Abstract

Background

Cystic fibrosis is a genetic disorder in which abnormal mucus in the lungs is associated with susceptibility to persistent infection. Pulmonary exacerbations are when symptoms of infection become more severe. Antibiotics are an essential part of treatment for exacerbations and inhaled antibiotics may be used alone or in conjunction with oral antibiotics for milder exacerbations or with intravenous antibiotics for more severe infections. Inhaled antibiotics do not cause the same adverse effects as intravenous antibiotics and may prove an alternative in people with poor access to their veins. This is an update of a previously published review.

Objectives

To determine if treatment of pulmonary exacerbations with inhaled antibiotics in people with cystic fibrosis improves their quality of life, reduces time off school or work, and improves their long‐term lung function.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis Group's Cystic Fibrosis Trials Register. Date of the last search: 7 March 2022.

We also searched ClinicalTrials.gov, the Australia and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry and WHO ICTRP for relevant trials. Date of last search: 3 May 2022.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials in people with cystic fibrosis with a pulmonary exacerbation in whom treatment with inhaled antibiotics was compared to placebo, standard treatment or another inhaled antibiotic for between one and four weeks.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected eligible trials, assessed the risk of bias in each trial and extracted data. They assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE criteria. Authors of the included trials were contacted for more information.

Main results

Five trials with 183 participants are included in the review. Two trials (77 participants) compared inhaled antibiotics alone to intravenous antibiotics alone and three trials (106 participants) compared a combination of inhaled and intravenous antibiotics to intravenous antibiotics alone. Trials were heterogenous in design and two were only available in abstract form. Risk of bias was difficult to assess in most trials but, for four out of five trials, we judged there to be a high risk from lack of blinding and an unclear risk with regards to randomisation. Results were not fully reported and only limited data were available for analysis. One trial was a cross‐over design and we only included data from the first intervention arm.

Inhaled antibiotics alone versus intravenous antibiotics alone

Only one trial (18 participants) reported a perceived improvement in lifestyle (quality of life) in both groups (very low‐certainty evidence). Neither trial reported on time off work or school. Both trials measured lung function, but there was no difference reported between treatment groups (very low‐certainty evidence). With regards to our secondary outcomes, one trial (18 participants) reported no difference in the need for additional antibiotics and the second trial (59 participants) reported on the time to next exacerbation. In neither case was a difference between treatments identified (both very low‐certainty evidence). The single trial (18 participants) measuring adverse events and sputum microbiology did not observe any in either treatment group for either outcome (very low‐certainty evidence).

Inhaled antibiotics plus intravenous antibiotics versus intravenous antibiotics alone

Inhaled antibiotics plus intravenous antibiotics may make little or no difference to quality of life compared to intravenous antibiotics alone. None of the trials reported time off work or school. All three trials measured lung function, but found no difference between groups in forced expiratory volume in one second (two trials; 44 participants; very low‐certainty evidence) or vital capacity (one trial; 62 participants). None of the trials reported on the need for additional antibiotics. Inhaled plus intravenous antibiotics may make little difference to the time to next exacerbation; however, one trial (28 participants) reported on hospital admissions and found no difference between groups. There is likely no difference between groups in adverse events (very low‐certainty evidence) and one trial (62 participants) reported no difference in the emergence of antibiotic‐resistant organisms (very low‐certainty evidence).

Authors' conclusions

We identified only low‐ or very low‐certainty evidence to judge the effectiveness of inhaled antibiotics for the treatment of pulmonary exacerbations in people with cystic fibrosis. The included trials were not sufficiently powered to achieve their goals. Hence, we are unable to demonstrate whether one treatment was superior to the other or not. Further research is needed to establish whether inhaled tobramycin may be used as an alternative to intravenous tobramycin for some pulmonary exacerbations.

Keywords: Humans; Administration, Inhalation; Anti-Bacterial Agents; Anti-Bacterial Agents/administration & dosage; Anti-Bacterial Agents/therapeutic use; Cystic Fibrosis; Cystic Fibrosis/complications; Cystic Fibrosis/drug therapy; Lung; Quality of Life; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Tobramycin; Tobramycin/administration & dosage; Tobramycin/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Inhaling antibiotics to treat temporary worsening of lung infection in people with cystic fibrosis

Review question

What evidence is there for using inhaled antibiotics to treat exacerbations (flare ups) of lung infection in people with cystic fibrosis?

Background

Cystic fibrosis is a serious genetic disorder that results in abnormally sticky mucus in several parts of the body. In the lungs this sticky mucus can lead to repeated infections. An exacerbation makes the symptoms of infection more severe. Antibiotics are an essential part of treatment and may be given by mouth (orally), by needle into the blood stream (intravenously) or by inhaling the drug. We wanted to learn if inhaling antibiotics improved general health compared to the other methods. This might mean that people with cystic fibrosis could avoid hospitalisation for intravenous antibiotics and some side effects of intravenous treatment. Inhaling the antibiotics would also be easier for people who have difficulty with access to their veins. This is an updated version of the review.

Search date

We last looked for evidence on 7 March 2022.

Study characteristics

We found five trials comparing different ways of giving antibiotics when treating exacerbations in a total of 183 people with cystic fibrosis. Two trials compared inhaled antibiotics alone to intravenous antibiotics alone (77 participants) and three trials compared a combination of inhaled and intravenous antibiotics to intravenous antibiotics alone (106 participants). In all trials, the inhaled antibiotics were compared to the same antibiotics given intravenously. The numbers of participants in each trial ranged from 16 to 62.

Key results

Inhaled antibiotics alone versus intravenous antibiotics alone

One trial (18 participants) reported a perceived improvement in lifestyle in both groups, but neither trial reported on time off work or school. Both trials measured lung function, but neither reported any difference between treatment groups. One trial (18 participants) reported no difference in the need for additional antibiotics and the second trial (59 participants) reported on the length of time until the next exacerbation ‐ there was no difference between inhaled or intravenous antibiotics for either outcome. Only one trial (18 participants) measured adverse events and sputum microbiology, but did not find any difference between treatments for either outcome.

Inhaled antibiotics plus intravenous antibiotics versus intravenous antibiotics alone

One trial found that there is likely no difference in quality of life between treatments. All of the trials reported lung function, but found no difference between groups. One trial showed there to be little or no difference in the time until the next exacerbation. None of the trials reported on the need for additional antibiotics; however, one trial (28 participants) found no difference in the number of hospital admissions between groups. There may be no difference between groups in adverse events and one trial (62 participants) reported no difference in the appearance of antibiotic‐resistant organisms.

Certainty of the evidence

We graded the certainty of the evidence as very low or low. We had concerns since only one trial stated how the participants were diagnosed with CF or how they defined an exacerbation. It was not possible to keep secret which treatment the participants were receiving, as the trials compared different ways of giving the antibiotics; we thought this would likely influence some of the results. We were not sure whether the participants were put into the different groups truly at random and we do not know how this might have affected the results.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings: Inhaled antibiotics compared with IV antibiotics.

| Inhaled antibiotics compared with IV antibiotics for pulmonary exacerbations in CF | ||||||

|

Patient or population: children and adults with CF and an acute exacerbation Settings: inpatient in hospital Intervention: inhaled antibiotics Comparison: IV antibiotics | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (trials) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| IV antibiotics | Inhaled antibiotics | |||||

|

Quality of life perceived change in lifestyle after treatment Follow‐up: 4 weeks |

There was a perceived improvement in lifestyle after treatment in both groups. | 18 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝

very lowa,b |

No data provided. | ||

| Time off work or school | This outcome was not reported. | |||||

|

Lung function change in FEV1 after treatment Follow‐up: 4 weeks after completion of therapy |

There was improvement in FEV1 after treatment in both groups, but this was not significant. | 18 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b | Not enough data to enter into analysis. A further 3‐arm trial also measured lung function but the specific measurements were not described; there was no difference reported in treatment with twice‐daily IV ceftazidine or once‐daily inhaled ceftazidine, but both of these treatments were better than 3 times daily IV ceftazidine. |

||

|

Need for additional IV or oral antibiotics Follow‐up: 4 weeks after completion of therapy |

No events were seen in the control group. |

RR 6.11 (0.33 to 111.71) |

18 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b | Very few data reported | |

|

Time to next pulmonary exacerbation Follow‐up: 4 weeks after completion of therapy |

The time to the next exacerbation was longest in the once‐daily inhaled antibiotic group, less in the twice‐daily IV antibiotic group, but both longer than in the group receiving IV antibiotics three‐times‐daily. | 59 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝

very lowa,b |

Very few data reported | ||

|

Adverse events Follow‐up: 4 weeks after completion of therapy |

No adverse events were observed in either group. | 18 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b | |||

|

Microbiology Emergence of resistant organisms Follow‐up: not stated |

No results reported for this outcome | 59 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b | No results reported. This outcome was stated to be measured in the Shatunov trial, but no results were reported (Shatunov 2001). |

||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CF: cystic fibrosis; CI: confidence interval; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; IV: intravenous; RR: risk ratio; IV: intravenous. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a Downgraded twice for unclear or high risk of bias within the trial

b Downgraded once due to imprecision ‐ very low participant numbers

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings: Inhaled antibiotics plus IV antibiotics compared with IV antibiotics only.

| Inhaled plus IV antibiotics compared with IV antibiotics only for pulmonary exacerbation in CF | ||||||

|

Patient or population: children and adults with pulmonary exacerbation in CF Settings: inpatient in hospital Intervention: inhaled antibiotics plus IV antibiotics Comparison: IV antibiotics | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (trials) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| IV antibiotics alone | IV + inhaled antibiotics | |||||

|

Quality of life: number of participants achieving MCID Follow‐up: 14 days |

625 per 1000 | 750 per 1000 (381 to 1000) | RR 1.2 (0.61 to 2.34) | 16 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b |

The results presented here are for first‐arm data only. Results presented in the paper used data from both intervention periods and showed that MCID was achieved more frequently with AZLI + IV (10/12 participants, 83.3%) compared to IV + IV (7/16 participants, 43.8%) P = 0.04 (Frost 2018). |

| Time off work or school | This outcome was not reported. | |||||

|

Lung function: change in FEV1 % predicted from baseline Follow‐up: end of treatment (discharge from hospital which ranged from 14 days to 26 days |

No difference was found between groups in change in FEV1 % predicted after treatment. | 44 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝

very lowb,c |

1 of the trials included in this outcome had a cross‐over design and we have only reported first‐arm data. Results from both treatment periods reported in the paper showed that after 14 days of treatment AZLI + IV was associated with greater lung function improvement than IV + IV, MD 4.6% (95% CI 2.1 to 7.2) (P = 0.002). Investigators reported that this result was robust regardless of baseline lung function (Frost 2018). | ||

| Need for additional IV or oral antibiotics | This outcome was not reported. | |||||

| Time to next pulmonary exacerbation | There was no difference in time to next exacerbation between groups (log rank P = 0.51). |

16 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b |

When the full dataset was reported by the trial authors, no difference was seen in time to next exacerbation between groups (Frost 2018). | ||

|

Adverse events moderate adverse events experienced during and after treatment Follow‐up: 4‐6 weeks after the end of treatment (2 weeks) |

No reports of renal toxicity in either group. Serum creatinine levels remained at less than 1.0 mg/dL and did not increase by more than 0.5 mg/dL in any participant; no proteinuria or cylinduria observed in either group. | 28 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowb,c | No data were available for analysis. A further study reported this outcome but did not state which group the adverse events occurred in and therefore provided no evidence. The cross‐over study reported adverse events for the whole trial period and so has not been included in our analysis. The authors reported that adverse events occurred at similar frequencies for both treatments (Frost 2018). |

||

|

Microbiology Emergence of resistant organisms Follow‐up: 1 to 2 weeks |

83 per 1000 | 187 per 1000 (22 to 1000) | RR 2.25 (0.27 to 19.04) | 28 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowb,c | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). AZLI: aztreonam lysine; CF: cystic fibrosis; CI: confidence interval; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; IV: intravenous; MCID: minimum clinically important difference; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a Downgraded once due to risk of bias due to trial design. The trial was a cross‐over design and we have only been able to include first‐arm data. The open‐label design and therefore knowledge of treatment arm may have had an effect on this outcome.

b Downgraded once due to imprecision caused by small sample size and small numbers of participants.

c Downgraded twice due to high or unclear risk of bias across several domains for this outcome. One trial had an unclear risk of bias from randomisation and allocation concealment and both were at high risk from lack of blinding. There was also possible selective reporting of some outcomes.

Background

Description of the condition

Pulmonary manifestations of cystic fibrosis (CF) are characterised by abnormal airway secretions associated with infection and inflammation leading to bronchiectasis. In almost all people with CF, there is an inevitable progression in the severity of lung disease resulting in more severe airway damage, progressive airflow obstruction and premature death due to respiratory failure (Gibson 2003a).

It is well‐recognised that there are periodic increases in the severity of lung disease, which are referred to as pulmonary exacerbations (Elborn 2007). Exacerbations are one of the most important clinical events in the course of the disease for people with CF because of the increased symptoms, the acceleration in the rate of decline in lung function, and the need for increased treatment (De Boer 2011; Sanders 2010; Sanders 2011). Severe exacerbations have been associated with CF‐related diabetes (Marshall 2005), sleep disturbances (Dobbin 2005) and may lead to reduced survival (De Boer 2011). Multiple factors play a role in the pathogenesis of pulmonary exacerbations, such as respiratory microbiome, host defences and environmental exposures (Goss 2007).

Defining pulmonary exacerbations in CF is challenging due to the variability and the subjective nature of presenting symptoms. A combination of symptoms, physical signs and laboratory findings have been used to help with diagnosis and grade severity (Gibson 2003a); the major criteria for diagnosing a pulmonary exacerbation are changes in an individual's symptoms (Goss 2007). The Fuchs criteria (Fuchs 1994) have been used in many clinical trials to define an exacerbation (Bilton 2011). The definition relies on treatment with intravenous antibiotics for four of the following respiratory signs or symptoms: new or increased haemoptysis; a change in sputum; increased cough; increased dyspnoea; fever above 38°C; fatigue; malaise; weight loss; sinus pain or pressure; change in sinus drainage; change in lung auscultation; a drop in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) of at least 10% from baseline; or new radiographic findings to identify an exacerbation state (Fuchs 1994). However, no consensus diagnostic criteria exist (BMJ 2018).

Description of the intervention

Antibacterial drugs are an essential treatment for pulmonary exacerbations. The selection of antibiotic treatment will depend on the organism(s) usually found in respiratory secretions, as well as the precipitating factor or identification of a new infection, or both. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the usual organism, particularly in adults (Smyth 2006), although methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has recently emerged as an important pathogen in people with CF, with a 10‐fold increase in prevalence between 1996 and 2014 (Jennings 2017).

Most inhaled antibiotics are delivered as an aerosol, generated from a nebuliser. Administration takes between 5 and 20 minutes, generally twice each day; the shorter delivery times reflect relatively recent developments in nebuliser technology. The nebulisers which are used to administer the antibiotics are relatively expensive and require training of the patient or caregiver to use them correctly. There are dry powder devices becoming available which should be more convenient than nebulisers. The type of nebulisers used to administer drugs in CF is the subject of a further Cochrane Review (Daniels 2013).

How the intervention might work

Treatment of exacerbations using antibiotics with activity against P aeruginosa reduces symptoms and improves lung function (Gold 1987; Wientzen 1980). A Cochrane Review of nebulised anti‐pseudomonal antibiotics for maintenance treatment of individuals with CF and P aeruginosa infection has shown them to be associated with an improvement in lung function and a reduction in the frequency of exacerbations requiring additional antibiotic treatment (Smith 2018b). In people with stable disease, inhaled antibiotics have been shown to reduce concentrations of P aeruginosa in sputum and to increase FEV1 two weeks after onset of treatment suggesting their usefulness for treating exacerbations (Ramsey 1993).

Why it is important to do this review

In practice, inhaled antibiotics are almost certainly used to treat pulmonary exacerbations. The global frequency of such use is not known, but an article published by the Epidemiologic Study of Cystic Fibrosis (ESCF) from the USA and Canada reported that 24% of pulmonary exacerbations were treated with inhaled antibiotics (Wagener 2013). While their use has been further noted in earlier papers (Moskowitz 2008; Smyth 2008) and four articles reviewing treatment of pulmonary exacerbations mention the use of inhaled antibiotics (Flume 2009; Gibson 2003a; Smyth 2006; Smyth 2008), there are no firm recommendations and no evidence is cited. The use of inhaled antibiotics for P aeruginosa was recommended in the recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance in conjunction with intravenous (IV) antibiotics in individuals experiencing new P aeruginosa infection to facilitate eradication; however, there is no strong evidence to support this recommendation (NICE 2017).

New inhaled antibiotics are being developed, as are devices for administering them, and these will probably increase inhaled antibiotic use for treating pulmonary exacerbations.

The use of inhaled antibiotics to treat pulmonary exacerbations has advantages compared to IV administration. Inhaled antibiotics can augment oral therapy for milder exacerbations and avoid hospitalisation and IV access. Furthermore, inhaled aminoglycosides can reduce the risk of kidney damage and loss of hearing that is associated with IV aminoglycosides. Finally, inhaled antibiotics could provide another treatment option to IV antibiotics for those individuals with difficult venous access.

Hence, there is a need to establish whether there is evidence of an effect of inhaled antibiotics for treating pulmonary exacerbations in CF. This is an update of a previously published review (Smith 2018a).

Objectives

To determine if treatment of pulmonary exacerbations with inhaled antibiotics in people with CF improves their quality of life, reduces time off school or work, and improves their long‐term lung function.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

Children and adults with CF who are diagnosed with having a pulmonary exacerbation. Diagnosis of CF to be made using clinical criteria and confirmed by sweat testing or genetic analysis. A pulmonary exacerbation was taken as defined by the individual trial protocol.

Types of interventions

We considered any inhaled antibiotic, at any dose, using any method of aerosol delivery. Duration of treatment was between one and four weeks. The inhaled antibiotic was administered alone or in addition to the usual treatment for pulmonary exacerbations and compared to either placebo or other antibiotic treatment.

Types of outcome measures

We assessed the following outcome measures.

Primary outcomes

QoL (as measured by a validated tool such as Cystic Fibrosis Quality of Life (CFQoL) (Gee 2000) or Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire ‐ Revised (CFQ‐R) (Quittner 2009))

Time off work or school

-

Lung function (spirometry)

FEV1 (litres or per cent (%) predicted) absolute values or change values

forced vital capacity (FVC) (litres or % predicted) absolute values or change values

Annual change in FEV1

Secondary outcomes

Need for hospital admission (in the short term (up to four weeks))

-

Need for additional antibiotics

IV

oral

Time to next pulmonary exacerbation

Weight (kg)

-

Adverse effects

mild ‐ resulting in no change in treatment (e.g. cough, bronchospasm)

moderate ‐ resulting in change in treatment (e.g. loss of hearing, nephrotoxicity)

severe ‐ needs hospital admission or is life‐threatening (e.g. anaphylactic reactions, nephrotoxicity)

-

Microbiology

emergence of new organisms

emergence of resistant organisms

Search methods for identification of studies

There were no restrictions regarding language or publication status.

Electronic searches

We identified relevant trials from the Group's Cystic Fibrosis Trials Register using the terms: antibiotics AND (acute treatment OR unknown) AND (inhaled OR not stated).

The Cystic Fibrosis Trials Register is compiled from electronic searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (updated each new issue of The Cochrane Library), weekly searches of MEDLINE, a search of Embase to 1995 and the prospective handsearching of two journals ‐ Pediatric Pulmonology and the Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. Unpublished work is identified by searching the abstract books of three major cystic fibrosis conferences: the International Cystic Fibrosis Conference; the European Cystic Fibrosis Conference and the North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference. For full details of all searching activities for the register, please see the relevant sections of the Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group's website.

Date of latest search of CF Trials Register: 7 March 2022.

We also searched for ongoing trials on 3 May 2022 using the strategies described in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

Reference Lists

We checked the bibliographies of included trials and any relevant systematic reviews identified for further references to relevant trials.

Correspondence

We contacted the first author of the cross‐over trial to ask if data from the first treatment period were available (3 August 2021). The author (Dr Freddy Frost) was able to provide these data, which we have included in the review.

Data collection and analysis

For any of the methods stated below, which we have not been able to undertake in this version of the review, we plan to do so if data become available for a future update.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently screened titles and abstracts of the citations retrieved from the searches (SS and NR). The same two authors read the full‐text articles identified from the title and abstract screening to select trials that met the inclusion criteria (for earlier versions of the review: EC, SS, NR, NJ and TR; for this update: SS and NR). Where there was disagreement between the authors on the trials selected, we attempted to reach a decision by consensus or by involving the third author to arbitrate (EC). The current author team did not re‐assess the judgements for trials previously listed in the review.

Data extraction and management

Two authors recorded details of trial design, participant characteristics, interventions, quality assessment, and the relevant outcome data using a customised data extraction form (for previous versions of the review: NJ, EC and TR; for this update: SS and NR). We settled any disagreement by consensus. We have reported the following characteristics in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table where data were available from the papers:

criteria for diagnosis of CF;

definition of pulmonary exacerbation;

type of infection;

trial design;

inhaled antibiotic and dose;

aerosol delivery method;

duration of treatment;

comparison intervention;

other treatments (e.g. IV or oral antibiotics and setting (inpatient or outpatient)); and

severity of exacerbation using baseline FEV1 (% predicted).

We have presented separate comparisons for inhaled antibiotics alone versus IV antibiotics and for combination inhaled and IV antibiotics versus IV antibiotics alone. As planned, we have reported outcomes at up to one week, between one and two weeks, more than two weeks to three weeks, more than three weeks to four weeks. We have also considered additional follow‐up data recorded at other time periods.

Lung function is generally recognised as an indicator of morbidity and mortality, so, if in future we obtain data for annual change in FEV1, we will report this as a surrogate marker for long‐term survival.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (for previous versions of the review: NJ, EC and TR; for this update: SS and NR) assessed the risk of bias of the selected trials using the domain‐based evaluation as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017). We assessed the following domains as having either a low, unclear, or high risk of bias:

randomisation (low risk ‐ random number table, computer‐generated lists or similar methods; unclear risk ‐ described as randomised, but no details given; high risk ‐ e.g. alternation, the use of case record numbers, and dates of birth or day of the week);

concealment of allocation (low risk ‐ e.g. list from a central independent unit, on‐site locked computer, identically appearing numbered drug bottles or containers prepared by an independent pharmacist or investigator, or sealed opaque envelopes; unclear risk ‐ not described; high risk ‐ if allocation sequence was known to, or could be deciphered by the investigators who assigned participants or if the trial was quasi‐randomised);

blinding (of participants, personnel and outcome assessors);

incomplete outcome data (whether investigators used an intention‐to‐treat analysis);

selective outcome reporting;

other potential sources of bias.

We also noted whether the included trials reported any sample size calculations.

If we disagreed on a trial's evaluation, we reached a decision by consensus or by mediation by the contact editor. We present the results of the risk of bias assessment in the Risk of bias tables (Characteristics of included studies). The current author team did not re‐assess the judgements for trials previously included in the review.

Measures of treatment effect

For binary outcome measures, we calculated a pooled estimate of the treatment effect for each outcome across trials using risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), where appropriate.

For continuous outcomes, we recorded either mean relative change from baseline for each group and the standard deviation (SD). We presented a pooled estimate of treatment effect by calculating the mean difference (MD) and 95% CIs. If we become aware that some data are skewed and therefore we are not able to enter and analyse these within RevMan, we intend to report these narratively (RevMan 2020).

If other types of data are included in future updates of the review, we will analyse these as follows.

If future papers report standard errors (SE) for continuous data (and, if it is possible), we will convert these to SDs.

We will analyse any count data using a rate ratio (or narratively, if this is not possible).

For any time‐to‐event outcomes included in the review, we plan to obtain a mixture of logrank and Cox model estimates from the trials; we aim to combine all results using the generic inverse variance method as we hope to be able to convert the logrank estimates into log hazard ratios and SEs as detailed in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2021).

We will analyse longitudinal data using the most appropriate method available (Jones 2009).

Unit of analysis issues

An important factor in the validity of cross‐over trials is that the severity of the disease is stable, so that disease status at the start point of each period is similar. This is very unlikely to be the case for pulmonary exacerbations in CF and therefore we only included first‐arm data from any eligible cross‐over trials; where these data were unavailable, we excluded these trials from the review.

Dealing with missing data

Where possible, we have reported the numbers and reasons for dropouts and withdrawals in all intervention groups. We have also stated whether the papers specify that there were no dropouts or withdrawals. We contacted the first author of the cross‐over trial to ask if data from the first treatment period were available (3 August 2021). The lead author (Dr Freddy Frost) provided these data, which we have included in the review.

In order to allow an intention‐to‐treat analysis, we sought data on the number of participants with each outcome event, by allocated treated group, irrespective of compliance and whether or not the individual was later thought to be ineligible or otherwise excluded from treatment or follow‐up.

Assessment of heterogeneity

If sufficient data had been available, we planned to assess the degree of heterogeneity between trials through visual examination of the combined data presented in the forest plots, and by considering the I² statistic together with Chi² values and their CIs (Deeks 2021). The I² statistic is a measure which describes the percentage of total variation across trials that are due to heterogeneity rather than by chance (Higgins 2003). The values of I² lie between 0% and 100%, and a simplified categorisation of heterogeneity that we planned to use is as follows (Deeks 2021).

0% to 40%: might not be important

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity*

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity*

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity*

*The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on firstly the magnitude and direction of effects, and secondly on the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from the Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2: uncertainty in the value of I2 is substantial when the number of trials is small).

Assessment of reporting biases

In the tables, we reported when the primary investigators took measurements during the trial, what measurements they reported within the published paper, and noted which data we reported in the review (Characteristics of included studies). For the full papers we have included, we compared the methods sections to the results sections to identify any potential selective reporting. We also used knowledge of the clinical background to identify standard outcome measures that were used, but may not have been reported by the investigators. We further attempted to assess the impact of the reporting of several surrogate outcomes that were not directly relevant.

If, in future updates, we are able to include a sufficient number of trials, we will attempt to assess whether our review is subject to publication bias by using a funnel plot. If we detect asymmetry, we will explore causes other than publication bias.

Data synthesis

If, in future updates of this review, we identify moderate to high levels of heterogeneity (as defined above), we will present pooled estimates of the treatment effect using a random‐effects model. If this level of heterogeneity is not identified, we will compute pooled estimates of the treatment effect for each outcome under a fixed‐effect model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In future, if we find moderate to high heterogeneity (over 50%) and are able to include a sufficient number of trials, we will investigate the possible causes further by performing subgroup analyses based on the dose of the inhaled antibiotic, the pathogen causing the exacerbation, the severity of the pulmonary exacerbation, the severity of respiratory disease prior to the exacerbation (FEV1 % predicted*), age of participants (children versus adults) and the duration and setting of treatment.

*We we will use the American Thoracic Society (ATS) airflow limitation severity classification (Pellegrino 2005).

| Degree of severity | FEV1 % predicted |

| Mild | over 70% |

| Moderate | 60% to 69% |

| Moderately severe | 50% to 59% |

| Severe | 35% to 49% |

| Very severe | less than 35% |

Sensitivity analysis

If we are able to include a sufficient number of trials in a future update of the review, we plan to perform a sensitivity analysis based on the risk of bias of the trials (e.g. including and excluding trials assessed as having a high risk of bias).

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

In accordance with current Cochrane guidance, we have included a summary of findings table for each comparison in the review. The two comparisons are:

inhaled antibiotics compared to IV antibiotics;

an inhaled antibiotic in addition to IV antibiotics compared to IV antibiotics.

We have selected the following seven outcomes, which we consider to be the most important, to include in the tables.

QoL (as measured by a validated tool such as CFQoL (Gee 2000) or CFQ‐R (Quittner 2009))

Time off work or school

Lung function (spirometry)

Need for additional antibiotics (IV or oral)

Time to next pulmonary exacerbation

Adverse events

Microbiology ‐ emergence of new or resistant strains

We used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of the evidence for each outcome based on the risk of bias within the trials, relevance to our population of interest (indirectness), unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency, imprecision of the results or high risk of publication bias. We downgraded the certainty of the evidence once if the risk was serious and twice if we deemed the risk to be very serious.

Results

Description of studies

For further details, please see the tables (Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Results of the search

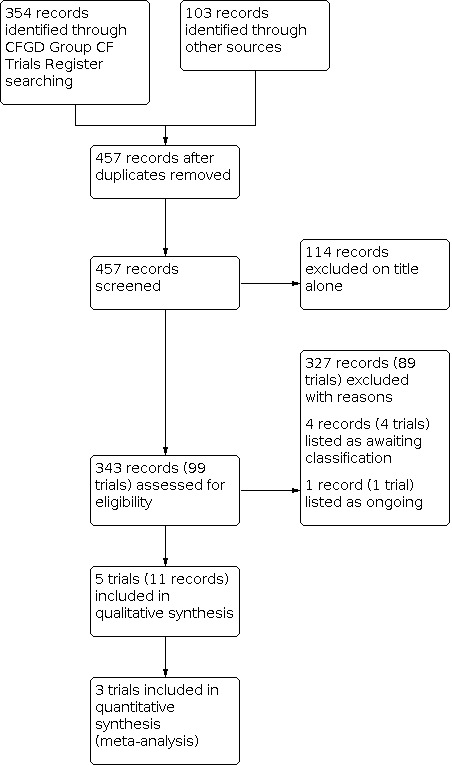

The searches identified 457 records; we excluded a total of 114 records on the basis of title alone and did not present any further details of these trials. We considered a total of 99 separate trials (343 records) in more detail. We included five trials in the review with a total of 183 participants and excluded 89 trials which are listed in Excluded studies. One trial was previously listed as ongoing (ACTRN12609000016235); it is now complete and has been moved to Studies awaiting classification. We have obtained some data from the author; however, it is a small, cross‐over trial for which separate first‐arm data have not yet been provided. We have contacted the author again (18 April 2018) for additional information and we will include this in a future update, if these data become available. Three further trials are currently awaiting classification (EUCTR2014‐003882‐10‐FR; Postnikov 2007; Semykin 2010) and one trial is listed as ongoing (NCT03066453). A flow chart showing the process of trial selection is presented in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

We found no trials comparing inhaled antibiotics to oral antibiotics.

Inhaled antibiotics alone versus IV antibiotics

Trial design

Two trials (77 participants) of parallel design were included in the review (Cooper 1985; Shatunov 2001). Duration of treatment was described as 14 days in one trial (Shatunov 2001) and not stated in the second trial (Cooper 1985). One trial specifically stated that participants were admitted to hospital for pulmonary exacerbations and treated as inpatients (Cooper 1985). In the remaining trial, it is not clear if participants were treated as inpatients or outpatients (Shatunov 2001). Both trials were conducted in a single centre in Canada (Cooper 1985) and Russia (Shatunov 2001).

Participants

The number of participants in each trial was 18 (Cooper 1985) and 59 (Shatunov 2001). Neither trial defined their criteria for the diagnosis of CF, but since both trials were conducted at CF centres and each was only reported in an abstract we have assumed that participants did indeed have CF and the lack of a description of the diagnosis was due to the limited word count available to the authors to provide details of their respective trials. Furthermore, neither trial gave a definition for a pulmonary exacerbation. One trial reported "pseudomonal‐related" pulmonary deterioration (Cooper 1985), and the second trial described participants as being chronically colonised or infected with P aeruginosa and having pulmonary exacerbations (Shatunov 2001). The age of the participants was only described by Shatunov 2001; this trial included children aged between five and 15 years (Shatunov 2001). Neither study described the number of male and female participants.

Interventions

Both trials compared inhaled antibiotic treatment to the same antibiotics given intravenously (Cooper 1985; Shatunov 2001). The drugs used by inhalation were tobramycin and carbenicillin (Cooper 1985) and ceftazidime (Shatunov 2001).

| Study ID | Active treatment | Comparator treatment(s) |

| Cooper 1985 | Inhaled tobramycin + inhaled carbenicillin (dose not specified) | IV ticarcillin + IV tobramycin (dose not specified) |

| Shatunov 2001 | Inhaled ceftazidime (1500 mg 1x daily) | IV ceftazidime (150 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses) or IV ceftazidime (150 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses) |

Outcomes

Both trials reported on lung function; FEV1 was reported in one trial (Cooper 1985) and the second trial described measuring "ventilation parameters and peak flowmetry" (Shatunov 2001). Other reported outcomes were the time until the next pulmonary exacerbation (Shatunov 2001), adverse effects (Cooper 1985), microbiological outcomes (Shatunov 2001), QoL (Cooper 1985) and need for additional IV antibiotics (Cooper 1985).

Both trials stated explicitly that they had measured outcomes at baseline and end of treatment (Cooper 1985; Shatunov 2001).

Inhaled antibiotics plus IV antibiotics versus IV antibiotics alone

Trial design

Three trials were included in this comparison (Frost 2018; Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983). One trial (16 participants) was of cross‐over design and we have only included data from the first intervention arm; the duration of treatment was 14 days (Frost 2018). This trial was based at a UK CF Centre (Frost 2018). Two trials (90 participants) were of parallel design (Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983). Duration of treatment in both was described as 14 days or two weeks (Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983) and both trials specifically stated that participants were admitted to hospital for pulmonary exacerbations and treated as inpatients (Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983). Both of these trials were conducted in single CF centres in Switzerland (Schaad 1987) and Canada (Stephens 1983).

Participants

The cross‐over trial included 16 adults (15 males and 1 female) with CF (Frost 2018). Their median age was 29.5 years; interquartile range (IQR) 24.5 to 32.5 years and the baseline mean (SD) FEV1 % predicted was 52.4% (14.7). Investigators defined pulmonary exacerbations using the modified Fuch's criteria (need for IV antibiotic treatment and a recent change in at least two of the following criteria: change in sputum colour or volume; increased cough; increased fatigue; malaise or lethargy; anorexia or weight loss (Fuchs 1994)) (Frost 2018).

The number of participants in one of the parallel trials was 62 with a mean age of 15 years (range 3 to 24 years) (Schaad 1987) and in the second 28, aged between seven and 22 years (Stephens 1983). Schaad did not describe the number of males and females in the trial (Schaad 1987), but Stephens included 18 males and 10 females (Stephens 1983). Neither trial defined their criteria for the diagnosis of CF but were treating participants in a CF centre, or gave a definition for a pulmonary exacerbation. One trial gave baseline FEV1 data to indicate the severity of the exacerbation (Stephens 1983). With regards to the pathogen causing the pulmonary exacerbation, there were no consistent inclusion criteria. In one trial, the isolation of P aeruginosa from sputum was a definite inclusion criterion (Schaad 1987). The second trial did not discuss possible causes of infection, although it was stated within the trial report that, at baseline, sputum colony counts of P aeruginosa were comparable between treatment and control groups (Stephens 1983).

Interventions

One trial compared the addition of aztreonam lysine for inhalation (AZLI) to IV colistimethate (Frost 2018). Two trials compared the addition of an inhaled antibiotic to an IV combination therapy that included the same drug given intravenously (Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983). The inhaled antibiotics were amikacin (Schaad 1987) and tobramycin (Stephens 1983).

| Study ID | Active treatment | Comparator treatment(s) |

| Frost 2018 | AZLI 75 mg 3 x daily plus IV colistimethate 2 mega (million) units 3 x a day. | IV colistimethate 2 mega (million) units 3 x a day plus a second IV antipseudomonal antibiotic selected by the admitting physician. |

| Schaad 1987 | Inhaled amikacin (100 mg 2 x daily) + IV ceftazidime (250 mg/kg/day in 4 divided doses) + IV amikacin (33 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses) | IV ceftazidime (250 mg/kg/day in 4 divided doses) + IV amikacin (33 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses) |

| Stephens 1983 | Inhaled tobramycin (80 mg) mixed with salbutamol (1 mL) plus buffering nebulising solution (2 mL) 3 x daily + IV tobramycin (10 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses) + IV ticarcillin (300 mg/kg/day in 4 divided doses) | IV tobramycin (10 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses) + IV ticarcillin (300 mg/kg/day in 4 divided doses) |

Outcomes

All three trials reported on lung function; two trials reported FEV1 (Frost 2018; Stephens 1983) and the third trial measured lung volumes and airway resistance during quiet breathing (Schaad 1987). Other reported outcomes were QoL measured as achievement of minimum clinically important difference (MCID) in the CFQ‐R Respiratory domain (Frost 2018), the time until the next pulmonary exacerbation (Frost 2018; Stephens 1983), adverse effects (Frost 2018; Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983), microbiological outcomes (Frost 2018; Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983), weight (Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983), and need for hospital admission (Stephens 1983).

All trials stated explicitly that they had measured outcomes at baseline and end of treatment; and one further reported follow‐up data at four to six weeks after end of treatment (Schaad 1987).

Excluded studies

We have listed 89 trials as excluded; reasons for exclusion are given in the tables (Characteristics of excluded studies). Most trials were excluded as they were in people with chronic disease, not an exacerbation (n = 45); some trials stated that participants were clinically stable (n = 9) or that they were undergoing maintenance treatment (n = 4); and two trials were single‐dose trials. Seven trials looked at eradication treatment and two at prophylaxis. Two trials looked at the correct intervention in the correct population, but were of cross‐over design and first‐arm data were not available. In two trials, the intervention was not an inhaled antibiotic. One trial looked at inhaled tobramycin but both arms received this treatment whilst the intervention arm was given oral azithromycin in addition and the comparator arm was given an oral placebo. In the remaining 15 trials, participants were not included if they had pulmonary exacerbations.

Studies awaiting classification

There are four trials awaiting classification (ACTRN12609000016235; EUCTR2014‐003882‐10‐FR; Postnikov 2007; Semykin 2010).

One trial currently awaiting classification is an open‐label cross‐over RCT in 24 people over six years of age and with chronic P aeruginosa infection experiencing an exacerbation (ACTRN12609000016235). Investigators compared IV tobramycin at the dose they received on their last admission (usually 7 to 10 mg/kg) once daily for 14 days versus inhaled tobramycin at a dose of 300 mg twice daily for 14 days. Outcomes include lung function, time to next exacerbation, adverse events (renal function and antibiotic resistance), weight and QoL (ACTRN12609000016235).

One trial is only available as an abstract and trial registration document and compares five days of IV tobramycin followed by 14 days of inhaled tobramycin with 14 days of IV tobramycin; however, there was not enough information to include it at this update (EUCTR2014‐003882‐10‐FR).

One trial is a two‐arm cross‐over trial which lasted two weeks and recruited 15 children aged between seven and 17 years of age (Postnikov 2007). Participants received either once‐daily or twice‐daily amikacin at a dose of between 15 mg/kg/day and 20 mg/kg/day in combination with ceftazidime or meropenem. The investigators planned to report on lung function, microbiology, and adverse events at baseline and at day 14. It is currently not clear from the abstract whether the amikacin was inhaled or IV (Postnikov 2007).

The final trial awaiting classification is a three‐arm parallel trial in 108 participants aged between four and 17 years with chronic P aeruginosa infection experiencing an exacerbation (Semykin 2010). Treatments compared were twice‐daily TOBI 300 mg or twice‐daily Bramitob 300 mg (both in combination with IV ceftazidime and oral ciprofloxacin) versus IV cefepime plus IV amikacin versus IV meropenem plus IV amikacin. Investigators measured clinical symptoms, lung function, and microbiology. To date, this trial has only been published as an abstract (Semykin 2010).

Ongoing studies

One cross‐over trial is ongoing (NCT03066453). Investigators are recruiting participants of at least eight years of age with chronic P aeruginosa infection experiencing an exacerbation. The treatment comparison is a 'short cure' (14 days of IV nebcin plus five days of IV tobramycin followed by nine days of inhaled tobramycin (Tobi Inhalant Product) 300 mg twice daily) versus 'standard' treatment (14 days IV nebcin plus 14 days of IV tobramycin).

Risk of bias in included studies

Summary figures for the risk of bias are presented in the figures (Figure 2; Figure 3).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Generation of sequence

One trial was at low risk of bias as investigators used a computer program to generate the randomisation sequence (Frost 2018). We judged all of the remaining four trials to have an unclear risk of bias. Three of the trials described participants as being randomly allocated to groups but gave no description of the randomisation process (Cooper 1985; Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983). One trial stated that participants were "divided into three groups" but again, no details of the process were given (Shatunov 2001).

Concealment of allocation

Investigators in the Frost trial concealed allocation by using opaque envelopes which remained sealed until the participant had their first exacerbation and we deemed the risk of bias to be low (Frost 2018). None of the remaining trials discussed allocation concealment and hence we judged these to have an unclear risk of bias (Cooper 1985; Schaad 1987; Shatunov 2001; Stephens 1983).

Blinding

We assessed the risk of bias from blinding of participants, of caregivers or clinicians separately to the risk from blinding of outcome assessors.

Performance bias

Given that the interventions being compared were either inhaled antibiotics or a combination of inhaled and IV antibiotics versus IV antibiotics and there were no placebo interventions, it was not possible to blind either the participants or the caregivers to the treatment arm. This has resulted in all trials being judged to have a high risk of bias for blinding in the groups 'participant' and 'caregiver or clinician'. Given that the majority of the outcomes in this review are not subjective, it is unclear how this risk of bias will impact on the results.

Detection bias

However, the blinding of outcomes assessors would have been possible. Two trials reported that outcome assessors were blinded to the treatment group (Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983). Schaad reported individuals who had no knowledge of treatment group assessed clinical evaluations, radiographs and sputum analysis (Schaad 1987). Stephens only reported that the technician performing the lung function tests was not aware of the treatment group and did not give any details for other outcomes (Stephens 1983). We have judged these two trials to have a low risk of bias (Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983). The remaining three trials did not discuss blinding of outcome assessors and we judged these to have an unclear risk of bias (Cooper 1985; Frost 2018; Shatunov 2001).

Incomplete outcome data

We judged three trials to have an unclear risk of bias as they did not discuss withdrawals (Cooper 1985; Shatunov 2001; Stephens 1983).

We regarded the trial by Schaad to have a high risk of bias; this was because investigators did not report all outcomes for all of the participants, and did not provide reasons for this (Schaad 1987).

The authors of the cross‐over trial provided first‐arm data which was complete and we deemed this trial to be at low risk of bias for this domain (Frost 2018).

Selective reporting

Three trials have been published as full papers (Frost 2018; Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983). In the cross‐over trial, investigators reported results for all outcomes listed in the methods section and in the clinical trial documentation. The authors were able to provide us with first‐arm data and we deemed the risk of bias from selective outcome reporting to be low (Frost 2018). The Schaad paper appears to be consistent between those outcomes stated as being measured and those mentioned in the results section, giving this trial a low risk of bias (Schaad 1987).

The Stephens paper explicitly stated that FVC would be measured, but reported no data for this outcome. Also, investigators measured outcomes on days 1, 5 and 12, but the table in the paper only presented clinical status data for the start and end of treatment (Stephens 1983). While it is unclear whether the trial investigators have selectively reported data by time point, we judged this trial to have a high risk of bias.

Two of the included trials were only published as abstracts and so it was not clear from the available information if all the outcomes investigators planned to measure were indeed reported (Cooper 1985; Shatunov 2001). We therefore judged both of these trials to have an unclear risk of bias.

We would also like to note that for the outcome 'Time to next pulmonary exacerbation', the trial reporting this outcome presented data in a manner which did not allow us to undertake our planned analysis (we planned to use hazard ratios), which we regard as a potential form of selective reporting (Shatunov 2001).

Other potential sources of bias

We judged one trial as having a high risk of bias for this domain (Schaad 1987). Schaad reported that 13 participants enrolled twice and six participants participated three times (Schaad 1987).

For two trials, we did not identify any other potential source of bias, and thus judged these as having a low risk of bias (Frost 2018; Stephens 1983).

The remaining two trials were both only published in abstract form and so, due to limited information e.g. no information on formal CF diagnosis or definition of pulmonary exacerbation, we were not able to identify any other potential sources of bias; we have therefore judged these to have an unclear risk of bias (Cooper 1985; Shatunov 2001).

Effects of interventions

In the summary of findings tables, we have graded the certainty of the evidence for predefined outcomes (see above) and provided definitions of these gradings (Table 1; Table 2).

Inhaled antibiotics alone versus IV antibiotics

Two trials (n = 77) reported on this comparison (Cooper 1985; Shatunov 2001) and we have summarised the results in the tables (Table 1).

Primary outcomes

1. QoL

One abstract stated 'perceived improvement in lifestyle' as an outcome that occurred in both groups in the trial (n = 18); however, investigators did not report any results (Cooper 1985). We deemed the certainty of this evidence to be very low.

2. Time off work or school

Neither trial reported on this outcome.

3. Lung function

Both trials stated that lung function was an outcome measure. One trial (n = 59) did not specify which 'ventilatory parameters' were measured (Shatunov 2001). The abstract reported no difference in treatment with twice‐daily IV ceftazidine or once‐daily inhaled ceftazidine, but that both of these treatment regimens were better than treatment with three‐times daily IV ceftazidine (P < 0.05) (Shatunov 2001).

a. FEV1

Cooper (n = 18) reported FEV1 % predicted was 42% before treatment and 55% post‐treatment in the inhaled tobramycin and carbenicillin group and 39% before treatment and 52% after treatment in the IV antibiotic group (same combination of drugs given intravenously); there was no statistically significant difference in FEV1 at end of treatment between treatment or control. There was insufficient information for meta‐analysis (Cooper 1985).

We deemed the GRADE evidence for this outcome to be very low‐certainty (Table 1).

b. FVC

Only Cooper (n = 18) reported the mean FVC % predicted at the end of treatment. In the group on inhaled antibiotics (n = 8), this was 73% predicted compared to 68% predicted in the group receiving the same antibiotics intravenously (n = 10) (Cooper 1985).

c. Annual change in FEV1

Neither trial reported on this outcome.

Secondary outcomes

1. Need for hospital admission

Neither trial reported on this outcome.

2. Need for additional antibiotics

a. IV

One trial (n = 18) reported that two participants from the inhaled group needed additional IV antibiotics, RR 6.11 (95% CI 0.33 to 111.71) (Analysis 1.1) (Cooper 1985). We again deemed the GRADE evidence to be very low‐certainty.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Inhaled antibiotics versus intravenous antibiotics, Outcome 1: Need for additional IV antibiotics

b. oral

Neither trial reported on the need for additional oral antibiotics.

3. Time to next pulmonary exacerbation

Only one trial (n = 59) reported information on the time to the next pulmonary exacerbation, but not in a format that allowed a meta‐analysis (Shatunov 2001). Our original planned analysis was not possible as this trial did not report hazard ratios.

Shatunov reported that the time to next exacerbation was maximal in the once‐daily inhaled antibiotic group, less in the twice‐daily IV antibiotic group, but both longer than in the group receiving IV antibiotics three‐times‐daily (Shatunov 2001).

4. Weight

Neither trial reported on weight.

5. Adverse effects

a. Mild

Neither trial reported on this outcome.

b. Moderate

Cooper (n = 18) monitored renal and auditory changes and reported no adverse effects in either the inhaled or the IV antibiotic groups (Cooper 1985).

c. Severe

Neither trial reported on this outcome.

6. Microbiology

Both trials (n = 77) measured this outcome (Cooper 1985; Shatunov 2001). Cooper (n = 18) stated that there were no adverse effects seen in sputum microbiology (Cooper 1985).

a. Emergence of new organisms

No trials reported on the emergence of new organisms.

b. Emergence of resistant organisms

Shatunov stated that this outcome was to be measured, but did not report any results (Shatunov 2001).

Inhaled antibiotics plus IV antibiotics versus IV antibiotics alone

Three trials reported on this comparison (n = 106) (Frost 2018; Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983). Due to multiple enrolments in the Schaad trial, data were reported on episodes, rather than on participants (therefore not independent), and thus we could not enter data into the meta‐analysis for any of the outcomes listed below (Schaad 1987). We have summarised the results in the tables (Table 2). We have only reported results from the first intervention arm for the Frost trial as it was a cross‐over trial and we had prespecified that we would exclude cross‐over trials unless they present first‐arm data. The authors kindly provided these data.

Primary outcomes

1. QoL

One trial (n = 16) reported on this outcome by giving the number of participants in each group who achieved a minimum clinically important difference (MCID) in the CFQ‐R Respiratory domain (Frost 2018). Investigators observed no difference between the groups during the first arm of this cross‐over trial, RR 1.20 (95% CI 0.61 to 2.34) (Analysis 2.1). However, results presented in the paper used data from both intervention periods and showed that MCID was achieved more frequently with AZLI + IV (10 out of 12 participants, 83.3%) compared to IV + IV (7 out of 16 participants, 43.8%) P = 0.04 (Frost 2018).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Inhaled antibiotics plus intravenous antibiotics versus intravenous antibiotics, Outcome 1: Participants achieving MCID in CFQ‐R respiratory domain

We deemed the GRADE quality of evidence to be low‐certainty.

2. Time off work or school

None of the trials reported on this outcome.

3. Lung function

All three trials stated that lung function was an outcome measure (Frost 2018; Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983).

a. FEV1

One trial (n = 16) reported change from baseline in FEV1 % predicted after 14 days of treatment (Frost 2018). There was no difference between groups, MD ‐2.60 (95% CI ‐11.26 to 6.06) (Analysis 2.2). The original paper reported results from both treatment periods and showed that after 14 days of treatment, AZLI + IV was associated with a greater improvement in lung function than IV + IV, MD 4.6% (95% CI 2.1 to 7.2) (P = 0.002). The trial authors further reported that this result was robust regardless of baseline lung function (Frost 2018).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Inhaled antibiotics plus intravenous antibiotics versus intravenous antibiotics, Outcome 2: FEV1 change from baseline % predicted at 14 days

One trial (n = 28) reported the change from baseline in FEV1 % predicted, but there was insufficient information for meta‐analysis (Stephens 1983). There was a 6.7% change in the group receiving the combination of inhaled and IV antibiotics and a 3.9% change in the IV antibiotics only group; the paper described the difference between groups as not statistically significant (Stephens 1983).

The GRADE evidence for this outcome was deemed to be very low‐certainty.

b. FVC

None of the trials reported FVC, but Schaad reported results of vital capacity (VC) measured during quiet breathing across 87 datasets from 62 participants (Schaad 1987). At the end of the two‐week treatment, the mean (SD) VC % predicted for the inhaled amikacin plus IV amikacin and ceftazidine group (n = 30) was 57% (16%) and for the group (n = 24) given both drugs IV was 62% (16%). At follow‐up four to six weeks later, the inhaled plus IV group (n = 12) had a mean (SD) VC % predicted of 51% (20%) and the IV alone group (n = 14) of 57% (17%).

c. Annual change in FEV1

None of the trials reported on this outcome.

Secondary outcomes

1. Need for hospital admission

One trial (n = 28) reported on the need for hospital admission (Stephens 1983); the results showed no difference between groups, RR 1.50 (95% CI 0.15 to 14.68) (Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Inhaled antibiotics plus intravenous antibiotics versus intravenous antibiotics, Outcome 3: Need for hospital admission

2. Need for additional antibiotics

None of the trials reported on the need for either additional IV or additional oral antibiotics.

3. Time to next pulmonary exacerbation

Only the cross‐over trial (n = 16) reported on the time to next pulmonary exacerbation (Frost 2018). In the first intervention arm only, the mean time to the next exacerbation in the AZLI + IV group was 140 days compared to 190 days in the group that received IV + IV treatment (log rank P = 0.51). The corresponding SDs were not available so we were not able to include these data in our analysis (Frost 2018). When the trial authors reported the full dataset, there was no difference between groups in time to next exacerbation (Frost 2018).

4. Weight

Two trials reported data for weight, although we were not able to enter data from either trial into a meta‐analysis (Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983).

Schaad reported on weight as degree of underweight (%) at the end of treatment and at follow‐up (Schaad 1987). At the end of treatment, Schadd reported in the IV plus inhaled group (n = 43) a mean (SD) % of underweight as 13.1% (7.1%) compared to the IV alone group (n = 44) where mean (SD) was 13.5% (7.3%). At follow‐up (four to six weeks), in the IV plus inhaled group (n = 36), the mean (SD) % of underweight was 14.8% (7.7%) compared to the IV alone group, where the mean (SD) was 14.9% (7.8%) (Schaad 1987).

Stephens reported that the mean change in weight for the inhaled group (n = 16) was 1.7 and in the control group (n = 12) was 2.2 (Stephens 1983). The units of weight were not specified and no variance measures were reported. The paper reported that the difference was not significant.

5. Adverse effects

The cross‐over trial reported adverse events, but only for the whole dataset rather than the first arm only. There were treatment‐emergent adverse events in 10 out of 16 participants which occurred at similar frequencies for both treatment groups. The most common adverse event was the need for more than 14 days of antibiotics and occurred equally for each group. Exaggerated cough was only reported in the AZLI + IV arm, but did not result in discontinuation (Frost 2018).

a. Mild

One trial reported mild adverse events, but did not state in which of the treatment groups these events had occurred and we are not able to present these in the analysis (Schaad 1987). Phlebitis was reported in five participants (6%) and urticarial rash in a further four (5%) participants. Furthermore, Schaad reported no significant changes in blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and urine analysis (Schaad 1987).

b. Moderate

Two trials reported on moderate adverse events (Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983).

Schaad reported on moderate adverse events, but as before did not break these down by treatment group, precluding inclusion in the analysis (Schaad 1987). Pre‐ and post‐treatment audiograms were performed in 81 (93%) out of 87 participants and interpreted as unchanged in all. While investigators noted a more than three‐fold increase in aspartate transaminase (SGOT) and alanine aminotransferase (SGPT) activities in five out of 87 participants at the end of therapy, this was not the case at follow‐up. Investigators also noted further transient haematologic abnormalities in eight participants, as follows: four developed eosinophilia; three developed neutropenia; and one developed thrombocytopenia (Schaad 1987).

Stephens reported that there were no reports of renal toxicity in either group (Analysis 2.4). Furthermore, serum creatinine levels remained at less than 1.0 mg/dL and did not increase by more than 0.5 mg/dL in any participant; no proteinuria or cylinduria were observed in either group (Stephens 1983). Our GRADE assessment for moderate adverse events was very low‐certainty.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Inhaled antibiotics plus intravenous antibiotics versus intravenous antibiotics, Outcome 4: Adverse events

c. Severe

Schaad reported that there were no significant adverse events observed in either group (Schaad 1987).

6. Microbiology

Two trials reported on this outcome (Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983).

a. Emergence of new organisms

Neither trial reported on the emergence of new organisms.

b. Emergence of resistant organisms

Schaad reported that, at the end of treatment, two out of 39 strains were resistant to ceftazidime and two were resistant to amikacin in the group using inhaled amikacin combined with IV amikacin and ceftazidime. In the group treated with the same IV antibiotics, three out of 39 strains were resistant to ceftazidime and one to amikacin (Schaad 1987). Stephens (n = 28) reported that there was no difference in the rate of P aeruginosa isolates being resistant to inhaled tobramycin, RR 2.25 (95% CI 0.27 to 19.04) (Analysis 2.5) (Stephens 1983). Our GRADE assessment found the evidence to be of very low‐certainty.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Inhaled antibiotics plus intravenous antibiotics versus intravenous antibiotics, Outcome 5: Development of resistant organisms

Discussion

Pulmonary exacerbations associated with chronic P aeruginosa infection are well‐recognised in people with CF, although there is no agreed definition and pathophysiology is not well understood. Exacerbations are associated with both short‐ and long‐term effects on health (Sanders 2010). The usual treatment of exacerbations is a combination of two antibiotics delivered intravenously and increased airway clearance for two to three weeks, frequently in hospital (Flume 2009; Gibson 2003a). In some instances, oral antibiotic treatment (ciprofloxacin) is the first antibiotic used. There has been limited research on the effect of inhaled antibiotics for treatment of pulmonary exacerbations in people with CF. The rationale to undertake these trials is to provide people with CF with therapeutic options that are less invasive and potentially less toxic but equally effective as compared to other treatment options (e.g. IV antibiotics).

Summary of main results

We identified five RCTs with 183 participants from our search of the literature (Cooper 1985; Frost 2018; Schaad 1987; Shatunov 2001; Stephens 1983). Many outcome measures of interest were either not reported or reported in different ways meaning we could not include any data in a meta‐analysis, although we have presented some data in the forest plots. We found trials comparing inhaled antibiotics to IV antibiotics and trials comparing inhaled antibiotics in combination to IV antibiotics alone, but no trials comparing inhaled antibiotics to oral antibiotics.

Inhaled antibiotics alone versus IV antibiotics

Two trials compared inhaled antibiotics alone to IV antibiotics alone (n = 77) (Cooper 1985; Shatunov 2001). Regarding QoL, one trial (abstract only) narratively reported that participants perceived an improvement in lifestyle (very low‐certainty evidence) (Cooper 1985). With regards to lung function, the smaller trial found no difference between groups in either FEV1 % predicted (very low‐certainty evidence) or FVC % predicted (Cooper 1985). The larger trial did not specify which 'ventilatory parameters' were measured, but reported no difference between twice‐daily IV ceftazidine or once‐daily inhaled ceftazidine, but that both of these treatment regimens were better than treatment with three‐times daily IV ceftazidine (Shatunov 2001).

The smaller trial found no difference in the need for additional IV antibiotics (very low‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.1) (Cooper 1985). Only the larger trial reported on the time to the next pulmonary exacerbation which was maximal in the once‐daily inhaled antibiotic group, less in the twice‐daily IV antibiotic group, but both longer than in the group receiving IV antibiotics three‐times‐daily (Shatunov 2001). Only one trial assessed moderate adverse events (renal and auditory) (very low‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.2) and adverse effects in sputum and reported none in either group (Cooper 1985). Neither trial reported time off work or school, need for hospital admission, need for oral antibiotics, weight, mild or severe adverse events or the emergence of new or resistant organisms (Cooper 1985; Shatunov 2001).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Inhaled antibiotics versus intravenous antibiotics, Outcome 2: Adverse events

Inhaled antibiotics plus IV antibiotics versus IV antibiotics alone

Three trials (n = 106) compared a combination of inhaled and IV antibiotics to IV antibiotics alone (Frost 2018; Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983).

Only one trial (n = 16) reported results on our primary outcome of change in QoL (Frost 2018). No difference was found in the achievement of MCID between inhaled plus IV antibiotics or IV antibiotics alone (low‐certainty evidence) (Frost 2018). Two trials reported data for FEV1 (very low‐certainty evidence); one trial provided data we were able to analyse and which showed no differences between treatment groups (Analysis 2.2) (Frost 2018), while the second narratively reported no difference between groups (Stephens 1983). The third trial reported VC measured during quiet breathing and found similar results in both groups at the end of the two‐week treatment and at follow‐up four to six weeks later (Schaad 1987).

One trial found no difference in the need for hospital admission between groups (Stephens 1983). The cross‐over trial (n = 16) reported on the time to next pulmonary exacerbation, but only reported the mean number of days without corresponding SDs for the first arm; the time to the next exacerbation in the inhaled plus IV antibiotics group was 140 days compared to 190 days in the group that received IV treatment alone (log rank P = 0.51) (low‐certainty evidence) (Frost 2018). The investigators noted that after both treatment arms, no difference was seen between groups. Two trials reported on weight (Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983). One trial reported similar numbers of participants in each group were underweight both after treatment and at follow‐up (Schaad 1987); the second trial reported no difference in change in weight between groups after treatment (Stephens 1983). The cross‐over trial reported similar numbers of treatment‐emergent adverse events for the whole trial duration and data were not available for the first arm only (Frost 2018). One trial reported small numbers of mild adverse events, some transient moderate adverse events but no severe adverse events; the groups in which these occurred were not specified (Schaad 1987). Stephens reported that there were no differences in moderate adverse events (Analysis 2.4); the GRADE assessment for moderate adverse events was very low‐certainty. Two trials reported on the emergence of resistant organisms; Schaad reported narratively and found no difference between treatment groups (Schaad 1987); while analysable data from Stephens showed no difference in the rate of P aeruginosa isolates being resistant to inhaled tobramycin (Analysis 2.5) (Stephens 1983). The GRADE assessment found the evidence to be of very low‐certainty.

No trial reported time off work or school, the need for either additional IV, or additional oral antibiotics (Frost 2018; Schaad 1987; Stephens 1983).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Two of the included trials used inhaled tobramycin which is the most commonly‐used inhaled antibiotic; one of these combined it with inhaled carbenicillin but did not specify the dose (Cooper 1985) and the second combined it with IV tobramycin and IV ticarcillin (Stephens 1983). Trials were varied in design and specific intervention and comparator, making meta‐analyses of the results not appropriate.

The trials included in this review were designed to show that inhaled antibiotics are equally as effective as other treatment options. Such equivalence trials require large numbers of participants to ensure confidence in the results. The included trials all had a small sample size, which would make them prone to a Type II error; indeed, in the three trials which provided data on lung function, there were only 62 participants and a difference could have been missed (Cooper 1985; Stephens 1983; Frost 2018). One of the trials was a cross‐over trial from which we could only include the first treatment‐arm data in our review (Frost 2018).

Four of the included trials were over 20 years old and, in a fast‐moving area of treatment development, it brings into question the applicability of any results to the current domain. A more recent trial included at this update had a cross‐over design and we previously specified in our protocol that due to the chronic and deteriorating nature of CF, a cross‐over trial would not be appropriate as the baseline values were likely to be different between first and second treatment. We have therefore only included data from the first treatment arm (Frost 2018).

Our primary outcome was change in QoL; this was only measured in two of the five included trials, one in each comparison (Cooper 1985; Frost 2018), and only the cross‐over trial reported results (after the first treatment arm) which we could analyse (Frost 2018).