Abstract

Background:

High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) and noninvasive ventilation (NIV) are important treatment approaches for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure (AHRF) in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients. However, the differential impact of HFNC versus NIV on clinical outcomes of COVID-19 is uncertain.

Objectives:

We assessed the effects of HFNC versus NIV (interface or mode) on clinical outcomes of COVID-19.

Methods:

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus, MedRxiv, and BioRxiv for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies (with a control group) of HFNC and NIV in patients with COVID-19-related AHRF published in English before February 2022. The primary outcome of interest was the mortality rate, and the secondary outcomes were intubation rate, PaO2/FiO2, intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay (LOS), hospital LOS, and days free from invasive mechanical ventilation [ventilator-free day (VFD)].

Results:

In all, 23 studies fulfilled the selection criteria, and 5354 patients were included. The mortality rate was higher in the NIV group than the HFNC group [odds ratio (OR) = 0.66, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.51–0.84, p = 0.0008, I2 = 60%]; however, in this subgroup, no significant difference in mortality was observed in the NIV-helmet group (OR = 1.21, 95% CI: 0.63–2.32, p = 0.57, I2 = 0%) or NIV-continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) group (OR = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.51–1.17, p = 0.23, I2 = 65%) relative to the HFNC group. There were no differences in intubation rate, PaO2/FiO2, ICU LOS, hospital LOS, or days free from invasive mechanical ventilation (VFD) between the HFNC and NIV groups.

Conclusion:

Although mortality was lower with HFNC than NIV, there was no difference in mortality between HFNC and NIV on a subgroup of helmet or CPAP group. Future large sample RCTs are necessary to prove our findings.

Registration:

This systematic review and meta-analysis protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (no. CRD42022321997).

Keywords: CPAP, COVID-19, helmet, high-flow nasal cannula, noninvasive mechanical ventilation

Introduction

Patients infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) may develop coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with viral pneumonia, acute hypoxemic respiratory failure (AHRF), or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and may require hospital admission.1–3 About 15–30% of COVID-19 patients experience hypoxemia and progress to ARDS. 4 These patients require oxygen and possibly ventilatory support, which can be delivered using different devices. Noninvasive oxygenation strategies, such as high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) and noninvasive ventilation (NIV), have been widely adopted in patients with AHRF secondary to COVID-19.5,6

HFNC is a noninvasive respiratory support modality that delivers warm, humidified oxygen at a maximum flow rate of 60–100 l/min and up to 100% of the inspired oxygen fraction (FiO2) through nasal probes. 7 NIV refers to the application of mechanical ventilatory support using a nasal, oronasal, or full face mask or a helmet. 8 HFNC and NIV are the main forms of treatment for AHRF and associated with favorable outcomes in COVID-19 patients. 9 Many recent studies have compared the effects of HFNC and NIV in COVID-19 patients, but the use of HFNC versus NIV for COVID-19-related AHRF remains controversial.5,6 Current clinical practice is based on prior experience, personal medical opinion, and local availability. Therefore, this meta-analysis compared HFNC versus NIV with respect to the risk for mortality and intubation in patients with COVID-19-related AHRF.

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations. 10 PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus, ClinicalTrials.gov, MedRxiv, BioRxiv, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched for relevant studies published before February 2022. Two trained investigators (W.T. and Y.P.) independently performed the searches, screening, and identification. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus.

The search combinations adopted were as follows: (‘Ventilation, Noninvasive’ OR ‘Non Invasive Ventilation’ OR ‘Ventilation, Non Invasive’ OR ‘Noninvasive Ventilation’) OR (‘HFNC’ OR ‘high-flow nasal cannula’ OR ‘high-flow nasal oxygen’ OR ‘high-flow oxygen’) AND ( ‘COVID 19’ OR ‘SARS CoV 2’ OR ‘2019 Novel Coronavirus’ OR ‘2019 nCoV’ OR ‘Coronavirus Disease 2019’ OR ‘Coronavirus Disease 19’ OR ‘Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection’ OR ‘SARS Coronavirus 2 Infection’ OR ‘COVID 19 Pandemic OR COVID-19’). In addition, the reference lists of all primary studies and review articles were evaluated to locate additional relevant studies.

Study selection

The inclusion criteria were as follows: randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies; adult patients (⩾18 years old) with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19; HFNC compared with a control group receiving NIV; and outcomes, including aggregated mortality rate, intubation rate, or both.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: patients who did not meet the screening criteria; studies that were not in English or commentaries, reviews, or duplicate publications from the same study; and data that could not be extracted by the reported statistical methods or non-targeted outcomes.

The ultimate decision to include or exclude any study was made following a full-text review of the article by two investigators (W.T. and Y.P.) focusing on publication date, study type, study design, and outcomes. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

The primary outcome of interest was the mortality rate, and the secondary outcomes were the intubation rate, PaO2/FiO2, intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay (LOS), hospital LOS, and days free from invasive mechanical ventilation [ventilator-free day (VFD)].

Data extraction and study quality

Using a standardized form, two investigators (W.T. and Y.P.) independently extracted data with no blinding of trials (e.g. authors, institutions, or publication sources). Some data not provided in the published reports were obtained by contacting authors by email. To assess the quality of eligible RCTs, we used the Cochrane collaboration risk of bias tool, which considers allocation sequence generation, concealment of allocation, masking of participants and investigators, incomplete outcome reporting, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias. Potential sources of bias were graded as high, low, or unclear to assign the studies to high, low, or moderate risk of bias groups. The Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale (NOS) checklist was used to assess the quality of observational studies. Using this scale, each study was assessed on nine items and categorized into three groups, as follows: selection, comparability, and outcomes. Stars were awarded for each quality item, and the highest-quality studies were awarded nine stars. A study was considered to be of low, moderate, or high quality when it achieved 0–4, 5–7, or 8–9 stars, respectively.

Data synthesis and analysis

The meta-analysis was performed using available data from the primary studies with the RevMan Review Manager (version 5.4.1; Nordic Cochrane Review Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). Dichotomous outcomes are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Continuous outcomes are presented as weighted mean differences (MDs) and 95% CIs. Data were assessed in median-interquartile ranges and were transformed into standard mean difference formats for further comparison.

The results were analyzed using the random-effects model and are presented in a forest plot. The I2 statistical index (ranges from 0% to 100%) was used to measure heterogeneity among the studies in each analysis, with values of 25%, 50%, and 75% corresponding to degrees of low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. Publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot. In addition, subgroup analysis was performed to investigate the different effects of interface and mode of NIV on treatment outcomes. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to represent a significant difference.

Results

Search results

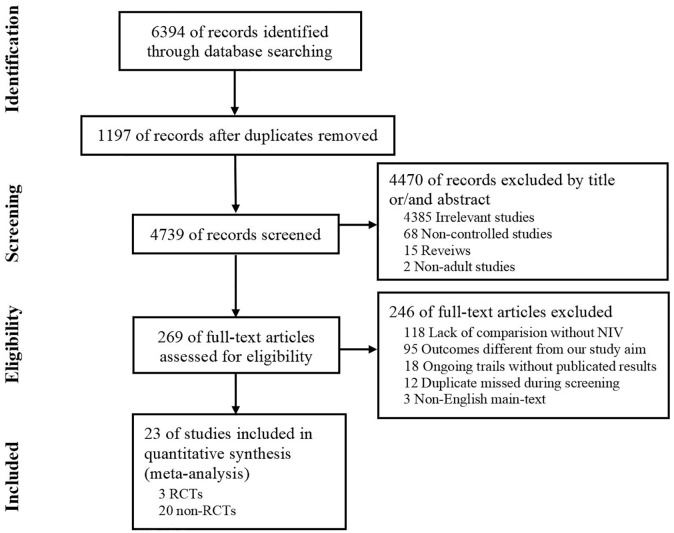

A total of 6394 relevant studies were obtained from the databases. After excluding duplicates and evaluating the full texts of articles, we identified 23 eligible studies9,11–32 (3 RCTs,20,24,26 8 prospective observational studies,13,16,18,19,22,25,28,30 and 12 retrospective observational studies).9,11,12,14,15,17,21,23,27,29,31,32 The process of searching and screening is described in Figure 1. The main characteristics of the articles included in the meta-analysis are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Author | Country | Study design | Setting | Study period | No. of patients Total (HFNC/NIV) |

Outcomes a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alharthy et al. 11 | Saudi Arabia | Retrospective observational study | ICU | As of 30 April 2020 | 30 (15/15) | ② |

| Alkouh et al. 12 | Morocco | Retrospective observational study | ICU | 1 March 2020–31 December 2021 | 233 (162/71) | ①② |

| Costa et al. 9 | Brazil | Retrospective observational study | ICU | March 2020–April 2020 | 37 (23/14) | ①②④⑤ |

| COVID-ICU group 13 | France, Belgium, Switzerland | Prospectively observational study | ICU | 25 February 2020–4 May 2020 | 725 (567/158) | ①②④⑤ |

| Duan et al. 14 | China | Retrospective observational study | Ward/ICU | January 2020–March 2020 | 36 (23/13) | ①②③ |

| Fernández et al. 15 | Spanish | Retrospective observational study | Ward/ICU | 1 March 2020–1 April 2020 | 594 (431/163) | ①② |

| Franco et al. 16 | Italy | Prospectively observational study | ED/ICU | 1 March 2021–1 April 2020 | 667 (163/507) | ①②⑤ |

| Gaulton et al. 17 | US (most) | Retrospective observational study | ICU | MD | 59 (42/17) | ①② |

| Ghani et al. 18 | UK | Prospectively observational study | Non-ICU | March 2020–January 2021 | 130 (35/95) | ①② |

| Gough et al. 19 | Ireland | Prospectively observational study | Non-ICU | March 2020–April 2020 | 117 (32/85) | ①② |

| Grieco et al. 20 | Italy | RCT, multicenter | ICU | October 2020–December 2020 | 109 (54/55) | ①②③④⑤⑥ |

| Mahroof et al. 21 | UK | Retrospective observational study | ICU | MD | 45 (32/13) | ② |

| Menga et al. 22 | Italy | Prospectively observational study | ICU | 12 March 2021–20 April 20 | 85 (24/61) | ② |

| Nadeem et al. 23 | UK | Retrospective observational study | RSU | 1 March 2020–28 February 2021 | 100 (44/56) | ① |

| Nair et al. 24 | India | RCT, single center | ICU | Auguts 2020–December 2020 | 109 (55/54) | ①②③⑤⑥ |

| Pearson et al. 25 | US | Prospectively observational study | ICU | 1 March 2020–31 July 2020 | 62 (31/31) | ①② |

| Perkins et al. 26 | UK | RCT | Non-ICU | MD | 797 (417/380) | ①②④ |

| Ranieri et al. 27 | Italy | Retrospective observational study | MD | February 2020–December 2020 | 315 (184/131) | ①② |

| Rodrigues Santos et al. 28 | Egypt | Retrospective observational study | ICU | May 2020–August 2020 | 63 (37/26) | ①②③ |

| Shoukri 29 | Portugal | Prospectively observational study | RICU | 18 November 2020–18 February 2021 | 190 (139/51) | ①②⑤ |

| Sykes et al. 30 | UK | Prospectively observational study | Non-ICU | April 2020–March 2021 | 140 (48/92) | ① |

| Wendel Garcia et al. 31 | Spain | Retrospective observational study | ICU | As of 1 October 2020 | 174 (87/87) | ①②④ |

| Wendel Garcia et al. 32 | Spain | Retrospective observational study | ICU | 14 March 2020–15 April 2020 | 540 (439/101) | ①②④⑥ |

ED, emergency department; HFNC, high-flow nasal cannula; ICU, intensive care unit; MD, missing data; NIV, noninvasive ventilation; No, number; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RICU, respiratory intermediate care units; RSU, respiratory support unit; UK, the United Kingdom; USA, the United States.

Outcome measures include: ① mortality rate; ② Intubation rate; ③ PaO2/FiO2; ④ ICU length of stay; ⑤ Hospital length of stay; and ⑥ days free from invasive mechanical ventilation.

| Author | HFNC | NIV | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Male % | BMI, kg/m2 | APACHE Ⅱ | SOFA | P/F, mmHg | Age | male% | BMI, kg/m2 | APACHE Ⅱ | SOFA | P/F, mmHg | |

| Alharthy et al. 11 | 46 (16.4) | 86.7 | 24.3 (7.4) | MD | 9 (1.6) | 217.7 (34.4) | 46.3 (13.9) | 80 | 24.3 (7.4) | MD | 9 (1.6) | 214.7 (30.3) |

| Alkouh et al. 12 | 66.32 (12.8) | 72.2 | 27.59 (4.7) | MD | MD | MD | 64.7 (14.97) | 69 | 27.5 (4.9) | MD | MD | MD |

| Costa et al. 9 | 65.3 (17.7) | 91.3 | 29.4 (5.5) | 11.2 (8.5) | 3.7 (5.7) | MD | 74.5 (19) | 35.7 | 32.4 (4.7) | 20.7 (12.4) | 2.7 (1) | MD |

| COVID-ICU group 13 | 63.7 (12.6) | 75 | 28 (4.5) | MD | 3 (1.5) | 105 (42.3) | 64.3 (12) | 71 | 28 (4.5) | MD | 2.7 (1.5) | 127.7 (62) |

| Duan et al. 14 | 50 (14) | 52 | MD | 10 (5) | 4 (2) | 165 (48) | 65 (14) | 92 | MD | 8 (2) | 4 (1) | 196 (46) |

| Fernández et al. 15 | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD |

| Franco et al. 16 | 65.7 (14.7) | 69.9 | MD | MD | 2.5 (0.9) | 166 (65) | 69.08 (12.6) | 69 | MD | MD | 3.5 (1.8) | 147 (82.4) |

| Gaulton et al. 17 | 61 (16) | 33.3 | 35.8 (9) | MD | MD | MD | 56 (15) | 82.3 | 34.8 (7.8) | MD | MD | MD |

| Ghani et al. 18 | MD | 68 | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | 68 | MD | MD | MD | MD |

| Gough et al. 19 | 74 (28.7) | 51.6 | 29.6 (7.8) | MD | MD | 180.3 (150) | 61.7 (13.6) | 43.4 | 30.2 (5.3) | MD | MD | 180.5 (101.3) |

| Grieco et al. 20 | 62 (10.7) | 84 | 28.3 (3.8) | MD | 2.3 (0.8) | 102 (33.5) | 65 (11.4) | 77 | 27.7 (3) | MD | 2.3 (0.8) | 104 (32) |

| Mahroof et al. 21 | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD |

| Menga et al. 22 | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD |

| Nadeem et al. 23 | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD | MD |

| Nair et al. 24 | 56.7 (13) | 80 | MD | MD | MD | 112.1 (36) | 56.2 (13) | 64.8 | MD | MD | MD | 115.3 (42) |

| Pearson et al. 25 | 66 (12.4) | 61.3 | 32.5 (9.5) | MD | 3 (1.6) | MD | 60.7 (18.7) | 81.3 | 27.7 (4.8) | MD | 2.3 (0.8) | MD |

| Perkins et al. 26 | 57.6 (13) | 65.2 | MD | MD | MD | 138.5 (87.6) | 56.7 (12.5) | 68.4 | MD | MD | MD | 131.8 (67.8) |

| Ranieri et al. 27 | 62.7 (12.7) | 78.3 | 27.7 (4.6) | MD | 3 (1.5) | 132.7 (41.8) | 66.3 (10.5) | 75.6 | 27.6 (3.2) | MD | 2.3 (0.7) | 148.7 (42.7) |

| Rodrigues Santos et al. 28 | 67.94 (7.82) | 62.2 | MD | 9.8 (3.2) | 3 (0.9) | 191.1 (37.8) | 64.1 (9.81) | 65.4 | MD | 11 (3.2) | 2.7 (0.8) | 190.38 (42.47) |

| Shoukri 29 | 65.7 (12.2) | 68.3 | 28.2 (5.7) | MD | MD | MD | 69.6 (10.2) | 68.6 | 29.5 (6.2) | MD | MD | MD |

| Sykes et al. 30 | 71.3 (13.9) | 75 | MD | MD | MD | 77.3 (38.2) | 70.7 (10.0) | 60 | MD | MD | MD | 76.0 (34.5) |

| Wendel Garcia et al. 31 | 64 (14.3) | 75 | 28 (5.3) | 9.7 (5.3) | 5.3 (3) | 124.7 (67.8) | 65.7 (15.8) | 71 | 26.3 (3.8) | 11 (6.8) | 5.7 (2.3) | 133.3 (53.5) |

| Wendel Garcia et al. 32 | 62 (11.9) | 68 | 28.3 (3.7) | MD | MD | MD | 61.7 (12) | 68 | 28.3 (3.8) | MD | MD | MD |

APACHE, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation; BMI, body mass index; HFNC, high-flow nasal cannula; MD, missing data; NIV, noninvasive ventilation; P/F, oxygenation index (PaO2/FiO2); SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment.

Values are given as mean (standard deviation).

| Author | HFNC | NIV | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Setting | Intervention | Duration, days | NIV mode | NIV interface | Setting | Intervention | Duration, days | |

| Alharthy et al. 11 | Mean flow rate, 60 l/min; median FiO2, 40% | Received HFNC | 9 (3.3) | CPAP | Helmet | Mean flow rate, 45 l/min; median FiO2, 40% | Received helmet-CPAP | 8.3 (4.1) |

| Alkouh et al. 12 | Flow rate, 60–80 l/min; FiO2, maintain SpO2 ⩾92% | Received HFNC | MD | MD | MD | MD | Received NIV | MD |

| Costa et al 9 | Flow rate, 40–50 l/min; FiO2, maintain SpO2 >92% | Received HFNC | MD | BiPAP | Face mask | PEE ⩾8 cmH2O; PS, for a TV ⩽8 ml/kg; FiO2, maintain SpO2 >92% | Received NIV | MD |

| COVID-ICU group 13 | Flow rate, 50 (40–60) l/min; FiO2, 70 (60–90) % | HFNC was the most invasive treatment | MD | MD | Face mask | PEEP, 7 (6–8) cmH2O; PS, 8 (6–10) cmH2O; FiO2, 60 (50–80)% | NIV was the most invasive treatment | MD |

| Duan et al. 14 | Flow rate: 30–60 l/min; FiO2, maintain SpO2 >93% | HFNC as first-line therapy | 4.5 (5.3) | CPAP/BiPAP | Face mask | Initial: CPAP or PEEP, 4 cmH2O; initial inspiratory pressure, 8–10 cmH2O; FiO2, maintain SpO2 >93% | NIV as first-line therapy | 7.1 (4.6) |

| Fernández et al. 15 | MD | HFNC only | CPAP/BiPAP | Face mask | MD | NIV and/or CPAP with or without HFNC | MD | |

| Franco et al. 16 | MD | Received HFNC | MD | CPAP/BiPAP | MD | MD | Received CPAP or NIV | MD |

| Gaulton, 202017 | Flow rate, 40–60 l/min; FiO2, maintain SpO2 >92% | HFNC as first-line therapy | MD | CPAP | Helmet | CPAP, 5–10 cmH2O; FiO2, maintain SpO2 >92% | Helmet as first-line therapy. Patients on helmet therapy were provided breaks with intervening HFNC use | MD |

| Ghani et al. 18 | Initial flow rate, 60 l/min; FiO2, maintain SpO2 92–96% | Received HFNC | MD | CPAP | Face mask | PEEP, 8 (6–12) cmH2O; FiO2, maintain SpO2 92–96% | Received CPAP | MD |

| Gough et al. 19 | Flow rate, capped at 30 l/min, limiting PEEP to < 3 cmH2O | Received HFNC | MD | CPAP | Face mask | PEEP ⩾ 10 cmH2O | Received CPAP | MD |

| Grieco et al. 20 | Initial flow rate, 60 l/min; FiO2, maintain SpO2 92–98% | Randomized | ⩾ 2 | BiPAP | Helmet | PEEP,10–12 cmH2O; initial PS, 10–12 cmH2O; FiO2, maintain SpO2 92–98% | Randomized. After interruption of NIV, patients underwent continuous Venturi mask or HFNC | ⩾ |

| Mahroof et al. 21 | MD | Initial mode of support was HFNC | MD | MD | MD | MD | Initial mode of support was NIV | MD |

| Menga et al. 22 | MD | HFNC as first-line treatment | MD | BiPAP | Helmet/ Face mask | MD | NIV as first-line treatment | MD |

| Nadeem et al. 23 | MD | Received HFNC | MD | CPAP/BiPAP | MD | MD | Received CPAP or NIV | MD |

| Nair et al. 24 | Initial: flow rate, 50 l/min; FiO2, 1.0, target SpO2 >94% | HFNC only | MD | BiPAP | MD | PEEP, 5–10 cmH2O; PS, 10–20 cmH2O; FiO2, 0.5–1.0, target SpO2 >94% | Received NIV | MD |

| Pearson et al. 25 | MD | HFNC as initial therapy | MD | CPAP | Helmet | MD | Helmet NIV as initial therapy | MD |

| Perkins et al. 26 | MD | Randomized. Crossover was observed between allocated treatment arms | 3.7 (4.1) | CPAP | Face mask | MD | Randomized. Crossover was observed between allocated treatment arms | 3.5 (4.6) |

| Ranieri et al. 27 | Flow rate, 55 (50–60) l/min | Patients initially treated for ⩾12 continuous hours with HFNC using gas flows ⩾40 l/min | MD | BiPAP | MD | PEEP, 10 (10–12) cmH2O PS, 10 (10–12) cmH2O | Patients initially treated with NIV with PEEP ⩾5 cmH2O | MD |

| Rodrigues Santos et al. 28 | Flow rate, 30–60 l/min; FiO2, maintain SpO2 >93% | HFNC as initial therapy | 5.53 (1.11) | BiPAP | Face mask | Initial PEEP, 4 cmH2O; initial inspiratory pressure, 8–10 cmH2O; FiO2, maintain SpO2 >93% | NIV as initial therapy | 5.86 (1.10) |

| Shoukri 29 | Maximum: flow, 59.2 (1.0) l/min; FiO2, 0.9 (0.1), SpO2, 92–96% | Received HFNC | 5.5 (4.4) | MD | Face mask | Maximum: CPAP/EPAP,10.0 (1.9) cmH2O; IPAP,14.8 (2.4) cmH2O; FiO2, 1.0 (0.1), SpO2, 92–96% | Received CPAP or NIV | 5.2 (4.3) |

| Sykes et al. 30 | Mean FiO2, 79.5 (23) % | HFNC was the highest level of treatment | 6 (9.8) | CPAP | Face mask | Mean FiO2, 83.8 (26.1) % | CPAP with or without HFNC | 9 (17.4) |

| Wendel Garcia et al. 31 | Flow rate >30 l/min; mean FiO2, 60 (44–80)% | HFNC was maximal respiratory support at ICU admission | MD | MD | MD | MD | NIV was maximal respiratory support at ICU admission | MD |

| Wendel Garcia et al. 32 | Flow rate >30 l/min; mean FiO2 ⩾50% | HFNC only | MD | MD | Face mask | Mean FiO2, at least 50% | NIV only | MD |

BiPAP, bi-level positive airway pressure; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; EPAP, expired positive airway pressure; FiO2, Fraction of inspiration O2; HFNC, high-flow nasal cannula; ICU, intensive care unit; IPAP, inspired positive airway pressure; MD, missing data; NIV, noninvasive ventilation; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; PS, pressure support; SpO2, oxygen saturation; TV, tidal volume.

Values are given as mean (standard deviation).

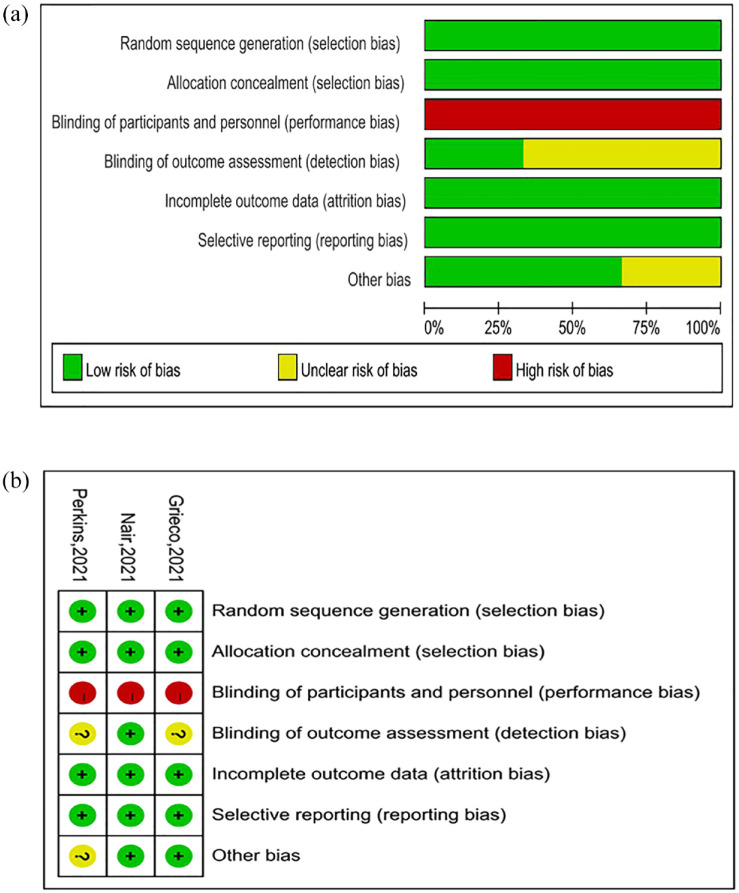

Literature quality and bias assessment

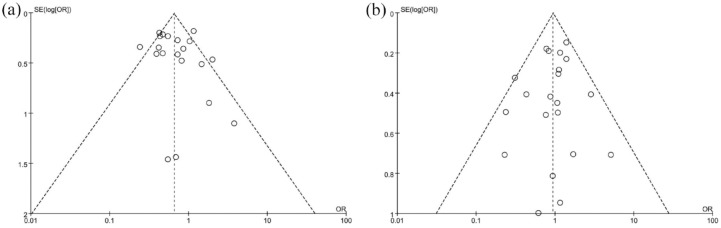

The quality evaluation results of the three RCTs20,24,26 are shown in Figure 2. None of the included studies were performed with double blinding. Two studies were considered to have an unclear risk of bias. The 20 observational9,11–19,21–23,25,27–32 studies were assessed using the NOS checklist, and the results are shown in the Table 2. All studies were of medium quality (⩾5 stars) or above, and 10 were considered high quality (⩾8 stars). We generated a funnel plot for intubation and mortality rates; visual inspection of this plot indicated no evidence of publication bias for intubation rate, but we did observe a possible bias for mortality rate (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

The quality evaluation results of the three RCTs: (a) risk of bias graph and (b) risk of bias summary.

Table 2.

The NOS quality of included studies.

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total | Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REC | SNEC | AE | DO | SC | AF | AO | FU | AFU | |||

| Alharthy et al. 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | High |

| Alkouh et al. 12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | Moderate |

| Costa et al. 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | High |

| COVID-ICU group 13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| Duan et al. 14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| Fernández et al. 15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | Moderate |

| Franco et al. 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | High |

| Gaulton et al. 17 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 | Moderate |

| Ghani et al. 18 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | High |

| Gough et al. 19 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | Moderate |

| Mahroof et al. 21 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | Moderate |

| Menga et al. 22 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | Moderate |

| Nadeem et al. 23 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | Moderate |

| Pearson et al. 25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 | Moderate |

| Ranieri et al. 27 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| Rodrigues Santos et al. 28 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | High |

| Shoukri 29 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 | Moderate |

| Sykes et al. 30 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | High |

| Wendel Garcia et al. 31 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 | Moderate |

| Wendel Garcia et al. 32 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | High |

AE, ascertainment of exposure; AF, study controls for any additional factors; AFU, adequacy of follow-up of cohorts (⩾90%); AO, assessment of outcome; DO, demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study; FU, follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur; REC, representativeness of the exposed cohort; SC, study controls for age, sex; SNEC, selection of the non-exposed cohort.

‘1’ means that the study is satisfied with the item and ‘0’ means the opposite situation.

Figure 3.

Funnel plots of the (a) proportion versus the standard error of mortality, (b) intubation. Circles indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.

Clinical outcomes

A total of 5354 patients participated in the 23 studies9,11–32 of the present meta-analysis, all of whom were adult COVID-19 patients. The patients were admitted to different hospital settings and received noninvasive respiratory support at the time of admission. In 4 studies,11,17,20,25 a helmet was applied, in 11 studies,9,13–15,18,19,26,28,29,30,32 a face mask was used, 1 study 22 reported applying both a helmet and a face mask, 7 studies12,16,21,23,24,27,31 did not report whether a helmet or a facemask was used, in 6 studies,9,20,22,24,27,29 BiPAP was applied, 7 studies11,17–19,25,26,30 featured CPAP, 4 studies14–16,23 reported applying both BiPAP and CPAP, and 6 studies12,13,21,28,31,32 did not report whether they applied BiPAP or CPAP (Table 1).

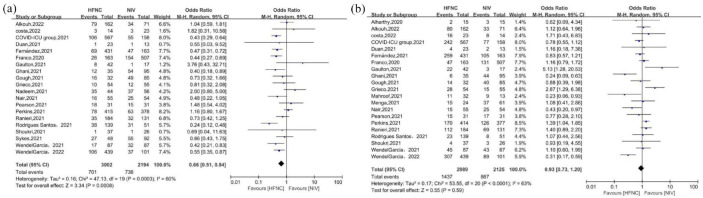

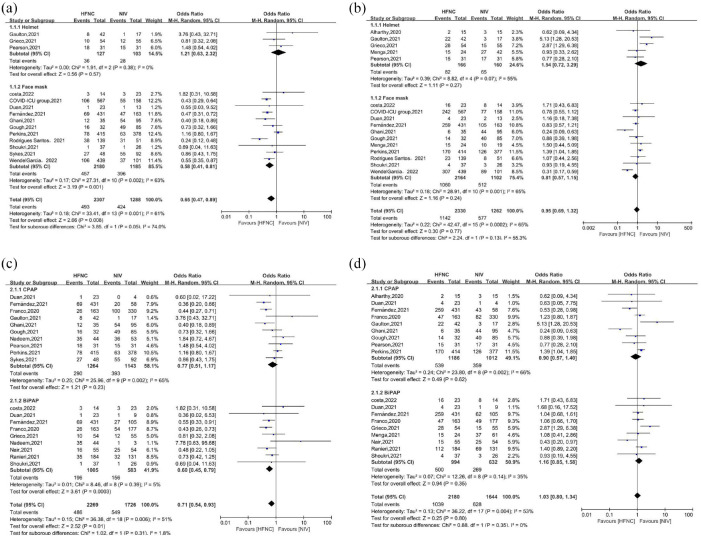

A total of 5196 patients participated in 20 studies9,12–20,23–32 that reported mortality, and the pooled estimates demonstrated that mortality rate was lower in HFNC groups than in NIV groups [OR = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.51–0.84, p = 0.0008, I2 = 60%, Figure 4(a)]. However, in subgroup analysis, no significant differences in mortality were observed in the HFNC group relative to NIV-helmet group [OR = 1.21, 95% CI: 0.63–2.32, p = 0.57, I2 = 0%, Figure 5(a)] or the NIV-CPAP group [OR = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.51–1.17, p = 0.23, I2 = 65%, Figure 5(b)], but significant differences in mortality were observed in the HFNC group relative to the NIV-facemask group [OR = 0.58, 95% CI: 0.41–0.81, p = 0.001, I2 = 63%, Figure 5(a)] or the NIV-BiPAP group [OR = 0.60, 95% CI: 0.45–0.79, p = 0.0003, I2 = 5%, Figure 5(b)].

Figure 4.

Mortality (a) and intubation (b) for included studies.

HFNC, high-flow nasal cannula; NIV, noninvasive ventilation.

Figure 5.

(a, b) Subgroup analysis of mortality and (c, d) intubation.

BiPAP, bi-level positive airway pressure; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; HFNC, high-flow nasal cannula; NIV, noninvasive ventilation.

Intubation was reported in 5114 patients in 21 studies9,11–22,24–29,31,32 and pooled estimates demonstrated that there were no significant differences in the intubation rate between the HFNC and NIV groups [OR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.73–1.20, p = 0.59, I2 = 63%, Figure 4(b)]. No significant differences in intubation requirements were found in subgroup analyses by interface [helmet: OR = 1.54, 95% CI: 0.72–3.29, p = 0.27, I2 = 55%; facemask: OR = 0.81, 95% CI: 0.57–1.15, p = 0.24, I2 = 65%, Figure 5(c)] or mode [CPAP: OR = 0.90, 95% CI: 0.57–1.40, p = 0.62, I2 = 66%; BiPAP: OR = 1.16, 95% CI: 0.85–1.58, p = 0.35, I2 = 35%, Figure 5(d)] relative to the HFNC group.

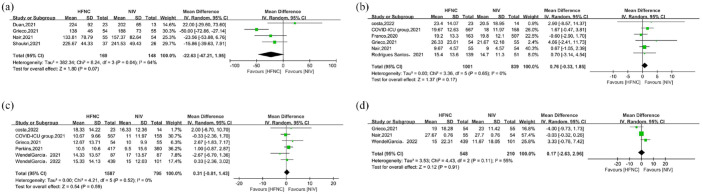

PaO2/FiO2 ratio (24 h after treatment) was reported in 317 patients in four studies,14,20,24,29 and no significant differences were found between the HFNC group and NIV group [MD = −22.63, 95% CI: −47.21 to 1.95, p = 0.07, I2 = 64%, Figure 6(a)]. A total of 2382 patients from six studies9,13,20,26,31,32 reported ICU LOS, and no significant differences were found between those two groups [MD = 0.31, 95% CI: −0.81 to 1.43, p = 0.59, I2 = 0%, Figure 6(b)]. The results were similar for hospital LOS: no difference in this value was reported in a total of 1840 patients in six studies9,13,16,20,24,28 between those two groups [MD = 0.76, 95% CI: −0.33 to 1.85, p = 0.17, I2 = 0%, Figure 6(c)]. A total of 758 patients in three studies20,24,32 reported VFD, and again there were no significant differences between those two groups [MD = 0.17, 95% CI: −2.63 to 2.96, p = 0.91, I2 = 55%, Figure 6(d)].

Figure 6.

The secondary outcomes for included studies: (a) PaO2/FiO2, (b) ICU length of stay, (c) hospital length of stay, and (d) days free from invasive mechanical ventilation.

HFNC, high-flow nasal cannula; NIV, noninvasive ventilation.

Discussion

In this meta-analysis of 23 studies with 5354 patients who were hospitalized for COVID-19, NIV was associated with higher mortality than HFNC. However, no significant differences in mortality were observed between the NIV-helmet group and the NIV-CPAP group compared with HFNC group. There were also no significant differences in the intubation rate, PaO2/FiO2, ICU LOS, hospital LOS, and VFD between the HFNC and NIV groups.

Noninvasive respiratory support, including the use of HFNC and NIV, has increasingly been used in the management of COVID-19-associated acute respiratory failure.5,6 A literature review found that HFNC can reduce the need for intubation in patients with COVID-19 and can decrease the LOS in the ICU as well as complications related to mechanical ventilation. 33 A population-based study involving 1400 patients found a similar 60-day mortality risk for patients undergoing immediate invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) and those intubated after an NIV trial, 34 suggesting that NIV can be safely used in patients with COVID-19 AHRF. However, questions remain about the utility, safety, and outcome benefit of noninvasive respiratory strategies, as there was little high-quality evidence. In patients who do not have COVID-19, the European Respiratory Society recommends HFNC therapy to patients with hypoxic respiratory failure over conventional nasal cannula therapy and NIV. 35 Since then, many studies have compared HFNC and NIV and have produced conflicting findings in patients with COVID-1913,18,20 for these patients, there is not enough evidence to prove which approach is better.

In our meta-analysis, we found that there were no differences in intubation rate, PaO2/FiO2, ICU LOS, hospital LOS, or VFD between the NIV and HFNC group, but mortality was significantly higher among COVID-19 patients in the NIV group, consistent with three recent meta-analyses.36–38 Whether this was because of the delayed intubation and increased mortality in the NIV group is still unclear. In general, the role of NIV is indeed controversial. The success of NIV, however, depends on several factors, such as, for example, the underlying causes of AHRF, patient cooperation, staff experience, interface, mode, and so forth. 8 Our meta-analysis included more studies than recent meta-analyses; more importantly, we performed subgroup analyses to evaluate the factors affecting the efficiency of NIV.

NIV ventilates by applying positive pressure to the lungs through a mask or a helmet. In the pre-COVID-19 era, a meta-analysis demonstrated that helmet NIV may reduce mortality and the need for intubation relative to conventional oxygen therapy in patients with purely AHRF. 39 Nonetheless, all included trials and observational studies were small, and helmet NIV was not compared with HFNC. In one other recent meta-analysis of adult patients with AHRF of all types, it was found that relative to facemask NIV, helmet NIV may reduce mortality and intubation; however, the effects of helmet NIV compared with HFNC remain uncertain. 40 The use of helmet NIV has steadily increased throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, 10 Our meta-analysis found that there were no differences in mortality rate between helmet NIV and HFNC, while face mask NIV had a higher mortality than HFNC. Previous study found that helmet NIV may be more comfortable and allow the application of a more ‘protective’ ventilation with higher PEEP (i.e. 8–12 cmH2O) and lower pressure support values with fewer air leaks and interruptions.39,41 However, only two small sample size RCTs20,26 and one observational study 17 comparing helmet NIV and HFNC were included in the analysis, and there was no study to comparing the differences of mode and ventilator parameters between helmet NIV and face mask NIV. High-quality RCTs in COVID-19 patients comparing helmet NIV with both face mask NIV and HFNC are needed, including patient-important outcomes and attention to possible adverse events.

NIV can deliver airflow through the CPAP and BiPAP modes. Largely because of an early negative report, 42 CPAP remains largely undocumented in ARDS. Recently, one multicenter adaptive RCT compared the use of CPAP, HFNC, and standard oxygen therapy. The results showed that treating hospitalized COVID-19 patients who had AHRF with continuous CPAP reduced the need for IMV. 26 Our meta-analysis found that there were no differences in mortality between CPAP and HFNC, while BiPAP had a higher mortality than HFNC. This may be for two reasons. On the one hand, patients’ conditions may have been relatively mild in the CPAP group; for these patients, medical personnel often choose the CPAP mode first as the majority of patients with COVID-19 who are offered continuous CPAP therapy (83–97%) can tolerate the treatment.43,44 On the other hand, the risks of BiPAP include delayed intubation, large tidal volumes, and injurious transpulmonary pressures; 6 many guidelines describe BiPAP as the first-line treatment for AHRF caused by acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema. 45 RCTs with large samples to compare CPAP with BiPAP or HFNC based on patient populations in COVID-19 patients are still lacking.

Therefore, routinely offering HFNC as the main form of noninvasive respiratory support for patients with respiratory failure due to COVID-19 may not be recommendable. 46 We need to fully consider the underlying cause of AHRF, the severity and cooperation of patients, and the advantages of each noninvasive oxygen strategy. For patients with COVID-19-associated AHRF, the way forward may be a stepwise treatment approach that is based on patient status/commodities, includes several consecutive ventilation strategies, 47 uses multiple oxygen strategies based on patients’ lifestyle and oxygenation status, and uses objective criteria when observing patients.

The present study had several limitations. First, our results were based mostly on cohort and case-control studies, and the quality of the evidence in these studies was low. The lack of RCTs may have reduced overall accuracy and increased heterogeneity. Some variables are likely skewed and would best be reported as medians with interquartile ranges and compared using a non-parametric statistical test, but this may be related to the original data provided by the included study. Second, few studies have been conducted on the use of a helmet in COVID-19 patients, and high-quality RCTs comparing helmet NIV to both face mask NIV and HFNC are needed. Third, population-based studies of evaluation of CPAP and BiPAP are lacking, such as BiPAP for COVID-19-associated AHRF patients with COPD and cardiogenic pulmonary edema, or CPAP for COVID-19 patients with purely AHRF. For this reason, we could not conduct subgroup analysis based on the patient population.

Conclusion

In this meta-analysis, we found although mortality was lower with HFNC than NIV, there was no difference in mortality between HFNC and NIV on a subgroup of helmet or CPAP group. The lack of RCTs may have reduced overall accuracy and increased heterogeneity. Future large sample RCTs are necessary to prove our findings.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Wei Tan  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1149-4168

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1149-4168

Contributor Information

Yun Peng, Department of Intensive Care Medicine, The Second Hospital of Jiaxing, Jiaxing, China.

Bing Dai, Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China.

Hong-wen Zhao, Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China.

Wei Wang, Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China.

Jian Kang, Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China.

Hai-jia Hou, Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China.

Wei Tan, Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, No. 155, Nanjing North Street, Heping District, Shenyang 110001, China.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Not applicable.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Yun Peng: Formal analysis; Methodology; Resources; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Bing Dai: Formal analysis; Resources; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Hong-wen Zhao: Formal analysis; Resources; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Wei Wang: Formal analysis; Resources; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Jian Kang: Formal analysis; Resources; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Hai-jia Hou: Formal analysis; Resources; Supervision; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Wei Tan: Formal analysis; Methodology; Resources; Supervision; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This meta-analysis was funded by the Science and Technology Planning Project, Shenyang (21-172-9-12).

Competing interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Availability of data and materials: Not applicable.

References

- 1. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA 2020; 323: 1239–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hendrickson KW, Peltan ID, Brown SM. The epidemiology of acute respiratory distress syndrome before and after coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Clin 2021; 37: 703–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wick KD, McAuley DF, Levitt JE, et al. Promises and challenges of personalized medicine to guide ARDS therapy. Crit Care 2021; 25: 404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Attaway AH, Scheraga RG, Bhimraj A, et al. Severe covid-19 pneumonia: pathogenesis and clinical management. BMJ 2021; 372: n436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Akoumianaki E, Ischaki E, Karagiannis K, et al. The role of noninvasive respiratory management in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. J Pers Med 2021; 11: 884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ogawa K, Asano K, Ikeda J, et al. Non-invasive oxygenation strategies for respiratory failure with COVID-19: a concise narrative review of literature in pre and mid-COVID-19 era. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 2021; 40: 100897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Spoletini G, Alotaibi M, Blasi F, et al. Heated humidified high-flow nasal oxygen in adults: mechanisms of action and clinical implications. Chest 2015; 148: 253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nava S, Hill N. Non-invasive ventilation in acute respiratory failure. Lancet 2009; 374: 250–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Costa WNDS, Miguel JP, Prado FDS, et al. Noninvasive ventilation and high-flow nasal cannula in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure by covid-19: a retrospective study of the feasibility, safety and outcomes. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2022; 298: 103842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372: n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alharthy A, Faqihi F, Noor A, et al. Helmet continuous positive airway pressure in the treatment of COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory failure could be an effective strategy: a feasibility study. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2020; 10: 201–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alkouh R, El Rhalete A, Manal M, et al. High-flow nasal oxygen therapy decrease the risk of mortality and the use of invasive mechanical ventilation in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia? A retrospective and comparative study of 265 cases. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2022; 74: 103230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. COVID-ICU Group for the REVA Network COVID-ICU Investigators. Benefits and risks of noninvasive oxygenation strategy in COVID-19: a multicenter, prospective cohort study (COVID-ICU) in 137 hospitals. Crit Care 2021; 25: 421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Duan J, Chen B, Liu X, et al. Use of high-flow nasal cannula and noninvasive ventilation in patients with COVID-19: a multicenter observational study. Am J Emerg Med 2021; 46: 276–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fernández R, González de Molina FJ, Batlle M, et al. Non-invasive ventilatory support in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia: a Spanish multicenter registry. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed) 2021; 45: 315–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Franco C, Facciolongo N, Tonelli R, et al. Feasibility and clinical impact of out-of-ICU noninvasive respiratory support in patients with COVID-19-related pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 2002130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gaulton TG, Bellani G, Foti G, et al. Early clinical experience in using helmet continuous positive airway pressure and high-flow nasal cannula in overweight and obese patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure from coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Explor 2020; 2: e0216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ghani H, Shaw M, Pyae P, et al. Evaluation of the ROX index in SARS-CoV-2 acute respiratory failure treated with both high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) and continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). MedRxiv. Epub ahead of print 24 March 2021. DOI: 10.1101/2021.03.23.21254203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gough C, Casey M, McCartan TA, et al. Effects of non-invasive respiratory support on gas exchange and outcomes in COVID-19 outside the ICU. Respir Med 2021; 185: 106481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grieco DL, Menga LS, Cesarano M, et al. Effect of helmet noninvasive ventilation vs high-flow nasal oxygen on days free of respiratory support in patients with COVID-19 and moderate to severe hypoxemic respiratory failure: the HENIVOT randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021; 325: 1731–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mahroof O, Jefrey M, Martin J, et al. Non-invasive respiratory support in COVID-19 is associated with a high risk of failure but no increase in mortality or complications of ventilation. Intens Care Med Exp 2021; 9(Suppl. 1): 51. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Menga LS, Cese LD, Bongiovanni F, et al. High failure rate of noninvasive oxygenation strategies in critically ill subjects with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure due to COVID-19. Respir Care 2021; 66: 705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nadeem I, Jordon L, Rasool MU, et al. Role of advanced respiratory support in acute respiratory failure in clinically frail patients with COVID-19. Future Microbiol 2022; 17: 89–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nair PR, Haritha D, Behera S, et al. Comparison of high-flow nasal cannula and noninvasive ventilation in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure due to severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Respir Care 2021; 66: 1824–1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pearson SD, Stutz MR, Lecompte-Osorio P, et al. Helmet noninvasive ventilation versus high flow nasal cannula for COVID-19 related acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2021; 203: A2599. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Perkins GD, Ji C, Connolly BA, et al. Effect of noninvasive respiratory strategies on intubation or mortality among patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure and COVID-19: the RECOVERY-RS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2022; 327: 546–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ranieri VM, Tonetti T, Navalesi P, et al. High-flow nasal oxygen for severe hypoxemia: oxygenation response and outcome in patients with COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022; 205: 431–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rodrigues Santos L, Gonçalves Lopes R, Rocha AS, et al. Outcomes of COVID-19 patients treated with noninvasive respiratory support outside-ICU setting: a Portuguese reality. Pulmonology 2022; 28: 59–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shoukri AM. High flow nasal cannula oxygen and non-invasive mechanical ventilation in management of COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory failure: a retrospective observational study. Egypt J Bronchol 2021; 15: 17. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sykes DL, Crooks MG, Thu Thu K, et al. Outcomes and characteristics of COVID-19 patients treated with continuous positive airway pressure/high-flow nasal oxygen outside the intensive care setting. ERJ Open Res 2021; 7: 00318-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wendel Garcia PD, Aguirre- Bermeo H, Buehler PK, et al. Implications of early respiratory support strategies on disease progression in critical COVID-19: a matched subanalysis of the prospective RISC-19-ICU cohort. Crit Care 2021; 25: 175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wendel Garcia PD, Mas A, González-Isern C, et al. Non-invasive oxygenation support in acutely hypoxemic COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU: a multicenter observational retrospective study. Crit Care 2022; 26: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gürün Kaya A, Öz M, Erol S, et al. High flow nasal cannula in COVID-19: a literature review. Tuberk Toraks 2020; 68: 168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Potalivo A, Montomoli J, Facondini F, et al. Sixty-day mortality among 520 Italian hospitalized COVID-19 patients according to the adopted ventilatory strategy in the context of an integrated multidisciplinary clinical organization: a population-based cohort study. Clin Epidemiol 2020; 12: 1421–1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oczkowski S, Ergan B, Bos L, et al. ERS clinical practice guidelines: high-flow nasal cannula in acute respiratory failure. Eur Respir J 2022; 59: 2101574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Glenardi G, Chriestya F, Oetoro BJ, et al. Comparison of high-flow nasal oxygen therapy and noninvasive ventilation in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acute Crit Care 2022; 37: 71–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. He Y, Liu N, Zhuang X, et al. High-flow nasal cannula versus noninvasive ventilation in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2022; 16: 17534666221087847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Beran A, Srour O, Malhas SE, et al. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen versus non-invasive ventilation in subjects with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Respir Care. Epub ahead of print 22 March 2022. DOI: 10.4187/respcare.09987. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ferreyro BL, Angriman F, Munshi L, et al. Association of noninvasive oxygenation strategies with all-cause mortality in adults with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2020; 324: 57–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chaudhuri D, Jinah R, Burns KEA, et al. Helmet noninvasive ventilation compared to facemask noninvasive ventilation and high-flow nasal cannula in acute respiratory failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2022; 59: 2101269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Patel BK, Kress JP. The changing landscape of noninvasive ventilation in the intensive care unit. JAMA 2015; 314: 16971699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Delclaux C, L’Her E, Alberti C, et al. Treatment of acute hypoxemic nonhypercapnic respiratory insufficiency with continuous positive airway pressure delivered by a face mask: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2000; 28: 2352–2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kofod LM, Nielsen Jeschke K, Kristensen MT, et al. COVID-19 and acute respiratory failure treated with CPAP. Eur Clin Respir J 2021; 8: 1910191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Aliberti S, Radovanovic D, Billi F, et al. Helmet CPAP treatment in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia: a multicentre cohort study. Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 2001935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rochwerg B, Brochard L, Elliott MW, et al. Official ERS/ATS clinical practice guidelines: noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: 1602426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. The National Institute for Health Care Excellence. COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing COVID-19, https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng191/resources/covid19-rapid-guideline-managing-covid19-pdf-51035553326 (2021, accessed 12 February 2021). [PubMed]

- 47. Bonnesen B, Jensen JS, Jeschke KN, et al. Management of COVID-19-associated acute respiratory failure with alternatives to invasive mechanical ventilation: high-flow oxygen, continuous positive airway pressure, and noninvasive ventilation. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021; 11: 2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]