Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (dronabinol [DRO]) as an add-on treatment in patients with refractory chronic pain (CP).

Methods

An exploratory retrospective analysis of 12-week data provided by the German Pain e-Registry on adult patients with treatment refractory CP who received DRO.

Results

Between March 10, 2017, and June 30, 2019, the German Pain e-Registry collected information on 89,095 patients with pain, of whom 1,145 patients (1.3%) received DRO (53.8% female, mean ± standard deviation age: 56.9 ± 10.6 years), and 70.0% documented use for the entire 12-week evaluation period. The average DRO daily dose was 15.8 ± 7.5 mg, typically in three divided doses (average DRO dose of 5.3 ± 2.1 mg). Average 24-hour pain intensity decreased from 46.3 ± 16.1 to 26.8 ± 18.7 mm on a visual analog scale (absolute visual analog scale difference: –19.5 ± 17.3; P < 0.001). Among patients who completed follow-up, an improvement from baseline of at least 50% was documented for pain (46.5%), activities of daily living (39%), quality of life (31.4%), and sleep (35.3%). A total of 536 patients (46.8%) reported at least one of 1,617 drug-related adverse events, none of which were serious, and 248 patients (21.7%) stopped treatment. Over the 12-week period, 59.0% of patients reported a reduction of other pain treatments, and 7.8% reported a complete cessation of any other pharmacological pain treatments.

Conclusion

Add-on treatment with DRO in patients with refractory CP was well tolerated and associated with a significant improvement.

Keywords: Dronabinol, Add-on Treatment, Chronic Pain, Retrospective Analysis, German Pain e-Registry

Background

Chronic pain (CP) is a painful sensory and emotional experience that persists beyond physiological healing time [1, 2]. CP has a major impact on QoL and interferes with daily life activities, as well as with working ability and productivity. Consequently, CP is responsible for considerable disability compensation and is associated with comorbidities, including depression, anxiety, and stress. CP affects between 12% and 30% of people in industrialized countries [3–6], meaning that CP has significant medical and economic impact [7–9].

The majority of treatment guidelines for the management of CP recommend multimodal nonpharmacological strategies incorporating medical, psychosocial, physiotherapeutic, and other disciplines [10–12]. Pharmacological measures include muscle relaxants (in case of increased muscle tone), with adjuvant agents (e.g., Ca2+-channel modulating anticonvulsants, tricyclic antidepressants, and selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors) if patients with CP present with neuropathic pain [13–20]. Despite these approaches, CP frequently persists, and patients seek complementary measures and interventional or even neurosurgical approaches [21, 22].

In response to this challenge, the Federal Parliament of Germany adopted the Act Amending Narcotics and Other Regulations [23] on March 10, 2017. This allows physicians to prescribe cannabis-based medicines (CBMs) for patients suffering from severe diseases, such as CP, according to the definitions given in Code V of the German Social Law, and it obliges health insurance to reimburse costs associated with prescriptions for patients whose symptoms or conditions are resistant to other treatments.

However, the available scientific evidence for CBMs supporting this approach in CP is low [24]. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses on CBMs in CP reflect uncertainty as to whether CBMs are able to relieve pain or pain-related disabilities, and they provide only limited and low-quality evidence—frequently confounded by the fact that different cannabinoid-based products with variable cannabinoid profiles, doses, and routes of administration are often blended [25, 26]. This contrasts with emerging data from preclinical studies addressing different physiological activities of CBMs (and their two main components, tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol) and proposing potential impacts on CP. An increasing amount of real-world evidence is also being generated that suggests that there is at least a subset of patients with CP refractory to conventional treatments who report clinically meaningful and sustained improvements in response to CBM [27].

In view of this, the German Pain Association initiated a retrospective analysis to explore the effectiveness and tolerability of dronabinol (DRO)—the CBM with the longest tradition in the use in pain and palliative care medicine in Germany—in patients with refractory and severe CP.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective analysis of patients with CP who started treatment with DRO as part of routine care and were evaluated over the course of 12 weeks. Anonymized data were extracted from the German Pain eRegistry (GPeR), a national Web-based pain treatment registry developed in cooperation with the German Pain Association, to examine real-world responses to DRO.

Study Objective

The objective of this study was to gain insights into the effectiveness and tolerability of DRO among adult patients with refractory CP.

Study Medication

Dronabinol (DRO) is the chemical name for synthetic or naturally derived delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC). Tetrahydrocannabinol is the main psychoactive active ingredient of Cannabis sativa and has been available in Germany by individual prescription in capsules or oil since 1998 and with other CBMs since 2017. Furthermore, insurance coverage in Germany is available if 1) the patient suffers from a serious medical illness; 2) for which approved and recommended treatments are not available, did not work, or cannot be used because of tolerance problems or contraindications with concurrent comorbid conditions; and 3) there is a reasonable prospect for a meaningful effect on the course of the illness or serious symptoms.

Because of the real-world design of this study, no formal dosing guidelines were established. Analgesic treatment with DRO was based on shared decisions of the participating physicians and their patients, according to individual patient needs and regulatory conditions.

Study Population and Sample Size

There was no formal sample size calculation for this analysis. The statistical analysis was based on the routine data of the GPeR in patients with severe CP treated between March 10, 2017, and June 30, 2019, who received treatment with DRO for the first time and who reported their response to the treatment by using the GPeR. Treatment initiation was defined as occurring in those with no previous use of DRO, and the date of the first dose of DRO was set as the starting date for the 12-week data evaluation period.

Data Source

This analysis is based on fully denominalized data extracted from the GPeR. All analyses were carried out retrospectively on data available up to June 30, 2019.

The GPeR was developed to provide patients and physicians with a standardized database to gather, evaluate, and compare patient-reported information on demographics, medical history, pretreatment, pain characteristics, and treatment response under real-world conditions. Data were self-reported by patients and supplemented by physician information where appropriate. By the end of December 2020, members of the GPeR network included 768 pain specialists, 795 physicians, and 2,548 nonmedical pain experts, such as psychotherapists and physiotherapists, who worked in 213 pain centers throughout Germany and who cared for ∼200,000 pain patients per quarter.

Study Assessments

Effectiveness Evaluation

Patient questionnaires provided by GPeR were those recommended by the German Pain Association, the German Pain Society, and the German Pain League, and they document a broad spectrum of outcomes through the use of validated instruments [28, 29].

Data were collected on pain intensity, pain-related disabilities in daily life activities/functionality, sleep, overall well-being, and quality of life (QoL). Pain intensity was measured with the pain intensity index (PIX), calculated as arithmetic mean of the lowest, average, and highest 24-hour pain intensities reported by patients on a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS; 0 = “no pain” and 100 = “worst pain conceivable”). CP-related disabilities with respect to daily life activities were assessed with a modified German version of the Pain Disability Index (mPDI), which recorded the degree of functional restrictions in daily life with respect to seven distinct domains (related to home and family activities, recreation, social activities, occupation, self-care and personal maintenance, sleep, and overall QoL) on a 100-mm VAS (with 0 = “none” and 100 = “worst conceivable”) [30, 31]. Quality of sleep was evaluated with the mPDI6 (sleep) subdomain. QoL was measured with the Physical Component Summary and Mental Component Summary (PCS/MCS) of the SF-12 Health Survey version 2 [32]. The Marburg Questionnaire on Habitual Health Findings (MQHHF) was used to assess subjective overall well-being, and the Quality of Life Impairment by Pain (QLIP) inventory was used to gain insight into pain-related QoL restrictions [31, 33].

Patients completed standardized pain diaries by using the German Pain e-Diary (consisting of the same aggregate of validated instruments as the German Pain Questionnaire) via the Web application iDocLive® (O.Meany-MDPM GmbH, Nuernberg, Germany). No predefined study visits were scheduled, and interim visits/documentations were possible at any time according to individual patient needs or established routines.

Concomitant Medication

No limitations were placed on the use of DRO or concomitant medications. Physicians were able to prescribe, and patients were free to take, any medications and nonpharmacological measures as necessary, but they were asked to document any treatment changes.

Safety and Tolerability Measures

Safety analyses were based on drug-related adverse event (DRAE) reporting, collected by the GPeR. DRAEs were defined as any untoward medical occurrence reported by a patient receiving DRO and did not necessarily confirm a causal relationship with the treatment under evaluation. DRAEs reported were encoded with the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA, version 22.0, 2019).

Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were performed on the complete set of anonymized data provide by the GPeR for patients who fulfilled the aforementioned criteria. Analyses followed a modified intention-to-treat approach, as any patients who recorded the intake of at least one dose of DRO and who had at least one post-baseline or post-dose documentation were evaluated. Linear interpolation was used to impute intermittent missing scores, and the last-observation-carried-forward method was used to impute missing scores after early discontinuation. The corresponding completed data set formed the basis for all analyses.

Data were evaluated with appropriate descriptive statistical methods. For all variables, the number of available or unavailable values (nonmissing or missing data) were given, irrespective of the data level. For nominally and ordinally scaled categorical data, the absolute and relative (adjusted) frequencies were calculated, and cumulative values for ascending/descending scale levels were displayed. Interval scaled data were represented by mean value, standard deviation, median, range (minimum–maximum), and 95% confidence interval. Where possible and reasonable, additional cutoff values were grouped categorically and provided with corresponding frequency analyses. The use of biometric test procedures (the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and Student t test for continuous variables with non-normal and normal distributions, respectively, and the McNemar test for categorical parameters) served exclusively for post hoc analyses of the biometric significance of changes in findings observed during treatment in comparison with the initial finding before the start of treatment with DRO (so-called baseline), and not for the examination of predefined questions or hypotheses. All corresponding tests were evaluated with a statistical significance level of 0.05, and the test procedures used were adapted to the scale level of the variables to be analyzed. Statistical test procedures were all exploratory in nature, and therefore no adjustments were made with regard to multiple comparisons.

The following endpoints were calculated and considered in a primary endpoint analysis concerning the definitions of response (partial or complete) and nonresponse (therapy failures):

Responders were defined as those with 50% or greater improvements over baseline in 1) average 24-hour pain intensity (PIX), 2) pain-related disabilities in daily life (mPDI), 3) pain-related QoL restrictions (QLIP), and 4) pain-related quality of sleep (subscale #6 of the mPDI).

Nonresponders were defined as those with any premature treatment discontinuation due either to a DRAE or to an inadequate analgesic effect of the treatment under evaluation, defined as less than 30% reduction in 1) average 24-hour pain intensity (PIX), 2) pain-related disabilities in daily life (mPDI), 3) pain-related QoL restrictions (QLIP), and 4) pain-related quality of sleep (subscale #6 of the mPDI).

Patients who did not meet the criteria either for complete response or for nonresponse were classified as partial responders. Because of the exploratory nature of the evaluation, no hypotheses were formulated with regard to the event frequency of the aforementioned primary and secondary endpoint analyses.

Safety and tolerability were described by the frequency and MedDRA coding of reported DRAEs and DRAE-related treatment discontinuations.

Ethics

This study was approved by the ethics committees of the German Pain Association and the German Pain League. Patients and physicians provided written informed consent before participation in the GPeR and agreed to the use of their denominalized data for healthcare research purposes. This study was registered in the electronic database of the European Medicines Agency for noninterventional studies (European Network of Centres for Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance [ENCEPP], European Union electronic Register of Post-Authorisation Studies [EU PAS] #35350).

Results

Patient Disposition

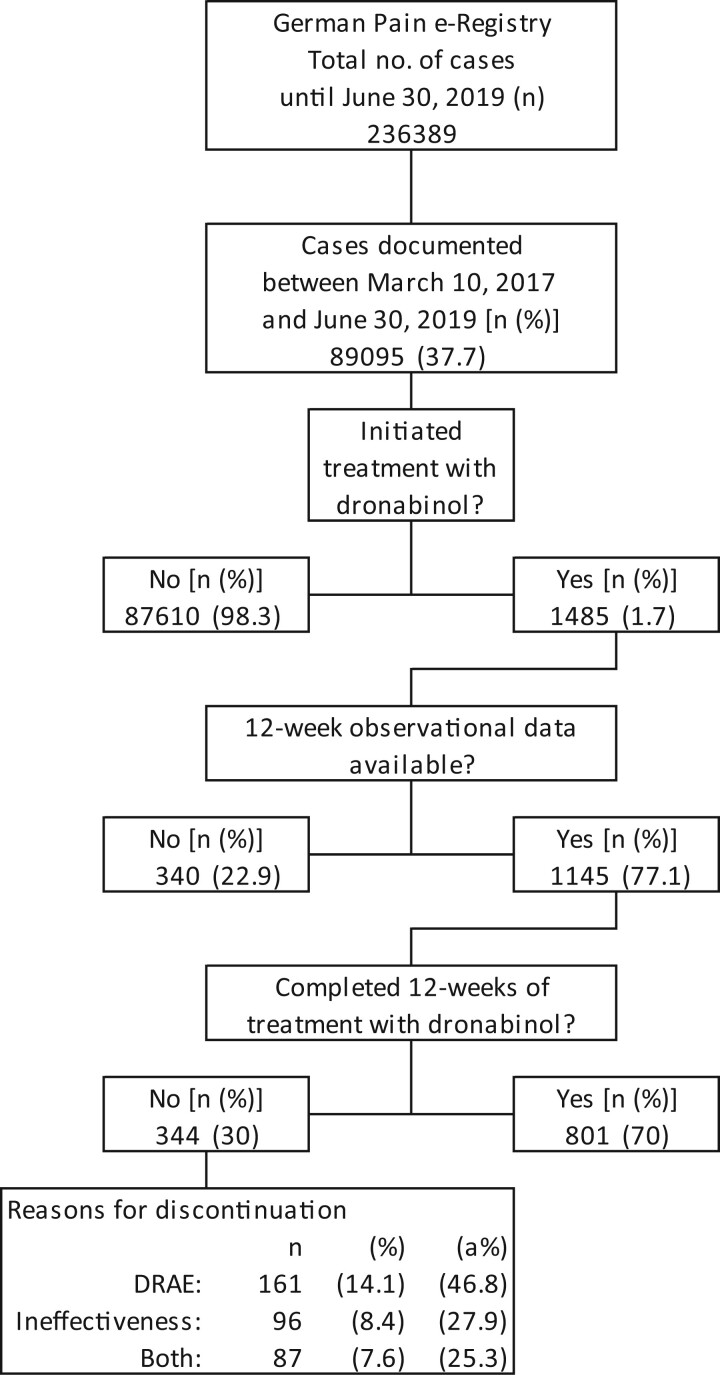

Between March 10, 2017, and June 30, 2019, a total of 89,095 patients participated in the GPeR, of whom 1,485 patients (1.7%) recorded treatment with DRO, and 1,145 (77.1%) completed a 12-week treatment evaluation. Of the 344 patients (30%) who did not complete 12 weeks of follow-up, most discontinued DRO treatment because of DRAEs (n = 161, 14.1%), followed by insufficient analgesic efficacy (n = 96, 8.4%), or a combination of both (n = 87, 7.6%; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram.

Missing/Imputed Data

Overall, 19.2% of the data evaluated for this analysis had to be imputed because of data missing not at random (i.e., because of premature treatment discontinuations) and 1.3% because of incomplete data entries missing at random.

Baseline Characteristics

Demographic data are shown in Table 1. Mean age (± standard deviation) was 56.9 ± 10.6 years (median: 57, range: 24–88), and 53.8% of patients (n = 616) were female. The average pain duration was 1,050.8 ± 707.0 days (median: 969, range: 124–2,827), with 720 patients (62.9%) reporting pain duration greater than 12 months. On average, patients were treated by 8.6 ± 1.4 physicians (median: 9, range: 3–13) and reported a pretreatment history of 7.9 ± 2.3 analgesic medications (median: 8, range: 2–16). One thousand seventy-five patients (93.9%) recorded a history of five or more pain treatments. Antidepressants were the most frequently reported treatments (92.3%), followed by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; 79.8%) and mild and strong opioid analgesics (77.7 and 74.1%, respectively). Patients reported the use of 4.0 ± 1.6 pharmacological pain treatments (median: 4, range: 1–10) at baseline (i.e., as the basis for the add-on treatment with DRO), most frequently with co-analgesics such as antidepressants (88.9%) or anticonvulsants (65.9%), followed by strong opioid analgesics (65.2%). One thousand and seven (87.9%) patients reported five or more nonpharmacological pain treatments, including transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (80.6%), acupuncture (78.3%), and physiotherapy (78.2%).

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Number of patients, n (%) | 1,145 (100.0) |

|---|---|

| Gender female, n (%) | 616 (53.8) |

| Age, mean ± SD (median; range) | 56.9 ± 10.6 (57; 24–88) |

| Body mass index, mean ± SD (median; range) | 27.1 ± 4.9 (26.0; 16.7–73.4) |

| Pain duration, days; mean ± SD (median; range) | 1,050.8 ± 707.0 (969; 124–2,827) |

| Patients with pain duration ≥1 year, n (%) | 720 (62.9) |

| Number of physicians involved, mean ± SD (median; range) | 8.6 ± 1.4 (9; 3–13) |

| Previous pharmacological pain treatments: | |

| Previous pharmacological pain treatments, mean ± SD (median; range) | 7.9 ± 2.3 (8; 2–16) |

| Patients with ≥5 pharmacological pretreatments, n (%) | 1,075 (93.9) |

| Pharmacological treatment with … | |

| Non-opioid analgesics, n (%) | 833 (72.8) |

| NSAIDs, n (%) | 914 (79.8) |

| Mild opioids, n (%) | 890 (77.7) |

| Strong potent opioids, n (%) | 848 (74.1) |

| Antidepressants, n (%) | 1057 (92.3) |

| Anticonvulsants, n (%) | 782 (68.3) |

| Current pharmacological pain treatments: | |

| Current pharmacological pain treatments, mean ± SD (median; range) | 4.0 ± 1.6 (4; 1–10) |

| Patients with ≥2 pharmacological pretreatments, n (%) | 1,110 (96.9) |

| Pharmacological treatment with … | |

| Non-opioid analgesics, n (%) | 209 (18.3) |

| NSAIDs, n (%) | 122 (10.7) |

| Mild opioids, n (%) | 203 (17.7) |

| Strong potent opioids, n (%) | 747 (65.2) |

| Antidepressants, n (%) | 1,018 (88.9) |

| Anticonvulsants, n (%) | 755 (65.9) |

| Previous nonpharmacological pain treatments: | |

| Previous nonpharmacological pain treatments, mean ± SD (median; range) | 6.1 ± 1.3 (6; 2–9) |

| Patients with ≥5 nonpharmacological pretreatments, n (%) | 1,007 (87.9) |

| Nonpharmacological treatment with … | |

| Physiotherapy, n (%) | 895 (78.2) |

| Massage, n (%) | 920 (80.3) |

| Physical measures, n (%) | 753 (65.8) |

| Transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation, n (%) | 923 (80.6) |

| Acupuncture, n (%) | 897 (78.3) |

| Chiropractic measures, n (%) | 674 (58.9) |

| Psychotherapy, n (%) | 858 (74.9) |

| Cognitive behavioral treatment, n (%) | 230 (20.1) |

| Others, n (%) | 781 (68.2) |

| Concomitant diseases: | |

| Concomitant diseases, mean ± SD (median; range) | 3.5 ± 1.9 (3; 0–12) |

| Patients with ≥3 concomitant diseases, n (%) | 779 (68) |

| Patients with diseases relating to … | |

| Cancer, n (%) | 235 (20.5) |

| Nervous system, n (%) | 248 (21.7) |

| Cardiovascular system, n (%) | 467 (40.8) |

| Pulmonary system, n (%) | 292 (25.5) |

| Gastrointestinal tract, n (%) | 269 (23.5) |

| Liver, bile, pancreas, n (%) | 122 (10.7) |

| Renal system, n (%) | 195 (17) |

| Metabolic system, n (%) | 205 (17.9) |

| Skin, n (%) | 189 (16.5) |

| Musculoskeletal system, n (%) | 406 (35.5) |

| Immune system, n (%) | 42 (3.7) |

| Blood/coagulation, n (%) | 98 (8.6) |

| Mental/psychiatric problems, n (%) | 417 (36.4) |

| Allergies, n (%) | 545 (47.6) |

| Others, n (%) | 250 (21.8) |

| None, n (%) | 3 (0.3) |

| Pharmacological non-pain treatments: | |

| Pharmacological non-pain treatments, mean ± SD (median; range) | 2.0 ± 1.4 (2; 0–8) |

| Patients with ≥2 pharmacological non-pain treatments, n (%) | 673 (58.8) |

| Patients without any non-pain treatments, n (%) | 118 (10.3) |

| Primary reason for DRO treatment: | |

| Cancer pain, n (%) | 235 (20.5) |

| Post-cancer pain, n (%) | 144 (12.6) |

| Noncancer pain, n (%) | 766 (66.9) |

| Pain type: | |

| Joint pain, n (%) | 226 (19.7) |

| (Low) back pain, n (%) | 248 (21.7) |

| Shoulder/neck pain, n (%) | 113 (9.9) |

| Failed back surgery syndrome, n (%) | 141 (12.3) |

| Peripheral neuropathic pain, n (%) | 395 (34.5) |

| Central neuropathic pain, n (%) | 115 (10) |

| Complex regional pain syndrome, n (%) | 127 (11.1) |

| Headache, n (%) | 110 (9.6) |

| Fibromyalgia / chronic widespread pain, n (%) | 195 (17) |

| Lumbar spinal stenosis, n (%) | 97 (8.5) |

| Phantom/limb pain, n (%) | 82 (7.2) |

| Others, n (%) | 179 (15.6) |

SD = standard deviation.

On average, patients recorded 3.5 ± 1.9 concomitant diseases (median: 3, range: 0–12), including allergies (47.6%) and cardiovascular problems (40.8%). Patients took on average 2.0 ± 1.4 pharmacological non–pain management treatments (median: 2, range: 0–8), and 58.8% of patients documented the concurrent use of at least two pharmacological non–pain management treatments, whereas only 10.3% took none.

The primary reasons for treatment with DRO were chronic nonmalignant pain conditions (66.9%), current cancer pain (20.5%), and post-cancer pain (12.6%). The spectrum of pain types underlying CP was broad and included peripheral neuropathic pain (34.5%), low back pain (21.7%), joint pain (19.7%), and fibromyalgia / chronic widespread pain (17.0%), to list a few. Additional patient baseline characteristics and different pain etiologies and response rates can be found in the Supplementary Data (Tables 1B, 5A, and 5B).

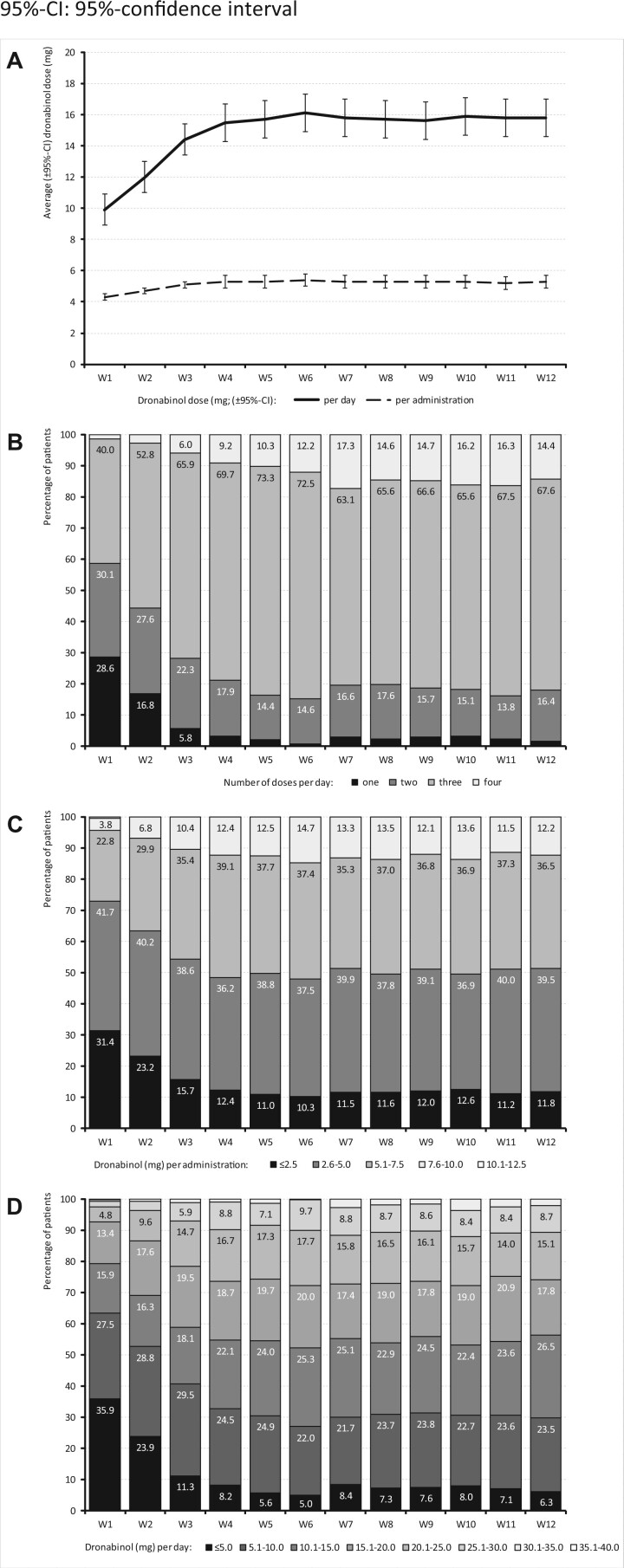

Dose Exposure and Titration

Patients started DRO treatment as an add-on to other ongoing analgesic medications with a mean dose of 2.5 ± 0.87 mg per day (median: 2.5, range: 1–5), given in two separate applications per day and titrated slowly upward until they reached a plateau at the end of week 5, with a cumulative daily dose of 16.1 ± 7.1 mg per day (median: 15.0, range: 1–32.5) that remained constant until the end of the evaluation period (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

DRO dose (mg) reported for the 12-week evaluation period.

Treatment Response

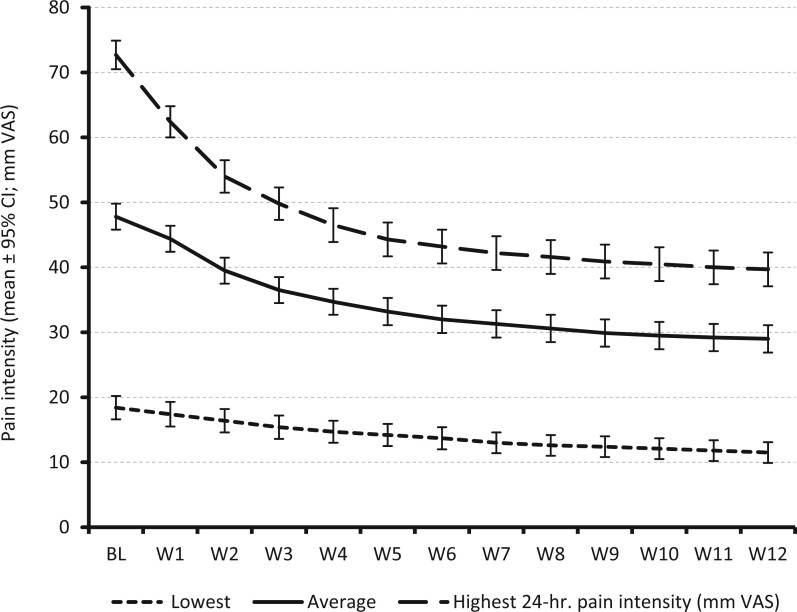

Pain Intensity

Add-on treatment with DRO was followed by significant reductions in pain intensity (see Figure 3). Table 2 shows that average 24-hour pain intensities improved from 46.3 ± 16.1 mm VAS (median: 48.0) at baseline to 26.8 ± 18.7 mm VAS (median: 23.0) at the end of week 12 (P < 0.001), corresponding to an absolute improvement of –19.5 ± 17.3 mm VAS (median: –19.3). This represents a 42.1 ± 40.2% decline from baseline. Nine hundred and ninety-four patients (86.8%) documented an improvement in pain vs. baseline, with 12 patients (1.0%) reporting no pain intensity change and 139 (12.1%) a minor PIX worsening of 9.7 ± 9.6 mm VAS. The proportions of patients who reported at week 12 an absolute improvement equal to or even greater than the minimal clinical important difference (MCID; 20 mm VAS) and of patients who reported at week 12 a relative improvement ≥50% vs. baseline were 50.0% (n = 573) and 46.5% (n = 532), respectively. The percentage of patients who reached their predefined tailored treatment target with DRO was 54.4% (n = 623).

Figure 3.

Pain intensity (lowest, average, and highest) 24 hours from baseline (BL) until the end of week 12.

Table 2.

Treatment effects between baseline and the end of the 12-week evaluation period with DRO

| Baseline | Week 12 | |

|---|---|---|

| Average 24-hour PIX, mm VAS; mean ± SD | 46.3 ± 16.1 | 26.8 ± 18.7 |

| Absolute change vs. baseline, mm VAS; mean ± SD (median) | –19.5 ± 17.3 (–19.3) | |

| Relative change vs. baseline, percent; mean ± SD (median) | –42.1 ± 40.2 (–46.4) | |

| Patients with absolute improvement ≥MCID vs. baseline, n (%) | 573 | (50) |

| Patients with relative improvement ≥50% vs. baseline, n (%) | 532 | (46.5) |

| Patients who reached their tailored treatment target at end of week 12, n (%) | 623 | (54.4) |

| Significance | P < 0.001 | |

| Pain phenomenology, PDQ7, NRS35; mean ± SD | 17.6 ± 5.7 | 14.2 ± 7.1 |

| Absolute change vs. baseline, NRS35; mean ± SD (median) | –3.4 ± 6.3 (–3.0) | |

| Relative change vs. baseline, percent; mean ± SD (median) | –19.3 ± 35.9 (–20.0) | |

| Patients with absolute improvement ≥MCID vs. baseline, n (%) | 276 | (24.1) |

| Patients with relative improvement ≥50% vs. baseline, n (%) | 232 | (20.3) |

| Significance | P < 0.001 | |

| Pain-related disabilities in daily life, mPDI1-7, mm VAS; mean ± SD | 64.9 ± 18.0 | 37.7 ± 20.5 |

| Absolute change vs. baseline, mm VAS; mean ± SD (median) | –27.2 ± 21.3 (–25.7) | |

| Relative change vs. baseline, percent; mean ± SD (median) | –41.9 ± 34.3 (–40.4) | |

| Patients with absolute improvement ≥MCID vs. baseline, n (%) | 738 | (64.5) |

| Patients with relative improvement ≥50% vs. baseline, n (%) | 446 | (39) |

| Significance | P < 0.001 | |

| Pain-related sleep problems, mPDI6, mm VAS; mean ± SD | 64.2 ± 24.2 | 42.1 ± 25.9 |

| Absolute change vs. baseline, mm VAS; mean ± SD (median) | –22.1 ± 27.8 (–19.0) | |

| Relative change vs. baseline, percent; mean ± SD (median) | –34.4 ± 50.6 (–32.3) | |

| Patients with absolute improvement ≥MCID vs. baseline, n (%) | 564 | (49.3) |

| Patients with relative improvement ≥50% vs. baseline, n (%) | 404 | (35.3) |

| Significance | P < 0.001 | |

| Physical QoL, SF-12 PCS; mean ± SD | 35.3 ± 6.8 | 43.5 ± 12.3 |

| Absolute change vs. baseline, mean ± SD (median) | 8.2 ± 14.3 (6.0) | |

| Relative change vs. baseline, percent; mean ± SD (median) | 23.2 ± 47.6 (17.2) | |

| Patients with absolute improvement ≥MCID vs. baseline, n (%) | 644 | (56.2) |

| Patients with relative improvement ≥50% vs. baseline, n (%) | 311 | (27.2) |

| Significance | P < 0.001 | |

| Mental QoL, SF-12 MCS; mean ± SD | 43.7 ± 12.1 | 45.9 ± 12.6 |

| Absolute change vs. baseline, mean ± SD (median) | 2.2 ± 10.9 (–1.0) | |

| Relative change vs. baseline, percent; mean ± SD (median) | 5.0 ± 30.6 (–2.0) | |

| Patients with absolute improvement ≥MCID vs. baseline, n (%) | 380 | (33.2) |

| Patients with relative improvement ≥50% vs. baseline, n (%) | 127 | (11.1) |

| Significance | P < 0.001 | |

| Overall well-being, MQHHF, NRS5; mean ± SD | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 2.6 ± 1.3 |

| Absolute change vs. baseline, NRS5; mean ± SD (median) | 1.0 ± 1.3 (1) | |

| Relative change vs. baseline, percent; mean ± SD (median) | 29.4 ± 59.1 (26.3) | |

| Patients with absolute improvement ≥MCID vs. baseline, n (%) | 550 | (48) |

| Patients with relative improvement ≥50% vs. baseline, n (%) | 321 | (28) |

| Significance | P < 0.001 | |

| QoL impairment by pain, QLIP, NRS40; mean ± SD | 17.4 ± 5.9 | 25.6 ± 6.3 |

| Absolute change vs. baseline, NRS40; mean ± SD (median) | 8.2 ± 5.7 (8) | |

| Relative change vs. baseline, percent; mean ± SD (median) | 36.3 ± 22.3 (36.4) | |

| Patients with absolute improvement ≥MCID vs. baseline, n (%) | 501 | (43.8) |

| Patients with relative improvement ≥50% vs. baseline, n (%) | 360 | (31.4) |

| Significance | P < 0.001 | |

SD = standard deviation; NRS= numerical rating scale.

Pain Phenomenology

The degree of DRO-related change of the clinical pain phenomenology was mild but statistically significant (see Table 2). Pain phenomenology (assessed with the Pain Detect Questionnaire, PDQ7) changed from 17.6 ± 5.7 at baseline to 14.2 ± 7.1 at end of week 12, corresponding to absolute and relative changes of –3.4 ± 6.3 points and−19.3 ± 35.9%, respectively (P < 0.001).

Pain-Related Disabilities of Daily Life Activities and Sleep

Treatment with DRO was followed by significant improvements in pain-related disabilities of daily life activities and in sleep (see Table 2). The mPDI score decreased from baseline to the end of week 12 from 64.9 ± 18.0 to 37.7 ± 20.5 mm VAS, corresponding to absolute and relative improvements of 27.7 ± 21.3 mm VAS (median: –25.7) and –41.9 ± 34.4% (median: −40.4%), respectively (P < 0.001).

The mPDI subscore #6 (sleep quality) improved from 64.2 ± 24.2 mm VAS at baseline to 42.1 ± 25.9 mm VAS at the end of week 12 (P < 0.001).

Quality of Life

Consistent with the documented responses of pain and pain-related disabilities in daily life, the physical and mental QoL scores of the SF-12 also improved (see Table 2). Average SF-12 PCS/MCS scores increased from 35.3 ± 6.8 / 43.7 ± 12.1 at baseline to 43.5 ± 12.3 / 45.9 ± 12.6 at the end of week 12, corresponding to 56.2% / 33.2% of patients (n = 644/380) with an absolute improvement greater than or equal to the MCID and 27.2% / 11.1% of patients (n = 311/127) with a relative improvement ≥50% vs. baseline (P < 0.001).

Overall Well-Being

On the basis of the MQHHF, the 12-week treatment with DRO was followed by a significant improvement vs. baseline (see Table 2). MQHHF scores increased from 1.6 ± 0.9 at baseline to 2.6 ± 1.3 at the end of week 12, and the percentages of patients who documented an improvement greater than or equal to the MCID and of patients who documented an improvement ≥50% vs. baseline at the end of the evaluation period were 48.0% and 28.0%, respectively (n = 550 and 321, respectively; P < 0.001).

QoL Impairment by Pain

Average QLIP scores increased from 17.4 ± 5.9 at baseline to 25.6 ± 6.3 at end of week 12. Absolute and relative improvements were 8.2 ± 5.7 points (median: 8) and 36.3 ± 22.3% (median 36.4%), respectively, vs. baseline (P < 0.001). Proportions of patients with QLIP improvements greater than or equal to the MCID and of patients with improvements of ≥50% vs. baseline were 43.8% and 31.4%, respectively (n = 501 and 360; P < 0.001) (see Table 2).

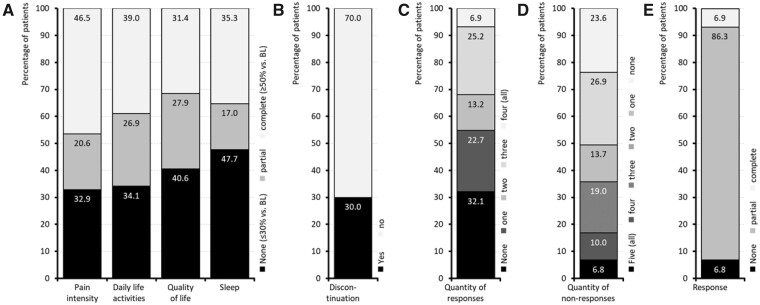

Primary Effectiveness Endpoint

A relative improvement of ≥50% vs. baseline (the given definition for a complete response) was documented by 46.5% of patients for pain intensity, 39.0% for pain-related disabilities in daily life, 31.4% for QoL impairment by pain, and 35.3% for sleep (Figure 4). A partial response (i.e., an improvement greater than 30% but less than 50% at the end of week 12 vs. baseline) was reported in these same categories by 20.6%, 26.9%, 27.9%, and 17.0% of patients, respectively, and 344 patients (30.0%) discontinued DRO treatment prematurely (because of insufficient effectiveness or tolerability issues). On the basis of these data, 79 patients (6.9%) reached the primary endpoint and documented a complete response (defined as a relative improvement ≥50% vs. baseline) for all four efficacy endpoints, 86.3% of patients (n = 988) documented a partial response (i.e., a relative improvement ≥50% vs. baseline for at least one efficacy endpoint), and 6.8% (n = 78) were classified as nonresponders.

Figure 4.

Primary endpoint/responder analysis.

Dose–Response

A dose–response analysis based on the daily DRO dose at the end of week 12 and the reported relative (percent) relief with respect to the average 24-hour PIX failed to show a clinically relevant relationship (see Supplementary Data Figure 5). Despite a trend toward numerically higher percent improvements with higher DRO doses, correlation analyses failed to prove a statistically relevant correlation (R2 = 0.0035).

Concomitant Analgesic Medication

Add-on treatment with DRO was followed by a significant decrease in analgesic medications (see Table 3). The average ± standard deviation (median) number of analgesic and co-analgesic medications used at baseline vs. the end of week 12 decreased from 4.0 ± 1.6 (median: 4) to 2.9 ± 1.7 (median: 3; P < 0.001). One quarter (25%) of patients stopped concomitant use of analgesics medications known to be associated with significant risks of either organ failure (e.g., NSAIDs) or addiction (e.g., opioid analgesics).

Table 3.

Change in pain medication between baseline and the end of the 12-week evaluation period with DRO

| Baseline |

Week 12 |

Δ (W12→BL) |

Signif. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of analgesics, mean ± SD (median) | 4.0 ± 1.6 (4) |

2.9 ± 1.7 (3) |

–1.1 ± 1.4 (–1) |

P < 0.001 |

| Analgesic treatment with … | ||||

| Non-opioid analgesics/nsaids, n (%) | 311 (27.2) | 227 (19.8) | –84 (–27) | P < 0.001 |

| Mild opioid analgesics, n (%) | 203 (17.7) | 150 (13.1) | –53 (–26.1) | P < 0.001 |

| Strong opioid analgesics, n (%) | 747 (65.2) | 570 (49.8) | –177 (–23.7) | P < 0.001 |

| Antidepressants, n (%) | 1018 (88.9) | 849 (74.1) | –169 (–16.6) | P < 0.001 |

| Anticonvulsants, n (%) | 755 (65.9) | 569 (49.7) | –186 (–24.6) | P < 0.001 |

| None, n (%) | 0 (0) | 89 (7.8) | 89 (na) | P < 0.001 |

| Patients … | ||||

| Without pain medication change after DRO, n (%) | 559 (48.8) | |||

| With termination of ≥1 pain medication with DRO, n (%) | 586 (51.2) | |||

| With termination of any pain medication beyond DRO, n (%) | 89 (7.8) | |||

| Demand of analgesics: | ||||

| None, n (%) | 0 (0) | 89 (7.8) | 89 (na) | P < 0.001 |

| 1–2, n (%) | 209 (18.3) | 421 (36.8) | 212 (101.4) | |

| 3–4, n (%) | 547 (47.8) | 441 (38.5) | –106 (–19.4) | |

| ≥5, n (%) | 389 (34) | 194 (16.9) | –195 (–50.1) |

SD = standard deviation; na = not applicable.

Safety and Tolerability Analyses

Overall, DRO was well tolerated. We found no evidence of abuse, deliberate overdose, or intentional misuse in the 1,145 cases evaluated. Furthermore, no patient died within the 12-week evaluation period. As shown in Table 4, 46.8% of patients (n = 536) documented at least one DRAE, and 29.2% (n = 334) documented two or more DRAEs. The most prevalent DRAE was ineffectiveness (22.4%), followed by dizziness (14.7%) and somnolence (13.8%). DRAEs were associated predominantly with general disorders and administration site conditions (26.7%), psychiatric problems (25.5%), and nervous system disorders (24.8%). Most DRAEs were mild to moderate (52.3/32.3%) and recovered completely (81.7%)—in 54.4% without specific countermeasures. Psychiatric DRAEs associated with DRO, such as anxiety (2.4%), confusion (3.0%), dissociation (0.8%), hallucination (1.6%), delusion (1.0%), paranoia (0.8%), and suicidal ideation (0.9%), were rare, but such DRAEs affected in total 107 patients (9.3%), of whom 76 (71.0%) discontinued DRO treatment.

Table 4.

Patients and organ classes affected by DRAEs

| Organ classes affected and DRAE prevalence | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Total number of DRAEs: | 1,617 (100) |

| Cardiac disorders | 31 (1.9) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 152 (9.4) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 432 (26.7) |

| Injury, poisoning, and procedural complications | 14 (0.9) |

| Investigations | 33 (2) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 64 (4) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 34 (2.1) |

| Nervous system disorders | 401 (24.8) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 412 (25.5) |

| Vascular disorders | 44 (2.7) |

| DRAEs with a prevalence ≥2%: | |

| Ineffectiveness | 257 (22.4) |

| Dizziness | 168 (14.7) |

| Somnolence | 158 (13.8) |

| Fatigue | 92 (8) |

| Memory impairment | 71 (6.2) |

| Nausea | 71 (6.2) |

| Dry mouth | 58 (5.1) |

| Increased appetite | 49 (4.3) |

| Balance disorder | 48 (4.2) |

| Muscular weakness | 37 (3.2) |

| Headache | 36 (3.1) |

| Confused state | 34 (3) |

| Euphoric mood | 28 (2.4) |

| Myalgia | 27 (2.4) |

| Anxiety | 27 (2.4) |

| Sleep disorder | 26 (2.3) |

| Vision blurred | 25 (2.2) |

| Tremor | 24 (2.1) |

| Psychomotor hyperactivity | 24 (2.1) |

| Total population | 1,145 (100) |

| Patients with DRAEs: | |

| Patients with at least one DRAE | 536 (46.8) |

| Patients with ≥2 DRAEs | 334 (29.2) |

| Patients affected by … | |

| Cardiac disorders | 31 (2.7) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 132 (11.5) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 374 (32.7) |

| Injury, poisoning, and procedural complications | 14 (1.2) |

| Investigations | 33 (2.9) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 64 (5.6) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 34 (3) |

| Nervous system disorders | 263 (23) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 267 (23.3) |

| Vascular disorders | 42 (3.7) |

| Patients with … | |

| Treatment discontinuations for any reasons | 344 (30) |

| DRAE-related treatment discontinuations | 161 (14.1) |

| Efficacy-related treatment discontinuations | 96 (8.4) |

| Discontinuation due to a combination of both | 87 (7.6) |

Discussion

DRO is a “last-resort” medication prescribed for patients with refractory CP or in end-stage palliative care situations in many countries around the world. This exploratory retrospective 12-week analysis evaluated the effectiveness of DRO in 1,145 patients with severe refractory CP with average pain durations of 2.9 years, average daily pain intensities of 46.3 mm VAS, daily peak pain intensities of up to 72.7 mm VAS, and significant restrictions in physical and mental health despite combination treatment with opioid and non-opioid analgesics and adjuvant co-therapeutics. Treatment with DRO was followed by significant and clinically relevant symptom relief in all dimensions evaluated.

In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in patients with neuropathic pain due to multiple sclerosis, clinically relevant pain reduction was observed (on an 11-point numerical rating scale), but no statistical significance was observed between the DRO group and the placebo group [34]. The clinical relevance of the observed effects associated with the add-on administration of low-dose DRO in our study is underlined by the fact that 1) all patients evaluated in the present analysis failed to respond to recommended and approved first-, second-, and third-line treatments and subsequently suffered from severe CP-related restrictions, 2) more than half of the patients evaluated were able to reduce their analgesic baseline medication, and 3) the majority of DRAEs were reported as mild or moderate, were transient, and showed a complete recovery without specific countermeasures.

Effective DRO dosages were low (∼15 mg/day) and were taken by patients in ∼3 separate single doses (i.e., +5 mg per administration), and effective maintenance dosages were reached after a short 4-week titration period. Treatment effects observed with DRO were large enough for more than half of patients to reduce at least one pain medication, such as opioid analgesics or NSAIDs.

Our findings are consistent with those reported from other trials, and case reports suggest that DRO is well tolerated [34]. Psychiatric DRAEs affected 9.3% of patients in our study (of whom the majority discontinued treatment and recovered completely), which we consider an important observation for clinical practice. Patients with known risk factors for the development of these DRAEs should be continuously monitored, and treatment with DRO, as well as other types of tetrahydrocannabinol-containing cannabis as medicine, should be initiated and maintained with caution.

Dose–response analyses revealed no correlation between distinct daily dosages or dosage ranges and specific response rates—an observation that might be the consequence of our noninterventional study design and the limited experience with DRO as pain medication. As a consequence, our results could underestimate the therapeutic potential, because of low dosing for some patients and early discontinuation in cases of ineffectiveness (of too low doses) or (probably transient) undesired effects at the beginning of the therapy.

Strengths and Limitations

The most obvious limitation is the lack of a control (active or placebo) group, which allows no differentiation between effects that are related directly to the treatment under evaluation and those related to other unrecognized, and uncontrolled, factors. This limits the attribution of causality between DRO treatment and the effects observed. Real-world evidence could, however, complement trial data and build the basis for the development of further RCTs, help to implement new treatments in routine care, and correct sometimes misleading results of nonrepresentative or artificial data samples used in RCTs. In addition, retrospective analyses of real-life data gathered during routine patient care can help in understanding how RCTs should be designed and what kind of response could be expected.

Another limitation is associated with the fact that entering data into the GPeR requires the active participation of physicians and pain treatment centers and the implementation of the online documentation service iDocLive® as part of daily routine care, which raises the potential for selection bias. However, the 212 centers within the GPeR network and its 768 pain specialists, 795 physicians, and 2,548 nonmedical specialists represent the whole spectrum of medical and associated disciplines involved in pain management, and they are homogenously distributed within Germany, representing about 25% of all pain centers in the country, with different sizes and settings (urban and rural), thus minimizing the risk of geographic or other systemic patient selection biases. All participants were board-certified pain specialists, well experienced with pharmacological and nonpharmacological measures and their differential use in patients with CP. This special qualification is probably the reason for the extensive data collection and the high proportion of scales used and should be kept in mind when DRO treatment strategies are adopted by less experienced physicians.

A further potential limitation of this analysis is the inclusion of multiple CP etiologies, which resulted in considerable data heterogeneity. However, the available data for distinct subgroups of patients with different pain types are large enough for a differential analysis, which is scheduled for the near future.

Because of the methodological restrictions and our focus on depersonalized routine-care data, we were able to perform neither a systematic monitoring of treatment compliance nor a formal recording of possible DRO misuse or treatment abuse. However, the evaluated study medication is known to have a low risk of misuse and abuse, especially if compared with inhaled cannabinoids or traditional World Health Organization (WHO) Step III analgesics. In fact, we found no signals of any unexpected or serious adverse events associated with the use of DRO in our population.

With respect to the long-lasting history of refractory CP reported by the patients in this analysis, a 12-week evaluation period is too short to draw conclusions on the long-term effectiveness and safety of DRO for this indication. Significantly longer treatment observations are necessary to confirm the endurance of the effects seen in our cohort of patients, as well as the ability of DRO to reduce or even replace alternative pain treatments. Additionally, RCTs are necessary to substantiate our results and to further increase our knowledge about the advantages and disadvantages of a treatment with DRO in patients with CP. However, the present study is, to our knowledge, the largest study on DRO in the patient population with CP so far, and it delivers important information on the differential effects seen with DRO in daily practice.

Finally, neither the physicians nor the patients received any type of compensation for their data collection activities. All information recorded and transferred into the registry were entered to improve the patient–physician interaction—two factors eliminating any data entries motivated by financial incentive or other external influences.

Conclusions

This exploratory analysis provides real-world insights on 1,145 patients with refractory severe CP provided by the GPeR, in whom add-on treatment with DRO was followed by a significant improvement in pain intensity, pain-related disabilities in daily life, QoL, and sleep. However, because of limitations in the study design, we cannot advance conclusions as to the causes of the effects observed here, and these data should be viewed as preliminary evidence. On the basis of our findings, it appears that treatment with DRO was well tolerated across the study cohort. The majority of DRAEs were mild to moderate, and complete recovery without specific countermeasures was frequent. No evidence of abuse, persistent patterns of deliberate overdose, misuse, or tolerance development was observed. Psychiatric DRAEs were reported by 9.3% of patients and recovered after treatment discontinuation. Treatment with DRO was followed by a significant reduction of concomitant pain medications known to be associated with significant risk of organ failure (e.g., NSAIDs) or addiction (e.g., opioid analgesics). Further randomized trials with an active control group are needed to determine the clinical efficacy and validate the DRAE findings.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript to be published. MAU takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to the finished article.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Data may be found online at http://painmedicine.oxfordjournals.org.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Michael A Ueberall, Center of Excellence in Health Care Research of the German Pain Association, Institute of Neurological Sciences, Nuernberg, Germany.

Johannes Horlemann, German Pain Association, Berlin, Germany.

Norbert Schuermann, Department for Pain and Palliative Care Medicine, St. Josef Hospital Moers, Moers, Germany.

Maja Kalaba, Canopy Growth Corporation, Smiths Falls, Ontario, Canada.

Mark A Ware, Canopy Growth Corporation, Smiths Falls, Ontario, Canada.

Funding sources: The concept for this evaluation of routine data provided by the German Pain e-Registry was developed by MAU at the Institute of Neurological Sciences (IFNAP) on behalf of the German Pain Association (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Schmerzmedizin, DGS) and the German Pain League (Deutsche Schmerzliga [DSL]), and its realization has been funded by an unrestricted scientific grant from Canopy Growth Corporation. Neither Canopy Growth nor any of its employees exerted any influence on the data acquisition, the conduct of this analysis, or the interpretation and publication of the results. The German Pain e-Registry is hosted by an independent contract research organization by order of the German Pain Association and under control of the Institute of Neurological Sciences and has collected standardized real-world data from daily routine medical care since January 2000.

Disclosures and conflicts of interest: MAU, JH, and NS are physicians and independent of any significant/relevant financial or other relationship to the sponsor, except for minor reimbursements for occasional lecture or consulting fees. All are honorary members of the management board of the German Pain Association. MAU is also an honorary member of the management of the German Pain League. MK and MAW are employees of Canopy Growth Corporation.

MAU received financial support and/or expenses in form of research money, consultancy fees, and/or renumerations for lecture activities from Allergan, Almirall, Amicus Therapeutics, Aristo Pharma, Bionorica, Glaxo Smith Kline, Grünenthal, Hapa medical, Hexal, IMC, Kyowa-Kirin, Labatec, Mucos, Mundipharma, Nestle, Pfizer, Recordati, Servier, SGP-Pharma, Shionoghi, Spectrum Therapeutics, Teva, and Tilray. JH received financial support, consultancy fees, and/or renumerations for lecture activities from Amgen, AOP Orphan, Aristo Pharma, Glaxo Smith Kline, Grünenthal, Janssen-Cilag, Kyowa-Kirin, Spectrum Therapeutics, and Tilray. NS received financial support, consultancy fees, and/or renumerations for lecture activities from AOP Orphan, Archimedes, Aristo Pharma, Grünenthal, Hexal, Janssen-Cilag, Kyowa-Kirin, Mundipharma, MSD, Pfizer, Spectrum Therapeutics, Teva, and Tilray. MK and MAW are employees of Canopy Growth Corporation.

Study registration: European Union Electronic Register of Post-Authorisation Studies (EU PAS) #35350.

Prior publication: Preliminary results of this analysis have been presented at the annual online Congress of the German Pain Association, July 21–25, 2020, Germany.

References

- 1. Bonica JJ. The Management of Pain. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Treede RD. Entstehung der Schmerzchronifizierung [Development of pain chronification]. In: Baron R, Koppert W, Strumpf M, Willweber-Strumpf A, eds. Praktische Schmerztherapie. Heidelberg: Springer; 2011: 3–13. German. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Merskey H, Bogduk N.. Classification of Chronic Pain. 2nd edition.Seattle: IASP Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D.. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: Prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006;10(4):287–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goldberg DS, Summer JM.. Pain as a global public health priority. BMC Public Health 2011;11:770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gureje O, von Korff M, Kola L, et al. The relation between multiple pains and mental disorders: Results from the World Mental Health Surveys. Pain 2008;135(1–2):82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koleva D, Krulichova I, Bertolini G, Caimi V, Garattini L.. Pain in primary care: An Italian survey. Eur J Public Health 2005;15(5):475–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mäntyselkä P, Kumpusalo E, Ahonen R, et al. Pain as a reason to visit the doctor: A study in Finnish primary health care. Pain 2001;89(2-3):175–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Phillips CJ. Economic burden of chronic pain. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2006;6(5):591–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Balderson BH, et al. Comparison of complementary and alternative medicine with conventional mind-body therapies for chronic back pain: Protocol for the Mind-body Approaches to Pain (MAP) randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014;15:211–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee C, Crawford C, Buckenmaier C, et al. Active, self-care complementary and integrative medicine therapies for the management of chronic pain symptoms: A rapid evidence assessment of the literature. J Altern Complement Med 2014;20(5):A137–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Breen J. Transitions in the concept of chronic pain. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 2002;24(4):48–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Backonja M, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: Evidence based recommendations. Pain 2007;132(3):237–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moulin DE, Clark AJ, Gilron I, et al. ; Canadian Pain Society. Pharmacological management of chronic neuropathic pain consensus statement and guidelines from the Canadian Pain Society. Pain Res Manage 2007;12(1):13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jensen TS, Madsen CS, Finnerup NB.. Pharmacology, and treatment of neuropathic pains. Curr Opin Neurol 2009;22(5):467–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. O'Connor AB, Dworkin RH.. Treatment of neuropathic pain: An overview of recent guidelines. Am J Med 2009;122(suppl 10):S22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Attal N, Cruccu G, Baron R, et al. EFNS guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain: 2010 revision. Eur J Neurol 2010;17(9):1113-e88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dworkin RH, O'Connor AB, Audette J, et al. Recommendations for the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain: An overview and literature update. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85(suppl 3):S3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mu A, Weinberg E, Moulin DE, Clarke H.. Pharmacologic management of chronic neuropathic pain: Review of the Canadian Pain Society consensus statement. Can Fam Physician 2017;63(11):844–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: Systematic review, meta-analysis and updated NeuPSIG recommendations. Lancet Neurol 2015;14(2):162–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;386:743–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Classification of chronic pain: Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Prepared by the International Association for the Study of Pain, Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain 1986;3(suppl):S1–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gesetz Zur Änderung Betäubungsmittelrechtlicher Und Anderer Vorschriften. Bundesgesetzblatt 2017; 1/11. Available at: https://www.bgbl.de/xaver/bgbl/start.xav?start=%2F%2F%5B%40attr_id%3D%27bgbl117s0403.pdf%27%5D#__bgbl__%2F%2F%5B%40attr_id%3D%27bgbl117s0403.pdf%27%5D__1537108060099 (accessed February 15, 2021).

- 24. Häuser W, Finnerup NB, Moore RA.. Systematic reviews with meta-analysis on cannabis-based medicines for chronic pain: A methodological and political minefield. Pain 2018;159(10):1906–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Allan GM, Finley CR, Ton J, et al. Systematic review of systematic reviews for medical cannabinoids: Pain, nausea and vomiting, spasticity, and harms. Can Fam Physician 2018;64(2):e78–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stockings E, Campbell G, Hall WD, et al. Cannabis and cannabinoids for the treatment of people with chronic noncancer pain conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled and observational studies. Pain 2018;159(10):1932–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kalaba M, MacNair L, Peters EN, et al. Authorization patterns safety, and effectiveness of medical cannabis in Quebec. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res 2021;6(6):564–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deutsche Schmerzgesellschaft. Deutscher Schmerzfragebogen [German pain questionnaire]. Available at: http://www.dgss.org/deutscher-schmerzfragebogen (accessed February 15, 2021). German.

- 29.Deutsche Schmerzgesellschaft. Handbuch zum Deutschen Schmerzfragebogen [Manual for the German pain questionnaire]. Available at: http://www.dgss.org/fileadmin/pdf/12_DSF_Manual_2012.2.pdf (accessed February 15, 2021). German.

- 30. Tait RC, Chibnall JT, Krause S.. The pain disability index: Psychometric properties. Pain 1990;40(2):171–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Casser HR, Hüppe M, Kohlmann T, et al. Deutscher Schmerzfragebogen (DSF) und standardisierte Dokumentation mit KEDOQ-Schmerz [German pain questionnaire and standardised documentation with the KEDOQ-Schmerz]. Der Schmerz 2012;26(2):168–75. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hayes CJ, Bhandari NR, Kathe N, Payakachat N.. Reliability, and validity of the medical outcomes study short form-12 version 2 (SF-12v2) in Adults with Non-Cancer Pain. Healthcare (Basel) 2017;5(2):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Basler HD. Marburger Fragebogen zum habituellen Wohlbefinden—Untersuchung an Patienten mit chonischem Schmerz [The Marburg questionnaire on habitual health findings—A study on patients with chronic pain]. Schmerz 1999;13(6):385–91. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schimrigk S, Marziniak M, Neubauer C, et al. Dronabinol is a safe long-term treatment option for neuropathic pain patients. Eur Neurol 2017;78(5-6):320–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.