ACTIVATION OF EXECUTIONER CASPASES

Executioner caspases, when activated, cleave hundreds or thousands of substrates in the cell to orchestrate apoptosis. In most animals, the executioner caspases have short prodomains lacking interaction sites for other proteins (the exception, as we have noted in Green (2022a), is in nematodes, which have an executioner caspase with a long, interactive prodomain). The inactive forms (or “proforms”) of these caspases exist in the cell as dimers, with the potential to form two active sites. These are constrained from forming their active sites until they are cleaved between the large and small subunits. This cleavage permits the chain–chain interaction that snaps the two active sites into place, allowing the now-mature protease to be maximally functional. This is an important rule for understanding apoptosis that bears repeating:

The executioner caspases that orchestrate apoptosis preexist in cells as inactive dimers that are activated by cleavage between the large and small subunits.

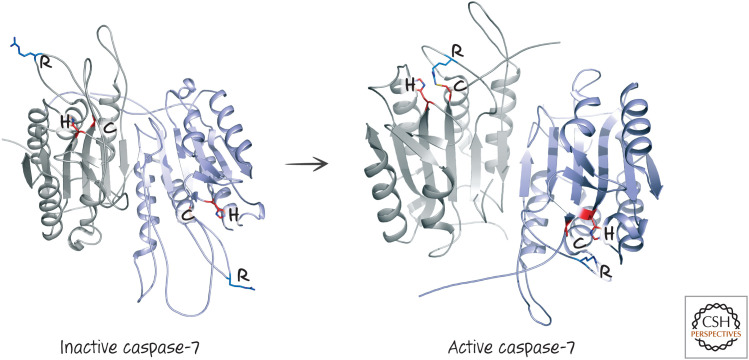

In the inactive proforms of the executioner caspases, the catalytic dyads are not in position to gain access to the target aspartate in the substrate protein. A look at one procaspase structure shows us why (Fig. 1, left). This is the structure of inactive procaspase-7, and we can see how it changes as it becomes activated (Fig. 1, right).

Figure 1.

The structures of inactive and active caspase-7. The arginine (R) in the specificity loop is indicated, as is the cysteine–histidine (C–H) catalytic dyad. (Left, PDB 1K86 [Chai et al. 2001]; right, PDB 1GOF [Reidl et al. 2001a].)

Note that both the inactive and active forms of the enzyme are dimers (remember the rule above), with two active sites. On activation, the active cysteine–histidine dyads do not move; what changes is the structure of the loop that ultimately forms the substrate-specificity pocket (the arginine that interacts with the target aspartate in the substrate is indicated). The reason that this shape change occurs on cleavage is shown in Figure 2.

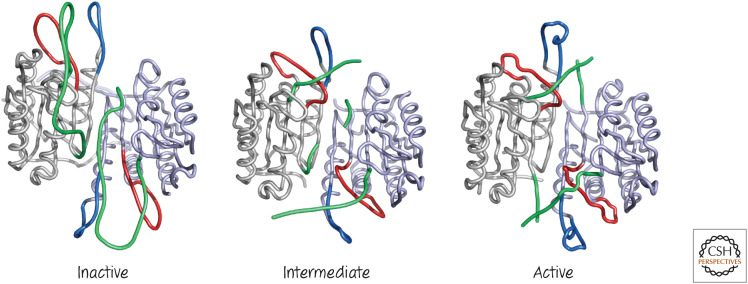

Figure 2.

Close-up view of caspase-7 activation. Three loops mediate caspase-7 active site assembly: the specificity loop (red), a neighboring loop that draws the specificity loop into position (blue), and the linker between the large and small subunits (green). Structures are the inactive zymogen (left), the inhibitor-bound enzyme (center), and the active enzyme (right). (Left, PDB 1K86 [Chai et al. 2001]; center, PDB 1F1J [Wei et al. 2000]; right, PDB 1GOF [Reidl et al. 2001a].)

In the inactive form, the center of the dimer is occupied by the region of each caspase monomer that serves as the linker between the large and small subunits. When the linker is cleaved, it leaves the central region, and each end interacts with an end of the cleaved linker from the other chain, thus stabilizing the structure and holding the ends away from the center. Now, each loop comprising the specificity pockets can snap into position, drawn into place by a neighboring loop. The “elbow” of the specificity loop stretches into the center of the dimer, the region previously blocked by the linker. The result is the formation of two active sites in the mature caspase.

Once activated in this way, the caspases act in trans to remove the small prodomains as well. This changes the size of the mature protein, but it does not seem to be important for executioner caspase activation or function.

What mediates the cleavage event that activates the procaspases? In the case of caspase-6 in mammals, the cleavage responsible for activation is effected by caspases-3 and -7. Caspases-3 and -7 can also cleave and activate proforms of other caspases-3 and -7 dimers, although this is not an efficient process.

But this begs the question: What first cleaves and thereby activates the executioner caspases to cause apoptosis? The answer, in the vast majority of cases, is the initiator caspases—in particular, caspases-8 and -9 in vertebrate cells. However, before considering these caspases and how they work, we briefly consider another enzyme capable of cleaving and activating the executioner caspases. In doing so, we delineate our first, albeit simplified, apoptotic pathway.

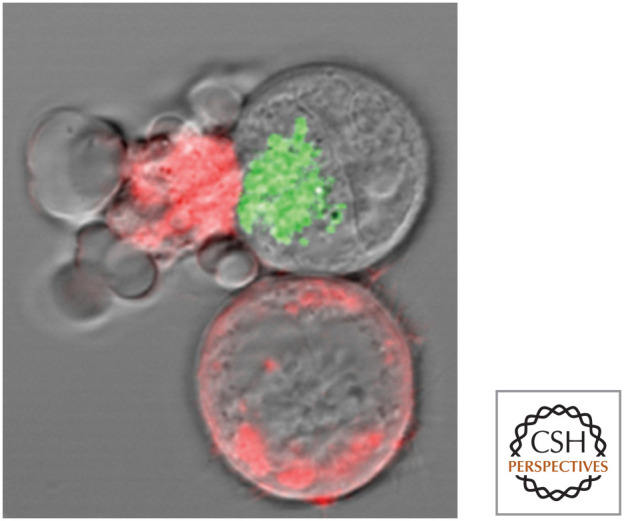

INTERLUDE: GRANZYME B AND APOPTOSIS INDUCED BY CYTOTOXIC LYMPHOCYTES

Viruses are tricky little things. They quickly infect and subjugate cells for the production of more virus, posing special problems for multicellular organisms seeking to eliminate these pests. In vertebrates (and perhaps other animals), one approach to this problem is cytotoxic lymphocytes (cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells) that identify virally infected cells and cause them to undergo apoptosis, destroying both the cells and the viruses that they harbor. Figure 3 shows the killing of a target cell by a cytotoxic lymphocyte. The cell death has all of the morphological and biochemical characteristics of apoptosis (the characteristic blebbing is apparent in Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Cytotoxic lymphocyte killing a target (cell). The target cells are stained red, and the cell at left is undergoing apoptosis. Green: cytotoxic granules in the cytotoxic lymphocyte. (Reproduced from Bleakley 2008, ©2008 with permission from Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. Image kindly provided by Dr. I.S. Goping, University of Alberta.)

Cytotoxic lymphocytes have several means at their disposal for dispatching their target cells, but here we concern ourselves with only one—the function of cytotoxic granules—and only one of the ways in which these granules work. During cell killing, the contents of the cytotoxic granules are released onto the membranes of the target cells. The released molecules include a pore-forming protein, perforin, and a collection of proteases called granzymes. One of the latter is granzyme B. Granzyme B is a protease, but, unlike caspases, it is a serine protease (i.e., its active site contains a serine, rather than a cysteine). However, like the caspases, granzyme B is an endopeptidase that cleaves after aspartic acid residues, such as those involved in activating executioner caspases.

When the cytotoxic lymphocyte contacts a target cell and releases its granule contents, perforin permits the entry of the granzymes into the cell that is the victim of this murderous assault (Fig. 4).1 If sufficient granzyme B is present, it cleaves caspases-3 and -7 at the aspartate between the large and small subunits of each, activating the caspases. The result is a feed-forward activation that kills the cell by apoptosis, effectively removing the compromised cell and the virus in the process.

Figure 4.

Simplified scheme of cytotoxic granule killing.

This mechanism is not restricted to viral infections—it includes immune responses by cytotoxic lymphocytes to other intracellular infections as well as responses to tumor cells and foreign tissue grafts. This mechanism of killing is not the only way in which cytotoxic lymphocytes work, nor is it the only way granzyme B can function to trigger apoptosis. However, it illustrates how caspase activation can occur in this bona fide apoptotic pathway.

ACTIVATION OF INITIATOR CASPASES

In the vast majority of cases in which apoptosis occurs, the proteases that trigger executioner caspase activation are the initiator caspases. In mammals, these are predominantly caspases-8 and -9. When activated, they can cleave and thereby activate the executioner caspases, resulting in apoptosis.

Unlike executioner caspases, initiator caspases (as well as other caspases, such as inflammatory caspases and caspase-2) exist in cells as inactive monomers. And also unlike executioner caspases, these monomers are not activated by cleavage but, instead, by dimerization. This is a second key rule of caspase activation that bears repeating:

Initiator caspases preexist in cells as inactive monomers. They can only be activated by dimerization.

Once the initiator caspases dimerize, they become active and can cleave themselves between the large and small subunits, which can act to stabilize the dimer. Therefore, although cleavage does not activate the caspase, it does have a function.

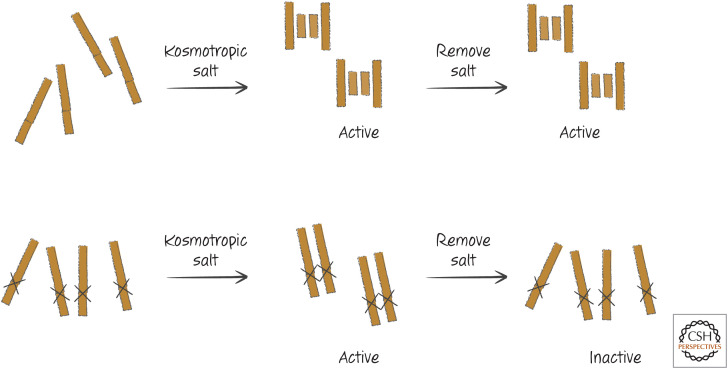

The idea that the activation of initiator caspases involves bringing monomers together to form dimers is called the “induced proximity” model. The principle can be shown experimentally using recombinant caspases that lack the prodomains. For example, when such a truncated caspase-2, -8, or -9 is produced, each is enzymatically inactive. But if salt conditions are altered to promote aggregate formation, caspase activity quickly appears (Fig. 5, upper middle). This happens regardless of whether the caspases can undergo cleavage—that is, even if the cleavage sites between the large and small subunits have been mutated (Fig. 5, lower middle).

Figure 5.

Initiator caspases can be activated by induced proximity. Kosmotropic salts, which cause protein aggregation, activate initiator caspases that remain active after the salt is removed. If the cleavage sites between the protease subunits are made uncleavable by mutation, the salts can still activate the enzyme, but the enzyme becomes inactive when the salts are removed.

When the salt is removed, the cleaved active dimers remain active (Fig. 5, upper right). But if the caspase was uncleavable (because of mutation), its activity is rapidly lost (Fig. 5, lower right). This is why we say that cleavage of initiator and related caspases is not required for activity but serves to stabilize the dimers. The stabilizing effect of cleavage has been shown for caspase-2 and caspase-8 and might apply to other caspases as well. An exception is caspase-9, in which cleavage does not stabilize the dimer (as we will see, the effect of caspase-9 cleavage is more complex).

This stability, however, is important. Although a noncleavable mutant of caspase-8, for example, can demonstrably be activated by dimerization, it does not efficiently promote apoptosis. We return to this when we consider the biological functions of caspase-8 in apoptosis and other phenomena.

But now, there arises a major question: What dimerizes the initiator caspases (and the other caspases that behave in this way)? The answer is adapter proteins.

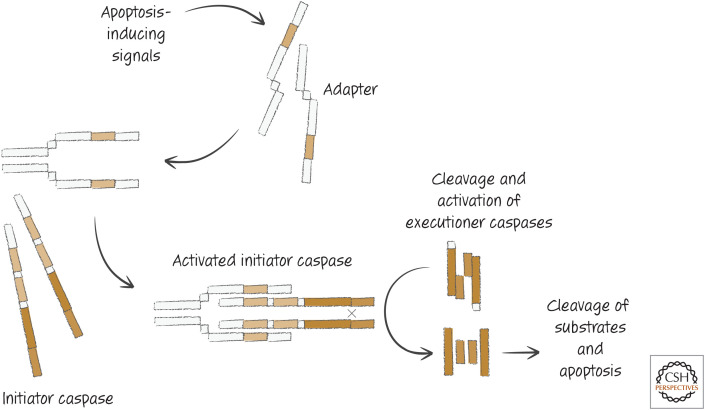

ADAPTER PROTEINS INTERACT WITH CASPASES VIA DEATH FOLDS

All caspases that are not executioner caspases have long prodomains containing regions that interact with other proteins—the adapter proteins. To activate caspases, however, these adapter proteins must not only bind the caspases but also dimerize them. In general, this occurs through processes that dimerize or oligomerize the adapters. How this happens is through distinct interactions, depending on the adapter. These interactions, the adapters involved, and the initiator caspase engaged all define the different apoptotic (or related) pathways that are the subjects of other reviews in this subject collection. All of these apoptotic pathways, however, have the basic form shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

General apoptotic pathways.

The protein–protein interaction regions in the prodomains of initiator, inflammatory, or other caspases are of different types, depending on the caspase. Caspases-8 and -10 have two death effector domains (DEDs). Caspases-1, -4, and -5 (and in rodents, caspase-11), caspase-2, and caspase-9 (the initiator caspase) all have caspase-recruitment domains (CARDs). DEDs and CARDs are also involved in other protein–protein interactions not involving caspases, and so the presence of such a domain is not itself a demonstration that the protein is involved in caspase activation or apoptosis.

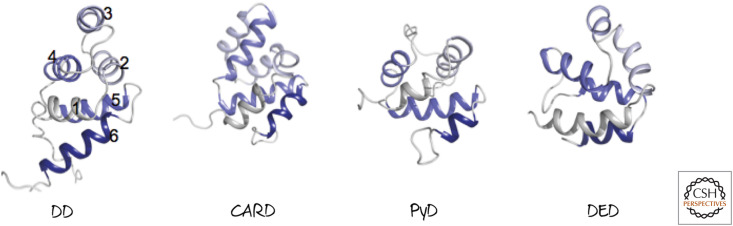

Although DEDs and CARDs are not related by sequence homology, they are structurally similar (Fig. 7). This type of structure has been termed a “death fold.” Other sequences that form death folds are also shown in Figure 7, including a death domain (DD) and a pyrin domain (PyD). Although these are not generally found in mammalian caspases, they are found in some of the molecules leading to caspase activation. As an intriguing aside, one of the caspases identified in zebrafish has a PyD (not seen in the prodomains of mammalian caspases) in its prodomain.

Figure 7.

Representative death folds. Although different death folds do not have sequence similarity, they are structurally related. Each has six globular helical bundles, shown here colored gray to dark purple from the amino to carboxyl termini.2 (Left to right, PDB 1DDF [Huang et al. 1996]; PDB 1CWW [Day et al. 1999]; PDB 1PN5 [Hiller et al. 2003]; PDB 1A1Z [Eberstadt et al. 1998].)

In general, these protein–protein interaction regions work by like–like recognition. That is, a protein that binds to a CARD in a caspase will do so through its own CARD. Although not every CARD (DED, DD, or PyD) will interact with every similar domain (in fact, the motif generally interacts with only one other protein, although there are exceptions), the binding will be through like–like domain recognition.

This theme frequently recurs in other reviews in this subject collection, with sentences that take on the form “the X domain in protein A binds to the X domain of protein B.” Why things have turned out this way is not at all obvious. It does, however, seem as though there is a deep, but elusive, evolutionary principle at work in these interactions.

ACTIVATION OF INITIATOR CASPASES BY DIMERIZATION

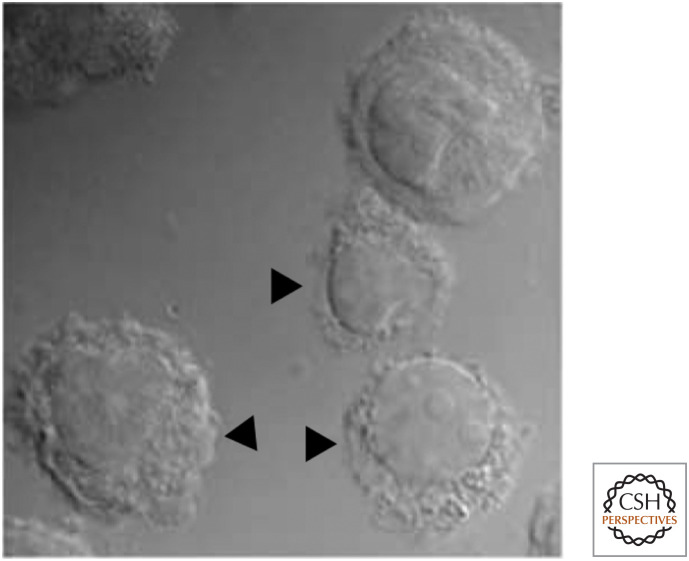

How does dimerization activate initiator caspases, and why is cleavage not required for proteolytic function but only for stabilization of the dimer? The proforms of the initiator (and other) caspases, as with the executioner caspases, are inactive because the specificity-determining pocket in the enzyme is disorganized and out of position for bringing the substrate to the catalytic cysteine–histidine dyad. However, unlike the case for executioner caspases, for initiator caspases this has nothing to do with the linker region between the large and small subunits, which is not cleaved until after the caspase is activated. Instead, another loop from the opposite chain in the dimer is needed to effectively pull the loop containing the substrate-specificity pocket into position. In caspase-9, this event can only happen at one protease site (of the pair) at a time, owing to constraints in the dimer. Figure 8 shows this interaction in the caspase-9 dimer that produces an active site.

Figure 8.

The transition from inactive to active caspase-9. When caspase-9 is dimerized, the specificity-determining loop (red) is brought into position by a loop (blue) from the other monomer. Cleavage of the region between the protease subunits (green) is not necessary for activation. Only one site in the dimer can form at a time: One is inactive (left) and the other is active (right). (Reproduced with permission from Fuentes-Prior and Salvesen 2004, ©The Biochemical Society.)

Clearly, this formation of an active site in the protein depends on the formation of the dimer. When the inactive procaspase monomers are brought together by the appropriate adapter protein, the interaction results in the formation of an active site.

This has practical consequences for our understanding of apoptotic pathways because, although initiator caspases undergo cleavage on activation, cleavage does not itself activate them. Unfortunately, many studies have relied on detection of cleaved initiator caspases as an indication that the caspase has been activated en route to apoptosis. Such studies must be treated with caution. Similarly, a misunderstanding of the role of cleavage in initiator caspase activation has led some investigators to suggest that proteases that cleave initiator caspases thereby activate them, but we can now see that cleavage of the inactive monomer cannot do so. As with many areas of science, the fact that a conclusion is published does not make it true!

INITIATOR CASPASES CAN BE ACTIVATED BY DIMERIZATION WITH OTHER MOLECULES

The way in which initiator caspases are activated makes it possible for other proteins to induce the conformational changes necessary to form an active site in the caspase. Two such proteins are FLIP3 and MALT, both of which can be brought by adapter proteins to form heterodimers with the initiator caspase caspase-8.

FLIP is closely related to caspase-8 at the sequence level but lacks the cysteine necessary for proteolytic activity. When dimerized with caspase-8, FLIP interacts with the caspase so that it forms an active site, but, because FLIP is not a protease, caspase-8 is not cleaved. When FLIP is present, it prevents caspase-8-mediated apoptosis. This dimer, however, is important for a signaling event that is needed for cell survival in certain circumstances (see Green 2022b).

MALT is not related to caspases at the sequence level, but it has predicted structural similarities that classify it as a paracaspase.4 Like FLIP, MALT can be brought by adapter proteins into forming heterodimers with caspase-8. Again, the activated caspase-8 is not cleaved, and the function of this heterodimer remains obscure. Nevertheless, it illustrates the principle that caspases need not necessarily be homodimers to be active.

OTHER INITIATORS AND EXECUTIONERS IN THE CASPASE COLLECTION

So far, we have focused on mammalian caspases in our consideration of how they work. But, as we know, apoptosis is not restricted to vertebrates. A brief tour of the caspases in other organisms is warranted.

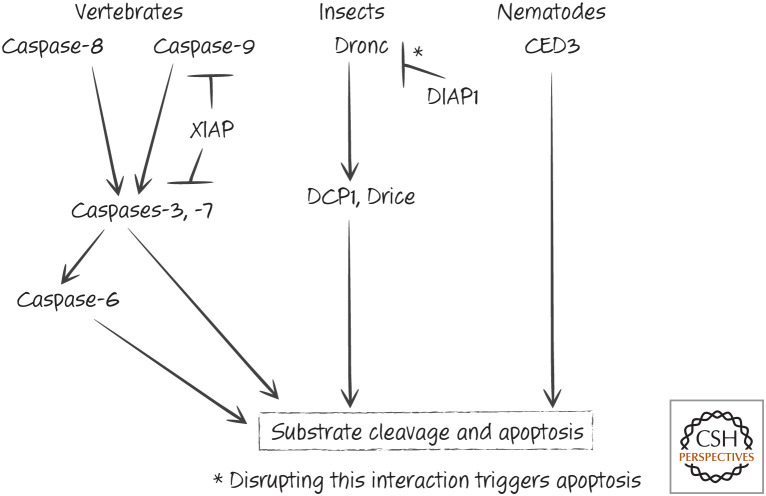

Two initiator caspases have been identified in Drosophila. Dredd, which contains DED regions in its prodomain, appears to have a nonapoptotic function that remains elusive. The other, Dronc, which has a CARD-containing prodomain, clearly functions as an initiator caspase, activating the executioner caspases Drice and DCP1 by cleaving them. Like other initiator caspases, Dronc is activated by dimerization. Another caspase, Strica, seems to have an unusual prodomain and might be an initiator caspase, although this is not proven.

In Caenorhabditis elegans, only one caspase is known to function in apoptosis. This caspase, CED3, has a long prodomain containing a CARD (see Fig. 4 in Green 2022a) and appears to be activated by dimerization. Once dimerized, CED3 then functions as an executioner caspase, causing the cell to die.

Is the process in C. elegans representative of the primordial apoptotic pathway, where activating one caspase causes death? Perhaps not. Cnidaria (including the hydroids, jellyfish, and corals), which are probably older in evolutionary terms than the nematodes, have both initiator- and executioner-type caspases, based on sequence. This might suggest that, somewhere along the way, nematodes lost caspases from the genome. This is not unlikely—the purple sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus), an echinoderm, has 31 different caspases; compare that with the relatively small number we find in vertebrate species. In time, we hope to learn how these novel caspases function in cell death or other phenomena in such organisms.

INFLAMMATORY CASPASES FUNCTION IN SECRETION AND CELL DEATH

In mammals (and other vertebrates), one caspase has a well-characterized role that is distinct from induction of cell death (although, as we will see, it can cause cell death). This is caspase-1. Like initiator caspases, it exists in cells as an inactive monomer and is activated by dimerization. However, at low levels of the active caspase, caspase-1 functions not as a killer but, instead, in inflammation. This is because caspase-1 processes (by cleavage) the precursor forms of two related cytokines: interleukin-1 and interleukin-18. These cytokines have important roles in inflammatory responses. The pathways involved in caspase-1 activation are discussed in Green (2022c), but, for now, it is worth noting that the same principles we have learned that apply to apoptosis apply to other caspases as well, even if the result is not apoptosis.

Caspase-1 occupies a position in the mammalian genome in close proximity to other related caspases, including caspases-4, -5, and -12 in humans and caspases-11 and -12 in rodents. For this reason, these are often also referred to as inflammatory caspases. Some of these—caspases-4 and -5 (human) and caspase-11 (rodent)—can participate in caspase-1 activation, as we will see later, but others such as caspase-12 do not.

Caspase-12 is particularly intriguing. It is found throughout mammals and primates, until we examine humans. Among sub-Saharan Africans, caspase-12 is expressed in about 20% of individuals. In contrast, most humans have a stop codon in the third exon that results in an unstable truncated protein. Evidence suggests that this null allele was positively selected during the African migration about 67,000 years ago. To get an idea of why this might have occurred, we have to consider what caspase-12 does. In general, the caspase itself appears to have very little activity. When coexpressed with caspase-1, it can dampen the activity of the latter. It is possible that, under some conditions in which strong caspase-1 function is a problem, this dampening function is favored, whereas, under other conditions, increased caspase-1 activity provides protection (e.g., from some infections). In any case, it might be correct to think about caspase-12 more as a regulator of protease activity than as a protease per se.

Caspase-1, in addition to processing interleukin-18 and interleukin-1, appears to have another role in inflammation that is not well understood, functioning in an unusual mode of secretion in the cells that express it. This secretion does not involve signal peptides or the endoplasmic reticulum (as conventional secretion does), but, beyond that, we do not yet know how such secretion occurs. Proteins that are secreted by this mechanism include interleukin-1β, interleukin-18, and proteins that are not processed by caspase-1, such as interleukin-1α and peptides with antibacterial activities.

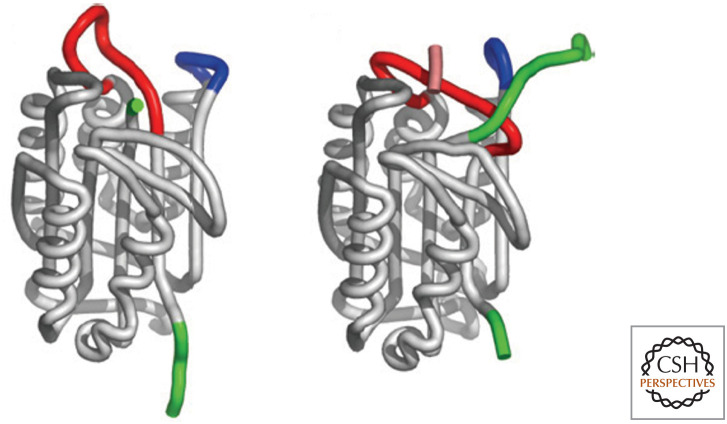

Under conditions of intense activation, caspase-1 can trigger cell death. Like initiator caspases, caspase-1 can cleave and activate at least one executioner caspase (caspase-7). But, in addition, it can itself cleave another substrate in the cell, resulting in a form of cell death that resembles necrosis. This caspase-1-triggered cell death is often referred to as “pyroptosis” (Fig. 9). The inflammatory caspases—caspases-4 and -5 in humans (and caspase-11 in rodents)—also cleave this substrate and induce pyroptosis. Pyroptosis and the secretion of inflammatory cytokines is discussed in much more detail in Green (2022c). It remains a possibility that it is this nonapoptotic cell lysis that is actually responsible for the mysterious “secretion” associated with caspase-1 activation, although this is a matter of debate.

Figure 9.

Pyroptosis. Cells die in a caspase-1-dependent manner, indicated by arrows. (Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd.: Fernandes-Alnemri et al. 2007, ©2007.)

In Drosophila, the initiator-like caspase Dredd does not seem to function in cell death but is involved in the secretion of peptides that have antibacterial activity. For this reason, it is therefore tempting to think of Dredd as a sort of inflammatory caspase.

Caspase-2: The “Orphan” Caspase

Caspase-2 was the second mammalian caspase discovered, and, by sequence, it is the most highly conserved among animals. Like the initiator and inflammatory caspases, it is activated by induced proximity of the inactive monomers, and cleavage serves to stabilize the mature enzyme. However, unlike the initiator caspases and caspase-1, caspase-2 does not seem to be very good at cleaving and activating the executioner caspases. It can cause apoptosis indirectly by engaging the mitochondrial pathway (discussed in Green 2022c), but this does not seem to be a primary function for this enzyme. We just do not know its primary function.

Caspase-2 has been implicated in the response to a number of stressors, but in no case is it absolutely required for apoptosis. What caspase-2 does and what it is “for” are unknown at present. Is caspase-2 important? In a mouse model of lymphoma, the absence of caspase-2 accelerates the appearance of tumors. No other caspase has such a profound effect in this model. As shown in Green (2022c), caspase-2 may have an important role in monitoring the cell cycle.

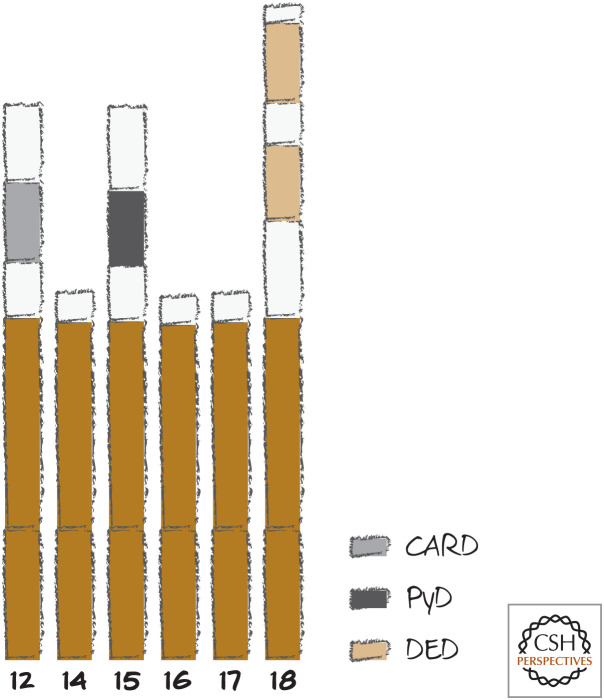

ON BEYOND 12

Vertebrates have a number of other caspases that have been characterized, and some have multiple copies of the ones that we have discussed. In most cases, their functions are unknown, as are the adapter molecules that activate them.5 Figure 10 shows a list of these vertebrate caspases.6 The figure is provided more as a point of interest and for the reader to get a feeling of the evolutionary plasticity in the system than as important information for the discussions that follow. That said, we might want to ask ourselves why a set of molecules that are so well conserved among the animals show so much variability, duplication, deletion, and modification, if the only role is to orchestrate apoptotic cell death.

Figure 10.

Caspase-12 and beyond in mammals. Lengths shown are arbitrary. Caspases-15, -17, and -18 are not found in humans, and caspase-12 is frequently not found in humans. Caspases-11 (mouse) and -13 (cow) are homologs of caspase-5 and caspase-3, respectively, and are not shown.

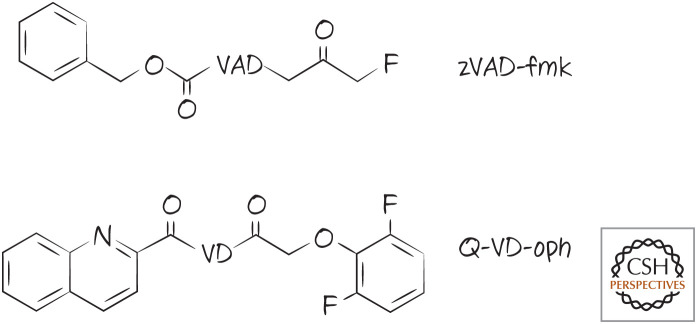

Figure 11.

Caspase inhibitors. The peptide portion is shown with a single-letter code.

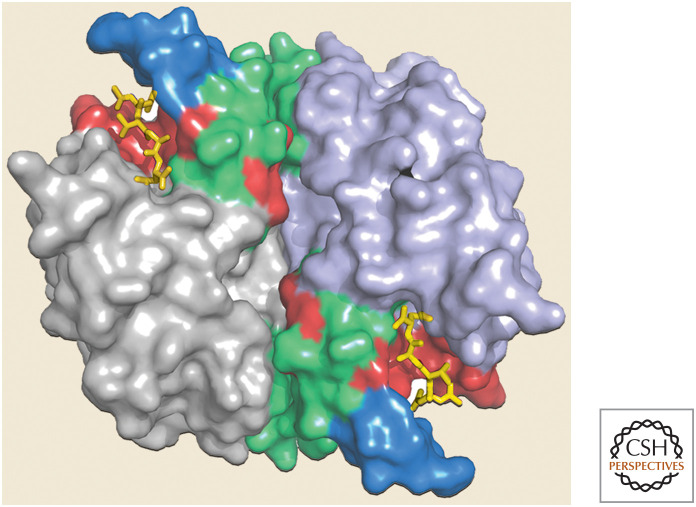

Figure 12.

Caspase-3 bound to the inhibitor zVAD-fmk. (PDB 1CP3 [Mittl et al. 1997].)

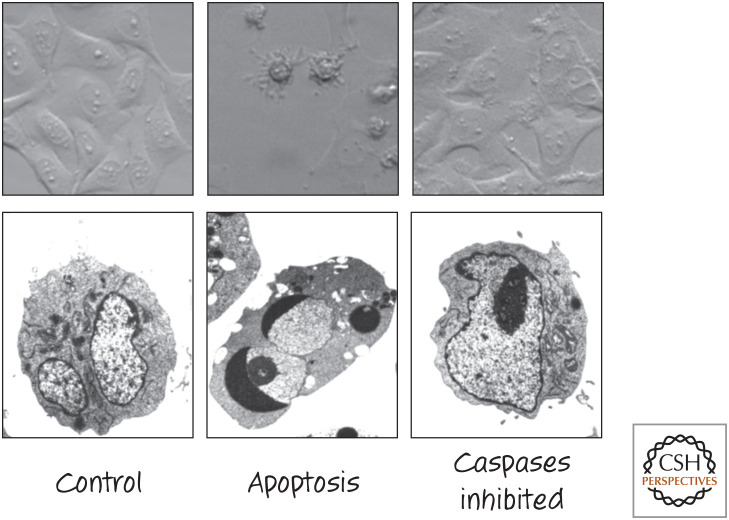

Figure 13.

Caspase inhibitors block the morphological features of apoptosis. Appearance of different cell types treated to induce apoptosis in the presence or absence of the caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk. (Upper) Bright-field images of fibroblasts. (Lower) Electron micrographs of tumor cells. (Images courtesy of Dr. Nigel Waterhouse, Mater Medical Research Institute, Brisbane, Australia.)

INHIBITION OF CASPASES IN CELLS

The importance of caspases in cell death and apoptosis leads us to the question of how they are regulated in cells, because it is almost axiomatic that anything so devastating must be inhibited at several levels. As we will see, however, endogenous caspase inhibitors are essential in some cases, but not all.

SYNTHETIC CASPASE INHIBITORS.

Peptides that are recognized by caspases can be fashioned into caspase inhibitors if a reactive “warhead” is appended to the P1 aspartate that binds (reversibly or irreversibly) to the active cysteine in the caspase. Again, as with the substrates, such inhibitors are not specific, although they are often effective as general caspase inhibitors (that can also inhibit other proteases as well). Therefore, although these can be useful for research, any conclusions that come from using them have to be regarded with care. Examples of synthetic inhibitors based on peptides are shown in Figure 11. The structure of caspase-3 bound to a peptide inhibitor is shown in Figure 12.

Other inhibitors of caspases that are not peptide based have been developed. These work by either binding to the active site or inhibiting the conformational changes needed for caspase activation.

If we induce apoptosis, for example, by stressing cells, and add agents that inhibit the executioner caspases, all of the characteristic morphological features of apoptosis are blocked (Fig. 13).

VIRAL AND ENDOGENOUS CASPASE INHIBITORS: INHIBITOR OF APOPTOSIS PROTEINS

When a virus infects a cell, it uses its host to make more virus, whereas, if the cell can undergo apoptosis before more virus is made, the infection can be stopped. But viruses have evolved strategies for preventing apoptosis. One strategy is to inhibit caspases.

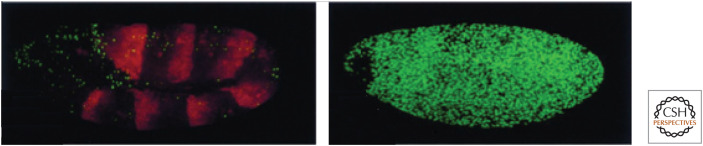

The insect virus baculovirus actually makes two different caspase inhibitors that work by different mechanisms. One is termed an “inhibitor of apoptosis protein” (IAP). When this was first identified, it quickly became apparent that insects have their own “IAP proteins” (the expanded term “inhibitor of apoptosis protein proteins” is, of course, redundant, but this phrase persists, and we will not buck the trend here). The most important of these is called DIAP1 (Drosophila IAP1, so named before a moratorium was called on Drosophila proteins starting with a “D”). DIAP1 binds to and inhibits the initiator Dronc and the executioner caspases. Experimental removal of DIAP1 is sufficient to cause apoptosis in fly cells and embryos (Fig. 14).

Figure 14.

Loss of DIAP1 causes apoptosis. Extensive cell death, staining green, is not seen in a wild-type embryo (left), but is observed in a DIAP1 mutant embryo (right). (Reprinted from Wang et al. 1999, ©1999 with permission from Elsevier.)

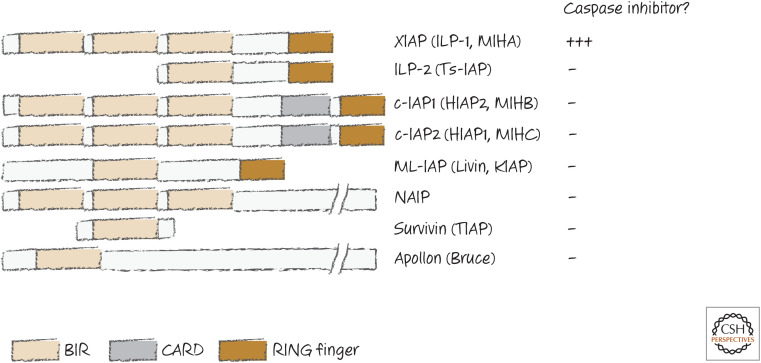

It was also quickly realized that IAP proteins are found in many animals, including humans, based on sequence similarities. All IAP proteins share one or more copies of a motif called the baculovirus IAP repeat (BIR). But—and this is very important—despite their somewhat unfortunate name, most IAP proteins do not inhibit caspases or block apoptosis. Some IAP proteins are listed in Figure 15. Those few capable of directly inhibiting caspases are noted.

Figure 15.

Some IAPs.

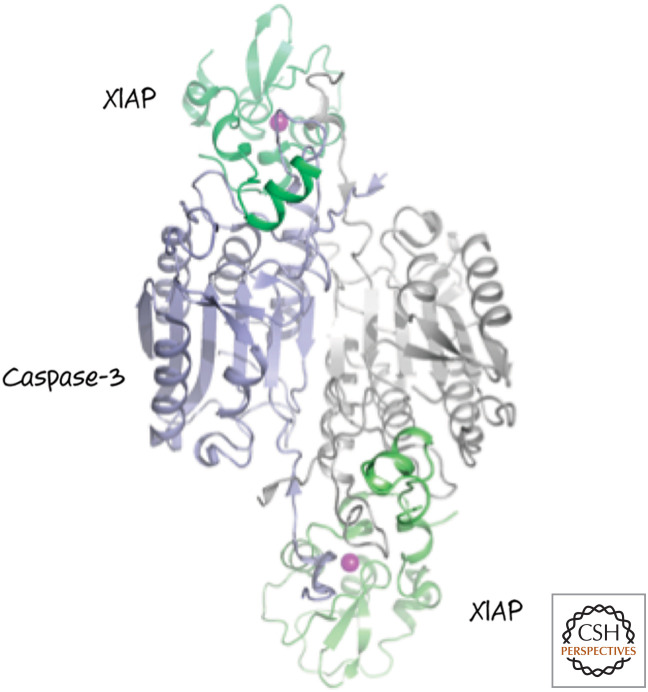

It should be immediately apparent that, of the mammalian IAP proteins, only XIAP is a direct inhibitor of caspases.7 In fact, different regions of the protein inhibit different caspases: BIR3 (and the region adjacent to it, the RING; see Fig. 15) inhibits the initiator caspase-9, whereas BIR2 (and the linker between it and BIR1) inhibits the executioner caspases, caspases-3 and -7. Figure 16 shows the binding of XIAP to caspase-3.

Figure 16.

XIAP binds to the active sites in caspase-3. Only the BIR2 domain in XIAP (green) is shown. (Purple circles indicate zinc atoms that coordinate the folding of XIAP.) (PDB 1I3O [Riedl et al. 2001b].)

In addition to BIR domains, many IAP proteins have another domain, called RING, that functions as an E3-ubiquitin ligase, responsible for putting ubiquitin chains on target proteins and targeting them for degradation by the proteasome or changing their signaling properties. XIAP and DIAP1 cause degradation of caspases by this mechanism.

Is XIAP essential? That is, if it is absent, do caspases spontaneously activate? Mice lacking XIAP have no developmental defects, and so the answer appears to be “no.” However, we will see later (in Green 2022d) an example of XIAP function in apoptosis.

So, we have a mystery: DIAP1 is essential in the control of Drosophila apoptosis, but IAP proteins as inhibitors of caspases do not appear to be crucial in other organisms. Nematodes lack caspase-inhibitory IAP proteins altogether, and XIAP appears, at first pass, to be dispensable, at least in mice. It could be that the control of apoptosis upstream of initiator caspase activation is so tight that control by IAP proteins in most animals is unnecessary. As we delve further into the different apoptotic pathways, we will see why this could be so. Alternatively, there might be caspase inhibitors other than XIAP that we have not discovered or sufficiently appreciated.

At this point, we can begin to piece together what we have discussed so far in terms of caspase activation, inhibition, and apoptosis in animals (see Fig. 17).

Figure 17.

Caspases and IAPs in apoptosis.

OTHER VIRAL INHIBITORS OF CASPASES

Viruses that infect mammalian cells sometimes carry caspase inhibitors, but these are distinct from the IAP proteins. Poxviruses, for example, express inhibitors belonging to the serpin family. Most serpins act as inhibitors of serine proteases (remember that caspases are a different type—cysteine proteases), but some viral serpins instead act as caspase inhibitors. For example, one serpin, CrmA, expressed by cowpox virus, does not inhibit caspase-9 or the executioner caspases in cells, but it is effective in blocking inflammatory caspase-1 and initiator caspase-8, and it also inhibits the serine protease granzyme B (recall that granzyme B is made by cytotoxic lymphocytes and triggers apoptosis in target cells). As we will see, caspase-8 has roles in some immune effector mechanisms, and therefore this inhibitor might function in immune evasion.

In discussing baculovirus, we mentioned that there are actually two different caspase inhibitors that it expresses. In addition to its IAP, baculovirus also makes p35, an inhibitor not found in any form in animals. This protein is remarkably specific for caspases and acts as a caspase substrate. When it is cut, it becomes irreversibly bound to the caspase. Although unique to insect viruses, p35 can effectively inhibit mammalian (and other) caspases, making it useful for experimental purposes.

So, we have reached the point in our discussion where we know how caspases work, what they cut, and how they are inhibited. And to a first approximation, we know that apoptosis is caused by key substrates being cleaved by executioner caspases that are themselves activated when they are cut by initiator caspases. The latter are activated when adapter proteins bring them together so that they activate themselves by “induced proximity.” But what are these adapters and how do they come to engage the initiator caspases? The answer is apoptotic pathways. See Green (2022e) for a discussion of the pathway responsible for most apoptosis occurring in humans (and vertebrates in general)—the mitochondrial pathway.

Footnotes

From the recent volume Cell Death: Apoptosis and Other Means to an End by Douglas R. Green

Additional Perspectives on Cell Death available at www.cshperspectives.org

It is probably not as simple as this. Granzyme B is taken up by target cells, even without perforin, but perforin is necessary for the granzyme to gain access to the cytoplasm.

The molecules from which these particular structures were obtained are FADD (DD and DED), APAF1 (CARD), and NLRP1 (PyD). These molecules are considered in other reviews in this subject collection, but for now the main point is that the different death folds are structurally related.

FLIP is a protein encoded by the gene CFLAR (for “CASP8 and FADD-like apoptosis regulator”) and exists in two isoforms. The protein we are discussing here is the long isoform, c-FLIPL. To keep things simpler, we refer to it as FLIP.

See Footnote 1 in Green (2022a).

There is evidence that caspase-14 has a role in the differentiation of skin.

Caspase-13 is not included in the figure because this caspase turned out to be the bovine homolog of caspase-4.

Some studies suggest that cIAP1, cIAP2, NAIP, and survivin also inhibit caspases. All can associate with some caspases (directly or indirectly) and can ubiquitinate them, which might influence activity and/or turnover. However, none of these is a direct inhibitor of caspases, and any inhibition by these other mechanisms appears to be minor.

ADDITIONAL READING

Mechanisms of Caspase Activation

Fuentes-Prior P, Salvesen GS. 2004. The protein structures that shape caspase activity, specificity, activation and inhibition. Biochem J 384: 201–232.

Pop C, Salvesen GS. 2009. Human caspases: activation, specificity, and regulation. J Biol Chem 284: 21777–21781.

Salvesen GS, Riedl SJ. 2008. Caspase mechanisms. Adv Exp Med Biol 615: 13–23.

Park HH, Lo YC, Lin SC, Wang L, Yang JK, Wu H. 2007. The death domain superfamily in intracellular signaling of apoptosis and inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol 25: 561–586.

An extensive overview of the structures involved in caspase activation. Several of the mechanisms discussed are covered in other reviews in this subject collection.

Induced Proximity

Muzio M, Stockwell BR, Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS, Dixit VM. 1998. An induced proximity model for caspase-8 activation. J Biol Chem 273: 2926–2930.

The original description of induced proximity, applied to caspase-8.

Stennicke HR, Deveraux QL, Humke EW, Reed JC, Dixit VM, Salvesen GS. 1999. Caspase-9 can be activated without proteolytic processing. J Biol Chem 274: 8359–8362.

Boatright KM, Renatus M, Scott FL, Sperandio S, Shin H, Pedersen IM, Ricci JE, Edris WA, Sutherlin DP, Green DR, et al. 2003. A unified model for apical caspase activation. Mol Cell 11: 529–541.

Caspase Activation Cascades

Fernandes-Alnemri T, Armstrong RC, Krebs J, Srinivasula SM, Wang L, Bullrich F, Fritz LC, Trapani JA, Tomaselli KJ, Litwack G, et al. 1996. In vitro activation of CPP32 and Mch3 by Mch4, a novel human apoptotic cysteine protease containing two FADD-like domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci 93: 7464–7469.

One of the first papers to show a caspase activation cascade, with caspase-8 (called Mch4) cleaving and activating caspase-3 (called CPP32) and caspase-7 (called Mch3).

Slee EA, Adrain C, Martin SJ. 1999. Serial killers: ordering caspase activation events in apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 6: 1067–1074.

Slee EA, Harte MT, Kluck RM, Wolf BB, Casiano CA, Newmeyer DD, Wang HG, Reed JC, Nicholson DW, Alnemri ES, et al. 1999. Ordering the cytochrome c–initiated caspase cascade: hierarchical activation of caspases-2, -3, -6, -7, -8, and -10 in a caspase-9-dependent manner. J Cell Biol 144: 281–292.

The order of caspase cleavage following activation of caspase-9 in a cell extract (see Green 2021e for the initial activation mechanism).

IAPs

Salvesen GS, Riedl SJ. 2007. Caspase inhibition, specifically. Structure 15: 513–514.

An overview of IAPs and other intracellular caspase inhibitors.

Silke J, Vaux DL. 2001. Two kinds of BIR-containing protein: inhibitors of apoptosis, or required for mitosis. J Cell Sci 114: 1821–1827.

An important distinction between different IAPs and their functions.

Vaux DL, Silke J. 2005. IAPs, RINGs and ubiquitylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 287–297.

Orme M, Meier P. 2009. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins in Drosophila: gatekeepers of death. Apoptosis 14: 950–960.

Hay BA, Wassarman DA, Rubin GM. 1995. Drosophila homologs of baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis proteins function to block cell death. Cell 83: 1253–1262.

The discovery of IAPs.

Deveraux QL, Takahashi R, Salvesen GS, Reed JC. 1997. X-linked IAP is a direct inhibitor of cell death proteases. Nature 388: 300–304.

The first paper to show that XIAP is a caspase inhibitor.

Riedl SJ, Renatus M, Schwarzenbacher R, Zhou Q, Sun C, Fesik SW, Liddington RC, Salvesen GS. 2001. Structural basis for the inhibition of caspase-3 by XIAP. Cell 104: 791–800.

REFERENCES

*Article is also in this collection.

- *.Green DR. 2022a. Caspases and their substrates. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a041012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Green DR. 2022b. The burial: clearance and consequences. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a041087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Green DR. 2022c. Inflammasomes and other caspase-activation platforms. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a041061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Green DR. 2022d. The death receptor pathway of apoptosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a041053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Green DR. 2022e. The mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis, Part 1: MOMP and beyond. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a041038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

FIGURE CREDITS

- Bleakley RC. 2008. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes. In Fundamental immunology, 6th ed. (ed. Paul WE.), p. 1079. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- Chai J, Wu Q, Shiozaki E, Srinivasula SM, Alnemri ES, Shi Y. 2001. Crystal structure of a procaspase-7 zymogen: mechanisms of activation and substrate binding. Cell 107: 299–407. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00544-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day CL, Dupont C, Lackmann M, Vaux DL, Hinds MG. 1999. Solution structure and mutagenesis of the caspase recruitment domain (CARD) from Apaf-1. Cell Death Differ 6: 1125–1132. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberstadt M, Huang B, Chen Z, Meadows RP, Ng SC, Zheng L, Lenardo MJ, Fesik SW. 1998. NMR structure and mutagenesis of the FADD (Mort1) death-effector domain. Nature 392: 941–945. 10.1038/31972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Alnemri T, Wu J, Yu J-W, Datta P, Miller B, Jankowski W, Rosenberg S, Zhang J, Alnemri ES. 2007. The pyroptosome: a supramolecular assembly of ASC dimers mediating inflammatory cell death via caspase-1 activation. Cell Death Differ 14: 1590–1604. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-Prior P, Salvesen GS. 2004. The protein structures that shape caspase activity, specificity, activation and inhibition. Biochem J 384: 201–232. 10.1042/BJ20041142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiller S, Kohl A, Fiorito F, Herrmann T, Wider G, Tschopp J, Grutter MG, Wuthrich K. 2003. NMR structure of the apoptosis- and inflammation-related NALP1 pyrin domain. Structure 11: 1199–1205. 10.1016/j.str.2003.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Eberstadt M, Olejniczak ET, Meadows RP, Fesik SW. 1996. NMR structure and mutagenesis of the Fas (APO-1/CD95) death domain. Nature 384: 638–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittl PR, Di Marco S, Krebs JF, Bai X, Karanewsky DS, Priestle JP, Tomaselli KJ, Grutter MG. 1997. J Biol Chem 272: 6539–6547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedl S, Bode W, Fuentes-Prior P. 2001a. Structural basis for the activation of human procaspase-7. Proc Natl Acad Sci 98: 14790–14795. 10.1073/pnas.221580098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedl SJ, Renatus M, Schwarzenbacher R, Zhou Q, Sun C, Fesik SW, Liddington RC, Salvesen GS. 2001b. Structural basis for the inhibition of caspase-3 by XIAP. Cell 104: 791–800. 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00274-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SL, Hawkins CJ, Yoo SJ, Müller HAJ, Hay BA. 1999. The Drosophila caspase inhibitor DIAP1 is essential for cell survival and is negatively regulated by HID. Cell 98: 453–463. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81974-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Fox T, Chambers SP, Sintchak J, Coll JT, Golec JM, Swenson L, Wilson KP, Charifson PS. 2000. The structures of caspases-1, -3, -7 and -8 reveal the basis for substrate and inhibitor selectivity. Chem Biol 7: 423–432. 10.1016/S1074-5521(00)00123-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]