Abstract

The VanRS two-component signal transduction pathway from Enterococcus faecium was reconstituted in vitro from partially purified components and shown to be inhibited by the halophenyl isothiazolone LY-266,400, inhibitor A, a compound shown previously to reduce expression of the AlgR1-AlgR2 two-component signal transduction pathway in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (S. Roychoudhury, N. A. Zielinski, A. J. Ninfa, N. E. Allen, L. N. Jungheim, T. I. Nicas, and A. M. Chakrabarty, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:965–969, 1993). Inhibitor A attenuates phosphoryl transfer from VanS∼P to VanR by its action on the ability of VanR to accept. We observed an apparent stimulatory effect of inhibitor A on VanS autophosphorylation which is attributable to the accumulation of VanS∼P as an intermediate unable to transfer Pi to the inhibited VanR. Thus, inhibitor A acts on the second of two sequential steps which lead to transcriptional activation of the VanHAXYZ gene cluster and the resultant expression of vancomycin resistance.

The prevalence of His→Asp two-component signal transduction relays and the diversity of important pathways they regulate justify a search for effectors that act on such systems. For reviews, see references 3, 10, and 16. Despite the importance of these ubiquitous systems, very little is known about specific effectors that can modulate their behavior. The two-component histidine kinase receptor VanS and its response regulator, VanR, are the regulatory elements which control inducible vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium (1, 5, 6, 17); however, molecular details of the mechanism of VanS activation by vancomycin and of possible inducers and modulators which act upon it remain undefined. In vitro measurements of VanS activity (4, 6, 17) have been made by using a chimeric protein consisting of the intracytoplasmic domain of VanS fused at its amino terminus to Escherichia coli maltose binding protein. VanS, however, is an integral membrane protein and is believed to sense the presence of vancomycin, thereby initiating a series of reactions which ultimately confer resistance to vancomycin. On the basis of studies in the prototype EnvZ-OmpR two-component signal transduction system of E. coli (7, 11, 14), one would also expect that the full-length VanS anchored in the cell membrane would therefore be useful to elucidate the mechanism of VanS activation and the action of effectors on the induction of vancomycin resistance. We therefore describe the reconstitution of an active autokinase-phosphotransferase reaction which utilizes full-length VanS interacting with [γ-32P]ATP and purified VanR and the use of the reconstituted system to study the action of effectors on the VanS→VanR, His→Asp phosphorelay system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

Bacterial strains and plasmids which were used in this study are described in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids

| Plasmid or bacterial strain | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmid | ||

| pET23b | Phage T7 RNA polymerase-based protein expression vector | 13, Novagen |

| pET28b | Phage T7 RNA polymerase-based protein expression vector | 13, Novagen |

| pAU111 | pET23b with vanR NdeI-HindIII cassette inserted at the NdeI and HindIII sites in the vector multiple cloning site in frame with the 6 His tag sequence present | This work |

| pAU112 | pET23b with vanS NdeI-BamHI cassette inserted at NdeI and BamHI in the multiple cloning site (no His tag) | This work |

| Bacterial strain | ||

| E. faecium A634 | VanA reference strain, source of vanR, vanS, and vanSc DNA sequence | R. F. Moellering |

| E. coli EAU109 | E. coli BL21DE3-pLysS transformable recipient strain with phage T7 RNA polymerase under the control of LacI and LysS | Novagen |

| EAU110 | E. coli BL21DE3-pLysS + pET23b VanS-negative control strain | This work |

| EAU111 | E. coli BL21DE3-pLysS + pAU111 production strain for VanR | This work |

| EAU112 | E. coli BL21DE3-pLysS + pAU112 production strain for VanS | This work |

Inhibitors.

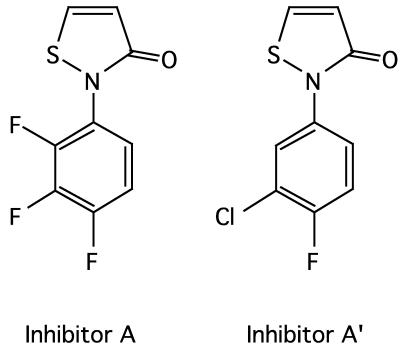

Samples of compounds LY-266,400, 2-(2,3,4-trifluorophenyl)-2,3 dihydrothiazol-3-one, and LY-266,408, 2-(3-chloro, 4-fluorophenyl)-2,3 dihydrothiazol-3-one (inhibitors A and A′, respectively) (12) were gifts from Eli Lilly and Co. (Indianapolis, Ind.). Their structures are shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of inhibitor A along with that of its analog, inhibitor A′.

Plasmid constructions.

Gene cassettes containing the vanR and vanS sequences were constructed by the melt anneal method described by Ulijasz et al. (15) with PCR primers described in Table 2. The resultant cassettes were cloned into pET23b, as indicated, to obtain the strains needed for overproduction of VanR and VanS proteins (13). Overexpressed VanR-6His was purified by immobilized metal (Ni2+) affinity chromatography as described previously (9), whereas full-length VanS, overexpressed in E. coli, was used in the form of washed cell membranes containing VanS as an integral protein and prepared as described previously with slight modifications (11, 14).

TABLE 2.

PCR primersa

| Primer no. | Sequence | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3554 | 5′-TATGAGCGATAAAATACTTATTGTG | VanR forward primer 1 |

| 3546 | 5′-TGAGCGATAAAATACTTATTGTG | VanR forward primer 2 |

| 3545 | 5′-TTTTTTCAATTTTATAACCAAC | VanR reverse primer 1 |

| 3547 | 5′-AGCTTTTTTTCAATTTTATAACCAAC | VanR reverse primer 2 |

| 3305 | 5′-TATGTTGGTTATAAAATTGAAAAA | VanS forward primer 1 |

| 3307 | 5′-TGTTGGTTATAAAATTGAAAAATA | VanS forward primer 2 |

| 4913 | 5′-TTAGGACCTCCTTTTATCAACCAA | VanS reverse primer 1 |

| 4914 | 5′-GATCTTAGGACCTCCTTTTATCAACCAA | VanS reverse primer 2 |

To construct the VanR NdeI-HindIII cloning cassette, two flush amplimers were obtained, with E. faecium A634 DNA used as the template, Pfu DNA polymerase, and primer pairs 3554-3545 and 3546-3547. The two flush amplimers were gel purified, melted, and annealed to produce the desired cloning cassette with NdI- and HindIII-compatible cohesive ends. The VanS cassette was constructed similarly.

Incubation conditions.

(i) VanS autophosphorylation was tested in a 20-μl total volume containing Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 50 mM; MgCl2, 5 mM; KCl, 100 mM; [γ-32P]ATP, 4 μCi or 200 pmol; and E. coli VanS membrane preparation, 0.5 μg of protein. Incubation was at ambient room temperature, 25°C, for 15 min. (ii) The VanRS coupled reaction showing the transfer of 32P from VanS∼P to VanR took place under conditions such as those described in item i, with a 20-μl scale, supplemented with VanR, 1.4 μg of protein. Incubation was at ambient room temperature, 25°C, for 10 min. (iii) To test for reversal of inhibition, the VanRS coupled reaction (20-μl scale) was supplemented with 100 μg of inhibitor A/ml (0.5 mM) and was added as 2 μl of a 10× stock solution which contained 1 mg/ml in 50% dimethylsulfoxide. Incubation was at ambient room temperature, 25°C, for 10 min to allow accumulation of VanS∼P. The inhibited reaction mixture was then supplemented with either VanR, 1.4 μg of protein, or VanS-containing membranes, 0.5 μg of protein, as indicated. Twenty-microliter samples were taken at 1, 3, and 10 min, by which time the transfer to VanR was complete. The 20-μl samples were mixed with 10 μl of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer, and 24 μl of the resulting reaction mixture was fractionated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), followed by Coomassie blue staining. The resultant phosphoprotein-containing bands were quantified with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

RESULTS

Autophosphorylation of VanS.

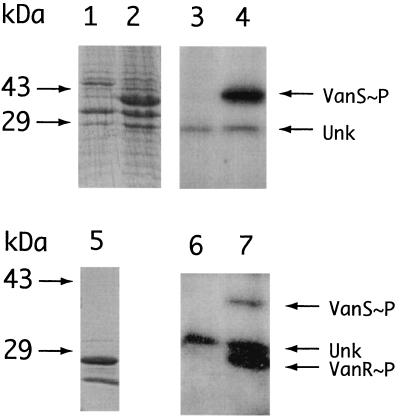

Membrane preparations obtained from E. coli EAU-112 were fractionated by SDS-PAGE, followed by Coomassie blue staining. The results, shown in Fig. 2, lanes 1 and 2, demonstrate the presence of a prominent 39-kDa Coomassie-staining band that was absent in the control membrane sample. When membrane preparations were incubated with [γ-32P]ATP, a strongly-labeled band that was absent in the control was seen; this band comigrated with the prominent VanS-containing 39-kDa Coomassie-staining band (Fig. 2, lanes 3 and 4). 32P incorporated into the 39-kDa band was therefore used as a measure of VanS∼P formation. An unidentified ca. 35-kDa labeled band, further characterized below, was labeled in E. coli membrane preparations irrespective of the presence of VanS. Based on the inhibitor data reported below, we believe that this spurious 35-kDa band protein may have some functional similarity with VanR.

FIG. 2.

VanS, VanR, and their respective phosphorylated forms. Analysis by PAGE and autoradiography of washed membranes from E. coli EAU110, lacking VanS, Coomassie blue stain (lane 1); washed membranes from E. coli EAU112 containing overexpressed VanS, Coomassie blue stain (lane 2); washed membranes from E. coli EAU110, lacking VanS, incubated with [γ-32P]ATP (lane 3); washed membranes from E. coli EAU112 containing VanS, incubated with [γ-32P]ATP (lane 4); purified VanR, Coomassie blue stain (lane 5); purified VanR plus washed membranes from E. coli EAU110 and [γ-32P]ATP (lane 6); and purified VanR plus washed membranes from E. coli EAU112 and [γ-32P]ATP (lane 7). Reaction mixtures were incubated as described in Materials and Methods. See text for a detailed analysis.

Phosphate acceptor activity of VanR-6His.

A recombinant C-terminal His-tagged VanR, VanR-6His, was overexpressed in E. coli EAU-111 and purified by immobilized metal (Ni2+) affinity chromatography. Results of the analytical PAGE, Fig. 2, lane 5, showed a major band of 27 kDa corresponding to VanR and a smaller, faster-running (ca. 25-kDa) component of unknown origin which cofractionated with VanR through the Ni2+ affinity chromatography step. The coupled VanS→VanR reaction required the presence of VanS; no transfer of phosphate was seen if membranes from E. coli EAU-110 (VanS negative) were used, as shown in Fig. 2, lanes 6 and 7. Thus, the labeling of VanR requires VanS and is not mediated by cross talk with contaminating kinases present in the membrane preparation.

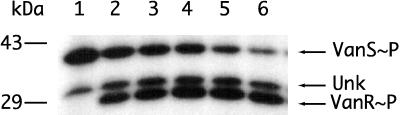

To verify the transfer of phosphate from VanS to VanR, a membrane preparation containing full-length VanS was incubated with [γ-32P]ATP in a series of reaction mixtures containing increasing VanR concentrations. Samples were collected, as indicated previously, and fractionated by PAGE, and label in phosphoprotein-containing bands was measured with the PhosphorImager. The results, shown in Fig. 3, indicate that the recombinant VanR-6His preparation was active in accepting phosphate from VanS∼P. The slower, ca. 35-kDa band appears to be present in all samples irrespective of the presence of VanR, as shown in Fig. 3, lane 1, and is therefore associated with E. coli membranes whether or not they contain VanS. This observation is consistent with the findings shown in Fig. 2, lanes 3 and 4.

FIG. 3.

Transfer of 32P from VanS∼P to VanR. VanS, VanR, and [γ-32P]ATP were incubated, and the amount of 32P contained in VanS and in VanR was measured as a function of increasing VanR concentration. Lanes 1 to 6, respectively, contained no VanR and 0.3, 0.6, 1.2, 3.0, and 6.0 μg of added VanR. A ca. 35-kDa labeled band, labeled Unk and present in all samples, was due to a component present in the E. coli membrane preparation. The Unk component cannot mediate the transfer of 32P to VanR, since the transfer does not occur with membranes which contain this component but lack VanS.

Inhibition of the coupled VanRS system in vitro.

Roychoudhury et al. (12) discovered lead compounds, A and an analog, inhibitor A′, that inhibited several His→Asp phosphorelay signal transduction systems. Inhibitors A and A′ can be classified as halophenyl isothiazolones, and their structures are shown in Fig. 1. The effects of inhibitors A and A′ were tested in the coupled VanRS system. Two effects were noted, shown in Fig. 4. First, an inhibition of VanR phosphorylation, 50% effective dose (ED50), 70 μg/ml (0.35 mM), and second, an apparent parallel accumulation of VanS∼P, suggested that 32P was incorporated into VanS but was not transferred to VanR in the presence of inhibitor A. Inhibitor A′ had an effect similar to that of inhibitor A (data not shown) and was not examined further.

FIG. 4.

Inhibition of 32P transfer from VanS∼P to VanR. The coupled VanRS system was used as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes 1 to 6, respectively, contained 0, 10, 25, 55, 77.5, and 100 μg/ml. A concentration of 100 μg of inhibitor A/ml corresponds to 0.5 mM. Concentrations of inhibitor A above 60 μg/ml (0.3 mM) completely inhibited phosphoryl transfer from VanS∼P to VanR, leading to an apparent accumulation of the former. (Upper panel) VanS∼P and VanR∼P quantified by PhosphorImager analysis. (Lower panel) Autoradiogram corresponding to upper panel. Two components in addition to VanS∼P and VanR∼P were seen in the autoradiogram—one larger than VanS∼P (ca. 45 kDa), which accumulated in response to inhibitor A, and one larger than VanR∼P (ca. 35 kDa), labeled Unk, whose concentration, like that of VanR∼P, was reduced by inhibitor A. The Unk component was shown to be derived from the E. coli membrane preparation and does not play a significant role in the phosphorylation of VanR, as shown in Fig. 2, lanes 6 and 7.

Two other phosphoprotein bands with lower intensity, whose behaviors, respectively, parallel those of VanS and VanR, are also present. One of these, a minor band with mobility corresponding to 43 kDa, accumulates in the presence of inhibitor A in parallel with VanS. The other corresponds to the unidentified 35-kDa band described previously in Fig. 3, labeled Unk, and its presence is inhibited in parallel with VanR. It is possible that the 35- and 43-kDa proteins correspond to contaminating kinase and response regulator proteins, suggesting that inhibitor A may affect other two-component signal transduction systems in a similar way.

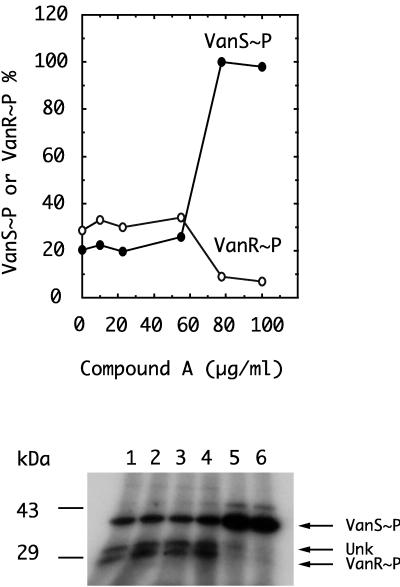

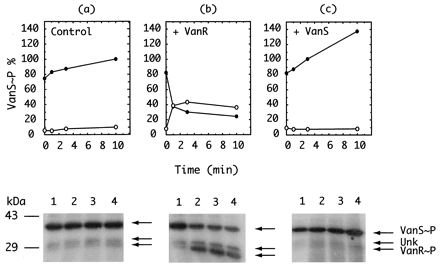

Site of inhibitor action in vitro.

Reduced phosphate transfer from VanS∼P to VanR, shown in Fig. 4, could be due either to inhibition of the donor activity of VanS∼P or to inhibition of the acceptor activity of VanR. To distinguish between these two possibilities, VanS-containing membranes, VanR, and [γ-32P]ATP were incubated in the presence of inhibitor A to accumulate VanS∼P maximally, as described above. The reaction mixture was then supplemented with either VanR or VanS and sampled at 1, 3, and 10 min for determination of the relative amounts of VanS∼P and VanR∼P. Results are shown in Fig. 5. The relative amounts of VanS∼P and VanR∼P remained unchanged in the control reaction mixture over the sampling period in the absence of supplementation, as shown in the control sample (Fig. 5a). The addition of VanR to the reaction mixture resulted in a transfer of label from VanS∼P to VanR, as shown in Fig. 5b, whereas the addition of VanS-containing membranes resulted in the accumulation of additional VanS∼P, as shown in Fig. 5c. These observations suggest that inhibitor A affects the ability of VanR to accept Pi rather than the ability of VanS∼P to transfer Pi.

FIG. 5.

Site of action of inhibitor A. The coupled VanRS reaction was supplemented with 100 μg of inhibitor A per ml and incubated for 15 min to allow maximal accumulation of VanS∼P, as shown in Fig. 4. The reaction mixture was then supplemented either with buffer (a); VanR, 1.4 μg (b); or VanS, 0.5 μg (c). Lanes 1 to 4, respectively, correspond to samples taken at 0, 1, 3, and 10 min, as indicated, and analyzed by PAGE, phosphorimaging, and autoradiography. (Upper panel) Quantification of VanS∼P and VanR∼P as a function of time after addition of buffer control (a), VanR (b), or VanS (c). Phosphoproteins formed in the timed samples were measured as a function of time after supplement was added to a preincubated mixture containing 32P∼VanS, VanR, and inhibitor A. (Lower panel) Autoradiographic analysis of phosphoproteins. The autoradiograms present an image of the phosphoproteins that were quantified above and graphed. Both the unknown band and VanR∼P appear to increase as a function of time. See the text for a discussion of this observation.

The appearance of label in the 35-kDa Unk component present in the VanS-containing membrane preparation is also seen upon the addition of VanR to the inhibited reaction (Fig. 5b). Whether the source of 35-kDa phosphorylation is cross talk with VanS (4, 16) or with some other kinase present in either the VanS or VanR preparation is undetermined. This observation suggests that the action of inhibitor A may affect the ability of other response regulators to accept Pi from VanS or from their respective cognate or noncognate kinases. These results also suggest that inhibitor A has a high dissociation constant and therefore relatively low affinity in its interaction with VanR.

DISCUSSION

We have shown the transfer of Pi from full-length VanS∼P to VanR in vitro and characterized the action of a compound, inhibitor A, which prevents phosphoryl transfer by its action on VanR rather than on VanS. In the course of these studies, two spurious labeled phosphoprotein bands of interest appeared, with 43- and 35-kDa mobility (Fig. 4). In the presence of inhibitor, the phosphorylated 43-kDa component accumulated in parallel with VanS∼P, whereas the phosphorylated 35-kDa component was reduced in parallel with VanR∼P. Moreover, the addition of VanR (but not VanS) to the inhibited reaction restored both VanR∼P and the 35-kDa component. Constituents of other two-component systems present in the E. coli membrane preparations cannot account for the transfer of label from VanS∼P to VanR because the transfer was seen only if the E. coli membranes were prepared from EAU-112, carrying VanS, and not if the E. coli membranes were prepared from EAU-110, which lacks VanS. Thus, cross talk between VanR and an E. coli kinase cannot account for the observed phosphorylation of VanR.

The 35- and 43-kDa spurious bands are of interest because their presence suggests more general action by inhibitor A on other bacterial signal transduction systems. Thus, inhibitor A might recognize a common structural motif present in other response elements, leading to accumulation of the kinases which phosphorylate them. Assuming that the 35-kDa component which originates in the E. coli membrane preparation is a response regulator, the reappearance of both VanR∼P and the 35-kDa band in the inhibited reaction supplemented with VanR (Fig. 5b) suggests that inhibitor A is dissociable from its target and that its inhibitory activity is reversible. The presence of constituents belonging to two-component signal transduction systems other than VanRS thus serves a useful function by providing a parallel test reaction. It would be desirable to reconstitute a more defined system lacking spurious components, and indeed, Jung et al. (8) have reconstituted a purified homogeneous preparation of KdpD, the high-affinity K+-translocating ATPase of E. coli, into liposomes with recovery of autokinase activity. The method of reconstitution appears to be generally applicable.

Inhibitors A and A′ were discovered by Roychoudhury et al. (12) as part of a systematic search for inhibitors of signal transduction that would target aliginate biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Inhibitor A at 0.2 μg/ml (1 μM) was shown to inactivate the algD promoter linked to an xylE reporter. When the phosphorylation of AlgR1-AlgR2 in vitro was tested, it was noted that inhibitors A and A′ inactivated the autokinase activity of AlgR2 (ED50, ca. 2 μg/ml [10 μM]). In contrast, our studies showed that inhibitor A had no effect on the kinase activity of VanS in vitro at these low concentrations, while at higher concentrations (ED50, 70 μg of inhibitor A/ml [350 μM]) it appeared to stimulate phosphorylation of VanS. Differences in ED50 could be due a lack of standardization in the test reactions used to measure the action of inhibitors and the variations in component concentrations; however, we cannot reconcile the effectiveness of inhibitor A in reactions which involve chemically different mechanisms.

The apparent stimulation of VanS phosphorylation was, in fact, an accumulation of VanS∼P owing to the inhibition of VanR to accept Pi. The autoradiogram shown in Fig. 4 suggests that another component, possibly a histidine kinase, shows a similar response to inhibitor A. This observation suggests a possible way to label, selectively, a functionally related set of histidine kinases.

A systematic search for inhibitors of signal transduction reported by Barrett et al. (2) led to a series of antimicrobial tyramine derivatives which inhibited the autokinase activity of a KinA model system. Barrett and Hoch (3) have recently reviewed two-component signal transduction as a target for the discovery of new antiinfective agents. This review includes a list of newer agents which were not covered in their earlier publication (2).

The demonstration of a phosphoryltransferase inhibitor which modifies the ability of VanR to accept Pi from VanS complements the discovery of kinase inhibitors reported in other studies. It will be interesting to learn the structural basis for the interaction of two-component signal transduction systems with the growing list of small-molecule ligands which modulate their activity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rob Giannattasio for expertly generating the figures and Eli Lilly and Co. for compounds LY-266,400 (inhibitor A), LY-266,408 (inhibitor A′), and LY-000051 (inhibitor B).

REFERENCES

- 1.Arthur M, Molinas C, Courvalin P. The VanS-VanR two-component regulatory system controls synthesis of depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursors in Enterococcus faecium BM4147. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2582–2591. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2582-2591.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett J F, Goldschmidt R M, Lawrence L E, Foleno B, Chen R, Demers J P, Johnson S, Kanojia R, Fernandez J, Bernstein J, Licata L, Donetz A, Huang S, Hlasta D J, Macielag M J, Ohemeng K, Frechette R, Frosco M B, Klaubert D H, Whiteley J M, Wang L, Hoch J A. Antibacterial agents that inhibit two-component signal transduction systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5317–5322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett J F, Hoch J A. Two-component signal transduction as a target for microbial anti-infective therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1529–1536. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher S L, Kim S-K, Wanner B L, Walsh C T. Kinetic comparison of the specificity of the vancomycin resistance kinase VanS for two response regulators, VanR amd PhoB. Biochemistry. 1996;35:4732–4740. doi: 10.1021/bi9525435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haldimann A, Fisher S L, Daniels L L, Walsh C T, Wanner B L. Transcriptional regulation of the Enterococcus faecium BM4147 vancomycin resistance gene cluster by the VanS-VanR two-component regulatory system in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5903–5913. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5903-5913.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holman T R, Wu Z, Wanner B L, Walsh C T. Identification of the DNA-binding site for the phosphorylated VanR protein required for vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium. Biochemistry. 1994;33:4625–4631. doi: 10.1021/bi00181a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Igo M M, Ninfa A J, Stock J B, Silhavy T J. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of a bacterial transcriptional activator by a transmembrane receptor. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1725–1734. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.11.1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung K, Tjaden B, Altendorf K. Purification, reconstitution, and characterization of KdpD, the turgor sensor of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10847–10852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kovalic D, Giannattasio R B, Jin H J, Weisblum B. 23S rRNA domain V, a fragment that can be specifically methylated in vitro by the ErmSF (TlrA) methyltransferase. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6992–6998. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.6992-6998.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mizuno T. His-Asp phosphotransfer signal transduction. J Biochem. 1998;123:555–563. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rampersaud A, Utsumi R, Delgado J, Forst S A, Inouye M. Ca2(+)-enhanced phosphorylation of a chimeric protein kinase involved with bacterial signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:7633–7637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roychoudhury S, Zielinski N A, Ninfa A J, Allen N E, Jungheim L N, Nicas T I, Chakrabarty A M. Inhibitors of two-component signal transduction systems: inhibition of alginate gene activation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:965–969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Studier F W, Rosenberg A H, Dunn J J, Dubendorff J W. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tokishita S, Kojima A, Aiba H, Mizuno T. Transmembrane signal transduction and osmoregulation in Escherichia coli. Functional significance of the periplasmic domain of the membrane-located protein kinase, EnvZ. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:6780–6785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ulijasz A T, Grenader A, Weisblum B. A vancomycin-inducible LacZ reporter system in Bacillus subtilis: induction by antibiotics that affect cell wall synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6305–6309. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6305-6309.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wanner B L. Is cross regulation by phosphorylation of two-component response regulator proteins important in bacteria? J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2053–2058. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.7.2053-2058.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wright G D, Holman T R, Walsh C T. Purification and characterization of VanR and the cytosolic domain of VanS: a two-component regulatory system required for vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium BM4147. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5057–5063. doi: 10.1021/bi00070a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]