Abstract

Parental domestic violence and abuse (DVA), mental ill-health (MH), and substance misuse (SU) are three public health issues that tend to cluster within families, risking negative impacts for both parents and children. Despite this, service provision for these issues has been historically siloed, increasing the barriers families face to accessing support. Our review aimed to identify family focused interventions that have combined impacts on parental DVA, MH, and/or SU. We searched 10 databases (MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Embase, CINAHL, Education Research Information Centre, Sociological Abstracts, Applied Social Sciences Index & Abstracts, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, Web of Science Core Collection, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) from inception to July 2021 for randomised controlled trials examining the effectiveness of family focused, psychosocial, preventive interventions targeting parents/carers at risk of, or experiencing, DVA, MH, and/or SU. Studies were included if they measured impacts on two or more of these issues. The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool 2 was used to quality appraise studies, which were synthesised narratively, grouped in relation to the combination of DVA, MH, and/or SU outcomes measured. Harvest plots were used to illustrate the findings. Thirty-seven unique studies were identified for inclusion. Of these, none had a combined positive impact on all three outcomes and only one study demonstrated a combined positive impact on two outcomes. We also found studies that had combined adverse, mixed, or singular impacts. Most studies were based in the U.S., targeted mothers, and were rated as ‘some concerns’ or ‘high risk’ of bias. The results highlight the distinct lack of evidence for, and no ‘best bet’, family focused interventions targeting these often-clustered risks. This may, in part, be due to the ways interventions are currently conceptualised or designed to influence the relationships between DVA, MH, and/or SU.

Trial registration: PROSPERO registration: CRD42020210350.

Introduction

Parental domestic violence and abuse (DVA; defined as violence and abuse between parents/caregivers), mental ill-health (MH; defined as common mental health disorders experienced by parents/caregivers), and substance misuse (SU; defined as alcohol and drug use experienced by parents/caregivers) are three commonly experienced adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in the UK [1–3] and worldwide [4–8] (see S1 Appendix for full definitions). There is evidence to suggest that DVA, MH, and SU not only co-occur (i.e., happen in the same time and space; [9]) but also cluster (i.e., are associated with one another, interact, and modify/reinforce the risk of the other occurring; [9]) [10–16]. Families experiencing a combination of these issues are likely to be particularly vulnerable and in need of targeted support [17, 18]. At a conservative estimate, 3.6% of children in the UK are living in households where all three issues are present [19], which has likely been exacerbated by COVID-19 and the resulting government-related restrictions [20–22]. This is concerning given that these issues can have a negative impact on parents’ health, parenting capacity [23, 24], and risk of child maltreatment [25–27]. Additionally, children experiencing these ACEs within the family are at increased risk of developing problems themselves with internalising and externalising behaviour during childhood [28] and violence, MH, and SU later on in life [24, 29, 30].

Although the clustering of risk is likely to require a response that addresses the mechanisms for these outcomes in combination [31], service provision and commissioning of services for DVA, MH, and SU remain largely siloed [32–34]. This creates additional barriers to access for families experiencing a combination of these issues and results in provision that fails to address the complexity of families’ needs [18, 35, 36]. In light of this, recent UK reports have emphasised a need for more interdisciplinary working between services targeting these issues, particularly within the family context [32, 36, 37]. This has led to initiatives such as the ‘Troubled Families’ programme [38, 39] and changes in the way some local authorities (LAs) commission services [40, 41]. For example, several LAs have created ‘group alliances’ funding services that respond to needs in multiple domains (see http://lhalliances.org.uk/).

While policy and practice communities are making strides to support families at risk of, or experiencing, clustered parental DVA, MH, and SU, evidence-based guidance for choice of intervention is lacking. Systematic reviews have tended to examine the effectiveness of family focused or psychosocial interventions targeting DVA, MH, and SU in isolation (e.g., [42, 43–45]). Promising approaches include advocacy, counselling/therapy, and skill-building for DVA [43, 46], counselling/therapy and home-based approaches for MH [45], and brief interventions, intensive case management, and motivational approaches for SU [44]. However, findings are often mixed or limited which may partly reflect failure to address co-occuring or clustering issues in combination [47]. Furthermore, studies and reviews that have examined combined impacts have focused on risk dyads in adults, such as DVA and MH [48], DV and SU [49], or MH and SU [50, 51], rather than all three combined or focusing on parents/families specifically. While recognising the limited evidence-base, such reviews have highlighted the potential importance of integrated interventions addressing issues in combination, trauma-informed approaches, and tailoring of interventions to meet individual needs.

This review aims to fill the gap in the evidence-base by examining whether interventions are effective in impacting outcomes in combination and, if so, what are the current ‘best bet’ family focused interventions. This review is the first of its kind and reflects current UK and global priorities for focusing on prevention [52, 53]. Our review aims to examine whether preventive, psychosocial, family focused interventions have combined impacts on parental DVA, MH, and/or SU.

Methods

This systematic review is reported in line with PRISMA guidelines [54] (S1 Appendix). The protocol for this review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020210350) and the full protocol is publicly available on the first author’s staff profile page (https://arc-swp.nihr.ac.uk/about-penarc/people/kate-allen/).

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: 1) employed a randomised controlled trial (RCT) design; 2) targeted a population that included parents/carers at risk of, or experiencing, one or more of DVA (restricted to physical, sexual, emotional, coercive control, or economic violence and abuse between parents/caregivers), MH (restricted to common mental health disorders experienced by parents/caregivers), and/or SU (restricted to alcohol and/or drug misuse or dependence experienced by parents/caregivers), or targeted the children in their care; 3) examined the effectiveness of an intervention that was family focused, psychosocial and preventive, aiming to prevent or reduce parental DVA, MH and/or SU or the negative impact of these experiences on the children in their care; and 4) measured two or more of the following outcomes: DVA (victimisation/perpetration between parents/caregivers), MH (depression, anxiety, PTSD, panic disorder, OCD, general mental health of parents/caregivers), or SU (alcohol, drug use, general SU of parents/caregivers) (S1 Appendix).

Search strategy

Our search strategy was developed in consultation with AB, an information specialist within the PenARC evidence synthesis team at the University of Exeter, and was conducted by KA. We searched ten electronic databases (MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Embase, CINAHL, Education Research Information Centre (ERIC), Sociological Abstracts, Applied Social Sciences Index & Abstracts (ASSIA), ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, Web of Science Core Collection, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)) from inception to March 2020. Our search terms fell into five main categories combined as follows: [DVA OR MH OR SU] AND parents/family AND RCTs. All searches involved free-text searching and database specific MeSH subject headings (where appropriate), and were limited to ‘English Language’ only (S1 Appendix). We updated this search in July 2021 to ensure recent literature was captured.

Backwards and forwards citation-chasing was conducted on the included studies to identify any other relevant literature that may not have been captured by the search. In addition, study authors were contacted in order to identify any additional papers relating to RCTs included within the review.

Study selection

Search results were imported to EndNote V9 [55] and duplicates removed manually, matching records on; 1) author and title; 2) author and year; and 3) title and year. We then ran records through EPPI-Reviewer 4 RCT classifier [56] to categorise the search results based on their likelihood of reporting on an RCT and transferred back to EndNote V9 for screening.

Title and abstract screening was conducted by KA and a second independent reviewer (KF, AG, MF, ET, VB) where studies were classified by EPPI-Reviewer 4 as ≥20% likelihood of employing an RCT, and by KA alone where studies were classified as <20% likelihood of employing an RCT [56]. Full-text screening was conducted by KA and a random 10% were screened by a second independent reviewer (KF and MF) to ensure inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied consistently across studies. In both instances, disagreements were resolved through discussion and/or consultation with a third reviewer (VB).

Data extraction

Data were extracted by KA using a standardised data extraction form (see S1 Appendix) which was piloted prior to use. Extracted data included study details (authors, date, study design, country, primary aim, the proposed relationship between DVA, MH, and SU as described by authors), study sample (recruitment setting, sample characteristics such as number, age, gender, and ethnicity, and study inclusion/exclusion criteria), intervention and control group details (guided by the TIDIER checklist; [57]), data collected on DVA, MH, and/or SU (data collection time-points, measures, and results), data collected on child MH outcomes (data collection time-points, measures, and results), other outcomes assessed (outcomes and measures), and authors’ conclusions and recommendations for future research. Data from a random 10% of included studies were also extracted by a second independent reviewer (KF and AG) to ensure accuracy. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and/or consultation with a third reviewer (VB).

Data were sought from the articles included in the review including associated supplementary material containing information on DVA, MH, and/or SU and weblinks provided in text to any additional information on these outcomes.

Quality appraisal

KA quality-appraised the studies using the Risk of Bias Tool 2 (RoB2) for RCTs [58] and cluster RCTs [59] and a random 10% were quality appraised by a second independent reviewer (VB, G.J.M-T, TF, CB). Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Our review uses terms from the RoB2 to refer to study quality. The RoB2 assesses the risk of bias arising from the randomisation process, identification and recruitment of participants to cluster RCTs (in the case of cluster RCTs only), assignment to the intervention group, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and selection of reported results [58, 59].

Data analysis

The significant heterogeneity in intervention types, outcome measures and length of follow-up precluded meta-analysis so we conducted a synthesis without meta-analysis in line with SWIM guidelines [60].

Standardised mean differences (SMD) (i.e., Cohen’s d) and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for each primary outcome of interest within each study using the information available. These were calculated between intervention and control groups at post-intervention (operationalised as the closest data-collection point following intervention delivery) and follow-up (operationalised as the latest possible timepoint following data collection at post-intervention) using the Campbell Collaboration Effect Size Calculator [61] and guidance from Borenstein et al. [62] for conversion of odds ratios and calculation of SMD variance, where applicable. The direction of SMDs and CIs were multiplied by -1 where appropriate. Where studies reported no significant differences between groups and provided no further data, SMDs were imputed as 0 and SMD variance was estimated using Borenstein et al. [62] formula using imputed SMD and reported sample size [63, 64]. Four studies did not provide adequate information to allow us to calculate SMD, 95% CIs, and determine the direction of the SMD for two or more outcomes at post-intervention [65–68] and four at follow-up [66–69]. For these studies, findings are reported narratively based on the authors report. One study did not present sufficiently detailed results in text or tables and therefore, study authors were contacted to request means and SDs at post-intervention [70].

Our primary outcomes included parental DVA, MH, and SU. Where there were multiple measures assessing the same outcome, a decision tree was followed to decide which data to synthesise, giving priority to; 1) measures collecting and presenting data on the time-point of interest (i.e., post-intervention or latest follow-up); 2) continuous outcomes; 3) imputed data; 4) analyses controlling for the most covariates. Where multiple measures met these criteria, or where only dichotomous outcomes were available, all were included within the analysis.

We reported findings narratively, grouping studies based on the combination of outcomes measured, as examining combined impacts was the primary aim of the review. We summarised studies using tables which highlighted key study characteristics. Harvest plots were used to illustrate the direction of effect and certainty of effect (i.e., 95% CI are both positive, cross zero, or are both negative) for DVA, MH, and SU outcomes within each study, the number of SMDs these categorisations were based on, and the combination of outcomes each study examined. We also used harvest plots to highlight studies that had combined impacts on two or more outcomes, categorising in terms of whether the effects for DVA, MH, or SU favoured the control (all SMDs favoured control), were mixed (some SMDs favoured control and some favoured intervention), or favoured the intervention (all SMDs favoured the intervention) and highlighting where two or more of DVA, MH, and/or SU outcomes demonstrated SMDs with positive CIs, CIs that crossed zero, or negative CIs. Harvest plots were used as they provide a useful way to organise/synthesise data about differential effects of complex interventions that may not be appropriate for meta-analyses [71].

Patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE)

Patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) of those with experience of DVA, MH, and/or SU, service providers, and commissioners was essential in informing the design and conduct of our review.

Our review focuses on clustering DVA, MH, and SU following calls from commissioners for help in finding better ways to prevent and respond to these issues. The scope of the review was further refined to focus on family focused interventions following direction from those with experience, who highlighted the intergenerational nature of these issues and the importance of working with parents and child when providing support; a view echoed by service providers and commissioners. In addition, almost all those with experience talked about the impact these experiences had on their children (who lived at home, or with whom they had regular contact).

Primary prevention approaches, which seek to intervene early to prevent DVA, MH, and SU later in life, tend to be predominately school based, child focused, and involve measuring changes in attitudes and beliefs rather than social, emotional, and behavioural outcomes (e.g., [72–74]). Therefore, we focused on other levels of prevention to capture family focused interventions that might measure direct impacts on DVA, MH, and SU. Engagement work with LA commissioners highlighted the need to define these preventive interventions as both secondary (targeting individuals/populations at risk of, or experiencing early signs of, a particular issue) and tertiary (preventing negative impacts associated with a particular issue) interventions [75, 76], and to expand the categorisation to include treatment interventions, in recognition of the fact that these interventions often have preventive elements and may be used by commissioners for preventive purposes. This addition considerably expanded the scope of the review, but ensured it was more useful to those who might seek to apply its findings.

Finally, PPIE helped to inform our interpretation and presentation of the results. Collaborators helped to shape how the findings were presented in study characteristics tables (e.g., highlighting the context in which the interventions are situated) and structure the discussion, where we highlight findings believed to be particularly important from a commissioner and service provider perspective.

Results

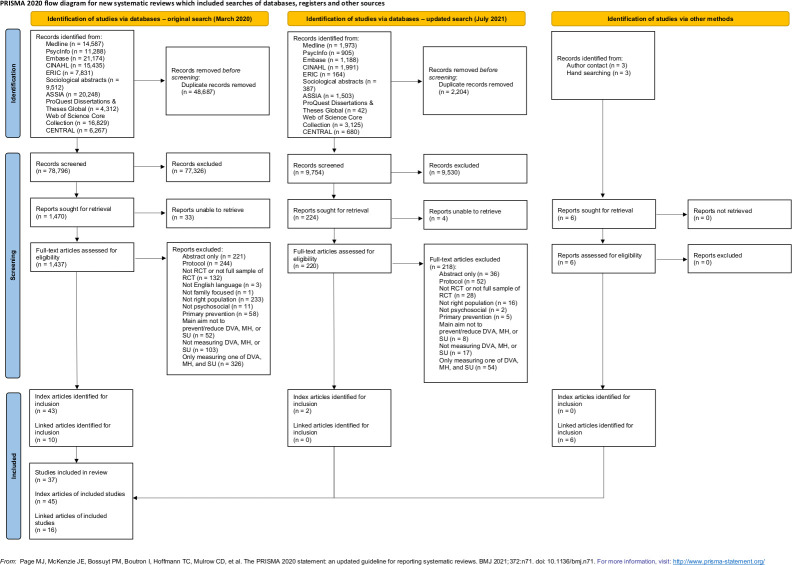

Our original search returned 127,483 results, reduced to 78,796 following de-duplication. In total, 1,470 results were screened on full text, which resulted in 43 index papers and 10 linked papers (i.e., papers linked to included index papers that contained additional information on child outcomes and/or parental DVA, MH, and SU) corresponding to 35 unique studies (Fig 1). A further two eligible studies were identified through an updated search, resulting in a total of 37 unique studies identified for inclusion (Fig 1). Six additional linked papers were identified through contacting the authors/hand searching. Where there are multiple papers associated with one study, we use the primary reference to refer to the study.

Fig 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Study characteristics

Study characteristics are summarised in Tables 1–4. All studies were published as peer-reviewed journal articles bar two PhD theses [77, 78]. Three studies employed a cluster RCT [79–81] instead of an RCT randomised at the individual level and six employed a pilot RCT [65, 82–86] as opposed to a full-sized RCT. The type of control group varied across studies with 15 employing an active control [65–68, 77, 79, 82–85, 87–91], 11 a care as usual control [64, 69, 70, 80, 81, 92–97], six a minimal care control [86, 98–102], and three employing both active and usual care controls [63, 78, 103]. Two studies provided no information on the nature of the control group [104, 105]. Most studies were conducted in the U.S. [63, 64, 66–68, 78, 79, 82–84, 86–89, 91, 92, 95, 98–103, 105], with the remaining studies conducted in Australia [81], Canada [77], South Africa [80], New Zealand [106], China [93], UK [69, 94], Iran [70], Columbia [97], or an undisclosed country most likely to be the U.S. based on author affiliations [65, 85, 90, 104]. Family focused interventions worked with the mother [63, 66, 69, 70, 78–82, 85, 86, 88, 91–94, 98–103, 105, 106], mother and father [65, 77, 83, 87], or parents [68, 97] with the view that this would indirectly impact the child. However, three studies worked directly with the mother and child [64, 89, 104], two with the mother, father, and child [84, 90], and one with a parent and child [95]. No studies worked solely with the child. Studies represented a range of different ethnic groups and, even where participants weren’t specifically targeted due to low socio-economic status (SES), demographic data indicated study populations were experiencing above average levels of low SES (see S1 Appendix).

Table 1. Study characteristics for studies measuring DVA and MH.

| Study characteristics for studies measuring DVA and MH | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Context | Target population | Recruitment setting(s) | Level of prevention | Intervention form and function | Intervention duration and setting | Control(s) | Relationship between DVA/MH/SU | DVA/MH/SU outcomes measured* |

|

4. El-Mohandes et al. (2008) Linked: Kiely et al. (2010); Kiely et al. (2011) (reference number: [92]) |

District of Columbia, U.S. 100% African American |

African American pregnant women (aged 18+, ≤28 weeks gestation) living in district of Columbia who reported one or more of the following: active smoking, environmental tobacco smoke exposure, depression, and/or IPV (physical/sexual violence or scared of current partner). Exclusion criteria: completed pregnancy before baseline interview. |

Community based prenatal clinics. | Treatment | Multicomponent intervention (n = 452) aiming to reduce postpartum risk factors including depression and DVA. Mothers received tailored support from master’s level trained counsellors to suit their needs; for those smoking or experiencing environmental smoke exposure they received an intervention to promote smoking cessation/reduction and environmental smoke avoidance, for those experiencing depression they received an adapted CBT intervention, and for those experiencing IPV they received individualised counselling sessions utilising empowerment theory (adapted from Parker-McFarlane). | Delivered in clinic over a period of at least 12 weeks (4–8 sessions prenatally and 2 optional sessions postpartum, frequency not stated); hosted within a community prenatal clinic. | Usual care control (n = 461). No further information provided. |

Authors describe as uni-directional; experiencing IPV (DVA) is associated with an increased risk of depression, PTSD (MH), alcohol, and illicit drug use (SU). Intervention treats as co-occurring; provide separate support for DVA and MH using separate approaches. |

Post-intervention (10.3 weeks postpartum): DVA = Mothers’ physical assault and sexual coercion victimisation measured using CTS. MH = Mothers’ depression measured using HSCL. No follow-up. |

|

16. Nagle (2002) (reference number: [78]) |

Louisiana, U.S. 54% African American |

First-time pregnant women (<28 weeks gestation) with low income (below 133% federal poverty level). Exclusion criteria: None stated. |

Various; public health units and referrals to nurses from other services (e.g., schools, doctors, community resources). | Tertiary | Home visiting supplement (n = 135) called ‘Nurse Home Visiting Plus’ provided in addition to NFP home visiting intervention aiming to strengthen the mother-child relationship by supporting the mother in their development and parenting and helping them understand the needs and development of their children. Mothers received home visits from a home visiting nurse who was part of a larger team which included a team supervisor, eight home visiting nurses, and a mental health professional with expertise in infant mental health. The mental health professional supported the team and acted as a mental health provider to mothers. | Delivered in home setting over a period of 2+ years (number of sessions not stated, sessions every other week); hosted within home visiting services. | Two groups1: 1) Usual care control (n = 116) who received existing public health services. 2) Active control (n = 106) who received normal home visiting (NFP). |

Author describes as bi-directional; DVA is likely to increase the risk of depression (MH) and likewise, depression (MH) is likely to increase the risk of DVA. Intervention treats as co-occurring; provide separate support for MH and DVA using separate approaches. |

Mid-treatment (6–8 months)2: DVA = mothers’ physical and non-physical victimisation and perpetration related to current partner and ex-partner measured using the Partner Violence Interview. MH = mothers’ depression measured using the BDI. No follow-up. |

|

29. Sullivan et al. (2002) (reference number: [104]) |

Midsize urban city, U.S. (state not stated) Mothers 49% Non-Hispanic White; children 44% African American |

Mothers who have experienced physical violence from intimate partner or ex-partner in the last four months and have at least one child aged between 7–11 years who is living with them and interested in participating in the study. Exclusion criteria: None stated. |

Various; following exit from DVA shelter or when obtaining services from community-based service or state Social Services department. | Tertiary/ secondary/ treatment | Advocacy intervention (n = 45) aiming to improve self-competence of children exposed to DVA, improve mothers’ psychological well-being, and protect against continued DVA. Mothers and children received family tailored strengths-based advocacy intervention from paraprofessionals (female undergraduates). This involved assessing mothers’ and children’s needs and goals and helping mothers to access and utilise community-based support in terms of legal assistance, housing, employment, education, childcare, social support etc. and helping children access recreational activities, supporting them with schoolwork, and/or obtaining material goods. As part of the intervention, children also attended a support and education group which was run by five group leaders who had experience working with children. At the end of the intervention, there was a focus on transferring advocacy-based skills to the mother. | The advocacy part of the intervention was delivered in the home setting/over the telephone over 16 weeks (minimum 36 sessions, at least twice a week) and the children’s support and education group in a community-based setting over 10 weeks (do not state number/frequency of sessions); hosted within community IPV services. | No information given (n = 33). |

Authors describe as uni-directional (theoretical link); women that experience DVA are at risk of experiencing high levels of psychological distress (including anxiety and depression; MH) due to unpredictable and inconsistent violence they experience. Intervention treats as bi-directional; support from advocate is hypothesised to help improve MH and protect against DVA. |

Post-intervention: DVA = mothers’ emotional and physical victimisation measured using a combination of the shortened version of the Index of Psychological Abuse, modified version of CTS, and 12-item scale to assess injury. MH = mothers’ depression measured using the CES-D. Follow-up (4 months post-intervention): Same as above. |

|

30. Taft et al. (2011) (reference number: [81]) |

NW Melbourne, Australia Ethnicity not reported |

Mothers (aged 16+) who were pregnant or had one child aged ≤ 5 and were identified as psychologically distressed (symptoms of depression, anxiety, or frequent attendance taken as an indicator of being at risk of IPV) or had disclosed IPV. Exclusion criteria: Serious MH and not taking medication, English not adequate to provide informed consent (unless spoke Vietnamese).Exclusion criteria: Serious MH and not taking medication, English not adequate to provide informed consent (unless spoke Vietnamese). |

GP practices and Maternal and Child Health Clinics (MCHs). | Secondary/ treatment/ tertiary | Advocacy intervention (n = 113) called ‘MOtherS’ Advocates In the Community’ (MOSAIC) aiming to reduce DVA and/or depression among mothers, strengthen their health and well-being, and strengthen mother-child bond. Mothers received home visits from individually matched paraprofessionals (mentor mothers) who offered advocacy-based support, parenting support and general be-friending in addition to normal clinician care. | Delivered in home setting over a period of 12 months (48 sessions delivered weekly); hosted within primary care. | Usual care control (n = 61) which involved receiving a resource card containing details of family violence services. |

Authors describe as uni-directional; maternal depression (MH) can be a common consequence of IPV (DVA). Intervention treats as bi-directional; support from advocate is designed to provide MH support at same time as advocacy for DVA. |

Post-intervention: DVA = mothers’ physical and emotional victimisation and harassment measured using the CAS. MH = mothers’ depression and general MH measured using the EPDS and SF-36 MH subscale, respectively. No follow-up. |

|

31. Tiwari et al. (2005) (reference number: [93]) |

Hong Kong, China Ethnicity not reported |

Chinese pregnant women (aged 18+, <30 weeks gestation) identified as experiencing DVA by an intimate partner during their first antenatal appointment. Exclusion criteria: None mentioned. |

Antenatal clinics. | Treatment | Empowerment intervention (n = 55) aiming to reduce IPV. Pregnant women received an empowerment-based intervention delivered by a research assistant (who was a trained midwife). The intervention involved giving pregnant women advice on safety, choice making, and problem solving (based on Parker et al.’s empowerment protocol) and also included a component on empathetic understanding (based on Roger’s client-centred therapy) to help increase women’s positive feelings about themselves. At the end of the intervention women received a leaflet covering the information discussed. | Delivered in clinic as a one-off 30-minute session; hosted within antenatal services. | Usual care control (n = 55) which involved receiving wallet sized card containing information on community resources for DVA. |

Authors describe as uni-directional; IPV (DVA) may have a detrimental impact on self-esteem (MH). Intervention treats as bi-directional; DVA and MH addressed concurrently within the same one-off intervention. |

Post-intervention (6 weeks post-delivery): DVA = mothers’ psychological, physical, and sexual victimisation measured by the CTS. MH = mothers’ depression and general MH measured by the EPDS and SF-36 MH subscale, respectively. No follow-up. |

|

35. Zlotnick et al. (2011) (reference number: [86]) |

Rhode Island, U.S. 42.6% Hispanic |

Low income, pregnant women (aged 18–40 years) attending their prenatal care visit who were deemed at risk of MH due to screening positive for experiencing IPV in the past year. Exclusion criteria: meet criteria for current affective disorders, PTSD, or SU on SCID-NP, attending clinic with male partner, currently receiving treatment for MH, only one instance of very minor abuse. |

Primary care clinics and private OBGYN clinic. | Secondary | Therapy (interpersonal psychotherapy) intervention (n = 28) aiming to prevent/reduce PTSD and depression in low-income women who have experienced IPV in the past year. Pregnant women received an interpersonal therapy-based intervention delivered by two study interventionists (trained to deliver scripted intervention). Involved helping women with changing expectations around interpersonal relationships, building and improving their social network and helping them with their transition to motherhood. Over multiple sessions discussed healthy relationships, developing safety plans, developing good support network, the consequences of abuse including risks to MH and SU and what this might look like, support networks, and goal setting. It was also informed by empowerment and stabilisation-based models recommended for IPV. | Delivered in undisclosed setting over a period of less than six weeks (4 sessions prenatally, 1 session postnatally, frequency not stated); not clear who it was hosted by. | Minimal care control (n = 26) involving usual care plus educational material and list of resources for IPV. |

Authors describe as bi-directional; PTSD/depression (MH) are possible consequences of IPV (DVA). Depression/PTSD (MH) may serve to sustain vulnerability of woman to abuse. Intervention treats as bi-directional; target women’s social support for interrupting relationship between DVA and MH (and DVA alone), discuss MH as consequence of DVA, target MH with view this will encourage women to seek help from other services for DVA and establish safety. |

Post-intervention: DVA = women’s physical, psychological, and sexual victimisation measured using CTS2. MH = women’s depression measured using LIFE and EPDS. Women’s PTSD measured using LIFE and Davidson Trauma Scale. Follow-up (10 weeks post-intervention): Same as above. |

|

UPDATE 36. Dinmohammadi et al. (2021) (reference number: [70]) |

Zanjan, Iran Ethnicity not reported |

Pregnant women (aged 18+, ≤27 weeks gestation) who were married, living with their partner, and were experiencing minor/medium levels of DVA. Pregnant women also had to own a cell phone and not be participating in any other classes or counselling. Exclusion criteria: psychological illness, SU (pregnant woman or partner), absent for more than one counselling session. |

Health care setting—government delivered childbirth preparation class. | Treatment | Therapy (solution-focused) intervention (n = 45) aiming to reduce DVA and improve quality of life. Pregnant women received individual solution focused counselling sessions delivered by a researcher. The sessions involved familiarising women with the concept of the solution-focused approach and quality of life, learning how to best interpret events, thinking about opportunities when living as a couple, recognising destructive behaviour patterns, and developing new thoughts and behaviours. | Delivered in health care setting over a period of 6 weeks (6 sessions, once per week); hosted within government delivered childbirth preparation classes. | Usual care control (n = 45) who were offered the intervention after the study was complete. No other information given. |

Authors describe as uni-directional; DVA may lead to problems with MH. Intervention treats as bi-directional; addressing both DVA and MH through solution-focused therapy. |

Post-intervention (6 weeks post-intervention): DVA = women’s physical, psychological, sexual violence and injury-related victimisation using CTS-2. MH = women’s general MH using mental health subscale of SF-36. No follow-up. |

|

UPDATE 37a. Skar et al. (2021)3 (reference number: [97]) |

Chocó Department, Columbia Ethnicity not reported |

Parents of children aged between 3–4 years who were attending one of six child centres and were receiving health services subsidised by the government (due to low-income). Exclusion criteria: did not take part in the programme or sent someone else to complete outcome measures. |

Social services child centres run by Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar (ICBF). | Tertiary | Parenting intervention (n = 59) called ‘International Child Development Programme (ICDP)’ aiming to promote good parenting and strengthen child-parent relationship by influencing parent attitudes, increasing parent self-confidence, and promoting empathy and sensitivity to child’s needs. Parents received ICDP sessions delivered by trained ICDP facilitators. These sessions involved group discussions, role play, home practice (i.e., activities in the home setting between sessions), and reflection on home practice focusing on emotions, communication and regulation related to parent-child interactions. | Delivered in social services child centres over an undisclosed period of time (12 sessions, frequency not stated); hosted within social services. | Usual care control (n = 51) who had access to usual health, nutrition, and educational facilities at the child centre they were attending. |

Authors do not state; do not discuss potential relationship between DVA and MH but do explore this in the analysis suggesting those experiencing DVA are more likely to experience MH. Intervention treats as co-occurring; attempting to address DVA and MH through common risk factor however no recognition that these issues cluster in this context. |

Post-intervention (6 months post baseline): DVA = parents’ physical and psychological victimisation and perpetration using HITS. MH = parents’ general MH using SSQ. No follow-up. |

|

UPDATE 37b. Skar et al. (2021)3 (reference number: [97]) |

Chocó Department, Columbia Ethnicity not reported |

Parents of children aged between 3–4 years who were attending one of six child centres and were receiving health services subsidised by the government (due to low-income). Exclusion criteria: did not take part in the programme or sent someone else to complete measures. |

Social services child centres run by Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar (ICBF). | Tertiary | Parenting supplement (n = 66) called ‘International Child Development Programme (ICDP)’ plus ‘violence curriculum’ (VC) aiming to better prevent violence in the home. Parents receive ICDP as described above (but shortened in duration) and receive additional sessions focusing on violence delivered by trained ICDP facilitators. These additional sessions involve training on child development, violence, legislation and policy, child protection systems, and their role in protecting children. Parents also develop protective strategies and monitoring tools to enable them to do this. | Delivered in social services child centres over an undisclosed period of time (12 sessions: 6 sessions ICDP and 6 sessions VC, frequency not stated); hosted withing social services. | Usual care control (n = 51) who had access to usual health, nutrition, and educational facilities at the child centre they were attending. |

Authors do not state; do not discuss potential relationship between DVA and MH but do explore this in the analysis suggesting those experiencing DVA are more likely to experience MH. Intervention treats as uni-directional DVA focused; primary aim is to reduce DVA to prevent negative impact on children. Improved MH likely to be an additional benefit. |

Post-intervention (6 months post baseline): DVA = parents’ physical and psychological victimisation and perpetration using HITS. MH = parents’ general MH using SSQ. |

NB. Green coloured cells indicate studies that have had, or report to have, combined positive impacts on two or more outcomes. 1 for outcome data we compare intervention to the usual care control. 2 Although there were multiple follow-up timepoints, DVA and MH outcomes were only measured at baseline and mid-treatment. We treat this mid-treatment point as post-intervention within the analysis. 3 Skar et al. (2021) conducted a three-arm RCT examining the effectiveness of a parenting intervention (intervention group 1) and a parenting intervention plus parenting intervention supplement (intervention group 2) as compared to a usual care control group. Therefore, there are two separate entries for this study, one with the parenting intervention as the intervention group and one with the parenting intervention supplement as the intervention group. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; CAS = Composite Abuse Scale; CBT = Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; CTS = Conflict Tactics Scale; DVA = Domestic Violence; EPDS = Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; HITS = Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream; HSCL = Hopkins Symptom Checklist; IPV = Intimate Partner Violence; LIFE = Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Examination; MH = Mental ill-health; NFP = Nurse Family Partnership; PTSD = Post Traumatic Stress Disorder; SF = Short Form; SSQ = Shona Symptom Questionnaire; SU = Substance Misuse.

Table 4. Study characteristics for studies measuring DVA, MH, and SU.

| Study characteristics for studies measuring DVA, MH, and SU | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Context | Population | Recruitment setting(s) | Level of prevention | Intervention form and function | Intervention duration and setting | Control(s) | Relationship between DVA/MH/SU | DVA/MH/SU outcomes measured* |

|

2. Duggan et al. (2007) (reference number: [101]) |

Alaska, U.S. 55% Caucasian |

Families (pregnant or at birth) deemed at risk of child maltreatment due to parental DVA, MH, or SU, or other related factors, scoring ≥25 on Kempe Family Stress Checklist, and able to speak sufficient English to take part in study. Exclusion criteria: Previously enrolled on home visiting intervention. |

Hospitals either prenatally or at birth. | Tertiary | Home visiting intervention (n = 162) called ‘Healthy Start Alaska’ (HSA) aiming to help prevent child maltreatment by promoting positive parenting and child development, and reduce malleable risk factors (i.e., DVA, MH, and SU). Mothers (and fathers where possible) received home visits from trained paraprofessional home visitors. Sessions involved providing parents with information, demonstrating positive parenting practices through role play and reinforcement, helping parents set family-initiated goals within an Individual Family Support plan (IFSP), supporting parents through crises, and recognising and responding to parental DVA, MH, and SU through encouraging parents to seek help from community-based services. | Delivered in home setting over a period of 3+ years (number of sessions varies, frequency varies tends to be weekly in first 6–9 months then less frequently as family functioning improves); hosted within established home visiting sites. | Minimal care control (n = 163) received referrals to other community services (do not state who delivered these referrals). |

Authors describe as uni-directional; coercive relationships (DVA) can make stress unmanageable, and this can lead to depression (MH) and SU (as well as child maltreatment). Intervention treats as co-occurring; separate referrals for DVA/MH/SU. |

Post-intervention (treated as child 2 years of age): DVA = mothers’ physical, psychological, and injury related victimisation / perpetration measured using CTS2. MH = mothers’ depression and general MH measured using CES-D and MHI-5, respectively. SU = mothers’ alcohol and drug use measured using self-report and CAGE (for alcohol use). No follow-up. |

|

3. Duggan et al. (1999; 2004); McFarlane et al., (2013) Linked: Bair-Merritt (2010); Bair-Merritt (2010) (reference number: [105, 114–117]) |

Oahu, Hawaii, U.S. 33.6% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander |

Families (pregnant or at birth) deemed at risk of child maltreatment due to parental DVA, MH, or SU, or other related factors, scoring ≥25 on Kempe Family Stress Checklist, and not currently under child protection services. Exclusion criteria: None stated. |

Hospitals (maternity obstetrical units) either prenatally or at birth. | Tertiary | Home visiting intervention (n = 373) called ‘Hawaii Healthy Start Programme’ (HSP) aiming to help prevent child maltreatment and promote positive child development by improving family functioning. Mothers (and fathers where possible) received home visits from trained paraprofessional home visitors. Sessions involved providing parents with information, demonstrating positive parenting practices through role play and reinforcement, co-developing family-related goals within an Individual Family Support plan (IFSP) which is used as a guide throughout the intervention, supporting parents through crises, and recognising and responding to parental DVA, MH, and SU through providing emotional support and encouraging parents to seek help from community-based services. | Delivered in home setting over a period of 3–5 years (number of sessions varies, frequency varies); hosted within established home visiting sites. | Control (n = 270) services/care received is not described. Test control group (n = 45) included for purposes of funders due to concerns about impact of multiple testing. Only followed up for a few timepoints and are not reported on. |

Authors describe as uni-directional; coercive relationships (DVA) can make stress unmanageable, and this can lead to depression (MH) and SU (as well as child maltreatment). Intervention treats as co-occurring; separate referrals for DVA/MH/SU. |

Post-intervention (child 3 years of age): DVA = mothers’ physical, psychological, and injury related victimisation / perpetration measured using CTS2. MH = mothers’ depression and general MH measured using CES-D and MHI-5, respectively. SU = mothers’ alcohol and drug use measured using self-report and CAGE (for alcohol use). Follow-up (4–6 years post-intervention): Same as above other than mothers’ drug use which was measured using ASI. |

|

5. Fergusson et al. (2006; 2013) Hand linked: Fergusson et al. (2005; 2012) (reference number: [106, 118, 119]) |

Christchurch, New Zealand ~25.8% Mäori (based on those who completed follow-up assessments) |

New parents (within 3 months of childbirth) screened at risk of child maltreatment using Hawaii Healthy Start Program Screening Tool or deemed at risk by nurses responsible for recruitment. Exclusion criteria: None stated. |

Home during visits conducted by Plunkett Nurses who visit families within three months of the birth of a new child (free service). | Tertiary | Home visiting intervention (n = 220) called ‘Early Start Home Visiting’ aiming to improve child health, reduce child abuse, promote positive parenting, maternal health and well-being, and family economic and material well-being. Parents received home visits from family support workers. Initial sessions involved assessing the family’s level of need and strengths, followed by sessions which involve encouraging family led problem-solving to overcome issues and providing general support and mentoring throughout child’s preschool years. | Delivered in the home setting over a period of 3 years (number of sessions and frequency varies depending on family level of need); hosted within established home visiting services. | Usual care control (n = 223) (do not describe who this was provided by or what this involved). |

Authors do not state. Intervention treats as co-occurring; separate aspects of intervention targeting each. |

Post-intervention: DVA = mothers’ physical victimisation measured using CTS2. MH = mothers’ depression measured using items from CIDI. SU = mothers’ alcohol and drug use measured using items from CIDI. Follow-up (2–6 years post-intervention): DVA = mothers’ physical and psychological victimisation and perpetration measured using CTS2. MH and SU = Same as above. |

|

8. Slesnick and Erdem (2013); Guo et al. (2016) (reference number: [82, 120]) |

Columbus, Ohio, U.S. 75% African / African American |

Homeless mothers living in a public or private temporary living shelter/public or private place not designed for regular sleeping who had a biological child aged 2–6 years in their care and met criteria for substance abuse or dependence (DSM-IV) | Family homeless shelter. Exclusion criteria: None stated. |

Treatment | Multi-component ecologically based intervention (n = 30) aiming to reduce mothers’ SU (and related disorders) and promote independent living. Involved three main components: housing support, case management and counselling. In terms of housing support, mothers were provided with their choice of accommodation and given rental/utility assistance for 3 months. In terms of case management, mothers received ongoing assistance with any ongoing needs (including referrals to food pantries, obtaining food stamps etc.). In terms of counselling, mothers received operant-based Community Reinforcement Approach counselling designed to address SU but also other related issues including DVA and MH. This was delivered by white, female masters-level therapists (graduates from The Ohio State University Couple and Family Therapy program or Clinical Social Work program). | Delivered in an undisclosed setting over a period of 6 months. This included 6 months of case management (26 sessions, frequency not stated) and counselling (20 sessions, frequency not stated), and 3 months of concurrent housing support; hosted within housing/community SU. | Active control (n = 30) received emergency shelter accommodation for up to three weeks followed by ‘rapid re-housing’ which involves partner agencies providing independent housing/shelter providing 3 months of subsided housing and encouraging mothers’ to secure employment during this time to take charge of payments. Also received normal services through community. |

Authors describe as uni-directional; homelessness (and having a dependent child) is linked with MH and SU. More frequent SU predicts higher rates of IPV (DVA). Intervention treats as bi-directional; providing Community Reinforcement Approach counselling to tackle all concurrently. |

Post-intervention: DVA = mothers’ emotional abuse victimisation measured using WEB MH = mothers’ depression and general MH measured using BDI-II and SF-36 MH subscale, respectively. SU = mothers’ alcohol and drug use measured using The Form90 Interview and urine toxicology. Follow-up (3 months post-intervention): Same as above. |

|

9. Jack et al. (2019) (reference number: [79]) |

Multiple states, U.S. 50.7% Hispanic / Latina |

First-time mothers (aged 16+) who had met criteria for entering the NFP program (<28 weeks gestation, living in poverty, first-time birth) and had not yet completed 4th NFP nurse visit. Exclusion criteria: None stated. |

Home visiting sites across the U.S. | Secondary / treatment | Home visiting supplement intervention (n = 229) aiming to improve mothers’ quality of life and reduce risk of IPV (and other related issues). Mothers received NFP home visits (as described in control group section) in addition to a multi-component IPV intervention delivered by nurses. Involved extensive nurse training in IPV, and clear guidance around reflective supervision and procedures to implement a multi-component, tailored intervention which involved nurses conducting universal safety assessments and identifying IPV, providing an empathetic response to disclosures, conducting risk assessments and empowerment intervention (including safety planning and discussing cycle of abuse), conducting MH, SU and readiness to address safety assessments. This information was then used to tailor a response providing motivational interviewing, safety planning, education of health effects, goal setting and providing referrals to and facilitating access to external services (e.g., DVA, MH, SU, housing, legal, financial support). | Delivered in the home setting over a period of 2 years+ (pregnancy–child’s 2nd birthday); hosted within established home visiting sites. | Active control (n = 263) received NFP home visits from a nurse over a period of 2 years+ (pregnancy–child’s 2nd birthday, max 64 sessions, frequency not stated). Sessions involved discussing maternal health, environmental health, role as a mother, relationships, life course development and services. IPV was screened for at three separate points in time. If mothers disclosed IPV their safety was assessed, they were provided with information, and referred to community services. | Not stated. Intervention treats as co-occurring; although addressing them all (and recognising DVA may lead to MH and SU) involves empowerment intervention for DVA, and identification and referral for MH and SU tackling them with separate, distinct approaches. |

Post-intervention: DVA = mothers’ physical, emotional, and severe abuse and harassment measured using CAS. MH = mothers’ PTSD, depression, and general MH measured using SPAN, PHQ-9, and SF-12 MH subscale, respectively. SU = mothers’ alcohol and drug use measured using TWEAK and DAST, respectively. No follow-up. |

|

17a. Olds et al. (2004)1 (reference number: [103]) |

Denver, Colorado, U.S. ~46.6% Mexican American (based on those who completed follow-up assessments) |

Low income (at 133% of federal poverty level or had no private insurance) women experiencing their first live birth. Exclusion criteria: None stated. |

Antepartum clinics. | Tertiary / secondary | Home visiting intervention (n = 245) called NFP aiming to improve maternal and foetal health, improve child development, enhance mothers’ development. Mothers received home visits from paraprofessionals with strong people skills and high school education. Visits involved promoting mothers’ health-related behaviours, parenting skills, and planning for the future (family planning, education, and employment), helping mothers improve social relationships, and promoting their use of external services to address needs. | Delivered in home setting over a period of 2 years+ (pregnancy–child’s 2nd birthday, number of sessions and frequency varies); hosted within established home visiting sites. | Minimal care control (n = 255) mothers received free child development screenings and referrals at 6, 12, 15, and 21 months. |

Authors do not state. Intervention treats as co-occurring; separate referrals for DVA/MH/SU. |

DVA/MH/SU not measured at post-intervention. Follow-up (24 months post-intervention): DVA = mothers’ physical violence victimisation measured using CTS. MH = mothers’ general MH not reported how this was measured. SU = mothers’ alcohol and marijuana use measured using own measure. |

|

17b. Olds et al. (2004)1 (reference number: [103]) |

Denver, Colorado, U.S. ~46.6% Mexican American (based on those who completed follow-up assessments) |

Low income (at 133% of federal poverty level or had no private insurance) women experiencing their first live birth. Exclusion criteria: None stated. |

Antepartum clinics. | Tertiary / secondary | Home visiting intervention (n = 235) called NFP aiming to improve maternal and foetal health, improve child development, enhance mothers’ development. Mothers received home visits from nurses. Visits involved promoting mothers’ health-related behaviours, parenting skills, and planning for the future (family planning, education, and employment), helping mothers improve social relationships, and promoting their use of external services to address needs. | Delivered in home setting over a period of 2 years+ (pregnancy–child’s 2nd birthday, number of sessions and frequency varies); hosted within established home visiting sites. | Minimal care control (n = 255) mothers received free child development screenings and referrals at 6, 12, 15, and 21 months. |

Authors do not state. Intervention treats as co-occurring; separate referrals for DVA/MH/SU. |

DVA/MH/SU not measured at post-intervention. Follow-up (24 months post-intervention): DVA = mothers’ physical violence victimisation measured using CTS. MH = mothers’ general MH not reported how this was measured. SU = mothers’ alcohol and marijuana use measured using own measure. |

|

18. Olds et al. (2007; 2010; 2019) Hand linked: Olds et al. (2004) (reference number: [102, 121–123]) |

Memphis, Tennessee, U.S. 92% Black |

Black, low income, pregnant women (<29 weeks gestation) who had two or more of the following risk factors; unmarried, <12 years education, and/or unemployed, and who had no specific chronic illnesses that might impact foetal growth and development. Exclusion criteria: None stated. |

Obstetric clinics. | Tertiary / secondary | Home visiting intervention (n = 228) called NFP aiming to improve pregnancy outcomes, improve child development, enhance mothers’ development. Mothers received home visits from nurses. Visits involved promoting mothers’ health-related behaviours, parenting skills, and planning for the future (family planning, education, and employment), helping mothers improve social relationships, and promoting their use of external services to address needs. Nurses tried to involve other family members/friends in visits where possible. | Delivered in home setting / over telephone over a period of 2 years and 3 months (pregnancy–child’s 2nd birthday, number of sessions and frequency varies); hosted within established home visiting sites. | Minimal care control (n = 515) mothers received free developmental screening and referral for children at 6, 12, 15, and 21 months and free transportation to prenatal care. |

Authors do not state; all linked to increased chance of poor child outcomes / maltreatment. Intervention treats as co-occurring; separate referrals for DVA/MH/SU. |

DVA/MH/SU not measured at post -intervention. Follow-up (16 years post-intervention): DVA = mothers’ physical violence victimisation measured using CTS. MH = mothers’ depression and anxiety measured using BSI and BAI, respectively. SU = mothers’ substance use measured using drug use screening inventory. |

|

19. Ondersma et al. (2017) (reference number: [63]) |

Indiana, U.S. 37.5% Black African American |

Pregnant women (≥18 years, no more than 45 days before expected due date) who were at risk of child maltreatment as defined by high score on Kempe Family Stress Checklist (evaluating presence of DVA, MH, and SU, and related factors). Exclusion criteria: None stated. |

Home visiting sites. | Tertiary / secondary | E-intervention home visiting supplement (n = 142) aiming to reduce child maltreatment risk factors including DVA, MH, and SU in order to reduce harsh parenting and increase intervention adherence. Mothers received an e-intervention in addition to normal home visiting services (see control group description). This was delivered online on a PC tablet (provided by home visitors) and included a narrator, audio (via headphones), interactive elements, and videos. The sessions (20 mins each) focused on providing motivational interviewing to engage mothers in the home visiting intervention and target DVA, MH, and SU, cognitive retraining to model ways to parent when confronted with difficult child behaviours, and SafeCare to discuss home safety, medical decisions, and accident prevention. | Delivered over the internet over a period of 6 months (or until all 8 sessions complete, frequency of sessions varies); hosted within established home visiting sites. | Two control groups2: 1) Active control (n = 141) receiving HFA home visiting program alone. Involved weekly home visits in the first 6 months, vary thereafter depending on family’s level of need (every other week and then monthly/ quarterly). Home visits aimed to promote family functioning, parent-child relationships and child health and development. 2) Minimal care control (n = 130) receiving community referrals. |

Authors do not state; all considered risk factors for child maltreatment. Intervention treats as co-occurring; motivate parents to get help with DVA/MH/SU concurrently using motivational interviewing but support is provided through separate services for DVA, MH, and SU. |

Post-intervention: DVA = mothers’ physical assault and injury victimisation and perpetration measured using CTS2. MH = mothers’ depression measured using EPDS. SU = mothers’ alcohol and drug use measured using ASSIST. Follow-up (6 months post-intervention): Same as above. |

|

22. Rotheram-Borus et al. (2015) Linked: Rotheram-Borus et al. (2014; 2019) Hand linked: Rotheram-Fuller et al. (2018); Le Roux et al. (2013) (reference number: [80, 124–127]) |

Cape Town, South Africa 100% Black African |

Low-income pregnant women (aged 18+) residing in urban areas near Cape Town. Exclusion criteria: None stated. |

Community; low-income urban areas. | Secondary | Home visiting intervention (n = 644) called the ‘Philani+ Programme’ (PHILANI+) aiming to reduce alcohol use and improve HIV related behaviours. Mothers received home visits from paraprofessionals (community health workers; CHW) who had experience raising their own healthy children and had good problem solving and social skills. The sessions involved education around general maternal and child health, HIV/TB, alcohol use, mental health, and nutrition, and dealing with crises. CHW delivered a brief alcohol intervention as part of this which involved discussing the consequences of alcohol use on children and the amount of alcohol currently being used by the mother (compared to recommended quantities). The intervention was guided by CBT principles and involved role play, goal setting, problem solving, relaxation, assertiveness, and shaping. CHW received regular supervision and logged their contacts with mothers on a mobile app. | Delivered in the home setting over a period of 18 months+ (number of sessions varies, frequency varies); hosted within established home visiting sites. | Usual care control (n = 594) involved accessing services situated ≤5km away which provided HIV related testing and medical care as well as postnatal visits at 1 week (although authors describe this as inconsistent). HIV care was also available during four antenatal visits and within HIV care clinics postpartum, during which time well-baby visits were also provided. |

Authors describe as uni-directional; women with depression (MH) are at increased likelihood of alcohol use (SU) which is often implicated in IPV (DVA) and all can have a negative impact on children. HIV impacts relationships with partners, children, MH, and physical health. Intervention treats as uni-directional–SU focused; targeting alcohol use specifically and hoping for decreased MH and DVA. |

Post-intervention: DVA = mothers’ physical violence victimisation measured using questions adapted from Jewkes et al. MH = mothers’ depression measured using EPDS and GHQ-12. SU = mothers’ alcohol use measured using AUDIT-C latent variable. Follow-up (18 months post-intervention): Same as above. |

|

23. Silovsky et al. (2011) (reference number: [68]) |

Rural country in South West, U.S. 71.3% White |

Caregivers (aged 16+) who had at least one child ≤5 years and displayed at least one of the following risk factors for child maltreatment; IPV, MH, or SU. Exclusion criteria: current child welfare or service involvement, two prior child welfare referrals, caregiver perpetrated child sexual abuse, severe psychosis, severe MH or any other issue that might prevent caregiver from providing valid self-report data. |

Various; child maltreatment prevention and parenting services, referrals from professionals and community-based organisations (e.g., schools, faith organisations). | Tertiary | Home visiting supplement (n = 48) called ‘SafeCare+’ aiming to prevent child maltreatment by reducing parent IPV, depression and SU. Parents3 received home visits from home visitors who were supported my IPV MH and SU professionals. The standard SafeCare home visiting programme is underpinned by an eco-behavioural approach targeting different levels of the ecological model of child maltreatment and parenting behaviours related to ‘child health, home safety and cleanliness, and parent-child bonding’ through modelling, practice and feedback, ongoing measurement of behaviours, and parent training. It also involves recognising and responding to factors such as IPV, depression and SU and recognising the role of poverty. The home visiting supplement (leading to SafeCare+) expands on this to provide additional training in identifying and responding to IPV, depression and SU as well as in motivational interviewing with the view that this will encourage parents to address these issues. | Delivered within the home setting over a period of less than 6 months (number of sessions and frequency not stated); hosted within established home visiting services. | Active control (n = 57) received a community MH program which offered individual and family therapy and case management. Support was tailored to families’ needs based on what they wanted to address (e.g., SU, depression, anxiety, anger management). Intervention treats as co-occuring; identifying and responding to IPV, depression and SU as co-occurring risk factors for child maltreatment. |

Authors do not state; all three known risk factors for child maltreatment. |

Post-intervention (treated here as 6 months): DVA = parents’3 physical, psychological, sexual and injury-related victimisation measured using CTS2. MH = parents’3 depression measured using BDI-II. SU = parents’3 alcohol and drug use measured using DIS module. Follow-up (6 months post-intervention): Same as above. |

|

26. Stover et al. (2019) (reference number: [84]) |

Large metropolitan area in South East, U.S. 74% Euro-American heritage |

Fathers (English speaking) in residential SU treatment who were in contact with children and reported physical or psychological IPV towards female co-parent in last 12 months. Exclusion criteria: None stated. |

Residential SU. | Treatment / tertiary | Therapy intervention (n = 33) called ‘Fathers for Change’ (F4C) aiming to reduce SU, IPV, negative parenting and increase positive co-parenting. Fathers (and mother and child where appropriate) received individual therapy sessions delivered by masters-level clinicians with experience in residential SU. Sessions targeted the intersection between DVA, SU and child maltreatment and were based on Substance Abuse Domestic Violence CBT (SADV) and behavioural couples’ therapy. First part focused on encouraging and supporting father in abstinence of SU and DVA using motivational enhancement, discussing child development, own childhood experiences of DVA and SU and how DVA and SU can impact parenting, and developing skills in reflective functioning and emotional regulation to reduce hostility. Second part involved focus on parental communication and problem-solving. Third part involved focus on restorative parenting. | Delivered in residential SU over a period of 12 weeks (12 sessions, weekly) plus 4 booster sessions (frequency not stated); hosted within residential SU. | Active control (n = 29) received ‘Dads n Kids’ (DNK) intervention delivered by masters-level clinicians over a period of 12 weeks (12 sessions, weekly). Involved clinician helping with basic family needs through problem-solving and providing fathers with a choice of leaflets that provided fathers with education on things such as child development, parenting, nutrition, lifestyle etc. and psychoeducation around parenting. |

Authors describe as uni-directional; IPV (DVA) and SU co-occur and can lead to psychosocial problems (MH) which can impact role as father. Intervention treats as bi-directional; providing integrated treatment for DVA and SU in combination. |

Post-intervention (around 16 weeks): DVA = fathers’ psychological, verbal and physical perpetration measured using TLFB-SV. MH = fathers’ general MH measured using BSI GSI. SU = fathers’ general SU measured using TLFB. Follow-up (3 months post-intervention): Same as above but in addition, measure psychological and physical perpetration and victimisation using CTS2. |

|

32. Trevillion et al. (2020) (reference number: [69]) |

South East London, UK 66% White |

Pregnant women (aged 16+, ≤26 weeks gestation) meeting the criteria for major depressive disorder or mixed anxiety and depressive disorder on DSM-IV. Exclusion criteria: Receiving MH support (e.g., CBT, therapy, secondary MH service), unable to provide informed consent/follow, intervention due to language barriers, other current MH disorder including psychosis, eating disorder, BPD, PTSD, or experiencing suicidality. |

NHS maternity units / referrals from related research study. | Treatment | Therapy intervention (n = 26) aiming to reduce depressive symptoms. Mothers received guided self-help sessions delivered by Psychological Wellbeing Practitioners (PWPs) who worked within IAPT. Involved working through a workbook which provided mothers with psychoeducation on antenatal depression, information on relationships and parenthood planning, and health/lifestyle. Also involved regular homework tasks. | Delivered in clinic and/or remotely (telephone) over a period of 6–8 weeks (9 sessions, frequency not stated); hosted within Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme within NHS. | Usual care control (n = 27) (no further details given). |

Authors do not state. Intervention treats as uni-directional–MH focused; targeting depression with the view this may also lead to potential changes in DVA and SU. |

Post-intervention (14 weeks post randomisation): DVA = mothers’ physical, emotional, and harassment-related victimisation measured using CAS. MH = mothers’ depression and anxiety measured using EPDS, PHQ-9, and GAD-7, respectively. SU = mothers’ alcohol use measured using AUDIT-C. Follow-up (3 months post-intervention): Same as above. |

NB. Green coloured cells indicate studies that have had, or report to have, combined positive impacts on two or more outcomes. 1 Olds et al. (2004) conducted a three-arm RCT examining the effectiveness of a home visiting intervention delivered by paraprofessionals (intervention group 1) and a home visiting intervention delivered by nurses (intervention group 2) as compared to a minimal care control group. Therefore, there are two separate entries for this study, one with the paraprofessional delivered intervention as the intervention group and one with the nurse delivered intervention as the intervention group. 2 For outcome data compare intervention to active control as intervention designed to outperform on key outcomes. 3Parents were mostly mothers (only 1 was father). ASI = Addiction Severity Index; ASSIST = Alcohol Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test; AUDIT-C = Alcohol use disorders identification test for consumption; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BPD = Borderline personality disorder; BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory; CAS = Composite Abuse Scale; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CIDI = Composite International Diagnostic Interview; CTS = Conflict Tactics Scale; DAST = Drug Abuse Screening Test; DIS = Diagnostic Inventory Schedule; DVA = Domestic violence; EPDS = Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; GAD-7 = Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7; GHQ = General Health Questionnaire; GSI = Global Severity Index; IPV = Intimate partner violence; MH = Mental ill-health; MHI-5 = Mental Health Index-5; NFP = Nurse Family Partnership; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PTSD = Post traumatic stress disorder; SF- = Short Form-; SU = Substance misuse; TLFB = Timeline Follow Back Interview; TLFB-SV = Timeline Follow Back Interview-Spousal Violence; WEB = Women’s Experience of Battering Scale.

The included studies comprised a mixture of secondary prevention [80, 86], treatment of DVA, MH, or SU [69, 70, 77, 82, 87, 88, 90, 92, 93], and tertiary prevention [68, 78, 83, 85, 91, 97–99, 101, 105, 106] interventions, and many provided support at multiple preventive levels [63–67, 79, 81, 84, 89, 94, 95, 100, 102–104].

The studies varied in terms of the type of intervention delivered which we categorised as follows; home visiting or parenting [67, 80, 94, 97–99, 101–103, 105, 106], home visiting or parenting supplements [63, 68, 78, 79, 97], therapy [65, 69, 70, 77, 84–86, 88–91], multi-component [66, 82, 83, 87, 92], empowerment/advocacy [81, 93, 104], coping skills [64, 95], and brief alcohol interventions [100] (S1 Appendix). Across these intervention types, there were three main approaches to addressing DVA, MH, or SU including approaches which treated these issues as: 1) co-occurring, intervening with DVA, MH, and SU in separate, distinct ways using the same intervention component or separate components, and not addressing the relationship between these issues [63, 64, 67, 68, 78, 79, 85, 91, 92, 94, 95, 97–99, 102, 103, 106]; 2) uni-directional, intervening by focusing on one main issue (either DVA [89, 97], MH [69, 88], or SU [77, 80, 83, 87, 90, 100] and hypothesising that this will lead changes in the others or by targeting the relationship between issues in one direction; or 3) bi-directional, intervening concurrently using the same intervention component and addressing the relationships between two or more of DVA, MH, and/or SU [65, 66, 70, 81, 82, 84, 86, 93, 104].

Studies varied in the combination of outcomes measured with eight measuring DVA and MH [70, 78, 81, 86, 92, 93, 97, 104], four measuring DVA and SU [65, 83, 98, 99], 13 measuring MH and SU [64, 66, 67, 77, 85, 87–91, 94, 95, 100], and 12 measuring all three outcomes [63, 68, 69, 79, 80, 82, 84, 101–103, 105, 106]. Outcomes were measured post-intervention [63–70, 77–94, 97–101, 104–106] or follow-up ranging from 6 weeks to 16 years post-intervention [63, 64, 66–69, 80, 82–86, 88, 90, 91, 95, 102–106].

Risk of bias

Table 5 reports quality appraisal, further details of which can be found in S1 Appendix. The overall risk of bias judgement for the majority of studies was either ‘some concerns’ or ‘high risk’ of bias. Common issues included the use of self-report measures for DVA, MH, and SU, which may be prone to bias given that participants were often aware of their group allocation (as this is unavoidable for RCTs of psychosocial interventions), and lack of a publicly available, pre-specified data-analysis plan, making it difficult to assess whether data analysis had been conducted as intended. Several studies also failed to account for missing outcome data or provided limited information on how this was completed (n = 19). Other issues included limited information on, or problems with, the randomisation process (n = 10), failure to use valid and reliable measures (particularly for SU outcomes for which many authors relied on single self-report questions over validated measures) (n = 9), baseline differences between groups that may indicate bias in the randomisation process (n = 8), deviations from intended group assignments due to trial context (n = 4), inappropriate analysis to examine effect of assignment to intervention (n = 2), and bias in selection of reported results (n = 1).

Table 5. Quality appraisal results of included studies using RoB2.

| Study number and author | 1. Randomisation process | 1b. Identification and recruitment of participants cluster RCTs | 2. Effect of assignment to intervention | 3.Missing outcome data | 4. Measurement of outcome | 5. Selection of reported result | Overall risk of bias judgement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cupples et al. | L | N/A | L | H | SC | SC | H |

| 2. Duggan et al. | L | N/A | L | H | H | SC | H |

| 3. Duggan et al. | SC | N/A | L | SC | H | SC | H |

| 4. El-Mohandes et al. | L | N/A | L | L | SC | SC | SC |

| 5. Fergusson et al. | L | N/A | L | L | H | SC | H |

| 6. Fleming et al. | L | N/A | L | SC | L | SC | SC |

| 7. Grigg | L | N/A | SC | H | SC | SC | H |

| 8. Slesnick et al. | L | N/A | SC | L | SC | SC | SC |

| 9. Jack et al. | SC | L | L | SC | SC | SC | SC |

| 10. Jacobs et al. | L | N/A | L | SC | SC | SC | SC |

| 11. Jones et al. | SC | N/A | SC | L | SC | SC | SC |

| 12. Lam et al. | SC | N/A | L | L | SC | SC | SC |

| 13. Lecroy et al. | H | N/A | SC | SC | H | SC | H |

| 14. Luthar et al. | SC | N/A | L | H | SC | SC | H |

| 15. McWhirter | SC | N/A | L | L | H | SC | H |

| 16. Nagle | L | N/A | L | SC | SC | SC | SC |

| 17. Olds et al. | L | N/A | L | SC | H | SC | H |

| 18. Olds et al. | L | N/A | L | L | H | SC | H |

| 19. Ondersma et al. | L | N/A | L | L | SC | SC | SC |

| 20. Rotheram-Borus | SC | N/A | L | SC | H | SC | H |

| 21. Rotheram-Borus | SC | N/A | L | L | H | SC | H |

| 22. Rotheram-Borus | L | SC | L | SC | H | SC | H |

| 23. Silovsky et al. | L | N/A | H | L | SC | SC | H |

| 24. Wu and Slesnick | SC | N/A | L | L | SC | SC | SC |

| 25. Stover | L | N/A | H | H | SC | H | H |

| 26. Stover et al. | L | N/A | H | L | SC | SC | H |

| 27. Suchman et al. | SC | N/A | L | L | L | SC | SC |

| 28. Suchman et al. | SC | N/A | L | L | SC | SC | SC |

| 29. Sullivan et al. | SC | N/A | L | SC | H | SC | H |

| 30. Taft et al. | H | H | L | L | SC | L | H |

| 31. Tiwari et al. | L | N/A | L | L | SC | SC | SC |

| 32. Trevillion et al. | L | N/A | L | L | SC | L | L |

| 33. Volpicelli et al. | SC | N/A | L | SC | SC | SC | H |

| 34. Walkup et al. | L | N/A | SC | H | H | SC | H |

| 35. Zlotnick et al. | SC | N/A | L | L | SC | SC | SC |

| 36. Dinmohammadi et al. | L | N/A | H | H | SC | H | H |

| 37. Skar et al. | L | N/A | H | L | SC | SC | H |

NB. L = Low risk of bias; SC = Some concerns; H = High risk of bias.

Data synthesis

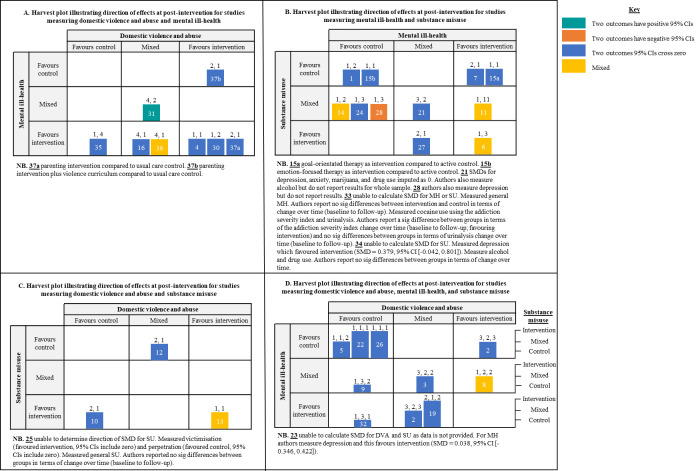

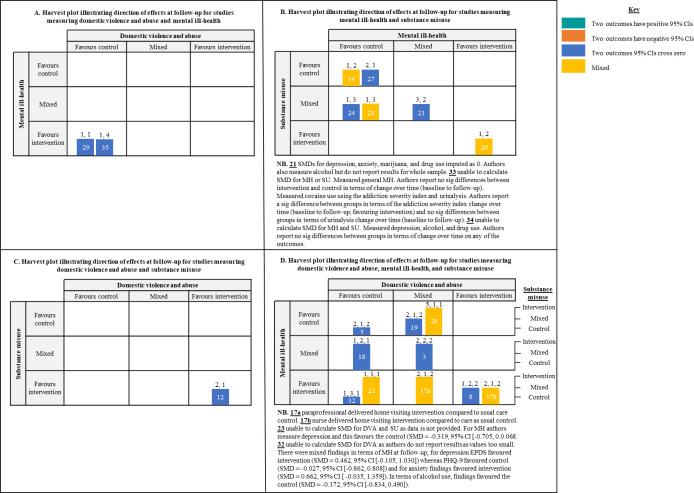

Findings are presented and synthesised under four main headings corresponding to the combination of outcomes that studies measured: 1) DVA and MH; 2) DVA and SU; 3) MH and SU; and 4) DVA, MH, and SU. Figs 2 and 3 summarise the direction of effects for DVA, MH, and SU outcomes within each of the 37 studies using calculated SMDs and 95% CIs. Where we have been unable to calculate SMDs and 95% CIs, findings are reported narratively. Tables containing all SMDs and 95% CIs and harvest plots illustrating the direction of effect for sub-categories of DVA, MH, and SU can be found in S1 Appendix.

Fig 2. Direction of effects for combinations of DVA, MH, and SU outcomes at post-intervention.

Harvest plots A, B, and C: Bars represent studies; Placement of bars represents direction of effect for DVA, MH, and/or SU outcomes; Numbers above bars represent number of outcome measures the categorisation is based on displayed in the following order where applicable: DVA, MH, SU; Number in bars represent the study number; Colour represents whether any of the SMDs 95% confidence intervals are positive, cross 0, or are negative (see key). Harvest plot D is same as previous but with the following addition: Height of the bar represents direction of effect for SU.

Fig 3. Direction of effects for combinations of DVA, MH, and SU outcomes at follow-up.

Harvest plots A, B, and C: Bars represent studies; Placement of bars represents direction of effect for DVA, MH, and/or SU outcomes; Numbers above bars represent number of outcome measures the categorisation is based on displayed in the following order where applicable: DVA, MH, SU; Number in bars represent the study number; Colour represents whether any of the SMDs 95% confidence intervals are positive, cross 0, or are negative (see key). Harvest plot D is same as previous but with the following addition: Height of the bar represents direction of effect for SU.

Domestic violence and abuse and mental ill-health