Abstract

The Yop virulon allows Yersinia spp. to resist the immune response of the host by injecting harmful proteins into host cells. We identified three new elements of the Yop virulon: SycN, required for normal secretion of YopN, and YscX and YscY, two new components of the secretion machinery.

Pathogenic Yersinia spp. (Y. pestis, Y. pseudotuberculosis, and Y. enterocolitica) share a tropism for lymphoid tissues and the capacity to resist the primary immune response of the host. The apparatus conferring this resistance is called the Yop virulon and is encoded by a 70-kb plasmid called pYV in Y. enterocolitica. The Yop virulon allows extracellular bacteria to inject harmful bacterial proteins straight into the cytosols of the cells of the immune system (for review, see references 11 and 19). The Yop virulon products comprise the Yop proteins, their secretion machinery (called Ysc), and the cytosolic Syc chaperones required for secretion of specific Yops. The Yop proteins can be classified into two groups. The first group includes the effectors (YopE, YopH, YopM, YopO/YpkA, YopP/YopJ, and YopT), which are injected into the cytosol of the target cells and disarm these cells (6, 7, 18, 20, 28, 29, 31, 33, 36, 37), while the second one includes the proteins that form the apparatus allowing the delivery of the effectors into the target cell (YopB, YopD, and LcrV) (for review, see references 11 and 14). The Ysc secretion machinery is encoded by four loci: virC, including yscABCDEFGHIJKLM (2, 25, 27, 41), virG (encoding YscW) (1), virB, including yscNOPQRSTU (3, 5, 21, 44), and virA, including yopN, tyeA, yscV (formerly called lcrD), and lcrR (4, 22, 32, 34, 35). The Syc chaperones are small cytosolic proteins with an acidic isoelectric point and a putative α-helix in the C terminus. They specifically serve one or two Yops, and they are encoded by the gene neighboring the yop gene. Four such chaperones have been identified: SycE for YopE, SycH for YopH, SycD/LcrH for YopD and YopB, and SycT for YopT (20, 30; for review, see reference 43). In addition, it has been shown recently that YscB behaves as a chaperone for YopN: it is specifically required for normal secretion of YopN and it binds to YopN, but unlike the Syc chaperones, it has a basic pI (23). In vitro, Yersinia secretes Yops when they are incubated at 37°C in a medium deprived of Ca2+. Under these conditions, they cease growing. Mutants with mutations in yopN, tyeA, and lcrG are “Ca2+ blind.” This means that, unlike the wild-type strain, they secrete Yops in the presence as well as in the absence of Ca2+, and they cannot grow at 37°C, irrespective of the presence of Ca2+ (8, 16, 22, 38, 39). YopN is a secreted protein (16, 22). TyeA is a 10.8-kDa surface-exposed protein that binds to the second coil-coiled domain of YopN, and it is required for delivery of YopE and YopH (22). LcrG, which binds to heparin sulfate proteoglycans (9), is a nonsecreted bacterial protein required for efficient translocation of all the Yop effectors (38). YopN, LcrG, and TyeA are thus required for the control of Yop release, and they are thought to form a stop valve closing the secretion channel (8, 16, 22, 38, 39). The virA locus contains, between tyeA and yscV (lcrD), three putative open reading frames (ORFs) that have not been characterized yet (16, 21, 22, 42). In this work we analyzed the role of these three genes in the Yersinia Yop virulon. We show that the ORF situated immediately downstream of tyeA encodes SycN, a protein required for normal secretion of YopN, and that the other ORFs encode YscX and YscY, two new proteins of the Ysc secretion machinery.

SycN, a putative chaperone for YopN.

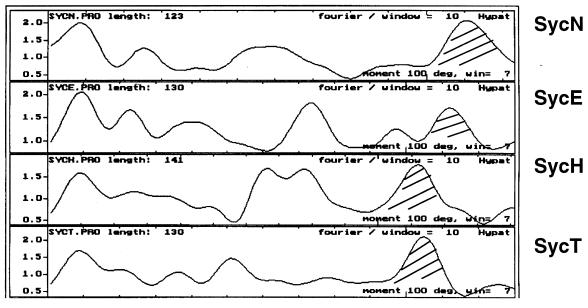

The ORF located immediately downstream from yopN and tyeA (Fig. 1) (previously called ORF2; now called sycN) encodes a putative protein of 123 amino acids (16, 42; also this work). The size of this protein (13.6 kDa), its acidic pI (5.2), and the hydrophobic moment plot (15) evoke those of the chaperones SycE, SycH, and SycT (20; for review see reference 43). As is the case for SycE, SycH, and SycT, the C terminus is predicted to form an amphiphilic α-helix (Fig. 2).

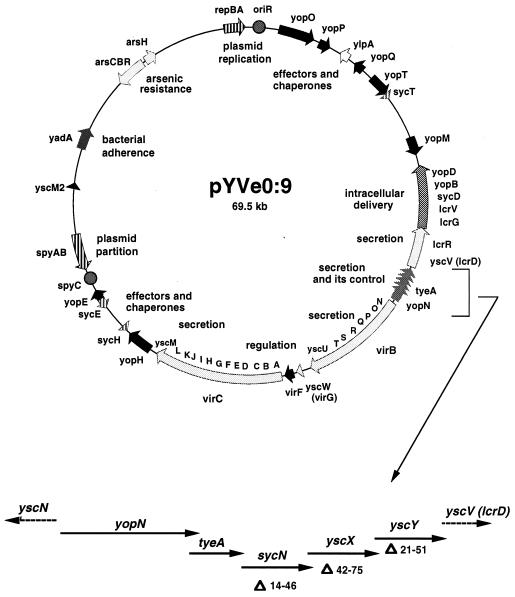

FIG. 1.

Detailed genetic map of the pYV plasmid of Y. enterocolitica W22703. The virA locus is shown in more detail below the map. The codons deleted in each gene are indicated.

FIG. 2.

Similarity between SycN and the other chaperones of the SycE family. Shown are hydrophobic moment plots of SycN, SycE, SycH, and SycT.

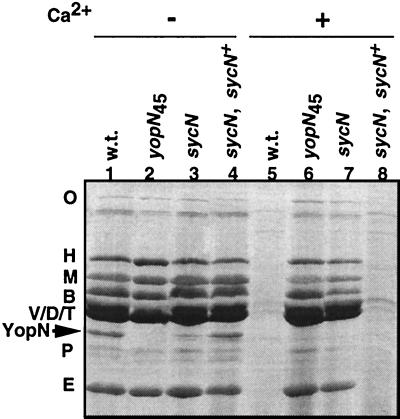

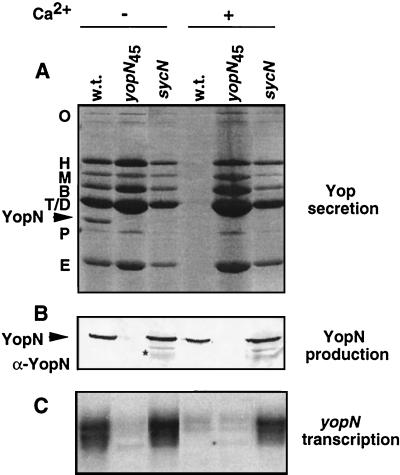

To investigate the role of sycN we constructed a nonpolar mutant by directed mutagenesis (26) with oligonucleotide MIPA 320 (5′-CGCTAACCACAGTGTCTGGCCAAAATGGGA-3′) and plasmid pIM180 carrying sycN as a template. (The plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1.) This primer hybridizes to nucleotides 25 to 39 (with a mismatch at nucleotides 33 and 34 to introduce a BalI site) and to nucleotides 139 to 153 of sycN. The mutated allele sycNΔ14–46 was verified by sequencing, cloned into a suicide vector (24), and introduced into strain E40(pYV40) to obtain strain E40(pIM404). To facilitate the complementation experiments, we also inactivated the chromosomal gene encoding β-lactamase A (10) by inserting the luxAB genes using the mutator plasmid pKNG105 as described by Kaniga et al. (24) to obtain MIE40(pIM404). The sycNΔ14–46 mutant was restricted for growth at 37°C and was Ca2+ blind for Yop secretion. Like the yopN and tyeA mutants it secreted all the Yops in the presence as well as in the absence of Ca2+ (Fig. 3). The amount of YopN secreted was, however, significantly reduced compared to that of the wild type. The mutant could be fully complemented by a plasmid containing the gene cloned downstream from Plac (pIML246) (Fig. 3), indicating that the phenotype observed was due to the lack of sycN and not to an effect on a downstream gene. As shown in Fig. 4, there was no significant difference between the amounts of YopN found in the total cells of the wild-type strain and the sycN mutant, but degradation products appeared in the mutant. Under permissive conditions (minus Ca2+), transcription of yopN in the sycN mutant was similar to that in the wild type. Under nonpermissive conditions (plus Ca2+), transcription of yopN was up-regulated, as expected from the fact that secretion of all the Yops was deregulated (Fig. 4C). sycN was thus necessary for normal secretion of YopN. The deregulated phenotype of the mutant affected in sycN can be explained by the fact that sycN is required for the export of the YopN plug. Together with the physical characteristics of the protein, this suggested that sycN encodes a chaperone specific for YopN. Unfortunately, we could not obtain evidence for direct binding of SycN to YopN, but others mention the existence of this binding in a recent paper (23).

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Genotype or description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pYV derivatives | ||

| pYV40 | Wild-type pYV plasmid from strain E40 | 40 |

| pIM41 | pYV40 yopN45 (encodes a truncated YopN of 45 amino acids) | 8 |

| pIM404 | pYV40 sycNΔ14–46 (pYV40 mutated with pIM212) | This work |

| pIM405 | pYV40 yscXΔ42–75 (pYV40 mutated with pIM211) | This work |

| pIM406 | pYV40 yscYΔ21–51 (pYV40 mutated with pIM209) | This work |

| pIM413 | pYV40 yopN45yscXΔ42–75 | This work |

| pIM414 | pYV40 yopN45yscYΔ21–51 | This work |

| pMSL41 | pYV40 yscNΔ169–177 | 40, 44 |

| Clones | ||

| pIM180 | pIM176Δ1167bpBamHI-BglII (contains 52 codons of yopN, tyeA, sycN, yscX, and yscY) | 22 |

| pIM192 | HindIII deletion of pIM188; pSelect oriTRK2 Plac yscX, yscY | This work |

| pIML236 | pSelect oriTRK2 Plac yscY | This work |

| pIML246 | pBC18R Plac tyeA sycN | This work |

| pSI57 | pTM100 Plac sycH yopH | 41 |

| Suicides and mutators | ||

| pIM150 | pKNG101 + SalI-XbaI fragment of pIM149 (encodes YopN45) | 8 |

| pIM209 | pKNG101 + SalI-XbaI fragment of pIM204 (encodes YscYΔ21–51) | This work |

| pIM211 | pKNG101 + SalI-XbaI fragment of pIM207 (encodes YscXΔ42–75) | This work |

| pIM212 | pKNG101 + SalI-XbaI fragment of pIM202 (encodes SycNΔ14–46) | This work |

| pKNG101 | oriR6KsacBR oriTRK2strAB | 24 |

| pKNG105 | oriR6KsacBR oriTRK2strAB blaA′ luxAB blaA" | 24 |

FIG. 3.

Yop secretion patterns of the wild-type strain (w.t.), the yopN45 mutant, and the ORF2 (sycN) mutant. Lanes 1 and 5, β-lactamase mutant of the wild-type strain [E40(pYV40)] (38); lanes 2 and 6, yopN45 mutant E40(pIM41); lanes 3 and 7, ORF2 (sycN) mutant E40(pIM404); lanes 4 and 8, E40(pIM404)(pIML246 [= Plac sycN]). The strains were grown in brain heart infusion-OX (without Ca2+) or brain heart infusion-Ca2+ (with Ca2+). Culture supernatants were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and stained with Coomassie blue. Letters on the left identify the different Yops.

FIG. 4.

Phenotype of the sycN mutant. (A) Culture supernatants were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and stained with Coomassie blue. Letters on the left identify the different Yops. (B) Western blot analysis of total cell (90 μl of a suspension with an optical density at 600 nm of 1) using a polyclonal antibody against YopN (α-YopN). The asterisk indicates degradation products of YopN. (C) Northern blot analysis carried out on the same culture with a yopN probe (internal PstI fragment of yopN). The strains were grown in brain heart infusion-OX (without Ca2+) or brain heart infusion-Ca2+ (with Ca2+). Lane 1, wild type [E40(pYV40)] (w.t.); lane 2, E40(pIM41); lane 3, E40(pIM404).

A homologue of SycN, called Pcr2, has been identified in the type III secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. SycN and Pcr2 are 67% similar (45). The presence of a homologue in another type III secretion system reinforces our view that SycN has an important role to play in the Yop virulon.

YscX and YscY, two new proteins required for Yop secretion.

ORF3 (which we now rename yscX) (42, also this work), situated immediately downstream from sycN, encodes a protein of 122 amino acids (13.6 kDa) with a calculated isoelectric point of 6.5. The GTG start codon of yscX overlaps with the TGA stop codon of sycN. Immediately downstream from yscX lies yscY (42; also this work), which encodes a protein of 114 amino acids (13.1 kDa) with a calculated isoelectric point of 7.0. The stop codon of yscX overlaps with the start codon of yscY. The function of these genes has not yet been investigated in any Yersinia spp.

We constructed mutants with nonpolar mutations in both genes. The mutation in yscX consisted of an in-frame deletion spanning codons 42 to 75 and was constructed by directed mutagenesis (26) with oligonucleotide MIPA 321 (5′-GTTCGCGCCGATATTCGACTGGATGCCC-3′) and plasmid pIM180 carrying yscX. This primer hybridized to nucleotides 109 to 123 and to nucleotides 226 to 238 of yscX. The mutated allele (yscXΔ42–75) was verified by sequencing, cloned into the suicide vector, and introduced into strain E40(pYV40) to create strain E40(pIM405). The mutation in yscY consisted in an in-frame deletion of codons 21 to 51, and it was constructed with oligonucleotide MIPA 322 (5′-TTAAGTAGCGCGACTTGTAACCAACCGTT-3′) and plasmid pIM180 carrying yscY. This primer hybridized to nucleotides 46 to 60 and to nucleotides 154 to 167 of yscY. The mutant strain carrying yscYΔ21–51 was called E40(pIM406).

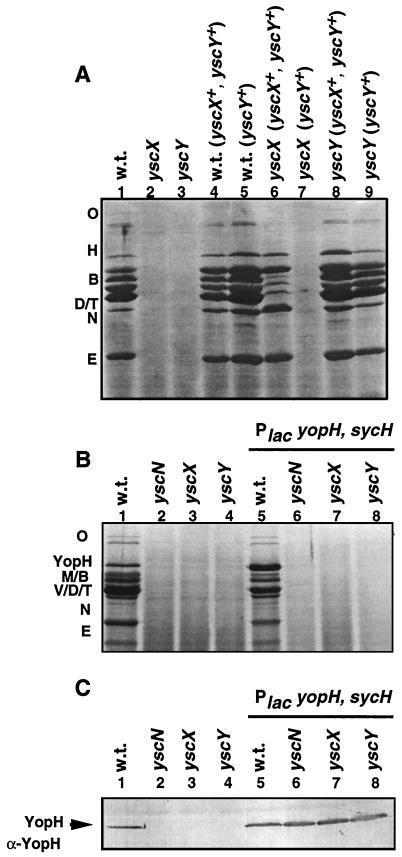

Both mutants were unable to secrete Yops under permissive conditions (Fig. 5A, lanes 2 and 3). Secretion by the yscY mutant was restored after introduction of plasmid pIML236 bearing yscY under the control of the Plac promoter (Fig. 5A, lane 9). To complement the secretion defect of the yscX mutant, we used plasmid pIM192 bearing yscX and yscY and plasmid pIML236 bearing yscY only. As shown in Fig. 5A, plasmid pIM192 restored secretion (lane 6) but plasmid pIML236 did not (lane 7). This indicates that the absence of Yop secretion is due to the lack of either yscX or yscY and not to an effect on the downstream gene yscV (lcrD), which is known to be required for Yop secretion (34, 35).

FIG. 5.

Analysis of the yscX and yscY mutants. (A) Effect on Yop secretion. Shown are results of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of the secreted Yops (Coomassie blue staining). Lane 1, wild type [E40(pYV40)] (w.t.); lane 2, E40(pIM405); lane 3, E40(pIM406); lane 4, E40(pYV40)(pIM192); lane 5, E40(pYV40)(pIML236); lane 6, E40(pIM405)(pIM192); lane 7, E40(pIM405)(pIML236); lane 8, E40(pIM406)(pIM192); lane 9, E40(pIM406) (pIML236). (B) Effect on secretion of overproduced YopH. Shown are results of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of the secreted Yops (Coomassie blue staining). Lane 1, wild type [E40(pYV40)] (w.t.); lane 2, E40(pMSL41); lane 3, E40(pIM405); lane 4, E40(pIM406); lane 5, E40(pYV40)(pSI57); lane 6, E40(pMSL41)(pSI57); lane 7, E40(pIM405)(pSI57); lane 8, E40(pIM406)(pSI57). (C) Analysis of intrabacterial overproduced YopH. Total cells (90 μl of a suspension with an optical density at 600 nm of 1) were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose, and the presence of YopH was detected with a polyclonal antibody against YopH (α-YopH). The lanes are the same as in panel B.

Yop expression is subject to a feedback inhibition of transcription when secretion is compromised (13; for review, see reference 12). To confirm that the lack of Yop proteins in the culture supernatant of the yscX and yscY mutants was due to a defect in Yop secretion and not to a defect in yop transcription, we introduced plasmid pSI57, containing sycH and yopH under the control of the Plac promoter (41), into the yscN (40, 44), yscX, and yscY mutants, and we analyzed the pattern of protein secretion. As shown in Fig. 5B and C, YopH was secreted only by the wild-type strain, although it was present in the total cells of the wild type and the yscN, yscX, and yscY mutants. We concluded from this experiment that YscX and YscY are involved in Yop secretion.

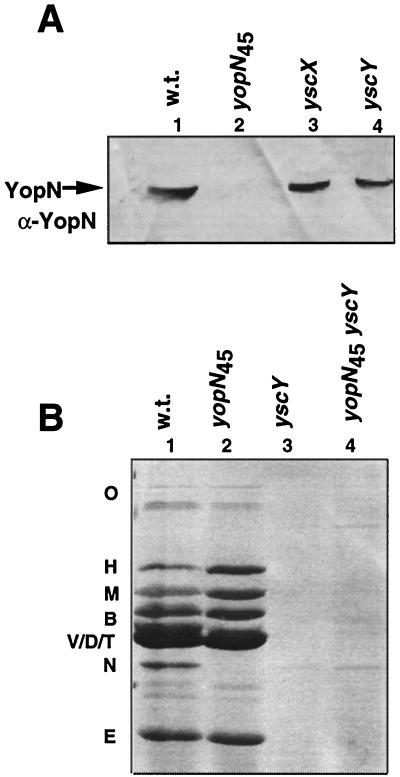

To gain further insight into the function of yscX and yscY, we analyzed the production of YopN by mutants affected in these genes. As seen in Fig. 6A, YopN was present among the intracellular proteins of the mutant bacteria, in agreement with previous results showing that YopN is not subject to the feedback inhibition of transcription that occurs when secretion is compromised (16; for review, see reference 12). Taking into account that yscX and yscY form an operon with yopN and that they are not involved in the production of YopN, we wondered whether their products could be required to remove the stop valve YopN. We constructed a nonpolar yopN45-yscX double mutant [MIE40(pIM413)] and a nonpolar yopN45-yscY double mutant [MIE40(pIM414)]. If the role of YscX and YscY were solely to remove the stop valve YopN, then a double mutant should be able to secrete Yops. However, the double yopN45-yscY and yopN45-yscX mutants did not secrete Yops (Fig. 6B and data not shown), ruling out this hypothesis. In conclusion, these results indicate that the proteins YscX and YscY are part of the secretion machinery, independently of the function of YopN.

FIG. 6.

Role of YscX and YscY in YopN synthesis and operation. (A) Analysis of the intrabacterial YopN. Total cells (90 μl of a suspension with an optical density at 600 nm of 1) were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose, and the presence of YopN was detected with a polyclonal antibody against YopN (α-YopN). Lane 1, wild type [E40(pYV40)] (w.t.); lane 2, E40(pIM41); lane 3, E40(pIM405); lane 4, E40 (pIM406). (B) Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of the Yops secreted. Lane 1, wild type [E40(pYV40)] (w.t.); lane 2, E40(pIM41); lane 3, E40(pIM405); lane 4, E40(pIM414).

Homologues of YscX and YscY have been found in the type III secretion system of P. aeruginosa (45): YscX is 64% similar to Pcr3, and YscY is 61% similar to Pcr4. Surprisingly, YscY is, in addition, 47% similar to the central part of Lpm1, a 1,119-amino-acid surface-located membrane protein of Borrelia burgdorferi (17), an organism not known to form a type III secretion apparatus.

In conclusion, this work allowed us to assign functions to the last genes of the virA locus: one encodes SycN, a putative chaperone for YopN, and the other two encode YscX and YscY, two new proteins of the secretion machinery. If we consider YopN and TyeA, which form the plug (16, 22), to belong to the Ysc apparatus, then the whole virA locus appears to be devoted to the Ysc apparatus, like virB, virC, and virG. In total, this apparatus thus requires 28 genes, with the possible exception of yscH, encoding YopR.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to I. Lambermont and C. Kerbourch for excellent technical assistance and to A. P. Boyd for a critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Belgian “Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique Médicale” (Convention 3.4595.97), the “Direction Générale de la Recherche Scientifique-Communauté Française de Belgique” (Action de Recherche Concertée” 94/99-172), and the “Interuniversity Poles of Attraction Program—Belgian State, Prime Minister’s Office, Federal Office for Scientific, Technical and Cultural Affairs” (PAI 4/03).

REFERENCES

- 1.Allaoui A, Scheen R, Lambert de Rouvroit C L, Cornelis G R. VirG, a Yersinia enterocolitica lipoprotein involved in Ca2+ dependency, is related to ExsB of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4230–4237. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.15.4230-4237.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allaoui A, Schulte R, Cornelis G R. Mutational analysis of the Yersinia enterocolitica virC operon: characterization of yscE, F, G, I, J, K, required for Yop secretion and yscH encoding YopR. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:343–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18020343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allaoui A, Woestyn S, Sluiters C, Cornelis G R. YscU, a Yersinia enterocolitica inner membrane protein involved in Yop secretion. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4534–4542. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4534-4542.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barve S S, Straley S C. lcrR, a low-Ca2+-response locus with dual Ca2+-dependent functions in Yersinia pestis. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4661–4671. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4661-4671.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergman T, Erickson K, Galyov E, Persson C, Wolf-Watz H. The lcrB (yscN/U) gene cluster of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is involved in Yop secretion and shows high homology to the spa gene clusters of Shigella flexneri and Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2619–2626. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.9.2619-2626.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Black D S, Bliska J B. Identification of p130Cas as a substrate of Yersinia YopH (Yop51), a bacterial protein tyrosine phosphatase that translocates into mammalian cells and targets focal adhesions. EMBO J. 1997;16:2730–2744. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boland A, Cornelis G R. Role of YopP in suppression of tumor necrosis factor alpha release by macrophages during Yersinia infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1878–1884. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.1878-1884.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boland A, Sory M P, Iriarte M, Kerbourch C, Wattiau P, Cornelis G R. Status of YopM and YopN in the Yersinia Yop virulon: YopM of Y. enterocolitica is internalized inside the cytosol of PU5-1.8 macrophages by the YopB, D, N delivery apparatus. EMBO J. 1996;15:5191–5201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd A P, Sory M-P, Iriarte M, Cornelis G R. Heparin interferes with translocation of Yop proteins into HeLa cells and binds to LcrG, a regulatory component of the Yersinia Yop apparatus. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:425–436. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornelis G, Abraham E P. β-Lactamases from Yersinia enterocolitica. J Gen Microbiol. 1975;87:273–284. doi: 10.1099/00221287-87-2-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornelis G R, Boland A, Boyd A P, Geuijen C, Iriarte M, Neyt C, Sory M-P, Stainier I. Virulence plasmid of Yersinia, an antihost genome. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1315–1352. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1315-1352.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornelis G R, Iriarte M, Sory M P. Environmental control of virulence functions and signal transduction in Yersinia enterocolitica. In: Rappuoli R, Scarlato V, Arico B, editors. Signal transduction and bacterial virulence. R. G. Austin, Tex: Landes Company; 1995. pp. 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornelis G R, Vanooteghem J C, Sluiters C. Transcription of the yop regulon from Y. enterocolitica requires trans-acting pYV and chromosomal genes. Microb Pathog. 1987;2:367–379. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cornelis G R, Wolf-Watz H. The Yersinia Yop virulon: a bacterial system for subverting eukaryotic cells. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:861–867. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2731623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenberg D. Three-dimensional structure of membrane and surface proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1984;53:595–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.003115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forsberg A, Viitanen A M, Skurnik M, Wolf-Watz H. The surface-located YopN protein is involved in calcium signal transduction in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:977–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraser C M, Casjens S, Huang W M, Sutton G G, Clayton R A, Lathigra R, et al. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–586. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galyov E E, Håkansson S, Forsberg A, Wolf-Watz H. A secreted protein kinase of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is an indispensable virulence determinant. Nature. 1993;361:730–732. doi: 10.1038/361730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hueck C J. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:379–433. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.379-433.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iriarte M, Cornelis G R. YopT, a new Yersinia Yop effector protein, affects the cytoskeleton of host cells. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:915–929. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iriarte, M., and G. R. Cornelis. The 70-kb virulence plasmid of Yersinia. In J. B. Kaper and J. Hacker (ed.), Pathogenicity islands, virulence plasmids, and other mobile virulence elements, in press. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 22.Iriarte M, Sory M P, Boland A, Boyd A P, Mills S D, Lambermont I, Cornelis G R. TyeA, a protein involved in control of Yop release and in translocation of Yersinia Yop effectors. EMBO J. 1998;17:1907–1918. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jackson M W, Day J B, Plano G V. YscB of Yersinia pestis functions as a specific chaperone for YopN. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4912–4921. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.18.4912-4921.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaniga K, Delor I, Cornelis G R. A wide-host-range suicide vector for improving reverse genetics in gram-negative bacteria: inactivation of the blaA gene of Yersinia enterocolitica. Gene. 1991;109:137–141. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90599-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koster M, Bitter W, de Cock H, Allaoui A, Cornelis G R, Tommassen J. The outer membrane component, YscC, of the Yop secretion machinery of Yersinia enterocolitica forms a ring-shaped multimeric complex. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:789–798. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6141981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kunkel T A, Roberts J D, Zakour R A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:367–382. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michiels T, Vanooteghem J C, Lambert de Rouvroit C L, China B, Gustin A, Boudry P, Cornelis G R. Analysis of virC, an operon involved in the secretion of Yop proteins by Yersinia enterocolitica. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4994–5009. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.16.4994-5009.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mills S D, Boland A, Sory M P, Van der Smissen P, Kerbourch C, Finlay B B, Cornelis G R. Yersinia enterocolitica induces apoptosis in macrophages by a process requiring functional type III secretion and translocation mechanisms and involving YopP, presumably acting as an effector protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12638–12643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monack D M, Mecsas J, Ghori N, Falkow S. Yersinia signals macrophages to undergo apoptosis and YopJ is necessary for this cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10385–10390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neyt, C., and G. R. Cornelis. Role of SycD, the chaperone of the Yersinia Yop translocators YopB and YopD. Mol. Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Palmer L E, Hobbie S, Galan J E, Bliska J B. YopJ of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is required for the inhibition of macrophage TNFa production and downregulation of the MAP kinases p38 and JNK. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:953–965. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perry R D, Straley S C, Fetherston J D, Rose D J, Gregor J, Blattner F R. DNA sequencing and analysis of the low-Ca2+-response plasmid pCD1 of Yersinia pestis KIM5. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4611–4623. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4611-4623.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Persson C, Carballeira N, Wolf-Watz H, Fällman M. The PTPase YopH inhibits uptake of Yersinia, tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas and FAK, and the associated accumulation of these proteins in peripheral focal adhesions. EMBO J. 1997;16:2307–2318. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plano G V, Barve S S, Straley S C. LcrD, a membrane-bound regulator of the Yersinia pestis low-calcium response. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7293–7303. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.22.7293-7303.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plano G V, Straley S C. Multiple effects of lcrD mutations in Yersinia pestis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3536–3545. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3536-3545.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosqvist R, Forsberg A, Rimpiläinen M, Bergman T, Wolf-Watz H. The cytotoxic protein YopE of Yersinia obstructs the primary host defence. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:657–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosqvist R, Forsberg A, Wolf-Watz H. Intracellular targeting of the Yersinia YopE cytotoxin in mammalian cells induces actin microfilament disruption. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4562–4569. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4562-4569.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarker M R, Sory M-P, Boyd A P, Iriarte M, Cornelis G R. LcrG is required for efficient translocation of Yersinia Yop effector proteins into eukaryotic cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2976–2979. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2976-2979.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skrzypek E, Straley S C. LcrG, a secreted protein involved in negative regulation of the low-calcium response in Yersinia pestis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3520–3528. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3520-3528.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sory M P, Boland A, Lambermont I, Cornelis G R. Identification of the YopE and YopH domains required for secretion and internalization into the cytosol of macrophages, using the cyaA gene fusion approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11998–12002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.11998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stainier I, Iriarte M, Cornelis G R. YscM1 and YscM2, two Yersinia enterocolitica proteins causing down regulation of yop transcription. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:833–843. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6281995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Viitanen A M, Toivanen P, Skurnik M. The lcrE gene is part of an operon in the lcr region of Yersinia enterocolitica O:3. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3152–3162. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3152-3162.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wattiau P, Woestyn S, Cornelis G R. Customized secretion chaperones in pathogenic bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:255–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Woestyn S, Allaoui A, Wattiau P, Cornelis G R. YscN, the putative energizer of the Yersinia Yop secretion machinery. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1561–1569. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1561-1569.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yahr T L, Mende-Mueller L M, Friese M B, Frank D W. Identification of type III secreted products of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S regulon. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7165–7168. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7165-7168.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]