Significance Statement

AKI impairs excretory function, but also leaves a damaged kidney. We demonstrate that a single episode of unilateral ischemia-reperfusion injury significantly promotes atherosclerotic plaque formation in mice. Renal inflammation preceded expression of myeloid and T cell genes in the atherosclerotic aorta. The chemokine receptor CCR2 was instrumental in inflammatory monocyte recruitment to the kidney, renal and aortic inflammatory macrophage marker CD11c expression, and enhanced aortic plaque formation after AKI. Delineating underlying mechanisms in atherosclerosis support the concept of a “toxic kidney” that promotes remote inflammation after ischemic reperfusion injury.

Keywords: arteriosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, chronic inflammation, renal ischemia, macrophages, acute kidney injury

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

The risk of cardiovascular events rises after AKI. Leukocytes promote atherosclerotic plaque growth and instability. We established a model of enhanced remote atherosclerosis after renal ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury and investigated the underlying inflammatory mechanisms.

Methods

Atherosclerotic lesions and inflammation were investigated in native and bone marrow–transplanted LDL receptor–deficient (LDLr−/−) mice after unilateral renal IR injury using histology, flow cytometry, and gene expression analysis.

Results

Aortic root atherosclerotic lesions were significantly larger after renal IR injury than in controls. A gene expression screen revealed enrichment for chemokines and their cognate receptors in aortas of IR-injured mice in early atherosclerosis, and of T cell–associated genes in advanced disease. Confocal microscopy revealed increased aortic macrophage proximity to T cells. Differential aortic inflammatory gene regulation in IR-injured mice largely paralleled the pattern in the injured kidney. Single-cell analysis identified renal cell types that produced soluble mediators upregulated in the atherosclerotic aorta. The analysis revealed a marked early increase in Ccl2, which CCR2+ myeloid cells mainly expressed. CCR2 mediated myeloid cell homing to the post-ischemic kidney in a cell-individual manner. Reconstitution with Ccr2−/− bone marrow dampened renal post-ischemic inflammation, reduced aortic Ccl2 and inflammatory macrophage marker CD11c, and abrogated excess aortic atherosclerotic plaque formation after renal IR.

Conclusions

Our data introduce an experimental model of remote proatherogenic effects of renal IR and delineate myeloid CCR2 signaling as a mechanistic requirement. Monocytes should be considered as mobile mediators when addressing systemic vascular sequelae of kidney injury.

AKI frequently affects patients who are critically ill, especially in the intensive care setting. For the majority of patients, renal function recovers and patients require RRT only briefly, if at all. However, AKI significantly increases all-cause mortality. Remote adverse effects influence a range of organs.1,2

An elevated cardiovascular risk after survived AKI was observed in meta-analyses including >50,000 patients.3–5 This is supported further by a more recently reported large cohort.6 The effect of CKD on cardiovascular disease is clearly established.7–9 Studies consistently demonstrate an association of CKD with cardiovascular disease after correction for common risk factors at an eGFR of ≤60 ml/min.10 In the setting of AKI, stratification for severity and common risk factors appears to be more challenging than in CKD, given the smaller patient numbers and frequently incomplete follow-up data. In addition, the definition of AKI includes patients with a functional decrease in urine output and those with structural renal injury. To distinguish these entities can be clinically challenging, especially at mild disease stages. Animal models were developed to investigate remote AKI effects and underlying mechanisms in lung, brain, gut, and granulopoiesis.2,11–14 Such a model is also required for systematic evaluation of atherosclerosis after AKI.

Inflammatory leukocytes are central in atherosclerosis initiation and progression.15 Arterial wall leukocyte numbers increase in patients with CKD stages 3–4.16–18 Also, in murine atherosclerosis models, moderate reduction of kidney function by unilateral nephrectomy enhanced atherosclerotic inflammation.19–22 Recent clinical trials demonstrate that patients with CKD receiving anti–IL-1 and anti–IL-6 anti-cytokine therapy experience fewer cardiovascular events.23,24 AKI not only reduces renal function, but also leaves an injured kidney in place. Renal inflammation can be detected for at least a year after a single episode of ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury.25 Whether an injured kidney modulates atherosclerotic inflammation and specific soluble or cellular mediators has not been addressed.

Monocytes are precursors of atherosclerotic plaque macrophages and myeloid antigen-presenting cells.15 The C-C motif ligand 2 (CCL2) receptor (CCR2) is highly expressed by classic, so-called inflammatory monocytes in mice and humans. It mediates their liberation from the bone marrow.26 CCL2 levels were elevated in a cohort of 3200 patients with CKD, who were investigated as part of the Dallas Heart Study, and correlated with cardiovascular death, also after correction of multiple risk factors.27 CCR2 expression on circulating monocytes correlated with human aortic wall glucose uptake, an in vivo marker of inflammation.28 Experimental pharmacologic CCL2 inhibition was only moderately beneficial in some models of severe atherosclerosis without kidney injury.29–31 The mechanistic role of CCL2 in enhanced atherosclerosis in CKD or after AKI has not been delineated.

Renal CCL2 expression rises in a multitude of kidney diseases.32 CCR2-deficient mice were protected from renal damage and inflammation after ischemia and reperfusion.33,34 Similar results were obtained using pharmacologic receptor blockers. Indeed, tubular CCL2 correlated with monocyte infiltration after renal ischemia reperfusion.35 However, the concept of detrimental renal inflammation via CCL2 was challenged by excess mortality in CCL2-deficient mice after bilateral renal IR.36 As a potential underlying mechanism, increased tubular apoptosis and more inflammatory, instead of reparative, macrophages were reported. In our recent work, we delineated differential effects of tubular and monocyte CCL2.37 Tubular CCL2 was required for renal healing after injury. How the monocytic CCR2 signal affects long-term outcome, both locally in the kidney and remotely in the atherosclerotic aorta, has not been determined.

Here, we introduce a murine model of increased atherosclerotic plaque load after a single episode of unilateral AKI. Our results show a mechanistic role for bone marrow–derived CCR2+ cells in enhanced atherosclerotic plaque size and aortic inflammation after kidney injury, without discernible effects on renal outcome. These data introduce a concept of remote inflammation for aggravation of atherosclerosis after kidney injury.

Methods

Animals

Male wild-type (CD45.1 or CD45.2), LDL receptor–deficient (LDLr−/−), and Ccr2−/− mice (both CD45.2, all on C57Bl/6 background; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were genotyped by PCR, used in age-matched groups, and kept in specific-pathogen-free conditions. Animal experiments were approved by Landesamt für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit (Lower Saxony, Germany) in accordance with the guidelines from Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Mice were kept on high-fat diet (Harlan Teklad 88137) for indicated periods of time. Euthanasia was by isoflurane overdose (5%) and ensured by cervical dislocation.

Bone Marrow Transplantation and Kidney Surgery

Mice were reconstituted with unfractionated bone marrow after lethal irradiation in a caesium-137 irradiator. For kidney surgery, mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (125 mg/kg), xylazine (12.5 mg/kg), and atropine (0.025 mg/kg). The vessels of the left kidney were clamped for 27 minutes, taking care to avoid damage of the adrenal gland and surrounding organs. Control mice received an identical abdominal incision and brief handling of the kidney. Postoperative analgesia was with subcutaneous metamizole, as needed. Kidney surgeries were performed 2 weeks after bone marrow transplantation.

Serum urea, creatinine, electrolytes, and lipids were measured in an OlympusAU400 ChemistryImmunoAnalyzer (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany), and full blood counts were assessed in an automated analyzer (VetABC; ScilVet, Viernheim, Germany).

Histology and Flow Cytometry

Atherosclerotic lesion size was assessed in frozen 5-μm sections, obtained in 50-μm intervals, stained with Oil Red O staining with hematoxylin and light green counterstain, as described.19 Extent of renal damage was determined as proportion of intact tubuli in cortex and outer stripe of outer medulla in hematoxylin and eosin–stained whole kidney images. Image analysis was conducted in GIMP (version 2.10). Antibodies, flow cytometry, and microscopy equipment are detailed in the Supplemental Appendix.

RNA Isolation, Quantitative PCR, and Microarray-Based mRNA Expression Analysis

RNA isolation, primer sequences, microarray specifications (ID026652; Agilent Technologies), and tissue preparation for microarray and single-cell analysis methods are detailed in the Supplemental Appendix.

For analysis of aortic gene expression, aortas of three male mice per condition were pooled. Immune genes (ILs and IL receptors, chemokines, integrins, and CD molecules) with a baseline above detection limit were analyzed. For string analysis (https://string-db.org), all genes upregulated at least two-fold in aortas from IR mice after 3 or 10 weeks of a high-fat diet, compared with 3- or 10-week control aortas, are shown. Interactions and similarities are indicated as follows: cyan for curated databases, pink for experiments, green for gene neighborhood, light green for text mining, and black for coexpression. Long-term renal post-ischemic gene expression was extracted from Lui et al.25 (n=3–4 per time point).

Renal single-cell sequencing data from the kidneys of three male C57Bl/6 mice 7 days after unilateral renal IR and control mice without surgery were analyzed for target gene expression in cell types identified using Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection. We analyzed renal RNA sequencing data after IR and in controls from a public database25 and IR kidneys from male LDLr−/− mice reconstituted with wild-type and Ccr2−/− bone marrow after 3 weeks on a high-fat diet. In mice reconstituted with wild-type versus Ccr2−/− bone marrow, regulated gene groups among ≥1.5-fold upregulated and ≥0.75-fold downregulated genes were identified using the PANTHER database (annotation dataset: complete Gene Ontology biologic processes).

Statistical Analysis

For continuous biologic variables, a normal distribution was assumed because most follow a Gaussian distribution. Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism (version 8). Two-tailed t test with a Welch correction in case of unequal variance was used to compare two conditions. If more than two conditions were compared, the Sidak or Dunnett test of selected conditions was applied after ANOVA. Data are expressed as mean±SEM. P values <0.05 were considered significant and are indicated as *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001.

Results

Renal IR Injury Promotes Atherosclerotic Plaque Development

To investigate the effect of a damaged kidney on atherosclerosis development, we subjected LDLr−/− mice to unilateral renal IR injury (Figure 1A). After 10 weeks on a high-fat diet for induction of atherosclerotic lesions, animals were euthanized. Body and spleen weights did not differ significantly between the groups (Supplemental Table 1). After IR, the contralateral kidney expectedly hypertrophied. Serum levels of the major proatherogenic factors, triglycerides, cholesterol, and phosphate did not differ. Serum urea, but not creatinine, significantly increased, consistent with a mildly impaired excretory renal function. Differential blood counts were unaffected by the procedure.

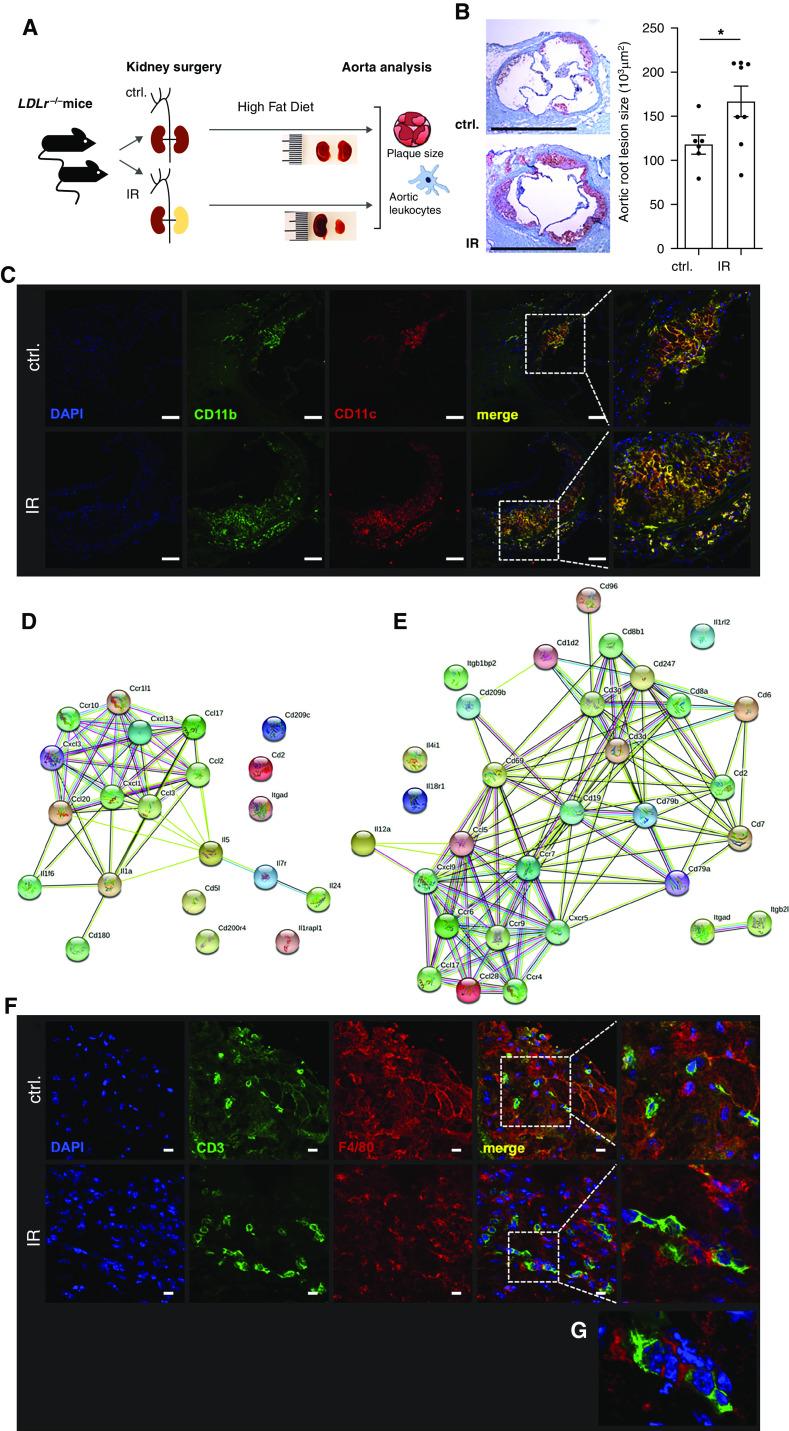

Figure 1.

Renal IR injury increases atherosclerotic lesion size and inflammation. (A–G) Male LDLr−/− mice were subjected to unilateral renal IR injury. (A) One week later, mice started being fed a high-fat diet for induction of atherosclerotic lesions. (B) Aortic root atherosclerotic lesion size was assessed after 10 weeks. Oil Red O with hematoxylin and eosin counterstain. Typical examples are shown with n=6–8 per group from three independent experiments (t test). Scale bars, 1 mm. *P<0.05. (C) Myeloid cells in the atherosclerotic plaques expressed antigen-presenting cell marker CD11c. Typical examples are shown. Blue, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI); green, CD11b; red, CD11c. Scale bars, 100 μm. (D and E) Aortic gene expression was determined by gene array after 3 (D) and 10 (E) weeks of a high-fat diet in LDLr−/− mice with preceding IR injury and compared with otherwise identically treated control-operated animals. Upregulated immune genes and their interactions are shown, as defined in Methods. (F and G) Close spatial proximity of T cells and myeloid cells in the atherosclerotic aortic root after 10 weeks of high-fat diet. Typical examples of control (ctrl) and IR mice are shown. (G) Three-dimensional reconstruction of an IR mouse. Blue, DAPI; green, CD3; red, F4/80. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Atherosclerotic lesion size was assessed in the aortic root (Figure 1B). Lesion size was significantly larger in mice after AKI by unilateral IR than in control-operated mice. Confocal microscopy after immunostaining revealed marked accumulation of CD11b+ myeloid cells expressing the inflammatory macrophage and antigen-presenting cell marker CD11c in the plaques after IR (Figure 1C, specificity controls in Supplemental Figure 1A). These data demonstrate enhanced atherosclerosis in animals with preceding renal injury.

Upregulation of Aortic Chemokine and T Cell Genes after Renal IR Injury

To delineate differentially regulated inflammatory pathways after AKI, we analyzed atherosclerotic aortas by gene array. Aortas were harvested early and late during atherosclerosis development (i.e., after 3 and 10 weeks on a high-fat diet). Similar to the later time point (Supplemental Table 1), mice at the early stage showed contralateral renal hypertrophy, elevated urea, nonsignificant changes in creatinine, and no significant alterations in lipid levels or complete blood counts (Supplemental Table 2).

Inflammatory gene expression in the atherosclerotic aortas after AKI was compared with otherwise identically treated animals after control surgery. String analysis revealed upregulation of chemokines and their cognate receptors in early atherosclerosis (Figure 1D). In established plaques, in addition to chemokine pathways, T cell genes were upregulated (Figure 1E). Indeed, confocal imaging and three-dimensional reconstruction of the plaque revealed close spatial proximity of CD3+ T cells and F4/80+ macrophages in the established aortic root plaques in mice after an AKI episode (Figure 1, F and G). This was not observed in control animals.

This analysis shows upregulation of chemokine, followed by T cell pathways in response to AKI in the atherosclerotic aorta.

Parallel Regulation of Inflammatory Genes in the Atherosclerotic Aorta and the Post-Ischemic Kidney

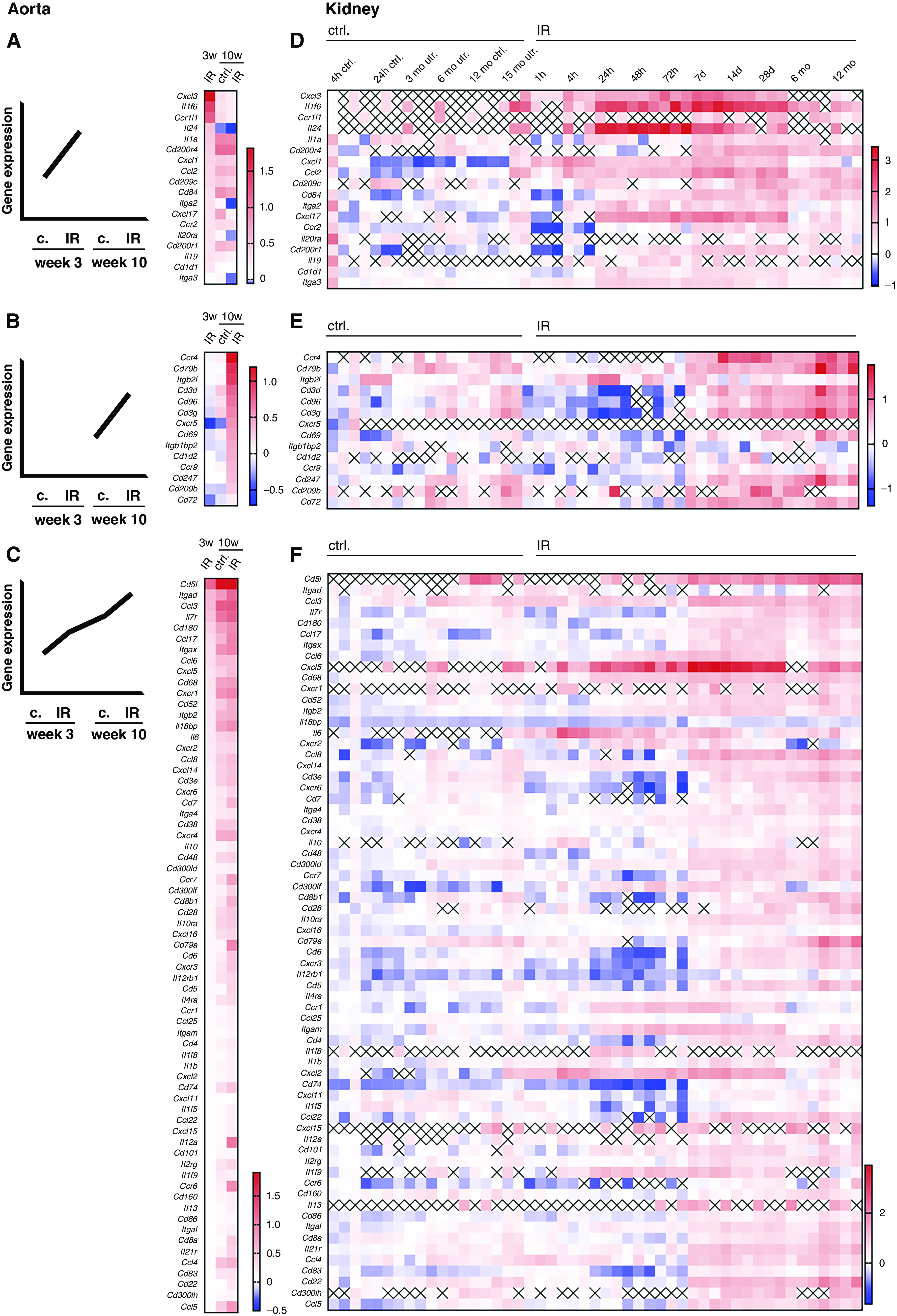

To identify candidate pathophysiologic links between renal post-ischemic and aortic atherosclerotic inflammation, we compared differentially regulated aortic inflammatory genes with a dataset of longitudinal measurements in the post-ischemic kidney.25

Genes were grouped according to time of their regulation during atherosclerosis development. Two-fold or more relative upregulation in aortas from AKI versus control-operated LDLr−/− mice only in early (Figure 2A) or only in established atherosclerosis (Figure 2B) is shown. These patterns were reflected in the gene regulatory pattern in the post-ischemic kidney (Figure 2, D and E) by upregulation either days (Figure 2D) or weeks (Figure 2E) after AKI. In many cases, elevated expression was sustained even a year after injury. A relatively large number of aortic inflammatory genes were upregulated both by progression of atherosclerosis and after AKI at each time point (Figure 2C). In most cases, they belong to the group affected late in the postischemic kidney and sustained their elevated expression long term (Figure 2F). We also searched for aortic genes regulated after AKI without overall change during atherosclerosis progression. Up- and downregulated genes were identified. These patterns were, however, not reflected by their renal expression (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Parallels in aortic and renal post-ischemic inflammatory gene expression. (A–C) Differentially expressed immune genes in atherosclerotic aortas from mice after renal IR and controls (c or ctrl.) were grouped in genes upregulated two-fold or more only early (3 weeks) (A), or only late (10 weeks) (B), or ≥1.5-times (C) at one time point with a continuous rise over all conditions or after AKI compared with controls, as detailed in Methods (three pooled aortas per condition). (D–F) Regulation of the aortic gene sets regulated early only (D), only late (E), or continuously (F) in post-ischemic murine kidneys (n=3–4 per time point, expression relative to baseline). x, not detected in dataset.25

Parallel regulation of inflammatory genes in the atherosclerotic aorta of mice after AKI and in the kidney itself proposes an effect of renal inflammation on the vessel.

Renal Myeloid Cells Upregulate Inflammatory Mediators That Increase in the Atherosclerotic Aorta

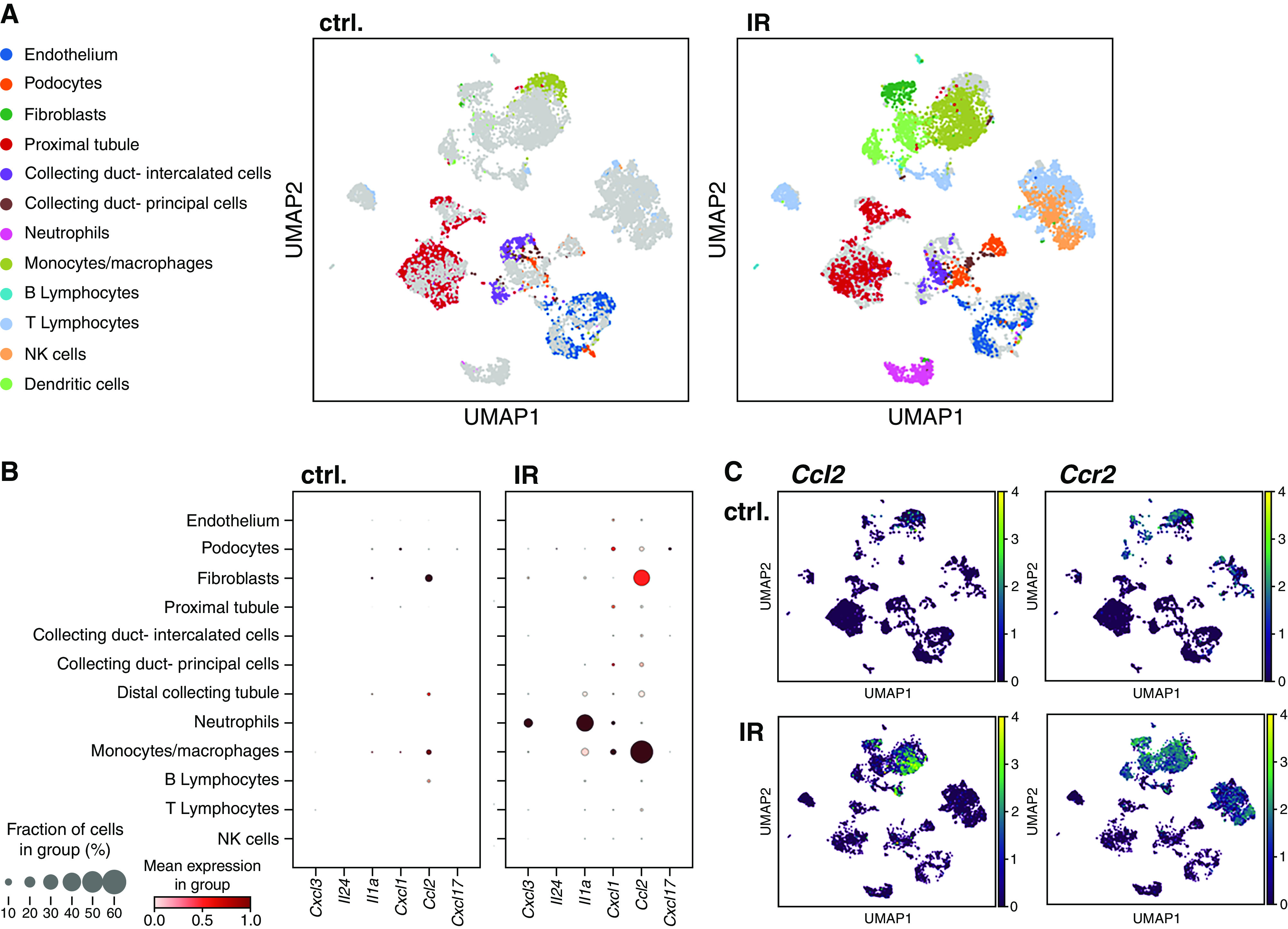

To determine how renal inflammation remotely affects the atherosclerotic aorta, we investigated which cells in the post-ischemic kidney expressed the soluble mediators markedly upregulated specifically in early atherosclerosis of mice after AKI (Figure 2A). Single-cell sequencing was used to define individual cell types. Expectedly, the number of myeloid inflammatory cells in the post-ischemic kidney increased 7 days after AKI (Figure 3A). Expression of the aortic regulated genes Cxcl3, Il24, Il1a, Cxcl1, Ccl2, and Cxcl17 was analyzed in different cell types (Figure 3B), Il19 was below the detection limit. Expression of these soluble inflammatory mediators was highest in leukocytes. Ccl2 increased most markedly (Figure 3B). Most CCL2-expressing cells also expressed its receptor CCR2 (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Inflammatory mediator expression rises in myeloid cells in the post-ischemic kidney. (A–C) Renal single-cell analysis was performed 7 days after unilateral IR in male wild-type mice. (A) Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) analysis reveals a major increase of monocytic cell abundance. (B) Expression of soluble inflammatory mediators upregulated in the atherosclerotic aorta of IR mice was assessed separately in the renal cell types. (C) Most upregulated CCL2 was predominantly found in cells that also expressed its receptor CCR2 (n=3 pooled kidneys from each condition). Ctrl., control; NK, natural killer.

These data show a significant role of CCR2+ myeloid cells in production of their ligand, CCL2, in the post-ischemic kidney.

Renal Myeloid Cell Accumulation after AKI Is Promoted by CCR2 in a Cell-Individual Manner

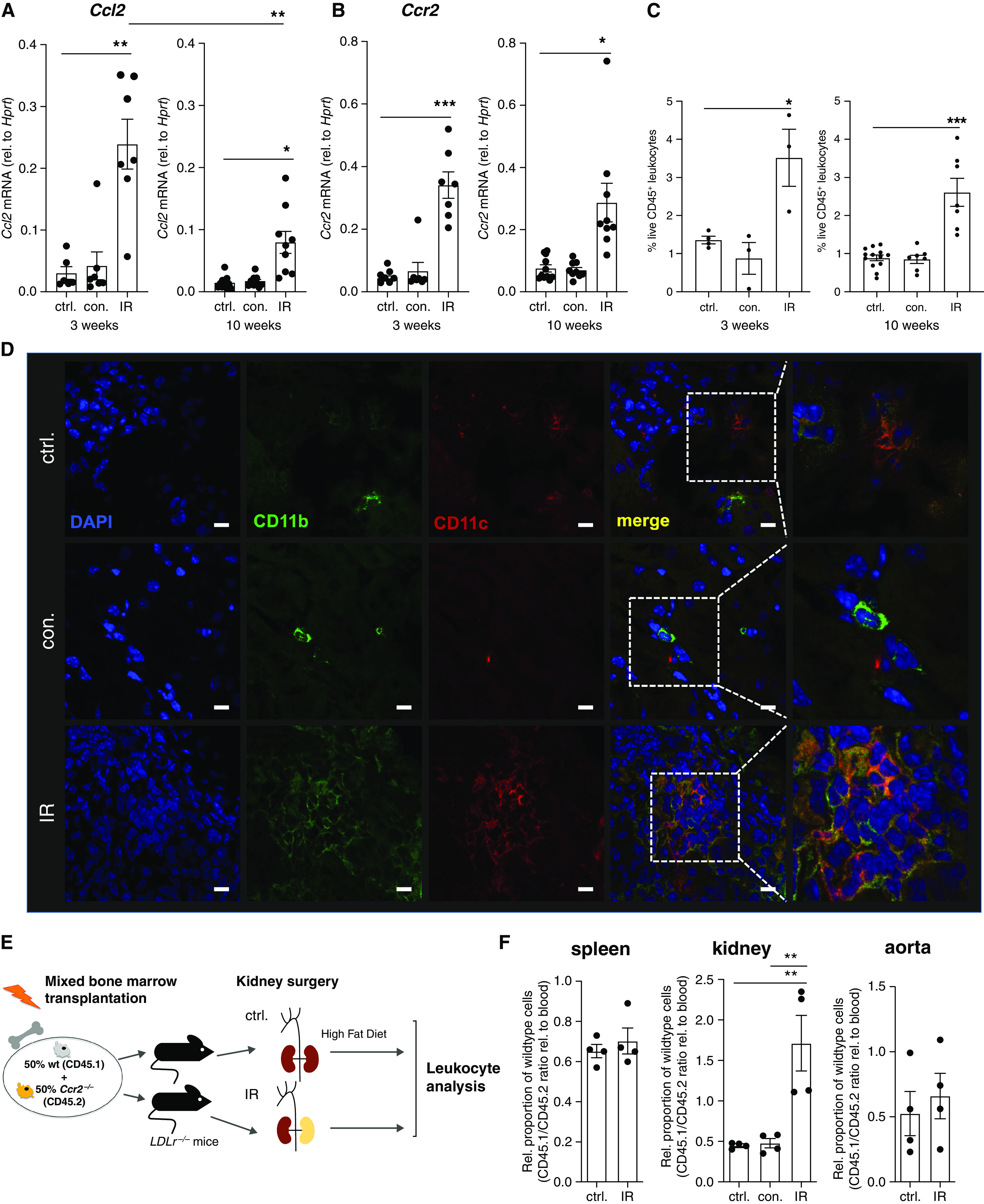

Regulation of CCL2 and its receptor CCR2 was investigated in detail during atherosclerosis development. Both were upregulated in the kidneys of LDLr−/− mice at early and late atherosclerosis stages, after 3 and 10 weeks of a high-fat diet (Figure 4, A and B). However, Ccl2 expression was significantly higher at the early than the late time point, consistent with the situation in the aorta (Figure 2). CCR2 upregulation was sustained. Consistently, persistent myeloid cell enrichment was detected by flow cytometry (Figure 4C, gating in Supplemental Figure 3). This was reflected by myeloid cell infiltration in confocal imaging (Figure 4D, specificity controls in Supplemental Figure 1B).

Figure 4.

CCR2 is persistently upregulated in the post-ischemic kidney and promotes macrophage accumulation in a cell-specific manner. (A–C) In male LDLr−/− mice after IR and controls (ctrl.), followed by 3 and 10 weeks of a high-fat diet as indicated, renal Ccl2 (A) and Ccr2 (B) mRNA expression was assessed by quantitative PCR, and live renal leukocytes were assessed by flow cytometry (C) (gating in Supplemental Figure 3). For quantitative PCR: assessment at 3 weeks, n=6–7 from three independent experiments; assessment at 10 weeks, n=9–11 from five independent experiments. For flow cytometry: assessment at 3 weeks, n=3–4 from one experiment; assessment at 10 weeks, n=7 from three independent experiments. (D) Renal CD11b+CD11c+ myeloid cell infiltration after 10 weeks of a high-fat diet, imaged by confocal microscopy. Blue, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI); green, CD11b; red, CD11c. Scale bars, 10 μm. (E and F). Male LDLr−/− mice were lethally irradiated and reconstituted with a 1:1 mixture of wild-type (wt) and Ccr2−/− bone marrow and subjected to renal IR or control surgery, as depicted in (E). Splenic, renal, and aortic live CD11b+ myeloid cells were assessed after 3 weeks of a high-fat diet by flow cytometry, and genotypes distinguished by CD45.1 and CD45.2 expression (gating in Supplemental Figure 4). n=4 per group from three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001, Dunnett test after ANOVA. con., contralateral kidney; rel., relative.

To investigate whether CCR2 was required for leukocyte accumulation after renal IR injury, we generated mixed chimeras in LDLr−/− mice using wild-type and Ccr2−/− bone marrow (Figure 4E, Supplemental Figure 4). Genotypes were distinguished by the syngenic markers CD45.1 and CD45.2. This approach allowed us to study the homing of individual cells with and without CCR2 in an identical milieu, including the presence of possible downstream mediators. Our results after 3 weeks of a high-fat diet show that CCR2 conferred an advantage in myeloid cell accumulation in the post-ischemic kidney, compared with blood, the contralateral kidney and spleen, and also the aorta (Figure 4F). This was not observed in mice that underwent control surgery and an otherwise identical treatment and demonstrates CCR2 promotes myeloid cell accumulation in a cell-individual manner after renal IR injury.

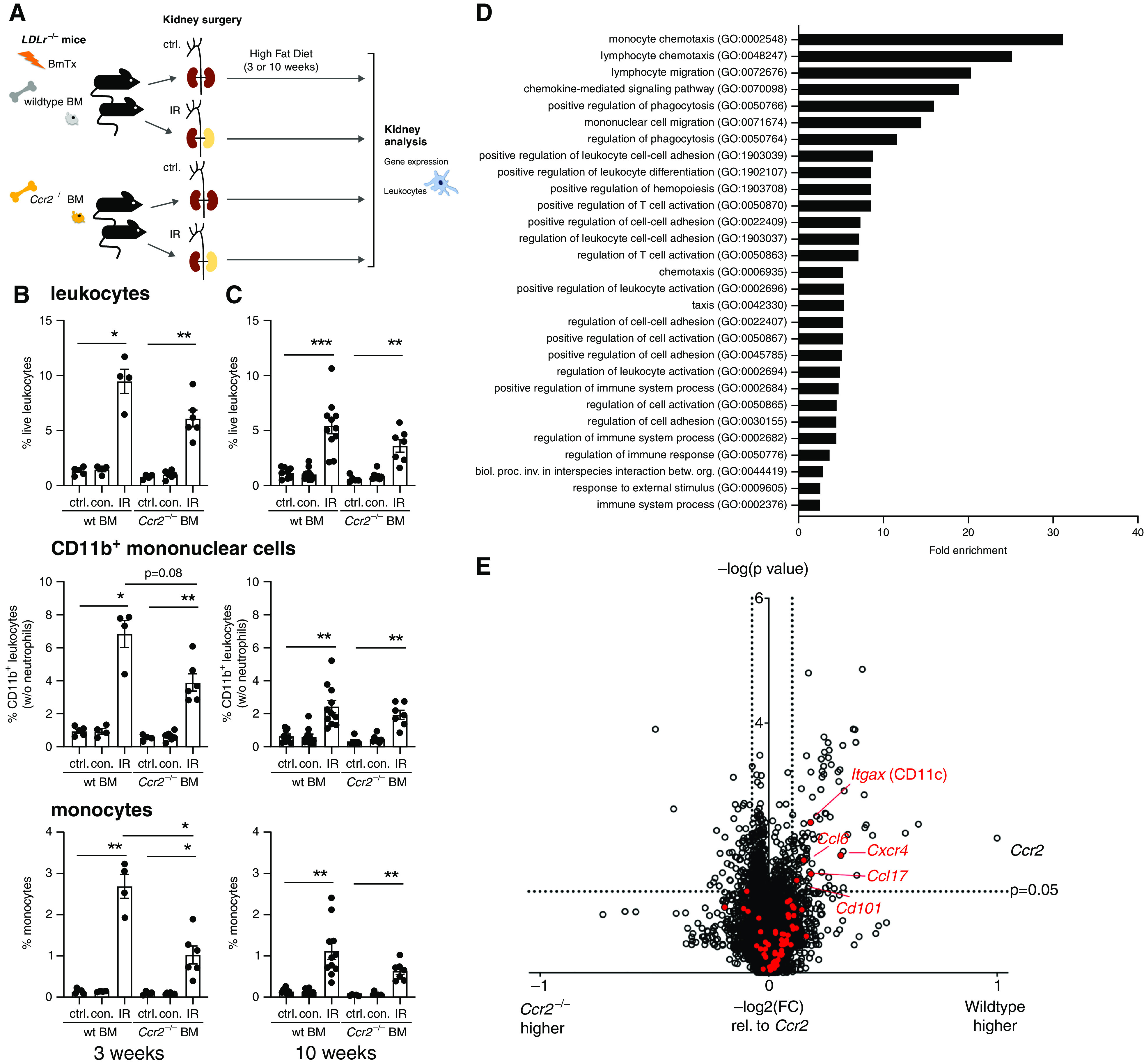

Myeloid CCR2 Promotes Leukocyte Infiltration and Inflammatory Gene Expression in the Injured Kidney

To study downstream effects of CCR2-mediated renal leukocyte accumulation, we generated complete bone marrow chimeras by reconstituting LDLr−/− mice with 100% wild-type or Ccr2−/− bone marrow (Figure 5A). The latter ablated renal Ccr2 expression, demonstrating highly effective replacement of recipient cells (Supplemental Figure 5). Expectedly, less monocytes were observed in blood in the absence of CCR2 (Supplemental Tables 3 and 4).26 Differential histologic assessment after 3 and 10 weeks of a high-fat diet revealed no difference in the proportion of intact tubuli (Supplemental Figures 6 and 7), consistent with very similar functional parameters (Supplemental Tables 3 and 4).

Figure 5.

CCR2 promotes leukocyte infiltration and inflammation after renal IR injury. (A–E) Male LDLr−/− mice underwent renal IR or control (ctrl.) surgery after reconstitution with either wild-type (wt) or Ccr2−/− bone marrow (BM), as depicted in (A). (B and C) Renal leukocytes were assessed by flow cytometry after 3 (B) and 10 (C) weeks of atherosclerosis induction by a high-fat diet. Proportions of live leukocytes, non-neutrophil CD11b+ myeloid cells, and monocytes among all cells are shown (gating strategy in Supplemental Figure 3). n=4–6 mice per group from five independent experiments in (B), n=5–11 mice per group from eight independent experiments in (C), Dunnett test after ANOVA. (D and E) Differentially regulated renal genes after reconstitution with wild-type or Ccr2−/− bone marrow and renal IR in in LDLr−/− mice were studied by microarray after 3 weeks on a high-fat diet (n=4 mice per group). (D) Functional gene groups that were significantly upregulated in kidneys in the presence of wild-type bone marrow (Fisher exact test, false discovery rate of <0.05). (E) Volcano plot of gene regulation in IR kidneys of wild-type versus Ccr2−/− bone marrow recipients. Cutoffs of ≥1.5 times up- or ≥0.75 times downregulation expressed as −log2(fold change [wild type/Ccr2−/−]) relative to −log2(fold change [Ccr2(wild type/Ccr2−/−)]) is shown, t test. Inflammatory genes continuously upregulated in the atherosclerotic aorta (Figure 2C) are marked in red; significantly regulated genes are annotated. betw., between; biol., biologic; BmTx, bone marrow transplantation; con., contralateral kidney; GO, Gene Ontology; inv., involved; org., organisms; proc., process. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001.

Renal leukocyte infiltration was characterized by flow cytometry and compared with otherwise identically treated mice reconstituted with wild-type bone marrow. IR significantly enhanced leukocyte infiltration in both genotypes early and late after injury (Figure 5, B and C). At the early time point, less monocyte infiltration and a trend toward less CD11b+ mononuclear myeloid infiltration was detected in mice reconstituted with Ccr2−/− bone marrow, consistent with the situation in mixed chimeras (Figure 4F).

To address secondary renal mediators with a potential effect on systemic atherosclerosis development, gene expression analysis was performed after 3 weeks of atherosclerosis induction. Genes relatively increased in the post-ischemic kidneys of LDLr−/− mice with wild-type bone marrow were enriched for immune system and inflammatory pathways (Figure 5D). We next investigated regulation of aortic inflammatory gene groups with differential regulatory patterns depicted in Figure 2 in the kidney. In the presence of wild-type bone marrow, a number of genes were overexpressed that had been found to be upregulated in the atherosclerotic aortas of IR mice at the early and the late time point, and to also rise continuously with atherosclerosis development (Figures 2, C and F, and 5E), but not in the other patterns. Significant upregulation was found for Itgax, which codes for CD11c, Cxcr4, Ccl6, Ccl17, and Cd101 within in this gene group.

In summary, myeloid CCR2 upregulates an inflammatory transcriptome in the post-ischemic kidney in proatherogenic conditions.

Myeloid CCR2 Mediates Excess Atherosclerosis after AKI

To test for a mechanistic role of CCR2 in excess aortic plaque growth, lesions were analyzed in LDLr−/− mice lethally irradiated and reconstituted with either wild-type or Ccr2−/− bone marrow before AKI after 10 weeks of a high-fat diet (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Myeloid CCR2 is required for enhanced atherosclerotic plaque formation after AKI. (A–G) Male LDLr−/− mice were lethally irradiated and reconstituted with either wild-type (wt) or Ccr2−/− bone marrow (BM) before renal IR or control (ctrl.) surgery. (A) Atherosclerosis was assessed after 10 weeks of a high-fat diet. (B) Aortic root atherosclerotic lesion size was assessed. n=6–8 mice from five independent experiments, Dunnett test after ANOVA. Aortic Ccr2 (C), Ccl2 (D), and Itgax (E) (CD11c) mRNA expression was assessed by quantitative PCR. n=3–5 mice per group from five independent experiments, Sidak test after ANOVA. (F and G) Confocal imaging after immunostaining of the aortic root for T cells and myeloid cells. In (F), green represents CD3 and red represents F4/80. In (G), green represents CD11b, red represents CD11c, and blue represents 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Scale bars, 10 μm. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001. BmTx, bone marrow transplantation; Rel., relative.

Aortic root lesion size significantly increased after IR in mice reconstituted with wild-type bone marrow (Figure 6B). This is in line with our results in native LDLr−/− mice (Figure 1). The absence of myeloid CCR2 completely abrogated the enhancement of atherosclerosis after AKI. AKI significantly promoted aortic expression of Ccr2 and its ligand, Ccl2, in LDLr−/− mice reconstituted with wild-type bone marrow (Figure 6, C and D). After reconstitution with CCR2-deficient bone marrow, aortic CCR2 expression remained below the detection limit, consistent with the results in the kidney (Supplemental Figure 5), indicating highly effective reconstitution. The increase of aortic Ccl2 after AKI was abrogated in the absence of bone marrow CCR2 (Figure 6D).

Also, aortic CD11c mRNA was depressed in the absence of CCR2 (Figure 6E). We used confocal microscopy to further investigate immune cells in the atherosclerotic plaques. Less CD11b+CD11c+ macrophages and less spatial proximity of CD3+ T cells and F4/80+ macrophages were observed in the absence of bone marrow CCR2 (Figure 6, F and G).

These experiments determine a mechanistic role for myeloid CCR2 in enhanced atherosclerosis and aortic CD11c expression after renal ischemic injury.

Discussion

Here, we describe a novel in vivo model of remote atherosclerosis enhancement after AKI. Our data identify myeloid CCR2 signaling as a mechanistic requirement.

Clinical data indicate an elevated cardiovascular risk during follow-up after AKI.3–6 In our experiments, unilateral renal IR injury significantly enhanced atherosclerotic lesion size in LDLr−/− mice. This occurred despite an only moderate increase in serum urea and no significant change in serum creatinine (i.e., without a major loss of excretory kidney function). Our data demonstrate ischemic AKI causes a parallel rise of inflammatory mediators in the post-ischemic kidney and the atherosclerotic aorta. The clinical definition of AKI as decreased urine output and rise in serum creatinine includes a physiologic response to prerenal volume depletion without structural renal damage and acute tubular injury. There is a dichotomy in renal gene regulation in these conditions: although IR injury promoted renal inflammatory gene expression, renal response to volume depletion suppressed it.37 In clinical practice, these entities are not always clearly separated, especially in less severe forms. Underlying pathology needs to be considered when evaluating the effect of AKI on patients’ cardiovascular outcomes.3–5

Ablation of the CCL2/MCP-1 receptor CCR2 on myeloid cells prevented aggravation of atherosclerosis after AKI in our experiments. Despite encouraging early results of reduced atherosclerotic lesion size in CCR2-deficient mice,38 only some pharmacologic interventions29–31 decreased atherosclerotic plaque size in the absence of kidney injury. Consistently in our experimental setup, reduction of plaque size by the deletion of bone marrow CCR2 remained nonsignificant in the absence of kidney injury. This may suggest that this receptor’s proatherosclerotic function is exacerbated in the presence of local inflammation, as in our data for AKI and possibly beyond. Our results add a mechanism to the correlation of systemically elevated CCL2 in CKD with cardiovascular death,27 which remained stable after correction of multiple risk factors, and the fact that CCR2 expression associated with vascular inflammation in humans with excess risk, including CKD.28 Our results suggest CCR2 inhibition should be tested as an anti-inflammatory intervention targeted to this patient group. Timing and duration will need to be carefully evaluated, given the long-term kinetics of atherosclerotic lesion formation.

Myeloid CCR2 significantly promoted renal monocyte recruitment in response to IR and was required for enhanced atherosclerotic lesion size. Renal, but not aortic, cell recruitment was mediated on an individual monocyte level by CCR2. Our results rather propose that separate secondary mediators are instrumental for aortic myeloid cell accumulation. Indeed, differential recruitment of inflammatory cells by CCR2+ and CCR2− macrophages has recently been observed after myocardial injury.39 Underlying downstream mechanisms are elusive as yet. We started to address these mechanisms and found upregulation of a range of genes that also increase in the atherosclerotic aorta, including antigen-presenting cell marker CD11c, in agreement with kidneys of completely CCR2-deficient mice.34 Our data are consistent with a model in which CCR2 promotes monocyte passage into a pathologically altered kidney, which, in turn, modulates secondary cellular or soluble mediators in a proatherogenic way that results in excess atherosclerotic lesion size. Whether this or similar mechanisms also apply to other types of kidney injury, such as drug toxicity or glomerular diseases, remains to be investigated.

Regarding the kidney itself, CCL2 is a major proinflammatory factor32,34 and a biomarker of detrimental organ development.40 As a human example, tubulointerstitial CCL2 expression was elevated and closely correlated with CCR2 in diabetic nephropathy and a number of glomerulonephritides (GSE104948 and GSE104954, Pearson r=0.57, P<0.00141). Very recently, CCR2+ myeloid cells were also reported as mediators of renal aging.42 However, beyond reported detrimental effects,33,34 renal CCL2 may also affect healing after injury. We recently investigated this issue further and found that renal tubular, rather than myeloid, CCL2 was required for early macrophage influx and renal recovery.37 In this context, it is encouraging to note that, in our atherosclerotic mice, ablation of myeloid CCR2 did not significantly alter total renal CCL2 expression or renal histologic or functional outcome after AKI at either investigated time point. Alternate CCL2 receptors, such as CCR4,43 may need to be considered when studying the role of CCL2 in renal repair.

In summary, our results introduce inflammatory cell activation by the damaged kidney as a mechanism of remote organ damage.

Disclosures

S.V. Fleig reports having other interests in, or relationships with, the European Vascular Biology Organization, German Society for Microcirculation and Vascular Biology (GfMVB), German Society for Ultrasound in Medicine (DEGUM), and German Society of Nephrology (DGfN). H. Haller reports serving on speakers bureaus for Alexion, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer Pharma, Boehringer, MedWiss, Novartis, Phenos, and Vifor-Fresenius; receiving honoraria from Alexion, AstraZeneca, Bayer Pharma, Boehringer, MedWiss, Novartis, Phenos, and Vifor-Fresenius; having consultancy agreements with Alexion, AstraZeneca, Bayer Pharma, Boehringer, MedWiss, Phenos, and Vifor-Fresenius; and serving in an advisory or leadership role for Alexion, Bayer Pharma, Der Internist, and Der Nephrologe. A.M. Hüsing reports previously being employed by Bayer AG (internship from November 2018 to April 2019, not current). R. Schmitt reports receiving honoraria from Fresenius Medical Care and Otsuka Pharmaceutical. S. von Vietinghoff reports having consultancy agreements with AstraZeneca, Bayer Vital GmbH, Boehringer Ingelheim, Shionogi GmbH, and Vifor Pharma. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft under Germany’s Excellence Strategy grant EXC2151-390873048.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support by the Hannover Medical School Genomics and Microscopy Core facilities and thank Martina Flechsig and Herle Chlebusch for excellent technical work.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Author Contributions

D. DeLuca, S.V. Fleig, S. Gaedcke, H. Haller, A.M. Hüsing, S. Rong, R. Schmitt, and V.C. Wulfmeyer reviewed and edited the manuscript; D. DeLuca, S. Gaedcke, and S. von Vietinghoff were responsible for data curation; S.V. Fleig¸ A.M. Hüsing, S. Rong, and V.C. Wulfmeyer were responsible for investigation; H. Haller, A.M. Hüsing, and S. von Vietinghoff conceptualized the study; A.M. Hüsing and S. von Vietinghoff wrote the original draft; R. Schmitt was responsible for methodology; R. Schmitt and S. von Vietinghoff provided supervision; and S. von Vietinghoff was responsible for formal analysis, funding acquisition, project administration, validation, and visualization.

Data Sharing Statement

All gene expression studies have been deposited to the Gene Expression Omnibus (accessions GSE193275, GSE193469, and GSE193649).

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2022010048/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Appendix. Supplemental Methods.

Supplemental Table 1. Characteristics of LDLr−/− mice after 10 weeks of a high fat diet.

Supplemental Table 2. Characteristics of LDLr−/− mice after 3 weeks of a high fat diet.

Supplemental Table 3. LDLr−/− mice after reconstitution with wild-type of Ccr2−/− bone marrow followed by renal ischemia reperfusion or control surgery and 10 weeks of a high fat diet.

Supplemental Table 4. LDLr−/− mice after reconstitution with wild-type or Ccr2−/− bone marrow followed by renal ischemia reperfusion or control surgery and 3 weeks of a high fat diet.

Supplemental Figure 1. Immunostaining specificity controls.

Supplemental Figure 2. Parallels in aortic and renal post-ischemic inflammatory gene expression.

Supplemental Figure 3. Flow cytometric gating strategies.

Supplemental Figure 4. Flow cytometric gating strategies for assessment of mixed bone marrow chimeras.

Supplemental Figure 5. Renal Ccr2 expression after ischemia reperfusion injury.

Supplemental Figure 6. Histologic outcome in LDLr−/− mice in the absence and presence of myeloid CCR2.

Supplemental Figure 7. Similar histologic outcome after IR in the absence and presence of myeloid CCR2.

References

- 1.Shiao C-C, Wu P-C, Huang T-M, Lai T-S, Yang W-S, Wu C-H, et al. ; National Taiwan University Hospital Study Group on Acute Renal Failure (NSARF) and the Taiwan Consortium for Acute Kidney Injury and Renal Diseases (CAKs) : Long-term remote organ consequences following acute kidney injury. Crit Care 19: 438, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doi K, Rabb H: Impact of acute kidney injury on distant organ function: Recent findings and potential therapeutic targets. Kidney Int 89: 555–564, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Odutayo A, Wong CX, Farkouh M, Altman DG, Hopewell S, Emdin CA, et al. : AKI and long-term risk for cardiovascular events and mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 377–387, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, Garg AX, Parikh CR: Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 961–973, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saratzis A, Harrison S, Barratt J, Sayers RD, Sarafidis PA, Bown MJ: Intervention associated acute kidney injury and long-term cardiovascular outcomes. Am J Nephrol 42: 285–294, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Go AS, Hsu C-Y, Yang J, Tan TC, Zheng S, Ordonez JD, et al. : Acute kidney injury and risk of heart failure and atherosclerotic events. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 833–841, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarnak MJ, Amann K, Bangalore S, Cavalcante JL, Charytan DM, Craig JC, et al. ; Conference Participants : Chronic kidney disease and coronary artery disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 74: 1823–1838, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valdivielso JM, Rodríguez-Puyol D, Pascual J, Barrios C, Bermúdez-López M, Sánchez-Niño MD, et al. : Atherosclerosis in chronic kidney disease: More, less, or just different? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 39: 1938–1966, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wanner C, Amann K, Shoji T: The heart and vascular system in dialysis. Lancet 388: 276–284, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ataklte F, Song RJ, Upadhyay A, Musa Yola I, Vasan RS, Xanthakis V: Association of mildly reduced kidney function with cardiovascular disease: The Framingham Heart Study. J Am Heart Assoc 10: e020301, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu M, Liang Y, Chigurupati S, Lathia JD, Pletnikov M, Sun Z, et al. : Acute kidney injury leads to inflammation and functional changes in the brain. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1360–1370, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujiu K, Shibata M, Nakayama Y, Ogata F, Matsumoto S, Noshita K, et al. : A heart-brain-kidney network controls adaptation to cardiac stress through tissue macrophage activation. Nat Med 23: 611–622, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheel PJ, Liu M, Rabb H: Uremic lung: New insights into a forgotten condition. Kidney Int 74: 849–851, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volkmann J, Schmitz J, Nordlohne J, Dong L, Helmke A, Sen P, et al. : Kidney injury enhances renal G-CSF expression and modulates granulopoiesis and human neutrophil CD177 in vivo. Clin Exp Immunol 199: 97–108, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roy P, Orecchioni M, Ley K: How the immune system shapes atherosclerosis: Roles of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 22: 251–265, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakano T, Ninomiya T, Sumiyoshi S, Onimaru M, Fujii H, Itabe H, et al. : Chronic kidney disease is associated with neovascularization and intraplaque hemorrhage in coronary atherosclerosis in elders: Results from the Hisayama Study. Kidney Int 84: 373–380, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernelot Moens SJ, Verweij SL, van der Valk FM, van Capelleveen JC, Kroon J, Versloot M, et al. : Arterial and cellular inflammation in patients with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 1278–1285, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takx RAP, MacNabb MH, Emami H, Abdelbaky A, Singh P, Lavender ZR, et al. : Increased arterial inflammation in individuals with stage 3 chronic kidney disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 43: 333–339, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ge S, Hertel B, Koltsova EK, Sörensen-Zender I, Kielstein JT, Ley K, et al. : Increased atherosclerotic lesion formation and vascular leukocyte accumulation in renal impairment are mediated by interleukin-17A. Circ Res 113: 965–974, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong L, Nordlohne J, Ge S, Hertel B, Melk A, Rong S, et al. : T Cell CX3CR1 mediates excess atherosclerotic inflammation in renal impairment. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 1753–1764, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nordlohne J, Helmke A, Ge S, Rong S, Chen R, Waisman A, et al. : Aggravated atherosclerosis and vascular inflammation with reduced kidney function depend on interleukin-17 receptor A and are normalized by inhibition of interleukin-17A. JACC Basic Transl Sci 3: 54–66, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiese CB, Zhong J, Xu Z-Q, Zhang Y, Ramirez Solano MA, Zhu W, et al. : Dual inhibition of endothelial miR-92a-3p and miR-489-3p reduces renal injury-associated atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 282: 121–131, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ridker PM, Devalaraja M, Baeres FMM, Engelmann MDM, Hovingh GK, Ivkovic M, et al. ; RESCUE Investigators : IL-6 inhibition with ziltivekimab in patients at high atherosclerotic risk (RESCUE): A double-blind, andomized, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 397: 2060–2069, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ridker PM, MacFadyen JG, Glynn RJ, Koenig W, Libby P, Everett BM, et al. : Inhibition of interleukin-1β by canakinumab and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 71: 2405–2414, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu J, Kumar S, Dolzhenko E, Alvarado GF, Guo J, Lu C, et al. : Molecular characterization of the transition from acute to chronic kidney injury following ischemia/reperfusion. JCI Insight 2: e94716, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi C, Pamer EG: Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 11: 762–774, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gregg LP, Tio MC, Li X, Adams-Huet B, de Lemos JA, Hedayati SS: Association of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 with death and atherosclerotic events in chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol 47: 395–405, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verweij SL, Duivenvoorden R, Stiekema LCA, Nurmohamed NS, van der Valk FM, Versloot M, et al. : CCR2 expression on circulating monocytes is associated with arterial wall inflammation assessed by 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients at risk for cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res 114: 468–475, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bot I, Ortiz Zacarías NV, de Witte WEA, de Vries H, van Santbrink PJ, van der Velden D, et al. : A novel CCR2 antagonist inhibits atherogenesis in apoE deficient mice by achieving high receptor occupancy. Sci Rep 7: 52, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aiello RJ, Perry BD, Bourassa P-A, Robertson A, Weng W, Knight DR, et al. : CCR2 receptor blockade alters blood monocyte subpopulations but does not affect atherosclerotic lesions in apoE(-/-) mice. Atherosclerosis 208: 370–375, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Major TC, Olszewski B, Rosebury-Smith WS: A CCR2/CCR5 antagonist attenuates an increase in angiotensin II-induced CD11b+ monocytes from atherogenic ApoE-/- mice. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 23: 113–120, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tam FWK, Ong ACM: Renal monocyte chemoattractant protein-1: An emerging universal biomarker and therapeutic target for kidney diseases? Nephrol Dial Transplant 35: 198–203, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Furuichi K, Wada T, Iwata Y, Kitagawa K, Kobayashi K, Hashimoto H, et al. : CCR2 signaling contributes to ischemia-reperfusion injury in kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 2503–2515, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu L, Sharkey D, Cantley LG: Tubular GM-CSF promotes late MCP-1/CCR2-mediated fibrosis and inflammation after ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 1825–1840, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rice JC, Spence JS, Yetman DL, Safirstein RL: Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression correlates with monocyte infiltration in the post-ischemic kidney. Ren Fail 24: 703–723, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stroo I, Claessen N, Teske GJD, Butter LM, Florquin S, Leemans JC: Deficiency for the chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 aggravates tubular damage after renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. PloS One 10: e0123203, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sen P, Helmke A, Liao CM, Sörensen-Zender I, Rong S, Bräsen J-H, et al. : SerpinB2 regulates immune response in kidney injury and aging. J Am Soc Nephrol 31: 983–995, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boring L, Gosling J, Cleary M, Charo IF: Decreased lesion formation in CCR2-/- mice reveals a role for chemokines in the initiation of atherosclerosis. Nature 394: 894–897, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bajpai G, Bredemeyer A, Li W, Zaitsev K, Koenig AL, Lokshina I, et al. : Tissue resident CCR2- and CCR2+ cardiac macrophages differentially orchestrate monocyte recruitment and fate specification following myocardial injury. Circ Res 124: 263–278, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mansour SG, Puthumana J, Coca SG, Gentry M, Parikh CR: Biomarkers for the detection of renal fibrosis and prediction of renal outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Nephrol 18: 72, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grayson PC, Eddy S, Taroni JN, Lightfoot YL, Mariani L, Parikh H, et al. : Metabolic pathways and immunometabolism in rare kidney diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 77: 1226–1233, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lefèvre L, Iacovoni JS, Martini H, Bellière J, Maggiorani D, Dutaur M, et al. : Kidney inflammaging is promoted by CCR2+ macrophages and tissue-derived micro-environmental factors. Cell Mol Life Sci 78: 3485–3501, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Imai T, Chantry D, Raport CJ, Wood CL, Nishimura M, Godiska R, et al. : Macrophage-derived chemokine is a functional ligand for the CC chemokine receptor 4. J Biol Chem 273: 1764–1768, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.