Abstract

A vegetative insecticidal protein (VIP)-encoding gene from a local isolate of Bacillus thuringiensis has been cloned, sequenced, and expressed in Escherichia coli. The expressed protein shows insecticidal activity against several lepidopteran pests but is ineffective against Agrotis ipsilon. Comparison of the amino acid sequence with those of reported VIPs revealed a few differences. Analysis of insecticidal activity with N- and C-terminus deletion mutants suggests a differential mode of action of VIP against different pests.

The gram-positive bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis is known to produce parasporal crystalline inclusions during the late exponential phase of growth (8). These crystals consist of several polypeptides, some of which are insecticidal or nematocidal. Upon ingestion by insects, these toxins are proteolytically activated, and after interaction with specific receptors at the mid-gut, they cause larval death (5). Since these toxins are highly specific, they are extremely useful in controlling targeted agricultural pests. Over the past several years, more than 100 different polypeptides have been identified, and several of them have been employed in insect management programs (8). The diversity, specificity, and usefulness of these insecticidal polypeptides have encouraged searches among diverse niches for new strains displaying novel insecticidal polypeptides. In addition to the crystal-associated toxic polypeptides, some insecticidal proteins produced during vegetative growth of the bacteria have also been identified. These proteins, called vegetative insecticidal proteins (VIPs), were reported from about 15% of the B. thuringiensis strains analyzed (2). We have screened several strains of B. thuringiensis obtained from soil samples collected from different parts of India for the presence of homologues of the VIP. Based on the reported gene sequences, we designed PCR DNA primers for the detection of the vip gene in strains held in our collection. As a result of the screening program, we have cloned, sequenced, and expressed a vegetative insecticidal toxin-coding gene from one of the isolates in our collection. The toxicity spectrum of the Escherichia coli-expressed recombinant protein has been evaluated against five lepidopteran pests. By deletion analysis, we have characterized the minimal toxic polypeptide segment that retains insecticidal activity. The toxicity of deleted VIP against lepidopteran pests suggested a differential mode of action against different pests.

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Different isolates of B. thuringiensis were enriched from soil samples collected from different geographical locations within India. For routine use in the laboratory, the isolates were maintained in nutrient medium (Difco), and for long-term storage, the isolates were stored as glycerol stocks at −70°C. E. coli strain M15 was obtained from Qiagen (Braunschweig, Germany) and, when required, was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm.

Oligonucleotide PCR primers.

Primers to screen for the presence of vip homologue were designed based on the published sequence of genes coding for Vip3A(a) and Vip3A(b) (GenBank database accession no. L48811 and L48812, respectively). The positions and sequences of the vip screening primers are as follows: forward primer, vip1, nucleotides (nt) 689 to 710, 5′ AGTTTACAAGAAATAAGTGTTA; and reverse primer, vip2, nt 1437 to 1457, 5′ CCTACCATTACATCGTGGAAT. Oligonucleotides were synthesized and supplied by Integrated DNA Technologies. These primers were used to screen for the presence of vip-like genes in our collection of strains.

Preparation of chromosomal DNA and PCR amplification of a fragment of VIP.

Total DNA of different isolates of B. thuringiensis was isolated by the protocol described by Ausubel et al. (1). The presence of vip homologue was screened by using total DNA as template and the forward and reverse PCR primers vip1 and vip2, respectively. The forward primer, vip1, corresponds to nt 689 to 710, and the reverse primer, vip2, corresponds to positions 1437 to 1457 of VIP accession no. L48811. The conditions for PCR amplification were as follows: a single denaturation step of 90 s at 95°C, a step cycle program set for 30 cycles (with each cycle consisting of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 48°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min), and an extra extension step for 5 min at 72°C. Following amplification, the PCR product was resolved on 0.8% agarose, and the product was eluted with a gel extraction kit (Qiagen). The 0.7-kb fragment was cloned into vector pGEM-T (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and sequenced with vector-based primers by Sanger's dideoxy chain termination method (7). The PCR-amplified and cloned homologue of vip was radioactively labeled with a Bethesda Research Laboratories random primer labeling kit incorporating [α-32P]ATP and used as a probe to screen genomic DNA dot blotted on a Hybond N+ membrane prepared from different isolates of B. thuringiensis. The DNA blots were processed and visualized by standard protocols as described by Sambrook et al. (6). The total genomic DNA of the vip-positive isolate was size fractionated to a 2- to 5-kb range with ClaI, and a library was made in E. coli DH5α by using vector pBSK (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). Upon screening with the radiolabeled, 0.7-kb vip probe, a recombinant bearing an insert of 2.9 kb was identified (pBVIP). The insert was sequenced by gene walking, and the sequence was submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Bethesda, Md.) for homology scan.

Expression of vip in E. coli

The upstream untranslated region of vip was deleted by using the clone pBVIP as template and with the PCR primer vip0 (5′ CAGATCTATGAACAAGAATAATA). The amplification with vip0 and reverse primer vip2 allowed insertion of a BglII site and an initiation codon (ATG) and resulted in amplification of a 0.6-kb fragment. The amplified 0.6-kb fragment was cloned into pGEM-T (pGVIP), and several clones were sequenced to detect any PCR-based mutation in the amplified product. The vip gene was completed by inserting the 1.7-kb 3′ fragment from pBVIP and ligating it at the PstI site of pGVIP to generate vector pGVIPM. The complete open reading frame was excised as a BglII-SacI fragment and cloned at the corresponding site in vector pET29a (Novagen) to finally obtain vector pETVIPM.

To delete the putative N-terminal signal sequence from VIP, an N-terminus primer, vip01, extending up to nt 117 (39 amino acid residues), was used together with vip2 to amplify a 0.57-kb fragment. The initiation codon ATG was introduced from the deletion specifying primer vip01 (5′GGGATCCAGATCTATGGATAAGGTGGTGATCT-3′). The subsequent steps for cloning into the pETVIP were identical to those for expression of the native vip. Deletions from the C-terminal end were constructed by using the Promega Erase a Base system following the manufacturer's recommended protocol. In brief, vector pETVIPM was restriction digested with EcoRI and SacI. The 5′ overhang of the EcoRI site was digested with Exo III mung bean nuclease, and the ends were blunted with S1 nuclease, ligated, and transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells. The protocols followed for the growth of bacteria, preparation of plasmid, and transformation were described by Sambrook et al. (6). The deletions were mapped by using the reverse sequencing vector-based primer.

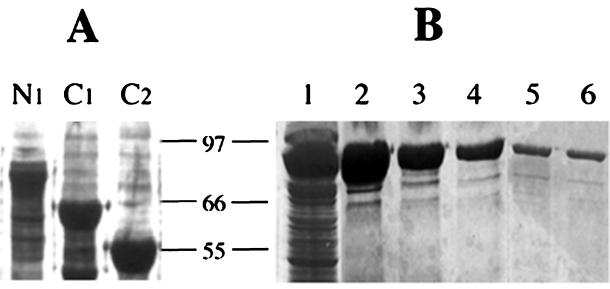

The native vip gene and its deletion were excised as KpnI-SalI fragments from pETVIPM and cloned at corresponding sites in expression vector pQE30 (Qiagen). These constructs were transformed into E. coli M15 cells following standard protocol. The cells expressing native vip and different deletions were grown in LB broth to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6, and their expression was induced by adding 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Cultures were grown further for 2 h at 37°C, and cells were harvested by centrifugation. The cell pellet was washed with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) containing 10 mM imidazole and 300 mM NaCl (buffer A). The cell pellet was resuspended in the same buffer and sonicated at a power output of 100 W three times for 30 s each. The resulting cell pellet from suspension was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 min. The expression of vip and its deletions was checked in cytosolic supernatant and pellet. The protein was expressed into the soluble cytosolic fraction and constituted about 40% of total protein (Fig. 1B, lane 1). The expressed proteins carried a His tag at the N terminus, facilitating their purification by Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) affinity chromatography. The cytosolic extract containing VIP or its deletions was added to Ni-NTA slurry equilibrated with buffer A, and the binding of the His-tagged proteins was carried out at 4°C on an end-over-end mixer.

FIG. 1.

Expression and purification of deletion mutants of VIP in E. coli M15. (A) Lanes: N1, N-terminal deletion of 39 amino acid residues; C1 and C2 represent 154- and 220-amino-acid deletions, respectively. (B) Purification of VIP by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. VIP was expressed as a soluble protein in E. coli M15 cells. VIP was purified by passing cytosolic extract through an Ni-NTA column and eluting it with a linear gradient of 10 to 150 mM imidazole. Lanes: 1, crude cytosolic extract; 2 to 6, different fractions obtained after elution from the Ni-NTA column.

The Ni-NTA slurry was washed with buffer A and packed into a 5-ml column. The bound proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of 10 to 150 mM imidazole prepared in buffer A. The VIP or its deletions eluted at an imidazole concentration of between 75 and 100 mM (Fig. 1B). The fractions containing the desired protein were pooled and dialyzed extensively against water, lyophilized, and used as a source of insecticidal protein when required. The purification protocol yielded more than 90% pure VIP.

Toxin purity was checked by electrophoresis by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (10% polyacrylamide) and staining with Coomassie blue. Samples were also transferred to Hybond C+ (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) membrane for immunoblotting with rabbit anti-VIP antibody and followed by a second antibody-alkaline phosphate conjugate. The Coomassie blue-stained gels were scanned (Alpha Innotech) and quantitated with various amounts of bovine serum albumin resolved separately by SDS-PAGE.

Screening of insecticidal activity of native VIP and various deletion mutants.

Cultures of target insect pests, Spodoptera litura (fall army worm), Agrotis ipsilon (black cut worm), Plutella xylostella (diamondback moth), Chilo partellus (spotted stalk borer), and Phthorimea opercullela (potato tuber moth), were maintained in the laboratory at 26 ± 1oC and 65% relative humidity at the Project Directorate for Biological Control, Bangalore, India. The leaves were thoroughly washed with 0.01% Triton X-100 and blotted dry. For screening of insecticidal activity against P. opercullela, sprouted potatoes were sliced, and the exposed cut portion was covered with molten wax (melting point, 50°C) to prevent fungal and bacterial infection. Control treatments received only 0.01% Triton X-100 in water. Stock solutions of the VIP and deleted VIP toxins were prepared in autoclaved water and applied at the desired concentration on washed leaves of castor (S. litura), maize (A. ipsilon and C. partellus), cabbage (P. xylostella), potato (P. opercullela), and potato sprouts (P. opercullela). Five groups of 20 first instar larvae of different insects were released on the leaf surface coated with the VIP toxin. Treated leaves along with larvae were placed inside a glass tube (20 by 3.5 cm), sealed with a muslin cloth, and kept at 26 ± 1°C and a relative humidity of 65%. Mortality was recorded after 24 h. Each treatment was replicated five times. The 50% lethal concentration and regression equation were obtained by Probit analysis (3).

Cloning, sequencing, and expression of VIP-encoding gene.

Based on the gene sequences of vip3A(a) and vip3A(b), a set of primers were synthesized and used to screen strains of B. thuringiensis maintained in our collection. These strains were isolated from soil samples collected from different locations in India. Of the 49 strains screened, one isolate, Bt-Vip, amplified a fragment of the expected size. By using the amplified fragment as a probe, a genomic library of the isolate prepared in vector pBSK in E. coli was screened by Southern hybridization. A positive clone was identified and analyzed further. A 2.9-kb insert in the clone was sequenced by walking. Upon computer-assisted translation of the gene sequence and comparison with other known vip genes, the following differences were revealed. Of the other two vip genes reported so far, the translated sequence differed at three amino acid residues: with vip3(a) at Q284→K, K742→G, and P770→S. With vip3A(b), the following differences were observed: P291→K, P406→E, and E742→G (Table 1). The vip gene was cloned into vector pQE30 in E. coli M15, and the protein was expressed by inducing an actively growing culture with IPTG. VIP was expressed into the cytosolic fraction of E. coli M15 cells.

TABLE 1.

Differences in amino acid residues in the VIPs

| Toxin | Amino acid residue at position:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 284 | 291 | 406 | 742 | 770 | |

| Vip3A(a) | Q | T | E | K | P |

| Vip3A(b) | K | P | G | E | S |

| Vip-S (this study) | K | T | E | G | S |

Toxicity spectrum of VIP toxin.

The E. coli-expressed toxin was evaluated against several pests and found to be active against the following pests (Table 2): C. partellus (spotted stalk borer), S. litura (fall army worm), P. opercullela (potato tuber moth), and P. xylostella. Interestingly, the VIP described by us was not toxic to A. ipsilon, as has been reported earlier (2). At present, it is difficult to understand the reasons for the observed lack of insecticidal activity against A. ipsilon by VIP described here. Is it due to diversity in A. ipsilon, or are the three different amino acid residues in VIP critical for toxicity? With the current data available, it is difficult to explain the observed lack of activity against A. ipsilon. Exposure of first instar larvae for up to 3 days also did not result in any aberration in larval growth increases, weight gain, or morphology.

TABLE 2.

Toxicity of vegetative insecticidal toxin against various lepidopteran pestsa

| Insect | LC50 (ng/cm2)b | Regression equation |

|---|---|---|

| Phthorimea opercullela | 370 | y = 2.5702 + 0.9461x |

| Agrotis ipsilon | 2,165 | y = 4.4386 + 0.1683x |

| Chilo partellus | 8 | y = 3.1067 + 2.1016x |

| Spodoptera litura | 5 | y = 3.889 + 1.693x |

| Plutella xylostella | 36 | y = 1.2648 + 2.4x |

Toxicity treatment was replicated five times with 20 first instar larvae each time. Mortality was recorded after 24 h of incubation.

LC50, 50% lethal concentration.

Deletion analysis for determining the toxin fragment.

VIP is a secretory protein, and a putative secretory signal has been predicted to be located at the N-terminal end spanning residues 5 to 15 (2). To determine the minimum active toxin fragment, N- or C-terminus deletions were constructed and expressed in E. coli. The proteins were expressed in E. coli and evaluated for toxicity against larvae of C. partellus and S. litura. Deletion of 39 amino acids from the N terminus did not alter its toxicity against the larvae of C. partellus. On the other hand, a remarkable reduction in its toxicity was observed against larvae of S. litura (Table 3). Similarly C-terminus deletion of up to 154 amino acid residues differentially affected toxicity against larvae of C. partellus and S. litura. Marginal reduction in toxicity towards the larvae of C. partellus was observed. However, its activity against S. litura was completely abolished. These results suggest that the toxin mediates its activity against two pests, possibly by different mechanisms. In S. litura, signal peptide-directed insertion of toxin into the membranes is probably required for lethality, while activity against C. partellus is independent of such membrane-targeted action. In the absence of information about the receptor for VIP toxins, it is not possible to speculate about factors responsible for the observed differences in toxicity of C-terminus-deleted VIP.

TABLE 3.

Toxicity of N- and C-terminus-deleted VIP against C. partellus and S. lituraa

| Residues deleted | Toxicity result for:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

C. partellus

|

S. litura

|

|||

| LC50 (ng/cm2) | Regression equation | LC50 (ng/cm2) | Regression equation | |

| Control | 8 | y = 3.1067 + 2.1016x | 5 | y = 3.889 + 1.693x |

| N-terminal 39 | 8 | y = 3.0821 + 2.1326x | 530 | y = 4.0192 + 3.6x |

| C-terminal 154 | 28 | y = 0.9533 + 2.7963x | NAb | NA |

| C-terminal 220 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Toxicity treatment was replicated five times with 20 first instar larvae each time. Mortality was recorded after 24 h of incubation.

NA, no activity.

The VIPs represent a structurally different group of insecticidal toxins produced by the strains of B. thuringiensis. With several laboratories reporting development of resistance in insects against insecticidal crystal proteins of B. thuringiensis, these toxins offer a promise of extending the usefulness of B. thuringiensis toxins to delay onset of resistance in insects (4, 9), since the structural divergence of VIPs is suggestive of a different mode of action.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the vip gene has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. Y17158).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidelman J G, Struhl K E. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estruch J, Warren G W, Mullins M A, Nye G J, Craig J A, Koziel H G. Vip3A, a novel Bacillus thuringiensis vegetative insecticidal protein with a wide spectrum of activities against lepidopteran insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5389–5394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finney D J. Probit analysis. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maagd R A, Bosch D, Stiekema W. Bacillus thuringensis mediated insect resistance in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 1999;4:9–13. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(98)01356-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajamohan F, Lee M K, Dean D H. Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal proteins: molecular mode of action. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1998;60:1–27. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnepf E, Crickmore N, Van Rie J, Lereclus D, Baum J, Feitelson J, Ziegler D R, Dean D H. Bacillus thuringiensis and its pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:775–806. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.775-806.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tabashnik B E, Roush R T, Earle E D, Shelton D M. Resistance to Bt toxins. Science. 2000;287:42. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5450.41d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]