Abstract

Spodoptera frugiperda is a highly polyphagous pest worldwide with a wide host range that causes serious losses to many economically important crops. Recently, insect-microbe associations have become a hot spot in current entomology research, and the midgut microbiome of S. frugiperda has been investigated, while the effects of cruciferous vegetables remain unknown. In this study, the growth of S. frugiperda larvae fed on an artificial diet, Brassica campestris and Brassica oleracea for 7 days was analyzed. Besides, the microbial community and functional prediction analyses of the larval midguts of S. frugiperda fed with different diets were performed by high-throughput sequencing. Our results showed that B. oleracea inhibited the growth of S. frugiperda larvae. The larval midgut microbial community composition and structure were significantly affected by different diets. Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) suggested 20 bacterial genera and 2 fungal genera contributed to different gut microbial community structures. The functional classification of the midgut microbiome analyzed by PICRUSt and FUNGuild showed that the most COG function categories of midgut bacterial function were changed by B. oleracea, while the guilds of fungal function were altered by B. campestris significantly. These results showed that the diversity and structure of the S. frugiperda midgut microbial community were affected by cruciferous vegetable feeding. Our study provided a preliminary understanding of the role of midgut microbes in S. frugiperda larvae in response to cruciferous vegetables.

Subject terms: Ecology, Microbiology, Molecular biology, Zoology

Introduction

Microorganisms are an important part of insects and are colonized on the exoskeleton, in the gut, hemocoel and other tissues1. During the long-term evolutionary process, the interdependent symbiotic relationship between insects and microorganisms has been formed2,3. In this relationship, insects provide a relatively stable environment and essential nutrition for the microorganisms, while the microorganisms return benefits to the insects in different forms4. For example, microorganisms digest the foods ingested by insect hosts and produce the nutrients, including amino acids, vitamins, and nitrogen, for the host’s absorption5,6. Some of them protect their insect hosts against various adverse threats, such as pathogen infection and parasitic wasp infestation7–9. Increasing reports have evidenced that symbiotic microorganisms also play important roles in the detoxification and metabolism of plant allelochemicals and xenobiotics, such as insecticides and so on10,11. Recently, the contribution of symbiotic microorganisms to the reproduction, growth, and waste conversion of the primary insects reared as food and feed, such as black soldier flies, Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae), mealworms, Tenebrio molitor (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae), and crickets, Acheta domesticus (Orthoptera: Grylloidea), has also received widespread attention12.

Insect gut microbiota attract widespread concern because of their role in contributing to host life-traits13. A variety of factors, including host phylogeny, environment, and diet, may influence the gut microbial community and structure4. Diet is the most important factor that can rapidly and significantly alter the relationship between the insect host and gut microbiota, as well as have short- and long-term effects on the gut microbial community, taxonomic, and functional associations, demonstrating gut microbiota plasticity14,15. Plasticity is apparent in polyphagous insect herbivores. Herbivorous insects have evolved multiple strategies to adapt and degrade to the unfavorable compounds in different hosts, such as the association with symbiont microbiota, which could be useful for exploiting new food sources4,16.

The fall armyworm (FAW), Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith), is the most economically important agricultural pest native to tropical and subtropical regions of the Americas17. FAW has become a worldwide pest and has been introduced into Africa, Asia, and Oceania in the past few years18,19. The larvae are highly polyphagous with a wide host range and could feed on more than 353 plant species20. Maize, wheat, rice, sorghum, cotton, and other economically important crops were damaged by the larvae, causing great economic losses and threatening food security worldwide20. With advances in high-throughput sequencing technologies, studies of the gut microbiome of S. frugiperda associated with different plant hosts have increased in recent years. For example, the effects of soybean and maize on S. frugiperda larval midgut bacterial communities have been analyzed, and a more diverse bacterial community was observed when the larvae feed on soybean21. The influences of different genotypes of maize (Zea mays), including B73, Tx601, and Mp708, on S. frugiperda larval midgut community structure and composition were also explored22. Significant differences in gut microbial community structure and diversity were exhibited when the larvae fed on different hosts23,24. These studies could contribute to the research of the host adaptation of S. frugiperda and the development of efficient and environmentally friendly control strategies.

In general, highly polyphagous lepidopteran species have a partially overlapping host range14. Brassica vegetables are the host plants for the common cutworm, Spodoptera litura, a relative of S. frugiperda25,26. Recently, the biology and biometric characteristics of S. frugiperda reared on Brassica oleracea var. botrytis (cauliflower) were investigated27. Therefore, we speculate that Brassica plants may also be the hosts of S. frugiperda. To further learn more about the relationships among S. frugiperda, Brassica plants and microbes, two cruciferous vegetables, including pakchoi (Brassica campestris L.) and purple cabbage (Brassica oleracea L.), which are the most popular Brassica vegetables in China, were selected for the experiments. The effects of these plants on the growth of S. frugiperda larvae were investigated. Besides, the changes in the midgut microbial community, including bacteria and fungi, when feeding on these plants were further determined by high-throughput sequencing. Our study provides more basic information for enriching the relationship between the gut microbial community of S. frugiperda and plant host fitness. These results could be beneficial to the biology and ecology research of S. frugiperda.

Results

The growth of S. frugiperda larvae on different diets

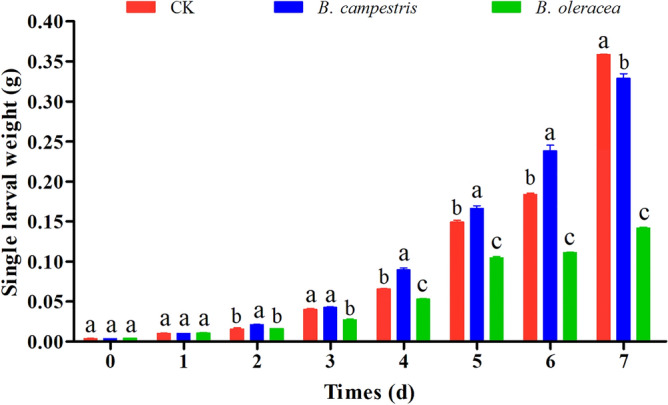

To examine the effects of cruciferous vegetables on the growth of S. frugiperda larvae, third instar larvae fed on different diets were weighed daily until day 7. Compared to the control group, the single larval weight in the group fed on B. campestris increased significantly in most instances. The average single larval weight decreased significantly after 2 days in the group fed on B. oleracea, and the growth inhibitory effect continued until day 7 (Fig. 1). These results indicate that the adaptation of S. frugiperda larvae to these two cruciferous vegetables was different.

Figure 1.

The effects of B. campestris and B. oleracea on the growth of S. frugiperda. The values of single larval weight for every day were shown as mean ± SEM (n = 20). Larvae fed on an artificial diet were used as a control. One-way ANOVA and the DMRT test (P < 0.05) were carried out for statistical analysis. Different letters above the bars represent groups with significant differences. The figure was generated with GraphPad Prism software (version 9.0) (https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/).

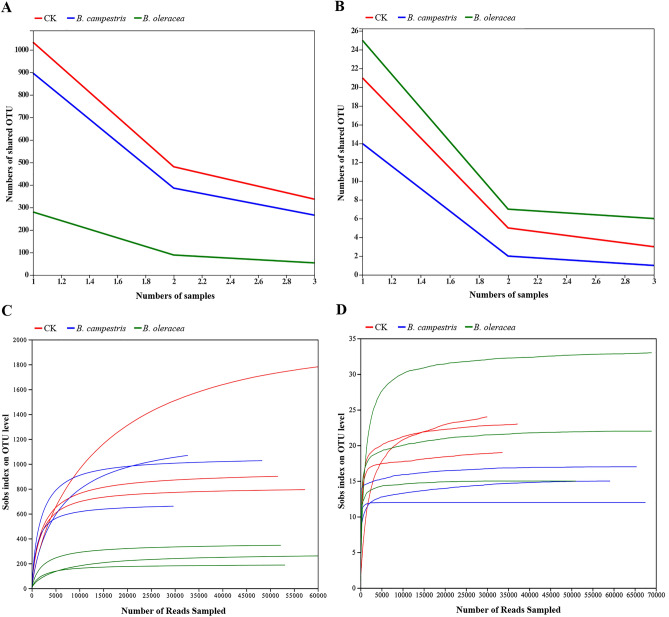

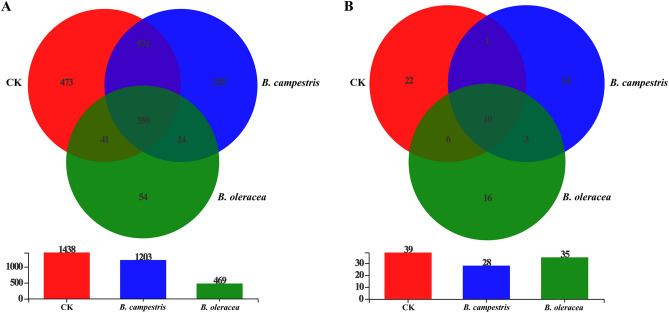

Statistics on data sequencing

After sequencing, a total of 465,257 and 482,783 high quality 16S rDNA and ITS sequences were obtained (Supplemental Table 1 and 2). The 16S rDNA sequences were classified into 3065 OTUs, 1771 species, 973 genera, 507 families, 312 orders, 144 classes, and 46 phyla. Likewise, all ITS sequences were classified into 117 OTUs, 91 species, 72 genera, 64 families, 44 orders, 22 classes, and 6 phyla. The rarefaction curves and core analysis of these sequences tend to be flat, indicating a sufficient sample number for the sequencing (Fig. 2). Besides, the number of bacterial species in the control group, the group fed on B. campestris and B. oleracea was 1438, 1203, and 469, respectively. Among them, 473, 255, and 54 species were the unique species in these groups, respectively. A total of 39, 28, and 35 fungal species were found in the control group, the group fed on B. campestris and B. oleracea, and the number of unique species was 22, 14, and 16, respectively (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

The quality analysis of OTUs in different samples. (A) OTU core analysis based on 16S rDNA sequencing. (B) OTU core analysis based on ITS sequencing. (C) OTU rarefaction curve derived from 16S rDNA sequencing. (D) OTU rarefaction curve derived from ITS sequencing. The figure was created by R project Vegan package (version 2.4–3) (https://github.com/vegandevs/vegan/releases/tag/v2.4-3).

Figure 3.

The analysis of the number of microbial species in different groups. (A) A Venn diagram and histogram of the bacterial species in different groups. (B) A Venn diagram and histogram of the fungal species in different groups. Red rings represent the species from the control group, blue rings represent the species from the group fed on B. campestris, and green rings represent the species from the group fed on B. oleracea, respectively. The figure was created by jvenn (version 1.0) (http://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/static/others/jvenn/example.html.).

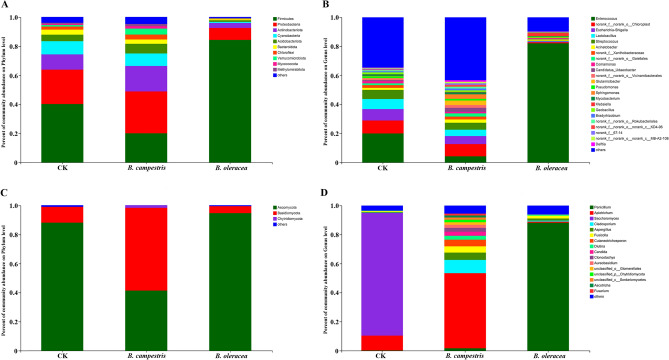

The microbial composition in the larval midgut

In this study, the microbial composition of the larval midgut in different groups was analyzed. For the bacterial composition, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteriota, Cyanobacteria, Acidobacteriota, Bacteroidota, Chloroflexi, Verrucomicrobiota, Myxococcota, and Methylomirabilota were the main phyla in the larval midgut. Compared to the control group, the abundance of Proteobacteria, Actinobacteriota, Acidobacteriota, Chloroflexi, Verrucomicrobiota, Myxococcota, and Methylomirabilota was increased in the group fed on B. campestris, while firmicutes had a decreased abundance. Besides, the bacterial composition in the larval midgut of the group fed on B. oleracea was different from that in the control group. Among the main phyla, the abundance of Firmicutes increased significantly, while the others decreased (Fig. 4A). In addition, Enterococcus, Escherichia Shigella, Lactobacillus, and Streptococcus were the most abundant genera in the control group, which accounted for 20.00%, 7.84%, 6.95%, and 6.29% of midgut bacteria, respectively. The abundance of these genera was decreased in the group fed on B. campestris when compared to the control group. In the group fed on B. oleracea, the abundance of Enterococcus was increased, which made up 82.19% of the midgut bacteria, while others were decreased (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

The microbial composition analysis in different groups of S. frugiperda larvae. (A) and (B) represent the bacterial composition in different groups at the phylum and genus levels. (C) and (D) represent the fungal composition in different groups at the phylum and genus levels. CK: the group fed on an artificial diet, B. campestris: the group fed on B. campestris; B. oleracea: the group fed on B. oleracea. The figure was created by R project Vegan package (version 2.4–3) (https://github.com/vegandevs/vegan/releases/tag/v2.4-3).

For the fungal composition, Ascomycota and Basidiomycota were the two main phyla in the larval midgut. In the control group, Ascomycota and Basidiomycota accounted for 88.11% and 10.86% of the midgut fungi, respectively. Compared to the control group, the abundance of Ascomycota in the group fed on B. campestris was decreased to 41.36%, while the abundance of Basidiomycota was increased to 56.91%. Moreover, the abundance of Ascomycota in the group fed on B. oleracea was increased to 94.64%, while the abundance of Basidiomycota was decreased to 4.78%. On a genus level, the control group’s larval midgut fungi were primarily composed of Saccharomyces (84.57%) and Apiotrichum (10.23%), whereas Apiotrichum (51.78%) was the most abundant genera in the group fed on B. campestris. Other major genera in the group fed on B. campestris included Cladosporium (9.15%), Aspergillus (5.03%), Cutaneotrichosporon (4.58%), Fusicolla (4.34%), Candida (2.77%), and Diutina (2.70%) (Fig. 4C). In the group fed on B. oleracea, the most abundant genera were Penicillium, which accounted for 88.25% of the midgut fungi (Fig. 4D). These results indicate that different host plants altered the gut microbial community composition of S. frugiperda larvae.

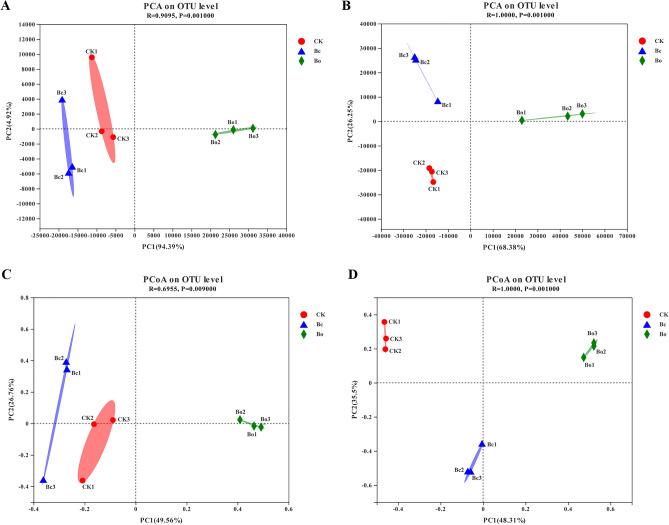

Comparative analysis of samples

The β diversity analysis of samples in this study was analyzed by Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Principal Co-ordinates Analysis (PCoA). As shown in Fig. 5A and B, the PCA analysis on the OUT level showed that the midgut bacteria and fungi displayed separate confidence ellipses. Similar results were also observed in the PCoA, where the samples in the same group were clustered together, and the degree of dispersion between different treatment groups was high (Fig. 5C and D). ANOSIM analyses (analysis of similarities) found that the P-values in the bacteria and fungi community analysis were 0.009 and 0.001 at the phylum level, respectively. All these results indicate significant differences in microbial community structures among different groups.

Figure 5.

The results of PCA and PCoA analyses of OTUs in all the samples. (A) PCA for 16S rDNA data at the OUT level. (B) PCoA for 16S rDNA data at the OUT level. (C) PCA for ITS data at the OUT level. (D) PCoA for ITS data at the OUT level. CK: the group fed on an artificial diet, Bc: the group fed on B. campestris; Bo: the group fed on B. oleracea. The figure was created by R project Vegan package (version 2.4–3) (https://github.com/vegandevs/vegan/releases/tag/v2.4-3).

Differential species analysis

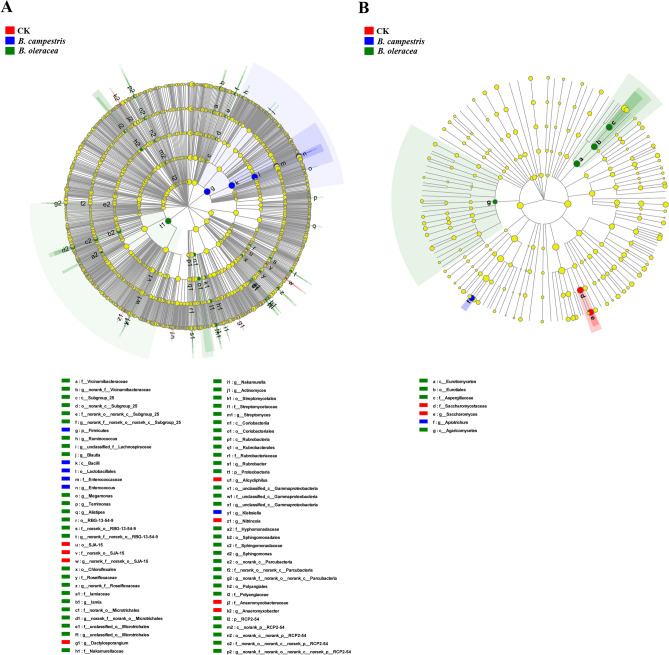

Significant differences in bacterial and fungal taxa were also identified by linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analyses. The LEfSe cladogram showed that 20 genera contributed to the different midgut bacterial communities in different groups. The genera Anaeromyxobacter, Alicycliphilus, Dactylosporangium, and Nitrincola were more abundant in the control group. Similarly, we found an enrichment of Sphingomonas, Nakamurella, Ruminococcus, Blautia, Gammaproteobacteria, Actinomyces, Streptomyces, Microtrichales, Alistipes, Megamonas, Iamia, Rubrobacter, Terrimonas, and Lachnospiraceae in the group fed on B. campestris, as well as Enterococcus and Klebsiella in the group fed on B. oleracea (Fig. 6A). The LEfSe analyses in the midgut fungi community revealed a significant enrichment of Saccharomyces in the B. campestris group and Apiotrichum in the B. oleracea group (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

The results of the linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) cladogram from the phylum to genus. The threshold of Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) was set at 2. (A) The 16S database’s LEfSe cladogram; (B) The ITS database’s LEfSe cladogram. CK: the group fed on an artificial diet, Bc: the group fed on B. campestris; Bo: the group fed on B. oleracea. The figure was created by LEfSe software (version 1.0) (http://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/galaxy/root?tool_id=lefse_upload).

Midgut microbial function classification

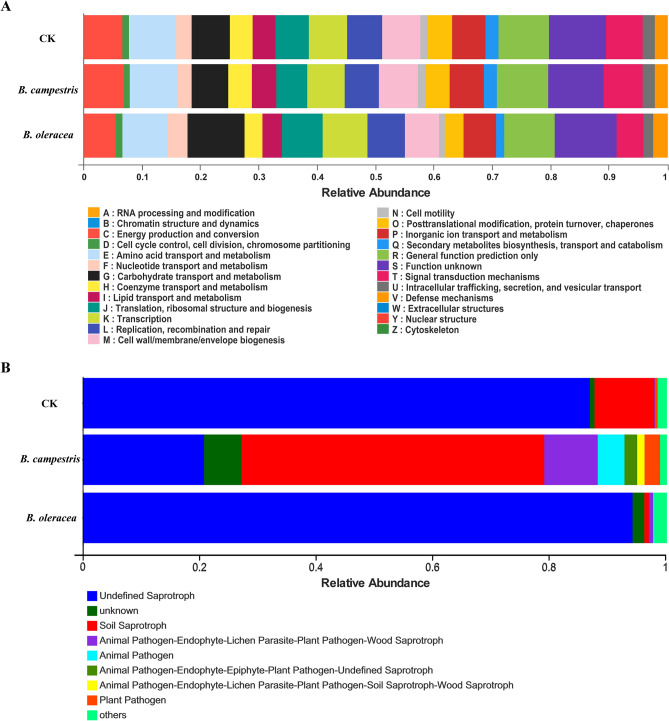

The tool PICRUSt was used for midgut bacterial function classification, and 25 bacterial function categories were classified. Compared to the control group, no COG category showed a significant difference in the group fed on B. campestris, while 22 categories had significantly different abundances in the group fed on B. oleracea (Fig. 7A). Among them, the categories of B (Chromatin structure and dynamics), C (Energy production and conversion), D (Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning), E (Amino acid transport and metabolism), F (Nucleotide transport and metabolism), H (Coenzyme transport and metabolism), J (Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis), L (Replication, recombination and repair), M (Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis), N (Cell motility), O (Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones), P (Inorganic ion transport and metabolism), Q (Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism), R (General function prediction only), S (Function unknown), T (Signal transduction mechanisms), U (Intracellular trafficking, secretion) had the P value less than 0.01 between control and the group fed on B. oleracea, while A (RNA processing and modification) G (Carbohydrate transport and metabolism) I (Lipid transport and metabolism) K (Transcription) had the P value less than 0.05. These results indicate that the convergence of midgut bacteria function between control and the group fed on B. campestris, while a significant effect on the function of midgut bacteria was observed in the group fed on B. oleracea.

Figure 7.

Functional classification of the gut microbial community in S. frugiperda larvae. (A) Bacterial function classification in S. frugiperda larval midgut with different diets by the PICRUSt tool. (B) Fungal function classification in S. frugiperda larval midgut with different diets by the FUNGuild tool. CK: the group fed on an artificial diet, B. campestris: the group fed on B. campestris; B. oleracea: the group fed on B. oleracea. The figure was created by PICRUSt (version 2.2.0) (https://github.com/picrust/picrust2/) and Tax4Fun software (version 0.3.1) (http://tax4fun.gobics.de/).

For fungal function classification, eight fungal functional guilds were enriched with an abundance of more than 0.01 in samples by the FUNGuild tool. Compared to the control group, the functional guilds of animal pathogen, animal pathogen-endophyte-lichen parasite-plant pathogen-wood saprotroph, plant pathogen, and undefined saprotroph maintained significantly higher abundance in the group fed on B. oleracea. The fungal function in the group fed on B. campestris was more affected. The guilds of animal pathogen, animal pathogen-endophyte-epiphyte-plant pathogen-undefined saprotroph, animal pathogen-endophyte-lichen parasite-plant pathogen-soil saprotroph-wood saprotroph, animal pathogen-endophyte-lichen parasite-plant pathogen-wood saprotroph, plant pathogen, soil saprotroph, and unknown showed different abundance significantly in the group fed on B. campestris (Fig. 7B).

Discussion

With the continuous expansion of the distribution of S. frugiperda around the world, the adaptability of larvae to a wide range of hosts has received widespread attention. As a polyphagous pest, a broad host range is essential for its survival and spread28. However, different host plants with varying palatability, nutritional content, and presence of secondary metabolites could affect the growth, development, and overall population fitness of S. frugiperda29. Recently, the adaptation of S. frugiperda larvae to many grain and oil crops such as maize, japonica or indica rice cultivars, sorghum, wheat, cotton, soybean, oilseed rape, and sunflower has been reported29–32. Besides, the biological parameters of S. frugiperda on other crops, such as three green manure crops, Astragalus sinicus L., Vicia villosa Roth, and Vicia sativa L., and three solanaceous vegetables, Capsicum annuum L., Solanum lycopersicum Mill., and Solanum melongena L., were also investigated33,34. In this study, two cruciferous vegetables, B. campestris and B. oleracea, were selected for feeding the larvae, and the weight changes during the 7 days of feeding were recorded. Our results showed that the larvae have good adaptability on B. campestris, but their growth and development are significantly inhibited on B. oleracea. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effect of cruciferous vegetables (B. campestris and B. oleracea) on S. frugiperda. The significant difference in larvae fed on different plants could be explained by the different nutritional content and presence of secondary metabolites in these two vegetables20,35. Given that these two cruciferous vegetables, B. campestris and B. oleracea, are currently the most popular and consumed vegetables, our results also provide a warning for vegetable cultivation because both types of vegetables can be harmed by S. frugiperda.

Microbes are the facultative and/or obligate symbionts for polyphagous insects to overcome the challenges of feeding on different host plants and have beneficial and fundamentally important impacts on insect biology, such as the growth and development, communication, adaption to the environment, and evolution of insects15,16,36. In this study, the midgut bacterial and fungal communities of S. frugiperda larvae fed on two cruciferous vegetables, B. campestris and B. oleracea, and an artificial diet, were analyzed. There was a significant difference in the diversity and abundance of the midgut bacterial and fungal communities when S. frugiperda larvae fed on different plants, which was similar to the results reported in many previous findings in Lepidoptera4,23,37. This is the first time we investigated the effects of cruciferous vegetables on the microorganisms in S. frugiperda larvae, which enriched the diversity of the midgut microbial community of S. frugiperda and provided a preliminary understanding of the role of midgut microbes in S. frugiperda larvae feeding on cruciferous vegetables.

Besides, the composition and diversity of the midgut microbes in S. frugiperda larvae with different diets were analyzed. As a food rich in nutrients, the bacterial species in the control group fed on the artificial diet are the most abundant. The number of bacterial species in the group fed on B. campestris was close to that in the control group, while it was the lowest in the group fed on B. oleracea. Besides, the bacterial diversity of different groups was significantly changed. Many endemic bacterial species were found in different groups. Because of the role of gut microbiota in insect metabolism and growth, the significantly different levels of the diversity of midgut bacteria among these groups could be explained by three reasons: bacteria in diets alter the larval midgut bacterial flora; the nutrients provided by B. campestris and B. oleracea are not sufficient for the survival of many bacteria in the control group; and the secondary metabolites in B. campestris and B. oleracea could inhibit the survival of bacteria in the control group, which in turn affects the contribution of bacteria to insects and regulates the growth of insects29. Furthermore, there was little difference in the number of fungal species in different groups, while the diversity was significantly plant-associated. The species endemic to different treatment groups may also be derived from the diets. The further function of these endemic species needs to be further explored. Our results further support the conclusion that gut fungal communities could also be affected by the host species38,39. Therefore, a revelation emerged that regulating the gut microbiota could be a potential approach for the control of S. frugiperda40.

The present studies showed that Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Actinomycetes are the dominant phyla in the gut bacterial community of S. frugiperda, which was similar to that of many lepidopteran insects, including Lymantria dispar asiatica, Lymantria xylina, Grapholita molesta, Spodoptera exigua, and so on2,3,40,41. The difference in the abundance of these phyla in S. frugiperda gut was also observed, which could be explained by different sampling areas, environments, and sequencing technology42,43. These results further confirm the indispensability of these bacteria in host insects. According to our results, the similarity in bacteria composition and growth trend observed in the control group and the group fed on B. campestris indicates a similar gut microbial environment and function, which further confirms the importance of the microbial environment for growth and development of host insects. While the abundance of Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Actinomycetes was changed significantly in the group fed on B. oleracea when compared to the control group. In addition, the bacterial composition of the S. frugiperda larval midgut at genus level was also changed by different plants. Among them, Enterococcus, the common dominant genus in most lepidopteran insects, showed the most abundance in the group feeding on B. oleracea when compared to the other two groups. The genus Lactobacillus has decreased in abundance significantly in the group fed on B. oleracea compared to the other two groups. Previous studies have shown that the functions of these phyla and genera, such as nutrient absorption, energy metabolism, the plant’s secondary metabolites degradation, insect immunity regulation, and so on44–47. Our results indicate that the changes in the larval midgut bacterial composition of S. frugiperda with B. oleracea treatment could be related to the growth of this pest. The specific functions of these phyla and genera in the host plant adaptation of S. frugiperda need to be further explored.

Previously, gut fungi were frequently overlooked in microbial research, despite their functions, such as nutrient supply, indigestible compound breakdown, and food detoxification, having been discovered48,49. In this study, significant differences existed within groups of fungal communities in the midgut of S. frugiperda larvae. Saccharomyces, Apiotrichum, and Penicillium were identified with the most abundance in the control group, the group fed on B. campestris and B. oleracea. Saccharomyces are important fungi for insects in terms of nutrient supply and may be involved in insect development50–53. Previous studies of Apiotrichum species indicated that they could be involved in lipid biosynthesis, and the degradation and detoxification of toxic substances54,55. Penicillium is well known for its ability to degrade cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin56,57. These results indicate that the major midgut fungal microbes of S. frugiperda larvae may be influenced by the constituents of different diets.

Furthermore, midgut bacterial function classification suggested that many functional categories were changed significantly in the group fed on B. oleracea compared to the other two groups, while the fungal guilds with significant changes were observed in the group fed on B. campestris. Our results confirmed the functional plasticity of the midgut bacterial and fungal microbes of S. frugiperda in response to different diets. Further studies are needed to reveal the details of the function of the midgut microbial community in the host plant fitness of S. frugiperda larvae.

In comparison to the control group, B. oleracea inhibited the growth of S. frugiperda larvae, while the group fed on B. campestris showed a similar growth trend. The results of Illumina sequencing revealed that the composition, structure, and function of the midgut microbial community in different groups varied. B. oleracea as the diet changed the midgut bacterial community and function, while B. campestris altered the fungal community and function significantly. Our preliminary results reveal the plasticity of the midgut microbiome in S. frugiperda larvae in response to different plants.

Materials and methods

Insect rearing

S. frugiperda larvae were collected from a corn field in Conghua District, Guangzhou City, Guangdong Province, China (23°55′N, 113°58′E) on June 20, 2019. The laboratory population had been established without pesticide exposure for more than two years. The larvae were maintained with an artificial diet, and the recipe for a 1 kg diet contained 100 g corn flour, 80 g soy flour, 26 g yeast powder, 26 g agar, 8.0 g vitamin C, 2.0 g sorbic acid, 1.0 g choline chloride, 0.2 g inositol, and 0.2 g cholesterol58. The adults were fed with 10% honey water. The insects were cultured in an incubator with stable conditions of a 12-h light / dark cycle at 25 ± 1 °C with 75–85% humidity.

Treatments

Newly hatched larvae feed on the artificial diet as 3rd instar larvae. Then larvae of the same size were selected for the experiments. The leaves of organic pakchoi and purple cabbage without insecticide exposure were purchased from a local agricultural company (Guangzhou, China). The surfaces of all the leaves were washed with water, sterilized with a 75% ethanol solution, and then rinsed in sterilized distilled water. The larvae fed on the leaves of B. campestris and B. oleracea were set as two experimental groups, respectively. At the same time, larvae fed on an artificial diet were used as a control group. The larvae were housed individually in the Drosophila vials (25 mm diameter, 95 mm height, Crystalgen Inc., USA) to prevent cannibalism, and the diet in the vials was changed every day. Twenty larvae were used as one replicate, and three replicates were set for each group. The body weight of larvae in different groups was recorded daily until day 7.

Sample collection

The larvae fed on different diets for 7 days were used for sample collection. The larvae were sterilized with a 75% ethanol solution, then washed with sterile water three times. The clean bench (AIRTECH, Jiangsu, China) was exposed to UV for more than 30 min. The larvae were then dissected on a sterile clean bench, and the midgut contents were collected in 1.5 mL sterile centrifuge tubes. The samples were then quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C. Three biological replicates were performed for each treatment, with 15 larval midgut contents collected per replicate.

DNA isolation and PCR amplification

The genomic DNA for each sample was isolated with an E.Z.N.A.® soil DNA kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, U.S.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality of genomic DNA was analyzed with a 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and a NanoDrop2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used for DNA concentration and purity determination. After passing the quality inspection, all the genomic DNA from different samples was used for subsequent experiments. In order to analyze the changes in the gut bacterial and fungal communities induced by cruciferous vegetables, the 16S rDNA V3-V4 variable region and Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) ITS1-ITS2 region amplifications were performed, and the same genomic DNA was used as the template. For 16S rDNA amplification, the primers 338F (5'-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3') and 806R (5'-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3') were used. Besides, the primers ITS1F (5'-CTTGTTCATTTAGGAAGTAA-3') and ITS2R (5'-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3') were used for ITS amplification. The PCR reaction system for 16S rRNA and ITS amplifications was basically identical except for primers and is as follows: 4 μL of 5 × TransStart FastPfu Buffer, 2 μL of 2.5 mM dNTPs, 0.8 μL of 5 μM forward primer, 0.8 μL of 5 μM reverse primer, 0.4 μL of TransStart FastPfu DNA Polymerase, and 10 ng of genomic DNA. The procedure for PCR amplification was executed at 95 °C for 3 min; 27 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s; followed by a stable extension at 72 °C for 10 min, and then kept at 4 °C. Three technical replicates were performed per sample, and three biological replicates were carried out for each treatment.

Illumina sequencing and sequence analysis

The PCR products were detected with a 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and the target bands were purified with the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, CA, USA). After being quantified using a Quantus™ Fluorometer (Promega, USA), the purified PCR products were used for library construction with the NEXTflex™ Rapid DNA-Seq Kit (Bioo Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Finally, the amplicons from different libraries were sequenced on an Illumina Miseq PE300/NovaSeq PE250 platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA).

After sequencing, the raw data was quality controlled by removing low-quality reads using fastp software (https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp, version 0.20.0). Then the clean reads were spliced using FLASH software (http://www.cbcb.umd.edu/software/flash, version 1.2.7). The software UPARSE (http://drive5.com/uparse/, version 7.1) was used for the operational taxonomic units (OTUs) cluster and chimera removal with the 97% similarity cutoff. For 16S rDNA sequences, the species taxonomy annotation was performed using the RDP classifier (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/, version 2.2) and the Silva 16S rRNA database (v138), with the alignment threshold set to 70%. For ITS sequences, the UNITE database 8.0 was selected for the alignment. All the bioinformatics analyses were performed using the online platform of Majorbio Cloud Platform (www.majorbio.com).

Data analysis

Each treatment was replicated three times, and the results were expressed as mean values ± SEM. One-way ANOVA followed by DMRT and a student’s t test were conducted during statistical analyses (P < 0.05).

Ethics declarations

This article does not involve any human participants and/or animals, other than the fall armyworm, S. frugiperda.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32102221), the fund from Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (No. 2020B020223004), the Innovation Team Project in Guangdong Provincial Department of Education (2017KCXTD018). The authors sincerely thank Prof. Ming-Shun Chen of Kansas State University for revising this manuscript.

Author contributions

B.S. and J.L. conceived and designed the experiments. Y.L., L.L., X.C. and X.Y. performed the experiments, maintained the insect culture, and analyzed the data. B.S. finished the original draft and J.L. edited and reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available in the Supplementary Materials. The raw data of larval midgut bacteria and fungi have been uploaded to NCBI SRA database with the numbers of PRJNA843198 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA843198) and PRJNA843200 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA843200).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Lin Jintian, Email: linjtian@163.com.

Shu Benshui, Email: shubenshui@126.com.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-17278-w.

References

- 1.Douglas AE. Multiorganismal insects: diversity and function of resident microorganisms. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2015;60:17–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma Q, et al. Gut bacterial communities of Lymantria xylina and their associations with host development and diet. Microorganisms. 2021;9(9):1860. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9091860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuan X, et al. Comparison of gut bacterial communities of Grapholita molesta (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) reared on different host plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22(13):6843. doi: 10.3390/ijms22136843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Y, Shen Z, Yu J, Li Z, Liu X, Xu H. Comparison of gut bacterial communities and their associations with host diets in four fruit borers. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020;76(4):1353–1362. doi: 10.1002/ps.5646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lauzon CR, Sjogren RE, Prokopy RJ. Enzymatic capabilities of bacteria associated with apple maggot flies: A postulated role in attraction. J. Chem. Ecol. 2000;26:953–967. doi: 10.1023/A:1005460225664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Douglas AE. The microbial dimension in insect nutritional ecology. Funct. Ecol. 2009;23:38–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2008.01442.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaltenpoth M, Engl T. Defensive microbial symbionts in Hymenoptera. Funct. Ecol. 2014;28(2):315–327. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruner-Montero, G., Wood, M., Horn, H. A., Gemperline, E., Li, L. & Currie, C. R. Symbiont-mediated protection of acromyrmex leaf-cutter ants from the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. mBio12(6), e0188521 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Zhang Q, et al. Enterobacter hormaechei in the intestines of housefly larvae promotes host growth by inhibiting harmful intestinal bacteria. Parasit. Vector. 2021;14(1):598. doi: 10.1186/s13071-021-05053-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang, S., et al. The gut microbiota in Camellia weevils are influenced by plant secondary metabolites and contribute to saponin degradation. mSystems5(2), e00692–19 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Sato Y, et al. Insecticide resistance by a host-symbiont reciprocal detoxification. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):6432. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26649-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jordan HR, Tomberlin JK. Microbial influence on reproduction, conversion, and growth of mass produced insects. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2021;48:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2021.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strano CP, Malacrinò A, Campolo O, Palmeri V. Influence of host plant on Thaumetopoea pityocampa gut bacterial community. Microb. Ecol. 2018;75(2):487–494. doi: 10.1007/s00248-017-1019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mason CJ, et al. Diet influences proliferation and stability of gut bacterial populations in herbivorous lepidopteran larvae. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(3):e0229848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammer TJ, Janzen DH, Hallwachs W, Jaffe SP, Fierer N. Caterpillars lack a resident gut microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:9641–9646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707186114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scully ED, et al. Host-plant induced changes in microbial community structure and midgut gene expression in an invasive polyphage (Anoplophora glabripennis) Sci. Rep. 2018;8(1):9620. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27476-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goergen G, Kumar PL, Sankung SB, Togola A, Tamò MF. irst report of outbreaks of the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (J E Smith) (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae), a new alien invasive pest in west and central Africa. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(10):e0165632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagoshi RN, et al. Southeastern Asia fall armyworms are closely related to populations in Africa and India, consistent with common origin and recent migration. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58249-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beuzelin, J. M., Larsen, D. J., Roldán, E. L. & Schwan Resende, E. Susceptibility to chlorantraniliprole in fall armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) populations infesting sweet corn in southern florida. J. Econ. Entomol.115(1), 224–232 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Montezano DG, et al. Host plants of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in the Americas. Afr. Entomol. 2018;26:286–300. doi: 10.4001/003.026.0286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones AG, Mason CJ, Felton GW, Hoover K. Host plant and population source drive diversity of microbial gut communities in two polyphagous insects. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):2792. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39163-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mason CJ, Hoover K, Felton GW. Effects of maize (Zea mays) genotypes and microbial sources in shaping fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) gut bacterial communities. Sci. Rep. 2021;119(1):4429. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83497-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lv D, et al. Comparison of gut bacterial communities of fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) reared on different host plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22(20):11266. doi: 10.3390/ijms222011266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen YP, et al. Effects of host plants on bacterial community structure in larvae midgut of Spodoptera frugiperda. Insects. 2022;13(4):373. doi: 10.3390/insects13040373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen J, et al. Cabbage cultivars influence transfer and toxicity of cadmium in soil-Chinese flowering cabbage Brassica campestris-cutworm Spodoptera litura larvae. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021;213:112076. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdullah A, Ullah MI, Raza AM, Arshad M, Afzal M. Host plant selection affects biological parameters in armyworm, Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Pak. J. Zool. 2019;51(6):2117–2123. doi: 10.17582/journal.pjz/2019.51.6.2117.2123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gopalakrishnan R, Kalia VK. Biology and biometric characteristics of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) reared on different host plants with regard to diet. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022;78(5):2043–2051. doi: 10.1002/ps.6830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He L, Wang T, Chen Y, Ge S, Wyckhuys Kris AG, Wu K. Larval diet affects development and reproduction of East Asian strain of the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda. J. Integr. Agr. 2021;20(3):736–744. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(19)62879-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He L, Wu Q, Gao X, Wu K. Population life tables for the invasive fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda fed on major oil crops planted in China. J. Integr. Agr. 2021;20(3):745–754. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(20)63274-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie W, et al. Age-stage, two-sex life table analysis of Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) reared on maize and kidney bean. Chem. Biol. Technol. Ag. 2021;8:44. doi: 10.1186/s40538-021-00241-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gopalakrishnan R, Kalia VK. Biology and biometric characteristics of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) reared on different host plants with regard to diet. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022;78(5):2043–2051. doi: 10.1002/ps.6830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang P, et al. Host selection and adaptation of the invasive pest Spodoptera frugiperda to indica and japonica rice cultivars. Entomol. Gen. 2022 doi: 10.1127/entomologia/2022/1330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu L, et al. Fitness of fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda to three solanaceous vegetables. J. Integr. Agr. 2021;20(3):755–763. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(20)63476-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu F, et al. Population development, fecundity, and flight of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) reared on three green manure crops: implications for an ecologically based pest management approach in China. J. Econ. Entomol. 2022;115(1):124–132. doi: 10.1093/jee/toab235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hou ML, Sheng CF. Effects of different foods on growth, development and reproduction of cotton bollworm, Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Acta Entomol. Sin. 2000;43:168–175. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang XL, et al. Variability of gut microbiota across the life cycle of Grapholita molesta (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:1366. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Näsvall K, et al. Host plant diet affects growth and induces altered gene expression and microbiome composition in the wood white (Leptidea sinapis) butterfly. Mol. Ecol. 2021;30(2):499–516. doi: 10.1111/mec.15745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ort BS, Bantay RM, Pantoja NA, O'Grady PM. Fungal diversity associated with Hawaiian Drosophila host plants. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e40550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Majumder R, Sutcliffe B, Taylor PW, Chapman TA. Fruit host-dependent fungal communities in the microbiome of wild Queensland fruit fly larvae. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):16550. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73649-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zeng JY, et al. Avermectin stress varied structure and function of gut microbial community in Lymantria dispar asiatica (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae) larvae. Pestic. Biochem Physiol. 2020;164:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2020.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen C, Zhang J, Tan H, Fu Z, Wang X. Characterization of the gut microbiome in the beet armyworm Spodoptera exigua in response to the short-term thermal stress. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2022;25:101863. doi: 10.1016/j.aspen.2021.101863. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rozadilla G, Cabrera NA, Virla EG, Greco NM, McCarthy CB. Gut microbiota of Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) larvae as revealed by metatranscriptomic analysis. J. Appl. Entomol. 2020;144:351–363. doi: 10.1111/jen.12742. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ugwu JA, Liu M, Sun H, Asiegbu FO. Microbiome of the larvae of Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) from maize plants. J. Appl. Entomol. 2020;144:764–776. doi: 10.1111/jen.12821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang X, et al. Variability of gut microbiota across the life cycle of Grapholita molesta (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:1366. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang FY, et al. Differential profiles of gut microbiota and metabolites associated with host shift of Plutella xylostella. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:6283. doi: 10.3390/ijms21176283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shao Y, et al. Crystallization of alpha- and beta-carotene in the foregut of Spodoptera larvae feeding on a toxic food plant. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011;41:273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Santos TA, Scorzoni L, Correia R, Junqueira JC, Anbinder AL. Interaction between Lactobacillus reuteri and periodontopathogenic bacteria using in vitro and in vivo (G mellonella) approaches. Pathog. Dis. 2020;78(8):ftaa044. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftaa044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Biedermann P, Vega FE. Ecology and evolution of insect-fungus mutualisms. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020;65:431–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011019-024910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo Q, Yao Z, Cai Z, Bai S, Zhang H. Gut fungal community and its probiotic effect on Bactrocera dorsalis. Insect Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1111/1744-7917.12986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bing XL, Gerlach J, Loeb G, Buchon N. Nutrient-dependent impact of microbes on Drosophila suzukii development. MBio. 2018;9:e02199–e2117. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02199-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keebaugh ES, Ryuichi Y, Benjamin O, Ludington WB, Ja WW. Microbial quantity impacts Drosophila nutrition, development, and lifespan. Iscience. 2018;4:247–259. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deutscher AT, Chapman TA, Shuttleworth LA, Riegler M, Reynolds OL. Tephritid-microbial interactions to enhance fruit fly performance in sterile insect technique programs. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19:287. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1650-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gurung K, Wertheim B, Falcao Salles J. The microbiome of pest insects: it is not just bacteria. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2019;167:156–170. doi: 10.1111/eea.12768. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun J, Xia Y, Ming D. Whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis of Apiotrichum mycotoxinivorans: Predicting putative zearalenone-degradation enzymes. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:1866. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qian XJ, et al. Bioconversion of volatile fatty acids into lipids by the oleaginous yeast Apiotrichum porosum DSM27194. Fuel. 2021;290:119811. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.119811. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Passos DF, Pereira N, Castro AM. A comparative review of recent advances in cellulases production by Aspergillus, Penicillium and Trichoderma strains and their use for lignocellulose deconstruction. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain Chem. 2018;14:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cogsc.2018.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Višňovská D, et al. Caterpillar gut and host plant phylloplane mycobiomes differ: a new perspective on fungal involvement in insect guts. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020;96(9):fiaa116. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiaa116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shu B, et al. Growth inhibition of Spodoptera frugiperda larvae by camptothecin correlates with alteration of the structures and gene expression profiles of the midgut. BMC Genomics. 2021;22:391. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-07726-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the Supplementary Materials. The raw data of larval midgut bacteria and fungi have been uploaded to NCBI SRA database with the numbers of PRJNA843198 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA843198) and PRJNA843200 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA843200).