Introduction

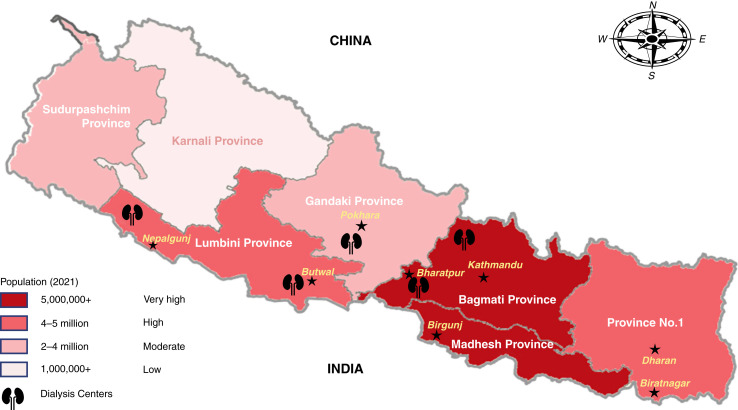

Nepal, a newly proclaimed Federal Democratic Republic, is a landlocked country situated between India and China in South Asia (Figure 1) (1). Popularly known as the home of Mt. Everest and birthplace of Gautam Buddha, Nepal has an area of 147,516 km2. The population of Nepal is estimated to be 29.49 million as of March 9, 2021 (2). Nepal’s gross domestic product per capita was US$1155.1, and the health expenditure as a percentage of gross domestic product was 5.84 as per 2018 data (3). The average life expectancy of a Nepalese is 71 years. As of June 29, 2020, there were 23,146 medical doctors and 7185 specialist physicians in Nepal. The doctor/population ratio of Nepal is 1:1721, and the nurse/population ratio is 1:500. There were 56 nephrologists registered in the Nepal Society of Nephrology in 2021. The majority of them (44 out of 56) practice in the capital city, Kathmandu. Hospitals that provide advanced medical care are mainly located in the major cities of Kathmandu, Pokhara, Bharatpur, Dharan, Butwal, Biratnagar, Birgunj, and Nepalgunj.

Figure 1.

Map of Nepal (1).

Health Care Model and Economics of Health Care

Health care delivery in Nepal is composed of a mixed model of public sector, private sector, and nongovernment organizations. Health care policy is developed and stipulated by the Ministry of Health at the national level. The major source of health care financing is out-of-pocket spending. Consultation fee and basic diagnostic investigation costs are relatively inexpensive in public hospitals. There is a governmental provision for free essential drugs, but patients are responsible for paying for the cost of drugs not included on the essential drug list.

Nepal’s legislative parliament endorsed the National Health Insurance (NHI) bill on October 10, 2017. The governing body for this is the NHI Board, which aims to achieve universal health coverage by 2030 (4). This is considered a welcomed, although ambitious, commitment from the government.

Patients are charged a nominal fee for health care costs in government hospitals. These attract a massive volume of patients. According to the NHI bill, an insured patient would pay a premium of US$29 per year for a family of five to receive a health care reimbursement worth up to US$840. In the case of impoverished patients, the premium payment is waived by the government. The government of Nepal provides subsidy under the Disadvantaged Citizens Medical Treatment Fund to any citizen who is unable to bear their health care costs if they carry a diagnosis of any of eight eligible chronic illnesses: cardiovascular diseases, cancer, renal failure, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, head and spinal cord injury, sickle cell anemia, and stroke. In order to receive health care services and treatment for these chronic illnesses, patients must obtain appropriate medical documentation from their local government health officials. Care and treatment can be obtained only at health care facilities and hospitals officially recognized and enlisted by the government. Wealthier individuals often forgo government-sponsored health care and seek care from the private sector. In fact, private sector health care comprises more than two thirds of the total hospital bed capacity in Nepal, and 60% of the physician workforce rely on income received by providing services in the private sector. Many physicians who are primarily employed in public hospitals also work after hours in private hospitals and dialysis centers. Consequently, many physicians are overworked due to this “dual practice.”

In 2011, the Department of Health Services, under the Ministry of Health and Population, began providing financial support to patients diagnosed with CKD; US$97 was provided annually for hemodialysis (HD). This was increased to US$483 in 2012. With the start of this financial support, Nepal has seen a rapid increase in dialysis services by government hospitals, medical colleges, private hospitals, and nongovernment organizations. From 2010 to 2016, there was a 223% increase in the number of HD centers, bringing the total number of HD centers in the country to 42 in 2016 (5). Free HD was started in 2014, with twice weekly treatments provided for 1 year. This was increased to a twice weekly service for 2 years in 2015. Financial support was extended to include kidney transplantation in the same year, with US$1931 provided for surgery and US$966 provided for post-transplant medication and medical care. Currently, the government of Nepal provides a total of NPR 550,000 (around US$4580) and also provides NPR 5000 (around US$40) per month to kidney transplant recipients to bear the expense of medication. In 2016, the Ministry of Health started free lifetime HD in Nepal (5). HD is free in the public hospitals. It is also free in selected private hospitals and dialysis centers who have signed agreements with the Ministry of Health. The cost of free dialysis in those private hospitals and dialysis centers is reimbursed by the government. As of March 2021, there were 60 HD centers, 570 HD machines, and approximately 3775 patients receiving HD (5,6). The government also provides 90 bags of free dialysate per month for continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD).

Epidemiology of CKD in Nepal

CKD is a major public health problem worldwide, with a significant burden of morbidity and mortality. It is now recognized as a major public health problem in Nepal (7). It was the 10th leading cause of death in Nepal in 2019.

The celebration of World Kidney Day on the second Thursday of March every year in different parts of Nepal has increased awareness of the public and media on CKD, leading to screening of more people who are symptomatic and at risk. This has also increased the pickup of CKD cases. Furthermore, there has been increasing awareness of health and kidney disease in the eastern part of Nepal made possible by a community screening program led by Dr. Sanjib Kumar Sharma. Whether mass screening for CKD is beneficial and cost-effective in Nepal needs more study before final recommendations can be made. Screening on the basis of eGFR determined from serum creatinine and urine protein quantification from the albumin/creatinine ratio in high-risk individuals would likely be more practical.

In urban areas of Nepal, the estimated prevalence of CKD is 11% (8). A study performed in 12 low- and middle-income countries by the International Society of Nephrology’s Kidney Disease Data Center reported an approximately 20% prevalence of CKD in the cohorts from Nepal (9). According to the hospital-based data for CKD, the mean patient age was 50.92 years, the ratio of men to women was 1.8:1, and 51% were active smokers (8). Chronic interstitial nephritis has been implicated with the use of some popular Ayurvedic and herbal medicinal agents. However, there are no data for the incidence of chronic interstitial nephritis related to Ayurvedic or herbal medicines in Nepal apart from anecdotal evidence.

Epidemiology of ESKD in Nepal

From a tertiary hospital-based study from Chitwan, Nepal, the prevalence of new ESKD is 11.36% (10). The estimated incidence of ESKD in Nepal is around 100 per million per year and may even be higher on the basis of the incidence rates reported in other developing nations, including India (11). There are some hospital-based data for ESKD, but there is no formal renal registry. The absence of a national renal registry likely accounts for the lower reported incidence compared with the global average. Furthermore, a substantial number of impoverished patients in need of HD go without treatment, despite HD being free of charge. This may be due to other indirect costs that patients have to bear, including transportation, food, lost wages, cost of diagnostic investigations, or medicines. The most frequent causes of ESKD in Nepal, derived from different hospital-based studies, are listed in Table 1 (8,10,12). The attributed etiologies of ESKD may be erroneous at times because the diagnosis of chronic glomerulonephritis is presumed most of the time, and hypertension may be the consequence of CKD. Similar to worldwide prevalence, diabetes mellitus is becoming the leading cause of ESKD in Nepal due to its rising prevalence. The high prevalence of chronic glomerulonephritis is striking in Nepal and similar to other developing nations; this is thought to be a sequela of untreated acute glomerulonephritis, probably a higher prevalence of IgA nephropathy, and a comparatively high prevalence of repeated untreated infections.

Table 1.

| Causes of ESKD | Prevalence (2021) | Prevalence (2018) | Prevalence (2009) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitus | 35.6% | 31.9% | 24% |

| Chronic glomerulonephritis | 34.4% | 36.2% | 15% |

| Hypertension | 24% | 21.7% | 55% |

| Others | 6% | 10.2% | 6% |

Dialysis Access

Studies pertaining to types of vascular access in ESKD patients in Nepal are scarce. There are a few small institution-based studies. The most common vascular access utilized to initiate HD in ESKD patients has been noncuffed vascular catheters. In the incident HD patients, 55% have a nontunneled cuffed catheter (non-TCC), 42% have an arteriovenous fistula (AVF), and 3% have a TCC. The proportions in the prevalent HD patients are 90% for AVF, 8% for non-TCC, and 1% for TCC. The use of an arteriovenous graft is <1% (13). With the advancements in the field of interventional nephrology in recent years, there has been an increasing trend of AVF placement performed by both vascular surgeons and nephrologists, with the goal of reducing the overall number of vascular catheters. In a cross-sectional study performed in a teaching hospital in Biratnagar, Nepal, the functional outcome of the AVFs placed by a nephrologist had similar success rates as reported in the literature, i.e., 76% for radiocephalic, 91% for brachiocephalic, and 100% for brachiobasilic arteriovenous fistulas at 3 months post creation (14). There are very few vascular surgeons outside of the capital, Kathmandu. Therefore, if more nephrologists are trained in this surgical skill, this could help to reduce the existing backlog of elective AVF creation. This would also increase the number of pre-emptive AVF placements, reduce the complications related to dialysis catheters, and ultimately may confer improved survival benefit. There are relatively fewer reported problems with vascular access in the Nepalese ESKD population due to the higher proportion of relatively young patients with ESKD and a greater number of nondiabetic ESKD patients. As the survival of ESKD patients on maintenance HD increases, complications related to vascular access are expected to increase.

Renal Replacement Therapy (RRT)

HD

The history of dialysis in Nepal dates back to 1973, with the initiation of intermittent peritoneal dialysis (PD) (Table 2). A HD service was initiated in the country in 1987 in Bir Hospital with two functioning HD machines. Nine years later, in 1996, a HD service was started at Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital (TUTH). This was followed by the establishment of many dialysis centers by private hospitals and Health Care Foundation, Nepal (6,15). In Nepal, most patients undergo twice weekly maintenance HD, each session lasting 4 hours. Government authorities do regular inspections for water quality, infection prevention measures, number of times dialyzers are reused, etc., but clearance adequacy of HD is not routinely evaluated by measuring the Kt/V. Dialysis patients are not typically seen by a doctor during their HD sessions unless there is a call from a dialysis nurse relating to a complication. Most HD centers use a deionization and reverse-osmosis water treatment system. Home HD has not yet been initiated in Nepal; however, there may be opportunity to develop this modality in the future.

Table 2.

| Number of nephrologists registered with Nepal Society of Nephrologists | 56 |

| Incidence of ESKD | 100/million/year |

| Number of centers licensed for renal transplant service | 9 (3 government and 6 private centers) |

| Total number of renal transplants performed in the country from August 8, 2008, through August 20, 2021 | Approximately 1500 |

| Total number of HD centers in the country | 60 |

| Total number of HD machines in the country | 570 |

| Average cost of renal transplant | $3450 |

| Average cost of HD in public sector | Free of cost |

| Average direct cost of HD in private sectora | Approximately $208/month |

| Total number of patients on hemodialysis | Approximately 3775 |

| Total number of patients on PD | >100 to <500 |

| Total “Doctorate of Medicine”/fellowship in nephrology slots available each year | 8b |

| Major historical landmarks | |

| Initiation of intermittent PD in Nepal | 1973 |

| Initiation of HD in Nepal | 1987 |

| HD was made free of charge | 2016 |

| Living related renal transplant legalized | 1998 |

| First successful kidney transplant (at Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital) | 2008 (August 8) |

| Paired exchange provision legalized | 2016 |

| First deceased donor kidney transplant | 2017 (May 10) |

| First ABO incompatible kidney transplant | 2017 (March 22) |

HD, hemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis.

Cost of hemodialysis is reimbursed by government to the accredited hospitals (public, private, and university hospitals) that are periodically inspected by government for quality assurance.

Subject to change on the basis of inspection by Medical Education Commission, government of Nepal.

PD

Acute PD used to be performed in Bir Hospital and TUTH. However, both of these institutions have discontinued acute PD due to the increased availability of emergency HD and intensive care unit dialysis. According to a study in the eastern part of Nepal, the most common indications for the initiation of acute PD in AKI were acute gastroenteritis (20%), sepsis (20%), and septic abortion (16%). For ESKD, the indications were metabolic acidosis (56%), uremic encephalopathy (45%), and fluid overload (44%) (16). Intensive care units without the availability of continuous RRT or sustained low efficiency dialysis continue to utilize acute PD. With regard to chronic PD, CAPD is the only PD being practiced in Nepal. There were only around 100 patients on CAPD until 2016 (6). This had increased to a few hundred by 2021.

Kidney Transplant

Living donor kidney transplant was legalized in Nepal in 1998. In order to prevent organ trade, living donor transplantation is restricted to close relatives by Nepali law. The Human Organ Transplantation Act of 1998 limited the potential kidney donation from a relative only to immediate family members. The 1998 law was subsequently amended in 2016 by the Parliament of Nepal, which paved the way for kidney paired donation and deceased donor kidney transplantation.

The first successful kidney transplant was performed in Nepal at TUTH, Kathmandu, on August 8, 2008, by a team of Nepali and Australian transplant surgeons (Prof. Dr. David Francis, Prof. Dr. Bhola Raj Joshi, and others) and Australia-trained Nepali nephrologist, Dr. Dibya Singh Shah. Bir Hospital in Kathmandu subsequently started this service in December 2008 (17). Currently, three government and six private kidney transplant programs have been licensed, although not all of them are regularly performing transplants. The total number of kidney transplants in Nepal is around 1500. As of March 2021, a total of 644 live donor kidney transplants have been performed in TUTH. The first deceased donor kidney transplant was done in Nepal on May 10, 2017 (18). As of August 20, 2021, the Human Organ Transplant Center (Sahid Dharmabhakta National Transplant Center) has also performed 759 kidney transplants, including six deceased donor kidney transplants. The other remaining kidney transplants were in the following hospitals: 80 in Grande hospital, nine in Sumeru hospital, and three in Nidan hospital. Gender imbalance in regard to living kidney donation in South Asia is not surprising. Nepal, like neighboring India, has an extreme gender imbalance, with 75% of the donors being women and 84% of the recipients being men (19). This gender bias is due to a multitude of factors that are deeply rooted in Nepalese society. For example, the livelihood and well-being of a woman is dependent on her husband. Whether women are coerced or pressured into their decision to donate a kidney is not always apparent through physician interrogation, even though it may in fact be the case.

Challenges/Barriers

There is lot of scope for improving Nepal’s health care delivery system. Public hospitals have significant delays in planned care. The public sector’s existing health care capacity is low. There is often a long waiting list for surgeries, negatively affecting outcomes and satisfaction. Additionally, Nepal has a relatively small number of subspecialty physicians, including nephropathologists. Diagnostic pathology facilities and dedicated centers are either scarce or unavailable. For example, currently renal biopsy specimens still need to be sent to India for electron microscopy; immunofluorescence for renal biopsy has been available only recently within the country.

Efforts to improve the delivery of HD are needed. The practice of regular inspection of water quality and purity for HD needs to become mandatory policy to improve safety. Assessment and reporting of dialysis clearance adequacy (Kt/V) should be made mandatory to improve HD quality. Physician rounds during HD sessions should be reinforced.

PD solutions are not manufactured locally; they are imported from abroad. Due to Nepal’s challenging geography, a great deal of effort, resources, and time is required for transport of dialysate fluid to remote areas of the Nepal. In addition, there are other challenges, including the lack of availability of properly trained personnel for PD teaching, which contributes to increased risk of infectious complications. Another challenge is a general lack of adequate exposure to and training in PD for physicians and nurses during their nephrology training. Moreover, increased advocacy for PD at the national level is essential to expand this modality.

Complement-dependent cytotoxicity crossmatch has recently been initiated in Nepal but is only available during standard business office hours. This necessitates that kidney transplants are performed only during the day. Efforts are underway to make this service available 24/7 that would allow for more opportunities for transplantation at night, especially deceased donor kidney transplantation. The absence of an ESKD registry is a significant challenge for Nepal’s kidney transplant programs. A standardized protocol for organ sharing should also be developed.

Future of Kidney Health in Nepal

Providing easily accessible care to kidney patients in Nepal is challenging due to limited resources, the relatively low number of nephrologists in the country, and the challenging geography of the country. Interventions at the primary and secondary prevention levels would help to slow the rising tide of the ESKD epidemic and help to allocate these scarce resources to those most in need. The following are some potential changes that could be implemented to improve kidney health in Nepal:

-

1.

Development of a screening program for early detection and proper diagnosis of CKD patients is of utmost importance. Screening of the high-risk population by serum creatinine based eGFR and urine albumin/creatinine ratio could be performed to start with. The CKD support program (through “Bipanna Nagarik Sahayata Kosh”) of the government of Nepal should focus on the preventive aspect and early identification of disease.

-

2.

To address the shortage of human resources, more “Doctorate of Medicine” in nephrology or fellowship training positions should be made available for aspiring candidates. More nurses should be trained in HD and PD.

-

3.

There is dissatisfaction among physicians and nurses on account of poor remuneration. This leads to many of them migrating abroad for better jobs and pay. The government and private sectors should devise appropriate methods to address this issue of “brain drain.”

-

4.

The existing kidney transplant program should be improved, and new centers for kidney transplant services should be enabled.

-

5.

Because there is a paucity of data regarding kidney diseases, a national registry of CKD, ESKD, and other kidney diseases should be started by the government.

-

6.

A renal pathology program for immunofluorescence and electron microscopy examination services of kidney biopsy samples should be developed and consolidated in Nepal.

-

7.

PD has been underutilized. Incentive-based training of not only nephrologists but also internists and general practitioners for PD could be helpful in expanding this service.

-

8.

Continuing financial grants for immunosuppressive drugs from the government could help with adherence to post-transplant medications.

-

9.

Ensuring job opportunities for renal transplant recipients could encourage more patients to opt for kidney transplant because they would be able to work full time and not need to hold out for jobs that accommodate their dialysis schedule.

-

10.

Establishment of better record keeping and a registry system could also support kidney paired donation programs for kidney transplant.

-

11.

In-center tissue crossmatch facilities in different transplant centers should be established, and deceased donor kidney transplant programs in the country should be promoted and supported.

-

12.

The deceased donor kidney transplant program in the country should be strengthened.

International donors and institutions already working or interested in working for the betterment of kidney health in Nepal can make significant contributions by helping the government of Nepal and private sectors in establishing a national CKD and ESKD registry and providing technical expertise and logistic support. They can help by providing expert training, assistance with establishment of services, and reduced-price immunosuppressive medications. Policy making should be solely made by the government alone so that the agenda is not driven by external donors and institutions.

Disclosures

All authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. James K. Farry, Program Director of nephrology fellowship, University at Buffalo, Jacobs School of Medicine, and Biomedical Sciences for proofreading the manuscript. We would also like to thank Dr. Shailendra Shrestha, Consultant Nephrologist at Nobel Medical College and Teaching Hospital, Nepal, and Dr. Bikash Khatri, Consultant Nephrologist at National Academy of Medical Sciences, Bir Hospital, Nepal, for providing us with helpful information and constructive feedback. Our sincere thanks to Bidur Sharma Gautam and Anup Kattel, Sydney, Australia, for their contribution in helping with the map of Nepal.

The content of this article reflects the personal experience and views of the authors and should not be considered medical advice or recommendation. The content does not reflect the views or opinions of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) or Kidney360. Responsibility for the information and views expressed herein lies entirely with the authors.

Author Contributions

M. Bhattarai and I. Sharma were responsible for conceptualization; I. Sharma was responsible for the investigation and wrote the original draft of the manuscript; M.R. Sigdel was responsible for supervision; and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Wikipedia : List of Nepalese Provinces by Population. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Nepalese_provinces_by_population. Accessed February 18, 2022

- 2.United Nations Population Fund : Population Situation Analysis of Nepal (with Respect to Sustainable Development). Available at: https://nepal.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/NepalPopulationSituationAnalysis.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2022

- 3.The World Bank : GDP per Capita—Nepal. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=NP. Accessed February 10, 2022

- 4.Pokharel R, Silwal PR: Social health insurance in Nepal: A health system departure toward the universal health coverage. Int J Health Plann Manage 33: 573–580, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mcgee J, Pandey B, Maskey A, Frazer T, Mackinney T: Free dialysis in Nepal: Logistical challenges explored. Hemodial Int 22: 283–289, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abraham G, Varughese S, Thandavan T, Iyengar A, Fernando E, Naqvi SAJ, Sheriff R, Ur-Rashid H, Gopalakrishnan N, Kafle RK: Chronic kidney disease hotspots in developing countries in South Asia. Clin Kidney J 9: 135–141, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma SK, Dhakal S, Thapa L, Ghimire A, Tamrakar R, Chaudhary S, Deo R, Manandhar D, Perico N, Perna A, Remuzzi G, Lamsal M: Community-based screening for chronic kidney disease, hypertension and diabetes in Dharan. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc 52: 205–212, 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sigdel MR, Pradhan R: Chronic kidney disease in a tertiary care hospital in Nepal. J Inst Med 40: 104–111, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ene-Iordache B, Perico N, Bikbov B, Carminati S, Remuzzi A, Perna A, Islam N, Bravo RF, Aleckovic-Halilovic M, Zou H, Zhang L, Gouda Z, Tchokhonelidze I, Abraham G, Mahdavi-Mazdeh M, Gallieni M, Codreanu I, Togtokh A, Sharma SK, Koirala P, Uprety S, Ulasi I, Remuzzi G: Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk in six regions of the world (ISN-KDDC): A cross-sectional study. Lancet Glob Health 4: e307–e319, 2016. 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)00071-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghimire M, Vaidya S, Upadhyay HP: Prevalence of newly diagnosed end-stage renal disease patients in a tertiary hospital of central Nepal, Chitwan: A descriptive cross-sectional study. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc 59: 61–64, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah DS, Shrestha S, Kafle MP: Renal transplantation in Nepal: Beginning of a new era! Nephrology (Carlton) 18: 369–375, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chhetri PK, Manandhar DN, Tiwari R, Lamichhane S: In-center hemodialysis for end stage kidney disease at Nepal Medical College and Teaching Hospital. Nepal Med Coll J 11: 61–63, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramachandran R, Bhargava V, Jasuja S, Gallieni M, Jha V, Sahay M, Alexender S, Mostafi M, Pisharam JK, Tang SCW, Jacob C, Gunawan A, Leong GB, Thwin KT, Agrawal RK, Vareesangthip K, Tanchanco R, Choong L, Herath C, Lin CC, Cuong NT, Akhtar SF, Alsahow A, Rana DS, Kher V, Rajapurkar MM, Jeyaseelan L, Puri S, Sagar G, Bahl A, Verma S, Sethi A, Vachharajani T: Interventional nephrology and vascular access practice: A perspective from South and Southeast Asia [published online ahead of print May 3, 2021]. J Vasc Access 10.1177/11297298211011375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shrestha S, Soni SS, Vachharajani TJ: Functional outcomes of arteriovenous fistulas created by nephrologist. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 18: 155–159, 2020 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hada R: End stage renal disease and renal replacement therapy—Challenges and future prospective in Nepal. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc 48: 344–348, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma SK, Manandhar D, Singh J, Chauhan HS, Koirala B, Gautam M, Ghotekar LRH, Tamang B, Gurung S: Acute peritoneal dialysis in Eastern Nepal. Perit Dial Int 23: 196–199, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chalise PR, Shah DS, Sharma UK, Gyawali PR, Shrestha GK, Joshi BR, Kafle MP, Sigdel M, Raut KB, Francis DMA: Renal transplantation in Nepal: The first year’s experience. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transplant 21: 559–564, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paneru P, Uprety S, Budhathoki SS, Yadav BK, Bhandari SL: Willingness to become deceased organ donors among post-graduate students in selected colleges in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Int J Transl Med Res Public Health 3: 47–58, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Craig SR: “Not found in Tibetan society”: Culture, childbirth, and a politics of life on the roof the world. Himalaya 30: 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirachan P, Kharel T, Shah DS, Ball J: Renal replacement therapy in Nepal. Hemodial Int 14: 383–386, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nepali R, Shah DS: Experience of starting ABO incompatible renal transplant in Nepal. Transplant Rep 4: 100026, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thapa N, Sharma B, Jnawali K: Expenditure for hemodialysis: A study among patient attending at hospitals of Pokhara metropolitan city, Nepal. J Health Allied Sci 9: 46–50, 2019 [Google Scholar]