Abstract

Background

Many technological interventions designed to promote physical activity (PA) have limited efficacy and appear to lack important factors that could increase engagement. This may be due to a discrepancy between research conducted in this space, and software designers’ and developers’ use of this research to inform new digital applications.

Objectives

This study aimed to identify (1) what are the variables that act as barriers and facilitators to PA and (2) which PA variables are currently considered in the design of technologies promoting PA including psychological, physical, and personal/contextual ones which are critical in promoting PA. We emphasize psychological variables in this work because of their sparse and often simplistic integration in digital applications for PA.

Methods

We conducted two systematized reviews on PA variables, using PsycInfo and Association for Computing Machinery Digital Libraries for objectives 1 and 2.

Results

We identified 38 PA variables (mostly psychological ones) including barriers/facilitators in the literature. 17 of those variables were considered when developing digital applications for PA. Only few studies evaluate PA levels in relation to these variables. The same barriers are reported for all weight groups, though some barriers are stronger in people with obesity.

Conclusions

We identify PA variables and illustrate the lack of consideration of these in the design of PA technologies. Digital applications to promote PA may have limited efficacy if they do not address variables acting as facilitators or barriers to participation in PA, and that are important to people representing a range of body weight characteristics.

Keywords: Physical activity, exercise, psychology, barriers, facilitators, obesity, body weight, self-care technologies, behavior change

Introduction

Physical inactivity is a serious problem: it is one of the main causes of death worldwide, causing 3.2 million deaths each year. 1 Globally, 23% of adults are not considered sufficiently active, and across Europe, one-third of the adult population is considered physically inactive.2–4 Physical inactivity in adults is a risk factor for obesity and many chronic diseases, including many cardiovascular and age-related diseases, diabetes, chronic pain, and some types of cancer; it increases the risk of depression and contributes to other negative health and psychosocial outcomes.5–10 In turn, regular physical activity (PA)—150 minutes or more of moderate PA per week for adults—can reduce the prevalence of these conditions. 11

Technology often contributes to physical inactivity 12 but it also offers many cheap and widely accessible possibilities for increasing PA. 13 Many technological interventions such as mobile apps, web interventions, activity trackers and visualizations of PA, social media, or videos14–18 are being designed to promote PA. While computer-based interventions were initially the primary approach to promote PA through technology,14,19,20 nowadays the main focus is on developing interventions using mobile devices.21,22 Moreover, wearable devices currently hold the first position in worldwide fitness trends 23 and are thus particularly relevant for PA interventions. However, merely focusing on rapid technology-driven development, without evaluating the impact of interventions can lead to important aspects being ignored. In fact, the effectiveness of technological interventions on PA has often been considered questionable or limited, as the reported PA increases are often small and transitory.24–26

In the last decade, the Human-Computer Interaction research community, and more recently the commercial sector, have attempted to build on cognitive behavioral theories to design technologies to address the problem of physical inactivity. While a number of theories have been considered for explaining PA behavior, a systematic review of persuasive health technologies 27 reported that 55% of these technologies were not founded on any theory or do not specify it. Further, while most technologies claim to be based on a theoretical framework, it was not reported how the theory was integrated within the technological intervention. This is despite the fact that the effectiveness of the technology seems to be related to the behavioral theory that it relies on. 28 Some studies have suggested that PA interventions should also report which components of the theoretical framework/theory are used to make the intervention effective or are mediating variables for PA. 25 Especially when the intervention is based on multiple theories, where there is a risk of excluding potentially important variables. 29

A recent review 30 has highlighted important limitations of the approaches used for behavior change and called for reconsidering these works through the lens of critical but unaddressed factors, such as self-insight. Our paper aims to respond to this call by considering unaddressed factors in PA interventions. Another review about PA interventions recommends exploring other possible variables by using both inductive and deductive methods in addition to existing theories. 25 To that end, some studies have focused on gaining insight from looking at relevant aspects of the specific PA behavior by using an atheoretical approach. By atheoretical approach, we mean an approach not based on current theoretical models, which would allow investigating all mediating variables in PA-related behavior and not only those variables considered in existing theories. Taking this approach is necessitated by the fact that the mediating variables obtained from current theoretical models do not account for substantial variability in the targeted outcomes. 25 In particular, different reviews and meta-analyses have reported only small to moderate effect sizes for theory-based interventions (e.g., in, 31 effect sizes were in the range of 0.12–0.15, and in, 32 were around 0.35). In this context, there is a debate on the appropriateness of using theory-based interventions for PA promotion.33–35 The main focus of studies using alternative, “atheoretical” approaches, has been to explore the barriers—obstacles found by people when trying to engage in PA- and facilitators-reasons found by people for doing PA—in specific populations.36–38 In addition, an atheoretical approach allows us to focus on recommendations on the importance of considering each component or potential variable affecting PA behavior and the fact that existent theories used in this context are not specifically designed for PA. In fact, some of the critical known affecting variables -barriers and facilitators- studied specifically for PA, are not taken into account in a number of studies.30,39–43

Our paper addresses the identified need to support a more informed design of technology for promoting PA in two ways. First, we revisit the Psychology literature, focusing on barriers and facilitators to PA, to create a summary of the PA influencing variables. We will search for all the non-demographic variables critical for PA reported in this literature for adults. We specifically allude to non-demographic variables because demographic variables are not easy to handle for intervention purposes directly, as highlighted by. 44 The variables reported will be sorted according to three major levels: psychological, physical, and personal/contextual, based on. 45 We are mainly interested in psychological variables, and in how these are used to build potential interventions promoting PA. While physical and personal/contextual variables are also critical to app design for PA, the problem is that the psychological variables are generally ignored or addressed in a simplistic and narrow way (e.g. badges). Second, we revisit the Computing literature to better understand which of the variables identified in (1) are addressed and what is left out according to the well-established Psychology literature.

In this paper, we also consider body weight as a factor that is often implicated in physical inactivity. 46 The articles included in the literature review consider populations from all weight groups, that is, healthy weight, obese and overweight groups, 47 to be able to compare the variables across these groups. The promotion of PA seems to be of particular importance in the obese population to prevent health deterioration. 48 A deficient PA level, along with sedentary time, are among the fundamental causes of obesity in adults.5,7,10,48–50 People with obesity may experience/perceive more PA barriers than non-obese or the healthy-weight populations as shown in some studies with adolescents 51 and women. 52 It therefore seems crucial to assess the impact of body weight when designing effective interventions for PA that consider specific barriers faced by the person. 53

The aim of this study was twofold. First, to review and to inform about the potential mediating non-demographic variables of PA. Second, to understand whether these potential variables are taken into account when developing technologies for PA. Two systematized reviews54,55 were conducted: one from the psychology field and one from the computing field. We conducted a systematized review as it is rigorous and encompasses several, but not all aspects of a full systematic review. 56 Like systematic reviews, the article search and selection, data extraction, and results synthesis for systematized reviews are determined a priori, fully documented, and systematic. However, a systematized review is often distinguished from a systematic review in that the former may not include a formal assessment of study quality, remove or weight study findings based on methodological quality, nor pool results to undertake meta-analysis.54–56 In addition, systematized literature reviews allow synthesizing qualitative evidence54–56 and provide the flexibility needed to consolidate the information about PA variables; since each article uses a different narrative to represent the same variable, for our study, this process entailed unifying the way in which the variables are expressed.

For the first review, we focus on the psychology field because our main focus is on psychological variables and they are more reported than contextual/personal or physical variables.57–59 While contextual variables related to PA exist, there is evidence that these explain less PA behavior than the internal or psychological variables to PA faced by individuals.60–66 Equally, we acknowledge physical variables to PA, especially among elderly people. 67 However, despite a statistical relationship with physical inactivity, there is less focus on reporting physical variables compared with psychological or contextual/personal ones by large epidemiological population-based studies.68–71

Nevertheless, psychological variables are mostly overlooked in the design of technology, which generally focuses on addressing motivation rather than carrying out an in-depth analysis of the psychological barriers (beyond motivation) to undertaking PA (see for instance 72 ).

A recent review, 73 provides evidence of barriers to PA specific to obesity in the literature. The study refers to the importance of knowing whether being obese means people confront barriers that are additional to those faced by the non-obese population; however, the articles referred to in the study exclusively focus on obese individuals. Our aim is to build on this study and explore whether the barriers are the same in the non-obese and obese populations more broadly, and we believe that such a comparison can only be made if articles in the review include healthy-weight, overweight, and obese populations.

This paper is structured as follows: first, we present two systematized reviews, one from the psychology field and another one from the computing field. We then discuss the results from both reviews and propose a rethink of PA technologies by considering psychological factors in the design process.

The contributions of this paper are an account of PA variables across populations differing in PA-level and body weight and an illustration of the lack of consideration of these in the design of PA technologies. In the Computing field, a literature review addressing this issue has not been carried out yet, to our knowledge.

Methods

Recruitment

The Psychology literature search—henceforth called Review 1—was conducted in June 2017. The Computing literature search—henceforth called Review 2—was conducted in July 2017 (for information on search dates and other details of the search strategy see “Search Strategy” section below).

Databases

The database used for Review 1 was PsycInfo, which includes scientific articles from the psychology and psychiatry fields provided by the American Psychological Association. This database is considered the most exhaustive database in its field globally. 74 Note that PsycInfo was selected because our main focus is on psychological variables, as explained above. It should further be noted that PsycInfo includes various medical journals and thus it also provides an understanding of that field.

For Review 2, we used the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) digital library database, which contains the collection of all ACM publications. 75 ACM is considered the world's largest educational and scientific computing society. 76

Search strategy

For both systematized reviews, the detailed search strategy implementation was as follows: [("physical activity" OR "physically active" OR "physical inactivity" OR "physically inactive" OR "physical activities" OR "motor activity" OR "sedentary"]) had to appear on the title or abstract; (["Needs" OR "barriers" OR "facilitators")] in the article. In addition, for Review 1, the term “obesity” had to appear in the article. Note that for Review 2 the general terms “needs,” “barriers,” and “facilitators” were kept instead of searching for specific barriers to ensure barriers were not missed, as each article uses a different name or narrative to represent the same variable. Review 1 was restricted to peer-reviewed articles written in English and published from 2007 to 2017, on studies conducted with adult human participants (18 years and older). Review 2 was restricted to conference proceedings and journal articles, published from 2007 to 2017. The reason for including gray literature, 77 and in particular conference proceedings, is because conference proceedings are one of the main means of publications in the field of computer science, differently from the psychology field. These differences in the restrictions are due to the search possibilities of the database.

Selection criteria

The resultant papers from each database search were revised to include only the relevant ones using the following exclusion criteria: PA not being relevant in the article; population under 18 years old; population with cognitive impairment; duplicate articles; systematic reviews, protocols, clinical cases, editors’ letters, summary papers; articles not mentioning barriers or facilitators for PA; non-human subjects. While the term “obesity” had to appear in the article (see Search strategy), articles with any weight population were included according to our aim to understand whether the barriers are the same in the non-obese and obese populations.

Selection process

An Excel table including the publication name, authors, year, and journal of publication was created. The article screening consisted of three steps. At every step, articles meeting any of the exclusion criteria were excluded, and the unclear ones were treated as included articles until the next or final step. Three steps were: (1) we read titles and abstracts of all articles obtained through the search. Articles meeting any exclusion criteria were excluded. (2) We did a quick skim reading of the full text of the remaining articles, searching for relevant aspects mentioned in the search strategy. (3) The remaining articles were read completely and extensively. The relevant information regarding the population aspects, the methodology characteristics, and the aspects affecting PA from each article, was organized and placed in the table. Articles meeting any exclusion criteria were excluded from the final batch.

Data treatment

The articles identified through the systematized reviews were used to obtain information about the PA-reported variables (i.e. barriers and facilitators of PA). We worked to unify the way in which the variables are expressed, since each article uses a different narrative to represent the same variable. We organized the constructs, descriptions, sentences, or any type of quote used in the articles for expressing a variable in groups according to their similarity and gave a standardized name to each variable. Variables and quotes were organized based on (a) the similarity of the quotes, (b) the similarity of the concepts or definitions underlying the quotes, and (c) whether the different quotes have been commonly presented together under the same concept or categorized as the same aspect. The classification of variables was conducted by one reviewer (first author of the paper) and revised by four other co-authors of this paper, all of them with experience in PA-related research.

Our intention is to classify the variables for standardized use when developing interventions. This would enable us to consider all the variables important for an intervention approach and to dismiss any irrelevant ones. The importance of an adequate classification system enabling a clear picture and selection of relevant aspects when choosing an intervention approach has been highlighted by Michie, 29 who developed a classification system for general behavior change techniques based on a review of the existing interventions. We follow this approach but make a classification in a more inductive way, drawing from the variables reported in the literature and organizing them into major levels, which can be useful when choosing an intervention approach. The particular way of organizing our variables is based on a framework presented in, 45 which fits with the variables we found in our work. Thus, the major levels used here for organizing the variables are the following:

Psychological: emotional, cognitive, motivational, affective, and behavioral aspects.

Physical: aspects related to the body nature and constitution and physiological processes.

Personal/contextual: utilitarian personal resources or environmental aspects.

Results

Review 1: PA influencing variables

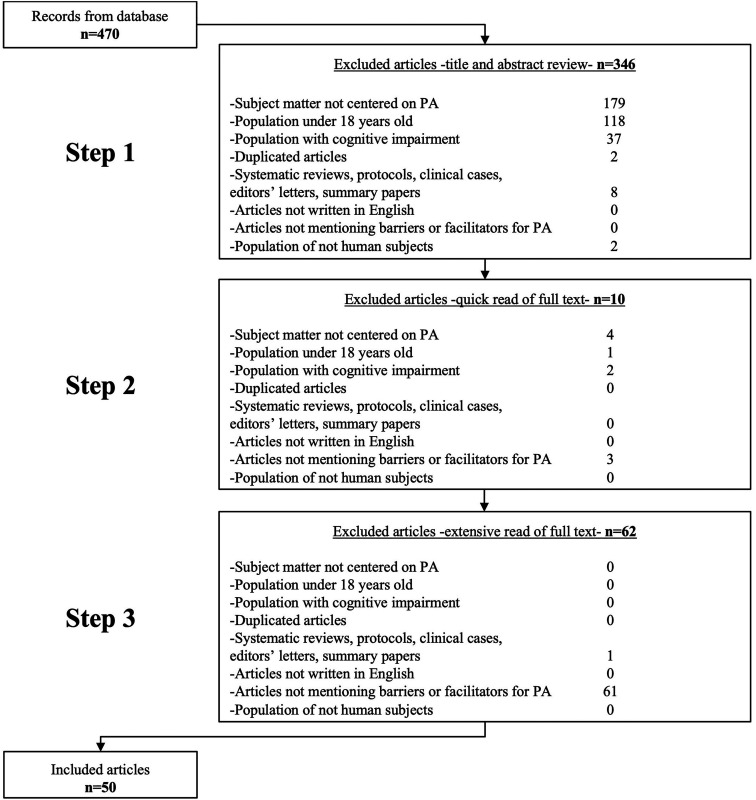

The literature search yielded 470 articles. A flow diagram illustrating the three-step selection process followed and the reasons for the exclusion of the articles in each step is included in Figure 1. Through the reading of the title and abstract, 346 articles were excluded, and 124 remained. Through the quick full-text reading, 12 other articles were excluded. Finally, from the remaining articles, 62 other articles were excluded. The final sample comprises 50 articles (for a complete list, see Supplementary File 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram illustrating article selection strategy in Review 1.

From the final 50 articles, we extracted the population aspects related to body weight categories, obese, overweight, and healthy normal-weight (hereafter referred to as healthy-weight) based on 47 . To classify the weight categories for each article, if most of the population from the article (near 80%) met one aspect (e.g. being overweight/obese), it was classified in that way. 16 (32%) of the articles were classified into the overweight/obese categories, 28 (56%) into the healthy-weight category and the remaining 6 (12%) belonged to both categories. In addition, we extracted information related to whether the PA potential variables were measured in a qualitative (21 articles) or quantitative way (25 articles) or included both types of measures (4 articles). These classifications respond to the procedures/population regarding only PA variables in each article.

Review 2: Attention given to PA influencing variables in the Computing literature

The literature review from the ACM database yielded 123 articles. As for Review 1, we followed a three-step selection process (see Figure 2 with a flow diagram illustrating this process and the reasons for the exclusion of the articles in each step). Through the reading of the title and abstract, 47 articles were excluded, leaving 76. Through the quick full-text reading, 33 other articles were excluded, leaving 43. Finally, from the remaining articles, 28 other articles were excluded. The final batch comprises 15 articles (for a complete list, see Supplementary File 2).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram illustrating article selection strategy in Review 2.

Evaluation Outcomes

As reported in the Methods section, the final batch of articles of Review 1 was used to identify the facilitators and barriers to PA. The aim of Review 2 was to evaluate if these variables were considered for technological interventions in the Computing literature. For Review 2, we report separately all the variables mentioned in the article, and the variables that were measured or evaluated (e.g., by means of questionnaires, as a theme topic in interviews or focus groups, with sensors or ad-hoc apps).

The criteria used to identify something as a barrier/facilitator was that the article explicitly mentioned that aspect as a barrier or facilitator for PA (e.g. “Lack of company acts as a barrier” or “company facilitates PA”), and in that sense, all variables were indeed associated in the articles to physical inactivity.

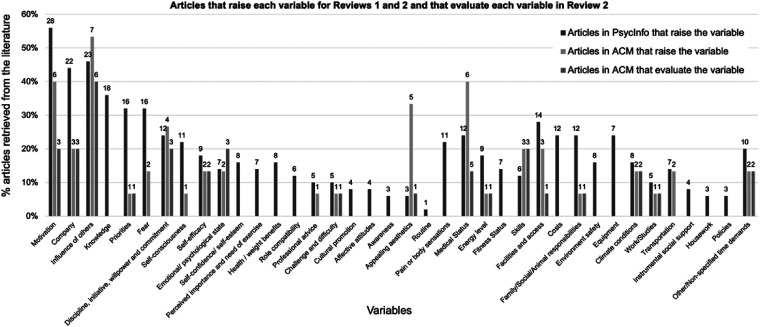

The variables are presented in Table 1, each classified according to one of the three main levels: psychological, physical, and personal/contextual levels, respectively. For each variable we present: (a) the general description, summarizing all mentions of a specific variable in relation to them acting as barrier or facilitator, without specifying specific populations to which these would apply, (b) a particular mention about the attention given to the relation to PA level in the article (e.g. people meeting PA guidelines vs not meeting them), (c) the specificities for the overweight/obese population, (d) the articles that raise the variable for both reviews, and the articles that evaluated the variables in the Review 2, and (e) a summary of the effects on PA of the factors included in the study design and evaluated in Review 2. Figure 3 summarizes the percentage of articles in Review 1 that raise each variable, and the percentage of articles in Review 2 that raise and evaluate the variable. Supplementary Files 3–5 include Tables that present the number of articles that report each psychological variable organized by different aspects of the population (body weight group, place of residence, and specific population conditions, e.g. medical condition).

Table 1.

Psychological, physical and personal/contextual variables of PA obtained from Review 1, articles that raise each variable in Reviews 1 and 2 and that evaluate each variable in Review 2.

| Variable | Description and papers that raise the factor in PsycInfo | Specificities for groups differing in PA level | Specificities for weight groups | ACM papers that raise and evaluate the factor | Effects on PA as evaluated in ACM articles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological | |||||

| Motivation |

References: 52,78–104 |

Motivation is more reported in women not meeting PA guidelines than in women meeting PA guidelines. 91 | Lack of motivation is more reported by overweight 92 and obese women.92,93 A lower percentage of obese vs. non-obese women enjoy PA 90 , 91 found no differences in enjoyment for different weight groups. | Raise:105–110 Evaluate:106,107,109 | Greater levels of intrinsic (vs. extrinsic) motives are associated with more persistent PA engagement 109 . E.g. enjoyable PA activities106,107,109. |

| Company |

References: 52,79–82,86–89,91,92,94–97,101,104,111–115 |

Company as a barrier was more likely to be reported by less active women. 91 | Raise:105,106,116 Evaluate:105,108,116 | Company of others during PA acts as facilitator105,108,116. | |

| Influence of others |

References: 79–81,83–85,87–89,91,96–99,112,113,117–123 |

Lack of close active examples are a barrier for people not meeting PA recommendations. 98 Higher social support is usually associated with people with higher rates of PA113,119, 120 found no association between lack of social support and declines in PA. | Influence is reported as a significantly higher barrier in the obese population than the non-obese. 91 PA in overweight/obese individuals is more affected by social influence than in healthy-weight individuals.99,121 Negative social influence can be higher for overweight/obese individuals, due to weight related teasing.79,87 | Raise:105,106,108, ,124–128 Evaluate:106,108,124,125,127,128 | Usually a facilitator of PA but can be a barrier in some cases. E.g. the effect of competitiveness can hamper or facilitate PA 124 . |

| Knowledge |

References: 52,80,84,85,87,88,90,91, 94,95,104,111,114,122, ,129–132 |

Lack of education from health professionals has been associated with lower levels of PA. 130 | Tailored health messages seem to be a facilitator for obese women. 131 | ||

| Priorities |

References: 78,79,81–83,87,89,93,99–101,104,129,135 |

Raise: 105 Evaluate: 105 | Lack of energy seen as a priority: young adults related it to lack of time, or as if the priority was to rest 105 . | ||

| Fear |

References: 78,82,84,88,91,94–96,102,113,115,119,121,123,132,135 |

Fear of injury more in low-than moderate-active participants. 96 In Ref. 121, fear predicted PA during the first pregnancy trimester. | Fear of injury has been reported in a higher level by obese groups than by non-obese groups. 91 | Raise:106,109 | |

| Discipline, initiative, willpower, and commitment |

References: 52,81,83,85,87,91,95, 96,117,119,121,123 |

More likely to be reported by women with low PA. 91 Feeling lazy predicts PA. 121 | More reported by overweight/obese women52,121; but 91 found no differences between weight groups | Raise:105,124,126,136 Evaluate:109,126,136 | Only specific goals with a high commitment level are good facilitators of PA109,136. Commitment can act as a barrier if announced publicly 126 . |

| Self-consciousness |

References: 52,79,80,83,84,87,88,93,96,102,135 |

Reluctance toward PA in front of others due to weight or being uncomfortable with appearance/perceived size are barriers.79,93 Self-consciousness during PA is significantly higher in obese participants. 52 | Raise: 110 | ||

| Self-efficacy |

References: 80,84,86,87,90,103,115,119,120 |

Correlates with PA level103,119,120. 115 found self- efficacy did not predict PA adherence in either sex. | Raise:109,136 Evaluate:109,136 | Associated with persistent engagement in PA, if done with intrinsic motives 109 | |

| Emotional/psychological state |

References: 80,84,89,95,99,114,137 |

Raise:105,138 Evaluate:105,106,109 | Mood affects PA levels105,106: depression/sadness decreases PA 106 ; stress is a barrier106,109 but also a motivator to alleviate it 105 . | ||

| Self-confidence/self-esteem |

References: 80,81,83,87,89,93,94,101 |

Some issues specific to being overweight. 87 Weight is related to being uncomfortable with looks during PA. 93 | |||

| Perceived importance and need of exercise |

References: 78,86,96,100,112,114,133 |

||||

| Health/weight benefits |

References: 79,80,84,87,89,93,112,113 |

Obese women were more likely to agree that they only exercise when trying to lose weight than non-obese women. 93 | |||

| Role compatibility |

References: 78,87,90,100,112,113 |

||||

| Professional advice |

References: 80,87–89,94 |

Raise: 108 | |||

| Challenge and difficulty |

References: 52,83,86,89,98 |

Reporting difficulty is significantly related to whether people meet PA recommendations. 98 | Raise: 136 Evaluate: 136 | Difficult goals are PA facilitators 136 . | |

| Cultural promotion |

References: 79,85,129,139 |

||||

| Affective attitudes |

References: 80,81,83,95 |

||||

| Awareness |

References: 88,99,122 |

||||

| Appealing aesthetics |

References: 85,98,117 |

Raise:105,107–110 Evaluate: 107 | Tracking both PA levels and contextual information supports reflection on their association 107 . | ||

| Routine |

References: 89 |

||||

| Physical | |||||

| Pain or body sensations |

References: 52,80,83,88,89,93,95,99,101,115,121 |

In 121 , soreness (not pain) correlated with PA. In Ref. 115, higher body pain predicted greater PA in women and less in men. | Physical discomfort is a weight-related barrier. 93 Pain is reported more by overweight/obese than healthy-weight women. 52 | ||

| Medical status |

References: 52,80,82,84,87,91,93–96,120,133 |

There is a negative correlation between physical problems and PA level. 95 | Poor health or minor aches and pains are reported as bigger barriers by overweight and obese women in Ref. 52. | Raise:105,106, ,108–110,124 Evaluate:105,106,109–124 | Medical conditions (e.g. lack of sight) or decline in physical/ health status are barriers106,108–110,124. Adoption/ maintenance of health doing PA are facilitators105,109. |

| Energy level |

References: 79,88,91,94–96,100,121,135 |

Energy level is correlated to the PA level.95,121 | Tiredness95,135 is a PA barrier related to weight. | Raise: 105 Evaluate: 105 | Lack of energy is a barrier 105 . |

| Fitness status |

References: 52,78,80,86,93,113,135 |

||||

| Skills |

References: 52,85,87,91,98,122 |

Lack of skills is a bigger barrier for those with low PA level. 98 | Raise:105,109,126 Evaluate:105,109,126 | Self-competition or prior PA level 105 , performance 126 and nimbleness (i.e. speed/accuracy in thoughts or movement) are facilitators 109 . | |

| Personal/ contextual | |||||

| Facilities and access |

References: 80,82,83,85–87,90,94,97–99,111,112,133 |

People meeting PA recommendations reported, in a greater level, having bicycle lanes around the house as a facilitator than those not meeting PA recommendations. 98 | The lack of access to facilities was especially discussed as a barrier by participants who had severe obesity. 80 | Raise:106,108,140 Evaluate: 106 | Lack of facilities (e.g. gyms or stores), uneven pathways, noise, pollution, traffic or relocation to smaller homes reported as barriers 106 . |

| Costs |

References: 78,79,83,85,87, 90,95,98,111,112,115,129 |

High cost of PA is a significantly bigger barrier for those not meeting PA recommendations. 98 | |||

| Family/Social/Animal responsibilities |

References: 52,78,80,87,89,94, 96,100,112,117,121,133 |

Having family responsibilities predicts PA in healthy-weight women. 121 | Raise: 106 Evaluate: 106 | Caregiving duties can be a barrier 106 . | |

| Environment safety |

References: 79,81,85,94,96,97,112,129 |

Neighbourhood safety is related to a person’s PA level. 81 | |||

| Equipment |

References: 80,85,87,89,91,96,101 |

Not finding appropriate clothing or equipment, discomfort in the clothes,80–87 are barriers for overweight/obese people. | |||

| Climate conditions |

References: 85,87,94,96,100,117,133,141 |

Poor-weather correlates with PA level. 96 | Raise:105,106 Evaluate:105,106 | Inclement weather (e.g. extreme cold) reported as a barrier105,106. | |

| Work/studies |

References: 78,80,100,121,135 |

Having to work is a bigger barrier for healthy- weight than for overweight/ obese women. 121 | Raise: 106 Evaluate: 106 | Work related time management is a barrier for elderly people 106 . | |

| Transportation |

References: 86,87,97,103,111,112,139 |

Raise:108,140 | |||

| Instrumental social support |

References: 87,100,112,132 |

||||

| Housework |

References: 87,112,133 |

||||

| Policies |

References: 85,87,111 |

||||

| Other/non-specified time demands |

References: 78,79,83,84,94,96,99,101,117,121 |

Having no time is a bigger barrier for healthy-weight women than other weight categories. 121 | Raise:105,106 Evaluate:105,106 | Lack of time 106 or poor time management skills 105 are a barrier. | |

Figure 3.

Percentage of articles that raise each variable in Reviews 1 and 2 and percentage of articles that evaluate the variable in Review 2. The numbers on top of the bars refer to the number of articles.

It should be noted that the column “Description” in Table 1 summarizes all mentions of specific variables as barriers or facilitators for PA. Then columns 3 and 4 include specific mentions of relation to PA levels and weight groups. Understanding the relationship of each variable with the PA level or with the weight group is important in order to consider their inclusion in the design of interventions aiming for behavior change. These aspects are presented in the different columns. The variables are presented by relevance, that is, in descending order, depending on the number of articles mentioning them.

To provide a more in-depth understanding of the focus of each study and its outcome,Table 2 summarizes the activities/interventions performed in the articles from Review 2 which evaluated psychological variables, as well as the populations under study, the measures employed, and the recommendations the authors made based on their findings.

Table 2.

Summary of studies in Review 2.

| First author/Ref. nr. | Psychol. variables evaluated | Population | Activities/ Interventions performed | Measures employed | Findings/design implications. Technology should: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capel 105 |

|

Young adults | No intervention. 2-week user study with an exercise diary to inform technology for PA. | Interview Questionnaire |

|

| Fan 106 |

|

Elderly | No intervention. Interview to evaluate concept storyboards to learn attitudes towards technology for PA interventions. | Interview |

|

| Li 107 |

|

Physically inactive | Two longitudinal studies with technology for monitoring/visualization of PA and context. 3 conditions compared: (1) control = no information; (2) information on PA only (step count); (3) information of PA and context. | Interview Questionnaire PA sensors Ad-hoc app | Better integrate collection of/reflection on data:

|

| Grosinger 108 |

|

Elderly | Think-aloud walkthrough with tablet-based prototype showing PA Information and friends’ PA activities and opportunities to join. 1-week study with technology probe and diary. | Interviews Questionnaire PA sensors Ad-hoc app | Promote PA by using social motivators to engage with close friends (e.g. promoting awareness of friends’ activities and opportunities to join in). |

| Lacroix 109 |

|

Physically inactive | No intervention. PA was tracked with a wearable device for 10 days. PA analyzed together with questionnaire data on psychological variables. | Questionnaire PA sensors |

|

| Chen 124 |

|

Healthy adults Diabetes Obese | 2-month mix-method study: 1-month individual session + 1-month session with social fitness app allowing exercise in dyads with social incentives: (1) cooperation within dyads, (2) competition with other teams. | Interview PA sensors Ad-hoc app |

|

| Li 125 |

|

General population | No intervention. Surveys and interviews to understand how people use personal informatics systems. | Questionnaire Interview |

|

| Munson 126 |

|

People who are obese | Randomized field study with device for announcing PA commitments on social media. 3 conditions: (1) weekly commitments kept private (control); (2) public announcement of commitments; (3) public announcement of commitments and results (PA from sensors). | Sensors Ad-hoc app |

|

| Turchani-nova 127 |

|

Mixed (healthy, overweight, obese) | 1.5-month observational field study with an app that tracks PA and allows to follow other users. | Ad-hoc app |

|

| Nakanishi 128 |

|

Runners | Field study with users with app to compete virtually with others running at different places and times. Users walked/ran under 3 conditions: (1) no competition; (2) one-to-one competition; (3) massive competition. | Ad-hoc app |

|

| Leng 116 |

|

General population (Chinese immigrants) | No intervention. Surveys and interviews to learn about barriers to care towards intervention to promote access to cancer diagnosis/treatment. | Interview Questionnaire |

|

| Saini 136 |

|

General population | 10-day field study using a PA sensor. Users received feedback on their daily PA level and how common daily activities (e.g. household activities) contributed to it. | Questionnaire PA sensors |

|

As it can be seen, only a few of the identified variables are taken into account in the development of technologies, according to Review 2. From 38 variables considered in the Psychology literature review, 21 are mentioned in the Computing literature review, and even less, 17, are actually considered in evaluations of the technology (see Table 1). In particular, the variables company; influence of others; initiative, willpower and commitment; emotional/psychological state; self-efficacy; medical status; skills; climate conditions; and other/non-specified time demands are taken into account and evaluated in articles about developing technologies. These articles report company of others during PA,105,108,116 self-efficacy 109 and skills (i.e. having a previous level of PA, 105 good performance, 126 and nimbleness 109 ) as facilitators to PA, while medical conditions or decline in physical/health status,106,108–110,124 inclement weather,105,106 and lack of time 106 or poor management skills 105 are reported as barriers. They also report that the influence of others is usually a facilitator of PA, but it could also be a barrier in some cases; for instance, the positive/negative effect of competitiveness in PA differs among people. 124 Similarly, specific goals with a high commitment level are usually good facilitators of PA109,136, but can act as a barrier if announced publicly. 126 For emotional/psychological state, the mood was found to affect the level of PA105,106: depression or sadness decreases PA 106 ; stress could be a barrier to PA106,109 but also a motivator to do PA to alleviate it. 105 Motivation is also mentioned in a number of studies, but evaluated in half of them; these studies found that greater levels of intrinsic (vs. extrinsic) motives, such as enjoyment of the PA,106,107,109 are associated with a more persistent engagement in PA. 109 Appealing aesthetics and facilities and access are mentioned in some articles but just evaluated in one article, in which it was found that lack of facilities (e.g. gyms or stores), uneven pathways, noise, pollution, traffic or relocation to smaller homes act as barriers, 106 and that tracking PA and contextual information together supported users’ reflection on the association between the environment and the PA level. 107 Priorities; challenges and difficulty; energy level; family/social/animal responsibilities; and work/studies are mentioned and evaluated in one article. These articles report difficult goals 136 as a facilitator to PA, while lack of energy, 105 caregiving duties, 106 and time management mistakes related to work 106 are mentioned as barriers for PA. Self-consciousness and transportation are barely mentioned and never evaluated. Fear is mentioned in two articles but also never evaluated. Finally, cultural promotion; role compatibility; health/weight benefits; routine; self-confidence/self-esteem; affective attitudes; knowledge; perceived importance and need of exercise; awareness; fitness status; pain or body sensations; environmental safety; policies; costs; equipment; instrumental social support; and housework are not mentioned, nor evaluated in the technological literature.

In addition to articles in Review 2, one Review 1 article also included a technology to promote PA. 96 This was a smartphone app to monitor the length and intensity of users’ PA and to tell them when their goals had been reached. The aim was to assess the relation of users’ PA behavior to self-reported PA barriers. While barriers were not considered in the technology employed in the article, the study also aimed to consider barriers for future technology design, as it collected users' opinions on the app to inform this. In particular, this article recommended that future interventions may provide financial incentives (motivation), incorporate a social component (influence of others, company) and include different PA activities (e.g. walking; challenge, and difficulty) according to the user’s PA level.

Overall, we consider that it is crucial to consider the potential variables when developing a PA intervention. Recommendations have been made to consider all possible mediating variables to PA when developing an intervention 25 and a relationship has been found between a technological intervention relying on a theoretical basis and the effectiveness of the technology. 27 Future work should aim to verify the importance of the identified variables to bring stronger support to their importance in considering them in the design of technology for PA.

Discussion

This study was conducted to address the need for considering the non-demographic variables of PA when developing technological interventions for the promotion of PA, and to investigate the relevance of these variables in relation to a person’s PA level and body weight. We chose an atheoretical approximation due to the absence of specific theories explaining the PA behavior 29 and also to explore other possible variables. 25 By doing so, we can ensure that potentially important variables for PA are not excluded in studies. For the achievement of our goals, we have presented the variables appearing in the psychological/psychiatric literature in relation to PA and the effect of body weight on them; and we have highlighted the lack of consideration of these variables in the computing literature.

Non-demographic barriers to PA

PA seems to be affected by several variables. We have found 38 potential variables stated as barriers or facilitators to PA in the literature. It is advantageous to have all these variables compiled in one study to have a general view since none of the studies reviewed has considered all the variables presented here. Moreover, a previous study exploring the literature about barriers in the obese population reported 12 barriers. 73 We have considered a wider picture by including the facilitators in our review and including all weight categories (not only obese). In fact, while the aforementioned study included 17 studies for reviewing in the final sample, ours includes 50 studies from the Psychology literature and 15 from Computing. However, all of the barriers presented in 73 have also been identified in our review, which indicates a congruence of the findings. In our case, excess body weight is included within the variable fitness and perception of own body weight and includes stigma as social influence, self-esteem, and self-consciousness. In addition to this information, 21 articles measured PA potential variables through a qualitative methodology, 25 articles used a quantitative methodology, and 4 articles a mixed approach. We have not analyzed if the variables showed any differences depending on the way in which they were measured, but this could be an interesting aspect to explore in the future.

The most reported variable is motivation, followed by company, influence of others, knowledge, priorities, and fear. The least reported variable is routine, followed by housework, policies, awareness, and appealing aesthetics. It is possible that some variables are reported more often in the reviewed studies than others because they are present in the existing tools rather than due to their prevalence in the population. In fact, when questioned about PA barriers, people report many more barriers than the ones in questionnaires.84,70 Since we aim to identify all the variables in the literature affecting PA, irrespective of their appearance in previous behavior theories, we suggest treating all the presented variables equally to avoid excluding potentially important variables by focusing only on those highlighted by Michie et al. 29 Indeed, many of the specific variables that we present here are not considered by the often-used behavior change theories for explaining PA behavior.142–144 While these theories focus on more general aspects that can affect different health behaviors, they do not consider specific aspects of PA. Yet, the individual components should be studied to understand which of them could make an intervention effective, 25 and breaking down each component into minor variables allows for studying the specific effects. Thus, interventions can be optimized by focusing only on the relevant aspects influencing PA. For example, engagement in health behaviors in the Health Belief Model (HBM).145,146 depends on how severe the health problem is perceived to be and how susceptible people feel themselves to be. However, in the case of PA, medical conditions are usually reported as barriers, not as facilitators.82,93,133

Barriers according to PA level

Understanding the relationship of each variable with the PA level is fundamental for their inclusion in intervention design for behavior change. However, some reviewed studies evaluate the relationship of the variables presented with a person’s PA level as they do not use an actual measure of PA levels. Our literature review shows the relation with a person’s PA level for only a few variables (see the third column in Table 1), which should be prioritized over others for the inactive population. These are company, motivation, difficulty—only when regarded as a barrier but not as a facilitator—initiative, willpower and commitment, and knowledge. In some cases, such as for emotional/psychological state, the actual relation with PA level has been reported only in the technological literature. This means that while emotional/psychological state has been identified in the psychological literature as influencing PA, the studies reporting that influence do not actually measure PA levels or examine differences between groups of the population differing in their PA level.

For other variables, we have not found consensus concerning whether there is any relation between them and PA level (e.g. influence of others, fear). This absence of consensus can be due to study methodological differences. For example, for self-efficacy there is a relation with the PA level in most cases, but 115 does not find a correlation. This could be because in 115 PA was measured within a particular long-term intervention involving a 12-month facility- and home-based exercise program, while most of the other studies80,84,86,87,90,120 did not have an intervention or had a shorter-term intervention involving more moderate PA (wear a pedometer for 8–9 weeks103,119); this intervention type may not have the same effect as other PA kinds. Finally, while the relation with the PA level has not been mentioned in the literature for the majority of the variables, it is possible that in other medical fields, measures of PA are more commonly employed and studied in relation to PA barriers than the ones we studied from PsycInfo. It should however be noted that PsycInfo does include various medical journals and thus it also provides an understanding of that field.

Barriers according to body weight

We have also found that the effect of the identified variables over PA can be dependent on the population under study.78,91,94,96 A particularly relevant aspect influencing the effect of the variables is body weight. In our reviews, we further explored the specificities of the barriers to PA for the overweight/obese population. Though this population has the same barriers to PA as the healthy-weight population, some barriers were more important for them. In this population the effect of social influence is particularly important for several reasons: first, there is more reported reliance on social cues 99 ; second, lack of social support is reported as a barrier more often in the obese than non-obese population 91 ; third, the influence of others is related to the PA level only in the overweight/obese population 121 ; and finally, the incidence of negative social influence (e.g. teasing) can be higher for overweight/obese women.79,87 Thus, social influence should be especially considered in the development of interventions for PA for this population. Another relevant variable is lack of enjoyment, considered as the main cause of low exercise levels in obese women. 90 However, 91 found no significant differences in lack of enjoyment as a barrier to PA between different weight groups of women. Since there are a few variables that are more reported by the overweight/obese than the healthy-weight population, it is important to study if the influence of enjoyment is mediated by other variables as a possible explanation. For example, one study found that obese women are more likely to agree that they only exercise when trying to lose weight. 93 Since the motives to exercise are not usually intrinsic to activity in this group, it is expected to find motives more external to the activity in itself. Population specificity in certain studies can also lead to a greater homogeneity, and make other possible influences disappear. For example, the discrepancy about whether reporting initiative, willpower, and commitment as a barrier is dependent on weight groups can come from the fact that the only article finding no differences 91 handles a population of African American breast cancer survivors, while those finding differences52,121 handle broader populations. Finally, in contrast, barriers related to time demands are reported to be lower for the overweight or obese population. 121

In this work, we have only reviewed the variables reported in the articles that include the term “obesity,” but considered all body weights. Thus, based on our results we propose to prioritize the following factors in the development of interventions for PA for the overweight/obese populations: influence of others,79,87,91,99,121 fear of injury, 91 self-consciousness, 52 and self-confidence87,93 about one’s looks (leading to not wanting to exercise in front of others79,93), knowledge (e.g. receiving health messages related to PA 131 ), motivation, and potentially, initiative, willpower, and commitment (according to Refs. 52,121, although Ref. 91 reports no differences between weight groups). In relation to motivation, one study reported that the variable lack of enjoyment is the main cause of physical inactivity in obese women 90 , although there is no consensus about it, 91 perhaps as this variable may be mediated by other variables. Nevertheless, obese women seem to only find external (versus intrinsic) motives to exercise. 93 Nevertheless, we acknowledge the importance of considering individual differences in PA barriers.

Considering other individual factors

Given the above findings for the overweight or obese population, it is possible that a similar “barrier augmentation” effect takes place for other specific populations, that is, the barriers can be the same for the general population but can be bigger barriers to PA in the overweight/obese population or can have a different effect in them in some specific cases. Ideally, all the potential variables for the general and specific populations should be known, to be able to identify the relevant ones in each case and evaluate which aspects should be considered or prioritized in the development of PA-related interventions. Considering the different barriers faced by different populations would allow designing guidelines on factors to be prioritized for interventions for specific groups (e.g. with different PA levels or BMI). A general overview of the effects of these variables over PA is an important first step for designing PA interventions but a necessary second step includes evaluating their relevance in any given situation when developing PA interventions, as the presence or influence of different variables could vary between populations. For example, ethnicity, age, and economic stability affect whether self-consciousness is reported as influencing PA 96 ; lack of willpower was not reported as a barrier by Hispanic students 119 ; lack of self-confidence appears to be more likely reported as a barrier in younger adults than in older adults 94 ; and fear as a barrier appears to be higher in older adults than in younger adults, 94 in women than men, 78 and in non-college educated women. 91

Design recommendations for technology addressing PA barriers

Literature Review 1 provided insights as to what needs should be addressed for facilitating adherence to PA overall, and about the prioritization of factors for people who are physically inactive or overweight/obese. While we recognize the importance of considering these factors influencing PA in the development of technological interventions that aim to increase participation in PA, Review 2 highlights that psychological barriers are mostly overlooked in the design of technology. Most work on technology to promote PA uses cognitive-behavioral approaches that are based on motivating, planning, and getting social support, but are not designed to support an analysis of the underlying problem; the focus is often placed on how to enhance positive emotions through intervention (e.g. with badges to mark achievements) but this approach falls short if motivation is not the barrier to PA. 72

We propose a rethink of PA technologies by considering psychological factors holistically and systematically in the design process. The conducted reviews provided valuable insights as to how technology could help address some of the psychological factors to promote higher participation in PA. Based on our reviews, we provide the following recommendations for technological interventions focused around three main topics: (i) integrating social features into the design, (ii) identifying opportunities for PA and helping to establish PA goals and routines, and (iii) regulating emotional/psychological state:

Integrate social features into the design: Our results show that technology should support the social aspect of PA, in four different ways. (1) By integrating features that facilitate scheduling workouts with others (e.g. with people they know or in person exercise programs), for instance by integrating a scheduler application shared with social media contacts that promotes awareness of friends’ activities and opportunities to join in; this relates to company, but also, it may facilitate making exercise a priority.105,106,108,116 (2) By providing social incentives to motivate people to exercise, for instance by using fitness tracking tools, 124 or by making public announcements of PA commitments in social networks, 126 which relate to the variables, influence of others and discipline, initiative, willpower, and commitment. Here it is important to profile users into low and high persistence users, as the latter may need additional motivational interventions, as well as to understand why they do not follow other users as effective role models. 127 Also, it is important to consider whether competition should be emphasized or de-emphasized for individual users: while competition seems to be effective for the average population, 128 for some individuals (e.g. obesity, diabetes) the focus should be on supporting strong ties between team members. 124 (3) By allowing following others as effective role models 127 which also relate to the influence of others. (4) By integrating social assistance 126 and professional advice.

Identify opportunities for PA and help in establishing PA goals and routines: personal informatics should allow tracking, collection, and integration of various types of information on PA and contextual information (using monitoring devices or calendaring systems) and allow linking multiple facets of people’s life (at home, at work, daily social interactions, PA)107,125, to increase awareness of personal limitations and of opportunities for PA. For instance, the system could provide users with detailed feedback on their PA and the contribution of common daily activities (e.g. household activities) to their PA level. 136 The system could also integrate a virtual coach, providing suggestions based on calendar and observed patterns, 107 and help to establish and adapt to routines, 106 as well as to set PA goals. PA goals should be concrete and challenging, but attainable, and conveyed in an easy and straightforward manner, which relates to challenges and difficulties. 136 For instance, according to the user’s PA level, different PA activities could be suggested (e.g. walking or running). 96

Regulate emotional/psychological state: Related to the previous point, personal informatics could also help to apply self-regulatory mechanisms to drive motivation and goal attainment, 136 and to find enjoyable activities to support PA 106 and experience. One example 105 is the use of music while exercising by adjusting the music to the pace, workout type or mood of the users, to regulate their emotional state and motivate them. 105

Future research should study the integration of other factors in technology design to promote participation in PA, and especially to consider that while certain interventions may work for the general population or for a specific population, they may not work for other population groups. An example is when depression affects PA80,95; while using music while exercising has been suggested as an effective tool to adjust the mood of users and motivate them, 105 the same type of intervention may not work to adjust the mood of people with depression. We acknowledge that none of the reviewed technologies studies looked at the psychological consequences of using the wrong intervention. We suggest that, rather than thinking of a unique intervention, it may be more effective to think in terms of structured interventions, where different needs are addressed at different times; this requires first identifying the pre-requisites for applying specific interventions (e.g. enhancing positivity towards one’s body prior to apply interventions integrating social features). A first and necessary step for this is to find out the most important barriers to PA for the targeted users, to then center the design and the evaluation of the interventions around the identified barriers.

Finally, we highlight the fact that all the interventions performed in the reviewed studies involve top-down cognitive-behavioral mechanisms, but recent works have started to demonstrate the potential of using bottom-up mechanisms. For instance, one can involve these mechanisms to change self-perception, bringing positivity to the perception of one’s body and one’s own physical capabilities, and in turn affect PA.60,42,147–151 Future works should investigate the combination of top-down and bottom-up mechanisms to address PA barriers in structured interventions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study has highlighted the importance of all the specific PA variables reported in the articles reviewed, in total 38 variables (21 psychological, 5 physical, 12 personal/contextual), which should be taken into account when developing interventions for the promotion of PA. Moreover, the body weight aspect must be also considered, as it can be associated with the variable effect. The Computing field should be particularly made cognisant of the importance of basing the intervention developments on the knowledge of the PA variables as a means of building on the literature and evidence and adding to it; our study has demonstrated a lack of enough consideration for such variables, which means that studies do not build on the existing evidence base efficiently and effectively. This paper is a step forward to building a tool for supporting designers in understanding the PA problem they are designed for and setting the measures they need to assess the efficacy of their technology-based design. In particular, our study can be used to develop systematic tools that could be used to explore the variables that affect PA and how PA-related applications are affected by them, to inform the design and the evaluation of new PA interventions.

Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations of this work. First, the systematized reviews were not pre-registered. Further, only one author reviewed the articles for their inclusion, the search period was limited to 10 years (2007–2017) and we used only one database per search; these elements could be considered limitations but they are common and standard in the method followed in systematized reviews. Hence, there is a possibility of some barriers and facilitators being missed. However, our analysis suggests that the possibility of this is small as the principal variables are repeated several times across articles and just a small proportion of variables appear only once. Further, a quality assessment of the included articles was not performed, but at the same time adding specific quality criteria would have entailed the risk of biasing the selection process and ending up with a skewed sample or missing relevant barriers as noted e.g. by Snyder. 61 In addition, the articles considered were all peer-reviewed and included in the PsycInfo/ACM databases implying an existing quality filter. Second, restricting the literature review by introducing the word “obese” prevents us from asserting that the variables presented represent all the potential variables for PA in the general population. Future work should gather and present information for a wider population sample.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076221116559 for Investigating psychological variables for technologies promoting physical activity by Patricia Rick, Milagrosa Sánchez-Martín, Aneesha Singh, Sergio Navas-León, Mercedes Borda-Mas, Nadia Bianchi-Berthouze and Ana Tajadura-Jiménez in Digital Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-dhj-10.1177_20552076221116559 for Investigating psychological variables for technologies promoting physical activity by Patricia Rick, Milagrosa Sánchez-Martín, Aneesha Singh, Sergio Navas-León, Mercedes Borda-Mas, Nadia Bianchi-Berthouze and Ana Tajadura-Jiménez in Digital Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-dhj-10.1177_20552076221116559 for Investigating psychological variables for technologies promoting physical activity by Patricia Rick, Milagrosa Sánchez-Martín, Aneesha Singh, Sergio Navas-León, Mercedes Borda-Mas, Nadia Bianchi-Berthouze and Ana Tajadura-Jiménez in Digital Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-dhj-10.1177_20552076221116559 for Investigating psychological variables for technologies promoting physical activity by Patricia Rick, Milagrosa Sánchez-Martín, Aneesha Singh, Sergio Navas-León, Mercedes Borda-Mas, Nadia Bianchi-Berthouze and Ana Tajadura-Jiménez in Digital Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-5-dhj-10.1177_20552076221116559 for Investigating psychological variables for technologies promoting physical activity by Patricia Rick, Milagrosa Sánchez-Martín, Aneesha Singh, Sergio Navas-León, Mercedes Borda-Mas, Nadia Bianchi-Berthouze and Ana Tajadura-Jiménez in Digital Health

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Spanish Agencia Estatal de Investigación project grants “Magic Shoes” (PSI2016-79004-R/AEI/FEDER, UE) and “MAGIC outFIT” grant (MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/; project id PID2019-105579RB-I00), and by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 101002711). AT was supported by the RYC-2014–15421 grant from the “Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad”. SNL was supported by the FPU program from the Spanish Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte (FPU20/00089).

Ethical approval: The ethics committee of Universidad Loyola Andalucía and of Junta de Andalucía approved this study [Code: ULA-PSI2016-350105. Approval no. 20181241335, 24 January 2018].

Guarantor: AT.

Contributorship: The protocol for the study was developed by PR, MS, AS, MB, NB, and AT. The classification of variables was conducted by PR and revised by MS, AS, NB, and AT. The first draft of the manuscript was written by PR, MS, and AT and revised by all authors.

Peer review: XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX.

ORCID iD: Aneesha Singh https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0835-5802

Ana Tajadura-Jiménez https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3166-3512

Supplemental material: Supplementary material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.WHO - World Health Organization. Spain-Fact sheet on physical activity, http://www.euro.who.int/data/assets/pdf_file/0008/382580/spain-eng.pdf?ua=1 (2018, accessed 2020 March 06).

- 2.Ebrahim S, Garcia J, Sujudi A, Atrash H. Globalization of behavioural risks needs faster diffusion of interventions. Prev Chronic Dis 2007; 4(2): A32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO - World Health Organization. Country profiles on nutrition. physical activity and obesity in the 53 WHO European Region Member States. Methodology and summary, http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/243337/Summary-document-53-MS-country-profile.pdf?ua=1 (2013, accessed 2020 March 06).

- 4.WHO - World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity (2018, accessed 2020 March 06).

- 5.Cairney J, Hay JA, Faught BE, Wade TJ, Corna L, Flouris A. Developmental coordination disorder, generalized self-efficacy toward physical activity, and participation in organized and free play activities. J Pediatr 2005; 147(4): 515–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centre for Economics and Business Research. The economic cost of physical inactivity in Europe: An ISCA/Cebr Report, https://inactivity-time-bomb.nowwemove.com/download-report/The%20Economic%20Costs%20of%20Physical%20Inactivity%20in%20Europe%20(June%202015).pdf (2015, accessed 2020 March 06).

- 7.Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dunstan DW, Winkler EAH, Owen N. Sedentary time and cardio-metabolic biomarkers in US adults: NHANES 2003–06. Eur Heart J 2011; 32(5): 590–597. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Health at a glance 2017: indicators, https://www.health.gov.il/publicationsfiles/healthataglance2017.pdf (accessed 2020 June 03).

- 9.WHO - World Health Organization. Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44203/9789241563871_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (2009, accessed 2020 March 06).

- 10.Wilmot EG, Edwardson CL, Achana FA, et al. Sedentary time in adults and the association with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2012; 55(11): 2895–2905. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2677-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO - World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/148114/9789241564854_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (2014, accessed 2020 March 06).

- 12.Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, et al. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. The Lancet 2012; 380(9838): 247–257. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60646-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price M, Yuen EK, Goetter EM, et al. mHealth: a mechanism to deliver more accessible, more effective mental health care. Clin Psychol Psychother 2014; 21(5): 427–436. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakhasi CA, Shen AX, Passarella RJ, Appel LJ, Anderson CA. Online social networks that connect users to physical activity partners: a review and descriptive analysis. J Med Internet Res 2014; 16(6): e153. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vroege DP, Wijsman CA, Broekhuizen K, et al. Dose-response effects of a web-based physical activity program on body composition and metabolic health in inactive older adults: Additional analyses of a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2014; 16(12): e265. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alley S, Jennings C, Plotnikoff RC, Vandelanotte C. Web-based video-coaching to assist an automated computer-tailored physical activity intervention for inactive adults a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2016; 18(8): e223. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Althoff T, White RW, Horvitz E. Influence of Pokémon go on physical activity: study and implications. J Med Internet Res 2016; 18(12): e315. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crossley SG, McNarry MA, Eslambolchilar P, Knowles Z, Mackintosh KA. The tangibility of personalised 3D printed feedback may enhance youth's physical activity awareness, goal-setting and motivation. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019; 21(6): e12067. doi: 10.2196/12067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wanner M, Martin-Diener E, Braun-Fahrländer C, Bauer G, Martin BW. Effectiveness of active-online, an individually tailored physical activity intervention, in a real-life setting: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2009; 11(3): e23. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Napolitano MA, Fotheringham M, Tate D, et al. Evaluation of an internet-based physical activity intervention: a preliminary investigation. Ann Behav Med 2003; 25(2): 92–99. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2502_04. [Medline: 12704010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner-McGrievy G, Tate D. Tweets, Apps and Pods: results of the 6-month Mobile Pounds Off Digitally (Mobile POD) randomized weight-loss intervention among adults. J Med Internet Res 2011; 13(4): e120. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukuoka Y, Lindgren TG, Mintz YD, Hooper J, Aswani A. Applying natural language processing to understand motivational profiles for maintaining physical activity after a mobile app and accelerometer-based intervention: the mPED randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018; 6(6): e10042. doi: 10.2196/10042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson WR. Worldwide survey of fitness trends for 2019. ACSMs Health Fit J 2018; 22(6): 10–17. doi: 10.1249/FIT.0000000000000438 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eckerstorfer LV, Tanzer NK, Vogrincic-Haselbacher C, et al. Key elements of mHealth interventions to successfully increase physical activity: meta-regression. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018; 6(11): e10076. doi: 10.2196/10076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baranowski T, Anderson C, Carmack C. Mediating variable framework in physical activity interventions how are we doing? How might we do better? Am J Prev Med 1998; 15(4): 266–297. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00080-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bort-Roig J, Gilson ND, Puig-Ribera A, Contreras RS, Trost SG. Measuring and influencing physical activity with smartphone technology: a systematic review. Sports Med 2014; 44(5): 671–686. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0142-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orji R, Moffatt K. Persuasive technology for health and wellness: state-of-the-art and emerging trends. Health Informatics J 2018; 24(1): 66–91. doi: 10.1177/1460458216650979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aldenaini N, Alqahtani F, Orji R, Sampalli S. Trends in persuasive technologies for physical activity and sedentary behavior: a systematic review. Frontiers in artificial intelligence 2020; 3: 7. 10.3389/frai.2020.00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011; 6(1). doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dijk EK, Westerink JHDM, Beute F, IJsselsteijn WA. Personal informatics, self-insight, and behaviour change: a critical review of current literature. Hum–Comput Interaction 2017; 32(5-6): 268–296. doi: 10.1080/07370024.2016.1276456 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conn VS, Hafdahl AR, Mehr DR. Interventions to increase physical activity among healthy adults: meta-analysis of outcomes. American Journal of Public Health 2011; 101(4): 751–758. 10.2105/AJPH.2010.194381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gourlan M, Bernard P, Bortolon C, Romain AJ, Lareyre O, Carayol M, Ninot G, Boiché J. Efficacy of theory-based interventions to promote physical activity. A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Health Psychology Review 2016; 10(1): 50–66. 10.1080/17437199.2014.981777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brand R, Cheval B. Theories to explain exercise motivation and physical inactivity: ways of expanding our current theoretical perspective. Frontiers in Psychology 2019; 10(May): 1–4. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barreto dS. Why are we failing to promote physical activity globally? Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2013; 91(6): 390–390A. 10.2471/BLT.13.120790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hagger MS, Weed M. DEBATE: do interventions based on behavioral theory work in the real world? International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2019; 16(1): 1. 10.1186/s12966-019-0795-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robbins LB, Pender NJ, Kazanis AS. Barriers to physical activity perceived by adolescent girls. J Midwifery Womens Health 2003; 48(3): 206–212. doi: 10.1016/s1526-9523(03)00054-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rimmer JH, Riley B, Wang E, Rauworth A, Jurkowski J. Physical activity participation among persons with disabilities. Am J Prev Med 2004; 26(5): 419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brazeau AS, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Strychar I, Mircescu H. Barriers to physical activity among patients with Type 1. Diabetes Care 2008; 31(11): 2108–2109. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simons D, Clarys P, De Bourdeaudhuij I, de Geus B, Vandelanotte C, Deforche B. Factors influencing mode of transport in older adolescents: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2013; 13(1): 323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huybrechts I, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Buck C, De Henauw S. Environmental factors: opportunities and barriers for physical activity, and healthy eating among children and adolescents. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 2010; 53(7): 716–724. doi: 10.1007/s00103-010-1085-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh A, Piana S, Pollarolo D, et al. Go-with-the-flow: tracking, analysis and sonification of movement and breathing to build confidence in activity despite chronic pain. Human-Computer Interact 2016; 31(3–4): 335–383. doi: 10.1080/07370024.2015.1085310 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh A, Klapper A, Jia J, et al. Motivating people with chronic pain to do physical activity: opportunities for technology design. In: Proceedings of the 32Nd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto. Ontario, 2014 Apr 26–May 1. Canada. [doi: 10.1145/2556288.2557268]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh A, Bianchi-Berthouze N, Williams AC. Supporting everyday function in chronic pain using wearable technology. In: Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2017 May 6–11, Denver. Colorado. USA. [doi: 10.1145/3025453.3025947]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cerin E, Leslie E, Sugiyama T, Owen N. Perceived barriers to leisure-time physical activity in adults: an ecological perspective. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 2010; 7(4): 451–459. 10.1123/jpah.7.4.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh T-J, Roberts B-B, Williams CC. Going beyond motivation! A framework for the design of technology for supporting physical activity where mobility is restricted. In: Proceedings of the 1st GetAMoveOn Annual Symposium, London. UK, 2017 May 25. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galan-Lopez P, Sanchez-Oliver AJ, Pihu M, Gísladóttír T, Domínguez R, Ries F. Association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and physical fitness with body composition parameters in 1717 European adolescents: The AdolesHealth Study. Nutrients 2020; 12(1): 77. doi: 10.3390/nu12010077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Health Organization (WHO). Body mass index – BMI, http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle/body-mass-index-bmi (accessed 2020 June 03).

- 48.WHO - World Health Organization. Fact sheet on obesity and overweight 2018, http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (2020, accessed 2020 March 06).

- 49.Inactivity Time Bomb. http://inactivity-time-bomb.nowwemove.com/download-report/The Economic Costs of Physical Inactivity in Europe (accessed 2017 June 04).

- 50.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Health at a glance 2013: indicators, https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Health-at-a-Glance-2013.pdf (accessed 2020 June 03).

- 51.Deforche B. Physical activity and fitness in overweight and obese youngsters. [PhD Thesis]. NL: Ghent University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Napolitano MA, Papandonatos GD, Borradaile KE, Whiteley JA, Marcus BH. Effects of weight status and barriers on physical activity adoption among previously inactive women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011; 19(11): 2183–2189. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]