Abstract

Mnemonic similarity task performance, in which a known target stimulus must be distinguished from similar lures, is supported by the hippocampus and perirhinal cortex. Impairments on this task are known to manifest with advancing age. Interestingly, disrupting hippocampal activity leads to mnemonic discrimination impairments when lures are novel, but not when they are familiar. This observation suggests that other brain structures support discrimination abilities as stimuli are learned. The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is critical for retrieval of remote events and executive functions, such as working memory, and is also particularly vulnerable to dysfunction in aging. Importantly, the medial PFC is reciprocally connected to the perirhinal cortex and neuron firing in this region coordinates communication between lateral entorhinal and perirhinal cortices to presumably modulate hippocampal activity. This anatomical organization and function of the medial PFC suggests that it contributes to mnemonic discrimination; however, this notion has not been empirically tested. In the current study, rats were trained on a LEGO object-based mnemonic similarity task adapted for rodents, and surgically implanted with guide cannulae targeting prelimbic and infralimbic regions of the medial PFC. Prior to mnemonic discrimination tests, rats received PFC infusions of the GABAA agonist muscimol. Analyses of expression of the neuronal activity-dependent immediate-early gene Arc in medial PFC and adjacent cortical regions confirmed muscimol infusions led to neuronal inactivation in the infralimbic and prelimbic cortices. Moreover, muscimol infusions in PFC impaired mnemonic discrimination performance relative to the vehicle control across all testing blocks when lures shared 50–90% feature overlap with the target. Thus, in contrast hippocampal infusions, PFC inactivation impaired target-lure discrimination regardless of the novelty or familiarity of the lures. These findings indicate the PFC plays a critical role in mnemonic similarity task performance, but the time course of PFC involvement is dissociable from that of the hippocampus.

Keywords: aging, infralimbic cortex, medial temporal lobe, muscimol, object recognition, prelimbic cortex

1 |. INTRODUCTION

The ability to discriminate between stimuli that share features declines in advanced age. Specifically, older adults are impaired at distinguishing similar lures from previously seen target stimuli relative to young adults, as assessed by the “mnemonic similarity task” (Camfield, Fontana, Wesnes, Mills, & Croft, 2018; Holden, Toner, Pirogovsky, Kirwan, & Gilbert, 2013; Huffman & Stark, 2017; Reagh et al., 2016; Stark, Kirwan, & Stark, 2019; Stark, Stevenson, Wu, Rutledge, & Stark, 2015; Stark, Yassa, Lacy, & Stark, 2013; Toner, Pirogovsky, Kirwan, & Gilbert, 2009; Trelle et al., 2020; Trelle, Henson, Green, & Simons, 2017). Mnemonic similarity task deficits in advanced age have been reported for older adults who are able to perform on par with young adults in standardized neuropsychological test batteries (Reagh et al., 2014; Reagh et al., 2016; Stark et al., 2013). These data suggest that tasks assessing stimulus discrimination abilities are particularly sensitive in detecting cognitive decline and could provide a behavioral read-out of underlying neural dysfunction that accompanies aging. In support of this idea, human neuroimaging studies have shown that age-related mnemonic discrimination impairments are associated with reduced integrity of white matter afferents to the hippocampus (Bennett, Huffman, & Stark, 2015; Bennett & Stark, 2016; Yassa, Muftuler, & Stark, 2010) and altered task-related activation in the perirhinal cortex (Berron et al., 2018; Ryan et al., 2012), lateral entorhinal cortex (Bakker, Albert, Krauss, Speck, & Gallagher, 2015; Berron et al., 2019; Reagh et al., 2018), and hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG)/CA3 (Bakker et al., 2012, 2015; Doxey & Kirwan, 2015; Reagh et al., 2018; Yassa, Lacy, et al., 2011; Yassa, Mattfeld, et al., 2011). These data echo prior findings that cortical inputs to the hippocampus are particularly vulnerable in aging (Barnes & McNaughton, 1980; Geinisman, de Toledo-Morrell, Morrell, Persina, & Rossi, 1992; Hyman, Van Hoesen, Damasio, & Barnes, 1984).

Behavioral mnemonic discrimination impairments in late adulthood are also observed in animal models. Aged rats and monkeys, like humans, are prone to false recognition and are more likely to respond as if novel objects are familiar (Burke, Wallace, Nematollahi, Uprety, & Barnes, 2010). This false recognition is particularly evident when the objects share features with previously experienced stimuli (Burke et al., 2011). Furthermore, in an object discrimination task designed to directly parallel human mnemonic similarity tasks (Stark et al., 2019), aged rats were selectively impaired in distinguishing similar objects relative to young adult rats (Johnson et al., 2017). Importantly, discrimination of objects without common features is comparable between young and old animals (Burke et al., 2011; Hernandez et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2017). Given CA3/DG activity has been consistently linked to mnemonic discrimination performance in both young and older adults (Bakker, Kirwan, Miller, & Stark, 2008; Doxey & Kirwan, 2015; Kirwan & Stark, 2007; Lacy, Yassa, et al., 2011; Motley & Kirwan, 2012; Reagh et al., 2018; Reagh & Yassa, 2014; Yassa, Lacy, et al., 2011), we recently tested the requirement of intact neural activity in these hippocampal regions for distinguishing similar objects in rats (Johnson et al., 2018). While disrupting activity within CA3/DG impaired discrimination performance in young adults, this effect was contingent on prior task experience. Specifically, infusions of the GABAA agonist muscimol in CA3/DG impaired discrimination in a first block of tests when lure objects were novel, but not on subsequent second and third blocks of tests as lures became familiar (Johnson et al., 2018). In contrast, interference with perforant path input to the hippocampus impaired mnemonic discrimination performance across multiple tests (Burke, Turner, et al., 2018). These findings raised two points of interest. First, in agreement with data from humans, intact cortical input to the hippocampus is important for mnemonic discrimination performance. Second, as experience with procedural or contextual aspects of a task accrues, extra-hippocampal regions appear to compensate for altered activity within the hippocampal circuit.

It is well established that prefrontal cortical (PFC) activity and connectivity with hippocampal and parahippocampal circuits supports memory-guided behavior across the lifespan (Barry & Maguire, 2019; Eichenbaum, 2017; Gaffan, 2002; Maillet & Rajah, 2013; Takehara-Nishiuchi, 2020). It is therefore possible that when hippocampal activity is disrupted, prefrontal-perirhinal or -entorhinal circuits guide mnemonic discrimination behavior. In support of this interpretation, PFC neuron spiking increases coordinated activity between perirhinal and lateral entorhinal cortices (Paz, Bauer, & Paré, 2007), which could facilitate cortical-hippocampal interactions. Conversely, blocking prefrontal neural activity or prefrontal-perirhinal communication impairs the ability to retrieve previously learned hippocampal-dependent object-place associations (Hernandez et al., 2017) and odor sequence memories (Jayachandran et al., 2019). Activation of prefrontal neuronal ensembles that receive synaptic input from the perirhinal cortex is attenuated in aged rats when tested in a hippocampal-dependent object-place association task (Hernandez et al., 2018). Further, rats with hippocampal lesions exhibit compensatory prefrontal activity that is associated with intact expression of a learned, hippocampal-dependent, contextual fear association (Zelikowsky et al., 2013). These data point to an important role for prefrontal cortices in modulating neural activity during mnemonic discrimination, yet, to date, few studies have examined frontal cortical contributions to this cognitive function (Pidgeon & Morcom, 2016; Wais, Montgomery, Stark, & Gazzaley, 2018).

The current study investigated how PFC activity contributes to the discrimination of similar objects in a rodent mnemonic similarity task (Johnson et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2018). Rats were trained on task procedures, then implanted with guide cannulae targeting prelimbic and infralimbic regions of the medial prefrontal cortex. These regions were selected because of their indirect anatomical connectivity with the hippocampus through the perirhinal and entorhinal cortices (Agster & Burwell, 2009; Burwell & Amaral, 1998; Condé, Maire-Lepoivre, Audinat, & Crépel, 1995; Eichenbaum, 2017; Hoover & Vertes, 2007; Hwang, Willis, & Burwell, 2018; Jay & Witter, 1991; Sesack, Deutch, Roth, & Bunney, 1989; Vertes, 2004). To test the prediction that PFC activity is necessary for task performance, rats received infusions of the GABAA agonist muscimol prior to mnemonic discrimination testing. We have previously shown that muscimol infusions at these coordinates and dose block expression of the neuronal activity-dependent immediate early gene Arc (Hernandez et al., 2017). This finding was replicated in the current study, confirming efficacy of PFC inactivation through GABAA agonism. Prefrontal muscimol infusions impaired mnemonic discrimination of a target object from both distinct and similar lure objects, with the effect most pronounced for similar lures. Further, in contrast to effects of hippocampal muscimol infusions (Johnson et al., 2018), disrupting prefrontal activity impaired performance irrespective of prior task experience.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Subjects

Seven young adult Fischer 344 × Brown Norway F1 hybrid rats (NIA, Taconic; 4–6 m at arrival) were used as subjects and completed the study in two cohorts (cohort 1:3 males, cohort 2:2 males, 2 females). Note that, 2 female rats were included in the study, which did not provide adequate power to test for potential sex differences. The inclusion of additional female rats was not possible due to the lack of availability of females for this rat strain from the NIA during the time that these experiments were conducted. Rats were single-housed in standard Plexiglas cages and maintained on a 12-hr reversed light/dark cycle with lights off at 8:00 a.m. Experimental manipulations took place during the dark portion of the cycle, 5–7 days per week at the same time each day. Rats were given 7 days to acclimate to the housing facility upon arrival and were handled for a minimum of 4 days prior to beginning experiments. Rats were placed on a restricted feeding protocol after this period of acclimation, receiving 20 ± 5 g moist chow (~39 kcal; Teklad LM-485, Harlan Labs) daily after completing behavioral training. Water was provided ad libitum. Behavioral shaping began once rats reached 85% of their initial baseline body weights, which provided appetitive motivation to perform the tasks. All procedures were in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Florida.

2.2 |. Habituation and procedural training

Procedures for habituation and procedural training were similar to those previously described (Johnson et al., 2017, 2018). Rats were habituated to eating small pieces of Froot Loop cereal (Kellogg’s; Battle Creek, MI) or marshmallows (Medley Hills Farm, Medina, OH), which served as food rewards throughout experiments, by providing pieces with daily chow for 1–3 days. Rats were then habituated to the task apparatus by encouraging foraging for scattered food reward pieces for 1–3 days. Tasks were carried out in a U-shaped maze built on a low table (surface 148 cm × 76 cm) out of plastic building bricks (DUPLO®, LEGO®, Enfield, CT; Figure 1a), similar to mazes previously used in our laboratory (Burke, Turner, et al., 2018; Hernandez et al., 2015, 2017; Hernandez et al., 2018; Johnson et al., 2017, 2018; Kreher et al., 2019; Maurer et al., 2017). Rats were trained in daily sessions to alternate between a designated start area in one arm and choice platform in the opposite arm (Figure 1a) by providing food reward in each location. After reaching a criterion of 32 alternations within a single daily session of 20 min or less, rats were trained on forced-choice continuous object discrimination task procedures with a pair of “standard” unrelated objects (0% feature overlap; Figure 1b). Rats received additional training with a pair of perceptually distinct LEGO objects (38% feature overlap; Figure 1b). Detailed description of feature overlap calculations is provided in a previous publication from our lab (Johnson et al., 2017). For each object pair, one object served as the target (S+), placed over the baited food well, while the alternate object was a lure (S−), placed over the empty food well. Training proceeded in daily sessions of 32 trials. In each trial, rats exited the start area, traversed the maze to the choice platform, and displaced one of the two objects covering the food wells. If the target (S+) was selected, rats consumed the reward and returned to the start area to receive a second reward. If the lure (S−) was selected, both objects and the food reward were quickly removed from the choice platform and the rat did not receive a reward in the start area. The side of the baited food well on the choice platform was pseudo-randomized across trials to provide an equal number of left- and right-well trials over the course of each session. For each training object pair, the object serving as the target was counterbalanced across rats. Training was considered complete when rats reached a criterion of ≥26 correct responses out of 32 trials (≥81.3%) within a session for two consecutive days.

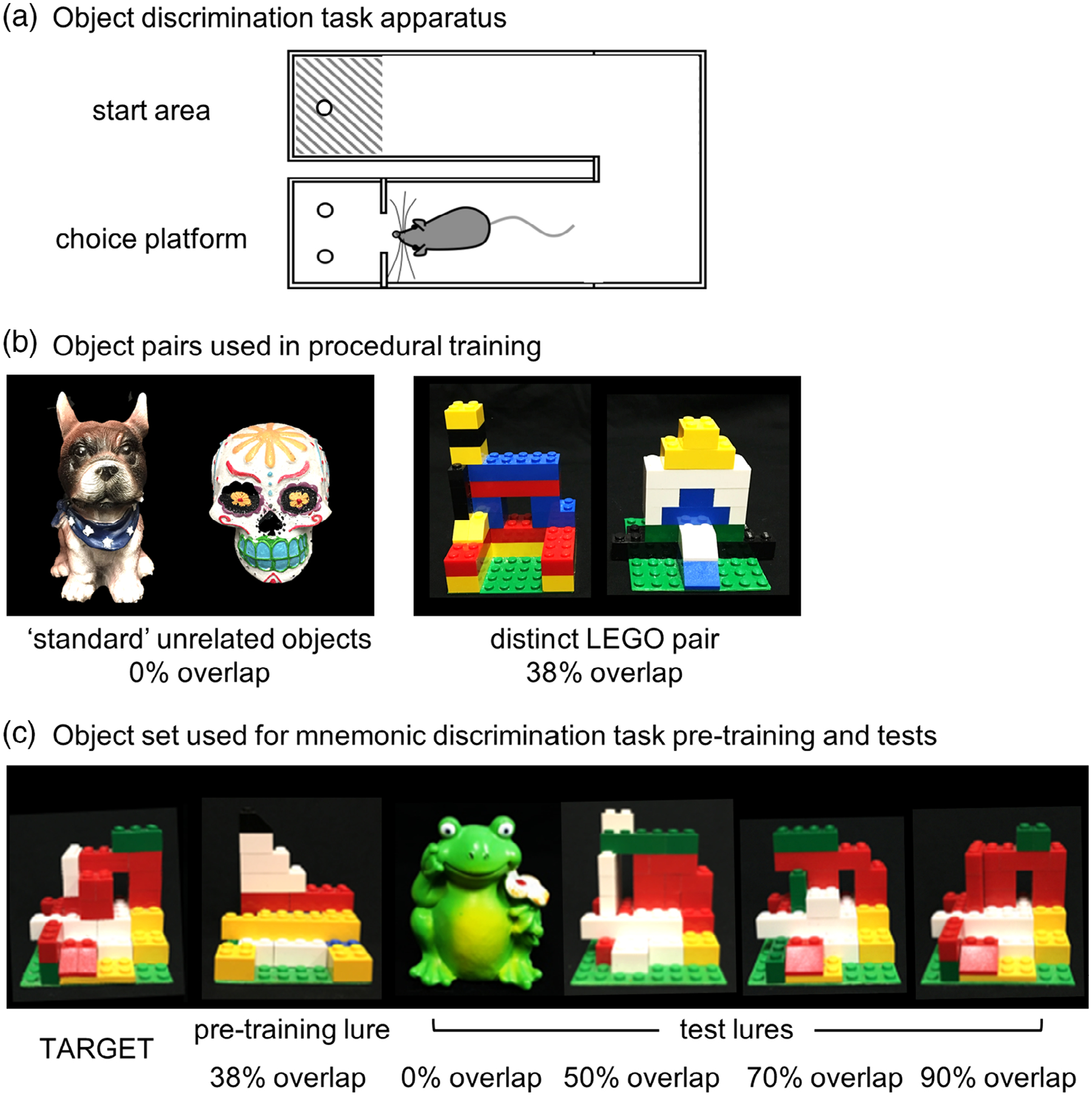

FIGURE 1.

Rat mnemonic similarity task apparatus. (a) U-shaped maze used for the object-based mnemonic discrimination task. Rats were placed in the start area at the beginning of a session, then traversed to the choice platform where object stimuli were placed over food wells. After response selection, rats returned to the start area to initiate the next trial. Walls 25–30 cm in height surround the choice platform to prevent rats from visualizing objects as they are placed by the experimenter. (b) Object stimulus pairs used for procedural training. Rats were first trained with “standard” unrelated junk objects that share 0% visible feature overlap, then with perceptually distinct LEGO objects that share 38% feature overlap. For each pair, one object served as the target (S+) and the alternate object as a lure (S−). The object serving as the target for each pair was counterbalanced across rats. (c) Object stimuli used for the rat mnemonic similarity task. For mnemonic discrimination tests, one object always served as the target (S+) for all rats (left; TARGET). Rats were pretrained to identify this target with a single distinct LEGO lure that shared 38% feature overlap (pretraining lure). Rats were tested with four lure objects that ranged in similarity to the target: a distinct unrelated object with 0% feature overlap, and three LEGO lures that shared 50, 70, and 90% feature overlap. For a detailed description of feature overlap calculations see Johnson et al., 2017

2.3 |. Surgery

After procedural training, rats were implanted with bilateral guide cannulae targeting the prelimbic and infralimbic cortex. Isoflurane anesthesia was induced at 5%, then maintained at 1–3% (Isothesia, Henry Schein, Dublin, OH). A longitudinal incision was made to expose Bregma and Lambda and the skull surface was cleaned. After confirming flat skull position in the stereotaxic apparatus, four stainless steel bone screws (#000–120, 1/8”; Antrin Miniature Specialties, Fallbrook, CA) were placed to anchor the head cap, two posterior to the coronal suture and two anterior to the lambdoid suture. Custom bilateral stainless steel guide cannulae (C252G DBL, 22G; P1 Technologies, Roanoke, VA) were positioned at AP +3.6 mm, ML ±0.9 mm, and DV −3.8 mm relative to Bregma at skull surface. Cannulae tips were positioned 1 mm dorsal to infusion sites, as microinjectors protruded 1 mm below this coordinate. Cannulae were secured to the skull and anchor screws with dental cement (Teets, Patterson Dental, Tampa, FL). Dust caps (303DC, P1 Technologies) protected cannulae from contamination. NSAIDS (Metacam, 1–2 mg/kg s.c., Boehringer Ingelheim, Vetmedica Inc., St. Joseph, MO) were administered for analgesia pre- and postop. Rats were given a minimum recovery period of 1 week before resuming behavioral experiments.

2.4 |. Mnemonic discrimination task

Following recovery, rats were pretrained for mnemonic discrimination tests with a new pair of LEGO objects (Figure 1c). One object would serve as the target (S+) throughout testing and the other was a perceptually distinct lure (pretraining lure; S−) sharing 38% feature overlap, comparable to overlap of the distinct LEGO pair used in procedural training (Figure 1b). After reaching criterion of ≥81.3% correct responses on two consecutive training sessions, rats were given 2 days off before their first mnemonic discrimination test. Tests were carried out as previously described with the learned target and a set of lures that shared 0–90% feature overlap (Figure 1c; Burke, Turner, et al., 2018; Johnson et al., 2017, 2018). Each session consisted of 50 trials: 10 with an entirely distinct standard lure (frog figurine, 0% overlap), 10 with each of 3 perceptually similar LEGO lure objects, sharing 50, 70, and 90% feature overlap, and 10 with an identical copy of the target object. Trials with the copy of the target were included as a control condition, to verify rats were not using odor cues from the maze, objects, or food reward to guide response selection. Sessions were recorded with a camera mounted directly above the choice platform. Response latencies and response selection behavior were scored offline from recordings with custom software (Collector/Minion; Burke/Maurer Labs, Gainesville, FL).

2.5 |. Intracerebral infusions

Tests proceeded every 3 days to avoid over-familiarization with lure objects and provide a wash-out period between drug infusions, as in prior studies (Bañuelos et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2018; McQuail et al., 2016). Order of infusion conditions was pseudo-randomized across 3 test blocks in a Latin squares design, such that each rat received both a vehicle and a muscimol infusion within each test block. The GABAA receptor agonist muscimol (1 mg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; dissolved in 0.9% sterile physiological saline) or vehicle (0.9% sterile physiological saline) were infused bilaterally to the prelimbic/infralimbic cortex(0.5 μl per hemisphere, 0.1 μl/min) 30 min prior to each test. Internal bilateral stainless steel microinjectors (C232I, 28G, P1 Technologies) protruding 1 mm below implanted guides were connected via polyethylene tubing (PE50, P1 Technologies) to 10 μl syringes (Hamilton, Franklin, MA) mounted in a microinfusion pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). Tubing was backfilled with sterile water. A 1-μl bubble was aspirated to create a barrier between backfill and infusate, and permit confirmation by visual inspection that the correct volume of infusate had been delivered. Microinjectors were left in place for 2 min after the infusion to allow dispersion of the drug. Rats were returned to the home cage for 30 min prior to beginning behavioral testing.

2.6 |. Verification of cannulae placements and effects of muscimol

Positions of guide cannulae tips and effects of muscimol infusions on neuronal activity were verified at the conclusion of experiments, as in previous studies (Hernandez et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2018). Briefly, effects of muscimol within the diffusion radius of the drug were assessed by visualizing cells expressing mRNA of the immediate-early gene Arc with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). One week after completing infusions and mnemonic discrimination test blocks, rats received a bilateral intracerebral muscimol infusion (0.5 μl per hemisphere, 1 mg/ml) and were returned to their home cages for 30 min. Rats then performed a 10-min object discrimination epoch, were transferred to a glass bell jar for deep anesthesia with isoflurane, and were euthanized by rapid decapitation. In this behavioral epoch, the target object and lure object sharing 70% feature overlap (Figure 1c) were used as stimuli on all trials. Rats completed as many trials as possible within 10 min; this ranged from 16 to 28 trials (mean = 23, SD = 4.73). Brains were extracted and snap-frozen in chilled 2-methyl butane (Acros Organics, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Tissue blocks were sectioned (20 μm) on a cryostat (Microm HM550, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), thaw-mounted on Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific) and stored at −80°C in sealed slide boxes. One rat prematurely lost their head cap and had to be euthanized; this rat was excluded from neural analyses of muscimol effects. Instead, this rat was perfused and cannulae placements were verified by imaging 40 μm sections with fluorescence microscopy (Keyence, Itasca, IL).

FISH for Arc mRNA was carried out as previously described (Hernandez et al., 2017; Hernandez et al., 2018; Johnson et al., 2018; Maurer et al., 2017). Briefly, digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled riboprobes were generated with a commercial transcription kit (Riboprobe System, P1440, Promega, San Luis Obispo, CA) and DIG RNA labeling mix (Roche REF# 11277073910, MilliporeSigma, St. Louis, MO) from a 3.0 kb Arc cDNA template (provided by Dr. A. Vazdarjanova, Augusta University, Augusta, GA). Slides were hybridized and incubated with anti-digoxigenin-POD (Roche REF# 11207733910, MilliporeSigma). Labeled transcripts were visualized with Cy3 (TSA Cyanine 3 System, NEL744A001KT, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) and sections were counter-stained with DAPI. Low magnification stitched images were collected by fluorescence microscopy (Keyence) with a 2× objective. Cannulae placements were verified from these flyover images. Placements of implanted cannulae for all rats are shown in Figure 2a. In two slides adjacent to cannulae tracks, approximately 3.6–4.6 mm anterior to Bregma, high magnification z-stacks were captured with a 40× objective from prelimbic (PrL) and infralimbic (IL), anterior cingulate (Cg1), orbitofrontal (OFC), and motor (M1) cortices (Figure 2b). Proportions of neurons with Arc mRNA labeling in each region were determined by manually counting Arc-positive DAPI-labeled neuronal nuclei with ImageJ software and a custom plug-in, as previously described (Hernandez et al., 2017, 2018; Johnson et al., 2018; Maurer et al., 2017).

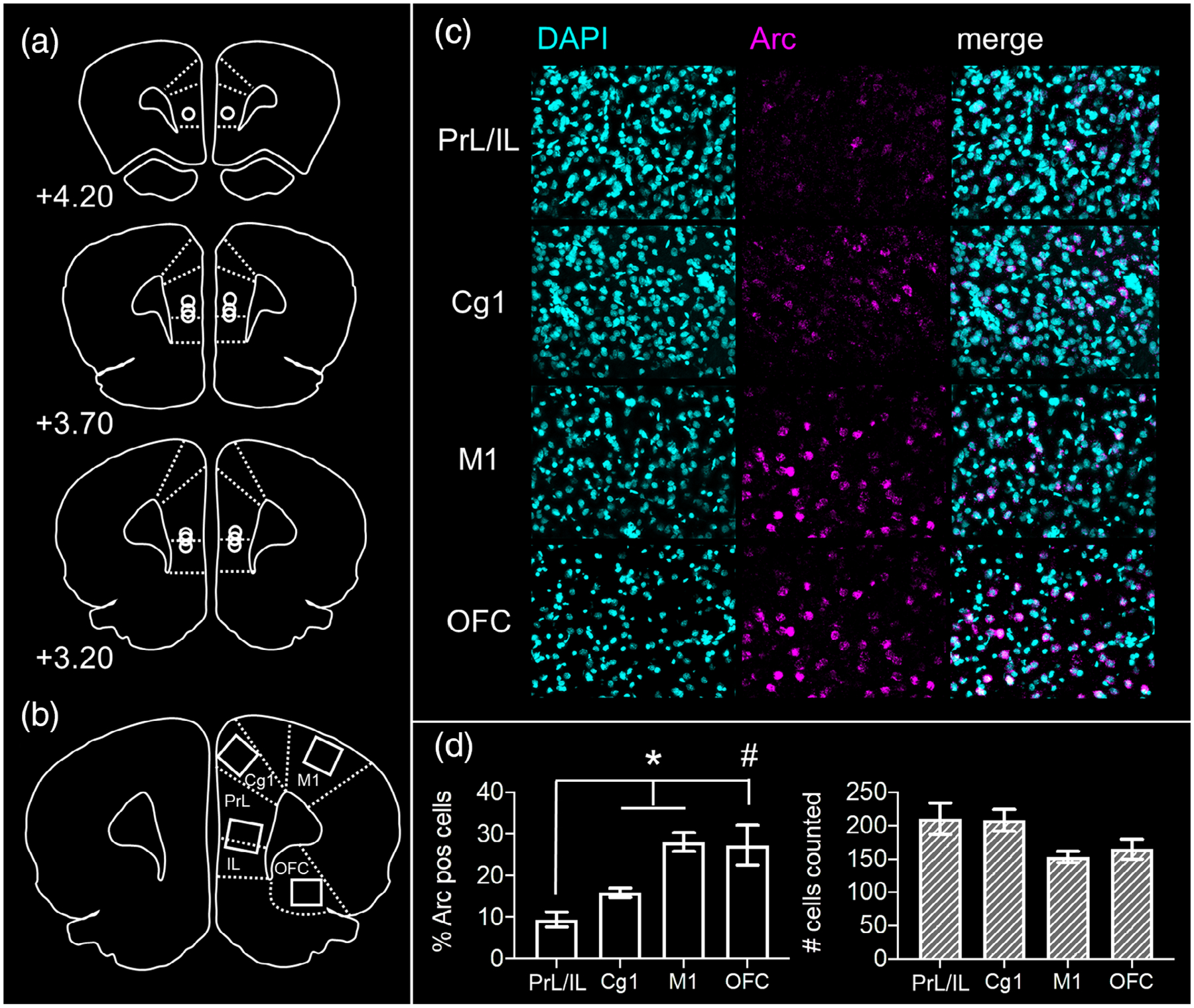

FIGURE 2.

Verification of guide cannulae positions and neural effects of prefrontal cortical muscimol infusions. (a) Placements of microinjector tips are shown on representative prefrontal cortical sections for each rat from the study, AP +3.2 to 4.2 mm relative to Bregma. (b) Regions of interest sampled from tissue sections adjacent to guide cannulae tracks. High magnification z-stacks were captured from prelimbic (PrL), infralimbic (IL), anterior cingulate (Cg1), orbitofrontal (OFC), and motor (M1) cortices. (c) Representative z-stacks from each region of interest labeled with the nuclear marker DAPI (cyan) and for mRNA of the neuronal activity-dependent immediate early gene Arc (magenta). (d) Proportion of neurons expressing Arc mRNA (left panel) and total number of neurons counted for the analysis (right panel) are shown for each region of interest. Following prefrontal muscimol infusions, the proportion of Arc mRNA-positive neurons in PrL/IL was significantly less than that present in Cg1 (contrasts; p = .016) and M1 (p = .003). The same trend was observed for PrL/IL relative to neurons in OFC (p = .059). Total number of cells counted did not differ across regions (main effect region; p = .095). * p <.05, # p <.10

2.7 |. Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS) v25 for Mac OSX. Behavioral variables were analyzed with repeated measures analysis of variance (RM ANOVA), with test block, infusion condition, and lure object as within subjects factors, and within subjects or simple contrasts for post hoc analyses. When relevant, performance was compared to chance levels (i.e., 50% correct responses) with one-sample t-tests. Choice of statistical test was dictated by assumptions of normality, assessed with Shapiro–Wilk tests, and homogeneity of variances, assessed with Levene’s tests. Loss of several behavioral video recordings due to technical issues resulted in missing values for response latency data. These data were treated as independent samples by infusion condition and test block and were analyzed with nonparametric Mann Whitney U tests and Kruskal Wallis tests. p-values less than .05 were considered statistically significant, with Bonferroni corrections applied in cases where multiple comparisons were carried out.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Verification of cannulae placements and neural effects of muscimol

Cannulae positions for all rats were located within the prelimbic and infralimbic (PrL/IL) cortex in the region spanning 3.20–4.20 mm anterior to Bregma (Figure 2a). To confirm muscimol had the intended effect of inhibiting neural activity in PrL/IL, proportions of neurons expressing mRNA of the immediate-early gene Arc were determined from these regions (PrL/IL) and adjacent regions within the same coronal section, approximately 0.5 mm anterior to the cannulae placement (Cg1, M1, OFC; Figure 2b). Representative z-stacks from each region of interest are shown in Figure 2c. Percentages of Arc-positive neurons and total number of cells sampled in each region are shown in Figure 2d. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of region (F(3,12) = 6.575, p = .007). Within subjects contrasts confirmed fewer Arc-positive neurons present in PrL/IL relative to adjacent cingulate cortex (Cg1; F(1,4) = 16.324, p = .016) and motor cortex (M1; F(1,4) = 44.473, p = .003). The difference in percent Arc-positive neurons in PrL/IL relative to orbitofrontal cortex was not statistically significant but followed the same trend (OFC; F(1,4) = 6.857, p = .059). The total number of cells counted did not differ across cortical regions (RM ANOVA main effect of region, F(3,12) = 2.668, p = .095).

3.2 |. Procedural training

Figure 3 shows the number of incorrect trials completed by rats prior to reaching criterion in procedural training and pretraining with the target object used in the mnemonic discrimination task. Rats differed in amount of training required to reach criterion performance of >81% correct responses across object pairs (RM ANOVA main effect of pair, F(2,10) = 17.138, p = .001). Follow-up contrasts confirmed this effect was attributable to a greater number of trials completed in learning to distinguish the distinct LEGO object pair used in procedural training (distinct LEGO pair vs. standard objects, p = .01; distinct LEGO pair vs. pretraining LEGO objects, p = .002). The fact that all rats learned to accurately discriminate the mnemonic discrimination target object and distinct pretraining lure within a comparable number of trials as the first standard object pair (contrast, p = .340) confirms surgical implantation of PFC cannulae did not interfere with existing procedural knowledge of the discrimination task, nor impede rats’ abilities to learn the identity of a new target object.

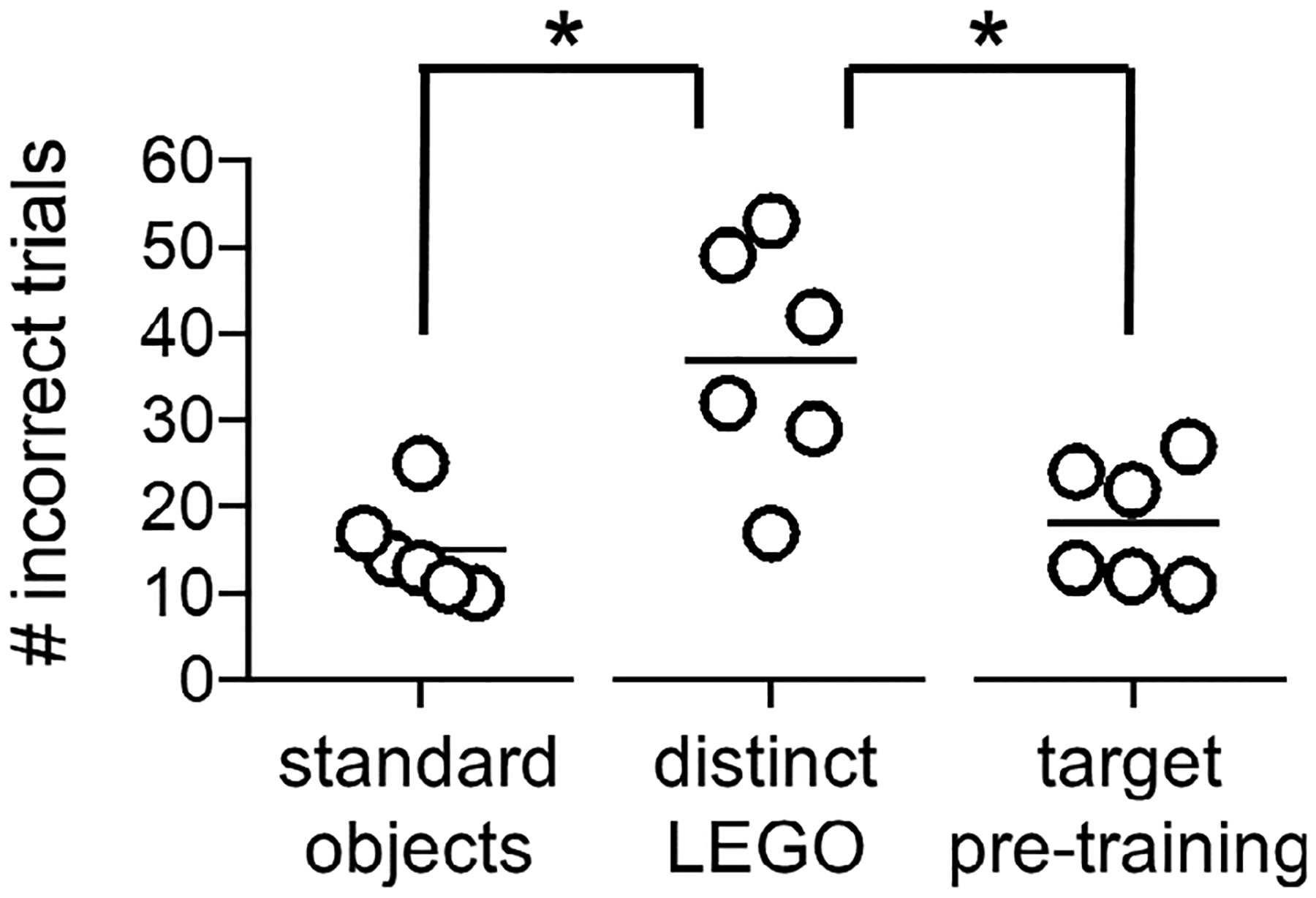

FIGURE 3.

Procedural training data. Total number of incorrect trials completed prior to reaching a criterion performance level of ≥26/32 (≥ 81%) correct responses on each of two consecutive daily object discrimination training sessions. Data are shown for the standard unrelated object pair (0% feature overlap) and distinct LEGO pair (38% feature overlap) used in procedural training, and the LEGO target object and distinct lure (38% feature overlap) used after cannulae implantation for mnemonic similarity task pretraining. Total number of incorrect trials differed across object pairs (main effect object pair; p = .001). Rats required a greater number of trials to learn the distinct LEGO discrimination during procedural training than the standard object discrimination (contrasts; p = .01). However, rats then took fewer trials to learn the target and distinct LEGO lure in mnemonic discrimination pretraining after cannulae implantation (p = .002), confirming surgical implantation of guide cannulae did not interfere with rats’ abilities to learn a new lure or draw on procedural knowledge acquired preoperatively

3.3 |. PFC muscimol impairs mnemonic discrimination performance

Muscimol or vehicle infusions were administered prior to mnemonic discrimination tests across three blocks in a Latin squares design (Figure 4a). Performance was first analyzed with infusion condition, test block, and lure object as within subjects factors. As in prior studies (Johnson et al., 2017, 2018), performance on control trials in which rats were presented with two identical copies of the target object (i.e., 100% overlap condition) did not differ across test blocks (RM ANOVA main effect of block; F(2,12) = 1.032, p = .386). Mean performance on these trials by block ranged from 47.1 to 54.3% correct responses (SD = 5.67–12.15) and did not differ from chance in blocks 1 and 2 (one-sample t-tests with hypothetical mean of 50% correct trials; block 1, p = .231, block 2, p = .766). With alpha levels corrected for multiple comparisons (.05/3 = .017), performance on these trials in block 3 also did not differ from chance (p = .045). Moreover, there was not a significant effect of infusion condition on performance during the identical trials (T[6] = 0.23, p = .83). Data from these trials were therefore excluded from subsequent analyses.

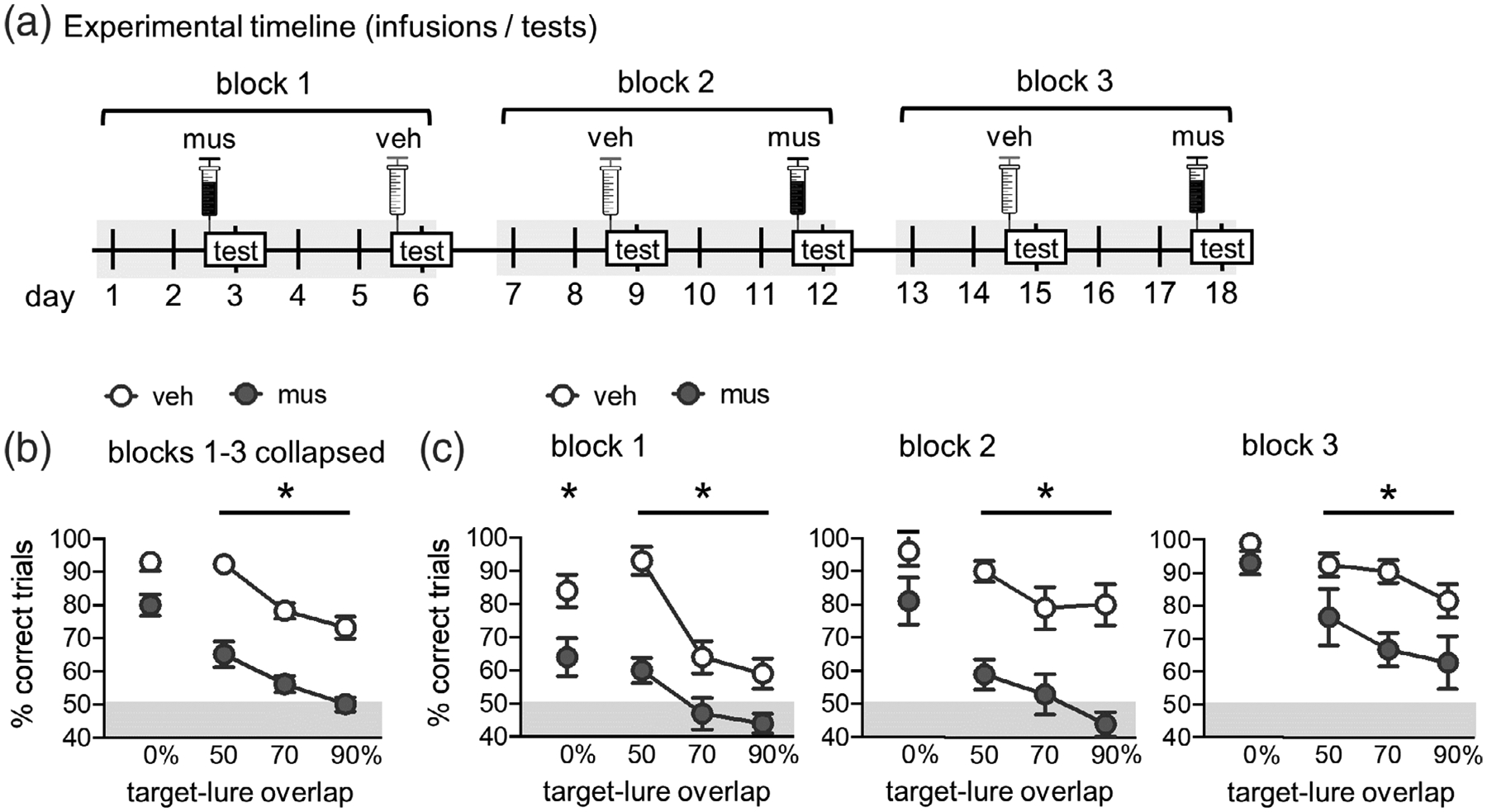

FIGURE 4.

Effects of prefrontal cortical inactivation on mnemonic similarity task performance. (a) Experimental timeline. Muscimol (mus) or vehicle (veh) infusions were given prior to mnemonic discrimination tests across three blocks in a Latin squares design. Infusions/tests took place every 3 days to allow a sufficient period for drug wash-out. Order of infusion condition within each test block was counterbalanced across rats. (b) Mnemonic discrimination performance following vehicle (veh) and muscimol (mus) infusions, collapsed across test Blocks 1–3. Performance is shown as mean percent (%) correct trials for trial types with each level of target-lure overlap (0, 50, 70, and 90%). Prefrontal cortical muscimol infusions impaired mnemonic discrimination performance across test blocks (main effect infusion; p = <.001) but effects differed based on target-lure overlap (interaction infusion × lure; p = .019). Follow-up contrasts showed muscimol impaired discrimination on trials with LEGO lure objects with overlap of 50% (p <.001), 70% (p <.001), and 90% (p = .001). (c) Mnemonic discrimination performance following vehicle (veh) or muscimol (mus) infusions on each of test blocks 1–3. As in (b), performance is shown as mean % correct trials for each level of target-lure overlap. Prefrontal cortical muscimol infusions impaired discrimination in each test block (main effects infusion; block 1, p = .007, block 2, p = .001, block 3, p = .012). For block 1, muscimol impaired performance across all lure stimuli, but this infusion effect was not significant on subsequent blocks. Unlike the 0% overlap condition, in which performance following musimol improved across testing blocks, performance on trials with similar lures (50, 70, and 90% overlap) did not improve (simple effects; p’s >.106). In contrast, after vehicle infusions, performance on trials with lures sharing overlap of 70 and 90% significantly improved (p’s <.01). *p <.05

Percent correct responses on the mnemonic discrimination task collapsed across the three test blocks is shown in Figure 4b. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed that, overall, PFC muscimol infusions impaired rats’ performance on the task (main effect of infusion condition; F(1,6) = 76.364, p <.0001). Consistent with previous studies (Johnson et al., 2017, 2018), performance also differed based on the similarity of lure objects to the target object (main effect of lure; F(3,18) = 34.720, p <.0001). A significant infusion condition × lure object interaction (F(3,18) = 4.294, p = .019) suggested that the degree to which muscimol impaired performance differed based on target-lure similarity. A follow-up analysis of within subjects contrasts showed, relative to vehicle, muscimol impaired rats’ abilities to distinguish the target from similar lure objects (i.e., sharing 50% or more visible feature overlap; 50% overlap, p <.0001, 70% overlap, p <.0001, 90% overlap, p = .001). After correcting alpha levels for multiple comparisons (.05/4 = .013), the difference in performance on trials with the distinct standard object lure (0% feature overlap) was not statistically significant (p = .017).

Percent correct responses on tests of blocks 1–3 following vehicle versus muscimol infusions are shown in Figure 4c. In our previous studies, we have found the effects of hippocampal muscimol infusions on mnemonic discrimination performance can differ as rats gain experience with the task across test blocks (Johnson et al., 2018). A repeated measures ANOVA with test block, infusion condition, and lure object as within subject factors was performed to determine if this was also the case for PFC muscimol infusions. This analysis revealed significant main effects of block (F(2,12) = 12.830, p = .001), infusion (F(1,6) = 76.364, p <.0001), and lure overlap (F(3,18) = 34.720, p <.0001), a significant infusion × lure overlap interaction (F(3,18) = 4.294, p = .019), and a significant three-way interaction (F(6,36) = 2.565, p = .036). Interactions of block × infusion (F(2,12) = .348, p = .713) and block × lure (F(6,36) = 1.679, p = .155) were not statistically significant.

To clarify effects of task experience, separate repeated measures ANOVAs were run on data from each test block, with lure object and infusion condition entered as within subjects factors. As in prior studies (Burke, Gaynor, et al., 2018; Burke, Turner, et al., 2018; Johnson et al., 2017, 2018), significant main effects of lure were observed across all test blocks (F’s >11.663, p’s <.0001) confirming that performance across three blocks of discrimination tests remains contingent on target-lure overlap. Significant main effects of prefrontal infusion condition were detected in block 1 (F(1,6) = 16.241, p = .007), block 2 (F(1,6) = 43.070, p = .001), and block 3 (F(1,6) = 12.590, p = .012). Significant lure × infusion condition interactions were observed in block 1 (F(3,18) = 4.100, p = .022) and block 3 (F(3,18) = 5.210, p = .009), but not block 2 (F(3,18) = 1.957, p = .157). Additional repeated measures ANOVAs with lure object and test block as within subjects factors, holding infusion condition constant, showed significant main effects of lure (F’s >22.041, p’s <.0001) and of block (vehicle, F(2,12) = 8.605, p = .005; muscimol, F(2,12) = 4.702, p = .031). However, a significant lure × block interaction was only observed on tests following vehicle infusions (F(6,36) = 3.022, p = .017), not following muscimol infusions (F(6,36) = 1.251, p = .304). This suggests that the performance improvements across blocks were only evident in the vehicle condition.

Simple effects analyses showed performance on trials with the distinct object lure (0% overlap) improved across blocks, for vehicle (F(2,12) = 6.326, p = .013) and for muscimol infusion conditions (F(2,12) = 6.423, p = .013). Comparably, after vehicle infusions, performance on trials with similar lures improved across test blocks. This was the case for trials with 70% overlap (F(2,12) = 6.923, p = .01) and 90% overlap (F(2,12) = 6.235, p = .014), but not 50% overlap (F(2,12) = .673, p = .528), because rats’ performance remained high on these trials across blocks. After muscimol infusions, performance on trials with similar lures did not improve across blocks. Simple effects did not show statistically significant differences for trials with 50% overlap (F(2,12) = 1.864, p = .197), 70% overlap (F(2,12) = 1.511, p = .260), or 90% overlap (F(2,12) = 2.717, p = .106).

3.4 |. PFC muscimol causes rats to default to a side-biased strategy

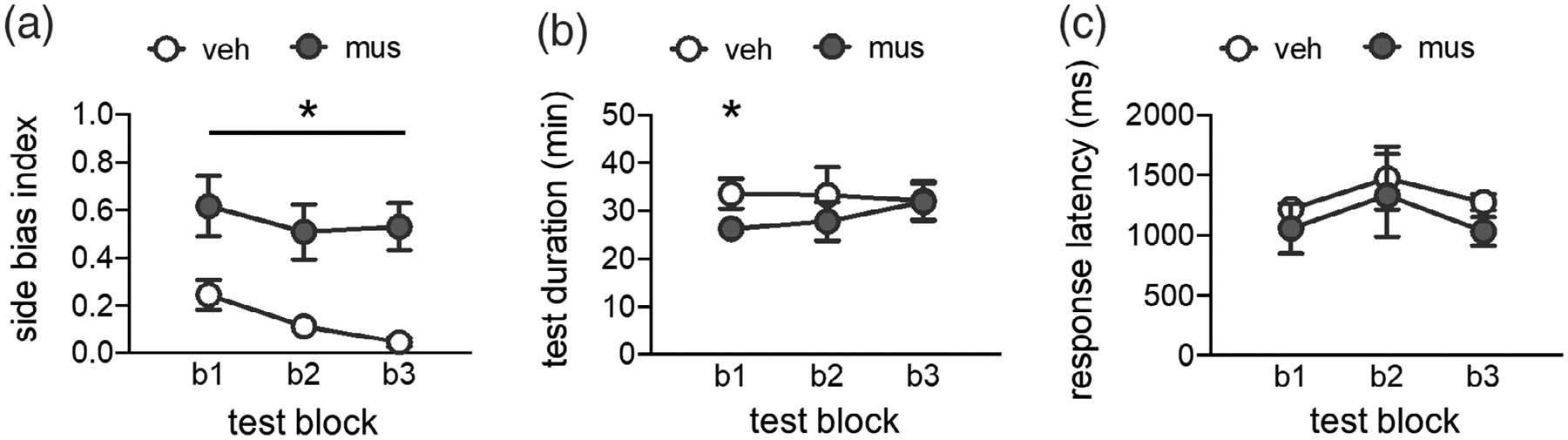

\Previous studies (Burke, Turner, et al., 2018; Hernandez et al., 2015, 2017; Johnson et al., 2017, 2018) have found that rats default to selecting an object on a particular side (regardless of features) when learning forced-choice discrimination tasks. This side-biased strategy is particularly prominent in aged rats (Hernandez et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2017) and young adult rats in which connectivity across perirhinal cortex, hippocampus, and/or the prefrontal cortex is experimentally disrupted (Burke, Turner, et al., 2018; Hernandez et al., 2017; Jo & Lee, 2010a, 2010b; Johnson et al., 2018; Lee & Solivan, 2008). To determine if this was the case in the current study, side bias indices were calculated as the absolute value of (total number of left well responses − total number of right well responses)/total number trials. Figure 5a shows these values collapsed across trial types for each of the tests given in blocks 1–3. As in prior studies, muscimol caused rats to have a greater side bias index, relative to vehicle (RM ANOVA, main effect of infusion condition, F(1,6) = 24.449, p = .003). The side bias index did not vary across tests (main effect of block, F(2,12) = 2.190, p = .155; infusion × block interaction, F(2,12) = .013, p = .702). However, within subjects contrasts showed that following vehicle infusions, side bias decreased from block 1 to block 3 (F(1,6) = 14.583, p = .009), while after muscimol infusions, side bias remained the same from block 1 to block 3 (F(1,6) = .373, p = .564).

FIGURE 5.

Side bias index, test session duration, and response selection latency. (a) Side bias index values computed for each test block (blocks 1–3; b1, b2, b3) following vehicle (veh) or muscimol (mus) infusions. Side bias index is calculated as the absolute value of (total number of left well responses—total number of right well responses) / total number trials, such that a value of 0 reflects no side bias and an equal number of responses made to left and right wells, and a value of 1 reflects a complete bias to either the left or right side well. Muscimol infusions led rats to have a greater side bias across all test blocks (main effect infusion; p = .003). (b) Session durations (minutes; min) by infusion condition across test blocks. Prefrontal muscimol infusions did not slow behavioral responding on the mnemonic discrimination task, but rather led rats to complete test sessions in a shorter period of time relative to vehicle infusions (main effect infusion; p = .035). (c) Response selection latencies (milliseconds; ms) for correct trials by infusion condition across test blocks. Prefrontal muscimol infusions did not alter response latencies relative to vehicle infusions on any test block (p’s >.085). *p <.05

3.5 |. PFC muscimol does not slow behavior or response selection

An important consideration in interpreting the effects of temporary neuronal inactivation is the potential for muscimol to disrupt motor function or motivation, impeding task performance. Analyses confirmed that all rats completed full test sessions of 50 trials after receiving PFC infusions of muscimol. The duration of test sessions following vehicle versus muscimol infusions is shown in Figure 5b. A repeated measures ANOVA with test block and infusion condition as within subjects factors revealed a significant main effect of infusion (F(1,4) = 9.898, p = .035), but no main effect of block or block × infusion interaction (F’s <.624, p’s >.560). Within subjects contrasts showed the duration of test sessions differed between infusion conditions only on block 1 (p = .017, Blocks 2–3, p’s >.173). Critically, rats completed their test sessions faster following prefrontal muscimol infusions on this first test block, relative to vehicle infusions.

To determine if this speeding of test completion was attributable to faster response selection, response latencies were scored on video recordings of each test session. As in prior studies (Burke, Turner, et al., 2018; Johnson et al., 2017, 2018), response latencies are defined as the time elapsed between the point at which the rat’s nose crossed the threshold of the choice platform and the point at which the rat initiated displacement of one of the objects on the choice platform. Response latencies for correct responses to rats’ inherent biased side are shown in Figure 5c. Latencies for incorrect responses and responses to rats’ inherent nonbiased side are excluded because of missing data on tests following muscimol infusions; in most cases, rats made no responses to their nonbiased side after prefrontal muscimol infusions. Because some video recordings were lost due to technical issues, response latency data from each block and drug condition were treated as independent samples and analyzed with nonparametric tests. The effect of infusion condition on correct response latencies for each test block was assessed with Mann–Whitney U tests (asymptotic significance, 2-tailed). Latencies did not differ based on infusion condition in block 1 (mean latency vehicle = 1,218 ms versus muscimol = 1,058 ms; U = 11, n1/2 = 7, p = .085), block 2 (mean latency vehicle = 1,475 ms versus muscimol = 1,332 ms; U = 13, n1/2 = 6, p = .423), or block 3 (mean latency vehicle =1,276 ms versus muscimol = 1,033 ms; U = 4.0, n1 = 4, n2 = 5, p = .142). The effect of test block on correct response latencies was also assessed with Kruskal–Wallis tests. Latencies did not differ by block after vehicle infusions (H[2] = 0.520, p = .771) or after muscimol infusions (H[2] = 0.500, p = .779).

4 |. DISCUSSION

In the current study, we document a novel role for PFC activity in the mnemonic discrimination of similar object stimuli. Our main finding is that PFC inactivation impairs rats’ abilities to distinguish a previously learned target object (S+) from lure objects (S−) that share 50–90% overlapping visible features both when the lure objects are novel and when they are familiar (Figure 4b). This behavioral impairment is distinct from what is observed following reversible disruption of activity in the dentate gyrus (DG)/CA3 hippocampal subregions, in which DG/CA3 muscimol infusions only impair rats’ performances when lure stimuli are novel. Together these data indicate that both the hippocampus and the PFC are critical for mnemonic discrimination performance, but the time course of involvement and modulation by lure novelty is dissociable between these structures.

The mnemonic discrimination of similar stimuli has been attributed to the hippocampus due to its hypothesized role in orthogonalizing inputs from parahippocampal cortical regions to minimize interference (i.e., to pattern separate, Marr, 1971; McNaughton & Morris, 1987; Treves & Rolls, 1992; O’Reilly & McClelland, 1994; Yassa & Stark, 2011; Santoro, 2013; Kesner & Rolls, 2015; Knierim & Neunuebel, 2016; Leal & Yassa, 2018). This hypothesis has been supported by behavioral data showing that hippocampal lesions impair discrimination of similar spatial locations (Gilbert, Kesner, & DeCoteau, 1998; Gilbert, Kesner, & Lee, 2001; Morris, Churchwell, Kesner, & Gilbert, 2012; Oomen et al., 2015). Additional support has come from human functional neuroimaging data showing that activation of hippocampal DG/CA3 is associated with mnemonic discrimination performance across adulthood (Bakker et al., 2008; Doxey & Kirwan, 2015; Kirwan & Stark, 2007; Lacy et al., 2011; Motley & Kirwan, 2012; Reagh et al., 2018; Reagh & Yassa, 2014; Yassa & Stark, 2011). While the DG/CA3 is clearly involved in mnemonic discrimination, particularly when the lures are novel, recent behavioral and neurophysiological data do not support that this is through the orthogonalization of similar input patterns. Specifically, in optogenetically verified neuron populations, DG granule cells do not have updated activity patterns when the testing arena in a common room is changed (Senzai & Buzsáki, 2017). These data suggest that DG granule cells may not support the disambiguation of overlapping sensory input. Thus, other brain structures, such as the PFC, must support mnemonic discrimination when familiar stimuli need to be disambiguated from each other. The precise mechanisms by which the PFC supports mnemonic discrimination task performance remain to be determined, but could involve three not mutually exclusive possibilities that are related to functional connectivity with the hippocampus, PFC recruitment during increasing cognitive load, or optimal strategy implementation.

4.1 |. PFC contributions to hippocampal-dependent behavior through functional connectivity

There are several potential interpretations regarding the dissociable effects of dorsal hippocampal versus PFC muscimol infusions on mnemonic similarity task performance. A first possibility is that, as task stimuli and procedures become increasingly familiar, cortical regions can compensate for hippocampal dysfunction. Neural activity across PFC regions could therefore account for rats’ abilities to overcome DG and CA3 dysfunction in the mnemonic discrimination task once they have gained experience with lure stimuli (Johnson et al., 2018). There are several bases for this idea. Well-known models of systems-level memory consolidation argue hippocampal activity is most required for learning and formation of new memory representations, and that these representations become distributed across PFC regions over time (Eichenbaum, 2017; Frankland & Bontempi, 2005; Takehara-Nishiuchi, 2020). On the other hand, it is increasingly acknowledged that specific functions or phases of memory processing cannot necessarily be ascribed to dissociable brain circuits, and that compensation for damage to a given region is possible due to dynamic and distributed processing (Ash & Rapp, 2014; Burke, Gaynor, et al., 2018; Fanselow, 2010; Rubin, Schwarb, Lucas, Dulas, & Cohen, 2017). Our current results suggest the PFC is a critical node in a distributed cortical-hippocampal circuit engaged by mnemonic discrimination.

Another study using contextual fear conditioning in rats points to the PFC as a site of compensation for hippocampal dysfunction (Zelikowsky et al., 2013). In these experiments, dorsal hippocampal lesions led to retrograde—but not anterograde—impairments in expression and renewal of contextually conditioned fear memory (Zelikowsky et al., 2013). However, dual lesions of dorsal hippocampus and the infralimbic or prelimbic cortex, or lesions of only the infralimbic cortex, impaired new contextual fear learning, discrimination, and renewal (Zelikowsky et al., 2013). Further, rats with lesions to only the dorsal hippocampus showed increased neural activation in the prelimbic cortex associated with unimpaired contextual fear memory retrieval (Zelikowsky et al., 2013). What is most intriguing about these findings with respect to dynamic processing is that the medial PFC regions compensating for hippocampal dysfunction do not share direct projections with the dorsal hippocampal sub-regions that were lesioned. The prelimbic and infralimbic cortices receive monosynaptic projections from ventral hippocampus, but mainly interface with the hippocampus through multi-synaptic reciprocal connections via entorhinal and perirhinal cortices, as well as the thalamic nucleus reuniens (Agster & Burwell, 2009; Burwell & Amaral, 1998; Cenquizca & Swanson, 2007; Hoover & Vertes, 2007; Hwang et al., 2018; Swanson, 1981; Swanson & Köhler, 1986; Vertes, 2004). This emphasizes the distributed nature of circuit activity and functional connectivity that occurs during multiple forms of memory processing traditionally linked to hippocampal function.

The current data indicate that a larger distributed network is critical for mnemonic similarity task performance, which is consistent with human imaging data. In young adults, mnemonic discrimination abilities correlate with activation of lateral entorhinal and perirhinal cortices to the same extent as activation of hippocampal CA3/DG (Reagh & Yassa, 2014). In contrast, in older adults, mnemonic discrimination impairments are associated with decreased activity in lateral entorhinal and perirhinal cortices, increased activity in CA3/DG (Bakker et al., 2012, 2015; Berron et al., 2018, 2019; Reagh et al., 2018; Ryan et al., 2012), and loss of perforant path white matter integrity (Bennett et al., 2015; Bennett & Stark, 2016; Yassa et al., 2010). These human data suggest entorhinal and perirhinal regions provide a hub through which neural activity coordinates mnemonic discrimination functions; however, few studies have examined activation in nontemporal cortical regions during these tasks. In animal models, several studies have directly tested this possibility using other hippocampal-dependent tasks. Disconnection of the perirhinal cortex from medial prefrontal cortex by infusing muscimol in contralateral hemispheres impaired recall of previously learned object-place paired associations (Hernandez et al., 2017) that depend on the hippocampus (Jo & Lee, 2010a; Lee & Solivan, 2008). In fact, blockade of prefrontal-perirhinal communication impaired object-place memory to the same extent as inactivation of medial prefrontal cortex or perirhinal cortex on their own (Hernandez et al., 2017). Similarly, reversible inactivation of neurons in the perirhinal cortex or thalamic nucleus reuniens that receive medial prefrontal cortex input, with AAV-mediated expression of the inhibitory DREADD hM4Di, impaired memory for previously learned odor sequences (Jayachandran et al., 2019). In this case, deficits produced by selectively targeting neurons that received prefrontal input were more profound that those resulting from direct inactivation of the medial prefrontal cortex itself (Jayachandran et al., 2019). The current study is the first, to our knowledge, to directly test involvement of PFC activity in the mnemonic discrimination of similar object stimuli, and thus we have not yet explored how prefrontal communication with parahippocampal cortices influences rats’ performance on the task. The recent observation that unilateral transection of perforant path input from the lateral entorhinal cortex to the dorsal DG and CA3 selectively impairs young adult rats’ abilities to distinguish a known target object from similar lures (Burke, Turner, et al., 2018), suggests that lateral entorhinal cortical activity is also necessary for rats’ performance on the task. Additionally, it is well established that lesion or inactivation of the perirhinal cortex impairs object recognition and discrimination in rats and monkeys (Bartko, Winters, Cowell, Saksida, & Bussey, 2007a, 2007b; Bussey, Saksida, & Murray, 2002, 2003; Murray & Richmond, 2001; Winters, Bartko, Saksida, & Bussey, 2010; Winters & Bussey, 2005) and perirhinal neural activity can reflect perceptual differences in object stimuli that share feature overlap, as well as their mnemonic significance (Ahn & Lee, 2017). Thus, it logically follows that communication across parahippocampal and prefrontal cortices supports mnemonic discrimination of similar stimuli. This area remains open for future investigation.

4.2 |. PFC contributions to increasing cognitive load as stimuli become more similar

A second potential interpretation of the current finding that PFC activity is needed for mnemonic discrimination, irrespective of experience with similar lure objects, is that frontal regions are recruited during tasks that impose a high cognitive load. Mnemonic discrimination requires working memory (Hales, Broadbent, Velu, Squire, & Clark, 2015), retention of stimulus representations across delays, resolution of interference across similar stimuli, and flexibility in selecting an appropriate response strategy. Thus, it is likely frontal cortical function plays a significant role in mnemonic discrimination, yet few studies have examined PFC activity as it relates to discrimination abilities.

Until recently, only one human neuroimaging study had specifically addressed whether PFC and other neocortical regions show activation consistent with the ability to discriminate between familiar and lure stimuli that shared features (Pidgeon & Morcom, 2016). During initial presentation of image stimuli, activation in response to parametrically varied features of image stimuli was varied in the occipitotemporal, lateral prefrontal, and right parietal cortical regions (Pidgeon & Morcom, 2016). Additionally, activation of occipital and lateral PFC regions during initial encoding was associated with accurate mnemonic discrimination in the test phase 24 hr later, suggesting these cortical regions assist in generating distinct representations of similar stimuli to serve later memory (Pidgeon & Morcom, 2016). A subsequent human study tested the effect of unilaterally disrupting neural activity in ventromedial prefrontal cortex with repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) on mnemonic discrimination performance (Wais et al., 2018). These experiments showed rTMS delivered to the prefrontal cortex, but not angular gyrus, impaired discrimination performance in young adult participants (Wais et al., 2018). In contrast, two recent functional neuroimaging studies examining hippocampal and neocortical recruitment during mnemonic similarity task performance found, as previously, activation patterns in hippocampal CA3/DG and perirhinal cortex were associated with accurate mnemonic discrimination (Klippenstein, Stark, Stark, & Bennett, 2020; Stevenson, Reagh, Chun, Murray, & Yassa, 2020). However, while a similar pattern was observed in occipital cortex, this activity did not predict mnemonic discrimination performance to the same extent as CA3/DG (Klippenstein et al., 2020). Disparities among these human imaging findings may relate to the timing of stimulus presentations or to differences in fMRI analyses.

PFC involvement in mnemonic discrimination abilities has also not been widely investigated in aging. In one study, the same analyses that revealed decreased perforant path fiber integrity correlates with age-related mnemonic discrimination impairments also found loss of hippocampal cingulum white matter integrity to have the same consequence (Bennett & Stark, 2016). Given the hippocampal cingulum provides widespread connections from medial temporal lobe to frontal regions (Bubb, Metzler-Baddeley, & Aggleton, 2018), this could suggest individuals with deterioration of these white matter tracts are more prone to impairments because of lack of connectivity to support neural compensation. A more recent study found a similar loss of integrity of the parahippocampal cingulum in older adults with mild cognitive impairment, which correlated with decreased entorhinal cortical thickness and functional connectivity between hippocampal and posterior frontal cortical regions (Berron, van Westen, Ossenkoppele, Strandberg, & Hansson, 2020). While mnemonic discrimination abilities were not assessed in this study population, reduced hippocampal-cortical connectivity also associated with elevated cerebrospinal fluid levels of phosphorylated tau and amyloid-β (Berron et al., 2020). Given mnemonic discrimination impairments are observed in older adults with early signs of dementia or Alzheimer’s pathology (Bakker et al., 2012, 2015; Berron et al., 2019; Reagh et al., 2014; Stark et al., 2013), it is likely frontal-cortical disconnection in aging and its exacerbation by neurodegenerative pathology contribute to reduced abilities to perform well on high-demand tasks such as the distinction of similar stimuli from memory.

The role of PFC regions in supporting performance on tasks with high cognitive demand has been more directly investigated in animal models. While effects of disrupting PFC activity on mnemonic discrimination of objects had not previously been tested, infusion of the NMDA antagonist AP5 in the medial prefrontal cortex impaired mnemonic discrimination of both distinct and similar spatial locations in a touchscreen-based trial-unique delayed nonmatch-to-location (TUNL) task in rats (Davies, Hurtubise, Greba, & Howland, 2017). In contrast, ibotenic acid lesions of the medial prefrontal cortex did not impair spatial discriminations on the same touchscreen TUNL task in a second study in rats (McAllister, Saksida, & Bussey, 2013). However, prefrontal lesions did impair performance when a postsample delay or high interference conditions were introduced (McAllister et al., 2013), consistent with a role for prefrontal cortex in supporting performance when greater task demands are present. Additional data from hippocampal-dependent tasks in rats support the same conclusion. Lesions or reversible inactivation of the prelimbic cortex impair spatial working memory across long, but not brief, delays (Churchwell & Kesner, 2011; Dunnett, 1990; Floresco, Seamans, & Phillips, 1997; Seamans, Floresco, & Phillips, 1995), and muscimol infusions in the medial prefrontal cortex impair odor memory or match-to-sample performance under conditions with high interference across stimuli (Peters, David, Marcus, & Smith, 2013; Peters & Smith, 2020). Collectively, results of these experiments support an interpretation that PFC activity is necessary to support performance on hippocampal-dependent tasks that pose a high cognitive demand, whether by requiring distinction of similar stimuli, imposing a working memory load, or increasing interference across trials.

4.3 |. The prefrontal cortex may be critical for optimal strategy selection during the mnemonic similarity task performance

The PFC may also be critical for rats’ abilities to implement an optimal strategy for rodent mnemonic discrimination performance. Rats show a side bias early in training for object discrimination tasks that require a forced choice, in which an object on a particular side is selected regardless of the object’s features (e.g., Hernandez et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2017; Kim, Delcasso, & Lee, 2011; Lee & Byeon, 2014; Lee & Kim, 2010; Lee & Park, 2013). The side bias manifests from a response-driven strategy that is implemented before the animals acquire the task rule. Critically, the ability to inhibit the response-driven side bias behavior and use the correct stimulus-driven strategy is related to PFC activity (Lee & Byeon, 2014). Moreover, activity patterns in the hippocampus are altered after a rat shifts from using a side biased strategy to the correct strategy (Kim et al., 2011; Lee & Byeon, 2014; Lee & Kim, 2010). Thus, it is not surprising that an enhanced side bias occurs in the rodent mnemonic discrimination task following muscimol infusion into either the PFC or DG/CA3, as disrupting activity in either region will interfere with an animal’s ability to employ the correct stimulus-dependent strategy to select the target over a similar lure. Specifically, when the structures that support optimal strategy selection are disrupted, namely the PFC and hippocampus, the animal may regress to a response-driven strategy that leads to a side bias. We hypothesis that the side bias is promoted by the dorsal striatum, which supports response-driven behavior (Graybiel, 1998; Packard & McGaugh, 1992; Pych, Chang, Colon-Rivera, & Gold, 2005). When the medial PFC or hippocampus are disrupted, the dorsal striatum may become disinhibited or serve to compensate for disrupted network activity thereby promoting a response-driven strategy that increases the side bias. This notion is supported by a previous study reporting that an increased side bias is associated with greater activity in the dorsal striatum, as well as elevated functional connectivity between the dorsal striatum and anterior cingulate cortex (Colon-Perez et al., 2019). Moreover, aged rats that have impaired mnemonic similarity task performance show a greater side bias (Johnson et al., 2017). It is well documented that old animals are more likely to employ striatal-dependent response-driven strategies (Barnes, Nadel, & Honig, 1980; Pereira, Gallagher, & Rapp, 2015), and that the dorsal striatum does not show age-related deterioration to the same extent as the hippocampus (Gardner, Gold, et al., 2020; Gardner, Newman, et al., 2020).

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study demonstrate that disrupting neural activity in the prefrontal cortex impairs mnemonic discrimination of a known target object from similar lures in young adult rats, across repeated tests and irrespective of prior experience with task stimuli. This finding is in contrast to prior documented effects of disrupting neural activity in the hippocampal dentate gyrus and CA3, which impaired mnemonic discrimination on a first test when lure stimuli were novel, but not on subsequent tests as lure stimuli became increasingly familiar (Johnson et al., 2018). These findings highlight contributions of PFC activity and, potentially, prefrontal-parahippocampal cortical connectivity to supporting memory processes considered to be primarily hippocampal-dependent. Furthermore, given sensitivity of mnemonic discrimination tasks to age-related decline, our results emphasize the importance of considering how hippocampal dysfunction linked to discrimination impairments influences prefrontal and parahippocampal cortical circuit activity, potential for compensation across prefrontal and parahippocampal cortical networks, and broader cognitive outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Edward “Sam” Eusanio and Meena Ravi for help with behavioral video scoring. The authors also thank Abbi Hernandez and Katelyn Lubke for assistance with collecting and processing tissue for histology. This work was carried out with funds from the Evelyn F. McKnight Brain Research Foundation (Sarah A. Johnson, Sara N. Burke), the National Institute on Aging K99 AG058786 (Sarah A. Johnson), R01 AG049722 (Sara N. Burke), and a McKnight Brain Institute Fellowship (Sarah A. Johnson).

Funding information

Evelyn F. McKnight Brain Research Foundation; National Institute on Aging, Grant/Award Numbers: K99 AG058786 (SAJ), R01 AG049722 (SNB)

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data Availability Statement The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Agster KL, & Burwell RD (2009). Cortical efferents of the perirhinal, postrhinal, and entorhinal cortices of the rat. Hippocampus, 19, 1159–1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn J-R, & Lee I (2017). Neural correlates of both perception and memory for objects in the rodent perirhinal cortex. Cerebral Cortex, 27(7), 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ash JA, & Rapp PR (2014). A quantitative neural network approach to understanding aging phenotypes. Ageing Research Reviews, 15, 44–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A, Albert MS, Krauss G, Speck CL, & Gallagher M (2015). Response of the medial temporal lobe network in amnestic mild cognitive impairment to therapeutic intervention assessed by fMRI and memory task performance. NeuroImage: Clinical, 7, 688–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A, Kirwan CB, Miller M, & Stark CE (2008). Pattern separation in the human hippocampal CA3 and dentate gyrus. Science, 319, 1640–1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A, Krauss GL, Albert MS, Speck CL, Jones LR, Stark CE, … Gallagher M (2012). Reduction of hippocampal hyperactivity improves cognition in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuron, 74, 467–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bañuelos C, Beas BS, McQuail JA, Gilbert RJ, Frazier CJ, Setlow B, & Bizon JL (2014). Prefrontal cortical GABAergic dysfunction contributes to age-related working memory impairment. Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 34, 3457–3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes CA, & McNaughton BL (1980). Physiological compensation for loss of afferent synapses in rat hippocampal granule cells during senescence. The Journal of Physiology, 309, 473–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes CA, Nadel L, & Honig WK (1980). Spatial memory deficit in senescent rats. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 34, 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry DN, & Maguire EA (2019). Remote memory and the hippocampus: A constructive critique. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23, 128–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartko SJ, Winters BD, Cowell RA, Saksida LM, & Bussey TJ (2007a). Perirhinal cortex resolves feature ambiguity in configural object recognition and perceptual oddity tasks. Learning & Memory (Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.), 14, 821–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartko SJ, Winters BD, Cowell RA, Saksida LM, & Bussey TJ (2007b). Perceptual functions of perirhinal cortex in rats: Zero-delay object recognition and simultaneous oddity discriminations. Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 27, 2548–2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett IJ, Huffman DJ, & Stark CEL (2015). Limbic tract integrity contributes to pattern separation performance across the lifespan. Cerebral Cortex, 25, 2988–2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett IJ, & Stark CEL (2016). Mnemonic discrimination relates to perforant path integrity: An ultra-high resolution diffusion tensor imaging study. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 129, 107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berron D, Cardenas-Blanco A, Bittner D, Metzger CD, Spottke A, Heneka MT, … Düzel E (2019). Higher CSF tau levels are related to hippocampal hyperactivity and object mnemonic discrimination in older adults. Journal of Neuroscience, 39(44), 8788–8797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berron D, Neumann K, Maass A, Schütze H, Fliessbach K, Kiven V, … Düzel E (2018). Age-related functional changes in domain-specific medial temporal lobe pathways. Neurobiology of Aging, 65, 86–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berron D, van Westen D, Ossenkoppele R, Strandberg O, & Hansson O (2020). Medial temporal lobe connectivity and its associations with cognition in early Alzheimer’s disease. Brain: A Journal of Neurology, 143, 1233–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubb EJ, Metzler-Baddeley C, & Aggleton JP (2018). The cingulum bundle: Anatomy, function, and dysfunction. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 92, 104–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SN, Gaynor LS, Barnes CA, Bauer RM, Bizon JL, Roberson ED, & Ryan L (2018). Shared functions of perirhinal and parahippocampal cortices: Implications for cognitive aging. Trends in Neurosciences, 41, 349–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SN, Turner SM, Desrosiers CL, Johnson SA, & Maurer AP (2018). Perforant path fiber loss results in mnemonic discrimination task deficits in young rats. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 12, 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SN, Wallace JL, Hartzell AL, Nematollahi S, Plange K, & Barnes CA (2011). Age-associated deficits in pattern separation functions of the perirhinal cortex: A cross-species consensus. Behavioral Neuroscience, 125, 836–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SN, Wallace JL, Nematollahi S, Uprety AR, & Barnes CA (2010). Pattern separation deficits may contribute to age-associated recognition impairments. Behavioral Neuroscience, 124, 559–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burwell RD, & Amaral DG (1998). Cortical afferents of the perirhinal, postrhinal, and entorhinal cortices of the rat. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 398, 179–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussey TJ, Saksida LM, & Murray EA (2002). Perirhinal cortex resolves feature ambiguity in complex visual discriminations. The European Journal of Neuroscience, 15, 365–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussey TJ, Saksida LM, & Murray EA (2003). Impairments in visual discrimination after perirhinal cortex lesions: Testing “declarative” vs. “perceptual-mnemonic” views of perirhinal cortex function. The European Journal of Neuroscience, 17, 649–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camfield DA, Fontana R, Wesnes KA, Mills J, & Croft RJ (2018). Effects of aging and depression on mnemonic discrimination ability. Neuropsychology, Development, and Cognition. Section B, Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition, 25, 464–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenquizca LA, & Swanson LW (2007). Spatial organization of direct hippocampal field CA1 axonal projections to the rest of the cerebral cortex. Brain Research Reviews, 56, 1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchwell JC, & Kesner RP (2011). Hippocampal-prefrontal dynamics in spatial working memory: Interactions and independent parallel processing. Behavioural Brain Research, 225, 389–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colon-Perez LM, Turner SM, Lubke KN, Pompilus M, Febo M, & Burke SN (2019). Multiscale imaging reveals aberrant functional connectome organization and elevated dorsal striatal. eNeuro, 6. 10.1523/ENEURO.0047-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condé F, Maire-Lepoivre E, Audinat E, & Crépel F (1995). Afferent connections of the medial frontal cortex of the rat. II. Cortical and sub-cortical afferents. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 352, 567–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies DA, Hurtubise JL, Greba Q, & Howland JG (2017). Medial prefrontal cortex and dorsomedial striatum are necessary for the trial-unique, delayed nonmatching-to-location (TUNL) task in rats: Role of NMDA receptors. Learning & memory (Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.), 24, 262–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doxey CR, & Kirwan CB (2015). Structural and functional correlates of behavioral pattern separation in the hippocampus and medial temporal lobe: Age and pattern separation. Hippocampus, 25, 524–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunnett SB (1990). Role of prefrontal cortex and striatal output systems in short-term memory deficits associated with ageing, basal forebrain lesions, and cholinergic-rich grafts. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 44, 210–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H (2017). Prefrontal-hippocampal interactions in episodic memory. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 18, 547–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanselow MS (2010). From contextual fear to a dynamic view of memory systems. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14, 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floresco SB, Seamans JK, & Phillips AG (1997). Selective roles for hippocampal, prefrontal cortical, and ventral striatal circuits in radial-arm maze tasks with or without a delay. Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 17, 1880–1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankland PW, & Bontempi B (2005). The organization of recent and remote memories. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 6, 119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffan D (2002). Against memory systems. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 357, 1111–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RS, Gold PE, & Korol DL (2020). Inactivation of the striatum in aged rats rescues their ability to learn a hippocampus-sensitive spatial navigation task. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 172, 107231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RS, Newman LA, Mohler EG, Tunur T, Gold PE, & Korol DL (2020). Aging is not equal across memory systems. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 172, 107232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geinisman Y, de Toledo-Morrell L, Morrell F, Persina IS, & Rossi M (1992). Age-related loss of axospinous synapses formed by two afferent systems in the rat dentate gyrus as revealed by the unbiased stereological dissector technique. Hippocampus, 2, 437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PE, Kesner RP, & DeCoteau WE (1998). Memory for spatial location: Role of the hippocampus in mediating spatial pattern separation. The Journal of Neuroscience, 18, 804–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PE, Kesner RP, & Lee I (2001). Dissociating hippocampal sub-regions: A double dissociation between dentate gyrus and CA1. Hippocampus, 11, 626–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybiel AM (1998). The basal ganglia and chunking of action repertoires. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 70, 119–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales JB, Broadbent NJ, Velu PD, Squire LR, & Clark RE (2015). Hippocampus, perirhinal cortex, and complex visual discriminations in rats and humans. Learning & memory (Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.), 22, 83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez AR, Maurer AP, Reasor JE, Turner SM, Barthle SE, Johnson SA, & Burke SN (2015). Age-related impairments in object-place associations are not due to hippocampal dysfunction. Behavioral Neuroscience, 129, 599–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez AR, Reasor JE, Truckenbrod LM, Campos KT, Federico QP, Fertal KE, … Burke SN (2018). Dissociable effects of advanced age on prefrontal cortical and medial temporal lobe ensemble activity. Neurobiology of Aging, 70, 217–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez AR, Reasor JE, Truckenbrod LM, Lubke KN, Johnson SA, Bizon JL, … Burke SN (2017). Medial prefrontal-perirhinal cortical communication is necessary for flexible response selection. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 137, 36–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden HM, Toner C, Pirogovsky E, Kirwan CB, & Gilbert PE (2013). Visual object pattern separation varies in older adults. Learning & Memory, 20, 358–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover WB, & Vertes RP (2007). Anatomical analysis of afferent projections to the medial prefrontal cortex in the rat. Brain Structure & Function, 212, 149–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman DJ, & Stark CEL (2017). Age-related impairment on a forced-choice version of the mnemonic similarity task. Behavioral Neuroscience, 131, 55–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang E, Willis BS, & Burwell RD (2018). Prefrontal connections of the perirhinal and postrhinal cortices in the rat. Behavioural Brain Research, 354, 8–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman BT, Van Hoesen GW, Damasio AR, & Barnes CL (1984). Alzheimer’s disease: Cell-specific pathology isolates the hippocampal formation. Science, 225, 1168–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay TM, & Witter MP (1991). Distribution of hippocampal CA1 and subicular efferents in the prefrontal cortex of the rat studied by means of anterograde transport of Phaseolus vulgaris-leucoagglutinin. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 313, 574–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayachandran M, Linley SB, Schlecht M, Mahler SV, Vertes RP, & Allen TA (2019). Prefrontal pathways provide top-down control of memory for sequences of events. Cell Reports, 28, 640–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo YS, & Lee I (2010a). Disconnection of the hippocampal-perirhinal cortical circuits severely disrupts object-place paired associative memory. Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 30, 9850–9858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo YS, & Lee I (2010b). Perirhinal cortex is necessary for acquiring, but not for retrieving object-place paired association. Learning & memory (Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.), 17, 97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SA, Turner SM, Lubke KN, Cooper TL, Fertal KE, Bizon JL, … Burke SN (2018). Experience-dependent effects of Muscimol-induced hippocampal excitation on mnemonic discrimination. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 12, 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SA, Turner SM, Santacroce LA, Carty KN, Shafiq L, Bizon JL, … Burke SN (2017). Rodent age-related impairments in discriminating perceptually similar objects parallel those observed in humans. Hippocampus, 27, 759–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP, & Rolls ET (2015). A computational theory of hippocampal function, and tests of the theory: New developments. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 48, 92–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Delcasso S, & Lee I (2011). Neural correlates of object-in-place learning in hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience, 31, 16991–17006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan CB, & Stark CEL (2007). Overcoming interference: An fMRI investigation of pattern separation in the medial temporal lobe. Learning & Memory, 14, 625–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klippenstein JL, Stark SM, Stark CEL, & Bennett IJ (2020). Neural substrates of mnemonic discrimination: A whole-brain fMRI investigation. Brain and Behavior, 10(3), e01560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knierim JJ, & Neunuebel JP (2016). Tracking the flow of hippocampal computation: Pattern separation, pattern completion, and attractor dynamics. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 129, 38–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreher MA, Johnson SA, Mizell J-M, Chetram DK, Guenther DT, Lovett SD, … Maurer AP (2019). The perirhinal cortex supports spatial intertemporal choice stability. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 162, 36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy JW, Yassa MA, Stark SM, Muftuler LT, & Stark CEL (2011). Distinct pattern separation related transfer functions in human CA3/dentate and CA1 revealed using high-resolution fMRI and variable mnemonic similarity. Learning & Memory, 18, 15–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal SL, & Yassa MA (2018). Integrating new findings and examining clinical applications of pattern separation. Nature Neuroscience, 21, 163–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]