Editor—There have now been two major pandemic response phases in the UK and Ireland: one in the spring of 2020 and one in the winter of 2020/21. This has placed an unprecedented strain on frontline healthcare workers.1 , 2 Earlier research during the first pandemic response identified high rates of psychological distress and trauma in doctors2, 3, 4, 5 and trainees.6 , 7 The impact of further pandemic phases on mental health, workforce attrition, and clinical care is yet to be established. As the pandemic continues it is vital to track the psychological impact on acute care workers in order to inform policy and service provision. Here we report the rate of psychological distress and trauma of frontline doctors working in anaesthetics, intensive care medicine (ICM), and emergency medicine (EM) during January 2021. We compared these with previous findings to quantify progressive psychological impact.

The COVID-19 Emergency Response Assessment (CERA) study is an ongoing prospective longitudinal survey study evaluating the psychological health of frontline doctors across the UK and Ireland throughout the pandemic. All respondents of the original survey, delivered during the acceleration phase of the first response, were invited to participate in the most recent iteration.2 , 8 Participants repeated the original validated measures, the General Health Questionnaire-12 (GHQ-12) for psychological distress and the Impact of Events Scale—Revised (IES-R) for trauma response.9 , 10 Responses were collected from January 28, 2021 to February 11, 2021 (UK) and February 1, 2021 to February 15, 2021 (Ireland), contemporaneous with peak hospital COVID-19 deaths in this pandemic phase. Data were collected using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) hosted at University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust.11 , 12 Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Bath (UK) (ref: 20–218) and the Children's Health Ethics Committee (Ireland) (ref: GEN/806/20). Regulatory approval was obtained from the Health Regulation Authority (UK). All analyses and statistical outputs were produced using the statistical programming language R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).13

In total, 1719 participants responded to all CERA surveys, with response rates outlined in Supplementary 1. This latest cohort comprised 701 (40.8%) participants from anaesthesia, 778 (45.3%) from EM, and 164 (9.5%) from ICM; some worked across two specialties. Participant details and professional characteristics are summarised in Supplementary 2. The cohort was 51.0% female, had a median age of 36–40 yr, and was representative of all professional grades. Respondents were 66.2% ‘White British’, 7.1% ‘Irish’, and 26.1% ‘Ethnic Minority’.

The prevalence of psychological distress, as defined by a score >3 on the GHQ-12 0-0-1-1 scoring method, was 53.2% (n=801), an increase from 44.7% (n=1334) during the first pandemic response.2 The median GHQ-12 score was 15.0 (Q1–Q3 11.0–20.0), higher than all previous surveys.3 The average distress score was highest in the ICM cohort (Supplementary 3).

The prevalence of psychological trauma (IES-R >24) was higher during January 2021 compared with the peak of the first response, at 28.4% and 23.7%, respectively (Supplementary 3).3 The prevalence of ‘probable post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)’ (IES-R >33) also increased to 17.2% (n=225) from 12.6% (n=343).3 Prevalence of trauma (>24) increased in all speciality groups. This was highest in ICM at 31.1% (n=44) followed by EM (28.9%, n=176), and anaesthetics (27.7%, n=142). Across all surveys the median IES-R was 15 (Q1–Q3, 6–27), highest in the ICM cohort at 18 (Q1–Q3, 9–29) (Supplementary 3).

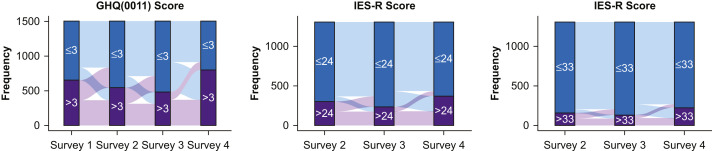

Rates of distress and trauma during January 2021 are the highest they have been during this pandemic. Figure 1 demonstrates the inter-survey change in GHQ-12 and IES-R for those who completed all surveys. This highlights a cohort of individuals who have consistently scored high distress and trauma scores across all time points, demonstrated as orange in Figure 1.

Fig 1.

Flow of outcome scores across all surveys.

Whilst there was a degree of recovery through the acceleration, peak, and deceleration phases of the first pandemic response, this was reversed during the January 2021 peak. Almost 50% of those scoring below the GHQ-12 distress threshold in the deceleration phase of the first response reported scores above this threshold in the current survey. This resulted in the majority of all respondents exceeding the distress threshold during January 2021 for the first time (Fig. 1).

Compared with previous surveys, there was an increase in the number of participants who reported psychological trauma (>24) and probable PTSD (>33) in the IES-R. Proportionally fewer respondents demonstrated recovery compared with the number of participants with worsening trauma symptoms between surveys 3 and 4 (Fig. 1). Further, 135/943 respondents who had never previously scored above 24 now reported a score above 24, and 60 (44.4%) of these were >33.

These results may be subject to bias; only 31.6% of participants responded to all surveys. The GHQ-12 and IES-R were designed as screening rather than diagnostic tools; therefore, findings should be interpreted as indicative. Formal diagnostic interviews offer a more definitive diagnosis; however, this presents logistical challenges for large studies. As pre-pandemic data were not collected, we are unable to compare with ‘usual’ levels of distress and quantify the influence of the pandemic on the reported scores, yet because of the longitudinal nature of the study, we can reliably report an increasing trend of distress and rates above normative data at each time point.2 , 3

Our findings show that rates of psychological distress and trauma in doctors increased further during January 2021 compared with the initial pandemic peak (April 2020). These findings raise significant concerns regarding the psychological capacity of the acute care workforce for future pandemic phases, which may exacerbate already existing workforce crises.14 Contrary to previous findings, we found no evidence that the process of natural recovery, immersive pandemic working, or increasing therapeutic options for pandemic illness led to any mitigation in the prevalence of psychological distress.

These findings provide contemporary evidence that there is a significant cohort of doctors who continue to experience high levels of distress and trauma throughout every phase of the pandemic. It is vital that those in distress are identified and fully supported via evidence-based therapies to prevent long-term sequelae; the potential impact on workforce attrition and longer-term mental health is likely to become unmanageable without imminent strategic action.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2021.05.017.

Contributor Information

TERN:

L. Kane, L. Mackenzie, S. Sharma Hajela, J. Phizacklea, K. Malik, N. Mathai, A. Sattout, S. Messahel, E. Fadden, R. McQuillan, B. O'Hare, S. Lewis, D. Bewick, R. Taylor, I. Hancock, D. Manthalapo Ramesh Babu, S. Hartshorn, M. Williams, A. Charlton, L. Somerset, C. Munday, A. Turner, R. Sainsbury, E. Williams, S. Patil, R. Stewart, M. Winstanley, N. Tambe, C. Magee, D. Raffo, D. Mawhinney, B. Taylor, T. Hussan, G. Pells, F. Barham, F. Wood, C. Szekeres, R. Greenhalgh, S. Marimuthu, R. Macfarlane, M. Alex, B. Shrestha, L. Stanley, J. Gumley, K. Thomas, M. Anderson, C. Weegenaar, J. Lockwood, T. Mohamed, S. Ramraj, M. Mackenzie, A. Robertson, W. Niven, M. Patel, S. Subramaniam, C. Holmes, S. Bongale, U. Bait, S. Nagendran, S. Rao, F. Mendes, P. Singh, S. Subramaniam, T. Baron, C. Ponmani, M. Depante, R. Sneep, A. Brookes, S. Williams, A. Rainey, J. Brown, N. Marriage, S. Manou, S. Hart, M. Elsheikh, L. Cocker, M.H. Elwan, K.L. Vincent, C. Nunn, N. Sarja, M. Viegas, E. Wooffinden, C. Reynard, N. Cherian, A. Da-Costa, S. Duckitt, J. Bailey, L. How, T. Hine, F. Ihsan, H. Abdullah, K. Bader, S. Pradhan, M. Manoharan, L. Kehler, R. Muswell, M. Bonsano, J. Evans, E. Christmas, K. Knight, L. O'Rourke, K. Adeboye, K. Iftikhar, R. Evans, R. Darke, R. Freeman, E. Grocholski, K. Kaur, H. Cooper, M. Mohammad, L. Harwood, K. Lines, C. Thomas, D. Ranasinghe, S. Hall, J. Wright, S. Hall, N. Ali, J. Hunt, H. Ahmad, C. Ward, M. Khan, K. Holzman, J. Ritchie, A. Hormis, R. Hannah, A. Corfield, J. Maney, D. Metcalfe, S. Timmis, C. Williams, R. Newport, D. Bawden, A. Tabner, H. Malik, C. Roe, D. McConnell, F. Taylor, R. Ellis, S. Morgan, L. Barnicott, S. Foster, J. Browning, L. McCrae, E. Godden, A. Saunders, A. Lawrence-Ball, R. House, J. Muller, I. Skene, M. Lim, H. Millar, A. Rai, K. Challen, S. Currie, M. Elkanzi, T. Perry, W. Kan, L. Brown, M. Cheema, A. Clarey, A. Gulati, K. Webster, A. Howson, R. Doonan, C. Magee, A. Trimble, C. O’Connell, R. Wright, E. Colley, C. Rimmer, S. Pintus, H. Jarman, V. Worsnop, S. Collins, M. Colmar, N. Masood, R. McLatchie, A. Peasley, S. Rahman, N. Mullen, L. Armstrong, A. Hay, R. Mills, J. Lowe, H. Raybould, A. Ali, P. Cuthbert, S. Taylor, V. Talwar, Z. Al-Janabi, C. Leech, J. Turner, L. McKechnie, B. Mallon, J. McLaren, Y. Moulds, L. Dunlop, F.M. Burton, S. Keers, L. Robertson, D. Craver, N. Moultrie, O. Williams, S. Purvis, M. Clark, C. Davies, S. Foreman, C. Ngua, J. Morgan, N. Hoskins, J. Fryer, R. Wright, L. Frost, P. Ellis, A. Mackay, K. Gray, M. Jacobs, I. Musliam Veettil Asif, P. Amiri, S. Shrivastava, F. Raza, S. Wilson, M. Riyat, H. Knott, M. Ramazany, S. Langston, N. Abela, L. Robinson, D. Maasdorp, H. Murphy, H. Edmundson, R. Das, C. Orjioke, D. Worley, W. Collier, J. Everson, N. Maleki, A. Stafford, S. Gokani, M. Charalambos, A. Olajide, C. Bi, J. Ng, S. Naeem, A. Hill, and C. Boulind

I-TERN:

R. O'Sullivan, S. Gilmartin, S. Uí Bhroin, P. Fitzpatrick, A. Patton, M. Jee Poh Hock, S. Graham, S. Kukaswadia, C. Prendergast, A. Ahmed, C. Dalla Vecchia, J. Lynch, M. Grummell, I. Grossi, and B. MacManus

RAFT, TRIC and SATURN Collaborators:

P. Turton, C. Battle, K. Samuel, A. Boyle, A. Waite, D. George, B. Johnston, J. Anandarajah, and J. Vinagre

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Mai Baquedano (University of Bristol) for her support with REDCap and GL Assessments for providing the licence for the GHQ-12 free of charge. We would like to extend a special thanks to all contributors to this study (listed in Supplementary 4), without whom it would not have been possible.

Declarations of interest

Many of the authors have been working as frontline clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. They declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Deaths | Coronavirus in the UK. Available from: https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/deaths (accessed 19 April 2021).

- 2.Roberts T., Daniels J., Hulme W., et al. Psychological distress during the acceleration phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of doctors practising in emergency medicine, anaesthesia and intensive care medicine in the UK and Ireland. Emerg Med J. 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2020-210438. 0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts T, Daniels J, Hulme W, et al. Psychological distress and trauma in doctors providing frontline care during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom and Ireland: a prospective longitudinal survey cohort study. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3760472 (accessed 25 January 2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Lee M.C.C., Thampi S., Chan H.P., et al. Psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic amongst anaesthesiologists and nurses. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:e384–e386. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ffrench-O’Carroll R., Feeley T., Tan M.H., et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on staff working in paediatric and adult critical care. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126:e39–e41. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sneyd J.R., Mathoulin S.E., O'Sullivan E.P., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on anaesthesia trainees and their training. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:450–455. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jotwani R., Cheung C.A., Hoyler M.M., et al. Trial under fire: one New York City anaesthesiology residency programme’s redesign for the COVID-19 surge. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:e386–e388. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.06.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts T., Daniels J., Hulme W., et al. COVID-19 emergency response assessment study: a prospective longitudinal survey of frontline doctors in the UK and Ireland: study protocol. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg D.P., Gater R., Sartorius N., et al. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol Med. 1997;27:191–197. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss D.S., Marmar C.R. In: Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. Wilson J.P., Keane T.M., editors. Guilford Press; New York: 1997. The impact of event scale—revised; pp. 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Minor B.L., et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95 doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.R Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna: 2018. A language and environment for statistical computing. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwanten L.E. The UK anaesthesia workforce is in deepening crisis. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126:e159–e161. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.