Monkeypox was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) by the WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus on July 23, 2022. This is the seventh declaration of a PHEIC since 2005. The PHEIC is governed by the International Health Regulations (IHR). A PHEIC should be declared if a disease outbreak is an extraordinary event; when it constitutes a public health risk to other states through international spread; and when a coordinated international response is potentially required.1 During the revisions of the IHR in 2005, governments wanted to limit the power of the WHO Director-General to impose trade and travel restrictions,2 following WHO's actions during the 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) when the WHO Director-General at the time took unprecedented steps to recommend travel restrictions to mitigate the spread of the virus,3 which resulted in severe economic impacts in the countries affected.4 The IHR (2005) created a technical Emergency Committee (EC) of experts from a roster of specialists with expertise in a range of different pathogens and contexts, selected for each EC on the basis of the disease event. The EC advises the WHO Director-General whether a disease outbreak should be declared a PHEIC, and accordingly, what public health recommendations should be advised to member states, although the final decision remains with the WHO Director-General. The EC was intended to turn PHEIC decision making into a technical process and control the political discretion of a Director-General.

During all six previous PHEICs declared (the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, poliovirus in 2014, Ebola virus disease in west Africa in 2014, Zika virus disease in 2016, Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2019, and COVID-19 in 2020), the WHO Director-General has followed the advice of the EC, even when that advice has deviated from the strict legal criteria for declaring a PHEIC within the IHR.2 This history of decision making has raised questions about the role of the WHO Director-General in the process as simply certifying the EC assessment, and the extent to which a decision as important as the PHEIC declaration was actually being taken by an unaccountable technocratic body.2

The declaration of a PHEIC for monkeypox was the first time that the WHO Director-General has departed from the assessment of the EC in declaring a PHEIC.5 This development in PHEIC decision making is important for how we understand contemporary disease control, the role of WHO, and global health governance in four crucial areas.

First, we understand that there was a vote taken by EC members as to whether they believed the PHEIC criteria had been met for monkeypox.6, 7 This decision-making process within an EC meeting is not detailed in the IHR, although some previous ECs have documented the fact that they voted in press conferences.2 Indeed, given the lack of transparency in the EC process,8 how previous ECs have reached decisions is not publicly known; it seems to vary for different ECs whether majority decision making or a consensus model is adopted.2 This variation matters for the consistency of the PHEIC process, the outcome, and the normative authority of WHO in making a PHEIC declaration.

Moreover, we understand that during the deliberations about monkeypox the voting was polarised between those advocating for LGBTQI health needs (monkeypox is predominantly occurring among men who have sex with men [MSM] outside of west and central Africa)9 and more generalist global public health specialists.7 Others have expressed concerns about the utility of the PHEIC declaration and whether it would increase stigma and would have no added benefit to the epidemic trajectory.7 Although there are clear criteria for a PHEIC to be declared, other assessments have previously come into the EC process—eg, whether the PHEIC would create additional problems in an already complex emergency with the fuelling of an informal and formal Ebola economy in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or the role of the Olympic Games during the Zika epidemic—which undermined the PHEIC decision-making process, and the power of the PHEIC as a tool in global disease control.

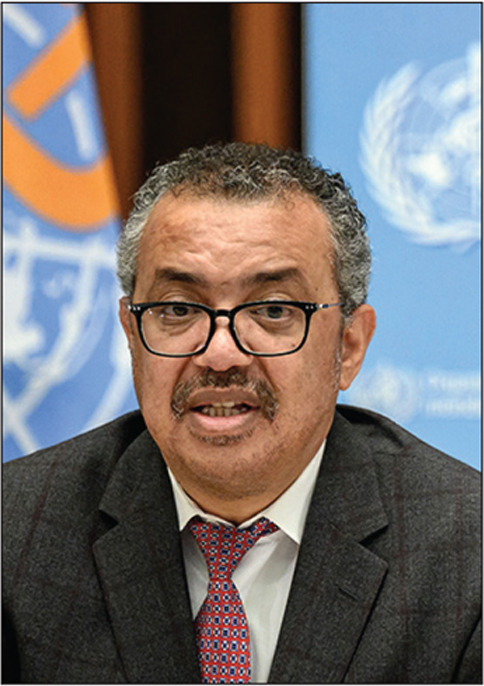

© 2022 Fabrice Coffrini/AFP via Getty Images

Second, the decision of the WHO Director-General to overrule the decision making of the EC in this instance shows that WHO is a politically engaged actor, capable of embracing and engaging with political considerations. This political dimension is clear, with the WHO Director-General willing to use the discretionary powers bestowed on him as an elected official to depart from the assessment of a technical committee. This decision by the Director-General not only demonstrates WHO's own assessment of the potential severity of monkeypox within global health, but given that the current monkeypox outbreak has so far mainly, but not exclusively, affected MSM,9 it shows WHO's political commitment to protecting traditionally marginalised groups from technical decision-making bodies that might not have appreciated the gendered or downstream effects of inaction, or do not seek to mainstream the needs of those most affected.10 Typically, WHO seeks to shy away from political statements or engagement, despite the clear political work that WHO does.11 However, the decision to declare monkeypox a PHEIC is a much-needed development for an increasingly politicised WHO. Increased politicisation of the organisation would enable the breaking through of the frequent deadlocks in global health policy making by taking decisions that may challenge some states' positions domestically or internationally on issues such as universal health coverage or sexual and reproductive health and rights. However, many member states are unlikely to welcome a more politically engaged WHO, preferring a neutral body that remains beholden to the decision making of its members, rather than assuming its own position as an independent actor.

Third, during the COVID-19 pandemic WHO has lost considerable influence and authority in health emergencies.12 At a time when WHO should have been the central coordinating authority in the response to a global threat, many member states did not follow WHO recommendations,13 and WHO has long struggled with sustainable financing and influence.14 This inability to influence state behaviour during the past 3 years of the COVID-19 pandemic has weakened the normative power of WHO and to some extent undermined its disease control activities. This monkeypox PHEIC declaration can be seen as an attempt to reclaim some authority in global disease control and demonstrate to states and the global health community that WHO can act in this central role and is not afraid to use the powers it has been endowed with.

Finally, what impact does a PHEIC have? One question that is uncertain at this stage is will the PHEIC declaration work to help tackle monkeypox? Will states pay any attention to the PHEIC declaration and follow WHO guidance, despite the decision not being rubber-stamped by due process of the EC? In the press conference announcing the monkeypox PHEIC, the WHO Director-General implied that the PHEIC declaration might lead to increased support, vaccine production, and more equitable access to such vaccines or medical countermeasures, and global coordinated action to combat the spread of monkeypox, while adhering to the human rights obligations within the IHR and wider human rights norms.15, 16 This sentiment is shared by many commenting on the PHEIC,6, 7, 17 with the underlying assumption that the PHEIC is the switch to turn on action by a range of stakeholders. However, whether a PHEIC declaration improves disease control is not known. There are no systematic analyses or data sources to determine what effect the PHEIC notification has. There is nothing in the IHR to delineate what occurs on PHEIC notification, other than the WHO Director-General having the power to make recommendations to governments—recommendations that are frequently ignored, particularly around trade and travel restrictions.18, 19

Before we make broad statements about the importance of the PHEIC or consider the role of the PHEIC in IHR reform or the proposed pandemic treaty,20 we need to understand what effect the PHEIC has in outbreak response: if this is meaningful or negligible. For a discipline that is so dominated by evidence-based decision making, the fact that such decisions are made on the assumption of the normative power of the PHEIC—and indeed of WHO—demands greater scrutiny.

Acknowledgments

CW is a member of the technical advisory group of the Universal Health and Preparedness Review (UHPR) within WHO. ME-T has informally advised the UK Government on the development of the pandemic treaty. We declare no other competing interests.

References

- 1.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2005. Article 1, International Health Regulations (2005) UNTS 2509. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eccleston-Turner M, Wenham C. Bristol University Press; Bristol: 2021. Declaring a public health emergency of international concern: between international law and politics. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamradt-Scott A. Palgrave Macmillan; London: 2015. Managing global health security. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keogh-Brown M, Smith R. The economic impact of SARS: how does the reality match the predictions? Health Policy. 2008;88:110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO WHO Director General's statement following IHR Emergency Committee regarding the multi-country outbreak of monkeypox. July 23, 2022. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-statement-on-the-press-conference-following-IHR-emergency-committee-regarding-the-multi--country-outbreak-of-monkeypox--23-july-2022

- 6.Rigby J. Reuters; July 23, 2022. WHO experts split on monkeypox emergency ahead of decision—sources.https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/who-experts-split-monkeypox-emergency-ahead-decision-sources-2022-07-23/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kupferschmidt K. WHO Chief declares monkeypox an international emergency after emergency panel fails to reach consensus. Science. 2022 doi: 10.1126/science.ade0761. published online July 23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eccleston-Turner M, Kamradt-Scott A. Transparency in IHR emergency committee decision making: the case for reform. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO Monkeypox: outbreak 2022. 2022. https://www.who.int/europe/health-topics/monkeypox#tab=tab_2

- 10.Wenham C. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2021. Feminist global health security. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Louis M, Maertens L. 1st edn. Routledge; London: 2021. Why international organizations hate politics: depoliticizing the world. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies SE, Wenham C. Why the COVID-19 response needs international relations. Int Aff. 2020;96:1227–1251. doi: 10.1093/ia/iiaa135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dias Simoes F. Pandemics, travel restrictions, and the distancing from international law. Asian J WTO Int Health Law Policy. 2021;16:249–274. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reddy SK, Mazhar S, Lencucha R. The financial sustainability of the World Health Organization and the political economy of global health governance: a review of funding proposals. Global Health. 2018;14:119. doi: 10.1186/s12992-018-0436-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO WHO Director-General declares the ongoing monkeypox outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. July 23, 2022. https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/23-07-2022-who-director-general-declares-the-ongoing-monkeypox-outbreak-a-public-health-event-of-international-concern

- 16.WHO Second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR) Emergency Committee regarding the multi-country outbreak of monkeypox. July 23, 2022. https://www.who.int/news/item/23-07-2022-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-(ihr)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-multi-country-outbreak-of-monkeypox

- 17.Zarocostas J. Monkeypox PHEIC decision hoped to spur the world to act. Lancet. 2022;400:347. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01419-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Habibi R, Hoffman SJ, Burci GL, et al. The Stellenbosch Consensus on Legal National Responses to Public Health Risks: clarifying Article 43 of the International Health Regulations. Int Organ Law Review. 2020;19:90–157. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Habibi R, Burci GL, de Campos TC, et al. Do not violate the International Health Regulations during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet. 2020;395:664–666. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30373-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO Intergovernmental Negotiating Body. 2022. https://apps.who.int/gb/inb/