Abstract

We propose a perspective based on the individualism versus collectivism (IC) cultural distinction to understand the diverging early-stage transmission outcomes of COVID-19 between countries. Since individualism values personal freedom, people in such cultures would be less likely to make the collective action of staying at home and less likely to support compulsory measures. As a reaction to the public will, governments of individualistic societies would be more hesitant to take compulsory measures, leading to the delay of necessary responses. With processed COVID-19 data that can provide a fair comparison, we find that COVID-19 spread much faster in more individualistic societies than in more collectivistic societies. We further use pronoun drop and absolute latitude as the instruments for IC to address reverse causality and omitted variable bias. The results are robust to different measures. We propose to consider the role of IC not only for understanding the current pandemic but also for thinking about future trends in the world.

Keywords: Individualism versus collectivism, COVID-19, Government response, IV-2SLS

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread all over the world since the beginning of 2020 and has been the greatest public health threat since the 1918 influenza pandemic (Ferguson et al., 2020; Greenstone & Nigam, 2020; Heymann & Shindo, 2020). In this pandemic, a striking phenomenon is the large differences in the transmission outcomes between different countries and territories. For example, countries such as China and South Korea succeeded in limiting the spread of the virus in the early stages, while many other countries (such as the UK and USA) that were considered to be much safer in the first place1 became the worst-hit areas (Cohen & Kupferschmidt, 2020; Perc et al., 2020; Brodeur et al., 2021a, 2021b). We suggest that the cultural difference between collectivism versus individualism (IC) could largely explain this divergence. In addition, the role of IC needs to be taken more seriously to understand the development of the pandemic and the future trend in the world.

First, the parasite stress theory of values (Fincher et al., 2008; Murray & Schaller, 2010; Thornhill & Fincher, 2014) suggests that the historical prevalence of infectious diseases could be an important source of the origins of IC cultural differences. According to this view, IC could be an evolutionary adaptation to the environment. Societies with a high degree of pathogenic stress were more likely to develop a collectivist culture that functions as a social defense to stop the spread of infectious diseases, while societies with low pathogenic stress developed individualistic value systems that favor inclusiveness, rights, and liberties (Fincher et al., 2008). If this is true, modern societies with highly individualistic cultures may be more vulnerable to infectious diseases than collectivistic societies. In line with this, Morand and Walther (2018) found that individualistic societies have experienced more infectious disease outbreaks and zoonotic disease outbreaks in recent times, but they did not find a correlation between IC cultural differences and emerging infectious disease events. Studying the COVID-19 pandemic would provide further insights into this fundamental problem.

Second, a large body of literature has documented that societies with greater individualism in values are more creative (Goncalo & Staw, 2006; Mungiu-Pippidi, 2015), have stronger formal institutions (Licht et al., 2007; Tabellini, 2008) and fewer rule violations (Gächter & Schulz, 2016; Mazar & Aggarwal, 2011), engage in trade more often (Hajikhameneh & Kimbrough, 2019), and have better economic growth (Gorodnichenko & Roland, 2011a, 2011b, 2017) than more collectivistic societies. We can infer that the history of infectious diseases may largely shape the current world division of prosperity and poverty. The social structures of less-developed societies evolved as behavioral immune systems to inhibit the transmission of infectious diseases but were not friendly to economic development. Suppose the COVID-19 pandemic hurts individualistic societies more than collectivistic societies and the world evolves toward building immune systems. In that case, we wonder whether the COVID-19 pandemic would reverse the world's development trajectory.

Third, studies show that individualism has increased globally and within societies over the past several decades (Santos et al., 2017). If pathogens do favor individualism, we will live in a world with a higher risk of infectious diseases (Morand & Walther, 2018). The COVID-19 pandemic could promote our reflection on our development model. It may bring retrogression of social development if we cannot better understand this event.

In the early stage of the pandemic, vaccination and effective medicines are impossible. Since the virus is transmitted from person to person, early discovery, early quarantine, and safe social distance are the keys to cutting off the transmission route (Fong et al., 2020; Hsiang et al., 2020). Thus, the natural explanation for the different transmission outcomes comes from the different nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) taken by different subpopulations. The differences in governmental policy responses may explain some of the differences. Although China promptly implemented strict social distancing tactics that were proven effective (Anderson et al., 2020; Greenstone & Nigam, 2020; Jones et al., 2020; Qiu et al., 2020), such measures were implemented more slowly in many other countries (Greenstone & Nigam, 2020). For example, Brazil's Jair Bolsonaro, Mexico's Lopez Obrador, and US President Donald Trump were all resistant to adopting any social distancing policy even in the face of rapidly growing cases in their countries (Fukuyama, 2020).

Why do the introduced measures vary widely between countries? The government action itself must reflect the collective will. A society that believes that "one should look after himself" would prefer a low level of government intervention in all areas. Thus, the difference in governmental responses could be rooted in fundamental cultural differences.

On the other hand, although the role of government action matters, individual behavior can be more crucial to control the spread of viruses (Anderson et al., 2020). First, social distancing measures cannot be enforced entirely by coercion, and their effectiveness depends on compliance by the public (Allcott et al., 2020; Briscese et al., 2020; Perc et al., 2020). For instance, it is reported that approximately 52 percent of the adult United States population went out of their homes even though public health authorities recommended social distancing (Canning et al., 2020). Second, individual and collective public behavior that determines the transmission of the virus may be affected by many factors beyond policy measures (Bauch & Galvani, 2013; Lunn et al., 2020) that vary among different subpopulations. For example, Hong Kong and Singapore's good performance in managing COVID-19 is believed to be largely attributed to the social distancing measures taken by individuals (Anderson et al., 2020). The distinct cultural differences in IC shape different original attitudes and social behaviors in the face of public health events and further shape corresponding institutional and public policies, thus having a significant effect on the early-stage transmission of COVID-19.

Since individualism values personal freedom and expects everyone to look after themselves only while not relying on the authorities, people in individualistic societies would be less likely to make the collective action of staying at home and avoiding gathering activities. They would also be less likely to accept quarantine and support compulsory measures, such as massive lockdowns. As a reaction to the public will, governments in individualistic societies would be more hesitant to take compulsory measures and delay the necessary responses. In addition, even when the government takes social distancing measures, citizens with individualistic values are more likely to disobey. Several recent papers’ findings support this view. For example, Bazzi et al. (2021) find that greater rugged individualism in the USA is associated with less social distancing and mask use and a weaker local government effort to control the virus. Lu et al. (2021) find that collectivism (versus individualism) positively predicts mask usage within the USA and across the world.

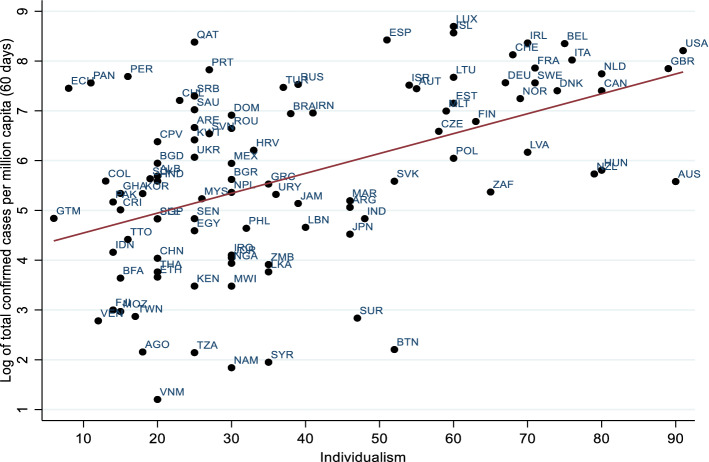

We test this cultural perspective of the transmission of COVID-19 with cross-country data based on culture measurements from Hofstede et al. (2010). We use the date at which a country's total confirmed cases per million capita reach one as the starting point of each country's outbreak and use the total confirmed cases per million capita 60 days after this starting point to measure the early-stage transmission outcome. As Fig. 1 shows, there is a positive correlation between the individualism index and the early-stage transmission outcome of COVID-19 across countries. More individualist countries tend to have more confirmed cases per million capita.

Fig. 1.

Correlation of individualism and total cases per million capita. Note: Numeric country codes based on the ISO-3166–1 standard are marked in the figure (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ISO_3166-1_numeric). The data on Individualism is taken from Hofstede et al. (2010) and https://www.hofstede-insights.com/, and the COVID-19 case data are from JHU CCSE (https://github.com/owid/covid-19-data)

Figure 1 merely displays the correlation and does not imply causality. We use pronoun drop and absolute latitude as the instruments for IC to solve reverse causality and omitted variable bias. We find a significant impact of IC cultural differences on the early-stage transmission outcome of COVID-19. The results are robust to different transmission outcomes, different measures of IC, other cultural dimensions, and different subsamples.

We contribute to the literature in several aspects. First, we provide new insight to explain the large differences in the early-stage transmission outcomes of COVID-19 between different countries and territories. Second, we provide insights into how epidemics interact with economic and social behavior and help to find out what fundamental social causes have led to different anti-epidemic performance, which also contributes to the growing literature on the social factors of infectious diseases (such as Bauch & Galvani, 2013). Third, we bring a new perspective to the rapidly developing literature on the cultural impact of social behavior, especially the studies on IC cultural differences (e.g., Gächter & Schulz, 2016).

Literature

As the main dimensions of cultural variation (Greif, 1994; Hofstede, 2001; Triandis, 1995), individualism and collectivism are constructs that summarize fundamental differences in how the relationship between individuals and societies is construed and whether individuals or groups are seen as the basic unit of analyses (for a review, see Oyserman et al., 2002). In individualistic cultures, people are viewed as independent and as possessing a unique pattern of traits that distinguish them from other people, while people in collectivistic cultures view the self as inherently interdependent with the group to which they belong (Hofstede, 1980; Markus & Kitayama, 1994).

The impact of IC on human behavior has been widely investigated in multidisciplinary literature (see Oyserman & Lee, 2008 for review). It is widely acknowledged that individualism places value on personal freedom, self-reliance, creative expression, intellectual and affective autonomy, minimal government intervention, and rewards individual accomplishments with higher social status (Nikolaev et al., 2017). However, as discussed in Gorodnichenko and Roland (2017), "individualism can make collective action more difficult because individuals pursue their own interest without internalizing collective interests… collectivism should have an advantage in coordinating production processes and in various forms of collective action."

Among the many recent studies on the transmission of COVID-19, there has been a growing interest in investigating the interaction between epidemics and social behaviors (e.g., Codagnone et al., 2021; Rieger & Wang, 2021). In addition to discussions on how to use behavioral science to help fight the virus (e.g., Lunn et al., 2020; Van Bavel et al., 2020), some related studies give special interest to the driving factors of different behavioral responses to anti-COVID-19 regulations. For example, using survey data from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany, Pfattheicher et al. (2020) find that citizens' compliance with social distancing increases empathy for vulnerable groups. However, another international survey of 324 individuals found that fear of contracting the virus was the only strong predictor of social distancing behavior (Harper et al., 2020).

Similarly, a strand of literature has paid attention to the impact of partisan differences on anti-epidemic behaviors (Allcott et al., 2020; Dyevre and Yeun, 2020; Grossman et al., 2020; Painter & Qiu, 2021). As argued by Allcott et al. (2020), political leaders and media outlets on the right and left have sent divergent messages about the severity of the crisis, which could impact the extent to which Republicans and Democrats engage in social distancing and other efforts to reduce disease transmission. Using location data from a large sample of smartphones, they find that controlling for other factors, including state policies, population density, and local COVID cases and deaths, areas with more Republicans engage in less social distancing. They further find significant gaps between Republicans and Democrats in beliefs about personal risk and the pandemic's future path with survey evidence. Similarly, Painter and Qiu (2021) find that relative to those in Democratic counties, residents in Republican counties are less likely to stay completely at home after a state order has been implemented. Since the belief gaps between the Republicans and Democrats in the USA result in divergent behavioral responses in the face of COVID-19, we have reason to believe that the large cultural differences between different counties would lead to significant behavioral differences, which finally impact the transmission outcomes of the virus.

Collectivism Versus Individualism Cultural Distinction and the Spread of COVID-19

Our measure for IC (Individualism) is from the work of Hofstede et al. (2010), which has been used extensively as the paradigm in multidisciplinary literature. Hofstede (1980) originally constructed individualism scores for 40 countries based on survey responses to fourteen "work goal" questions from 117,000 IBM employees worldwide. Hofstede and coauthors then updated the questionnaires and extended their respondents to various professions in subsequent survey waves (Hofstede et al., 2010). The underlying principle of Hofstede's measure is the relationship between an individual and society and the values and societal norms that this relationship fosters.

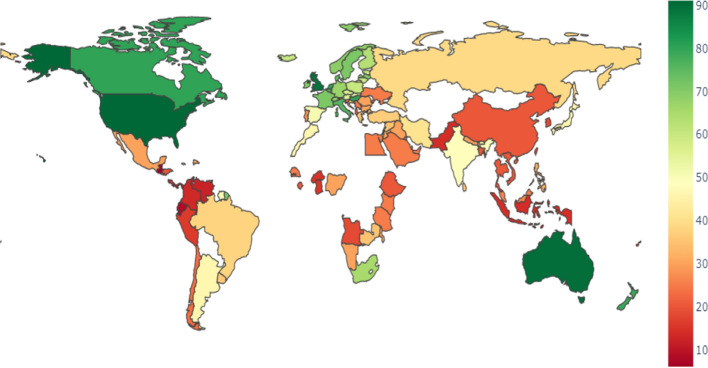

Figure 2 presents the world map of the distribution of national individualism scores for all available countries. The index 'Individualism' ranges from 0 (most collectivistic) to 100 (most individualistic) and measures how important the individual is relative to the collective in a society, with higher values indicating more individualist societies.

Fig. 2.

Collectivism versus individualism world map. Note: The figure shows the extent of individualistic culture for 101 countries. The colored tape in the right part of the figure indicates the value of the individualism index. The data are taken from Hofstede et al. (2010) and https://www.hofstede-insights.com/

According to this measure, the USA is a highly individualistic society, which is loosely knit under the expectation that people look after only themselves and their immediate family members and not rely (too much) on authorities for support. Other English language countries, including the UK, Canada, and Australia, are also highly individualistic societies. In contrast, China has a highly collectivistic culture, in which people act in accordance with their group interests and not necessarily their own interests. Society fosters strong relationships, where everyone takes responsibility for fellow members of their group. "When disaster struck, help came from all sides" is the typical response to crises in China. For example, all the other provinces in China have assisted Hubei Province in the battle with COVID-19.

Previous studies show that the more people feel part of a group or community, the more likely they will make a selfless contribution (Chaudhuri, 2011). Facing external threats, such as warfare or epidemics, people with the perspective of "we" and "us" rather than "I" or "you" are more likely to make public-spirited responses (Carter et al., 2013; Lunn et al., 2020). Since infectious diseases have the attribute of public goods in that individuals’ chances of contracting COVID-19 depend not only on their own behavior but also on their fellow citizens' behavior, the battle with COVID-19 needs coordination among all society members. When the epidemic broke out at the beginning of 2020, a nationwide collective action of staying at home was formed at once, and it lasted for more than a month in collectivist China. This large-scale collective action would be virtually infeasible without a highly collectivistic cultural root.

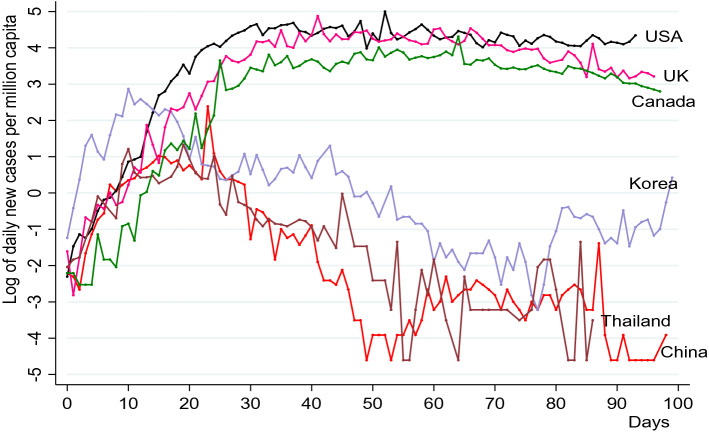

As indicated in Fig. 3, the growth rate of cases shows a sharp decrease in representative collectivistic countries, such as China, South Korea, and Thailand2 approximately 25 days after the date when daily reported cases per million capita exceeds 0.1. Consequently, the striking result is that although the COVID-19 outbreak first occurred in some Asian countries, such as China and South Korea, these countries with a highly collectivistic culture successfully stopped the spread of the epidemic. However, countries with highly individualistic cultures, represented by the UK and the USA, lost control of the disease even though they were much safer at the beginning.

Fig. 3.

Differences in the growth rates of cases in representative countries. Note: The horizontal axis indicates the days since a country's daily cases reached 0.1 per million capita, and the vertical axis indicates the log of daily new cases per million capita. The data used are taken from JHU CCSE (https://github.com/owid/covid-19-data)

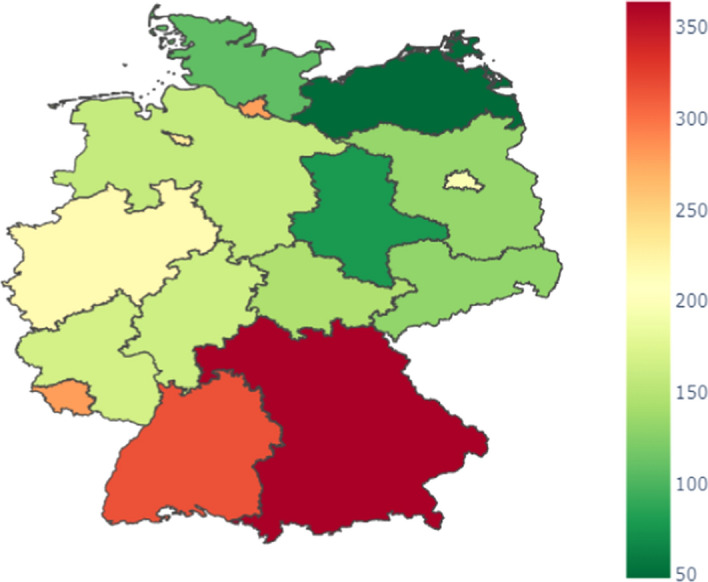

Germany's special history provides us with a natural experiment to better understand the impact of IC cultural differences. East and West Germany shared the same national culture before 1945 but were divided into two independent societies and political systems after World War II. After 1945, East Germany gradually became a communist society, and its people were increasingly exposed to collectivism. In contrast, West Germany retained its capitalistic system and developed a more individualistic culture (Vater et al., 2018). Germany again became a unified, capitalism-orientated society in 1990. As shown in Fig. 4, as of 31 May 2020, the total number of confirmed cases per million capita in former East Germany was much less than that in former West Germany. Since West and East Germany share the same political and economic system, the inherited cultural difference and the accompanying behavioral difference may have played an important role.

Fig. 4.

Total cases per million capita in Germany (as of 31 May 2020). Note: The figure was generated in Python. The colored tape in the right part of the figure indicates the total confirmed cases per million capita as of 31 May 2020. The data used are taken from JHU CCSE (https://github.com/owid/covid-19-data)

Empirical Analysis

Data and Measurement

Transmission Outcome of COVID-19

The COVID-19 data we use are compiled by the Johns Hopkins University Center for Systems Science and Engineering (JHU CCSE) from various sources. We use the total cases per million capita (CASE, hereafter) to measure the transmission outcome of COVID-19. Since the timing of the outbreak varies from country to country, we set the date when a country’s CASE reached one as the first day of the outbreak to make each country start at the same point. Based on this, we determine the CASE 60 days after this starting point (Case60). However, the number of CASE is greatly determined by other factors, such as the detection rate, which also varies between countries. An alternative indicator is death cases, which could also be biased since the death rate is influenced by other factors, such as the population structure and medical conditions. We thus use the CASE data as our main measure and use the death cases (Death60) for robustness tests. We also determine corresponding indicators 30 days after the first day of the outbreak as an alternative measure for early-stage outcomes and 180 days after the first day of the outbreak as a measure for late-stage outcomes, represented by Case30, Death30, Case180, and Death180.

Individualism Versus Collectivism

Our measure for IC is based on Hofstede et al. (2010), which covers the measurement of national cultural data for 76 countries. We supplement some missing data from https://www.hofstede-insights.com/ and obtain 103 observations. Considering the availability of other data, we finally have 101 effective observations.3 The index 'Individualism' ranges from 0 to 100 and measures how important the individual is relative to the collective in a society, with higher values indicating more individualist societies.

Instrumental Variables

Since the cross-country differences in IC already existed long before the outbreak of COVID-19, reverse causality from COVID-19 to IC is impossible. However, other unobserved omitted factors that impact the spread of COVID-19 may also correlate with IC cultural differences. In addition, the index of individualism we use may be measured with errors since it is constructed based on survey data, and this may create attenuation that biases the least square estimates downward. These problems will be addressed using an instrumental variable approach.

Following Ang (2019), we use pronoun drop in languages and absolute latitude as the instruments for IC. An essential language difference connected to the distinction of IC is the grammatical rule of whether pronoun (i.e., “I” and “You”) dropping is allowed. Languages that require the inclusion of pronouns in a sentence (i.e., English) tend to appear more frequently in individualistic societies (Kashima & Kashima, 1998). We use the data from Davis and Abdurazokzoda (2016), which cover 94 countries or territories. Pronoun drop is a dummy variable indicating whether the dominant language allows the personal pronoun to be dropped, where one indicates “allow” and zero otherwise. The rationale for using absolute latitude as an instrument is similar to the parasite stress theory of values, which predicts that locations with a higher prevalence of infectious diseases would develop more collectivistic cultures. Since infectious diseases are historically more prevalent in equatorial countries, individualism is positively correlated with absolute latitude. Data on absolute latitude (Latitude) are taken from the Quality of Government Standard Dataset 2020.

Control Variables

To reduce potential omitted variable bias, we also incorporate a vector of factors that may impact the cross-country transmission difference of COVID-19. The first sets of control variables are exogenous environmental factors, including a country’s distance to the nearest coast (Dist_coast), terrain roughness (Ruggedness), and precipitation (Precipitation). The second set of control variables is the basic population structure. First, we control the population density measured by population size per square kilometer (Density). Second, we control the percentage of the population between the ages of 15 and 64 (Age1564).

The third set of variables includes factors that may act as possible transmission routes from IC to the spread of COVID-19, including Government Response, Quality of Government, Personal Autonomy and Individual Rights (Personal Autonomy), and GDP per capita. The fourth set of variables includes other competing factors of IC that may also cause cross-country differences in COVID-19 transmissions, such as legal origins, religion, trust, and democracy. These variables are widely used in related studies about IC cultural differences and studies about COVID-19 transmission (e.g., Ang, 2019; Nikolaev et al., 2017; Qiu et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). We will discuss these variables in more detail later.

The government response data are obtained from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT). We mainly use the original stringency index for our study purpose, which only captures variations in containment and closure policies. According to this index's score distribution (measured from 1 to 100), a score larger than 20 indicates that a country started to take relatively stringent policies. We calculate the number of days from the date the first case was reported in a country to the date that the country started to implement policies with a stringency index larger than 20 as the measurement of governmental response speed (Government Response).

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics of all variables, and Table 10 in the Appendix provides a detailed description of these variables and data sources.

Table 1.

Summary statistics

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case60 | 101 | 952.026 | 1296.031 | 3.329 | 5976.27 |

| Death60 | 97 | 55.151 | 115.674 | 0.096 | 664.647 |

| Individualism | 101 | 38.871 | 22.092 | 6 | 91 |

| Pronoun drop | 83 | 0.663 | 0.476 | 0 | 1 |

| Latitude | 101 | 30.406 | 17.176 | 0 | 64 |

| Dist_coast | 100 | 45.305 | 38.218 | 0 | 100 |

| Ruggedness | 100 | 1.399 | 1.221 | 0.016 | 6.740 |

| Precipitation | 98 | 1155.286 | 778.769 | 51 | 3240 |

| Age1564 | 100 | 64.852 | 5.623 | 50.975 | 85.089 |

| Density | 100 | 236.880 | 809.152 | 2.974 | 7953 |

| Government response | 96 | 6.667 | 19.843 | − 48 | 53 |

| Quality of government | 97 | 0.591 | 0.203 | 0.194 | 0.972 |

| GDP per capita | 99 | 24,591.34 | 21,446.93 | 1140 | 114,456 |

| Personal autonomy | 101 | 10.752 | 3.804 | 0 | 16 |

| Legal origins | 88 | ||||

| Catholics | 88 | 35.966 | 39.122 | 0 | 97 |

| Muslims | 88 | 20.386 | 34.081 | 0 | 99 |

| Other denomination | 88 | 30.545 | 32.945 | 0 | 99 |

| Trust | 73 | 0.259 | 0.140 | 0.035 | 0.690 |

| Index of democratization | 101 | 23.099 | 12.538 | 0 | 48 |

| Level of democracy | 101 | 7.554 | 2.773 | 0 | 10 |

| Power distance | 101 | 64.386 | 21.027 | 11 | 100 |

| Masculinity | 101 | 47.356 | 18.653 | 5 | 100 |

| Uncertainty avoidance | 101 | 64.653 | 21.275 | 8 | 100 |

| Long-term orientation | 84 | 43.596 | 23.892 | 3.526 | 100 |

| Indulgence | 80 | 47.882 | 23.130 | 0 | 100 |

Legal Origin variables are dummies for UK, France, Socialist, German, and Scandinavian = 1 if legal origin; 0 otherwise

Table 10.

Definitions of variables and data sources

| Variable | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Pronoun drop | A dummy variable that indicates whether the language allows the personal pronoun to be dropped, where 1 indicates “allow” and 0 otherwise | Abdurazokzoda and Davis (2016) |

| Latitude | The absolute value of the latitude of each country | CIA World Fact Book (2017) |

| Dist_coast | Average distance to nearest ice-free coast (1000 km) | “nunn_dist_coast” and “nunn_rugged” from The Quality of Government Standard Dataset 2020 (QOG, hereafter) |

| Ruggedness | Ruggedness is measured in hundreds of meters of elevation difference for grid points 30 arc-seconds apart | |

| Precipitation | Average precipitation is the long-term average in depth (over space and time) of annual precipitation in the country | “wdi_precip” from QOG |

| Age1564 | Percentage of the population between the ages 15 and 64 | World Bank dataset, https://data.worldbank.org.cn/ |

| Density | Population per square kilometer | JHU CCSE COVID-19 Data Repository on Github: |

| Government Response | The number of days from the date the first case in a country was reported to the date the country started to implement policies with a stringency index larger than 20 | Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) (www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/COVIDtracker) |

| Quality of Government | The mean value of the variables “Corruption”, “Law and Order,” and “Bureaucracy Quality” scaled 0–1. Higher values indicate higher quality of government | “icrg_qog” from QOG |

| GDP per capita | GDP per capita based on purchasing power parity (PPP). Data are in constant 2011 international dollars | “wdi_gdpcappppcon2011” from QOG |

| Personal Autonomy | Countries are graded between 0 (worst) and 16 (best) on personal autonomy and individual rights | “fh_pair” from QOG |

| Legal Origins | Legal origins dummies for UK, France, Socialist, German, and Scandinavian = 1 if legal origin; 0 otherwise | “lp_legor” from QOG |

| Catholics | Catholics as a percentage of the population in 1980 | “lp_catho80” from QOG |

| Muslims | Muslims as a percentage of the population in 1980 | “lp_muslim80” from QOG |

| Other Denomination | Percentage of the population belonging to other denominations (except Protestants, Catholics, and Muslims) in 1980 | “lp_no_cpm80” from QOG |

| Trust | Fraction of respondents who answered “yes” to the question “most people can be trusted.” We take the average value for all the available waves of the survey | WVS Database |

| Index of Democratization | The index of democratization is formed by multiplying the competition and the participation variables and then dividing the outcome by 100 | “van_index” from QOG |

| Level of Democracy | The scale ranges from 0–10, where 0 is the least democratic and ten the most democratic | “fh_ipolity2” from QOG |

| Power distance | The extent to which the less powerful members of a society accept and expect that power is distributed unequally | Hofstede et al. (2010)/2010, retrieved from http://geert-hofstede.com and https://www.hofstede-insights.com/ |

| Masculinity | The extent to which a society favors achievement, heroism, assertiveness, and material rewards for success | |

| Uncertainty avoidance | The extent to which the members of a society feel uncomfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity | |

| Long-term orientation | The extent to which a society favors a more pragmatic approach by encouraging thrift and efforts in modern education as a way to prepare for the future | |

| Indulgence | The extent to which a society allows relatively free gratification of basic and natural human drives related to enjoying life and having fun |

OLS Regression

We first estimate the following regression model (Eq. (1)) to examine how the early-stage transmission outcome of COVID-19 is related to IC cultural differences:

| 1 |

where is an indicator of the early-stage transmission outcome of COVID-19, is the national individualism index, is a vector of control variables as discussed above, and ε is an unobserved error term. The specification includes (1) geographic variables of distance to the nearest coast, terrain roughness, and precipitation and (2) population factors of the percentage of the population between the ages 15 and 64 (Age1564), and population density (Density). The results are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

OLS estimates of IC and the early-stage transmission of COVID-19

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Only individualism | Add geographic | Add population | Baseline model | Add Europe | Add possible channels | |

| Individualism | 28.282*** | 28.138*** | 27.376*** | 27.558*** | 18.810*** | 6.037 |

| (5.77) | (6.664) | (5.856) | (6.645) | (6.797) | (7.249) | |

| Dist_coast | 5.257 | 3.395 | 2.577 | − 1.215 | ||

| (3.780) | (3.844) | (3.749) | (3.049) | |||

| Ruggedness | − 16.534 | − 57.042 | − 57.835 | 180.036 | ||

| (93.757) | (100.055) | (89.949) | (103.683) | |||

| Precipitation | − 0.057 | − 0.009 | 0.044 | 0.330* | ||

| (0.173) | (0.156) | (0.154) | (0.179) | |||

| Age1564 | 55.564** | 50.313** | 51.820** | − 49.316** | ||

| (22.038) | (24.312) | (25.140) | (21.731) | |||

| Density | − 0.126** | − 0.158** | − 0.152** | − 0.347*** | ||

| (0.047) | (0.066) | (0.064) | (0.083) | |||

| Europe | 815.708** | 533.370* | ||||

| (335.101) | (296.199) | |||||

| Government Response | 10.833* | |||||

| (5.805) | ||||||

| GDP per capita | 0.054*** | |||||

| (0.010) | ||||||

| Quality of Government | − 1282.612 | |||||

| (923.531) | ||||||

| Personal Autonomy | 12.529 | |||||

| (39.788) | ||||||

| N | 101 | 98 | 100 | 98 | 98 | 90 |

| R2 | 0.232 | 0.249 | 0.284 | 0.293 | 0.354 | 0.591 |

| F | 24.024 | 7.250 | 10.853 | 5.726 | 6.000 | 7.120 |

Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. ***, ** and * indicate significance at the 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1 levels, respectively. For display purposes, the unit of Density is converted to the population per hectare in the table. Lithuania and Taiwan have no data on precipitation, and Serbia has no data on all exogenous environmental factors. Taiwan has no data on population variables. Fiji, Latvia, Malta, and Morocco are further excluded in Column (6) due to the lack of data on Government Response. Syria is excluded in Column (6) due to a lack of GDP per capita data. Cape Verde, Nepal, and Bhutan are excluded in Column (6) due to a lack of data on the Quality of Government

The missing values are missing at random due to the availability of data and include both observations of high IC (e.g., Latvia, 70) and low IC (e.g., Fiji, 14). Removing these observations from the baseline specification does not change the result (see Column (2) of Table 11 in Appendix for details)

Column (1) reports a simple bivariate regression model where Case60 is regressed only on the Individualism index and suggests a significant positive association between the two. If causal, the results imply that when Individualism increases by one standard deviation (22.092), Case60 increases by 624.8, approximately a half standard deviation (0.482). The R-squared indicates that the cultural difference alone explains approximately 23 percent of global variations.

Columns (2) to (4) of Table 2 report the results of gradually adding control variables. The coefficients of Individualism are significantly positive in all models, indicating the robustness of the impact of IC on Case60. That is, in countries and territories with stronger individualism, COVID-19 causes more serious harm to the population 60 days after the outbreak. In addition, according to Columns (3) and (4), the variable Age1564 is significantly positive, while the variable Density is significantly negative, indicating that the population structure does impact the transmission of COVID-19. However, the impact direction of population density is contrary to our prediction, which may be caused by other confounding factors. The regression coefficients of basic geographic factors are insignificant, implying that these variables lack explanatory power.

Since Europe, as a special continent, contains most of the individualistic counties and has been severely struck by COVID-19, it is possible that some special features of Europe, not IC cultural differences, cause the outcomes revealed in the above regressions. It is also possible that IC works mainly through Europe due to its very high level of individualism. We thus add Europe as a dummy in Column (5) and further add controls for several possible channels through which IC may impact the transmission of COVID-19 in Column (6): Government Response, GDP per capita, Quality of Government, and Personal Autonomy. Unsurprisingly, the dummy of Europe is positively significantly associated with Case60. Our Individualism index keeps its significance in Column (5), while the magnitude of the effect is drastically reduced, which indicates that IC may work partly through Europe, and IC cannot fully explain the special features of Europe that cause the spread of COVID-19. Our Individualism index loses its significance in Column (6), suggesting that IC could work through these transmission channels to impact the spread of COVID-19. We provide further tests for these channels in Sect. 4.8, showing that our Individualism index is strongly and significantly correlated.

The estimates reported in Table 2 provide strong support for a significant association between IC and the early-stage transmission outcome of COVID-19. However, mean regression estimators ignore potential unobserved variables that may correlate with both independent and dependent variables and cause omitted variable bias. We will run further regressions using external instruments for IC.

Instrumental Variable Estimates

In this part, we use the pronoun drop and absolute latitude to obtain the exogenous sources of variation in IC cultural differences. This identification strategy is valid as long as the pronoun drop and the absolute latitude have no direct impact on the spread of COVID-19. It is easy to understand that the pronoun drop cannot directly impact the transmission of the virus. The absolute latitude can be directly related to the temperature, which may be an important physical determinant of the virus's spreading speed. Two reasons may relieve this concern: first, no evidence of a pattern between spread rates and ambient temperature has been found for COVID-19 (Jamil et al., 2020); second, since temperature varies around the globe with seasons, we use the same standard for the starting point of the outbreak for all countries, which makes temperature less important in our analysis. In addition, the pronoun drop and the absolute latitude may be connected to other cultural dimensions that may cause behavioral differences influencing the spread of the virus. We will control other cultural dimensions later in Sect. 4.4 to address this concern.

We use the IV-2SLS regressions in the following estimations. Equations (2) and (3) illustrate the first and second stages of our model. In the first stage, we regress our Individualism index on the pronoun drop (Pronoun drop) and the absolute latitude (Latitude), as well as a set of controls. In the next stage, we use the predicted values of our Individualism index to estimate the transmission outcome of COVID-19 while controlling for a set of confounding variables.

| 2 |

| 3 |

The IV-2SLS regressions are presented in Table 3. Panel A of Table 3 reports the second-stage regression results, and Panel B presents the first-stage results. Some diagnostics checks are also reported in Panel C. Across all specifications except when adding possible channel factors, we document that the Pronoun drop is significantly inversely related to the Individualism index and the Latitude is significantly positively related to the Individualism index in the first stage, which gives strong credence to their use as instruments for Individualism. In addition, the first-stage F-statistics are markedly larger than the rule-of-thumb value of 10 in all cases except in Column (6), suggesting that the instruments used are strong. In the second-stage regressions, the coefficients of Individualism are significant at the 1% significance level in all cases except in Column (6). The coefficients also carry the expected positive sign, providing strong support for our proposition that the spread of COVID-19 is even worse in individualistic societies. As an illustration, the coefficients of Column (4) where all baseline geographic and population factors are added suggest that when Individualism increases by one standard deviation (22.092, close to the gap between Norway (69) and the UK (89)), Case60 increases by 870.6, which is 0.672 units of standard deviation. This prediction is quite close to the actual gap in Case60 between Norway (1401.7) and the UK (2560.3).

Table 3.

Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) Results

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | A. second-stage regression (Dep.Var. = Case60) | |||||

| Individualism | 36.064*** | 40.294*** | 34.930*** | 39.408*** | 27.148** | 21.412 |

| (7.525) | (8.954) | (7.531) | (8.963) | (12.046) | (21.271) | |

| Dist_coast | 1.802 | 1.931 | 1.810 | 0.875 | ||

| (3.023) | (3.25) | (3.153) | (2.886) | |||

| Ruggedness | 157.506 | 137.37 | 102.075 | 200.140* | ||

| (98.488) | (106.041) | (105.159) | (102.347) | |||

| Precipitation | 0.247 | 0.24 | 0.213 | 0.375 | ||

| (0.192) | (0.193) | (0.185) | (0.266) | |||

| Age1564 | 29.213*** | 12.483 | 11.889 | − 41.220* | ||

| (10.696) | (16.706) | (15.657) | (21.270) | |||

| Density | − 0.071* | − 0.073 | − 0.071 | − 0.223** | ||

| (0.038) | (0.055) | (0.049) | (0.099) | |||

| Europe | 644.383* | 655.448** | ||||

| (381.561) | (310.121) | |||||

| Government Response | 13.327** | |||||

| (6.065) | ||||||

| GDP per capita | 0.037*** | |||||

| (0.011) | ||||||

| Quality of Government | − 1509.323 | |||||

| (945.464) | ||||||

| Personal Autonomy | − 27.408 | |||||

| (66.960) | ||||||

| N | 83 | 80 | 82 | 80 | 80 | 78 |

| R2 | 0.241 | 0.258 | 0.253 | 0.267 | 0.361 | 0.427 |

| B. First–stage estimates (Dep.Var. = Individualism) | ||||||

| Pronoun drop |

− 18.047*** (4.217) |

− 17.788*** (4.573) |

− 17.431*** (4.306) |

− 17.484 *** (4.785) |

− 17.314*** (4.620) |

− 11.084** (4.737) |

| Latitude |

0.736*** (0.094) |

0.682*** (0.121) |

0.772*** (0.096) |

0.720*** (0.126) |

0.763 (0.216) |

0.302 (0.187) |

| N | 83 | 80 | 82 | 80 | 80 | 78 |

| R2 | 0.616 | 0.626 | 0.625 | 0.631 | 0.631 | 0.733 |

| C. Diagnostic checks | ||||||

| 1st-stage F-statistic | 73.851 | 54.340 | 79.099 | 61.977 | 17.699 | 5.429 |

| 1st-stage partial R2 | 0.616 | 0.548 | 0.621 | 0.550 | 0.435 | 0.159 |

| Hansen J statistic (OID test) |

0.134 (p = 0.715) |

0.614 (p = 0.433) |

0.025 (p = 0.873) |

0.441 (p = 0.506) |

0.310 (p = 0.578) |

0.233 (p = 0.629) |

Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. ***, ** and * indicate significance at the 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1 levels, respectively. Angola, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cape Verde, Fiji, Honduras, Luxembourg, Malawi, Malta, Mozambique, Namibia, Nepal, Qatar, Senegal, Slovakia, Sri Lanka, Syria, and United Arab Emirates are excluded from the 2SLS regressions due to a lack of data on the pronoun drop variable (18 samples).

The missing values due to a lack of data on the pronoun drop are not missing at random since most of them are less developed countries and are in low IC. However, this removing these observations from the baseline specification still does not change the result (see Column (3) of Table 11 in Appendix for details).

Latvia and Morocco are further excluded in Column (6) due to the lack of data on Government Response

It is noted that the coefficients of Individualism using the instrumental variables approach are consistently larger than the coefficients based on the OLS estimates, regardless of how the control variables are included. One possible reason is that the sample size of the 2SLS regression is smaller than that of the OLS regression, and the local treatment effect from IV estimates is larger than the average effect over the entire sample of OLS regression. Other possible reasons are the Individualism scores are measured with some errors or that IC may impact the spread of COVID-19 via other channels that cannot be observed.

It is also important to note that if pronoun drops and absolute latitude can affect the spread of COVID-19 through other channels, we will not obtain proper identification of the model. We further run Hansen J overidentification tests to check whether the exclusion restriction assumption is satisfied. The results in Panel C suggest that our instruments are valid. However, it is well known that this is not a robust test. When adding possible channels in Column (6), the Individualism index loses its significance in the second-stage regression, and the first-stage F-statistic is smaller than the rule-of-thumb value of 10. In addition to the individualism index’s high correlation with these possible channels, the insignificance could be caused by overidentification since we have many variables.

Testing for Competing Hypotheses

Several fundamental social and institutional factors that could affect individual and public behaviors may influence the spread of COVID-19. These important factors include legal origin, religion, trust, and democracy. We test the validity of each of these factors in predicting the spread result of COVID-19 relative to the role of individualism versus collectivism. Table 4 reports the re-estimation of our Model (4) from Table 3 by adding these factors; thus, in all regressions, we control for the baseline geographic effects (Dist_coast, Roughness, Precipitation) and population factors (Age1564, Density). To save space, we report only necessary, important indicators in the following tables, including Table 4.

Table 4.

Testing for competing hypotheses (IV-2SLS)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. second-stage regression (Dep.Var. = Case60) | ||||||

| Individualism | 44.432*** | 49.060*** | 31.038*** | 41.257*** | 32.822** | 27.234** |

| (8.587) | (9.094) | (6.809) | (15.832) | (14.974) | (13.183) | |

| French | 652.337** | 87.877 | ||||

| (305.191) | (295.18) | |||||

| Socialist | − 189.057 | − 551.275 | ||||

| (435.843) | (486.051) | |||||

| German | 96.182 | 45.022 | ||||

| (547.298) | (608.518) | |||||

| Scandinavian | 448.543 | 634.867 | ||||

| (754.27) | (1090.064) | |||||

| Percent Catholic | 12.92 | 16.04 | ||||

| (8.028) | (14.952) | |||||

| Percent Muslim | 10.767 | 10.093 | ||||

| (7.168) | (13.858) | |||||

| Other Denomination | − 0.282 | 8.748 | ||||

| (8.088) | (13.696) | |||||

| Trust | − 918.485 | 307.274 | ||||

| (821.02) | (1334.29) | |||||

| Level of Democracy | − 25.98 | 31.956 | ||||

| (93.981) | (78.178) | |||||

| Index of Democratization | 13.456 | |||||

| (18.055) | ||||||

| Baseline controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 71 | 71 | 67 | 80 | 80 | 58 |

| R2 | 0.309 | 0.325 | 0.317 | 0.257 | 0.313 | 0.443 |

| B. First–stage estimates (Dep.Var. = Individualism) | ||||||

| Pronoun drop | − 14.485*** | − 19.797*** | − 15.936*** | − 15.931*** | − 15.533*** | − 3.933 |

| (5.527) | (5.087) | (6.015) | (4.574) | (4.686) | (6.073) | |

| Latitude | 1.210*** | 0.677*** | 0.776*** | 0.469*** | 0.464*** | 1.217*** |

| (0.201) | (0.153) | (0.159) | (0.155) | (0.151) | (0.192) | |

Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. ***, ** and * indicate significance at the 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1 levels, respectively. Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Ethiopia, Germany, Latvia, Russia, Slovenia, and Ukraine (9 samples) are further excluded in Columns (1) and (2) due to the lack of data on legal origins and religions. Austria, Belgium, Costa Rica, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Jamaica, Kenya, Panama, Portugal, Sierra Leone, and Suriname (13 samples) are further excluded in Column (3) due to a lack of data on trust. All 22 samples disappear from the regression in Column (6)

Removing these missing observations from the baseline specification still does not change the result (see Column (4) of Table 11 in Appendix for details)

First, we consider the role of legal origins. Following the work of La Porta et al. (1999), the historical origin of a country's laws is highly correlated with a broad range of its legal rules and regulations, as well as with economic outcomes. Column (1) of Table 4 reports the result when adding the legal traditions dummy variables, with British origin as the reference. We find that compared to countries with British and Socialist legal origins, countries with French legal traditions are associated with more cases of COVID-19, while there is no significant difference between other legal origins. The coefficients of Individualism are still significant at the 1% significance level when adding the role of legal origins, and the magnitudes are even larger than the baseline regressions, suggesting IC’s robust influence on the spread of COVID-19.

Second, since religious belief is a major driver of human behavior, we include religion in Column (2). Catholics, Muslims, and Other Denomination variables represent the percentages of each country's population that are Catholic, Muslim, and not Catholic, Muslim, or Protestant. The result demonstrates that only Individualism is significantly positively correlated with the spread result of COVID-19. All religious composition variables are statistically insignificant.

Third, we consider the role of trust in Column (3). Trust and the related concept of social capital have been considered fundamental drivers of social distancing behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic (Bargain & Aminjonov, 2020; Bazzi et al., 2021; Durante et al., 2021). For example, Bargain and Aminjonov (2020) show that compared to residents in regions with lower levels of trust, residents in European regions with high levels of trust decrease mobility for unnecessary activities. However, the coefficient of Trust is statistically insignificant in our models, while the coefficient of Individualism remains highly significant at the 1% level.

Finally, we consider the fundamental difference in democracy with two different measures. The first is the index of Level of Democracy from Freedom House. The second is the Index of Democratization from the Finnish Social Science Data Archive. According to the results reported in Columns (5) and (6), both democracy indicators are statistically insignificant, but the coefficient of Individualism remains highly significant at the 1% level.

We next further consider the role of other cultural dimensions relative to the role of IC. In addition to measuring IC, Hofstede et al. (2010) measured five other national cultural distinctions: Power distance, Masculinity, Uncertainty avoidance, Long-term orientation, and Indulgence. The definitions for these cultural variables are provided in Table 10 in the Appendix. These cultural variations may be correlated with our Individualism index and may be fundamental determinants of the spread of COVID-19. Table 5 reports our main 2SLS estimations by taking into account these alternative culture indicators. In Column (1), we present our baseline estimates based on Individualism as the measure of culture for reference. In Columns (2) to (6), we find that except for Uncertainty avoidance, all additional cultural differences have no statistically significant effects on the transmission outcome of COVID-19, while the Individualism variable remains highly significant in all regressions.

Table 5.

Testing for other cultural dimensions (IV-2SLS)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. second-stage regression (Dep.Var. = Case60) | ||||||

| Individualism | 39.408*** | 50.448*** | 36.458*** | 42.953*** | 43.834*** | 44.092*** |

| (8.963) | (14.659) | (8.354) | (9.374) | (11.748) | (10.619) | |

| Power distance | 13.282 | |||||

| (10.268) | ||||||

| Masculinity | − 11.27 | |||||

| (7.696) | ||||||

| Uncertainty avoidance | 12.964** | |||||

| (5.743) | ||||||

| Long-term orientation | 0.079 | |||||

| (5.871) | ||||||

| Indulgence | − 0.514 | |||||

| (5.616) | ||||||

| N | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 70 | 70 |

| R2 | 0.267 | 0.211 | 0.310 | 0.288 | 0.275 | 0.277 |

| Baseline controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| B. First–stage estimates (Dep.Var. = Individualism) | ||||||

| Pronoun drop | − 17.484 *** | − 11.020*** | − 17.609*** | − 14.048*** | − 16.189*** | − 10.699* |

| (4.785) | (4.776) | (4.306) | (5.240) | (5.408) | (5.678) | |

| Latitude | 0.720*** | 0.539*** | 0.830*** | 0.763*** | 0.871*** | 0.864*** |

| (0.126) | (0.128) | (0.115) | (0.130) | (0.188) | (0.167) | |

Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. ***, ** and * indicate significance at the 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1 levels, respectively. Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Jamaica, Kenya, Kuwait, Panama, Sierra Leone, and Suriname have no data on both variables of long-term orientation and indulgence. Ethiopia has no data on long-term orientation, and Israel has no data on indulgence

Removing these missing observations from the baseline specification still does not change the result (see Column (5) of Table 11 in Appendix for details)

Robustness with Alternative Measures of the Transmission Outcome of COVID-19

As mentioned above, the total confirmed cases per million capita data we used could be biased by other factors, such as the detection rate. Therefore, we further run regressions by using the total deaths per million capita to measure the outcome of COVID-19 transmission. In addition to using the figures of 60 days (Case60 and Death 60) after the first day of the outbreak to measure the early-stage transmission outcome, we consider the date of 30 days after the outbreak as an alternative measure for early-stage outcomes and 180 days after the outbreak as a measure for later-stage outcomes, represented by Case30, Death30, Case180, and Death180 respectively. The 2SLS regression results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Robustness tests (Alternative outcome of COVID-19, IV-2SLS)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case60 | Death60 | Case30 | Death30 | Case180 | Death180 | |

| Individualism | 39.408*** | 2.831*** | 16.342*** | 0.253** | − 26.277 | 0.977 |

| (8.963) | (0.841) | (4.526) | (0.116) | (38.901) | (1.362) | |

| N | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| R2 | 0.267 | 0.275 | 0.243 | 0.141 | 0.075 | 0.063 |

| Baseline controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. ***, ** and * indicate significance at the 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1 levels, respectively

Column (2) of Table 6 shows that the coefficient of Individualism is also significantly positive at the 1% level, which further confirms that higher individualism causes a higher percentage of deaths 60 days after the outbreak. Columns (3) and (4) show that this significant impact of cultural difference is robust when we use the data from 30 days after the outbreak. The coefficients of Individualism are not significant when considering data from 180 days after the outbreak. This result supports our prediction that the IC difference would have significant explanatory power for the early-stage spread of COVID-19, while its impact may be weakened over time.

Robustness with Alternative Measures of Individualism

We next provide additional tests using alternative measures of IC for robustness. The first is from the work of Schwartz (1994), who provides IC measures according to an autonomy-embeddedness dimension. We use the index of autonomy-embeddedness (Embeddedness) and its two subindexes on affective and intellectual autonomy as an alternative measure of IC cultural distinction. Affective autonomy measures the extent to which people are encouraged to seek enjoyment and pleasure for themselves, while the Intellectual autonomy index measures the extent to which people are encouraged to pursue independent ideas and thoughts. The data of Schwartz (1994) cover 78 countries and 70 cultural groups, and 58 observations are left when we merge it with other data.

The second source is from Gelfand et al. (2004), which provides 61 countries’ rankings on IC. We use their measured Collectivism Practices and Collectivism Values as alternative measures of IC. Collectivism Practices measures an individual’s altitude regarding how society “is”, while Collectivism Values measures an individual’s altitude regarding how society “should be”. Higher scores indicate greater collectivism for both indicators. The data are available for 49 observations in our estimations. We find that the coefficient of Collectivism Practices is significantly negative (Column (5)), while the overall regression model for the Collectivism Values is insignificant (Column (6)), probably due to too few observations.

The third source is from Suh et al. (1998), which provides a summary index that combines the individualism ratings of both Hofstede (1980) and Triandis (1995). Consequently, the higher score of Suh et al. (1998) indicates greater individualism. We have 48 matched observations for this measure. Table 7 reports the main 2SLS regressions. Except for the Collectivism Values measure of Gelfand et al. (2004), all the alternative measures have coefficients that are significant at the 1% level. These results further consolidate our main argument that IC cultural differences are important influencing factors in the early-stage transmission of COVID-19.

Table 7.

Robustness tests (Alternative Measures of Individualism, IV-2SLS)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. second-stage regression (Dep.Var. = Case60) | |||||||

| Individualism | 39.408*** | ||||||

| (8.963) | |||||||

| Embeddedness | − 2071.9*** | ||||||

| (493.28) | |||||||

| Affective Autonomy | 1522.8*** | ||||||

| (377.93) | |||||||

| Intellectual Autonomy | 1990.5*** | ||||||

| (509.84) | |||||||

| Collectivism Practices | − 991.58*** | ||||||

| (280.16) | |||||||

| Collectivism Values | − 7911.3 | ||||||

| (4834.32) | |||||||

| Suh et al. (1998) | 490.43*** | ||||||

| (115.686) | |||||||

| Baseline controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 80 | 58 | 58 | 58 | 49 | 49 | 48 |

| R2 | 0.267 | 0.364 | 0.238 | 0.357 | 0.2 | 0.368 | |

| B. First–stage estimates (Dep.Var. = Individualism) | |||||||

| Pronoun drop | − 17.48 *** | 0.139 | − 0.317*** | − 0.024 | 0.877*** | 0.025 | − 2.006*** |

| (4.785) | (0.086) | (0.098) | (0.087) | (0.185) | (0.106) | (0.551) | |

| Latitude | 0.720*** | − 0.017*** | 0.021*** | 0.019*** | − 0.02*** | − 0.005 | 0.047*** |

| (0.126) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.006) | (0.004) | (0.019) | |

Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. ***, ** and * indicate significance at the 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1 levels, respectively

Robustness with Sub-samples

Although we controlled for other possible exogenous variables, such as geographical factors and population, there may still be some continent-specific unobserved heterogeneities that may impact the spread of COVID. In addition, the regression outcomes may be driven by a few outliers or countries with a unique COVID-19 experience, such as China or the USA. Table 8 reports our main 2SLS estimations by taking into account these considerations. We first include a dummy of the continent, with Africa as a reference. We then exclude Africa (Column (2)), North America (Column (3)), South America (Column (4)), Asia (Column (5)), Europe (Column (6)), and Oceania (Column (7)) in sequence. We also exclude the three most populous countries of China, the USA, and India, which have different degrees of Individualism (Column (8)).

Table 8.

Robustness tests (Sub-Samples, IV-2SLS)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second-stage regression (Dep.Var. = Case60) | ||||||||

| Individualism | 29.628** | 40.193*** | 40.281*** | 43.254*** | 39.517*** | 10.728 | 43.151*** | 38.508*** |

| (13.693) | (11.231) | (9.8) | (8.987) | (11.928) | (9.947) | (9.003) | (9.333) | |

| America | 518.89 | |||||||

| (406.04) | ||||||||

| Asia | 149.068 | |||||||

| (327.20) | ||||||||

| Europe | 818.05 | |||||||

| (510.71) | ||||||||

| Oceania | − 1590.4* | |||||||

| (886.69) | ||||||||

| Excluded | Whole Sample | No Africa | No North America | No South America | No Asia | No Europe | No Oceania | No China, USA, India |

| N | 80 | 69 | 70 | 71 | 61 | 51 | 78 | 77 |

| R2 | 0.432 | 0.236 | 0.227 | 0.304 | 0.271 | 0.149 | 0.35 | 0.2 |

Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. ***, ** and * indicate significance at the 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1 levels, respectively

The Individualism variable remains highly significant in all regressions except when Europe is excluded (Column (6)). In addition, although we find that Europe has a significantly higher transmission outcome than the rest of the world in Table 2, the coefficient of Europe is insignificant in Column (1) of Table 8 when all continent dummies are included. Since most of the individualistic countries in our sample are located in Europe, excluding Europe leaves us only 51 observations. The remaining observations have very little variation in the Individualism index. On the other hand, there are also large cultural differences within Europe, such as in the case of Germany discussed in Sect. 3. For these reasons, we believe that it is necessary to examine the differences in COVID-19 transmission outcomes within Europe.

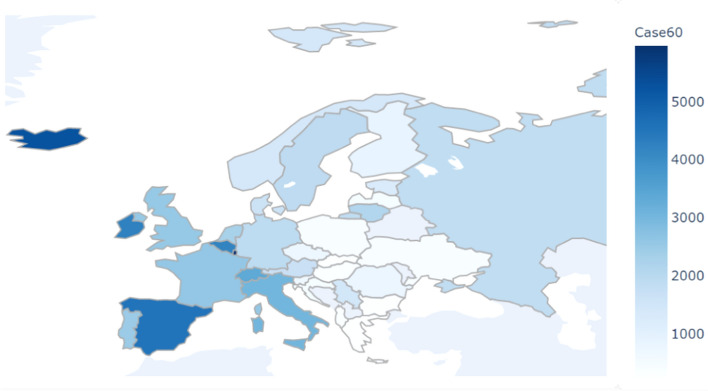

According to the generalized division of Western Europe, we divide the 34 counties in our sample into the western part of Europe (19 countries, including the United Kingdom, Netherlands, France, Switzerland, Finland, Italy, Norway, Denmark, Ireland, Belgium, Luxembourg, Iceland, Sweden, Germany, Austria, Malta, Portugal, Spain, and Greece) and the eastern part of Europe (15 countries, including Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic, Ukraine, Slovakia, Albania, Croatia, Slovenia, Serbia, Romania, Russia, Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia). The average Individualism index of the western part of Europe is 64.21, which is significantly higher than that of the eastern part (43.67) (p = 0.002, two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test). Figure 5 illustrates the total confirmed cases per million capita 60 days after each European country's major outbreak (Case60), with darker color indicating more cases. We find a clear pattern in Fig. 5 that COVID-19 spread much faster in the western part of Europe than in the eastern part of Europe. Using a two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test, we find that both the average Case60 (2711.5) and Death60 (207.4) in the western part of Europe are significantly larger than those in the eastern part (mean values of 681.0 for Case60 and 22.9 for Death90) (p < 0.001, tests of difference for both indicators).

Fig. 5.

Early-stage transmission outcomes of European countries. Note: The figure was generated in Python. The colored tape in the right part of the figure indicates the total confirmed cases per million capita 60 days after a country's daily cases reached 0.1 per million capita (variable Case60). The data used are taken from JHU CCSE (https://github.com/owid/covid-19-data)

However, Fig. 5 shows that Russia did not perform well in controlling the spread of COVID-19 as a collectivist country in Europe. Its total cases per million capita 60 days after the first day of the outbreak were 1864.15, almost the same as those in Germany (1929.04) and Demark (1641.69). Russia cannot be treated as a collectivist society globally. Russia’s IC score is 39, while the median score is 30 in our 101 samples. However, in Europe, Russia is collectivist compared to the rest of the European countries since the median score is 60 in the 34 European countries in our sample. The special case of Russia could be caused by other confounding factors, such as the uniqueness of Russian governance. Another remarkable example illustrated in Fig. 5 is the distinction between Portugal and Spain. The two countries are contiguous, while Spain (Individualism index 51) is much more individualistic than Portugal (Individualism index 27). Correspondingly, the total number of cases (and deaths) per million capita 60 days after the first day of the outbreak is much higher in Spain (Case60, 4533.9; Death60, 519.2) than in Portugal (Case60, 2503.2; Death60, 104.2).

The effect of IC culture on COVID-19 spread is also found within Europe in the study of Gokmen et al. (2021), who used data between the date of reaching the 100th total case and the date of the 60th day. As discussed in Sect. 3, the significantly more cases and deaths per million capita in former West Germany than in former East Germany also support this story. However, although this cultural distinction also exists in other countries, such as the USA (Vandello and Cohen, 1999), the within-country variation is negligible compared to the cross-country differences. For example, with an Individualism score of 91, the USA is the most individualistic society in the world, even though some Americans are more collectivistic than others, holding highly collectivistic values and behaving in the way of collectivism. For this reason, we do not include further within-country regression in the present study, while we acknowledge that the causality from IC distinction to the transmission outcome of COVID-19 would be better established with within-country variations.

Possible Channels

We have discussed several channels through which IC can impact the spread of COVID-19. First, as we highlight in the introduction, an important channel may come from different governments' response speeds to take control measures. We use the governmental response speed (Government Response) defined in Sect. 4.1 to measure this variation.

Second, as widely found in previous literature, since individualism leads to more openness in trade and higher income levels than collectivism, the high population mobility along with active economic activities in individualistic societies may facilitate the spread of the virus. We use the GDP per capita to capture the fundamental economic development level.

Third, since IC can shape formal institutions (Licht et al., 2007; Tabellini, 2008), which further determine governmental measures in the face of COVID-19, we further consider the indicator of Quality of Government developed by the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG).

Fourth, as we argued in the introduction, another important channel is individual behaviors shaped by IC. Since people in individualistic cultures value personal freedom, they are less likely to accept governmental controls, such as quarantine or staying at home. We use the indicator of personal autonomy and individual rights (Personal Autonomy) developed by Freedom House to capture this possible channel.

We test the association between our Individualism index and the four possible channels. Table 9 reports the main results. We show that the governmental response time of more individualistic countries is significantly longer than that of collectivistic countries (Column (1)). The coefficient suggests that a country’s government will take 6.7 days longer to take relatively stringent controls when increases by one standard deviation (22.092). As an extreme case, the UK took 44 days after the first case was reported to implement a stringent governmental response, the slowest in Europe. Similar to the UK, other extreme individualistic countries of Canada took 46 days, and the USA took 41 days, while all countries took less than 6.7 days, on average.

Table 9.

Possible channels (IV-2SLS)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government response | GDP per capita | Quality of government | Personal autonomy | |

| Individualism | 0.304*** | 579.693*** | 0.009*** | 0.152*** |

| (0.121) | (109.379) | (0.001) | (0.015) | |

| N | 78 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| R2 | 0.264 | 0.600 | 0.578 | 0.478 |

| IV-F | 56.537 | 61.977 | 61.977 | 61.977 |

| Partial R2 | 0.547 | 0.550 | 0.550 | 0.550 |

| Baseline controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. ***, ** and * indicate significance at the 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1 levels, respectively. Latvia and Morocco are excluded in Column (1) due to the lack of data on the Government Response

The GDP per capita is significantly higher in individualistic countries than in collectivistic countries (Column (2)). Higher Individualism is also associated with a higher quality of government (Column (3)) and a higher level of personal autonomy and individual rights (Column (4)). Combined with the results obtained from Table 3, we suggest that the IC distinction could impact the spread of COVID-19 through these channels, while the quality of government works in the opposite direction of the other channels. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that other important channels may exist.

Conclusion and Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic is largely reshaping the global political and economic landscape. In this context, it is of great theoretical and practical significance to explore the deep-seated social and cultural causes that affect the spread of the virus. Departing from the popular debate on political systems or the sources of the virus, we propose a new perspective regarding the IC cultural dimension. The IC cultural distinction results in differences among different subpopulations in various individual and public behaviors in everyday life in the face of the pandemic and lead to disparate governmental responses, which finally causes the large difference in the transmission outcomes of COVID-19.

Although our study is based on data from the COVID-19 pandemic, the conclusions should still hold for other similar infectious diseases. It should be noted that the basic hypothesis of this study is that the impact of IC is "intuitive." With the development of the pandemic, personal attitudes and government responses could evolve to adapt to the environment, and economic factors and technologies, such as vaccines, could play an increasingly important role; thus, the role of cultural differences may be more crucial in the early stage of the pandemic, and the COVID-19 pandemic can even profoundly change people's cultural orientations in the end. Consequently, the IC distinction could explain the transmission difference in the early pandemic stage but should be interpreted with caution when applied to other conditions.

However, it is time to seriously think about the role of IC not only in the current pandemic but also in the future. As an implication of the parasite stress theory of values and the current study, the increasing individualism across the globe may expose us to a higher risk of infectious diseases. On the other hand, the pandemic’s serious consequences may hurt our inclusiveness, creativity, rights, and liberties, leading our world toward more closed, conservative, and unfriendly societies resistant to free trade and economic development. The advantage of collectivism in the early pandemic does not mean that it will outperform individualism in other conditions. In a later stage, when the roles of vaccines and high quality of governance become more important in stopping the spread of the virus, the underdeveloped world featuring collectivism could be in a more disadvantageous position. We need a balance between collectivism and individualism in the future. We should not let the pandemic stop our advancement toward a more open and inclusive world. We should also avoid extreme individualism and cherish the value of contributions and responsibilities to others and society.

We acknowledge some limitations of the present study. First, since our analysis is based on worldwide data and each country may be unique in some ways, it is impossible to control these fixed effects with the current cross-sectional data. Second, although we considered several controls and possible competing factors, we only considered fundamental factors, while many specific reasons may be omitted. For example, the rapid early spread of the virus in Europe could be aggravated by the ski season, travel patterns, or inexperience in coping with airborne pathogens. Third, we show with empirical data that IC culture impacts the spread of the virus in the early stage and discuss several channels, while we cannot prove causality in the absence of microscopic behavioral data. What we do is to kick open an interesting question for further research, preferably with the sort of data that could further dissect the competing explanations.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following for discussion, assistance and comments: Geng Niu, Jianan Li, Ruiming Liu, Zhao Chen, Wei Wei, China Young Economists Association, China Young Economic Scholars Forum, Chinese Culture and Economy Forum.

Appendix

Table 11.

OLS estimates of the baseline specification by removing missing observations

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (OLS) |

Remove 1 (OLS) |

Remove 2 (OLS) |

Remove 3 (2SLS) |

Remove 4 (2SLS) |

|

| Individualism | 27.558*** | 28.897*** | 28.664*** | 25.849*** | 43.791*** |

| (6.645) | (7.059) | (6.476) | (5.977) | (10.096) | |

| Dist_coast | 3.395 | 2.284 | 3.156 | ||

| (3.844) | (4.545) | (3.762) | |||

| Ruggedness | − 57.042 | 23.756 | 104.220 | ||

| (100.055) | (134.115) | (126.70) | |||

| Precipitation | − 0.009 | − 0.002 | 0.097 | ||

| (0.156) | (0.182) | (0.167) | |||

| Age1564 | 50.313** | 51.618** | 15.265 | ||

| (24.312) | (24.729) | (14.988) | |||

| Density | − 0.158** | − 0.142** | − 0.097 | ||

| (0.066) | (0.071) | (0.062) | |||

| Baseline controls | Yes | Yes | |||

| N | 98 | 90 | 80 | 58 | 69 |

| R2 | 0.293 | 0.307 | 0.301 | 0.326 | 0.273 |

Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. ***, ** and * indicate significance at the 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1 levels, respectively. Column (2) reports the baseline OLS regression by removing the missing observation of Column (6) in Table 2, including Fiji, Latvia, Malta, Morocco, Syria, Cape Verde, Nepal, and Bhutan. Column (3) reports the baseline OLS regression by removing the missing observation of Column (4) in Table 3 due to a lack of data on the pronoun drop variable. Column (4) reports the baseline 2SLS regression by removing the missing observation of Column (6) in Table 4 due to a lack of data on legal origins, religions, and trust. Column (5) reports the baseline 2SLS regression by removing the missing observation of Columns (5) and (6) in Table 5 due to a lack of data on other cultural variables

Authors' Contributions

All authors contributed equally.

Funding

The National Social Science Fund of China (21BJL126).

Data Availability

We will make all data available as the manuscript is accepted for publication.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest between all authors or any other institute.

Footnotes

Because of their far distance from Wuhan, the rare instance of case importation, better medical infrastructure and sufficient time to prepare, there is no reason to the believe that counties such as the USA would perform worse than China.

The three countries are all highly collective societies but with different political and economic systems, and they reported the most cases in the first phase of the global outbreak.

We have the cultural data of Puerto Rico and Hong Kong, but their COVID-19 data are not included in the JHU CCSE dataset.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Allcott H, Boxell L, Conway J, Gentzkow M, Thaler M, Yang D. Polarization and public health: Partisan differences in social distancing during the coronavirus pandemic. Journal of Public Economics. 2020;191:104254. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RM, Heesterbeek H, Klinkenberg D, Hollingsworth TD. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? The Lancet. 2020;395(10228):931–934. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang JB. Culture, legal origins, and financial development. Economic Inquiry. 2019;57(2):1016–1037. doi: 10.1111/ecin.12755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bargain O, Aminjonov U. Trust and compliance to public health policies in times of COVID-19. Journal of Public Economics. 2020;192:104316. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauch CT, Galvani AP. Social factors in epidemiology. Science. 2013;342(6154):47–49. doi: 10.1126/science.1244492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzi S, Fiszbein M, Gebresilasse M. “Rugged individualism” and collective (In) action during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Economics. 2021;195:104357. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur A, Gray D, Islam A, Bhuiyan S. A literature review of the economics of COVID-19. Journal of Economic Surveys. 2021;35(4):1007–1044. doi: 10.1111/joes.12423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur, A., Grigoryeva, I., & Kattan, L. (2021b). Stay-at-home orders, social distancing, and trust. Journal of Population Economics, 1–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Canning, D., Karra, M., Dayalu, R., Guo, M., & Bloom, D. E. (2020). The association between age, COVID-19 symptoms, and social distancing behavior in the United States. medRxiv.

- Carter H, Drury J, Rubin GJ, Williams R, Amlôt R. The effect of communication during mass decontamination. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal. 2013;22(2):132–147. doi: 10.1108/09653561311325280. [DOI] [Google Scholar]