Abstract

The insecticidal Cry toxins produced by the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis are comprised of three structural domains. Domain I, a seven-helix bundle, is thought to penetrate the insect epithelial cell plasma membrane through a hairpin composed of α-helices 4 and 5, followed by the oligomerization of four hairpin monomers. The α-helix 4 has been proposed to line the lumen of the pore, whereas some residues in α-helix 5 have been shown to be responsible for oligomerization. Mutation of the Cry1Ac1 α-helix 4 amino acid Asn135 to Gln resulted in the loss of toxicity to Manduca sexta, yet binding was still observed. In this study, the equivalent mutation was made in the Cry1Ab5 toxin, and the properties of both wild-type and mutant toxin counterparts were analyzed. Both mutants appeared to bind to M. sexta membrane vesicles, but they were not able to form pores. The ability of both N135Q mutants to oligomerize was also disrupted, providing the first evidence that a residue in α-helix 4 can contribute to toxin oligomerization.

The soil bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis produces proteins that display insecticidal properties. These Cry toxins are expressed as protoxins that are packaged as crystalline inclusions when the bacterium sporulates. When ingested by susceptible insect larvae, the protoxin is solubilized by the unique environment of the host gut and proteolytically cleaved or “activated” by the gut proteinases. The activated toxins are able to bind to receptor molecules present on the insect gut epithelium and insert into the membrane. This perturbation of the membrane results in the formation of pores, which is followed by colloid osmotic lysis and eventual insect death (for a review, see the article by Schnepf et al. [34]).

Elucidation of the three-dimensional structure of two distantly related Cry toxins has revealed a similar three-domain arrangement whereby each domain possesses a distinct structural fold (16, 27). Amino acid alignment of all Cry proteins demonstrates the presence of five conserved sequence blocks (19), suggesting that the members of the Cry family share this three-domain fold. The role of each domain has been studied extensively by mutagenesis and domain swap experiments (5, 25, 31, 33). Domains II and III are thought to be responsible for the binding of the toxin to specific gut receptors. The binding of domain II is crucial to toxicity, since various mutations in this domain disrupt the toxicity and binding of the toxin to membrane vesicles (21, 31, 32, 38). To date, mutations created in domain III have not dramatically reduced toxicity (5, 20); however, evidence suggests that this domain may have additional roles in toxin stability and channel function (6, 36).

Association of the toxin molecule with the epithelial membrane is thought to cause a large conformational change, possibly via the disruption of interactions between domains I and II (37), that results in the insertion of a region of domain I into the membrane. Domain I is comprised of a seven-helix bundle with several helices long enough to span the membrane (27). There is also significant evidence that mutations in domain I affect channel formation (1), confirming that a role of this domain is to form pores. Studies of mutations in the helices of domain I have revealed that residues in α-helices 3, 4, and 5 are important in toxicity (8, 25, 43).

The toxin is thought to insert into the membrane as a hairpin structure consisting of α-helices 4 and 5 (13, 37), with the remaining helices lying on the surface in an umbrella-like conformation (13, 24, 37). A direct role for the hairpin helices in formation of the pore has also been proposed. Evidence suggests that α-helix 4 is orientated to face the lumen of the pore and, as such, may be involved in channel function (30). Conversely, α-helix 5 appears to be in contact with the lipid milieu of the membrane and plays a vital role in the oligomerization of the hairpin (2, 10, 15). Oligomerization is believed to occur following insertion of the α-helix 4/α-helix 5 hairpin (13, 30) and to proceed to a final complex of four monomers (23, 30, 42).

Cry1Ac1 is a lepidopteran-specific Cry toxin. Possibly the most extensively studied toxin-insect combination is that of Cry1Ac1 with the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. A potential receptor for Cry1Ac1 from the midgut epithelium of M. sexta has been identified as an aminopeptidase N (APN) (22). The binding of Cry1Ac1 to this APN is inhibited by GalNAc, suggesting that this carbohydrate moiety is part of the recognition site on the receptor (5, 22, 29). Another Cry1A toxin, Cry1Ab5, is also toxic to M. sexta, and studies suggest that the two toxins share receptors (41). There are, however, significant differences between the two toxins. Cry1Ab5 demonstrates a lower toxicity to M. sexta compared to that of Cry1Ac1 (41). By using purified APN from M. sexta, Masson et al. (29) demonstrated that Cry1Ac binds to an exclusive site, in addition to the site it shares with Cry1Ab5. The binding of Cry1Ab5 to brush border membrane vesicles (BBMV) and APN, unlike Cry1Ac1, is not inhibited by GalNAc (29; N. Tigue, unpublished observations). Also, further studies have demonstrated the presence of different additional binding proteins for Cry1Ab5 and Cry1Ac1 (11, 40). The two Cry1A toxins demonstrate significant homology in domains I and II, whereas their domain III sequences are very different. This domain may therefore account for the observed differences in toxicity.

In a previous study, it was shown that an α-helix 4 mutant of the lepidopteran-specific toxin Cry1Ac1, Asn135Glu (N135Q or NQ) was nontoxic to M. sexta (9). An interesting feature of this mutant was that it bound to purified APN, in a surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assay, yet it did not form pores in M. sexta BBMV, as measured by a BBMV permeability assay. This suggested a deficiency in pore formation for this domain I mutant. This report describes the further characterization of the Cry1Ac1 N135Q mutant and the equivalent mutation in another Cry1A toxin, Cry1Ab5.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

BBMV preparation.

BBMV were prepared from the midguts of 5th instar M. sexta larvae by differential centrifugation according to the method described by Carroll and Ellar (6). The M. sexta eggs were purchased from Stuart Reynolds (University of Bath, School of Biological Sciences, Bath, United Kingdom) and raised on an artificial diet (3).

Plasmids and mutagenesis.

Cry1Ac1 protoxin was produced from the plasmid pMSV1Ac1 (38). The Cry1Ac1 N135Q mutant plasmid was a gift from Joseph Carroll, and its construction is described elsewhere (9). Cry1Ab5 protoxin was expressed from the plasmid pMAAB1 as described by Hofte et al. (18) and was a kind gift from Jeroen Van Rie (Aventis Cropscience NV, Ghent, Belgium). The Cry1Ab5 N135Q mutant was created by overlap extension PCR. The two overlapping fragments were produced by separate reactions with the following primer pairs: NT59(F) (5′-ATTCAATTCCAAGACATGAACAGTGCGTTAACAACCGCT-3′) and NT62(R) (5′-CGAAGAATATCTCCTCCTGT-3′) or NT60(F) (5′-AGCGGTTGTTAACGCACTGTTCATGTCTTGGAATTGAAT-3′) and NT61(R) (5′-TTATTCGAAGACGAAAGGGC-3′). A silent HpaI site (underlined) was introduced by primers NT59(F) and NT60(R) in order to screen for mutant clones. The two Pfu Turbo-derived products were used to amplify a product that was digested by SacI and recloned into the original vector. The clone was then transformed into Escherichia coli strain JM109 for expression.

Toxin expression and purification.

The pMSV1Ac1-derived plasmids were expressed in the acrystalliferous B. thuringiensis strain IPS78/11. Crystals containing the protoxins were recovered by sucrose density gradients as described by Thomas and Ellar (39). The crystals were solubilized for 1 h in 50 mM Na2CO3 (pH 10)–10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation. B. thuringiensis-expressed protoxins were quantitated by the Lowry method (28) with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard.

The Cry1Ab5 wild-type and mutant toxins were expressed in the E. coli strain JM109. Purification and solubilization was performed as described previously (26). E. coli-expressed toxins were quantitated by the Bradford method (4), with BSA as the standard. Activation of all toxins was achieved by using TLCK (Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone)-treated trypsin (Sigma) in an overnight digestion. Activated toxins were quantitated by densitometry and compared against purified and amino acid-analyzed toxin standards.

Toxins to be labeled with Na-125I were further purified by fast protein liquid chromatography. Approximately 2 mg of each trypsin-activated toxin was loaded onto a column packed with 1 ml of Source 15Q (Pharmacia) equilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.6). The column was then washed with the same buffer, and the protein was eluted with a salt gradient (with 20 mM Tris-HCl, 2 M NaCl). All four toxins eluted between 20 and 35% high-salt buffer and were stored in 100-μg aliquots at −80°C.

BBMV permeability assays.

The ability of the four toxins to form pores in M. sexta BBMV was demonstrated by measuring BBMV permeability through a light scattering assay. Fresh M. sexta BBMV were diluted in 10 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5) with 0.1% (wt/vol) BSA to a final concentration of 0.2 mg/ml. The BBMV solution was mixed with a hyperosmotic solution (10 mM HEPES-KOH with 0.1% [wt/vol] BSA and 150 mM KCl) with or without a various amounts of each activated toxin. Changes in toxin-induced permeability were measured by monitoring 90° light scattering at 450 nm.

Toxin iodination.

For iodination, two Iodobeads (Pierce) were preincubated in 200 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer (8 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4, 150 mM NaCl [pH 7.4]) with 1 mCi of Na-125I (Amersham). One hundred micrograms of each purified toxin was incubated with the Iodobeads for 15 min, followed by the removal of free iodine by using PBS-equilibrated PD-10 columns (Pharmacia). The specific activities (in curies per millimole) for the four toxins were as follows: 1Ac1, 24; 1Ac1NQ, 30; 1Ab5, 38; and 1Ab5NQ, 112.

Homologous and heterologous binding experiments.

Binding experiments were performed in a final volume of 200 μl of PBS containing 0.1% BSA. Labeled toxin (1Ac, 0.75 nM; 1Ac1NQ, 0.45 nM; 1Ab5, 0.5 nM; or 1Ab5NQ, 0.25 nM) was added to increasing amounts of unlabeled toxin (0 to 2,000 nM) in triplicate. The reactions were initiated by the addition of BBMV to a final concentration of 0.1 mg/ml, and incubation at room temperature was continued for 1 h. Bound toxin was separated from unbound toxin by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 15 min. The pellet was washed by the addition of 500 μl of PBS followed by centrifugation, removal of the supernatant, and measurement of the amount of radioactivity remaining in the pellet by using a gamma counter (Cobra II; Packard). Each experiment (one labeled toxin with one unlabeled toxin) was performed at least twice.

Binding data were analyzed by using the KELL for Windows package (version 6; Biosoft, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Individual experiments were first analyzed with the Radlig program, which determines the competition constant, Kcom (rather than Kd, to account for irreversible binding), and maximum receptor concentration (Bmax) values. Replicate experimental data were then processed by using the LIGAND program, which calculates more-accurate binding values and receptor site models. For clarity, single-site fit data are shown.

Dissociation experiments.

BBMV (0.1 mg/ml) were incubated with labeled toxin (1Ac, 0.75 nM; 1Ac1NQ, 0.45 nM; 1Ab5, 0.5 nM; or 1Ab5NQ, 0.25 nM) for 1 h at room temperature. An excess of the unlabeled counterpart of each toxin (2,000 nM) was then added, and samples were removed at various time points up to 1 h. The unbound and bound toxins were separated as described above, and the radioactivity in the pellet was counted. The reaction for each time point was carried out in duplicate, and each N135Q experiment was performed twice (see Fig. 2).

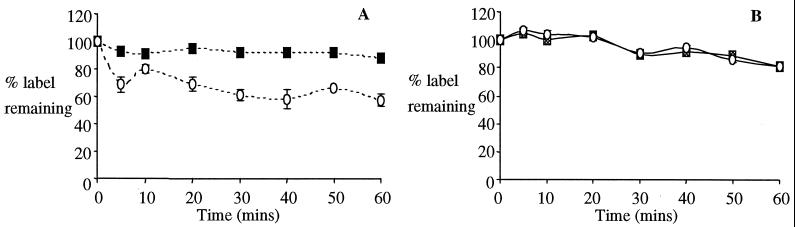

FIG. 2.

Dissociation of 125I-labeled wild-type and mutant toxins from M. sexta BBMV. The amount of binding is expressed as a percentage of the toxin bound following the addition of an excess of the equivalent unlabeled toxin. Nonspecific binding was subtracted from total binding. (A) Solid squares, Cry1Ac1; open circles, Cry1Ac1 N135Q. (B) Shaded squares, Cry1Ab5; open circles, Cry1Ab5 N135Q.

Oligomerization assays.

Each column-purified active toxin (0.3 μM) was incubated with or without BBMV (0.4 mg/ml) in a final volume of 50 μl of 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5). Incubation was continued for 1 h at room temperature, followed by centrifugation at 13,000 × g to separate bound from free toxin. The pellets were washed with 500 μl of 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) and resuspended in 50 μl. To both the pellet and the supernatant, as well as nonincubated toxin (also at 0.3 μM), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer (without phenylmethylysulfonyl fluoride and DTT) was added. Following heating to 70°C for 10 min, the samples were loaded onto an SDS-polyacrylamide gel (7.5% polyacrylamide) and subjected to immunoblotting with the relevant antitoxin antibodies (see Fig. 3).

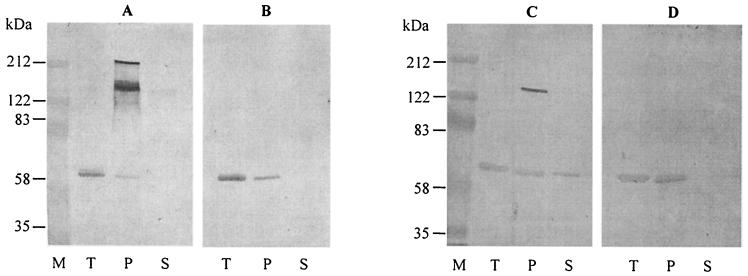

FIG. 3.

Immunoblots illustrating the oligomerization state of wild-type and mutant toxin molecules bound to M. sexta membrane vesicles. (A) Cry1Ac1. (B) Cry1Ac1NQ. (C) Cry1Ab5. (D) Cry1Ab5NQ. M, markers; T, toxin only; P, pellet fraction; S, supernatant.

RESULTS

Toxin expression and preliminary analysis.

All four toxins were expressed as approximately 130-kDa protoxins and were processed to approximately 65-kDa activated toxins by the addition of trypsin.

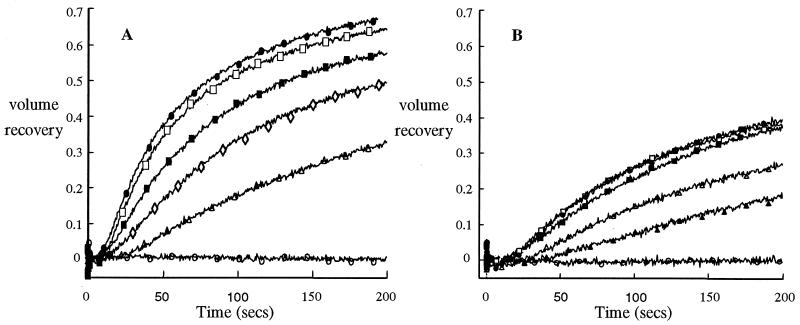

Formation of pores by wild-type and mutant toxins.

Figure 1 illustrates the ability of all four toxins to form pores in M. sexta membrane vesicles. Both wild-type toxins were able to permeabilize the BBMV, whereas even at high concentrations, neither N135Q toxin appeared to form pores. By comparing the results obtained for the wild-type toxins, it is clear that Cry1Ac1 requires less toxin to evoke a particular increase in volume recovery. By adding increasing amounts of each wild-type toxin, it is evident that the maximal value of volume recovery induced by Cry1Ab5 is lower than the maximal value induced by Cry1Ac1.

FIG. 1.

Extent of volume recovery obtained by M. sexta BBMV when incubated with increasing amounts of wild-type toxins (in picomoles per milligram of BBMV: solid triangles, 30; open triangles, 60; open diamonds, 150; solid squares, 300; open squares, 600; solid circles, 900). Not every concentration was used for both toxins. Only one concentration of each N135Q mutant is illustrated (open circles, 1,500 pmol/mg of BBMV). (A) Cry1Ac1 and Cry1Ac1N135Q. (B) Cry1Ab5 and its NQ mutant.

Homologous binding experiments.

Homologous binding experiments were performed to determine the binding affinities and binding site concentrations for each wild-type and mutant toxin with M. sexta BBMV (Table 1). The wild-type toxins, Cry1Ac1 and Cry1Ab5, displayed very similar Kcom values (1.52 and 1.53 nM, respectively), which agree with values published previously for these two toxins (12, 31, 41). The Cry1Ab5 N135Q mutant demonstrated a slightly higher Kcom than wild-type Cry1Ab5, suggesting that it may bind with less affinity to the Cry1Ab5 receptor(s). The difference between the two values, however, was not significant. In contrast, the Cry1Ac1 N135Q mutant appeared to bind to M. sexta vesicles with three times higher affinity than wild-type Cry1Ac1. The binding site concentrations for the wild-type toxins were approximately twofold different, with Cry1Ac1 having the greater concentration of receptor sites. Both mutants showed a decrease in receptor density relative to the wild-type toxins.

TABLE 1.

Binding characteristics of 125I-labeled wild-type and mutant toxins to M. sexta 5th instar BBMV as determined by homologous binding assaysa

| Toxin | Kcom (nM [±SE]) | Bmax (pmol/mg [±SE])b |

|---|---|---|

| Cry1Ac1 | 1.52 ± 0.48 | 0.62 ± 0.09 |

| Cry1Ab5 | 1.53 ± 0.66 | 0.32 ± 0.07 |

| Cry1Ac1 N135Q | 0.46 ± 0.14 | 0.21 ± 0.02 |

| Cry1Ab5 N135Q | 1.88 ± 0.76 | 0.17 ± 0.04 |

The values for Kcom and Bmax were calculated by the LIGAND program (KELL for Windows).

Picomoles of receptor protein per milligram of vesicle protein.

Heterologous binding experiments.

By using different labeled and unlabeled toxins, it was possible to analyze the competition for binding sites between the four toxins. As demonstrated in Table 2, Cry1Ac1 N135Q was able to displace 125I-labeled Cry1Ac1 and Cry1Ab5 from their receptor(s) to a much greater extent than wild-type Cry1Ac1 (0.14 versus 1.52 nM for labeled Cry1Ac1 and 0.35 versus 1.58 nM for labeled Cry1Ab5). Cry1Ab5 and its N135Q mutant were less able to compete with labeled Cry1Ac1 with Kcom values of 4.87 and 9.10 nM, respectively. When labeled Cry1Ab5 was used, no significant difference between competition by Cry1Ab5 and Cry1Ab5 N135Q was observed.

TABLE 2.

Binding characteristics of 125I-labeled wild-type and mutant toxins to M. sexta 5th instar vesicles as determined by heterologous competition assays

| 125I-labeled toxin | Unlabeled toxin | Kcom (nM ± SE)a |

|---|---|---|

| Cry1Ac1 | Cry1Ac1 | 1.52 ± 0.48 |

| Cry1Ac1 | Cry1Ab5 | 4.87 ± 1.22 |

| Cry1Ac1 | Cry1Ac1 N135Q | 0.14 ± 0.03 |

| Cry1Ac1 | Cry1Ab5 N135Q | 9.10 ± 3.48 |

| Cry1Ab5 | Cry1Ab5 | 1.53 ± 0.66 |

| Cry1Ab5 | Cry1Ac1 | 1.58 ± 0.78 |

| Cry1Ab5 | Cry1Ab5 N135Q | 2.35 ± 0.78 |

| Cry1Ab5 | Cry1Ac1 N135Q | 0.35 ± 0.29 |

The values for Kcom were calculated by the LIGAND program (KELL for Windows).

Dissociation of toxins from M. sexta BBMV.

The extent of irreversible binding displayed by all four toxins is illustrated in Fig. 2. Both wild-type toxins appear to bind almost irreversibly, with only 10 to 20% displaced after 1 h of incubation with an excess of unlabeled toxin. The 1Ab5NQ mutant dissociates to almost exactly the same extent at wild-type 1Ab5, whereas the 1Ac1NQ mutant dissociates such that approximately 60% of the toxin remains attached following addition of unlabeled toxin. This is suggestive of a more reversible component in the binding of this mutant toxin to the midgut vesicles.

The oligomerization state of the membrane-associated toxins.

The ability of each toxin to associate with BBMV and oligomerize is illustrated in Fig. 3. For both wild-type toxins, a major proportion of the toxin was present in the pellet fraction (i.e., associated with the membrane). These wild-type toxins were observed as three species with molecular masses of approximately 65, 130, and 200 kDa. These could potentially correspond to monomeric, dimeric, and trimeric toxin oligomer species, respectively. In contrast, the N135Q toxins associated with the BBMV were detected only as monomers in this experiment.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, an investigation into the properties of the Cry1Ac1N135Q mutant and its Cry1Ab5 equivalent, together with those of their wild-type counterparts, was carried out.

The toxicity of the two wild-type toxins to M. sexta has been described elsewhere (41) and has established that Cry1Ac1 is more toxic to M. sexta than Cry1Ab5. This result was also observed when BBMV permeability assays were performed (Fig. 1). These pore formation experiments represent the culmination of the postactivation steps of reversible binding, irreversible binding, oligomerization, and pore formation. In this study, a comparison of the pore formation activities of the two wild-type toxins revealed that, for Cry1Ac1, less toxin was required to elicit a particular volume of recovery. An increase in rate for Cry1Ac1 in proceeding from a reversibly bound toxin to an inserted toxin may be one explanation. The lower saturation level for Cry1Ab5, however, suggests a further reason, which is that Cry1Ac1 possesses an increased density of receptors present in the BBMV. The presence of exclusive receptors for Cry1Ac1 has been shown previously (11).

When either of the two mutant toxins was used in the BBMV permeability assay, no change in volume recovery was observed, even at high toxin concentrations. A previous experiment (9) demonstrated the nontoxicity of Cry1Ac1 N135Q to M. sexta, and yet binding to APN was observed. Thus, an analysis of the molecular events from binding to pore formation was required to elucidate which function(s) the mutants had lost.

Using 125I-labeled toxins, in a method described by Hofmann et al. (17), it was possible to compare binding affinities for all four toxins to M. sexta midgut vesicles. Only single-site data are shown, representing the high-affinity site for each toxin. In homologous binding experiments, the two wild-type toxins displayed similar binding affinities, suggesting that each binds as well as the other to the high-affinity site. This is in contrast to the pore formation and toxicity data that suggest that Cry1Ac1 is a more potent toxin to M. sexta. This apparent discrepancy is probably due to the presence of exclusive binding sites for Cry1Ac1, as described previously (11).

When the mutant toxins were analyzed by homologous binding assays, the Kcom for Cry1Ab5 N135Q was not significantly different from that for wild-type Cry1Ab5, whereas the Cry1Ac1 mutant appeared to possess a higher affinity for its binding site. This finding indicates that these mutants have not been compromised at the binding stage, and in fact, the binding of Cry1Ac1 N135Q is improved compared to that of its wild-type counterpart.

In the heterologous binding experiments all four toxins were competed with the two wild-type labeled toxins. When either wild-type labeled toxin was used, competition was observed, suggesting sharing of the wild-type high-affinity receptor sites. As a general trend, the Kcom observed through competition against wild-type toxin was 1Ab5NQ < 1Ab5 < 1Ac1< 1Ac1NQ. This suggests that Cry1Ac1 N135Q was more competitive than its wild-type counterpart, whereas the reverse was true for Cry1Ab5 N135Q. Despite the two wild-type toxins possessing similar binding affinities, as determined by homologous binding assays, Cry1Ab5 and its mutant were less able to compete for the Cry1Ac1 site. This might be explained by the ability of Cry1Ac1 to proceed from a reversible to an irreversible complex at a faster rate, as suggested by light scattering experiments (Fig. 1). Thus, Cry1Ac1 could quickly sequester receptor sites, resulting in fewer receptors available for Cry1Ab5. In a heterologous binding competition, it would appear therefore that Cry1Ab5 and its mutant bind irreversibly at a lower rate and have lower Kcom values.

The relative contribution of reversible binding to the overall affinity of each of the four toxins to M. sexta membranes is depicted in Fig. 2. From these studies, it appears that the two wild-type toxins are bound essentially irreversibly to the BBMV; however, the mutant toxins display different binding characteristics. The Cry1Ab5 N135Q mutant binds essentially the same as its wild-type counterpart, whereas the binding of Cry1Ac1 N135Q consists of a more reversible binding component. This agrees with the previous study (9), in which the Cry1Ac1 mutant could bind reversibly only to APN.

Thus far, it appears that the N135Q mutation has not affected the binding of Cry1Ab5, yet the mutant is not able to form pores. The mutation in the Cry1Ac toxin, however, has caused significant changes in binding. The mutated toxin displays increased binding to the site characterized in the 125I experiments, yet the overall binding consists of a more reversible component. This decrease in irreversible binding may represent a negative effect on binding to another receptor other than the one characterized.

The difference in binding phenotypes of the two mutant toxins is surprising, because the two wild-type proteins possess extremely similar domains I and II, with just four residues in domain I and two in domain II that are different. None of these six residues is in close proximity to Asn135 (P. Davis, personal communication), and therefore, they are unlikely to be responsible for the difference in binding characteristics. Furthermore, two previous studies comparing the toxicities of Cry1Ac and Cry1Aa to M. sexta demonstrated that the residues that differ between the two toxins in domains I and II (10 amino acids in total) are not involved in toxicity (14, 35). The major difference between the Cry1A toxins in this study is domain III. In addition to residue changes, Cry1Ac1 contains extra amino acids. Domain III of Cry1Ac1 has been shown to bind to the carbohydrate GalNAc (5), which is present on the receptor aminopeptidase N, whereas Cry1Ab5 does not (29). From the crystal structure of Cry1Aa (16), Asn135 does not appear to interact with domain III. It is possible, however, that the mutation of Asn135 to a Gln may affect a conformational change upon binding (36) that is different for each toxin. In support of this, a role for domain III in channel function has previously been proposed based on mutations that affect pore formation (7, 36).

Oligomerization studies were performed in order to investigate the effect of the Asn-to-Gln mutation on the oligomerization properties of the two Cry1A toxins. Figure 3 demonstrates that in solution (lanes T), all four toxins were present as monomers of approximately 65 kDa. In contrast, others (2, 25) have found that Cry1Ac1, but not Cry1Ab5, can be present as oligomers in solution. Oligomers of Cry1Ac1 in solution were not observed in this study, and this may be due to differences in toxin preparation and buffer composition.

When incubated with BBMV, the mutant toxins bound and appeared as monomers, whereas the majority of the wild-type toxins appeared in the pellet as monomers and higher-molecular-weight species. These species are likely to represent oligomers comprising two and three toxin molecules rather than membrane protein-toxin aggregates, as shown previously (2). As such, Cry1Ac1 appears to oligomerize to a greater extent than Cry1Ab5. The presence of dimer and trimer species agrees with previous results with Cry1Ac1 and Cry1Ab5 wild-type toxins (2, 25), but no species comprising four or more toxin molecules were observed. Knowles and Ellar (23) predicted a pore size of 1 to 2 nm, which would be able to accommodate four to six monomers. Masson et al. (30) have also predicted a pore consisting of at least four molecules. More recently, Vie et al. (42) used atomic force microscopy to show that the pore formed by Cry1Aa1 in a lipid environment consists of four subunits. It is possible that such higher-order structures were present in these experiments but were disrupted during the process of separating bound from unbound toxin.

Table 1 shows the Bmax values, representing the receptor concentration for each toxin. The two monomeric mutants appear to possess the same number of high-affinity binding sites, whereas the wild-type toxins display a higher concentration of receptors. If the values for the monomeric N135Q toxins are assumed to represent a toxin-receptor stoichiometry of 1:1, then the two wild-type toxins appear to bind in a 2:1 (Cry1Ab5) or 3:1 (Cry1Ac1) ratio. This dimer-trimer association with BBMV is also apparent in the oligomerization immunoblots (Fig. 3).

In the oligomerization studies, the two mutant toxins were present in the pellet fraction only as monomeric species, suggesting that the lack of toxicity may be caused by a deficiency in oligomerization. The mutation of Asn135 to Gln, therefore, appears to affect oligomerization. According to helical wheel models (25, 30), Asn135 may face the lumen of the pore, suggesting a role in channel function. Evidence suggests, however, that charged residues are important in this respect (30). For example, mutation of the charged residue Asp136 in Cry1Ac, which faces the lumen, abolished ion channel activity in M. sexta vesicles. The mutation of Asn135 to Gln, however, results in an increase in side chain length but does not alter the charge. Thus far, only residues in α-helix 5 have demonstrated a role in oligomerization (2, 25), and it is likely that the interaction of α-helix 5 with α-helix 4 is the most important for aggregation (15). Thus, it may be true that the mutation of Asn135 to Gln in these two toxins results in an α-helix 4 that is unable to interact with the α-helix 5 through disruption of the α-helix 4 packing.

This study has revealed that the two nontoxic N135Q mutants have been altered in some way, such that their ability to oligomerize has been compromised. Because both mutant toxins are also pore formation deficient, this suggests a critical role for oligomerization in the functioning of the Cry toxins. In addition, this is the first study to report the involvement of an α-helix 4 residue in oligomerization. The Cry1Ab5 N135Q mutant essentially represents an oligomerization-deficient wild-type toxin and, as such, further strengthens the notion that oligomerization occurs following irreversible binding.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Catherine Chambers for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmad W, Ellar D J. Directed mutagenesis of selected regions of a Bacillus thuringiensis entomocidal protein. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;68:97–104. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90132-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson A I, Geng C, Wu L. Aggregation of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1A toxins upon binding to target insect larval midgut vesicles. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2503–2507. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.6.2503-2507.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell R A, Joachim F G. Techniques for rearing laboratory colonies of tobacco hornworms and pink bollworms. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1976;69:365–373. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burton S L, Ellar D J, Li J, Derbyshire D J. N-Acetylgalactosamine on the putative insect receptor aminopeptidase N is recognised by a site on the domain III lectin-like fold of a Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal toxin. J Mol Biol. 1999;287:1011–1022. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carroll J, Ellar D J. An analysis of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin action on insect midgut-membrane permeability using a light scattering assay. Eur J Biochem. 1993;214:771–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen X J, Lee M K, Dean D H. Site-directed mutations in a highly conserved region of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin affect inhibition of short circuit current across Bombyx mori midguts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9041–9045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X J, Curtiss A, Alcantara E, Dean D H. Mutations in domain I of Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxin Cry1A(b) reduce the irreversible binding of toxin to Manduca sexta brush border membrane vesicles. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6412–6419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.6412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper M A, Carroll J, Travis E, Williams D H, Ellar D J. Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac toxin interaction with Manduca sexta aminopeptidase N in a model membrane environment. Biochem J. 1998;333:677–683. doi: 10.1042/bj3330677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cummings C E, Ellar D J. Chemical modification of Bacillus thuringiensis activated δ-endotoxin and its effect on toxicity and binding to Manduca sexta midgut membranes. Microbiology. 1994;140:2737–2747. [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Maagd R A, van der Klei H, Bakker P L, Stiekma W J, Bosch D. Different domains of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxins can bind to insect midgut membrane proteins on ligand blots. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2753–2757. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.8.2753-2757.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garczynski S F, Crim J W, Adang M J. Identification of putative insect brush border membrane-binding molecules specific to Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin by protein blot analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:2816–2820. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.10.2816-2820.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gazit E, La Rocca P, Sansom M S, Shai Y. The structure and organisation within the membrane of helices composing the pore-forming domain of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin are consistent with an “umbrella-like”structure of the pore. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12289–12294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ge A Z, Rivers D, Milne R, Dean D H. Functional domains of Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal crystal proteins. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:17954–17958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerber D, Shai Y. Insertion and organisation within membranes of the δ-endotoxin pore-forming domain, helix 4-loop-helix 5, and inhibition of its activity by a mutant helix 4 peptide. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23602–23607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grochulski P, Masson L, Borisova S, Pusztai-Carey M, Schwartz J-L, Brousseau R, Cygler M. Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1A(a) insecticidal toxin crystal structure and channel formation. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:447–464. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hofmann C, Luthy P, Hutter R, Pliska V. Binding of the delta endotoxin from Bacillus thuringiensis to brush-border membrane vesicles of the cabbage butterfly (Pieris brassicae) Eur J Biochem. 1988;173:85–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofte H, De Greve H, Seurinck J, Jansens S, Mahillon J, Ampe C, Vandekerckhove J, Vanderbruggen H, Van Montagu M, Zabeau M, Vaeck M. Structural and functional analysis of a cloned delta endotoxin of Bacillus thuringiensis berliner 1715. Eur J Biochem. 1986;161:273–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb10443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofte H, Whiteley H R. Insecticidal crystal proteins of Bacillus thuringiensis. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:242. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.2.242-255.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenkins J L, Lee M K, Sangadala S, Adang M J, Dean D H. Binding of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac toxin to Manduca sexta aminopeptidase-N receptor is not directly related to toxicity. FEBS Lett. 1999;462:373–376. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01559-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenkins J L, Lee M K, Valiatis A P, Curtiss A, Dean D H. Bivalent sequential binding model of a Bacillus thuringiensis toxin to gypsy moth aminopeptidase N receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14423–14431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knight P J K, Crickmore N, Ellar D J. The receptor for Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1A(c) delta-endotoxin in the brush border membrane of the lepidopteran Manduca sexta is aminopeptidase N. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:429–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knowles B H, Ellar D J. Colloid-osmotic lysis is a general feature of the mechanism of action of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxins with different specificity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;924:509–518. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knowles B H. Mechanism of action of Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal proteins. Adv Insect Physiol. 1994;24:275–308. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar A S M, Aronson A I. Analysis of mutations in the pore-forming region essential for insecticidal activity of a Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6103–6107. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.6103-6107.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lambert B, Buysse L, Decock C, Jansens S, Piens C, Saey B, Seurinck J, Van Audenhove K, Van Rie J, Van Vliet A, Peferoen M. A Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal crystal protein with a high activity against members of the family Noctuidae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:80–86. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.80-86.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, Carroll J, Ellar D J. Crystal structure of insecticidal delta-endotoxin from Bacillus thuringiensis at 2.5 Å resolution. Nature (London) 1991;353:815–821. doi: 10.1038/353815a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masson L, Lu Y, Mazza A, Brosseau R, Adang M J. The Cry1A(c) receptor purified from Manduca sexta displays multiple specificities. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20309–20315. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masson L, Tabashnik B E, Liu Y-B, Brousseau R, Schwartz J-L. Helix 4 of the Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Aa toxin lines the lumen of the ion channel. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31996–32000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.31996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajamohan F, Cotrill J A, Gould F, Dean D H. Role of domain II, loop 2 residues of Bacillus thuringiensis CryIAb δ-endotoxin in reversible and irreversible binding to Manduca sexta and Heliothis virescens. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2390–2396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rajamohan F, Hussain S-R A, Cotrill J A, Gould F, Dean D H. Mutations at domain II, loop 3, of Bacillus thuringiensis CryIAa and CryIAb d-endotoxins suggest loop 3 is involved in initial binding to lepidopteran midguts. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:25220–25226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rang, C., V. Vachon, R. A. deMaagd, M. Villalon, J.-L. Schwartz, D. Bosch, R. Frutos, and R. Laprade. Interaction between the functional domains of Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal crystal proteins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2918–2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Schnepf E, Crickmore N, Van Rie J, Lereclus D, Baum J, Feitelson J, Zeigler D R, Dean D H. Bacillus thuringiensis and its pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:775–806. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.775-806.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schnepf H E, Tomczak K, Ortega J P, Whiteley H R. Specificity-determining regions of a lepidopteran-specific insecticidal protein produced by Bacillus thuringiensis. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:20923–20930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwartz J L, Potvin L, Chen X J, Brousseau R, Laprade R, Dean D H. Single-site mutations in the conserved alternating-arginine region affect ionic channels formed by Cry1Aa, a Bacillus thuringiensis toxin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3978–3984. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.10.3978-3984.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwartz J-L, Lu Y J, Soehnlein P, Brousseau R, Masson L, Laprade R, Adang M J. Restriction of intramolecular movements within the Cry1Aa toxin molecule of Bacillus thuringiensis through disulfide bond engineering. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:397–402. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00626-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smedley D P, Ellar D J. Mutagenesis of three surface-exposed loops of a Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal toxin reveals residues important for toxicity, receptor recognition and possibly membrane insertion. Microbiology. 1996;142:1617–1624. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-7-1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas W E, Ellar D J. Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis crystal δ-endotoxin: effects on insect and mammalian cells in vitro and in vivo. J Cell Sci. 1983;60:181–197. doi: 10.1242/jcs.60.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vadlamudi R K, Li T H, Bulla L A. Cloning and expression of a receptor for an insecticidal toxin of Bacillus thuringiensis. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:5490–5494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.5490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Rie J, Jansens S, Hofte H, Degheele D, Van Mellaert H. Specificity of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxins. Importance of specific receptors on the brush border membrane of the mid-gut of target insects. Eur J Biochem. 1989;186:239–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vie V, Van Mau N, Pomarède P, Dance C, Schwartz J L, Laprade R, Frutos R, Rang C, Masson L, Heitz F, Le Grimellec C. Lipid-induced pore formation of the Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Aa1 insecticidal toxin. J Membr Biol. 2001;180:195–203. doi: 10.1007/s002320010070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu D, Aronson A I. Localized mutagenesis defines regions of the Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin involved in toxicity and specificity. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2311–2317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]