Summary

Dynamic chemical modifications in eukaryotic messenger RNAs (mRNAs) constitute an essential layer of gene regulation, among which N6‐methyladenosine (m6A) was unveiled to be the most abundant. m6A functionally modulates important biological processes in various mammals and plants through the regulation of mRNA metabolism, mainly mRNA degradation and translation efficiency. Physiological functions of m6A methylation are diversified and affected by intricate sequence contexts and m6A machineries. A number of studies have dissected the functional roles and the underlying mechanisms of m6A modifications in regulating plant development and stress responses. Recently, it was demonstrated that the human FTO‐mediated plant m6A removal caused dramatic yield increases in rice and potato, indicating that modulation of m6A methylation could be an efficient strategy for crop improvement. In this review, we summarize the current progress concerning the m6A‐mediated regulation of crop development and stress responses, and provide an outlook on the potential application of m6A epitranscriptome in the future improvement of crops.

Keywords: N6‐methyladenosine, m6A machineries, crop development, stress responses, crop improvement

Introduction

Posttranscriptional or cotranscriptional RNA chemical modifications play essential roles in determining mRNA fates. Among the 160 distinct mRNA modifications identified so far, N6‐methyladenosine (m6A) is the most abundant and best‐characterized (Shao et al., 2021). m6A methylation is reversible in vivo, and functions under the synergistic effect of m6A methyltransferases (writers), demethylases (erasers) and reader proteins (readers), which install, remove and recognize m6A marks, respectively (Shi et al., 2019a). In mammals, m6A installation is mainly implemented by a methyltransferase complex, in which the METTL3/METTL14 (methyltransferase‐like 3/14) heterodimer constitutes the core component (Liu et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016a, 2016b). METTL3 harbours the methyl‐transfer activity and functions as a catalytic subunit, while METTL14 facilitates the binding of the complex to the targeted transcripts (Wang et al., 2016a, 2016b). In addition, other subunits including Wilm’s tumour 1‐associating protein (WTAP) (Ping et al., 2014), Vir like m6A methyltransferase associated (VIRMA) (Yue et al., 2018), Zinc finger CCCH domain‐containing protein 13 (ZC3H13) (Wen et al., 2018) and RNA‐binding motif protein 15 (RBM15) (Patil et al., 2016) were also revealed to be functionally important for the m6A deposition. As for m6A removal, the fat mass and obesity‐associated protein (FTO) and the alkylated DNA repair protein AlkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5), both containing the AlkB domain, represent the well‐studied demethylases in mammals (Jia et al., 2011; Zheng et al., 2013). m6A methyltransferases and demethylases act cooperatively to bring the reversibility for m6A methylation, accompanied by diversified deposition and distribution along transcripts (Shi et al., 2019a). To exert the physiological functions, m6A needs to be recognized by the reader proteins. Mammalian YTH‐domain proteins, including YTHDF1/2/3 (Dominissini et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014, 2015) and YTHDC1/2 (Hsu et al., 2017; Xiao et al., 2016), as well as some specific ribonucleoproteins (Alarcón et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2015) or RNA binding proteins (RBPs) (Edupuganti et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2019), have the ability to recognize m6A sites, and further modulate the m6A‐modified transcripts by interacting with other functional regulatory proteins, thus were identified as the m6A reader proteins (Shi et al., 2019a). Currently, m6A has been unveiled to functionally modulate mRNA metabolism including mRNA stability (Huang et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2014), translation efficiency (Wang et al., 2015), alternative splicing (Zhao et al., 2014), and nuclear‐cytoplasm transport (Roundtree et al., 2017), thereby regulating multiple biological processes, such as embryonic and post‐embryonic development (Batista et al., 2014), cell circadian rhythms (Fustin et al., 2013), and cancer stem cell proliferation (Zhang et al., 2016). Given its prevalence and function diversity, m6A has also been extensively investigated, as an important epigenetic modification, in plants including Arabidopsis and various crops with important agronomic traits (Liang et al., 2020; Shao et al., 2021; Yue et al., 2019).

In the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, the m6A machineries have been adequately identified and proved to harbour multiple physiological roles (Shao et al., 2021). The m6A methyltransferase complex regulates a variety of essential growth and development processes including embryo development (Zhong et al., 2008), root vascular formation (Růžička et al., 2017), seedling growth (Růžička et al., 2017) and apical dominance formation (Bodi et al., 2012). Importantly, the core subunit of m6A methyltransferase complex, FKBP12 interacting protein 37 KD (FIP37), which is a homolog of the mammalian WTAP, participates in maintaining the normal proliferation of shoot meristems by negatively regulating the mRNA stability of several key shoot meristem genes (Shen et al., 2016). The m6A demethylase AtALKBH10B‐mediated m6A removal elevates the mRNA stability of flower‐promoting genes, thereby positively regulating floral transition (Duan et al., 2017). These studies reveal that Arabidopsis m6A modification has a capacity to decrease mRNA stability, thereby reducing the mRNA abundance of specific genes. However, the YTH‐domain protein evolutionarily conserved C‐terminal region 2 (ECT2) was shown to stabilize m6A‐modified transcripts, and further modulate the development of trichome morphogenesis (Arribas‐Hernández et al., 2018; Scutenaire et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2018). Another YTH‐domain protein CPSF30‐L (the longer isoform of cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor 30) is involved in regulating the alternative polyadenylation (Hou et al., 2021; Pontier et al., 2019; Song et al., 2021). Therefore, Arabidopsis m6A machineries could adopt diverse molecular mechanisms to cope with divergent physiological processes. Besides the development regulation, m6A modification also mediates the biotic and abiotic stress responses in Arabidopsis, partially by affecting the mRNA stability and alternative polyadenylation of targeted transcripts (Shao et al., 2021). The complexity of m6A functions and mechanisms implies that more pervasive investigations are needed to better understand its biological role in plants. The current mechanistic studies based on Arabidopsis provide an advantageous reference for other plant species including crops.

More recently, the human FTO‐mediated plant m6A demethylation caused a ~50% increase in field yield and biomass of rice and potato (Yu et al., 2021). These findings are spectacular and suggest that modulation of m6A methylation may hold potential in serving as a strategy to dramatically improve crop growth and yield. In this review, we summarize the current progress in understanding the m6A characteristics, the m6A‐mediated regulation of mRNA metabolism, and the mechanistic links of m6A with developmental processes and stress responses in crops. We also provide an outlook on potential applications and remaining challenges concerning m6A epitranscriptome in the future crop improvement.

m6A characteristics in crops

m6A distribution along transcripts in crops

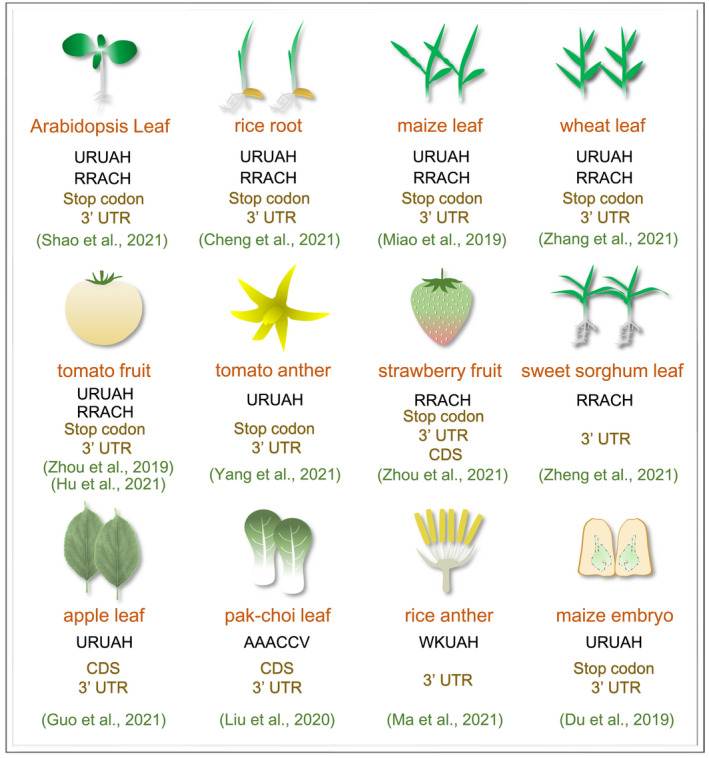

With the application of high‐throughput m6A sequencing technology (m6A‐seq) (Dominissini et al., 2012; Meyer et al., 2012), the transcript‐specific m6A localization and enrichment have been uncovered at the transcriptome‐wide level in various plant species. In Arabidopsis, thousands of transcripts contain m6A modifications, which distribute preferentially around the stop codon or in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) (Luo et al., 2014; Wan et al., 2015). This distribution preference is conserved among several important crops, including rice (Oryza sativa) (Cheng et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2019a), maize (Zea mays) (Miao et al., 2020), wheat (Triticum aestivum) (Zhang et al., 2021b), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) (Hu et al., 2021b; Yang et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2019), and sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) (Zheng et al., 2021) (Figure 1). A recent study that compared the m6A methylomes for 13 representative plant species spanning over half a billion years of evolution confirmed the conserved distribution of m6A modifications in the stop codon and 3′ UTR regions (Miao et al., 2022). Specially, the m6A modification in strawberry (Fvesca vesca) could also be highly enriched in the coding sequence (CDS) region adjacent to the start codon, besides the occurrence in the stop codon and 3′ UTR region (Zhou et al., 2021) (Figure 1). This unique CDS preference appears in the ripe strawberry fruit, but not the unripe fruit, indicating it is a ripening‐specific m6A characteristic (Zhou et al., 2021). Moreover, m6A modifications in apple (Malus domestica) and pak‐choi (Brassica rapa) leaves are most abundant in the CDS region, followed by the 3′ UTR region (Guo et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2020) (Figure 1). Therefore, m6A distribution around the stop codon or in the 3′ UTR could be conserved among various plants including Arabidopsis, rice, maize, wheat, tomato, sweet sorghum, strawberry, apple, and pak‐choi, while m6A deposition in the CDS region might be development stage‐specific or tissue‐specific. The inducements related to this distribution characteristic currently remain elusive. A recent study in Arabidopsis suggests that H3K36me2 histone marks contribute to the preferential m6A deposition in the 3’ UTR (Shim et al., 2020). This finding provides us valuable considerations in investigating the relevant mechanisms of m6A distribution in crops.

Figure 1.

m6A motifs and distribution preferences along transcripts in various tissues of Arabidopsis and crops. R represents adenosine (A) or guanosine (G); H represents A, cytidine (C), or uridine (U); W represents A or U; K represents G or U; V represents A, G, or U. CDS, coding sequence. UTR, untranslated region. m6A motifs were predicted from m6A‐seq datasets that were performed with at least two independent biological replicates with standard m6A‐seq procedures.

m6A motifs in crops

The initial m6A‐seq analysis revealed that Arabidopsis m6A methylation occurs in a sequence context as RRACH (R represents adenosine (A) or guanosine (G); H represents A, cytidine (C), or uridine (U)) (Duan et al., 2017; Luo et al., 2014), the conserved m6A motif among mammals (Dominissini et al., 2012; Meyer et al., 2012). However, a subsequent study identified a plant‐specific m6A motif URUAH in Arabidopsis, which mainly locates within 3′ UTR and is targeted by the reader protein ECT2 (Wei et al., 2018). These results suggest that Arabidopsis possesses two different m6A motifs. Notably, a recent study claimed that URUAY is not an m6A motif, but it is rather enriched in the periphery of the canonical RRACH motifs (Arribas‐Hernández et al., 2021a). m6A marks in rice (Zhang et al., 2019a), maize (Miao et al., 2020), wheat (Zhang et al., 2021b), or tomato (Hu et al., 2021b; Yang et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2019) fall into both the RRACH and URUAH motifs, as the model plant Arabidopsis (Figure 1). Strawberry (Zhou et al., 2021) and sweet sorghum (Zheng et al., 2021) harbour the conserved RRACH motif, while apple (Guo et al., 2021) was demonstrated to possess the plant‐specific URUAH motif (Figure 1). It is possible that the two distinct motifs may extensively exist in most of the crops, and could be individually identified in specific biological processes. Moreover, the consensus sequence of m6A in pak‐choi appears to be AAACCV (V means U, A, or G) (Liu et al., 2020), and four new m6A motifs were identified in rice anther, in which the WKUAH (W represents U or A; K means G or U) is the most abundant (Ma et al., 2021) (Figure 1). These findings suggest that m6A modifications in crops involve complicated sequence preferences. However, we currently do not know how m6A machineries achieve selectivity toward certain motif sequences to accomplish m6A installation, removal and recognition. One likely scenario is that they may be localized to diverse sequence contexts through interaction with RBPs that recognize distinct features of the transcripts.

Regulation of m6A on mRNA metabolism in crops

m6A possesses multiple regulatory effects on mRNA metabolism in Arabidopsis, such as mRNA stability (Anderson et al., 2018; Arribas‐Hernández et al., 2021b; Duan et al., 2017; Kramer et al., 2020; Shen et al., 2016; Wei et al., 2018), transcriptome integrity (Pontier et al., 2019), and alternative polyadenylation (Hou et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2021a; Parker et al., 2020; Song et al., 2021). Currently, substantial progresses have been made in deciphering the influence of m6A methylation on crop mRNA metabolism, mainly mRNA degradation and translation (Shao et al., 2021).

Modulation of mRNA stability in crops

Through the combination of transcriptome‐wide m6A‐seq and RNA‐seq analyses, the potential relationship between m6A modification and mRNA abundance has been revealed in rice (Cheng et al., 2021), maize (Du et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2020), tomato (Zhou et al., 2019), strawberry (Zhou et al., 2021), and pak‐choi (Liu et al., 2020) under divergent physiological circumstances. In the rice root threatened with cadmium stress (Cheng et al., 2021) or pak‐choi seedling treated with hot temperature (Liu et al., 2020), no exact correlation between m6A modification and mRNA abundance was determined, although thousands of transcripts exhibited differential m6A enrichment or gene expression under these stress conditions. However, a positive correlation between m6A methylation and mRNA levels was discovered in maize embryos cultured with 2,4‐D, an auxin analogue (Du et al., 2020). Moreover, m6A modification locating within the stop codon or 3’ UTR regions was shown to negatively regulate the mRNA abundance in normally growing maize seedling (Luo et al., 2020), tomato fruit (Zhou et al., 2019), and strawberry fruit (Zhou et al., 2021), while m6A enriching in the CDS region in ripe strawberry fruit tends to positively regulate the mRNA levels (Zhou et al., 2021). The different influences of m6A modification on mRNA abundance are correlated with the distinct effects of m6A on mRNA stability (Guo et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2019, 2021). m6A deposition around the stop codon or within the 3′ UTR region possesses the ability to decrease mRNA stability, while m6A in the CDS region promotes mRNA stability. However, the underlying mechanisms need to be elucidated.

Modulation of translation efficiency in crops

Although it is currently unclear whether m6A modification participates in mediating mRNA translation efficiency in Arabidopsis, several studies in crops obtained affirmative answers on this issue. In maize seedling, transcriptome‐wide polysome profiling analysis revealed that m6A possesses different effects on translation efficiency, depending on m6A abundances and positions in transcripts (Luo et al., 2020). Concretely, m6A modification nearby the start codon or in the 3′ UTR with low strength (low m6A enrichment value) tends to enhance mRNA translation, while m6A with excessive deposition (excessive m6A enrichment value) in the 3′ UTR decreases the translation efficiency (Luo et al., 2020). In strawberry fruit and apple leaf, m6A methylation was also demonstrated to facilitate mRNA translation (Guo et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2021). More recently, the rice m6A adenosine methylase 2 (OsMTA2) was revealed to interact with the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit h (OsEIF3h) (Huang et al., 2021), implying that m6A modification may modulate mRNA translation via the interactions between m6A machineries and translation factors, adopting the analogous molecular mechanism as the mammals (Lin et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2015).

Regulatory mechanisms of m6A on crop developmental processes

Arabidopsis m6A marks have been demonstrated to modulate multiple physiological processes, reflecting its functional diversity in controlling plant development (Liang et al., 2020; Shao et al., 2021). Disruption of m6A machineries including m6A methyltransferase, demethylases and reader proteins could be an effective pointcut to explore the functional significance of m6A in both Arabidopsis and crops. Current researches have uncovered the m6A‐mediated regulation of key genes with critical roles in crop growth and development.

Regulation of development in grain crops

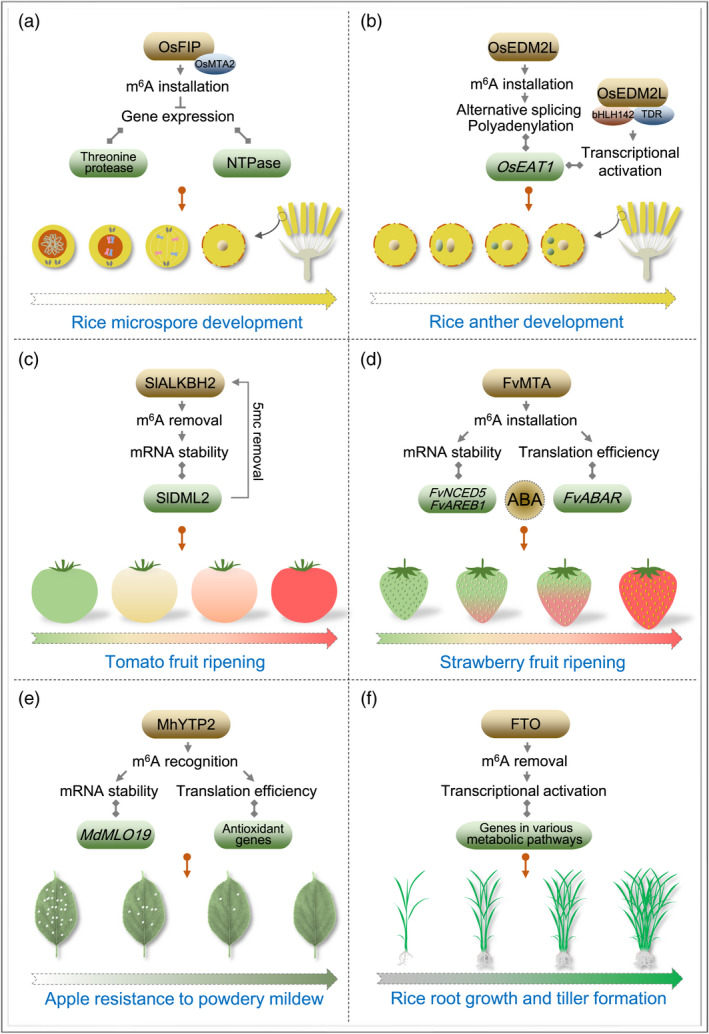

OsFIP, a homolog of the mammalian WTAP, was identified as one of the components in the m6A methyltransferase complex in rice (Zhang et al., 2019a). Functional investigation revealed that OsFIP mediates m6A deposition on transcripts of sporogenesis‐related genes encoding the NTPases and threonine proteases, leading to the acceleration of degradation of these transcripts to control microsporogenesis (Zhang et al., 2019a) (Figure 2a). Deficiency of the rice m6A methyltransferase‐like domain‐containing protein enhances downy mildew 2‐like (OsEDM2L) impaired tapetal programmed cell death (PCD) and causes defective pollen development, indicating its indispensable role for normal anther development (Ma et al., 2021). OsEDM2L could not only interact with the transcription factors basic helix‐loop‐helix 142 (bHLH142) and tapetum degeneration retardation (TDR) to activate the expression of eternal tapetum 1 (EAT1), a positive regulator of tapetal PCD, but also facilitate the suitable alternative splicing and polyadenylation of OsEAT1 transcript by m6A installation, thus regulating the tapetal PCD and anther development (Ma et al., 2021) (Figure 2b). Moreover, the interaction of OsMTA2 with the OseIF3h suggests that OsMTA2 may participate in regulating OseIF3h‐mediated seedling growth and pollen development in rice, although the molecular mechanism is poorly understood (Huang et al., 2021).

Figure 2.

Function of m6A modification on crop growth and development or stress resistance. (a) Regulation of rice m6A methyltransferase subunit OsFIP on microspore development. OsFIP‐mediated m6A installation decreases the expression of genes encoding the threonine proteases and NTPases, thereby maintaining the normal development of rice microspores. Os, Oryza sativa. (b) Regulation of rice m6A methyltransferase‐like domain‐containing protein OsEDM2L on anther development. OsEDM2L‐mediated m6A installation facilitates the proper alternative splicing and polyadenylation of the OsEAT1 mRNA that encodes a positive regulator of tapetal programmed cell death during the anther development. Moreover, OsEDM2L could directly activate the OsEAT1 transcription by interacting with the transcription factors bHLH142 and TDR. (c) Regulation of tomato m6A demethylase SlALKBH2 on fruit ripening. SlALKBH2‐mediated m6A removal promotes mRNA stability of DNA demethylase gene SlDML2, a key ripening‐promoting gene, thereby facilitating fruit ripening. SlDML2 in turn acts on SlALKBH2 to activate its transcription by DNA demethylation, representing an interplay between m6A RNA methylation and DNA methylation during tomato fruit ripening. Sl, Solanum lycopersicum. (d) Regulation of strawberry m6A methyltransferase FvMTA on fruit ripening. FvMTA‐mediated m6A installation promotes mRNA stability or translation efficiency of key genes in ABA pathway including FvNCED5, FvAREB1 and FvABAR, thereby facilitating fruit ripening. Fv, Fvesca vesca. (e) Regulation of apple m6A reader MhYTP2 on leaf resistance to powdery mildew. MhYTP2‐mediated m6A recognition elevates the mRNA stability of MdMLO19, a positive regulator in powdery mildew resistance, and the translation efficiency of antioxidant genes, thereby enhancing the resistance of apple leaves to powdery mildew. Mh, Malus hupehensis; Md, Malus domestica. (f) Regulation of human m6A demethylase FTO on rice root growth and tiller formation. Heterologous expression of human FTO in rice promotes root growth and tiller formation by regulating the expression of genes in various metabolic pathways, therefore facilitating rice yield and biomass.

In maize, m6A‐mediated post‐transcriptional regulation contributes to the heterosis in hybrid seedlings and the induction of callus cultured with the addition of auxin analogue 2,4‐D (Du et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2021). The former was predicted to correlate with the increased translation efficiency of m6A‐modified transcripts (Luo et al., 2021), while the latter may be caused by the elevated mRNA abundance of several key genes involved in the callus induction (Du et al., 2020).

Regulation of development in horticultural crops

Fruit expansion represents an important process for fruit growth and development. It has been revealed that the overall m6A level increases during tomato fruit expansion, accompanied by the elevated m6A enrichments and transcript levels in several essential expansion‐related genes (Hu et al., 2021b). Exogenous treatment by 3‐deazaneplanocin A (m6A writer inhibitor) or meclofenamic acid (m6A eraser inhibitor) suppresses the expansion of fruit (Hu et al., 2021b), suggesting that m6A methylation participates in modulating the growth and development of tomato fruit. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms need to be clarified.

Recently, m6A methylation was reported to regulate fruit ripening, an important biological process for quality formation (Zhou et al., 2019, 2021). In the climacteric fruit tomato, m6A demethylase SlALKBH2 targets the DNA demethylase gene DEMETER‐like DNA demethylase 2 (SlDML2), a key ripening‐promoting gene, and positively modulates its expression by elevating mRNA stability, thus accelerating tomato fruit ripening. Interestingly, SlDML2 can in turn act on SlALKBH2 to activate its transcription by the repressive effect on DNA methylation (5‐methylcytosine, 5mC). These results suggest that SlALKBH2 and SlDML2 function synergistically during tomato fruit ripening, representing an internal correlation between m6A and 5mC (Zhou et al., 2019) (Figure 2c). In the non‐climacteric fruit strawberry, the m6A methyltransferase FvMTA was demonstrated to positively regulate fruit ripening (Zhou et al., 2021). FvMTA‐mediated m6A modification increases mRNA stability or translation efficiency of key genes in the ABA pathway including 9‐cis‐epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase 5 (FvNCED5), ABA‐responsive element‐binding protein 1 (FvAREB1) and putative ABA receptor (FvABAR), which are essential for the ripening of strawberry fruit (Figure 2d). Strawberry genome contains four SlDML2 homologs, among which two contain differential m6A peaks at the onset of fruit ripening. However, none of these genes exhibits a significant increase in mRNA abundance upon ripening initiation. In addition, no differential m6A modification was observed in the transcripts of DNA methyltransferase genes in the RNA‐directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway, which governs the reprogramming of DNA methylation during the ripening of strawberry fruit. This suggests that DNA methylation is dispensable for the FvMTA‐mediated fruit ripening in strawberry (Zhou et al., 2021). Thus, regulation of fruit ripening via m6A modification involves complicated molecular mechanisms and could be distinct among various fruits.

Regulatory mechanisms of m6A on crop stress responses

Mutation of m6A writers in Arabidopsis induces significant changes in the expression of genes responsive to abiotic and biotic stresses, as revealed by transcriptome analysis (Anderson et al., 2018; Bodi et al., 2012; Hu et al., 2021a). Accordingly, the m6A‐mediated stress responses have been extensively studied in various crops, including tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) (Li et al., 2018), rice (Cheng et al., 2021; Shi et al., 2019b; Tian et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021a), wheat (Sun et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021b), sweet sorghum (Zheng et al., 2021), tomato (Yang et al., 2021), apple (Guo et al., 2021; Mao et al., 2021), and pak‐choi (Liu et al., 2020).

Regulation of the biotic stresses in crops

Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) infection causes the increased expression of the potential demethylase genes, concomitant with the decreased expression of the potential methyltransferases, implicating the involvement of m6A in modulating the virus‐induced stress responses in tobacco (Li et al., 2018). In rice, the infection of rice stripe virus or rice black‐stripe dwarf virus (RBSDV) causes a dramatical increase in overall m6A methylation level, accompanied by the changed transcription in genes encoding m6A machineries, implying that m6A modification might be involved in the defence response against virus infection (Zhang et al., 2021a). In addition, when the m6A methyltransferase genes LsMETTL3 and LsMETTL14 from small brown planthopper (SBPH), the insect vector of RBSDV, were silenced, the titre of RBSDV in the midgut cells of SBPHs increased significantly, suggesting a negative correlation between the overall m6A levels and the virus replication (Tian et al., 2021). In watermelon, the infection by cucumber green mottle mosaic virus (CGMMV) leads to the decrease in global m6A level and the increase in expression of m6A demethylase gene ClALKBH4B (He et al., 2021). Some m6A‐modified transcripts related to plant immunity display altered m6A enrichments and transcript levels in response to CGMMV infection. It is probably that ClALKBH4B modulates the expression of the defence genes via m6A methylation, thereby participating in the regulation of watermelon against CGMMV infection (He et al., 2021).

The Malus YTH domain‐containing RNA binding protein 2 (MhYTP2) was demonstrated to positively regulate the apple resistance to powdery mildew (PM) caused by Podosphaera leucotricha (P. leucotricha) (Guo et al., 2021). MhYTP2 could decrease the mRNA stability of Mildew Locus O 19 (MdMLO19), a negative regulator of PM resistance, and improve the translation efficiency of antioxidant genes, thereby repressing the infection of P. leucotricha (Guo et al., 2021) (Figure 2e). The m6A methylation was also predicted to modulate fungus infection in rice, because virulence tests showed that the m6A machineries of Pyricularia oryzae, the causal agent of rice blast disease, were involved in virulence on rice (Shi et al., 2019b). In addition, wheat m6A methylation profiles revealed that thousands of transcripts, including those in plant defence responses and plant‐pathogen interaction pathway, display changed m6A abundances under the infection of wheat yellow mosaic virus, indicating that m6A marks would also participate in mediating wheat resistance to plant pathogens (Zhang et al., 2021b). These findings emphasize that the regulation of m6A in virus or fungus‐related biotic stress seems common in various crop species, although the underlying mechanisms need further investigation.

Regulation of the abiotic stresses in crops

In addition to the role in biotic stress, m6A also modulates abiotic stress responses in crops. In rice, cadmium treatment induces the differential m6A modifications in thousands of transcripts in the root, suggesting that m6A may be associated with the abnormal root development caused by cadmium stress (Cheng et al., 2021). In wheat, genes of the m6A reader protein TaYTHs exhibit obvious expression changes in response to abiotic stresses including water and drought stresses (Sun et al., 2020). Salt stress induces a drastic alteration in m6A methylome in sweet sorghum, leading to the increase in m6A modification and mRNA stability of genes related to the salt resistance, which in turn positively regulated the tolerance to salt stress (Zheng et al., 2021). Furthermore, significant changes in m6A methylome profile, as well as its correlation with mRNA abundance, have been deciphered in pak‐choi seedling under heat stress (Liu et al., 2020), tomato anther under cold stress (Yang et al., 2021), and apple leaf under drought stress (Mao et al., 2021). These results revealed that m6A modification also participates in controlling the responses of crops to temperature and humidity‐induced stresses.

Concluding remarks and future outlook

Rapid advances have been made in recent years in understanding the functional diversity of m6A marks, especially in some important biological processes. Physiological effects of m6A on plant development or stress resistance throughout the life cycle facilitate plant adaptation to the complicated and volatile ecological environment. In spite of this, one extremely essential issue is how to employ m6A investigations to increase the yield and quality of crops, known as crop improvement, thereby facilitating human health. Heterologous expression of human m6A demethylase FTO in rice and potato dramatically elevates the yield and biomass through the transcriptional modulation of genes involved in various metabolic pathways (Yu et al., 2021) (Figure 2f). Recent studies revealed that m6A methyltransferase or demethylase participates in modulating tomato and strawberry fruit ripening, an important process for fruit quality formation (Zhou et al., 2019, 2021). Moreover, m6A reader proteins were demonstrated to mediate the stress responses in both wheat and apple (Guo et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021b). These findings highlight the importance of m6A machineries in physiological regulations, and provide us the possibility for improving crop yield, quality, and stress resistance by controlling the bioactivity of m6A machineries.

Although m6A modification possesses great potential for crop improvement, there exist several major challenges. Firstly, modulation of the key components in m6A system may cause changes in the overall levels of m6A methylation, leading to unpredictable effects. Therefore, a transcriptome‐wide m6A modification map at single‐base resolution is necessary for precise m6A editing at specific sites without changing the overall levels of m6A or the primary sequence of genes with critical roles in crop development or stress response (Zheng et al., 2020). However, the current m6A modification maps constructed for plants can only display m6A modification in a range of 100–200 nucleotides. Current advances in high‐throughput m6A detection techniques at single‐base resolution, including miCLIP (m6A individual‐nucleotide‐resolution crosslinking and immunoprecipitation) (Linder et al., 2015), MAZTER‐seq (RNA digestion via m6A sensitive RNase and sequencing) (Garcia‐Campos et al., 2019), m6A‐REF‐seq (m6A‐sensitive RNA‐endoribonuclease‐facilitated sequencing) (Zhang et al., 2019b), and nanopore DRS (direct RNA sequencing) (Parker et al., 2020; Pratanwanich et al., 2021), may facilitate the precise identification of m6A sites. The second challenge is how to add or remove specific m6A modification sites in gene transcripts. The normal genome editing technique can only result in the addition or deletion of the gene sequences, but not the m6A modification sites. This could be resolved by the application of m6A editing, which makes it possible to precisely reconstruct the m6A marks at specific sites. As a new tool, m6A editing appears to be a fusion of m6A enzymes (writers or erasers) and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/CRISPR‐associated nuclease 9 (Cas9) technology. The m6A editing can add or remove m6A at specific sites under the guidance of single‐guide RNA and protospacer adjacent motif (Cox et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2019; Zheng et al., 2020). Recently, it is proposed that Cas13 has higher RNA target specificity and efficiency than Cas9, and is more suitable for the m6A editing system (Zheng et al., 2020). Moreover, CRISPR‐based prime editing harbours the ability to achieve the substitution, deletion or insertion of all single nucleotides in plant genomes, thus holding great potential in future m6A editing (Jin et al., 2021). The third challenge is that a number of m6A machineries, including writers, erasers, and readers, remain uncertain in crops. Although some m6A enzymes have been identified in several crops, such as rice, apple, and tomato, their numbers are few relative to those identified in animals. Besides the main challenges, many important questions require further explorations for better understanding and application of m6A in crop improvement. For example, what are the molecular mechanisms underlying the crosstalk among m6A machineries in the regulation of crop development and stress responses? Whether m6A participates in regulating the trade‐off between growth and resistance? In summary, the m6A‐mediated regulation in crops is an essential and complicated research area with nondeterminacy and many challenges.

In recent years, a series of bioinformatics tools were developed to simplify the analysis of m6A epitranscriptomics. RNAModR is the first publicly analytical toolkit suitable for m6A analysis (Evers et al., 2016). However, this tool focuses on the annotation of m6A distribution along transcripts, but lacks functions for m6A site calling. Subsequently, several prediction tools based on mammalian or yeast sequences were developed to predict m6A sites (Zhai et al., 2018). On that basis, a plant‐specific epitranscriptome package, named Plants Epitranscriptome Analysis (PEA), was exploited (Zhai et al., 2018). This bioinformatic toolkit is versatile and could perform the calling, prediction, and functional annotation of m6A sites produced from both common m6A‐seq and high‐throughput m6A detection techniques at single‐base resolution, such as miCLIP (Zhai et al., 2018). RNAmod is another versatile m6A toolkit, which facilitates the visualization and functional annotation of m6A modifications in multiple species including Arabidopsis (Liu and Gregory, 2019). However, whether PEA and RNAmod could be applied in numerous crop species needs to be determined. In addition, with the rapid development of m6A detection techniques, more convenient and integrated bioinformatic toolkits are required to be developed to achieve accurate identification of m6A sites, for example, those suitable for the third‐generation nanopore sequencing are currently vacant in plants.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

GQ conceived the topic. LZ, GQ, GG, RT, WW, and YW wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant Nos. 31925035 and 31871855) and the National Key Research and Development Program (grant No. 2018YFD1000200).

Zhou, L. , Gao, G. , Tang, R. , Wang, W. , Wang, Y. , Tian, S. and Qin, G. (2022) m6A‐mediated regulation of crop development and stress responses. Plant Biotechnol. J., 10.1111/pbi.13792

[Corrections added on 15 June 2022 to address comments received after first online publication: Reference citations and references have been corrected in this version]

References

- Alarcón, C.R. , Goodarzi, H. , Lee, H. , Liu, X. , Tavazoie, S. and Tavazoie, S.F. (2015) HNRNPA2B1 is a mediator of m6A‐dependent nuclear RNA processing events. Cell, 162, 1299–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, S.J. , Kramer, M.C. , Gosai, S.J. , Yu, X. , Vandivier, L.E. , Nelson, A.D.L. , Anderson, Z.D. et al. (2018) N6‐methyladenosine inhibits local ribonucleolytic cleavage to stabilize mRNAs in Arabidopsis. Cell Rep. 25, 1146–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arribas‐Hernández, L. , Bressendorff, S. , Hansen, M.H. , Poulsen, C. , Erdmann, S. and Brodersen, P. (2018) An m6A‐YTH module controls developmental timing and morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 30, 952–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arribas‐Hernández, L. , Rennie, S. , Köster, T. , Porcelli, C. , Lewinski, M. , Staiger, D. , Andersson, R. et al. (2021. a) Principles of mRNA targeting via the Arabidopsis m6A‐binding protein ECT2. eLife, 10, e72375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arribas‐Hernández, L. , Rennie, S. , Schon, M. , Porcelli, C. , Enugutti, B. , Andersson, R. , Nodine, M. D. et al. (2021. b) The YTHDF proteins ECT2 and ECT3 bind largely overlapping target sets and influence target mRNA abundance, not alternative polyadenylation. eLife, 10, e72377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista, P. , Molinie, B. , Wang, J. , Qu, K. , Zhang, J. , Li, L. , Bouley, D. et al. (2014) m6A RNA modification controls cell fate transition in mammalian embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell, 15, 707–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodi, Z. , Zhong, S. , Mehra, S. , Song, J. , Graham, N. , Li, H. , May, S. et al. (2012) Adenosine methylation in Arabidopsis mRNA is associated with the 3’ end and reduced levels cause developmental defects. Front. Plant Sci. 3, 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Q. , Wang, P. , Wu, G. , Wang, Y. , Tan, J. , Li, C. , Zhang, X. et al. (2021) Coordination of m6A mRNA methylation and gene transcriptome in rice response to cadmium stress. Rice, 14, 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, D.B.T. , Gootenberg, J.S. , Abudayyeh, O.O. , Franklin, B. , Kellner, M.J. , Joung, J. and Zhang, F. (2017) RNA editing with CRISPR‐Cas13. Science, 358, 1019–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominissini, D. , Moshitch‐Moshkovitz, S. , Schwartz, S. , Salmon‐Divon, M. , Ungar, L. , Osenberg, S. , Cesarkas, K. et al. (2012) Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A‐seq. Nature, 485, 201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, X. , Fang, T. , Liu, Y. , Wang, M. , Zang, M. , Huang, L. , Zhen, S. et al. (2020) Global profiling of N6‐methyladenosine methylation in maize callus induction. Plant Genome, 13, e20018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan, H. , Wei, L. , Zhang, C. , Wang, Y. , Chen, L. , Lu, Z. , Chen, P. et al. (2017) ALKBH10B is an RNA N6‐methyladenosine demethylase affecting Arabidopsis floral transition. Plant Cell, 29, 2995–3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edupuganti, R.R. , Geiger, S. , Lindeboom, R.G.H. , Shi, H. , Hsu, P.J. , Lu, Z. , Wang, S.‐Y. et al. (2017) N6‐methyladenosine (m6A) recruits and repels proteins to regulate mRNA homeostasis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 24, 870–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers, M. , Shafk, A. , Schumann, U. & Preiss, T. (2016) RNAModR: Functional analysis of mRNA modifcations in R. bioRxiv. Preprint: not peer reviewed.

- Fustin, J.‐M. , Doi, M. , Yamaguchi, Y. , Hida, H. , Nishimura, S. , Yoshida, M. , Isagawa, T. et al. (2013) RNA‐methylation‐dependent RNA processing controls the speed of the circadian clock. Cell, 155, 793–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia‐Campos, M.A. , Edelheit, S. , Toth, U. , Safra, M. , Shachar, R. , Viukov, S. , Winkler, R. et al. (2019) Deciphering the "m6A Code" via antibody‐independent quantitative profiling. Cell, 178, 731–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, T. , Liu, C. , Meng, F. , Hu, L. , Fu, X. , Yang, Z. , Wang, N. et al. (2021) The m6A reader MhYTP2 regulates MdMLO19 mRNA stability and antioxidant genes translation efficiency conferring powdery mildew resistance in apple. Plant Biotechnol. J. 10.1111/pbi.13733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, Y. , Li, L. , Yao, Y. , Li, Y. , Zhang, H. and Fan, M. (2021) Transcriptome‐wide N6‐methyladenosine (m6A) methylation in watermelon under CGMMV infection. BMC Plant Biol. 21, 516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y. , Sun, J. , Wu, B. , Gao, Y. , Nie, H. , Nie, Z. , Quan, S. et al. (2021) CPSF30‐L‐mediated recognition of mRNA m6A modification controls alternative polyadenylation of nitrate signaling‐related gene transcripts in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant, 14, 688–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, P.J. , Zhu, Y. , Ma, H. , Guo, Y. , Shi, X. , Liu, Y. , Qi, M. et al. (2017) YTHDC2 is an N6‐methyladenosine binding protein that regulates mammalian spermatogenesis. Cell Res. 27, 1115–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J. , Cai, J. , Park, S.J. , Lee, K. , Li, Y. , Chen, Y. , Yun, J.Y. et al. (2021a) N6‐methyladenosine mRNA methylation is important for salt stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 106, 1759–1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J. , Cai, J. , Umme, A. , Chen, Y. , Xu, T. and Kang, H. (2021b) Unique features of mRNA m6A methylomes during expansion of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruits. Plant Physiol. 10.1093/plphys/kiab509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H. , Weng, H. , Sun, W. , Qin, X.I. , Shi, H. , Wu, H. , Zhao, B.S. et al. (2018) Recognition of RNA N6‐methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nat. Cell Biol. 20, 285–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. , Zheng, P. , Liu, X. , Chen, H. and Tu, J. (2021) OseIF3h regulates plant growth and pollen development at translational level presumably through interaction with OsMTA2. Plants (Basel), 10, 1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia, G. , Fu, Y.E. , Zhao, X.U. , Dai, Q. , Zheng, G. , Yang, Y. , Yi, C. et al. (2011) N6‐methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity‐associated FTO. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 885–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S. , Lin, Q. , Luo, Y. , Zhu, Z. , Liu, G. , Li, Y. , Chen, K. et al. (2021) Genome‐wide specificity of prime editors in plants. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 1292–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, M.C. , Janssen, K.A. , Palos, K. , Nelson, A.D.L. , Vandivier, L.E. , Garcia, B.A. , Lyons, E. et al. (2020) N6‐methyladenosine and RNA secondary structure affect transcript stability and protein abundance during systemic salt stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Direct, 4, e00239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. , Shi, J. , Yu, L. , Zhao, X. , Ran, L. , Hu, D. and Song, B. (2018) N6‐methyl‐adenosine level in Nicotiana tabacum is associated with tobacco mosaic virus. Virol. J. 15, 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z. , Riaz, A. , Chachar, S. , Ding, Y. , Du, H. and Gu, X. (2020) Epigenetic modifications of mRNA and DNA in plants. Mol. Plant, 13, 14–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S. , Choe, J. , Du, P. , Triboulet, R. and Gregory, R.I. (2016) The m6A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes translation in human cancer cells. Mol. Cell, 62, 335–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder, B. , Grozhik, A.V. , Olarerin‐George, A.O. , Meydan, C. , Mason, C.E. and Jaffrey, S.R. (2015) Single‐nucleotide‐resolution mapping of m6A and m6Am throughout the transcriptome. Nat. Methods, 12, 767–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G. , Wang, J. and Hou, X. (2020) Transcriptome‐wide N6‐methyladenosine (m6A) methylome profiling of heat stress in pak‐choi (Brassica rapa ssp. chinensis). Plants (Basel), 9, 1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. , Yue, Y. , Han, D. , Wang, X. , Fu, Y.E. , Zhang, L. , Jia, G. et al. (2014) A METTL3‐METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6‐adenosine methylation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 93–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N. , Dai, Q. , Zheng, G. , He, C. , Parisien, M. and Pan, T. (2015) N6‐methyladenosine‐dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA‐protein interactions. Nature, 518, 560–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q. and Gregory, R.I. (2019) RNAmod: an integrated system for the annotation of mRNA modifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W548–W555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, G.‐Z. , MacQueen, A. , Zheng, G. , Duan, H. , Dore, L.C. , Lu, Z. , Liu, J. et al. (2014) Unique features of the m6A methylome in Arabidopsis thaliana . Nat. Commun. 5, 5630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J. , Wang, M. , Jia, G. and He, Y. (2021) Transcriptome‐wide analysis of epitranscriptome and translational efficiency associated with heterosis in maize. J. Exp. Bot. 72, 2933–2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J. , Wang, Y. , Wang, M. , Zhang, L. , Peng, H. , Zhou, Y. , Jia, G. et al. (2020) Natural variation in RNA m6A methylation and its relationship with translational status. Plant Physiol. 182, 332–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, K. , Han, J. , Zhang, Z. , Li, H. , Zhao, Y. , Zhu, Q. , Xie, Y. et al. (2021) OsEDM2L mediates m6A of EAT1 transcript for proper alternative splicing and polyadenylation regulating rice tapetal degradation. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 63, 1982–1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao, X. , Hou, N. , Liu, Z. and He, J. (2021) Profiling of N6‐methyladenosine (m6A) modification landscape in response to drought stress in apple (Malus prunifolia (Willd.). Borkh). Plants (Basel), 11, 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, K.D. , Saletore, Y. , Zumbo, P. , Elemento, O. , Mason, C.E. and Jaffrey, S.R. (2012) Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3’ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell, 149, 1635–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Z. , Zhang, T. , Qi, Y. , Song, J. , Han, Z. and Ma, C. (2020) Evolution of the RNA N6‐methyladenosine methylome mediated by genomic duplication. Plant Physiol. 182, 345–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Z. , Zhang, T. , Xie, B. , Qi, Y. and Ma, C. (2022) Evolutionary implications of the RNA N6‐methyladenosine methylome in plants. Mol. Biol. Evol. 39, msab299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, M.T. , Knop, K. , Sherwood, A.V. , Schurch, N.J. , Mackinnon, K. , Gould, P.D. , Hall, A.J. et al. (2020) Nanopore direct RNA sequencing maps the complexity of Arabidopsis mRNA processing and m6A modification. eLife, 9, e49658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil, D.P. , Chen, C. , Pickering, B.F. , Chow, A. , Jackson, C. , Guttman, M. and Jaffrey, S.R. (2016) m6A RNA methylation promotes XIST‐mediated transcriptional repression. Nature, 537, 369–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ping, X.‐L. , Sun, B.‐F. , Wang, L.U. , Xiao, W. , Yang, X. , Wang, W.‐J. , Adhikari, S. et al. (2014) Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6‐methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res. 24, 177–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontier, D. , Picart, C. , El Baidouri, M. , Roudier, F. , Xu, T. , Lahmy, S. , Llauro, C. et al. (2019) The m6A pathway protects the transcriptome integrity by restricting RNA chimera formation in plants. Life Sci. Alliance, 2, e201900393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratanwanich, P.N. , Yao, F. , Chen, Y. , Koh, C.W.Q. , Wan, Y.K. , Hendra, C. , Poon, P. et al. (2021) Identification of differential RNA modifications from nanopore direct RNA sequencing with xPore. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 1394–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roundtree, I.A. , Luo, G.‐Z. , Zhang, Z. , Wang, X. , Zhou, T. , Cui, Y. , Sha, J. et al. (2017) YTHDC1 mediates nuclear export of N6‐methyladenosine methylated mRNAs. eLife, 6, e31311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Růžička, K. , Zhang, M. , Campilho, A. , Bodi, Z. , Kashif, M. , Saleh, M. , Eeckhout, D. et al. (2017) Identification of factors required for m6A mRNA methylation in Arabidopsis reveals a role for the conserved E3 ubiquitin ligase HAKAI. New Phytol. 215, 157–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scutenaire, J. , Deragon, J. M. , Jean, V. , Benhamed, M. , Raynaud, C. , Favory, J. J. , Merret, R. et al. (2018) The YTH domain protein ECT2 is an m6A reader required for normal trichome branching in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 30, 986–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y. , Wong, C.E. , Shen, L. and Yu, H. (2021) N6‐methyladenosine modification underlies messenger RNA metabolism and plant development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 63, 102047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, L. , Liang, Z. , Gu, X. , Chen, Y. , Teo, Z.W. , Hou, X. , Cai, W. et al. (2016) N6‐methyladenosine RNA modification regulates shoot stem cell fate in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell, 38, 186–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H. , Wei, J. and He, C. (2019a) Where, when, and how: context‐dependent functions of rna methylation writers, readers, and erasers. Mol. Cell, 74, 640–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y. , Wang, H. , Wang, J. , Liu, X. , Lin, F. and Lu, J. (2019b) N6‐methyladenosine RNA methylation is involved in virulence of the rice blast fungus Pyricularia oryzae (syn. Magnaporthe oryzae). FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 366, fny286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim, S. , Lee, H.G. , Lee, H. and Seo, P.J. (2020) H3K36me2 is highly correlated with m6A modifications in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 62, 1455–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song, P. , Yang, J. , Wang, C. , Lu, Q. , Shi, L. , Tayier, S. and Jia, G. (2021) Arabidopsis N6‐methyladenosine reader CPSF30‐L recognizes FUE signals to control polyadenylation site choice in liquid‐like nuclear bodies. Mol. Plant, 14, 571–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J. , Bie, X. , Wang, N. , Zhang, X. and Gao, X. (2020) Genome‐wide identification and expression analysis of YTH domain‐containing RNA‐binding protein family in common wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 20, 351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian, S. , Wu, N. , Zhang, L. and Wang, X. (2021) RNA N6‐methyladenosine modification suppresses replication of rice black streaked dwarf virus and is associated with virus persistence in its insect vector. Mol. Plant Pathol. 22, 1070–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Y. , Tang, K. , Zhang, D. , Xie, S. , Zhu, X. , Wang, Z. and Lang, Z. (2015) Transcriptome‐wide high‐throughput deep m6A‐seq reveals unique differential m6A methylation patterns between three organs in Arabidopsis thaliana . Genome Biol. 16, 272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P. , Doxtader, K.A. and Nam, Y. (2016a) Structural basis for cooperative function of METTL3 and METTL14 methyltransferases. Mol. Cell, 63, 306–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. , Feng, J. , Xue, Y. , Guan, Z. , Zhang, D. , Liu, Z. , Gong, Z. et al. (2016b) Structural basis of N6‐adenosine methylation by the METTL3‐METTL14 complex. Nature, 534, 575–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. , Lu, Z. , Gomez, A. , Hon, G.C. , Yue, Y. , Han, D. , Fu, Y.E. et al. (2014) N6‐methyladenosine‐dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature, 505, 117–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. , Simen Zhao, B. , Roundtree Ian, A. , Lu, Z. , Han, D. , Ma, H. , Weng, X. et al. (2015) N6‐methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell, 161, 1388–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L. , Song, P. , Wang, Y. , Lu, Z. , Tang, Q. , Yu, Q. , Xiao, Y. et al. (2018) The m6A reader ECT2 controls trichome morphology by affecting mRNA stability in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 30, 968–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen, J. , Lv, R. , Ma, H. , Shen, H. , He, C. , Wang, J. , Jiao, F. et al. (2018) ZC3H13 regulates nuclear RNA m6A methylation and mouse embryonic stem cell self‐renewal. Mol. Cell, 69, 1028–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, R. , Li, A. , Sun, B. , Sun, J.‐G. , Zhang, J. , Zhang, T. , Chen, Y. et al. (2019) A novel m6A reader PRRC2A controls oligodendroglial specification and myelination. Cell Res. 29, 23–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W. , Adhikari, S. , Dahal, U. , Chen, Y.‐S. , Hao, Y.‐J. , Sun, B.‐F. , Sun, H.‐Y. et al. (2016) Nuclear m6A reader YTHDC1 regulates mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell, 61, 507–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J. , Hua, K. and Lang, Z. (2019) Genome editing for horticultural crop improvement. Hortic. Res. 6, 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D. , Xu, H. , Liu, Y. , Li, M. , Ali, M. , Xu, X. and Lu, G. (2021) RNA N6‐methyladenosine responds to low‐temperature stress in tomato anthers. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 687826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q. , Liu, S. , Yu, L.U. , Xiao, Y.U. , Zhang, S. , Wang, X. , Xu, Y. et al. (2021) RNA demethylation increases the yield and biomass of rice and potato plants in field trials. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 1581–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue, H. , Nie, X. , Yan, Z. and Weining, S. (2019) N6‐methyladenosine regulatory machinery in plants: composition, function and evolution. Plant Biotechnol. J. 17, 1194–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Y. , Liu, J. , Cui, X. , Cao, J. , Luo, G. , Zhang, Z. , Cheng, T. et al. (2018) VIRMA mediates preferential m6A mRNA methylation in 3’ UTR and near stop codon and associates with alternative polyadenylation. Cell Discov. 4, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, J. , Song, J. , Cheng, Q. , Tang, Y. and Ma, C. (2018) PEA: An integrated R toolkit for plant epitranscriptome analysis. Bioinformatics, 34, 3747–3749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C. , Samanta, D. , Lu, H. , Bullen, J.W. , Zhang, H. , Chen, I. , He, X. et al. (2016) Hypoxia induces the breast cancer stem cell phenotype by HIF‐dependent and ALKBH5‐mediated m6A demethylation of NANOG mRNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 113, E2047–E2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F. , Zhang, Y.‐C. , Liao, J.‐Y. , Yu, Y. , Zhou, Y.‐F. , Feng, Y.‐Z. , Yang, Y.‐W. et al. (2019a) The subunit of RNA N6‐methyladenosine methyltransferase OsFIP regulates early degeneration of microspores in rice. PLoS Genet. 15, e1008120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K. , Zhuang, X. , Dong, Z. , Xu, K. , Chen, X. , Liu, F. and He, Z. (2021a) The dynamics of N6‐methyladenine RNA modification in interactions between rice and plant viruses. Genome Biol. 22, 189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.‐Y. , Wang, Z.‐Q. , Hu, H.‐C. , Chen, Z.‐Q. , Liu, P. , Gao, S.‐Q. , Zhang, F. et al. (2021b) Transcriptome‐wide N6‐methyladenosine (m6A) profiling of susceptible and resistant wheat varieties reveals the involvement of variety‐specific m6A modification involved in virus‐host interaction pathways. Front. Microbiol. 12, 656302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. , Chen, L. , Zhao, Y. , Yang, C. , Roundtree, I.A. , Zhang, Z. , Ren, J. et al. (2019b) Single‐base mapping of m6A by an antibody‐independent method. Sci Adv. 5, eaax0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.U. , Yang, Y. , Sun, B.‐F. , Shi, Y. , Yang, X. , Xiao, W. , Hao, Y.‐J. et al. (2014) FTO‐dependent demethylation of N6‐methyladenosine regulates mRNA splicing and is required for adipogenesis. Cell Res. 24, 1403–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, G. , Dahl, J. , Niu, Y. , Fedorcsak, P. , Huang, C.‐M. , Li, C. , Vågbø, C. et al. (2013) ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol. Cell, 49, 18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H. , Sun, X. , Zhang, X. and Sui, N. (2020) m6A editing: New tool to improve crop quality? Trends Plant Sci. 25, 859–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H. , Sun, X. , Li, J. , Song, Y. , Song, J. , Wang, F. , Liu, L. et al. (2021) Analysis of N6‐methyladenosine reveals a new important mechanism regulating the salt tolerance of sweet sorghum. Plant Sci. 304, 110801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, S. , Li, H. , Bodi, Z. , Button, J. , Vespa, L. , Herzog, M. and Fray, R.G. (2008) MTA is an Arabidopsis messenger RNA adenosine methylase and interacts with a homolog of a sex‐specific splicing factor. Plant Cell, 20, 1278–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L. , Tang, R. , Li, X. , Tian, S. , Li, B. and Qin, G. (2021) N6‐methyladenosine RNA modification regulates strawberry fruit ripening in an ABA‐dependent manner. Genome Biol. 22, 168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L. , Tian, S. and Qin, G. (2019) RNA methylomes reveal the m6A‐mediated regulation of DNA demethylase gene SlDML2 in tomato fruit ripening. Genome Biol. 20, 156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]