Abstract

Background:

Hospitalizations for drug-use associated endocarditis (DUA-IE) have led to increasing surgical consultation for valve replacement. Cardiothoracic surgeons’ perspectives about the process of decision-making around surgery for people with DUA-IE are largely unknown.

Methods:

This multi-site semi-qualitative study sought to gather the perspectives of cardiothoracic surgeons on initial and repeat valve surgery for people with DUA-IE through purposeful sampling of surgeons at seven hospitals: University of Alabama, Tufts Medical Center, Boston Medical Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, and Rhode Island Hospital-Brown University.

Results:

19 cardiothoracic surgeons (53% acceptance) were interviewed. Perceptions of the drivers of addiction varied as well as approaches to repeat valve surgeries. There were mixed views on multi-disciplinary meetings, though many surgeons expressed an interest in more efficient meetings, and more intensive post-operative and post-hospitalization multi-disciplinary care

Conclusions:

Cardiothoracic surgeons are emotionally and professionally impacted by making decisions about whether to perform valve surgery for people with DUA-IE. The use of efficient, agenda-based multi-disciplinary care teams is an actionable solution to improve cross-disciplinary partnerships and outcomes for people with DUA-IE.

Keywords: endocarditis, surgeons, injection drug use, opioid use disorder

The epidemic of injection drug use in the U.S. has resulted in a doubling of drug use-associated infective endocarditis (DUA-IE) cases over the past ten years.1–4 Co-management of substance use disorders and DUA-IE presents challenges to health care systems. Cardiothoracic (CT) surgeons are frequently involved in the treatment of people with DUA-IE, as professional guidelines have moved towards earlier surgical management of endocarditis.5,6

Decisions to perform valve surgery on patients with DUA-IE are often more controversial than those in patients with IE not related to drug use, especially when the infected valve is prosthetic.7–9 The 2016 American Association of Thoracic Surgery guidelines highlight the complexity of patients with DUA-IE, given “they present with two deadly conditions, the IE and the addiction,” but do not provide further advice on how to approach management decisions in this population.6 About one-fourth of CT surgeons reported that they would perform valve surgery on someone with recurrent DUA-IE, compared with 93% who would operate on a patient with recurrent endocarditis unrelated to drug use.10 Qualitative work with stakeholders caring for patients with DUA-IE, including CT surgeons, identified futility and perceived need for rationing of surgical care as impacting decisions to offer surgery.11

Despite frequently serving a pivotal role in the management of DUA-IE, CT surgeons’ perspectives on treatment of persons with DUA-IE mostly been explored through quantitative surveys.10,12,13 The goal of this semi-qualitative study was to identify themes from CT surgeons on the management of patients with DUA-IE, focusing on the role of multi-disciplinary rounds in caring for people with DUA-IE.

Patients and Methods

This study was conducted between 4/2019–3/2020 at seven hospitals: University of Alabama, Tufts Medical Center (TuftsMC), Boston Medical Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Rhode Island Hospital-Brown University. Study team members contacted all CT surgeons (herein referred to as “surgeons”) through email to request an interview. Each CT surgeon who agreed to participate was included in the study. Participants provided verbal informed consent prior to the interview and could opt out of audio-recording of interviews, in which case the interviewer took notes. Participants were asked their gender and age, but other demographics were withheld to protect privacy. The interview guide was based on a guide previously used to interview a multidisciplinary care team regarding DUA-IE,11 and revised by several co-authors (MP, SK, JB, EE, AS) (Supplement 1). Interviews took 20–30 minutes. Study sites sent de-identified, transcribed interviews to TuftsMC for analysis. After developing a preliminary deductive codebook for a subset of interviews,14 the research team (JZ, ES, JR) coded a subsample of interviews and then revised the codebook to include emergent codes.15 Transcripts were analyzed using Dedoose 6.1.18 The initial list of codes was discussed with other team members (AGW, AR) and then an iterative process continued with team members (ES, JZ, JR, AGW, AR) with clustering and categorization of codes into themes. (Supplement 2). All of the interviews were re-reviewed with a semi-quantitative lens to 28 questions (Supplement 3), with potential coding responses of: Yes, No, Unsure or No Answer.

Results

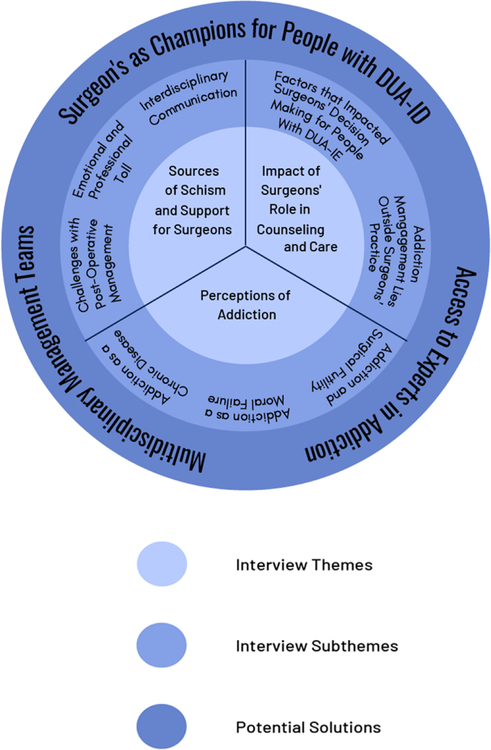

Thirty-six surgeons were approached and 19 (53%) participated. A range of 1–5 (25%−100%) of surgeons at each hospital participated. Participants were mostly white and male. Six surgeons were between the ages of 35–44, seven surgeons were 45–54, four surgeons were >55, and two surgeons did not provide their age. All of the surgeons reported caring for people with DUA-IE with native and prosthetic valve endocarditis. Major themes emerged from participant interviews (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Emergent Themes, Subthemes and Solutions from Interviews with 19 Cardiothoracic Surgeons about Surgical Decision Making for People with Drug-Use Associated Infective Endocarditis.

Perceptions of Addiction

Addiction as a chronic disease

Several surgeons discussed their understanding of addiction as a chronic disease. One surgeon said, “the more and more I treat this disease, I feel it is a chronic disease and can be suppressed but not fully treated.” Another said “these patients are not criminals; they’re actually patients. They’re truly patients with underlying, chronic illness, and it’s so we’ve sort of shifted our thinking about this.” One surgeon compared not providing addiction treatment to people with DUA-IE to “somebody coming in with cancer, taking out their primary tumor, and sending them out without any follow-up for chemotherapy or radiation therapy.”

Addiction as a moral failure

Some surgeons described addiction as self-inflicted. “It’s kind of popular on mainstream media to say that ‘This was generated by the drug companies.’ And yes, there’s fault from the drug companies and physicians and everything but they’ve almost become a scapegoat for the patients to say, ‘Yeah, this is not my fault.’” One surgeon said, “You got to blame the patients. I’ve put 80 percent of it on the patients. They did this to themselves.” One surgeon referenced the “Just Say No” campaign of the 1980s as a powerful educational tool, and said, “Someone couldn’t possibly try heroin and not know that it’s highly addictive, so in some ways it’s kind of their fault.”

Addiction and Surgical Futility

Futility was a recurring theme driving surgical decisions, especially for prosthetic valve endocarditis. One surgeon discussed a young woman with prosthetic valve endocarditis sent to hospice, “That was not a good feeling for a million reasons. You know, because futility is hovering over your head, what am I doing, you know it is going to be a difficult case, you know she failed in her, you know, she reused once already, likely she is going to do it again. Why do I have to get her through a big operation and go back to square one down the road? When is enough?” Several surgeons felt that futility in DUA-IE cases was compounded because a tenable plan for treatment of addiction plan was not in place. One surgeon discussed a conversation with a colleague, “The cardiologist said of course you have to, the patient’s gonna die. I said without adequate treatment for addiction she’s dead anyways, so what’s the point of putting her through another operation.”

Impact of Addiction on Surgeons’ Role in Counseling and Care Decisions

Factors that Impacted Surgeons’ Decision-Making for People with DUA-IE

About two-thirds of surgeons (12/19, 63%) felt the presence of addiction impacted decisions about operating on people with DUA-IE, with one person saying addiction did not impact decision-making (5%), two people unsure (2/19, 10%) and four with no answer (4/19, 21%). About half of surgeons (8/19, 42%) reported that the presence of addiction impacted the type of valve they chose to place in the patient. Most surgeons reflected that their decisions about operating on people with DUA-IE, at least for the first operation, were informed by surgical guidelines the severity of illness. Several surgeons highlighted technical concerns related to scar tissue with re-operations, prosthetic valve degradation, and concerns about people who inject drugs not being able to tolerate anti-coagulation. One surgeon commented “I’d love to have more minimally invasive methods…I’d love to see prosthetic material that doesn’t lend itself to infection.” Age emerged as a factor impacting surgery, with surgeons more less likely to offer surgery to older people. One surgeon said, “At 55 years of age, you’re still using, you have a problem.”

There were heterogeneous views on performing surgery for prosthetic-valve endocarditis, as described in this quote, “Some surgeons won’t operate even upfront if it’s secondary to injection drug use. That’s one extreme. And then there’s the other extreme where a surgeon will say, I don’t care, I’ll do the operation over and over until they’re dead.” Several surgeons referenced colleagues who made “blanket statements” such as a “one-and-done rule” (meaning the patient only gets one operation) or “three strikes and you’re out” (meaning the patient gets three operations.) Prior to offering surgery, some surgeons had their patient sign a contract not to use drugs, and if they used drugs again, “I won’t operate again, because by definition, they’ve broken the contract.” In contrast, however, another surgeon said, “I have never said to a patient that I’m going to do this operation on you but, if you use drugs again, I’m not going to operate on you again. I think that’s just about the worst thing that you can say to somebody. I think it’s malpractice.” One surgeon compared his approach to valve surgeries to managing gunshot trauma, “underprivileged people in bad neighborhoods who flirt with the law a little bit, lawlessness, and they keep getting shot and they keep getting brought into the operating room with gunshot wounds to the abdomen…we never draw a line and say oh we are never going to operate on these people.” Of note, only 2 surgeons (10%) reported hospital guidelines that help them make decisions about valve replacement in people with DUA-IE, and the vast majority 13/19 (63%) said no hospital guidelines existed or had no answer to the question (4/19, 21%). When asked if there were professional society guidelines on operating on people with DUA-IE, 9/19 (47%) of surgeons said that guidelines do not exist, 4/19 surgeons (21%) said they exist, 2/19 surgeons were unsure (10%) and 4/19 had no answer (21%).

Several participants referenced discussing surgical decisions with colleagues as influencing decision making. One surgeon said, “I’ve operated on patients two times, three times, but now I’m moving away from them. My partners are all generally one and done. So that’s kind of where I’m at now.” Another surgeon said “my thought is that the longer you do this, the less you are to operate on IV drugs users.” One surgeon reflected that surgical decisions are “complex” and that variability in practice did not necessarily lead to conflict, “Where one member of the team declines to operate on a patient and I or someone else agrees to operate…I don’t see that as a conflict. This is such a difficult question that I think every person has to answer for themselves… I have never seen a situation where one surgeon says I don’t want to operate and another surgeon gave them a hard time, or told them they were wrong, told them that they were immoral or anything like that.”

Addiction Management Lies Outside Surgeons’ Scope of Practice

18/19 (95%) of surgeons reported access to addiction expert consultation. Surgeons, in general, felt ill-equipped to manage addiction on their own. One said, “We just come in because we have a knife and we’re trying to fix a terminal problem these patients have. We do a good job at it, we get them through, but we, by far, we haven’t cured them.” Surgeons felt the provision of addiction treatment was outside their scope of practice: “I don’t think that it’s my job to necessarily cure the patient of their drug addiction. That’s not what I am. I’m a heart surgeon. I fix heart problems.” One expressed that “All I need to do is to be the bridge to connect them with the right people, but I can’t, I can’t just have a deep, deep discussion.” Another surgeon said, “We should not be in the trenches dealing with these patients. We are the wrong people. We don’t understand addiction disorders. We don’t understand drug abuse…we’re heart surgeons.”

Sources of Schism and Support for Surgeons

Challenges with Post-Operative Management

Surgeons reported feeling unsupported by their colleagues and the healthcare system in the post-surgical treatment of DUA-IE. Several surgeons recounted stories of being listed as their patient’s primary care doctor and feeling burdened with their long-term medical needs One surgeon said, “Everyone who was so hot to trot insisting that the patient have an operation, they’re not there to take care of the patient afterwards. There’s a saying ‘Beware of the courage of the non-combatant.’ You know, people who are not surgeons, they don’t truly understand what it is to do these operations and what it takes to care for them and get them through and that is frustrating. Do we feel supported for caring for these patients? One hundred percent, no.” Another surgeon said “there is a lot of pressure to operate on them and it feels like, as soon as we do, everyone disappears. And..what began as a multidisciplinary approach becomes one service managing surgical complications, managing addiction, managing placement, managing families, um, and we don’t have any of those resources, frankly.”

Emotional and Professional Toll

Several surgeons discussed the emotional and professional toll of caring for people with DUA-IE, including one surgeon who said “You are penalized by the hospital, you are penalized by [professional society] and you make yourself very vulnerable for someone who may have other reasons not to like you to say that this guy’s mortality is high….It does impact my decision. Because yes, I have to take care of the patient, but I have to take care of myself as well.” Another surgeon said, “The thing we worry about, it is not the surgery. We enjoy surgery, it is fun, it gives us great pleasure, it’s the after part where they go back to using and die that is agony and moral agony for us.” Fifty-two percent of surgeons (10/19) reported concerns about getting infected with HIV or hepatitis C virus during the surgery on people with DUA-IE. One surgeon said, “you don’t have the option to say I do not feel comfortable exposing myself to this, I mean I am willing to take a chance when I don’t know a patient has it, but if I have you know a drug addict with a high viral load I don’t have the right paper at least to say I do not feel comfortable operating. “Another surgeon told the story of noticing he had a small injury to his hand one day while walking with his son soon after an intra-operative exposure to hepatitis C, “I went to hold his hand and I felt something wet and I realized it was my blood, and I saw blood on his hand too and I uh… that hit home. I try to hold back when I describe the story, but that was hard.”

Interdisciplinary Communication

Fourteen surgeons (74%) reported positive experiences with multidisciplinary meetings. One stated “I’ve learned a lot more about this patient population, and some of the fears and negative connotations that I’ve, preconceived notions that I’ve brought to the table, about how they’re going to do and how they’re going to recover, um, knowing that there’s a plan in place for recovery…makes me more interested in operating on patients.” One surgeon said, “Many people who may have thought that you are like the cold-hearted surgeon because you just wrote a note that ‘No, I don’t think this person should have an operation.’ Hopefully, they will see that you are actually a human being. They’re the ones that talk about being open minded and all this stuff but sometimes I don’t think they are. So, if they meet you in person and have a discussion maybe they will see your viewpoint too.” One surgeon noted that meetings improved consensus: “Everyone was coming at it from different perspectives and everyone had the patient’s best interest in heart but I don’t think they were seeing what the other teams were seeing. You know, the addiction team most of the time was saying you need to operate on these patients because that is what needs to happen and the surgeons were reluctant because of obvious reasons but what I find very interesting is that more often than not recently everyone is on the same page, or trying to get on the same page.” One surgeon explained, “It’s a team effort…it’s not just on me, that this patient dies… there’s kind of other services to help out. And it takes some of the burden off me as a surgeon.”

Two surgeons reported with neutral views (2/19, 10%), one surgeon reported negative experiences with multidisciplinary groups (5%) and two surgeons did not express any views about multi-disciplinary groups (10%). One surgeon commented, “There’s really nothing they’re going to say to me that impacts what I do, though…There’s a lot of people that try to get involved in these cases. A lot of them don’t really have anything of value to add. I mean, I think when it comes down to it you have a patient, if they have an indication for surgery, you weigh the risks to benefits and then you decide to offer surgery or not.” Another surgeon felt the meetings were too time consuming, “The ultimate decision on whether the patient gets an operation is based on the surgeon, regardless of what the Infectious Disease doctor or cardiologist say. I think when these groups get together I think they spend an hour talking about nothing. You can get to the heart of the matter very quickly and so it would probably be a waste of – you know, there’s not enough hours in a day to sit through an hour-long meeting. I think you can really get to the heart of the matter in terms of what needs to be done in just a few minutes.”

Comment

Surgeons interviewed in this study described leveraging a broad array of strategies to address the complex and ethically challenging care for this patient population. They reported bearing personal and professional burden by operating on patients who they felt may have poor outcomes, and at times felt unsupported by their colleagues and the overall health system.

All surgeons reported having an addiction specialist on staff, an interesting finding in light of one national survey reported that half of the 208 surgeons surveyed did not have access to an addiction specialist.12 Limited knowledge about treating addiction may have contributed to the perception that providing surgery for people with for DUA-IE is futile. Despite these concerns, emerging evidence suggests that medications for opioid use disorder improve mortality and re-hospitalization following infective endocarditis. Increasing recognition of the efficacy of addiction treatment has led clinicians in internal medicine,16 emergency medicine,17 family medicine18, pediatrics19, obstetrics20 and infectious diseases among others to learn and integrate addiction treatment into their practices.21,22 There has been a national push to encourage infectious diseases doctors to learn about substance use disorder and provide medications for opioid use disorder.23 Similarly, there may be cardiothoracic surgeons who have a specific interest in DUA-IE—“champions” in the field—who could advocate for professional societies to include conference sessions specifically on the clinical and ethical issues that arise in people with DUA-IE.

Surgeons reported mostly positive experiences with multidisciplinary meetings as places where they learned about addiction, expressed their professional opinion, and shared the responsibility for the patient. In-person, case based dialogue may alleviate issues of interprofessional disagreements or a lack of clarity regarding the rationale for surgical decision-making. These dialogues help set consistent standards for treatment of DUA-IE across a hospital, especially if conversations include surgeons who may have different views on the same case. In response to feeling unsupported in the post-operative periods, multidisciplinary meetings should include discussions about post-surgical management of patients, including post-hospitalization clinical updates. Sharing experiences of people with DUA-IE who are in sustained recovery may be one way to demonstrate that treatment for addiction works.

Surgeons in our study expressed their need for empathy, collegiality, and recognition of the difficult decisions they are asked to make. As an potential antidote to this isolation and the frustration it can engender, multidisciplinary groups may assist in sharing of tasks, and source varied medical, surgical, and addiction expertise. Surveys with clinicians at the University of Michigan found that 85% of respondents felt that endocarditis interdisciplinary meetings improved patient care.24 Several sites have initiated multi-disciplinary meetings for endocarditis treatment.25–29 Gathering feedback on the pace, structure, frequency, and topics covered in multi-disciplinary meetings may help to improve the efficiency and encourage participation.

There are several limitations to this study. It is possible that surgeons who felt that their opinions were potentially polarizing or unsupported opted not to participate. In our interviews with the nineteen surgeons, we found a broad spectrum of views about DUA-IE, and feel that we reached thematic saturation.30 We did not ask questions about the timing of surgical consultation and how this impacts surgical decisions. All surgeons worked at academic centers with addiction medicine specialists, which serve patient populations that may differ from the community or private hospital setting. Social desirability bias may have influenced the interviews in cases where the interviewer was known to the surgeon, although this dynamic was infrequent. The participants were mostly male, although this is consistent with the overall CT surgery workforce which is 95% male.31 As such, we did not report the age, gender breakdown, or additional details on race/ethnicity and geographic location to protect participant anonymity. Although two surgeons are included as authors on this study (KRB and JB), most authors are infectious diseases or internal medicine trained, and our analysis is likely influenced by our medical training. Despite these noted limitations, this study is the first multi-site qualitative study that has explored surgeons’ perspectives on treating DUA-IE.

Conclusions

The experiences and voices of CT surgeons should be included in the design and implementation of care pathways and professional guidelines for DUA-IE. To improve the quality of care delivered to persons with DUA-IE, interprofessional communication and partnerships between surgeons and addiction experts is needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING: 1KL2TR002545-01, K08HS026008-01A (AGW); K23DA049946, T32AI070114 (AJS), P30AI42853 (CGB); P20GM125507 (CGB); R25DA037190 (AGW, JAB, CGB); R01MH124633-01 (EE); 1H79SP082270-01 (EE), K01DA051684 and DP2DA051864 (JAB)

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: Dr. Kimmel previously received consulting fees from Abt Associates for his work with Massachusetts DPH

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Wurcel AG, Anderson JE, Chui KKH, et al. Increasing Infectious Endocarditis Admissions Among Young People Who Inject Drugs. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(3):ofw157–ofw157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim JB, Ejiofor JI, Yammine M, et al. Surgical outcomes of infective endocarditis among intravenous drug users. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2016;152(3):832–841.e831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schranz A, Fleischauer A, Chu V, Wu L, Rosen D. Trends in Drug Use-Associated Infective Endocarditis and Heart Valve Surgery, 2007 to 2017: A Study of Statewide Discharge Data. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(1):31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geirsson A, Schranz A, Jawitz O, et al. The Evolving Burden of Drug Use Associated Infective Endocarditis in the United States. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;110(4):1185–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pettersson G, Hussain ST.. Current AATS guidelines on surgical treatment of infective endocarditis.. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;8(6):630–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pettersson GB, Coselli JS, Pettersson GB, et al. 2016 The American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) consensus guidelines: Surgical treatment of infective endocarditis: Executive summary. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2017;153(6):1241–1258.e1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hull SC, Jadbabaie F. When Is Enough Enough? The Dilemma of Valve Replacement in a Recidivist Intravenous Drug User. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2014;97(5):1486–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jamil M, Sultan I, Gleason T, et al. Infective endocarditis: trends, surgical outcomes, and controversies. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11(11):4875–4885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiMaio JM, Salerno TA, Bernstein R, Araujo K, Ricci M, RM S. Ethical obligation of surgeons to noncompliant patients: can a surgeon refuse to operate on an intravenous drug-abusing patient with recurrent aortic valve prosthesis infection? Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguemeni Tiako MJ, Mszar R, Brooks C 2nd, et al. Cardiac Surgeons’ Treatment Approaches for Infective Endocarditis Based on Patients’ Substance Use History. Seminars in thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayden M, Moore Amber. Attitudes and Approaches Towards Repeat Valve Surgery in Recurrent Injection Drug Use-associated Infective Endocarditis: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguemeni Tiako MJ, Mszar Reed, Brooks Cornell II, Mahmood Bin, Usman Syed, Mori Makoto, Vallabhajosyula Prashanth, Geirsson Arnar, Weimer Melissa B. Cardiac Surgeons’ Practices and Attitudes Towards Addiction Care for Patients with Substance Use Disorder. Substance Abuse. 2021;In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.An KR, Luc JGY, Tam DY, et al. Infective Endocarditis Secondary to Injection Drug Use: A Survey of Canadian Cardiac Surgeons. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho DYF, Ho RTH, Ng SM. The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed.). Cult Psychol. 2007;13(3):377–383. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park TW, Friedmann PD. Medications for addiction treatment: an opportunity for prescribing clinicians to facilitate remission from alcohol and opioid use disorders. Rhode Island medical journal (2013). 2014;97(10):20–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Onofrio G, O’Connor P, Pantalon M, et al. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1636–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deyo-Svendsen M, Cabrera Svendsen M, Walker J, Hodges A, Oldfather R, Mansukhani M. Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in a Rural Family Medicine Practice. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carney B, Hadland S, Bagley S. Medication Treatment of Adolescent Opioid Use Disorder in Primary Care. Pediatrics in review. 2018;39(1):43–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klaman S, Isaacs K, Leopold A, et al. Treating Women Who Are Pregnant and Parenting for Opioid Use Disorder and the Concurrent Care of Their Infants and Children: Literature Review to Support National Guidance. Journal of addiction medicine. 2017;11(3):178–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rapoport AB CF. R. Stretching the Scope - Becoming Frontline Addiction-Medicine Providers. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(8):705–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rapoport AB, Fischer LS, Santibanez S, Beekmann SE, Polgreen PM, Rowley CF. Infectious Diseases Physicians’ Perspectives Regarding Injection Drug Use and Related Infections, United States, 2017. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(7):ofy132–ofy132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serota DP, Barocas JA, Springer SA. Infectious Complications of Addiction: A Call for a New Subspecialty Within Infectious Diseases. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2020;70(5):968–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Dalati S, Khurana I, Soper N ea. Physician perceptions of a multidisciplinary endocarditis team. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;39(4):735–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vyas DA, Marinacci L, Sundt T, et al. 709. Multidisciplinary Drug Use Endocarditis Team (DUET): Results From an Academic Center Cohort. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(Supplement_1):S405–S407. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gibbons E, Huang G, Aldea G, Koomalsingh K, Klein JW, Dhanireddy S, Harrington R. A Multidisciplinary Pathway for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Endocarditis. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2020;19(4):187–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Regunath H, Vasudevan Archana, Vyas Kapil, Li-Chien Chen, Patil Sachin, Terhune Jane, and Whitt Stevan P. A Quality Improvement Initiative: Developing a Multi-Disciplinary Team for Infective Endocarditis. Missouri Medicine. 2019;116(4). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weimer MB, Falker CG, Seval N, et al. The Need for Multidisciplinary Hospital Teams for Injection Drug Use-Related Infective Endocarditis. J Addict Med. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paras ML WS, Bearnot BB, Sundt TM, Marinacci L, Dudzinski DN, Vyas DA, Wakeman SE, Jasaar AS. Multidisciplinary Team Approach to Confront the Challenge of Drug Use-Associated Infective Endocarditis. Journal of Thoracis and Cardiovascular Surgery 2021;Accepted, In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC. Code Saturation Versus Meaning Saturation: How Many Interviews Are Enough? Qual Health Res. 2017;27(4):591–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stephens EH, Robich Michael P., Walters Dustin M., DeNino Walter F., Aftab Muhammad, Tchantchaleishvili Vakhtang, Eilers Amanda L., Rice Robert D., Goldstone Andrew B., Shlestad Ryan C., Malas Tarek, Cevasco Marisa, Gillaspie Erin A., Fiedler Amy G., LaPar Damien J., and Shah Asad A.. Gender and Cardiothoracic Surgery Training: Specialty Interests, Satisfaction, and Career Pathways. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;102:200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.