Abstract

Sequencing of a 4.3-kb DNA region from the chromosome of Streptomyces argillaceus, a mithramycin producer, revealed the presence of two open reading frames (ORFs). The first one (orfA) codes for a protein that resembles several transport proteins. The second one (mtmR) codes for a protein similar to positive regulators involved in antibiotic biosynthesis (DnrI, SnoA, ActII-orf4, CcaR, and RedD) belonging to the Streptomyces antibiotic regulatory protein (SARP) family. Both ORFs are separated by a 1.9-kb, apparently noncoding region. Replacement of the mtmR region by an antibiotic resistance cassette completely abolished mithramycin biosynthesis. Expression of mtmR in a high-copy-number vector in S. argillaceus caused a 16-fold increase in mithramycin production. The mtmR gene restored actinorhodin production in Streptomyces coelicolor JF1 mutant, in which the actinorhodin-specific activator ActII-orf4 is inactive, and also stimulated actinorhodin production by Streptomyces lividans TK21. A 241-bp region located 1.9 kb upstream of mtmR was found to be repeated approximately 50 kb downstream of mtmR at the other end of the mithramycin gene cluster. A model to explain a possible route for the acquisition of the mithramycin gene cluster by S. argillaceus is proposed.

Actinomycetes are producers of a variety of antibiotics and other secondary metabolites. In the last few years many biosynthetic gene clusters have been studied in some detail, leading to the isolation and characterization of many genes involved in antibiotic biosynthesis by actinomycetes. Several pathway-specific regulatory genes have been identified in some of these clusters: redD for the undecylprodigiosin pathway (24), actII-orf4 for the actinorhodin pathway (15), dnrI for the daunorubicin pathway (33), srmR for the spiramycin pathway (16), strR for the streptomycin pathway (10), and ccaR for the cephamycin and clavulanic acid pathways (25). Three of them have been experimentally shown to bind specifically to promoter regions within the corresponding gene clusters: the StrR activator from the streptomycin pathway (28), the DnrI activator from the daunorubicin pathway (34), and the ActII-orf4 activator from the actinorhodin pathway (2). The last two regulators recognize similar DNA sequences.

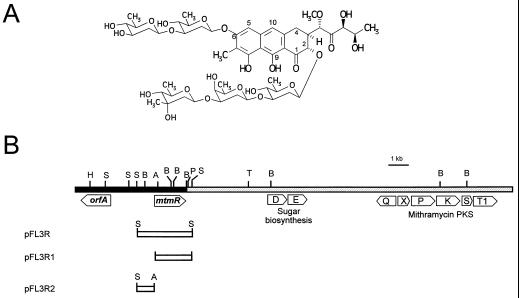

Mithramycin (see Fig. 1A) (also designated aureolic acid, plicamycin, mithracin, LA7017, and A2371) is an antitumor drug, synthesized by different actinomycete species, that belongs to the aureolic acid group of drugs and has clinical application in the treatment of several tumors (27, 32). Structurally, mithramycin is an aromatic polyketide containing a three-ring chromophoric aglycon with a side carbon chain derived from the condensation of ten acetates and a disaccharide (d-olivose-d-olivose) and a trisaccharide (d-olivose-d-oliose-d-mycarose) attached to C-6 and C-2 of the mithramycin aglycon, respectively. Several genes from the mithramycin gene cluster of Streptomyces argillaceus ATCC 12956 have been isolated and characterized, including type II polyketide synthase genes (6, 20), two genes involved in early biosynthesis of the deoxysugars (21), two glycosyltransferases (13), and a mithramycin resistance determinant consisting of an ABC transporter (12).

FIG. 1.

(A) Structure of mithramycin. (B) Schematic representation of the location of mtmR in the chromosome of S. argillaceus with respect to mithramycin sugar biosynthetic genes and the mithramycin polyketide synthase (PKS) genes. The black bar indicates the region sequenced in this paper. pFL3R, pFL3R1, and pFL3R2 represent the inserts in the plasmid constructions used for activation of mithramycin production. The insert in pFL3R1 was generated by PCR amplification (see Materials and Methods). A, Asp700I; B, BamHI; H, HindIII; P, SphI; S, SmaI; T, StuI. Restriction sites A, P, S, and T are not unique sites in the chromosomal region shown.

We report here the cloning, sequencing, inactivation, and expression of another gene from S. argillaceus, mtmR, that encodes a positive regulator of mithramycin biosynthesis. Evidence is also presented showing the existence of a DNA region located upstream of the mtmR gene which is repeated at the other end of the mithramycin gene cluster.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms, culture conditions, and vectors.

S. argillaceus ATCC 12956, a mithramycin producer, was used as the donor of chromosomal DNA. For sporulation, it was grown for 7 days at 30°C on plates containing A medium (12). For protoplast transformation, the organism was grown on R5 solid medium plates (17). Streptomyces coelicolor JF1 (11) and Streptomyces lividans TK21 (17) were used as hosts for gene expression. Escherichia coli XL1-Blue (7) was used as the host for subcloning. Growth in liquid medium was carried out at 37°C on TSB medium (Trypticase soy broth; Oxoid). pUK21 (38) and pUC18 were used as vectors for subcloning in E. coli and for DNA sequencing. pIAGO (1) is pWHM3 (37) containing the promoter of the erythromycin resistance gene (ermE) from Saccharopolyspora erythraea (5). Plasmid pBSKT was constructed by subcloning the thiostrepton resistance cassette (36) as a 1.4-kb SmaI fragment in the unique NaeI site of pBluescript SK(−) (Stratagene).

DNA manipulation and sequencing.

DNA manipulations were according to standard procedures for E. coli (30) and for Streptomyces (17). Southern hybridization was according to standard procedures (17). DNA sequencing was carried out by the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method (31) with Taq polymerase and by using an ALF-express automatic DNA sequencer (Pharmacia). To overcome band compression artifacts, 7-deaza-dGTP was routinely used instead of dGTP (23). Both DNA strands were sequenced with universal primers or with internal oligoprimers (17-mer). Computer-aided database searching and sequence analyses were carried out by using the University of Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group (GCG) programs package (9) and the BLASTP program (1a).

Gene replacement.

For the inactivation of the mtmR gene by gene replacement, a 7.5-kb HindIII-StuI fragment from cosAR13 (Fig. 1B) was subcloned into the HindIII-EcoRV sites of pUK21, generating pFLR. The three internal BamHI fragments (0.6, 0.9, and 0.02 kb; see Fig. 1B) were deleted by digestion with BamHI, thus eliminating the mtmR gene, and replaced by a 1.4-kb BglII-BamHI fragment containing an apramycin resistance cassette (plasmid pFLΔR). The insert in this construction was rescued as an SpeI fragment by using the two SpeI restriction sites at both ends of the pUK21 polylinker and was then subcloned into the same restriction site of plasmid pBSKT. This construction (pFLTΔR) was used to transform S. argillaceus protoplasts and primary transformants selected on R5 agar plates containing 25 μg of apramycin/ml. To verify if the gene replacement event took place, these primary transformants were then tested for their susceptibility to thiostrepton (50 μg/ml).

PCR amplification.

A 0.84-kb fragment containing the mtmR gene was amplified by PCR by using the following primers: (5′) GAGATCTAGAGTCGGAAGGTGTGACAGA (3′) for the 5′-end of the gene and (5′) GAGATCTAGACTACGCCGCGCTCGGCCC (3′) for the 3′-end of the gene (an XbaI site was included in the oligoprimers to facilitate subcloning and is indicated by underscoring). The PCR product was subcloned into the XbaI site of pIAGO in the right orientation.

HPLC analysis.

Production of mithramycin was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of ethyl acetate extracts of cultures of the different strains grown on R5 agar plates containing 50 μg of thiostrepton/ml when appropriate. One-quarter of an R5 agar plate was extracted with 10 ml of ethyl acetate, and after evaporation of the organic solvent, the residue was resuspended in 200 μl of methanol. Aliquots (100 μl) were then analyzed by HPLC in a μBondapak C18 column (Waters) with acetonitrile and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in water as the mobile phase. Elution was carried out with a linear gradient of acetonitrile from 10 to 100% for 30 min, at 1 ml/min. Detection and spectral characterization of peaks were performed with a photodiode array detector (Waters).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 4,346-bp sequence corresponding to the orfA and mtmR genes has GenBank accession no. AF056309, and the 484-bp region containing the repeated sequence has GenBank accession no. AF056310.

RESULTS

The mtmR gene product resembles positive regulators of antibiotic biosynthetic pathways.

From a cosmid library of chromosomal DNA from S. argillaceus, a mithramycin producer, we have previously isolated a family of overlapping clones containing the mithramycin gene cluster. One of these clones, cosAR13, overlapped with cosAR7, from which we have cloned and sequenced a region containing two genes encoding a glucose-1-phosphate:TTP thymidylyl transferase (mtmD) and a TDP-d-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (mtmE) (21). These two enzymes are involved in the early stages of 6-deoxysugar biosynthesis. We have now sequenced, at approximately 3.5 kb upstream of mtmD and mtmE genes, a 4,346-nucleotide DNA region (Fig. 1B). The sequence was analyzed for coding regions by using the CODONPREFERENCE and TESTCODE programs of the GCG package (9). From this analysis the presence of two open reading frames (ORFs) transcribed in opposite and divergent directions was deduced (Fig. 1B). A 1.9-kb, apparently noncoding DNA region was located between the two ORFs.

The first ORF from left to right (designated orfA) comprises 1,242 nucleotides, starting with a GTG codon and ending with a TAG codon; it codes for a polypeptide of 414 amino acids and has an Mr of 44,652. Comparison of the deduced product of orfA with proteins in databases showed similarities with different membrane proteins involved in the transport of proline-betaine in E. coli (33.1% identity) (8), transport of different metabolites in Haemophilus influenzae (35.4% identity) (35), and transport of pthalates in Burkholderia cepacia (37.2% identity) (29).

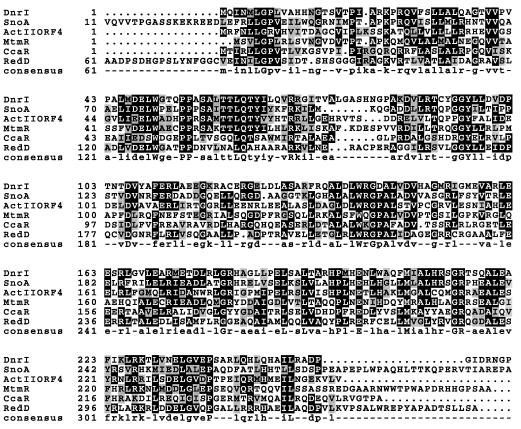

The second ORF (designated mtmR) comprises 831 nucleotides, starting with an ATG codon and ending with a TAG codon. The starting codon of mtmR is preceded by a sequence (AGAA) with a certain degree of complementarity to a region close to the 3′ end of the 16S rRNA of S. lividans (4) that could potentially act as a ribosomal binding site. The overall (62.5%) and third codon position (77.2%) G+C contents of mtmR were lower than those of most Streptomyces genes, i.e., 61 to 79.7% and 76.4 to 98.3%, respectively (40). mtmR contains a large number of codons that are very rare in a G+C-rich organism such as Streptomyces. The presence of two TTA codons could be of particular interest, since their involvement in the regulation of differentiation and secondary metabolism in Streptomyces has been shown (15, 18, 19). The mtmR gene would code for a polypeptide of 276 amino acids with an estimated Mr of 30,705. Comparison of the deduced product of the mtmR gene with proteins in databases showed similarities with different proteins that have been proposed to be activators of antibiotic biosynthesis. The highest scores were with DnrI from the daunorubicin pathway in Streptomyces peucetius (41.9% identity) (33), SnoA from the nogalamycin pathway in Streptomyces nogalater (37.9% identity) (41), ActII-orf4 from the actinorhodin pathway in S. coelicolor (32.9% identity) (15), RedD from the undecylprodigiosin pathway in S. coelicolor (31% identity) (24) and CcaR from the cephamycin and clavulanic acid pathways in Streptomyces clavuligerus (32.4% identity) (25). Also, the mtmR gene product showed similarity with two proteins from Mycobacterium, Cy50.15 (26) and EmbR (3), which are transcriptional activators of different genes. All antibiotic activators described above have been proposed (39) to constitute a family designated Streptomyces antibiotic regulatory proteins (SARPs). Its members contain a region close to the N termini resembling, both in amino acid sequence and predicted secondary structure, the DNA-binding domain at the C terminus of the E. coli activator OmpR (22). The MtmR protein also contains this conserved amino acid region present in both SARPs and OmpR (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the amino acid sequence of MtmR and different SARPs. MtmR, mithramycin positive regulator from S. argillaceus (this work); DnrI, daunorubicin positive regulator from S. peucetius (33); SnoA, nogalamycin positive regulator from S. nogalater (41); ActII-orf4, actinorhodin positive regulator from S. coelicolor (15); RedD, undecylprodigiosin positive regulator from S. coelicolor (24); and CcaR, cephamycin and clavulanic acid positive regulator from S. clavuligerus (25).

Extra copies of mtmR increase mithramycin biosynthesis.

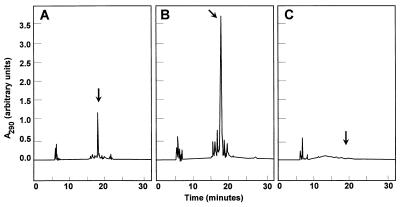

From the above-mentioned similarities, it was presumed that mtmR could code for a positive regulator of mithramycin biosynthesis. We therefore decided to express the gene in a multicopy plasmid and to determine its possible role as a positive regulator in mithramycin production. A 2.5-kb SmaI fragment (containing the mtmR gene) was subcloned into the BamHI site (blunt ended) of pIAGO in the right orientation. The resultant construction (pFL3R) (Fig. 1B) was used to transform S. argillaceus protoplasts, and transformants were selected for thiostrepton resistance. As a control, transformations were also carried out with pIAGO without any insertion. The levels of mithramycin production in each class of transformants were then determined by HPLC after extraction of the cultures with ethyl acetate. The presence of extra copies of mtmR caused a marked increase (16-fold) in mithramycin production compared to that by the control (Fig. 3A and B). The insert in pFL3R (2.5-kb SmaI fragment) comprises the entire mtmR gene and 1,032 bp of the upstream noncoding region. For that reason and to verify if the increase in mithramycin production was due either to the mtmR gene itself or to a possible regulatory role of the upstream noncoding region, we subcloned independently mtmR and the upstream noncoding region. Two new constructions were generated (Fig. 1B): (i) a 0.84-kb XbaI PCR fragment containing the entire mtmR gene subcloned in the XbaI site of pIAGO, generating pFL3R1; and (ii) a 1,252-bp SmaI-Asp700I fragment containing the upstream noncoding region subcloned into the unique BamHI site (blunt-ended) of pIAGO, generating pFL3R2. Both constructions were used to transform S. argillaceus protoplasts, and the levels of mithramycin production by selected transformants generated from each transformation were determined. Stimulation of mithramycin production was observed with pFL3R1 (mtmR gene construction) but not with pFL3R2 (upstream noncoding region) (data not shown), confirming that mtmR was responsible for the increase in mithramycin production.

FIG. 3.

HPLC analysis of mithramycin production by the wild-type S. argillaceus strains containing pIAGO (A) and pFL3R (B) and S. argillaceus M13R1 (C). The arrows indicate the mobility of mithramycin.

Plasmid pFL3R was also used to complement S. coelicolor JF1. This is a mutant in which the ActII-orf4, a positive regulator of actinorhodin biosynthesis, is inactive (11). Transformation of this mutant with pFL3R restored actinorhodin biosynthesis. S. lividans TK21 carries the entire gene cluster for actinorhodin production, but this cluster is not usually expressed under normal growth conditions. When S. lividans TK21 was transformed with pFL3R, actinorhodin production was activated. Similar activation has been described for the use of the actII-orf4 gene from S. coelicolor A3(2) (15). The results of all these experiments suggest that MtmR is a positive regulator of antibiotic biosynthesis.

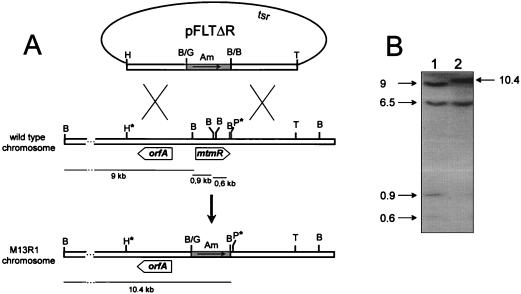

Inactivation of mtmR blocked mithramycin biosynthesis.

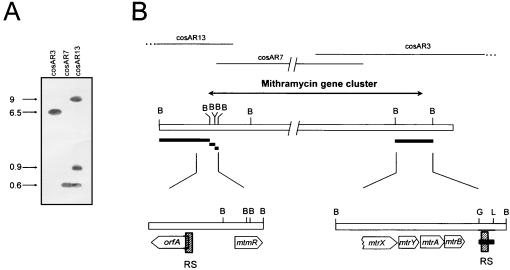

To demonstrate the involvement of mtmR in mithramycin biosynthesis, the gene was deleted by gene replacement. Plasmid pFLTΔR (Fig. 4A) was used to transform S. argillaceus protoplasts, and 38 primary transformants (apramycin-resistant transformants) were obtained. The occurrence of a second crossover in some of these clones was verified by their susceptibility to thiostrepton, and six clones were found to be thiostrepton sensitive (50 μg/ml) as a consequence of a double crossover at both sides of the apramycin resistance cassette. One clone (M13R1) was selected for further analysis. The occurrence of the gene replacement event in M13R1 was verified by Southern analysis (Fig. 4). When a 3.7-kb HindIII-SphI fragment was used as a probe, three expected hybridizing BamHI bands (9, 0.9, and 0.6 kb) were observed (Fig. 4B), while these bands were absent in M13R1 mutant and were replaced by a 10-kb BamHI fragment (Fig. 4B). This confirmed that the mtmR gene had been deleted from the chromosome and replaced by the antibiotic resistance cassette. Interestingly, an additional unexpected hybridizing BamHI band of 6.7 kb was also observed in the chromosome of both the wild-type strain and M13R1 mutant (Fig. 4B) (see below for further details about this band). Ethyl acetate extracts from agar plates from mutant M13R1 were analyzed by HPLC, and neither mithramycin nor mithramycin intermediates were detected (Fig. 3C), indicating that mtmR is essential for mithramycin biosynthesis.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of the gene replacement experiment to generate mutant M13R1. (A) Scheme representing the replacement event in the chromosome of wild-type S. argillaceus strain produced by a double crossover to construct mutant M13R1. The asterisks indicate the ends of the probe used for Southern hybridization (a 3.7-kb HindIII-SphI fragment). The thin lines represent the BamHI hybridizing bands both in the wild type and in the mutant. B, BamHI; G, BglII; H, HindIII; P, SphI; T, StuI. Am, apramycin resistance cassette; tsr, thiostrepton resistance cassette. (B) Southern hybridization by using a 3.7-kb HindIII-SphI fragment as a probe. Lane 1, BamHI-digested chromosomal DNA of the wild-type S. argillaceus strain; lane 2, BamHI-digested chromosomal DNA of M13R1 strain. Sizes of bands in kilobases are indicated on the left and right of the gel.

A 241-bp region located upstream of mtmR is repeated at the other end of the mithramycin gene cluster.

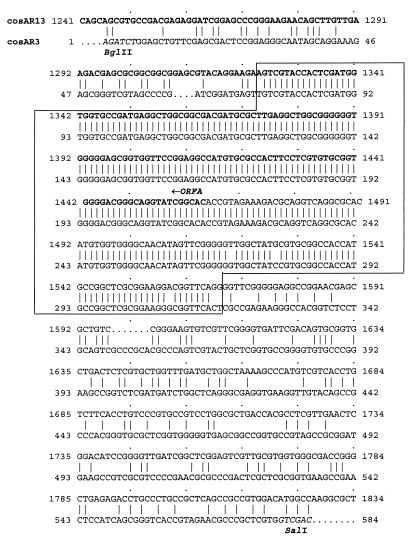

The detection of an extra band in the Southern hybridization mentioned above (Fig. 4B) suggested to us the possible existence of repeated sequences in the mithramycin gene cluster. In our laboratory we have isolated several overlapping cosmid clones containing a DNA region from S. argillaceus of approximately 80 kb, in which we have identified 34 genes that probably encode the entire mithramycin gene cluster. Data for 14 of these genes have been published (12, 13, 20, 21). To test if this repeated sequence was located within the mithramycin gene cluster, a Southern analysis with the same probe (the 3.7-kb HindIII-SphI fragment) against BamHI digestions of the different overlapping cosmid clones containing the mithramycin gene cluster was carried out (Fig. 5). cosAR7 contains most of the genes of the central region of the cluster, while cosAR13 and cosAR3 contain the genes located at the left- and right-hand sides of the cluster (Fig. 5B). cosAR3 showed a 6.5-kb BamHI hybridizing band under high-stringency conditions (Fig. 5A). This clone (cosAR3) had been isolated by conferring resistance to mithramycin when expressed in Streptomyces albus, and from this clone an ABC transporter system that was located within the 6.5-kb BamHI fragment was cloned and sequenced (12). Further subcloning and Southern analysis reduced the hybridizing region to a 0.6-kb BglII-SalI fragment located approximately 800 bp downstream of the mtrB gene (Fig. 5B). mtrB is the last gene at the right-hand side of the mithramycin gene cluster and is approximately 50 kb apart from mtmR. The DNA sequence of the 0.6-kb BglII-SalI fragment was determined and compared with that of the 4.3-kb previously sequenced fragment described above. Interestingly, a nearly perfect 241-bp identical region (with only three mismatches) was found between a sequence located within the 0.6-kb BglII-SalI fragment and a DNA sequence located 1,851 bp upstream of mtmR (Fig. 6). A detailed analysis of the location of this sequence around the mtmR gene region showed that it is formed by 139 bp of the 5′ end of orfA and 102 bp of the region immediately upstream of orfA (Fig. 6). Consequently, the mithramycin gene cluster is flanked upstream of mtmR and downstream of mtrB by two direct repeated sequences (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

(A) Southern hybridization of overlapping cosmid clones containing the mithramycin gene cluster by using the 3.7-kb HindIII-SphI fragment as a probe. Plasmid DNAs from cosAR3, cosAR7, and cosAR13 were digested with BamHI. Sizes of bands in kilobases are indicated on the left of the gel. (B) Schematic representation of the mithramycin gene cluster showing the locations of the repeated sequences (RS) at both ends of the cluster. B, BamHI; G, BglII; L, SalI. The black bars indicate the hybridizing bands formed against the probe, the 3.7-kb HindIII-SphI fragment. The shaded rectangles indicate the locations of the direct repeated sequences. cosAR13, cosAR7, and cosAR3 correspond to three cosmid clones comprising the mithramycin gene cluster.

FIG. 6.

Alignment of the DNA sequences of the 0.6-kb BglII-SalI fragment from cosAR3 and the homologous region from the 4.3-kb sequence located in cosAR13 around orfA and mtmR. The sequences were compared by using the GAP program (9). The coding sequence of orfA is indicated in bold letters. The sequence that is identical in both DNA regions is enclosed within a frame.

DISCUSSION

Sequencing of the left-hand side of the mithramycin gene cluster revealed the presence of a gene, mtmR, that very possibly plays a role as an activator for mithramycin biosynthesis in S. argillaceus. Several lines of evidence support this role: (i) comparison of MtmR with proteins in databases shows that MtmR resembles different positive regulators of the SARP family which are involved in antibiotic biosynthesis, (ii) deletion of mtmR completely blocked the production of mithramycin or any intermediates, (iii) the presence of extra copies of mtmR in the producer strain produced a 16-fold increase in mithramycin biosynthesis, and (iv) mtmR was able to complement a mutation in the actinorhodin-specific activator actII-orf4 gene and activated actinorhodin biosynthesis in S. lividans TK21. Based on protein similarity, DnrI is the closest homologue regulatory protein to MtmR. DnrI has been described as a daunorubicin transcriptional activator in S. peucetius (34). Through DNA-binding and DNase I footprinting assays it was also shown that DnrI binds specifically to DNA fragments containing promoter regions in the daunorubicin gene cluster. Interestingly, these binding sites contain imperfect inverted repeat sequences (6 to 10 bp) with a 5′-TCGAG-3′ consensus sequence (34). This consensus sequence forms part of a heptameric direct repeat unit present two to three times in the promoter regions of the daunorubicin and actinorhodin biosynthetic gene clusters (34, 39). Evidence is also available for the interaction between the ActII-orf4 regulatory protein and these sequences (2). We have examined the DNA sequences around putative promoter regions in the mithramycin gene cluster, and we found that the TCGAG consensus sequence is also present in most of the DNA regions examined, including the regions (i) between the divergent mtmQ (aromatase) and mtmX (cyclase) genes (20), (ii) between the mtmZ (thioesterase) and mtmA (S-adenosylmethionine synthase) genes (14), (iii) preceding the mtrA (export ATP-binding protein) gene (12), and (iv) between the divergent mtmV (2,3-dehydratase in sugar biosynthesis) and mtmW (2,3-reductase in sugar biosynthesis) genes (14). This indicates that the TCGAG consensus sequence is present in promoter regions from at least three antibiotic biosynthetic gene clusters (daunorubicin, actinorhodin, and mithramycin), all of them containing positive regulators of the SARP family, and that possibly MtmR could act as a transcriptional activator in mithramycin biosynthesis in a manner similar to DnrI and ActII-orf4.

Upstream of mtmR there is another gene, orfA, that is transcribed divergently from mtmR. Both genes are separated by a long, apparently noncoding region (1.9 kb). Within this region and partially overlapping the 5′ end of orfA, there is a 241-bp DNA region that is also present at the other end of the mithramycin gene cluster. These sequences are direct repeated sequences (RS) and are probably located outside of the mithramycin gene cluster. Based on the existence and location of these two RS, a hypothetical model is proposed to explain how S. argillaceus could acquire the mithramycin gene cluster through evolution. The mithramycin gene cluster could have been part of a circular extrachromosomal element in which a copy of the RS would be present between mtrB and mtmR genes. Through Campbell recombination to an identical RS present in the chromosome of an ancestor non-mithramycin-producing strain of S. argillaceus, the extrachromosomal element could have been incorporated into the S. argillaceus chromosome. This event would have resulted in the acquisition of the mithramycin gene cluster by S. argillaceus, and as a consequence, two RS would now be flanking the mithramycin cluster.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the European Community (BIO4-CT96-0068) and by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science through the Plan Nacional en Biotecnologia (BIO94-0037 and BIO97-0771).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguirrezabalaga, I. Unpublished data.

- 1a.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arias, P., M. A. Fernández-Moreno, and F. Malpartida. Personal communication.

- 3.Belanger A E, Besra G S, Ford M E, Mikusova K, Belisle J T, Brennan P J, Inamine J M. The embAB genes of Mycobacterium avium encode an arabinosyl transferase involved in cell wall arabinan biosynthesis that is the target for the antimycobacterial drug ethambutol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11919–11924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bibb M J, Cohen S N. Gene expression in Streptomyces: construction and application of promoter-probe plasmid vectors in Streptomyces. Mol Gen Genet. 1982;187:265–277. doi: 10.1007/BF00331128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bibb M J, Janssen G R, Ward J M. Cloning and analysis of the promoter region of the erythromycin resistance gene (ermE) of Streptomyces erythraeus. Gene. 1985;38:215–226. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanco G, Fu H, Méndez C, Khosla C, Salas J A. Deciphering the biosynthetic origin of the aglycone of the aureolic acid group of anti-tumor agents. Chem Biol. 1996;3:193–196. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bullock W O, Fernández J M, Short J N. XL1-Blue: a high efficiency plasmid transforming recA Escherichia coli strain with beta-galactosidase selection. BioTechniques. 1987;5:376. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Culham D E, Lasby B, Marangoni A G, Milner J L, Steer B A, Nues R W, Wood J M. Isolation and sequencing of Escherichia coli gene proP reveals unusual structural features of the osmoregulatory proline/betaine transporter ProP. J Mol Biol. 1993;229:268–276. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Distler J, Ebert A, Mansouri K, Pissowotzki K, Stockmann M, Piepersberg W. Gene cluster for streptomycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces griseus: nucleotide sequence of three genes and analysis of transcriptional activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:8041–8056. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.19.8041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feitelson J S, Hopwood D A. Cloning of a Streptomyces gene for an O-methyltransferase involved in antibiotic biosynthesis. Mol Gen Genet. 1983;190:394–398. doi: 10.1007/BF00331065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernández E, Lombó F, Méndez C, Salas J A. An ABC transporter is essential for resistance to the antitumor agent mithramycin in the producer Streptomyces argillaceus. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;251:692–698. doi: 10.1007/BF02174118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernández E, Weißbach U, Sánchez Reillo C, Braña A F, Méndez C, Rohr J, Salas J A. Identification of two genes from Streptomyces argillaceus encoding two glycosyltransferases involved in transfer of a disaccharide during biosynthesis of the antitumor drug mithramycin. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4929–4937. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.18.4929-4937.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernández-Lozano, M. J. Unpublished results.

- 15.Fernández-Moreno M A, Caballero J L, Hopwood D A, Malpartida F. The act cluster contains regulatory and antibiotic export genes, direct targets for translational control by the bldA tRNA gene of Streptomyces. Cell. 1991;66:769–780. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90120-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geistlich M, Losick R, Turner J R, Rao N R. Characterization of a novel regulatory gene governing the expression of a polyketide synthase gene in Streptomyces ambofaciens. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2019–2029. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hopwood D A, Bibb M J, Chater K F, Kieser T, Bruton C J, Kieser H M, Lydiate D J, Smith C P, Ward J M, Schrempf H. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces. A laboratory manual. Norwich, England: The John Innes Foundation; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawlor E J, Baylis H A, Chater K F. Pleiotropical, morphological and antibiotic deficiencies result from mutations in a gene encoding a tRNA-like product in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Genes Dev. 1987;1:1305–1310. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.10.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leskiw B K, Lawlor E J, Fernández-Abalos J M, Chater K F. TTA codons in some genes prevent their expression in a class of developmental, antibiotic-negative, Streptomyces mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:184–189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lombó F, Blanco G, Fernández E, Méndez C, Salas J A. Characterization of Streptomyces argillaceus genes encoding a polyketide synthase involved in the biosynthesis of the antitumor mithramycin. Gene. 1996;172:87–91. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lombó F, Siems K, Braña A F, Méndez C, Bindseil K, Salas J A. Cloning and insertional inactivation of Streptomyces argillaceus genes involved in earliest steps of sugar biosynthesis of the antitumor polyketide mithramycin. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3354–3357. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3354-3357.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez-Hackert E, Stock A M. The DNA-binding domain of OmpR: crystal structures of a winged helix transcription factor. Structure. 1997;15:109–124. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mizusawa S, Nishimura S, Seila F. Improvement of the dideoxy chain termination method of DNA sequencing by the dideoxy-7-deazaguanosine triphosphate in place of dGTP. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:1319–1324. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.3.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Narva K E, Feitelson J S. Nucleotide sequence and transcriptional analysis of the redD locus of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Bacteriol. 1990;172:326–333. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.326-333.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pérez-Llarena F J, Liras P, Rodríguez García A, Martín J F. A regulatory gene (ccaR) required for cephamycin and clavulanic acid production in Streptomyces clavuligerus: amplification results in overproduction of both β-lactam compounds. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2053–2059. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.6.2053-2059.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Philipp W J, Poulet S, Eiglmeier K, Pascopella L, Balasubramanian V, Heym B, Bergh S, Bloom B R, Jakobs W R, Cole S T. An integrated map of the genome of the tubercle bacillus Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv, and comparison with Mycobacterium leprae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3132–3137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Remers W A. The chemistry of antitumor antibiotics. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Interscience; 1979. pp. 133–175. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Retzlaff L, Distler J. The regulator of streptomycin gene expression, StrR, of Streptomyces griseus is a DNA binding activator protein with multiple recognition sites. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:151–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18010151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saint C P, Romas P. 4-Methyl phthalate catabolism in Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia Pc701: a gene encoding a phthalate-specific permease forms part of a novel gene cluster. Microbiology. 1996;142:2407–2418. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-9-2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain- terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skarbek J D, Speedie M K. Antitumor antibiotics of the aureolic acid group: chromomycin A3, mithramycin A, and olivomycin A. In: Aszalos A, editor. Antitumor compounds of natural origin: chemistry and biochemistry. 8th ed. Vol. 1. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1981. pp. 191–235. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stutzman-Engwall K J, Otten S L, Hutchinson C R. Regulation of secondary metabolism in Streptomyces spp. and overproduction of daunorubicin in Streptomyces peucetius. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:144–154. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.144-154.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang L, Grimm A, Zhang Y X, Hutchinson C R. Purification and characterization of the DNA-binding protein DnrI, a transcriptional factor of daunorubicin biosynthesis in Streptomyces peucetius. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:801–813. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tatusov R, Mushegian A R, Bork P, Brown N P, Hayes W S, Borodovsky M, Rudd K E, Koonin E V. Metabolism and evolution of Haemophilus influenzae deduced from a whole-genome comparison with Escherichia coli. Curr Biol. 1996;6:279–291. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00478-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson C J, Kieser T, Ward J M, Hopwood D A. Physical analysis of antibiotic-resistance genes from Streptomyces and their use in vector construction. Gene. 1982;20:51–62. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vara J, Lewandowska-Skarbek M, Wang Y-G, Donadio S, Hutchinson C R. Cloning of genes governing the deoxysugar portion of the erythromycin biosynthesis pathway in Saccharopolyspora erythraea (Streptomyces erythreus) J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5872–5881. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.5872-5881.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vieira J, Messing J. New pUC-derived cloning vectors with different selectable markers and DNA replication origins. Gene. 1991;100:189–194. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90365-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wietzorrek A, Bibb M J. A novel family of proteins that regulates antibiotic production in streptomycetes appears to contain an OmpR-like DNA-binding fold. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:1177–1184. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5421903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wright F, Bibb M J. Codon usage in the G+C-rich Streptomyces genome. Gene. 1992;113:55–65. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90669-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ylihonko K, Hakala J, Jusilaa S, Cong L, Mäntsälä P. A gene cluster involved in nogalamycin biosynthesis from Streptomyces nogalater: sequence analysis and complementation of early blocked mutants of the anthracycline pathway. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;251:113–120. doi: 10.1007/BF02172908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]