Abstract

Life expectancy figures for countries and population segments are increasingly being reported to more decimal places and used as indicators of the strengths or failings of countries’ health and social systems. Reports seldom quantify their intrinsic statistical imprecision or the age-specific numbers of deaths that determine them.

The SE formulas available to compute imprecision are all model based. This note adds a more intuitive data-based SE method and extends the jackknife to the analysis of event rates more generally. It also describes the relationships between the magnitude of the SE and the numbers of person-years and deaths on which it is based. These relationships can help quantify the statistical noise present in published year-to-year differences in life expectancies, as well as in same-year differences between or within countries.

Agencies and investigators are encouraged to use one of these SEs to report the imprecision of life expectancy numbers and to tailor the number of decimal places accordingly. (Am J Public Health. 2022;112(8):1151–1160. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.306805)

Some counties have begun to report national sex-specific life expectancy (LE) at birth to 2 decimal places, whereas international organizations use at most 1. Two authors1 have recently taken issue with the absence of margins of error in these reports and with the false precision conveyed by these undue numbers of decimal places. On the basis of several models that allowed them to relate accuracy (they used the width of a 95% confidence interval) to population sizes and mortality levels, they concluded that “even if death registration and population counts were perfect, the accuracy of LE would not reach a year for 30% of all countries, 0.1 years for 63% of all countries, and 0.01 years for any country, even China or India.”

Methods to calculate a statistical margin of error for an LE have been available for 80 years and have been described in demography textbooks.2 Thus, it is surprising that national LE figures are seldom accompanied by a measure (or appreciation) of the intrinsic statistical (im)precision of such figures or a mention of the age-specific numbers of deaths that determine them. A few national statistical agencies, such as Statistics Canada,3 publish margins of error for their LEs and document how they were calculated. British agencies make reference to ways to compute them4 but do not publish them. US agencies do so when presenting LEs based on decennial life tables5,6 but not for other life tables.

One possible explanation for not reporting margins of error might be that there is no “sampling” involved.5 In this thinking, the LE derived from the mortality rates for the population or subpopulation of a certain city or country in 2018 is no different than the heating degree days for a city or the average birthweight for those born during 2018. Although this perspective is understandable, it does not communicate how fragile or stable the LE number is (i.e., how much higher or lower it might have been if the number of deaths was one more or one fewer or the year was determined with the Gregorian or fiscal calendar). Because of this fragility, the reported LE for a single calendar year in the Statistics Iceland Web site is “the mean of that year and the year before.”

Admittedly, the 3 available SE formulas of Wilson,7 Chiang,8 and Silcocks et al.,9 from 1938, 1960, and 2001, respectively, are model-based formulas derived from calculus and are not very intuitive or easy to explain, even to those who are comfortable with simple SEs involving a unit variance, a “sample size,” and a square root. Thus, here I introduce a new and more intuitive SE method. It retains the attempt by the earliest developer to give an intuition behind—and the insights provided by the components of—the SE formula but avoids the differential calculus. Also, using several sex-specific, calendar year–specific, and country-specific data sets, I report the empirical relationships between the magnitude of the SE and the numbers of person-years and deaths on which it is based.

The SE helps quantify how much statistical noise is present in published year-to-year differences in LEs, as well as in same-year differences between countries. It thus highlights how many decimal places, if any, are meaningful, even when there are no other sources of error. The empirical relationships can also be used to project the approximate magnitude of the SE to be computed from a smaller, not yet examined data set.

I proceed by first reviewing how life tables are calculated, indicating where the statistical uncertainties come from, and explaining how the 3 existing model-based formulas convert these age bin–specific uncertainties into SEs for the LEs derived from the fitted life table. I then show how the jackknife method provides a simple and intuitive way to appreciate how statistically fragile or stable the fitted LE is and which deaths influence it the most. I end by examining the empirical relationships between the magnitude of the SE and the numbers of person-years and deaths on which it is based.

FROM OBSERVED MORTALITY RATES TO LIFE EXPECTANCIES

The observed data (the “inputs”) used to show the basic LE calculations are given in the first 2 columns of Table 1. The first contains the reported age-specific numbers of deaths (Ds) of Canadian females in 105 1-year age bins in the year 2011. The corresponding amounts of population time (PT; here measured in units of woman-years but more generally person-years [PY]) in each of these bins were calculated as the reported numbers of women in these age bins in mid-2011 multiplied by the width (1 year) of each age bin.

TABLE 1—

Data, Derived Life Expectancies, and SE[e0] Calculations

| (0)a | (1)b | (2)c | (3)d | (4)e | (5)f | (6)g | (7)h | (8)i | (9)j |

| a | D | PY | m | q | l | L | e | ||

| 0 | 790 | 183 826 | 4.3 | 0.0043 | 1.0000 | 0.9979 | 83.555 | 0.000452 | 0.000161 |

| 1 | 43 | 185 297 | 0.232 | 0.0002 | 0.9957 | 0.9956 | 82.913 | 0.000443 | 0.000008 |

| 2 | 25 | 186 394 | 0.134 | 0.0001 | 0.9955 | 0.9954 | 81.932 | 0.000435 | 0.000005 |

| 3 | 23 | 184 328 | 0.125 | 0.0001 | 0.9953 | 0.9953 | 80.943 | 0.000434 | 0.000004 |

| 4 | 17 | 180 064 | 0.0944 | 0.0001 | 0.9952 | 0.9952 | 79.953 | 0.000439 | 0.000003 |

| 14 | 27 | 201 104 | 0.134 | 0.0001 | 0.9944 | 0.9943 | 70.018 | 0.000344 | 0.000003 |

| 24 | 74 | 229 764 | 0.322 | 0.0003 | 0.9919 | 0.9917 | 60.179 | 0.000258 | 0.000005 |

| 34 | 124 | 228 521 | 0.543 | 0.0005 | 0.9883 | 0.9880 | 50.379 | 0.000216 | 0.000006 |

| 44 | 278 | 244 580 | 1.14 | 0.0011 | 0.9815 | 0.9810 | 40.687 | 0.000161 | 0.000007 |

| 54 | 778 | 254 182 | 3.06 | 0.0031 | 0.9634 | 0.9620 | 31.341 | 0.000117 | 0.000011 |

| 64 | 1 390 | 189 386 | 7.34 | 0.0073 | 0.9218 | 0.9184 | 22.505 | 0.000107 | 0.000016 |

| 74 | 2 034 | 110 355 | 18.4 | 0.0183 | 0.8226 | 0.8150 | 14.538 | 0.000105 | 0.000022 |

| 84 | 4 101 | 71 652 | 57.2 | 0.0556 | 0.5970 | 0.5802 | 7.884 | 0.000062 | 0.000016 |

| 94 | 2 896 | 14 206 | 204 | 0.1844 | 0.1919 | 0.1736 | 3.595 | 0.000042 | 0.000005 |

| 99 | 996 | 2 810 | 354 | 0.2984 | 0.0528 | 0.0445 | 2.298 | 0.000035 | 0.000001 |

| 100 | 736 | 1 870 | 394 | 0.3254 | 0.0371 | 0.0306 | 2.076 | 0.000032 | 0.000001 |

| 101 | 480 | 1 126 | 426 | 0.3471 | 0.0250 | 0.0204 | 1.851 | 0.000031 | 0.000000 |

| 102 | 327 | 728 | 449 | 0.3618 | 0.0163 | 0.0132 | 1.589 | 0.000026 | 0.000000 |

| 103 | 225 | 424 | 531 | 0.4118 | 0.0104 | 0.0081 | 1.227 | 0.000020 | 0.000000 |

| 104 | 129 | 232 | 556 | 0.4265 | 0.0061 | 0.0047 | 0.767 | 0.000009 | 0.000000 |

| Sum | 120 883 | 17.2 million | 83.5554 | 0.001091 |

Note. SE(e0) based on Eqn. 1, with:

Wilson8: 0.

Chiang7: .

Silcocks9: .

Jackknife SE(e0) .

Source. Data were obtained from the Human Mortality Database.10

(0): the beginning age of each 1-year wide interval; only 20/105 intervals shown

(1): Observed no. of deaths in interval

(2): No. of person years in interval, estimated as (midyear population) × (1 y)

(3): observed mortality rate, D / PY

(4):

(5):

(6):

(7):

(8):

(9):

The focus here is on LEs to the age of 105 years to avoid noise from small observed numbers of deaths at ages beyond this age. Three derived columns of numbers must be calculated to arrive at these LEs. The first is the column of observed (or, if they are unstable, smoothed) death rates, derived in the usual way as m = D/PY. From this, one derives the column (q) of (here 1-year) conditional probabilities of dying within the age interval in question. These probabilities refer to a hypothetical cohort. Formerly, when the exponential function was not easily accessible, the column entries were computed arithmetically as explicit fractions, but it now makes more sense to use the exponential formula linking rates and risks, namely = 1 − exp[−m × 1 year]. The “hats” on the qs are used to emphasize that they are based on empirical ms and thus are as reliable or as fragile as these ms.

Next is the column, the also hypothetical “proportions still alive” (“living”) at the beginning of each interval. Just as in medical life tables, these proportions are computed as the products of successive conditional “survival” probabilities; for example, at the second birthday of the fictional cohort (i.e., at a = 2), the surviving fraction is = (1 − 1) × (1 − 2). As with medical life tables, it helps if the “radix” is taken to be 0 = 1 rather than, for instance, 0 = 10 000.

The third is the column, the numbers of person-years lived in the various intervals by this “cohort.” Traditionally, calculations involve a hypothetical (numbers of deaths) column formed by successive subtractions of s and the portions of the interval those who would have died are assumed to have lived. Here a more direct way is used that inverts the relationship m = q/L to obtain = /m (or 1 full year if, whenever D is zero, m is also zero). The sum of all of the s represents e0, the hypothetical LE at birth. The other e entries—those for subsequent birthdays—are obtained by dividing the partial sums of the s by the corresponding s. In what follows, the birthday subscript is omitted.

THREE MODEL-BASED SE[e] FORMULAS

Perhaps because of his several articles and textbooks devoted to the life table, the SE method of Chiang7 is much better known than a very similar one introduced earlier by Wilson.8 Surprisingly, neither of these methods are mentioned in the article9 that introduces the Silcocks version. As shown subsequently, all 3 methods have a common structure and differ only in how they address the sampling variability of the qs. Because Wilson provided the most comprehensive and most comprehensible justification for his derivation, and because his heuristic approach ties in with the approach introduced in the next section, my description begins with his version and is limited to the SE for the estimate of e0. In Wilson’s words, this e0 is

deduced by a mathematical calculation from the age specific death rates; by definition it is the average number of years lived after birth by a birth cohort of 0 persons, i.e., 0 × e0 is the total number of years lived by the birth cohort.8(p705)

Instead of using the brevity afforded by calculus, he continues as follows8(p705):

Now, if in some particular age interval y to y + 1, the value of qy, the chance of dying between those ages, should perchance be decreased by δqy, the number of deaths would be decreased by y × δqy and the years lived would be increased in that age interval by (1/2)×y × δqy and in all ages above y +1 by y ×ey+1 × δqy. Thus the expectation of life e0 would be changed by

To a first order of approximation, regarding δq as infinitesimal, the total change in e0 from variations δq in different age groups would be the sum of the individual changes, where the summation extends over all intervals, from birth on to the end of the life table. As the variations δq are supposed to be those of random sampling they must be assumed to be uncorrelated and the square of the standard deviation of e0 is therefore

(1)

As is shown in the notes of Table 1, each of the 3 calculus-derived versions of the SE formula incorporates a different expression for each Var[y]. Wilson treated the number of person-years as numbers of persons and considered the random variable m as having the binomial-form variance Var[m] = m(1 − m)/PY. Because he derived q from m using the traditional formula , he multiplied Var[m] by the scaling factor (f′).2 For ease of computing, he expressed this factor in terms of q and m, that is, as . Chiang, instead, treated as a binomial proportion based on an “unknown” number of persons, N, and thus as having variance q(1 − q)/N. He back-calculated the N as = D/q to arrive at Var() = q(1 − q)/ = q2(1 − q)/D.

Silcocks et al. used different notation than the demographers do: L, A, r, and N rather than l, L, D, and PT, respectively. He used the more modern exponential form to derive from m but calculated L via the trapezium rule rather than as /m. Because he considered the ms as the random components in equation 1, he calculated each variance component as a Poisson-based variance, that is, as D/PT2. As one can see, the 3 calculated SEs in the worked example are quite close to each other. The reason for the slightly larger Silcocks SE is that he used the (slightly larger) Poisson, rather than binomial, variance components.

A MORE TRANSPARENT STANDARD ERROR CALCULATION

Of the 3 authors, Wilson provided the least technical and most readable description of the calculus-based derivation of the variance of a complicated nonlinear function of (in the present example) 105 random Ds in the 105 amounts of population time. Moreover, his verbal explanation, starting with the sentence containing the word “perchance,” can be seen as a specific example of a related but simpler and empirical (rather than model-based) variance-calculation approach.11 It was formalized 2 decades later12 and named the “jackknife.” The appendix (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) provides a worked example of the jackknife SE for the mean of a sample of 5 values and a Poisson count and illustrates the versatility that led John Tukey to name the “leave-one-out” approach the jackknife.

To apply the jackknife to the current life table in Table 1, one might (for the sake of using “rounder” numbers) consider the 17.2 million person-years of data as 150 trillion person-intervals, each just under 1 hour in duration. Some 120 883 of these person-intervals involve a death. (Of course, these time units are arbitrary.) Then, imagine a particular interval “perchance” omitted and a new LE calculated, along with the quantity ΔLE and how much it differs from the LE based on all n units. Imagine repeating this process for each for the n person-intervals in turn. Despite the very large n, all but 120 883 of the ΔLEs are zero. The 120 883 nonzero differences take on the 105 values shown in column 8 with the frequencies shown in column 1. Thus, the jackknife variance, namely the sum of the squares of the 150 trillion ΔLEs, reduces to the sum given at the foot of column 9. The jackknife gives just about the same SE as the existing calculus-derived methods, another example of the versatility and transparency of this tool.

Over the more than 600 LEs calculated from the sex-specific, calendar year–specific, and country-specific data considered in the next section, the jackknife SEs were from 1.008 to 1.016 times the Wilson SEs, from 1.003 to 1.009 times the Chiang SEs, and from 0.97 and 0.98 times the Silcocks SEs.

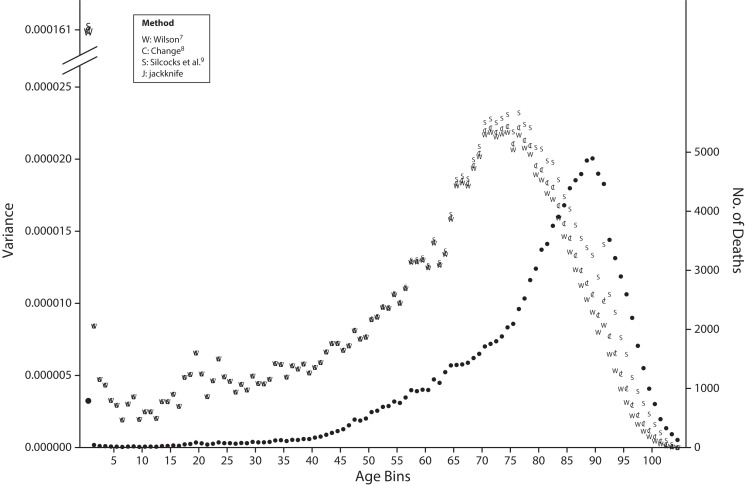

Figure 1 shows the age-specific contributions to the variance of the LE. The results from the 3 existing (calculus-derived) methods show a high level of agreement. This is not surprising given that the formulas differ only in the distributional assumptions they incorporate for the rightmost term in equation 1: the differences become visible only from the age of 70 years onward, when q and m and the associated binomial and Poisson variances begin to diverge, but even then they remain small and inconsequential. The jackknife method is purely data driven and calculates contributions without any assumptions beyond those used in calculating the LE itself.

FIGURE 1—

Age Bin–Specific Contributions to the Overall Variance in Life Expectancy, for Each Method Separately: Canada, 2011

Note. Data are for females. The numbers of deaths per age bin (right vertical axis) are shown as black dots. Source. Human Mortality Database.

With greater clarity than equation 1, Figure 1 also highlights which age bins contribute most to the variance of the LE. Not surprisingly, the 790 deaths in the first year of life contribute 15% of the variance, although they represent fewer than 1% of all deaths. The 43 in the second year, the 778 in the 55th year, and the 4895 in the 90th year contribute approximately 1% each. The largest contribution to the variance, 2%, is made by the 2034 deaths in the 75th year.

SE[e0] MAGNITUDES AND THEIR DETERMINANTS

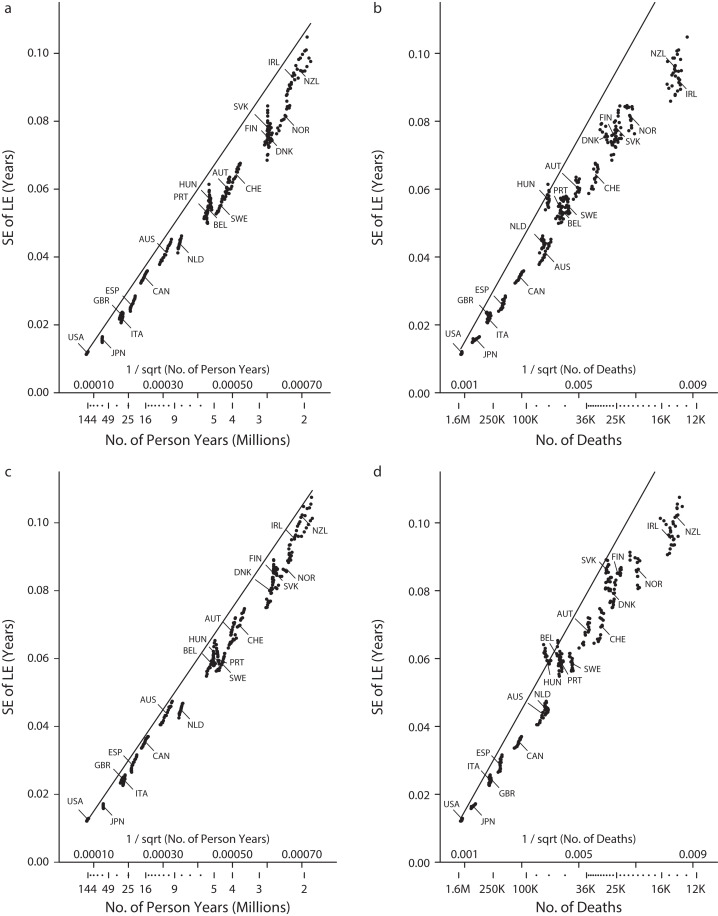

The SE[e0]s shown in Figure 2 are from more than 600 actual data sets: 20 countries in the Human Mortality Database, each with up to 16 individual calendar years, for females and males separately. Even if we were to be less stringent and multiply each one by just 2 (rather than by 4 as Li and Tuljapurkar1 did), none of the resulting “margins of error” would be less than 0.02 years.

FIGURE 2—

How SE[e0] for Life Expectancy (LE) at Birth Varies With (a and c) the Numbers of Person-Years and (b and d) the Numbers of Deaths on Which the LE Calculation Is Based for (a and b) Females and (c and d) Males, Respectively: 20 Countries, 2000–2015

Note. Each dot is calculated from the data in single-year-of-age age bins for a single calendar year for 1 country. The lines, with slopes of 150 and 15, respectively, are intended as rough upper bounds. Source. Human Mortality Database.

Because the Human Mortality Database does not include them, other data sources13–15 were used for SE calculations for females in India and China. The year 2010 was chosen, near the middle of the calendar period in Figure 1. Numbers of deaths were back-calculated through the use of reported 2010 age-specific mortality rates in the case of India and Canadian mortality rates scaled up so as to match the overall death rate in the case of China. The SEs for these Indian and Chinese e0s were 0.006 and 0.008 years, so even the “margins of error” (0.012 and 0.016, respectively) were both greater than the resolution of 0.01 years that many smaller countries use to report LEs.

One might also be concerned with the magnitudes of sex-specific SEs based on data from a single calendar year in a country or population segment with a small population. As a means of studying a range of small data sets, Human Mortality Database information was obtained for 2 countries with populations of fewer than 1 million people: Iceland, whose total population ranged from approximately 320 000 to 340 000 over the period 2000 to 2015, and Luxembourg, whose population ranged from approximately 430 000 to 560 000 over the same period.

The SE[e0]s for these countries and calendar years are plotted on the left side of Figure 3. The SEs in different colors further to the right of these SE[e0]s were obtained from reduced versions of these data sets ranging from 1/2 to 1/10th of the actual experience. As a means of forming these reduced data sets, the actual sex-, year-, and age bin–specific person-years were multiplied by 1/2, 1/3, . . . 1/10th, whereas the corresponding numbers of deaths were sampled from the observed counts with probabilities 1/2, 1/3, . . . 1/10th, respectively.

FIGURE 3—

How SE[e0] for Life Expectancy (LE) at Birth Varies With (a and c) the Numbers of Person-Years and (b and d) Numbers of Deaths on Which the LE Calculation Is Based, for (a and b) Females and (c and d) Males, Respectively: Iceland and Luxembourg, 2000–2015

Note. Each dot is calculated from the sex-specific data in single-year-of-age age bins for a single calendar year for 1 country (Iceland or Luxembourg, leftmost 2 sets) or a “country segment” (further to right) that ranges from 1/2 to 1/10th the size of Iceland or Luxembourg. Source. Human Mortality Database.

Although there are some anomalies, the broad patterns in Figures 2 and 3 bear out Li and Tuljapurkar’s statement that the SE is roughly inversely proportional to the square root of the reciprocal of each total. One can go a bit further, quantifying the “constants” (slopes) and thus providing a rough empirical rule of thumb by which to gauge the likely magnitude of an SE using either the total number of person-years or the total number of deaths on which the e0 is based. Instead of going “through” the datapoints, the following equations provide lines that in most instances go “somewhat above” the data points from these 20 countries, 2 genders, and 15 or more calendar years:

| (2) |

The magnitudes of the SEs in the leftmost panels of Figure 3 are broadly in line with the patterns seen in Eayres and Williams’s Table 2.16 The standard deviation in Silcocks and colleagues’ Figure 2,9 with 256 000 person-years, is 0.27 years, whereas equation 2 gives an upper bound of 150/square root(256000) = 0.3 years. Across the simulated experiences of 5000 person-years in Eayres and Williams’s Figure 3, the standard deviation was 2 years, whereas the “bound” from equation 2 is 150/square root(5000) = 2.1 years.

CONCLUSIONS

The first objective of this article was to illustrate a versatile tool that provides a more intuitive SE for the LE calculated from a current life table. It provides very similar answers to the existing methods, all of which were derived through differential calculus but are seldom used, even for life tables published by national and international statistical agencies. It also makes fewer assumptions as to the sampling distributions of the numbers of events in each age bin and avoids the confusion about binomial versus Poisson when calculating the variance components in the 3 calculus-based methods. Of course, although it may appear that the jackknife approach does not make distributional assumptions, there is an implicit assumption that the population time is divisible into a very large number of very small independent time elements.

The binomial-based Wilson and Chiang formulas treated the denominator inputs to the empirical age-specific mortality rates (the random vector ms, the fundamental column from which the life table is constructed) as numbers of persons. But deaths occur in (arise from) population time, the amount of which is typically estimated by multiplying the width of the calendar time period by the (estimated) midperiod population size.

This “person-years, not persons” principle comes to the fore when deciding how to apply the jackknife to the inputs to life tables: what is the correct choice of the “unit” of data, that is, what is the “n” in the summation and in the (n − 1)/n in the jackknife variance formula? Unlike a count of persons, population time is infinitely divisible. This divisibility principle is what enables the jackknife approach to yield the same variance as the model-based (Poisson) variance in the (1 age bin) example 2 in the appendix: the PT in the age bin is regarded as a very large number (n) of small time units, some D of which contain 1 death each. Moreover, in the jackknife approach, age bins that contain no deaths do not contribute to the variance in accord with recent findings.13

The second objective was to give a broad sense of how the magnitude of the SE for LE at birth varies with the amount of information in the input data set and of how many (if any) decimal places are meaningful. Not all that surprisingly, and as other authors have found, the SE broadly obeys the “reciprocal of the square root” law, both in the amounts of population time and in the numbers of deaths. This report quantifies the constant in this relationship and offers a rough upper bound for the relationship that should apply to data from populations or population segments with age structures similar to those shown in Figures 1 and 2.

If one works with amounts of population time rather than population sizes, data from multiple calendar years enter into the SE calculations in the same way as single-calendar-year data. Naturally, LEs based on k years of data have SEs that are square root(k) times smaller than those based on a single year of data and also guard against wild fluctuations caused by factors such as influenza activity. The (formerly more common) practice of centering multiyear LE calculations on the census year also reduces the effect of inaccuracies in intercensal population estimates on LEs for individual years.

There is increasing interest17–19 in using the LE as a summary measure for small area mortality levels, and investigators who derive such a summary measure seem quite aware of its imprecision. The relationships shown in Figure 2, which can be seen as extending those in Eayres and Williams’s Table 2,16 should be of help. Although I have used single year-of-age bins throughout, the jackknife SE calculations I have shown will—with the usual modifications—work with bins of any width, and the relationships between the various SEs and the overall numbers of deaths and PT should remain similar. Indeed, one can think of broader bins as a form of smoothing. Fitting, say, a Gompertz or a spline model to Ds and PTs is another way to deal with sparse counts in the early and late ages and also allows the possibility of using the variance covariance matrix for the parameters to obtain a resampling confidence interval via the parametric bootstrap.

The extensive sets of SEs in Figures 2 and 3 reinforce the remarks of earlier authors about the overly precise LEs being reported by national statistical agencies. Because many national LEs are the same (“tied”) when rounded to an integer or to 1 decimal place, LE “league table” rankings based on mortality rates in a single year should not be taken too seriously.

I end with general remarks on the shape of the sampling distribution of the LE statistic. Some authors were surprised at how Gaussian it is, even when based on seemingly small samples. This Gaussian-ness is a reflection of the central limit theorem, which applies also to nonlinear functions of independently (but not necessarily identically) distributed random variables. Just as in the case of Kaplan–Meier and model-based survival estimates, the applicability of the central limit theorem to fitted LEs is governed by the total number of events as opposed to the number in any one age or time bin.

Those who still do not trust in the central limit theorem will not be comfortable computing symmetric confidence intervals based on 1 of the 3 existing SEs or the jackknife SE and would prefer a bootstrap CI. But how to bootstrap an LE? The infinite divisibility principle discussed earlier suggests a way. In the case of the data in Table 1, bootstrap the n = 150 billion person-hours that, between them, contain the 120 883 events; then calculate an LE from each bootstrap sample and do this enough times to obtain a sufficiently smooth sampling distribution from which to estimate the required, say, 2.5% and 97.5% percentiles.

If one thinks through what this process involves, one will realize that the same estimated sampling distribution can be obtained by treating each D as the expected value, μ, of a Poisson random variable; using a random draw from each of these Poisson distributions; calculating a bootstrap LE using the actual amounts of PT and the randomly sampled numbers of deaths, and repeating the preceding steps enough times to have a sufficiently smooth estimated sampling distribution from which to measure the required percentiles. When one applies this procedure to the Ds and PTs in Table 1, one finds that the estimated sampling distribution of the bootstrapped LEs is quite Gaussian, and the standard deviation is 0.033 years, just as it was with the methods considered earlier.

When I bootstrapped the various versions of the Iceland data (samples of females in the year 2000), the LE sampling distributions were still quite Gaussian, even when the sample contained just 100 deaths. This and earlier investigations suggest that bootstrap confidence intervals are not needed and, if they were, that the considerable imprecision would render the results uninformative. Thus, an SE based on 1 of the 3 existing methods—or on the jackknife—can be used to form symmetric confidence intervals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

I thank the referees for their helpful comments and advice.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author reports no conflicts of interest.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No protocol approval was needed for this study because no human participants were involved.

REFERENCES

- 1.Li N, Tuljapurkar S.2019. https://paa2012.princeton.edu/papers/120176

- 2.Kitner HJ. The life table. In: Siegel JS, Swanson DA, editors. The Methods and Materials of Demography. 2nd ed. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier; 2004. pp. 301–340. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Statistics Canada. 2019. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/84-538-x/84-538-x2019001-eng.htm

- 4.Toson B, Baker A.2019. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/241469911_Life_expectancy_at_birth_methodological_options_for_small_populations

- 5.Arias E, Curtin LR, Wei R, Anderson RN. US decennial life tables for 1999. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2008;57(1):1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Center for Health Statistics. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/mortality/lewk4.htm

- 7.Wilson EB. The standard deviation of sampling for life expectancy. J Am Stat Assoc. 1938;33(204):705–708. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1938.10502348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiang C. A stochastic study of the life table and its applications: II. Sample variance of the observed expectation of life and other biometric functions. Hum Biol. 1938;32:221–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silcocks PBS, Jenner DA, Reza R. Life expectancy as a summary of mortality in a population: statistical considerations and suitability for use by health authorities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;32(1):38–43. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.University of California, Berkeley, and Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research. 2019. http://www.mortality. Org

- 11.Quenouille MH. Notes on bias in estimation. Biometrika. 1956;43(3–4):353–360. doi: 10.1093/biomet/43.3-4.353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tukey JW. Bias and confidence in not quite large samples. Ann Math Stat. 1958;29:614. [Google Scholar]

- 13.PopulationPyramid. 2019. https://www.populationpyramid.net/china/2017

- 14.Open Government Data Platform. 2019. https://data.gov.in/catalog/estimated-age-specific-death-rates-sex

- 15.PopulationPyramid. 2019. https://www.populationpyramid.net/india/2010

- 16.Eayres D, Williams ES. Evaluation of methodologies for small area life expectancy estimation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(118):243–249. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.009654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jonker MF, van Lenthe FJ, Congdon PD, Donkers B, Burdorf A, Mackenbach JP. Comparison of Bayesian random-effects and traditional life expectancy estimations in small-area applications. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(10):929–937. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Talbot TO, Done DH, Babcock GD. Calculating census tract-based life expectancy in New York State: a generalizable approach. Popul Health Metr. 2018;16(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12963-018-0159-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boothe VL, Fierro LA, Laurent A, Shih M. sub-county life expectancy: a tool to improve community health and advance health equity. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:E11. doi: 10.5888/pcd15.170187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]