Abstract

Contraceptive self-care interventions are a promising approach to improving reproductive health. Reproductive empowerment, the capacity of individuals to achieve their reproductive goals, is recognised as a component of self-care. An improved understanding of the relationship between self-care and empowerment is needed to advance the design, implementation and scale-up of self-care interventions. We conducted a systematic review of the peer-reviewed and grey literature published from 2010 through 2020 to assess the relationship between reproductive empowerment and access, acceptability, use or intention to use contraceptive self-care. Our review adheres to PRISMA guidelines and is registered in PROSPERO (ID CRD42020205235). A total of 3036 unique records were screened and 37 studies met our inclusion criteria. Most studies were conducted in high-income countries, were cross-sectional and had high risk of bias. Almost half included only women. Over 80% investigated male condoms. All but one study focused on use of self-care. We found positive relationships between condom use self-efficacy and use of/intention to use condoms. We found similar evidence for other self-care contraceptive methods, but the low number of studies and quality of the evidence precludes drawing strong conclusions. Few studies assessed causal relationships between empowerment and self-care, indicating that further research is warranted. Other underexplored areas include research on power with influential groups besides sexual partners, methods other than condoms, and access and acceptability of contraceptive self-care. Research using validated empowerment measures should be conducted in diverse geographies and populations including adolescents and men.

Keywords: systematic review, self-care, family planning, reproductive empowerment, empowerment

Résumé

Les interventions contraceptives autogérées sont une approche prometteuse pour améliorer la santé reproductive. L’autonomisation reproductive, la capacité des individus à réaliser leurs objectifs de procréation, est reconnue comme un élément de l’auto-prise en charge. Une meilleure compréhension de la relation entre l’auto-prise en charge et l’autonomisation est nécessaire pour faire progresser la conception, la mise en œuvre et l’élargissement des interventions autogérées. Nous avons mené un examen systématique des articles à comité de lecture et de la littérature grise publiés de 2010 à 2020 pour évaluer le lien entre l’autonomisation reproductive et l’accès à l’auto-prise en charge contraceptive, son acceptabilité, son utilisation ou l’intention de l’utiliser. Notre étude respecte les directives PRISMA et est enregistrée dans PROSPERO (ID CRD42020205235). Au total, 3036 fichiers uniques ont été examinés et 37 études ont réuni nos critères d’inclusion. La plupart des études avaient été menées dans des pays à revenu élevé, étaient transversales et couraient un risque élevé de partialité. Presque la moitié incluaient uniquement les femmes. Plus de 80% portaient sur les préservatifs masculins. Toutes les études sauf une se centraient sur le recours à l’auto-prise en charge. Nous avons trouvé des relations positives entre l’efficacité personnelle dans l’emploi de préservatifs et l’emploi/l’intention d’employer des préservatifs. Nous avons observé des données similaires pour d’autres méthodes contraceptives autogérées, mais le faible nombre d’études et la qualité des données empêchent de tirer des conclusions solides. Rares sont les études à avoir évalué les relations causales entre l’autonomisation et l’auto-prise en charge, ce qui indique que des recherches supplémentaires sont nécessaires. Parmi d’autres domaines inexplorés, il convient de citer la recherche sur le pouvoir de groupes influents autres que les partenaires sexuels, les méthodes différentes des préservatifs, ainsi que l’accès à l’auto-prise en charge contraceptive et son acceptabilité. Des recherches utilisant des mesures d’autonomisation validées devraient être réalisées dans diverses régions géographiques et groupes de population, notamment les adolescents et les hommes.

Resumen

Las intervenciones de autocuidado anticonceptivo son un enfoque prometedor para mejorar la salud reproductiva. El empoderamiento reproductivo, la capacidad de las personas para alcanzar sus metas reproductivas, es reconocido como un componente del autocuidado. Se necesita mejor comprensión de la relación entre el autocuidado y el empoderamiento para promover el diseño, la ejecución y la ampliación de intervenciones de autocuidado. Realizamos una revisión sistemática de la literatura revisada por pares y la literatura gris publicadas del 2010 al 2020 inclusive, con el fin de evaluar la relación entre el empoderamiento reproductivo y la accesibilidad, aceptabilidad, uso o intención de utilizar autocuidado anticonceptivo. Nuestra revisión cumple con las directrices de PRISMA y está registrada en PROSPERO (ID CRD42020205235). Se examinó un total de 3036 registros únicos y 37 estudios reunieron nuestros criterios de inclusión. La mayoría de los estudios fueron realizados en países de altos ingresos, eran transversales y tenían alto riesgo de sesgo. Casi la mitad incluía solo a mujeres. Más del 80% investigó el condón masculino. Todos salvo un estudio se centraron en el uso del autocuidado. Encontramos relaciones positivas entre la autoeficacia para el uso del condón y el uso o la intención de usar condones. Encontramos evidencia similar para el autocuidado con otros métodos anticonceptivos, pero la poca cantidad de estudios y baja calidad de la evidencia nos impide sacar conclusiones firmes. Pocos estudios evaluaron las relaciones causales entre el empoderamiento y el autocuidado, lo cual indica que es necesario realizar más investigaciones. Otras áreas poco exploradas son: investigación sobre el poder con grupos influyentes además de parejas sexuales, métodos además de condones, y accesibilidad y aceptabilidad del autocuidado anticonceptivo. Se debe realizar investigaciones utilizando medidas de empoderamiento validado en diversas regiones geográficas y poblaciones, tales como adolescentes y hombres.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) considers self-care interventions one of the most promising approaches to improving health.1 In their guideline on self-care interventions, the WHO broadly defines self-care as “the ability of individuals, families, and communities to promote health, prevent disease, maintain health, and cope with illness and disability with or without the support of the health provider.”1 The guideline covers a range of voluntary family planning and reproductive health topics and makes recommendations on specific self-care interventions relevant to sexual and reproductive health. It also offers a framework for self-care based on a person-centred approach to health and well-being and includes key principles of human rights, ethics, and gender equality.

While work is ongoing to refine the definition of self-care, and contraceptive self-care interventions have only recently received heightened attention for their potentially transformative role in improving reproductive health, the family planning community has been working on different aspects of self-care for quite some time. Indeed, WHO notes in the guideline that recommendations already exist on several aspects of self-care and that one goal of the guideline was to bring together both new and existing WHO recommendations and good practice statements. Three new recommendations for self-care interventions for providing high-quality family planning services included self-administered injectable contraception, over-the-counter oral contraceptive pills (OCPs), and home-based ovulation predictor kits for fertility management. Several existing recommendations to provide high-quality family planning services were highlighted: (1) provision of a range of user-administered contraceptive methods as listed in the WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (MEC),2 including the combined contraceptive patch, combined contraceptive vaginal ring, progesterone-releasing vaginal ring, and barrier methods (e.g. male latex, male polyurethane, and female condoms; the diaphragm [with spermicide]; and the cervical cap); and (2) provision of up to a one-year supply of OCPs depending on the user’s preference and intended use. The guideline also highlights existing guidance on task sharing or task shifting to include different health worker cadres, as well as the individual user, to improve access to family planning, and draws attention to the notion that self-care goes beyond method use.

Since The Programme of Action of the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), which highlighted family planning within a human rights framework,3 there has been increased recognition of the importance of empowerment, particularly women’s empowerment, for a range of health and development outcomes.4–7 More recently, the concept of reproductive empowerment has received growing attention as the dimension of empowerment that supports universal access to contraception and reproductive health care and facilitates the agency of individuals and couples to achieve their reproductive goals.8–10

Reproductive empowerment is a broad concept with many subcomponents and related constructs. Several frameworks have been developed and focus on the various dimensions of reproductive empowerment, such as individual and structural power dynamics, as well as psychosocial processes, beginning with the existence of choice and progressing to the exercise and achievement of choice.8,9,11,12 While the terminology may vary, reproductive empowerment is generally conceptualised as the result of the interaction between individual and structural factors.

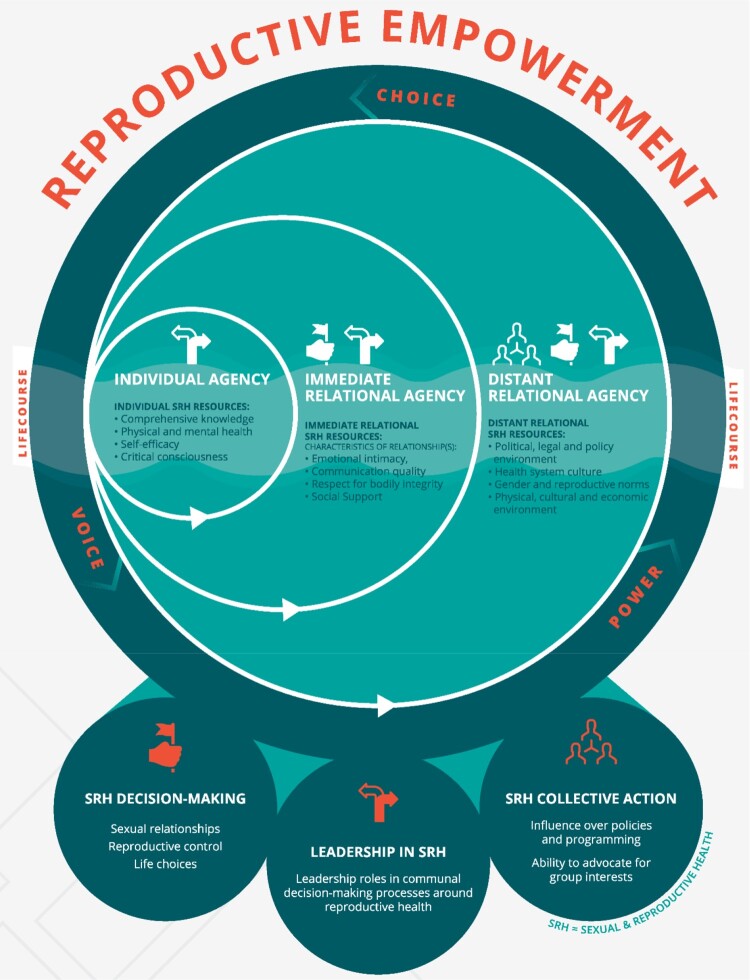

One such framework (Figure 1) developed by the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) with funding from the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and in partnership with MEASURE Evaluation, defines reproductive empowerment as:

Both a transformative process and an outcome, whereby individuals expand their capacity to make informed decisions about their reproductive lives, amplify their ability to participate meaningfully in public and private discussions related to sexuality, reproductive health and fertility, and act on their preferences to achieve desired reproductive outcomes, free from violence, retribution or fear.8

Figure 1.

ICRW conceptual model of reproductive empowerment

At the core of this framework is “agency,” defined as individuals’ capacity to take deliberate actions to achieve their reproductive goals. We selected this framework because, unlike other models of empowerment, the ICRW framework focuses on agency within and across distinct individual, immediate relational and distant relational levels, and explicitly includes men. The authors of the framework further describe that,

within the context of specific social interactions at each of these levels, men and women express varying degrees of voice, choice and power, drawing on resources to enhance their agency, all of which are influenced by where they are in their reproductive life course. In the reproductive realm, this is expressed through the processes of decision-making, leadership, and collective action.8

Further, at each level, individuals draw on resources to enhance their agency within specific relationships. For example, resources that are relevant at the individual level include comprehensive sexual and reproductive health knowledge, self-efficacy, education, or employment. Resources at the immediate relational level include emotional intimacy, type of communication, or the presence of violence in the relationship. Examples at the distant relational level include gender norms, health system culture, and political environment. When applying this framework to contraceptive self-care, we might hypothesise, for example, that individuals with greater agency in their health care decision-making will be more likely to find self-care contraceptive methods acceptable because they could enact more agency in fitting self-care methods into their lives. An example hypothesis of these relationships working in the opposite direction could be that the process of using self-care contraception could lead to a user having a stronger sense of autonomy of over their reproductive health.

The WHO guideline on self-care interventions also describes aspects of the individual (e.g. self-reliance, empowerment, autonomy, personal responsibility, and self-efficacy) as well as the larger community as fundamental principles of self-care.1 While the guideline states that reproductive empowerment and related constructs are elements of self-care, it also hypothesises that self-care may increase reproductive empowerment. For example, one of the research questions in the guideline is, “How might self-care interventions promote access, autonomy and empowerment without compromising safety and quality?” Further, we sought to investigate this relationship in the opposite direction, that is: Are self-care interventions more readily used by those who feel more empowered? This is important to assess to ensure self-care interventions are accessible to all who need or want these interventions. A better understanding of the relationship between self-care and reproductive empowerment is needed to advance the design, implementation, and scale-up of self-care interventions.

There is an absence of systematic review evidence for contraceptive self-care interventions and reproductive empowerment. To fill this gap, we conducted a systematic review of studies published in the peer-reviewed and grey literature to understand this relationship. Our review draws upon the ICRW framework and focuses on proximal aspects of individual and immediate relational agency, the resources which affect agency at these two levels, decision-making ability, and related concepts such as reproductive autonomy. In alignment with the WHO guideline we conceptualised contraceptive self-care broadly to include access, acceptability, use of or intention to use self-care contraceptive methods as well as self-care interventions using digital technology. Our objectives were to clarify the evidence base around the relationship between contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment, and to document existing definitions, measures, and use of reproductive empowerment outcomes in relation to contraceptive self-care. The findings from this review may increase our understanding of when and why self-care interventions work or do not work. Researchers may also use the findings to guide their selection of reproductive empowerment measures for the study of contraceptive self-care, informed by measures that have been previously validated. Stakeholders could apply evidence from this review to inform their decisions about which self-care interventions to implement within their family planning programmes.

Methods

In conducting this systematic review, we adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines13 and registered the review with PROSPERO (ID CRD42020205235).

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion in the review if they were published between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2020; were available in English; and reported primary quantitative or qualitative data on the relationship between access, acceptability, use, or intention to use contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment. We limited the review to the last 10 years to focus on the literature related to current discussions of contraceptive self-care. The populations, interventions, comparators, and outcomes (PICO) framework14 we used to define the search strategies were:

Population: Men and women of reproductive age; health care providers

Intervention: Contraceptive self-care

Comparison: Any or none

Outcomes: Quantitative or qualitative data on the relationships between reproductive empowerment and contraceptive self-care access, acceptability, use, or intention to use

We excluded secondary data analyses only when the primary data analysis also met the inclusion criteria, as well as non-research documents such as opinion pieces.

We followed the WHO guideline on self-care interventions to define the types of contraceptive self-care eligible for inclusion1. Certain user-dependent methods were always considered self-care for this review: oral contraceptive pills (OCP), emergency contraception (EC), contraceptive vaginal ring (VR), contraceptive patch, rhythm method, cycle beads, withdrawal, male condom, female/internal condom, diaphragm, cervical cap, sponge, lactational amenorrhoea method, and spermicide. Other methods were considered self-care in certain circumstances: contraceptive injectables (when self-injected), intrauterine device (when self-removed), traditional/herbal methods (when self-administered), fertility awareness including digital apps and ovulation predictor kits (when used for pregnancy prevention), and urine pregnancy tests (when used for initiating a contraceptive method). Client-facing digital technologies were considered self-care if they (1) were accessible by clients with or without a health care provider and if they (2) were created to provide individualised information, guidance, or self-management of contraception to enhance access, acceptability, use of and/or intention to use contraception. These technologies included short message service (SMS) reminders, telehealth, smartphone apps, interactive voice response systems, chatbots, and decision aids. We excluded studies that combined self-care and non-self-care contraceptive methods (e.g. all contraception or modern methods) if they did not report results specifically for one or more of the self-care methods defined above. We also excluded studies which examined the use of male or female condoms solely for HIV prevention and did not study these methods as pregnancy prevention methods.

In defining reproductive empowerment, we focused on the two most proximal aspects of the ICRW Reproductive Empowerment framework, the individual level and the immediate relational levels, the constructs that the ICRW framework defined as “resources” that affect agency at these two levels, and related concepts such as reproductive autonomy. We used the following definition of reproductive autonomy offered by the authors of the Reproductive Autonomy Scale15: “having the power to decide about and control matters associated with contraceptive use, pregnancy, and childbearing,” which we felt is consistent with the ICRW framework. Constructs eligible for inclusion included feeling empowered to make informed decisions about contraception, confidence in engaging in contraception method decision-making with a partner, and equitable power dynamics within a relationship. The broad constructs of knowledge and physical/mental health were not included in the scope of this review to allow focus on constructs more unique to empowerment. Studies were also eligible if they reported data on the inverse of these constructs, such as disempowerment, reproductive coercion, and presence of emotional, physical, sexual, or economic violence within the relationship. Studies were eligible if they assessed reproductive empowerment and related constructs whether they used validated or standardised scales, single survey items, or explored these concepts in qualitative interviews. While we included self-efficacy as it pertains specifically to reproductive empowerment, such as self-efficacy to negotiate contraception use, self-efficacy to use contraception correctly was not included, as this relates to knowledge of product use.

Information sources and search strategy

Our search strategy consisted of search terms related to the constructs of contraception, self-care, and reproductive empowerment (Appendix 1). We ran the search strategy in PubMed, Web of Science, Global Health, PsychInfo, CINAHL, and Academic Search Premier. We also hand-searched bibliographies of manuscripts and grey literature to identify eligible studies and conducted a web search to identify additional references for screening and selection. We included grey literature, including electronically available conference proceedings, materials available in the USAID Development Experience Clearinghouse, the Knowledge SUCCESS and Harvard Dataverse websites, and potentially relevant organisational websites (PSI, Jhpiego, PMA2020, Marie Stopes International, and WHO). Two researchers reviewed each title, abstract, and full text independently to determine eligibility and resolved discrepancies through discussion and involvement of a third researcher as needed.

Data extraction and data items

One researcher, who served as the primary reviewer, conducted data extraction and risk of bias assessments using structured data extraction tables in the Covidence systematic review management and data extraction software. A second reviewer checked each entry for accuracy.

We collected study-specific data on country, study design, population and setting, and sample size; contraceptive method(s) and attributes; and sociodemographic factors, including age, marital status, parity, socioeconomic status, and urban/rural residence. In addition, we collected information on three main data items: access, acceptability, use, or intention to use contraceptive self-care; reproductive empowerment construct, definition, and method of assessment (e.g. validated scale, single item); and relationships between the two constructs. We included results that were descriptive (e.g. observations of temporal trends or differences in proportions), statistical measures of association (e.g. cross-tabulations, regression analyses), and qualitative. We included data items that demonstrated findings on the relationships between access, acceptability, use or intention to use contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment as well as the inverse of these two constructs; that is, data items that assessed how the lack of contraceptive self-care access or acceptability, or self-care non-use may relate to reproductive disempowerment measures were also included.

Risk of bias and quality assessments

We assessed the risk of bias for all studies reporting quantitative data using a standardised eight-item tool.16 The presence or absence of the following was considered: a prospective cohort, a control or comparison group, pre/post-intervention data, random assignment of participants to the intervention, random selection of individuals for assessment, a follow-up rate of 80% or higher, equivalence of comparison groups based on sociodemographic measures, and equivalence of comparison groups at baseline for outcome measures. We considered studies to have low risk of bias if they possessed five or more of the eight items, and high risk of bias if they possessed four or fewer of the eight items.

For studies reporting qualitative data, we used a nine-item measure adapted from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist,17 to assess methodological quality according to the presence of a clear statement of research aims; the appropriateness of qualitative methodology, the research design for the research aims, and the recruitment strategy; whether data collection methods were appropriate to address the research topic, the relationship between research and participants had appropriately been considered, ethical issues had been adequately considered, and data analysis was sufficiently rigorous; and whether there was a clear statement of findings. We considered studies to be of good methodological quality if they possessed seven or more of the nine items, and to be of poor methodological quality if they possessed six or fewer of the nine items. No studies were excluded based on risk of bias.

Data synthesis

We summarised results by study type; whether access, acceptability, use, or intention to use contraceptive self-care was measured; and the direction of the relationship between self-care and reproductive empowerment. To create a narrative synthesis of quantitative and qualitative data from studies meeting the inclusion criteria, we summarised the evidence for relationships between reproductive empowerment constructs and contraceptive self-care and noted similarities or differences by geography, region, contraceptive self-care type, and other characteristics. In this review, we used WHO’s definitions of adolescents as individuals 10–19 years and young people as 10–24 years.18 We considered evidence for favourable effects to be those that most public health practitioners would consider promoting of health and well-being: for example, more reproductive empowerment associated with more contraceptive use, or the opposite, less empowerment associated with less contraceptive use. Similarly, we considered evidence for unfavourable effects to be those that most practitioners would consider detrimental or harmful: for example, more reproductive empowerment associated with less contraceptive use, or the opposite, less empowerment associated with more contraceptive use. Null effects are those relationships that are not statistically significant or where no qualitative relationship was reported between self-care and reproductive empowerment. We also summarised the measures used in the included studies to systematically assess reproductive empowerment. Due to substantial heterogeneity in outcomes and directionality, we did not perform a meta-analysis.

Other considerations

We assessed selective reporting within studies according to standardised guidelines.19 Because our objective was to synthesise evidence on multiple relationships between contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment, we did not systematically assess confidence in the cumulative evidence. Instead, we took into account risk of bias of individual studies when assessing the evidence.

Results

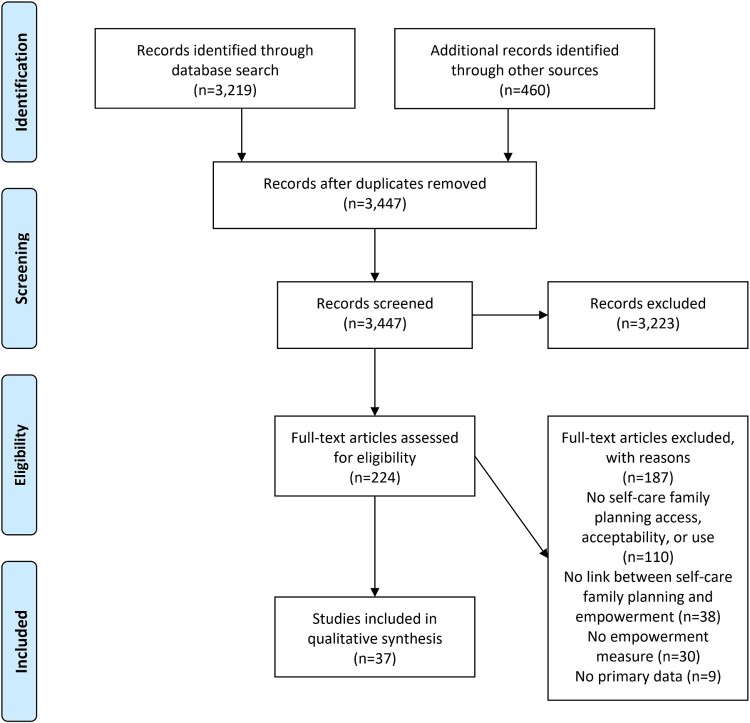

Our search strategy identified a total of 3219 references; after removing 191 duplicates and adding 460 references identified through hand-searching, we screened a total of 3447 unique records (Figure 2). We excluded 3223 records during title and abstract review and assessed 224 records in full-text review. Thirty-seven studies published in the peer-reviewed (n = 36) and grey (n = 1) literature met our inclusion criteria. The most common reasons for exclusion were not reporting access, acceptability, use, or intention to use contraceptive self-care (n = 110); not assessing the relationship between contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment (n = 38); and not measuring reproductive empowerment (n = 30).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram

A summary of the 37 studies which met the inclusion criteria is shown in Table 1. Nearly 30% of studies (n = 11) were from the United States and 8% (n = 3) from the United Kingdom. Two studies included participants from multiple countries. When grouped by continent, 14% of studies were conducted in Africa, 24% in Asia, 19% in Europe, 35% in North America, 3% in South America, and 3% in Oceania.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies (n=37)

| n (%) or Mean | |

|---|---|

| Region | |

| North America (Canada, United States) | 13 (35.1) |

| Asia (Bangladesh, China, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Vietnam) | 9 (24.3) |

| Europe (Italy, Portugal, Spain, United Kingdom) | 7 (18.9) |

| Africa (Ghana, Namibia, Nigeria, South Africa, Uganda, Zambia) | 5 (13.5) |

| South America (Brazil) | 1 (2.7) |

| Oceania (Fiji) | 1 (2.7) |

| Global (Web survey, participants from 112 countries) | 1 (2.7) |

| Gender | |

| Women only | 18 (48.6) |

| Men and women | 16 (43.2) |

| Men only | 3 (8.1) |

| Age | |

| Mean age (n=23 studies) | 21.4 |

| Adolescents (10–19 years) and youth (15–24 years)* | 17 (45.9) |

| Adults (25+ years) | 14 (37.8) |

| University students, age range not reported | 6 (16.2) |

| Type of contraceptive self-care (Multiple responses possible) | |

| Male condoms | 30 (81.1) |

| Client-facing digital technology | 4 (10.8) |

| Oral contraceptives | 4 (10.8) |

| Withdrawal | 3 (8.1) |

| Emergency contraception | 3 (8.1) |

| Other** | 3 (8.1) |

| Study design | |

| Cross-sectional study | 21 (56.8) |

| Qualitative research | 7 (18.9) |

| Randomized controlled trial (RCT) | 6 (16.2) |

| Single-group pre-test post-test study | 2 (5.4) |

| Nonrandomized experimental study | 1 (2.7) |

| Risk of bias, studies with quantitative data (n=31)*** | |

| High risk of bias | 27 (87.1) |

| Low risk of bias | 4 (12.9) |

| Methodological quality, studies with qualitative data (n=7)*** | |

| Good quality | 6 (85.7) |

| Poor quality | 1 (14.3) |

*One study included young people 13–26 years, one study included young people 21–30 years, one study included young people 15–30 years, and one study included young people 18–26 years.

**Other methods were the patch, vaginal ring, DMPA-SC self-injection, diaphragm, foam, jelly, lactational amenorrhea method (LAM), periodic abstinence, and rhythm method.

***One study reported both quantitative and qualitative data and is represented in both sections. Studies reporting quantitative data were determined to have low risk of bias if they possessed five or more of the eight items. Studies reporting qualitative data were determined to have good methodological quality if they possessed seven or more of the nine items.

Almost half of the studies (n = 18) included women only, and 43% (n = 16) included both women and men. Only three studies were of men only. The average age of participants across the 23 studies that reported discrete age was 21.4 years. Nearly half of the studies included only adolescents or young people and 38% focused only on adults. Sixteen percent of the studies included university students where the authors did not specify the students’ ages.

Regarding types of contraceptive self-care methods, most studies (81%; n = 30) investigated male condoms, four studies (10%) included client-facing digital technologies, four (10%) included OCPs, three (8%) included EC, and three (8%) included withdrawal. All other methods were only included in a single study that examined multiple methods. A total of five studies (14%) included more than one type of contraceptive self-care.

More than half of the studies (n = 21) employed cross-sectional research study designs, 19% used qualitative research designs, and 16% were randomised controlled trials. Three studies used quasi-experimental study designs. Among the 31 studies with quantitative data, 73% (n = 27) had a high risk of bias (Appendix 2). The most common study characteristics that resulted in a high risk of bias determination were lack of a cohort design, having no control or comparison group, and lacking pre- and post-intervention data. Of the seven studies presenting qualitative data, 86% (n = 6) were determined to have good methodological quality (Appendix 2). The most common methodological flaw in these studies was an inadequate consideration of the relationship between the researcher and the participant. The results and characteristics of each included study are presented in Table 2 (additional information about the studies can be found in Appendix 3).

Table 2.

Results

| Study ID | Study Design; Population; Setting | Contraceptive Self-care Type; Contraceptive Self-care Outcome(s) | Reproductive Empowerment | Direction of Relationship; Data Type | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Agency | |||||

| Escribano, et al.20 | RCT; Male and female youth ages 14–16 living in Spain; High schools |

Male condoms; (1) Intention to use condoms; (2) consistent condom use |

General self-efficacy (General Self-Efficacy Scale with Spanish adolescents), 10-item measure with 10-point Likert-type response options assessing general self-efficacy with high internal consistency (α=0.90) | Crossec.; Quant. |

Statistically significant positive direct effect within structural equation modeling of self-efficacy on intention to use condoms (β = .005, SE = 0.002, p = 0.048, n = 435), controlling for intervention effects; within this model, condom use intention significantly influenced consistent condom use (β = 1.70, SE = 0.33, p < 0.001, n = 435). |

| Espada, et al.21 | Cross-sectional study; Male and female youth ages 13–18 living in Spain; High schools |

Male condoms; (1) Intention to use condoms: single item with five-point Likert-type response option indicating level of certainty of using condoms in the future; (2) Frequency of using condoms |

Condom use self-efficacy (Condom use self-efficacy subscale from the HIV Attitudes Scale), three-item measure with four-point Likert-type response options assessing participant confidence to negotiate and use condoms with acceptable internal consistency (α= 0.76) | Crossec.; Quant. |

No statistically significant direct or indirect associations between condom use self-efficacy and intention to use condoms, nor between condom use self-efficacy and frequency of condom use (coefficients NR, p > 0.05, n = 410). |

| Ghobadzadeh, et al.22 | Cross-sectional study; Sexually active girls ages 13–17 living in the United States; Primary care clinics |

Male condoms; Condom use consistency: proportion of months using condoms every or most of the time |

Self-esteem: four-item measure adapted from Minnesota Student Survey with four-point Likert-type response options assessing self-esteem with good internal consistency (α=0.89) | Crossec.; Quant. |

No statistically significant relationship between self-esteem and condom use consistency (OR = 1.09, p = 0.5, n = 253). |

| Appleton23 | Qualitative research; Women ages 20–40 living in India; Community-based |

EC; Hypothetical use of emergency contraception |

Bodily autonomy and empowerment | CSC→RE; Qual. |

Participants described that EC pills could be a way for women to exact agency, gain control over their bodies, and feel empowered. |

| Dehlendorf, et al.24 | Cluster RCT; Women living in the United States ages 15–45 planning to start or change contraception method; Health care facilities |

Client-facing digital technology*; Randomised to My Birth Control decision support tool vs. standard of care |

Decision quality (Decisional Conflict Scale): 16-item measure with five subscales and five-point Likert-type response options assessing awareness of available options and perceived ability to make an informed choice, with lower scores indicating better satisfaction with making an informed decision (example items include “I am clear about which benefits matter most to me,” “I am choosing without pressure from others,” and “My decision shows what is important to me”) | CSC→RE; Quant. |

No statistically significant difference between intervention and control arms in odds of selecting best-informed response options for the total scale (OR = 1.18, 95% CI 0.80–1.74, p = 0.41). Intervention arm was statistically significantly more likely to select the best-informed response options for the Uncertainty subscale (vs control), indicating more decision certainty in the intervention arm (OR = 1.45, 95% CI 1.03–2.05, p = 0.03). No statistically significant differences within the Informed decision (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.00–1.80, p = 0.05), Effective decision (OR = 1.13, 95% CI 0.80–1.59, p = 0.50), Values clarity (OR = 1.17, 95% CI 0.86-1.59, p = 0.31), and Support (OR = 1.06, 95% CI 0.76–1.49, p = 0.41) subscales. |

| Stephenson, et al.25 | RCT; Women 15–30 years living in the United Kingdom; Health facilities in urban area |

Client-facing digital technology**; Randomised to Contraception Choices decision support tool vs. standard of care |

(1) Feeling empowered to speak to health professionals; (2) feeling more prepared before clinic appointments | CSC→RE; Qual. |

Intervention participants described feeling empowered to talk to providers about their preferred contraceptive method. Intervention participants also described that they felt more prepared to discuss contraception in these appointments. |

| Sundstrom26 | Qualitative research; Women 18–44 years living in the United States; Community-based |

OCPs; Hypothetical access to OCPs over the counter |

Autonomy and control over fertility | Crossec.; Qual. |

Participants described that having access to OCPs over the counter could improve their control over their fertility and their “bodily autonomy,” noting that this would be critical to enable them to make appropriate and desired life choices, such as motherhood, without being at risk of unintended pregnancy. |

| WHO27 | Cross-sectional study; HCPs and LP from 112 countries; Global survey |

OCPs, EC, patch, VR, DMPA-SC self-injection, diaphragm, client-facing digital technology; Hypothetical use |

(1) Perceiving empowerment to be a top reason for using family planning method; (2) perceiving empowerment as a benefit of method | Crossec.; Quant. |

Proportion HCPs and LP that felt empowerment was a top reason for using the method:

OCs: 49.8%, EC: 49.2%, patch: 46.5%, VR: 46.7%, DMPA-SC SI: 48.2%, diaphragm: 44.6%, client-facing digital intervention (Internet): 57.3%, client-facing digital intervention (app): 58.3%. |

| Immediate Relational Agency –Partner Negotiation | |||||

| Asante, et al.28 | Cross-sectional study; Male and female university students living in Ghana; Private university in urban area |

Male condoms; Condom use at last sex |

Condom use self-efficacy (CUSES): total score and assertive subscale | Crossec.; Quant. |

Statistically significant positive relationships between total condom use self-efficacy score and condom use at last sex (ρ = 0.730, p < 0.01, n = 426), and between Assertive subscale score and condom use at last sex (ρ = 0.550, p < 0.01, n = 426). |

| Buston, et al.29 | Qualitative research; Men ages 16–21 living in the United Kingdom at a young offender institution; Prison |

Male condoms; Condom use Condom use |

Contraceptive decision-making | RE→CSC; Qual. |

Men with consistent condom use described feeling responsible for carrying condoms with them and would use condoms to protect themselves from their partners becoming pregnant. Men with infrequent condom use did not describe being in control of condom use and stated that their partners would ask for condoms to be used if needed. |

| Chirinda, et al.30 | Cross-sectional study; Sexually active male and female youth ages 18–24 living in South Africa; Population-based household survey |

Male condoms; Inconsistent condom use with most recent sex partner |

(1) Partner risk reduction self-efficacy: four-item measure with four-point Likert-type response options to assess perceived ability to change sex behaviour within partnership, such as “Would you be able to avoid sex any time you didn’t want it?”, with moderate internal consistency (α = 0.73); (2) relationship control: | Crossec.; Quant. |

Among women, there was a statistically significant negative relationship between partner risk reduction self-efficacy and inconsistent condom use, adjusting for talking with partner about condoms, difficulty of getting condoms, lack of relationship control, sex with much older partner, ever having a transactional sex partner, and hazardous or harmful alcohol use (aOR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.61–0.97, p < 0.05, n = 1009). No statistically significant relationship between lack of relationship control and inconsistent condom use (aOR = 1.05, 0.94–1.22, p > 0.05, n = 1009), adjusting for partner risk reduction |

| Chirinda, et al.30 | Cross-sectional study; Sexually active male and female youth ages 18–24 living in South Africa; Population-based household survey |

Male condoms; Inconsistent condom use with most recent sex partner |

four-item measure with four-point Likert-type response options to assess perceived control in relationship, such as “Your partner has more control than you do in important decisions that affect your relationship,” with good internal consistency (α = 0.81) | Crossec.; Quant. |

self-efficacy, talking with partner about condoms, difficulty of getting condoms, sex with much older partner, ever having a transactional sex partner, and hazardous or harmful alcohol use. Among men, there were no statistically significant relationships between partner risk reduction self-efficacy and inconsistent condom use (OR = 0.92, 95% CI 0.79–1.06, p > 0.05, n = 1129) or between lack of relationship control and inconsistent condom use (OR = 1.01, 95% CI 0.88–1.17, p > 0.05, n = 1129). |

| Do, et al.31 | Cross-sectional study; Married women living in Vietnam; Population-based survey |

Male condoms; (1) Condom use at last sex; (2) consistent condom use in past 12 months |

Condom and sex negotiation self-efficacy: two-item measure with dichotomous response options assessing perceived ability to refuse sex and ask partner to use a condom | Crossec.; Quant. |

Statistically significant positive associations between condom and sex negation self-efficacy and odds of condom use at last sex (OR = 1.60, p < 0.001, n = 4632) and consistent condom use (OR = 1.56, p < 0.001, n = 4632). |

| Folayan, et al.32 | Cross-sectional study; Adolescents ages 10–19 living in Nigeria at HIV treatment centres and youth centres; Geographically representative survey |

Male condoms; Condom use at last sex |

(1) Confidence in discussing condom use: single-item, yes/no question assessing confidence to discuss condom use; (2) confidence in negotiating condom use: single-item, yes/no question assessing confidence to negotiate condom use | Crossec.; Quant. |

Statistically significant positive relationship between confidence in discussing condom use and odds of condom use at last sex (82.1% vs 7.9%, OR = 141.01, 95% CI 14.99–1326.36, n = 173). No statistically significant relationships between confidence in negotiating condom use and condom use at last sex (91.3% vs. 8.7%, OR = 2.87, 95% CI 0.72–11.42, p = 0.14, n = 173). |

| Gesselman, et al.33 | Single group pre-test post-test study; Couples ages 18–24 attending a university in the United States; University |

Male condoms; Condom nonuse: proportion of times a couple engaged in unprotected sex in past month |

Condom use self-efficacy (modified CUSES): four-item measure with five-point Likert-type response options measuring self-efficacy to use condoms | Crossec.; Quant. |

Unprotected sex at Time 1 was statistically significantly negatively correlated with condom use self-efficacy at Time 1 but not at Time 2 (T1: ρ = −0.47, p < 0.01; T2: ρ = −0.32, p > 0.05). Unprotected sex at Time 2 was not statistically significantly correlated with condom use self-efficacy at either time point (T1: ρ = −0.30, p > 0.05; T2: ρ = −0.24, p > 0.05). |

| Krugu, et al.34 | Qualitative research; Adolescent girls ages 14–19 living in Ghana; Community-based |

Male condoms; Using condoms with sex partners |

Negotiating condom use with partners | Crossec.; Qual. |

All sexually active participants stated that they used condoms during sex and that they felt empowered to negotiate and insist upon condom use prior to sexual intercourse. Participants gave example phrases such as “No condoms, no sex” to ensure partners complied, and indicated strong self-efficacy towards negotiating condom use. |

| Long, et al.35 | Cross-sectional study; Sexually active male and female college students living in China; Universities |

Male condoms; Condom use at last sex |

Contraceptive responsibility: single item asking, “During your most recent sexual intercourse, who ended up being responsible for ‘taking care’ of contraception?”; response options were “the man,” “the woman,” and “both the man and the woman” | Crossec.; Quant. |

Among males with a casual partner, there was a statistically significant negative relationship between condom use at last sex and having the man alone or the woman alone be responsible for contraception, compared to the man and woman together (man took responsibility vs. both: aOR = 0.15, 95% CI 0.08–0.50, n = 114; woman took responsibility vs. both: aOR = 0.19, 95% CI 0.07–0.67, n = 114). Among females with a steady partner, there was a statistically significant negative relationship between condom use at last sex and having the man take responsibility for contraception at last sex, compared to the man and woman together (Man took responsibility vs. both: |

| aOR = 0.11, 95% CI 0.04–0.78, n = 212), but not with having the woman take responsibility for contraception at last sex (woman took responsibility vs. both: aOR = 0.17, 95% CI 0.08–1.00, n = 212). There were no statistically significant relationships among males with a steady partner (man took responsibility vs. both: aOR = 1.09, 95% CI 0.69–2.11, n = 445; woman took responsibility vs. both: aOR = 0.87, 95% CI 0.50–2.22, n = 445) nor among females who recently had sex with a casual partner (man took responsibility vs both: aOR = 0.77, 95% CI 0.25–2.66, n = 55; woman took responsibility vs both: aOR = 0.07, 95% CI 0.01–2.39, n = 55). All analyses adjusted for age, spending, and major. | |||||

| Ritchwood, et al.36 | Cross-sectional study; Sexually active African American females ages 14–20 living in the United States; Sexual health clinics |

Male condoms; (1) Condom use at last sex; (2) proportion of times condoms used in past six months |

Partner communication self-efficacy: six-item measure with five-point Likert-type response options assessing perceived difficulty of talking with their male sexual partners about condom use and other sexual risk behaviours | Crossec.; Quant. |

No statistically significant relationships between partner communication self-efficacy and condom use at last sex (OR = 0.95, p = 0.66, n = 546) or with the proportion of times condoms were used in the past six months (β = 0.11, p = 0.52, n = 546), adjusting for partner age, sex enjoyment, sexual sensation seeking, sexual happiness, and interaction terms. |

| Santos, et al.37 | Cross-sectional study; Undergraduate university students ages 18–29 living in Portugal; University |

Male condoms; Condom use |

Condom use self-efficacy (CUSES-R): Portuguese version of CUSES, 15-item measure with five-point Likert-type response options assessing self-efficacy in using condoms with good internal consistency (α=0.86) | Crossec.; Quant. |

Among both genders, condom use self-efficacy scores were statistically significantly higher among participants that used condoms vs. no contraception (48.90 vs. 46.56, p < 0.001, n = 1946). This difference remained statistically significant among males (50.31 vs. 44.24, p < 0.001, n = 700), but was not statistically significant among females (47.81 vs. 47.40, p = 0.318, n = 1246). |

| Shih, et al.38 | Cross-sectional study; Sexually active women 14–45 years living in the United States; Health facilities |

Male condoms; Inconsistent condom use: Number of unprotected sex acts |

(1) Perceived control over condom use: single item asking who in the relationship has more say in condom use (response options: partner, participant, equal say, don’t talk about it); (2) condom use self-efficacy: five-item Confidence in Safer Sex scale assessing confidence to successfully negotiate condom use with a partner |

Crossec.; Quant. |

Women in the lowest condom use self-efficacy quartiles had statistically significantly higher risk of having more unprotected sex acts (lowest quartile vs. highest quartile: aRR = 2.50, 95%CI 1.81–3.47, n = 2087; second-lowest quartile vs. highest quartile: aRR = 1.59, 95% CI 1.16, 2.17, n = 2087). There were no significant differences in risk of having more unprotected sex acts comparing women in the second highest to the highest self-efficacy quartiles (aRR = 1.17, 95%CI 0.84–1.63, n = 2087). No statistically significant associations between perceived control over condom use and number of unprotected sex acts (partner has more say vs. equal say: aRR = 1.16, 95% CI 0.73–1.85, n = 2087; woman has more say vs. equal say: aRR = 1.11, 95% CI 0.91–1.35, n = 2087; don’t talk about it vs. equal say: aRR = 0.88, 95% CI 0.45–1.74, n = 2087). All analyses adjusted for race, ethnicity, age, marital status, education level, socioeconomic status, and sexual behaviours. |

| Smylie, et al.39 | Cross-sectional study; Young men and women ages 16–24 living in Canada; Community organisations, youth service organisations, drop-in centres, health clinics, shopping malls, and universities |

Male condoms; Condom use at last sex |

Protection self-efficacy: eight-item measure with five-point Likert-type response options assessing confidence in ability to negotiate safer sex with a partner, with good internal consistency (α= 0.883) | Crossec.; Quant. |

Participants who used condoms in the past 12 months had statistically significantly higher mean protection self-efficacy scores vs. those who did not (mean score 24.00, SD NR vs 22.13, SD NR, p < 0.001, n = 1185). |

| Sousa, et al.40 | Cross-sectional study; Adolescent and young adult students ages 13–26 living in Brazil; School affiliated with state education network |

Male condoms; Condom use: Single item with 5-point Likert-type response option indicating frequency of using condom with a fixed partner |

Condom use self-efficacy (Adapted CUSES in Portuguese) 14-item measure with three sub-scales, five-point Likert-type response options indicating self-efficacy to use condoms. Communication subscale assessed self-efficacy in discussing condom use with a partner (e.g. “I could talk about using condoms with any sexual partner” and “I could say no to sex if my partner refused to use a condom.” | Crossec.; Quant. |

Statistically significant differences in overall condom use self-efficacy score by frequency of using condoms with a fixed partner (mean [SD] score by condom use frequency: never 57.1 [25.2], hardly 67.5 [21.3], sometimes 64.1 [22.1], in most relations 72.2 [19.5], in all relations 75.2 [17.3], p = 0.036, n = 123). No statistically significant differences in mean communication domain scores by frequency of using condoms with a fixed partner (mean [SD] score by condom use frequency: never 66.6 [28.3], hardly 66.2 [23.9], sometimes 69.8 [20.6], in most relations 74.2 [27.1], in all relations 82.6 [19.8]; p = 0.077, n = 123). |

| Tafuri, et al.41 | Cross-sectional study; Freshman university students living in Italy; University |

Male condoms; Condom use at last sex |

Items in the Condom Use Skill Measure, a 13-item measure assessing attitudes, self-efficacy, and skills related to condom use with three-point Likert-type response options. No aggregate score reported. Relevant items are: “If I suggest to my partner we use a condom he/she might end the relationship,” |

Crossec.; Quant. |

Statistically significantly higher odds of condom nonuse among participants responding affirmatively to the question, “If I suggest to my partner we use a condom he/she might end the relationship,” compared to those who did not (OR = 3.0, 95% CI 1.1–8.8, p < 0.05, n = 1091); responding affirmatively to the question, “If I suggested we use a condom my partner would think I do not trust him/her,” compared to those who did not (OR = 4.9, 95% CI 2.3–11.1, p < 0.0001, n = 1091); responding affirmatively to the question, “If I suggested we use a condom my partner would think I am accusing him/her of cheating,” |

| “If I suggested we use a condom my partner would think I do not trust him/her,” “If I suggested we use a condom my partner would think I am accusing him/her of cheating,” “If I suggested we use a condom my partner might think I am cheating on him/her.” Other items included attitudes toward condoms, perceptions of condom comfort, and perceived need for condoms. | compared to those who did not (OR = 2.5, 95% CI 0.9–7.3, p = 0.06, n = 1091); and responding affirmatively to the question, “If I suggested we use a condom my partner might think I am cheating on him/her,” compared to those who did not (OR = 4.9, 95% CI 1.5–17.2, p < 0.001, n = 1091). | ||||

| Thomas, et al.42 | Cross-sectional study; Community-based sample living in the United Kingdom; Health facilities and condom trial participants |

Male condoms; (1) Mostly/usually used condoms in past 3 mo.; (2) Intention to mostly/usually use condoms in future |

Condom use self-efficacy (CUSES): Assertiveness subscale; total score NR | Crossec.; Quant. |

No statistically significant differences in mean assertiveness scores between participants who mostly or usually used condoms vs. those who did not (13.7 vs 13.3, p = 0.16) and comparing participants who intended to mostly or usually use condoms in the future vs. those who did not (13.6 vs. 13.4, p = 0.53). |

| Tingey, et al.43 | Cluster RCT; American Indian adolescents ages 13–19 living in the United States; Day camp |

Male condoms; Intention to use condoms: Single question asking if participants would use a condom if they had sex in the next six |

(1) Condom use self-efficacy: single item with five-point response option, lower score indicating greater self-efficacy; (2) partner negotiation self-efficacy: | Crossec.; Quant. |

Decreasing condom use self-efficacy associated with statistically significant decrease in condom use intention (aIRR = 0.82, 95% CI 0.73–0.92, n = 251), adjusting for age, HIV knowledge, general self-efficacy, response efficacy, extrinsic reward, severity, and sex in the past six months. |

| months (response options: Yes, maybe, don’t know, probably not, no) | single item with five-point response option, lower scores indicating greater self-efficacy | No statistically significant differences in partner negotiation self-efficacy comparing those who intended to use condoms vs. those who did not (Mean [SD]: 2.56 [0.10] vs. 2.41 [0.11]; AMD = 0.14, p = 0.285, n = 240). | |||

| Tsay, et al.44 | Single-group pre-test post-test study; Adolescents ages 13–18 living in the United States in youth detention centres; Juvenile detention facilities |

Male condoms; Intention to use condoms after leaving detention centre |

Condom self-efficacy: 15-item unidimensional measure with five-point Likert-type response options, similar in structure to Brafford and Beck Condom Use Self-Efficacy Scale (mechanics and assertive sub-scales) with good internal consistency (α=0.84) | Crossec.; Quant. |

Statistically significant positive relationship between intention to use condoms and condom use self-efficacy (β = 0.655, p < 0.001, n = 662), controlling for HVI/STI knowledge and condom use knowledge. Unclear if these were pre- or post-intervention data. |

| Xiao45 | Cross-sectional study; Unmarried junior and senior college students ages 18 + living in China; University |

Male condoms; Condom use: assessed as a latent construct using two indicators: condom use at last sex (yes/no) and frequency of using condoms in past 12 months (five-point Likert-type response options, higher scores indicating higher frequency) |

Partner communication about condom use: single question assessing frequency of telling partner they wanted to use a condom during sex in past three months with five-point Likert-type response option, higher scores indicate higher frequency | Crossec.; Quant. |

Statistically significant positive relationship between partner communication and condom use (β = 0.317, SE = 0.038, p < 0.001) in a structural equation model accounting for peer communication, self-efficacy to use condoms in various situations, subjective norms, and attitudes towards condoms. |

| Agha46 | Cross-sectional study; Men living in Pakistan married to women ages 15–49; Nationally representative survey |

Male condoms, withdrawal; (1) Intention to use withdrawal in next 12 months; (2) intention to use condoms in next 12 months |

Inability to discuss family planning with spouse or convince spouse to use family planning (single item) | Crossec.; Quant. |

Statistically significant negative relationship between reported inability to discuss family planning with spouse or convince them to use family planning and intention to use condoms (OR = 0.82, 95% CI 0.70–0.96, p < 0.05, n = 1805), and statistically significantly positive relationship with intention to use withdrawal (OR = 1.51, 95% CI 1.23, 1.84). |

| Bui, et al.47 | Cross-sectional study; Third-year female undergraduate students living in Vietnam; Universities |

Male condoms, emergency contraception, withdrawal, rhythm method; (1) Using contraception at first sex; (2) using condoms at first sex |

Sexual communication self-efficacy: five-item unidimensional scale assessing confidence in starting conversations with partner about safer sex, contraception, and negotiating condom use with moderate internal consistency (α=0.68) | Crossec.; Quant. |

Statistically significant positive relationship between sexual communication self-efficacy and using contraception at first sex (OR = 1.13, p = 0.039, n = 111). Contraception methods used at first sex were condoms, EC, withdrawal, and rhythm method. No statistically significant relationship between safer sex communication self-efficacy and using condoms vs. other contraception methods (EC, withdrawal, rhythm method) at first sex (OR = 1.15, p = 0.092, n = 71). |

| Do, et al.48 | Cross-sectional study; Women ages 15–49 currently married or cohabitating with a partner living in Namibia, Zambia, Ghana, or Uganda; Nationally representative surveys |

Male condoms, withdrawal, diaphragm, foam, jelly, LAM, periodic abstinence, female condom; Use of couple methods (male and female condoms, diaphragm, foam, jelly, withdrawal, LAM, and periodic abstinence) |

(1) Economic empowerment: five-item index with three-point Likert-type response options to assess decision-making balance in how income would be used between a woman and her husband, with higher scores indicating greater empowerment; (2) sociocultural activities: single-item | Crossec.; Quant. |

In Namibia, higher aggregated empowerment scores were associated with greater likelihood of using couple contraception methods vs. no contraception (aRR = 1.24, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001, n = 3235). There were no statistically significant associations between the following empowerment measures and use of couple contraceptive methods vs.no contraceptive methods: economic empowerment (aRRR = 1.05, SE = 0.06, p > 0.05, n = 3235), sociocultural activity decision-making (aRRR = 0.96, |

| measure asking who decided whether women could visit their family and relatives (woman alone or joint decision vs. other); (3) health-seeking behaviour: single-item measure asking who made decisions about the woman’s health care (woman alone or joint decision vs. other); (4) agreement on fertility preferences: single-item measure asking whether the woman and her partner wanted the same number of children (yes vs. no or don’t know); (5) sexual activity negotiation: six-item index with dichotomous response options to assess woman’s ability to negotiate sexual activity (such as refuse sex, ask partner to use condoms), higher scores indicating higher negotiation power among women | SE = 0.18, p > 0.05, n = 3235), health-seeking behaviour decision-making (aRRR = 0.89, SE = 0.19, p > 0.05, n = 3235), agreement on fertility preference (ARRR = 1.02, SE = 0.15, p > 0.05, n = 3235), and sexual activity negotiation (aRRR = 1.02, SE = 0.05, p > 0.05, n = 3235). In Zambia, there were statistically significant positive associations between agreement on fertility preferences and use of couple contraceptive methods vs. no contraceptive methods (aRR = 1.31, SE = 0.15, p < 0.05, n = 4241); and between sexual activity negotiation and use of couple contraceptive methods vs. no contraceptive methods (aRR = 1.08, SE = 0.03, p < 0.05, n = 4241). There were no statistically significant relationships between the following empowerment measures and use of couple contraceptive methods vs. no contraceptive methods: economic empowerment (ARR = 1.02, SE = 0.03, p > 0.05, n = 4241), sociocultural activity decision-making (ARR = 0.97, SE = 0.12, p > 0.05, n = 4241), and health-seeking behaviour decision-making (ARR = 0.95, SE = 0.11, p > 0.05, n = 4241). In Ghana, there were statistically significant positive associations between sexual activity negotiation and use of couple contraceptive methods vs. no contraceptive methods (aRRR = 1.13, SE = 0.05, p < 0.05, n = 2902). There were no statistically significant relationships between the following empowerment measures and use of couple contraceptive methods vs. no contraceptive methods: economic empowerment (aRRR = 1.02, SE = 0.09, p > 0.05, n = 2902), |

||||

| sociocultural activity decision-making (aRRR = 0.97, SE = 0.18, p > 0.05, n = 2902), health-seeking behaviour decision-making (aRRR = 0.82, SE = 0.15, p > 0.05, n = 2902), and agreement on fertility preferences (aRRR = 1.06, SE = 0.14, p > 0.05, n = 2902). In Uganda, there were statistically significant positive associations between economic empowerment and use of couple contraceptive methods vs. no contraceptive methods (aRRR = 1.09, SE = 0.04, p < 0.05, n = 5193) and between agreement on fertility preferences and use of couple contraceptive methods vs. no contraceptive methods (aRRR = 1.60, SE = 0.18, p < 0.001, n = 5193). There were no statistically significant relationships between the following empowerment measures and use of couple contraceptive methods vs. no contraceptive methods: sociocultural activity decision-making (aRRR = 1.11, SE = 0.17, p > 0.05, n = 5193), health-seeking behaviour decision-making (ARRR = 1.13, SE = 0.16, p > 0.05, n = 5193), and sexual activity negotiation (ARRR = 1.02, SE = 0.05, p > 0.05, n = 5193). All analyses adjusted for age, education, household wealth, religion, number of living children, exposure to family planning messages in mass media, number of methods known, and rural or urban community. Aggregate measures not reported for Zambia, Ghana, and Uganda because they were not statistically significant in unadjusted analyses. |

|||||

| Nelson, et al.49 | Nonrandomised experimental study; Women ages 18–40 living in the United States selected from a health insurance cohort to participate in an RCT, using OCPs as primary contraceptive method; Insurance coverage cohort |

OCPs; (1) Self-reported adherence in past three months: single item asking number of days missed a dose of OCPs in past three months; results categorised as high (three or fewer missed days) or low (more than three missed days); (2) Proportion of days covered in past 90 days: used pharmacy claims data to calculate proportion of days covered in past 90 days |

Contraceptive self-efficacy: eight-item scale (response structure NR) assessing confidence in preventing pregnancy and talking to partners about contraception with moderate internal consistency (α = 0.71). For analysis, scores were dichotomised at the mean into high or low self-efficacy. | Crossec.; Quant. |

Participants with high contraceptive self-efficacy were statistically significantly more likely to have high adherence to OCPs by self-report compared to those with low contraceptive self-efficacy (aOR = 1.99, 95%CI 1.18–3.37, n = 281), adjusting for age, relationship status, education level, household income, race/ethnicity, religion, future pregnancy intention, self-reported importance of avoiding pregnancy, and length of pill supply. Participants with high contraceptive self-efficacy were statistically significantly more likely to have high adherence to OCPs by self-report and pharmacy claims data together, compared to those with low contraceptive self-efficacy (aOR = 1.63, 95%CI 1.03–2.58, n = 202), adjusting for age, relationship status, education level, household income, race/ethnicity, religion, future pregnancy intention, self-reported importance of avoiding pregnancy, and length of pill supply. There were no statistically significant differences in OCP adherence by contraceptive self-efficacy score when measuring adherence using pharmacy claims data alone (aOR = 1.16, 95% CI 0.72–1.87, n = 253), adjusting for age, relationship status, education level, household income, race/ethnicity, religion, future pregnancy intention, self-reported importance of avoiding pregnancy, and length of pill supply. |

| Immediate Relational Agency – Intimate Partner Violence | |||||

| Chiodo, et al.50 | RCT; Ninth grade adolescent girls living in Canada who participated in a school-based cluster RCT and reported having a partner in the past 12 months at follow-up; High schools |

Male condoms; Condom use at last sex |

Actual and threatened physical dating violence (none, victim only, perpetrator only, mutually violent) | Crossec.; Quant. |

Girls in different dating violence profiles had statistically significantly different proportions of condom nonuse (proportion of participants with condom nonuse by violence profile: 34.2% no violence (n = 367), 37.0% victim only (n = 39), 33.3% perpetrator only (n = 32), 60.7% mutual (n = 81); χ23 df = 13.28, p < 0.01). |

| Davis51 | Cross-sectional study; Men 21–30 years living in the United States interested in sexual activity with women and had 1 or more instances of unprotected sex with a woman in past 12 mo.; Urban area |

Male condoms; Nonconsensual condom removal: Number of times since age 14 obtained condomless sex when female sex partner wanted to use a condom |

(1) Sexual aggression severity (adapted from Sexual Experiences Survey): number of items and scoring NR, assessed frequency of attempted and completed sexual assault; (2) condom use self-efficacy (CUSES) | Crossec.; Quant. |

zStatistically significant positive association with sexual aggression severity and nonconsensual condom removal (aOR = 1.063, 95% CI 1.032–1.095, p < 0.001, n = 626), adjusting for age and condom use self-efficacy. No statistically significant relationship between condom use self-efficacy and nonconsensual condom removal (OR = 0.931, 95% CI 0.509–1.703, p = 0.817, n = 626). |

| Mitchell, et al.52 | Qualitative research; Female university students ages 18–26 living in Fiji; University |

Male condoms; Condom use |

Reproductive coercion | RE→CSC; Qual. |

Almost half of participants described experiencing reproductive coercion in the form of being “pressured, manipulated, or deceived” into having condomless sex. Male partners coerced participants into having sex without a condom through questioning participants’ love, trust, or commitment to the relationship, making statements such as, “If you love me, if you like me, then don’t use a condom.” |

| Sharma, et al.53 | Qualitative research; Women living in India who recently injected drugs or used drugs through non-injecting routes; Community-based drop in centres |

Male condoms; Condom use |

Fear of partners and power dynamics within paid partnerships | Crossec.; Qual. |

Within paid partnerships, women reported not using condoms due to fear of violence from paying partners and due to the power dynamics involved in transactional sex. |

| Yamamoto, et al.54 | Cross-sectional study; Married women ages 15–49 living in Nepal using contraception; Nationally representative survey |

Male condoms; Currently using condoms |

Fear of partner: single item asking whether women were afraid of their partner with three-point Likert-type response options indicating, most of the time, some of the time, or never | Crossec.; Quant. |

40% of pill users and 33.3% of condom users reported fear of their partner (no statistical test conducted, n = 336). Women who feared their partner were statistically significantly less likely to use condoms vs. female sterilisation (Marginal effect: −0.070, SE: 0.288, p < 0.05, n = 616), adjusting for years of schooling, age, literacy, husband’s education, wealth quintile, and region. |

| Reiss, et al.55 | RCT; Women ages 18–49 living in Bangladesh receiving a menstrual regulation procedure; Public and private health clinics |

Client-facing digital technology;*** Receiving client-facing digital technology intervention |

Experiencing intimate partner violence | CSC→RE; Quant. |

Participants randomised to the client-facing digital technology intervention had statistically significantly higher odds of experiencing physical intimate partner violence as a result of being in the study (aOR = 1.97, 95% CI 1.12–3.46) but no higher odds of experiencing sexual intimate partner violence (12% intervention vs. 10% control, OR NR). Adjusted for age, socioeconomic status, experiences of violence during the study period not due to study participation, and experiences of violence before the study. |

| Thiel de Bocanegra, et al.56 | Qualitative research; Women ages 18 and older living in the United States at participating domestic violence shelters; Domestic violence shelters in urban area |

OCPs, male condoms; (1) Use of oral contraceptives; (2) use of male condoms |

Experiencing abuse within a relationship | RE→CSC; Quant. |

19% of women described that their abusive partners prevented them from using oral contraception by barring them from getting refills. 87% of women reported consistently using condoms with their abusive partner, with about half of these participants reporting that their partner refused to use a condom when asked. |

Note: Crossec. = Cross-sectional; CSC = Contraceptive self-care; EC = Emergency contraception pills; OCP = Oral contraception pills; RE = Reproductive Empowerment.

*My Birth Control, tablet-based interactive decision support tool to provide contraceptive education, elicit preferences for contraception attributes, and provide recommendations for methods matching patient preferences. Tool provider printout with patient preferences and questions to be shared with provider during visit.

**“Contraception Choices” website provides information about contraception and an interactive decision tool that queries women’s priorities for a contraceptive method and provides a list of the three methods that most closely fit women’s preferences.

***Interactive voice-recorded messages providing tailored information about contraception and linking participants to a counsellor at a call centre for additional information.

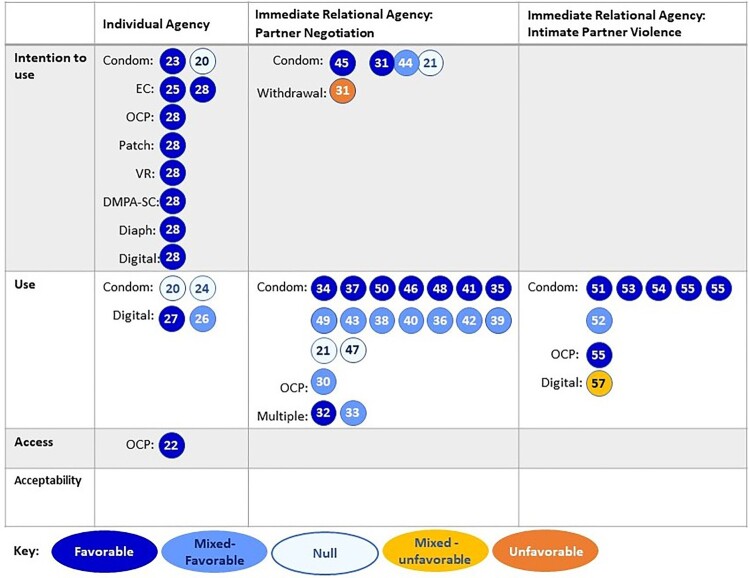

As described in the methods, we sought to understand the relationship between access, acceptability, use or intention to use contraceptive self-care and the individual and immediate relational agency aspects of the Reproductive Empowerment framework. Figure 3 provides a high-level summary of the studies by these self-care and reproductive empowerment constructs (individual studies are identified by reference number printed within the circle). All but one study focused on use of contraceptive self-care and, therefore, we further divided these studies into those which measured intention to use (n = 8) and those which measured actual use of contraceptive self-care (n = 28). Two studies measured both use and intention to use condoms.21,42 Only one study measured access to contraceptive self-care and none of the studies measured acceptability.26 Regarding reproductive empowerment, eight studies measured individual agency constructs. The majority (29 of the 37) of studies examined immediate relational agency constructs. After reviewing the specific measures used within the immediate relational agency studies, we thematically grouped the studies by whether their empowerment measure focused on agency pertaining to (1) negotiation about contraceptive method use with partners or sexual negotiation with partners (n = 22) or (2) intimate partner violence (n = 7). The remaining eight studies measured individual agency constructs; no studies reported results across more than one empowerment construct. In Figure 3, we represent each study that measured a specific type of contraceptive self-care with a circle; five studies have more than one circle because they measured more than one type.

Figure 3.

Summary of the relationships between contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment constructs

Each colour of the circles in Figure 3 indicates whether the relationship reported in the studies was favourable, unfavourable or null. Dark blue indicates that a favourable relationship was reported between contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment (i.e. greater empowerment was associated with greater access/acceptability/use/intention to use self-care), whereas dark orange indicates that an unfavourable relationship was reported (i.e. greater empowerment was associated with lower access/acceptability/use/intention to use self-care). If the relationship between contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment was not significant, we indicate the null results with the lightest blue. Since some studies conducted more than one analysis of the relationship between self-care and empowerment, they could have found mixed results. The middle shade of blue denotes studies that reported both null and favourable results. Yellow is used for studies that reported both null and unfavourable results. No studies reported a mix of favourable and unfavourable results.

Individual agency

Eight studies measured reproductive empowerment constructs related to individual agency, three of which measured its relationship with condoms only,20–22 and five measured a relationship with types of contraceptive self-care methods other than condoms.23–26,57 This latter group included two studies of different client-facing digital technologies offering interactive decision support tools to provide contraceptive education and elicit users’ preferences for contraception.24,25 Two other studies in this group examined the relationship between individual agency empowerment constructs and OCPs26 and EC.23 The final study in this group, an online global values, and preferences survey conducted by WHO in 2019,57 measured the perceptions of health care providers and “lay people” on whether empowerment is a top reason for using a variety of family planning methods, as well as their perceptions of whether empowerment is a benefit of using family planning. Respondents were asked about the following types of contraceptive self-care: OCPs, EC, patch, vaginal ring, self-injection of subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA-SC), diaphragm, and client-facing digital technologies.

Half of the studies measured intention to use contraceptive self-care. Three studies, including both studies of digital technologies, measured contraception use.22,24,25 One study measured access to contraceptive self-care, though it measured hypothetical access to over-the-counter OCPs.26

The individual agency empowerment constructs measured across the studies varied (Table 3). Three studies included multi-itemed scales with high internal consistency measuring general self-efficacy,20 self-esteem,22 and condom use self-efficacy.21 One study24 measured decision quality using the multi-item Decisional Conflict Scale.58 Three qualitative studies reported respondents’ single- or double-item empowerment statements such as feeling “empowered,” “in control,” or “prepared.”23,25,26 WHO’s 2019 online survey measured respondents’ perceptions on family planning methods and empowerment by asking respondents two questions about potential method attributes using response options such as “access,” “convenience,” “privacy and confidentiality,” and “empowerment.”57

Table 3.

Measures of reproductive empowerment and related constructs

| Measure | Description | Number of Items (Number and Names of Subscales) | Response Options | Example Item | Internal Consistency* | Studies | Reference for Original Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condom Use Self-Efficacy Scale (CUSES) | Asses self-efficacy to use condoms and negotiate condom use with partners | Original: 14 (4: Assertiveness, Partner’s Disapproval, Mechanics, Intoxicants) Gesselman, et al. abbreviated version: 4, unidimensional Sousa, et al. adaptation for Brazilian context: 14 (3: Communication, Consistent Use, Correct Use) Santos, et al. adaptation for Brazilian context: 15 (NR) |

Five-point Likert-type | “If I were unsure of my partner’s feelings about using condoms, I would not suggest using one.” | Original scale: Excellent for overall scale (Thomas, et al.: α = 0.90); excellent to good for each subscale (Asante: α = 0.81–0.90) Adaptations for Brazilian context: Good (Santos, et al.: α = 0.86; Sousa, et al: α = 0.85) |

Original version: Thomas et al.42; Davis51; Asante et al.28. Adaptations for Brazilian context: Santos, et al.37; Sousa, et al.40 Abbreviated version: Gesselman, et al.33 |

59 |

| Decisional Conflict Scale | Assesses awareness of available options and perceived ability to make an informed choice | 16 (5: Informed Decision, Uncertainty, Effective Decision, Values Clarity, Support) | Five-point Likert-type | “I am clear about which benefits matter most to me.” | NR | Dehlendorf, et al.24 | 58 |

| Condom Self-Efficacy | Assess confidence in using condoms, similar to CUSES Mechanics and Assertiveness subscales | 15 | Five-point Likert-type | NR | Good (α = 0.84) | Tsay, et al.44 | NA |

| Partner Risk Reduction Self-Efficacy | Assess perceived ability to change sex behaviour within relationship | 4 | Five-point Likert-type | “Would you be able to avoid sex any time you didn’t want it?” | Acceptable (α = 0.73) | Chirinda, et al.30 | 60 |

| Relationship Control | Assess perceived control in relationship | 4 | Four-point Likert-type | “Your partner has more control than you do in important decisions that affect your relationship.” | Good (α = 0.81) | Chirinda, et al.30 | 61 |

| HIV Attitudes Scale, condom use self-efficacy subscale | Assess confidence to negotiate and use condoms | Three-item subscale | Four-point Likert-type response | “If my partner would want to have sex without a condom, I would try to convince her/him to use it.” | Acceptable (α = 0.76) | Espada, et al.21 | 62 |

| Minnesota Student Survey, self-esteem subscale | Assess self-esteem | Four-item subscale | Four-point Likert-type | “I usually feel good about myself.” | Good (α = 0.89) | Ghobadzadeh, et al.22 | NA |

| Partner Communication Self-Efficacy | Assess perceived difficulty of talking with sexual partner about condom use and other risk behaviours | 6 | Five-point Likert-type | “How hard is it for you to refuse to have sex if he won’t wear a condom?” | Good (α = 0.82) | Ritchwood, et al.36 | 63 |