Abstract

Objective

In a cohort assembled during the height of mortality-associated coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in New York City, the objectives of this qualitative-quantitative mixed-methods study were to assess COVID-related stress at enrollment with subsequent stress and clinical and behavioral characteristics associated with successful coping during longitudinal follow-up.

Methods

Patients with rheumatologist-diagnosed rheumatic disease taking immunosuppressive medications were interviewed in April 2020 and were asked open-ended questions about the impact of COVID-19 on psychological well-being. Stress-related responses were grouped into categories. Patients were interviewed again in January–March 2021 and asked about interval and current disease status and how well they believed they coped. Patients also completed the 29-item Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS-29) measuring physical and emotional health during both interviews.

Results

Ninety-six patients had follow-ups; 83% were women, and mean age was 50 years. Patients who reported stress at enrollment had improved PROMIS-29 scores, particularly for the anxiety subscale. At the follow-up, patients reported persistent and new stresses as well as numerous self-identified coping strategies. Overall coping was rated as very well (30%), well (48%), and neutral-fair-poor (22%). Based on ordinal logistic regression, variables associated with worse overall coping were worse enrollment–to–follow-up PROMIS-29 anxiety (odds ratio [OR], 4.4; confidence interval [CI], 1.1–17.3; p = 0.03), not reporting excellent/very good disease status at follow-up (OR, 2.7; CI, 1.1–6.5; p = 0.03), pandemic-related persistent stress (OR, 5.7; CI, 1.6–20.1; p = 0.007), and pandemic-related adverse long-lasting effects on employment (OR, 6.1; CI, 1.9–20.0; p = 0.003) and health (OR, 3.0; CI, 1.0–9.0; p = 0.05).

Conclusions

Our study reflects the evolving nature of COVID-related psychological stress and coping, with most patients reporting they coped well. For those not coping well, multidisciplinary health care providers are needed to address long-lasting pandemic-associated adverse consequences.

Key Words: COVID-19, anxiety, coping strategies, psychological stress, qualitative-quantitative

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has markedly impacted physical and emotional health in patients with rheumatic diseases.1–4 In addition to effects on symptoms, flares, and medications, the pandemic has affected livelihoods, lifestyles, and psychological health.3 Much of the collective impact has been rooted in negative psychological stress (i.e., emotional or mental tension)5 and response to stress.6

For some patients, initial stresses of COVID-19 were tempered as the pandemic evolved. As more knowledge and therapeutic options became available, some initial stresses improved, and although new stresses emerged, the overall cadence was toward less stress.6 This trajectory was enhanced by implementing individualized successful coping strategies (i.e., cognitive or behavioral efforts that diminish psychological stress).6–8

For other patients, however, initial stresses persisted, and new stresses added to the load. These stresses may have resulted from permanent consequences to health and livelihood for patients and their families, including serious severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and death.3 In addition, coping strategies may have been insufficient or misguided. Targeted health care and effective health care obviously were, and continue to be, needed by these patients.

We previously assembled a cohort of patients at the height of COVID-19 mortality in New York City (NYC) in April 2020 to ascertain the impact of SARS-CoV-2 on patient-reported rheumatic disease symptoms, medications, and perceived risks of disease.9–11 We also measured emotional stress attributed to the pandemic and its impact on physical and mental well-being.12 In a follow-up study approximately 10 months later, which coincided with the advent of vaccines for patients with chronic diseases, we assessed patients' concerns about vaccines and found that variables identified at enrollment, particularly age, race, and diagnosis, were associated with attitudes toward vaccination.13 It is not known whether these and other variables identified at the start of the pandemic impacted subsequent coping and physical and emotional well-being as the pandemic unfolded. Given the potential for stress to exacerbate rheumatic disease,14 knowing patients' perspectives on current COVID-19 stresses and types of effective and ineffective coping would help clinicians target interventions aimed at ameliorating ongoing COVID-related stresses.

The objectives of this longitudinal study were to assess relationships between previously measured stress with current stress, physical health, and emotional well-being and to identify demographic, disease, and behavioral characteristics associated with coping successfully with COVID-related stress. We hypothesized that more active rheumatic disease and irreversible consequences of the pandemic, such as specific job loss, would be associated with worse coping.

METHODS

This was a follow-up assessment of patients enrolled in a mixed qualitative-quantitative study conducted during the first wave of COVID-19 in NYC, specifically at the height of mortality due to SARS-CoV-2.9–12 The enrollment and follow-up assessments were conducted by telephone, and all patients provided verbal consent. This study was approved by the institutional review board at Hospital for Special Surgery.

Given the rapidity of information dissemination about COVID-19, we purposefully enrolled patients during a narrow time period in order to achieve a relatively uniform informational background. Specifically, enrollment started while the death rate from COVID-19 showed continuous increase and ended when this rate showed several consecutive days of decrease. Patients were recruited from 13 rheumatology practices chosen because they have high volumes of patients who have different diagnoses and who come from different socioeconomic groups. Patients were eligible if they had a rheumatologist-diagnosed rheumatic disease, were taking immune-modulating medications, and were English-speaking. Patients were identified by reviewing daily telehealth appointment schedules or by direct referral by their rheumatologist. Patients were contacted by telephone and interviewed simultaneously by 2 investigators with open-ended questions addressing perceived risk of infection, plans to alter medications, physical function, and emotional well-being. Patient-volunteered responses were then evaluated with qualitative methods, described below. Patients also completed standard surveys, including the 29-item Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS-29), composed of 8 subscales (physical function, anxiety, depression, fatigue, sleep disturbance, social function, pain interference, and cognitive function) with results reported as T scores.15,16 For each subscale, a score of 50 corresponds to the general population, and higher values represent more of the attribute being measured. A 5-point difference is considered a minimum clinically important difference.

The time of the follow-up was selected to coincide with the initiation of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines for patients with chronic conditions and the release of the American College of Rheumatology guidelines recommending vaccination for patients with rheumatic diseases.17 At the follow-up, patients again were interviewed simultaneously by 2 investigators and were asked about rheumatic disease activity during the pandemic with response options of typical, more active, less active, and unpredictable. They were asked about changes in medications, infection with SARS-CoV-2, and their opinions about newly available vaccines. Patients also were asked “What emotional stresses did you experience during the pandemic” and “How did you deal or cope with these stresses?” Patients could volunteer as many responses to these open-ended questions as they wished. Patients also were asked to rate how well they believe they coped psychologically during the pandemic, with response options of very well, well, neutral, fair, and poor, and to rate their current disease status as excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. At the conclusion of the interview, patients again completed the PROMIS-29 to reflect their current condition. The 2 interviewers then conferred to ensure comprehensive and congruent qualitative and quantitative data.

Data Analysis

Enrollment open-ended responses were reviewed according to grounded theory and analyzed according to a descriptive strategy.18,19 Using open coding, the investigators who conducted the interviews iteratively and independently reviewed each patient's responses line-by-line to generate concepts and then overarching categories. Based on a comparative analytic strategy, categories were refined to ensure they compassed distinct features and then were named to capture the phenomena they represented.18 Additional investigators experienced in qualitative methods reviewed all responses and corroborated the categories.20 Several categories pertained to COVID-related stress, such as high exposure to the virus at work, conflicting COVID-19 information, increased family responsibilities, disruption to finances and employment, and changing rheumatic disease medications.

For the current analysis, follow-up open-ended responses to questions about types of stress and coping were analyzed with the same descriptive qualitative approach. Data saturation, that is, when no new concepts were volunteered, was achieved. Categories of ongoing and current stress and coping strategies were identified and named with descriptive terms. A database was then created with applicable categories assigned for each patient, and frequencies of each category were calculated.

T scores were calculated for enrollment and follow-up PROMIS-29 subscales, and within-patient differences in scores (i.e., follow-up minus enrollment scores) were calculated and compared with paired t tests. Larger differences indicate better physical function, social function, and cognitive function, but worse anxiety, depression, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and pain interference. Also, for each subscale, mean within-patient differences in PROMIS-29 scores were compared between patients who did and did not report COVID-related stress at enrollment using t tests.

Frequencies of ranked responses for questions about rheumatic disease activity during the pandemic, current disease status, and overall coping were calculated. A 3-level variable was defined (i.e., “overall coping”) corresponding to responses of very well, well, and neutral-fair-poor (the last group was a composite of patients who were not coping satisfactorily). Overall coping was then compared with demographic and clinical variables, including age, diagnosis, medications, disease activity during the pandemic, current disease status, within-patient differences in PROMIS-29 scores, and categories of stress and coping discerned from the follow-up qualitative analysis. Variables associated with p ≤ 0.05 were entered in an ordinal logistic regression model with the 3 overall-coping groups as the dependent variable. After backward stepwise elimination, variables with p ≤ 0.05 were retained in the final model. A constant odds ratio (OR) across the 3 levels of the response variable was verified by ensuring the score test for the proportional odds assumption was satisfied. All analyses were performed using SAS v9.0.

RESULTS

Patients were enrolled between April 2 and April 21, 2020, and follow-ups were conducted between January 12 and March 3, 2021. The mean interval between enrollment and follow-up was 10 months (range, 9–11 months). Of the 112 patients enrolled, 96 participated in the follow-up (86%), 7 agreed to participate but were unavailable for an interview during the designated period, 7 were not contacted, and 2 refused (one was displeased with medical care and another was overwhelmed with her husband's cancer diagnosis). There were no differences between those who did and did not participate in the follow-up with respect to age, sex, diagnosis, rheumatic disease medications, and PROMIS-29 scores (p ≥ 0.05 for all comparisons). There also was no difference in the frequency of volunteering COVID-related stress at enrollment.

The mean age of the 96 participants was 50 years, 83% were women, 8% were Asian, 10% were Black, 82% were White, and an additional 13% were Latino ethnicity (Table 1). The 96 patients had diverse diagnoses, including 28% with lupus and 27% with rheumatoid arthritis, and 41% were taking both conventional and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Sixty-seven patients reported they were tested for SARS-CoV-2; 9 had a positive test, 8 had symptoms, and 1 was hospitalized and discharged after several days. Most patients reported their rheumatic disease was typical (36%) or less active (24%) during the pandemic, whereas others reported it was more active (31%) or unpredictable (9%). Disease status at follow-up was rated as excellent or very good (32%), good (41%), or fair-poor (27%). Overall success in coping emotionally during the pandemic was rated as very well (30%), well (48%), and neutral-fair-poor (22%).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics at Enrollment and Follow-up

| Variables | p value |

|---|---|

| Enrollment | |

| Age, mean (range), y | 50 (22–87) |

| Women | 83% |

| Race | |

| Asian | 8% |

| Black | 10% |

| White | 82% |

| Latino | 13% |

| Diagnosis | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) | 28% |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) | 27% |

| Undifferentiated connective tissue disorder (UCTD) | 8% |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 8% |

| Sjögren syndrome | 4% |

| Mixed connective tissue disorder | 3% |

| Othera | 22% |

| Medications for rheumatic diseaseb | |

| Conventional DMARDs | 84% |

| Biologic DMARDs | 55% |

| Follow-up | |

| Rheumatic disease activity during pandemic | |

| Typical | 36% |

| More active | 31% |

| Less active | 24% |

| Unpredictable | 9% |

| Current status of rheumatic disease | |

| Excellent | 10% |

| Very good | 22% |

| Good | 41% |

| Fair | 21% |

| Poor | 6% |

| How well coped psychologically during pandemic | |

| Very well | 30% |

| Well | 48% |

| Neutral | 15% |

| Fair | 4% |

| Poor | 3% |

a Spondyloarthritis 2%, SLE/UCTD overlap 2%, Sjögren/RA overlap 2%, polymyalgia rheumatica 2%, antiphospholipid syndrome/SLE 2%, ankylosing spondylitis 2%, granulomatosis with polyangiitis 1%, RA/SLE overlap 1%, RA/polymyalgia rheumatica overlap 1%, inflammatory polyarthralgia 1%, small vessel vasculitis 1%, scleroderma 1%, Churg-Strauss syndrome 1%, Still's disease 1%, atypical polyarteritis nodosa 1%, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis 1%.

b Forty-one percent taking both conventional and biologic DMARDs.

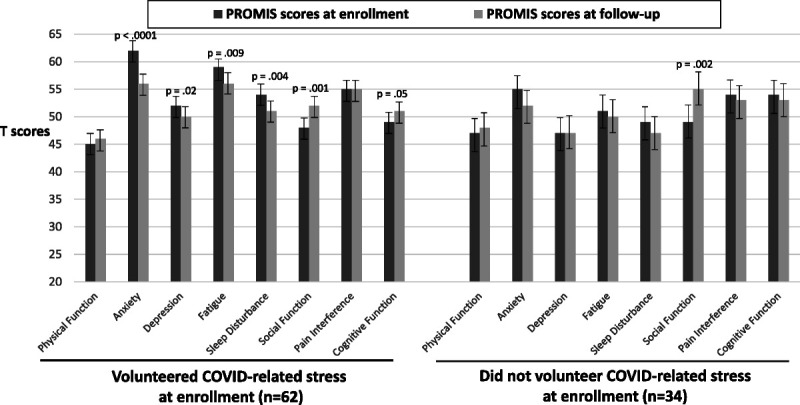

At enrollment, 62 patients volunteered COVID-related stress, and 34 patients did not volunteer COVID-related stress. For the 62 who volunteered stress, mean PROMIS-29 scores at enrollment deviated more from (i.e., were worse than) the population norm of 50, and at follow-up, their scores more closely approached the norm (i.e., improved) for most subscales (Fig. 1). The within-patient improvement in scores met the criterion for a clinically important difference for the anxiety and social function subscales. For the 34 patients who did not volunteer stress at enrollment, enrollment scores more closely approximated population norms and, except for the social function subscale, minimal changes were found at follow-up. Finally, there were no differences in change in PROMIS-29 scores between patients who did and did not volunteer COVID-related stress at enrollment based on group mean comparisons (p > 0.05 for all comparisons).

FIGURE 1.

The PROMIS-29 scores at enrollment and follow-up according to whether volunteer COVID-related stress at enrollment; p values are for differences in mean within-patient change. Error bars are for 95% confidence intervals.

Stresses at Follow-up

For the qualitative phase, patients were asked to volunteer ongoing and current sources of COVID-related stress, and these were grouped into overarching categories (Table 2). The numbers of categories volunteered per patient were 0 (18%), 1 (31%), 2 to 3 (42%), and 4 or more (9%). Categories are described below with supporting patient quotations in Table 1 Supplement, http://links.lww.com/RHU/A444.

TABLE 2.

Categories of Stress and Coping From Qualitative Analysis

| Sources of Stress | Methods of Coping |

|---|---|

| Overall high stress for everything, taken a toll | Note diminishing stress in multiple areas with time |

| Limitations on coming/going | Stay positive/control mindset |

| Increased family responsibilities | Family pulls together |

| Lost routines/had to make new routines | Take COVID-19 precautions |

| Continued fear of contracting infection | Keep busy at home/keep busy at work |

| Isolation | Recreational activities, including with pets |

| Need to still take precautions | Engage in new self-improvement activities |

| Adverse impact on physical and mental health | Maintain social contacts via telephone/social media |

| Workplace challenges to ensure safety | Adopt a new routine |

| Impeded in-person contact with family/friends | Engage in physical fitness/focus on physical health |

| Impeded in-person contact with general public | Stay outdoors more |

| Adverse impact on employment/finances | Moved out of NYC |

| Witness adverse impact on family/friends | Engage in spiritual activities |

| Moved out of NYC | Start antidepressant/antianxiety medications |

| Uncertainty of current and future course of virus | Obtain professional psychiatric care |

| Inconsistent scientific information about virus | Engage in unhealthy habits and behaviors |

Some patients (14%) reported the pandemic caused a high state of general stress and exacted a large toll on all aspects of life. These patients continued to be overwhelmed by the pandemic. Other patients (12%) reported new stresses due to the loss of home and work routines and the need to make new routines.

A sense of isolation and aloneness increased as the pandemic continued (18%) and was particularly poignant among patients who lived alone. Adverse effects on physical and mental health also were attributed to the pandemic, which, in turn, became stresses onto themselves (18%).

Stress associated with occupation was noted in 2 ways. First, patients reported challenges in the workplace (17%) to ensure safety, adapt to new protocols, and assume the workload of laid-off coworkers. Adapting to working from home was an ongoing stress that had been identified at enrollment. Other patients cited stress associated with employment (16%), specifically losing jobs, being laid-off, and being uncertain about job security. Resulting financial adversity compounded employment discontinuity for most of these patients.

The most common stresses involved interactions with family and friends (35%). This included decreased in-person contact as well as voluntary avoidance of children and social gatherings, particularly during holidays. Stresses also were associated with certain familial interactions, such as quarantining, providing financial assistance, and conflicts over what were adequate versus excessive safety precautions. There were also stresses interacting with the general public (20%), such as during religious services and at work.

Limitations in coming and going (23%), increased family responsibilities (14%), fear of contracting the virus (9%), the need to still take precautions (3%), and witnessing adverse psychological effects on family (7%) were stresses that were cited at enrollment and persisted to the follow-up. Finally, there were stresses associated with uncertainty regarding the future of the virus (14%) and the accuracy of scientific information (3%).

As summarized in a previous report,10 most patients (68%) had questions and concerns about newly available vaccines, including how they were developed, adverse effects, and potential impact on rheumatic disease.

Coping at Follow-up

Patients demonstrated resilience in the variety and breadth of coping strategies they invoked, with most patients citing multiple approaches. Coping strategies were grouped into categories (Table 2), and frequencies were calculated. The numbers of categories volunteered per patient were 1 (18%), 2 (34%), 3 to 4 (36%), and 5 or more (12%). Examples are summarized below. Categories are described below with supporting patient quotations in Table 2 Supplement, http://links.lww.com/RHU/A445.

The first strategies often cited were maintaining a positive mindset (33%) and focusing on diminishing virulence with time (17%). Relying on family support (19%) and maintaining contact by telephone and social media (27%) were other major coping methods. Companionship from pets also helped some patients (7%).

Occupying time was another coping strategy that was achieved in several ways, such as by keeping busy at home with chores and new projects (15%), keeping busy at work with increased job responsibilities (17%), engaging in self-improvement initiatives (7%), and organizing activities better with new routines (8%).

Being outdoors more (15%), exercising and walking more, and taking better care of health (30%) were common strategies to proactively safeguard well-being. Preserving well-being was also attempted by engaging in multiple recreational activities, including hobbies, computer games, and watching movies (29%), as well as spiritual and religious activities (9%).

Whereas for some patients maintaining COVID-19 precautions was an ongoing stress (3%), others (19%) stated it helped them cope. Similarly, whereas some patients considered moving out of NYC a stress (4%), others considered it a way to cope (12%). Some patients acknowledged they were experiencing marked stress and started antidepressant/antianxiety medications (8%) and obtained professional psychiatric care (5%).

Finally, some patients coped by engaging in unhealthy behaviors (12%), such as overeating, consuming excessive alcohol, and smoking.

Interestingly, some patients (9%) reported benefits from altered lifestyles due to the pandemic. These benefits included getting more sleep and having flexible schedules that permitted more rest.

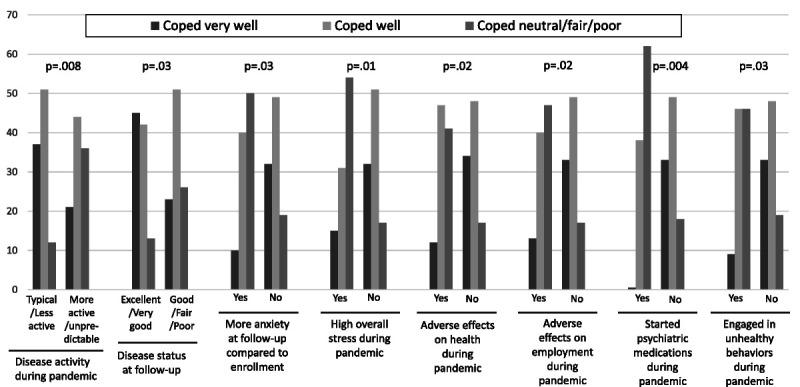

As above, in response to the single question about overall coping during the pandemic, 30% responded they coped very well, 48% well, and 22% neutral-fair-poor. More active or unpredictable disease activity during the pandemic and worse PROMIS-29 anxiety from enrollment to follow-up corresponding to a clinically important difference were associated with worse overall coping (Fig. 2). There were no associations with changes in other PROMIS-29 subscales, concerns about vaccines, or demographic or baseline clinical characteristics; however, patients who rated disease activity at follow-up as excellent or very good were more likely to respond they had better overall coping.

FIGURE 2.

Coping success at follow-up and associated clinical characteristics, stress, and methods of coping. Change in PROMIS-29 anxiety according to the threshold value for a clinically important difference.

When compared with the stress categories from the qualitative analysis, patients who volunteered persistently high stress, adverse effects of the pandemic on health, and adverse effects of the pandemic on employment also reported worse overall coping (Table 3). When compared with the coping categories from the qualitative analysis, patients who volunteered starting antidepressant/antianxiety medications and engaging in unhealthy behaviors also reported worse overall coping. Based on ordinal logistic regression, variables that remained associated with worse overall coping in the final model were worse enrollment–to–follow-up PROMIS-29 anxiety (OR, 4.4), not reporting excellent/very good disease status at follow-up (OR, 2.7), and pandemic-related persistent stress (OR, 5.7), adverse effects on health (OR, 3.0), and adverse effects on employment (OR, 6.1) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Bivariate and Multivariable Analyses Associated With Coping Worse During Pandemic

| Variables | Bivariate | Initial Multivariablea | Final Multivariablea | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% Confidence Interval | p value | OR | 95% Confidence Interval | p value | OR | 95% Confidence Interval | p value | |

| More PROMIS-measured anxiety at follow-up compared with enrollment | 4.4 | 1.2–15.8 | 0.03 | 4.0 | 1.0–16.5 | 0.05 | 4.4 | 1.1–17.3 | 0.03 |

| Rheumatic disease more active or unpredictable during pandemic | 3.0 | 1.3–6.6 | 0.008 | 1.9 | 0.7–4.8 | 0.19 | — | — | — |

| Disease status at follow-up not excellent/very good | 2.6 | 1.2–6.0 | 0.02 | 2.2 | 0.9–5.7 | 0.10 | 2.7 | 1.1–6.5 | 0.03 |

| High overall stress during pandemic | 4.8 | 1.5–15.2 | 0.008 | 4.0 | 1.1–14.6 | 0.04 | 5.7 | 1.6–20.1 | 0.007 |

| Adverse effects on health during pandemic | 3.4 | 1.2–9.5 | 0.02 | 2.1 | 0.6–6.8 | 0.22 | 3.0 | 1.0–9.0 | 0.05 |

| Adverse effects on employment during pandemic | 3.9 | 1.3–11.5 | 0.01 | 5.4 | 1.6–18.2 | 0.007 | 6.1 | 1.9–20.0 | 0.003 |

| Started antidepressant/antianxiety medications during pandemic | 8.4 | 1.9–38.5 | 0.006 | 3.3 | 0.6–18.2 | 0.16 | — | — | — |

| Engaged in unhealthy behaviors during pandemic | 3.9 | 1.1–13.1 | 0.03 | 1.6 | 0.4–6.8 | 0.52 | — | — | — |

a Based on ordinal logistic regression models.

DISCUSSION

In a cohort of patients assembled during the peak of COVID-related mortality in NYC, we found that physical and emotional function improved during the subsequent 10 months, with particular improvements in patients who reported the most stress at enrollment. During the follow-up period, some original stresses persisted, and new stresses arose; however, patients identified a wide variety of coping strategies that were effective, with more than three-quarters reporting they had coped well or very well. Coping less well was associated with persistently high general anxiety, more active rheumatic disease, and persistent adverse consequences to health and employment caused by the pandemic. Our study contributes to knowledge about the psychological and health effects of COVID-19 and offers the following suggestions for how rheumatologists can help patients rebound from the pandemic.

First, by recognizing that diverse and multiple self-identified coping strategies are effective for most patients, rheumatologists can assist patients by fostering patient-specific approaches to stress. Simultaneously, for patients with persistently high stress who are not coping well, rheumatologists should identify sources of stress and address those that are modifiable with targeted interventions in collaboration with other health care providers.21 For unmodifiable stresses, such as permanent changes to employment, assistance from social service professionals should be sought. This is consistent with reports from mental health experts who call for multifaceted interventions tailored to specific needs of patients, such as those with long-lasting adverse employment and financial consequences.3,22 However, as the health care providers with established doctor-patient relationships, rheumatologists should remain actively engaged in addressing anxiety and its impact in their patients.

A second insight offered by our study is that several stresses apparent at the start of COVID-19, such as adapting to working from home, persisted during the pandemic, and new stresses emerged. For example, maintaining social contacts was stressful for patients who were not previously conversant with remote interpersonal interactions. Conflict with family and friends over the extent of necessary COVID-19 precautions was another new stress that was ongoing and caused relational estrangements. This undesirable consequence is particularly relevant for patients with chronic conditions, for whom social support is essential for effective self-care.

Another insight from our study was to find that some patients perceived benefits to health from the pandemic. For these patients, altered lifestyles resulting in more sleep, less fatigue, less infection, and more attention to fitness contributed to overall better control of their rheumatic conditions. Rheumatologists should praise patients for identifying these benefits and encourage them to make these new habits permanent in their lifestyles.

Our findings are consistent with results reported by other investigators. For example, in a large longitudinal population-based study from February to July 2020, data regarding anxiety, depression, and other emotional states (i.e., calmness, gratitude) were collected with standard surveys.6 Anxiety increased by 26% from the pre- to acute-COVID period and then decreased by 25% from the acute to the sustained period. The investigators attributed this pattern to successful coping approaches in response to negative life-changing circumstances. Most studies among patients with rheumatic diseases, however, reported cross-sectional data or information obtained at the start of the pandemic by resurveying patients already in existing registries or ongoing studies. Using a variety of surveys, these studies reported worse overall emotional well-being among patients with diverse,23–25 as well as specific rheumatic diagnoses.26–31 These findings also were consistent across international studies.23,25,27–31 Except for one study reporting increased smoking and alcohol consumption, no studies to date have described specific coping strategies as reported in our study.23

In addition to the content of responses, our study also raises issues related to when should patients be queried during a pandemic. Patients were enrolled in our study during the first surge of the virus when there was great uncertainty about the nature of the pandemic and its potential threat to personal and societal welfare. Since that time, there have been other surges and other reasons for great uncertainty, such as the virulence of variants and what constitutes full vaccination. Surveying patients throughout the pandemic, including when they perceive themselves to be most vulnerable, helps clinicians understand the full spectrum of the emotional toll on patients. Thus, to comprehensively grasp the impact of the entire pandemic, patients' perspectives should be accounted for during times of greatest upheaval as well as when events are predictably unfolding.

Stress and coping are psychological constructs that have been extensively studied by experts in mental health, and several types of stress traditionally have been described with respect to chronic diseases.32 For example, epidemiological stress considers environmental or situational life events that are primarily negative or threatening, and psychological stress considers the perception that demands exceed the ability to adapt or accommodate to adverse situations. Both types of stress are predictive of worsening comorbidity, including for autoimmune diseases via hormonal mechanisms that mediate immune and inflammatory processes.33 In our study, epidemiological stress was precipitated by the widespread application of several external events, including threat of infection and social restrictions. Psychological stress was evident in our sample through continued fear of infection, lost routines, and feelings of isolation and being overwhelmed.

When confronted with stress, individuals attempt to adjust or cope through emotional, cognitive, and behavioral responses.7 Specific coping methods have been described, including problem-focused (i.e., attempting to moderate the impact of the event), emotion-focused (i.e., turning inward to regulate the affective response), and social support–focused (i.e., turning outward to gain assistance from others).34 These coping strategies were evident in our sample for problem-focused methods (e.g., taking COVID-19 precautions), emotion-focused methods (e.g., keeping a positive mindset), and social support–focused methods (e.g., maintaining social contacts, pulling the family together, and seeking professional psychiatric help).

Our study has several limitations. First, it was conducted in a tertiary care center in NYC with enrollment at the start of the pandemic; thus, our patients may have had COVID-19 experiences that were dissimilar to patients in other settings and later in the pandemic. We also did not stipulate definitions of stress and coping; thus, patients may have had heterogeneous perspectives for these psychological phenomena. Second, we conducted our follow-ups to coincide with the advent of vaccines to ascertain patients' perspectives about vaccination and ongoing risk of contracting COVID-19. As such, although we did learn about concerns related to vaccines, our follow-up was conducted before vaccination became a controversial and public issue. Thus, our study does not reflect social stresses that subsequently emerged regarding vaccination. Third, patients were enrolled from April 6 to April 21, 2020, the acute period coinciding with the first surge of the pandemic in NYC and the start of declining infection and mortality. Thus, the sample size was restricted by the purposeful narrow duration of the enrollment period, and the multiple comparisons made in the analyses should be interpreted in terms of this sample size. In addition, the modest number of patients per diagnosis precluded stratified detailed analyses according to diagnosis. Fourth, we reported our qualitative data with a descriptive analysis; newer methodologies advocate for an interpretive analysis, which attempts to link categories by bridging relationships among them.35

In summary, in our longitudinal study of patients specifically assembled during the first surge of COVID-19 and the peak of COVID-related mortality in NYC, we found that physical and emotional function improved as the pandemic unfolded, particularly among patients who reported more stress at enrollment. Some original stresses persisted, and new stresses emerged, but most patients reported they coped well or very well using patient-specific coping strategies. Targeted interventions are needed for those with long-lasting consequences from the pandemic and will require partnerships between rheumatologists and other health care professionals. In addition, rheumatologists should recognize effective patient-identified coping strategies and encourage continuation of lifestyle changes that patients consider beneficial to their rheumatic disease.

Footnotes

There was no external funding received for this work.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citation appears in the printed text and is provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.jclinrheum.com).

Contributor Information

Roland Duculan, Email: duculanr@hss.edu.

Deanna Jannat-Khah, Email: jannatkhahd@hss.edu.

Xin A. Wang, Email: xaw9001@nyp.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhatia A, Kc M, Gupta L. Increased risk of mental health disorders in patients with RA during the COVID-19 pandemic: a possible surge and solutions. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41:843–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonelli A Fallahi P Elia G, et al. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with systemic rheumatic diseases. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3:e675–e676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kapteyn A Angrisani M Bennett D, et al. Tracking the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on American households. Survey Res Methods. 2020;14:179–186. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hausmann JS Kennedy K Simard JF, et al. Immediate effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on patient health, health-care use, and behaviours: results from an international survey of people with rheumatic diseases [published online July 22, 2021]. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3:e707–e714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lemyre L, Tessier R. Measuring psychological stress. Concept, model, and measurement instrument in primary care research. Can Fam Physician. 2003;49:1159–1160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yarrington JS Lasser J Garcia D, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health among 157,213 Americans. J Affect Disord. 2021;286:64–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cousson-Gélie F Cosnefroy O Christophe V, et al. The Ways of Coping Checklist (WCC) validation in French speaking cancer patients. J Health Psychol. 2010;15:1246–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazarus RS. Coping theory and research: past, present, and future. Psychosom Med. 1993;55:234–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mancuso CA Duculan R Jannat-Khah D, et al. Modifications in systemic rheumatic disease medications: patients' perspectives during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021;73:909–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duculan R Jannat-Khah D Mehta B, et al. Variables associated with perceived risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2 infection during the COVID-19 pandemic among patients with systemic rheumatic diseases. J Clin Rheumatol. 2021;27:120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mancuso CA Duculan R Jannat-Khah D, et al. Rheumatic disease–related symptoms during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. HSS J. 2020;16(Suppl 1):36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang XA, Duculan R, Mancuso CA. Coping mechanisms mitigate psychological stress in patients with rheumatologic diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online May 28, 2021]. J Clin Rheumatol. 2022;28:e449–e455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duculan R, Mancuso CA. Perceived risk of SARS-CoV-2 at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent vaccination attitudes in patients with rheumatic diseases: a longitudinal analysis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Brouwer SJ Kraaimaat FW Sweep FC, et al. Experimental stress in inflammatory rheumatic diseases: a review of psychophysiological stress responses. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R89. 10.1186/ar3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cella D Riley W Stone A, et al. on behalf of the PROMIS Cooperative Group . Initial adult health item banks and first wave testing of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS™) network: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1179–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cella D Weinfurt K Revicki D Pilkonis P DeWalt D DeVellis R Cook K Buysse D Amtmann D Yount S Reeve B Riley W Stone A Rothrock NE Bode R Choi S Fries JF Gershon R Hahn EA Lai JS Rose M Hays RD, ©2008–2017 PROMIS Health Organization and PROMIS Cooperative Group . Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System–29 Profile V2.1 (PROMIS-29 V2.1). https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/instruments/patient-reported-outcomes-measurement-information-system-29-profile-v2.1.

- 17.ACR COVID-19 Vaccine Clinical Guideline Task Force . COVID-19 vaccine guidance summary for patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. American College of Rheumatology. 2021. https://www.rheumatology.org/Portals/0/Files/COVID-19-Vaccine-Clinical-Guidance-Rheumatic-Diseases-Summary.pdf.

- 18.Pawluch D, Neiterman E. What is grounded theory and where does it come from? In: Bourgeault I, Dingwall R, De Vries R, editors. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Methods in Health Research. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2010. p. 174–192. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berkwits M, Inui TS. Making use of qualitative research techniques. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:195–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell JL Quincy C Osserman J, et al. Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociol Methods Res. 2013;42:294–320. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elera-Fitzcarrald C Huarcaya-Victoria J Alarcon GS, et al. Rheumatology and psychiatry: allies in times of COVID-19. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:3363–3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boden M Zimmerman L Azevedo KJ, et al. Addressing the mental health impact of COVID-19 through population health [published online March 5, 2021]. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;85:102006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrido-Cumbrera M Marzo-Ortega H Christen L, et al. Assessment of impact of the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in Europe: results from the REUMAVID study (phase 1). RMD Open. 2021;7:e001546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adnine A Nadiri K Soussan I, et al. Mental health problems experienced by patients with rheumatic diseases during COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2021;17:303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koppert TY, Jacobs JWG, Geenen R. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Dutch people with and without an inflammatory rheumatic disease. Rheumatology. 2021;60:3709–3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kasturi S Price LL Paushkin V, et al. Impact of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on systemic lupus erythematosus patients: results from a multi-center prospective cohort. Lupus. 2021;30:1747–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macfarlane GJ Hollick RJ Morton L, et al. The effect of COVID-19 public health restrictions on the health of people with musculoskeletal conditions and symptoms: the CONTAIN study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:SI13–SI24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnstone G Treharne GJ Fletcher BD, et al. Mental health and quality of life for people with rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis in Aotearoa New Zealand following the COVID-19 national lockdown. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41:1763–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Itaya T Torii M Hashimoto M, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:2023–2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gica S Akkubak Y Aksoy ZK, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychology and disease activity in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis. Turk J Med Sci. 2021;51:1631–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iannuccelli C Lucchino B Gioia C, et al. Mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: stress vulnerability, resilience and mood disturbances in fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021;39(Suppl 130):153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen S, Gianaros PJ, Manuck SB. A stage model of stress and disease. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2016;11:456–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE. Psychological stress and disease. JAMA. 2007;298:1685–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Litman JA, Lunsford GD. Frequency of use and impact of coping strategies assessed by the COPE inventory and their relationships to post-event health and well-being. J Health Psychol. 2009;14:982–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Staller KM. Qualitative analysis: the art of building bridging relationships. Qual Soc Work. 2015;14:145–153. [Google Scholar]