Abstract

In June 2020, Massachusetts implemented a first in the nation statewide law that restricts sales of menthol and other flavored tobacco. Since implementation, sales data indicate high retailer compliance. Drastic decreases were seen in sales of all flavored tobacco. Most neighboring states did not see increases in overall tobacco sales, although New Hampshire saw an initial increase in menthol sales, which was not sustained. We found that menthol restrictions are effective and that federal-level legislation is important, as some cross-border sales highlight. (Am J Public Health. 2022;112(8):1147–1150. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.306879)

In 2009, federal law banned the sales of all flavored cigarettes except menthol. The exclusion of menthol perpetuated existing inequities in tobacco marketing, tobacco use, and health outcomes among groups historically targeted by the tobacco industry (including Black, LGBTQ [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/-sexual, queer or questioning], and female populations, as well as youths).1–3 This ban also led to an increase in availability and youths’ use of non–cigarette-flavored tobacco products.4 In 2019, youths’ tobacco use in Massachusetts reached its highest rate in more than 20 years (Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, 2019).

INTERVENTION AND IMPLEMENTATION

In response to the increasing availability of flavored tobacco, in 2014, local municipalities in Massachusetts began to pass restrictions on its sale. However, these restrictions excluded menthol. In November 2019, resulting in part from local momentum, advocacy coalitions, and youth and community engagement efforts, Massachusetts passed An Act Modernizing Tobacco Control (https://www.mass.gov/guides/2019-tobacco-control-law), a first in the nation statewide law that restricts the sales of all flavored tobacco (including menthol) to adult-only smoking bars (for onsite consumption only). This law also includes an excise tax on vape products.

To help ensure compliance, Massachusetts used its rigorous enforcement infrastructure to provide communications (i.e., mailings and media promotion) and educational visits to retailers before and after implementation. Retail scanner data were used to provide timely surveillance data for monitoring compliance and evaluating policy impact.

PLACE, TIME, AND PERSONS

The new law took full effect June 2020. The availability of menthol and other flavored tobacco was reduced from more than 6000 outlets to fewer than 30.

Before the law, 12% of Massachusetts adults smoked cigarettes, and of those an estimated 37%, or 216 611, smoked menthol cigarettes (63% identified as people of color; Massachusetts Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2019). Furthermore, the tobacco industry targeted flavored products at the 847 000 youths (aged 10–19 years) who live in Massachusetts (American Community Survey, 2019). As a result, 37% of Massachusetts high school students reported current (past 30-day) use of any tobacco product (i.e., cigarettes, cigars or cigarillos, smokeless tobacco, vape products) in 2019 (Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, 2019).

PURPOSE

The law took a step toward improving racial and health equity and protecting youths and young adults from industry targeting. Previous research demonstrated that policies that restrict flavored tobacco are effective at reducing the sales and availability of flavored tobacco in the retail environment and at reducing adult and youth tobacco use.5–8

EVALUATION AND ADVERSE EFFECTS

The Massachusetts Tobacco Cessation and Prevention program obtained tobacco product UPC (Universal Product Code) scanner data from the Nielsen Company. We obtained data from three years before the law was implemented to one year after (June 2017–June 2021) in five state-specific markets: Massachusetts and the neighboring states of New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont. For each state, we aggregated unit sales of four categories of tobacco (i.e., cigarettes, cigars or cigarillos, smokeless tobacco, and vape products) and stratified them by flavor category (i.e., menthol, other flavor, and unflavored).

We standardized data in accordance with existing methods. One pack of cigarettes, one large cigar, two cigarillos, 20 little cigars, one disposable or rechargeable e-cigarette, one e-cigarette refill or kit, one three-ounce container of chewing tobacco, one 1.2–ounce container of dip or snuff, or one container of snus equaled one unit.9,10

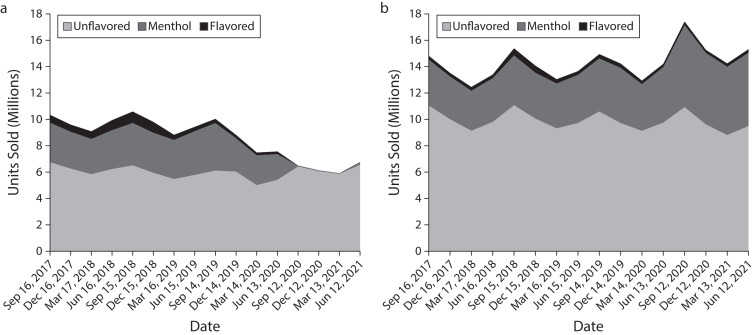

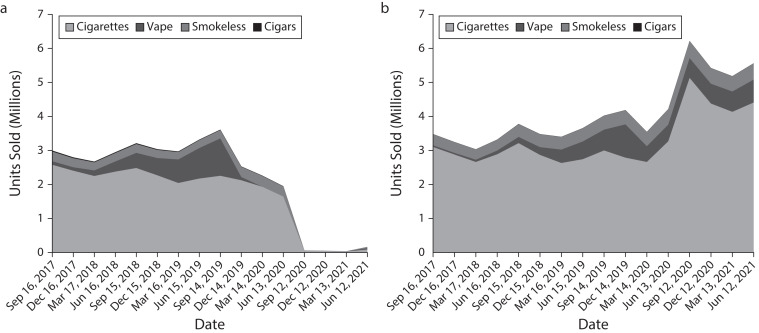

Results suggest that the law was effective in reducing flavored product sales in Massachusetts. In the year after implementation (June 13, 2020–June 12, 2021), overall tobacco sales in Massachusetts decreased from 33 917 494 to 25 315 189 (25.4%) units compared with the previous year (June 2019–June 2020; Figure 1). Sales of unflavored products increased from 22 609 326 to 24 947 827 (10.3%) units, menthol products decreased from 10 355 518 to 317 863 (96.9%) units, and sales of other flavored products decreased from 952 650 to 49 499 (94.8%) units compared with the previous year. Trends in Massachusetts across the study period were driven largely by cigarettes, as they make up 77% of total tobacco sales in the state, followed by cigars (12%), vape products (7%), and smokeless tobacco (4%; Figure 2).

FIGURE 1—

Tobacco Sales by Flavor Type for (a) Massachusetts and (b) New Hampshire: 2017–2021

FIGURE 2—

Menthol Tobacco Sales by Product Type for (a) Massachusetts and (b) New Hampshire: 2017–2021

We examined sales data from bordering states to assess whether an unintended consequence of the law was Massachusetts residents traveling out of state to purchase tobacco. Altogether, total sales in New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont decreased by 1.8% in the year after implementation compared with the previous year (from 106 863 560 to 104 937 096 units). Individually, total sales decreased in New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont (from 31 952 666 to 24 896 472 [22.1%] in NY; from 12 345 375 to 11 840 564 [4.1%] in RI; and from 6 234 704 to 5 937 620 [4.8%] in VT). In these states, most changes in sales of menthol and other flavors were also decreases. However, small increases occurred in Vermont and Rhode Island: menthol sales increased from 1 582 520 to 1 595 765 (0.8%) units in Vermont, and other flavored sales increased from 427 341 to 479 624 (12.2%) units in Rhode Island (Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

In New Hampshire, tobacco sales increased in the year after implementation compared with the previous year, but only by 5 931 624 (10.5%) units. Sales of unflavored products decreased 338 498 (0.9%) units, sales of menthol products increased 6 417 808 (40.2%) units, and sales of other flavored products decreased 147 686 (13.1%) units during this period (Figure 1). Although overall tobacco sales initially increased 22.6% in the three months after law implementation (compared with three months before law implementation), menthol sales then decreased in the following six months (September 2020–March 2021). Furthermore, when comparing changes in menthol sales in New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the year after implementation, we saw a net decrease in menthol sales.

Some limitations exist. We did not include Connecticut, another state bordering Massachusetts. Nielsen captures only large chain retailers and convenience stores (e.g., big box supermarkets, drug stores, and dollar stores), so only a quarter of retailers in Massachusetts are represented. In addition, sales data are a proxy for availability and use; an increase in New Hampshire sales does not necessarily indicate a widespread increase in menthol cigarette availability or sustained or increased rates of menthol cigarette use among Massachusetts residents. Finally, any increases seen in tobacco sales may have been driven in part by increased adult substance use during COVID-19 (data not shown). Massachusetts will continue to monitor trends in sales as well as additional data directly capturing tobacco access and use behaviors to assess how the new law affects Massachusetts tobacco users in the longer term.

SUSTAINABILITY

We saw that, with rigorous outreach and enforcement, retailer compliance with the law in Massachusetts was high and that other states did not have substantial increases in tobacco sales. We saw a marginal increase in Massachusetts’ menthol sales from April through June 2021. We will continue to monitor sales data to assess whether compliance continues in the longer term. In New Hampshire, although we saw an initial increase in the proportion of menthol tobacco sales three months after the law was implemented, seasonal trends in sales may partially account for this increase, and we will monitor data over time to assess whether sales return to the rates before the law was implemented. Preliminary data from July through September 2021 suggest that menthol sales in New Hampshire are trending downward. Furthermore, historical New Hampshire cigarette stamp data indicate an initial increase in cigarettes stamped immediately after Massachusetts increased its cigarette sales tax in 2013, but this increase was not sustained (New Hampshire Department of Revenue).

In geographically smaller states like Massachusetts, many tobacco users can drive across state lines, for example, into New Hampshire and Rhode Island, to obtain products.6 The price of a pack of menthol cigarettes in New Hampshire is on average $2.39 to $4.23 cheaper than in Massachusetts and surrounding states (NY, RI, VT).11 Therefore, removing these products from the market entirely would maximize the public health benefit of flavored tobacco restriction policies. This study demonstrates the importance of federal legislation.

PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE

Reducing the availability of flavored tobacco may lead to decreased tobacco use and smoking-attributable mortality. Researchers estimate that from 1980 to 2018, menthol cigarettes were responsible for 10.1 million additional smokers, 3 million life-years lost, and 378 000 premature deaths.12 In addition, these policies may help protect youths from a lifetime of nicotine addiction; recent research provides promising evidence that flavored tobacco restrictions can curb youths’ tobacco use.5,6 Furthermore, given industry targeting of menthol to people of color, policies that reduce the availability of menthol products may have a direct impact on reducing racial inequities in smoking-attributable mortality.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Massachusetts Tobacco Cessation and Prevention program’s policy technical assistance providers for their review of this article: D. J. Wilson, Cheryl Sbarra, Sarah McColgan, and Chris Banthin.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No protocol approval was necessary because no human participants were involved in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Villanti AC, Mowery PD, Delnevo CD, Niaura RS, Abrams DB, Giovino GA. Changes in the prevalence and correlates of menthol cigarette use in the USA, 2004–2014. Tob Control. 2016;25(suppl 2):ii14–ii20. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson SJ. Marketing of menthol cigarettes and consumer perceptions: a review of tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2011;20(suppl_2):ii20–ii28. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.041939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fallin A, Goodin AJ, King BA. Menthol cigarette smoking among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adults. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(1):93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Courtemanche CJ, Palmer MK, Pesko MF. Influence of the flavored cigarette ban on adolescent tobacco use. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(5):e139–e146. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kingsley M, Setodji CM, Pane JD, et al. Short-term impact of a flavored tobacco restriction: changes in youth tobacco use in a Massachusetts community. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6):741–748. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kingsley M, Setodji CM, Pane JD, et al. Longer-term impact of the flavored tobacco restriction in two Massachusetts communities: a mixed-methods study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(11):1928–1935. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntab115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung-Hall J, Fong GT, Meng G, et al. Evaluating the impact of menthol cigarette bans on cessation and smoking behaviours in Canada: longitudinal findings from the Canadian arm of the 2016–2018 ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Surveys. Tob Control. 2021 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asare S, Majmundar A, Westmaas JL, et al. Association of cigarette sales with comprehensive menthol flavor ban in Massachusetts. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(2):231–234. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.7333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuiper NM, Gammon D, Loomis B, et al. Trends in Sales of flavored and menthol tobacco products in the United States during 2011–2015. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(6):698–706. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loomis BR, Rogers T, King BA, et al. National and state-specific sales and prices for electronic cigarettes—U.S., 2012–2013. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(1):18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boonn A; Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. State excise and sales taxes per pack of cigarettes: total amounts & state rankings. 2021. https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/factsheets/0202.pdf

- 12.Le TT, Mendez D. An estimation of the harm of menthol cigarettes in the United States from 1980 to 2018. Tob Control. 2021 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]