Abstract

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) with rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes has found widespread application for analyzing the composition of microbial communities in complex environmental samples. Although bacteria can quickly be detected by FISH, a reliable method to determine absolute numbers of FISH-stained cells in aggregates or biofilms has, to our knowledge, never been published. In this study we developed a semiautomated protocol to measure the concentration of bacteria (in cells per volume) in environmental samples by a combination of FISH, confocal laser scanning microscopy, and digital image analysis. The quantification is based on an internal standard, which is introduced by spiking the samples with known amounts of Escherichia coli cells. This method was initially tested with artificial mixtures of bacterial cultures and subsequently used to determine the concentration of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in a municipal nitrifying activated sludge. The total number of ammonia oxidizers was found to be 9.8 × 107 ± 1.9 × 107 cells ml−1. Based on this value, the average in situ activity was calculated to be 2.3 fmol of ammonia converted to nitrite per ammonia oxidizer cell per h. This activity is within the previously determined range of activities measured with ammonia oxidizer pure cultures, demonstrating the utility of this quantification method for enumerating bacteria in samples in which cells are not homogeneously distributed.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) using rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes is frequently applied to quantify the composition of microbial communities in different environments (1, 17, 21, 23, 33, 35). In such studies cell numbers are generally obtained by manual counting in an epifluorescence microscope. Usually the relative abundance of a probe target population is determined by comparison of the obtained numbers (i) with counts of all bacterial cells detectable by FISH via simultaneous hybridization with a bacterial probe (10, 11, 30, 34) or probe set (9), or (ii) with counts of all organisms containing DNA by simultaneous application of nucleic acid staining dyes (16, 29, 35, 38).

Although quantitative FISH has provided novel insights into the structure and dynamics of microbial communities, it suffers from tediousness and limited accuracy for samples containing densely aggregated cells like activated sludge flocs or biofilms. The latter problem can in part be ameliorated by the use of confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) for the detection of probe-labeled cells (36). However, even if optical CLSM sections are recorded, it is not feasible to manually count a sufficient number of cells in each hybridization experiment in a reasonable time period to obtain statistically reliable results. This limitation has two reasons. First, manual counting itself is very time-consuming, and thus generally not more than a few thousand cells per hybridization experiment were counted in previous studies. Second, manual counting requires high-magnification CLSM sections, which allow single-cell resolution within clusters. However, such images contain relatively few cells, and therefore many images need to be recorded, rendering the procedure even more time-consuming. Therefore, more precise methods are required to quantify the composition of the microflora in samples containing clustered cells.

In principle, flow cytometry is a more efficient and accurate alternative for quantification of fluorescently labeled bacterial cells (39). However, for the analysis of microbial flocs and biofilms, flow cytometry is of limited use because it necessitates efficient dispersion of clustered bacteria prior to the measurement, a requirement which frequently cannot be fulfilled (38, 39).

To overcome the limitations of manual cell-counting procedures, semiautomated digital image analysis tools were recently developed which quantify fluorescently labeled bacteria in environmental samples (6, 29). But such solutions are not able to efficiently count cells in dense clusters or biofilms because single-cell recognition within these structures cannot be automated. This problem can be circumvented by measuring the areas of specifically stained bacteria in randomly acquired optical CLSM sections. This approach only requires the software to differentiate between labeled biomass (including cell clusters) and unlabeled background but does not rely on single-cell recognition within clusters. The abundance of a particular population is then expressed as fraction of the area occupied by all bacteria (8, 32).

For this purpose, an environmental sample is hybridized simultaneously with different rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes: one specific probe that targets the population which is to be quantified, and one domain-specific probe set that detects most bacteria. The population-specific and the domain-specific probes are labeled with different fluorochromes. Following FISH, the fluorescence conferred by the different probes is recorded in separate CLSM images. The areas of the labeled cells in these images are measured by digital image analysis. Since this approach analyses low-magnification images and can be partly automated, it allows rapid quantification of large numbers of bacteria, thereby significantly improving the statistical accuracy of the measurement (8, 32).

Ecological studies of complex microbial communities may attempt to determine not only relative abundances of probe-defined bacterial populations, but also the respective cell concentrations in a sample. This is particularly important if different samples which differ in their prokaryotic biomass content are to be compared. Furthermore, cell concentrations per volume or weight unit of an environmental sample are needed to calculate key functional attributes of bacterial populations, like in situ growth rates and in situ substrate turnover rates per cell. Despite their importance, cell concentrations of FISH-stained bacterial populations have rarely been determined for biofilms or activated sludge flocs by manual counting because these measurements required additional time-consuming and bias-introducing homogenization and membrane filtration steps (17, 24, 26, 37). In addition, it is impossible to directly apply the above-mentioned area-based quantification methods (8, 32) to semiautomatically determine absolute cell numbers in a sample after membrane filtration because these methods cannot accurately measure the entire biovolume of all cells of a probe-labeled population in the filtered biomass on top of defined filter areas.

Recently, CLSM-based methods to semiautomatically measure the biovolume of fluorescently labeled bacteria (15, 19) were published. These methods could theoretically be applied to determine absolute cell numbers of probe-defined bacterial populations on membrane filters. However, biovolume-based quantification is only accurate if serial optical sections are recorded using small vertical step intervals and subsequently combined to image stacks. This procedure is extremely time-consuming and leads to significant bleaching of FISH-labeled bacterial cells.

In this study we thus developed a semiautomated procedure for determining cell concentrations of bacterial populations in complex samples by FISH and CLSM using the area-based quantification method (8, 32). Spiking of the samples with known amounts of Escherichia coli cells, which were used as internal standards for the subsequent FISH analysis, allowed us to infer the absolute cell numbers of probe-target bacteria from their measured areas by digital analysis of CLSM images.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Test strains, culture conditions, cell fixation, and activated sludge sampling.

Type strains of Comamonas testosteroni (DSM 1622) and Gluconobacter asaii (DSM 7148) were obtained from the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH (DSMZ) (Braunschweig, Germany). Cells of C. testosteroni and G. asaii were grown overnight under agitation at 30°C in medium DSM M1 (0.5% [wt/vol] peptone, 0.3% [wt/vol] meat extract, pH 7.0) and DSM M626 (5% [wt/vol] d-sorbitol, 1% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 1% [wt/vol] peptone, pH 6.0), respectively. Pure cultures of Nitrosomonas europaea were maintained as described by Koops et al. (18). E. coli TOP10F′ cells (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.) were grown overnight in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (31) at 37°C under agitation. For fixation, cells of all species were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then incubated for 3 h in 3% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) as described by Amann (3). Fixed cells were washed again in PBS and stored at 4°C in PBS until they were used (normally within 3 days after fixation). For long-term storage, the cells were resuspended in a 1:1 mixture of PBS and 96% (vol/vol) ethanol and kept at −20°C.

Activated sludge was obtained from the secondary aerated nitrification basin (27,144 m3) of the Munich II wastewater treatment plant (one million population equivalents). Then 12.5 ml of activated sludge was fixed immediately after sampling by adding 37.5 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde. After 5 h of incubation at 4°C, the activated sludge was centrifuged for 5 min at 4,550 × g, and the supernatant containing the fixative was discarded. Subsequently, the sludge pellet was washed with PBS and finally resuspended in 12.5 ml (the original sample volume) of a 1:1 mixture of PBS and 96% (vol/vol) ethanol. Samples were stored at −20°C.

Cell concentration of pure cultures.

The numbers of cells per milliliter in the fixed pure cultures of C. testosteroni, G. asaii, and N. europaea were determined with a Neubauer cell counting chamber (Paul Marienfeld GmbH, Bad Mergentheim, Germany) following the instructions of the manufacturer.

The cell concentrations of E. coli cultures were inferred from the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) using a DU 650 spectrophotometer (Beckman, Fullerton, Calif.). For calibration, an E. coli TOP10F′ overnight culture was diluted by factors of 10−5 to 10−7, the OD600 of these dilutions was measured, and aliquots were streaked onto petri dishes with solid LB medium. The numbers of CFU were correlated with the OD600 for each dilution, and the resulting conversion factor (5.5 × 108 CFU ml−1 per OD600 unit) was used to calculate the concentration of E. coli cultures based on their OD600 in all following experiments. It is important to note that E. coli LB overnight cultures contain insignificant numbers of nonviable cells (40). In addition, microscopic observation of the E. coli culture used showed that the vast majority of cells occurred as single cells.

Spiking of pure culture mixtures and activated sludge with E. coli cells.

Overnight cultures of C. testosteroni and G. asaii (100 ml) were harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 4,550 × g and fixed with paraformaldehyde as described above. The cell densities in these concentrated stock solutions were determined using the Neubauer chamber. Cell densities of E. coli overnight cultures were determined photometrically, and E. coli cells were concentrated and fixed with paraformaldehyde as described above. Subsequently, different 1-ml cell mixtures containing 6.3 × 107 C. testosteroni and 3.7 × 107 G. asaii cells as well as 106, 107, 108, or 109 E. coli cells were prepared in 50% PBS–ethanol (EtOH) (vol/vol). In addition, a 1-ml cell mixture containing 6.3 × 107 C. testosteroni and 3.7 × 107 G. asaii cells but without E. coli cells was prepared in 50% PBS–EtOH (vol/vol).

Nitrifying activated sludge was spiked with different amounts of E. coli using the following protocol. One milliliter of paraformaldehyde-fixed activated sludge samples was centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 × g. The supernatant was removed, and the activated sludge was resuspended in 1 ml of PBS containing either 106, 107, 108, or 109 paraformaldehyde-fixed E. coli cells and mixed by vortexing (10 s). In an additional experiment, 1.7 × 108 paraformaldehyde-fixed N. europaea cells were added to the paraformaldehyde-fixed sludge prior to the centrifugation step. Finally, all spiked activated sludge samples were centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 × g. The supernatant was carefully removed, and the sludge was resuspended in 1 ml of 50% PBS–EtOH (vol/vol).

FISH.

The defined mixtures of pure cultures were spotted onto microscope slides (Paul Marienfeld GmbH, Bad Mergentheim, Germany) and allowed to dry at 46°C. Afterwards, the slides were immersed for 2 to 3 s in molten 0.5% agarose (Gibco-BRL ultrapure agarose; Life Technologies, Paisley, Scotland) at 37°C. The slides were then placed on ice until the agarose had solidified. Excess agarose on the back side of the slides was removed, and the samples were dehydrated in 50, 80, and 96% (vol/vol) ethanol for 5 min each. The agarose coating was applied to minimize cell loss during the following hybridization and washing steps. After an additional drying step at room temperature, whole-cell hybridization was performed as described by Manz et al. (22).

A different protocol was developed for the treatment of activated sludge samples prior to FISH. The sludge was prepared on the same type of microscope slides, but the spotting and drying procedures were repeated three times to obtain a thick layer of sludge flocs on the slide surface. The average sample thickness was about 50 μm and thus did not hamper laser penetration in the subsequent CLSM analyses. Afterwards, the slides were immersed in agarose and hybridized as described above. The thick layer of sludge flocs was required (i) to record as many target cells as possible in order to improve the accuracy of the measurements and (ii) to avoid bias in the quantification of planktonic cells which otherwise would accumulate on the slide surface.

The rRNA-directed oligonucleotide probes used for FISH were 5′ labeled with the dye Fluos [5(6)-carboxyfluorescein-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester] or with one of the sulfoindocyanine dyes indocarbocyanine (Cy3) and indodicarbocyanine (Cy5). Labeled probes and unlabeled competitor oligonucleotides were obtained from MWG (Ebersberg, Germany) or Thermo Hybaid (Interactiva Division, Ulm, Germany). In all experiments, group-specific probes labeled with Cy3 or Fluos were used together with the Cy5-labeled EUB338 probe mix (consisting of probes EUB338, EUB338-II, and EUB338-III) covering the domain Bacteria (9). The probes used, their sequences, and their specificities are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide probe sequences and target organisms

| Probe | Sequence (5′-3′) | Target organisms | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| EUB338 | GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT | Most Bacteria | 4 |

| EUB338-II | GCAGCCACCCGTAGGTGT | Planctomycetales and other Bacteria not detected by EUB338 | 9 |

| EUB338-III | GCTGCCACCCGTAGGTGT | Verrucomicrobiales and other Bacteria not detected by EUB338 | 9 |

| NEU | CCCCTCTGCTGCACTCTA | Most halophilic and halotolerant ammonia oxidizers in the beta-subclass of Proteobacteria | 37 |

| CTE | TTCCATCCCCCTCTGCCG | Used as unlabeled competitor with probe NEU | 37 |

| Nso1225 | CGCCATTGTATTACGTGTGA | All known ammonia oxidizers in the beta-subclass of Proteobacteria except N. mobilis | 25 |

| ALF1b | CGTTCG(C/T)TCTGAGCCAG | Alpha-subclass of Proteobacteria | 22 |

| BET42a | GCCTTCCCACTTCGTTT | Beta-subclass of Proteobacteria | 22 |

| GAM42a | GCCTTCCCACATCGTTT | Gamma-subclass of Proteobacteria | 22 |

Microscopy and digital image analysis.

After in situ hybridization, the microscope slides were embedded in Citifluor AF1 (Citifluor, Canterbury, United Kingdom). Pictures of fluorescent cells were recorded using a CLSM (LSM 510, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). For detection of Cy3- and Cy5-labeled cells, two helium-neon lasers (543 nm and 633 nm, respectively) and, for Fluos-labeled cells, an argon laser (450 to 514 nm) was used. For each microscope field, fluorescence conferred by the different probes was recorded in separate images. For each hybridization experiment, 30 microscope fields at random positions and in random focal planes were recorded using a Zeiss Plan-Neofluar 40×/1.3 oil objective. This procedure (30 images at low magnification) allows us to record a high number of probe-target cells and thus to accurately determine the relative abundance of heterogeneously distributed probe-target cells in activated sludge samples (8). All pictures acquired corresponded to optical sections of 1-μm thickness obtained by adjusting the pinhole diameter of the CLSM accordingly. They were recorded as 8-bit images of 512 by 512 pixels with a resolution of 1.6 by 1.6 pixels per μm.

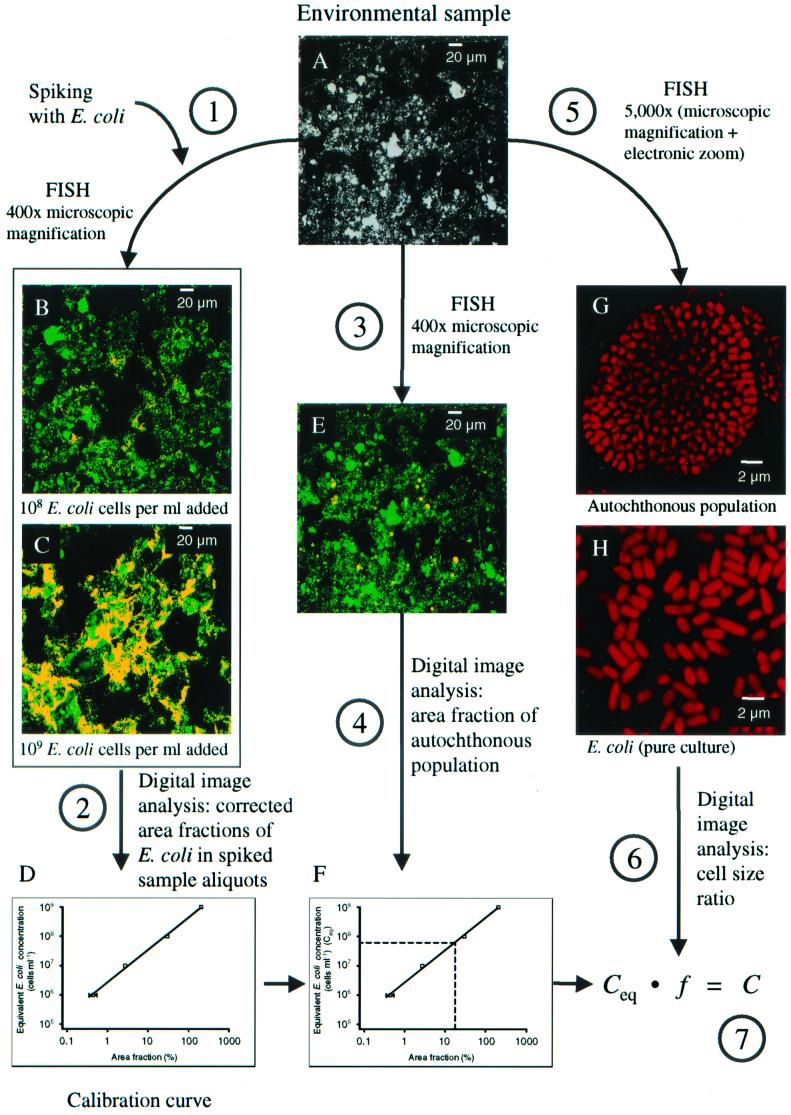

For each sample analyzed, detector gain, amplification offset, and amplification gain settings were selected which allowed detection of all probe-labeled cells with an intensity between 20 and 255. Special attention was paid to optimize microscopic parameter settings so that the images of those cells detected by the specific probes were congruent with their counterparts in the picture with the EUB338 probe mix-stained cells (Fig. 1B, C, and E). The cell area quantification (see below) relies on this congruency, because it is assumed that for each quantified cell the same area is measured with the specific and with the universal probes.

FIG. 1.

Principle of the cell quantification method developed in this study. See text for an explanation of steps 1 to 7. (A) Microscopic picture of activated sludge from the Munich II wastewater treatment plant. (B and C) Aliquots of the same activated sludge after spiking with 108 (B) and 109 (C) E. coli cells per ml. FISH was performed with probe GAM42a (red) and the EUB338 probe mix (green). The images containing the fluorescence conferred by the probes were superimposed, and E. coli cells appear yellow due to color blending. (D) Calibration curve generated from corrected cell area fractions of E. coli in spiked sludge aliquots. (E) The same microscopic field as in A, showing simultaneous FISH using probes NEU and Nso1225 (red) and the EUB338 probe mix (green). Cells of ammonia oxidizers appear yellow due to color blending. (F) Graph showing the use of the calibration curve (D) for converting the measured area fraction of an autochthonous population to the equivalent E. coli concentration. (G) Highly magnified optical section through a cell aggregate of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in activated sludge stained by FISH using probes NEU and Nso1225 (red). (H) Highly magnified optical section through E. coli cells from a pure culture stained by FISH using probe GAM42a (red).

It should be noted that cells of a population to be quantified will be recorded as longitudinal sections as well as transverse sections (and various intermediate forms). However, this fact has no significant influence on the quantification accuracy, because both the cells belonging to the indigenous bacterial population which is to be quantified and the E. coli cells used as the internal standard are optically sectioned in random directions. Moreover, the cell areas are determined by analyzing large numbers of probe-stained cells, a procedure significantly lowering the impact of the spatial orientation of individual cells.

The images were then exported as TIFF files by the image acquisition software delivered with the microscope (Zeiss LSM 5, version 2.01). These files were analyzed with the image-processing software (Zeiss Kontron KS400, version 3.0) to measure the combined areas of stained cells within each image as described by Schmid et al. (32). The area fraction of specifically stained cells was calculated as a percentage of the total area of bacteria stained by the EUB338 probe mix in the same optical section.

Determination of cell density.

The cell concentrations of probe-defined indigenous bacterial populations in a sample were calculated using a seven-step procedure. First, aliquots of the sample (e.g., activated sludge, Fig. 1A) were spiked with E. coli (106 to 109 cells ml−1) as described above (Fig. 1, step 1), and the spiked aliquots were stained by FISH using probe GAM42a and the EUB338 probe mix (Fig. 1B and C). The area fraction of the E. coli cells in each spiked aliquot was determined by digital image analysis (Fig. 1, step 2). For activated sludge samples, the area fraction of the inherent γ-Proteobacteria was measured in sludge aliquots without addition of E. coli cells. The area fraction of these indigenous cells was subsequently subtracted from the area fraction measured with probe GAM42a in the spiked aliquots to obtain the area occupied by E. coli. Since spiking the samples with E. coli increased not only the area fraction of the cells stained by probe GAM42a but also the total area of all bacteria, the measured E. coli cell area fraction must be corrected to remain directly proportional to the number of added E. coli cells. The corrected area fraction is calculated by the formula

|

1 |

where Aec is the measured and A is the corrected E. coli area fraction (in percent). The corrected area fractions were then plotted in a double-logarithmic graph against the E. coli concentration, and a regression line was calculated based on these data points (Fig. 1D). The double-logarithmic transformation was necessary to meet a requirement for linear regression, i.e., an equal variance for all measurements. The regression line was used to calculate the “equivalent E. coli concentrations” from the area fractions of specifically labeled bacterial populations (e.g., ammonia oxidizers stained within activated sludge by FISH; Fig. 1, step 3, and Fig. 1E) in unspiked aliquots of the samples by applying the following equation (Fig. 1, step 4, and Fig. 1F):

is the corrected E. coli area fraction (in percent). The corrected area fractions were then plotted in a double-logarithmic graph against the E. coli concentration, and a regression line was calculated based on these data points (Fig. 1D). The double-logarithmic transformation was necessary to meet a requirement for linear regression, i.e., an equal variance for all measurements. The regression line was used to calculate the “equivalent E. coli concentrations” from the area fractions of specifically labeled bacterial populations (e.g., ammonia oxidizers stained within activated sludge by FISH; Fig. 1, step 3, and Fig. 1E) in unspiked aliquots of the samples by applying the following equation (Fig. 1, step 4, and Fig. 1F):

|

2 |

where Ceq is the equivalent E. coli concentration of the bacterial population (in cells per milliliter), A is the measured area fraction of this population, m is the slope, and b is the ordinate intercept of the regression line.

Finally, Ceq was converted to the real concentration of the bacterial population by taking into consideration differences in size between E. coli and the probe-target population. This conversion was accomplished by measuring the average area of single E. coli cells and of single cells belonging to the probe-target population of interest. For this purpose, images that contained single cells of E. coli and of the probe-target population were acquired at a high magnification (×5,000) with a resolution of 55.6 by 55.6 pixels per μm (Fig. 1, step 5, and Fig. 1G and H). Then a conversion factor was calculated as the ratio of the average cell areas (Fig. 1, step 6):

|

3 |

where f is the conversion factor, Ā is the average single-cell area of the population whose concentration was to be determined, and Āec is the average single-cell area of E. coli. Eventually, Ceq was converted to the real concentration by multiplication with the conversion factor (Fig. 1, step 7):

|

4 |

where C is the concentration of the bacterial population (in cells per milliliter).

Estimation of in situ substrate turnover rates.

Average substrate turnover rates of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria were estimated based on the measured cell concentrations. The total number of ammonia-oxidizing cells in the aerated nitrifying basin of the municipal Munich II wastewater treatment plant was calculated by multiplying the number of ammonia-oxidizing cells per milliliter of activated sludge by the reactor volume. The amount of ammonia-nitrogen converted to nitrite (in milligrams per hour) was estimated according to the formula

|

5 |

where NH4+t is the transformed ammonia-nitrogen (in milligrams per hour), NH4i+ is the ammonia-nitrogen concentration in the influent (in milligrams per cubic meter), NH4e+ is the ammonia-nitrogen concentration in the effluent (in milligrams per cubic meter), r is the reactor influent rate (7,858 m3 h−1), and 0.9 is a correction factor.

The estimated correction factor takes into account that ammonia is removed from the sewage via autotrophic nitrification but also via adsorption (27) and assimilation (activated sludge models 1 to 3 [12–14]). The estimated amount of ammonia oxidized autotrophically was converted from milligrams per hour to femtomoles per hour and was divided by the total number of ammonia-oxidizer cells in the reactor to obtain the substrate turnover rate in femtomoles of ammonia transformed to nitrite per hour and per cell.

RESULTS

Preparation of the samples and spiking with E. coli

A relatively homogeneous distribution of the added E. coli cells within a spiked sample is critical for obtaining an accurate calibration curve. This is particularly important for the measurements of sludge samples which were amended with relatively small numbers of E. coli. Therefore, the area fractions of E. coli cells added to activated sludge were compared after vigorously vortexing the sludge for 1 min or after homogenizing it with an Ultra-Turrax blender (IKA Labortechnik, Staufen, Germany) treatment (1 min). The sludge was spiked with E. coli either before or after these pretreatments.

The area fraction of E. coli was determined for each sample by FISH with probe GAM42a and the EUB338 probe mix and digital image analysis using the method previously published by Schmid et al. (32). The area fractions were compared to the values measured with spiked sludge that had not been vortexed or homogenized. Neither the kind of pretreatment nor the order of sludge preparation and spiking affected the measured area fractions and their standard deviations (Table 2). Consequently, E. coli cells were simply added to the fixed activated sludge samples without additional pretreatments in all following experiments.

TABLE 2.

Effect of different activated sludge homogenization procedures on area fraction measurements of E. coli cellsa

| Homogenization procedure | Time of cell addition | Measured cell area fraction of E. coli (%) |

|---|---|---|

| None | 2.7 ± 0.9 | |

| Vortex (1 min) | After homogenization | 2.2 ± 0.8 |

| Blender (1 min) | Before homogenization | 2.1 ± 0.7 |

| Blender (1 min) | After homogenization | 2.5 ± 0.8 |

Cells were added (107 cells ml−1) artificially to activated sludge from the Munich II wastewater treatment plant. It should be noted that the E. coli area fractions depicted in this table were not corrected according to equation 1.

Evaluation of the quantification protocol using artificial mixtures of pure cultures.

The developed quantification approach was first tested with bacterial pure cultures. For this purpose, cultures of G. asaii (α-subclass of Proteobacteria) and C. testosteroni (β-subclass of Proteobacteria) were mixed after their cell concentrations had been determined with a Neubauer cell counting chamber. The final cell concentrations in the mixture were 3.7 × 107 ± 0.5 × 107 cells ml−1 for G. asaii and 6.3 × 107 ± 0.2 × 107 cells ml−1 for C. testosteroni (all the confidence limits indicate 95% confidence intervals).

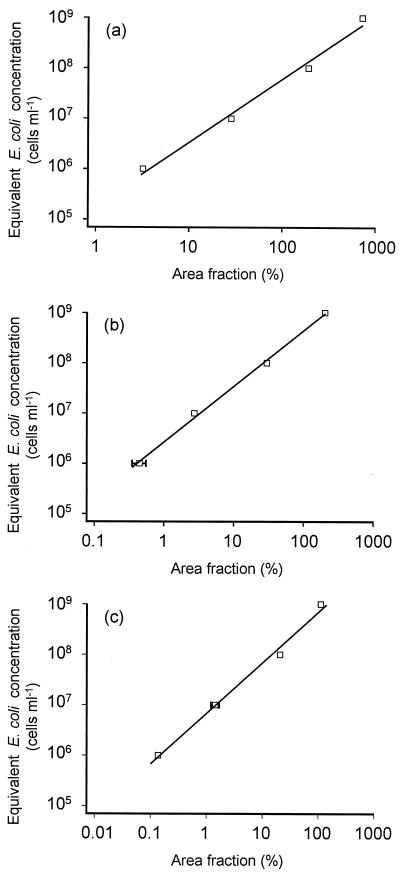

Aliquots of this mixture were supplemented with increasing concentrations of E. coli cells, and a regression line was generated from a graph depicting the relative cell areas of E. coli in the spiked aliquots versus the amount of E. coli cells added (Fig. 2a). This regression line should have a slope of approximately 1, as the corrected area fraction of E. coli cells is expected to be directly proportional to the amount of E. coli cells added. The slope in this and all other determined calibration curves (see also below) was slightly higher than 1 (e.g., 1.25 in Fig. 2a). This implies that small cell additions had a large effect on the area fraction, whereas large additions only had a more moderate effect. Subsequently, the unspiked mixture was hybridized with the EUB338 probe mix and with probe ALF1b or BET42a. It should be noted that the intensities of the fluorescent signals varied considerably among the individual cells of either species, G. asaii and C. testosteroni.

FIG. 2.

Calibration curves used to convert cell area fractions to equivalent E. coli concentrations for the determination of cell concentrations in pure culture mixtures of C. testosteroni and G. asaii (A), in activated sludge from the Munich II wastewater treatment plant (B), and in the same activated sludge after addition of 1.7 × 108 N. europaea cells per ml (C). The general linear equation of these curves is log Ceq = m × log A + b, where Ceq is the equivalent E. coli concentration, A is the cell area fraction, m is the slope, and b is the ordinate intercept of the line. The values of m are 1.253317 (A), 1.105818 (B), and 1.004006 (C). The values of b are 5.27404 (A), 6.429176 (B), and 6.83411 (C). Error bars which are smaller than the marker symbols are not shown.

The cell area fractions of G. asaii and C. testosteroni were measured, and the calibration curve and area correction factor were used to convert the areas to cell concentrations as described above. Table 3 shows the results of this experiment. The concentration determined for G. asaii deviates by 0.4 × 107 cells ml−1 (or 10.8%) from the Neubauer cell chamber count, while the difference between the two quantification methods amounts to 0.8 × 107 cells ml−1 (or 12.7%) for C. testosteroni.

TABLE 3.

Quantification of C. testosteroni and G. asaiia

| Tested species | Area fraction (%) | Equivalent E. coli concn (cells ml−1) | Cell area ratio, E. coli: tested | Tested species (cells ml−1)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell concn (FISH) | Neubauer chamber counts | ||||

| C. testosteroni | 50.7 ± 3.3 | 2.6 × 107 ± 0.2 × 107 | 2.13 | 5.5 × 107 ± 0.5 × 107 | 6.3 × 107 ± 0.2 × 107 |

| G. asaii | 51.6 ± 3.5 | 2.6 × 107 ± 0.3 × 107 | 1.55 | 4.1 × 107 ± 0.4 × 107 | 3.7 × 107 ± 0.5 × 107 |

Confidence limits indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Quantification of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in activated sludge.

The number of autochthonous ammonia-oxidizing bacteria was determined in a nitrifying activated sludge from the Munich II wastewater treatment plant. An equimolar mixture of probes Nso1225 and NEU was used for the in situ detection of ammonia oxidizers of the β-subclass of Proteobacteria. Probe Nso1225 targets all recognized ammonia oxidizers of the β-subclass with the exception of Nitrosococcus mobilis (28). The single central mismatch of N. mobilis is discriminative under stringent conditions, so probe NEU was used in addition. This probe targets N. mobilis and other not yet described ammonia oxidizers from activated sludge which are also not detected by probe Nso1225 (unpublished results).

A first inspection of the analyzed nitrifying activated sludge by FISH with probes NEU and Nso1225 confirmed the occurrence of large amounts of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria of the β-subclass of Proteobacteria. Most ammonia oxidizers were relatively small and formed spherical, tightly packed cell clusters, but others were slightly larger and formed looser aggregates with narrow intercellular cavities.

The cell concentration of the ammonia oxidizers was determined and confirmed in two experiments. First, their area fraction was measured after FISH with both probes NEU and Nso1225 and the EUB338 probe mix. The cell concentration of the autochthonous ammonia oxidizers was then calculated based on a calibration curve that had been generated by spiking of the sludge with E. coli (Fig. 2b). In the second experiment, 1.7 × 108 ± 0.3 × 108 N. europaea cells per ml were added to the activated sludge. The concentration of the ammonia oxidizers (consisting of the autochthonous and the added ammonia oxidizers) in the modified sample was measured by the same procedure as in the original sludge, but a new calibration curve was generated after aliquots of the modified sludge had been spiked with E. coli (Fig. 2c). Finally, the concentration of the autochthonous ammonia oxidizers in the original sludge was subtracted from the concentration of the ammonia oxidizers in the sludge supplemented with the additional N. europaea cells.

For the autochthonous ammonia oxidizers, a cell area fraction of 8.4% ± 1.4% was measured, which corresponds to a concentration of 9.8 × 107 ± 1.9 × 107 cells per ml of activated sludge. Following the addition of 1.7 × 108 ± 0.3 × 108 N. europaea cells per ml, the area fraction of the ammonia oxidizers increased slightly to 9.4% ± 1.4%. It should be noted that different image acquisition parameters were used in the two experiments, making it impossible to compare the area fractions directly. This was necessary because the added ammonia oxidizers showed a weaker fluorescence after FISH than the autochthonous ammonia oxidizers. Furthermore, the added N. europaea cells affect the calibration curve so that the small change in area fraction corresponds to a large difference in cell numbers when using the appropriate new calibration curve. The resulting absolute cell concentrations, however, are comparable.

The concentration of ammonia oxidizers after amendment was 2.3 × 108 ± 0.3 × 108 cells ml−1. The difference between this value and the concentration of the autochthonous ammonia oxidizers amounts to 1.3 × 108 cells ml−1 which should be equal to the 1.7 × 108 added N. europaea cells per ml. The deviation between the two values, 4 × 107 cells ml−1, is 22.4% of the cell addition and thus about twice as high as the differences between the cell concentrations measured by the newly developed quantification method and obtained by using the Neubauer chamber for the pure culture mixtures (see above).

Estimated activity of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in activated sludge.

The average rate of ammonia oxidation per autochthonous ammonia-oxidizer cell within the activated sludge was calculated based on the determined concentration of autochthonous ammonia oxidizers. As described above, 9.8 × 107 ± 1.9 × 107 ammonia-oxidizer cells ml−1 were found in the activated sludge. Thus, with a total reactor volume of 27,144 m3 the total amount of ammonia oxidizers in the reactor was 2.7 × 1018 ± 0.5 × 1018 cells.

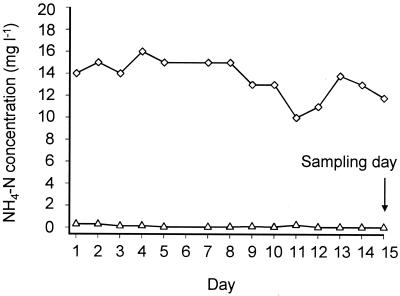

During the last 2 weeks before sampling, the amount of NH4+-N was in the range of 10 to 16 mg liter−1 in the influent and in the range of 0.05 to 0.3 mg liter−1 in the effluent of the plant, respectively (Fig. 3). The average concentrations of NH4+-N in the influent (12.1 mg liter−1) and the effluent (0.08 mg liter−1) of the plant during the last 6 days before sampling were used for the activity estimation. Thus, with a flow rate of 7,858 m3 h−1, 9.5 × 107 mg of NH4+-N h−1 was transformed in the basin. Assuming that 10% of the ammonia was not removed by autotrophic oxidation, the ammonia oxidizers oxidized 8.5 × 107 mg of NH4+-N h−1 which equals 6.1 × 1018 fmol of NH4+ h−1. Consequently, each ammonia-oxidizer cell converted 2.3 ± 0.4 fmol of NH4+ to NO2− per hour if equal activity of all ammonia-oxidizer cells is assumed.

FIG. 3.

Concentrations of ammonia nitrogen in the influent (⋄) and the effluent (▵) of the nitrification basin of the Munich II wastewater treatment plant measured during the last 2 weeks before sampling.

DISCUSSION

Cell quantification methods suitable for microbial ecology should provide precise results for environmental samples containing bacteria which are not homogeneously distributed. Furthermore, they should be independent of cultivation, as most bacteria in natural or engineered systems have hitherto not been isolated (5, 34). A generally applicable method should allow specific enumeration of both single species and higher phylogenetic taxa (e.g., genera or subclasses). New protocols must be tested with regard to these requirements by use of suitable model systems.

In this study, mixtures of pure cultures and an activated sludge sample were used, because these model systems have different advantages when evaluating a new quantification method. The selected pure cultures consisted of uniformly shaped cells, which can easily be counted in a counting chamber to verify the results obtained with the new quantification protocol. On the contrary, activated sludge contains numerous different cultivated and uncultivated prokaryotic species (2, 7, 33) with different morphologies and abundance and thus represents a challenge for any quantification method.

Applicability and accuracy of the newly developed quantification method.

The new quantification method was successfully applied to measure cell concentrations of specific populations in bacterial pure culture mixtures as well as in activated sludge. The results obtained were not expressed as relative abundance based on a reference value such as total cell counts, but as absolute cell numbers per volumetric unit. Since the developed quantification procedure is based on FISH with rRNA-directed oligonucleotide probes, it can be used in any environment that is amenable to FISH analysis. It makes no difference whether the quantified organisms grow as single cells or in dense aggregates as long as individual cells can be resolved microscopically. However, the accuracy of the results obtained with this method depends on a uniform cell size of the target population (see below). Size variations within a target population can be caused by polymorphism of a single species or if probes with a broader specificity were applied for detection of morphologically different bacterial taxa. It should also be noted that the accuracy of this method depends on a relatively homogeneous distribution of reference cells (used for spiking) within the environmental sample. For the analyzed activated sludge sample, this was easily achieved by adding the E. coli cells to the sample followed by a short mixing step. Since composition and density of aggregates or flocs might vary between different environments, special pretreatment (e.g., homogenization) of other samples may be necessary to ensure optimal dispersal of the cells used for spiking.

The cell concentrations measured with the newly developed method deviated in the mixed pure culture experiments by approximately ±10 to 13% and in the experiments with activated sludge by approximately ±22% from the Neubauer chamber counts. In addition to the measurement error of the Neubauer chamber, several difficulties with the area measurement of FISH-stained cells could have caused these discrepancies. First of all, the intensity of the FISH signal is a function of the ribosome content of the target cells. Although most cells in actively growing pure cultures contain high ribosome numbers, we observed that a fraction of the FISH-stained C. testosteroni and G. asaii cells emitted less fluorescence than the majority of the labeled cells. Such differences in the fluorescent signal intensity were even more pronounced between different bacterial populations in the activated sludge sample. The presence of very bright and relatively dark cells in the same sample makes it difficult to find appropriate microscope parameter settings and intensity thresholds during image analysis to differentiate between cells and background. Under such conditions, either the areas of the bright cells are overestimated when the threshold is too low, or the darker cells are not included in the analysis when the threshold is too high. Such errors may still be higher in samples from oligotrophic environments, where the growth rates and ribosome content of indigenous bacterial populations may differ more pronouncedly than in activated sludge.

Problems with fluorescence intensities are also responsible for the upper limit of cell concentrations that can be quantified by the newly developed method. Very high concentrations of probe-target cells (e.g., 108 cells per ml) require that the sample be spiked with E. coli concentrations of between 107 and 109 cells per ml to obtain a calibration curve that spans at least one order of magnitude above and below the cell concentration to be measured. After addition of 109 E. coli cells per ml, however, the E. coli cells formed thick layers of stacked cells on the microscope slides. Following FISH with the EUB338 probe mix, the local fluorescence intensity within these layers of E. coli cells was far higher than the fluorescence intensities observed for most aggregates of autochthonous bacteria. As a consequence, the CLSM detector collected too much light at the locations of the E. coli layers, and the E. coli cells appeared too large in the images with the EUB338 probe mix-stained cells. The sensitivity of the detector could not be reduced to overcome this problem, because then the darker autochthonous bacteria would not have been detected anymore. This problem hampered the precise determination of area fractions for high E. coli cell densities and in consequence affected the precision of the calibration curves. Thick E. coli cell layers were not observed after spiking with smaller amounts of E. coli than 109 cells per ml. The quantification accuracy can thus be expected to be higher for lower concentrations of probe-target cells that do not require spiking of the sample with 109 E. coli cells per ml to obtain a suitable calibration curve.

Furthermore, the conversion of the equivalent E. coli concentration to the real concentration of the quantified population is a possible source of measurement error. The ratio of the average cell areas is used as the conversion factor, but even in pure cultures cell size, and therefore the cell area, may vary considerably. This problem could have contributed to the observed differences between Neubauer chamber counts and the counts inferred from the novel quantification method. In complex systems like activated sludge, cell size variation of probe-target bacteria is frequently observed. Therefore, application of the developed quantification method is recommended for quantification of probe-defined groups of microorganisms that do not show pronounced differences in size, like the two populations of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria detected in this study.

Despite these possible sources of error, the novel FISH-based quantification method constitutes a straightforward and precise method to determine the absolute numbers of microorganisms in different environments and is especially useful for samples containing biofilms or aggregates. The accuracy of the method is demonstrated by the highly similar cell concentrations obtained using the well-established Neubauer chamber counts and the novel FISH-based quantification method for pure culture mixtures as well as for an activated sludge which was amended with a defined number of N. europaea cells.

The utility of the developed quantification method to enumerate bacteria in samples where cells are not homogeneously distributed was illustrated by quantification of autochthonous ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in a nitrifying activated sludge. Based on the absolute numbers of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria obtained, their average activity in the municipal activated sludge sample was estimated to be 2.3 ± 0.4 fmol of NH4+ cell−1 h−1, a value which is within the range of per cell activities measured with pure cultures of N. europaea (1.24 to 23 fmol of NH4+ cell−1 h−1) (20). Compared to manual counting of probe-labeled cells by microscopy (21, 24, 34, 35), the new semiautomatic method is less tedious and not negatively affected by aggregates or cell clusters, and its measured standard error is lower.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by Sonderforschungsbereich 411 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Research Center of Fundamental Studies of Aerobic Biological Wastewater Treatment). The International Workshop on New Techniques in Microbial Ecology (INTIME), where the basic concept of this study was outlined, is acknowledged as a forum encouraging the realization of joint projects between the University of Aarhus, the University of Aalborg, and the Technische Universität München.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alfreider A, Pernthaler J, Amann R, Sattler B, Glöckner F O, Wille A, Psenner R. Community analysis of the bacterial assemblages in the winter cover and pelagic layers of a high mountain lake by in situ hybridization. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2138–2144. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.6.2138-2144.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann R, Snaidr J, Wagner M, Ludwig W, Schleifer K H. In situ visualization of high genetic diversity in a natural microbial community. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3496–3500. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3496-3500.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amann R I. In situ identification of microorganisms by whole cell hybridization with rRNA-targeted nucleic acid probes. In: Akkeman A D C, van Elsas J D, de Bruigin F J, editors. Molecular microbial ecology manual. 3.3.6. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1995. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amann R I, Binder B J, Olson R J, Chisholm S W, Devereux R, Stahl D A. Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1919–1925. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.6.1919-1925.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amann R I, Ludwig W, Schleifer K-H. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloem J, Veninga M, Shepherd J. Fully automatic determination of soil bacterium numbers, cell volumes, and frequencies of dividing cells by confocal laser scanning microscopy and image analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:926–936. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.3.926-936.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bond P L, Hugenholtz P, Keller J, Blackall L L. Bacterial community structures of phosphate-removing and nonphosphate-removing activated sludges from sequencing batch reactors. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1910–1916. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.5.1910-1916.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouchez T, Patureau D, Dabert P, Juretschko S, Doré J, Delgenès P, Moletta R, Wagner M. Ecological study of a bioaugmentation failure. Environ Microbiol. 2000;2:179–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2000.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daims H, Brühl A, Amann R, Schleifer K-H, Wagner M. The domain-specific probe EUB338 is insufficient for the detection of all Bacteria: Development and evaluation of a more comprehensive probe set. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1999;22:434–444. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(99)80053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeLong E F, Taylor L T, Marsh T L, Preston C M. Visualization and enumeration of marine planktonic archaea and bacteria by using polyribonucleotide probes and fluorescent in situ hybridization. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:5554–5563. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.12.5554-5563.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glöckner F O, Amann R, Alfreider A, Pernthaler J, Psenner R, Trebesius K-H, Schleifer K-H. An in situ hybridization protocol for detection and identification of planctonic bacteria. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1996;19:403–406. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gujer W, Henze M, Mino T, van Loosdrecht M. Activated sludge model no. 3. Water Sci Tech. 1999;39:183–193. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henze M, Grady C P L, Gujer W, Marais G v R, Matsuo T. A general model for single-sludge wastewater treatment systems. Water Res. 1987;21:505–515. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henze M, Gujer W, Mino T, Matsuo T, Wentzel M C, Marais G v R. Activated sludge model no. 2. IAWQ Scientific and Technical Reports No. 3. London, England: Pergamon Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heydorn A, Nielsen A T, Hentzer M, Sternberg C, Givskov M, Ersboll B K, Molin S. Quantification of biofilm structures by the novel computer program COMSTAT. Microbiology. 2000;146:2395–2407. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-10-2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hicks R E, Amann R I, Stahl D A. Dual staining of natural bacterioplankton with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and fluorescent oligonucleotide probes targeting kingdom-level 16S rRNA sequences. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2158–2163. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.7.2158-2163.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kämpfer P, Erhart R, Beimfohr C, Böhringer J, Wagner M, Amann R. Characterization of bacterial communities from activated sludge: culture-dependent numerical identification versus in situ identification using group- and genus-specific rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes. Microb Ecol. 1996;32:101–121. doi: 10.1007/BF00185883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koops H-P, Böttcher B, Möller U C, Pommering-Röser A, Stehr G. Classification of eight new species of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria: Nitrosomonas communis sp. nov., Nitrosomonas ureae sp. nov., Nitrosomonas aestuarii sp. nov., Nitrosomonas marina sp. nov., Nitrosomonas nitrosa sp. nov., Nitrosomonas eutropha sp. nov., Nitrosomonas oligotropha sp. nov., and Nitrosomonas halophila sp. nov. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:1689–1699. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuehn M, Hausner M, Bungartz H-J, Wagner M, Wilderer P A, Wuertz S. Automated confocal laser scanning microscopy and semiautomated image processing for analysis of biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4115–4127. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.11.4115-4127.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laanbroek H J, Gerards S. Competition for limiting amounts of oxygen between Nitrosomonas europaea and Nitrobacter winogradskyi grown in mixed continuous cultures. Arch Microbiol. 1993;159:453–459. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Llobet-Brossa E, Rosselló-Mora R, Amann R. Microbial community composition of wadden sea sediments as revealed by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2691–2696. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.7.2691-2696.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manz W, Amann R, Ludwig W, Wagner M, Schleifer K-H. Phylogenetic oligodeoxynucleotide probes for the major subclasses of proteobacteria: problems and solutions. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1992;15:593–600. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manz W, Szewzyk U, Ericsson P, Amann R, Schleifer K-H, Stenström T-A. In situ identification of bacteria in drinking water and adjoining biofilms by hybridization with 16S and 23S rRNA-directed fluorescent oligonucleotide probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2293–2298. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.7.2293-2298.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manz W, Wagner M, Amann R, Schleifer K-H. In situ characterization of the microbial consortia active in two wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 1994;28:1715–1723. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mobarry B K, Wagner M, Urbain V, Rittmann B E, Stahl D A. Phylogenetic probes for analyzing abundance and spatial organization of nitrifying bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2156–2162. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.6.2156-2162.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neef A, Zaglauer A, Meier H, Amann R, Lemmer H, Schleifer K-H. Population analysis in a denitrifying sand filter: conventional and in situ identification of Paracoccus spp. in methanol-fed biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4329–4339. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.12.4329-4339.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nielsen P H. Adsorption of ammonium to activated sludge. Water Res. 1996;30:762–764. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purkhold U, Pommering-Röser A, Juretschko S, Schmid M C, Koops H-P, Wagner M. Phylogeny of all recognized species of ammonia oxidizers based on comparative 16S rRNA and amoA sequence analysis: implications for molecular diversity surveys. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:5368–5382. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.12.5368-5382.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramsing N B, Fossing H, Ferdelman T G, Andersen F, Thamdrup B. Distribution of bacterial populations in a stratified fjord (Mariager Fjord, Denmark) quantified by in situ hybridization and related to chemical gradients in the water column. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1391–1404. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.4.1391-1404.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ravenschlag K, Sahm K, Amann R. Quantitative molecular analysis of the microbial community in marine arctic sediments (Svalbard) Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:387–395. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.1.387-395.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmid M, Twachtmann U, Klein M, Strous M, Juretschko S, Jetten M, Metzger J W, Schleifer K-H, Wagner M. Molecular evidence for a genus-level diversity of bacteria capable of catalyzing anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2000;23:93–106. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(00)80050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snaidr J, Amann R, Huber I, Ludwig W, Schleifer K-H. Phylogenetic analysis and in situ identification of bacteria in activated sludge. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2884–2896. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2884-2896.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagner M, Amann R, Lemmer H, Schleifer K-H. Probing activated sludge with oligonucleotides specific for Proteobacteria: inadequacy of culture-dependent methods for describing microbial community structure. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1520–1525. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1520-1525.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner M, Erhart R, Manz W, Amann R, Lemmer H, Wedl D, Schleifer K-H. Development of an rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probe specific for the genus Acinetobacter and its application for in situ monitoring in activated sludge. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:792–800. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.3.792-800.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner M, Hutzler P, Amann R. 3-D analysis of complex microbial communities by combining confocal laser scanning microscopy and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) In: Wilkinson M H F, Schut F, editors. Digital image analysis of microbes. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1998. pp. 467–486. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner M, Rath G, Amann R, Koops H-P, Schleifer K-H. In situ identification of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1995;18:251–264. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wallner G, Erhart R, Amann R. Flow cytometric analysis of activated sludge with rRNA-targeted probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1859–1866. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.5.1859-1866.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wallner G, Fuchs B, Spring S, Beisker W, Amann R. Flow sorting of microorganisms for molecular analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4223–4231. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4223-4231.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zambrano M M, Siegele D A, Almirón M, Tormo A, Kolter R. Microbial competition: Escherichia coli mutants that take over stationary phase cultures. Science. 1993;259:1757–1760. doi: 10.1126/science.7681219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]