Abstract

Narrowing of arteries supplying blood to the limbs provokes critical hindlimb ischemia (CLI). Although CLI results in irreversible sequelae, such as amputation, few therapeutic options induce the formation of new functional blood vessels. Based on the proangiogenic potentials of stem cells, in this study, it was examined whether a combination of dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) could result in enhanced therapeutic effects of stem cells for CLI compared with those of DPSCs or HUVECs alone. The DPSCs+ HUVECs combination therapy resulted in significantly higher blood flow and lower ischemia damage than DPSCs or HUVECs alone. The improved therapeutic effects in the DPSCs+ HUVECs group were accompanied by a significantly higher number of microvessels in the ischemic tissue than in the other groups. In vitro proliferation and tube formation assay showed that VEGF in the conditioned media of DPSCs induced proliferation and vessel-like tube formation of HUVECs. Altogether, our results demonstrated that the combination of DPSCs and HUVECs had significantly better therapeutic effects on CLI via VEGF-mediated crosstalk. This combinational strategy could be used to develop novel clinical protocols for CLI proangiogenic regenerative treatments.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Combination, Critical hindlimb ischemia, Dental pulp stem cells, Human umbilical vein endothelial cells

INTRODUCTION

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is a common circulatory problem involving narrowed arteries and reduced blood flow to the limbs. Critical hindlimb ischemia (CLI) is the most severe clinical manifestation of PAD (1); it can lead to ischemic nonhealing ulcers on the leg and feet and subsequent amputation to prevent secondary damage (2). The current CLI therapies include intra-arterial stent and bypass surgery (3, 4). However, they have a high risk of restenosis (5), because they only unclog blood vessels without inducing angiogenesis. Therefore, novel CLI therapeutics that can induce the new functional blood vessels formation are needed.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are the most widely used stem cells for regenerative medicine globally (6, 7). Given that the developmental origin of MSCs might be the perivascular region, their potential applications for angiogenesis have been suggested (8). Accordingly, MSCs are undergoing Phase I or II clinical trials for CLI at several clinical sites (9, 10). However, it is still controversial whether MSCs can differentiate into functional endothelial cells, which is an essential component for angiogenesis (11). Instead, many studies have proposed that there are paracrine pro-angiogenic effects of MSCs (12, 13). Therefore, co-injection of MSCs and endothelial cells (ECs) might enhance the therapeutic effects of MSCs for CLI.

Dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) from dental pulp show MSC-like characteristics and have several advantages for use in CLI (14, 15). Most importantly, DPSCs have shown significant therapeutic efficacy in preclinical animal models for a wide range of conditions, including spinal cord injury, ischemic stroke, and CLI, that require angiogenesis as a recovery mechanism (16-18). Moreover, the combination of DPSCs and ECs has shown improved regenerative potentials in various pathological conditions (19-21). DPSCs could be collected from extracted infantile teeth and stored for a long time, which would enable autografts of DPSCs for CLI patients (22). Since survival of transplanted cells is important for making functional vessels with anastomosis in the host (23), autografts would be the most clinically applicable option to transplant stem cells.

The objectives of this study were to compare the therapeutic effects of DPSCs and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) co-injection in a CLI animal model with those of DPSCs or HUVECs injection alone and to elucidate molecular mechanisms of treatment effects.

RESULTS

Therapeutic effects of DPSCs and HUVECs in CLI animal model

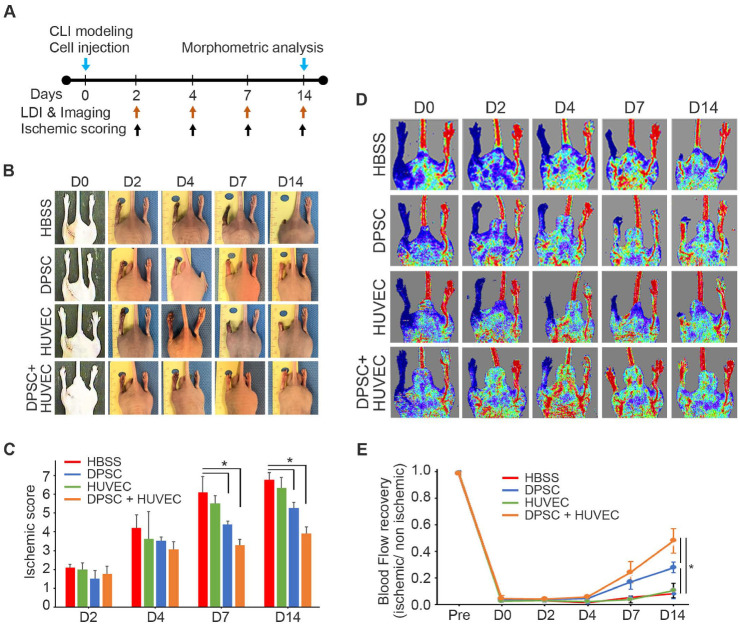

To evaluate their therapeutic effects, HBSS (negative control), HUVECs, DPSCs, or DPSCs + HUVECs (1:1) were transplanted into CLI animal models (1.0 × 106 cells/ea), intramuscularly, after ligation of the femoral artery (Supplementary Fig. 1). MSC-like characteristics of DPSCs, such as bipolar morphology (Supplementary Fig. 2A), expression of MSC-specific markers (Supplementary Fig. 2B), and differentiation potential (Supplementary Fig. 2C) were confirmed. Ischemia damage score and blood flow were evaluated by observation and laser doppler imaging (LDI), respectively, at 0, 2, 4, 7, and 14 days post-injection (Fig. 1A). Images of the legs (Fig. 1B) revealed that the degree of ischemia damage in the DPSCs + HUVECs group was the lowest among the experimental groups, although both the DPSCs and DPSCs + HUVECs groups showed significantly lower scores compared with the HBSS negative control group (Fig. 1C). LDI showed that HBSS or HUVECs injection produced significantly less blood flow compared to DPSCs injection or DPSCs and HUVECs co-injection (Fig. 1D). However, although the DPSCs group showed recovered blood flow at 14 days, DPSCs and HUVECs co-injection resulted in significantly higher blood flow than DPSCs injection (Fig. 1E) at 14 days post-injection. These data suggested that co-injection of DPSCs and HUVECs had significantly greater therapeutic effects on CLI animal model than HBSS, DPSCs, or HUVECs injection.

Fig. 1.

Therapeutic effects of DPSCs and/or HUVECs transplantation for CLI. (A) Experimental schedule. (B) Leg images of CLI animal models. (C) The degree of the legs damages were analyzed and compared. n = 10 for each group. *P < 0.05. (D) Blood flow in the legs of CLI animal models was measured by LDI. (E) The blood flow was analyzed and compared. n = 10 for each group. *P < 0.05.

Treatment mechanisms of DPSCs and HUVECs co-injection in CLI animal model

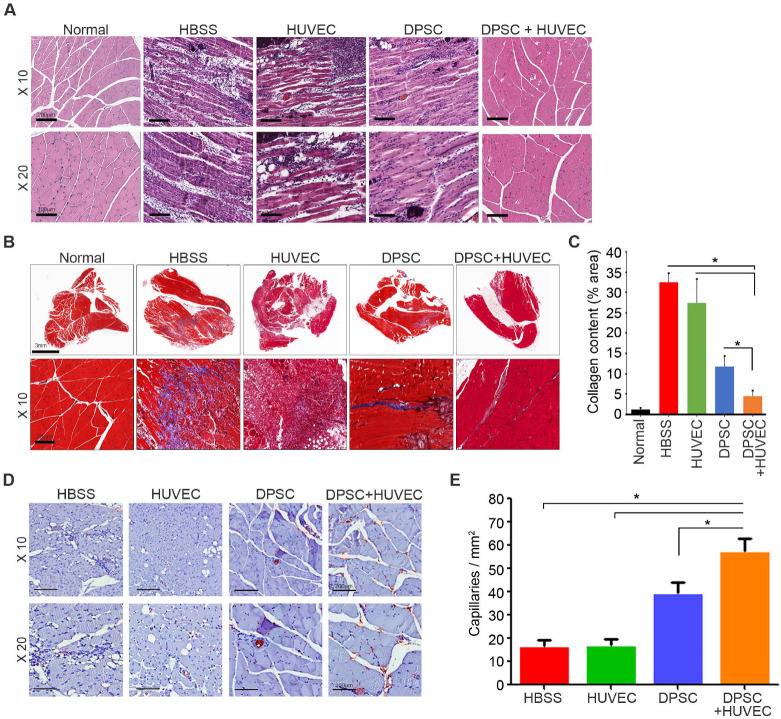

To measure the degree of fibrosis and angiogenesis, ischemic hindlimb muscles for animals in the four experimental groups were removed at 14 days post-injection. After hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, the degree of inflammation and integrity of the muscles were analyzed. In the HBSS group, there was severe inflammation with numerous infiltrated leukocytes. The severity of inflammation in the HUVECs group was similar to that in the HBSS group. In the DPSCs and DPSCs + HUVECs groups, there was less inflammation and damaged muscles than in the other groups (Fig. 2A). The degree of fibrosis was further confirmed by Masson’s trichrome staining (Fig. 2B), which showed that the degree of fibrosis decreased significantly with the co-injection of DPSCs and HUVECs, followed by DPSCs, HUVECs, and HBSS injection. Notably, the degree of fibrosis in the DPSCs + HUVECs group was significantly lower than that of the DPSCs group (Fig. 2C). The number of microvessels was quantified by immunohistochemistry against CD31. As shown in Fig. 2D, the highest number of microvessels was observed in the DPSCs and HUVECs co-injection group. In addition, the microvessels quantification results showed that the co-injection group had significantly more microvessels than did the HBSS, HUVECs, or DPSCs group (Fig. 2E). These results suggest that co-injection of DPSCs and HUVECs increased angiogenesis significantly and decreased inflammation and fibrosis of damaged muscles in the CLI animal models.

Fig. 2.

Histological analysis of CLI animal models. Ischemic hind limb muscles were retrieved at 14 days post-injection for histological analysis. (A) In the H&E staining, the severity of muscle degeneration and infiltration of immune cells were analyzed and compared. (B) The degree of fibrosis was assessed by Masson’s trichrome staining. (C) The fibrosis area was quantified from Masson’s trichrome staining and compared. (D) The number of vessels was assessed by immunohistochemistry against CD31. (E) The number of vessels was quantified and compared. n = 10 for each group. *P < 0.05.

Pro-angiogenic paracrine factors of DPSCs

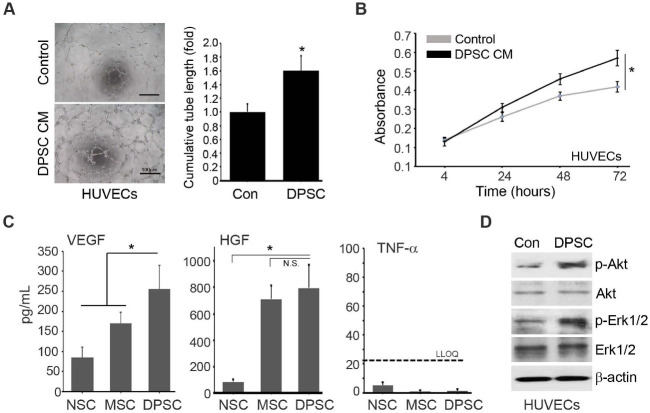

The combination of DPSCs and HUVECs significantly increased the number of microvessels (Fig. 2E) in the CLI animal models, which indicated that DPSCs might exert their therapeutic effects by promoting new vessel formation. In the in vitro tube formation assay, the conditioned media (CM) of DPSCs significantly increased the tube formation of HUVECs (Fig. 3A). Moreover, the in vitro proliferation of HUVECs was significantly induced by the CM of DPSCs (Fig. 3B). These results suggested that paracrine mediators of DPSCs provoke new vessel formation of HUVECs. Accordingly, high levels of pro-angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) were measured in the DPSCs CM by ELISA assay (Fig. 3C). Compared with the neural stem cells (NSCs) CM and Warton’s Jelly-derived MSCs (MSCs), the DPSCs CM showed a significantly higher level of VEGF. Although the concentrations of HGF in the CM of MSCs and DPSCs were the same, they were much higher than that of NSCs. In contrast, the levels of TNF-α were not different among the CM of NSCs, MSCs, and DPSCs (Fig. 3C). Functionally, phosphorylation of Akt and Erk1/2 in HUVECs was increased by the DPSCs CM treatment (Fig. 3D). These results indicated that the paracrine mediators from DPSCs such as VEGF and HGF mediate the pro-angiogenic effects of DPSCs.

Fig. 3.

Angiogenic paracrine effects of DPSCs CM. (A) Effects of the DPSCs CM on the HUVECs differentiation were analyzed by the in vitro tube formation assay. (B) Effects of the DPSCs CM on the proliferation of HUVECs were analyzed. (C) Concentration of VEGF, HGF, and TNF-α was quantified by ELISA. n = 10 for each group. *P < 0.05. n.s., not significant. LLOQ = lower limit of quantification. (D) Effects of the DPSCs CM on the HUVECs signaling path-ways were analyzed by western blot analysis.

Pro-angiogenic effects of DPSCs mediated by VEGF

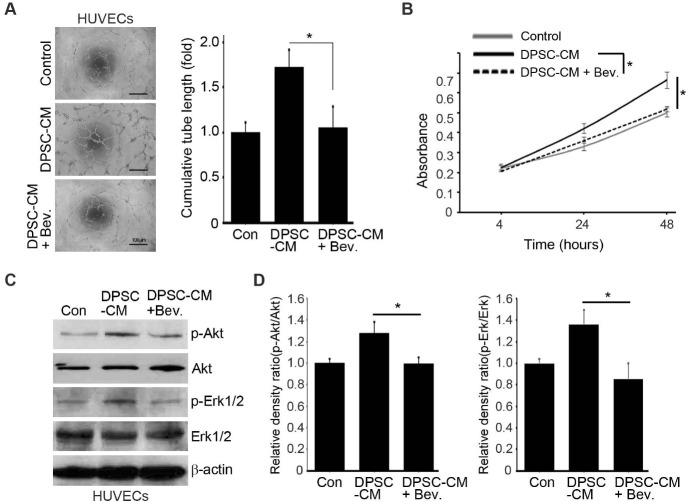

To confirm the paracrine mediator of pro-angiogenic activities of DPSCs, bevacizumab (Sigma-Aldrich), a VEGF-neutralizing antibody was used. When bevacizumab was added to the DPSCs CM, increased tube formation (Fig. 4A) and proliferation (Fig. 4B) of HUVECs by the DPSCs CM disappeared, which indicated that VEGF is the major paracrine factor that makes the pro-angiogenic effects of DPSCs. Accordingly, phosphorylation of Akt and Erk1/2 was not induced by the DPSCs CM when VEGF in the CM was neutralized by bevacizumab (Fig. 4C, D).

Fig. 4.

Proangiogenic effects of DPSCs mediated by VEGF. Effects of the DPSCs CM on differentiation (A), proliferation (B), and signaling pathways (C, D) of HUVECs with or without bevacizumab, a VEGF neutralizing antibody, were analyzed and compared. *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Stem cell therapies are emerging as alternative therapeutic options for CLI (24). MSCs are the most widely used stems cells in clinical trials for CLI, but the efficacy may not be enough to be developed commercially (25). In this study, we preclinically demonstrated that the therapeutic effects of stem cells can be potentiated significantly with a combination of two or more types of stem cells (26, 27). The use of multiple sources of stem cells might be inferior economically, which could be compensated by improved isolation and/or primary culture techniques.

Perivascular cell-like characteristics of MSCs (28) can be identified by the expression of pericyte markers, such as NG2, PDGFRβ, CD146, and α-SMA (29). In this study, DPSCs were also demonstrated to have perivascular cell-like characteristics that may be played important roles in in vitro and in vivo angiogenesis. Our findings suggested that DPSCs alone could not create functional microvessels in vitro and in vivo, this was in agreement with a previous report (30), which suggested that paracrine effects of DPSCs might not be enough to treat CLI. In contrast, when DPSCs and HUVECs were co-injected into CLI animal models, they provoked significantly increased numbers of microvessel-like structures. These results are in agreement with a previous report (31). A previous report has suggested that VEGF/VEGFR, PDGF-BB/PDGFR-α, and/or SDF-1/CXCR4 axis might relay communication between DPSCs and HUVECs (23). In this research, VEGF might be the critical paracrine factor, which mediates the paracrine pro-angiogenic activities of DPSCs.

The injection route of stem cells is important clinically, since it can affect the efficacy of stem cells (32). In the CLI clinical trials, stem cells were transplanted via intramuscular or intra-arterial injection routes. In this study, DPSCs and HUVECs were transplanted intramuscularly at three points (Supplementary Fig. 1). Weak points of intramuscular injection include possible leakage, uneven injection, and differences in injection sites across diverse patients’ body sizes. On the other hand, intra-arterial injection carries the danger of a surgical procedure under anesthesia. Moreover, injected stem cells might act as a new embolus to induce new intraarterial blockages. After optimization, intramuscular transplantation methods will be available for CLI clinical trials.

The number of injected stem cells is another clinical trial challenge, because the efficacy of stem cells could increase with the number of transplanted cells. The human equivalent dose of a chemical drug can be calculated by converting preclinical doses to those of humans based on a simple equation (33). However, it is not simple to convert a preclinical dose of stem cells into that of clinical trials, because they do not dissolve in the blood. In addition, they have different pharmaco-kinetics compared with those of chemical drugs. Using the same calculation method used for chemical drugs, the number of co-injected DPSCs and HUVECs in this study (1 × 106 cells for a 20-gram mouse) could be translated into 5 × 108 cells for a 60 kg patient.

Presently, more than 12 clinical trials of CLI cell therapies can be found at ClinicalTrial.gov. In those trials, different types of cells have been hired. However, in most trials, a single type of stem cell or cells was transplanted for CLI patients. One clinical trial for CLI (NCT00390767) reported using ECs and smooth muscle cells (SMCs) simultaneously (34), which are isolated from patients’ own short vein segments. Those ECs and SMCs are genetically modified to express angiopoietin I and VEGF, respectively. The genetic modifications might increase paracrine interactions between two types of cells or activate patients’ residual stem cells (35). However, the technique has its own disadvantages, such as potential mutagenesis and continuous systemic release of growth factors, which might provoke cells transformation (36).

Autologous transplantation of stem cells can minimize immune rejection, which could induce restenosis of vessels and/or secondary inflammation. It is more important in the treatment of CLI, since vessels continuously interact with circulating immune cells (37). Although autologous HUVECs can be isolated at birth, ECs are hard to isolate from older patients. In several preclinical studies, ECs were derived from human-induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) (38). However, iPSCs could be an adequate source of autologous ECs when their safety issues, such as teratoma formation after transplantation, are addressed properly (39). Direct conversion could be another solution to acquire autologous ECs (40). Despite the immunological pros of autograft, the properties of DPSCs and ECs from various individuals could be different, leading to unequal therapeutic effects. Those inconsistencies need to be overcome using potency factors (i.e., VEGF) that guarantee the therapeutic potentials of stem cells.

In this study, we demonstrated that DPSCs and HUVECs co-injection has significantly better therapeutic effects on CLI than DPSCs or HUVECs injection alone. The difference could originate from induced angiogenesis by the interaction between DPSCs and HUVECs, which might be mediated by VEGF from DPSCs. The combination strategy for CLI treatment in this study could be used in the development of clinical trial protocols for more effective CLI therapeutic agents.

Study approval

The use of DPSCs was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center (SMC, Seoul, South Korea) (IRB File No. SMC 2016-09-120). Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Samsung Biomedical Research Institute (SBRI, Seoul, South Korea), approval number 20180813001.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Further detailed information is provided in the Supplementary Information.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was funded by the National Research Foundation (NRF-2016R1A5A2945889, NRF-2019R1I1A1A01059158, and NRF-2020R1F1A1073261) and Korea Basic Science Institute (2020R1A6C101A191).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicting interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sprengers RW, Moll FL, Verhaar MC. Stem cell therapy in PAD. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39 Suppl 1:S38–S43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johannesson A, Larsson GU, Ramstrand N, Turkiewicz A, Wirehn AB, Atroshi I. Incidence of lower-limb amputation in the diabetic and nondiabetic general population: a 10-year population-based cohort study of initial unilateral and contralateral amputations and reamputations. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:275–280. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adam DJ, Beard JD, Cleveland T, et al. Bypass versus angioplasty in severe ischaemia of the leg (BASIL): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1925–1934. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67704-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farber A, Rosenfield K, Menard M. The BEST-CLI trial: a multidisciplinary effort to assess which therapy is best for patients with critical limb ischemia. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;17:221–224. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kechagias A, Ylonen K, Kechagias G, Juvonen T, Biancari F. Limits of infrainguinal bypass surgery for critical leg ischemia in high-risk patients (Finnvasc score 3-4) Ann Vasc Surg. 2012;26:213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buckley RH. A historical review of bone marrow transplantation for immunodeficiencies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:793–800. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.01.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin I, De Boer J, Sensebe L, Therapy MSCCotISfC. A relativity concept in mesenchymal stromal cell manufacturing. Cytotherapy. 2016;18:613–620. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Khaldi A, Al-Sabti H, Galipeau J, Lachapelle K. Therapeutic angiogenesis using autologous bone marrow stromal cells: improved blood flow in a chronic limb ischemia model. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:204–209. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)04291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diez-Tejedor E, Gutierrez-Fernandez M, Martinez-Sanchez P, et al. Reparative therapy for acute ischemic stroke with allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells from adipose tissue: a safety assessment: a phase II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single-center, pilot clinical trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:2694–2700. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta PK, Chullikana A, Parakh R, et al. A double blind randomized placebo controlled phase I/II study assessing the safety and efficacy of allogeneic bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cell in critical limb ischemia. J Transl Med. 2013;11:143. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vittorio O, Jacchetti E, Pacini S, Cecchini M. Endothelial differentiation of mesenchymal stromal cells: when traditional biology meets mechanotransduction. Integr Biol (Camb) 2013;5:291–299. doi: 10.1039/C2IB20152F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi M, Lee HS, Naidansaren P, et al. Proangiogenic features of Wharton's jelly-derived mesenchymal stromal/ stem cells and their ability to form functional vessels. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45:560–570. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoch AI, Binder BY, Genetos DC, Leach JK. Differentiation-dependent secretion of proangiogenic factors by mesenchymal stem cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bronckaers A, Hilkens P, Fanton Y, et al. Angiogenic properties of human dental pulp stem cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Estrela C, Alencar AH, Kitten GT, Vencio EF, Gava E. Mesenchymal stem cells in the dental tissues: perspectives for tissue regeneration. Braz Dent J. 2011;22:91–98. doi: 10.1590/S0103-64402011000200001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leong WK, Henshall TL, Arthur A, et al. Human adult dental pulp stem cells enhance poststroke functional recovery through non-neural replacement mechanisms. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2012;1:177–187. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2011-0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mamidi MK, Pal R, Dey S, et al. Cell therapy in critical limb ischemia: current developments and future progress. Cytotherapy. 2012;14:902–916. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2012.693156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakai K, Yamamoto A, Matsubara K, et al. Human dental pulp-derived stem cells promote locomotor recovery after complete transection of the rat spinal cord by multiple neuro-regenerative mechanisms. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:80–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI59251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dissanayaka WL, Zhan X, Zhang C, Hargreaves KM, Jin L, Tong EHJJoe. Coculture of dental pulp stem cells with endothelial cells enhances osteo-/odontogenic and angiogenic potential in vitro. 2012;38:454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dissanayaka WL, Hargreaves KM, Jin L, Samaranayake LP, Zhang CJTEPA. The interplay of dental pulp stem cells and endothelial cells in an injectable peptide hydrogel on angiogenesis and pulp regeneration in vivo. 2015;21:550–563. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2014.0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Liu J, Zou T, et al. DPSCs treated by TGF-β1 regulate angiogenic sprouting of three-dimensionally co-cultured HUVECs and DPSCs through VEGF-Ang-Tie2 signaling. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12:281. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02349-y.2a17f9edb13e41b2923f6b5e180cfabc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volponi AA, Pang Y, Sharpe PT. Stem cell-based biological tooth repair and regeneration. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nam H, Kim GH, Bae YK, et al. Angiogenic capacity of dental pulp stem cell regulated by SDF-1alpha-CXCR4 axis. Stem Cells Int. 2017;2017:8085462. doi: 10.1155/2017/8085462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta NK, Armstrong EJ, Parikh SA. The current state of stem cell therapy for peripheral artery disease. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2014;16:447. doi: 10.1007/s11886-013-0447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liew A, O'Brien T. Therapeutic potential for mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in critical limb ischemia. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2012;3:28. doi: 10.1186/scrt119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bak S, Ahmad T, Lee YB, Lee JY, Kim EM, Shin H. Delivery of a cell patch of cocultured endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells using thermoresponsive hydrogels for enhanced angiogenesis. Tissue Eng Part A. 2016;22:182–193. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2015.0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ban DX, Ning GZ, Feng SQ, et al. Combination of activated Schwann cells with bone mesenchymal stem cells: the best cell strategy for repair after spinal cord injury in rats. Regen Med. 2011;6:707–720. doi: 10.2217/rme.11.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi S, Gronthos S. Perivascular niche of postnatal mesenchymal stem cells in human bone marrow and dental pulp. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:696–704. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.4.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crisan M, Corselli M, Chen WC, Peault B. Perivascular cells for regenerative medicine. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16:2851–2860. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2012.01617.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee KH, Pyeon HJ, Nam H, et al. Significant therapeutic effects of adult human multipotent neural cells on spinal cord injury. Stem Cell Res. 2018;31:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dissanayaka WL, Hargreaves KM, Jin L, Samaranayake LP, Zhang C. The interplay of dental pulp stem cells and endothelial cells in an injectable peptide hydrogel on angiogenesis and pulp regeneration in vivo. Tissue Eng Part A. 2015;21:550–563. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2014.0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Tongeren RB, Hamming JF, Fibbe WE, et al. Intramuscular or combined intramuscular/intra-arterial administration of bone marrow mononuclear cells: a clinical trial in patients with advanced limb ischemia. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2008;49:51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reagan-Shaw S, Nihal M, Ahmad N. Dose translation from animal to human studies revisited. FASEB J. 2008;22:659–661. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9574LSF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flugelman MY, Halak M, Yoffe B, et al. Phase Ib safety, two-dose study of MultiGeneAngio in patients with chronic critical limb ischemia. Mol Ther. 2017;25:816–825. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2016.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lucitti JL, Mackey JK, Morrison JC, Haigh JJ, Adams RH, Faber JE. Formation of the collateral circulation is regulated by vascular endothelial growth factor-A and a disintegrin and metalloprotease family members 10 and 17. Circ Res. 2012;111:1539–1550. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.279109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Griffin M, Greiser U, Barry F, O'Brien T, Ritter T. Genetically modified mesenchymal stem cells and their clinical potential in acute cardiovascular disease. Discov Med. 2010;9:219–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tateishi-Yuyama E, Matsubara H, Murohara T, et al. Therapeutic angiogenesis for patients with limb ischaemia by autologous transplantation of bone-marrow cells: a pilot study and a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:427–435. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09670-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jang S, Collin de l'Hortet A, Soto-Gutierrez A. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells: overview, current advances, applications, and future directions. Am J Pathol. 2019;189:502–512. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuroda T, Yasuda S, Sato Y. Tumorigenicity studies for human pluripotent stem cell-derived products. Biol Pharm Bull. 2013;36:189–192. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b12-00970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ginsberg M, James D, Ding BS, et al. Efficient direct reprogramming of mature amniotic cells into endothelial cells by ETS factors and TGFbeta suppression. Cell. 2012;151:559–575. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.