Abstract

Mathematical models are critical to understand the spread of pathogens in a population and evaluate the effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs). A plethora of optimal strategies has been recently developed to minimize either the infected peak prevalence () or the epidemic final size (). While most of them optimize a simple cost function along a fixed finite-time horizon, no consensus has been reached about how to simultaneously handle the and the , while minimizing the intervention’s side effects. In this work, based on a new characterization of the dynamical behaviour of SIR-type models under control actions (including the stability of equilibrium sets in terms of herd immunity), we study how to minimize the while keeping the controlled at any time. A procedure is proposed to tailor NPIs by separating transient from stationary control objectives: the potential benefits of the strategy are illustrated by a detailed analysis and simulation results related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Optimal control, SIR model, Infected peak prevalence, Epidemic final size, Herd immunity

1. Introduction

Infectious disease outbreaks are latent threats to humankind — killing annually millions worldwide (Abumalloh et al., 2021, Hernandez-Vargas et al., 2019). During an outbreak, public health agencies aim to limit the spread of pathogen by non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), including the implementation of lockdowns of varying intensity and geographic scope (Ferguson et al., 2020). While an effective vaccine is developed to counter the pathogens and the new variants that could emerge during the pandemic, new waves of infections may still take place, saturating public health capacities (Contreras & Priesemann, 2021).

A crucial aspect for policymakers during pandemics is to set up and remove intervention measures while avoiding the collapse of public health capacities and the economy. From a theoretical control perspective, this problem falls into the classic framework of optimal control (Lewis, Vrabie, & Syrmos, 2012). The major aim of this control strategy is to obtain the best possible performance by using the least control actions, in a kind of cause–effect balance. However, in the case of SIR-type systems based on the seminal work (Kermack & McKendrick, 1927), such a cause–effect separation is not so clear, and evidence can be collected showing that the use of direct and simple control objectives – i.e., to minimize the number of infected individuals at every time or to minimize the final total number of infected – largely produces sub-optimal solutions (Abbasi, 2020, Alamo et al., 2021, Hale et al., 2021, Punzo, 2022, Rypdal et al., 2020).

Several approaches have been proposed to find an optimal-control-based intervention for SIR models. The two main metrics to measure the disease impact are Di Lauro, Kiss, and Miller (2021): the infected peak prevalence, (maximal fraction of infected individuals along time), which is closely related to the health systems capacity, and the epidemic final size, (total final fraction infected). A first result – when minimizing either or – is that optimal solutions can be obtained for the ubiquitous single-interval intervention (Sadeghi, Greene, & Sontag, 2021), i.e., a fixed reduction of the reproduction number (by reducing the infection rate) for a given period of time , with . In Morris, Rossine, Plotkin, and Levin (2021) and Sadeghi et al. (2021) rigorous analyses are made to show how to find the optimal single-interval control action that minimizes . The focus is put on the optimal intervention starting and finishing times and, as stated in Morris et al. (2021), even when theoretical optimal (and near-optimal) interventions are found, they are not resilient to errors in timing. The main problem of this strategy is, however, that it does not account for the other severity index, the . Thus, the total number of infected (and the total number of deceases) is far to be minimized.

Similar approaches (and results) are presented in Bliman and Duprez, 2021, Di Lauro et al., 2021 and Ketcheson (2021), but minimizing the . In these studies, it is found that an optimal intervention also exists, but in a rather unimplementable context. According to Bliman and Duprez (2021), the best policy consists in leaving the system in open-loop until the susceptible/non-infected fraction of individuals approaches the herd immunity threshold and then, at a particular time, implementing the hardest possible intervention. As it can be inferred, this strategy has two main drawbacks: any small error in the timing produces a performance drastically different from the optimal one and, more importantly, the is unacceptably large (since the system is left in open-loop for a long time before acting). The latter point is mentioned in Di Lauro et al. (2021), where it is said that ‘to minimize the total number of infected, the intervention should start close to the peak’. The former point, on the other hand, is demonstrated through simulations in Ketcheson (2021), where a slightly different intervention from the optimal produces severe sub-optimal results. Another (practical) optimal control approach that led to a more realistic scheduling can be found in Köhler et al. (2021), where a model predictive control (MPC) is proposed based on the SIDARTHE (Giordano et al., 2020), and the control objective consists in minimizing the current number of infected individuals (and fatalities) and the time of isolation.

In any case, the common factor in all the recent literature – at the best of the author’s knowledge – is that no conclusive results are shown concerning which is the best policy to simultaneously minimize the , the , and intervention’s severity. In this article, we show that the key point to achieve – or, at least, to arbitrarily approximate – such a goal is the way the optimization problem is posed, by properly separating transient and stationary regimes. Based on a new set-based dynamic analysis of the SIR-type models, a different perspective to formulate the optimal control problem is presented. Instead of considering the control objective of minimizing the or the , the susceptible are directly steered to the (open-loop) herd immunity, since this threshold represents the minimal at steady-state, for any finite-time intervention. Furthermore, since it is independent of the , the is maintained under an upper bound (computed to cope with the health system capacity), while the only quantity to be minimized is the strength and time of the NPI. As demonstrated by several simulation results (related to the spread of COVID-19 in France, during 2020, Bliman and Duprez (2021)), this strategy seems to be general enough to provide a confidence baseline to policymakers in the critical task of decision-making in a pandemic context.

2. Review of control SIR model

The SIR epidemic model (Kermack & McKendrick, 1927) describes the fractions of susceptible and infectious individuals in a population, at time . New infections occur proportional to at a transmission rate , and infectious individuals recover or die at a rate . NPIs reduce the effective transmission rate, , below its value in the absence of intervention (which is considered fixed). By rescaling the time by , the SIR model can be written in non-dimensional form as (Bertozzi, Franco, Mohler, Short, & Sledge, 2020):

where denotes the time-varying reproduction number fulfilling , with , being the starting and ending intervention time ( is assumed to be finite since social intervention has always an end), and the minimal and maximal values for the reproduction number, respectively ( and correspond to non-intervention and maximal intervention, respectively; the case is not considered, since a perfect full lockdown is not possible).

Susceptible and infectious are positive and constrained to be in the set , for all . Particularly, denoting the epidemic outbreak time, it is assumed that , with ; i.e., the fraction of susceptible individuals is smaller than, but close to , and the fraction of infectious is close to zero at .

2.1. No-intervention dynamical analysis

Assume first that , for , which represents the no-intervention (or open-loop) scenario. The solution of (1) for – which was analytically determined in Harko, Lobo, and Mak (2014) – depends on and the initial conditions . is a decreasing function for all , while is decreasing for all if and, if , initially increases, then reaches a global maximum, and finally decreases to zero. In this latter case, the peak of , , is reached at , when , and depends on initial conditions and :

| (2) |

Condition implies that , where is the ‘herd immunity’ (i.e., the value of under which cannot longer increase).

Define now and , which depend on , and . By taking for the solutions proposed in Harko et al. (2014), we obtain . Furthermore, following a similar procedure to Abuin, Anderson, Ferramosca, Hernandez-Vargas, and Gonzalez (2020) for in-host models, is given by

| (3) |

where is the Lambert function (Pakes, 2015). The , which as the , is a function of and , is then given by

| (4) |

The following lemma states the maximum of over .

Lemma 2.1

Consider system (1) with initial conditions , for some , and fixed. Then, for , with , the maximum of occurs at and is given by (particularly, by , if ).

Proof

See the Appendix.

Next, some properties of , for different values of its arguments, are given.

Property 2.1

Consider system (1) with arbitrary initial conditions , for some and . Then: (i) and . (ii) For and fixed , , decreases with , and . This means that the closer is to from above, the closer will be to from below. (iii) For and fixed , , increases with , and . This means that the closer is to from below, the closer will be to , from below. (iv) For any fixed and , decreases with and . (v) . If and , , for any value of (note that for ).

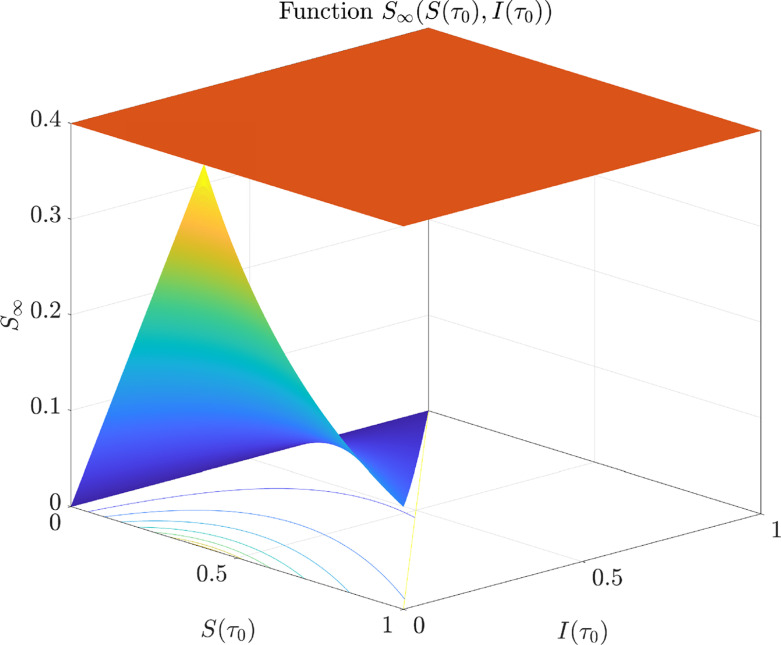

The proof of Property 2.1 is omitted for brevity. Fig. 1 shows how behaves for different initial conditions.

Fig. 1.

Function is bounded from above by (, light red plane). Furthermore, reaches its maximum, given by , at , . (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2.2. Equilibrium characterization and stability

The equilibrium set of system (1), with and initial conditions , is given by . Next, a key theorem concerning the asymptotic stability of a subset of is introduced.

Theorem 1 Asymptotic Stability of —

Consider system (1) with and constrained by . Then, the set

with the herd immunity, is the unique asymptotically stable (AS) set of system (1) , with a domain of attraction given by .

Proof

See the Appendix.

A corollary of Theorem 1, concerning the properties of , is presented next.

Corollary 2.1

Consider system (1) with arbitrary initial conditions , for some . Then: (i) Set is a subset of (for , ), and its size depends on , but not on the initial conditions. (ii) Subsets of are stable but not attractive (i.e., is AS as a whole, but no subset of it is AS). This is particularly true for the state . (iii) If , . Then, and the so called healthy equilibrium with , lies in , and so it is stable, but not attractive (any small makes the system to converge to ) with . (iv) If , set can be divided into two sets, , where is an unstable equilibrium set. (v) Given that any compact set including an AS set is AS, is AS, for any value of . However, if , it contains an unstable set, .

Remark 2.1

It is noteworthy that the key dynamic behaviours described in this section also hold for complex and realistic SIR-type models, as stated in Sadeghi et al. (2021).

3. Epidemic control

NPIs (such as social distancing, isolation measures, mask wearing, etc.) are the typical measures that policymakers implement to control epidemics when vaccination (effectiveness and distribution) is not enough, to lessens the disease transmission rate or, directly, parameter in system (1). Assuming now that , is no longer given by Eq. (2). However, as the final intervention time is finite, Eq. (4) still describes . The following lemma gives an upper bound for , for any .

Lemma 3.1

Consider system (1) with initial conditions , , such that , and . Then, (i) the system converges to with , being the herd immunity corresponding to no intervention and, (ii), the only way to achieve is with an producing and , i.e., the system achieving a quasi steady-state (QSS), at . The cases in which does not approach are: (a) if and , then a second outbreak wave will take place at some time and, finally, the system will converge to (the greater is with respect to , the smaller will be ), (b) if and , then will be close to (the smaller is with respect to , the smaller will be ), and (c) if does not approach zero (i.e., no QSS conditions is reached at ), then no matter which value takes, will be smaller than (the farther is from from above or from below, the smaller will be ).

Proof

See the Appendix.

Lemma 3.1 is a simple but strong result concerning any kind of NPIs, interrupted at a finite time. On one hand, it establishes that the minimal is completely determined by the epidemic itself (the value of ) and, provided that no immunization (by vaccination and/or development of the individual’s immune system) is considered, it cannot be modified by NPIs. On the other hand, Lemma 3.1 establishes that must be reached as a QSS condition (i.e., with ), since otherwise will decrease after the NPI is interrupted at , thus producing .

Example

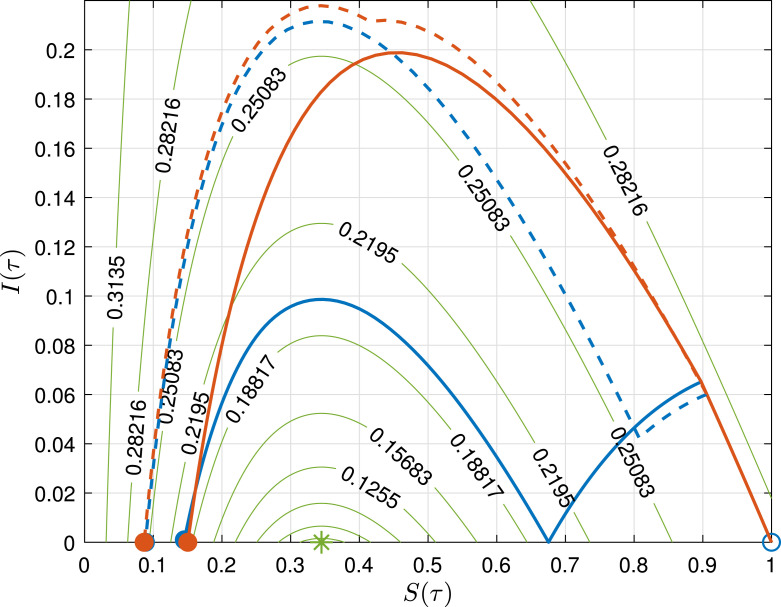

To show the latter properties, consider system (1) with ( days−1 and days−1), , and (COVID-19 circulation in France, March–May, 2020 Bliman & Duprez, 2021). Fig. 2 shows the phase portraits of four different controls . First, long term strategies (solid lines) are implemented (one strong and the other soft) at some time , being and , up to a large time , such that the system reaches a QSS. In the first case (blue line) and and given that is significantly greater than and is still positive, a second wave occurs that steers to a small value (). In the second case (red line), and and since is already under (it cannot grow for ), so is again significantly small (). In a second stage, short terms strategies (dashed lines) are considered (one strong and the other soft). In the first case (blue dashed line), and , which leads to , with significantly small. In the second case (red dashed line), and , which leads, again, to , showing that any control interrupted before the QSS produces a small .

Fig. 2.

Long term (solid line) and short term (dashed line) controls. Initial state: empty circle, : filled circles, Lyapunov function level curves (Appendix): green lines. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.1. Redefining the control objective

Now, the idea is to find an that arbitrarily reduces the while maintaining . To have a first insight into the answer, consider the integral of equation ((1).b), , where is a constant determined by the initial values . Then, given that , with , it follows that . Now, taking the limits for , and recalling that for , it follows that . This equality means that, even when varies over time, only determines the area under the curve of , , but not its peak . In other words, it is possible to minimize the and also keep the under a maximal value imposed by the health system capacity, as long as the condition is respected. This separation of steady-state (minimize the ) and transient (keep the low) objectives can be then exploited to avoid unnecessary competitions between them, which would produces suboptimal solutions, as done in Bliman and Duprez, 2021, Di Lauro et al., 2021, Ketcheson, 2021 and Köhler et al., 2021, Morris et al., 2021. Given that the side effects of the NPIs should be minimized as well, we propose two different control objectives, a primary and a secondary one.

Definition 3.1 Epidemiological and Social/Economic Control Objectives —

Consider system (1) with initial conditions , , such that , and . Consider also that a maximal value for , , is established according to the health system capacity. Then, the epidemiological control objective (ECO) consists in steering to , as , while maintaining , for all . Furthermore, the social/economic control objective (SECO) consists in minimizing the Social Distancing Index , provided that the ECO is achieved.

3.2. Single-interval intervention

We want to find first the simplest that fulfils the ECO of Definition 3.1. A single-interval intervention, , is defined as , for , and , for , where is a fixed value of intervention. Denote by the value of producing , when applied at time , for a large enough . By making , we obtain , which is a decreasing function of . Now, denote by the value of guaranteeing that , for all . By making , we (implicitly) obtain , which is also a decreasing function of . Finally, by merging the latter conditions, it is possible to define a (so-called) goldilocks intervention:

Definition 3.2 Goldilocks Single-interval Intervention —

The goldilocks single-interval intervention is defined by a starting time, , fulfilling condition , and the fixed reproduction number value, .

The goldilocks single-interval intervention allows us to establish the following theorem:

Theorem 2

Consider system (1) with initial conditions , , such that , and . Consider a given . Then, if for and there exists a goldilocks single-interval intervention, it is the only one that arbitrarily approaches the ECO, as .

Proof

See the Appendix.

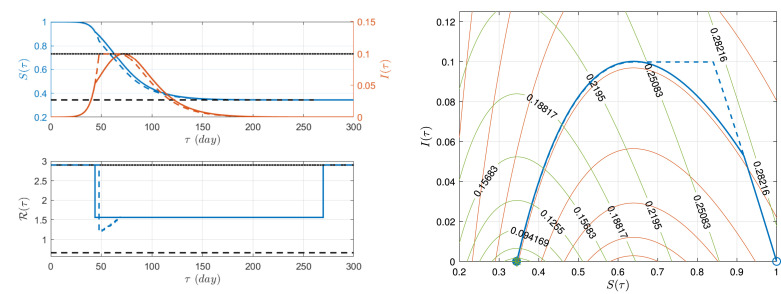

Example

We now resume the example of the previous section to evaluate the goldilocks single-interval intervention. Considering and , we obtain days and . Fig. 3 (left), shows (upper plot, blue solid line), (upper plot, red solid line) and (lower plot, solid line) for a period of time of days. Fig. 3 (right) shows the corresponding phase portrait (blue solid line), and the level curves of Lyapunov functions, (green curves) and (red curves), corresponding to and , respectively. The goldilocks strategy picks the red curve ‘guiding’ the system exactly to , while for . The performance indexes of the strategy are: , , .

Fig. 3.

and time evolution (left), and phase portrait, (right). Goldilocks single-interval (solid line) and ‘wait, maintain, suspend’ interventions (dashed line). System with (black dashed line) and (black dotted–dashed line). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The existence of the goldilocks single-interval intervention depends on and , and is not analysed here, for the sake of brevity. In any case, goldilocks interventions should be understood just as a first-step approach, since they can hardly be applied in realistic cases.

3.3. ‘Wait, maintain, suspend’ strategy

Another strategy that accounts for the ECO of Definition 3.1 and avoids the problem of the existence of a solution for any is the ‘wait, maintain, suspend’ (the intervention) strategy (Morris et al., 2021): , for , , for , and for , where , is the time at which a threshold condition (specified later on) is reached, and is the fixed intervention that, if started at (and applied for a large enough), produces .

Time is considered now as the time at which the open-loop system reaches . At this time, the control action is applied to system (1), making constant for the period . As a result, decreases linearly for (since ). Now, if time is not large enough, may increase for , reaching a peak that overpasses , violating this way the control objective . On the other hand, if is too large, may decrease under , violating the control objective . The next theorem establishes that does exists, such that the ‘wait, maintain, suspend’ strategy fulfils the ECO.

Theorem 3

Consider system (1) with initial conditions , , such that , and . Consider also a given . Then, there exist some such that the ‘wait, maintain, suspend’ strategy produces , for , that arbitrarily approach the ECO, as .

Proof

See the Appendix.

Example

Fig. 3 (left), shows (upper plot, blue dashed line), (upper plot, red dashed line) and (lower plot, dashed line) for a period of time of days, of the ‘wait, maintain, suspend’ intervention. Fig. 3 (right) shows the corresponding phase portrait (blue dashed line). The times are given by , days, and and the ECO is reached, since and for . The performance indexes of this strategy are: , , .

As before, this intervention strategy is rather unrealistic, since the control action varies continuously in the interval and the severity of the intervention is extremely high.

3.4. Optimal control strategy

Now, by taking advantage of the analysis of the previous strategies the following optimal control problem, , is proposed, which accounts also for the SECO:

| (5) |

where is a large enough (possibly infinite) time that covers the whole dynamic of the epidemic and is the set defined in Section 2. Conditions forces to be smaller than the externally imposed maximum at every time , while and , with being an arbitrary small detectable value, forces the system to reach a QSS at , with . The key point of Problem is that the ECO is imposed by constraints while the SECO is achieved by optimality, so the competition between them is avoided. The next theorem establishes that Problem is well-posed and achieves the ECO and the SECO.

Theorem 4

Consider system (1) with initial conditions , , such that , and . Consider also a given . Then, the solution of Problem , denoted as , produces for that arbitrarily approaches the ECO, as , and minimizes the SDI (SECO).

Proof

See the Appendix.

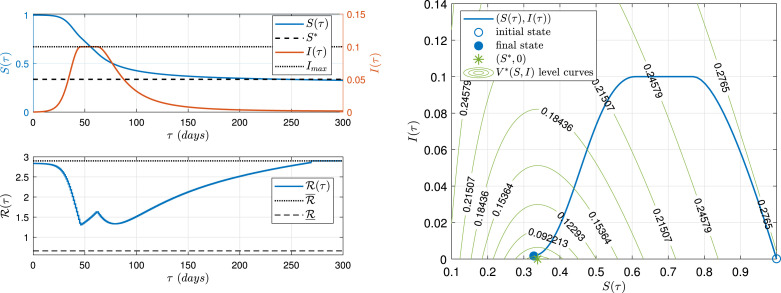

Example

Fig. 4 (left) shows (upper plot, blue line), (upper plot, red line) and (lower plot, blue line), of the optimal intervention , with days. A significant improvement is obtained in terms of the SECO: the SDI drop from in the previous strategies to , while the ECO is (practically) reached. As a particularity, separates the epidemiological objectives over time: first, it handles the (from to days) and, once cannot further increase, it tries to reach , at steady-state, to minimize . The performance indexes are: , , .

Fig. 4.

and time evolution (left), and phase portrait (right). Optimal control . System with and . (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Although not simulated here, it can be shown that any other optimal control problem (i.e., the one minimizing a cost or ) will necessarily produce results far from the optimal one (for any combination of the weights and ), since in these cases the SECO and the ECO compete between them.

Remark 3.1

It is noteworthy that the optimal solution is an important theoretical result to settle down the need of more complex control strategies to account for real epidemics. The main practical limitations are: (i) Problem is in open loop (no state update is considered, as it is done in an MPC); (ii) the model is still a simplistic one; (iii) varies continuously over time while real NPIs are prescribed by taking a few possible values, each one applied for bounded periods; (iv) control actions affect in rather simplistic (linear) forms. Overall, is intended to elucidate some fundamental aspects of the optimization of SIR-type models, and not to formalize an applicable strategy.

4. Conclusions and future work

In this work, a new set-based equilibrium and stability characterization of SIR-type models was made. Based on this characterization, the and the were analysed, and concrete epidemiological objectives involving both indexes were proposed. It is shown that simple non-pharmaceutical intervention strategies exist that (theoretically) accomplish such objectives. If social/economic side effects of the NPIs are also considered – which leads to a non-trivial optimal control problem – a solution can be found that, in addition to achieving the epidemiological objective, minimizes the side effects. Future work will include the consideration of more complex and realistic models and the design of a proper feedback controller able to account for uncertainties/disturbances over short, updated, time horizons. MPC appears to be the right framework to account for such a challenge.

Acknowledgment

Alejandro H. Gonzalez thanks the founding by PIP 2021, KE3, 112-2020010-2555-CO, CONICET.

Esteban Hernandez-Vargas thanks the funding by PAPIIT DGAPA (IA102521) and the Alfons und Getrud Kassel-Stiftung.

Biographies

Juan Sereno was born in Puerto Berrio, Colombia in 1993. He received his B.Sc. degree in Control Engineering (2017) and M.Sc. degree in Industrial Automation Engineering (2021) from the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Medellín. He currently hold a Ph.D. fellowship from The National Council for Scientific and Technical Research in INTEC institute, Santa Fe Argentina. His research focuses on model identification and control theory applied to biomedical systems.

Alejandro Anderson received his a Ph.D. in Engineering – mention: Computational Intelligence, Signals and Systems – in the Faculty of Engineering and Water Sciences at National University of Litoral, Santa Fe, Argentina, and his B.S. in Applied Mathematics from the National University of Litoral — Faculty of Chemical Engineering. Currently he is a Postdoctoral fellow at the Institute of Technological Development for the Chemical Industry (INTEC-UNL-CONICET), Santa Fe, Argentina. His research interests include Model Predictive Control algorithms, stability, robustness, feasibility, set-theory and MPC for switched systems.

Antonio Ferramosca was born in Maglie (LE), Italy, in 1982. He is an Associate Professor at the Department of Management, Information and Production Engineering of the University of Bergamo (Italy). He received his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Computer Science Engineering, both from the University of Pavia (Italy), in 2004 and 2006 respectively, and the Ph.D. degree in Engineering, from the University of Seville (Spain) in 2011. He was a Postdoctoral Fellow and then Research Associate at the Argentine National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET), (from 2012 to 2020). He is member of the IEEE Control System Society and IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. He serves as Associate Editor for the Optimal Control Applications and Methods journal. He is the author and co-author of more than 100 publications. His research interests include Model Predictive Control, control theory for constrained linear and nonlinear systems, and control applications to biological systems.

Esteban A. Hernandez-Vargas obtained his Ph.D. in Mathematics from the Hamilton Institute at the National University of Ireland. For three years, he held a postdoctoral scientist position at the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI) in Braunschweig, Germany. In July 2014, he founded the pioneering research group of Systems Medicine of Infectious Diseases at the HZI. Since March 2017, he and his research group moved to the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies. Since January 2020, he is also Professor at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). He has published more than 100 articles and two books. He is involved on several IEEE and IFAC Conference Organizing Committees.

Alejandro Hernán González is a Titular Professor at the National University of Litoral (UNL) in Argentina and an Independent Researcher at the Argentine National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET). After getting his Ph.D. from the UNL in 2006, he became a Postdoctoral fellow at the Chemical Engineering Department at the “Universidade de São Paulo”, São Paulo-Brazil and, subsequently, at the “Departamento de Ingeniería y Automática de la Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingenieros” of the University of Seville, Seville-Spain. After concluding his Postdoctoral activities, he returned to Argentine to work as a lead researcher in the Dynamical System and Control Group of the Institute of Technological Development for the Chemical Industry (INTEC), which depends on CONICET and UNL, and as Professor at the University, as well as to supervise Ph.D. research projects and students. He is the author and co-author of more than 100 publications and serves as Associate Editor for the Optimal Control Applications and Methods journal. His research interests include Dynamical Systems under Constraints, Optimal and Model Predictive Control, and Biomedical/Biological Application, with emphasis on hybrid systems and stability analysis.

Footnotes

The material in this paper was not presented at any conference. This paper was recommended for publication in revised form by Associate Editor Giulia Giordano under the direction of Editor Thomas Parisini.

Appendix. Technical proofs

Proof of Lemma 2.1

Denote , and , and define , where , with , is a set of initial conditions. Define also the maximizer initial conditions as .

According to (3), , with . Given that is an increasing (injective) function of and is fixed, then achieves its maximum over at the same values of and as (next it is shown that for all ) and . Denote the maximum of as , while the maximizing variables are and . Given that the maximum of occurs at the minimal values of , let us consider, for simplicity, that , in such a way that (we ignore the conditions and , but it is easy to see that no maximum is achieved at the boundaries of these constraints). Then, and . Optimality conditions can be written as , where is a Lagrange multiplier. Then, , , which implies that and . Since , the first equality implies that , or (since must be in ). This way, the second equality reads , which is true for any value of and . Since decrease with , .

The maximum value of is then given by , which reads . If , then , and so . On the other hand, if , then and . Particularly, , if , and , if , which concludes the proof. □

Proof of Theorem 1

It will be shown that is the smallest attractive equilibrium set and the largest locally stable equilibrium set in , which implies it is the unique symptotically stable (AS) of system (1), with a domain of attraction given by .

Attractivity: Consider Eq. (3). is an increasing function (it goes from at to at ), so it reaches its minimum at . reaches its maximum when , independently of the values of and (see Lemmas 2.1), in which case it is . Then, is bounded from above by , which means that is an upper bound for . Therefore, , which shows the attractivity of . To show that is the smallest attractive set in , consider a state and an arbitrary small ball of radius , w.r.t. , around it, . Pick two arbitrary initial states and in , such that . These two states converge, according to Eq. (3), to and , respectively, with . Given that function is monotone (injective) in and , and is monotone (injective) in , then . Therefore, neither single states nor subsets of are attractive in , which shows that is the smallest attractive set in .

Localstability: Let us consider a particular equilibrium point , with (i.e., ). Then, a Lyapunov function candidate is given by , which is continuous in , is positive definite for all non-negative and, furthermore, . Function evaluated at the solutions of system (1) reads for and , which means that, independently of , for . Then, for any single , and , for all . So is null for any (note that it is not only null for but for any , so AS of single states and subsets of cannot be followed). On the other hand, for , function is negative, zero or positive, depending on if the parameter is smaller, equal or greater than , respectively, and this holds for all and . So, every is locally stable, which means that the whole set is locally stable. Finally, by following similar steps, it can be shown that is not stable, which implies that is also the largest locally stable set in , which completes the proof. □

Proof of Lemma 3.1

The proof of (i) follows from Lemma 2.1, by replacing by , and the fact that the final intervention time, , is finite. The proof of (ii) follows from Lemma 2.1, the stability analysis made in the proof of Theorem 1, applied at (Corollary 2.1,(ii)), and Property 2.1, by replacing by . □

Proof of Theorem 2

Consider that, for and coming from the ECO, there exists some for which . Then, by definition of , it follows that , meaning that for all . Furthermore, by definition of it follows that, for a large enough , arbitrarily approaches while approaches . Then, by the stability results at (Corollary 2.1,(ii)), it follows that states arbitrarily close to (from above), produce states arbitrarily close to (from below), for . Particularly, . □

Proof of Theorem 3

By hypothesis starts growing from the small value , at time , reaching for some . The control action (which is in because ) applied to system (1) for the period produces , which means that remains constant. Furthermore, decreases linearly for (since ). Now, time can be selected large enough for not to increases for , and small enough for not to decreases below , for . That is, the value of must be smaller than the herd immunity value corresponding to system (1) with , but larger than the herd immunity value corresponding to . This condition can be fulfilled if , or, the same , recalling that , for and . Any such that , produces and , which completes the proof. □

Proof of Theorem 4

Problem is feasible, since the ‘wait, maintain, suspend’ strategy of Section 3.3 is a particular (non optimal) solution. Then, the optimal solution, , will produce, in general, a smaller cost (and so, a smaller SDI) than any feasible one, by taking advantages of the degrees of freedom of the problem. □

References

- Abbasi K. Behavioural fatigue: a flawed idea central to a flawed pandemic response. BMJ. 2020;m3093 [Google Scholar]

- Abuin P., Anderson A., Ferramosca A., Hernandez-Vargas E.A., Gonzalez A.H. Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 dynamics in the host. Annual Reviews in Control. 2020;50:457–468. doi: 10.1016/j.arcontrol.2020.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abumalloh R.A., Asadi S., Nilashi M., Minaei-Bidgoli B., Nayer F.K., Samad S., et al. The impact of coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) on education: The role of virtual and remote laboratories in education. Technology in Society. 2021;67 doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alamo T., Millán P., Reina D.G., Preciado V.M., Giordano G. Challenges and future directions in pandemic control. IEEE Control Systems Letters. 2021;6:722–727. [Google Scholar]

- Bertozzi A.L., Franco E., Mohler G., Short M.B., Sledge D. The challenges of modeling and forecasting the spread of COVID-19. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2020;117(29):16732–16738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2006520117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliman P.A., Duprez M. How best can finite-time social distancing reduce epidemic final size? Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2021;511 doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2020.110557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras S., Priesemann V. Risking further COVID-19 waves despite vaccination. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2021;21(6):745–746. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00167-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lauro F., Kiss I.Z., Miller J.C. Optimal timing of one-shot interventions for epidemic control. PLoS Computational Biology. 2021;17(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson N.M., Laydon D., Nedjati-Gilani G., Imai N., Ainslie K., Baguelin M., et al. Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand. imperial college COVID-19 response team. Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team. 2020;20(10.25561):77482. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano G., Blanchini F., Bruno R., Colaneri P., Di Filippo A., Di Matteo A., et al. Modelling the COVID-19 epidemic and implementation of population-wide interventions in Italy. Nature Medicine. 2020;26(6):855–860. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0883-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale T., Angrist N., Hale A.J., Kira B., Majumdar S., Petherick A., et al. Government responses and COVID-19 deaths: Global evidence across multiple pandemic waves. PLoS One. 2021;16(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harko T., Lobo F.S., Mak M.K. Exact analytical solutions of the susceptible-infected-recovered (SIR) epidemic model and of the SIR model with equal death and birth rates. Applied Mathematics and Computation. 2014;236:184–194. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Vargas E.A., Alanis A.Y., Tetteh J. A new view of multiscale stochastic impulsive systems for modeling and control of epidemics. Annual Reviews in Control. 2019;48:242–249. [Google Scholar]

- Kermack W.O., McKendrick A.G. A contribution to the mathematical theory of epidemics. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of A Mathematical and Physical Character. 1927;115(772):700–721. [Google Scholar]

- Ketcheson D.I. Optimal control of an SIR epidemic through finite-time non-pharmaceutical intervention. Journal of Mathematical Biology. 2021;83(1):1–21. doi: 10.1007/s00285-021-01628-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler J., Schwenkel L., Koch A., Berberich J., Pauli P., Allgöwer F. Robust and optimal predictive control of the COVID-19 outbreak. Annual Reviews in Control. 2021;51:525–539. doi: 10.1016/j.arcontrol.2020.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis F.L., Vrabie D., Syrmos V.L. John Wiley & Sons; 2012. Optimal control. [Google Scholar]

- Morris D.H., Rossine F.W., Plotkin J.B., Levin S.A. Optimal, near-optimal, and robust epidemic control. Communications Physics. 2021;4(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pakes A.G. Lambert’s W meets Kermack–McKendrick epidemics. IMA Journal of Applied Mathematics. 2015;80(5):1368–1386. [Google Scholar]

- Punzo G. An SIS network model with flow driven infection rates. Automatica. 2022;137 [Google Scholar]

- Rypdal K., Bianchi F.M., Rypdal M. Intervention fatigue is the primary cause of strong secondary waves in the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(24):9592. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi M., Greene J.M., Sontag E.D. Universal features of epidemic models under social distancing guidelines. Annual Reviews in Control. 2021;51:426–440. doi: 10.1016/j.arcontrol.2021.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]