely sweating. Blood pressure was 90/40 mm Hg and heart rate was 60 bpm. ECG showed ST segment elevation in leads II, III, aVF, and V2–V4. CKMB was normal (1.4 ng/mL) and troponin T was negative. Emergency head CT showed no intracranial hemorrhage. CT angiography disclosed a basilar–left superior cerebellar artery aneurysm 2 mm in diameter; no bleb was visualized. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain confirmed no hemorrhage and no arterial dissection. Therefore, the aneurysm was considered unruptured. Echocardiography revealed takotsubo-like abnormal movement with an ejection fraction of 30%.

She was initially treated with intravenous heparin. Although her headache subsided soon after admission, CKMB concentration the next day was 501.1 ng/mL. She underwent CAG 15 days later after cardiac function had been restored. A 99% stenosis was found in LAD segment 7 and stents were placed. She was discharged home uneventfully. Magnetic resonance (MR) angiography of the brain nine months later showed no change in aneurysmal size or shape.

Case 3

A 54-year-old man with a 30-year history of smoking presented with faintness, cold sweating, and nausea after eating lunch, followed by strangulating occipitalgia. He was taking medications for hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes. ST segment elevation was seen in leads II and III on ECG during transportation to the hospital. Upon arrival, he complained of moderate occipitalgia but no chest pain. Blood pressure was 66/38 mm Hg and heart rate was 44 bpm. ECG showed ST segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF. Echocardiography showed hypokinesis of the inferior wall. His headache subsided while being evaluated in the emergency room. CKMB concentration was elevated (22.8 ng/mL) and troponin T was positive; therefore, AMI was diagnosed. After initiation of vasopressors and temporary pacing, emergency CAG was performed, which showed occlusion of the RCA segment 3 and LCX segment 13, as well as 90% stenosis of the LAD segment 7. PCI was performed for the RCA, which was thought to be the culprit lesion. After hemodynamic stabilization, he underwent PCI for the LAD stenosis 15 days later. The LCX was considered a chronic occlusion and was not treated. He had no further headaches after the initial PCI and he was discharged 21 days later uneventfully.

Case 4

A 72-year-old man experienced a sudden severe headache with vomiting and called an ambulance. He was a heavy smoker and had a history of hypertension and Y-graft placement for an abdominal aortic aneurysm. When the emergency team arrived 10 min later, he was disoriented and incontinent of feces and urine. He did not complain of any chest symptoms. No obvious ST segment changes were noted on ECG during transportation to the hospital. On arrival, blood pressure was 106/82 mm Hg and heart rate was 64 bpm. He vomited and was intubated to secure the airway. ECG showed ST segment depression in leads I–III, aVF, and V2–V5 and ST elevation in aVR (Fig. 4). Echocardiography showed mitral regurgitation, akinesis of the posterior wall of the left ventricle, and hypokinesis in the anterior septum.

Fig. 4.

Electrocardiogram of case 4 shows ST segment depression in leads I–III, aVF, and V2–V5 and ST elevation in aVR

SAH associated with neurogenic stunned myocardium was suspected and head CT was immediately performed; no significant lesions were found. CT angiography showed no cerebrovascular abnormalities. CKMB concentration was normal (1.6 ng/mL) but troponin T was positive. His blood pressure declined to 50 mm Hg/unmeasurable after CT and heart rate declined to 30 bpm. After vasopressor support was initiated, emergency CAG was performed and revealed 99% stenosis of the RCA segment 3, 75% stenosis of the LAD segment 6, and 90% stenosis of the LCX segments 11 and 13. The patient underwent PCI for segment 3, which was considered the culprit lesion (Fig. 5). Then, an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) was placed and he was transferred to the cardiovascular department as a potential candidate for mitral valve replacement. He underwent veno-arterial extracorporeal membranous oxygenation and the IABP was later replaced with a catheter-based miniaturized ventricular assist device. He did not complain of headache upon awakening but died 38 days later due to hemorrhagic complications.

Fig. 5.

A Right coronary angiography of case 4 shows 99% stenosis of the right coronary artery segment 3. B Left coronary angiography shows 75% stenosis of the LAD segment 6 and 90% stenosis of the LCX segments 11 and 13. C Right coronary angiography after percutaneous coronary intervention with stenting to segment 3

Literature review

The literature search initially identified 721 potentially relevant articles. Forty-eight articles including 55 cases of cardiac cephalalgia met criteria (Supplementary File 1). After including the four patients reported here, a total of 59 cardiac cephalalgia cases were finally reviewed. Individual patient characteristics are shown in Table 3 [13–54] and summarized in Table 4.

Table 3.

Reported cases of cardiac cephalalgia

| Author | Year | Age | Sex | Site | Quality | Intensity | Onset | Duration | Autonomic signs | Cardiac symptoms | Trigger | ECG | Coronary lesion | Therapy | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caskey [13] | 1978 | 47 | M | Right eye | Pressing | Severe | NA | 30–40 s | None | Chest pain, l-arm pain | Rest, mild exercise | ST elevation | NA | Nitrate | Resolved |

| Lefkowitz [14] | 1982 | 62 | M | Bregmatic | Explosive | Severe | NA | NA | NA | Retrosternal pain, arm numbness | Stress, exertion | ST depression (stress) | 3 vessel | CABG | Resolved |

| Fleetcroft [15] | 1985 | 78 | F | Frontal | NA | NA | NA | NA | None | Chest tightness | Mild exercise, cold, meal | ST elevation | NA | Nitrates | Resolved |

| Blacky [16] | 1987 | 40 | M | Bitemporal | NA | NA | NA | NA | None | None | Vigorous exercise | ST depression (stress) | RCA | Nitrates | Resolved |

| Vernay [17] | 1989 | 71 | M | Occipital parietal frontal | NA | NA | NA | NA | None | Shoulder pain radiating to arms | Exertion, exercise, meal | ST depression (stress) | NA | Nitrates | Resolved |

| Takayanagi [18] | 1990 | 67 | M | Occipital | pulsating | Severe | NA | a few minutes | None | Chest pressure | Hot bath, sleeping, urination | ST elevation | NA | Nitrates | Died |

| Takayanagi [18] | 1990 | 64 | F | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Chest pain | NA | ST elevation | 3 vessel | Nitrates | Died |

| Bowen [19] | 1993 | 59 | M | Bitemporal | NA | Severe | Sudden | 10–30 m | None | Chest pressure, left arm pain | NA | ST depression | RCA, OM | PCI | Resolved |

| Ishida [20] | 1996 | 64 | M | Occipital | Throbbing | Severe | Sudden | 10 h | Nausea | Shoulder pain | Rest | ST depression (stress) | 3 vessel | PCI | Resolved |

| Lipton [2] | 1997 | 57 | M | Vertex | Sharp or shooting | Severe | Gradual | Minutes–hours | Nausea | Abdominal or chest pain | Vigorous exercise, sexual activity | ST depression (stress) | 3 vessel | CABG | Resolved |

| Lipton [2] | 1997 | 67 | M | Bifrontal | Squeezy, steadily, pressing | Severe | Gradual | Minutes–hours | None | None | Vigorous exercise | ST depression (stress) | 3 vessel | PCI | Resolved |

| Grace [21] | 1997 | 59 | M | Vertex occipital | Bursting | Severe | Sudden | Seconds | None | None | Mild exercise | ST depression (stress) | LAD, RCA | CABG | Relapse |

| Lance [22] | 1998 | 62 | M | Right frontal | NA | NA | Gradual | Minutes | None | Chest pain | Mild exercise | ST depression (stress) | LAD, RCA | CABG | Resolved |

| Lanza [23] | 2000 | 68 | M | Occipital | NA | NA | NA | NA | None | Shoulder pain | Rest | Peaked T in V2-4 | 3 vessel | CABG | Resolved |

| Lanza [23] | 2000 | 70 | M | Occipital | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | None | Rest | NA | 3 vessel | NA | NA |

| Amendo [24] | 2001 | 78 | F | Bitemporal | NA | Severe | NA | Hours | Vomiting | None | NA | ST elevation | 3 vessel | CABG | Resolved |

| Amendo [24] | 2001 | 77 | F | Right frontal and maxillary | NA | Severe | Acute | Hours | None | None | NA | Precordial R progression | Normal | NA | NA |

| Auer [25] | 2001 | 47 | M | Occipital | NA | NA | NA | Minutes–2 h | NA | NA | NA | ST elevation | LAD, RCA | Advanced life support | Died |

| Rambihar [26] | 2001 | 65 | F | Occipital | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Shoulder and left arm pain | Exercise, meal | ST depression (stress) | 3 vessel | CABG | Partially resolved |

| Famularo [27] | 2002 | 70 | M | Fronto-parietal bilateral | Sharp or shooting | Severe | NA | 2 d | None | Mid epigastric pain | NA | ST elevation | NA | Nitrates | Resolved |

| Gutierrez-Morlote [28] | 2002 | 59 | M | Vertex occipital bilateral | Dull and throbbing | Moderate-severe | Rapidly progressive | 1 d | Nausea, photophobia | Chest pain | Rest | ST depression | NA | Nitrates | Resolved |

| Martinez [29] | 2002 | 68 | F | Left hemicranial | Shooting | Severe | Gradual | 1 h | None | None | Mild exercise, exertion | ST elevation | 3 vessel | PCI | Resolved |

| Sathirapanya [30] | 2004 | 58 | M | Left occipital | Sharp or shooting | Severe | NA | 15–20 m | None | Chest tightness | Exertion | ST elevation | 3 vessel | CABG | Resolved |

| Chen [31] | 2004 | 76 | M | Bitemporal | Non-throbbing | Mild-severe | NA | 5 m | None | Chest pain | Rest, exertion | ST depression (stress) | LAD, RCA | Nitrates | Resolved |

| Gutierrez-Morlote [32] | 2005 | 74 | F | Bitemporal | Pulsating | Severe | NA | Minutes–hours | Nausea | Chest tightness | Rest | ST depression | NA | Nitrates | Resolved |

| Gutierrez-Morlote [32] | 2005 | 64 | F | Uni- or bilateral | Oppressive | Severe | Sudden | 1 h | None | None | Rest, mild exercise | NA | NA | NA | Died after resolution |

| Korantzopoulos [33] | 2005 | 73 | F | Occipital | Sharp | Severe | Sudden | 1 h | Nausea, vomiting | None | Rest | ST depression | LAD | Nitrates | Resolved |

| Cutrer [34] | 2006 | 55 | M | Biparietal | Non-throbbing | NA | Gradual | Minutes | None | None | Mild exercise, sexual activity | Normal | LAD, RCA | PCI | Resolved |

| Seow [7] | 2007 | 35 | M | NA | Explosive | Severe | Gradual | 1 d | Vomiting, cold sweating | None | NA | ST elevation | LAD | NA | Resolved |

| Broner [8] | 2007 | 72 | F | Occipital frontal bilateral | Sharp and throbbing | severe | Sudden | Hours | Nausea, vomiting pallor | None | Rest, exertion | ST elevation | RCA | Heparin | Resolved |

| Wei [35] | 2008 | 36 | M | Vertex to occipital bilateral | Dull | Severe | Rapidly progressive | NA | NA | NA | NA | ST elevation | LAD | PCI | Resolved |

| Wei [35] | 2008 | 85 | F | Right eye | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Chest pain | Exercise | NA | Normal | Nitrates | Resolved |

| Wang [36] | 2008 | 81 | F | NA | NA | Severe | NA | Hours | Dizziness, diaphoresis, nausea | VF | NA | ST elevation | RCX | PCI | Resolved |

| Dalzell [9] | 2009 | 44 | F | Occipital | NA | Severe | Sudden | NA | Nausea, vomiting, sweating | None | NA | ST elevation | RCA | PCI | Resolved |

| Sendovski [10] | 2009 | 61 | F | Forehead | NA | Severe | NA | NA | None | None | Exertion | ST depression | 3 vessel | PCI | Resolved |

| Chatzizisis [37] | 2010 | 42 | M | Frontal bitemporal | NA | Severe | Sudden | Hours | None | None | NA | ST elevation | LAD | PCI | Resolved |

| Cheng [38] | 2010 | 52 | F | Bilateral | Throbbing | Severe | Sudden | 3 d | None | Chest pain | Local anesthesia | Equivocal | Normal | Nitrates | Resolved |

| Cheng [38] | 2010 | 67 | F | Jaw, mandibula, bilateral temporoparietal | Throbbing | Severe | Sudden | 5 m | None | Exertional dyspnea | Exertion | Normal | 2 vessel | PCI | Resolved |

| Yang [39] | 2010 | 44 | F | Bifrontal | NA | Severe | NA | NA | Nausea | Chest tightness | Exertion | ST depression (stress) | spasm | Nitrates | Resolved |

| Costopoulos [40] | 2011 | 55 | M | Occipital | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | None | Exertion | ST depression | 3 vessel | Nitrates, CABG | Resolved |

| Elgharably [41] | 2013 | 55 | M | Frontal | NA | Severe | NA | > 12 h | None | None | NA | Q wave | LAD | PCI | Resolved |

| Asvestas [42] | 2014 | 86 | M | Occipital | NA | Severe | NA | NA | None | None | NA | ST depression | LCX, LAD | PCI | Resolved |

| Wassef [43] | 2014 | 44 | M | NA | Oppressive | Severe | NA | NA | None | Chest discomfort | Exertion | ST depression (stress) | LAD | PCI | Resolved |

| Mathew [44] | 2015 | 47 | M | Bioccipital to vertex | NA | Severe | NA | A few minutes | None | None | Exertion | NA | LAD | PCI | Resolved |

| Prakash [45] | 2015 | 67 | M | Posterior to holocephalic | Intense, excruciating | Severe | Sudden | 10–60 m | Nausea | None | Lifting heavy objects, sexual activities | ST depression (stress) | 3 vessel | CABG | Resolved |

| Chowdhury [46] | 2015 | 51 | M | Pre-auricula to forehead, vertex, occipital | NA | NA | NA | 2–3 m | None | Mild chest tightness and sweating | Stress, exertion | Mild ST-T change | LAD, LCX | PCI | Resolved |

| Huang [47] | 2016 | 70 | F | Bilateral posterior nuchal | Dull squeezing | NA | Sudden | NA | Dizziness | None | None | ST elevation | LAD | PCI | Resolved |

| Shankar [48] | 2016 | 73 | M | Generalized | Dull | NA | NA | 5 m | None | None | Exertion | ST depression (stress) | 3 vessel | CABG | Resolved |

| Wang [6] | 2017 | 40 | M | Bitemporal | Pulsatile, tight | Moderate-severe | NA | 5–10 m | Cold sweating | Chest discomfort, palpitations, | Exertion, cold stimuli, sexual activities | Inverted T | LAD, RCA, LCX, D | PCI | Resolved |

| Majumder [49] | 2017 | 48 | F | NA | NA | Severe | NA | Hours | None | None | Exertion | ST depression | LAD, RCA | PCI | Resolved |

| Lazari [50] | 2019 | 64 | M | Generalized | Compressing | Severe | Rapidly progressive | 5–15 m | None | None | NA | ST elevation | RCA | PCI | Resolved |

| MacIsaac [51] | 2019 | 86 | M | Bilateral, posterior | Dull | Severe | Progressive | 30–90 m | None | Chest pain | None | ST depression | RCA, LCX, D | Warfarin | Resolved |

| Santos [52] | 2019 | 62 | M | Holocranial | Aching | NA | NA | NA | None | Chest pain | None | Normal | 3 vessel | CABG | Died |

| Ruiz Ortiz [53] | 2020 | 74 | F | Vertex, Bitemporal | Oppressive | Moderate | NA | NA | None | None | Exertion | ST elevation | 3 vessel | PCI | Resolved |

| Sun [54] | 2021 | 83 | F | NA | Migraine-like | NA | NA | Hours | None | Chest pain | None | ST elevation | RCA | PCI | Resolved |

| Kobata | 2021 | 69 | M | Occipital | Pulsatile | Severe | Sudden | NA | Nausea, sweating | None | None | ST elevation | RCA | PCI | Resolved |

| Kobata | 2021 | 66 | F | Occipital | NA | Severe | Sudden | NA | Cold sweating | Chest discomfort | Exertion | ST elevation | LAD | PCI | Resolved |

| Kobata | 2021 | 54 | M | Occipital | Strangulation | Moderate | Gradual | NA | Cold sweating | Chest discomfort | Meal | ST elevation | 3 vessel | PCI | Resolved |

| Kobata | 2021 | 72 | M | NA | NA | Severe | Sudden | NA | Nausea, vomiting | None | None | ST elevation | 3 vessel | PCI | Resolved/Died |

M male, F female, NA not available, s second, m minute, h hours, d day, LAD left anterior descending artery, RCA right coronary artery, CX circumflex artery, OM obtuse marginal artery, D diagonal artery, CABG coronary artery bypass graft, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention

Table 4.

Clinical manifestations of cardiac cephalalgia

| Characteristics | Variable (N = 59) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Years (median, quartile) | 64 (54–72) |

| Sex | Male | 37 (62.7) |

| Triger | Exertion | 26 (44.1) |

| Other than exertion | 3 (5.1) | |

| None | 16 (27.1) | |

| NA | 14 (23.7) | |

| Onset | Sudden | 15 (25.4) |

| Progressive or gradual | 11 (18.6) | |

| NA | 33 (55.9) | |

| Side | Right | 4 (6.8) |

| Left | 2 (3.4) | |

| Bilateral | 23 (39.0) | |

| NA | 30 (50.8) | |

| Regions | Frontal | 10 (16.9) |

| Temporal | 7 (11.9) | |

| Parietal | 3 (5.1) | |

| Occipital | 23 (39.0) | |

| Whole | 6 (10.2) | |

| Eye | 2 (3.4) | |

| NA | 8 (13.6) | |

| Intensity | Severe | 37 (62.7) |

| Moderate-severe | 2 (3.4) | |

| Moderate | 2 (3.4) | |

| Mild -severe | 1 (1.7) | |

| NA | 17 (28.8) | |

| Chest symptom | Present | 24 (40.7) |

| Absent | 33 (55.9) | |

| NA | 2 (3.4) | |

| Associated symptoms | Nausea | 10 (16.9) |

| Sweating | 7 (11.9) | |

| Vomiting | 5 (8.5) | |

| Dizziness | 2 (3.4) | |

| Miscellaneous | 5 (8.5) | |

| None | 1 (2.0) | |

| NA | 8 (13.5) | |

| ECG | ST elevation | 23 (39.0) |

| ST depression | 9 (15.2) | |

| ST depression in stress | 14 (23.7) | |

| Other changes | 5 (8.5) | |

| Normal | 4 (6.8) | |

| NA | 4 (6.8) | |

| Risk factors | Hypertension | 21 (35.6) |

| Diabetes | 14 (23.7) | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 19 (32.2) | |

| Smoking | 20 (33.9) | |

| Obesity | 4 (6.8) |

Characteristics are shown as number (%) except for age

NA, not available

The vertex in the original description was classified as parietal

Cardiac cephalalgia generally occurs in middle-aged or older individuals (median age, 64 years) with male predominance (62.7%). Forty-seven patients (79.7%) were age 50 or older. Pain is typically triggered by varying degrees of exertion, sexual activity, and motion fluctuation (49.2%) but may develop at rest without any particular trigger (27.1%). Headache may occur suddenly or gradually increase in intensity. The most common location of the pain is the occipital region (39.0%), but it can occur in a variety of sites, most often bilaterally (39.0%).

The nature of the headache varies, which has been described as pulsating, throbbing, oppressive, bursting, or explosive. Regardless, the intensity is usually severe. Headaches are frequently associated with autonomic signs such as nausea, vomiting, and sweating. More than half of patients (55.9%) do not complain of chest symptoms, which makes diagnosis challenging. The reported duration of headache ranges from 30 s to a few days and they may occur intermittently for several years. Exertional headaches are almost always relieved by rest. SAH is suspected in cases of sudden severe headache and several patients underwent diagnostic lumbar puncture [2, 7–9, 24, 33, 39, 44].

ECG revealed ST segment elevation (39.0%), ST segment depression at rest (15.2%) or during stress testing (23.7%), and other abnormal findings (8.5%). ECG was normal or equivocal in four (6.8%). Among the 25 patients who underwent cardiac enzyme testing, the concentration was elevated in 21 patents (84%) and normal in four (16%).

Coronary risk factors were common: hypertension, smoking, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and obesity were reported in 35.6%, 33.9%, 32.2%, 23.7%, and 6.8% of patients, respectively. Three patients, including one reported above, had a history of myocardial infarction or coronary intervention [28, 31]. These histories provide invaluable diagnostic clues.

Underlying cardiac pathology was AMI (50.8%), angina (47.5%), cardiomyopathy (1.7%), and not described (1.7%). CAG results were described in 51 patients. Coronary occlusion or severe stenosis was present in almost all patients. The number of affected arteries was three in 19 patients, two in 11, and one in 17; spasm was reported in two and findings were normal in two others.

PCI was performed in 26 patients and coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) in 12. Nitrates were administered in 15 patients, heparin in one, and warfarin in one. Advanced life support was performed in one patient because of cardiac arrest. Headaches resolved with improvement in myocardial ischemia. Nitroderivatives are effective and PCI or CABG leads to permanent resolution of the headache. Headache recurrence has been reported with restenosis of coronary arteries [21, 43, 46]. Overall, reported outcomes were as follows: headache resolution, 51; death, 6.; not reported, 2. Three patients died of cardiac failure or its complications, including one patient reported above [18, 52]. Two others died of VF [18, 25]. One died suddenly 6 months after headache onset [28]

Discussion

This report presents four cases of cardiac cephalalgia that resulted from AMI. Two patients (cases 2 and 3) reported chest discomfort with associated triggers. In contrast, the other two (cases 1 and 4) presented with sudden severe headache that met the diagnostic criteria for a thunderclap headache without an identifiable trigger. The latter two lost consciousness after the headache and had no cardiac symptoms; therefore, SAH was initially suspected. After head CT confirmed no intracranial hemorrhage, emergency CAG was performed, followed by PCI. Notably, three patients presented with low blood pressure and one developed VF. Because all four exhibited abnormal findings on ECG and echocardiography, the diagnosis of cardiac cephalalgia was straightforward. Early cooperation with cardiologists enabled prompt cardiovascular examination and treatment. The headache resolved after successful coronary reperfusion in all cases.

In a study of 1546 AMI patients, headache was present (along with other symptoms) in 5.2% and was the primary complaint in 3.4% [55]. Differentiation of cardiac cephalalgia from migraine without aura has been emphasized in patients without chest symptoms. Vasoconstrictor medications (e.g., triptans, ergots) are contraindicated in patients with ischemic heart disease, while migraine-like headache may be triggered by angina treatments such as nitroglycerine [3].

The typical manifestation of cardiac cephalalgia is migraine-like pain on exertion. However, it may present as a thunderclap headache without a trigger, although this is not common. In a systemic review of thunderclap headache, more than 100 different causes were reported; cardiac cephalalgia was highlighted as an important causative systemic condition [56]. Above all, SAH is the most common cause of secondary thunderclap headache and should be the focus of initial assessment given its significant morbidity and mortality [57].

Early differentiation of SAH and AMI is crucial because both are potentially life-threatening. Rapid diagnosis and appropriate treatment are therefore critical. Because cardiac cephalalgia is not always associated with chest symptoms or ECG abnormalities, the diagnosis should be considered in middle-aged or older patients with coronary risk factors presenting with a first-episode headache.

Confusingly, SAH patients can also present with cardiac symptoms. ECG abnormalities are common in these patients and left ventricular wall motion abnormalities may develop in the absence of organic coronary artery stenosis. Echocardiography may show takotsubo-like or other types of abnormal wall motion. This manifestation is transient and has been called neurogenic stunned myocardium [58], which is often associated with hypotension and elevated myocardial enzyme concentration [59]. Accordingly, hypotension, ECG abnormalities, abnormal cardiac wall motion, and mildly elevated cardiac enzyme concentration do not preclude SAH. For patients with thunderclap headache, emergency head CT is indispensable; if no significant findings are detected, a cardiac workup should be initiated. ECG, echocardiography, measurement of cardiac enzyme concentrations, and coronary artery evaluation should be performed when cardiac cephalalgia is suspected.

Several mechanisms to explain the headache induced by myocardial ischemia have been hypothesized: 1) referred pain through the convergence of vagal afferents from the heart with trigeminal neurons in the spinal trigeminal nucleus or somatic afferents from C1–C3 in the upper spinothalamic tract [2, 4, 60]; 2) elevated intracranial pressure because of venous stasis resulting from ischemia-induced ventricular hypofunction and reduced cardiac output [2, 4]; 3) vasodilation within the brain secondary to myocardial ischemia-induced release of serotonin, bradykinin, histamine, and substance P [2, 4]; 4) presence of vasospasm in both coronary and cerebral arteries [4]; and 5) reversible contraction of microvessels or cortical spreading depolarization induced by cerebral hypoperfusion [6]. The last hypothesis is based on confirmation of cerebral hypoperfusion during a headache attack in the presence of normal cerebral arteries on MR angiography [6]. CT angiography and MR angiography in the patients reported here did not reveal constriction of visible cerebral arteries either.

Headache in cardiac cephalalgia does not present with uniform clinical characteristics. Some patients visit the outpatient clinic complaining of recurrent exertional headaches, while others are brought to the emergency room in shock or a comatose state. Cardiac symptoms may be absent and ECG may be normal, even with standard stress testing [34]. To diagnose cardiac cephalalgia, clinicians must be aware of it and also suspect its presence. Interestingly, among the 48 articles reporting cardiac cephalalgia, 28 were published in neurology journals and 17 in cardiovascular journals. This may reflect the fact that patients are usually initially seen by neurologists. Overlooked or delayed diagnosis can lead to serious consequences. First-line health care professionals should be aware of cardiac cephalalgia. When it is suspected, early collaboration with cardiologists is warranted.

Conclusion

Cardiac cephalalgia resulting from AMI can present with or without chest discomfort and even mimic the classic thunderclap headache associated with SAH. It should be recognized as an emergency and treated without delay.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Figure 1. PRISMA Flow diagram showing the database search algorithm.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the cardiologists who were involved in the treatments, and Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ICHD-III

International Classification of Headache, Third Edition

- SAH

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

- PCI

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- LAD

Left anterior descending artery

- RCA

Right coronary artery

- ECG

Electrocardiography

- CT

Computed tomography

- CKMB

Creatine kinase–myocardial band

- CAG

Coronary angiography

- AMI

Acute myocardial infarction

- LCX

Left circumflex artery

- VF

Ventricular fibrillation

- MR

Magnetic resonance

- IABP

Intra-aortic balloon pump

- CABG

Coronary artery bypass graft

Authors’ contributions

HK: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, drafting the manuscript. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Osaka Mishima Emergency Critical Care Center. The author certifies that the study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was received from all participants for the publication.

Competing interests

The author declares that there are no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Samuels MA. The brain-heart connection. Circulation. 2007;116(1):77–84. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipton RB, Lowenkopf T, Bajwa ZH, et al. Cardiac cephalgia: a treatable form of exertional headache. Neurology. 1997;49(3):813–816. doi: 10.1212/WNL.49.3.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (2018) 10.6 Cardiac cephalalgia. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. 38(1):145–146. 10.1177/0333102417738202 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Bini A, Evangelista A, Castellini P, et al. Cardiac cephalgia. J Headache Pain. 2009;10(1):3–9. doi: 10.1007/s10194-008-0087-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torres-Yaghi Y, Salerian J, Dougherty C. Cardiac cephalgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2015;19(4):14. doi: 10.1007/s11916-015-0481-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang M, Wang L, Liu C, et al. Cardiac cephalalgia: one case with cortical hypoperfusion in headaches and literature review. J Headache Pain. 2017;18(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s10194-017-0732-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seow VK, Chong CF, Wang TL, et al. Severe explosive headache: a sole presentation of acute myocardial infarction in a young man. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25(2):250–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broner S, Lay C, Newman L, et al. Thunderclap headache as the presenting symptom of myocardial infarction. Headache. 2007;47(5):724–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00795_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalzell JR, Jackson CE, Robertson KE, et al. A case of the heart ruling the head: acute myocardial infarction presenting with thunderclap headache. Resuscitation. 2009;80(5):608–609. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sendovski U, Rabkin Y, Goldshlak L, et al. Should acute myocardial infarction be considered in the differential diagnosis of headache? Eur J Emerg Med. 2009;16(1):1–3. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e3282f5dc09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Austen WG, Edwards JE, Frye RL, et al (1975). A reporting system on patients evaluated for coronary artery disease. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee for Grading of Coronary Artery Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery, American Heart Association. Circulation 51(4 Suppl):5–40. 10.1161/01.cir.51.4.5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caskey WH, Spierings ELH. Headache and heartache. Headache. 1978;18(5):240–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1978.hed1805240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lefkowitz D, Biller J. Bregmatic headache as a manifestation of myocardial ischemia. Arch Neurol. 1982;39:130. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1982.00510140064019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleetcroft R, Maddocks JL. Headache due to ischaemic heart disease. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:676. doi: 10.1177/014107688507800817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blacky RA, Rittelmayer JT, Wallace MR. Headache angina. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60:730. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90394-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vernay D, Deffond D, Fraysse P, et al. Walking headache: an unusual manifestation of ischemic heart disease. Headache. 1989;29:350–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1989.hed2906350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takayanagi K, Fujito T, Morooka S, et al. Headache angina with fatal outcome. Jpn Heart J. 1990;31(4):503–507. doi: 10.1536/ihj.31.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowen J, Oppenheimer G. Headache as a presentation of angina: reproduction of symptoms during angioplasty. Headache. 1993;33:238–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1993.hed3305238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishida A, Sunagawa O, Touma T, et al. Headache as a manifestation of myocardial infarction. Jpn Heart J. 1996;37:261–263. doi: 10.1536/ihj.37.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grace A, Horgan J, Breathnach K, et al. Anginal headache and its basis. Cephalalgia. 1997;17(3):195–196. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1997.1703195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lance JW, Lambros J. Unilateral exertional headache as a symptom of cardiac ischemia. Headache. 1998;38(4):315–316. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1998.3804315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lanza GA, Sciahbasi A, Sestito A, et al. Angina pectoris: a headache. Lancet. 2000;356:998. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02718-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amendo MT, Brown BA, Kossow LB, et al. Headache as the sole presentation of acute myocardial infarction in two elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Cardiol. 2001;10(2):100–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1076-7460.2001.00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Auer J, Berent R, Lassnig E, et al. Headache as a manifestation of fatal myocardial infarction. Neurol Sci. 2001;22:395–397. doi: 10.1007/s100720100071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rambihar VS. Headache angina. Lancet. 2001;357(9249):72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71575-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Famularo G, Polchi S, Tarroni P. Headache as a presenting symptom of acute myocardial infarction. Headache. 2002;42(10):1025–1028. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gutiérrez-Morlote J, Pascual J. Cardiac cephalgia is not necessarily an exertional headache: case report. Cephalalgia. 2002;22(9):765–766. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martínez HR, Rangel-Guerra RA, Cantú-Martínez L, et al. Cardiac headache: hemicranial cephalalgia as the sole manifestation of coronary ischemia. Headache. 2002;42(10):1029–1032. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sathirapanya P. Anginal cephalgia: a serious form of exertional headache. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(3):231–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen SP, Fuh JL, Yu WC, et al (2004) Cardiac cephalalgia. Case report and review of the literature with new ICHD-II criteria revisited. Eur Neurol 51(4): 221–226. 10.1159/000078489 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Gutierrez MJ, Fernandez JM, Timiraos JJ, et al. Cardiac cephalgia: an under diagnosed condition? Rev Esp Cardiol. 2005;58(12):1476–1478. doi: 10.1016/S0300-8932(05)74080-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korantzopoulos P, Karanikis P, Pappa E, et al. Acute non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction presented as occipital headache with impaired level of consciousness–a case report. Angiology. 2005;56(5):627–630. doi: 10.1177/000331970505600516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cutrer FM, Huerter K. Exertional headache and coronary ischemia despite normal electrocardiographic stress testing. Headache. 2006;46(1):165–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00316_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei JH, Wang HF. Cardiac cephalalgia: case reports and review. Cephalalgia. 2008;28(8):892–896. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang WW, Lin CS. Headache angina. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(3):387.e1–e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chatzizisis YS, Saravakos P, Boufidou A, et al. Acute myocardial infarction manifested with headache. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2010;4:148–150. doi: 10.2174/1874192401004010148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng PY, Sy HN, Chen WL, et al. Cardiac cephalalgia presented with a thunderclap headache and an isolated exertional headache: report of 2 cases. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2010;19(1):57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang Y, Jeong D, Jin DG, et al. A case of cardiac cephalalgia showing reversible coronary vasospasm on coronary angiogram. J Clin Neurol. 2010;6(2):99–101. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2010.6.2.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Costopoulos C. Acute coronary syndromes can be a headache. Emerg Med J. 2011;28(1):71–73. doi: 10.1136/emj.2009.082271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elgharably Y, Iliescu C, Sdringola S, et al. Headache: a symptom of acute myocardial infarction. Eur J Cardiovasc Med. 2013;11:170–174. doi: 10.5083/ejcm.20424884.92. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asvestas D, Vlachos K, Salachas A, et al. Headache: an unusual presentation of acute myocardial infraction. World J Cardiol. 2014;6(6):514–516. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v6.i6.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wassef N, Ali AT, Katsanevaki AZ, et al (2014) Cardiac Cephalgia. Cardiol Res 5(6):195–197. 10.14740/cr361w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Mathew PG, Boes CJ, Garza I. A tale of two systems: cardiac cephalalgia vs migrainous thoracalgia. Headache. 2015;55(2):310–312. doi: 10.1111/head.12373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prakash S, Panchani N, Rathore C, et al. Cardiac cephalalgia: first case from India. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2016;19(2):252–254. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.165467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chowdhury AW, Saleh MAD, Hasan P, et al (2015) Cardiac cephalgia: A headache of the heart. J Cardiol Cases 27;11(5):139–141. 10.1016/j.jccase.2015.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Huang CC, Liao PC. Heart attack causes headache - cardiac cephalalgia. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2016;32(2):239–242. doi: 10.6515/acs20150628a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shankar A, Allan CL, Smyth D, et al. Cardiac cephalgia: a diagnostic headache. Intern Med J. 2016;46:1219–1221. doi: 10.1111/imj.13217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Majumder B, Chatterjee PK, Sudeep KN, et al. Cardiac cephalgia presenting as acute coronary syndrome: A case report and review of literature. Nig J Cardiol. 2017;14:119–121. doi: 10.4103/njc.njc_16_17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lazari J, Money-Kyrle A, Wakerley BR. Cardiac cephalalgia: severe, non-exertional headache presenting as unstable angina. Pract Neurol. 2019;19(2):173–175. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2018-002045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.MacIsaac R, Jarvis S, Busche K. A Case of a Cardiac Cephalgia. Can J Neurol Sci. 2019;46(1):124–126. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2018.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Santos PSF, Pedro MKF, Andrade AC (2019) Cardiac cephalalgia: A deadly case report. Headache Medicine 10:32–34. 10.48208/HeadacheMed.2019.8

- 53.Ruiz Ortiz M, Bermejo Guerrero L, Martínez Porqueras R, et al. Cardiac cephalgia: When myocardial ischaemia reaches the neurologist's consultation. Neurologia (Engl Ed) 2020;35(8):614–615. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2019.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun L, Zhang Q, Li N, et al. Cardiac cephalalgia closely associated with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;47:350.e1–350.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Culić V, Mirić D, Eterović D(2001). Correlation between symptomatology and site of acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 77(2–3):163–168. 10.1016/s0167-5273(00)00414-9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Devenney E, Neale H, Forbes RB. A systematic review of causes of sudden and severe headache (Thunderclap Headache): should lists be evidence based? J Headache Pain. 2014;15(1):49. doi: 10.1186/1129-2377-15-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schwedt TJ, Matharu MS, Dodick DW. Thunderclap headache. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:621–631. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70497-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kono T, Morita H, Kuroiwa T, et al. Left ventricular wall motion abnormalities in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage: neurogenic stunned myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24(3):636–639. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mayer SA, LiMandri G, Homma S, et al. Electrocardiographic markers of abnormal left ventricular wall motion in acute subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1995;83(5):889–896. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.83.5.0889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meller ST, Gebhart GF. A critical review of the afferent pathways and the potential chemical mediators involved in cardiac pain. Neuroscience. 1992;48(3):501–524. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90398-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary Figure 1. PRISMA Flow diagram showing the database search algorithm.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.