Abstract

Antigen-based rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) for SARS-CoV-2 have good reliability and have been repeatedly implemented as part of pandemic response policies, especially for screening in high-risk settings (e.g., hospitals and care homes) where fast recognition of an infection is essential. However, evidence from actual implementation efforts and associated experiences is lacking.

We conducted a qualitative study at a large tertiary care hospital in Germany to identify step-by-step processes when implementing RDTs for the screening of incoming patients, as well as stakeholders’ implementation experiences. We relied on 30 in-depth interviews with hospital staff (members of the regulatory body, department heads, staff working on the wards, staff training providers on how to perform RDTs, and providers performing RDTs as part of the screening) and patients being screened with RDTs.

Despite some initial reservations, RDTs were rapidly accepted and adopted as the best available tool for accessible and reliable screening. Decentralized implementation efforts resulted in different procedures being operationalized across departments. Procedures were continuously refined based on initial experiences (e.g., infrastructural or scheduling constraints), pandemic dynamics (growing infection rates), and changing regulations (e.g., screening of all external personnel). To reduce interdepartmental tension, stakeholders recommended high-level, consistently communicated and enforced regulations.

Despite challenges, RDT-based screening for all incoming patients was observed to be feasible and acceptable among implementers and patients, and merits continued consideration in the context of high infection and stagnating vaccination rates.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Rapid diagnostic tests, Universal screening, Implementation research, Qualitative research

1. Introduction

With vaccination rates stagnating and the emergence of novel virus variants potentially escaping vaccine-induced immunity, comprehensive testing and rigorous contact tracing have been a cornerstone of controlling the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic (Erdmann, 2021; Hacisuleyman et al., 2021; Johnson-León et al., 2021; Mina & Andersen, 2020). The risks of undetected infections resulting in severe morbidity and mortality are especially pronounced in settings where high-risk populations are clustered (e.g., retirement communities and health care facilities), underscoring a need for systematic screening of incoming persons to such settings (Scheier et al., 2021).

The gold standard approach to detecting SARS-CoV-2 infections, reverse transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), is often not feasible to implement, especially in settings where rapid turnaround time is critical but also in other situations where testing capacity is constrained (Mina & Andersen, 2020). Antigen-based rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) have thus been proposed as a timely, accessible, and pragmatic complement for screening of asymptomatic persons (Johnson-León et al., 2021). In December 2020, the WHO issued an implementation guide highlighting that – despite achieving inferior sensitivity and specificity levels compared to PCR – RDTs have the potential to rapidly detect active SARS-CoV-2 infections directly at the point of care while being easier to perform and less infrastructure-dependent and expensive (World Health Organization, 2020a).

In high-income settings, with the exception of pediatric screening (e.g., for respiratory syncytial virus), RDTs have rarely been used; prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, universal screening independent of symptoms to the best of our knowledge has not been done in high-income countries (HICs). Implementation insights on RDTs more generally stem primarily from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and draw on experiences using RDTs for individual diagnosis and not infection control (Pai et al., 2015). Pre-admission SARS-CoV-2 RDT-based screening, particularly in health facilities, has repeatedly been used in HICs over the course of the pandemic. Although evidence suggests that such screening programs could have a promising diagnostic yield (Larremore et al., 2021; Scheier et al., 2021; Smith et al., 2020; Wachinger, Olaru, Horner, Schnitzler, Heeg, & Denkinger, 2021), research outlining how these programs are implemented and scaled up, and how those involved experience or adapt implementation is lacking. Given this paucity of information, the WHO called for further evidence from large-scale rollout of RDTs for SARS-CoV-2 to continuously update implementation guidance (World Health Organization, 2020a).

With this study, we fill a gap in the literature by outlining RDT-based screening implementation processes and experiences at a major German university hospital. We aim to provide lessons learned to guide similar implementation efforts.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Setting

Heidelberg University Hospital (UKHD in its German abbreviation) is among the largest tertiary care hospitals in Germany with over 13,000 employees and serving over 100,000 inpatients and 1.3 million outpatients per year (Heidelberg University Hospital, 2020). By the end of data collection for this study (March 3, 2021), a total of 19,270 SARS-CoV-2 cases and 415 deaths had been reported in the region served by the hospital (Landratsamt Rhein-Neckar-Kreis, 2021).

2.2. Intervention design

To reduce the risk of nosocomial transmission of SARS-CoV-2, UKHD introduced a hospital-wide, RDT-based screening for asymptomatic patients coming into the hospital for elective procedures (incl. day clinics) prior to admission starting from October 2020. The screening program addressed patients who were not able to provide documentation of a negative PCR result within 48 h prior to admission. In addition, depending on current infection dynamics and changing regulations within and across departments, visitors, external contractors, or translators, were similarly screened. By the end of data collection, more than 50,000 RDTs had been performed in over 30,000 individuals.

Exact implementation procedures for the screening (e.g., screening location) were developed at the discretion of individual hospital departments and day clinics. Members of the hygiene department trained staff assigned to screening (predominantly nurses, in some departments also including medical students and other medical personnel), who then trained peers in a snowball system (for training material, see supplemental file 1). Testing competency was assessed post-training (supplemental file 2). Screening was performed in designated areas in the respective departments using the STANDARD Q COVID-19 Ag Test (SD Biosensor, Inc. Gyeonggi-do, Korea), which is an independently validated, instrument-free lateral flow assay for SARS-CoV-2 detection that can be performed at point of care and is one of two RDTs listed by the WHO under the Emergency Use Listing (World Health Organization, 2020b). In instances of a positive RDT result, the respective patient was isolated and retested using a validated SARS-CoV-2 PCR.

Confirmatory PCR testing was not recommended as a routine practice in case of a negative RDT result. Patients who developed symptoms associated with a SARS-CoV-2 infection or were in contact with confirmed cases were tested using PCR during their stay at the hospital. Fig. 1 summarizes the RDT-based screening approach as intended by the hospital's task force.

Fig. 1.

Theory of Implementation as intended by decisionmakers.

2.3. Study procedures and sampling

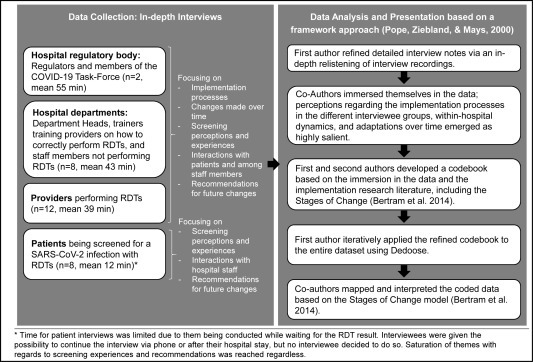

To analyze implementation processes and experiences with RDT-based screening, we conducted in-depth interviews with staff members and clients at various hospital departments. Drawing on the tenets of case study research (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015), we aimed at developing an understanding of RDT-based screening implementation from the perspective of end-users while acknowledging the importance of contextual factors in the case at hand: a large, high-income country tertiary care hospital amidst a viral pandemic. We purposefully selected a range of departments addressing different patient groups (children and adults) and clinical work (inpatient and outpatient). Participant groups at the selected departments are outlined in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

Summary of data collection and analysis processes.

Within each department and participant group, interviewees were purposefully selected and contacted through designated point persons at the respective department. In instances where several individuals were eligible (e.g., staff performing screening), interviewees were approached sequentially in the order of their expression of interest. For patient interviews, we used convenience sampling. We approached patients presenting at the RDT screening centre of the hospital's medical clinic and conducted the interview while they awaited their test results. We drew on the COREQ-guidelines (see supplemental file 3) to report study procedures and findings. The ethical review board of the Medical Faculty, Heidelberg University, Germany (S-811/2020) approved this study. Prior to data collection initiation the study was registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00023584).

2.4. Data collection and analysis

In total, we conducted 30 interviews between November 2020 and March 2021, with a maximum of two interviews being conducted per day. Beginning of data collection coincided with the initial implementation of screening; earlier stages in the implementation process were probed for in detail during the interviews. Interviewees provided written informed consent prior to interviews, and a majority of interviews were audio recorded (n = 27), with three interviewees objecting to audio recording. One department head objected to participation, quoting high pandemic-associated workload as the reason; three eligible participants did not acknowledge electronic invitations to participate. Two patients objected to participation, quoting unease with being interviewed in the context of waiting for their hospital appointment. The lead author, who has master's level education in both Psychology and Medical Anthropology and extensive experience conducting qualitative interviews, conducted all data collection. Prior to each interview, the lead author introduced themselves and their role in the study, as well as the study procedures and objectives to establish a relationship and clarify study goals. The senior author was involved in developing the intervention with the hospital task force.

Interviews were conducted in person in the clinic (for patients and a majority of staff members), with some interviews with staff members being conducted via phone (n = 4) or video call (n = 3), according to interviewee preference and availability. In the clinic context, interviewees chose their preferred interview location based on spatial or situational constraints, the pandemic context, and privacy considerations. For interviewed staff members, preferred interview locations included offices/workplaces, break rooms, or outside spaces. Depending on the chosen location, other staff members sometimes would be within hearing distance for parts of the interview (e.g., in break rooms and shared offices). All interviewees preferred continuing the interview in their chosen location, sometimes pausing shortly when discussing particularly critical opinions until privacy could be assured. To minimize disruption to clinical workflows and following interviewee preferences, patient interviews were conducted in the waiting area of the screening centre, ensuring ample distance to other individuals waiting for their results. However, non-participating individuals sometimes passed by, potentially coming into hearing distance; no participant preferred halting the interview until absolute privacy could be ensured.

The interviewer took detailed notes during interviews, and these notes were later supplemented with further information and quotes following an in-depth relistening of interviews. Members of the study team met regularly over the entire duration of data collection and analysis for systematic debriefings, discussing and iteratively refining interview questions, probes, emerging themes, and pathways for further inquiry (McMahon & Winch, 2018).

We followed a framework approach (Pope, Ziebland, & Mays, 2000) to analyze our data: First and second authors immersed themselves in the data after observing saturation (defined as “the point in data collection and analysis when new information produces little or no change to the codebook”) (Guest, Bunce, & Johnson, 2006) for themes related to RDT perception and implementation. Perceptions of and conflicts during screening implementation, and associated changes over time, emerged as highly salient. Based on emerging themes and revisiting the implementation frameworks literature, co-authors developed a codebook, focusing on processes, experiences, and adaptations highlighted by each of the four interviewee groups (Members of the hospital regulatory body, hospital department heads and staff, providers performing RDTs, and patients being screened), as well as within-hospital dynamics and recommendations for future refinement. The first author then applied this codebook iteratively to the entire dataset using Dedoose (https://dedoose.com/). Coded data then were mapped and interpreted by first and second authors with the assistance of all co-authors based on the stages of implementation as outlined by Bertram and colleagues (Exploration, Installation, Initial Implementation, Full Implementation) (Bertram, Blase, & Fixsen, 2014) to highlight stakeholder activities and perceptions over time. See Fig. 2 for an outline of data collection and analysis processes. To protect interviewee anonymity in the hospital setting, we attribute quotes from hospital staff based on interviewee type only. For patient quotes, we use gender (four male and four female interviewees) and age (range 47–73 years with one interviewee preferring not to disclose) as identifiers. One co-author was included as a respondent due to their role as a key stakeholder in the intervention development; no verbatim quote was included from this person.

3. Results

3.1. Exploration, installation, and implementation of the RDT-based screening

Table 1 outlines our results following the four stages of implementation (Bertram et al., 2014) and the four main interviewee groups of this study as introduced above. We then outline implementation processes and experiences of the RDT-based screening, and how these changed over time, for each interviewee group, highlighting heterogeneous experiences within and across interviewee groups. Particularly salient themes are exemplified as key quotes in Table 2 (section 3.2), as well as in the in-depth Exemplary Cases 1 and 2 (section 3.3).

Table 1.

Exploration, Installation, and Implementation of the intervention.

| Exploration | Installation | Initial Implementation | Full implementation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital regulatory body |

|

|

|

|

| Hospital departments |

|

|

||

| Providers |

|

|

||

| Patients |

|

|

Table 2.

Acceptance of and experiences with RDT-based screening - illuminating quotes.

| Installation |

|---|

| Selecting staff and negotiating workload |

| “So, there were no staff resources to implement these RDTs between today and tomorrow. Per decree it was said this is being done from tomorrow onwards, and that makes sense, that's ok, but how you please implement it, for that we were on our own. And there then people just said, ok we do this on top. I assume that people started going to work earlier, or certain tasks were being left undone. It somehow worked.” (Department head) |

| “When implementing something new like that, one key question is: What staff? So, when building such a new team you always need a core team in the beginning which you have built consciously. These have to be people with regards to personality, experience, visionary thinking, well organized, to be able to work with each other … because they have to work closely together, shape this, fill this idea with life. … It's about liking to do something like that!” (Department head) |

| “Of course, some (departments asked to provide staff for screening) sometimes were like ‘Oh, but it's difficult.’ But when you then talk about it and constructively discuss about, ok, how could you partly compensate for the departure of this employee, or what other possibilities are there, some others who don't want to work in the screening center … a lot of that works through larger circular exchange. But we really take that serious, the nursing department has to be ready to go along, otherwise it makes no sense.” (Department head) |

| Initial Implementation |

| Bolsters a sense of safety and security |

| “It's very effective. … For us it gives security, for the staff it gives security, and for the employees, and for the general situation when patients come to the ER and space is limited then you know whether someone there has a COVID infection or not. So it gives you incredible security.” (Provider performing RDTs) |

| “Sometimes it also gave this false sense of security, ahem, that you just didn't isolate patients because you trusted the test a lot. But I think if you … yourself follow your own gut feeling and … watch out, then it works. Rather with RDT than without RDT I think.” (Provider performing RDTs) |

| “That also gives (the patients) a sense of security. Most patients are in a two bed room here, with another unknown person. That's one thing. And it also conveys the security that this institution knows what they are doing, ahem, also how the ways here are, that starts at the entrance, how that is factually separated.” (Department head) |

| Full Implementation |

| Impact of within-hospital dynamics |

| “Many say that they think it's great how it works, the procedures are good. But there are some risks that … especially in the last time increase. Because in a way, it's a form of leverage. So there are departments where a patient comes who has certain laboratory values, some inflammation indicators, that don't tell you anything regarding COVID. But they then start, because they are afraid themselves, to send them to us, although there is in fact no reason. And are saying that they only allow the patient into a room, for a talk, if we test him before. That's difficult … because in fact there is no reason, but of course you can understand on the human level that if someone is sitting there who is coughing and whatever, I as well would like to have a swab.” (Provider performing RDTs) |

| “(The main challenge is) to stay firm. To not let anyone twist you around the little finger. ‘could you quickly … or I want because I have a Prof. Dr. in front of my name.’ To just endure certain things, those maybe are the barriers.” (Provider performing RDTs) |

| Desire for clear and collaborative communication |

| “So, if you ask me what could be done differently, sometimes one could get the clinicians into the room, I think, when you would include a representative from surgery, from dentistry, from internal medicine, from everyone. And then together for the implementation of such a test say: Ok, that's our plan, does something speak against that, based on your professional experience? That didn't happen, and the time for that would have been there. And I think that then, ahem, the one or the other thing could have been done earlier and maybe better. And when you get the people on board, then the compliance is higher, the acceptance is higher. And with the higher acceptance the result is better” (Department head) |

| “I also have to say that (the screening regulations) are changed all the time. It's not all that easy to maintain an overview regarding who is screened where.… Such things I'm usually only told by the nurses.” (Provider performing RDTs) |

| “That would be one thing, to write that you have to come 1 h earlier than your appointment. … Maybe that would have been one thing to write or say in advance. …. Now I have to tell them upstairs that I had to wait this long. Of course they know that, but that could have been avoided. … They told me that I would have to get tested but not how long this would take.” (Male patient, undisclosed age) |

| Weighing of RDTs versus other testing approaches |

| “Everyone knows we don't have anything better. … And everyone knows that we have a quota (of identifying positive cases) of 90%, and that's true. And the small risk that is left … that has to be tolerated. But it's better than having nothing, that is a fact, and everyone can live with that and has accommodated to that, and I don't think anyone would want it otherwise.” (Department head) |

| “Regarding the RDTs, how much I trust them … rather limited in fact. Rather limited. Ahem, I often had it now that the RDT then surprisingly was positive, and we then were able to isolate early on. That was great. But I also already had it that, on the other hand, that the RDTs were false negative. And, ahem, therefore (my perception of the RDTs) is rather ambivalent.” (Provider performing RDTs) |

| “What confuses me, this no PCR test. That I'm curious about. (My son-in-law) also had a surgery in Hamburg, and he had to come in the morning and had to sit the entire day in a quarantine room, and they did a PCR test. And here, considering it's Heidelberg University Hospital, I'm surprised. Very surprised. Extremely surprised.” (Male patient, 73 years) |

3.1.1. Members of the hospital regulatory body

The hospital regulatory body played a central role in the exploration and installation phases of the intervention. Interviewees recounted how they initially had hoped for PCR-based screening to be feasible. However, due to laboratory constraints and a pilot of PCR screening in one ENT department which proved to be highly disruptive to clinical workflows, RDT-based screening was seen as the alternative “on the table” to contend with a second wave of infections. As large-scale validation studies of RDTs for SARS-CoV-2 were performed in the infectious disease department of the university hospital (a “fabulous situation for us”, Member of regulatory body), interviewees recounted how they felt “encouraged” and had little objection to RDT-based screening once a test was identified that seemed to fit their main criteria: ease of use, rapid turnaround times (facilitating point-of-care administration and minimal staff training), consistent supply chains, and an acceptable sensitivity and specificity. Once this test was identified in August 2020, the hospital regulatory body set up stable supply chains and developed overarching guidelines for screening implementation. Interviewees said they did “not want to make any regulations for things we do not understand”, so exact implementation parameters were left to the discretion of individual departments who “are the ones on the ground and who know this” (Member of regulatory body). At the end of September 2020, installation began “just in time” (Member of regulatory body) so that the screening could be adopted and refined prior to future infection waves. Regulators viewed their later role largely as providing refinements of the general regulations or guidance in light of new infection or patient dynamics.

3.1.2. Department heads and staff members

At the level of hospital departments, all interviewees described a high acceptance of screening based on previous experiences with asymptomatic patients entering the hospital: “We knew what it feels like when cases are discovered only later … And that always resulted in this huge wave of contact tracing, contacts with staff, notifying the Gesundheitsamt [German regional health authority], sending patients or staff into quarantine and so on” (Department Head). One interviewee described how she perceived such a rapid implementation only to be feasible because “I don't think there was anyone who didn't think this was a good thing” (Trainer). Some interviewees reported that they themselves or colleagues initially were highly skeptical with regards to the reliability of RDTs and the potential disruption to clinical workflows induced by incorrect results but based on the recent in-house validation data most agreed that “that doesn't look too bad – not 100%, but we can use that” (Department Head).

The selection of suitable location and personnel was among the core installation tasks for department heads. The selection of staff focused on an even distribution of burden across departments and identifying individuals who would be creative and nimble. Selected personnel were given a certain flexibility to develop procedures, “because they are the ones who actually work there and bring in their expectations and ideas regarding the organization (of the implementation). So, they shaped this, and they also reshaped it after some time to improve it even further. But that really was something we allowed the team to decide” (Department head). Certain wards whose patient groups did not qualify for screening by the centralized departmental screening centers (e.g., wards serving outpatients not requiring close contact treatment) decided to introduce screening independently, because “although integrating it into a normal schedule is hardly possible”, the screening was perceived as a “lesser evil” compared to the risk of nosocomial infections (Department head). Some participants said reports of false-negative RDT results caused concern or disillusionment. However, after roughly two months, the screening and its necessity was seen as generally highly accepted across wards, to the point that “if you would stop it now, that would lead to a lot of unrest” (Department head).

Communication between wards emerged as a key factor across interviews. Initially, the screening resulted in some disruption of workflows on admitting wards. Over time, processes were adapted to minimize such disruptions, both on the side of the admitting wards (e.g., by informing patients to come earlier) and the respective screening center or personnel (e.g., by starting screening hours earlier). Despite continuing refinement of screening procedures and increasing acceptance, tensions between departments still emerged as some departments requested that ineligible patient groups be screened (e.g., ambulatory patients outside of day clinics).

3.1.3. Providers performing RDTs with patients

Most providers appreciated the flexibility they had regarding implementation processes and recounted how their daily experiences facilitated continuous implementation refinement: “Everything that has to do with humans you can plan on paper somehow and it then doesn't work when the people come. And that's how it works” (Provider performing RDTs). Several interviewees recounted challenges of integrating the screening into an already high workload, both for themselves and for colleagues on the wards who had to compensate for screeners' absence, and of contending with initial administrative and infrastructural challenges. Interviewees also described how screening processes became more and more routinized, making it possible to accommodate rapidly increasing numbers of patients and personnel coming for screening: “You get used to everything, that's the way it is here in the hospital” (Provider performing RDTs). The initially envisioned possibility for patients to provide proof of a recent negative PCR result as an alternative to the RDT-based screening was not reported as enacted by any department because confirming test documentation proved infeasible or outdated. Providers reported the test itself to generally be easy to perform, although testing small children (especially those aged 2–4) and patients with mental illness or dementia proved highly challenging.

According to several interviewees, the most powerful and decisive factor in swaying teams to favor screening with RDTs was the discovery of an asymptomatic positive case: “So I remember, when the first positive patient was found, everything up there was standing still. Because no one had really expected that, because of course you think you have symptoms, you cough, you have fever. But these really are people who are, in quotation marks, completely healthy walking in here and are discovered by chance by this test” (Provider performing RDTs). As a result, several interviewees described how the screening gave them an “incredible security” (Provider performing RDTs).

However, an additional burden to providers performing screening were “trench fights” associated with staff from various departments repeatedly trying to procure screening for ineligible patients, which providers described as “madness”, and something you had to “just endure” (Providers performing RDTs). Interviewees shared how they appreciated their own department head's support but would prefer enforcement of existing regulations on the level of regulatory bodies to minimize strain associated with repeated interdepartmental negotiations. Providers also recounted how they often were surprised by the sudden, urgent need to implement novel screening strategies and to contend with constantly changing regulations. While they acknowledged that infection dynamics were fluid and regulations had to be adapted accordingly, several interviewees described confusion regarding strategies that seemed to “not make sense”, be “stressful”, “not fair”, or “just impossible” (Providers performing RDTs) such as the screening of visitors allowed to enter the building, while at the same time denying regular staff screening.

3.1.4. Patients screened with RDTs before being admitted to the hospital

Patients expressed high acceptance of screening, viewing it as “expectable” (even when they had not been forewarned; female patient, 48 years), “essential” (male patient, undisclosed age), “smooth” (female patient, 47 years), and “for the benefit of everyone” (male patient, 68 years). One mentioned that their trust in the hospital would be diminished if “they weren't doing something like this here … I can hardly imagine having trust in a hospital that doesn't consider screening patients” (male patient, 68 years). Some interviewees compared the RDTs used in this setting with what they had experienced or heard about elsewhere, including test reliability (as compared to PCR), and sampling procedures, but generally acknowledged that the decisionmakers at the hospital would “know more about this” (male patient, 68 years). Patients' overall high acceptance was confirmed by providers, who described critical or rejecting voices being the minority and largely linked to misgivings about the swab itself or to exceptionally timely circumstances (such as rushing to see a dying relative). However, patients criticized imprecise communication regarding value and duration of screening.

3.2. Key implementation experiences across interviewee groups

Across departments and participant groups, hospital staff emphasized a perceived increase in safety associated with the screening; within-hospital (or cross-departmental) dynamics that could challenge implementation success; a desire for more timely information and collaborative decision making as programs are introduced or regulations change; the relevance of selecting engaged staff and fostering positive team dynamics; and regular weighing of RDTs versus other testing approaches (see Table 2 for key quotes across each theme). Sense of increased safety, desire for clearer communication, and weighing different screening approaches were mirrored in patient interviews.

3.3. Variation in adaptation between wards and over time

Implementation approaches and processes were continuously refined and generally varied across departments, based on departmental demands and workflows (e.g., patient characteristics, available space and personnel), changes in the guidelines of the regulatory body (e.g., based on changing infection dynamics or due to new insights etc.) or internal dynamics (e.g., demands of staff or patients, financial and infrastructural considerations etc.). To highlight the variability of intervention adoption and adaptation, we present two exemplary cases: Case 1 is a centralized screening center responsible for screening patients admitted to several departments; Case 2 is a day clinic that repeatedly changed screening procedures for its outpatients over time based on patient and provider demands, changing infection dynamics, and the experience of nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infections introduced by an asymptomatic outpatient.

3.3.1. Exemplary Case 1. “It was a long process … but it worked well because everyone brought their ideas to the table” – A centralized screening center in a large clinic

Several departments opted to centralize RDT-based screening in one central area within the hospital's main atrium. Providers working in this screening center described how the implementation process was challenging to organize and had to happen rapidly, but also said that a lack of rigid implementation regulations allowed for creativity. The existence of screening and their own involvement left several interviewees with a sense of “supporting somewhere where help is needed right now” (Provider performing RDTs). At the outset, only patients admitted to high-risk wards were systematically screened; this restricted roll-out was meant to limit screening burden and allow procedures to routinize prior to scale up. Within three months, screening expanded, and providers said that their routines had become “effective” and “like an assembly line”. While increases in the number of patients to be screened was “exhausting,” mutual reassurance bolstered a sense of teamwork: “We kept internal statistics, like ‘Oh, today we had 168, that's the new house record!’ Also to show ourselves how much we had accomplished” (Providers performing RDTs).

Interviewees described how departments often undervalued the effort required to screen. Beyond the swabbing itself -- the “easiest part” -- providers recounted how running the screening center also required complex documentation procedures and diplomatic skill when managing the queue during “rush hour” (Providers performing RDTs), factors left unacknowledged by some members of the hospital staff. One interviewee described how she felt that screeners had become de facto first responders for individuals entering the building. Interviewees described interactions with patients as predominantly positive albeit more perfunctory than either side would like: “In the beginning because of the just 20 patients per day we had a lot of time to talk with them, but by now you barely talk with the patients. You swab the patient and let them wait, and then the result is declared, and that's it” (Provider performing RDTs). Interviewees struggled to implement rapidly changing regulations regarding who gets screened. Declining screenings for overly eager wards or patient groups who did not qualify for screening was particularly “draining”. As one interviewee said, “No one wants to say, ‘It's too much, or it's getting to be too much.’ But there are situations here and there where you feel you're being used … (Department-based doctors) think, ‘Oh, it's not too much. … I'll just send this entire group to the screening center.’ … You really have to push back or you'll get mowed over.” (Provider performing RDTs).

3.3.2. Exemplary Case 2. “It changes all the time” – continuous refinement of screening of outpatients who come for regular day clinic procedures

Even before the introduction of RDT-based screening, one department pre-emptively started weekly PCR testing of outpatients (all high-risk outpatients visiting multiple times a week). Despite this measure, one asymptomatic patient, who had received a negative PCR result days prior, sparked infections among staff and patients. When RDTs became available hospital-wide, the department adopted the approach, but noted that RDTs required much more personnel time compared to PCR testing, which could be outsourced to a lab. “The additional work was huge. And until everyone was able to do that, let's say handling-wise, that did take a little while. By now everything works very very well, but the initial time was challenging” (Department head).

Over the course of implementation, adaptations were frequently made to react to changing infection dynamics, requests from staff and patients, and infrastructural and financial circumstances: “In the beginning it was just when something was suspected. … And then it was once per week, then twice per week, then it was again reduced to once per week, and then we switched to this one PCR and one RDT (per week)” (Provider performing RDTs). Adaptations also included testing of patients before they entered the treatment room, or short-term increases in test frequency. These decisions were based on patients’ risk profiles. The latest screening approach of one PCR (beginning of the week) and one RDT (end of the week) was described as highly accepted by providers, both among their peers and patients.

4. Discussion

In this study, we outline implementation processes and experiences with RDT-based universal screening for SARS-CoV-2 in a tertiary care hospital setting in Germany. The screening was highly accepted across interviewee groups. RDTs were described as imperfect regarding their reliability, but as the best available tool to facilitate entrance screening for all admitted patients. Implementation processes highlight how decentralized screening allows for setting up efficient workflows, but clear and, where possible, consistent instructions and regulations on screened patient groups and comprehensive communication of these regulations would reduce burden associated with interdepartmental negotiations.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to provide in-depth qualitative insights into the implementation of RDT-based screening for SARS-CoV-2 in hospital settings, hence findings could inform implementation policies and processes in similar contexts. However, the setting of a large university hospital and the fast-changing nature of the ongoing pandemic merits caution when making large-scale comparisons between groups and over time. Additionally, some findings and recommendations regarding implementation policies and procedures might not be applicable to other settings, including smaller or lower-resourced hospitals where staffing or test procurement challenges are more acute.

Both modeling (Larremore et al., 2021; Smith et al., 2020) and prospective studies (Rottenstreich et al., 2021; Scheier et al., 2021) have highlighted the potential of frequent and repeated screening for SARS-CoV-2. A number of authors and organizations, including the WHO, have repeatedly called for a rapid scale-up of RDT-based SARS-CoV-2 screening in various settings (e.g. hospitals, nursing homes, restaurants, or airports) (Johnson-León et al., 2021; Mina & Andersen, 2020; Peeling & Olliaro, 2021; World Health Organization, 2020a). Recent evidence also has highlighted the acceptability and feasibility of RDT-based screening in a primary school setting (Wachinger, Schirmer, Täuber, McMahon, & Denkinger, 2021). Our study complements this discussion by highlighting that implementing RDT-based screening in a hospital setting is highly accepted albeit challenging.

Experience with RDT-based screening in high-income settings is limited to a few exceptions where point-of-care screening for influenza was introduced (e.g., Lankelma et al., 2019), which commonly focus on assessing the diagnostic yield of a given screening. A scoping review assessing rapid, point-of-care testing for HIV in Canada found high acceptance and satisfaction across diverse population groups and testing locations (including hospitals) (Minichiello et al., 2017). Similarly, a systematic review of implementation barriers to point-of-care testing for HIV highlighted challenges such as a disruption of clinical workflows, which is mirrored in our study (Pai et al., 2015). However, the employment of RDT-based screening for facility-wide infection control in a high-income setting in the case at hand presents a different use-case that limits comparability.

Our interviewees appreciated clear regulations and logistical support, but emphasized how flexibility and more lead time were needed to develop context-specific working routines. This slightly contradictory finding (interviewees want comprehensive updates but also fewer changes) highlights a challenge for policymakers to develop clear guidelines while responding to emerging, context-driven changes. Providing comprehensive blueprints for RDT-based screening that allow for adaptation to circumstances on the ground would be recommended across settings. Our study also highlights how conflicts arose due to attempts by some to procure screening for groups deemed ineligible by the regulator. Collaborative decision making, the enforcement of regulations at all levels, and clear attribution of roles and responsibilities would likely reduce interdepartmental negotiation.

Considering the persistently high transmission rates in many countries and the emergence of vaccination-escaping SARS-CoV-2 variants, screening in high-risk settings will remain necessary. Based on our findings, we recommend implementers and policymakers to ensure clear, stable and enforced screening guidelines. Additionally, both researchers and policymakers should consider how task-shifting to non-medical providers performing the tests could be optimized to minimize errors and maximize capacity. We urge further research to determine the transferability of findings to other institutionalized settings such as nursing homes or schools, but also other settings marked by a set environment with stable groups of people and limited influx from outside, for example large companies.

4.1. Methodological considerations

This study has limitations. Due to the pandemic situation at the time of data collection, we had to adapt our methodological approach. First, we gave interviewees the option to choose whether they wanted to participate online or face-to-face, resulting in a combination of methods for data collection. However, we did not observe a difference in data quality or depth between online and face-to-face interviews, in line with experiences from other settings (Reñosa et al., 2021). Additionally, implemented infection control measures did not allow us to conduct in-person focus group discussions (FGDs) which might have yielded additional data on shared experiences among staff members; based on our experience with the challenges of online FGDs (Aligato et al., 2021), we decided to forgo FGDs and focus on in-depth interviews for the purpose of this study. Finally, clinical and screening procedures limited the time for and privacy of interviews with patients. While we did experience open and critical discussions with regards to the implemented screening approach, the time might not have been enough to build the rapport required for in-depth discussions of more personal topics such as individual risk-factors or medical history.

5. Conclusions

This study provides evidence for policymakers on how rapid universal screening at the point of care is feasible and highly accepted but requires clear guidance that can be adapted to local settings, as well as good communication on all levels. Based on the results from our study, we encourage policymakers, researchers, and medical providers to consider exploring the potential of point-of-care screening also beyond the ongoing pandemic for other infectious diseases (e.g., RSV and influenza) upon entering a hospital to reduce the risk of secondary infections within high-risk settings.

Ethical statement

This study received ethical approval from the ethical review board of the Medical Faculty, Heidelberg University, Germany (S-811/2020). Prior to data collection initiation the study was registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00023584).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

This work was supported by a grant of the Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts of Baden-Württemberg, Germany, as well as hospital-internal funds. Funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

CMD was part of the decision-making processes to implement RDT-based screening in the study setting, based on her previous work on independent validation of RDTs. Her contribution to this manuscript is independent of this role. None of the authors declare any conflicting interests, including any commercial interest related to the implementation of any diagnostic test for SARS-CoV-2. The views expressed reflect exclusively the authors’ views and not those of the institution they work for.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants for their time and contribution.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100140.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Aligato M.F., Endoma V., Wachinger J., Landicho-Guevarra J., Bravo T.A., Guevarra J.R.…Reñosa M.D.C. ‘Unfocused groups’: Lessons learnt amid remote focus groups in the Philippines. Family Medicine and Community Health. 2021;9(e001098) doi: 10.1136/fmch-2021-001098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram R.M., Blase K.A., Fixsen D.L. Improving programs and outcomes: Implementation frameworks and organization change. Research on Social Work Practice. 2014;25(4):477–487. doi: 10.1177/1049731514537687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erdmann C. 2021. Delta-Variante - Müssen wir die Teststrategie anpassen?https://publikum.net/delta-variante-teststrategie/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Guest G., Bunce A., Johnson L. How many interviews are enough?: An eperiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hacisuleyman E., Hale C., Saito Y., Blachere N.E., Bergh M., Conlon E.G.…Darnell R.B. Vaccine Breakthrough Infections with SARS-CoV-2 Variants. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;384(23):2212–2218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidelberg University Hospital . 2020. Annual report 2019.https://report.ukhd-mfhd.de/2019/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-León M., Caplan A.L., Kenny L., Buchan I., Fesi L., Olhava P.…Ramirez C.L. Executive summary: It's wrong not to test: The case for universal, frequent rapid COVID-19 testing. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;33 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landratsamt Rhein-Neckar-Kreis . 2021. Corona-Infektionsgeschehen in der Stadt Heidelberg und im Rhein-Neckar-Kreis.https://lrarnk.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/ee14457029f4480ca0f7e16a4bae0929 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Lankelma J.M., Hermans M.H.A., Hazenberg E.H.L.C.M., Macken T., Dautzenberg P.L.J., Koeijvoets K.C.M.C.…Lutgens S.P.M. Implementation of point-of-care testing and a temporary influenza ward in a Dutch hospital. The Netherlands Journal of Medicine. 2019;77(3):109–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larremore D.B., Wilder B., Lester E., Shehata S., Burke J.M., Hay J.A.…Parker R. Test sensitivity is secondary to frequency and turnaround time for COVID-19 screening. Science Advances. 2021;7(1) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd5393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon S.A., Winch P.J. Systematic debriefing after qualitative encounters: An essential analysis step in applied qualitative research. BMJ Global Health. 2018;3 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam S.B., Tisdell E.J. Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. 4th ed. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mina M.J., Andersen K.G. Covid-19 testing: One size does not fit all. Science. 2020;371(6525):126–127. doi: 10.1126/science.abe9187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minichiello A., Swab M., Chongo M., Marshall Z., Gahagan J., Maybank A.…Asghari S. Hiv Point-of-Care Testing in Canadian Settings: A Scoping Review. Frontiers in Public Health. 2017;5:76. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai N.P., Wilkinson S., Deli-Houssein R., Vijh R., Vadnais C., Behlim T.…Wong T. Barriers to Implementation of Rapid and Point-of-Care Tests for Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection: Findings From a Systematic Review (1996-2014) Point of Care. 2015;14(3):81–87. doi: 10.1097/POC.0000000000000056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeling R.W., Olliaro P. Rolling out COVID-19 antigen rapid diagnostic tests: The time is now. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2021;21(8):1052–1053. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00152-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope C., Ziebland S., Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320(7227):114–116. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reñosa M.D.C., Mwamba C., Meghani A., West N.S., Hariyani S., Ddaaki W.…McMahon S. Selfie consents, remote rapport, and Zoom debriefings: Collecting qualitative data amid a pandemic in four resource-constrained settings. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(e004193) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottenstreich A., Zarbiv G., Kabiri D., Porat S., Sompolinsky Y., Reubinoff B.…Oster Y. Rapid antigen detection testing for universal screening for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in women admitted for delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2021;224(5):539–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier T., Schibli A., Eich G., Rüegg C., Kube F., Schmid A.…Schreiber P.W. Universal admission screening for SARS-CoV-2 infections among hospitalized patients, Switzerland, 2020. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2021;27(2):404–410. doi: 10.3201/eid2702.202318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D.R.M., Duval A., Pouwels K.B., Guillemot D., Fernandes J., Huynh B.-T.…Opatowski L. Optimizing COVID-19 surveillance in long-term care facilities: A modelling study. BMC Medicine. 2020;18(1):386. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01866-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachinger J., Olaru I.D., Horner S., Schnitzler P., Heeg K., Denkinger C.M. The potential of SARS-CoV-2 antigen-detection tests in the screening of asymptomatic persons. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2021;27(11):1700.E1–1700.E3. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachinger J., Schirmer M., Täuber N., McMahon S.A., Denkinger C.M. Experiences with opt-in, at-home screening for SARS-CoV-2 at a primary school in Germany: An implementation study. BMJ Paediatrics Open. 2021;5(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2021-001262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. SARS-CoV-2 antigen-detecting rapid diagnostic tests: An implementation guide.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017740 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. WHO emergency use listing for in vitro diagnostics (IVDs) detecting SARS-CoV-2.https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/200922-eul-sars-cov2-product-list Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.