Abstract

Écriture inclusive (EI) has long been the topic of public debates in France. These debates have become more intense in recent years, often focusing on the higher education system and culminating in the formulation of three separate laws banning it for public administration. In this paper, we investigate the foundations of these conflicts through a large quantitative corpus study of the (non)use of EI in Parisian undergraduate brochures. Our results suggest that Parisian university professors use EI not only to ensure gender neutral reference but also as a tool to construct their political identities. We show that both the use of EI and its particular forms are conditioned by how brochure writers position themselves on non gender‐related‐related issues within the French university's political landscape, which explains how conflicts surrounding a linguistic practice have become understood as conflicts about larger issues in French society. Our paper thus provides new information to be taken into account in the formulation and promotion of nonsexist language policies and sheds light on how feminist linguistic activism and its opposition are deeply intertwined with other kinds of social activism in present‐day France.

Keywords: France, French, inclusive writing, political ideology, prestige, quantitative study

Abstraite

L'écriture inclusive (EI) fait depuis longtemps l'objet de débats publics en France. Ces débats, devenus plus intenses ces dernières années, se sont souvent concentrés autour de l'éducation supérieure et ont mené à la formulation de trois lois proscrivant l'EI pour les administrations. Dans cet article, nous analysons les raisons de ces conflits en présentant une étude de corpus quantitative sur l'utilisation ou la non‐utilisation de l'EI dans les brochures de licence des universités parisiennes. Nos résultats montrent que les enseignants et enseignantes des universités parisiennes utilisent l'EI non seulement pour marquer une référence générale (neutre au niveau du genre), mais aussi pour construire leur identité politique. À travers cette étude, nous montrons que l'utilisation de l'EI et de ses formes est déterminée par le positionnement des personnes écrivant les brochures sur les problématiques non liées au genre dans le paysage politique des universités parisiennes. Notre article donne ainsi de nouvelles informations dont il faut tenir compte pour la formulation et la promotion des politiques linguistiques non sexistes, et met en lumière comment le militantisme linguistique féministe est profondément lié à d'autres formes de militantisme social dans la France actuelle.

1. INTRODUCTION

This article presents a corpus study of écriture inclusive in Parisian universities. The expression écriture inclusive (EI), lit. ‘inclusive writing’, has been used to refer to feminist language practices consisting of a wide variety of orthographic and discursive practices in France and across the Francophonie (see Abbou et al., 2018; Vachon L'Heureux, 1992; Vachon‐L'Heureux et al., 2007, for discussion). In this paper, we use it to refer to a set of spellings that indicate inclusive or gender neutral reference, particularly as a way of shortening expressions like les étudiants et étudiantes ‘the studentsM and the studentsF’. This set includes the point médian ‘interpunct’ (les étudiant·e·s), the period (étudiant.e.s), the parenthesis (étudiant(e)s), the hyphen (étudiant‐e‐s), and the capital (étudiantEs), among others.

Feminist language practices have a long history and are common crosslinguistically (see Hellinger & Motschenbacher, 2002; Sczesny et al., 2016). Although feminists have been working on changing their language since at least the 12th century (Weatherall, 2002), how language creates and sustains gender inequality has been a major focus for scholars and activists in the anglophone world, in francophone Canada, and in Sweden since the 1970s (see Pauwels, 1998 for English, see Vachon‐L'Heureux, 1992; Arbour et al., 2014 for French Canada, and Hornscheidt, 2003 for Swedish) and since the 1980s and 1990s in countries such as Germany (Bussmann, 2003; Guentherodt et al., 1980), Belgium (Arbour et al., 2014), and France (Burr, 2003; Houdebine, 1998; Yaguello, 1979, among others). One of the main problems that most feminist language practices address is linguistic androcentrism (Cameron, 1985; Hellinger & Motschenbacher, 2002; Mucchi‐Faina, 2005; Pauwels, 1998; Sczesny et al., 2016), especially the use of grammatically masculine words or words containing male morphology to refer to women, mixed groups, or generic humans. Since the 1970s, a wealth of psycholinguistic studies, beginning with Kidd (1971), Bem and Bem (1973), Schneider and Hacker (1973), Soto and Cole (1975), and Pincus and Pincus (1980), has shown that English speakers do not interpret words with male denoting morphology (such as chairman and fireman) or masculine pronouns (he, him, his) as completely gender neutral, even in a context in which gender neutrality is suggested, such as Every chairman brought his mallet to the meeting. Rather, English sentences with masculine marking have an interpretative bias that makes anglophones highly likely to interpret them as referring to men.

Psycholinguistic research on the interpretation of gender marking in French is much more recent (see Gygax et al., 2013, for an overview). However, confirming literary and grammatical studies going back to Beauvoir (1949) and Yaguello (1979), Houdebine (1987), and Michard (1996), a large and growing body of work on this language has shown that French behaves similarly to English: It is almost impossible to refer both men and women in an equal way by using a masculine marked expression (Brauer & Landry, 2008; Chatard et al., 2005; Gabriel et al., 2008; Garnham et al., 2012; Gygax et al., 2008, 2012, 2019, among many others). Grammatically masculine noun phrases have an interpretative bias in favor of men that goes above and beyond the particular stereotypes associated with the noun. The goal of EI is therefore to force reference to both men and women (and sometimes people of other genders), thereby eliminating, or at least reducing, linguistic androcentrism.

Furthermore, given that the use of masculine grammatical gender with human nouns creates a male‐biased interpretation, there is reason to believe that, through this bias, such language plays a role in the underrepresentation of women in positions of power in society (see Sczesny et al., 2016; Stahlberg et al., 2007, for reviews of the literature on this question). The link between linguistic androcentrism and gender inequality has been well documented from an experimental perspective. For example, studies on both French (Brauer & Landry, 2008) and German (Stahlberg et al., 2001) have shown that participants are more likely to think of women as successful politicians when presented with a gender inclusive form, rather than a masculine form. Likewise, studies on English (Ng, 2007; Stout & Dasgupta, 2011), Dutch, and German (Vervecken & Hannover, 2015; Vervecken et al., 2013) have shown that using masculine language instead of gender inclusive language in job ads and descriptions creates more negative emotions and a lower sense of efficacy in female adults and children. In the case of job ads, this even results in less motivation for applying to the position. Therefore, through how it counters linguistic androcentrism, users of EI aim to eliminate, or at least reduce, the contribution that language makes to the introduction and reproduction of gender inequality in francophone societies.

As with most language policies aimed at addressing gender inequality, EI has been very controversial. This linguistic practice has given rise to debates between and within groups of feminists and antifeminists concerning whether EI should be used and, if so, which form should be preferred. In this paper, we focus on these debates in France, where they have become extremely virulent. The most recent phase of social conflict surrounding gender inclusive writing in France began in 2017, when, in March of that year, the scholastic publisher Hatier published an elementary school social science textbook (CE2 level: 8–9 years old) which had many occurrences of EI using the period. For example, the textbook had chapter names such as Les agriculteur.rice.s au fil du temps, Les savant.e.s au fil du temps, and Les puissant.e.s au fil du temps ‘The farmers/intellectuals/powerful ones throughout the ages’. This textbook was discovered by the right wing press in the fall through a short article in Le Figaro by Marie Estelle Puech, 1 published on 22 September 2017. Puech criticized the use of EI with the period and announced that the publisher was further considering publishing a guide to EI favoring the point médian. Puech's article sparked a period of intense public discussion surrounding gender inclusive language: the Académie Française called EI a péril mortel ‘mortal peril’ for the French language, 2 and the education minister, Jean‐Michel Blanquer, stated that EI wasn't necessary, because ‘la France a comme emblème une femme: Marianne; l'un de ses plus beaux mots est féminin: la République’. 3 In the same statement, Blanquer claimed that the French language has ‘qu'une seule grammaire’ ‘only one grammar’, suggesting that EI goes against the universality of the French language, one of the principles of the French Republic enshrined in article 2 of the French constitution. 4 There were also rejoinders from the pro‐EI side, such as the tribune in Slate on 7 November, signed by 300 elementary, high school, and university teachers. 5 Note that while Hatier's manual uses EI with the period, and Puech's article accurately describes them as doing so, the form of EI that was most frequently at issue in articles and speeches at this time was, in fact, the point médian. The debate focused so much on the point médian that journalists were often unaware that the original scandal was about EI using the period. For example, a pro‐EI article appearing in the left‐wing newspaper Libération 6 reports Hatier as using the forms agriculteur·rice·s and artisan·e·s, rather than agriculteur.rice.s and artisan.e.s which appear in the text.

Finally, to clarify the government's position on this matter, the Prime Minister, Edouard Philippe, issued an official statement (circulaire) on 22 November, stating that gender inclusive/neutral reference should be accomplished using the repetition kind of EI (le ou la candidate ‘theM or theF candidate’) in official texts, outlawing any composite forms. 7

Since 2017, the political dimensions of the conflict surrounding gender inclusive writing in France have continued to grow. In July 2020, deputees from the French National Assembly, majoritarily from the extreme right‐wing party, proposed a law prohibiting ‘toute personne morale publique ou privée bénéficiant d'une subvention publique’ 8 from using EI. Then, in February 2021, deputees from the governing centrist party proposed a second law prohibiting ‘les personnes morales en charge d'une mission de service public’ 9 from using this feminist practice. 10 This proposal was followed up by another one in March 2021 11 imposing harsher penalties. Thus, at the time of writing, France currently has three different pending legal proposals to ban most forms of EI in administrations and intense public debates that surround them.

The way that opposition to gender inclusive writing has been gaining visibility and government support in recent years makes France stand alone, at least compared to other countries in Europe and in North America. 12 As discussed above, governments in these other countries have increased official support of inclusive writing through time, not forbidden it. This includes countries like Canada, whose official languages are French and English. As discussed by Vachon‐L'Heureux (1992); Arbour et al. (2014), among others, gender inclusive writing was introduced in francophone Canada in the 1970s in order to satisfy a new requirement imposed by the national work and immigration department that job ads be gender neutral in both official languages. Unlike in France, not only has EI never been officially outlawed in French Canada, such policies have been greatly expanded throughout the years within the context of national and provincial government agencies (see Ontario College of Teachers, 2005, for a summary). The sharp contrast between France and French Canada (among other places) raises the sociolinguistic question of why official opposition to gender inclusive writing seems to be growing in France, while it is fading elsewhere.

In order to answer this question, we first need to know more about EI as a linguistic phenomenon. Despite how frequently it is discussed by politicians and in the media, we actually have very little corpus or experimental data on how speakers and writers of French use écriture inclusive. This paper therefore contributes to filling this empirical gap by presenting a large quantitative corpus study of the (non)use of EI in Parisian university brochures in 2019/2020.

We believe that studying university brochures will allow us get a handle on the source(s) of the political conflicts surrounding French gender inclusive writing. This is because, as mentioned above, both opposition to and support of EI largely turns around its place in the education system. Thus, we need to understand why education occupies such a privileged place in current conflicts in France (rather than, e.g. employment or some other domain where there is gender inequality). Concern about the language used by educators also feeds into another concern about the source of gender inclusive writing. One of the main discourses advanced by opponents of EI is that it has been developed and is promoted by university professors, which (according to this view) makes it elitist. This idea was recently articulated by the Culture Minister 13 and features prominently in the most recent legal proposal to ban EI. 14 Proponents of this law link the claimed elitism of EI to cultural ‘separatism’, something that goes against Universality, one of the values of the French Republic. 15 We therefore think that a corpus study of university brochures is the perfect entry point into this complex sociolinguistic phenomenon.

In line with work on gender inclusive language in other countries, the results of our study suggest that people who work in the Parisian universities do use EI as a way to address the linguistic androcentrism and gender‐equality problems discussed above. However, we also argue that the quantitative patterns we find reveal that the (non)use of EI has another important function: the construction of a political identity. In particular, we find that both the use of EI and the particular forms employed are conditioned by factors related to the writers orientations within the French university's political landscape on issues that do not, at least ostensibly, have to do with gender. We argue that the political conflicts surrounding EI turn around these political associations and their perceived consequences for French education and French society.

Previous studies on the use of masculine versus feminine marking in expressions referring to women in Polish and French have shown that speakers' political orientations, either generally (conservative versus. progressive, Formanowicz et al., 2013) or on a particular issue (like gender quotas in politics, Burnett & Bonami, 2019) can influence how they interpret and use gender marking. Likewise, a study on Polish and German (Formanowicz et al., 2015) has shown that use of feminine forms rather than ‘generic’ masculines can affect how political initiatives themselves are perceived. This article furthers our understanding of the relation between language, gender and politics, through studying (as we will see) an eight‐way system (masculine versus. seven inclusive forms). We will see that this much richer social signaling system allows for the construction of a wider range of political identities, and members of the Parisian university community make full use of this increased expressive power to navigate the broader social conflicts that EI has become associated with. More generally, we believe that our paper provides valuable information for individuals who wish to formulate and apply language policies promoting gender equality and sheds a light on how both feminist linguistic activism and its opposition can be deeply intertwined with other kinds of social activism.

The paper is organized as follows: In section 2, we review the previous corpus work on écriture inclusive. As far as we can see, the only research on EI from this perspective is Abbou (2011, 2017)'s study of EI in anarchist brochures. We describe Abbou's results and discuss what (if any) predictions can be made for EI in a university context. Then, in Section 3, we present the methodology of our study of EI in the brochures de licence ‘undergraduate brochures’ of 12 Parisian universities. We describe the constitution of our corpus and the extraction and coding of the data. In Section 4, we present our results. We show that there exist strong differences in both the use (versus. non‐use) of EI across universities and academic disciplines and that the choice of whether to use EI is conditioned by gender balance of the discipline/university but also ideological properties like university/discipline prestige and political activism. Likewise, we show that, within the academic departments that use EI, prestige and activism also play a role conditioning which particular form is used. Finally, in Section 5, we discuss the implications of our results for understanding the current political debates surrounding EI, as well as for language policy.

2. PREVIOUS CORPUS WORK ON EI

To our knowledge, the only previous work on variation in écriture inclusive is by Julie Abbou (2011, 2017), who studied the ‘perturbations de genre’ ‘gender perturbations’ in anarchist pamphlets from 1990 to 2008. Abbou examined 280 pamphlets and found that over a third had some form of feminization or what she calls the double marquage du genre ‘double gender marking’, that is, what we have been calling the composite forms of écriture inclusive. She observes, however, that feminization/EI is not equally frequent: In the 1990s, less than a third of the texts in her corpus contain some feminization or EI; however, starting in the year 2000, the rate rises greatly and even attains almost 80% or 90% in some of the later years.

To get a more detailed look at EI in an anarchist context, Abbou did a qualitative analysis of 6 brochures containing 15 texts. Her first result concerns the wide range of variation in the forms of EI found this corpus. She finds all the forms shown in Table 1; however, the most frequent variants are the hyphen and the capital. Most of the forms involve using some punctuation to make a composite representation of the masculine and feminine forms, resulting in a form that has no obvious pronunciation.

TABLE 1.

| Form | Example |

|---|---|

| Hyphen | étudiant‐e‐s |

| Period | étudiant.e.s |

| Point médian | étudiant·e·s |

| Capital | étudiantEs |

| Underlining | étudiantes |

| Long forms | locuteurices |

| Repetition | étudiantes et étudiants; locuteurs, locutrices |

| Slash | étudiants/étudiantes, locuteurs/ices |

In order to develop an understanding of the choices that underlay the patterns of variation that she found, Abbou conducted interviews with writers from the corpus, asking why they use the forms that they do. As is common in verbal hygiene discourses (see Cameron, 2012), the writers' reasons for preferring one variant of EI over another included a mixture of practical and esthetic considerations. One of the most important aspects that determine the use of different forms of EI, according to Abbou's participants, is what she calls the ‘sémiotique politique de la typographie’ ‘the political semiotics of the typography’ or what, in this paper, we will call its social meaning. For the anarchists interviewed by Abbou, some variants of EI signal something about the political views of their users, in addition to their views about gender. The two variants that the anarchists comment on in the interviews are the parenthesis and the capital.

As explained in Abbou (2017, p. 65), the anarchists find the parenthesis unacceptable because it signals a pro‐government, pro‐institutional stance. For example, speaker E says that ‘la parenthèse pour moi c'est un peu associé aux formulaires euh style France Télécom ou l'État français qui t'envoie un truc et qui dit cher client cher clienTE et maintenant au lieu [… ] il mettent cher client[(e)]’ 16 (E65). This quotation also shows that repetition shares this social meaning. According to E, the parenthesis is used by nonactivists, and it can even go as far as signaling that the writer is right wing. Undoubtedly, both repetition and the parenthesis have acquired these social meanings because they have traditionally been the means through which the French state and its dependents have been gender inclusive. One of the most famous early examples of inclusive language is General de Gaulle's use of repetition in his first speech upon his return to politics in 1958: ‘Françaises, Français, aidez‐moi’!. 17 Although more recent than repetition, the parenthesis is also featured in reformist feminist texts supported by the government, such as the 1998 official guidelines for feminization: Femme, j'écris ton nom (Becquer et al., 1999). Thus, given their social meaning associated with older, governmental institutions, it is understandable that anarchists would avoid these variants.

The capital variant has no particular association with the French state, but it is disfavored by the anarchists for different reasons. As Abbou mentions, her interviewees dislike the capital because they perceive it as having a social meaning that goes counter the radical political project of gender deconstruction in which they are engaged. As Abbou says (p. 65), the capital would be in line with differentialist feminism, now considered outdated.

2.1. From anarchists to university professors

Abbou shows that for anarchists in the 2000s, not all variants of EI are equal: The people she interviewed preferred the hyphen and the period for readability reasons and also because these variants were not associated with any social meanings that the feminist anarchists found objectional, such as having a pro‐institutional or pro‐gender binary/hierarchy stance. The study that we will present in the next section asks the same questions as Abbou but in a very different temporal and social context. Therefore, we wonder to what extent the patterns Abbou found might carry over to university brochures in 2019 and 2020.

On the one hand, we expect that there will be very many differences: Our study looks at texts produced over a decade later, which were written after EI when the point médian suddenly became very salient in the French media in 2017. Our study is also drastically different from Abbou's since we are studying university undergraduate program brochures, not anarchist ones. Obviously, we should expect university professors to have less of an anti‐institutional stance, since universities are integral parts of the state's educational institution, and those who work there are participating in this institution. On the other hand, French universities are also sites of political and social conflict, and university faculty often participate in these conflicts. There is a long history of left‐wing activism in Parisian universities, the most famous example being the student riots in May 1968. There is also a long history of right wing activism in Parisian universities, with the activities of the Groupe union défense ‘Union defense group’ (GUD), an extreme right‐wing student organization, active predominantly at Université Paris 2‐Assas and Université Paris 10‐Nanterre in the 1970s to 1990s. Recent years have seen both kinds of activism continue: For example, the 2018 left‐wing student protests against the university selection process (Parcoursup), student and faculty protests against proposed pension and research reforms (loi LPPR) in 2019–2020, and the reconsolidation of extreme right wing student groups at Paris 2‐Assas in 2011 (GUD) and 2017 (Bastion Social ‘Social bastion’). Abbou shows that the anarchists' use of écriture inclusive played a role in constructing a right wing versus left‐wing identity, so EI in Parisian universities may likewise be sensitive to this salient political distinction.

Another difference between the anarchist context and the university context is that language in official university publications is much more regulated. This being said, when it comes to gender inclusive language, the official regulations are not uniform across the Parisian universities. Champeil‐Desplats (2019) reviews the state of EI in legal and administrative contexts. She makes a distinction between universities, like Paris 10‐Nanterre, who have taken major administrative action to promote EI (such as having a service devoted to gender equality whose official position is pro‐EI) and other universities who take the directly opposite position and forbid it. The clearest case of such a university is Université Paris 2‐Assas, whose president sent an email (cited in Champeil‐Desplats, 2019) to all administrative staff on 17 December 2018, reminding that EI should not be used since it goes against the orthographic rules. These examples show that EI may be sensitive to similar dimensions in the current university context as in Abbou's anarchist context over 10 years ago. In this email, the president's office of Université Paris 2 makes a clear link between the (non)use of EI and the university's image, suggesting that EI also has an identity constructing function in the university context. Likewise, Champeil‐Desplats attributes the recent rise in EI in the French university to another recent political conflict: the left‐wing movement against Parcoursup in 2018. Very broadly speaking, Parcoursup is an initiative by the Macron government to institute a particular selection process in French universities. This initiative was highly controversial and was met with anger, blockades, and strikes from left‐wing student and faculty activists, who hold the view that universities should be open to all students with high school diplomas. The conflicts surrounding Parcoursup are about education and economic policy, not gender; therefore, the existence of a link between protests about Parcoursup and EI suggests that, as with anarchists, the social meaning(s) of EI in the university could be related to left versus right, pro‐government vs anti‐government stances.

To further explore these questions, we turn to our study of écriture inclusive in Parisian university brochures.

3. EI IN UNDERGRADUATE BROCHURES: METHODOLOGY

3.1. Corpus constitution

As explained in the previous section, Parisian universities have a long history of different activism and occupy a special place in public discourses about EI. We constituted a corpus by collecting all undergraduate (licence) brochures available online in the 12 main Parisian universities (resulting from the 1970 scission of the Université de Paris) between August 2019 and February 2020. For our study, we selected undergraduate brochures because they are the documents that give us the most uniform coverage across the Parisian universities with respect to discipline. Since there are more undergraduate programs than graduate programs, studying undergraduate brochures provides us the most complete picture of use EI is used (or not used) in Parisian higher education. We also chose to study brochures because their function is to lay out the educational training program provided by the department. Because of this, they can be considered pedagogical actions, in the sense of Bourdieu and Passeron (1970), which give them a special role in the education system (to be described below). Although there may be punctual exceptions, brochures are generally written by departmental committees composed of faculty members, and they are generally published on the department's website. We chose to focus on brochures exclusively from universities and exclusively from Paris for practical reasons: The scission of the Université de Paris at the beginning of the 1970s groups the 12 universities that we studied together in a socially important, self‐contained class as the heart of the Parisian (and also French) university system, and, as we will see, the size of the dataset that results from the corpus deliminated in this way is optimal for the mixture of automatic and manual coding that we had to do for the quantitative study. In the future, it would be desirable to see how EI is realized in universities outside Paris, as well as in other kinds of institutions of higher education within Paris, such as the public grandes écoles (École Normale Supérieure, Paris, Polytechnique, etc.) and private institutions like Epitech, Institut supérieur de gestion etc.

The list of the universities whose undergraduate brochures make up our corpus is shown in (1) (more information about the criteria can be found in an OSF (Foster & Deardorff, 2017) repository (https://osf.io/wsdqx/)).

(1)

Université Panthéon‐Sorbonne (Paris 1)

Université Panthéon‐Assas (Paris 2)

Université Sorbonne‐Nouvelle (Paris 3)

Sorbonne Université, product of the merger of Paris‐Sorbonne (Paris 4) and Pierre‐et‐Marie‐Curie (Paris 6)

Université Paris‐Descartes (Paris 5)

Université Paris‐Diderot (Paris 7)

Université Vincennes Saint‐Denis (Paris 8)

Université Paris‐Dauphine (Paris 9)

Université Paris‐Nanterre (Paris 10)

Université Paris‐Sud (Paris 11)

Université Paris‐Est Créteil (Paris 12)

Université Sorbonne Paris‐Nord (Paris 13)

3.2. Data extraction

Although in the future it would be desirable to do a study of EI with all nouns in the corpus, in this paper, we present the results of variation in EI with the most frequent relevant noun: étudiant ‘student’. We used the Antconc software (Anthony, 2004) to extract all occurrences of the word étudiant from the 871 brochures. We searched for étudiant* and étudiant* (html symbol). We found in total 20,810 occurrences (after cleaning). Some occurrences were adjectives (vie étudiante ‘student life’, public étudiant ‘student audience’) or present participles (étudiant le rôle de la philosophie… ‘studying the role of philosophy’). We only retained nouns (i.e. words with gender neutral reference) for analysis, which left us with 19,343 occurrences and 810 brochures. The whole corpus and the annotation files are available on OSF.

The first observation about our corpus one can make is that the number of files per university is uneven (the exact numbers by university are available on OSF). The most likely explanation for this is that universities differ in size (Paris 2 being a rather small university focusing on law and economics compared to Paris 4–6 which results from a fusion of two universities). We then decided to take the brochures as a random variable in our inferential analysis since the unequal number of brochures per university could hide some results and effects.

4. EI IN UNDERGRADUATE BROCHURES: RESULTS

We separate our results into two categories: (1) factors conditioning the use or avoidance of any form of écriture inclusive and (2) factors conditioning which form of EI is used.

4.1. (Non) Use of écriture inclusive

4.1.1. Descriptive results

Out of 19,343 occurrences, 3,188 (16.48%) were inclusive forms. Figure 1 presents the distribution of EI among the 12 Parisian universities and highlights the variation between them. It shows that some universities do not have inclusive forms at all like Paris 2, Paris 9, and Paris 11. Also, we can see that EI is not predominant in any university and its rate always remains less than 50%. The universities with the highest rates of EI are Paris 3, Paris 4 and 6, Paris 13, and Paris 8.

FIGURE 1.

Écriture inclusive by university

Figure 2 shows the distribution of EI among the different academic domains according to the ONISEP website. 18 Looking at the results, we can see that there is also variation between the different domains, with barely any EI in medicine (Études Médicales) and economics/management (Économie et Gestion) compared to literature and languages (Lettres et Langues) and humanities and social sciences (Sciences Humaines et Sociales). More data on academic disciplines are available on OSF.

FIGURE 2.

Écriture inclusive by academic domain

4.1.2. Factors and hypotheses

The figures presented above show that there exists an enormous amount of variation in our corpus and that this variation can be observed both by looking across university and across academic domain. What drives this variation? Based on what we outlined in Section 1, we can formulate two hypotheses:

a. EI to address linguistic androcentrism. A first hypothesis would be that writers of the university brochures are using EI to address linguistic androcentrism: Since masculine marked noun phrases have a male bias in their interpretation, their use in disciplines where there is gender parity (or a female majority) would be particularly at odds with scholastic guidelines written in the masculine.

To test the effect of parity on EI use, we took faculty parity to represent gender parity in the statistical analysis; that is the proportions of men/women from the CNU section from 2012/2013 (DGRH A1‐1, Gesup 2013). One reason for choosing this variable is that the CNU sections are associated with individual academic disciplines (more explanations regarding this choice are available on OSF).

b. EI as identity construction. The reference that the president's office of Paris 2 makes to the ‘image’ of the university being damaged by the use of EI strongly suggests that inclusive writing has social meaning for French academics. One obvious way that that EI could be related to the image of the universities that employ it comes from the relationship between the use of ‘generic’ masculines and professional prestige. Although the debates surrounding EI are more recent, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, there were equally large public debates concerning the use of feminine marking on professional noun phrases referring to women (e.g. la ministre, la professeure, la médecin) (see Burnett & Bonami, 2019; Burr, 2003; Cerquiglini, 2018; Houdebine, 1987, 1998; Viennot, 2014, among others). For some women, one of the main reasons they prefer to be referred to in the masculine (e.g. le ministre, le professeur, and le médecin) is that they have the impression that the masculine forms have a more prestigious connotation than the feminine ones. In fact, the idea that masculines as associated with higher prestige than feminines has been investigated (and partially verified) by Dawes (2003) for French and Merkel et al. (2012) for Italian. Given that the idea that masculine marking applied to women confers more prestige onto them was a major discourse in the debates surrounding la féminization des noms de métiers et de fonction (Cerquiglini, 2018; Houdebine, 1998), it would not be surprising if French speakers continue to associate ‘generic’ masculines with higher prestige 20 years later. We might therefore hypothesize that universities (and perhaps departments) that wish to present a more prestigious image should use less EI.

Our second set of identity construction related hypotheses concern the construction of left/right‐wing, antigovernment/progovernment stances. Recall that Abbou's anarchists saw use of EI as being part of their activism; therefore, if EI is playing a similar role in Parisian universities, we predict that professors in more left‐wing activist universities should use more EI. The link that Champeil‐Desplats draws between the rise of EI and protests against university selection (Parcousup) in 2018 further strengthens the hypothesis that university faculty will use EI to signal an anti‐Macron government stance.

Prestige and anti‐government stance or left‐wing activism are complex notions, and it is not immediately obvious how to operationalize them in a corpus study such as ours. A full discussion of the different measures of university prestige that we explored is given on OSF. The factors encoding prestige and activism that we use in our statistical analysis comes from a measure that aims to tap into French speakers' commonsense notion of prestige and activism: We set up a survey on the Ibex platform (Drummond, 2017) to ask the opinion of French speakers about the Parisian universities. We asked 79 participants whether they knew the university logo taken from each university's Wikipedia website. Participants were recruited via the RISC (a crowdsourcing platform in France https://www.risc.cnrs.fr/) and social media. Participants who took part in the study come from different backgrounds. Most of them work or study in a university but not necessarily in a Parisian university. There were answers indicating that some universities were not known by all participants. We only took in our analysis responses from participants who said they knew the university (cf. the OSF repository). They then had to rate on an 11‐point level slider whether they thought the university was prestigious and activist. 19

Results showed that the two measures are strongly correlated (pearson, r = −0.5): The more prestigious a university was judged, the less participants judged it to be activist. This shows that, when it comes to Parisian universities, prestige and activism are not independent; rather, they could be interpreted as flip sides of an ideological coin. Because of this correlation, we will only include the prestige measure in the statistical analysis. However, one should keep in mind that positive results for prestige are rather negative results for activism, and vice versa.

4.1.3. Analysis

Method of analysis

For our paper, we ran Bayesian binomial regression models for all analyses. For clarity purposes, we will only report and explain the strong effects in the results section. For a detailed account of the Bayesian statistical analyses and an explanation as to why we chose Bayesian analyses with, see the OSF repository.

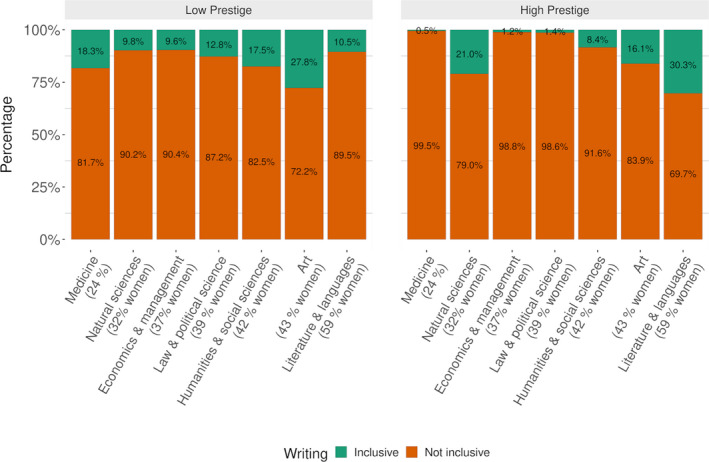

Results. Figure 3 shows the proportions of EI depending. Figure 4 shows the EI use by academic domain in more/less prestigious universities (median split 20 ). On the x‐axis, the academic domains range from male‐dominated disciplines (with a low proportion of women, e.g. Medicine) to female‐dominated disciplines (with a higher proportion of women, e.g. Literature and Language). For clarity purposes, raw numbers for all figures in the paper are available on OSF.

FIGURE 3.

Proportions of écriture inclusive (EI) use by university prestige (left) and by faculty parity (right)

FIGURE 4.

Proportions of écriture inclusive (EI) use by academic domain in more/less prestigious universities (median split)

As can be seen and as confirmed by the statistical analysis, we found effects of prestige and parity on the use of EI. More precisely, less EI was used when the university prestige was higher. Also, more EI was used when parity increased. There was also an effect of the interaction between prestige and parity: The higher the prestige, the higher the difference between male‐dominated and female‐dominated disciplines regarding the use of EI. This can be interpreted as follows: in prestigious universities, EI is more used in female‐dominated than in male‐dominated disciplines, whereas the opposition between female‐and male‐dominated disciplines with regards to EI use is less visible in less prestigious universities.

4.1.4. Discussion

Our results show the main factors that we identified: gender parity and prestige/activism condition the use of EI.

The main effect of gender parity supports the idea that brochure writers are using EI as a way to compensate for the male bias in masculine marked expressions: The more female faculty members a department has, the more inclusive forms will be found in their brochure. Since faculty gender balance and student gender balance are correlated (see OSF repository for more details), use of an inclusive form of étudiant also increases as the proportion of female students increases.

However, addressing linguistic androcentrism is clearly not the only motivation for using or avoiding écriture inclusive. University prestige and activism also have an effect: more prestigious universities, which are less activist, use more masculine forms than less prestigious universities, who are more likely to have a culture of left‐wing and anti‐Macron government activism. We know from the debates on la féminisation des noms de métiers et de fonctions in the late 20th century that (extreme use of) ‘generic’ masculines are ideologically associated with prestige and a previous era when the university was more male‐dominated than it is now. We therefore propose that it is this conservative, pro‐institution social meaning that makes professors in more prestigious universities strongly favor ‘generic’ masculines. This could also be related to the prestige associated with the different disciplines taught in universities and the proportion of women in these disciplines: More prestigious universities would offer more prestigious disciplines leading to a higher attendance of men, thus favoring ‘generic’ masculines. However, at this stage, our corpus results cannot dissociate university prestige from discipline prestige, and this should be tested in another study with more variables.

Another piece of data that supports this analysis is the interaction between gender parity and university prestige described in the results section and shown in Figure 4. The interaction signifies that gender parity plays a different role with respect to écriture inclusive in more prestigious versus less prestigious universities. More specifically, gender parity has a stronger effect on EI in prestigious universities: While rates of EI are relatively similar across academic domains in less prestigious universities, male‐dominated domains in prestigious universities use less EI compared to domains with better gender balance.

If ‘generic’ masculines have social meaning related to prestige and male domination, it makes sense that professors in male‐dominated disciplines, which are often themselves the most prestigious (see Leslie et al., 2015, among others), in prestigious universities would find masculines particularly useful for reproducing these aspects of their academic culture.

4.2. Use of the different forms of EI

4.2.1. Descriptive results

Consistent with Abbou's results, our study reveals a large plurality of forms of EI: the point médian, the period, the parenthesis, the hyphen, the slash, the capital, and repetition. The most used form in our corpus is the point médian (N = 1,296) and the least used form is the capital (N = 2). Recall that the capital was one of the most used and most discursively salient forms in Abbou's study. Its almost complete absence in our study suggests that, if it was ever used in an official university context, it has since disappeared, along with differentialist feminism to which it was ideologically related. As with EI tout court, we find large amounts of variation across university and academic discipline. The distribution of different forms of EI across university and academic domain is shown in Figures 5 and 6.

FIGURE 5.

Écriture inclusive by university according to the écriture inclusive (EI) form

FIGURE 6.

Écriture inclusive by domain according to the écriture inclusive (EI) form

4.2.2. Analyses

Method of analysis. We ran a Bayesian multinomial regression model. Since the number of occurrences of slash (N = 5), capital (N = 2), and repetition (N = 266) forms are quite low compared to the hyphen (N = 424), parenthesis (N = 493), period (N = 705) and point médian (N = 1,296) forms, we decided to exclude them from the analysis. As for this type of analysis (four level dependent variable), the period will be the reference level.

Results. Figure 7 shows the proportions of EI forms depending on University Prestige (left) and Faculty Parity (right). Figure 8 shows the distribution of EI forms by academic domain in more/less prestigious universities (median split). In Figure 8, on the x‐axis, the academic domains range from male‐dominated disciplines (with a low proportion of women, for example Medicine) to female‐dominated disciplines (with a higher proportion of women, e.g. Literature and Language).

FIGURE 7.

Proportions of écriture inclusive (EI) forms by university prestige (left) and by faculty parity (right)

FIGURE 8.

Proportions of écriture inclusive (EI) forms by academic domain in more/less prestigious universities (median split)

As illustrated in the above figures and confirmed in the statistical analysis, we found different effects of prestige and parity depending on the type of EI.

When comparing point médian and period, the higher the prestige, the less the point médian is used compared to the period, and the higher the parity, the more it is used compared to the period. The interaction between prestige and parity shows that the higher the prestige, the higher the difference between male‐dominated and female‐dominated disciplines regarding the use of the point médian compared to the period (with more point médian used in female‐ than in male‐dominated disciplines), while this is less the case in less prestigious universities.

When comparing parenthesis and period this time, the higher the prestige, the more the parenthesis is used compared to period, and the higher the parity, the less it is used compared to period. The interaction between parity and prestige shows that the higher the prestige, the higher the difference between male‐dominated and female‐dominated disciplines as for the use of parenthesis compared to period (more parenthesis used in male‐dominated disciplines), contrary to less prestigious universities where the pattern between period and parenthesis is roughly similar between male‐ and female‐dominated disciplines.

Finally, as for the hyphen relative to the period, the analysis confirmed that the higher the prestige, the less the hyphen is used compared to period, and the higher the parity, the less the hyphen is used compared to the period.

4.2.3. Discussion

The first main descriptive result of our study of the different forms of EI is the high proportion of the point médian. Although we do find a wealth of forms, the point médian is overall the most frequent. It is not the variant with the broadest distribution, however, since it is not found in Medicine. The period, on the other hand, is found across all academic domains. Given this, we consider the period to have the least marked, most neutral social meaning, which is why we chose it as the intercept in the statistical analysis.

Compared to the period, the point médian, the parenthesis and the hyphen all show social conditioning. The less prestigious (and so more activist) a university is, the more they use the point médian compared to the period. At the beginning of the paper, we argued that the public debates about the point médian in 2017 established this variant as the primary target of criticism by the government and the right‐wing media. It is possible that these conflicts imbued the point médian with a social meaning related to left‐wing, antigovernment activism and that this social meaning appeals to professors in more activist universities. Results show that, as with use of EI itself, male‐dominated academic disciplines in prestigious universities avoid the point médian, compared to the period, and this effect is not as strong in less prestigious universities (see Figure 8).

The form that is comparatively favored by this group is the parenthesis, which is conditioned by prestige/activism and gender parity: The more prestigious (and less activist) a university is, the more faculty in it will use the parenthesis, compared to the period when they use EI. Likewise, the more male‐dominated a discipline is, the more they will use the parenthesis compared to period. Abbou's study showed that anarchists associate the parenthesis with the French state and right wing politics, and the results of our study suggest that this variant has maintained this social meaning.

Finally, the hyphen is conditioned by prestige and gender parity: The more prestigious a university, the less the hyphen will be used compared to the period, and the more female faculty members a department has, the less they will use the hyphen compared to the period. At first this seems strange, since the hyphen does not have any particular masculine associations, either in Abbou's study or in other discourses on la féminisation and écriture inclusive. However, it is important to keep in mind that the gender parity effect appears when we look within the occurrences of écriture inclusive. In other words, the hyphen is favored, compared to the period, by male‐dominated disciplines who actually use EI. Of the academic disciplines who are regular users of EI in our corpus, some of the most male‐dominated ones are sociology, anthropology, and political science, disciplines that favor the hyphen in our study (see OSF). Our corpus data alone cannot tell us why professors in these disciplines favor the hyphen; however, one possibility has to do with the history of the study of gender in these fields. In fact, much of the research on gender in the French university has been conducted by sociologists and political scientists, since French academia has been very resistant to the formation of gender studies departments and programs (Fassin, 2008; Parini, 2010). Gender has been a major focus of work in French sociology since the 1970s, and this has not been the case in other fields. For example, the study of language and gender is a much more recent development in language and linguistics departments in France (Greco, 2014). Recall that the hyphen was the favored form of Abbou's anarchists at the turn of the century, and its use in an activist university context does, indeed, appear to have arisen much earlier than activist use of the point médian. For example, the hyphen is also the favored form of early guidelines (1991–1992) for inclusive writing produced by the feminist division of the faculty union at the Université du Québec à Montréal (Syndicat des professeurs et professeures de l'Université du Québec à Montréal 21 ), and work in Québec may have influenced early adopters in France. In other words, we hypothesize that the hyphen is an older form, but, rather than being the older conservative form like the parenthesis, the hyphen is the older activist form. If sociologists, anthropologists, and political scientists had already been widely using écriture inclusive before the recent rise of the point médian, they would have less incentive to switch after 2017, since the radical social meaning of the hyphen persists. So again, we suggest that the patterns of use of EI are best understood as arising from the political dimensions of the academic culture in which the writers in our corpus work.

5. CONCLUSION

This paper presented a quantitative corpus study of écriture inclusive with the word étudiant ‘student’ in undergraduate brochures in 12 Parisian universities. We showed that, in 2019–2020, there exists an enormous amount of variation in both the presence/absence of EI and the forms that are employed. We argued, however, that this variation is not random: We showed that it is conditioned by gender parity in academic disciplines and by ideological concepts such as prestige and left‐wing activism. We suggested that the patterns that we found arise from a combination of the social meanings associated with ‘generic’ masculines and the different forms of écriture inclusive and the specific academic cultures in which the writers of the brochures are working and socializing. Our quantitative results suggest that the aspects of academic culture that are relevant for EI involve the prestige of one's university and the discipline one practices (more vs. less male‐dominated; sociology/anthropology/political science vs. others). We hypothesize that different academic cultures have different histories and different values, and this affects how they use EI to construct their institutional identity.

The results of our corpus study give us the first piece of the puzzle to understand why, contrary to many of its neighbors, governmental actions in France since 2017 have opposed EI. Although France is known to be linguistically conservative, opposition to language change is not sufficient to explain the virulence and the scope that debates on inclusive language have taken on. For example, in 1990, a government linguistic council proposed a spelling reform (la nouvelle orthographe). Although this language policy was not without its detractors (see Farid, 2012), the debates did not explode in the media and in the legal system in the way that debates on EI have done.

The results of our corpus study suggest that exclusive use of ‘generic’ masculines signals a politically conservative ideology, whereas some forms of EI, particularly the point médian, signal a more left‐wing political stance (when compared to another form like the period). As mentioned in Section 1, it is not only in France that masculines versus EI have come to code a right versus left distinction. However, what is unique to the French context is the precise shape of these ideologies and the fact that they are currently in conflict outside the linguistic domain. As we described at the beginning of the paper, both the Education Minister and one of the anti‐EI laws link using masculines to upholding (a certain version of) universal Republican values, one of the major talking points of the governing party. 22

As described in Section 2, the rise of EI with the point médian has been linked to the movement against selection at universities (Parcoursup), and our statistical results show that use of EI suggests a correlation with opposition to the LPPR, a recent law restructuring French higher education. Both of these governmental policies are viewed by those on the left as a way of introducing more competition into the French university and research systems. How globalized and competitive the education system should be and how/whether Republican Universalism should be applied are not debated in the same way in France's European and North American neighbors, even the francophone ones. For example, although French Canada has (roughly) the same linguistic system, 23 the kind of competitive higher education system that Parcoursup and LPPR move France towards has been in place in Canada for over 50 years. Likewise, although cultural universalism is regularly debated in Québec, when they deal with language, these debates focus on promoting French as the universal language compared to other languages (see Conseil Supérieur de la Langue Française, 2007), rather than refining the definition of ‘French’ itself. In this way, since the extralinguistic political conflicts that masculines and EI are associated with are specifically French, so too are the public debates surrounding this feminist linguistic practice.

The analysis that masculines and the point médian signal opposing political ideologies also sheds light on the special place that education has in these debates. Bourdieu and Passeron (1970)'s theory of the education system can give us a more detailed understanding of how a linguistic practice, like using a masculine or EI, can be related to a broader power struggle in French society. For Bourdieu and Passeron, university brochures such as the ones in our corpus are instances of pedagogical actions. Pedagogical actions are never ideologically neutral but rather rely on pedagogical authorities (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1970, p. 26). A successful pedagogical action requires that those on the receiving end of the action (i.e. the students) recognize the pedagogical authority underlying it and accept this authority as legitimate. In this way, incarnated as pedagogical authorities, ‘les rapports de force sont au principe, non seulement de l'AP [action pédagogique], mais aussi de la vérité objective de l'AP, méconnaissance qui définit la reconnaissance de la légitimité de l'AP et qui, à ce titre, en constitue la condition d'exercice’ 24 (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1970, p. 29). According to Bourdieu and Passeron, successful pedagogical actions are important because they produce pedagogical work, something that is a

travail d'inculcation qui doit durer assez pour produire une formation durable, i.e. un habitus comme produit de l'intériorization des principes d'un arbitraire culturel capable de se perpétuer après la cessation de l'AP et par là de perpétuer dans les pratiques les principes de l'arbitraire interiorisé.

kind of inculcation work which needs to last long enough to produce a lasting training, a habitus as the product of the internalization of principles given by a cultural arbitrary capable of perpetuating itself after the pedagogical action is over and by this, perpetuating the principles of the internalized arbitrary in practices. (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1970, p. 46)

In this way, Bourdieu and Passeron provide a model linking power relations to the internalized dispositions (the habitus) that the education system helps these powers produce (see also Bourdieu 1980). If we apply this model to gender inclusive writing, we can analyze brochures containing only masculines or containing EI forms as different kinds of pedagogical actions. The right‐wing and left‐wing political ideologies that masculines and the point médian are associated with can be analyzed as two different pedagogical authorities, which are sustained by the corresponding political power relations that we find active in French society. The particular interest that politicians of all orientations have taken in EI in the education system can now be understood as a concern for the consequences of the success of these different pedagogical actions. Since successful pedagogical actions create pedagogical work, and pedagogical work creates internalized dispositions towards political ideologies, it is understandable that both supporters and opponents of these ideologies would want to try to control one of the main mechanisms for their reproduction.

In conclusion, if our hypotheses are correct, then our paper has a number of implications for language policy and practices addressing gender inequality. At the time of writing, we are in the middle of an explosion of prohibitions on écriture inclusive but also an explosion of verbal hygiene related to this practice: The internet and bookstores abound with instructions about how and why to properly use EI, 25 courses to take to improve one's EI, 26 and even guides for how to get one's computer to produce the point médian. 27 We believe that our study shows that ‘mastery’ of écriture inclusive goes beyond knowing how to properly form an expression combining words like locuteur ‘speakerM’ and locutrice ‘speakerF’ with the interpunct and also involves grasping the social meanings associated with the different forms and understanding how they will contribute to the construction of one's own identity and the ‘image’ of one's institution.

We believe that the socio‐political associations of French's very many variants create a dilemma for policy writers: Through issuing statements promoting one form of EI versus another, they are implicitly signaling more than just their commitment to gender equality in their organization. Whether they like it or not, prescribing the use of the parenthesis over the period, the point médian over the hyphen, or even prohibiting the composite forms in favor of repetition, surreptitiously aligns the organization with socio‐political orientations, some of which are in active conflict currently in French society. This is understandably unpleasant for organizations who wish to present an equality friendly but politically ecumenical persona. Perhaps one way of resolving this dilemma would be through developing policies that make the political dimensions of EI fully explicit and give individuals the freedom to choose which form, from a set of forms, they prefer. Alternatively, organizations wishing to try to sidestep these thorny political issues could recommend forms of EI that our results suggest are not so strongly associated with anti‐government activism, such as the period or the parenthesis. Although the future of EI in France remains unclear, we hypothesize that only when people feel comfortable with both the gender equality and the other socio‐political aspects of their chosen form of EI will the acceptance of this feminist language practice become more widespread.

The results of our quantitative corpus study also open the door to a number of new studies of EI, using different methodologies: for example, qualitative research (interviews with members of the Parisian academic community), paired with social perception experiments studying the linguistic conditions under which readers' inferences about the political orientations of users of EI. It would also be worthwhile to extend both quantitative and qualitative research to textual genres other than university brochures.

In sum, we consider our study to be the first step in a broader investigation of the linguistic and political dimensions of écriture inclusive and the place of this linguistic practice in francophone activism and social life.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work has received funding from the program “Investissements d'Avenir” overseen by the French National Research Agency, ANR‐10‐LABX‐0083 (Labex EFL) and the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 850539). The authors thank Anne Abeillé, Julie Abbou, Olivier Bonami, Marie Candito, Michael Friesner, Yair Haendler, Amelia Kimball, Gabriel Thiberge, and audiences at the Université de Paris and the Ca' Foscari in Venice for helpful suggestions. However, all errors are our own.

Burnett H, Pozniak C. Political dimensions of gender inclusive writing in Parisian universities. J Sociolinguistics. 2021;25:808–831. 10.1111/josl.12489

ENDNOTES

France has a woman as a symbol: Marianne; one of its most beautiful words is fem‐inine: ‘Republic’ https://www.marianne.net/politique/pas‐besoin‐ecriture‐inclusive‐embleme‐de‐la‐france‐est‐une‐femme‐balaie‐ministre‐education

‘any legal public person, or private person benefiting from public funding’https://www.assemblee‐nationale.fr/dyn/15/textes/l15b3273_proposition‐loi

‘legal persons employed in public service’.

Note that political opposition to inclusive writing is also current very prominent in political debates in countries such as Brazil (see for example Paz et al., (2020)). Our sense is that the same kind of sociolinguistic dynamics are at play in Brazil and France; however, we leave a more detailed comparison to future work.

The parenthesis for me it's a bit associated with forms euh like France Télécom of the French state who sends you something and who says dear client M, dear client F and now instead [… ] they put dear client(e).

Frenchwomen, Frenchmen, help me!

Template of the experiment as well as the detailed results can be found on the OSF repository.

Because of the uneven number of occurrences among the universities, median split is not optimal, we only used it for the descriptive graphs.

See, for example, the proposed law against “separatism”, which came out around the same time as the EI ban. https://www.vie‐publique.fr/loi/277621‐loi‐separatisme‐respect‐des‐principes‐de‐la‐republique.

Note that Diaz and Heap (2020) find that the point médian is barely used on Canadian French Twitter, although it is the dominant form of EI on French Twitter. This finding supports our hypothesis that the rise and conflict surrounding the point médian is the result of specifically French concerns.

‘power relations are the source not only of the pedagogical action but also the objective truth of the pedagogical action, misrecognition that defines the recognition of the legitimacy of the pedagogical action and which, in this way, constitutes a precondition to its exercise.’

See, for example, https://www.egalite‐femmes‐hommes.gouv.fr/initiative/manuel‐decriture‐inclusive/, https://lessalopettes.wordpress.com/2017/09/27/petit‐guide‐pratique‐de‐lecriture‐inclusive/, among many many others.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the Open Science Framework (OSF, https://osf.io/wsdqx/).

REFERENCES

- Abbou, J. (2011). Double gender marking in french: A linguistic practice of antisexism. Current Issues in Language Planning, 12(1), 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Abbou, J. (2017). (typo) graphies anarchistes. où le genre révèle l'espace politique de la langue. Mots. Les Langages du Politique, 1, 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Abbou, J. , Arnold, A. , Candea, M. , & Marignier, N. (2018). Qui a peur de l'écriture inclusive? entre délire eschatologique et peur d'émasculation entretien. Semen. Revue De Sémio‐linguistique Des Textes Et Discours, (44). [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, L. (2004). AntConc: A learner and classroom friendly, multi‐platform corpus analysis toolkit. Proceedings of IWLeL, pp. 7–13.

- Arbour, M.‐È. , De Nayves, H. , & Royer, A. (2014). Féminisation linguistique: Étude comparative de l'implantation de variantes féminines marquées au canada et en Europe. Langage et Société, 2, 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Beauvoir, S. D. (1949). Le deuxième sexe. Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Becquer, A. , Cerquiglini, B. , Cholewka, N. , Coutier, M. , Frécher, J. , & Mathieu, M.‐J. (1999). Femme, j'écris ton nom. Guide d'aide la fminisation des noms de métiers, titres, grades et fonctions, Institut national de la langue française, Paris.

- Bem, S. L. , & Bem, D. J. (1973). Does sex‐biased job advertising “aid and abet” sex discrimination? 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 3(1), 6–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. (1980). Le sens pratique. Paris: Éditions de Minuit. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. , & Passeron, J.‐C. (1970). La reproduction. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit. [Google Scholar]

- Brauer, M. , & Landry, M. (2008). Un ministre peut‐il tomber enceinte? l'impact du générique masculin sur les représentations mentales. L'année Psychologique, 108(2), 243–272. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, H. , & Bonami, O. (2019). Linguistic prescription, ideological structure, and the actuation of linguistic changes: Grammatical gender in French parliamentary debates. Language in Society, 48(1), 65–93. [Google Scholar]

- Burr, E. (2003). Gender and language politics in France. Gender Across Languages, 3, 119–139. [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann, H. (2003). Engendering female visibility in German. In Hellinger M. & Bussman H. (Eds.), Gender across languages (vol. 3, pp. 141–174). Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, D. (1985). Feminism and linguistic theory. Macmillan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, D. (2012). Verbal hygiene. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cerquiglini, B. (2018). Le ministre est enceinte ou la grande querelle de la féminisation des noms. Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Champeil‐Desplats, V. (2019). La désignation des hommes et des femmes. In Flückiger A. (Ed.), La rédaction administrative et législative inclusive. (pp. 75–92). Editions Stämpfli. [Google Scholar]

- Chatard, A. , Guimond, S. , Lorenzi‐Cioldi, F. , & Désert, M. (2005). Domination masculine et identité de genre. Les Cahiers Internationaux de Psychologie Sociale, 3, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Conseil Supérieur de la Langue Française . (2007). Les accommodements raisonnables en matière linguistique. In Mémoire présenté à la commission de consultation sur les pratiques d'accommodement reliées aux différences culturelles. Palais des congrès, Montréal.

- Dawes, E. (2003). La féminisation des titres et fonctions dans la francophonie: De la morphologie à l'idéologie. Ethnologies, 25(2), 195–213. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, Y. , & Heap, D. (2020). Variation et changement dans les accords du français inclusif. Annual meeting of the Canadian Linguistics Association.

- Drummond, A. (2017). Ibex: Internet based experiments. URL Spellout. Net/ibexfarm.

- Farid, G. (2012). La “nouvelle orthographe”, 21 ans plus tard. SHS Web of Conferences, 1, 2055–2069. [Google Scholar]

- Fassin, E. (2008). L'empire du genre. L'histoire politique ambiguë d'un outil conceptuel. Number 187–188. Éditions de l'EHESS. [Google Scholar]

- Formanowicz, M. , Bedynska, S. , Cis lak, A. , Braun, F. , & Sczesny, S. (2013). Side effects of gender‐fair language: How feminine job titles influence the evaluation of female applicants. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43(1), 62–71. [Google Scholar]

- Formanowicz, M. M. , Cis lak, A. , Horvath, L. K. , & Sczesny, S. (2015). Capturing socially motivated linguistic change: How the use of gender‐fair language affects support for social initiatives in austria and poland. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster, E. D. , & Deardorff, A. (2017). Open science framework (osf). Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 105(2), 203. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, U. , Gygax, P. , Sarrasin, O. , Garnham, A. , & Oakhill, J. (2008). Au pairs are rarely male: Norms on the gender perception of role names across English, French, and German. Behavior Research Methods, 40(1), 206–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnham, A. , Gabriel, U. , Sarrasin, O. , Gygax, P. , & Oakhill, J. (2012). Gender representation in different languages and grammatical marking on pronouns: When beauticians, musicians, and mechanics remain men. Discourse Processes, 49(6), 481–500. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, L. (2014). Les recherches linguistiques sur le genre: Un état de l'art. Langage et Société, 2, 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Guentherodt, I. , Hellinger, M. , Pusch, L. F. , & Tromel‐Plotz, S. (1980). Richtlinien zur vermeidung sexistischen sprachgebrauchs. (principes pour éviter les usages sexistes dans la langue). Linguistische Berichte Braunschweig, 69, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gygax, P. , Gabriel, U. , Lévy, A. , Pool, E. , Grivel, M. , & Pedrazzini, E. (2012). The masculine form and its competing interpretations in French: When linking grammatically masculine role names to female referents is difficult. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 24(4), 395–408. [Google Scholar]

- Gygax, P. , Gabriel, U. , Sarrasin, O. , Oakhill, J. , & Garnham, A. (2008). Generically intended, but specifically interpreted: When beauticians, musicians, and mechanics are all men. Language and Cognitive Processes, 23(3), 464–485. [Google Scholar]

- Gygax, P. , Sarrasin, O. , Lévy, A. , Sato, S. , & Gabriel, U. (2013). La représentation mentale du genre pendant la lecture: État actuel de la recherche francophone en psycholinguistique. Journal of French Language Studies, 23(2), 243–257. [Google Scholar]

- Gygax, P. M. , Schoenhals, L. , Lévy, A. , Luethold, P. , & Gabriel, U. (2019). Exploring the onset of a male‐biased interpretation of masculine generics among French speaking kindergarten children. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellinger, M. , & Motschenbacher, H. (2002). Gender across languages, Vol. 2. John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Hornscheidt, A. (2003). Linguistic and public attitudes towards gender in Swedish. In Marlis H. & Heiko M. (Eds.), Gender across languages: The linguistic representation of women and men. (vol. 3, pp. 339–368). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Houdebine, A.‐M. (1987). Le français au féminin. La Linguistique, 23(Fasc 1):13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Houdebine, A.‐M. (1998). La féminisation des noms de métiers. Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, V. (1971). A study of the images produced through the use of the male pronoun as the generic. Moments in Contemporary Rhetoric and Communication, 1(2), 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, S.‐J. , Cimpian, A. , Meyer, M. , & Freeland, E. (2015). Expectations of brilliance underlie gender distributions across academic disciplines. Science, 347(6219), 262–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkel, E. , Maass, A. , & Frommelt, L. (2012). Shielding women against status loss: The masculine form and its alternatives in the Italian language. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 31(3), 311–320. [Google Scholar]

- Michard, C. (1996). Genre et sexe en linguistique: Les analyses du masculin générique. Mots. Les Langages du Politique, 49(1), 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- Mucchi‐Faina, A. (2005). Visible or influential? language reforms and gender (in) equality. Social Science Information, 44(1), 189–215. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, S. H. (2007). Language‐based discrimination: Blatant and subtle forms. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 26(2), 106–122. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario College of Teachers . (2005). Féminisation des documents en Français. Partie 1: Politique. OEEO. [Google Scholar]

- Parini, L. (2010). Le concept de genre: Constitution d'un champ d'analyse, controverses épistémologiques, linguistiques et politiques. Socio‐logos. Revue de l'Association Française de Sociologie, (5). [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels, A. (1998). Women changing language. Longman London. [Google Scholar]

- Paz, D. , Pelúcio, L. , & Borba, R. (2020). Le genre de la nation et le x de la question. Cahiers du Genre, 2, 177–203. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus, A. , & Pincus, R. (1980). Linguistic sexism and career education. Language Arts, 57(1), 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, J. W. , & Hacker, S. L. (1973). Sex role imagery and use of the generic “man” in introductory texts: A case in the sociology of sociology. The American Sociologist, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sczesny, S. , Formanowicz, M. , & Moser, F. (2016). Can gender‐fair language reduce gender stereotyping and discrimination? Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 25. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto, D. H. , & Cole, C. (1975). Prejudice against women: A new perspective. Sex Roles, 1(4), 385–393. [Google Scholar]

- Stahlberg, D. , Braun, F. , Irmen, L. , & Sczesny, S. (2007). Representation of the sexes in language. Social Communication, 163–187. [Google Scholar]

- Stahlberg, D. , Sczesny, S. , & Braun, F. (2001). Name your favorite musician: Effects of masculine generics and of their alternatives in german. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 20(4), 464–469. [Google Scholar]

- Stout, J. G. , & Dasgupta, N. (2011). When he doesn't mean you: Gender‐exclusive language as ostracism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(6), 757–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vachon‐L'Heureux, P. (1992). Quinze ans de féminisation au québec: De 1976 à 1991. Recherches Féministes, 5(1), 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- Vachon‐L'Heureux, P. , québécois de la langue française, O. , and Guénette, L. (2007). Avoir bon genre à l'écrit: Guide de rédaction épicène. Les publications du Québec. [Google Scholar]

- Vervecken, D. , & Hannover, B. (2015). Yes i can!. Social Psychology. 10.1027/1864-9335/a000229 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vervecken, D. , Hannover, B. , & Wolter, I. (2013). Changing (s) expectations: How gender fair job descriptions impact children's perceptions and interest regarding traditionally male occupations. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 82(3), 208–220. [Google Scholar]

- Viennot, É. (2014). Non, le masculin ne l'emporte pas sur le féminin. Petite histoire des résistances de la langue française.

- Weatherall, A. (2002). Gender, language and discourse. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yaguello, M. (1979). Les mots et les femmes: Essai d'approche socio‐linguistique de la condition féminine (vol. 75). Payot. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the Open Science Framework (OSF, https://osf.io/wsdqx/).