Abstract

The Neisseria polysaccharea gene encoding amylosucrase was subcloned and expressed in Escherichia coli. Sequencing revealed that the deduced amino acid sequence differs significantly from that previously published. Comparison of the sequence with that of enzymes of the α-amylase family predicted a (β/α)8-barrel domain. Six of the eight highly conserved regions in amylolytic enzymes are present in amylosucrase. Among them, four constitute the active site in α-amylases. These sites were also conserved in the sequence of glucosyltransferases and dextransucrases. Nevertheless, the evolutionary tree does not show strong homology between them. The amylosucrase was purified by affinity chromatography between fusion protein glutathione S-transferase–amylosucrase and glutathione-Sepharose 4B. The pure enzyme linearly elongated some branched chains of glycogen, to an average degree of polymerization of 75.

Amylosucrase is a glucosyltransferase (EC 2.4.1.4) which catalyzes the transfer of the d-glucopyranosyl unit from sucrose onto a glucan primer and synthesizes an insoluble α-glucan, without using α-d-glucosylnucleoside-di-P as substrate (19–21, 28, 29, 42), unlike glycogen synthase. Indeed, the bacterial synthesis of glycogen is frequently based on the transfer of glucose from adenosine-5′-di-P-glucose (ADPG) onto an α-glucan chain, the ADPG itself being formed by ADPG synthetase (ADPG-α-d-glucose-1-P-adenyltransferase) from α-d-glucose-1-P (32).

Amylosucrase was first discovered in cultures of Neisseria perflava (7). In 1974, Neisseria polysaccharea was isolated from the throats of healthy children in Europe and Africa (34). This nonpathogenic strain was shown to possess an extracellular amylosucrase that uses sucrose to produce a linear polymer composed of α-(1→4)glucopyranosyl residues having strong similarities with amylose (5, 33, 35). More recently, Büttcher et al. (5) cloned and sequenced the gene coding for amylosucrase from N. polysaccharea. They report that the deduced amino acid sequence of the enzyme has homology with the α-amylase class of enzymes. However, regions known to be essential for the catalytic activity of α-amylases were scarcely found in the amylosucrase sequence reported.

This study describes the subcloning and sequencing of the gene encoding amylosucrase from N. polysaccharea isolated by Remaud-Simeon et al. (33). The deduced amino acid sequence differs significantly from that published by Büttcher et al. (5). This allowed us to compare it more specifically with enzymes from the α-amylase family. The recombinant enzyme was then overexpressed by Escherichia coli, purified, and characterized.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

N. polysaccharea ATCC 43768 was used as the source of chromosomal DNA. E. coli C-600 was used as the cloning host for direct expression screening of the gene library. E. coli DH1 was used as the host for the pUC19 and ptrc99a vectors; strain BL21 was used as the host for the expression plasmid pGEX-6-P-3.

Vectors.

Phage λEMBL3A was used to construct the genomic library. pUC19 (New England Biolabs) and ptrc99a (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) were used for subcloning and overexpression, respectively. pGEX-6-P-3 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) was used for expression of amylosucrase fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST-AS).

Cloning of amylosucrase.

The gene library was constructed by partially digesting DNA from N. polysaccharea with Sau3A and cloning the fragments into BamHI sites of λEMBL3A as previously described (33). The recombinant E. coli C-600 bacteria in YT medium soft agar were plated on top of M9 medium containing nutritional supplements (MgSO4, CaCl2, thiamine, threonine, and leucine) and 0.7% sucrose. After 6 h of growth at 37°C, plaques appeared in the soft agar (37). When sucrase activity was expressed, the enzyme catalyzed the release of fructose and/or glucose which were metabolized by the bacteria and stimulated growth around the plaque, forming a halo. As sucrose cannot be utilized by E. coli C-600, the halo appeared only around the plaque where sucrase activity was expressed. Recombinant phage DNA purification was carried out as described by Sambrook et al. (37). A 15-kb fragment was purified (33) and digested with KpnI and HindIII to isolate a 6-kb fragment that was inserted between the KpnI and HindIII sites of pUC19. The plasmid obtained was named AS/pUC19. The fragment was shown to encode amylosucrase. Activity of the subclone was detected as described below.

Sequencing.

The recombinant plasmid AS/pUC19 was automatically sequenced over the entire length of the insert by Genome Express (Grenoble, France), using the method of Sanger et al. (38). The sequencing reaction was performed by PCR amplification in a final volume of 20 μl, using 100 ng of PCR products, 5 pmol of primer, and 9.5 μl of BigDyeTerminators premix, in accordance with the Applied Biosystems protocol. After heating of the mixture to 94°C for 2 min, the reaction was cycled as follows: 25 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 4 min at 60°C (Perkin-Elmer 9600 thermal cycler). Removal of excess of BigDyeTerminators was performed by using Quick Spin columns (Boehringer Mannheim). The samples were dried in a vacuum centrifuge and dissolved with 2 μl of deionized formamide-EDTA (pH 8.0) (5/1). The samples were loaded onto an Applied Biosystems 373A sequencer and run for 12 h on a 4.5% denaturing acrylamide gel. Each reaction was repeated three times to verify the sequence obtained.

The nucleotide sequence data were screened by using the ORF (open reading frame) Finder program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.orfig) to locate the amylosucrase gene. Homology searches with proteins in GenBank were carried out with BEAUTY (http://dot.imgen.bcm.tmc.edu:9331/seq-search/protein-search.html) and Pfam (http://genome.wustl.edu/pfam/cgi-bin/hmm-page.cgi). Restriction sites of the amylosucrase sequence were determined with PCGene; the theoretical molecular weight and pI were determined by using SWISS-2-D-PAGE (http://expasy.hcuge.ch/ch2d/pi-tool.html). The evolutionary tree was constructed with ClustalW (http://ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/).

Enzyme extraction methods.

Cultured recombinant bacteria were centrifuged (8,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C), and the culture supernatant was stored at 4°C for assay. Depending on the intended use the bacterial pellet underwent one of two treatments.

(i) Osmotic shock.

To extract enzyme secreted into the periplasmic space, the pellet was washed with 0.01 M Tris-HCl–0.03 M NaCl (pH 7.3) and then centrifuged (5,000 × g, 5 min, 4°C). It was resuspended, concentrated to 1/20 the initial culture volume with hypertonic solution (0.03 M Tris, 20% [wt/vol] methyl-α-d-glucopyranoside, 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.3]), gently mixed for 10 min at room temperature, and then centrifuged (5,000 × g, 5 min, 4°C); cells were resuspended and concentrated to 1/20 the initial culture volume with hypotonic solution (water). Then the pellet was centrifuged again (7,500 × g, 10 min, 4°C), and the supernatant was stored at 4°C.

(ii) Sonication.

To extract the intracellular enzyme, the bacterial pellet was resuspended and concentrated at an optical density at 600 nm of 80 in 50 mM maleate buffer (pH 6.4) or, for strain BL21, in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4 [pH 7.3]). After sonication, 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 was added to the extract. After 30 min at 4°C and centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C), the supernatant was stored at 4°C.

Amylosucrase assay.

The amylosucrase assay was carried out at 30°C in 50 mM maleate buffer (pH 6.4) supplemented with sucrose (50 g/liter) and glycogen (0.1 g/liter) (G-8751; Sigma Chemical Co.) as a primer. Activities of the GST-AS amylosucrase fusion protein and the purification fractions were measured at 30°C in sample buffer (pH 7.0) in the presence of sucrose (50 g/liter) and glycogen (0.1 g/liter).

One unit of amylosucrase corresponds to the amount of enzyme that catalyzes the production of 1 μmol of fructose per min in the assay conditions. The concentration of fructose was measured by the dinitrosalicylic acid method, using fructose as a standard (39).

The production of fructose is related to the production of an α-glucan that precipitates in the tube. A slight amount of glucose, corresponding to a sucrose hydrolytic activity of amylosucrase, was produced. However, it always constituted less than 12% of total reducing sugars in assay conditions and thus was neglected. Protein content was determined by the Bradford and micro-Bradford methods, using bovine serum albumin as the standard (4).

Overexpression of amylosucrase.

For high-level expression, the gene encoding amylosucrase was first amplified by PCR and cloned into the expression vector ptrc99a, to obtain plasmid AS/ptrc99a. PCR was carried out with DNA from recombinant λEMBL3A with a 15-kb insert fragment as the matrix. The PCR primer oligonucleotides were synthesized by Isoprim (Toulouse, France).

The direct primer 5′-AATCGGAGCAGGCACCATGGTGACCCCCACGCAG-3′ introduces the NcoI restriction site (boldface) around the authentic ATG codon and is located between bases 120 and 153 of the amylosucrase gene nucleotide sequence. In the reverse primer 5′-ACGGCATTTGGGAAGCTTGCGTCAGGCGATTTCGAGC-3′, located between bases 2031 and 2067, a HindIII site (boldface) was created to allow cloning. The fragment obtained was ligated into ptrc99a digested with NcoI and HindIII. The underlined bases correspond to the mutations generated by PCR to introduce the restriction sites.

Purification of amylosucrase.

Affinity chromatography between the GST-AS fusion protein and the glutathione-Sepharose 4B support was performed to purify the amylosucrase.

(i) Cloning of the GST-AS fusion protein.

To clone GST-AS, we used the expression vector pGEX-6-P-3, which includes the GST protein just downstream of the strong promoter Ptac and upstream of the cloning site. Cloning was carried out between the EcoRI and NotI restriction sites. The amylosucrase gene was amplified by PCR from AS/pUC19, using the direct primer 5′-CAGCAAGTCGGTTTGAATTCACAGTACCTCAAAACACGC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-TCCGGTTCGGCGCAGCGGCCGCCTGAAACGGTTCAGA-3′, including the EcoRI and NotI restriction sites, respectively. These primers are localized between bases 151 and 189 and bases 2067 and 2103, respectively, of the amylosucrase gene nucleotide sequence. PCR was carried out in the presence of 10% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide so as to avoid nonspecific hybridization of the primers and thus the amplification of interfering fragments. The PCR fragment was cloned into the EcoRI and NotI sites of the vector pGEX-6-P-3. This cloning results in a mutated amylosucrase in positions 11 and 12 (I→N and L→S), with deletions of amino acids 1 to 10, corresponding to the first part of the putative signal sequence described by Büttcher et al. (5). The plasmid obtained was used to transform a protease-negative strain E. coli BL21.

(ii) Purification.

Purification was carried out at 4°C except during the elution step. A 2-ml column of glutathione-Sepharose 4B (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) was equilibrated with 30 ml of PBS and then with 6 ml of PBS–1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. A volume of 1.5 ml of enzyme extract from the sonication supernatant (corresponding to 12.3 mg of protein and 12.2 U of amylosucrase activity) was injected into the column, which was then washed with 70 ml of PBS. The fusion protein was eluted with 2 ml of elution buffer (20 mM reduced glutathione–G-4251 [Sigma], 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 120 mM NaCl) after 10 min of contact at room temperature. The procedure was carried out three times. The column was regenerated to remove residual noneluted fusion proteins by using 30 ml of PBS–3 M NaCl and then 10 ml of 70% (vol/vol) ethanol and was then equilibrated with 30 ml of PreScission buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.0], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol). The fraction containing the eluted fusion protein was dialyzed against PreScission buffer at 4°C overnight. The fusion protein was then subjected to proteolysis at 4°C for 4 h by adding 2 U of PreScission protease (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) per 100 μg of fusion protein. The mixture was then injected into the glutathione-Sepharose 4B column, the purified amylosucrase being eluted in the PreScission buffer. The column was eluted and regenerated as described above and then equilibrated and stored in PBS at 4°C.

Electrophoresis.

Electrophoresis was carried out with the PHAST system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Under denaturing conditions, the sample was diluted with denaturing buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2.5% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 5% [wt/vol] β-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue) and heated to 90°C for 1 min before being placed on a polyacrylamide PhastGel gradient 8-25 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The buffer system in PhastGel SDS buffer strips was 0.2 M tricine (trailing ion)–0.2 M Tris–0.55% SDS (pH 8.1).

Under native conditions, the front-line marker was added to the sample (10 μg of bromophenol blue per ml) and placed on a polyacrylamide PhastGel gradient 8-25. The buffer system in PhastGel native buffer strips was 0.88 M l-alanine–0.25 M Tris (pH 8.8).

The isoelectric point of amylosucrase was determined by using PhastGel IEF 3-9 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), which is a homogeneous polyacrylamide gel containing Pharmalyte carrier ampholytes. For these three types of electrophoresis, the proteins were stained with 0.5% (wt/vol) AgNO3.

Production and characterization of the polymer synthesized.

The synthesis reaction was performed at 30°C for 24 h in PreScission buffer, supplemented with sucrose (50 g/liter) and oyster glycogen (1 g/liter) with 19.5 mg of pure amylosucrase per liter. The reaction was stopped by adding 60% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide (which solubilized the water-insoluble polymer) and heating to 100°C for 1 h. The polymer was then precipitated with ethanol at 4°C and dried by solvent exchange (ethanol-acetone).

(i) β-Amylolysis and deramification experiments.

Glucans (0.8%) were solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide. After dilution in 50 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer (pH 7.0) to a final concentration of 2 mg/ml, 10 μl of β-amylase from Bacillus sp. (2000 U/mg; Megazyme) was added, and the reaction was run for 3 h at 40°C. The determination of reducing ends was performed as described by Nelson (27).

Deramification was performed with isomylase from Hayashibara. Solubilized glucans were diluted in 50 mM citrate buffer (pH 3.8) to a final concentration of 2 mg/ml; 5 μl of isoamylase from Pseudomonas sp. (5,900 U/mg) was added, and the reaction was performed at 37°C for 48 h.

Concentrations were checked by the sulfuric acid-orcinol colorimetric method. After total digestion by glucoamylase (Megazyme), glucose was measured by the glucose-oxidase/peroxidase method (31).

(ii) Sample preparation for high-performance size-exclusion chromatography (HPSEC)-MALLS.

To prepare α-glucan solutions in 0.1 M KOH, amylose powder was dispersed in 1 M KOH, gently stirred overnight at 4°C, and then diluted to 0.1 M KOH. For water solutions, α-glucan powder was dispersed by boiling for 5 to 30 min, until the aqueous buffer used as the eluent was clarified. α-Glucan solutions were then cooled to room temperature.

Prior to the injection of 200 μl, all samples were filtered directly into the autosampler cell through Durapore HV (0.45-μm-pore-size) membranes without affecting the α-glucan concentrations, which were in the range 1 to 5 g/liter. Concentrations were checked before injection by the sulfuric acid-orcinol colorimetric method (31); α-glucan sample recovery calculated from the area of the refractive index profile was always greater than 95%.

(iii) HPSEC.

The HPSEC system was used as described previously (3). Dual detection of solutes was carried out with a detector Dawn DSP-F MALLS (Wyatt Technology Corporation, Santa Barbara, Calif.) and a differential refractive index detector (Erma ERC-7510) in series.

The size exclusion chromatography (SEC) system comprised a precolumn and three Shodex OHpak KB-800 series columns (300 by 8 mm; Showa Denko K.K., Tokyo, Japan), connected in the order KB-806–KB-805–KB-804. The columns were maintained at 30°C via Crococil temperature control (Cluzeau, Bordeaux, France). The eluent was water taken from a Milli-RO-6-Plus and Milli-Q-Plus water purification system (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) to which 0.02% (wt/wt) sodium azide was added. It was carefully degassed and filtered through Durapore GV (0.22-μm-pore-size) membranes (Millipore) before use. The mobile phase (flow rate of 1 ml/min) was filtered on-line before the injector through Durapore GV (0.22-μm pore-size) and VV (0.1-μm-pore-size) membranes. The sample (200 μl) was injected into the HPSEC system.

(iv) Data analysis.

For each sampling time of the elution pattern corresponding to one elution volume (Vi), a concentration (ci) is calculated from the differential refractive index response. Following this determination, measurement of the light scattered by the 15 Dawn-F photodiodes allows the determination of molecular weight (Mi) and radius of gyration (Ri = <rg2 >i1/2) of α-glucans by ASTRA version 1.4, based on the equation

|

where K is the optical constant, Rq is the excess Rayleigh ratio of the solute, λ is the wavelength (632.8 nm) of the incident laser beam, and ci is calculated from the differential refractive index response (dn/dc being the refractive index increment with a value of 0.146 ml/g for α-glucans) (30).

Mi and Ri are obtained from the y intercept to zero angle and from the slope of the expected straight line, respectively. The lowest errors for determined Mi and radius of gyration Ri = <rg2 >i1/2) values were obtained by the Debye method; only the eight lowest angles were used (from 22° to 90°) with a second-order polynomial fit.

Weight average molar mass ( w) is then calculated as

w) is then calculated as

|

The root-mean-square z-average radius of gyration R̄G (R̄G = <r̄g2 >z1/2) is

|

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The amylosucrase gene sequence has been submitted to the EMBL nucleotide sequence database and assigned accession no. AJ011781.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Sequencing of the N. polysaccharea gene coding for amylosucrase.

The sonicated cell extracts of E. coli DH1 clones transformed by plasmid AS/pUC19 tested positive for amylosucrase activity in the amylosucrase assay. Plasmid AS/pUC19 was sequenced on the full length of the 6-kb insert. An ORF search in the six possible reading frames revealed the presence of seven ORFs of 500 nucleotides (nt) or more. The deduced amino acid sequences from the seven ORFs were subjected to protein sequence comparison using Pfam. Only one of the seven ORFs belongs to a known enzyme family; it corresponds to the amylosucrase gene. This ORF consists of 1,911 nucleotides nt encoding a protein of 636 amino acids. Also, no ORF of more than 500 bases was present in the same reading frame as that of the gene encoding amylosucrase. No protein capable of interfering in the enzymatic reaction catalyzed by amylosucrase is present near it. Therefore, the amylosucrase from N. polysaccharea is not expressed via a multigenic system.

The previously identified (5) regulatory elements promoting gene expression are present in the amylosucrase gene sequence. The consensus sequences of bacterial promoters are located between nt 26 and 33 and between nt 50 and 55 of the amylosucrase gene nucleotide sequence; the putative Shine-Dalgarno sequence is located between nt 126 and 129.

The coding sequence described in this report is 98.6% identical to a sequence previously published (5) but differs in several regions. Its length is 1,911 bp instead of the 1,842 for the sequence previously published, the termination codon appearing 53 bp after that of the cited sequence. The deduced amino acid sequence exhibits only 76% identity with the previously published sequence. In particular, comparison of the two sequences shows that four regions (A-183 to W-202, R-274 to Q-312, S-507 to T-537, and R-579 to A-636) are totally different. For this reason, the sequence was determined with an automatic sequencer; it was checked three times, using different primers, to confirm the amylosucrase gene sequence reported here.

In addition, the EcoNI restriction profile of the amylosucrase gene cloned into the vector ptrc99a revealed errors in the previously published sequence (5), as the authors have now confirmed (15a). In the nucleotide sequence reported here, two EcoNI sites can be identified, digestion being effective after bases 1066 and 1993 and resulting in two DNA fragments of 927 and 5,109 bp. In the previously published sequence, only the second site was reported, because of the omissions of C-1067 and G-1072.

Sequence comparison of amylosucrase with related enzymes.

A characteristic (β/α)8-barrel fold was predicted in the protein structure by using Pfam. In addition, the eight-stranded β/α barrel is interrupted by the presence of a separate folding module (70 amino acids) homologous to a calcium-binding domain, protruding between β strand 3 and helix 3 (17). This domain is included in the part of the sequence that could correspond to domain B of amylolytic enzymes (G-184 to F-298 [amylosucrase numbering]) (11). The protein may also contain a C-terminal β barrel (17). These results suggest that amylosucrase is a member of the α-amylase family.

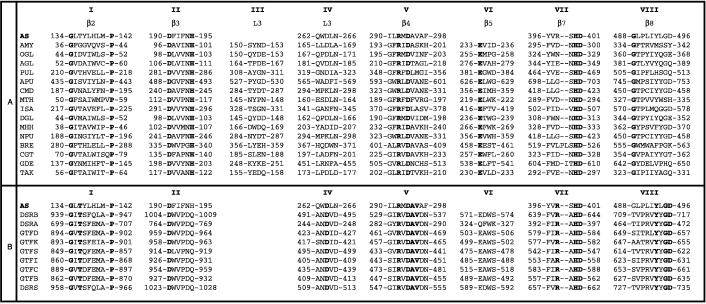

Sequence comparisons revealed that the sequence of amylosucrase contains six of the eight highly conserved regions in amylolytic enzymes (10). The multiple alignment corresponding to these sites is presented in Fig. 1A. Sites II, V, VI, and VII are the four best-conserved regions in the active site of the α-amylase family (40). The invariant amino acid residues are all conserved in the amylosucrase sequence, except E-230 (numbering for α-amylase from Aspergillus oryzae). Indeed, sites III and VI are not sufficiently similar to the amylosucrase sequence to be localized.

FIG. 1.

Conserved sequence stretches (I to VIII) in amylosucrase, in the α-amylase superfamily (A), and in glucosyltransferases (B) (12). The second line denotes the elements of secondary structure, as determined for pig pancreatic α-amylase. Enzymes are numbered from the N-terminal end; invariable residues are in boldface. (A) AS, amylosucrase (N. polysaccharea); AMY, α-amylase (pig pancreas); OGL, oligo-1,6-glucosidase (Bacillus cereus); AGL, α-glucosidase (Saccharomyces cerevisiae); PUL, pullulanase (B. stearothermophilus); APU, amylopullulanase (Clostridium thermohydrosulfuricum); CMD, cyclomaltodextrinase (B. sphaericus); MTH, maltotetraohydrolase (Pseudomonas saccharophila); ISA, isoamylase (P. amyloderamosa); DGL, dextran-glucosidase (Streptococcus mutans); MHH, maltohexaohydrolase (Bacillus sp. strain 707); NPU, neopullulanase (B. stearothermophilus); BRE, branching enzyme (E. coli); CGT, cyclodextrin-glycosyltransferase (B. circulans); GDE, glycogen-debranching enzyme (human muscle); TAK, α-amylase (A. oryzae). (B) AS, amylosucrase (N. polysaccharea); DSRB (Leuconostoc mesenteroides NRRL B-1299); DSRA (L. mesenteroides NRRL B-1299); GTFD (S. mutans GS5); GTFK (S. salivarius ATCC 25975); GTFS (S. downei Mfe 28); GFTI (S. sobrinus OMZ176 serotype D); GTFC (S. mutans GS5); GTFB (S. mutans GS5); DSRS (L. mesenteroides NRRL B-512F).

Some of the residues in the consensus sequences have been determined to play a role in amylolytic activity. Particularly, D-294 and D-401, corresponding to D-206 and D-297 in α-amylase from A. oryzae, are two of the crucial invariant carboxylic acid residues from the catalytic triad involved in bond cleavage, the third being E-230 (A. oryzae α-amylase numbering) (8, 15, 16, 24, 25, 40, 41).

Two other invariant residues (H-122 and H-296 [A. oryzae α-amylase numbering]) are constituents of the active site of α-amylases (9, 40). They correspond to H-195 and H-400 in amylosucrase and could be among the three histidine residues involved in stabilization of the substrate-binding transition state in CGTase of the alkalophilic Bacillus sp. 1011 (26) and in α-amylase from A. oryzae (12, 22).

From these studies, it can be concluded that amylosucrase is a member of the α-amylase family and that some of the invariant residues are probably involved in amylosucrase activity. The catalytic mechanism of this enzyme may therefore resemble that of α-amylases, especially for the formation of the glucosyl enzyme intermediate.

In addition, these results support the recent studies predicting that glucosyltransferases are also members of the α-amylase family (6, 18), possess a circularly permuted (β/α)8 barrel (18), and also share features for glucosidic cleavage with α-amylases. Amylosucrase being itself a glucosyltransferase acting on sucrose, the sequences of dextransucrases and glucosyltransferases were studied to localize conserved sites (Fig. 1B). The catalytic triad of α-amylases is also conserved in glucosyltransferases and has been shown to be crucial for activity (6, 14). Indeed, residue D-451 of glucosyltransferase GTFB from Streptococcus mutans GS5, corresponding to D-294 in amylosucrase, was found to be involved in the establishment of the glucosyl enzyme intermediate and has been shown to be necessary for transferase activity (14). In dextransucrase from Leuconostoc mesenteroides, the corresponding residue was also shown to be part of sucrose-binding site (23). In addition, residue D-401 of amylosucrase corresponds to D-547 of glucosyltransferase GTFS from Streptococcus downei Mfe 28, which carries a carboxylic group that could be implicated in the catalytic mechanism (18). Further enzyme crystallization and X-ray diffraction studies will be crucial for understanding the catalytic mechanism of amylosucrase and the features it has in common with both amylolytic enzymes and glucosyltransferases.

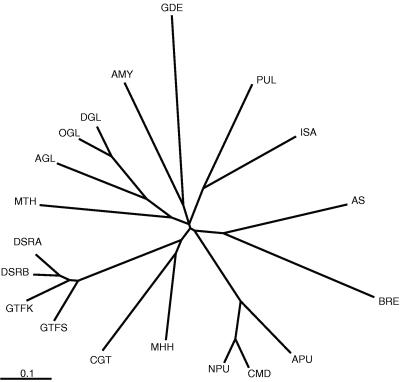

An unrooted evolutionary tree was calculated on the conserved sites I, II, IV, V, VII, and VIII of amylolytic enzymes, glucosyltransferases, and dextransucrases (Fig. 2). Amylosucrase is situated on one of the longest branches of the tree, indicating that it does not resemble any of the others. Surprisingly, it does not belong to the dextransucrase and glucosyltransferase group, even though it is a glucosyltransferase.

FIG. 2.

Evolutionary tree of amylolytic enzymes, glucosyltransferases, and amylosucrase, based on stretches I, II, IV, V, VII, and VIII. Abbreviations are given in the legend to Fig. 1; branch lengths are proportional to the sequence divergency. A similar tree can be found in reference 12.

Overexpression of the amylosucrase gene.

As the amylosucrase gene was previously shown to contain a putative signal peptide sequence (5), the recombinant enzyme was tested for extracellular, periplasmic, or intracellular activity. E. coli DH1 transformation with plasmid AS/ptrc99a and induction by 2.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, allowed determination of the initial activity in the enzyme extract: 30 U/liter of culture after osmotic shock, 3 U/liter of culture in the culture supernatant, and 658 U/liter of culture with sonication; 95% of the enzyme is intracellular, which confirms that E. coli cannot recognize or process the previously described putative signal peptide (5).

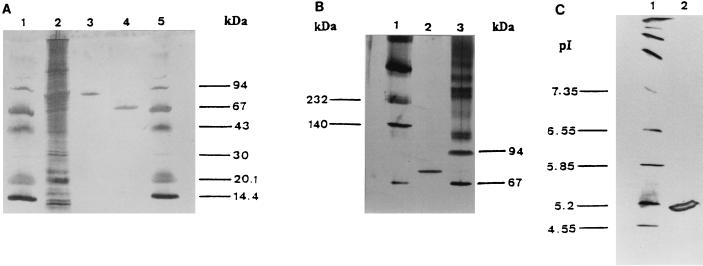

Purification of amylosucrase obtained from the GST-AS fusion protein.

The yields obtained at various steps of the purification process and specific activities are presented in Table 1. The glutathione-eluted sample consists of pure fusion protein (see Fig. 3A). The purification process enabled a pure amylosucrase fraction to be obtained, as shown by the electrophoresis revealed with silver nitrate (Fig. 3A), with a specific activity of 9,565 U/g. The total yield of the purification was 38%; this value would have been increased to 43% if the fusion proteins contained in the washing solution of the first affinity chromatography had been recycled. The low yield is due mainly to the 50% loss in protein during the proteolytic cleavage step; a white precipitate that seemed to represent partial aggregation of proteins appeared during the incubation. The total purification factor was 9.6.

TABLE 1.

Summary of amylosucrase purification

| Purification step | Vol (ml) | Amylo-sucrase activity (U/liter) | Protein concn (mg/liter) | Sp act (U/g) | Overall purifi-cation factor | Overall yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sonication supernatant | 1.5 | 8,120 | 8,184 | 992 | 1 | 100 |

| 1st affinity chromatog-raphy | 8.2 | 1,024 | 210 | 4,876 | 4.9 | 69 |

| Proteolysis | 8.2 | 669 | 108 | 6,194 | 6.2 | 45 |

| 2nd affinity chromatog-raphy | 21.3 | 220 | 23 | 9,565 | 9.6 | 38 |

FIG. 3.

Purification of amylosucrase. (A) Expression of GST-AS fusion protein in pGEX-6-P-3 and purification of amylosucrase by using glutathione-Sepharose 4B. Electrophoresis was in denaturing conditions. Lanes: 1, low-molecular-weight electrophoresis calibration kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech); 2, sonicate supernatant of E. coli BL21 cells transformed with GST-AS expression plasmid pGEX-6-P-3 (142 ng); 3, eluate following purification of sonicate on glutathione-Sepharose 4B and elution with elution buffer (purified GST-AS) (117 ng); 4, flowthrough following PreScission protease digestion of GST-AS (purified amylosucrase) (111 ng); 5, low-molecular-weight electrophoresis calibration kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). (B) Electrophoresis in native conditions. Lanes: 1, high-molecular-weight electrophoresis calibration kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech); 2, purified amylosucrase (148 ng); 3, low-molecular-weight electrophoresis calibration kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). (C) Isoelectric focusing. Lanes: 1, isoelectric focusing calibration kit (Pharmacia); 2, purified amylosucrase (98 ng).

The pure enzyme was subjected to several electrophoreses. Under both native and denaturing conditions, the molecular mass obtained was 70 ± 2 kDa (Fig. 3B). This result demonstrates the monomeric structure of the amylosucrase from N. polysaccharea and also confirms the predicted molecular mass of the amylosucrase truncated by the deletion of its 11 N-terminal amino acids i.e., 71.7 kDa. The pI obtained by isoelectric focusing was 4.9 ± 0.2, which does not differ significantly from the predicted pI of 5.44 for the purified protein (Fig. 3C).

Characterization of the glucan synthesized by pure amylosucrase.

Amylosucrase catalyzes the synthesis of α-(1→4)-glucan from sucrose without any primer (5). Nevertheless, the polymer-synthesizing rate has been shown to be greatly increased in the presence of a glucan primer, and particularly of glycogen (33). To determine the role of the primer in the activated reaction, the polymer synthesized by pure amylosucrase from sucrose, with glycogen as a primer, was analyzed.

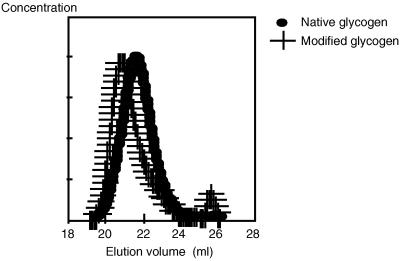

The first step was the analysis by HPSEC to check the homogeneity of the sample. Native glycogen showed one peak whose concentration maximum occurred at an elution volume (Ve) of approximately 21.6 ml. The same pattern was observed for the modified glycogen but at a lower Ve, 20.8 ml (Fig. 4). This result demonstrates that the product obtained is composed of one macromolecule population presenting a  w higher than that for the initial glycogen.

w higher than that for the initial glycogen.  w values determined for the initial glycogen and modified molecule are 9.9 × 106 and 15.3 × 106 g/mol, respectively. R̄G, values which give relevant information about macromolecule size (43), were also determined from the SEC-MALLS results. R̄G values for native and modified glycogens are 20 ± 4 and 25 ± 1.7 nm, respectively. This change is in agreement with the variation in

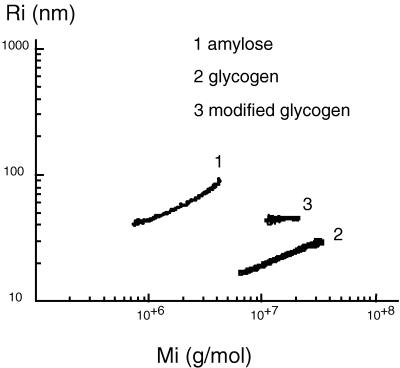

w values determined for the initial glycogen and modified molecule are 9.9 × 106 and 15.3 × 106 g/mol, respectively. R̄G, values which give relevant information about macromolecule size (43), were also determined from the SEC-MALLS results. R̄G values for native and modified glycogens are 20 ± 4 and 25 ± 1.7 nm, respectively. This change is in agreement with the variation in  w. Mi and Ri were calculated for each elution volume (Vi) of the elution pattern. In Fig. 5, Ri is plotted versus Mi for native and modified glycogens and for one wheat amylose standard (2, 36); this plot allows comparison of glycogen with a linear macromolecule, demonstrating clearly that SEC behavior of branched macromolecule such as native and modified glycogens are very different from that of a linear molecule, irrespective of molecular mass. Obviously, modified glycogen behavior is similar to that of neither initial glycogen nor amylose. At the same Mi, Ri values for modified glycogen are higher than for native glycogen. These results could be related to the branching differences between these two samples: modified glycogen presented an expanded structure, excluding the occurrence of the same branching pattern as in glycogen.

w. Mi and Ri were calculated for each elution volume (Vi) of the elution pattern. In Fig. 5, Ri is plotted versus Mi for native and modified glycogens and for one wheat amylose standard (2, 36); this plot allows comparison of glycogen with a linear macromolecule, demonstrating clearly that SEC behavior of branched macromolecule such as native and modified glycogens are very different from that of a linear molecule, irrespective of molecular mass. Obviously, modified glycogen behavior is similar to that of neither initial glycogen nor amylose. At the same Mi, Ri values for modified glycogen are higher than for native glycogen. These results could be related to the branching differences between these two samples: modified glycogen presented an expanded structure, excluding the occurrence of the same branching pattern as in glycogen.

FIG. 4.

HPSEC profiles of starches from native and modified glycogens.

FIG. 5.

Ri versus Mi for amylose and for native and modified glycogens.

β-Amylase is known to be an exo-type enzyme digesting external chains up to certain residues from a branch point. The different branching pattern were confirmed by measuring the β-amylolysis limit (percentage of digested material). The β-amylolysis values for the initial and modified glycogens were 65 and 77%, respectively. Deramification of each form of glycogen was performed with isoamylase. Products obtained after glycogen deramification exhibited a broad population of DP 12. For the modified glycogen, we detected a major peak at the same average DP and a white precipitate corresponding to longer chains.

Linear glucan or the linear part of a ramified glucan is able to form complexes with iodine, and the absorption maximum of the glucan-iodine complex (λmax) depends on the linear glucan average chain length (13). The initial glycogen presents a λmax at 435 nm, in contrast to 605 nm for the modified glycogen. λmax at 435 nm is in agreement with values usually obtained for short chains such as DP 12 obtained after glycogen deramification. λmax at 605 nm is characteristic of linear chains with an average DP of around 75 glucosyl units.

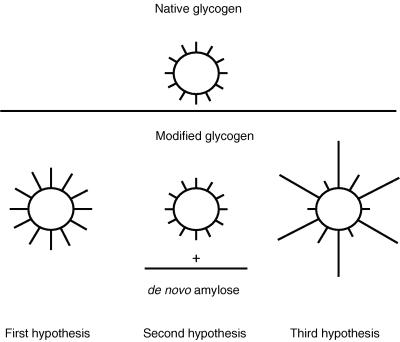

On this basis, the enzymatic action of amylosucrase on glycogen could result from (i) extension of all external chains from the nonreducing ends, with DP increasing from 12 to 18 glucosyl units uniformly; (ii) creation of a new population of α-glucans; or (iii) extension of some external chains from the nonreducing ends (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Three main hypotheses for the enzymatic action of amylosucrase on glycogen.

The first possibility should have given a λmax of around 480 to 490 nm, whereas the 605 nm measured suggests the presence of longer linear chains. Deramification and Dionex results also contradict this view. The increase in β-amylolysis before and after amylosucrase synthesis is in relation with the increase of the molecular mass and should have corresponded to an extension of the chain length from 12 to 18 glucosyl units, assuming that all of the glycogen’s ramifications were lengthened equally. Although the Dionex procedure does not give an exact DP of the longer precipitated chains, the presence of a majority of chains with the same DP as in the initial glycogen demonstrates that elongation occurred on only a limited number of chains. In the case of the second hypothesis, the HPSEC profile would have had two peaks, corresponding to the native glycogen and de novo-synthesized amylose. The third hypothesis is consistent with the difficulties encountered during the deramification experiments, where released chains should have precipitated since they are located in the dissolving gap described by Aberle et al. (1), as well with the HPSEC results—at same Mi for modified glycogen as for the initial one, Ri is different, corresponding for the same molecular mass to a more expanded structure.

In conclusion, the sucrose consumption rate is increased in the presence of glycogen, and some of the polymer branchings are linearly elongated, showing that amylosucrase transfers the glucose residue onto the nonreducing ends of the glycogen molecule. This enzyme could thus be used to modify glycogen structure.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank P. Escalier for technical assistance in purification work. We thank B. Canard and I. Varlet for having graciously furnished DNA bank of N. polysaccharea.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aberle T, Burchard W, Vorwerg W, Radosta S. Conformational contributions of amylose and amylopectin to the structural properties of starches from various sources. Starch. 1994;46:329–335. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banks W, Greenwood C T. Starch and its components. Edinburgh, Scotland: University Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bello-Perez A, Roger P, Baud B, Colonna P. Macromolecular features of starches determined by aqueous high-performance size exclusion chromatography. J Cereal Sci. 1998;27:267–278. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Büttcher V, Welsh T, Willmitzer L, Kossmann J. Cloning and characterization of the gene for amylosucrase from Neisseria polysaccharea: production of a linear α-1,4-glucan. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3324–3330. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3324-3330.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devulapalle K S, Goodman S D, Gao Q, Hemsley A, Mooser G. Knowledge-based model of a glucosyltransferase from the oral bacterial group of mutans streptococci. Protein Sci. 1997;6:2489–2493. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560061201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hehre E J, Hamilton D M, Carlson A S. Synthesis of a polysaccharide of the starch-glycogen class from sucrose by a cell-free, bacterial enzyme system (amylosucrase) J Biol Chem. 1949;177:267–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holm L, Koivula A K, Lehtovaara P M, Hemminki A, Knowles J K C. Random mutagenesis used to probe the structure and function of Bacillus stearothermophilus alpha-amylase. Protein Eng. 1990;3:181–191. doi: 10.1093/protein/3.3.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishikawa K, Matsui I, Honda K, Nakatani H. Multi-functional roles of a histidine residue in human pancreatic α-amylase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;183:286–291. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91641-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janecek S. Parallel β/α-barrels of α-amylase, cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase and oligo-1,6-glucosidase versus the barrel of β-amylase: evolutionary distance is a reflection of unrelated sequences. FEBS Lett. 1994;353:119–123. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janecek S, Svensson B, Henrissat B. Domain evolution in the α-amylase family. J Mol Evol. 1997;45:322–331. doi: 10.1007/pl00006236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jespersen H M, MacGregor E A, Henrissat B, Sierks M R, Svensson B. Starch- and glycogen-debranching and branching enzymes: prediction of structural features of the catalytic (β/α)8-barrel domain and evolutionary relationship to other amylolytic enzymes. J Protein Chem. 1993;12:791–805. doi: 10.1007/BF01024938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.John M, Schmidt J, Kneifel H. Iodine-maltosaccharide complexes: relation between chain-length and colour. Carbohydr Res. 1983;119:254–259. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kato C, Nakano Y, Lis M, Kuramitsu H K. Molecular genetic analysis of the catalytic site of Streptococcus mutans glucosyltransferases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;189:1184–1188. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)92329-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein C, Hollender J, Bender H, Schulz G E. Catalytic center of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase derived from X-ray structure analysis combined with site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 1992;31:8740–8746. doi: 10.1021/bi00152a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15a.Kossmann, J. 1998. Personal communication.

- 16.Kuriki T, Takata H, Okada S, Imanaka T. Analysis of the active center of Bacillus stearothermophilus neopullulanase. J Bacteriol. 1991;135:1521–1528. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.19.6147-6152.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larson S B, Greenwood A, Cascio D, Day J, McPherson A. Refined molecular structure of pig pancreatic α-amylase at 2.1 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:1560–1584. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacGregor E A, Jespersen H M, Svensson B. A circular permuted α-amylase-type α/β-barrel structure in glucan-synthesizing glucosyltransferases. FEBS Lett. 1996;378:263–266. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01428-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacKenzie C R, Johnson K G, McDonald I J. Glycogen synthesis by amylosucrase from Neisseria perflava. Can J Microbiol. 1977;23:1303–1307. doi: 10.1139/m77-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacKenzie C R, McDonald I J, Johnson K G. Glycogen metabolism in the genus Neisseria: synthesis from sucrose by amylosucrase. Can J Microbiol. 1978;24:357–362. doi: 10.1139/m78-060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacKenzie C R, Perry M B, McDonald I J, Johnson K G. Structure of the d-glucans produced by Neisseria perflava. Can J Microbiol. 1978;24:1419–1422. doi: 10.1139/m78-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuura Y, Kusunoki M, Harada W, Kakudo M. Structure and possible catalytic residues of Taka-amylase A. J Biochem. 1984;95:697–702. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monchois V, Remaud-Simeon M, Russel R R B, Monsan P, Willemot R M. Characterization of Leuconostoc mesenteroides NRRL B-512F dextransucrase (DSRS) and identification of amino-acid residues playing a key role in enzyme activity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;48:465–472. doi: 10.1007/s002530051081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagashima T, Tada S, Kitamoto K, Gomi K, Kummagai C, Toda H. Site-directed mutagenesis of catalytic active-site residues of Taka-amylase A. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1992;56:207–210. doi: 10.1271/bbb.56.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura A, Haga K, Ogawa S, Kuwano K, Kimura K, Yamane K. Functional relationships between cyclodextrin glucanotransferases from an alkalophilic Bacillus and α-amylases. FEBS Lett. 1992;296:37–40. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80398-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakamura A, Haga K, Yamane K. Three histidine residues in the active center of cyclodextrin glucanotransferase from alkalophilic Bacillus sp. 1011: effects of the replacement on pH dependence and transition-state stabilization. Biochemistry. 1993;32:6624–6631. doi: 10.1021/bi00077a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson H. A photometric adaptation of the Somogyi method for the determination of glucose. J Biol Chem. 1944;153:375–380. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okada G, Hehre E J. De novo synthesis of glycosidic linkages by glycosylases: utilization of α-d-glucopyranosyl fluoride by amylosucrase. Carbohydr Res. 1973;26:240–243. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)85045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okada G, Hehre E J. New studies on amylosucrase, a bacterial α-d-glucosylase that directly converts sucrose to a glycogen-like α-glucan. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:126–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pashall E F, Foster J F. Further studies by light scattering of amylose aggregates. Particle weight under various conditions. J Polym Sci. 1952;9:85–52. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Planchot V, Colonna P, Saulnier L. Dosage des glucides et des amyloses. In: Godon B, Loisel W, editors. Guide pratique d’analyses dans les industries des céreales. 1997. pp. 346–397. Publication Lavoisier, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Preiss J, Ozbun J L, Hawker J S, Greenberg E, Lammel C. ADPG synthetase and ADPG-α-glucan-4-glucosyltransferase: enzymes involved in bacterial glycogen and plant starch biosynthesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1973;210:265–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1973.tb47578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Remaud-Simeon M, Albaret F, Canard B, Varlet I, Colonna P, Willemot R M, Monsan P. Studies on a recombinant amylosucrase. In: Petersen S B, Svensson B, Pedersen S, editors. Carbohydrate bioengineering. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science B.V.; 1995. pp. 313–320. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riou J Y, Guibourdenche M, Popoff M Y. A new taxon in the genus Neisseria. Ann Microbiol (Inst Pasteur) 1983;134B:257–267. doi: 10.1016/s0769-2609(83)80038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riou J Y, Guibourdenche M, Perry M B, MacLean L L, Griffith D W. Structure of the exocellular d-glucan produced by Neisseria polysaccharea. Can J Microbiol. 1986;32:909–911. doi: 10.1139/m86-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roger P, Colonna P. Molecular weight distribution of amylose fractions obtained by aqueous leaching of maize starch. Int J Biol Macromol. 1996;19:51–61. doi: 10.1016/0141-8130(96)01101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sumner J B, Howell S F. A method for determination of invertase activity. J Biol Chem. 1935;108:51–54. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Svensson B. Protein engineering in the α-amylase family: catalytic mechanism, substrate specificity, and stability. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;25:141–157. doi: 10.1007/BF00023233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Svensson B, Frandsen T P, Matsui I, Juge N, Fierobe H P, Stoffer B, Rodenburg K W. Mutational analysis of catalytic mechanism and specificity in amylolytic enzymes. In: Petersen S B, Svensson B, Pedersen S, editors. Carbohydrate bioengineering. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science B.V.; 1995. pp. 125–145. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tao B Y, Reilly P J, Robyt J F. Neisseria perflava amylosucrase: characterization of its product polysaccharide and a study of its inhibition by sucrose derivatives. Carbohydr Res. 1988;181:163–173. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(88)84032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Krevelen D W. Properties of polymers. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1990. [Google Scholar]