Abstract

Background

Artificial intelligence has far surpassed previous related technologies in image recognition and is increasingly used in medical image analysis. We aimed to explore the diagnostic accuracy of the models based on deep learning or radiomics for lung cancer staging.

Methods

Studies were systematically reviewed using literature searches from PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Wanfang Database, according to PRISMA guidelines. Studies about the diagnostic accuracy of radiomics and deep learning, including the identifications of lung cancer, tumor types, malignant lung nodules and lymph node metastase, were included. After identifying the articles, the methodological quality was assessed using the QUADAS-2 checklist. We extracted the characteristic of each study; the sensitivity, specificity, and AUROC for lung cancer diagnosis were summarized for subgroup analysis.

Results

The systematic review identified 19 eligible studies, of which 14 used radiomics models and 5 used deep learning models. The pooled AUROC of 7 studies to determine whether patients had lung cancer was 0.83 (95% CI 0.78–0.88). The pooled AUROC of 9 studies to determine whether patients had NSCLC was 0.78 (95% CI 0.73–0.83). The pooled AUROC of the 6 studies that determined patients had malignant lung nodules was 0.79 (95% CI 0.77–0.82). The pooled AUROC of the other 6 studies that determined whether patients had lymph node metastases was 0.74 (95% CI 0.66–0.82).

Conclusion

The models based on deep learning or radiomics have the potential to improve diagnostic accuracy for lung cancer staging.

Systematic Review Registration

https://inplasy.com/inplasy-2022-3-0167/, identifier: INPLASY202230167.

Keywords: lung cancer, deep learning, radiomics, diagnostic accuracy, lymph node metastasis, meta-analysis

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common malignancies globally and the leading cause of cancer-related death in the world. Its morbidity and cancer-related mortality rank first among malignant tumors. There are ~2.2 million new cases and about 1.5 million deaths worldwide (1).

Radiomics and deep learning, as an innovative means to characterize lung lesions, can be applied to generate descriptive data, build predictive model, and correlate quantitative image features with phenotypes or gene-protein signatures, thus aiding in cancer detection, diagnosis, staging, treatment response prediction, and prognosis assessment and playing an increasingly important role in clinical decision-making, especially the management of malignant tumors (2).

Lung cancer staging is usually done by radiologists evaluating CT images of patients with lung cancer. The accuracy of diagnosis is affected by various factors, such as device performance, standardized imaging protocols, the experience of the reporting radiologist, and patient-specific factors. While radiomics involves using advanced computational algorithms to extract large numbers of researcher-defined features from images for defining related lung lesions, studies suggesting that deep learning algorithms can identify a more nuanced approach that eschews traditional radiology and statistical methods for cancer staging were extensively reported (3–6). Deep learning, as a new research direction in the field of machine learning (ML), is applied to learn the inherent laws and representation levels of sample data for feature recognition and model building (7). In the last decade, radiomics models and deep learning have made meaningful contributions to medical imaging diagnosis and related individual medicine (8).

This study aimed to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of published data on lung cancer diagnosis and the diagnostic accuracy of deep learning algorithms and radiomics models for lung cancer staging.

Methods

Search Strategy

This study followed the Preferred Reporting Item of the Guidelines for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA), and selection criteria, data extraction, and data analysis were determined before study initiation. Any eligible studies in the PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Wanfang Database will be searched by Cancer, Radiomics, Deep Learning, Lung Cancer, and more. The search method is shown in Table 1. Search terms such as “radiomics,” “deep learning,” “lymph node metastasis,” “non-small cell lung cancer,” “malignant lung nodules,” and “diagnostic accuracy.” Use the Boolean operator AND to combine the results of different queries. We also manually searched the reference lists of included studies to identify any relevant articles. Both English and Chinese articles are considered eligible.

Table 1.

Search strategy.

| Sources | Search in | MeSH terms | Limits | Search results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Web of science | Search manager | (“deep learning” OR “convolutional neural network” OR “machine learning” OR “radiomics” OR “radiomic”) AND (“CT” OR “MRI”) AND (“Lymph node” OR “lymph node metastasis” OR “Benign and malignant pulmonary nodules”)AND (“lung cancer” OR “non-small cell lung cancer” OR “NSCLC”) | None | 11 |

| PubMed, (MEDLINE) | N/A | (“deep learning” OR “convolutional neural network” OR “machine learning” OR “radiomics” OR “radiomic”) AND (“CT” OR “MRI”) AND (“Lymph node” OR “lymph node metastasis” OR “benign and malignant pulmonary nodules”) AND (“lung cancer” OR “non-small cell lung cancer” OR “NSCLC”) | None | 30 |

| EMBASE | Quick search | (‘deep learning'/exp OR “deep learning” OR “machine learning”/exp OR “machine learning” OR “radiomics”/exp OR “radiomics” OR “radiomic”) AND (“ct”/exp OR “ct” OR “mri”/exp OR “mri”) AND (“lymph node”/exp OR “lymph node” OR “lymph node metastasis”/exp OR “lymph node metastasis” OR “benign and malignant pulmonary nodules”) AND (“lung cancer”/exp OR “non-small cell lung cancer” OR “NSCLC”) | None | 56 |

| Wanfang database | N/A | (“deep learning” OR “machine learning” OR “radiomics” OR “radiomic”) AND (“CT” OR “MRI”) AND (“Lymph node” OR “lymph node metastasis”) AND (“lung cancer” OR “NSCLC”) | None | 5 |

Study Selection

We selected publications for review if they met several of the following inclusion criteria: (1) patients with pathologically diagnosed lung cancer were included in the study; (2) radiomics or deep learning algorithms applied to lung cancer staging were evaluated. Exclusion criteria included: (1) informal publication types (e.g., reviews, letters to the editor, editorials, conference abstracts); (2) only focus on research on image segmentation or image feature extraction methods; (3) animal studies. After the removal of duplicates, titles and abstracts were identified by two independent reviewers using the Covidence systematic review software. Any disagreements will be resolved by consensus by arbitration by a third author.

Data Extraction

We reviewed data from selected primary studies using standardized forms, and two reviewers independently extracted data from each eligible study. Data extraction for each study included first author, country, year of publication, type of AI model, number of patients, patient characteristics (mean/median age, gender), type of malignancy, benign and malignant pulmonary nodules, lymph node metastasis. In addition, we extracted the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), along with sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, etc., for data processing and forest map production. The primary endpoint of this systematic review was AUROC.

Quality Assessment

Two independent reviewers will initially assess the risk of bias. A third reviewer will then review each study using the Quality Assessment of Studies for Diagnostic Accuracy (QUADAS-2) guidelines. The QUADAS-2 tool can assign a risk of bias rating of “low,” “high,” or “uncertain” based on the answer to “yes,” “no,” or “uncertain” to the relevant flag questions included in each section. For example, if the answer to all the landmark questions in a range is “yes,” then it can be rated as low risk of bias; if all the informational questions are answered “no,” then the risk of bias is rated as “high” (9). We summarized the risk of bias in individual studies in a narrative summary during the systematic review phase.

Statistical Analysis

The accuracy measures for this diagnostic meta-analysis included pooled sensitivity, pooled specificity, and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Missing data is calculated using the formula in Table 2. At the same time, AUROC was calculated; an AUROC value close to 1.0 indicates that the test can discriminate almost perfectly, while an AUROC value close to 0.5 means poor discrimination (10, 11). The discordance index (I2) was used (12). Heterogeneity was assessed as low, medium, and high, with upper limits for I2 of 25, 50, and 75%, respectively. A forest plot was drawn to show the AUROC estimates relative to the summary pooled estimates for each study. In addition, we will draw a funnel plot to assess publication bias more intuitively. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA V16.0 software.

Table 2.

Formulas.

| Measure | Formula |

|---|---|

| Sensitivity | |

| Specificity | |

| Accuracy | |

| PPV | |

| NPV | |

| SE | |

| 95% Confidence interval | bestestimate +/− (1.96) * (SE) |

P, condition positive; N, condition negative; FN, false negative; FP, false positive; TN, true negative and TP, true positive; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; Upper limit, upper limit of confidence interval; Lower limit, lower limit of confidence interval; SE, standard error.

Results

Study Selection

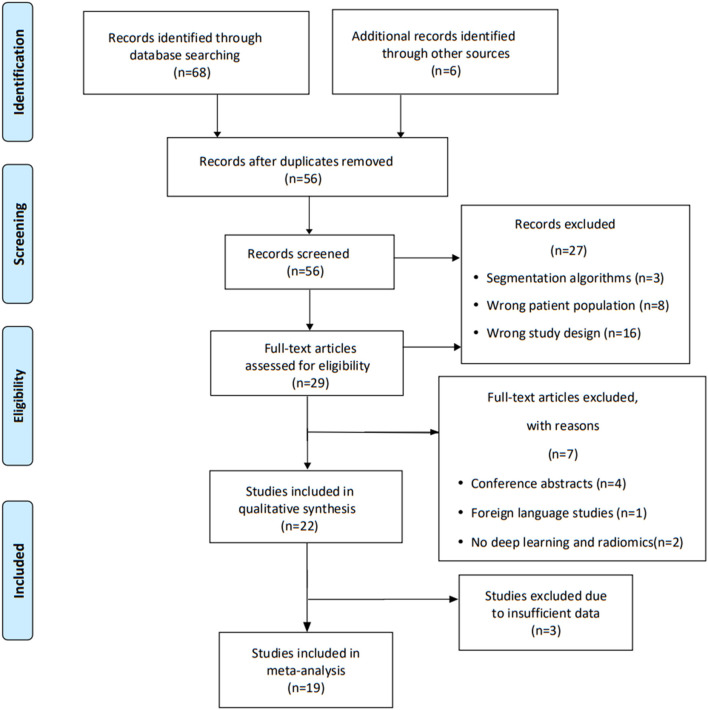

Our search identified 74 studies, with 56 screened after removing duplicates. Of these, 27 did not meet the inclusion criteria based on title and abstract. The remaining 29 full manuscripts were individually assessed, and, finally, 22 studies were eligible and included in our systematic review. Of these, 19 papers were available for meta-analysis, and five articles were excluded because of their insufficient data information. We outline the study selection process for review using the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart outlining the selection of studies for review.

Study Characteristics

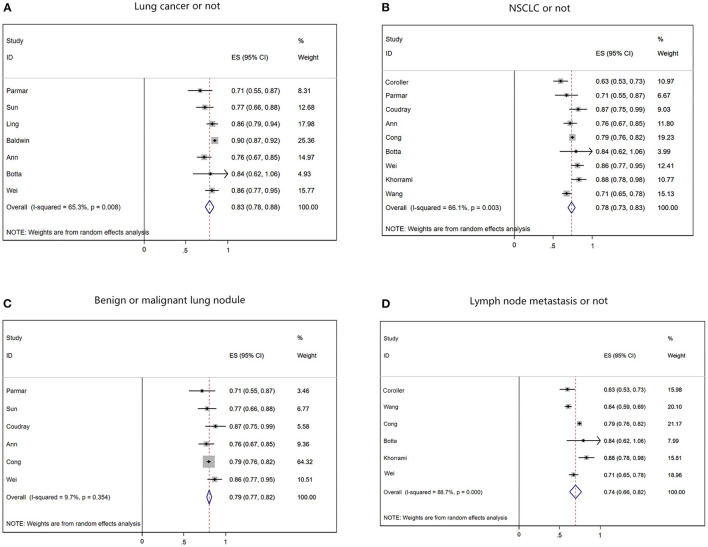

Of the 19 included studies, 14 had sufficient data for a meta-analysis of AUROC (Figure 2). Regarding study design, 17 studies were retrospective, and two were prospective. Sixteen studies were single-center, and the other three were multicenter. Most of the patients are male, and the median age of 63 years (24–93 years) [Table 3 (13–31)]. The malignancy type in twelve studies was NSCLC, and the malignancy type in the remaining studies was lung cancer. Seven studies used the diagnostic output per patient, and eight studies used the lymph node diagnostic output per node for metastases. While seven studies used post-operative pathology reports as reference standards, 11 used radiology reports.

Figure 2.

Summary of forest plots for different classifications. (A) The forest plot of determine if a patient has lung cancer. (B) The forest plot of determining whether the cancer type is NSCLC. (C) The forest plot of predicting benign and malignant pulmonary nodules. (D) The forest plot of predicting lymph node metastasis in lung cancer.

Table 3.

Selected characteristics of included studies.

| References | Country | Year | Study design |

Patients (% female patients) |

Sample size for diagnostic accuracy | Mean or median age (SD; range), years | Imaging modality | Type of malignancy | AI model (Per-patient/per-node diagnostic output) | Reference standard | Classification criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coroller et al. (13) | USA | 2016 | Retrospective single-center | 85 (65%) | – | 60.3 | CT | NSCLC | Radiomics (per-patient) | Radiology | B D |

| Parmar et al. (14) | USA | 2018 | Retrospective single-center | 1,194 | – | 68.3 (32–93) | CT | NSCLC | Deep learning (per-patient) | Pathology | A B C |

| Sun et al. (15) | China | 2019 | Retrospective single-center | 385 (68%) | 201 | 53.1 (±12.2) | CT | Lung Cancer | Radiomics (per-patient) | Radiology | A C |

| Ling et al. (16) | China | 2019 | Retrospective multi-center | 229 (31.5%) | 74 | 64 (59–81) | CT | Lung Cancer | Radiomics (per-patient) | Radiology | A |

| Coudray et al. (17) | USA | 2018 | Retrospective single-center | 1,176 | 459 | 61 (51.3–72.8) | CT | NSCLC | Deep learning (per-patient) | Radiology | B C |

| Xu et al. (18) | China | 2019 | Retrospective single-center | 179 (52.8%) | – | 63 (32–93) | CT | NSCLC | Deep learning (per-patient) | Pathology | B D |

| Baldwin et al. (19) | UK | 2020 | Retrospective single-center | 1,337 | 328 | – | CT | Lung Cancer | Deep learning (per-patient) | – | A |

| Schroers et al. (20) | Germany | 2019 | Retrospective single-center | 82 (38%) | 50 | 61.5 (±5.0) | MRI | Lung Cancer | Radiomics (per-patient) | Pathology | A C |

| Wang et al. (21) | China | 2019 | Retrospective single-center | 249 (39.8%) | – | 61.4 (±8.96) | CT | Lung Cancer | Deep learning (per-patient) | Radiology | D |

| Leleu et al. (22) | France | 2020 | Retrospective single-center | 215 (39%) | 72 | 58.6 (±10.3) | CT | Lung Cancer | Radiomics (per-patient) | Pathology | A |

| Ann et al. (23) | USA | 2019 | Prospective multi-center | 262 | 48 | – | CT | NSCLC | Radiomics (per-patient) | Pathology | A B C |

| Cong et al. (24) | China | 2020 | Retrospective single-center | 411 (50.4%) | 141 | 59.62 (24–84) | CT | NSCLC | Radiomics (per-patient) | Radiology | B C D |

| Botta et al. (25) | Italy | 2020 | Retrospective single-center | 270 (38%) | – | 67.4 (61.0–72.6) | CT | NSCLC | Radiomics (per-patient) | Radiology | A B D |

| Wei et al. (26) | USA | 2020 | Retrospective multi-center | 146 (39.7%) | – | 65.72 (± 12.88) | PET/CT | NSCLC | Radiomics (per-node) | Radiology | A B C |

| Khorrami et al. (27) | USA | 2019 | Retrospective single-center | 112 | – | – | CT | NSCLC | Radiomics (per-patient) | Pathology | B D |

| Kirienko et al. (28) | Italy | 2021 | Retrospective single-center | 149 (37.6%) | 73 | 70 (41–84) | PET/CT | Lung Cancer | Radiomics (per-node) | Radiology | B C |

| Rossi et al. (29) | Italy | 2020 | Retrospective single-center | 109 | – | – | CT | NSCLC | Radiomics (per-patient) | Radiology | A B |

| Chai et al. (30) | China | 2021 | Retrospective single-center | 198 (54%) | 402 | 58.1 (± 8.5) | CT | NSCLC | Radiomics (per-node) | Pathology | A B D |

| Wang et al. (31) | China | 2019 | Retrospective single-center | 717 | 386 | — | CT | NSCLC | Radiomics (per-node) | Radiology | B D |

A, Determine whether the patient has lung cancer; B, Determine whether the patient has non-small cell lung cancer; C, Determine whether the patient has malignant lung nodule; D, Determine whether the patient has lymph node metastasis.

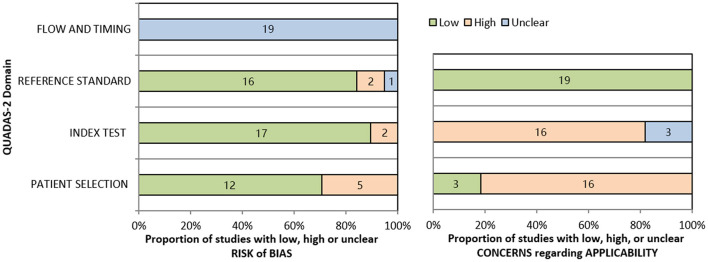

Quality Assessment

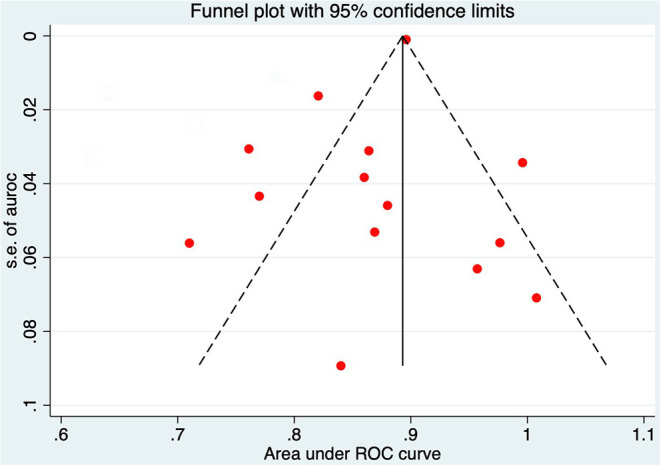

According to the QUADAS-2 tool, the summary of this study's assessment is shown in Figure 3. The risk of bias in patient selection was low in 12 (74%) studies and high in 5 (26%) studies. The risk of bias for the index test was high in 2 studies (10%) and low in 17 studies (90%). The risk of bias for the reference standard test was low in 16 studies (85%), high in 2 studies (10%), and unclear in 1 study (5%). Process and timing made the risk of bias unclear for all 19 studies. Table 4 shown individual evaluation of the risk of bias and applicability. Overall suitability issues are low. To assess the publication bias of the studies, a funnel plot was constructed (Figure 4). The shape of the funnel plot revealed asymmetry in the included studies, showing study heterogeneity.

Figure 3.

Summary of QUADAS-2 assessments of included studies.

Table 4.

Quality assessment.

| Source | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | Flow and timing | Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | |||||

| Was the statistical management adequate? | Were the inclusion/exclusion criteria specified? | Was the type of study (retrospective or prospective) specified? | Were the imaging acquisition protocol and the segmentation method(s) detailed? | Was the image processing approach detailed? | Was the validation independent (i.e., no internal)? | Was the reference standard adequate? | Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | ||||

| Chetan et al. (1) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Parmar et al. (2) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sun et al. (3) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ling et al. (4) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Coudray et al. (5) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Xu et al. (6) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Baldwin et al. (7) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Schroers et al. (8) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Wang et al. (9) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Leleu et al. (10) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ann et al. (11) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Cong et al. (12) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Botta et al. (13) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Botta et al. (13) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Wei et al. (14) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Khorrami et al. (15) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kirienko et al. (16) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Rossi et al. (17) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Chai et al. (18) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Wang et al. (19) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

Figure 4.

Funnel plot of the area under the receiver operating characteristic in 14 studies.

Diagnostic Accuracy

Of the 19 studies eligible for quantitative analysis, 14 used radiomics and 5 used deep learning. For each outcome, on a per-patient basis, pooled estimates including specificity, sensitivity, and AUROC were generated with 95% confidence intervals. The categorized data extraction for each study report is shown in Table 5. The type of lung cancer, malignant lung nodules, lymph node metastases, and deep learning or radiomics models discussed in each study were considered.

Table 5.

Summary of AUROC for each study.

| References | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Accuracy, % | AUROC | 95%CI | Standard error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coroller et al. (13) | – | – | – | 0.630 | 0.583–0.713 | 0.0331 |

| Parmar et al. (14) | 82.4 | 73.1 | 83.5 | 0.710 | 0.60–0.82 | 0.0561 |

| Sun et al. (15) | – | – | – | 0.770 | 0.69–0.86 | 0.0434 |

| Ling et al. (16) | – | – | – | 0.864 | 0.782–0.904 | 0.0311 |

| Coudray et al. (17) | 89.0 | 93.0 | 83.3 | 0.869 | 0.753–0.961 | 0.0531 |

| Xu et al. (18) | – | – | 63.5 | 0.670 | – | – |

| Baldwin et al. (19) | 99.57 | 28.03 | 40.01 | 0.896 | 0.876–0.915 | 0.0010 |

| Schroers et al. (20) | 86.95 | 93.25 | 88.89 | – | – | – |

| Wang et al. (21) | 64.04 | 58.97 | 61.47 | 0.640 | 0.61–0.67 | 0.0153 |

| Leleu et al. (22) | – | – | 72.6 | – | – | – |

| Ann et al. (23) | 79.9 | 75.2 | 65.8 | 0.761 | 0.59–0.71 | 0.0306 |

| Cong et al. (24) | 72.97 | 63.33 | 55.22 | 0.790 | 0.77–0.81 | 0.0102 |

| Botta et al. (25) | – | – | – | 0.840 | 0.63–0.98 | 0.0893 |

| Wei et al. (26) | 54.16 | 55.56 | 63.64 | 0.860 | 0.79–0.94 | 0.0383 |

| Khorrami et al. (27) | 61.34 | 57.16 | 63.81 | 0.880 | 0.79–0.97 | 0.0459 |

| Kirienko et al. (28) | 85.7 | 88.2 | 93.3 | – | – | – |

| Rossi et al. (29) | 100.0 | 66.7 | 85.7 | 0.850 | – | – |

| Chai et al. (30) | – | – | 95.3 | – | – | – |

| Wang et al. (31) | – | – | 72.4 | 0.712 | 0.678–0.770 | 0.0235 |

The data from radiomics models showed high heterogeneity, except for AUROC and the sensitivity of each node. After removing the literature with insufficient data, the pooled AUROC of the 7 studies determining whether a patient had lung cancer was 0.83 (95% CI 0.78–0.88; Figure 2A), and the pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.838 and 0.653, respectively, indicating high heterogeneity (I2 = 65.3%, p = 0.008). For the 9 NSCLC studies that currently represent ~85% of lung cancer, the pooled AUROC of radiomics was 0.78 (95% CI 0.73–0.83; Figure 2B), and the pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.782 and 0.715, respectively, with higher heterogeneity (I2 = 66.1%, p = 0.003). Among the six studies predicting benign or malignant pulmonary nodules, the pooled AUROC of radiomics was 0.79 (95% CI 0.77–0.82; Figure 2C), and the pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.787 and 0.774, respectively, with heterogeneity relatively low (I2 = 9.7%, p = 0.354). Among the 6 studies that predicted the accuracy of LNM in lung cancer patients, the pooled AUROC of radiomics was 0.74 (95% CI 0.66–0.82; Figure 2D), and the pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.661 and 0.598, respectively, with heterogeneity relatively high (I2 = 88.7%, p = 0.000).

Discussion

During the diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer, many imaging data, such as CT, MRI, and PET, are generated. Doctors usually subjectively evaluate these data based on experience and make treatment plans (32). However, the features that doctors can observe from the image data with the naked eye are limited, and the potential of the image data is often not fully realized. Over the years, many researchers have tried to use complex mathematical and statistical algorithms to extract quantitative information that is hard to observe, even predicting cancer progression (33–35).

With the development of artificial intelligence technology, radiomics has emerged as the times require, using machine learning algorithms to mine high-throughput features from medical images and conduct modeling analysis. Increasing evidence shows that radiomics can be used for quantitative characterization of tumors for tasks such as disease diagnosis, treatment planning, and prognosis, which constitutes an important research direction for artificial intelligence technology in medical applications (36, 37). Radiomics is an emerging and rapidly developing field that integrates knowledge from radiology, oncology, and computer science and is an interdisciplinary subject that emphasizes the integration of medicine and engineering (38). With the rise of deep learning technology in recent years, the need for high precision and high stability in lung cancer staging has become more and more urgent (39).

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to summarize the diagnostic accuracy of deep learning and radiomics involving in lung cancer staging. We provided summarized data in this field and compared the identification effectiveness of lung cancer, tumor types, malignant lung nodules and lymph node metastase. In this article, the included studies mainly used radiomics (n = 14) rather than deep learning methods (n = 5). Of the five deep learning models, two were developed using transfer learning and three were developed using convolutional neural networks (CNN). Part of the reason there are relatively few deep learning models is that deep learning techniques are relatively new and prone to bias. The difference in the number of studies of the two AI models will lead to a significant deviation in the data ratio, affecting the ability comparison of the two models. Furthermore, most studies are retrospective in design, there are few prospective deep learning studies in lung cancer medical imaging staging, and most studies lack data and code availability. At the same time, most studies are single-center and use internal validation or resampling methods (cross-validation). However, internal validation tends to overestimate AUROC due to the lack of generality of the models, limiting the integration of AI models into clinical settings (40). Therefore, predictive models validated externally by using images from different hospitals are needed to create reliable estimates of the performance levels of other sites (41).

This systematic review performed a statistical assessment of pooled data collected from 19 studies. However, our findings must take into account some limitations. First, while comprehensive, our search may have missed some studies that could have been included. Second, we calculated estimates of diagnostic performance using limited data as several studies reported incomplete data. Third, there may be geographic bias because the included studies were from geographically different quantitative distributions. Finally, the type of scanner used for diagnosis, the imaging protocol, and the criteria for lung cancer staging may affect the accuracy of the results. In the future, the clinical benefit of diagnostic lung cancer staging models must be rigorously evaluated against current diagnostic criteria, as not all models are applicable in clinical practice (42, 43). Under the current hot spot of artificial intelligence development, more and more deep learning studies have shown that deep learning big data extracted from patients' medical images can have good clinical application value in tumor staging of patients. Therefore, we can combine deep learning features to establish a radiomics combined with deep learning diagnostic model, so that the accuracy of lung cancer staging diagnosis of patients can be improved.

Conclusion

The models based on deep learning or radiomics have the potential to improve diagnostic accuracy in the pathological staging of lung cancer with the purpose of providing individualized preoperative non-invasive auxiliary prediction means for clinicians and realizing valuable prediction for patients to obtain better treatment strategy. Future studies are welcomed to use standardized radiomics features, more robust tools of feature selection and model development to further improve the diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence in lung cancer staging.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

XZ and WH conceptualized the study. BH, YH, and MR collected the data. XZ, BH, and WH drafted the initial manuscript. ZC, ZZ, JM, LO, HC, and HG reviewed the included articles. YH and WH conducted the analyses. XZ, TL, and GL reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Chengdu Science and Technology Program, Grant no. 2021007 and Sichuan Science and technology plan, Grant no. 2018JY0356.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CT

Computer tomography

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- AI

Artificial intelligence

- ML

machine learning

- LNM

lymph node metastasis

- QUADAS-2

Quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies tool 2

- AUROC

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2018) 68:394–424. 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hosny A, Parmar C, Quackenbush J, Schwartz LH, Aerts HJWL. Artificial intelligence in radiology. Nat Rev Cancer. (2018) 18:500–10. 10.1038/s41568-018-0016-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lambin P, Rios-Velazquez E, Leijenaar R, Carvalho S, van Stiphout RG, Granton P, et al. Radiomics: extracting more information from medical images using advanced feature analysis. Eur J Cancer. (2012) 48:441–6. 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.11.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar V, Gu Y, Basu S, Berglund A, Eschrich SA, Schabath MB, et al. Radiomics: the process and the challenges. Magn Reson Imaging. (2012) 30:1234–48. 10.1016/j.mri.2012.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang Y, Liu Z, He L, Chen X, Pan D, Ma Z, et al. Radiomics signature: a potential biomarker for the prediction of disease-free survival in early-stage (I or II) non-small cell lung cancer. Radiology. (2016) 281:947–57. 10.1148/radiol.2016152234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang YQ, Liang CH, He L, Tian J, Liang CS, Chen X, et al. Development and validation of a radiomics nomogram for preoperative prediction of lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2016) 34:2157–64. 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.9128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lundervold AS, Lundervold A. An overview of deep learning in medical imaging focusing on MRI. Z Med Phys. (2019) 29:102–27. 10.1016/j.zemedi.2018.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benjamens S, Dhunnoo P, Mesko B. The state of artificial intelligence-based FDA-approved medical devices and algorithms: an online database. NPJ Digit Med. (2020) 3:118. 10.1038/s41746-020-00324-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouwmeester W, Zuithoff NP, Mallett S, Geerlings MI, Vergouwe Y, Steyerberg EW, et al. Reporting and methods in clinical prediction research: a systematic review. PLoS Med. (2012) 9:1–12. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. (1959) 22:719–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. (1986) 7:177–88. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. (2003) 327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coroller TP, Agrawal V, Narayan V, Hou Y, Grossmann P, Lee SW, et al. Radiomic phenotype features predict pathological response in non-small cell lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. (2016) 119:480–6 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hosny A, Parmar C, Coroller TP, Grossmann P, Zeleznik R, Kumar A, et al. Deep learning for lung cancer prognostication: a retrospective multi-cohort radiomics study. PLoS Med. (2018) 15:e1002711. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun Y, Li C, Jin L, Gao P, Zhao W, Ma W, et al. Radiomics for lung adenocarcinoma manifesting as pure ground-glass nodules: invasive prediction. Eur Radiol. (2020) 30:3650–9. 10.1007/s00330-020-06776-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.E L, Lu L, Li L, Yang H, Schwartz LH, Zhao B. Radiomics for classifying histological subtypes of lung cancer based on multiphasic contrast-enhanced computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. (2019) 43:300–6. 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coudray N, Ocampo PS, Sakellaropoulos T, Narula N, Snuderl M, Fenyö D, et al. Classification and mutation prediction from non-small cell lung cancer histopathology images using deep learning. Nat Med. (2018) 24:1559–67. 10.1038/s41591-018-0177-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu Y, Hosny A, Zeleznik R, Parmar C, Coroller T, Franco I, et al. Deep learning predicts lung cancer treatment response from serial medical imaging. Clin Cancer Res. (2019) 25:3266–75. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baldwin DR, Gustafson J, Pickup L, Arteta C, Novotny P, Declerck J, et al. External validation of a convolutional neural network artificial intelligence tool to predict malignancy in pulmonary nodules. Thorax. (2020) 75:306–12. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2019-214104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meier-Schroers M, Homsi R, Schild HH, Thomas D. Lung cancer screening with MRI: characterization of nodules with different non-enhanced MRI sequences. Acta Radiol. (2019) 60:168–76. 10.1177/0284185118778870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang S, Shi J, Ye Z, Dong D, Yu D, Zhou M, et al. Predicting EGFR mutation status in lung adenocarcinoma on computed tomography image using deep learning. Eur Respir J. (2019) 53:1800986. 10.1183/13993003.00986-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leleu O, Basille D, Auquier M, Clarot C, Hoguet E, Pétigny V, et al. Lung cancer screening by low-dose CT scan: baseline results of a french prospective study. Clin Lung Cancer. (2020) 21:145–52. 10.1016/j.cllc.2019.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trebeschi S, Drago SG, Birkbak NJ, Kurilova I, Cǎlin AM, Delli Pizzi A, et al. Predicting response to cancer immunotherapy using noninvasive radiomic biomarkers. Ann Oncol. (2019) 30:998–1004. 10.1093/annonc/mdz108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cong M, Yao H, Liu H, Huang L, Shi G. Development and evaluation of a venous computed tomography radiomics model to predict lymph node metastasis from non-small cell lung cancer. Medicine. (2020) 99:e20074. 10.1097/MD.0000000000020074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Botta F, Raimondi S, Rinaldi L, Bellerba F, Corso F, Bagnardi V, et al. Association of a CT-based clinical and radiomics score of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with lymph node status and overall survival. Cancers. (2020) 12:1432. 10.3390/cancers12061432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mu W, Tunali I, Gray JE, Qi J, Schabath MB, Gillies RJ. Radiomics of 18F-FDG PET/CT images predicts clinical benefit of advanced NSCLC patients to checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. (2020) 47:1168–82. 10.1007/s00259-019-04625-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khorrami M, Prasanna P, Gupta A, Patil P, Velu PD, Thawani R, et al. Changes in CT radiomic features associated with lymphocyte distribution predict overall survival and response to immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. (2020) 8:108–19. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-19-0476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirienko M, Sollini M, Corbetta M, Voulaz E, Gozzi N, Interlenghi M, et al. Radiomics and gene expression profile to characterise the disease and predict outcome in patients with lung cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. (2021) 48:3643–55. 10.1007/s00259-021-05371-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rossi G, Barabino E, Fedeli A, Ficarra G, Coco S, Russo A, et al. Radiomic detection of EGFR mutations in NSCLC. Cancer Res. (2021) 81:724–31. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-0999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yating C, Shu L, Xingyuan J, Fan W, Ye L. Combined model of radiomics features and clinical labels of peritumoral tissue to predict lymph node metastasis in T1 non-small cell lung cancer. Chin J Clin Med Imaging. (2021) 32:470–5. 10.12117/jccmi.2021.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chao W, Xia L, Di D, Liya Z, Zaiyi L, Changhong L, et al. Prediction of lymph node metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer based on radiomics. Chin J Autom. (2019) 45:1087–93. 10.16383/j.aas.c160794 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wen PY, Macdonald DR, Reardon DA, Cloughesy TF, Sorensen AG, Galanis E, et al. Updated response assessment criteria for high-grade gliomas: response assessment in neuro-oncology working group. J Clin Oncol. (2010) 28:1963–72. 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaunzwa TL, Christiani DC, Lanuti M, Shafer A, Aerts H. Using deep-learningradiomics to predict lung cancer histology. J Clin Oncol. (2018) 36:8545. 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.854533727623 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chalkidou A, O'Doherty MJ, Marsden PK. False discovery rates in PET and CT studies with texture features: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0124165. 10.1371/journal.pone.0124165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forghani R, Savadjiev P, Chatterjee A, Muthukrishnan N, Reinhold C, Forghani B. Radiomics and artificialintelligence for biomarker and prediction model development in oncology. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. (2019) 17:995–1008. 10.1016/j.csbj.2019.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zacharaki EI, Wang S, Chawla S, Soo Yoo D, Wolf R, Melhem ER, et al. Classification of brain tumor type andgrade using MRI texture and shape in a machine learning scheme. Magn Reson Med. (2009) 62:1609–18. 10.1002/mrm.22147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qian Z, Li Y, Wang Y, Li L, Li R, Wang K, et al. Differentiation of glioblastoma from solitarybrain metastases using radiomic machine-learning classifiers. Cancer Lett. (2019) 451:128–35. 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.02.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lambin P, Leijenaar RTH, Deist TM, Peerlings J, de Jong EEC, van Timmeren J, et al. Radiomics: the bridge betweenmedical imaging and personalized medicine. Nat Rev Clinicaloncol. (2017) 14:749. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cai H, Cui C, Tian H, Zhang M, Li L. A novel approach to segment and classify regional lymph nodes on computed tomography images. Comput Math Methods Med. (2012) 2012:1–9. 10.1155/2012/145926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perone CS, Cohen-Adad J. Promises and limitations of deep learning for medical image segmentation. J Med Artif Intel. (2019) 2:1. 10.21037/jmai.2019.01.01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim DW, Jang HY, Kim KW, Shin Y, Park SH. Design characteristics of studies reporting the performance of artificial intelligence algorithms for diagnostic analysis of medical images: results from recently published papers. Korean J Radiol. (2019) 20:405–10. 10.3348/kjr.2019.0025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steyerberg EW, Moons KG, van der Windt DA, Hayden JA, Perel P, et al. Prognosis Research Strategy (PROGRESS) 3: prognostic model research. PLoS Med. (2013) 10:e1001381. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu X, Faes L, Kale AU, Wagner SK, Fu DJ, Bruynseels A, et al. A comparison of deep learning performance against healthcare professionals in detecting diseases from medical imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Digital Health. (2019) 1:e271–97. 10.1016/S2589-7500(19)30123-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.