Abstract

The Escherichia coli BglF protein, an enzyme II of the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent carbohydrate phosphotransferase system, has several enzymatic activities. In the absence of β-glucosides, it phosphorylates BglG, a positive regulator of bgl operon transcription, thus inactivating BglG. In the presence of β-glucosides, it activates BglG by dephosphorylating it and, at the same time, transports β-glucosides into the cell and phosphorylates them. BglF is composed of two hydrophilic domains, IIAbgl and IIBbgl, and a membrane-bound domain, IICbgl, which are covalently linked in the order IIBCAbgl. Cys-24 in the IIBbgl domain is essential for all the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation activities of BglF. We have investigated the domain requirement of the different functions carried out by BglF. To this end, we cloned the individual BglF domains, as well as the domain pairs IIBCbgl and IICAbgl, and tested which domains and which combinations are required for the catalysis of the different functions, both in vitro and in vivo. We show here that the IIB and IIC domains, linked to each other (IIBCbgl), are required for the sugar-driven reactions, i.e., sugar phosphotransfer and BglG activation by dephosphorylation. In contrast, phosphorylated IIBbgl alone can catalyze BglG inactivation by phosphorylation. Thus, the sugar-induced and noninduced functions have different structural requirements. Our results suggest that catalysis of the sugar-induced functions depends on specific interactions between IIBbgl and IICbgl which occur upon the interaction of BglF with the sugar.

The Escherichia coli BglF protein (EIIbgl), an enzyme II (EII) of the phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP)-dependent carbohydrate phosphotransferase system (PTS), catalyzes concomitant transport and phosphorylation of β-glucosides (11). In addition, BglF regulates bgl operon expression by controlling the activity of the transcriptional regulator BglG. In the absence of β-glucosides, BglF phosphorylates BglG, thus inactivating it; in the presence of β-glucosides, BglF dephosphorylates BglG, which can then function as a transcriptional antiterminator and enable bgl operon expression (1, 2, 3, 24). Thus, BglF is the β-glucoside phosphotransferase, the BglG kinase, and the phosphorylated BglG (BglG-P) phosphatase. A dimeric form of BglF can catalyze all these activities (7).

Like other EIIs of the PTS, BglF is composed of three domains. IIAbgl possesses the first phosphorylation site, His-547 (site 1), which is phosphorylated by HPr; IIBbgl possesses the second phosphorylation site, Cys-24 (site 2), which accepts the phosphoryl group from IIAbgl and transfers it to β-glucosides; and IICbgl, the membrane-spanning domain, presumably forms the sugar translocation channel and at least part of the sugar-binding site (9, 25). The order of these domains in BglF is IIBCAbgl (reviewed in references 17 and 20). BglF uses site 2, Cys-24 on the IIBbgl domain, to phosphorylate the two substrates, β-glucosides and BglG (9), and to dephosphorylate BglG-P (10). A rearranged BglF protein which contains the three domains in the order IICBAbgl (scrambled-BglF) catalyzes BglG phosphorylation but fails to carry out the sugar-induced reactions, i.e., sugar phosphotransfer and BglG-P dephosphorylation (8). These findings suggest that the structural requirements for the sugar-induced functions differ from those for the noninduced function. The key to BglF stimulation, i.e., the sugar-induced change which switches it from a BglG kinase mode to a BglG-P phosphatase and sugar phosphotransferase mode, is not understood.

To define the domain(s) required for catalysis of the different functions of BglF, we subcloned and expressed the three individual domains, IIAbgl, IIBbgl, and IICbgl, as well as truncated BglF proteins which lack one domain (IIBCbgl and IICAbgl). We show that phosphorylated IIBbgl alone can phosphorylate BglG in vitro and negatively regulate its activity as a transcriptional antiterminator in vivo. In contrast, IIBCbgl is required for β-glucoside phosphorylation in vitro and for β-glucoside utilization in vivo. The same holds true for BglG-P activation by dephosphorylation. These results suggest that the immediate environment of the BglF active site changes upon sugar stimulation. This change induces specific interactions between the active site-containing domain, IIBbgl, and the membrane-bound domain, IICbgl.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

The following E. coli K-12 strains were used. K38 (HfrC trpR thi λ+) was obtained from C. Richardson. LM1 contains mutations in the nagE and crr genes, which code for EIInag and IIAglc, respectively (13). ZSC112ΔG contains a deletion of the ptsG gene, which codes for IICBglc (6). PPA501 contains a mutation in the bglF gene and carries a bgl′-lacZ fusion on its chromosome (9). SG13009 was obtained from Qiagen.

Plasmids.

The plasmids that encode the BglF derivatives used in this study are listed in Table 1. Plasmid pACYC184 was obtained from New England Biolabs. Plasmid pQE-30, which contains a translation start site followed by a sequence coding for six histidines and a multicloning site, and plasmid pREP4, which carries the lacI gene encoding the lac repressor, were obtained from Qiagen. Plasmid pT712, which contains the phage T7 late promoter, and plasmid pGP1-2, which carries the T7 RNA polymerase gene under the control of the λcI857 repressor, were obtained from Bethesda Research Laboratories. Plasmid pT7OAC-F carries the entire bglF gene cloned downstream of the T7 promoter in pT712 (1). Plasmid pT7CQ-F1, a derivative of pT7OAC-F, encodes BglF with His-547 mutated to Arg (H547R) (9). Plasmid pMN5 carries the entire bglF gene cloned in pBR322 (14). Plasmids pT7CQ-F3, pT7CQ-F4, pT7CQ-F5, pT7CQ-F6, and pT7CQ-F8 are derivatives of pT712 which code for IIBbgl, IICbgl, IIAbgl, IICAbgl, and IIBCbgl, respectively, from the T7 promoter (7). Additional plasmids were constructed as described below.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids encoding BglF derivatives

| Plasmid | Encoded BglF derivative | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| pT7OAC-F | Wild-type BglF (IIBCAbgl) | 1 |

| pT7CQ-F1 | H547R | 9 |

| pT7CQ-F3 | IIBbgl | 7 |

| pT7CQ-F4 | IICbgl | 7 |

| pT7CQ-F5 | IIAbgl | 7 |

| pT7CQ-F6 | IICAbgl | 7 |

| pT7CQ-F8 | IIBCbgl | 7 |

| pMN5 | Wild-type BglF (IIBCAbgl) | 14 |

| pACQ-F3 | IIBbgl | This work |

| pACQ-F6 | IICAbgl | This work |

| pACQ-F8 | IIBCbgl | This work |

| pQE-F5 | IIAbgl tagged with six histidine | This work |

pACQ-F3, which encodes IIBbgl, was constructed by ligating a 593-bp EcoRI-PvuII fragment from pT7CQ-F3 to a 3,838-bp EcoRI-ScaI fragment from pACYC184.

pACQ-F6, which encodes IICAbgl, was constructed by ligating a 2,065-bp EcoRI-PvuII fragment from pT7CQ-F6 to a 3,838-bp EcoRI-ScaI fragment from pACYC184.

pACQ-F8, which encodes IIBCbgl, was constructed by ligating a 1,730-bp EcoRI-PvuII fragment from pT7CQ-F8 to a 3,838-bp EcoRI-ScaI fragment from pACYC184.

pQE-F5, which encodes IIAbgl tagged with six histidines, was constructed by ligating a 908-bp PstI-PvuII fragment from pT7CQ-F5 to a 3,091-bp PstI-PvuII fragment from pQE-30.

Chemicals.

[γ-32P]ATP (7,000 Ci/mmol) was obtained from ICN. [35S]methionine (1,200 Ci/mmol) was obtained from Du Pont. PEP, pyruvic acid, and pyruvate kinase were obtained from Sigma. [32P]PEP was prepared and separated from [32P]ATP as described before (1). Purified enzyme I (EI) and HPr were obtained from J. Reizer. Maltose binding protein (MBP)-BglG was purified as described previously (9). Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) resin was obtained from Qiagen.

Molecular cloning and β-galactosidase assay.

All manipulations with recombinant DNA were carried out by standard procedures (21). Assays for β-galactosidase activity were carried out as described by Miller (16). Cells were grown in minimal medium supplied with 0.4% succinate as a carbon source.

[35S]methionine labeling of BglF and its derivatives.

Cells of strain K38, containing plasmid pGP1-2 and one of the plasmids carrying the bglF gene or its derivatives under the control of the phage T7 promoter (pT7OAC-F, pT7CQ-F3, pT7CQ-F4, pT7CQ-F6, or pT7CQ-F8), were induced and labeled with [35S]methionine in the presence of rifampin (Sigma) as described previously (26). To study the stability of plasmid-encoded BglF derivatives, unlabeled methionine was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml to the growth medium (chase) following 2 min of pulse-labeling with [35S]methionine, and aliquots were removed at various times for autoradiographic analysis.

Preparation of membrane fractions and cell extracts.

Membrane fractions enriched for wild-type BglF or one of its derivatives containing the membrane-bound IIC domain (H547R, IICAbgl, IIBCbgl, or IICbgl) were prepared as described previously (1). Cell extract enriched for the soluble IIBbgl polypeptide was prepared as described previously for BglG-enriched extract (1). The proteins were expressed from their respective genes cloned under T7 promoter control in plasmids pT7OAC-F, pT7CQ-F1, pT7CQ-F6, pT7CQ-F8, pT7CQ-F4, and pT7CQ-F3, respectively. Expression of T7 RNA polymerase from compatible pGP1-2 was induced thermally. Strain LM1 was used as a host in most cases. When needed, strain ZSC112ΔG (with a deletion of the ptsG gene) was used as a host for IIBCbgl overproduction from pT7CQ-F8. Membrane fractions lacking BglF were prepared from LM1/pGP1-2/pT712 and ZSC112ΔG/pGP1-2/pT712 and were used in control experiments.

Purification of IIAbgl.

Expression and purification of IIAbgl were carried out essentially as recommended by Qiagen with some modifications. One liter of SG13009/pREP4/pQE-F5 culture was grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 in Luria broth containing 200 μg of ampicillin and 30 μg of kanamycin per ml at 30°C. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 0.1 mM, and growth was continued for 5 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 20 min in the cold. The pelleted cells were resuspended in buffer S (50 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.8], 300 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) supplemented with 5 μg of DNase and 20 μg of RNase per ml and were broken by passing the suspension twice through a French pressure cell at 12,000 lb/in2. Unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 20 min in the cold. The supernatant was mixed gently at 4°C for 16 h with 2 ml of a 50% slurry of Ni-NTA resin preequilibrated in buffer S. The resin was then packed in a column. The column was washed once with buffer S, once with buffer S containing 40 mM imidazole and 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, and once with buffer S containing 250 mM imidazole. Fractions collected during the last wash were analyzed on tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels, and those containing histidine-tagged IIAbgl were dialyzed against buffer S to remove the imidazole. The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay with a kit purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories.

In vitro phosphorylation.

In vitro phosphorylation experiments were carried out essentially as described by Chen et al. (9). Briefly, membranes with a final protein concentration of 0.9 mg/ml were labeled by incubation at 30°C in a mixture containing 10 μg of EI per ml, 40 μg of HPr per ml, 10 μM [32P]PEP, and PLB buffer (50 mM Na2HPO4 [pH 7.4], 0.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM NaF, 2 mM dithiothreitol). When indicated, cell extracts enriched for IIBbgl and/or purified histidine-tagged IIAbgl were added at final protein concentrations of 0.8 mg/ml and 72 μg/ml, respectively. After incubation for 10 min, reactions were either terminated by the addition of electrophoresis sample buffer or further incubated as described below. To study dephosphorylation by β-glucosides, salicin was added to a final concentration of 0.2%, and incubation was continued at 30°C for 5 min. To study BglG phosphorylation, purified MBP-BglG in PLB buffer was added to a final concentration of 10 μM, and incubation was continued at 30°C for 15 min.

Electrophoresis and autoradiography.

Electrophoresis of proteins was carried out on SDS-polyacrylamide gels (12) or on tricine-SDS-polyacrylamide gels (23). Samples were fractionated next to prestained low- or mid-range-molecular-weight markers (Amersham). After electrophoresis, gels were stained with Coomassie blue or directly dried and exposed to Kodak XAR-5 X-ray film at −70°C.

RESULTS

To define the domains required for the different functions of BglF, we subcloned the individual domains, IIAbgl, IIBbgl, and IICbgl, as well as the domain pairs, IICAbgl and IIBCbgl. We then examined the ability of the different polypeptides (i) to be phosphorylated in vitro in the presence of PEP and the general PTS proteins enzyme I (EI) and HPr; (ii) once phosphorylated, to transfer the phosphoryl group to β-glucosides and to BglG in vitro; and (iii) to mediate β-glucoside utilization and modulate BglG activity in vivo.

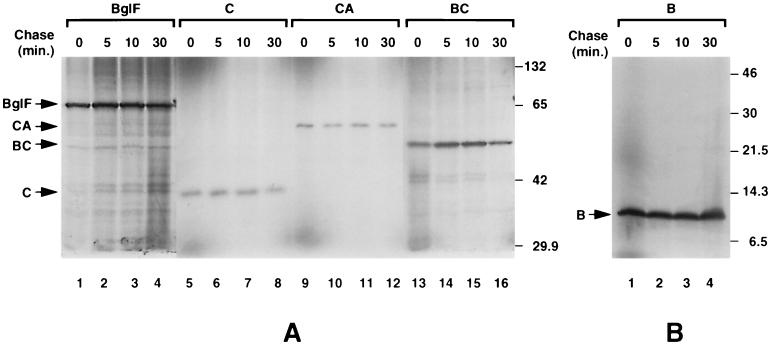

The stability of the different plasmid-encoded polypeptides was assayed with pulse-chase experiments. The proteins were labeled with [35S]methionine and chased with unlabeled methionine. Samples removed at different times were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The results (Fig. 1) demonstrate that IIBbgl, IICbgl, IICAbgl, and IIBCbgl expressed from the heat-inducible T7 promoter are very stable, like wild-type BglF, although they are produced at variable levels.

FIG. 1.

Individual BglF domains and domain pairs are stable. Expression of wild-type BglF, IIBbgl (B), IICbgl (C), IICAbgl (CA), and IIBCbgl (BC), was induced from pT7OAC-F, pT7CQ-F3, pT7CQ-F4, pT7CQ-F6, and pT7CQ-F8, respectively, in E. coli K38 cells harboring pGP1-2. The plasmid-encoded proteins were pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine for 2 min and chased by the addition of unlabeled methionine to the growth medium. Aliquots, removed at the times indicated, were analyzed on SDS–10% polyacrylamide gels (A) or on tricine–SDS–16.5% polyacrylamide gels (B). Autoradiograms of the gels are shown. An unstable protein (a truncated BglG protein) was used as a control for chase success (data not shown). Molecular masses of protein standards are given in kilodaltons.

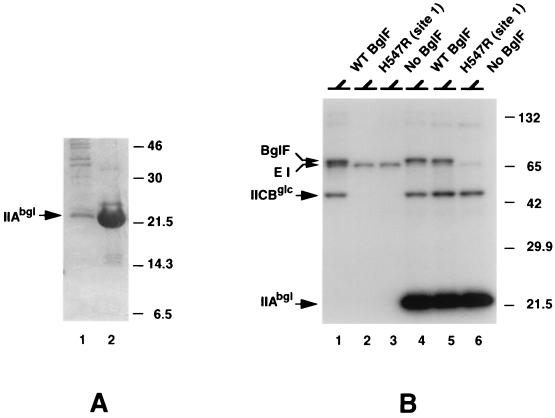

Due to the low level of IIAbgl produced under the control of the T7 promoter, we engineered histidine-tagged IIAbgl expressed from an IPTG-inducible promoter (see Materials and Methods). The His-tagged IIAbgl polypeptide was purified almost to homogeneity by affinity chromatography (Fig. 2A). The ability of His-tagged IIAbgl to accept a phosphoryl group from HPr and to deliver it to site 2 of BglF was tested in vitro as follows. Purified His-tagged IIAbgl was incubated with [32P]PEP, purified EI and HPr, and membranes of strain LM1 (with deletions of the crr and nagE genes) enriched for a BglF mutant protein which lacks phosphorylation site 1 (H547R). The results presented in Fig. 2B demonstrated that His-tagged IIAbgl enabled efficient phosphorylation of H547R (lane 5). H547R was not phosphorylated in this in vitro phosphorylation system when His-tagged IIAbgl was omitted (Fig. 2B, lane 2). His-tagged IIBbgl was engineered and purified in a similar manner.

FIG. 2.

Histidine-tagged IIAbgl is functional. (A) Expression of His-tagged IIAbgl was induced by IPTG from plasmid pQE-F5 in strain SG13009 harboring plasmid pREP4 (lane 1). His-tagged IIAbgl was purified on an Ni-NTA column (lane 2) (see Materials and Methods). Samples were analyzed on tricine–SDS–16.5% polyacrylamide gels, followed by Coomassie blue staining. (B). Membranes of LM1 cells that overproduced wild-type (WT) BglF or H547R proteins were incubated with [32P]PEP and purified EI and HPr for 10 min without (lanes 1 and 2) or with (lanes 4 and 5) His-tagged IIAbgl. No BglF, membranes from cells which did not overproduce BglF but which were otherwise identical to the other membrane preparations used in this experiment. Samples were analyzed on SDS–10% polyacrylamide gels, followed by autoradiography. Molecular masses of protein standards are given in kilodaltons.

IIBbgl is sufficient for BglG phosphorylation, whereas IIBCbgl is required for β-glucoside phosphorylation in vitro.

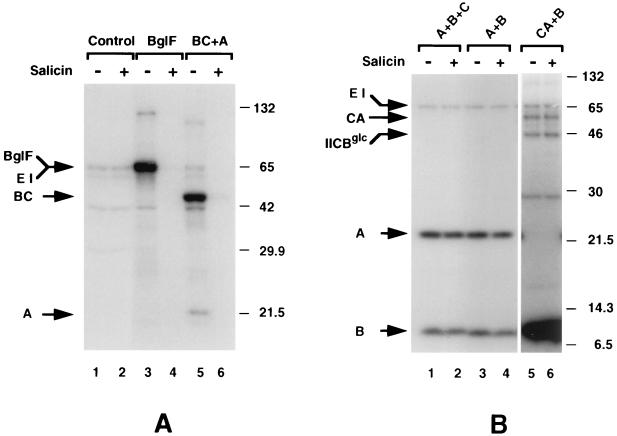

It was previously shown that His-547 in IIAbgl accepts the phosphoryl group from HPr and transfers it to Cys-24 in IIBbgl, which can then deliver it to β-glucosides or to BglG (9). It has also been demonstrated that the dephosphorylation of BglF in the presence of β-glucosides in vitro is a good indication of the ability of BglF to transfer the phosphoryl group to the sugar (1). We therefore tested the ability of different combinations of BglF domains to be phosphorylated in vitro and then to be dephosphorylated by the β-glucoside salicin.

To test IIBCbgl phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, we produced the protein in strain ZSC112ΔG, which has a deletion of the ptsG gene. This strain does not contain IICBglc, which is present in membrane preparations of E. coli strains, such as LM1, in significant amounts (9) and which migrates very close to IIBCbgl on SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Membranes of ZSC112ΔG enriched for IIBCbgl were incubated with [32P]PEP and purified EI, HPr, and His-tagged IIAbgl. As shown in Fig. 3A, IIBCbgl was efficiently phosphorylated by His-tagged IIAbgl (lane 5) and, like wild-type BglF (lanes 3 and 4), was efficiently dephosphorylated by the addition of salicin (lane 6).

FIG. 3.

Phosphorylated IIBCbgl is required for the phosphorylation of β-glucosides. Wild-type BglF and IIBCbgl (BC) were overproduced in ZSC112ΔG, a ptsG strain. IIBbgl (B), IICbgl (C), and IICAbgl (CA) were overproduced in LM1, a crr and nagE strain. His-tagged IIAbgl (A) was purified on an Ni-NTA column. Mixtures of the indicated proteins were incubated with [32P]PEP and purified EI and HPr for 10 min. Incubation was continued with (+) or without (−) 0.2% salicin for 5 min. Samples were analyzed on SDS–10% polyacrylamide gels (A) or on tricine–SDS–8 to 20% gradient polyacrylamide gels (B). Autoradiograms are presented. Molecular masses of protein standards are given in kilodaltons. Control, membranes from cells which did not overproduce BglF or any of its domains but which were otherwise identical to the other membrane preparations used in this experiment. EI and BglF comigrated in the gel system used in panel A.

To check whether IIBbgl not linked to IICbgl can be dephosphorylated by salicin, an LM1 cell extract enriched for IIBbgl was incubated with [32P]PEP, EI, HPr, and (i) His-tagged IIAbgl, (ii) His-tagged IIAbgl and membranes of LM1 enriched for IICbgl, or (iii) membranes of LM1 enriched for IICAbgl. The results are shown in Fig. 3B. IIBbgl was phosphorylated in all cases (Fig. 3B, lanes 1, 3, and 5); i.e., it could accept the phosphoryl group from His-tagged IIAbgl or from IICAbgl. However, phosphorylated IIBbgl was not dephosphorylated by salicin in any of these cases (Fig. 3A, lanes 2, 4, and 6). Therefore, IIBbgl separated from IICbgl cannot phosphorylate β-glucosides. The same results were obtained when His-tagged IIBbgl was used instead of a cell extract enriched for IIBbgl (data not shown).

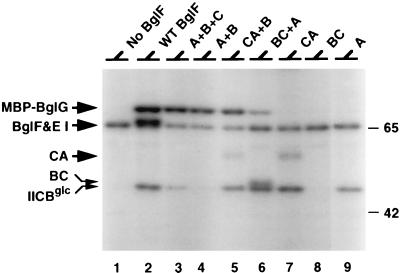

We next tested the ability of different combinations of BglF domains to phosphorylate BglG in vitro. Purified MBP-BglG (BglG fused to maltose-binding protein), which was previously shown to be phosphorylated by BglF on its BglG moiety in vitro (9), was added to mixtures of BglF domains which were prelabeled with [32P]PEP, EI, and HPr. The results (Fig. 4, lanes 3 to 5) showed that IIBbgl phosphorylated by IICAbgl or by His-tagged IIAbgl could phosphorylate MBP-BglG. The same held true for IIBCbgl phosphorylated by His-tagged IIAbgl (Fig. 4, lane 6). IICbgl was dispensable for phosphoryl transfer from phosphorylated IIAbgl to IIBbgl and from phosphorylated IIBbgl to MBP-BglG (Fig. 4, lane 4). IIAbgl was required for these phosphorylation reactions (Fig. 4, lane 8) but could not phosphorylate MBP-BglG in the absence of IIBbgl (Fig. 4, lanes 7 and 9). The same results were obtained when His-tagged IIBbgl was used instead of a cell extract enriched for IIBbgl (data not shown). No phosphorylation of MBP-BglG could be detected when MBP-BglG was added to membranes that lacked BglF and that were prelabeled in the in vitro phosphorylation reaction (Fig. 4, lane 1). This result is in agreement with our previous observation that phosphorylated EI and HPr cannot phosphorylate BglG (9).

FIG. 4.

Phosphorylated IIBbgl is sufficient for the phosphorylation of BglG. Wild-type (WT) BglF, IIBbgl (B), IICbgl (C), IIBCbgl (BC), and IICAbgl (CA) were overproduced in strain LM1. His-tagged IIAbgl was purified on an Ni-NTA column. Mixtures of the indicated proteins were labeled as described in the legend to Fig. 3 and further incubated with MBP-BglG for 15 min. Proteins were fractionated on SDS–5 to 12% gradient polyacrylamide gels, followed by autoradiography. Molecular masses of protein standards are given in kilodaltons. No BglF, see the legend to Fig. 2. EI and BglF comigrated in this gel system.

Based on the results presented here, it can be concluded that IIBbgl alone can accept the phosphoryl group from phosphorylated IIAbgl and transfer it to BglG. IICbgl is not involved in these phosphotransfer reactions. However, phosphorylated IIBbgl separated from IICbgl is incapable of delivering its phosphoryl group to β-glucosides. In contrast, phosphorylated IIBCbgl can catalyze β-glucoside phosphorylation.

IIBbgl can negatively regulate BglG antitermination activity, whereas IIBCbgl is required for β-glucoside utilization and for the relief of BglG inhibition in vivo.

To substantiate our in vitro results by in vivo studies, we analyzed the ability of different combinations of BglF domains to transfer β-glucosides into the cell while phosphorylating them and to negatively regulate BglG activity as a transcriptional antiterminator.

We first tested whether plasmids which encode the individual BglF domains or domain pairs can complement a bglF mutant strain. To this end, the different truncated BglF proteins or certain combinations encoded by compatible plasmids were produced in the bglF strain PPA501. This strain produces IIAglc and EIInag, which can substitute for IIAbgl (9, 25). Complementation is indicated by growth on minimal arbutin plates and by the formation of red colonies on MacConkey arbutin plates. Utilization of the β-glucoside arbutin depends on the ability of the plasmid-encoded BglF derivatives to phosphorylate and transport this sugar, which is then cleaved by the product of the unlinked locus bglA. Utilization of the β-glucoside salicin is prohibited in this strain due to the polarity of the mutation in bglF on the cotranscribed bglB gene, whose product preferentially cleaves phosphosalicin (14). The results are presented in Table 2. Only IIBCbgl behaved like wild-type BglF and complemented the bglF mutant strain. These in vivo observations demonstrated that separated IIBbgl and IICbgl cannot complement each other to enable β-glucoside transport and phosphorylation. IIBCbgl is required for β-glucoside utilization in vivo, as predicted from in vitro data. The failure of the unjoined domains to complement the bglF mutant strain cannot be explained by insufficient levels of the separated domains. Although the effective relative concentrations of the IIB and IIC domains are higher in the linked polypeptide than when they are not covalently joined, the individual domains in this experiment were expressed from multicopy plasmids. In addition, soluble IIBbgl is expressed much more efficiently than IIBCbgl and BglF (Fig. 1; note that IIB contains only three methionines).

TABLE 2.

Biological functions of BglF individual domains or combinations of domains in vivo

| Plasmid(s) | Plasmid-encoded BglF derivative | Complementationa of bglF mutant strain PPA501 (expressing IIAglc and EIInag) | β-Galactosidase activity (U)b

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without salicin | With salicin | |||

| pMN5 | Wild-type BglF | + | 5 | 153 |

| pACQ-F3 | IIBbgl | − | 3 | 5 |

| pT7CQ-F4 | IICbgl | − | 175 | 178 |

| pT7CQ-F5 | IIAbgl | − | 225 | 255 |

| pACQ-F6 | IICAbgl | − | 724 | 637 |

| pACQ-F8 | IIBCbgl | + | 10 | 415 |

| pACQ-F6/ pT7CQ-F3 | IICAbgl + IIBbgl | − | 5 | 5 |

| pT7CQ-F4/ pACQ-F3 | IICbgl + IIBbgl | − | 4 | 4 |

| pBR322 | − | 447 | 456 | |

Complementation was indicated by two alternative methods: +, growth on minimal arbutin plates and red colonies on MacConkey arbutin plates; −, no growth on minimal arbutin plates and white colonies on MacConkey arbutin plates.

Determined with strain PPA501, which carries a bgl-lacZ transcriptional fusion and a defective bglF gene and which constitutively expresses IIAglc and EIInag, encoded by genes crr and nagE, respectively. The values represent the averages of four independent measurements. Salicin at 7 mM was added to the growth medium when indicated.

The ability of BglF to inactivate the transcriptional antiterminator BglG in the absence of β-glucosides stems from its ability to phosphorylate BglG. The relief of BglG inhibition upon β-glucoside addition is due to the dephosphorylation of BglG by sugar-stimulated BglF (1). Therefore, to examine the ability of individual BglF domains, domain pairs, and combinations of domains to phosphorylate and dephosphorylate BglG in vivo, we tested their ability to regulate the activity of BglG as a transcriptional antiterminator. To this end, we made use of strain PPA501, which carries a chromosomal fusion of the bgl promoter and transcriptional terminator to lacZ and which lacks a functional bglF gene. BglG is not negatively regulated by phosphorylation in this strain, and high β-galactosidase activity is measured whether or not β-glucosides are added to the growth medium (Table 2, line 9). The expression of plasmid-encoded wild-type BglF in strain MA200-1 renders lacZ expression inducible; in the absence of β-glucosides, the lacZ gene is not transcribed because BglG is inactivated by phosphorylation; upon the addition of β-glucosides, BglF dephosphorylates BglG, allowing it to block transcription termination, and the lacZ gene is expressed (Table 2, line 1).

IIBCbgl (which could be phosphorylated by IIAglc and EIInag in PPA501) behaved like wild-type BglF, allowing lacZ expression only upon the addition of β-glucosides (Table 2, line 6). Thus, as expected from the in vitro results, IIBCbgl could inhibit BglG activity by phosphorylation and could relieve the inhibition by dephosphorylation in vivo. IIBbgl (which could also be phosphorylated by IIAglc and EIInag in PPA501) inhibited BglG activity by phosphorylation, as indicated by the low β-galactosidase levels obtained in the absence of β-glucosides. However, low β-galactosidase levels were also recorded in the presence of β-glucosides, indicating that IIBbgl could not relieve the inhibition of BglG by dephosphorylating it (Table 2, lines 2, 7, and 8). IICbgl was not required to enable IIBbgl to act as a BglG negative regulator in vivo (Table 2, compare line 2 with lines 7 and 8), nor could it act in trans with IIBbgl to implement BglG dephosphorylation (Table 2, lines 7 and 8). As expected, the production of IICbgl, IIAbgl, or IICAbgl in PPA501 did not affect the constitutive nature of lacZ expression (Table 2, lines 3 to 5); i.e., these polypeptides cannot regulate BglG activity by phosphorylation.

DISCUSSION

The ability of the same active site on BglF to phosphorylate β-glucosides and to reversibly phosphorylate BglG prompted us to investigate the structural basis for sugar-controlled differential phosphorylation. Dimerization of BglF could not explain the β-glucoside-induced switch in BglF activity, since β-glucoside does not affect the BglF dimeric state (7). In addition, both the sugar-induced and noninduced functions could be catalyzed by BglF dimers, which seem to form spontaneously (7).

The requirements for β-glucoside phosphorylation and for BglG dephosphorylation, both stimulated by the sugar, are expected to be similar and to differ from the requirements for BglG phosphorylation, which occurs in the absence of the sugar. In light of our finding that only the sugar-stimulated activities are sensitive to changing the domain order within BglF (8), we speculated that the domains required for the sugar-stimulated functions might differ from those required for the nonstimulated functions. Of course, the IIB domain, which contains the active site, is expected to be required for all functions. We therefore attempted to define the domains which are required for the different functions by assaying the catalytic activities of individual domains or combination of domains, either covalently linked or produced in trans. Our results (summarized in Table 3) showed that intact IIBCbgl is critical for the ability to implement β-glucoside phosphorylation and BglG dephosphorylation, whereas BglG phosphorylation can be catalyzed by IIBbgl alone. IICbgl could not rescue IIBbgl and enable it to catalyze the sugar-stimulated functions, unless it was linked to it, i.e., IIBCbgl. Nonetheless, the domain requirements for the nonstimulated function are quite loose; i.e., the domain which contains the active site, IIBbgl, is sufficient. Phosphotransfer from IIAbgl to IIBbgl is the same in the presence and absence of IICbgl, suggesting that the activity of IIBbgl as a phosphoryl acceptor is not affected by IICbgl.

TABLE 3.

Summary of the demonstrated activities of BglF domain polypeptides

| BglF domain(s) | β-Glucoside phosphory-lationa | BglG phosphory-lationb | BglG dephosphory-lationc |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCA (wild-type BglF) | + | + | + |

| A | − | − | − |

| B | − | + | − |

| C | − | − | − |

| CA | − | − | − |

| BC | + | + | + |

| C + B | − | + | − |

Ability to phosphorylate β-glucosides in vitro (Fig. 3) and/or to complement bglF mutant strains (Table 2).

Ability to phosphorylate BglG in vitro (Fig. 4) and/or to negatively regulate BglG activity in vivo (Table 2, β-galactosidase activity without salicin).

Ability to restore BglG activity in vivo in the presence of β-glucosides (Table 2, β-galactosidase activity with salicin).

These results agree with our previous observation that the order of the domains in BglF (BCA) is critical for β-glucoside phosphorylation and BglG dephosphorylation, whereas BglG phosphorylation can be catalyzed by a scrambled-BglF derivative with the domain order CBA (8). One possible explanation for our previously and currently reported results is that β-glucosides induce an interaction between the IIBbgl and IICbgl domains. Such an interaction could induce a conformational change in BglF and might be the key to the sugar-induced signal transduction pathway that leads to the expression of the bgl operon. In fact, the catalysis of alternative functions due to different interactions between protein domains might be a general theme in the stimulation and/or regulation of diverse functions which are dictated by environmental or cellular conditions. Another possible explanation for our results is suggested by the reversible nature of the BglG phosphorylation reaction (10). The sugar substrate, by dephosphorylating BglF-P, shifts the equilibrium and leads to dephosphorylation of BglG-P. The role of the IIC domain in this process might be to present the sugar substrate to the phosphorylated IIB domain. The apparent requirement for a covalent connection between the two domains might reflect a requirement that they be in proximity and properly oriented for sugar phosphorylation to occur efficiently. The two explanations are not mutually exclusive. It is possible that a sugar-induced conformation of BglF orients IIC and IIB properly for sugar phosphorylation and BglG dephosphorylation.

A number of successful gene dissection and complementation experiments have been reported for other PTS sugar permeases. For example, IIAmtl could restore the activity of a IICBAmtl protein which lacks the first phosphorylation site (27), IIAglc from Bacillus subtilis complemented E. coli IICBglc (18), and IIAglc complemented a BglF mutant lacking phosphorylation site 1 (9, 25). Separation of the B domain of the mannitol permease or of the glucose permease from the respective C domain had a more drastic effect, yet catalytic activity was retained to some extent upon their coexpression (6, 19, 27). Moreover, a circularly permuted derivative of the E. coli glucose permease in which the order of the domains is BC rather than CB, as in the wild-type protein, has activity comparable to that of the wild-type protein (15). Nevertheless, a mixture of IIAmtl, IIBmtl, and IICmtl showed 4% the activity of the mannitol permease, which contains all three domains (19). Similarly, a mixture of IIAglc, IIBglc, and IICglc showed 2% sugar phosphorylation activity (6). A fusion protein which incorporates all proteins and protein domains of the glucose-specific PTS into a single polypeptide chain with the domain order IICglc-IIBglc-IIAglc-HPr-EI increased phosphotransfer activity over that of an equimolar mixture of the isolated subunits. Therefore, the linking of functional domains confers certain advantages to a specific PTS permease by rendering it more efficient (15). We do not have enough evidence yet to decide whether sensitivity to domain splitting and splicing is a characteristic of permeases which recognize similar sugars, of permeases which have more than one function, or of permeases which are related, due to a different, yet unknown, reason.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Reizer for the gift of purified enzyme I and HPr proteins.

This research was supported by a grant from the German-Israeli Foundation for Scientific Research and Development.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amster-Choder O, Houman F, Wright A. Protein phosphorylation regulates transcription of the β-glucoside utilization operon in E. coli. Cell. 1989;58:847–855. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90937-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amster-Choder O, Wright A. Regulation of activity of a transcriptional antiterminator in Escherichia coli by phosphorylation in vivo. Science. 1990;249:540–542. doi: 10.1126/science.2200123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amster-Choder O, Wright A. Modulation of dimerization of a transcriptional antiterminator protein by phosphorylation. Science. 1992;257:1395–1398. doi: 10.1126/science.1382312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amster-Choder O, Wright A. Transcriptional regulation of the bgl operon of E. coli involves phosphotransferase system-mediated phosphorylation of a transcriptional antiterminator. J Cell Biochem. 1993;51:83–90. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240510115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amster-Choder O, Wright A. BglG, the response regulator of the Escherichia coli bgl operon, is phosphorylated on a histidine residue. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5621–5624. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5621-5624.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buhr A, Flükiger K, Erni B. The glucose transporter of Escherichia coli: overexpression, purification and characterization of functional domains. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:23437–23443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Q, Amster-Choder O. BglF, the sensor of the bgl system and the β-glucoside permease of E. coli: evidence for dimerization and intersubunit phosphotransfer. Biochemistry. 1998;37:8714–8723. doi: 10.1021/bi9731652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, Q., and O. Amster-Choder. The different functions of BglF, the E. coli β-glucoside permease and the sensor of the bgl system, have different structural requirements. Biochemistry, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Chen Q, Arents J C, Bader R, Postma P W, Amster-Choder O. BglF, the sensor of the E. coli bgl system, uses the same site to phosphorylate both a sugar and a regulatory protein. EMBO J. 1997;16:4617–4627. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, Q., P. W. Postma, and O. Amster-Choder. Dephosphorylation of the E. coli transcriptional antiterminator BglG by the sugar-sensor BglF is the reversal of its phosphorylation. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Fox C F, Wilson G. The role of a phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent kinase system in β-glucoside catabolism in E. coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968;59:988–995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.59.3.988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lengeler J, Auburger A-M, Mayer R, Pecher A. The phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent carbohydrate: phosphotransferase system enzymes II as chemoreceptors in chemotaxis of Escherichia coli K12. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;183:163–170. doi: 10.1007/BF00270156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahadevan S, Reynolds A E, Wright A. Positive and negative regulation of the bgl operon in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2570–2578. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2570-2578.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mao Q, Schunk T, Gerber B, Erni B. A string of enzymes: purification and characterization of a fusion protein comprising the four subunits of the glucose phosphotransferase system of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18295–18300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller J. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Postma P W, Lengeler J W, Jacobson G R. Phosphoenolpyruvate: carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems of bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:543–594. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.543-594.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reizer J, Sutrina S L, Wu L-F, Deutscher J, Reddy P, Saier M H., Jr Functional interactions between proteins of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase systems of Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:9158–9169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robillard G T, Boer H, van Weeghel R P, Wolters G, Dijkstra A. Expression and characterization of a structural and functional domain of the mannitol-specific transport protein involved in the coupling of mannitol transport and phosphorylation in the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1993;32:9553–9562. doi: 10.1021/bi00088a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saier M H, Jr, Reizer J. Proposed uniform nomenclature for the proteins and protein domains of the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1433–1438. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.5.1433-1438.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaefler S. Inducible system for the utilization of β-glucosides in Escherichia coli. Active transport and utilization of β-glucosides. J Bacteriol. 1967;93:254–263. doi: 10.1128/jb.93.1.254-263.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schagger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schnetz K, Rak B. β-Glucoside permease represses the bgl operon of E. coli by phosphorylation of the antiterminator protein and also interacts with glucose-specific enzyme II, the key element in catabolic control. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5074–5078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.5074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schnetz K, Sutrina S L, Saier M H, Jr, Rak B. Identification of catalytic residues in the β-glucoside permease of Escherichia coli by site-directed mutagenesis and demonstration of interdomain cross-reactivity between the β-glucoside and glucose systems. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:13464–13471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tabor S, Richardson C C. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1074–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Weeghel R P, van der Hoek Y Y, Pas P P, Elferink M, Keck W, Robillard G T. Details of mannitol transport in Escherichia coli elucidated by site-specific mutagenesis and complementation of phosphorylation site mutants of the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent mannitol-specific phosphotransferase system. Biochemistry. 1991;30:1768–1773. doi: 10.1021/bi00221a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]