Abstract

Background:

Widespread inappropriate antibiotic prescribing is a major driver of resistance. Little is known about antifungal prescribing practices in the United States, which is concerning given emerging resistance in fungi, particularly to azole antifungal agents.

Objective:

We analyzed outpatient antifungal prescribing data in the United States to inform stewardship efforts.

Design:

Descriptive analysis of outpatient antifungal prescriptions dispensed during 2018 in the IQVIA Xponent database.

Methods:

Prescriptions were summarized by drug, sex, age, geography, and healthcare provider specialty. Census denominators were used to calculate prescribing rates among demographic groups.

Results:

Healthcare providers prescribed 22.4 million antifungal courses in 2018 (68 prescriptions per 1,000 persons). Fluconazole was the most commonly prescribed drug (75%), followed by terbinafine (11%) and nystatin (10%). Prescription rates were higher among females versus males (110 vs 25 per 1,000 population) and adults versus children (82 vs 27 per 1,000 population). Prescription rates were highest in the South (81 per 1,000 population) and lowest in the West (48 per 1,000 population). Nurse practitioners and family practitioners prescribed the most antifungals (43% of all prescriptions), but the highest prescribing rates were among obstetrician-gynecologists (84 per provider).

Conclusions:

Prescribing antifungal drugs in the outpatient setting is common, with enough courses dispensed for 1 in every 15 US residents in 2018. Fluconazole use patterns suggest vulvovaginal candidiasis as a common indication. Regional prescribing differences could reflect inappropriate use or variations in disease burden. Further study of higher antifungal use in the South could help target antifungal stewardship practices.

Antibiotic resistance is a serious health problem in the United States. Infections with drug-resistant fungi are a major concern; this includes Candida spp, which are becoming increasingly common, and azole-resistant Aspergillus infections, which are still relatively rare in the United States but represent a potentially growing threat given the widespread use of azoles. 1 Reasons for the emergence of antifungal resistance are multifactorial and likely related to antibiotic and antifungal use in humans and environmental fungicides. 2 Antifungal stewardship is critical because systemic antifungal drug options are limited to only 3 major classes (in addition to terbinafine and griseofulvin, which are not effective against invasive infections), and many of these drugs are expensive and are associated with notable side effects and drug interactions. 3

Measuring antifungal use is an important initial step in understanding resistance and developing strategies to combat it. Fungal infections vary widely in severity, so antifungal use occurs across many different patient-care settings. Previous analyses have shown that fluconazole accounts for a large proportion of total inpatient antifungal use but that recent declines in its use, combined with increased total antifungal drug costs in community care settings, may indicate a shift toward greater outpatient antifungal use. 3–5 However, little information is available regarding outpatient antifungal use patterns in the United States. We aimed to describe these patterns to help further inform antifungal stewardship efforts.

Methods

All antifungal prescriptions dispensed in the United States during 2018 were extracted from the IQVIA Xponent database. IQVIA captures 92% of all retail prescriptions and uses a patented method to project to 100% coverage of all prescription activity based on a comprehensive sample of deidentified prescription transactions, collected from pharmacies that report to IQVIA weekly. 6 These data represent all retail antifungal prescriptions, across all payers, including community pharmacies and food store pharmacies. The projection method standardizes the data into estimated prescription counts and uses geospatial methods to align the estimated prescriptions for the nonsample pharmacies to prescribers with observed prescribing behaviors for the same product in nearby sample pharmacies. Confidence intervals are not provided because of the high prescription capture rate and fidelity of the projection process.

We grouped antifungal drugs into 5 categories based on the Uniform Classification System 7 and whether the drug is systemic versus nonsystemic (Table 3). Using Vintage 2018 US Census bridged-race population estimates, we summarized prescription counts and calculated rates per 1,000 population by drug, sex, age group (<20 vs ≥20 years), US Census region, and state where the provider was located. 8 We also summarized prescriptions by provider specialty based on the American Medical Association self-designated practice specialties, and we used the total number of providers in each specialty from the IQVIA database to calculate specialty-specific rates.

Table 3.

Antifungal Drug Type, Category, and Route of Administration

| Category | Antifungal Drugs |

Route of Administration |

|---|---|---|

| Systemic | ||

| Allylamines | Terbinafine | Oral |

| Echinocandins | Anidulafungin | IV |

| Caspofungin | ||

| Micafungin | ||

| Fluorinated pyrimidines | Flucytosine | Oral |

| Griseofulvin | Griseofulvin | Oral |

| Imidazoles | Ketoconazole | Oral |

| Polyenes | Amphotericin B | IV |

| Triazoles | Fluconazole | IV and oral |

| Isavuconazonium | ||

| sulfate | ||

| Itraconazole | ||

| Posaconazole | ||

| Voriconazole | ||

| Nonsystemic | ||

| Imidazoles | Miconazole | Oropharyngeal |

| Polyenes | Nystatin | Oropharyngeal |

Results

Healthcare providers prescribed 22.4 million courses of outpatient antifungals dispensed in US pharmacies in 2018 (68 prescriptions per 1,000 persons) (Table 1). Fluconazole was prescribed most frequently (51 prescriptions per 1,000 persons) and accounted for 75% of all antifungal prescriptions, followed by terbinafine (11%) and nystatin (10%). The remaining antifungals together accounted for 3.5% of all prescriptions, including griseofulvin (1.4%), ketoconazole (1%), itraconazole (0.6%), and voriconazole (0.3%).

Table 1.

Outpatient Antifungal Prescriptions by Age Group, Sex, and Region, United States, 2018

| Antifungal Category and Drug | Overall | Age Group b | Sex b | Region | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Prescriptions | % a | Rate per 1,000 Persons | <20 | ≥20 | Male | Female | Midwest | Northeast | South | West | |

| Azoles | 17,208,686 | 76.9 | 52.6 | 13.3 | 65.7 | 10.8 | 93.0 | 52.4 | 52.4 | 63.7 | 35.2 |

| Fluconazole | 16,749,502 | 74.8 | 51.2 | 12.2 | 64.2 | 9.3 | 91.8 | 50.9 | 51.0 | 62.3 | 33.9 |

| Itraconazole | 140,998 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Voriconazole | 58,668 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.08 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Ketoconazole | 219,917 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| Posaconazole | 29,115 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.07 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.06 | 0.1 |

| Isavuconazonium sulfate | 10,486 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.0 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Echinocandinsc | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Micafungin | 95 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Caspofungin | 5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Polyenes | 1,788 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.0 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.0 |

| Amphotericin B | 1,788 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.0 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.0 |

| Other antifungals | 2,873,751 | 12.8 | 8.8 | 4.9 | 10.1 | 9.4 | 8.2 | 8.6 | 8.0 | 9.8 | 7.9 |

| Flucytosine | 700 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Terbinafine | 2,559,484 | 11.4 | 7.8 | 1.8 | 9.8 | 8.2 | 7.4 | 7.8 | 7.1 | 8.4 | 7.5 |

| Griseofulvin | 313,567 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.4 |

| Non-systemic antifungals | 2,298,386 | 10.3 | 7.0 | 8.6 | 6.5 | 5.2 | 8.8 | 7.7 | 7.2 | 7.9 | 4.9 |

| Miconazole | 687 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Nystatin | 2,297,596 | 10.3 | 7.0 | 8.6 | 6.5 | 5.2 | 8.8 | 7.7 | 7.2 | 7.9 | 4.9 |

| Diphenhydramine\lidocaine\nystatin | 103 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 22,382,711 | 100 | 68.4 | 26.8 | 82.2 | 25.4 | 110.0 | 68.6 | 67.6 | 81.4 | 47.9 |

May not add to 100 due to rounding.

0.1% of observations were missing age or sex data.

No outpatient anidulafungin use was reported.

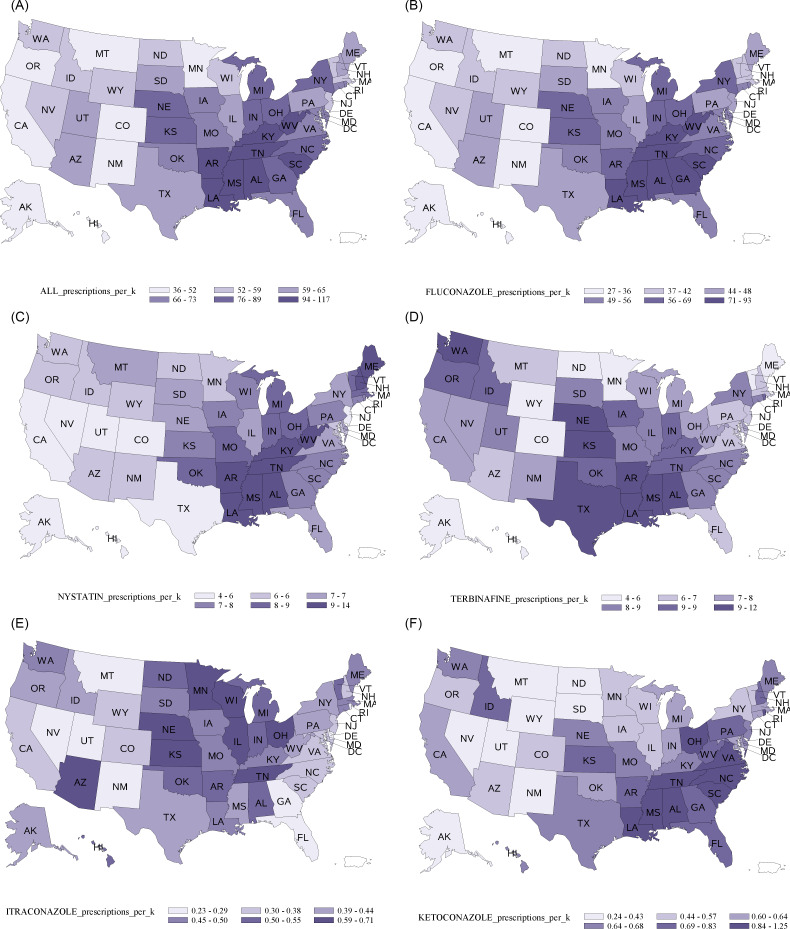

Females were prescribed antifungals at a rate >4 times greater than males (110 vs 25 per 1,000 population), largely due to differences in fluconazole (92 prescriptions per 1,000 females vs 9.3 per 1,000 males); other antifungals were prescribed similarly by sex. Fluconazole was prescribed more commonly to adults aged >20 years than people <20 years (64 vs 12 per 1,000 population), as was terbinafine (9.8 vs 1.8 per 1,000 population). However, people <20 years had higher rates of nystatin (8.6 vs. 6.5 per 1,000 population) and griseofulvin (3.1 vs. 0.2 per 1,000 population). Overall, antifungal prescription rates were highest in the South (81 per 1,000) and were lowest in the West (48 per 1,000 population). This pattern was consistent across antifungal categories and specifically for fluconazole, terbinafine, and nystatin (ie, the most commonly prescribed drugs); however, itraconazole was more commonly prescribed in the Midwest (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Outpatient prescriptions by state for (A) all antifungals, (B) fluconazole, (C) nystatin, (D) terbinafine, (E) itraconazole, and (F) ketoconazole, United States, 2018.

Nurse practitioners wrote the most antifungal prescriptions (4.9 million), followed by family practice practitioners (4.7 million) and obstetricians/gynecologists (OB/GYNs, 3.1 million). The highest prescribing rates were among OB/GYNs (84 prescriptions per provider) and dermatologists (56 prescriptions per provider) (Table 2). Specifically, fluconazole prescribing rates were highest among OB/GYNs (83 prescriptions per provider), and terbinafine prescribing rates were highest among dermatologists (22 prescriptions per provider). Ketoconazole prescribing rates were highest among dermatologists (2.2 prescriptions per provider) and family practice practitioners (0.6 prescriptions per provider).

Table 2.

Outpatient Antifungal Prescriptions by Provider Specialty for All Antifungals Combined and for Fluconazole, Terbinafine, and Ketoconazole, 2018

| Provider Specialty a | All Antifungals | Fluconazole | Terbinafine | Ketoconazole | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Providers | No. of Prescriptions (%) b | Prescription Rate per Provider | No. of Prescriptions (%) b | Prescription Rate Per Provider | No. of Prescriptions (%) b | Prescription Rate Per Provider | No. of Prescriptions (%) b | Prescription rate per provider | |

| OB/Gyn | 37,590 | 3,143,280 (14.0) | 83.6 | 3,109,695 (18.6) | 82.7 | 7,512 (0.3) | 0.2 | 4,724 (2.1) | 0.1 |

| Dermatology | 11,329 | 638,056 (2.9) | 56.3 | 318,443 (1.9) | 28.1 | 247,905 (9.7) | 21.9 | 24,468 (11.1) | 2.2 |

| Family practice | 96,073 | 4,705,793 (21.0) | 49.0 | 3,383,614 (20.2) | 35.2 | 762,994 (29.8) | 7.9 | 57,086 (26.0) | 0.6 |

| Nurse practitioner | 109,741 | 4,921,506 (22) | 44.8 | 4,086,482 (24.4) | 37.2 | 279,273 (10.9) | 2.5 | 19,152 (8.7) | 0.2 |

| Physician assistants | 63,467 | 2,238,867 (10) | 35.3 | 1,758,741 (10.5) | 27.7 | 226,531 (8.9) | 3.6 | 16,226 (7.4) | 0.3 |

| Internal Medicine/Pediatrics | 3,329 | 111,861 (0.5) | 33.6 | 76,428 (0.5) | 23.0 | 15,458 (0.6) | 4.6 | 678 (0.3) | 0.2 |

| Infectious diseases | 6,166 | 179,919 (0.8) | 29.2 | 123,148 (0.7) | 20.0 | 9,855 (0.4) | 1.6 | 508 (0.2) | 0.1 |

| Internal medicine | 83,841 | 2,081,644 (9.3) | 24.8 | 1,488,002 (8.9) | 17.7 | 300,487 (11.7) | 3.6 | 20,529 (9.3) | 0.2 |

| Otolaryngology | 9,536 | 190,957 (0.9) | 20.0 | 119,196 (0.7) | 12.5 | 829 (0) | 0.1 | 636 (0.3) | 0.1 |

| Pediatrics | 54,228 | 862,586 (3.9) | 15.9 | 308,564 (1.8) | 5.7 | 35,394 (1.4) | 0.7 | 3,608 (1.6) | 0.1 |

| Urology | 10,131 | 136,284 (0.6) | 13.5 | 131,536 (0.8) | 13 | 783 (0) | 0.1 | 682 (0.3) | 0.1 |

| Emergency medicine | 32,346 | 390,027 (1.7) | 12.1 | 324,601 (1.9) | 10.0 | 11,680 (0.5) | 0.4 | 1,941 (0.9) | 0.1 |

| Medical subspecialty | 74,424 | 665,330 (3.0) | 8.9 | 460,053 (2.7) | 6.2 | 21,045 (0.8) | 0.3 | 7,518 (3.4) | 0.1 |

| Pediatric subspecialty | 8,273 | 30,849 (0.1) | 3.7 | 15,831 (0.1) | 1.9 | 877 (0.0) | 0.1 | 259 (0.1) | 0.0 |

| Surgery | 69,536 | 237,433 (1.1) | 3.4 | 189,898 (1.1) | 2.7 | 9,585 (0.4) | 0.1 | 1,579 (0.7) | 0.0 |

| Dentistry | 122,706 | 281,462 (1.3) | 2.3 | 190,332 (1.1) | 1.6 | 1,571 (0.1) | 0.0 | 898 (0.4) | 0.0 |

| Other | 113,783 | 1,194,244 (5.3) | 10.5 | 388,847 (2.3) | 3.4 | 596,576 (23.3) | 5.2 | 52,772 (24.0) | 0.5 |

| All providers | 911,814 | 22,382,711 (100.0) | 24.5 | 16,749,502 (100.0) | 18.4 | 2,559,484 (100.0) | 2.8 | 219,917 (100.0) | 0.2 |

5,315 providers had missing specialty data.

May not add to 100% due to rounding.

Discussion

This study provides a baseline description of outpatient antifungal use in the United States in 2018, a preliminary step in better understanding where to focus stewardship efforts. Prescriptions for outpatient antifungal drugs were common, with enough courses dispensed for 1 in every 15 residents. Specifically, fluconazole prescribing patterns likely reflect the large public health burden of vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) given that OB/GYNs had the highest prescribing rate and females were prescribed fluconazole at a rate 10-fold higher than males. Regional differences in use of azoles and other common antifungal drugs is probably multifactorial and could reflect differences in antifungal prescribing practices, antibiotic prescribing, and fungal disease geography, among other factors. Overall, these results provide a foundation for further studies to understand antifungal prescribing, including what portion may be inappropriate, which will ultimately help inform explore antifungal stewardship strategies and prevent the continued spread of antifungal resistance.

We observed a total outpatient antifungal use rate (68 per 1,000 persons) at an order of magnitude lower than that of antibacterial medications (791 per 1,000 persons in 2018). 9 Although the volume of antifungal prescribing is substantially lower than that of antibiotics, for which stewardship interventions are more common, large regional variations in antifungal prescribing suggest that antifungal stewardship may also be warranted. Because these data do not allow for evaluation of appropriateness, further study of antifungal prescribing practices is needed to inform interventions. Additionally, the burden of fungal infections relative to other types of infections is not well characterized but is likely far greater than is currently appreciated given the challenges with under diagnosis and lack of comprehensive public health surveillance. 10 Still, outpatient antifungal use appeared to be common, and this analysis captured only a portion of total US antifungal drug use. For example, many serious invasive fungal infections are both acquired and treated in the inpatient setting (often in intensive care), and approximately half of total antifungal expenditures nationwide attributable to hospitals. 3,5 Furthermore, over-the-counter (OTC) treatments for superficial infections and VVC are readily available and are used extensively but are not captured in this analysis. 11 The specific contributions of inpatient, outpatient, and OTC antifungal use to the spread of antifungal resistance are unclear. These concerns are compounded by the reality that there are only 3 primary classes of antifungal drugs used for fungal infections; thus, resistance to one class may render drugs used across settings ineffective.

Although the IQVIA database does not contain information on prescription indications, prescribing of fluconazole by OB/GYNs to adult women appears to reflect treatment for VVC, a common condition estimated to affect up to 75% of women. 12 This area should be further evaluated for antifungal stewardship efforts because self-diagnosis and empiric diagnosis of VVC are frequently incorrect, leading to inappropriate treatment. Topical OTC agents or single-dose oral fluconazole are recommended for mild-to-moderate infections, whereas severe or recurrent VVC requires treatment with longer courses of fluconazole or other antifungals for azole-resistant infections, which are frequently caused by non-albicans species and are a growing public health problem. 13–15 Higher fluconazole prescriptions per provider among nurse practitioners (n = 37), family practice physicians (n = 35), and physician assistants (n = 28) compared with internal medicine physicians (n = 18), may reflect differences in prescribing for VVC, as well as differences in patient populations and care settings, and warrants further investigation.

Terbinafine, primarily in people aged >20 years, and griseofulvin, primarily in people <20 years, were the most commonly prescribed medications typically used for skin and nail infections, although some nystatin and itraconazole use may reflect such treatment. Ketoconazole was the fifth most commonly prescribed antifungal, which is concerning given that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warns that its use is associated with multiple severe adverse effects, including liver failure, and the FDA recommends that it be reserved for serious fungal infections for which no other treatment is available. 16 More than 200,000 prescriptions were dispensed for ketoconazole in 2018, which suggests that it continues to be widely prescribed for skin and nail infections, despite the FDA warning. Messaging targeting dermatologists and family practitioners may be warranted, given high prescribing rates.

Geographic variability in outpatient antifungal prescriptions was even greater than that reported for antibacterial use, with the South US Census region having an antifungal prescription rate 70% higher than the West region versus 31% for antibacterials. 17 Differential antifungal prescribing by region could be related to differences in prescribing practices, disease burden, or both, similar to inpatient antifungal use, likely influenced by differences in overall health status and social health determinants. 3,17 Additionally, antibacterial use, an established risk factor for VVC and other forms of candidiasis, might partly explain the higher fluconazole use rates in the South. Higher rates of ketoconazole prescriptions in the South versus other regions (0.8 vs 0.6 per 1,000 population) support inappropriate prescribing as a driver of regional differences. Higher rates of itraconazole use in the Midwest compared with other areas is consistent with the geographic distribution of histoplasmosis and blastomycosis and could reflect treatment for these diseases.

In addition to the lack of indication information, another limitation of this analysis is the prescription-based (rather than patient-based) nature of the data, which could lead to overestimates of drugs requiring prolonged use. For example, onychomycosis, which can require 3 months of treatment with drugs like terbinafine, 18 was commonly prescribed in this study.

Future work to characterize total US antifungal use, including inpatient and outpatient prescriptions and indication information, dose and duration, OTC treatment, and environmental fungicides, will help distinguish appropriate prescribing practices from inappropriate ones and help further target antifungal stewardship strategies.

Acknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Published 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/threats-report/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2021.

- 2. Toda M, Beer KD, Kuivila KM, Chiller TM, Jackson BR. Trends in agricultural triazole fungicide use in the United States, 1992–2016 and possible implications for antifungal-resistant fungi in human disease. Environ Health Perspect 2021;129:55001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vallabhaneni S, Baggs J, Tsay S, Srinivasan AR, Jernigan JA, Jackson BR. Trends in antifungal use in US hospitals, 2006–12. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018;73:2867–2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stultz JS, Kohinke R, Pakyz AL. Variability in antifungal utilization among neonatal, pediatric, and adult inpatients in academic medical centers throughout the United States of America. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18:501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fitzpatrick MA, Suda KJ, Evans CT, Hunkler RJ, Weaver F, Schumock GT. Influence of drug class and healthcare setting on systemic antifungal expenditures in the United States, 2005–15. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 2017;74:1076–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. King LM, Bartoces M, Fleming-Dutra KE, Roberts RM, Hicks LA. Changes in US outpatient antibiotic prescriptions from 2011–2016. Clin Infect Dis 2020;70:370–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/community/pdfs/Uniform-System-of-Classification-2018-p.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed February 26, 2021.

- 8. Bridged-race population estimates, 1990–2018. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://wonder.cdc.gov/bridged-race-v2018.html. Published 2018. Accessed January 9, 2020.

- 9. Outpatient antibiotic prescriptions—United States, 2018. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/data/report-2018.html. Published 2018. Accessed July 78, 2021,

- 10. Burden of fungal diseases in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/cdc-and-fungal/burden.html. Accessed December 8, 2020.

- 11. Harrington P, Shepherd MD. Analysis of the movement of prescription drugs to over-the-counter status. J Managed Care Pharm 2002;8:499–5011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rathod SD, Buffler PA. Highly-cited estimates of the cumulative incidence and recurrence of vulvovaginal candidiasis are inadequately documented. BMC Women’s Health 2014;14:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vulvovaginal candidiasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/candidiasis.htm. Published 2021. Accessed October 18, 2021.

- 14. Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2015;62(4):e1–e50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Makanjuola O, Bongomin F, Fayemiwo SA. An update on the roles of non-albicans Candida species in vulvovaginitis. J Fungi (Basel) 2018;4:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns that prescribing of nizoral (ketoconazole) oral tablets for unapproved uses including skin and nail infections continues; linked to patient death. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-warns-prescribing-nizoral-ketoconazole-oral-tablets-unapproved. Accessed October 4, 2021.

- 17. Fleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, et al. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among US ambulatory care visits, 2010–2011. JAMA 2016;315:1864–1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: treatment and prevention of recurrence. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;80:853–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]