Abstract

Pilus-mediated adhesion is essential in the pathogenesis of Neisseria meningitidis (MC) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC). Pili are assembled from a protein subunit called pilin. Pilin is a glycoprotein, and pilin antigenic variation has been shown to be responsible for intrastrain variability with respect to the degree of adhesion in both MC and GC. In MC, high-adhesion pilins are responsible for the formation of bundles of pili which bind bacteria and cause them to grow as colonies on infected monolayers. In this work, we selected MC and GC pilin variants responsible for high and low adhesiveness and introduced them into the other species. Our results demonstrated that a given pilin variant expressed an identical phenotype in either GC or MC with respect to bundling and adhesiveness to epithelial cells. However, the production of truncated soluble pilin (S pilin) was consistently more abundant in GC than in MC. In the latter species, the glycosylation of pilin at Ser63 was shown to be required for the production of a truncated monomer of S pilin. In order to determine whether the same was true for GC, we engineered various pilin derivatives with an altered Ser63 glycosylation site. The results of these experiments demonstrated that the production of S pilin in GC was indeed more abundant when pilin was posttranslationally modified at Ser63. However, nonglycosylated variants remained capable of producing large amounts of S pilin. These data demonstrated that for GC, unlike for MC, glycosylation at Ser63 is not required for S-pilin production, suggesting that the mechanisms leading to the production of S pilin in GC and MC are different.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC) and Neisseria meningitidis (MC) are pathogens belonging to the same genospecies (4). They both have type IV pili, which are essential in virulence, promoting bacterial interactions with eucaryotic cells (15, 28). Pili are filamentous structures on bacterial surfaces and are assembled from a protein subunit designated PilE or pilin. Besides that of pilin, the expression of one of the PilC proteins is required for piliation (8). There are two PilC proteins, designated PilC1 and PilC2. These proteins are highly homologous and are found in both pili and outer membranes (8, 21, 22). PilC proteins play an important role in bacterial adhesiveness and are considered to be tip-located adhesions (22). In GC, these proteins have similar functions in piliation and adhesion, and PilC1+ PilC2− and PilC1− PilC2+ strains have similar phenotypes. In MC, only PilC1 is capable of promoting adhesion and piliation, whereas PilC2+ PilC1− strains are piliated but are incapable of pilus-mediated adhesion. The reasons why PilC1− PilC2+ MC isolates are nonadhesive remain unknown.

MC produces two types of pilin. Class I pilins are recognized by their ability to bind monoclonal antibody SM1, which reacts with an epitope localized in the constant region, as described by Virji et al. (29), while class II pilins are not. MC class I pilins show extensive homology with GC pilins (20). In both species, pilin undergoes antigenic variation (6, 18), and pilin antigenic variation has been shown to modulate bacterial adhesiveness (11, 16, 23, 30). In MC, high-adhesion pilin variants are responsible for the formation of large bundles of pili (13) which bind bacteria and cause them to grow as colonies on infected monolayers. On the other hand, strains expressing low-adhesion variants have long flexible pili which do not form bundles, and bacteria grow as isolated diplococci on the surface of cell monolayers. In GC, the mechanism by which pilin antigenic variation modulates bacterial adhesiveness has not yet been explored.

As for all type IV pilins, the product of the pilE gene is a precursor that is processed at a highly conserved consensus cleavage site, located close to the N terminus. This cleavage, which removes 7 amino acids, requires the product of the pilD gene, a prepilin peptidase. Some pilin variants are processed at an additional cleavage site, at which 39 amino acids are removed from the N terminus. These latter truncated forms of pilin, designated soluble pilin (S pilin), are not assembled into pili and are secreted into the surrounding media. Strains expressing such variants are poorly piliated and subsequently poorly adhesive (5).

Recently, MC and GC pili were found to be glycosylated. Atomic resolution of the structure of a GC pilin revealed that galactose-α-1,3-N-acetylglucosamine was O linked to Ser63 (19). On the other hand, Stimson et al. (26) showed that an O-linked trisaccharide was present between amino acid residues 45 and 73 of MC pilin. This structure contains a terminal 1,4-linked digalactose covalently linked to a 2,4-diacetamido-2,4,5-trideoxyhexose (26). Recently, by use of a class I pilin MC strain, evidence that galactose-α-1,3-N-acetylglucosamine was O linked to Ser63 was obtained. This finding demonstrates that the difference in glycosylation patterns is not an intrinsic difference between MC and GC, since a strain-to-strain difference exists among MC strains. By engineering pilin variants with altered Ser63 glycosylation sites, we demonstrated that glycosylation is required for the production of S pilin in MC (14). However, a similar role for glycosylation in GC has not been reported.

In this work, pilin variants responsible for high and low adhesiveness and initially obtained from MC were introduced into GC and vice versa. Our data demonstrated that a defined pilin variant was responsible for the same pilus morphology and the same adhesive phenotype in both MC and GC. However, the amount of S pilin produced by the variant was always more abundant in GC than in MC. Construction of various derivatives with modified Ser63 glycosylation sites confirmed that a posttranslational modification at Ser63 increased the production of S pilin in both GC and MC. However, nonglycosylated variants remained capable of producing S pilin in GC but not in MC. Taken together, these data demonstrate that the mechanisms which lead to the production of S pilin are different in these pathogenic neisseriae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and oligonucleotides.

Strain 8013 is an encapsulated serogroup C class I MC strain (17). FA1090 and MS11 are previously described GC strains (2, 27). Variants of these strains are shown Table 1. The SA(Ser62Ala-Ser63Ala) pilin has been previously described. This variant, in which Ser62 and Ser63 of SA are replaced by two Ala residues, is nonglycosylated (14).

TABLE 1.

N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae strains used in this work

| Straina | Variant | PilC Opa phenotypeb | Adhesivenessc | Bundle formationd | Soluble piline | Pilin sequence accession no. | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clone 12 | SB | PilC+ Opa− | 0.20 (high) | + | − | S34940 | 16 |

| Clone 3L2 | SC | PilC+ Opa− | 0.05 (low) | − | − | S34941 | 16 |

| Clone 4 | SA | PilC+ Opa− | 0.015 (low) | − | + | S34939 | 14 |

| MS11-308 | 308 | PilC+ | 0.19 (high) | + | − | AF042097 | This work |

| FA1090-RM11 | RM11 | PilC+ Opa+ | 0.046 (low) | − | + | U58840 | 12 |

| 8013 pilE::Km | PilC+ Opa− | 0.00005 (low) | − | 16 | |||

| FA1090 pilE::Km | PilC+ Opa+ | 0.005 (low) | − | This work |

Clones 12, 3L2 and 4 are derivatives of 8013, a serogroup C MC strain. They express the SB, SC, and SA class I pilin variants, respectively. MS11-308 is a derivative of GC strain MS11 expressing pilin variant 308. FA1090-RM11 is a derivative of GC strain FA1090 expressing pilin variant RM11. 8013 pilE::Km and FA1090 pilE::Km are nonpiliated mutants of 8013 and FA1090, respectively.

Expression of PilC and/or Opa was assessed by performing Western blotting on total protein extracts. The Opa phenotype of MS11-308 was not determined.

Ratio of cell-associated CFU to CFU in the supernatant after 4 h of incubation. Low-adhesion strains were defined as having a ratio of ≤0.05. The adhesiveness of strains expressing high-adhesion variants was at least four to five times higher than that of strains expressing low-adhesion variants.

Assessed by transmission electron microscopy. +, bundles; −, no bundles.

Detected as described in Materials and Methods. +, detected; −, not detected.

GC and MC strains were routinely grown on GCB (Difco) agar containing the supplements described by Kellog et al. (9). All experiments performed throughout this work were done with overnight cultures from frozen stocks. Strains 8013 and FA1090 were transformed by previously described techniques (16). Kanamycin was used at a concentration of 100 μg/ml for selection of both MC and GC.

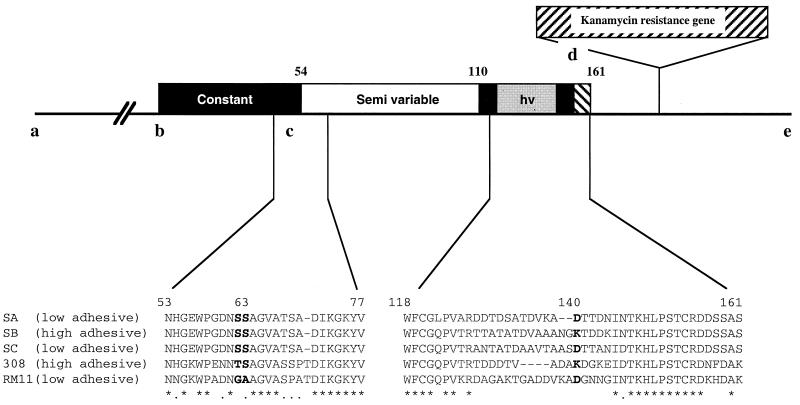

The sequences of oligonucleotides PILEM1, PILEM2, and KM5 were 5′-CCCTTATCGAGCTGATGATTG-3′, 5′-CAGCCAAAACGGACGACCCC-3′, and 5′-GGAGACATTCCTTCCGTATC-3′, respectively. The complementary oligonucleotides 11GAS+ (5′-CCCGCCGACAACAGTTCTGCCGGCGTGGCA-3′) and 11GAS− were designed in order to replace Gly62 and Ala63 of RM11 pilin with two Ser residues and correspond to the coding and noncoding strands, respectively. The sequences of oligonucleotides PILEM3ECO and PILEM2ECO are 5′-GCGAATTCACCGACCCAATCAACACACCCG-3′ and 5′-CGGAATTCAGCCAAAACGGACGACCCC-3′, respectively. The locations of these oligonucleotides on the pilE gene are shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Organization of the pilE locus of GC and class I MC strains. Residues 1 to 53 of the mature pilin correspond to the constant region, and residues 54 to 161 correspond to the variable and hypervariable (hv) regions. Black boxes indicate the locations of the conserved regions. pilE::km fusion constructs were obtained as previously described (13, 14, 16). Oligonucleotide PILEM3ECO anneals to a segment located upstream of the pilE promoter (region a). Oligonucleotide PILEM1 is in region b. Oligonucleotides PILEM2 and PILEM2ECO are in region e, and KM5 is in region d. The mutagenizing oligonucleotides (11GAS+ and 11GAS−) are in region c. The detail of the sequence between residues 53 and 77 demonstrated the existence of a Ser at positions 62 and 63 for SA, SB, and SC and at position 63 for 308. Ser63 is known to be O linked to a carbohydrate residue in both species. No Ser63 was present in the RM11 pilin variant. The detail of the sequence of the C-terminal region (residues 118 to 161) showed that at position 140, there is a Lys in variants responsible for bundling and high adhesion (SB and 308) and a Glu in variants responsible for low adhesion (SA, SC, and RM11) (13). Asterisks indicate conserved residues. The figure is not drawn to scale.

Construction of pilE::Km transcriptional fusions and site-directed mutagenesis.

Standard molecular biology techniques were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (24). The construction of the pilE::Km fusions has already been described (16). They contained the following fragments, from 5′ to 3′: (i) the pilin open reading frame, (ii) the fragment carrying the aph3′ kanamycin resistance gene lacking its own promoter, (iii) the neisserial DNA uptake sequence, and (iv) a 120-bp sequence corresponding to the fragment located downstream of the meningococcal pilE stop codon. PilE− mutants of GC and MC were obtained by transforming a construction containing a truncated pilin open reading frame fused to aph3′.

The pilE::Km fusions were introduced by transformation into 8013 (clone 12) and the derivative of FA1090 expressing the RM11 pilin variant. Kmr transformants arising by recombination with the pilE locus were selected, and transformants expressing the appropriate variants were chosen by sequencing of the pilE locus. Chromosomal DNA of these transformants was retransformed into FA1090 and 8013 (clone 12). Pools of about 1,000 Kmr colonies were then frozen. All biological assays were performed with these pools in order to eliminate the possibility of phenotypic change due to variation of a bacterial component other than pilin.

For expression in E. coli, the pilin from the above transformants was first amplified between PILEM3ECO and PILEM2ECO and cloned into the EcoRI site of pBR325 before being introduced into strain MC1061.

Site-directed mutagenesis of RM11 pilin was performed by PCR overlap extension (7) with oligonucleotides PILEM1 and PILEM2 and a set of two mutagenizing oligonucleotides (11GAS+ and 11GAS−). Mutagenesis was performed as previously described (13, 14). The template was total DNA of clone 12 expressing the RM11::Km variant.

Protein preparation, antibodies, and immunoblots.

Whole-cell lysates were denatured and electrophoresed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) by standard protocols (10). Monoclonal antibody 5C5 recognizes a conserved epitope in the constant region of class I pilin (14). Polyclonal anti-PilC antiserum was a gift from A.-B. Jonsson (15). Monoclonal antibody 4B12, recognizing Opa proteins, was a gift from M. Blake (1).

Cell culture and adherence assays.

Assays were performed a minimum of three times for each strain with Hec-1B epithelial cells as previously described (16). Bacterial overnight cultures were resuspended in cell culture media at a density of 106 CFU ml−1. Wells containing Hec-1B cells were incubated at 37°C with 1 ml of bacterial suspension under 5% CO2. After 4 h of incubation, the number of CFU present in the supernatant was determined. Each well was then washed three times, the mammalian cells were lifted off the plates, and the number of bacteria associated with the mammalian cells was calculated by serial dilution. Adhesiveness was determined as the ratio of cell-associated CFU to CFU in the supernatant. Low-adhesion strains were defined as having a ratio of ≤0.05. The adhesiveness of strains expressing high-adhesion variants was at least four to five times higher than that of strains expressing low-adhesion variants.

Monitoring of piliation status by electron microscopy.

Bacteria were grown overnight on GCB agar plates without antibiotics, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline at a density of 106 CFU ml−1, adsorbed to carbon Formvar-coated nickel grids, and washed several times with water. After being stained with 2% uranyl acetate for 1 min, the samples were viewed and photographed.

Quantification of pilin amounts by density analysis.

In order to appreciate the respective amounts of S pilin and full-length monomer produced by each variant, Western blot membranes were scanned, and one-dimensional densitometry analysis was performed on a Macintosh G3 computer with the public-domain NIH Image application (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/). The ratio, designated RS, corresponding to S pilin divided by total pilin (i.e., S pilin plus full-length pilin) was determined. For each variant, this ratio was obtained from at least four different experiments performed with various protein concentrations.

RESULTS

Interspecies exchanges of the pilE gene.

In a first set of experiments, defined pilin variants isolated from MC or GC and responsible for high and low adhesiveness were introduced into the species that they had not originated from. SB, SA, and SC pilins were obtained from variants of MC strain 8013 (Table 1), an encapsulated serogroup C class I strain. In 8013, SB pilin is responsible for high adhesiveness, whereas SA and SC pilins are associated with low adhesiveness. MC isolates producing the SA variant have been shown to release S pilin in addition to full-length mature pilin (14). In previous work, we demonstrated that high-adhesion MC pilin variants, which are responsible for the formation of bundles of pili, have a Lys at position 140, whereas low-adhesion MC pilin variants have a negatively charged amino acid in this location (13) (Fig. 1).

RM11 and 308 GC pilin variants were initially obtained from GC strains FA1090 and MS11, respectively (yielding strains FA1090-RM11 and MS11-308, respectively) (Table 1). The RM11 PilE variant produces S pilin. The adhesiveness of the wild-type strains expressing these variants is shown in Table 1 and is compared to that of a nonpiliated derivative of strain FA1090. The nonpiliated GC adhered much better than the nonpiliated variant MC, probably as a consequence of both MC encapsulation and expression of Opa proteins by FA1090. The adhesiveness of RM11 and 308 relative to that of FA1090 pilE::Km was compatible with low- and high-adhesion phenotypes, respectively. Furthermore, the pilus morphology of these strains was consistent with these data, since 308 is responsible for the formation of bundles of pili, whereas RM11 produces long and flexible pili without any bundling. However, it should be pointed out that the piliation of the latter strain was poor, probably due to the large amount of S-pilin production. The primary sequences of 308 and RM11 pilins contained a Lys and a Glu, respectively, at position 140, as expected for high- and low-adhesion variants, consistent with previous data obtained with MC pilin variants (Fig. 1).

The pilE gene corresponding to each of the above variants was transcriptionally fused to a Kmr gene lacking its own promoter. These fusions were then introduced by allelic replacement into the pilE locus of MC clone 12 and GC strain FA1090. The former is an Opa− PilC+ derivative of MC strain 8013, and the latter is Opa+ PilC+. In order to eliminate the possibility of phenotypic changes due to the variation of a bacterial component other than pilin, all experiments described below were carried out with pools of transformants produced as described in Materials and Methods.

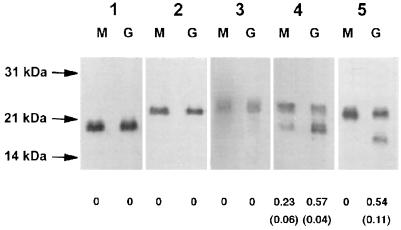

In a first set of experiments, the electrophoretic properties of each variant, when produced in GC or MC, were compared. The amount of S pilin produced was also determined with RS. The results are reported Fig. 2. Pilins of strains expressing SB::Km, SC::Km, and 308::Km fusions were processed in an identical manner in both Neisseria species. On the other hand, differences were observed with S-pilin-producing strains, i.e., SA::Km and RM11::Km variants. The SA::Km fusion was responsible for the production of a larger amount of truncated S pilin in GC than in MC (Fig. 2, lanes 4G and 4M). The RM11::Km fusion was responsible for the production of S pilin only in GC (Fig. 2, lane 5G) (RS, 0.54 ± 0.11); in MC, only full-length monomers were detected (Fig. 2, lane 5M) (RS, 0 ± 0). These data suggested that the mechanisms involved in S-pilin production are not identical in MC and GC.

FIG. 2.

Western blot of total bacterial extracts showing the electrophoretic migration of variants containing the SB::Km (lanes 1), SC::Km (lanes 2), 308::Km (lanes 3), SA::Km (lanes 4), and RM11::Km (lanes 5) pilin fusions. Each variant was produced by MC strain 8013 (lanes M) or GC strain FA1090 (lanes G). The values below the lanes correspond to the mean (standard deviation) RS values determined by density analysis in at least four independent experiments containing various quantities of proteins. Migration was identical for each variant in both species, except for S-pilin-producing variants (SA and RM11), which produced larger amounts of truncated S pilin in GC than in MC.

Adhesiveness induced in both species by each pilE::Km fusion was next determined (Table 2). SB::Km- and 308::Km-expressing strains were at least fivefold more adhesive than isogenic strains expressing low-adhesion pilin fusions (SC::Km, SA::Km, and RM11::Km) in both MC and GC, thus demonstrating that pilin variants are responsible for similar adhesion phenotypes in both species. However, it should be pointed out that adhesiveness induced by these fusions was always lower than that of the wild-type strain expressing pilE alleles (compare values in Table 2 and Table 1). The likely explanation is a modification of mRNA stability due to transcriptional fusion of the pilE gene with the Kmr gene.

TABLE 2.

Adhesion of MC and GC isolates expressing identical pilin variants to Hec-1B cellsa

| Variant | Adhesiveness of strain:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| FA1090 | 8013 | |

| Nonpiliated | 0.003 (0.003) | 0.0004 (0.0004) |

| SB::Km | 0.22 (0.02) | 0.087 (0.007) |

| SC::Km | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.003) |

| 308::Km | 0.14 (0.03) | 0.076 (0.006) |

| SA::Km | 0.01 (0.007) | 0.008 (0.002) |

| RM11::Km | 0.015 (0.006) | 0.005 (0.001) |

Each pilin fusion was introduced into strains 8013 and FA1090. Adhesiveness was defined as the ratio of cell-associated CFU to CFU in the supernatant after 4 h of incubation. Values correspond to the mean of at least five assays; standard deviations are given in parentheses. In both 8013 and FA1090, high-adhesion pilin variants SB::Km and 308::Km were responsible for adhesiveness at least four to five times higher than that of low-adhesion variants SC::Km, SA::Km, and RM11::Km.

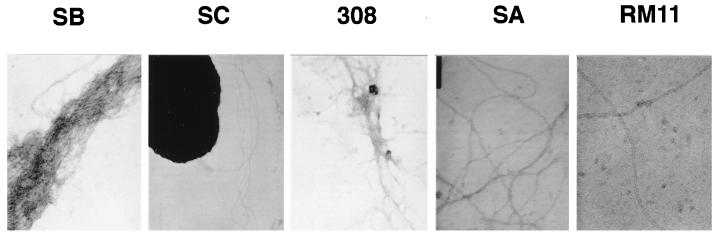

Comparative piliation analysis of the above transformants was carried out by transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 3). In both species, high-adhesion SB and 308 pili formed bundles, whereas low-adhesion SC and SA pili formed long, separate fibers (13). In isolates expressing the RM11::Km fusion, long, separate pili were detected only in MC; in GC, no individual fibers were clearly visualized by transmission electron microscopy (data not shown). This latter difference is consistent with the fact that RM11 produced a larger amount of S pilin in GC than in MC. However, it should be pointed out that the wild-type strain FA1090 RM11 is piliated, albeit rather poorly. Furthermore, FA1090 expressing the RM11::Km fusion was more adhesive than a nonpiliated derivative (Table 2). Taken together, these data suggest that a smaller number of pili might be produced by FA1090 expressing RM11::Km than by the wild-type strain FA1090-RM11 and not detected by electron microscopy. As mentioned above, the reduction in pilin production due to transcriptional fusion might be responsible for the differences in piliation observed between FA1090-RM11 and FA1090 expressing RM11::Km.

FIG. 3.

Transmission electron microscopy of negatively stained pilin preparations of MC or GC transformants containing the SB::Km, SC::Km, 308::Km, SA::Km, and RM11::Km pilin fusions. Pili were produced by the species from which the original variant was not isolated; hence, SB, SC, and SA pili are shown as being produced in GC strain FA1090, and 308 and RM11 pili are shown as being produced in MC strain 8013. SB and 308 pili make bundles, unlike SC, SA, and RM11 pili.

Taken together, the above data demonstrate that a given pilin variant expressed nearly identical phenotypes in both GC and MC with respect to bundling and adhesiveness. The only difference observed was in the amount of S pilin produced, which was always larger in GC than in MC.

Consequences of pilin glycosylation on Ser63 for the production of S pilin.

One striking finding from the above data was that, in strains expressing RM11 and SA, the amount of S pilin produced was larger in GC than in MC. Furthermore, in a previous study, we showed that O-linked glycosylation on Ser63 of an SA variant was required for MC to enhance pilin production and that, in variants altered at this site, the release of truncated S pilin was dramatically reduced. Consistent with these data is the lack of S-pilin production in MC by the RM11 variant, which does not have a Ser at position 63 (Fig. 1). However, strikingly significant amounts of S pilin were produced by this variant in GC. These results suggest that, in these two species, the contributions of glycosylation to S-pilin production could be different.

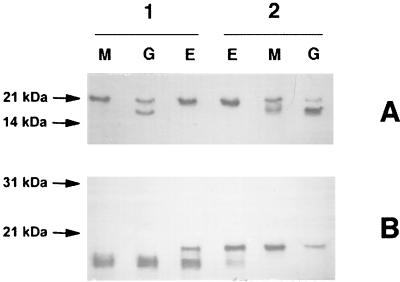

In order to investigate the possible role of a posttranslational modification on Ser63 in the maturation of RM11 GC pilin into S pilin, site-directed mutagenesis of RM11 was performed. The RM11 variant contains a Gly at position 62 and an Ala at position 63 (Fig. 1). A derivative of RM11 was engineered to contain Ser at positions 62 and 63. The resulting pilin variant was designated RM11rg. In Neisseria, the molecular weight of the full-length monomeric pilin of RM11rg was higher than that of the parental RM11 pilin (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 1M and 1G with lanes 2M and 2G), demonstrating that the replacement of an Ala by a Ser restored a posttranslational modification which does not occur in Escherichia coli. The molecular weights of RM11rg and RM11 pilins produced in Neisseria were next compared to those of these pilins produced in E. coli (Fig. 4B). For this latter species, it has clearly been demonstrated that, due to the lack of prepilin peptidase, incomplete processing occurs and gives rise to two different products of the pilin gene: a large one, prepilin, whose signal peptide is not cleaved, and a smaller one (790 Da), which corresponds to mature pilin (3). As expected, two such bands were seen when RM11 and RM11rg were produced in E. coli (Fig. 4, lanes 1E and 2E). Furthermore, the migration of these two variants produced in E. coli was identical, showing that changing an Ala to a Ser did not intrinsically affect the protein structure; this result, however, does not explain the modification of migration observed between Fig. 4B, lanes 2M and 2G, on the one hand and lanes 1M and 1G on the other hand. These findings confirm the introduction of a posttranslational modification in RM11.

FIG. 4.

Western blot of total bacterial extracts. (A) Samples were electrophoresed for 30 min in a gel containing SDS, a 13 to 20% acrylamide gradient, and 4 M urea. (B) Same gel but electrophoresed for 90 min. Lanes 1, nonglycosylated RM11 pilin variant produced by MC (M), GC (G), or E. coli (E). Lanes 2, glycosylated RM11rg pilin variant produced by MC (M), GC (G), or E. coli (E). Monoclonal antibody 5C5 was used for pilin detection. S pilin (14 kDa) cannot be visualized on panel B, since the characterization of significant differences in the migration of glycosylated and nonglycosylated full-length monomers of pilin requires long electrophoresis periods, such that truncated S pilin migrates off the gel. On the other hand, S pilin can be seen after a short migration period (panel A, lanes 1G, 2M, and 2G); however, no molecular weight difference in the full-length monomer can be appreciated. Lanes 1E and 2E show two different products of the full-length pilin gene: a large one, which is prepilin, whose signal peptide is not cleaved, and a smaller one, which corresponds to mature pilin. As previously shown (3), this result is due to the lack of prepilin peptidase, resulting in incomplete processing of prepilin.

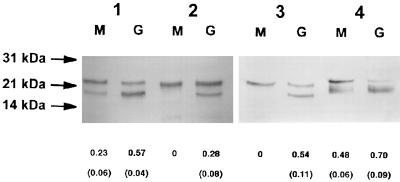

The production of S pilin by bacteria expressing modified or nonmodified pilin variants was compared. As already mentioned, S pilin was not produced by an MC derivative expressing the parental nonglycosylated RM11 variant (Fig. 5, lane 3M) (RS, 0), whereas a GC strain expressing the same pilin produced a significant amount of S pilin (Fig. 5, lane 3G) (RS, 0.54 ± 0.11). On the other hand, the RM11rg derivative produced S pilin even when expressed in MC (Fig. 5, lane 4M) (RS, 0.48 ± 0.06) but in an amount smaller than that produced in GC (Fig. 5, lane 4G) (RS, 0.7 ± 0.09). These data show that the posttranslational modification introduced in RM11rg favors the production of S pilin in both GC and MC.

FIG. 5.

Western blot of total bacterial extracts. Samples were electrophoresed by SDS–15% PAGE. Lanes 1, SA-producing strains (glycosylated pilin); lanes 2, SA(Ser62Ala-Ser63Ala)-producing strains (nonglycosylated pilin); lanes 3, RM11-producing strains (nonglycosylated pilin); lanes 4, RM11rg-producing strains (glycosylated pilin). Total protein extracts of MC strain 8013 or GC strain FA1090 expressing the different pilin variants are designated by M or G, respectively. The values below the lanes correspond to the mean (standard deviation) RS values determined by density analysis in at least four independent experiments containing various quantities of proteins.

In order to confirm that a nonglycosylated pilin variant was capable of producing S pilin in GC, the SA(Ser62Ala-Ser63Ala) variant of SA, which has two Ala residues in place of Ser62 and Ser63 and which has been shown to be nonglycosylated, was introduced into GC strain FA1090 (14). The amount of S pilin produced by the parental glycosylated SA pilin was more abundant in GC than in MC (Fig. 5, lanes 1M and 1G) (RS, 0.23 ± 0.06 and 0.57 ± 0.04, respectively). When similar strains expressed the nonglycosylated variant, no S pilin was produced in MC (Fig. 5, lane 2M) (RS, 0), whereas pilin was still processed as a truncated soluble form in GC (Fig. 5, lane 2G) (RS, 0.28 ± 0.08). These data confirmed that in GC, as in MC, pilin glycosylation favors the production of S pilin. However, the fact that the loss of glycosylation did not entirely prevent the processing of pilin into S pilin demonstrates that in GC, unlike in MC, glycosylation is not required for S-pilin production and suggests that the mechanisms responsible for the production of S pilin in MC and GC are different.

DISCUSSION

Pilus-mediated adhesion is one of the major mechanism by which GC and MC can interact with cells. For encapsulated MC, it is the only means by which bacteria can adhere to cells. Pilin plays a major role in this process by being the scaffold for pili. The cell-binding domain is thought to be carried by the PilC proteins. However, in both MC and GC, pilin antigenic variation has been shown to be responsible for intrastrain variability in bacterial adhesiveness. The mechanism of this variability has been explored with MC, and high-adhesion pilin has been shown to be responsible for the formation of bundles of pili, which promote the interbacterial interactions responsible for the growth of microorganisms as colonies on infected monolayers. In order to address whether a similar mechanism is responsible for intrastrain variability in GC, we introduced low- and high-adhesion MC pilin variants into GC and low- and high-adhesion variants isolated from GC into MC. To achieve this goal, transcriptional fusions were created between pilin and a Kmr resistance gene and then were shuttled back into MC and GC strains. Thus, all variants studied were introduced into the same backgrounds.

Our data demonstrated that (i) in GC, as in MC, high-adhesion pilin variants form bundles of pili and (ii) each variant studied is responsible for equivalent pilus-mediated adhesiveness and identical pilus morphology in both species, thus showing that full-size pilins are functionally exchangeable between GC and MC. It should be pointed out that strains expressing pilins from pilE::Km fusions were always less adhesive than wild-type strains producing the same variants. The most likely explanation for this finding is a modification of the half-life of the pilin mRNA induced by the transcriptional fusion, thus leading to a decreased concentration of pilin. In addition, this hypothesis is consistent with the fact that RM11 in the wild type was clearly piliated, whereas a strain expressing RM11 fused to the Kmr gene was not piliated.

During the course of these experiments, we observed that S-pilin-producing variants make more truncated monomers in GC than in MC. In a previous work, glycosylation was shown to be required for the production of S pilin in MC (14), and the glycosylation site was identified as Ser63. Replacement of this residue by an Ala in SA abolished the ability of an MC strain to produce S pilin. On the other hand, a GC strain expressing a nonglycosylated derivative of SA was still capable of producing a significant amount of S pilin. Similar results were obtained with the RM11 pilin variant. This latter pilin does not have Ser63; furthermore, its electrophoretic mobility is identical in GC or E. coli, thus eliminating the possibility that it is glycosylated at another site. Consistent with the above data, S pilin is produced by this variant only in GC and not in MC. On the other hand, restoration of glycosylation by introduction of Ser63 induces the production of S pilin in MC. The mechanism by which glycosylation favors S-pilin production is unknown. However, protein glycosylation is well known to help in solubilizing proteins, and a nonspecific effect of this posttranslational modification is likely. The reason why nonglycosylated GC pilin remained capable of producing S pilin is unknown. An additional glycosylation site in GC pilin was not a likely explanation, as there was no detectable difference in molecular weight between the products of both species with identical pilE genes. On the other hand, pilin has been shown to undergo several posttranslational modifications (14, 25); one of these could be specific for pilin produced in GC and could be responsible for the difference in pilin solubilization.

No function has been found yet for S pilin. It was recently shown that there is a cell-binding domain within the first 77 residues of mature pilin (13). The structural data suggest that this potential pilin cell-binding domain is hidden in assembled pili. One hypothesis is that it may be available for binding only in the context of the soluble monomer. This cell-binding domain could subsequently play a role in meningococcal pathogenesis by interacting with host membrane or immune system components. Work is currently in progress to test this hypothesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Hank Seifert for providing us with strains and C. Tinsley for careful reading of the manuscript.

M.M. was the recipient of a scholarship from the Ministère de la Recherche et de la Technologie. X.N. was supported by INSERM, Université René Descartes, the DRET, and the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achtman M, Neibert M, Crowe B A, Strittmatter W, Kusecek B, Weyse E, Walsh M J, Slawig B, Morelli G, Moll A, Blake M. Purification and characterization of eight class 5 outer membrane protein variants from a clone of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A. J Exp Med. 1988;168:507–525. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connel T D, Black W J, H. K T, Barritt D S, Dempsey J A, Kverneland K, Jr, Stephenson A, Schepart G L, Murphy G L, Cannon J G. Recombination among protein II genes of Neisseria gonorrhoeae generates new coding sequences and increases structural variability in the protein II family. Mol Microbiol. 1988;2:227–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1988.tb00024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dupuy B, Taha M K, Pugsley A P, Marchal C. Neisseria gonorrhoeae prepilin export studied in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7589–7598. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.23.7589-7598.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guibourdenche M, Popoff M Y, Riou J Y. Deoxyribonucleic acid relatedness among Neisseria gonorrhoeae, N. meningitidis, N. lactamica, N. cinerea and Neisseria polysaccharea. Ann Inst Pasteur/Microbiol (Paris) 1986;137B:177–185. doi: 10.1016/s0769-2609(86)80106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haas R, Schwarz H, Meyer T. Release of soluble pilin antigen coupled with gene conversion in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:9079–9083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagblom P, Segal E, Billyard E, So M. Intragenic recombination leads to Neisseria gonorrhoeae pilus antigenic variation. Nature. 1985;315:156–158. doi: 10.1038/315156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho S N, Hunt H D, Horton R M, Pullen J K, Pease L R. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jonsson A-B, Nyberg G, Normark S. Phase variation of gonococcal pili by frameshift mutation in pilC, a novel gene for pilus assembly. EMBO J. 1991;10:477–488. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07970.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kellog D D, Peacock W L, Deacon W E, Brown L, Pirkle C I. Neisseria gonorrhoeae. I. Virulence genetically linked to a clonal variation. J Bacteriol. 1963;141:1274–1279. doi: 10.1128/jb.85.6.1274-1279.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lambden P R, Robertson J N, Watt P J. Biological properties of two distinct pilus types produced by isogenic variants of Neisseria gonorrhoeae P9. J Bacteriol. 1980;141:393–396. doi: 10.1128/jb.141.1.393-396.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long C D, Madraswala R N, Seifert H S. Comparisons between colony phase variation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae FA1090 and pilus, pilin, and S-pilin expression. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1918–1927. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.1918-1927.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marceau M, Beretti J-L, Nassif X. High adhesiveness of encapsulated Neisseria meningitidis to epithelial cells is associated with the formation of bundles of pili. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:855–863. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17050855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marceau M, Forest K, Béretti J L, Tainer J, Nassif X. Consequences of the loss of O-linked glycosylation of meningococcal type IV pilin on piliation and pilus mediated adhesion. Mol Microbiol. 1997;27:705–716. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nassif X, Beretti J-L, Lowy J, Stenberg P, O’Gaora P, Pfeifer J, Normark S, So M. Roles of pilin and PilC in adhesion of Neisseria meningitidis to human epithelial and endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3769–3773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nassif X, Lowy J, Stenberg P, O’Gaora P, Ganji A, So M. Antigenic variation of pilin regulates adhesion of Neisseria meningitidis to human epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:719–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nassif X, Puaoi D, So M. Transposition of Tn1545-Δ3 in the pathogenic neisseriae: a genetic tool for mutagenesis. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2147–2154. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.7.2147-2154.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olafson R W, McCarthy P J, Bhatti A R, Dooley J S G, Heckels J E, Trust T J. Structural and antigenic analysis of meningococcal piliation. Infect Immun. 1985;48:336–342. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.2.336-342.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parge H E, Forest K T, Hickey M J, Christensen D, Getzoff E D, Tainer J A. Structure of the fibre-forming protein pilin at 2.6 A resolution. Nature. 1995;378:32–38. doi: 10.1038/378032a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Potts W J, Saunders J R. Nucleotide sequence of the structural gene for class I pilin from Neisseria meningitidis: homologies with the pilE locus of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol Microbiol. 1988;2:647–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1988.tb00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rahman M, Kallstrom M, Normark S, Jonsson A B. PilC of pathogenic Neisseria is associated with the bacterial surface. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:11–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4601823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rudel T, Scheuerpflug I, Meyer T F. Neisseria PilC protein identified as type-4 pilus tip-located adhesin. Nature. 1995;373:357–362. doi: 10.1038/373357a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rudel T, Van Putten J P M, Gibbs C P, Haas R, Meyer T F. Interaction of two variable proteins (PilE and PilC) required for pilus-mediated adherence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to human epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3439–3450. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb02211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stimson E, Virji M, Barker S, Panico M, Blench I, Saunders J R, Payne G, Moxon E R, Dell A, Morris H R. Discovery of a novel protein modification: alpha-glycerophosphate is a substituent of meningococcal pilin. Biochem J. 1996;316:29–33. doi: 10.1042/bj3160029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stimson E, Virji M, Makepeace K, Dell A, Morris H R, Payne G, Saunders J R, Jennings M P, Barker S, Panico M, Blench I, Moxon E R. Meningococcal pilin: a glycoprotein substituted with digalactoside 2,4-diacetamido-2,4,6-trideoxyhexose. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:1201–1214. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17061201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swanson J, Sparks E, Zeligs B, Siam M A, Parrott C. Studies on gonococcus infection. V. Observations on in vitro interactions of gonococci and human neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1974;10:633–644. doi: 10.1128/iai.10.3.633-644.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Virji M, Alexandrescu C, Fergusson D J P, Saunders J R, Moxon E R. Variations in the expression of pili: the effect on adherence of Neisseria meningitidis to human epithelial and endothelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1271–1279. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Virji M, Heckels J E, Potts W H, Hart C A, Saunders J R. Identification of epitopes recognised by monoclonal antibodies SM1 and SM2 which react with all pili of Neisseria gonorrhoeae but which differentiate between two structural classes of pili expressed by Neisseria meningitidis and the distribution of their encoding sequences in the genomes of Neisseria sp. J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135:3239–3251. doi: 10.1099/00221287-135-12-3239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Virji M, Saunders J R, Sims G, Makepeace K, Maskell D, Ferguson D J P. Pilus-facilitated adherence of Neisseria meningitidis to human epithelial and endothelial cells: modulation of adherence phenotype occurs concurrently with changes in primary amino acid sequence and the glycosylation status of pilin. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:1013–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]