Abstract

目的

探讨极早产儿坏死性小肠结肠炎(necrotizing enterocolitis,NEC)发生的危险因素,并构建预测NEC发生风险的列线图模型。

方法

选取2015年1月至2021年12月住院的752例极早产儿为研究对象,包括2015~2020年极早产儿(建模集)654例和2021年极早产儿98例(验证集)。建模集根据有无发生NEC分为NEC组(n=77)和非NEC组(n=577),通过多因素logistic回归分析确定极早产儿NEC发生的独立危险因素,采用R软件绘制列线图模型。利用验证集的数据对列线图模型加以检验。采用受试者工作特征(receiver operator characteristic,ROC)曲线、Hosmer-Lemeshow拟合优度检验及校正曲线评估模型的效能,采用临床决策曲线评估模型的临床实用价值。

结果

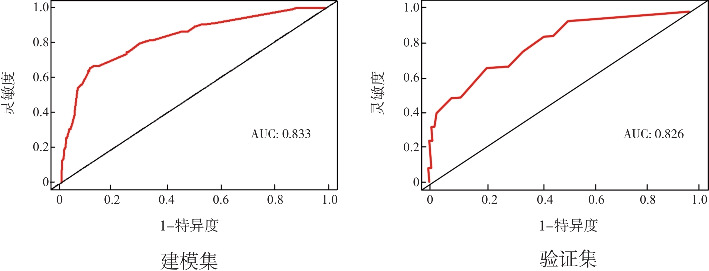

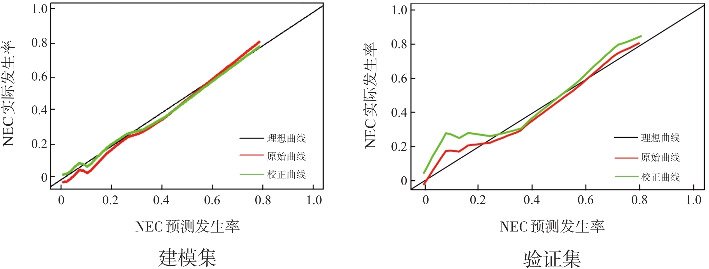

多因素logistic回归分析显示,新生儿窒息、败血症、休克、低白蛋白血症、严重贫血及配方奶喂养为极早产儿NEC发生的独立危险因素(P<0.05)。建模集ROC曲线的曲线下面积(area under the curve,AUC)为0.833(95%CI:0.715~0.952),验证集ROC曲线的AUC值为0.826(95%CI:0.797~0.862),表明该模型具有良好的区分度和判别能力。校正曲线和Hosmer-Lemeshow拟合优度检验显示该模型在预测值和真实值之间的准确性和一致性较好。

结论

新生儿窒息、败血症、休克、低白蛋白血症、严重贫血及配方奶喂养是极早产儿NEC发生的独立危险因素;基于多因素logistic回归分析结果建立的列线图模型可为临床早期评估极早产儿NEC的发生提供定量、简便、直观的工具。

Keywords: 坏死性小肠结肠炎, 危险因素, 列线图, 极早产儿

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the risk factors for necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) in very preterm infants and establish a nomogram model for predicting the risk of NEC.

Methods

A total of 752 very preterm infants who were hospitalized from January 2015 to December 2021 were enrolled as subjects, among whom 654 were born in 2015-2020 (development set) and 98 were born in 2021 (validation set). According to the presence or absence of NEC, the development set was divided into two groups: NEC (n=77) and non-NEC (n=577). A multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to investigate the independent risk factors for NEC in very preterm infants. R software was used to plot the nomogram model. The nomogram model was then validated by the data of the validation set. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, and the calibration curve were used to evaluate the performance of the nomogram model, and the clinical decision curve was used to assess the clinical practicability of the model.

Results

The multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that neonatal asphyxia, sepsis, shock, hypoalbuminemia, severe anemia, and formula feeding were independent risk factors for NEC in very preterm infants (P<0.05). The ROC curve of the development set had an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.833 (95%CI: 0.715-0.952), and the ROC curve of the validation set had an AUC of 0.826 (95%CI: 0.797-0.862), suggesting that the nomogram model had a good discriminatory ability. The calibration curve analysis and the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test showed good accuracy and consistency between the predicted value of the model and the actual value.

Conclusions

Neonatal asphyxia, sepsis, shock, hypoalbuminemia, severe anemia, and formula feeding are independent risk factors for NEC in very preterm infant. The nomogram model based on the multivariate logistic regression analysis provides a quantitative, simple, and intuitive tool for early assessment of the development of NEC in very preterm infants in clinical practice.

Keywords: Necrotizing enterocolitis, Risk factor, Nomogram, Very preterm infant

坏死性小肠结肠炎(necrotizing enterocolitis,NEC)是新生儿期最常见、最为致命的胃肠道急症。其发病机制尚未完全清楚,目前的研究认为NEC可能与肠道屏障功能不成熟、肠黏膜缺血缺氧、感染、喂养不恰当等多种因素的协同作用有关[1]。极早产儿是指出生胎龄<32周的早产儿[2]。研究显示,约85%的NEC发生于胎龄<32周或出生体重<1 500 g的早产儿,而中、晚期早产儿及足月儿仅占所有NEC患儿的15%[3]。国内近期一项多中心研究显示<32周早产儿NEC发生率为3.9%~10.7%,胎龄越小,发生率越高[4];极低出生体重儿NEC发生率为4.5%~8.7%,病死率为20%~30%[5]。国外高收入国家NEC的发生率为3.5%~6.8%[6]。国内一项对39个新生儿重症监护中心极早产儿或超低出生体重儿死亡原因调查显示,9.4%的极早产儿死于NEC[7]。综上所述,NEC在极早产儿中发生率高、病死率高,明确极早产儿发生NEC的危险因素,尽早识别可能发生NEC的高危极早产儿,及时采取预防或治疗措施,对提高极早产儿生存率和改善预后具有重要意义。虽然目前有关NEC发生的危险因素的文献较多,但纳入的病例数和变量数均偏少,且缺乏专门针对极早产儿NEC的研究;另外,所有的相关研究均未将危险因素转换为可视化预测模型,临床实用价值有限[8-9]。因此,本研究回顾性分析极早产儿的临床资料,探讨影响极早产儿NEC的危险因素,并在此基础上建立列线图预测模型,以期为极早产儿NEC的筛查和防治提供参考。

1. 资料与方法

1.1. 研究对象

选取2015年1月至2021年12月于包钢集团第三职工医院新生儿科住院的胎龄<32周的新生儿(极早产儿)为研究对象,将2015~2020年的极早产儿设定为建模集,2021年的极早产儿为验证集。根据是否发生NEC分为NEC组和非NEC组。NEC的诊断参照修正Bell分期[10]。排除标准:(1)疑似NEC患儿:即BellⅠ期;(2)合并先天性疾病(如胃肠道畸形、严重先天性心脏病、染色体异常、遗传代谢病等)。

1.2. 资料收集

回顾性收集研究对象的临床资料,包括:(1)出生情况:胎龄、出生体重、性别、出生方式、有无窒息、是否为小于胎龄儿(small for gestational age,SGA)、是否多胎等;(2)孕母围生期情况:母亲年龄、是否合并妊娠期高血压疾病、妊娠糖尿病、胎膜早破>18 h等;(3)NEC发病前患病情况及治疗情况:新生儿呼吸窘迫综合征(respiratory distress syndrome,RDS)、动脉导管未闭(patent ductus arteriosus,PDA)、败血症、休克、低白蛋白血症、呼吸暂停、严重贫血、应用肺表面活性物质(pulmonary surfactant,PS)、静脉注射免疫球蛋白(intravenous immunogloblin,IVIG)等;(4)NEC发病前喂养情况:开奶时间、是否配方奶喂养、益生菌使用等。NEC组收集NEC发病前患病、治疗及喂养情况,非NEC组对应的临床资料收集至NEC组患儿的NEC平均发病日龄之前。

1.3. 相关名词定义说明

低白蛋白血症定义为血清白蛋白≤25 g/L[11]。严重贫血定义为早产儿血红蛋白≤80 g/L[12-13]。妊娠期高血压疾病、妊娠糖尿病、胎膜早破等围生期疾病诊断标准依据《实用妇产科学》第4版[14]。新生儿窒息、RDS、败血症、PDA、呼吸暂停等新生儿疾病的诊断标准依据《实用新生儿学》第5版[2]。

1.4. 统计学分析

采用SPSS 26.0软件进行统计学分析,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。对于计数资料采用例数及百分率(%)进行描述,组间比较采用 检验;对于计量资料,服从正态分布者采用均数±标准差( )进行描述,组间比较采用成组t检验;不服从正态分布者采用中位数(四分位数间距)[M(P 25,P 75)]进行描述,组间比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验。采用二元logistic回归分析筛选NEC发生的影响因素,利用R软件(R4.0.4)将筛选出的变量绘制列线图预测模型,使用500次Bootstrap法做内部验证,绘制模型的受试者工作特征(receiver operator characteristic,ROC)曲线,并计算曲线下面积(area under the curve,AUC),外部验证通过验证集完成。采用Hosmer-Lemeshow拟合优度检验评价模型的准确性,校正曲线评估模型的校准度。采用决策曲线分析(decision curve analysis,DCA)评价模型的临床实用性。

2. 结果

2.1. 建模集和验证集临床资料的比较

建模集共纳入654例极早产儿,验证集共纳入98例极早产儿。建模集与验证集各变量的比较差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05),见表1。

表1.

建模集和验证集临床资料的比较

| 变量 | 建模集 (n=654) | 验证集 (n=98) | /t值 | P值 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 围生期情况 | ||||

| 母亲年龄 ( , 岁) | 25.7±2.4 | 24.6±2.2 | 1.166 | 0.628 |

| 妊娠期高血压疾病 [n (%)] | 174(26.6) | 25(25.5) | 0.053 | 0.819 |

| 妊娠糖尿病 [n(%)] | 97(14.8) | 14(14.3) | 0.020 | 0.887 |

| 出生情况 | ||||

| 胎龄 ( , 周) | 29.8±1.8 | 29.6±1.5 | 1.984 | 0.159 |

| 男性 [n(%)] | 328(50.2) | 49(50.0) | 0.001 | 0.977 |

| 剖宫产 [n(%)] | 364(55.7) | 54(55.1) | 0.011 | 0.918 |

| 出生体重 ( , g) | 1 447±358 | 1 538±353 | -2.342 | 0.816 |

| SGA [n(%)] | 72(11.0) | 10(10.2) | 0.057 | 0.812 |

| 新生儿窒息 [n(%)] | 95(14.5) | 14(14.3) | 0.040 | 0.950 |

| 多胎 [n(%)] | 121(18.5) | 14(14.3) | 1.028 | 0.311 |

| 胎膜早破>18 h [n(%)] | 193(29.5) | 28(28.6) | 0.036 | 0.849 |

| 患病情况 [n (%)] | ||||

| RDS | 246(37.6) | 36(36.7) | 0.028 | 0.867 |

| 败血症 | 62(9.5) | 8(8.2) | 0.175 | 0.676 |

| 休克 | 61(9.4) | 9(9.2) | 0.002 | 0.967 |

| PDA | 191(29.2) | 28(28.6) | 0.017 | 0.898 |

| 低白蛋白血症 | 98(15.0) | 14(12.5) | 0.473 | 0.492 |

| 严重贫血 | 46(7.0) | 6(6.1) | 0.110 | 0.740 |

| 呼吸暂停 | 107(16.4) | 16(16.3) | 0.000 | 0.993 |

| 治疗情况 [n(%)] | ||||

| 应用PS | 166(25.4) | 24(24.5) | 0.036 | 0.850 |

| 出生前3 d使用抗生素 | 391(59.8) | 52(53.1) | 1.592 | 0.207 |

| 应用布洛芬 | 111(17.0) | 16(16.3) | 0.025 | 0.874 |

| 脐静脉置管 | 144(22.0) | 22(22.4) | 0.009 | 0.924 |

| 应用IVIG | 49(7.5) | 7(7.1) | 0.015 | 0.902 |

| 应用咖啡因 | 67(10.2) | 11(11.2) | 0.088 | 0.767 |

| 喂养情况 [n (%)] | ||||

| 生后30 min开奶 | 179(27.4) | 28(28.6) | 0.062 | 0.804 |

| 配方奶喂养 | 494(75.5) | 75(76.5) | 0.046 | 0.830 |

| 应用益生菌 | 72(11.0) | 10(10.2) | 0.057 | 0.812 |

注:[SGA]小于胎龄儿;[RDS]呼吸窘迫综合征;[PDA]动脉导管未闭;[PS]肺表面活性物质;[IVIG]静脉注射免疫球蛋白。

2.2. 建模集NEC组和非NEC组临床资料的比较

建模集中,NEC组77例,非NEC组577例。NEC组新生儿窒息、败血症、休克、低白蛋白血症、严重贫血及配方奶喂养的比例明显高于非NEC组(P<0.05),而在生后30 min开奶的比例明显低于非NEC组(P<0.05),见表2。

表2.

建模集NEC组与非NEC组临床资料的比较

| 变量 | 非NEC组 (n=577) | NEC组 (n=77) | /t值 | P值 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 围生期情况 | ||||

| 母亲年龄 ( , 岁) | 25.6±2.3 | 26.1±2.8 | -1.712 | 0.146 |

| 妊娠期高血压疾病 [n(%)] | 159(27.6) | 15(19.5) | 2.269 | 0.132 |

| 妊娠糖尿病 [n(%)] | 88(15.3) | 9(11.7) | 0.683 | 0.409 |

| 出生情况 | ||||

| 胎龄 ( , 周) | 29.8±1.8 | 30.1±1.8 | -1.605 | 0.880 |

| 男性 [n(%)] | 295(51.1) | 33(42.9) | 1.858 | 0.173 |

| 剖宫产 [n(%)] | 321(55.6) | 43(55.8) | 0.001 | 0.972 |

| 出生体重 ( , g) | 1 446±348 | 1 458±427 | -0.288 | 0.067 |

| SGA [n(%)] | 62(10.7) | 10(13.0) | 0.348 | 0.555 |

| 新生儿窒息 [n(%)] | 67(11.6) | 28(36.4) | 33.522 | <0.001 |

| 多胎 [n(%)] | 109(18.9) | 12(15.6) | 0.493 | 0.483 |

| 胎膜早破>18 h [n(%)] | 169(29.3) | 24(31.2) | 0.115 | 0.734 |

| 患病情况 [n(%)] | ||||

| RDS | 214(37.1) | 32(41.6) | 0.578 | 0.447 |

| 败血症 | 51(8.8) | 21(27.3) | 23.563 | <0.001 |

| 休克 | 42(7.3) | 19(24.7) | 24.309 | <0.001 |

| PDA | 171(29.6) | 20(26.0) | 0.441 | 0.507 |

| 低白蛋白血症 | 74(12.8) | 24(31.2) | 17.944 | <0.001 |

| 严重贫血 | 32(5.5) | 14(18.2) | 16.588 | <0.001 |

| 呼吸暂停 | 94(16.3) | 13(16.9) | 0.017 | 0.895 |

| 治疗情况 [n(%)] | ||||

| 应用PS | 150(26.0) | 16(20.8) | 0.976 | 0.323 |

| 出生前3 d使用抗生素 | 342(59.3) | 49(63.6) | 0.538 | 0.463 |

| 应用布洛芬 | 97(16.8) | 14(18.2) | 0.091 | 0.763 |

| 脐静脉置管 | 130(22.5) | 14(18.2) | 0.748 | 0.387 |

| 应用IVIG | 42(7.3) | 7(9.1) | 0.322 | 0.571 |

| 应用咖啡因 | 59(10.2) | 8(10.4) | 0.002 | 0.964 |

| 喂养情况 [n(%)] | ||||

| 生后30 min开奶 | 166(28.8) | 13(16.9) | 4.828 | 0.028 |

| 配方奶喂养 | 425(73.7) | 69(89.6) | 9.356 | 0.002 |

| 应用益生菌 | 65(11.3) | 7(9.1) | 0.328 | 0.567 |

注:[SGA]小于胎龄儿;[RDS]呼吸窘迫综合征;[PDA]动脉导管未闭;[PS]肺表面活性物质;[IVIG]静脉注射免疫球蛋白;[NEC]坏死性小肠结肠炎。

2.3. 极早产儿NEC发生的多因素logistic回归分析

以极早产儿是否发生NEC为因变量,以NEC组和非NEC组单因素分析中有统计学意义的7个因素(新生儿窒息、败血症、休克、低白蛋白血症、严重贫血、配方奶喂养、生后30 min开奶)为自变量进行多因素logistic回归分析。结果显示:新生儿窒息、败血症、休克、低白蛋白血症、严重贫血及配方奶喂养是极早产儿NEC发生的独立危险因素(P<0.05),见表3。

表3.

极早产儿NEC发生的多因素logistic回归分析

| 变量 | B | SE | Wald | P | OR | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 新生儿窒息 | 1.262 | 0.304 | 17.272 | <0.001 | 3.533 | 1.948~6.407 |

| 败血症 | 1.053 | 0.273 | 14.837 | <0.001 | 2.866 | 1.677~4.897 |

| 休克 | 1.464 | 0.355 | 17.016 | <0.001 | 4.321 | 2.156~8.662 |

| 低白蛋白血症 | 0.999 | 0.276 | 13.093 | <0.001 | 2.652 | 1.635~4.302 |

| 严重贫血 | 1.046 | 0.275 | 14.452 | <0.001 | 2.847 | 1.660~4.882 |

| 生后30 min开奶 | 0.035 | 0.498 | 0.005 | 0.945 | 1.035 | 0.390~2.476 |

| 配方奶喂养* | 1.170 | 0.574 | 4.161 | 0.041 | 3.223 | 1.047~9.925 |

| 常数项 | -4.648 | 0.639 | 52.892 | <0.001 | 0.010 |

注:[NEC]坏死性小肠结肠炎。*以纯母乳喂养为参照。

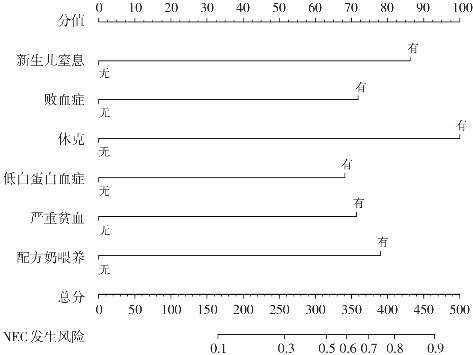

2.4. 列线图预测模型的建立

采用R软件,基于多因素logistic回归分析的结果,将新生儿窒息、败血症、休克、低白蛋白血症、严重贫血及配方奶喂养6个变量纳入列线图,建立极早产儿NEC发生风险的预测模型,见图1。R软件根据上述logistic回归分析结果中各变量OR值进行分值分配(新生儿窒息87分、败血症72分、休克100分、低白蛋白血症70分、严重贫血71分、配方奶喂养80分,无则为0分),根据极早产儿的具体情况将存在的变量的相应分数相加得出该患儿的总分,再绘制总分到风险轴的垂直线获得患儿发生NEC的概率,总分越高说明该极早产儿发生NEC的可能性就越大,从而能够根据得分对极早产儿NEC的发生风险进行早期定量预测。例如:某极早产儿患新生儿窒息(得87分),生后配方奶喂养(得80分),住院期间出现败血症(得72分)和低白蛋白血症(得70分),未发生休克(得0分),未出现严重贫血(得0分),则该患儿总分约为310分,对应到NEC风险轴可以得出该患儿发生NEC的风险约为50%。

图1. 极早产儿NEC发生风险的列线图模型 每个变量“有/无”分别对应“得分/0分”,将各变量的得分相加得到总分,再对应到风险轴即可得出NEC的发生风险。.

2.5. 列线图模型的评价与验证

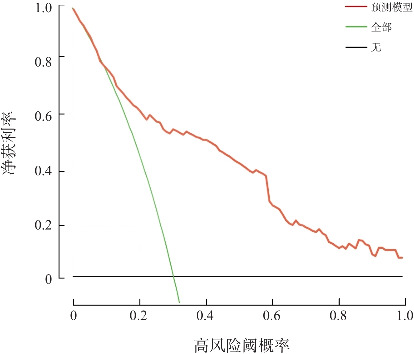

绘制模型的ROC曲线,并计算AUC,结果显示:建模集AUC为0.833(95%CI:0.715~0.952),验证集AUC为0.826(95%CI:0.797~0.862),说明模型具有较好的预测能力,见图2。Hosmer-Lemeshow拟合优度检验结果: =1.8339,自由度8,P=0.9857。同时绘制模型的校正曲线,建模集和验证集的校正曲线均与理想曲线拟合良好,见图3。Hosmer-Lemeshow拟合优度检验和校正曲线均提示模型在实际发生率和预测发生率之间具有较好的一致性。以高风险阈概率为横坐标,净获利率为纵坐标,绘制列线图模型的DCA曲线,见图4。利用该列线图模型评估出NEC发生风险较高的极早产儿后,继而采取干预措施可能会使极早产儿获得更高的临床效益。

图2. 列线图模型的ROC曲线.

图3. 列线图模型的校正曲线.

图4. 列线图模型的DCA曲线 黑线代表所有极早产儿均未发生NEC,净获利为0;绿线代表所有极早产儿均发生NEC,净获利率为该反斜线的斜率;红线代表本模型的DCA曲线,高风险阈概率在绿线和红线之间(0.33~1.0)时本模型预测NEC发生是可行的,患儿净获利率高。.

3. 讨论

尽管早产儿救治水平有了明显提高,但极早产儿NEC的发病率和病死率仍然居高不下[4-7]。国内多中心研究显示<32周早产儿NEC的发生率波动于3.9%~10.7%[4]。本研究中NEC发生率为7.6%(84/1 097),与多中心研究结果相一致。本研究通过回顾性收集2015~2020年极早产儿的临床资料,采用单因素分析和多因素分析相结合的方法,明确了新生儿窒息、败血症、休克、低白蛋白血症、严重贫血及配方奶喂养是极早产儿NEC的独立危险因素,基于多因素logistic回归分析结果建立列线图预测模型,并用2021年极早产儿数据验证模型的准确性。列线图模型的优点是可以将复杂、冗长的回归方程转换为简便、易行、可视、可读的图线,使预测结果更直观、连续,临床实用性更强。本研究建模集和验证集ROC曲线的AUC分别为0.833(95%CI:0.715~0.952)和0.826(95%CI:0.797~0.862),表明模型具有良好的区分度和预测精准度。绘制的校正曲线和Hosmer-Lemeshow拟合优度检验均说明模型在预测值与真实值之间准确性和一致性较好。同时DCA曲线表明模型具有良好的临床实用价值。

本研究中建模集和验证集中新生儿窒息发生率分别为14.5%(95/654)和14.3%(14/98),说明极早产儿窒息的发生率高,需要引起足够的重视。根据世界卫生组织的估计,全球每年超过20%的新生儿死于窒息,在早产儿中这一比例甚至达到60%,其中6%的窒息可导致NEC[15]。窒息的本质是缺氧[16],窒息早期患儿体内血流重新分布,非重要脏器如胃肠道血供减少,黏膜屏障功能障碍,故易导致细菌移位和NEC。败血症是由病原菌导致的急性全身性感染,它继发于宿主对感染的反应失调,会对肠道产生强烈的影响。多项研究已证实新生儿败血症是NEC的独立危险因素,败血症婴儿的NEC发生率约为非败血症婴儿的3倍[17-18]。本研究也显示败血症是极早产儿NEC的危险因素(OR=2.866,P<0.001)。本研究多因素logistic回归分析显示,休克对NEC发病的影响作用最大(OR=4.321,P<0.001)。休克患儿组织长期灌注不足导致线粒体功能障碍、能量合成受损,最终引起细胞死亡和器官衰竭[19],同时休克伴有炎症介质的释放和氧自由基的产生,从而增加发生NEC的风险,这一结论与Samuels等[20]的报道一致。2016年JAMA发表的一项多中心、大样本、前瞻性队列研究[21]显示,输注红细胞与NEC发生没有关联(HR=0.44,95%CI:0.17~1.12,P=0.09),但严重贫血(血红蛋白≤80 g/L)是NEC的独立危险因素(HR=5.99,95%CI:2.00~18.0,P=0.001),且血红蛋白每下降10 g/L,NEC发生率增加65%。本研究参考JAMA的数据,将严重贫血(血红蛋白≤80 g/L)作为极早产儿NEC危险因素筛选的变量,结果也显示NEC组严重贫血发生率明显高于非NEC组(18.2% vs 5.5%),且严重贫血是极早产儿NEC发生的独立危险因素(OR=2.847,P<0.001)。白蛋白在维持血浆胶体渗透压中发挥着关键作用[22],白蛋白降低引起血浆胶体渗透压下降,导致大量液体潴留在组织间隙中,机体有效循环血容量不足,继而出现多脏器灌注减少和微循环功能障碍;白蛋白还有利于肠上皮细胞的自我更新和分化[22],白蛋白缺乏可以引起肠道菌群失调、上皮细胞断裂、免疫功能受损,从而促进病原体入侵,这些机制均与NEC的发病有关[22]。喂养方式与NEC的发生风险显著相关。母乳中含有丰富的溶菌酶、乳铁蛋白、免疫因子及生长发育因子等活性成分,具有抗感染、抗氧化及免疫调节的作用[23]。《新生儿坏死性小肠结肠炎临床诊疗指南(2020)》[5]也推荐预防NEC首选亲母母乳喂养,当母乳不足或缺乏时,推荐使用捐赠人乳。配方奶最大的特点在于缺乏这些活性物质,故配方奶喂养儿较母乳喂养儿更易发生肠道感染。国内一项包含639例早产儿的回顾性研究[24]也证实与母乳喂养相比,配方奶明显增加NEC的发生率,同时延长早产儿的住院时间。本研究显示配方奶喂养儿发生NEC的风险较纯母乳喂养儿增加(OR=3.223,P<0.05)。

综上所述,本研究发现新生儿窒息、败血症、休克、低白蛋白血症、严重贫血及配方奶喂养是极早产儿NEC发生的独立危险因素,基于多因素logistic回归分析结果建立了列线图预测模型,该模型的区分度和校准度较好,临床实用价值较高,为临床早期评估极早产儿发生NEC的风险提供了一个定量、简便、直观的工具。本研究的局限性包括:(1)本研究为单中心、回顾性病例对照研究,不可避免会出现一定程度的选择偏倚;(2)由于本研究样本来源时间跨度较长,早年的诊疗水平和对疾病认识有限,部分潜在的可能影响极早产儿NEC发生的危险因素数据未能完整保存,比如母亲及患儿维生素D水平、延迟脐带结扎时间、病原菌种类、妊娠期胆汁淤积等。因此未来还需要高质量、前瞻性、多中心研究进一步检验本模型的效能。

基金资助

包头市卫生健康科技计划项目(wsjkkj079)。

参 考 文 献

- 1. Eaton S, Rees CM, Hall NJ. Current research on the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and management of necrotizing enterocolitis[J]. Neonatology, 2017, 111(4): 423-430. DOI: 10.1159/000458462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. 邵肖梅, 叶鸿瑁, 丘小汕. 实用新生儿学[M]. 5版. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sharma R, Hudak ML. A clinical perspective of necrotizing enterocolitis: past, present, and future[J]. Clin Perinatol, 2013, 40(1): 27-51. DOI: 10.1016/j.clp.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jiang S, Yan W, Li S, et al. Mortality and morbidity in infants <34 weeks' gestation in 25 NICUs in China: a prospective cohort study[J]. Front Pediatr, 2020, 8: 33. DOI: 10.3389/fped.2020.00033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. 黄兰, 熊涛, 唐军, 等. 新生儿坏死性小肠结肠炎临床诊疗指南(2020)[J]. 中国当代儿科杂志, 2021, 23(1): 1-11. DOI: 10.7499/j.issn.1008-8830.2011145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Battersby C, Santhalingam T, Costeloe K, et al. Incidence of neonatal necrotising enterocolitis in high-income countries: a systematic review[J]. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 2018, 103(2): F182-F189. DOI: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhou J, Ba Y, Du Y, et al. The etiology of neonatal intensive care unit death in extremely low birth weight infants: a multicenter survey in China[J]. Am J Perinatol, 2021, 38(10): 1048-1105. DOI: 10.1055/s-0040-1701611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. 王静, 唐莲芳, 顾美群, 等. 新生儿坏死性小肠结肠炎的危险因素及早期临床特点[J]. 昆明医科大学学报, 2021, 42(11): 99-104. DOI: 10.12259/j.issn.2095-610X.S20211118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. 邹耀明, 阮旭, 邓秀妹, 等. 新生儿坏死性小肠结肠炎发生的危险因素分析[J]. 现代医学与健康研究(电子版), 2021, 5(13): 110-112. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Feigin RD, et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging[J]. Ann Surg, 1978, 187(1): 1-7. DOI: 10.1097/00000658-197801000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gatta A, Verardo A, Bolognesi M. Hypoalbuminemia[J]. Intern Emerg Med, 2012, 7(Suppl 3): S193-S199. DOI: 10.1007/s11739-012-0802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kirpalani H, Whyte RK, Andersen C, et al. The premature infants in need of transfusion (PINT) study: a randomized, controlled trial of a restrictive (low) versus liberal (high) transfusion threshold for extremely low birth weight infants[J]. J Pediatr, 2006, 149(3): 301-307. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bell EF, Strauss RG, Widness JA, et al. Randomized trial of liberal versus restrictive guidelines for red blood cell transfusion in preterm infants[J]. Pediatrics, 2005, 115(6): 1685-1691. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2004-1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. 徐丛剑, 华克勤. 实用妇产科学[M]. 4版. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schnabl KL, Van Aerde JE, Thomson AB, et al. Necrotizing enterocolitis: a multifactorial disease with no cure[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2008, 14(14): 2142-2161. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.14.2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reddy NR, Krishnamurthy S, Chourasia TK, et al. Glutamate antagonism fails to reverse mitochondrial dysfunction in late phase of experimental neonatal asphyxia in rats[J]. Neurochem Int, 2011, 58(5): 582-590. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cotten CM. Modifiable risk factors in necrotizing enterocolitis[J]. Clin Perinatol, 2019, 46(1): 129-143. DOI: 10.1016/j.clp.2018.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rose AT, Patel RM. A critical analysis of risk factors for necrotizing enterocolitis[J]. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med, 2018, 23(6): 374-379. DOI: 10.1016/j.siny.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Unsal D, Kacan M, Temiz-Resitoglu M, et al. The role of Syk/IĸB-α/NF-ĸB pathway activation in the reversal effect of BAY 61-3606, a selective Syk inhibitor, on hypotension and inflammation in a rat model of zymosan-induced non-septic shock[J]. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol, 2018, 45(2): 155-165. DOI: 10.1111/1440-1681.12864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Samuels N, van de Graaf RA, de Jonge RCJ, et al. Risk factors for necrotizing enterocolitis in neonates: a systematic review of prognostic studies[J]. BMC Pediatr, 2017, 17(1): 105. DOI: 10.1186/s12887-017-0847-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Patel RM, Knezevic A, Shenvi N, et al. Association of red blood cell transfusion, anemia, and necrotizing enterocolitis in very low-birth-weight infants[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(9): 889-897. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2016.1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vlasova AN, Paim FC, Kandasamy S, et al. Protein malnutrition modifies innate immunity and gene expression by intestinal epithelial cells and human rotavirus infection in neonatal gnotobiotic pigs[J]. mSphere, 2017, 2(2): e00046-17. DOI: 10.1128/mSphere.00046-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meinzen-Derr J, Poindexter B, Wrage L, et al. Role of human milk in extremely low birth weight infants' risk of necrotizing enterocolitis or death[J]. J Perinatol, 2009, 29(1): 57-62. DOI: 10.1038/jp.2008.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. 李永伟, 严超英, 杨磊, 等. 母乳及配方奶喂养对NICU早产儿的影响[J]. 中国当代儿科杂志, 2017, 19(5): 572-575. DOI: 10.7499/j.issn.1008-8830.2017.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]